Landschlacht, Switzerland, 22 July 2016

In the past five posts I spoke of prisons – how prisons inspire literature, prisons as tourist attractions, prisons as tourist accommodation, my work and life in a youth hostel/former jail, and the road that lead to me being imprisoned for a short time in America.

In this sixth and final installment I will attempt to describe what I personally experienced at the hands of law and order in the States.

I do this with extreme awareness of two dangers…

We live in a society where if one is not cautious one can find himself publicly shamed.

We live in a society where if one is not cautious one can find himself sued for libel.

To the first danger I can only say that though I served time in an American prison my “crimes” were considered misdemeanours and not felonies.

I do not possess a criminal record and I can enter the US freely.

To the second danger my only defense is the passage of time may have created different conditions today and the immediacy of those moments decades ago have left imperfect and impartial impressions in my memory.

Should this blog ever be read by those in law and order enforcement and be found to disagree with their experience I can only say in my defence…the account that follows is what I remember to be true.

I write this account not for financial gain and nor do I seek compensation from those who dealt with me in the manner that they did, but rather I am inspired by two basic feelings:

First, my own experience has lead me to a realization of just how easy it is to get oneself incarcerated.

If I, a pacifist and humanist, can find myself on the wrong end of the law, then perhaps there are many cases of prisoners unjustly incarcerated as well.

Second, my own experience leads me to believe that the attitude of US law and order is the reason that there are so many arrests and so many prisons in America.

My travels have shown me that, while there are far worse countries than America when it comes to enforcement and incarceration, there are also other methods in other countries that the US could learn from for its benefit.

When I think back to that Arizona interstate freeway and how the state trooper dealt with me I think I can see things from both his perspective and my own.

America is a troubled land, where too many of its citizens feel that a poorly-worded constitutional amendment gives them the “right” to carry death-dealing weapons.

Though every cop in every country knows that when he/she puts on a badge in the morning that a coroner might be examining his/her dead body that same evening, the possibility of death seems more pronounced in a country where so many citizens exercise their “right” to bear arms.

As mentioned in Canada Slim behind bars 5a: Arrested development, hitchhikers are regarded suspiciously.

Why would any sane, rational individual risk his life on a busy highway to get lifts from total strangers?

Perhaps other legal means of transportation mean the exposure of criminal intent?

The very act of hitchhiking suggests criminal behaviour to some people´s way of thinking.

I cannot imagine what it must be like to be a cop and see so many truly criminal individuals on a regular basis.

What is it like to be exposed to so much darkness, so much hate, so much violence?

Yet to a casual observer it seems that so much of a cop´s time seems mundane and routine.

It seems like cops seem endless amounts of time waiting for criminal activity to spur them into action, much like soldiers eagerly waiting for the order to attack yet ever mindful of the risks that this action entails.

To the young state trooper I must have seemed like a criminal, for why else would I be hitchhiking?

And when he grabbed me by my backpack straps and I responded by holding his wrists, I confirmed his impressions of my criminal intent.

When the plainclothes officers in the passing car saw the trooper struggling with a hitchhiker a head taller than himself, they “heroically” sprung into action to defend one of their own.

I, the hitchhiker, saw things differently.

The Canada of my experience is a different land, a different mentality.

Canadians, at least the “average” non-criminally minded Canadians, don´t see police officers as threats to our freedom but rather as guardians of our security.

From my encounters with Canadian police, though they too live in an atmosphere of potential danger, our police tend to treat Canadian citizens politely and respectfully.

If cops can be compared to dogs,(as they are in George Orwell’s Animal Farm) American cops are pitbulls, Canadian cops are beagles!

(Never underestimate the bite of a beagle!)

In Canada I think most Canadians respect cops as necessary and honourable.

In the US I think cops are more a symbol of fear and armed authority.

I cannot imagine a scenario where a Canadian cop would grab someone unless that person was actively doing something violent.

So when the overzealous trooper grabbed me by my backpack straps because I disagreed with him, there was a feeling inside me that what he was doing was wrong and I simply wanted him to stop grabbing me.

Somehow I had the strange notion that I could talk myself out of the situation, if he would simply stop grabbing me.

But I foolishly forgot the concept of “might makes right” – those who wield power feel that this power justifies and makes right whatever is done using this power.

It seems one cannot argue with the police regardless of the justice of one’s perspective.

People should meekly do what they are told and accept what is done to them, no matter how they may feel about it.

Herein lies my problem with law and order…

(Maybe I do have a criminal mind after all…)

If the laws are just and order is maintained respectfully then I have no qualms with policemen or transit authority or security personnel or judges.

But slavery used to be law, apartheid used to be law.

Capital punishment still reigns in many of the US states and torture is considered justifiable in some military or intelligence situations.

I said “No” to power and authority, “No” to law and order, and I was dealt with accordingly.

(And, sadly, it would not be the sole time when I found myself on the wrong end of the law…

That´s a story for another time…a time when I complain about the SBB – Swiss National Railways.)

I am a white Canadian.

I cannot imagine what it must be like to be a black American, to be harassed and hasselled on a regular basis, to be considered guilty and suspicious because of one’s skin colour.

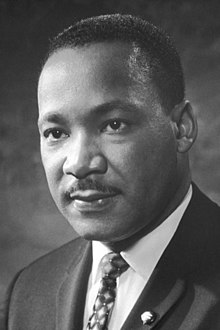

Above: Martin Luther King Jr. in 1964

A black man it seems is in far greater danger than a white man when challenging the authority of the police.

But if your experience with the police is so often negative even before your thoughts turned to acting outside of the law, then is it any wonder that some blacks might feel resentful and angry at the heavy-handedness of some police officers?

When a black person is prejudged to be criminal because of skin colour instead of character…

Or when a person´s character is judged by the colour of his skin…

When resisting arrest or arguing with a police officer seems to be justification for the officer to discharge a weapon and kill “in the name of the law”…

(It is not that black lives matter more, but rather that black lives should matter too, that they shouldn’t matter less.)

In a land where statistically blacks are denied the same opportunities for employment and advancement that whites take for granted, some are compelled to survive by acting outside approved legal means.

In the prison I was held in most prisoners were black, just as most prisons in the US hold predominantly black inmates.

And money buys the best legal representation, so those who can´t afford this end up behind bars.

And if being black means fewer opportunities to make the money required to get good legal representation, then it really isn´t a great stretch of the imagination to see how and why racial disparity exists in US prisons.

(I cannot imagine the difficulty that Islamic Americans must have to endure in this climate of irrational fear that presently prevades in the US.)

Tempe / Phoenix, Arizona, 1986

I am, that very day of my arrest, after fingerprints and photographs were taken of my person, transferred to a minimun security penitentary.

No one informs me of what I am charged with.

No one informs me of what I can expect nor exactly where I am going.

At the prison the last vestiges of my identity are taken from me and an orange coverall is found in my size.

(I can´t recall if socks, shoes or underwear were included.)

The cell I would spend a fortnight in was neither spacious nor cramped.

I remember it had a table, two chairs, a toilet and two bunk beds.

I don´t recall seeing either a television or a radio.

My cellmate, a man in his 40s, was imprisoned for not paying alimony.

“Arthur” claimed his wife left him for another man and when this other man found himself unemployed he moved in with “Arthur”‘s estranged wife.

Now supporting two, his wife expected “Arthur” to pay for her and her boyfriend.

Feeling that he was the injured party, “Arthur” refused.

The courts did not agree.

Being three decades removed from the events of 1986, I cannot recall with accuracy the hours by which we were regulated or the content of the meals.

(I don´t believe the Michelin Guide gave the prison any stars!)

Neither can I recall with any certainty whether we as prisoners gathered together in a communal dining room or whether meals were brought to our cells.

(I only have a feeling it was the latter…)

I remember showers were communal but I don´t think we were allowed them on a daily basis.

I do recall with vividness being bored with my confinement very quickly and how much I appreciated that paperbacks were available from a passing book trolley and that I was granted a blue pen and a yellow notepad to record my thoughts.

I had the bottom bunk.

Nights were cool, blankets scratchy, linen clean.

I did not feel afraid of my cellmate, for he did not strike me as a violent type.

“Arthur” standing was about 5’6″ and he seemed thin under his coverall.

I never thought of having to fight him nor whether I could win should it have been required to do so.

I have rarely fought nor had/have any desire or talent to do so.

I quickly gained his friendship by giving away the cigarettes each prisoner was allotted as I didn´t smoke and the thought never occurred to me to use cigarettes as currency.

There was no demand made of me to do any labour to “rehabilitate” myself, though I think I would have welcomed it as at least I could have gotten the feeling of doing something productive with my time.

There was an opportunity for recreation – a yard where we all were required to spend some time in the afternoon.

It had a basketball court with two baskets and a basketball provided.

Though I possess the height to be a basketball player I lacked the talent and the co-ordination of one, so I remained on the sidelines watching young black men dominate the game with a flair and accuracy that left me breathless and envious.

I discovered and devoured the works of Clive Cussler, Gregory Macdonald, Louis L’Amour, Tom Clancy and James Michener, in all their dog-eared, well-thumbed, ratty and ripped covers, paperback glory.

I kept my head down and my mouth shut, speaking only to my cellmate on occasions when he needed to talk.

There was nothing to do, but read, write, eat, pee, poop, sleep, repeat, in the cell.

Little to do, but wait and watch the shadows on the walls and the lights in the building to determine the slow passage of day into night, dusk into dawn.

Time passes and only my record on yellow notepad attests to its passing.

Then on the 10th day I am summoned.

My ankles are cuffed as are my hands.

A long chain connects the two sets of cuffs and another runs between my legs connecting myself to another orange-suited inmate.

We are driven into the city.

The prison wagon halts in front of the courthouse and we are marched outside in broad daylight from the street sidewalk into the basement of the courthouse.

It is the scene of a nightmare that only Dante or Bosch could dream of.

Above: “The Last Judgment” by Hieronymus Bosch, 1500 – 1505

Every type of convict, from minimum to maximum, from newbie to hardened con, from the harmless to the violent, are all gathered below.

If the intention of taking me to this hell was to invoke fear, then it was successful.

I see a con strapped to a chair, resisting violently, loudly, six burly guards can barely restrain his passion, his madness, his fury.

I am led to a large courtroom with row upon row of similiarly orange-suited cons, dozens upon dozens, a sea of orange.

Then and only then do we learn of our right to remain silent, our right to an attorney.

Rights read, we are separated.

I am led to a cubicle where a man in a fancy three-piece suit informs me that he is a judge.

I learn that I am accused of disorderly conduct and failure to obey a police officer.

How do I plead?

I don´t feel like I have merited prison and just want out.

If I insist on pleading “not guilty” then I will wallow in prison until a trial can be arranged.

I am offered “no contest” as an option, meaning though I am not admitting culpability or guilt I will not fight the decision of the court.

The judge dismisses the charge of disorderly conduct and tells me that it is his judgment that I have served time for the second misdemeanor.

I am led back to the cellar, then back to the wagon and driven back to prison.

Four days pass.

11 pm on the 4th day after my courthouse visit I am released.

My clothes are returned to me, but my backpack remains in police storage in Phoenix.

It is pitch black night and the open sky is filled with stars.

I had been arrested wearing boots, shorts and T-shirt in the middle of a hot sweaty day.

These same clothes provide little warmth on a cold desert night.

Another con just released and met by his girlfriend’s car gives me a lift to downtown Phoenix.

I am penniless with only the clothes on my back.

No shelter, had I known where to find one, would take me in at so late an hour at night.

I spot a Holiday Inn side door open and sneak in before the door closes.

I find a quiet stairwell and crawl underneath it with remnants of newspaper wrapped around me for inadequate warmth.

It is a restless uncomfortable night.

Morning comes and after much searching I find the police station where my backpack was stored.

All has been restored, though it takes some time to return to the order in which my backpack had been maintained before Arizona State took an interest in me.

There is food and water and clothes and books still stored within. but what money I had had no longer remains.

I want to leave Phoenix far behind, but my troubles are not over yet.

Surrounding the city are signs telling drivers: “Federal Prison Zone: do not pick up hitchhikers”.

I walk and walk north out of town until night falls.

Under the highway I spot a drainage tunnel.

I crawl in and settle myself only to realise that I am not the sole occupant of the tunnel.

Another young man is at the other end.

We don´t speak.

It takes me many hours to fall asleep but upon awaking I find my tunnel neighbour has gone.

Hours later I am finally outside the zone and once again I find myself back on the interstate hitching.

Clearly the rehabilitation was ineffective.

I finally get picked up and resume my journey, heading west to California and north to Canada.

Looking back I realise that my prison experience was tame compared to other prisons I might have been a resident of.

Since then I am wary of police officers and generally try to avoid obvious activities of an illegal nature.

The whole experience brought me no honour nor caused me any shame.

It was both real and surreal at the same time.

An adventure is only an adventure in the telling.

Above: Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable try to hitchhike in It Happened One Night (1934)