Landschlacht, Switzerland, 18 July 2016

Somehow it feels like it’s time.

After decades of silence and sifting of memory, as more years lie behind me than ahead…

When the headlines of the moment evoke so much emotion and recollection within me…

I read of the injustice of America and its treatment of its minority populations by those who administer law and order.

I read of the fear of the American people of threats from not only abroad but from each other.

It’s time to tell the tale of Canada Slim as a prisoner.

I have few records of the years of my life before the 21st century began, as much of the memorablia of this time remains in a storage closet of my cousin in Canada, but should anyone with ambition ever one day be sufficiently curious to investigate the events I am about to recount I am certain through the magic of modern technology and diligent patient research be able to find records of my arrest, trial and imprisonment in Arizona.

To understand how a Canadian came to these circumstances I need to relate a bit of what came before…

I was born in St. Eustache, Quebec, Canada, at a time when my parents were going through marital difficulties.

The first decade of my life has few memories, but many years later I learned that my mother, an American, felt compelled to leave my father, a Canadian.

I cannot begin to comprehend the subtleties of what happens in relationships of which I am not a part of.

Neither can I condemn nor praise the female mind of which I, like many men, will never completely comprehend.

What little I know is that my mother was desperately unhappy and, seeking a freedom and a life that my father could not offer, left him and my siblings behind.

It is not even an absolute certainty whether the man listed on my birth certificate truly is my father, but if that is what the powers that be choose to authenticate then I have no desire to contradict.

She became ill and felt the call of her birth country, but Manhattan winters, like Montreal winters, are without mercy, so she chose to move down to Fort Lauderdale where she died of that beastly disease, cancer.

Though she tried to raise me on her own, financially and physically it was beyond her, so for the first decade of my life is a record of my being shifted from foster home back to her, to foster home back to her, to foster home to foster home to foster home…

I would finally be settled in a foster home in the countryside outside a wee village, actually similiar in size to the village I live in today, called, in full, Saint Philippe d’Argenteuil de la Paroisse de St-Jerusalem…even without the parish mention, the name required a long envelope…now simply called Chatham.

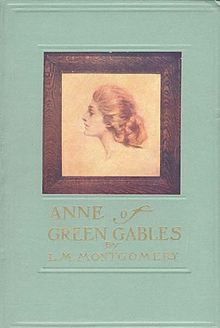

It was an unusual home I would spend my youth in, reminiscent in a way of how Lucy Maud Montgomery´s Anne of Green Gables was raised.

My foster mother was a spinster who needed a home.

My foster father was a bachelor who had a home but needed a housekeeper.

As she desired some financial independence she took in foster children as the province paid child support for their maintenance.

Adopting me would have meant that this support would be removed so I was never adopted and my name remained different from her name and his.

They tolerated me as long as I stayed out of their way and did what I was told.

They were not brother and sister but lived as chaste as if they were.

They were not emotionally remonstrative people, except when angry, but they gave me stability and for that I remain ever grateful.

Raising me my foster mother was convinced and often predicted that my destiny would go one of two ways: teacher or prisoner.

Like most women, of course, she was right.

I remained in St. Philippe until I was 18, (though graduating from high school when I was 17, as the financial support the province provided for my care was desired until it was no longer available) then I searched for a college where I could receive instruction in English but be as far away from St. Philippe as possible while remaining in the province of Quebec and its unique system of education.

I decided on a college in Quebec City, but then my past, which had been conveniently ignored, became crucial to discover.

As any identity thief or amnesiac might tell you, to go to college or to join the military or to work, one requires an insurance number.

It is a rare native-born Brit or American or Canuck adult that cannot rattle off his insurance number (National or Social depending on where you are from) by heart.

To get a SIN card (Canada´s name for theirs) one needs a birth certificate, but in all the kerfuffle of my first years somehow a birth certificate never got made.

Though the hospital where I was born had registered my birth I had no idea who my birthparents were as this copy was kept secretly hidden away by my foster mother who did not reveal its existence until she was compelled to reluctantly give it to me.

The province that supported my foster mother’s care of me and financed my studies now needed to provide legal aid to hire a lawyer and have a birth certificate created.

For sadly we live in a world where a person is said not to exist unless a document says so.

Furthermore documents can say who you are even if what these documents say is untrue.

My first adventure beyond my comfort zone, for the prospect of waiting two months for a SIN card to be produced and delivered made me impatient, I hitched from Quebec City to Bathurst, New Brunswick, and sat on government department office chairs and refused to budge without a SIN card in my possession.

To my amazement I had the card within 24 hours and hitched back.

But when I and the college decided to go our separate ways, the birth certificate and SIN card search had awoken within me a wanderlust that has never left me and a hungry curiosity to discover my origins.

I would have a period of time fighting these impulses by working for a time in Quebec City and then Barrie, Ontario, then returning to the regions of eastern Ontario and western Quebec and working in Lachute, Hawkesbury, Vankleek Hill and Montreal, while trying to be an attentive son.

Above, from top to bottom, Barrie, Lachute, Vankleek Hill and Montreal

But life had never been easy with them and in frustration, I fled, hitching to St. John´s, Newfoundland.

I found work in security at a fish processing plant, slept in a tent at a campground and spent my holidays walking through towns and hamlets on the Avalon Peninsula.

But I unwisely let my foster mother know where I was and shortly received a letter telling me to come back.

I did, but immediately regretted it.

I left then for good and never saw them alive again.

I decided to once again pursue my past prior to St. Philippe and discover where and who I came from.

From 1985 to 1990, journeys of discovery would lead me from Ottawa, where I “settled down” when money was needed from employment, to Key West, Florida, to Death Valley, California to Vancouver, British Columbia back to Ottawa…

Eight months hitchhiking and living on the road in a hand-to-mouth but interesting existence.

A second journey would follow that would find me hitching from Ottawa to Minnesota, along the Mississippi to St. Louis and New Orleans, east to Fort Lauderdale and back north to Manhattan and Canada.

In these two journeys I would learn about and meet my biological brothers and sisters and father and paternal grandparents and visit them in their homes in Alberta, Ontario and Quebec and visit the birthplace and final resting place of my mother.

(There would be a third hitchhiking adventure in northern Canada and Alaska, but this was unrelated to my heritage search.)

In the process I would learn that my maternal grandparents were Irish and English, which would lead to travels to Europe – where I have remained since the beginning of this century.

I had chosen to hitch, for I had limited funds and had this strange notion that I could experience similar moments akin to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, not realising that wherever I went there I was, and that much of what Jack described was a result of who Jack was.

When I think back to all those years ago I am amazed by a number of things: how I managed to survive, the generosity strangers can show, the spectacular beauty of the North American landscape and the uniqueness of the American character.

I entered the United States that first time via a round-trip bus ticket from Montreal to Plattsburg, New York, (I never used the return portion.) with $20 US in my pocket and re-entered Canada via Bellington, Washington, to Vancouver with only $20 US in my pocket.

In the eight months I travelled on thumb I slept and ate using the resources that charity organisations and kind strangers who gave me lifts offered me.

I remember meeting a fellow drifter who had developed a system he called “the Frank Method” that he had “invented” to travel around the country.

He hated charities like the Salvation Army types, for he felt that the psychological cost of staying at these shelters was more than he could stand, what with the danger and discomfort with sharing a dorm with other homeless folks – many of them violent and/or psychologically ill – and the guilt-laden preaching one often has to endure before one is allowed to eat a meal or rest one’s eyes.

I understood this, for this had been my experience as well.

For accommodation, he would deliberately consult a map of the states he intended to visit and he would only choose towns with populations between 10,000 and 30,000 people to seek shelter, for these towns were large enough to provide emergency accommodation but not large enough to justify having a homeless shelter.

Frank would approach the police and ask where he could spend the night.

They would call a church and the church would organise a hotel room, often including meals, for the night with the understanding that Frank would be gone the next day.

For meals, when absolutely skint for cash, Frank would pick a diner, what he called a “Mom and Pop establishment”, order a meal, eat it, then when presented with the bill, apologize for not having funds and offer to wash dishes or clean floors to make up for the cost of the meal.

He told me he had never been arrested for this nor did he often have to do chores for the meals he consumed.

When the road would produce no rides, Frank would trudge to the nearest railroad station, hop aboard a passing train and ride for free.

If approached by a ticket conductor he was either fined and the fine sent to a phony address he provided or he was forced to disembark at the next station, either way he had at least made some progress towards his chosen destination.

My background of being raised by strict Baptist foster mother and pennywise Catholic foster father has always left me with a bit of conservatism in my character, but I tried Frank´s methods when left with no other options.

I am neither proud nor ashamed of writing this, for I felt that I only needed food in my belly and shelter for usually only one night and would no longer burden a community longer than I had to.

True conservatives would argue that what I did was already asking too much, but when I had money I spent it only on food and shelter and when offered work I would work to make this money.

And truly if a community is so mean-spirited that offering a traveller a meal and a bed for the night is too much to ask, then that isn´t a community I would want to be in.

And I have noticed in my travels in North America and abroad that the poorer the area the more generous the people.

The more prosperous the area the more miserly the people.

But maybe the rich feel that wealth does not remain if given away…

Vagrancy – being a bum, a drifter, a hobo, homeless – is in parts of America considered criminally offensive.

I had heard rumours that folks hitching down in Georgia could be imprisoned and forced to work on a chain gang, but being forewarned I did not take the chance to test the truth of this by visiting Georgia.

I entered and exited Florida via the Panhandle – a thin strip of Florida that allows access to the state via Alabama bypassing Georgia completely.

I slept for the first time behind bars in a town in Florida, as no accommodation was available for drifters.

My belt and shoes and backpack were removed, a blanket and pillow and sub sandwiches given, the cell though unshared had a seatless metal toilet in the corner and both cameras and lights remained on throughout the restless night.

Though I had committed no crime, and my records were run to be sure, I was not allowed to leave the cell until the next morning.

It didn´t bother me much, for I was confident that I would be eventually released, and the cameras and lights were understandable for my temporary flop was meant for true criminals.

But being voluntarily incarcerated is a far different thing from being involuntarily incarcerated…

Tempe, Arizona, 1986

Now hitching a ride seems easy at first glance…

Stick your thumb out, a car stops, hop aboard.

One quickly learns to consider that a car needs to be able to safely exit the highway and find a generous road shoulder upon which it can slow down and stop.

Now how far as the law is concerned they see the situation a bit differently…

A hitchhiker on a freeway is dangerous for a number of reasons:

He could be struck by a vehicle, and at freeway speeds being hit could be fatal.

A car suddenly braking to a sudden halt on the freeway to pick up a hitchhiker could cause accidents.

And of course there is the unspoken question of why is he hitching:

Could it be he is a criminal who dares not use public transport or drive a car in case he is pulled over?

Some states have laws that clearly say that a hitchhiker can try his luck on the on-ramp or on the road leading to the on-ramp.

Hitchers know this is not practical, as there is usually little room for the driver to pull his car over safely.

Now one could try standard non-freeway type roads to reach his destination but those drivers that use these roads tend not to be long-distance travellers so a hitchhiker can wait a very long time to get a lift and will find it takes a very long time to reach his destination as numerous lifts are required.

But on a freeway a fortunate hitchhiker can usually get a long distance in a short time as those who use a freeway tend to want to travel long distances quickly.

My favourite lifts were pick-up trucks, for they offered easy loading and unloading of your travel gear.

The Holy Grail of free lifts are long-haul transport truckers, for not only do they normally travel long distances but could even radio ahead for other truckers to take the hitcher onwards from the drop-off point.

But for insurance and safety, many truckers will not pick up hitchhikers.

It is spring in Arizona and this Canadian is already sweating.

I am wearing a T-shirt, shorts, black army boots and a 50-pound backpack.

I am on the interstate south of Tempe, Arizona, standing on the side of the freeway.

An Arizona state trooper on a motorcycle pulls up alongside me and tells me to jump a fence on the side of the road that has barbs at its top and is taller than I am.

I do not respond quickly enough, so the young trooper grabs me by my backpack straps.

Oddly I am neither afraid nor angry but without thinking I grab the officer by the wrists, simply to stop him from pulling on me.

My feet are firmly planted and I stand a head taller than the officer.

I have no desire to strike the man but I resist his efforts to take my backpack off without so much as a request to do so.

I am Canadian so do not have any desire to be carrying any firearms.

I was raised rather conservatively so my backpack contains no drugs, no alcohol, no contraband of any kind.

I have only clothes and books in my backpack and have no problem with showing such, but I am annoyed that I am grabbed rather than asked.

An unmarked police car pulls up, witnessing our strange desert dance.

Four plain clothes men exit.

My feet are kicked out from under me, my arms twisted behind me, handcuffs are found and restrain my wrists.

The concrete is rough.

My backpack has come open and my worldly possessions exposed to the desert sun and scattered chaotically about.

The men gather my gear and toss it in the trunk of the car as I find myself pushed into the back of the car.

Except for the holding of the trooper´s wrists I have reacted non-violently and have meekly accepted all that is done to me.

There is a feeling of unreality to the whole situation, of disbelief.

To my own surprise I find myself calm and unconcerned.

This is such an odd situation that I am more curious as to what will happen next than I am as to my fate.

This serenity and curiosity will wear off.

I feel as if I am lying on the surgery table back in Montreal, when during my teen years I had accidentally cut my foot open with an axe and everyone was conversing to this Anglophone in French and interpreting my silence and confusion with shock rather than linguistic difficulty.

The law is talking English but somehow I am not listening, not comprehending.

My backpack has long disappeared and I am ordered around the station.

Fingerprints and photos are taken and I am thrown in a cell.

I would not taste the fresh air of freedom for half a month…

(To be continued…)

(Photo sources: Wikipedia)