Landschlacht, Switzerland, 16 June 2016

“You can judge a nation by the way it treats its most vulnerable members.” (Aristotle)

“…the best test of a nation´s righteousness is how it treats the poorest and most vulnerable in its midst.” (Jim Wallis)

In St. Gallen stands a man, a beggar named Bruno, who hangs around outside the McDonald´s near the main train station.

No one is certain why he is there, day after day, regardless of the season or the weather.

Some say that he came from money and chose to be homeless, but it is easier to blame the poor for their poverty, then holding the rich accountable for a society´s inequality and unfairness in wealth distribution.

24, 000 people die every day from hunger.

3/4 of the deaths are children under the age of 5.

Is it somehow the children´s fault that they are poor?

Over one billion people have to survive on less than $1.00 US a day.

842, 000, 000 people across the world will go to bed hungry tonight.

Is this somehow their fault for their condition?

If so, then being poor is a choice?

If a choice, then shouldn´t it be outlawed?

Some communities seem to think so…

“Sussex Police has been accused of needlessly criminalising rough sleepers by using plain clothes officers to catch people begging on the streets.

They have arrested more than 60 people in Brighton for begging last year.

Critis argue that fines routinely imposed for begging offences simply increase the financial burden on rough sleepers, many of whom may have drug or alcohol abuse isses.

“People are effectively being victimized for sleeping rough. We have a ridiculous situation where homeless people are being arrested for asking for a few pennies, fined by the courts and then put back out on the street. These are vulnerable individuals being criminalised…” (Jason Knight, Brighton social worker / businessman)

“It is difficult to see why it is in the public interest to pursue these cases. I am not talking about aggressive begging or harassment but situations where people have asked for a few pence.” (Ray Pape, defence lawyer)”

(The Independent, 9 February 2016)

“According to the Economic Innovation Group, a nonprofit research and advocacacy organisation, the gap between the richest and poorest American communities has widened since the Great Recession ended and distressed areas are faring worse just as the recovery is gaining traction across much of the country.

From 2010 to 2013, employment in the most prosperous neighbourhoods in the US increased by more than 20%, but in bottom-ranked neighbourhoods, the number of jobs fell sharply. One in ten businesses closed down.

“The most prosperous areas have enjoyed rocket ship growth. There you are very unlikely to run into someone without a high school diploma, a person living below the poverty line or a vacant house. That is just not part of your experience.” (John Lettieri, Senior Director for Policy and Strategy, Economic Innovation Group)

By contrast, in places where the recovery has passed by, things look very different.

In America´s most distressed communities, the average house dates to 1959, population growth is flat or falling, more than 1/2 of adults don´t have a job and nearly a 1/4 lack a high school diploma.”

(New York Times, 24 February 2016)

So, for those in the ghettoes of America, is this poverty, this unemployment, this lack of education, really a choice that they made?

Here in Switzerland, in St. Gallen where much of my work occurs, Bruno is a quiet beggar who doesn´t say much, but, much like a street performing mime, he will suddenly explode into expression for what little charity he receives.

I am no Bruno.

I have a comfortable apartment, plenty of food in my kitchen, a warm, dry comfortable bed to sleep in, clean and undamaged clothing, access to regular hot showers and I can afford to amass collections of books, music and films which crowd our walls and floors much to my wife´s ever-growing dismay.

Unlike Bruno, I can afford to take the train and bus to the various places where I teach and I can afford to fly away somewhere for my vacations.

By comparison to Bruno, I am rich.

By comparison to poverty in the Third World, Bruno is rich.

Yet I probably don´t appreciate what I do have and could probably give Bruno far more than I do.

I see Bruno and I feel ashamed.

Not of Bruno, but of a community that is unable or unwilling to offer him a better life.

Not of Bruno, but of myself for the discomfort I feel when I interact with him.

Bruno is a man who, but for the grace of God, I could easily have become.

Heaven only knows how Bruno got here.

I can only guess that there is a world of experience and pain behind the rags and beard and unpleasant body odour.

It is easier to ignore Bruno and pretend he just isn´t there than to acknowledge why he is there.

I curse my inability to understand what he says to me, for though I have a working knowledge of High German, Swiss German is often as incomprehensible to me as Cantonese or Greek.

But some ideas filter through Bruno´s babble…

I know he sleeps rough, camping just outside the city limits, and trudges back into town every morning to visit soup kitchens and return to his post outside the Bahnhof McDonald´s.

I can only imagine what it must be like to be him.

For the educated, there are books written by brave souls who tried for themselves living homeless in lands of milk and honey.

Jack London, better known for his best seller The Call of the Wild and other adventure stories, was also a skilled political writer and social critic.

Posing as an American sailor stranded in the East End of London in 1902, he slept in charity houses and lived with the destitute and starving.

While other writers were celebrating the glories of the British Empire at its peak, Jack asked why such misery was to be found in the heart of a capital city of immense wealth and reported on his experiences in The People of the Abyss.

Eric Blair, better known by his pen name George Orwell, spent time in the 1930s amongst the desperately poor and destitute in London and Paris, documenting a world of unrelenting drudgery and squalor, sleeping in bug-infested hostels and flophouses, working in a vile Parisian hotel, surviving on scraps and cigarette butts, and wrote the powerful memoir Down and Out in Paris and London.

I am no Orwell nor Jack London, though I have seen some of this underworld for myself.

I have been homeless in the past as well as a drifter.

I have slept in charity houses in various cities in Canada and the States, in Britain and in France.

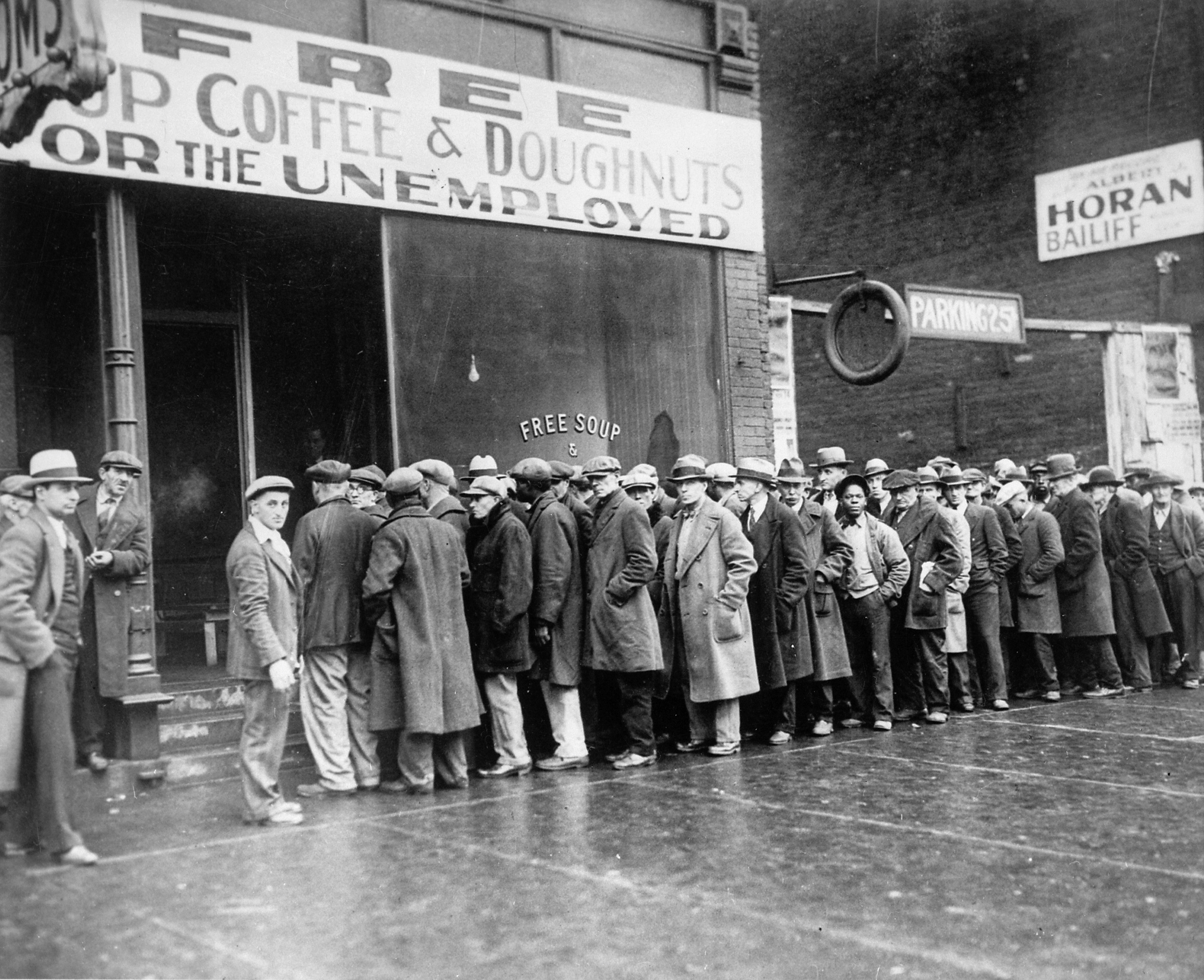

I have stood in line at soup kitchens and visited food banks.

I have never begged on street corners but never refused charity if offered an opportunity by kind drivers who gave me lifts in my hitchhiking travels in the States.

I have slept in places one would never imagine sleeping in or on: ditches, forests, fields, river banks and mountain tops, under stairwells and bridges, in tents and hostels, barns and stables, in prison cells and churches, on rooftops and in gutters, in shipholds and under parked vehicles, wherever sleep demanded.

But for me it was more adventure than adversity.

I hungered to see the world, but I knew I could never afford to do so, unless I simply set out without money and trusted fickle Fate to sustain me.

My story was more Jack Kerouac´s On the Road or Patrick Fermor´s A Time of Gifts than it was Orwellian Down and Out.

And somehow my overworked guardian angel protected me.

(I sometimes wonder had I not been white, would my story have been different?)

Of course, I have my tales to tell, but the despair, the anger, the hopelessness I have encountered in “places only ragged people know” (Simon and Garfunkel, “The Boxer”) remained somehow separate from my experience, much like living as a foreignor in a foreign land as I do now.

And in my travels outside North America and Europe, both literal and literary, poverty was encountered in more horrific ways than anything witnessed in the rich West.

Legless beggars wheel themselves on makeshift skateboards in the streets of Seoul and Delhi.

Flies gather round starving children in Africa whose mothers lacking nourishment for themselves cannot produce milk to sustain their babies nor even the energy to brush away the flies from eyes and mouths.

Nightfall finds street gangs gather and fight at knifepoint round the garbage dump outside Manila finding treasure in wealthy men´s trash.

(And these are the ravages of poverty…

I have never been to war nor spent time in a war zone so the horror and fear and terror and sorrow felt by soldier and civilian enmeshed in this nightmare scenario has been alien to my experience.

Though I have felt fear and anger in potentially violent scenarios encountered in my travels, my experience pales in comparison to what many folks experience daily worldwide.)

So when I see Bruno I feel both compassion and shame.

Yet somehow Bruno lives, and though his presence remains invisible to most of St. Gallen´s urbane citizens scurrying to and fro, I see him both as a reminder of what was and what could have been.

I count my blessings as Bruno blesses me for the change he counts as blessings.

Folks more fortunate look at Bruno, if they see him at all, seem him as a blight on the urban landscape.

“Why doesn´t he work?”, they ask.

But would they hire him?

And if they did, what would they have him do?

What could he do?

And would he want to do it?

For the working man´s lot, as much as we tell ourselves is better than Bruno´s condition, is for many not a pleasureable means to avert poverty.

For what dignity is preserved preventing us from begging, much pride is swallowed in dealing with those empowered to tell us what to do.

As profits fill the coffers of the wealthy, earned by the sweat and blood and toil and tears of others, few workers are shown the respect for their labour they are due.

The working man must seek his solace in wages begrudingly given.

And the harder the labour, the lower the wage and the compliments rarer.

Might some folks be wary of these conditions?

Bruno prefers to sleep in the woods covered by a tarpaulin rather than in a men´s shelter, for though he is exposed to the elements of unforgiving nature, and though his unwashed unshaven condition brings fear and disgust to some and makes him more celibate than a hermetic monk, at least in the woods there is freedom of thought and action.

In the woods there are no registration forms, no lectures and endless questions regarding the “purposelessness” of his life, no religious zealots to convince him to find Jesus, no litany of rules, no curfews, no rooms filled with snoring, wheezing, sneezing, burping, farting men, no dealing with self-important helpers who feel that giving charity makes them superior to those receiving charity and who wonder why the poor are not more grateful for their efforts.

Bruno is a man apart, alone by both circumstance and choice.

He may no longer believe that he can rise above his station in life, but it is a life that is his own.

He has denied shame and those that would wish to shame him.

His penury has made him both slave and free man.

And I don´t take his presence for granted, for I know should someone famous or something important show up in St. Gallen, Bruno will be strongly compelled by the powers that rule this city to move onwards.

Rio tries to hide its poverty just as Atlanta and Vancouver did before them.

But the poor return to the only lives they know and understand.

Let us not judge a man until we have walked many a moon in his mocassins.