Zürich, 30 December 2015:

We have all seen them.

Scribblings, scratchings, stencils, murals up, down, over and under in public places.

Simple messages to elaborate street-long paintings.

This is nothing new under the sun.

Ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans knew them.

Today, spray paint and markers and what has been wrought from them are part and parcel of the modern urban scene around the world.

Graffiti marks territory, expresses social outrage, pokes fun at politics, advertises services, declares love and hate for others, curses and criticism, quotations and questioning, can be expressive, excessive and offensive.

See it on construction sites and dying edifices, in latrines, on the side of boxcars, in/on subways and under bridges.

“Kilroy was here.”

“Bird lives.”

“Boredom is counterrevolutionary.”

“Free Huey.”

“Dick Nixon before Nixon dicks you.”

“Clapton is God.”

“Frodo lives.”

On a wall of a fortress in Verdun, France:

“Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1918

Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.”

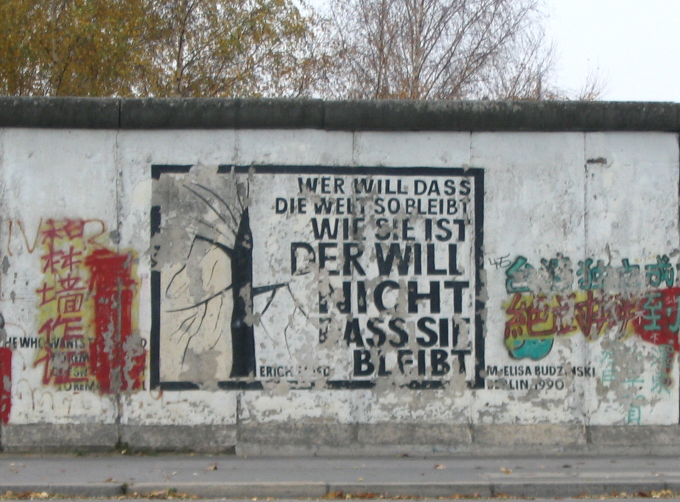

“Anyone who wants to keep the world as it is, does not want it to remain” (Berlin Wall)

Is graffiti simply an act of criminal defacement, a perverse vandal activity?

Is graffiti art, worthy of admiration and respect?

Zürich: a cold-hearted centre of cold cash where conservative bankers toil in silence and the trams are never late?

Yet we forget that here amongst the gnomes of gold and the dullness of lucre that Zürich has also been the site of restlessness and rebellion, revolution and riots, insurrection and imagination.

In the streets, in the night, Zürich has never lacked students, artists, musicians, journalists…its drinkers and its drug users…its free spirits and those longing to be free.

In 1977 an enigma began – a graffiti artist began leaving his mark on city walls and buildings.

Under cover of night he used black spray paint to create human figures on both public and private buildings.

They were distinct, spindly figures, looking as if they were made of wire.

The Swiss authorities and the majority of the general public saw these figures as illegal defacement of property.

Intellectuals and artists saw value and creativity in the works of “the Sprayer of Zürich”.

The authorities issued a warrant for his arrest.

He was eventually apprehended after returning to the scene of one of his works having forgotten his glasses.

Meet Harald Naegeli, born 1939, a classically trained artist who had studied in the Kunstgewerbeschule of Zürich and at the Ècole des Beaux Arts in Paris.

At the time of his arrest in June 1979, he had already painted graffiti on 900 buildings in Zürich.

Prior to being tried Nageli fled to Germany.

He was sentenced in absentia to 9 months in prison and a 206, 000 Swiss francs fine.

Despite an appeal from lawyers, Naegeli´s sentence was confirmed by the Swiss Supreme Court in November 1981.

An international warrant for his arrest was issued.

72 Swiss artists signed a petition to have Naegeli pardoned but to no avail.

In Germany, his work was more appreciated as art, and Naegeli remained there for the next few years.

Naegeli continued to spray his characteristic wire-frame graffiti in Köln and Düsseldorf.

They were not unanimously welcomed there either, but they caused much less discussion than they had in Zürich.

In Köln, he produced in 1980-81 a cycle of about 600 graffiti that became known as the Kölner Totentanz (Cologne´s Dance of Death).

Most of these works were removed already the day after their creation by the city cleaning department.

The mayor of Osnabrück even invited Naegeli to spray in his city, but Naegeli declined the offer.

Adolf Muschg, an eminent Swiss writer and ETH Zürich professor of literature and one of the 72 artists who had signed the petition, commented later:

“He doesn’t work on commission.

He does not sell out his rage”.

On 27 August 1983, Naegeli was arrested at Puttgarden on the Baltic island of Fehmarn when he tried to cross over to Denmark, but was released again on bail.

Germany was reluctant to grant the Swiss the extradition, but finally agreed to evict Naegeli.

On 29 April 1984, Naegeli turned himself in to the Swiss police at the border crossing in Lörrach and subsequently served his jail sentence.

Once released, he returned to Düsseldorf in Germany.

Naegeli largely disappeared from the attention of the public in the late 1980s.

He began focusing on drawings on paper and etchings.

He calls his new works Partikelzeichnungen – they are composed of thousands of minuscule dots and small lines.

This slow process is in stark contrast to his earlier graffiti that, by their very nature, were a very spontaneous means of expression.

Naegeli became a well-respected artist in Germany.

In 1997, he produced a graffito for the University of Tübingen.

In 1998, he was called as a professor at the Thomas-Morus-Academy in Cologne.

He has donated his Partikelzeichnungen to the Institute of Art History at the University of Tübingen.

Not wishing to miss out on Naegeli´s unexpected celebrity celebrity the authorities in Zürich decided to recognise the worth of Naegeli´s early work, which they dubbed Schmiererei (Scribblings), by protecting a still extant graffito to the rear of a University of Zürich building at Schönberggasse 9.

So, why was Zürich so intent on criminalising Naegeli in the 80s?

For what he represented…

These scribblings in the night were etchings of protest, abstractions in a city of orderliness.

Nights of punk pleasures, artistic anarchy and squatters seeking shelter in a city where affordable accommodation was a luxury many couldn´t (and still can´t) afford.

On 30 May 1980 a protest is staged by youth activists outside Zürich´s Opera House.

This leads to months of rioting between police and protestors, shops wrecked, cars burned, 1000s arrested, many injured…

One woman dies after setting herself on fire in protest.

It takes effort to reach this last remnant of Naegeli´s Scribblings.

The street is a small one.

There are no signs for the average tourist to know of this last work.

This faculty building, dedicated to the study of the German language, does not advertise this back corner drawing.

I end up climbing fences and gripping hills to finally view it.

Like Needle Park, what is seen by the eyes reveals little of the spirit beneath.

(See Haa Bay and Needle Park of this blog.)

For those who wonder if the spirit of revolution and change remains need only walk the streets.

The writing´s on the walls.

(Sources: Only in Zürich, Duncan Smith; Wikipedia)

Before you hand me over

Before you read my sentence

I’d like to say a few words

Here in my own defence

Some people struggle daily

They struggle with their conscience

I have no guilt to haunt me

I feel no wrong intent.

Gowan, “A Criminal Mind”