Landschlacht, Switzerland, 18 August 2016

As those who read this blog regularly know, I enjoy hiking in nature: fresh air, surprising encounters with flora and fauna, the solitude that allows me the freedom to simultaneously think as well as forget about the problems of Life for a while.

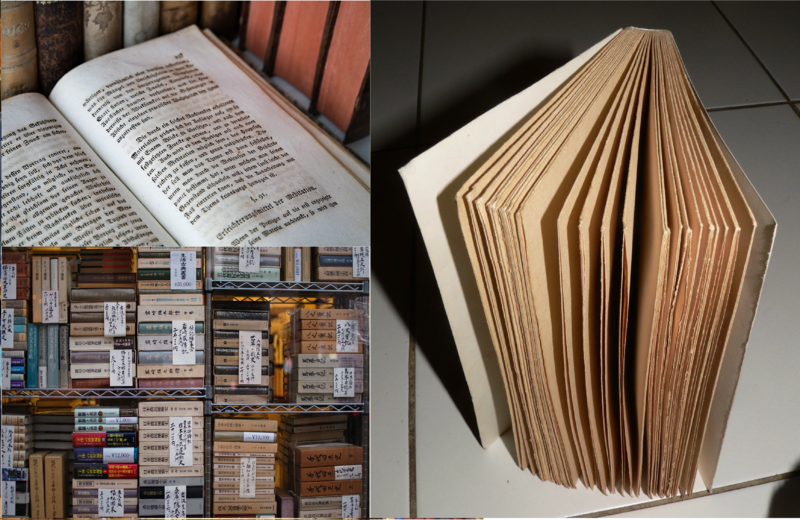

But I have another addiction, another obsession, I enjoy: shopping for books.

And when moments present themselves when I can combine both these passions, when I can find books during one of my hikes, well, this is what I call a good day.

I have recently begun a small walking project – as part of a larger ambition to walk and explore Switzerland as much as I can…

After having seen the Linth River three times previous to this project – in Benken (See Yesterday’s Children of this blog.), in Glarus (See Glarus: Every person a genius of this blog.) and flowing into the Obersee of the Lake of Zürich (to be discussed in a future post) – I have decided to follow the length of the Linth from Linthal in Glarus back to the Zürichsee.

As my walks are done on days when I am not working or otherwise committed to some other activity, I find myself walking on odd days and in separate stages.

On Monday I walked from Linthal to Luchsingen, with a visit to Klausenpass and Braunwald.

Yesterday I walked from Luchsingen to Glarus.

I thoroughly enjoyed these hikes for they led me not only beside a majestic flowing river through forest and field, but as well they led me to book donation boxes and a second-hand thrift shop.

I love serendipitiously finding these sorts of book collections, for not only are the books free or inexpensive but often one can find books that are out of print and are no longer published.

In the Braunwald book donation basket I found Racing through the Dark: The Fall and Rise of David Millar, the autobiography of a professional cyclist and how he got into doping.

In the Schwanden Bröcki (a Swiss Salvation Army type thrift shop) I found Edmund White’s City Boy: My Life in New York during the 1960s and 1970s.

Also an autobiography, it is the story of a young LGBT writer who mingled with people like Bob Dylan, Susan Sontag and Mama Cass in a time when being LGBT was more hidden than celebrated.

Though not being LGBT myself, I can relate to the struggles White describes in trying to be successful while remaining true to himself.

I also found an 1908 Guide Joanne Suisse (Think of Baedeker but in French.), which fascinates me with a time travelling glimpse of the familiar a century ago.

David Millar’s story has made me think of substance use and abuse and what an athlete’s life is really like.

Houston hosted the world weightlifting championships last year.

The sport’s greatest athletes, many Olympians among them, hoisted staggering amounts of weight above their heads, their feats looking superhuman.

Seventeen of the weightlifters who competed in Houston – including many medal winners – tested positive for banned drugs, so what the fans saw wasn’t a credible sport at its best, but instead they saw a lot of cheating.

This applies to Olympic sports more broadly now, in the wake of extraordinary claims by the former director of Russia’s antidoping laboratory, who said that a state-run doping program assisted dozens of Russian athletes during the 2014 Sochi Games.

These claims have driven antidoping officials to reexamine urine samples from previous Olympics and there have been 31 new positive tests from the 2008 Beijing Games so far.

We know this from experience.

The Olympics have survived scandals like this before: East Germany’s doping machine, Ben Johnson’s failed drug test, the Balco steroids case that ensnared some of the biggest names in track and field – including multiple Olympic gold medal winner Marion Jones.

Cycling is one sport that shows lasting damage from doping.

Drug scandals over the past two decades have knocked the sport to its knees.

Nearly every top rider has been implicated, Tour de France jerseys stripped, sponsors fleeing, teams folding, the public’s confidence shaken.

In 2007, two German public TV networks pulled their broadcasts of the Tour de France because they didn’t want to televise a sport fueled by pharmacology.

In 2012, when Lance Armstrong was exposed as an unrepentant doper, even casual observers considered the sport to be a complete fraud.

Jonathan Vaughn, one of Armstrong’s teammates who helped reveal Armstrong’s sophisticated doping program, said he was exasperated.

The truth had come out about doping, which was good for clean athletes, but there was a painful downside.

“The first people you hurt if you stop watching a sport because of doping are the clean athletes in it. You are literally pointing a gun at those athletes and are shooting them in the head, when they don’t deserve it.”

The Olympic sport hit hardest so far by investigations into Russia’s doping program is track and field, but it’s not alone.

Athletes in bobsledding, weightlifting and cross-country skiing have also been implicated.

The former Russian lab director said the entire women’s ice hockey team was part of the state-run doping program in Sochi.

The list goes on and on.

Jim Scherr, former chief executive of the US Olympic Committee, said the public must understand that most athletes are clean, and that the Olympics stand apart.

“We’re different than a league founded for entertainment, to make money. The Olympics were founded to make the world a better place.”(New York Times, 19 May 2016)

So why do athletes dope?

Before discussing this we need to be clear about separating athletic performance-enhancing drugs from other drugs, and permissible drugs from banned drugs.

Do you, gentle reader, take drugs?

Chances are strong that you do, for even easily-purchased and easily-obtainable substances like sugar and coffee and variations on this theme are substances you consume to keep you awake or to give you more energy and so by the strictest of definitions could be considered drugs.

Alcohol and nicotine are also quite common in Western society and no one questions that these substances are not used as fuel to sustain our bodies but rather are used to affect our body chemistry.

And addiction is everywhere ever present.

Kingsport, Tennessee, where the Appalachian mountains cross into eastern Tennessee, this factory town of train lines and hills and shopping centres full of franchises, seen on a map listing drug overdoses, is the town with the most deaths in the United States.

The area has become overrun by the demand for illegal drugs, tranquilisers and opoids, such as heroin, morphine and codeine.

Kingsport is a town overrun with pain, lives upturned, dying from addiction.

Drugs enter as hope exits.

Appalachia is awash in despair and hopelessness.

With the closing of coal mines and management laying off many workers, folks have little to sustain them and simply wish to forget their emotional pain. (The Guardian, 10 May 2016)

So why do the folks of Kingsport do this damage to themselves?

Granted we are a society where self-image is often tied to our ability to work, living in a world filled with disposable goods and discouraging in its bland ordinariness.

But as well I think that, despite technology enabling us to communicate with others faster than ever before, we have over the past two generations lost our integration with our communities.

Many of us have lost the sense of a place’s uniqueness, of belonging to a place.

We have lost our enthusiasm for the future, expecting it simply to be an extension of an imperfect present and a repetition of an undesireable past, an endless highway of tears stretching out to a bleak horizon empty of promise.

Despair is everywhere, and no longer relegated to large urban cities and ghetto alleyways.

It can be found in a Kingsport bar or in a First Nations reservation.

Since last September, over 100 people in the Attawapiskat First Nation around James Bay, have attempted suicide.

Their culture eroded and belittled, living in poverty and lacking proper housing and proper health care or access to clean drinking water, men and women, young and old, have tried to kill themselves. (New York Times, 12 April 2016)

For some, religion, Karl Marx’s “opiate of the masses”, brings comfort.

And though the greatest proof of the existence of divinity is the inability to disprove its existence, faith sustains the believer.

But is it despair that drives an athlete to take banned performance-enhancing drugs?

Partially.

To train your body for so long, to discipline your life so intensely, all in the hopes that your efforts will be rewarded by victory over your competition and recognition by the many, and then not to receive reward and recognition for your regimen is a depth of discouragement that even non-athletes can understand.

And those few who do get the adulation and awards feel such an intense joy and excitement that they do not want this feeling to disappear.

Both the successful and the unsuccessful crave an edge, an advantage, something to sustain and improve their abilities.

And this pressure to excel not only comes from within, but as well from without.

For as the athlete has invested his time and energy in his quest for excellence, others have invested vast amounts of money and hope in the athlete as well.

The wonder is not that so few athletes seem clean these days.

The wonder is that there aren´t more that are dirty.

When I think of fallen heroes like Ben Johnson and Lance Armstrong, I do not feel angry.

I feel only sadness and pity, for they have lost everything that once gave them happiness.

Long gone are the days when athletes simply did a sport for its enjoyment, unconcerned with outcome, just playing for fun’s sake.

We, the non-athletic masses, idolize our sports figures, little knowing or caring how much our heroes have sacrificed for our adulation.

We view these mere mortals as more than mortals, as superhumans among us.

We think that their success as athletes means our superiority as nations.

We cannot fathom how it feels to have an entire nation’s hopes pinned on our achievements.

We have forgotten that athletes are prone to the same fears, doubts and pressure ordinary humans feel.

We tend to forget that athletes are often more frail than us, that their unique situation has made them not as human as us, but more human than us.

Super human.