Landschlacht, Switzerland, 2 September 2016 / 15 September 2016

Homer once said that all men have need of the gods.

And maybe this is so, for since time began we have sought a way to understand, and perhaps even influence, powerful natural phenomena, such as weather and the seasons, creation, life, death and its aftermath.

There are times I wonder whether God created man or whether it was man who created God, but to religion’s credit its rituals give many lives a deep sense of identity, cement social groups and bring meaning to the rites of passage in life, such as birth, maturity, marriage and death.

Religion has also been used as a political tool, justifying military conquests, giving courage in battle and comfort in loss, and will even pervert itself in its own name where murder, though morally wrong, is justifiable if the cause is just and holy.

Religion organises life – through calendars, rites, rituals and taboos – and death – by suggesting that our lives have significance and role in the cosmos.

People will defy princes, powers and principalities, suffer persecution and even court death to defend their rights to worship with their chosen rituals their perceived divine providence.

For many, religion is not just a social impulse, it is also a matter of intense personal experience – a search for significance and meaning through an inner awareness of the undefinable divine.

We seek meaning to the trials and tribulations of life and solace in something that shows that individuals matter on a cosmic scale – if not in this life with its injustice and unfairness, then in a prospect beyond the grave.

For it is hard to remain strong within ourselves in the face of pain and suffering and then to face an eternity of nothingness where all that we were and all that we could be is mere rotting remains in some forgettable tomb and meaningless like dust in the wind.

In this paradoxical existence we want to believe that there are unseen forces at work, that sense can be made of the world, that we matter.

I am not much of a churchgoer, much to the despair and grief of religious friends and family.

They wish to bring me closer to them in spiritual harmony and hope to give me the same hopes that they fervently cling to.

They have found fulfillment in their group and fear what exclusion from their group might mean to my spiritual future.

But it is this religious grouping I object to, rather than the religious beliefs they espouse, for the dark side of organised religion is the creation and segregation of humanity into two basic sides – “Us” and “Them”.

And it is this division that condemns anything that is not believed and practiced by “Us”, resulting in many using religion as a cloak to disguise thought and actions that are very unreligious in practice.

Kill, in the name of religion.

Force others to bend to your will, in the name of religion.

Justify injustice, in the name of religion.

Unite against the infidel and convert or eliminate him, in the name of religion.

The gods are on your side and you can control the uncontrollable if your belief is strong.

To be fair, much that is good and honourable has been accomplished in the name of religion – such as orphanages and hospitals and schools…

But much that is evil has also manifested and justified itself in the name of religion – such as crusades, religious persecution, racism, sexism…

Religion is not famous for possessing a “live and let live” attitude.

My wife is religious, in her own way, and remains devoted to her Catholicism by tradition, but she has sought her own path to peace and enlightenment by exploring such methods as meditation.

She is far more of a social animal than I, so she will, on occasion, participate in worship should one of our more religious friends ask this of her.

I am not so compliant or gregarious, but, for moments like christenings, weddings and funerals, I will throw on a suit and participate in all the pomp and ceremony with which religion surrounds itself to show my compassion for others to whom these moments matter.

I share their joys and sorrows, even if I don`t share their beliefs.

I try not to be hypocritical about it, so I won´t try to visit Mecca in the guise of a Muslim, or take communion in the pretense of a Christian, but I will remove my hat in a church and cover my head in a synagogue.

I may sing psalms I do not feel, but I don´t expect the enlightenment the congregation expects should I bow my head while others pray.

I love and respect my friends and family with their various Christian, Muslim and Hindu beliefs, even if I neither understand nor share their beliefs.

I respect my wife`s Catholic church and its long history and its emotionally moving rituals, but, similar to Groucho Marx, I refuse to join any church that would consider me as a member!

So why have I – who could be at best be labelled an agnostic and at worst a godless, without redemption, hopeless, barbaric, atheistic, infidel pagan – found myself over the years visiting temples, churches, shrines, monasteries and abbeys?

Could it be that I too, despite all my protestations, have a Homeric need for God?

I am not sure.

I feel closer to the divine when I am in a forest than when I am in a church, by an ocean rather than an altar, reading the clouds rather than reading holy writ.

But I am attracted to what religion represents – the good within man and man’s search for that good.

Granted that I, being the pagan I am, have limited authority to discuss such matters, for only the truly devout fully comprehend the shrines of the holy, but in spite of my limitations I have been profoundly affected by the places I will describe.

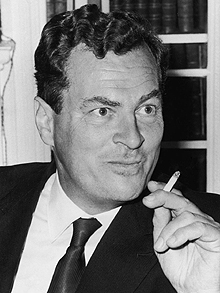

One of my favourite writers, Patrick Leigh Fermor, famous for his walking from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (vividly described in his books, A Time of Gifts, Between the Woods and the Water, and The Broken Road), was a man who lived life to its fullest.

After Constantinople, Fermor enlisted in the Irish Guards, fought in Greece and Crete. disguised as a shepherd organised the Resistance, and travelled extensively throughout his life.

So, at first glance, Fermor spending time in abbeys amongst the rigourous lives of monks in a retreat of peaceful solitude and calm contemplation, might seem odd.

Nonetheless his novella, A Time to Keep Silence, which recounts his experiences in the French abbey of St. Wandrille to the abandoned monasteries of Cappadocia in Turkey, resonates within me, for the emotions he expresses are akin to my own.

Like Fermor, I have visited more monasteries than are described because many of them were part of wider travels, wherein, though significant, were only accidentally a background part of the journey complete rather than deliberate goals sought out.

At first, monasteries and abbeys were of interest only for the purposes of charity, i.e. what food or shelter they could provide me.

As described in Canada Slim behind bars 5a: Arrested development, in my travels I learned how to travel without money by using charity to fill my empty stomach and shelter my weary head.

In travels across Canada, the US and Europe, many a night found me dossing in a Salvation Army type men’s hostel if an urban area was quite large.

Smaller towns would either offer me paid accommodation in a hotel or bed-and-breakfast, or would have me sleep directly inside the church itself.

I was rarely refused something to eat along with the night’s lodging.

So in this manner I was able to walk/thumb my way across Canada and hitch around the States and visit England and Wales and continental Europe when lack of finances was a problem.

I worked whenever possible and paid as often as I could, but I knew that had I waited to travel until I had complete financial security I might never have left.

I never begged on the street nor rummaged through rubbish and only stole the occasional hanging fruit off of trees.

I asked for help and was rarely refused.

I was a temporary burden at best.

Though I have known many a church, abbeys and monasteries somehow mostly escaped my notice.

(For Titchfield, see The glory departed of this blog.)

Only after meeting and marrying my wife Ute did abbeys and monasteries become deliberate goals of sites to see, rather than merely resources of food and shelter, especially in our journeys over the years in Italy.

The abbey that has left a most enduring impression, for it was the first abbey I spent time in really trying to understand the monastic life, was New Norcia, a place I have been recently reminded of when last month, on 24 August, a magnitude 6.2 earthquake struck near Norcia (the inspiration for New Norcia), Italy.

(See Moving Heaven and Earth of this blog.)

New Norcia is a town in Western Australia, 132 km/82 mi north of Perth, the only monastic town in Australia, and it is its story, and my own, I want to share.

Adam in the Abbey 2 will speak of Benedict and how he has inspired generations of followers.

Adam in the Abbey 3 will tell the tale of how two Spanish monks came to live in extreme hardship among the indigenous people of Australia and yet preserved to become a holy beacon in the South Pacific.

(To be continued…)