Landschlacht, 22 January 2016

Being married to a German doctor has its advantages and its disadvantages.

Because Europeans and their higher educational standards are very demanding and extensive, one can visit a physician in Germany and Switzerland in complete confidence that they probably know what they are talking about should you ever have occasion to need one of them.

The downside of this attitude is that those of a Germanic persuasion tend to have two characteristics one must always bear in mind:

In their hopeless quest to control the very Fates themselves, they will be quite explicit in their instructions and will lecture you into submission about the wisdom of doing so.

When one is “under the weather”, it is easier to capitulate than waste energy in a debate they will not let you win.

And German-speakers, knowing that this quest to control destiny is ultimately doomed, will forecast and convince themselves and others that whatever a situation is – it can´t possibly end well.

Trying reading German philosophy, history or even their literature for children and try to walk away feeling light-hearted – it can´t be done.

So when your humble blogger comes down with an ailment, however minor, my wife the doctor will roll up her sleeves and predict that my life has henceforth started in its inevitable decline and that only the strictest regime of medicine and rest will possibly give me a smidgin of a chance at survival.

I have known my wife for two decades and in this time I cannot recall a singular instance when I have ever won an argument.

Don´t get me wrong.

I still am foolish enough to fight, for like her I am equally stubborn and equally determined to presevere.

But after a Saturday shift at Marktplatz St. Gallen Starbucks, coughing, sneezing and blowing my nose caused my boss to send me home early and to cancel my Sunday shift at the St. Gallen Bahnhof Starbucks…

After an ill-fated attempt to conquer the teaching world two days later caused me to drag my frozen suffering shell of a man to Vaduz, Winterthur and Konstanz, leaving me wondering at my own sanity…

I finally capitulated, yet again, to the wisdom of my wife.

I stayed at home.

I stayed in bed.

But as I coughed and sneezed and sniffed and stuffed my body full with an apothecary´s supply of drugs, my mind remained active.

Translation: being sick at home is boring.

Staying in bed is uninspiring and unimaginative.

Now staying at home alone is not so bad.

Though talking on the phone was not recommended as my voice was somewhat diminished, lying on the couch watching old reruns of Cheers consoled me somewhat.

Having been raised by a Catholic foster father and a Protestant foster mother, having married a good German Catholic, this heathen blogger is torn between Catholic guilt and the Protestant work ethic.

Shouldn´t I be using this “leisure time” more productively?

I consider the daily routines of how great minds made time, found inspiration and got novels written, masterpieces painted and symphonies composed.

From 1908 until his death in 1922, Marcel Proust devoted the whole of his life to the writing of his monumental novel of time and memory, Remembrance of Things Past, seven volumes, 1.5 million words.

He withdrew from society and spent most of his time in the cork-lined bedroom of his Paris apartment, sleeping during the day, working at night.

He worked exclusively in bed, lying with his body almost completely horizontal and his head propped up by two pillows.

His only working light was a weak, green-shaded bedside lamp.

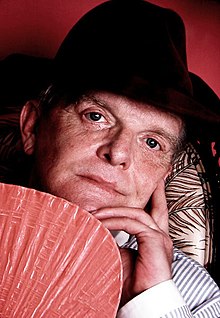

Truman Capote (1924-1984) told the Paris Review in 1957:

“I am a completely horizontal author.

I can´t think unless I am lying down.”

Even his typing was done in bed, with the typewriter balanced on his knees.

Literary legend has it that Edith Sitwell (1887-1964) used to lie in an open coffin for a while before she began her day´s work.

This foretaste of the grave was supposed to inspire her macabre fiction and poetry.

She liked to write in bed, beginning at 0530, and stayed there all morning and through the afternoon.

I curse my unambitious soul at times like this.

Outside more snow has fallen on the fields and streets of this wee hamlet of Landschlacht.

It is easy to remain indoors, hibernating in my self-imposed exile here in my comfortable cave.

I recall another scene, another bedroom, another view, another time, the story of a man half my age.

Rome, 2006

It is an exquisite piazza and we are tourists.

The famous Scalinata di Spagna, the Spanish Steps, has been a magnet for foreigners since the 18th century.

We were no less immune from its charms.

So many Grand Tourists have descended on this neighbourhood that it has come to be known as the ghetto de l’inglesi, the English ghetto.

Built in 1725 with French money, but designed by a Spainard and named after the Spanish embassy nearby, the elegant steps were built to connect the piazza with the eminent folk who lived above it.

At the foot of the Steps is the Barcaccia, the old tub fountain, made of marble, with continuous tumbling water enough to threaten a sinking boat.

The melodramatic Romantics were drawn to Italy, where little good befell them.

John Keats (1795 – 1821) came to Rome in 1820, desperately hoping that the Italian climate would improve his failing health and cure him of tuberculosis.

Keats and his friend Joseph Severn lodged on the second floor of the building on the right of the Spanish Steps.

This floor is now preserved as a memorial museum.

It was our honour and privilege to visit.

Keats’ family and friends hoped he would make a complete recovery, but he was increasingly convinced that his death was imminent and that he would never again see his friends, write his poetry and see his beloved Fanny Brawne again.

The piazza then was as it is today, a busy bustle of noise with the sound of traffic on the cobblestones and the striking of church bells punctuating the days.

Like other visitors before and amongst us, we visited shops and stalls round about the square.

Today people still hang about the staircase nonchalantly yet desperately eager to be noticed.

By late January and early February, Keats’ condition left him confined to his bed, totally weak, terrible night sweats, uncontrolled teeth chattering, hacking cough with thick expectoration, phlegm boiling and tearing his chest.

He suffered from violent mood swings.

At times, his mind was playful, cheerful and elastic.

Other times, Keats would sink into depression or display a malicious temper.

The hope of death seemed his only comfort.

At night, staring at the floral pattern on his bedroon ceiling, Keats felt the flowers growing over him.

Keats could see and hear the Barcaccia from his bedroom.

Its constant presence in his final days and nights would inspire Keats in the choice of words for his gravestone.

“This Grave / contains all that was Mortal / of a / Young English Poet / Who / on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart / at the Malicious Power of his Enemies / Desired / these Words to be / engraven on his Tomb Stone: / Here lies One / Whose Name was writ in Water. 24 February 1821″

Certainly I do not pretend to compare myself to Keats nor a mere cold to tuberculosis, but when I consider what this man accomplished in his short life span I am humbled.

Keats remains one of the most beloved of all English poets.

His poems and letters endure as the most popular and most analysed in English literature.

Keats was convinced that he had made no mark in his lifetime.

Aware that he was dying, he wrote to Fanny Brawne in February 1820:

“I have left no immortal work behind me – nothing to make my friends proud of my memory – but I have lov’d the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remember’d. ”

Landschlacht, 22 January 2016

As I leave Landschlacht and the comfort of my apartment, to once again reinsert myself back into the world, I think of what I have done with the half-century that has been my blessing.

I think of what I haven´t done with these past 50 years.

This will not stand.

The ease with which disease can strike a person only serves to remind me that the gift of Life is precious and must not be squandered.

I care not whether I am remembered, but I do not want it said that I wasted the few precious hours of my existence.

Capote, Keats, Proust and Sitwell teach me that it is not whether an appropriate time or place is found that matters.

It is not the success of what is written that matters as much.

It is the adventure of expression that defines a life.

I sit myself down at my computer and I begin to write.

(Sources: Mason Currey, Daily Rituals; Lonely Planet Rome; Nigel á Brassard, Keats in Rome; Wikipedia)