Landschlacht, Switzerland, 8 December 2016

Oh, what a lucky man I am!

As much as I complain at times about teaching there are also great moments that I also must share…

As regular readers of the gobbledygook I produce know, I have… along with Cambridge Certificate courses, business and technical English courses… conversation courses.

In one of the two conversation courses I teach, I ask my students to read literature and be prepared to speak about what they have read.

A number of weeks ago one of the ladies in this course told me she liked that I was introducing them to English language literary classics that they had not known existed.

I have exposed them to Ethan Frome and Tess of the d´Urbervilles, The Call of the Wild and Gulliver´s Travels, Madame Bovary and The Accidental Tourist…to name just a few.

And I have found an unexpected benefit to this activity…

I am discovering (or rediscovering) these literary works for myself.

Let us light a candle on 17 March in memory of a man whose humble efforts would end up transforming English literature and would also ignite the spark of women´s equality in England and throughout the English-speaking world.

Above: The life of Victorian women, 1840

Patrick Prunty was born in Loughbrickland, County Down, Ireland, on 17 March 1777 to a family of farm workers of modest means.

Above: Patrick Bronte, neé Prunty, 1860

Patrick´s mother was Roman Catholic and his father was a Protestant.

Patrick was brought up in his father´s faith.

Patrick was a bright young man and won a scholarship to Cambridge, where he studied divinity and history.

Above: St. John´s College, Cambridge, England, where Patrick studied

It is not quite known why Patrick decided to change his surname.

Perhaps he found his surname was too Irish.

Perhaps he wanted to distance himself from his brother, a fugitive for his involvement with the United Irishmen against the British occupation of Ireland.

Perhaps Patrick´s new surname choice was a sign of admiration for Horatio Nelson, the Duke of Bronte.

Above: Horatio Nelson (1758 – 1805)

On 10 August 1806 Patrick Bronte was ordained a priest of the Church of England, eventually becoming curate of the parish of Haworth in Yorkshire by 1820.

Above: Haworth Parsonage, 1861

Above: Bronte Parsonage Musuem

The village of Haworth did not have a sewage system and the water was contaminated by faeces and decomposing bodies from the nearby cemetery.

Food for most was scarce and deficient in vitamins.

Public hygiene was non-existent and lavoratories basic.

Patrick was also a poet, writer and polemicist, but his writing never took the world by storm, and he never became a great financial success as a curate either.

Patrick was also a husband and a father and it was to be his fate to survive, to outlive his entire family.

His daughters would create literature that would inspire millions of readers for centuries to come and would change the perception and the prospects of women forever.

Patrick met and married 29 year old Maria Branwell of Penzance in 1812.

Above: Maria Branwell Bronte

Maria came from a comfortable well-to-do family who owned a flourishing tea and grocery store.

(I am reminded of my own mother when I consider the life of Maria.)

Maria was a literate and pious woman, known for her lively spirit, joyfulness and tenderness, a very vivacious woman.

(Genevieve (Jenny) Kerr, neé Budd, would have found a kindred spirit in Maria had they had lived in the same parish at the same time.

My mother was also quite intelligent, lively, joyful, tender and vibrant.)

Maria (like my mother) died from uterine cancer, a particularly painful manner of suffering.

Maria died in 1821 having produced six children.

Maria, the eldest child, was born in 1814; Elizabeth was born in 1815; Charlotte in 1816; Patrick in 1817; Emily in 1818 and Anne in 1820.

(My mother would also produce six children: Thomas in 1952, Valerie in 1954, Christopher in 1955, Cynthia in 1956, Kenneth in 1960 and your humble blogger in 1965.

Jenny died when I was four.)

Elizabeth Branwell, Maria´s older sister, arrived in 1821 after Maria´s death and remained to help Patrick with his children until her death in 1842.

Curate Patrick faced a troublesome challenge in arranging for the education of his children as his income was barely above poverty standards.

The Brontes had no significant connections to assist them and Patrick could not afford the fees needed for his children to attend well-established schools.

His only alternative was charity schools.

He was aware that some schools were better than others and that the truly horrid existed.

Patrick read the Leeds Intelligencer of 6 November 1823 which reported on two Yorkshire towns where pupils were found gnawed by rats and suffering from malnutrition so extreme that some of them had lost their sight.

But there had been no indication that the Reverend Carus Wilson´s Clergy Daughters School at Cowan Bridge would not provide a good education and take good care of his daughters.

In 1824 the four eldest girls entered Cowan Bridge School.

In 1825 Maria and Elizabeth fell gravely ill and were removed from the School.

Maria had suffered hunger, cold and privation.

Charlotte described Maria as being very lively, very sensitive and very advanced in her reading.

Maria returned from Cowan Bridge with an advanced case of tuberculosis and died at the age of 11 on 6 May 1825.

Elizabeth, less vivacious and less advanced, suffered the same fate.

Elizabeth died, age 10, on 15 June 1825.

Charlotte and Emily were also withdrawn from the School.

The loss of her older sisters was a trauma that would be shown in Charlotte´s writing.

Charlotte blamed Cowan Bridge for her sisters´ deaths, citing the School´s poor medical care, the scanty and spoiled food, the lack of food and adequate clothing, the prevalence of typhus, the severe and arbitrary punishments and the harshness of its teachers.

In Jane Eyre, Cowan Bridge became Lowood, Maria the young Helen Burns, the cruel mistress Miss Andrews became Miss Scatherd and the tyrannical headmaster the Reverend Carus Wilson became Mr. Brocklehurst.

Above: Poster for Jane Eyre film (2011)

The three surviving sisters and their brother Branwell were very close and during childhood developed their imaginations, first through oral storytelling and roleplaying in an intricate imaginary world they had created and later through collaborative writing of complex stories.

The children became interested in writing from an early age, which started as a game grew into a passion.

At the centre of the children´s creativity were twelve wooden soldiers which Patrick had given to Branwell in 1826.

These 12 soldiers fired the children´s imagination.

Dubbing the soldiers the Young Men and giving each soldier a name the children would lead them to the imaginary kingdom of Glass Town, the Empire of Angria and the North Pacific island continent of Gondal.

Above: Manuscript of Emily Bronte´s Gondal Poems

Their stories were written in “little books”, the size of a matchbox and bound with thread.

The pages were filled with close minute writing, in block letters without punctuation and richly embellished with illustrations, detailed maps, schemes, landscapes and building plans.

The books were made small so that the soldiers could read them.

What happened to the family Bronte after Cowan Bridge and how the three sisters would develop separately and together is the subject of the blogs that will follow.

Curate Patrick, an open, intelligent and generous man, bought all the books and toys the children asked for and accorded them great freedom and unconditional love.

Elizabeth Branwell taught the children arithmetic and the alphabet and gave them books and magazines and was also extremely dedicated and generously devoted her life to her nieces and nephew.

Due to the Brontes´ isolation, they would constitute by themselves their own separate literary group.

Their stories would become famous for their originality and passion.

Their fictional worlds were the product of their fertile imagination fed by reading, discussion and their love of literature.

Patrick would live until 1861 and die at the age of 84, but his four remaining children would die in 1848, 1849 and 1855 at ages 29, 30, 31 and 39.

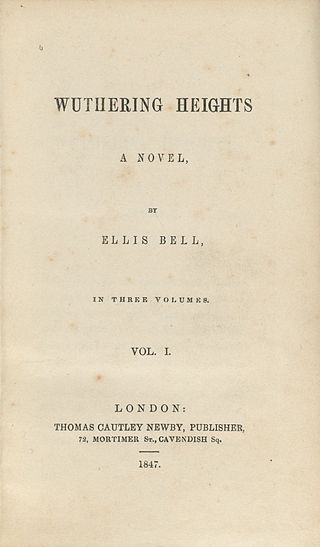

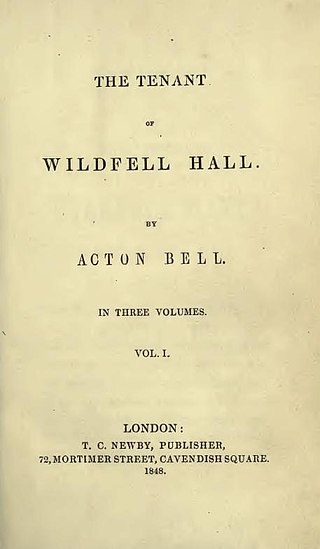

Charlotte would be best known for Jane Eyre, Emily for Wuthering Heights and Anne for The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

(Though they would be published under invented male names…)

Branwell would succumb to alcoholism.

Above: Patrick Branwell Bronte, self-portrait, 1840

All of Patrick´s children would deny him grandchildren and only Charlotte would marry, though dying one year later.

I cannot imagine how painful it must have been for Patrick to outlive his wife, his sister-in-law, his five daughters and his son.

But the legacy this son of farmers, this mere curate, would leave behind makes him worthy of remembrance.

Let us light a candle for Patrick.

Above: Anne, Emily and Charlotte Bronte, painted by Branwell Bronte (1834)

Sources: Wikipedia