Landschlacht, Switzerland, 12 August 2016

In my last blog post, Yesterday’s Children, I wrote of boarding a train to parts unknown in an attempt to restore my composure after attending a memorial service in Benken, Canton St. Gallen.

The day then was much like today’s weather: chilly, dark, unpleasant…

Glarus, Canton Glarus, 21 March 2016

Glarus, the smallest Canton in Switzerland, nestles between high mountains, the Schwyzer Alps to the west and the Glarus Alps to the east.

This is Switzerlands’s least-known and supposedly hardest-to-reach region, a tract of territory with just a scattering of widely-separated settlements and very low key tourism.

Its isolation is its attraction – a place to turn your back on the crowds and breathe in the fresh air of the wilderness.

It is possible to bypass the slender, cliff-girt Walensee – (though why one would desire to do so is a mystery, for the lake is remarkably beautiful) -by both car and train.

Ziegelbrücke, at the lake’s western tip, marks the start of routes squeezing southwards.

12 km south, Glarus, the smallest canton capital city in Switzerland, is a picture postcard place, dwarfed and intimidated by the looming Glärnisch massif, dwarfed and intimidated by the rest of Switzerland, which in turn as a landlocked fortress island surrounded by Europe, feels dwarfed and intimidated by the world.

Now all the English-language guidebooks (Rough Guide, Lonely Planet, etc.) suggest that, with the notable exception of the first Sunday in May when Glarus holds its Landsgemeinde (public Parliament), there is little reason to visit Glarus, but instead one should travel on southwards to scenic Linthal, the Klausen Pass towards Canton Uri, and the lovely and lonely enclosed valley of Urnerboden.

(See Railroads to Anywhere: Urnasch and Appenzell of this blog for a description of how a Landsgemeinde works and why seeing one is worthwhile.)

And one day I will return to Glarus to do just that, to see what lies to the south of Glarnerland.

But this day, after attending a funeral, the very anonymity, the isolation of Glarus held a greater attraction for me than places more frequented by tourists and greater praised by travel literature.

I could have reached Glarus on foot by simply following the Linth River from Benken, for Glarus lies on the river Linth.

My imagination likes to think that this is how St. Fridolin did it in the 6th century.

According to the legend, the inhabitants of the Linth River valley were converted to Christianity by the Irish monk St. Fridolin, who, after founding Säckingen Abbey in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, decided to keep travelling and keep on converting those he met during his travels.

Fridolin belonged to a noble family in Ireland and at first he was a missionary there.

Afterwards crossing to France, Fridolin came to Poitiers, where in answer to a vision, he sought out the relics of St. Hilarius and built a church for them.

St. Hilarius subsequently appeared to Fridolin in a dream and commanded him to proceed to an island in the Rhine river where Säckingen now exists.

In Switzerland, Fridolin spent considerable time where he converted the landowner Urso.

On his death Urso left his enormous landholdings to Fridolin, who founded numerous churches all dedicated to St. Hilarius (the origin of the name “Glarus”).

(Yes, Fridolin’s mentor’s name sounds hilarious!)

Urso’s brother Landolf refused to accept the legitimacy of the gift and brought Fridolin before a court in Rankweil to prove his title.

Fridolin did so by summoning Urso from the dead (!) to confirm the gift in person, so terrifying Landolf that he gave his lands to Fridolin as well.

From the 9th century, the Glarus region was owned by Säckingen Abbey until the Habsburgs claimed all the Abbey’s rights by 1288.

St. Fridolin has never been forgotten.

Glarus joined the Swiss Confederacy in 1352.

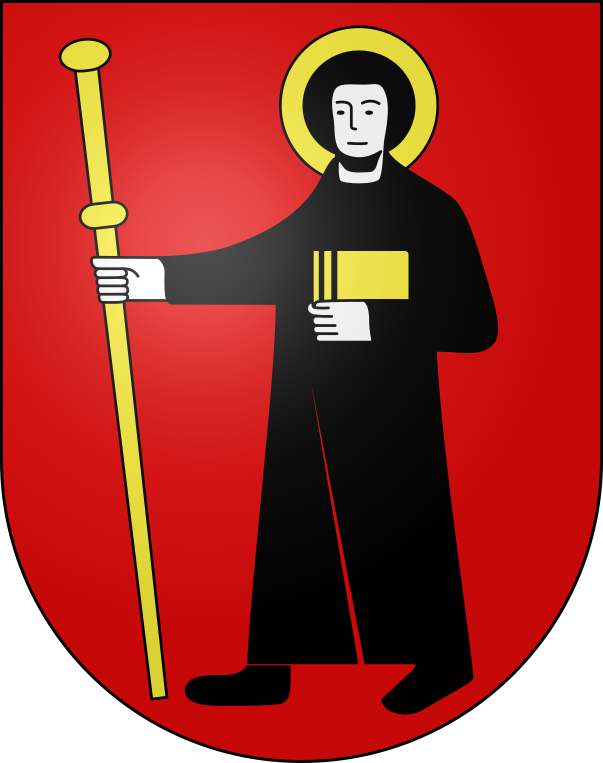

Habsburgian attempts to reconquer the valley were repelled in the Battle of Näfels in 1388, where a banner depicting St. Fridolin was used to rally the people of Glarus to victory.

The Battle of Näfels, the last battle of the Old Swiss Confederation vs the Austrian Hapsburgs, fought on 9 April 1388 was decisive despite the forces of Glarus being outnumbered 16 to 1!

2,500 Austrians died.

Only 54 men of Glaurus were killed.

From that time onwards Canton Glarus has used the image of St. Fridolin on its flags and in its coat of arms.

In 1389, a seven-year peace was signed in Vienna and that same year the first Näfelser Fahrt, a pilgrimage to the site of the battle was held.

This pilgrimage, which still occurs, happens on the first Thursday of April in memory of this Battle.

Between 1506 and 1516 the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli was priest in Glarus.

It was his first ecclesiastical post.

(To read more about Zwingli, see City of Spirits and Reformation by the River and the Railroad Tracks of this blog.)

It was in Glarus, whose soldiers were used as mercenaries in Europe, that Zwingli became involved in politics.

From 1500 to 1800 a main source of income for Glarus came from its mercenary soldiers.

Close to 1,000 Glarner became officers, acquiring fame.

A far greater number lost their lives as soldiers in foreign service.

The Swiss Confederation was embroiled in various campaigns against its neighbours: the French, the Habsburgs and the Papal States.

Zwingli placed himself solidly on the side of the Papacy.

Zwingli was a chaplin in several campaigns in Italy, including the Battle of Novara (6 June 1513).

However the decisive defeat of the Swiss in the Battle of Marignano (13-14 September 1513) caused a shift in mood in Glarus in favour of the French rather than the Pope.

Zwingli found himself in a difficult position and decided to retreat to Einsiedeln, Canton Schwyz.

By this time, Zwingli was convinced that mercenary service was immoral and that Swiss unity was indispensable for any future Swiss achievements.

While Zwingli was not a reformer at Glarus, it was there he began to develop the ideas that would lead him to break with the Catholic Church.

In 1528 the Reformation gained a foothold in Glarus, directed by Zwingli who had moved to Zürich in 1518 after two years in Einsiedeln.

Even though Zwingli had preached in Glarus for 10 years, the town remained strongly Catholic.

However, following the Second War of Kappel in 1531, both the Catholic and Protestant residents were given the right to worship in town.

This led to both religious groups using the town church simultaneously (!), an arrangement that caused numerous problems.

In 1782 a “witch” was executed for the first and only time in Glarus and the last time in Europe.

A five-man jury sentenced the accused maid, Anna Göldi, to death by sword.

(See Five schillings’ worth of wood of this blog about witches in Switzerland and abroad past and present.)

In 1798 Glarus became a battlefield for foreign armies leading the Confederation to surrender to French occupation.

This war brought with it misery and destitution.

In 1799, 1,200 children were forced to seek food and shelter in other cantons.

By the 18th century both groups still shared the same church but had separate organs (!), both financially and theologically independent parishes meeting in the same city church (!).

This neo-Romanesque church is the symbol of the city.

In the early 1840s, after several years of bad crops and scarcity of food, much of the Canton found itself deep in debt and poverty.

With more workers than available jobs, emigration to the United States was seen as a solution.

The Glarus Emigration Society was established in 1844, offering loans to help residents purchase land in the New World.

Many of the resulting emigrants went to the state of Wisconsin, where they founded the town of New Glarus.

Above: Jodellers and Alphorns are all part of the New Glarus Swiss Volkfest.

(Despite its small size, 2,2oo people, New Glarus is known for many traditional Swiss dishes (like Rösti, Kalberwurst, Spätzle, Landjäger, Brätzli, Bratwurst, fondue, Älpermagronen, Zopf, Chäschüchli, Schnitzel, chocolates, Stollen, etc), its many festivals (including a Polkafest, Heidi Festival, William Tell Festival…), the Swiss Village Historical Museum, the Swiss Center of North America, Swiss chalets with flower boxes filled with red geraniums, Swiss flags flying next to the American flag, the card game Jass, yodeling, flag tossing…)

(See The cards we’re dealt of this blog for a description of the card game Jass.)

In short, New Glarus, Wisconsin, is the best-known Swiss settlement in America.)

On the evening / early morning of 10 / 11 May 1861 the town was devastated by a Great Fire that was fanned by a violent Föhn (a south wind)(known as a Chinook in Canada), destroying 2/3 of the town (593 buildings in total) with 3,000 people losing their roofs and everything they owned.

Very few buildings built before the Great Fire remain.

(New Glarus collected money for Glarus.)

In 1864, the first European labour law to protect workers was introduced in Glarus prohibiting workers from working more than 12 hours a day.

(In 1880, when much of the nearby town of Elm was buried beneath a landslide killing 114 people, the residents of New Glarus again sent money.)

On 6 May 2007 Glarus became the first Canton to lower the voting age to 16.

Today wood, textile, printing and plastics are the dominant industries.

Most of the 13, 000 residents speak the local Swiss German dialect, most of them are over 20 and under the age of 64, and are highly educated.

And the town of Glarus, not to mention the canton of Glarus, produced some remarkable people:

Ägidius Tschudi (1505 – 1572) was a governor of Sargans and Baden, the defender of Catholicism during the chaos of the Reformation, ambassador, hospital founder, geographer and historian.

Tschudi’s maps were far superior to those up to his period in exactness and he is considered to be the Father of Swiss History.

Another Tschudi, one Johann Jakob von Tschudi (1818 – 1889), was a medical doctor, diplomat, natural scientist, South American explorer, zoologist, hunter, collector, antropologist, cultural historian, language researcher and a Swiss business executive in Vienna.

After his explorations through South America, Johann took up the cause of Swiss and other European immigrant residents of Brazil who were treated no better than slaves.

Johann’s travels through Peru, the Cordilleras, Brazil, Argentina and Chile have been compared to the accomplishments of pioneers in science.

Fritz Zwicky (1898 – 1974) was a physicist.

In fact Zwicky was one of the most esteemed astrophysicists of the 20th century, creating the “Morphological Method”, this Professor at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena made discoveries in rocket technology, publishing many scientific papers and his biographical Every Person a Genius.

When researchers talk about neutron stars, dark matter, and gravitational lenses, they all start the same way:

“Zwicky noticed this problem in the 1930s.

Back then, nobody listened…”

(Steven Mauer, Idea Man)

The Glarus Public Library and the Fritz Zwicky Foundation house his personal library.

As well, this town has produced Olympic calibre cyclists Peter Vogel and Colin Stüssi, Olympic gymnist Melanie Marti and racing driver Urs Sonderegger.

Clearly a remarkable place filled with remarkable people…

Yet few travel books make remarks about either the town or the canton called Glarus.

And I have mixed feelings about this, for as much as I wish others to enjoy Glarus as much as I have, there remains a part of me that wants to keep this enjoyment as a private pleasure.

For the tourist the town has much to offer: the Museum of Art with its collection of 19th / 20th century Swiss artwork and Pablo Picasso’s “Tete Bleue”, the Museum of Natural History, the Holenstein Cultural Centre, the Tschudi Art Gallery, the Pitoresk Gallery, the Suworow Museum, the Kantonschule Observatory, a park and a sports centre offering ice-skating, curling, jogging, field athletics, cycling, downhill skiing, sledding, swimming.

The Spielhof, the former State School, with its Soldenhoff Room, exhibits the major works of painter Alexander Soldenhoff (1882 – 1951), while its library and archives include the Blumer Atlas Collection, astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky’s personal library and Professor Arthur Dürst’s geographical collection.

As well, the Romanesque mountain chapel dedicated to the Archangel Michael dates back a thousand years, with a Roccoco altar of dark marble showing Michael hurling Lucifer into Hell’s fire while Maria and Joseph with the Christ Child look on.

White marble statues of Glarus’ patron saints Fridolin and Hilarius share devotion with Zürich’s patron saints Felix and Regula who found refuge in a nearby cave that bear their finger impressions on the walls.

Fortress Hill offers a scenic view of the town and vineyards cling to the hillside.

And nearby, a beautiful lake in a valley ringed by magnificent mountains with hiking trails, campsites, a boat dock, windsurfing and ice skating, arched stone bridge and hydro dam, limestone caves, peaks, gorges and waterfalls have inspired poets and painters for generations.

This is the Klöntal, where a memorial stone reads “here the goats – here the border” and a rough stone block bears the inscription: “Salomon Gessner wished to create a monument to nature, thus nature allowed his name to be recorded here for all eternity.”

But perhaps I have underestimated the good folks of Glarus…

Glarners have wisely decided to keep Paradise mostly private.

Perhaps in Glarnus every person is a genius after all…

(Sources: Wikipedia; Switzerland Tourism; Josef Schwitter/Urs Heer, Glarnerland: A Short Portrait)