Landschlacht, Switzerland, 4 January 2017

Outside my window, upon the streets of this wee hamlet, the snow remains.

Beneath the snow nature sleeps, awaiting the resurrection of spring.

Yet life continues nonetheless…

Cows and sheep graze beneath the snow for succulent grass.

Birds continue their happy carefree melodies.

Humans scurry and hurry about, seeking sustenance and comfort in a world so cold, earning their daily bread as best they can, hoping that in the continuance of life, a reason for living might be found.

Granada, Spain, 2 January 1492

“They are yours, O King, since Allah decrees it.”

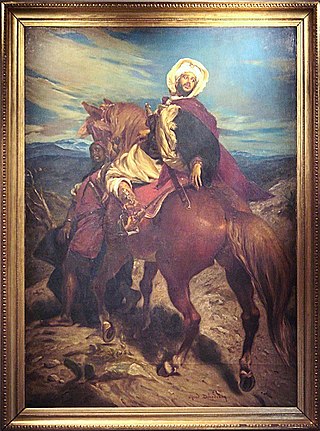

Above: Emir Muhammad XII (aka Boabdil)(1460 – 1533)

With these words Boabdil, ruler of Granada, handed the keys to the city to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castille, after a virtually bloodless siege that had lasted nine months.

The last Moorish stronghold in Spain surrendered to the might of the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella.

The Moors, who had arrived in Spain in 711, were finally defeated.

The gates of Grenada were thrown open and Ferdinand entered, bearing the great silver cross he had carried throughout his liberation of Spain from Moorish rule.

Boabdil rode out through the gates of Grenada with his entourage, never to return.

Reaching a lofty spur of the Alpujarras, he stopped to gaze back at the fabulous city he had lost.

As he turned to his mother who rode at his side, a tear escaped him.

But instead of the sympathy he expected, his mother addressed him with contempt:

“You do well to weep like a woman for what you could not defend like a man.”

The rocky ridge from which Boabdil had his lost look at Grenada has henceforth been called El Ultimo Suspiro del Moro – the Last Sigh of the Moor.

Vatican City, Papal States, 3 January 1521

Giovanni di Lorenzo de Medici is tired of these doubting upstarts, especially one particular German priest.

He, his Holiness Pope Leo X, had directed the Vicar General of the Augustine Order to impose silence upon his monks.

Above: Pope Leo X (1475 – 1521)

Yet Martin Luther would not cease his prattling.

Above: Martin Luther (1483 – 1546)

Then this troublesome German priest has the effrontery to contact his Holiness directly trying to educate the Church on how this institution established by the Son of God Himself was in error in its ways.

Luther is summoned to Rome.

But does he obey?

No.

Instead the Church has to summon Cardinal Cajetan (1469 – 1534) to travel to Augsburg and meet with this upstart monk.

Above: Cardinal Cajetan (on the left in red, standing before the book), Martin Luther (on the right), October 1518

A papal Bull is sent requiring all Christians to believe in the Pope´s power to grant indulgences.

Does Luther retract his 95 Theses?

No.

A year, an entire year, of endless fruitless negotiations with this stubborn German, but in typical German stubbornness and conviction of his being right regardless of risk or reasons against it, Luther will not budge.

His Holiness sends yet another Bull, condemning at least 41 propositions of Luther´s teachings.

Above: The Exsurge Domine (1521), from Pope Leo X

Luther publicly burns the damned thing.

Enough.

This German is an unpleasant taste in the mouth of the Church and thus let him be cast out.

Emperor Charles V has been directed to take energetic measures against heresy.

Above: Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1519 – 1556)

The Church needs money.

The Church needs foreign aid.

It cannot be distracted nor dissuaded from its causes just and holy and ordained by God through his holy representative the Pope.

Christ must be glorified and His temporal power extended.

Let St. Peter´s and Rome demonstrate the glory of God.

Let Ferrara, Parma and Piacenza take their rightful place within these Papal States.

Let us enjoy the Papacy since God has given it to us.

Indulgences are the will of God and let no one challenge the will of God.

Let Luther be excommunicated.

Above: The Decet Romanum Pontificem, the Papal Bull of Pope Leo X, excommunicating Martin Luther from the Catholic Church

Berkeley, California, USA, 29 December 2016

Huston Smith is dead.

Above: Huston Smith (1919 – 2016)

Huston, a renowned scholar of religion who pursued his own enlightenment wherever he could, died at home, age 97.

Professor Smith was best known for The Religions of Man, (later retitled The World´s Religions) a standard textbook in college comparative religion classes, which examines the world´s major faiths as well as those of indigenous peoples, observing that all express the indescribable Absolute…

“If, then, we are to be true to our own faith, we must attend to others when they speak, as deeply and as alertly as we hope they will attend to us.

If we take the world´s enduring religions at their best, we discover the distilled wisdom of the human race.”

Professor Smith had an interest in religion that transceded the academic.

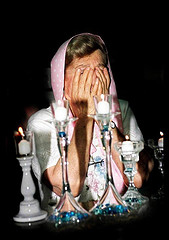

In his joyful pursuit of enlightenment – to “turn our flashes of insight into abiding light” – Smith meditated with Tibetan Buddhist monks, practiced yoga with Hindu holy men, whirled with ecstatic Sufi Islamic dervishes, chewed peyote with Mexican indigenous people and celebrated the Jewish Sabbath with a daughter who had converted to Judaism.

Above: Buddhist Boudhanath Stupa, Kathmandu, Nepal

Above: Hindu goddess Shiva performing yoga, Karnataka, India

Above: Whirling Dervishes, Rumi Fest 2007

Above: Peyote drummer (1927)

Above: Jewish Shabbat praying with Shabbat candles

Smith was born to Methodist missionaries on 31 May 1919 in Suzhou, China.

The family soon moved to the ancient walled city Zang Zok, a “cauldron of different faiths”.

Smith decided to be a missionary and his parents sent him to Central Methodist University in Lafayette, Missouri.

Smith was ordained a Methodist missionary but soon realised that he had no desire to “Christianise the world”.

Smith would rather teach than preach.

Professor Smith joined campaigns for civil rights in the 1960s and for a more tolerant understanding of Islam in the 2000s.

Despite his liberal views, Smith argues that science might not totally explain natural phenomena.

Smith clung to Methodism while criticizing its dogma.

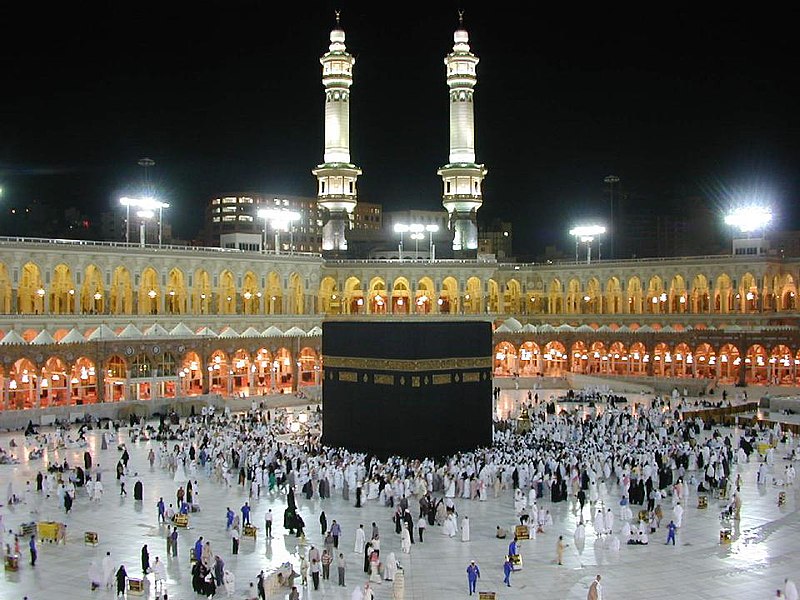

He prayed in Arabic to Mecca five times a day.

Above: The Kaaba in Mecca – the direction of prayer and the destination of pilgrimage for Muslims all over the world

His favourite prayer was written by a nine-year-old boy whose mother had found it scribbled on a piece of paper beside his bed.

“Dear God,

I´m doing the best I can.”

Above: Michelangelo´s The Creation of Adam, The Sistine Chapel, St. Peter´s Basilica, Vatican City (1512)

Sources: Wikipedia / Douglas Martin and Dennis Hevesi, The International New York Times, 3 January 2017