Landschlacht, Switzerland, 1 March 2017

There are moments when the well runs dry, the fire is out, the spirit extinguished.

Moments when I look at this blank screen and ask myself:

What should I write about?

Regular readers of my blog (both of them?!) patiently wait for some blog series to continue and/or conclude – That Which Survives (Brussels/Brontes), The sick man of Europe and the sons of Karbala (Turkish/Kurdish relations), The Underestimated (Switzerland) – but I seek to find opportunities when writing upon these themes seems appropo for the current time and events of the moment.

On a regular basis, I buy daily newspapers and weekly newsmagazines in the hopes that they will generate ideas of themes to discuss, but these media must somehow move me to react strongly to provoke words and thoughts out of me.

This morning I was uninspired.

Completely.

Though President Trump (two words I never thought I’d see together / two words that just seem wrong together) and his first speech to Congress yesterday seemed to be all anyone could talk about – what did he say? what did he not say? what did it all mean? – I honestly could not decide what I could say in this blog that hadn’t already been said by professionals more cleverer than I.

I had worked hard on my last blog post Bleeding Beautiful, trying to bring to the reader a semblance of connectiveness to the shooting of an Indian IT specialist in Kansas, a sense of place and time to the incident and a sensory sensitivity to help the reader relate his/her own life to the incident.

From left: Srinivas Kuchibhotia, who died; Alok Madasani, who was injured; Ian Grillot, also injured

So my mind felt it had to take a step back and meditate for a time before finding, yet again, the passion and the patience it takes to weave words into worthwhile reading.

Then a visit to Konstanz generated three sources of inspiration: We Are The Change We Seek: The Speeches of Barack Obama, a back-ordered copy of Huston Smith’s The World’s Religions, and the latest edition of Foreign Affairs.

Then I knew what I wanted to share with you, my gentle readers…

America has become afraid.

9/11 was a wake-up call…

![]()

Americans could be attacked, not only in fields foreign or upon exotic embassies or military machines, but in US streets, in US fields, fury visited from the skies and visited from within.

Not even the Second World War, with its millions of lives destroyed, had shown Americans attacked on the soil of the continental United States, if one does not include war with neighbours or amongst brothers.

But the images of passenger jets striking the Twin Towers was so shocking, so powerful, that even Presidents on tour could only sit stunned with disbelief, trying to grasp the surrealness of such an unreal situation.

![]()

It has been established that credit has been taken by and blame leveled at al Qaeda, who killed 3,000 people on that day – innocent men, women and children from the US and other nations who had done nothing to harm anybody.

Above: Black standard of al Qaeda

al Qaeda chose to murder, claim credit for the bloodshed and state their determination to kill on a massive scale.

Negotiations cannot convince al Qaeda, or Boko Borom, or ISIS/ISIL/Daesh to lay down their arms.

Many Muslims protest against and publicly condemn the twisted fantasies of extremists who commit acts of terrorism.

Others say that these types are not true Muslims.

“Those people have nothing to do with Islam.” is the refrain.

And no one seems to see the irony that, of all the non-Western religions, Islam stands closest to the West, both geographically and ideologically.

Despite Christian, Jew and Muslim all descending from the family of Abraham religiously and Greek thought philosophically, Islam remains the most difficult religion for the West to understand.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 2 March 2017

“No part of the world is more hopelessly and systematically and stubbornly misunderstood by us than that complex of religion, culture and geography known as Islam.”

(Meg Greenfield, Newsweek, 26 March 1979)

Proximity is no guarantee of concord, of harmony.

More homicides occur within families than anywhere else.

Common borders have given rise to border disputes.

Raids lead to counterraids and escalate into vendettas, blood feuds and war.

There have been times and places Christians, Muslims and Jews have all lived together harmoniously, but for a good part of the last fifteen hundred years, Islam and the West have been at war.

People seldom have, and often do not want, a fair picture of their enemies.

It is easier to misunderstand while remaining faithful to our deepest values, but we need to discover through dialogue, observation and thought that there doesn’t have to be conflict between Islam and the rest of the world.

“As a student of history, I know civilisation’s debt to Islam.

It was Islam that carried the light of learning through so many centuries, paving the way for Europe’s Renaissance and Enlightenment.

It was innovation in Muslim communities that developed the order of algebra, our magnetic compass and tools of navigation, our mastery of pens and printing, our understanding of how disease spreads and how it can be healed.

Islamic culture has given us majestic arches and soaring spires, timeless poetry and cherished music, elegant calligraphy and places of peaceful contemplation.

Throughout history, Islam has demonstrated, through words and deeds, the possibilities of religious tolerance and racial equality.

Islam has always been a part of America’s story.

The first nation to recognise the United States was Morocco.

Above: The flag of Morocco

In signing the Treaty of Tripoli in 1796, President John Adams wrote:

Above: John Adams (1735 – 1826)(2nd US President: 1735 – 1826)

“The United States has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Muslims.”

And since America was founded, Muslims have enriched the United States…

…partnership between America and Islam must be based on what Islam is, not what it isn’t.”

Barack Obama (born 1961)(44th US President: 2009 – 2017)

(Barack Obama, “A New Beginning”, Cairo, Egypt, 4 June 2009)

“Although I loathe what terrorists do, I realise that, according to the minimal entry requirements for Islam, they are Muslims.

Islam demands only that a believer affirm that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad is his messenger.

Violent jihadists certainly believe this.

That is why major religious institutions in the Islamic world have rightly refused to label them as non-Muslims, even while condemning their actions…

…Even if their readings of Islamic Scripture seem warped and out of date, they have gained traction…

…As the extremists’ ideas have spread, the circle of Muslims clinging to other conceptions of Islam has begun to shrink.

And as it has shrunk, it has become quieter and quieter, until only the extremists seem to speak and act in the name of Islam.”

Above: United Arab Emirates Ambassador to Russia Omar Saif Ghobash (born 1971, Ambassador since 2009)(on the left) with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev (on the right)

(Omar Saif Ghobash, “Advice for Young Muslims”, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017)

“The very name of Islam means “the peace that comes when one’s life is surrendered to God”.

This makes Islam – together with Buddhism, from budh (awakening) – one of the two religions that is named after the attribute it seeks to cultivate.

In Islam’s case, life’s total surrender to God.

Successfully surrendering one’s life to God requires an understanding of what it is God wants.

Until the 20th century, Islam was called Muhammadism by the West, which to Muslims is not only inaccurate but offensive.

It is inaccurate, Muslims say, because Muhammad didn’t create Islam.

God did.

Muhammad was merely God’s mouthpiece.

The title of Muhammadism is offensive, because it conveys the impression that Islam focuses on a man rather than on God.

To name Christianity after Christ is appropriate, for Christians believe that Christ was/is God.

To call Islam Muhammadism is like calling Christianity St. Paulism.

Islam begins not with Muhammad in 6th century Arabia, but with God.

In the beginning God…

Islam calls God Allah by joining the definite article al (the) with Ilah (God)- literally Allah means the God, not a god, for there is only one.

The blend of admiration, respect and affection that Muslims feel for Muhammad is impressive.

They see him as a man who experienced life in exceptional range – shepherd, merchant, hermit, exile, soldier, lawmaker, prophet, priest, king, mystic, husband, father, widower – but they never mistake Muhammad for the earthly centre of their faith.

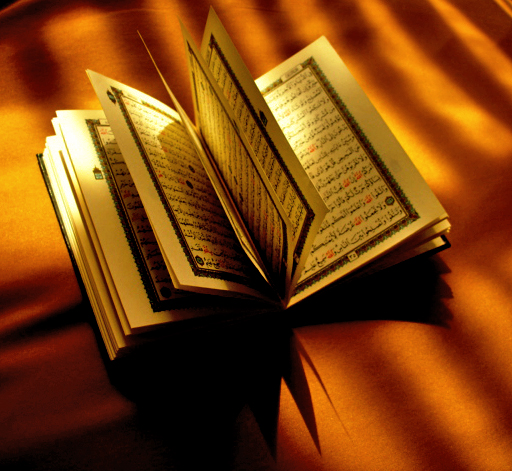

That place is reserved for the scripture of Islam, the Koran.

The word al-qur’an in Arabic means the recitation.

As discomfitting as it is for Christians to contemplate, the Koran is perhaps the most recited, the most read, book in the world.

The Koran is the world’s most memorised book and possibly the book that exerts the most influence on those who read it.

Muslims tend to read the Koran literally.

In almost exactly the way Christians consider Jesus to have been the human incarnation of God, Muslims consider the Koran to be the human recitation of God.

If Christ is God incarnate, the Koran is God inlibriate.”

Above: Huston Smith (1919 – 2016)

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

In my personal library here in Landschlacht I have a number of books on the topic of religion, including the scriptures of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

I have different versions of the Christian Bible and I also possess books that examine morality from secular and atheistic points of view.

But I am neither a practioner of, nor scholar of, religion.

Rather I seek to understand the power of religion upon so many people on this planet, in a humble quest to seek out a kernel of commonality and truth that might, in time, unite us in ways the conflict of faiths cannot.

The Koran, even in English translation, is not an easy read.

It is not the kind of book one can read in bed on a rainy day.

Nothing but a sense of duty could carry an agnostic Canadian through the Koran.

“The European will peruse with impatience its endless incoherant rhapsody of fable and precept and declamation, which seldom excites a sentiment or an idea, which sometimes crawls in the dust and is sometimes lost in the clouds.”

Above: Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794)

(Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

“The language in which the Koran was proclaimed, Arabic, is the key.

Muhammed asked his people:

“Do you ask for a greater miracle than this, O unbelieving people, than to have your language chosen as the language of that incomparable Book, one piece of which puts all your golden poetry to shame?” “

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

“No people in the world are so moved by the word, spoken or written, as the Arabs.

Hardly any language seems capable of exercising over the minds of its users such irresistable influence as Arabic.”

(Philip Hitti, The Arabs: A Short History)

“Crowds in Cairo, Damascus or Baghdad can be stirred to the highest emotional pitch by statements that, when translated, seem lifeless and banal.

The rhythm, the melody, the rhyme of Arabic produces a powerful hypnotic effect.

The power of the Koran lies not only in the literal meaning of its words, but in the sound of the language in which it is recited.

Translation cannot convey the emotion, the fervor, the mystery that the Koran holds in its original Arabic.

This is why, in sharp contrast to Christians, who have translated their Bible into every script known to man, Muslims prefer to teach others the language in which they believe Allah spoke finally with incomparable force and directness.

The language of Islam remains a matter of sharp controversy.

Orthodox Muslims feel that the ritual use of the Koran must be in Arabic, but there are many who believe that those who do not know Arabic should read the Koran in translation.

Language is not the only barrier the Koran presents to outsiders, for its content is unlike other religious texts.

The Koran is not explicitly metaphysical like the Upanishads, not grounded in drama like the Hindu epics, nor historical narrative like Hebrew scriptures.

Unlike the Gospels of the New Testament or within the chapters of the Bhagavid-Gita, God is not revealed in human form within the Koran.

The overwhelming message of the Koran is to proclaim the unity, omnipotence, omniscience and mercy of God and the total dependence of human life upon God.

The Koran is essentially naked doctrine – doctrine stripped of chronological order, doctrine stripped of epic character or drama, doctrine stripped of commentary and allusion.

In the Koran God speaks in the first person, describing Himself and making known His laws, directly to mankind through the words and the sounds of this holy book.”

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

“The Qur’an does not document what it is other than itself.

It is not about the truth.

It is the truth.”

(Kenneth Cragg, Readings in the Qur’an)

“Islam does not apologise for itself, try to explain itself or attempt to seduce others into its fold by altering its form.

And for the non-Islamic outsider, it is this nonconformity, this inflexibility, that makes compassion and comprehension of Islam so very difficult.

Certainly it seems that the message of the Koran proclaiming the unity, omnipotence, omniscience and glory of Allah is uncompromising, but outsiders miss and misinterpret that Islam is more than the recognition of the majesty of Allah, Islam is the mercy of Allah manifested as Peace.

The Koran, 4/5 of the length of the New Testament, divided into 114 chapters (surahs), cites Allah’s compassion and mercy 192 times and Allah’s wrath and vengence only 17 times.

Is this Koranic description of Allah as “the Holy, the Peaceful, the Faithful, the Guardian over His servants, the Shelterer of the orphan, the Guide of the erring, the Deliverer from every affliction, the Friend of the bereaved, the Consoler of the afflicted” anything else but loving?

“In His hand is good, and He is the generous Lord, the Gracious, the Hearer, the Near-at-Hand, the Compassionate, the Merciful, the Very-forgiving, whose love for man is more tender than that of the mother bird for her young.” “

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

Is this the Allah of jihadists?

“We need to speak out, but it is not enough to declare in public that Islam is not violent or radical or angry, that Islam is a religion of peace.

We need to take responsibility for the Islam of peace.

We need to demonstrate how it is expressed in our lives and the lives of those in our community.”

(Omar Saif Ghobash, “Advice for Young Muslims”, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017)

“The use of force is one aspect of Islam that is often misunderstood and maligned by non-Muslims.

The Koran does not counsel turning the other cheek or pacifism.

It teaches forgiveness and the return of good for evil when the circumstances warrant it.

Muhammad left many traditions regarding the decent conduct of war.

Agreements are to be honoured and treachery avoided.

The wounded are not to be mutilated, nor the dead disfigured.

Women, children and the old are to be spared, as are orchards, crops and sacred objects.

The important question is the definition of a righteous war.

According to the Koran, a righteous war must either be defensive or to right a wrong.

The agressive and unrelenting hostility of Islam’s enemies forced Muhammad to seize the sword in self-defence, or, together with his entire community and his faith, be wiped from the face of the Earth.

That other religious teachers succumbed under force and became martyrs was to Muhammad no reason that he should do the same.

Having seized the sword in self-defence Muhammad held onto it to the end.

This much Muslims acknowledge.

Above: The Umayyad Empire at its greatest extent

But Muslims insist that while Islam has at times spread by the sword, Islam has mostly spread by persuasion and example.

“Let there be no compulsion in religion.” (Koran, al-Baqarah 256)

“To everyone have we given a law and a way.

And if God had pleased, he would have made all mankind one people of one religion.

But He has done otherwise, that He might try you in that which He has severally given to you.

Therefore press forward in good works.

Unto God shall you return and He will tell you that concerning which you disagree.” (Koran, al-Ma’ida 48)

“Will you then force men to believe when belief can come only from God?” (Muhammed quoted by Ameer Ali, The Spirit of Islam)

How well Muslims have lived up to Muhammad’s principles of toleration is a question of history that is far too complex to admit of a simple, objective and definitive answer.

Objective historians are of one mind in their verdict that, to put the matter minimally, Islam’s record on the use of force is no darker than that of Christianity.

Every religion at some stages in its career has been used by its professed adherents to mask aggression.

Islam is no exception.

Muslims deny that Islam’s record of intolerance and agression is greater than that of the other major religions.

Muslims deny that Western histories are fair to Islam in their accounts of its use of force.

Muslims deny that the blots in their record should be charged against their religion whose presiding ideal Muslims affirm in their standard greeting:

As-salamu ‘alaykum. (Peace be upon you)”

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 1 March 2017

“Two attacks on Jewish cemeteries in St. Louis and Philadelphia last week have resulted in an outpouring of more than $136,000 in donations from thousands of Muslims and others, who have pledged to financially support Jewish institutions if there are further attacks.

Jewish organisations have reported a sharp increase in harassment.

The Jewish Community Center Association of North America, which represents Jewish community centres, said 21 Jewish institutions, including eight schools, had received bomb threats on Monday alone.

Two Muslim activists, Linday Sarsour and Tarek El-Messidi, asked Muslims to donate $20,000 in a crowdfunding effort to repair hundreds of Jewish headstones that were toppled nead St. Louis last week.

That goal was reached in three hours.

El-Messidi said on Monday that the money raised would most likely be enough to repair the graves near St. Louis and in Philadelphia, where about 100 headstones were toppled on Sunday.

Any extra money will be held in a fund to help after attacks on Jewish institutions in the future, which could mean removing a spray-painted swastika or repairing the widespread damage seen in the graveyards.

About 1/3 of the donations have come from non-Muslims, but El-Messidi said it was especially important for Muslims to support Jews as they deal with anti-Semitic attacks.

“I hope our Muslim community, just as we did last week with St. Louis, will continue to stand with our Jewish cousins to fight this type of hatred and bigotry.”, El-Messidi said.

Barbara Perle, 66, of Los Angeles said on Monday that several of her family members were buried in the vandalised Chesel Shel Emeth Cemetery near St. Louis.

In her eyes, an attack on one gravestone in a Jewish cemetery was an attack on them all.

Perle said she had reached out to thank El-Messidi and that she had “come to understand more about our shared humanity.” “

(Daniel Victor, “Muslims pledge aid to Jewish institutions“, New York Times, 1 March 2017)

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 3 March 2017

“I am not saying that Muslims should accept blame for what terrorists do.

I am saying that we can take responsibility by demanding a different understanding of Islam.

We can make clear to Muslims and non-Muslims, that another reading of Islam is possible and necessary.

We need to act in ways that make clear how we understand Islam and its operation in our lives.

I believe we owe that to all the innocent people, both Muslim and non-Muslim, who have suffered at the hands of our coreligionists in their misguided extremism.

Taking that sort of responsibility is hard, especially when many people outside the Muslim world have become committed Islamophobes, fearing and hating Muslims, sometimes with the encouragement of political leaders.

When you feel unjustly singled out and attacked, it is not easy to look at your beliefs and think them through.”

(Omar Saif Ghobash, “Advice for Young Muslims”, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017)

“For Muslims, life has basically two obligations.

The first is gratitude for the life that has been received.

The Arabic word “infidel” is closer in meaning towards “one who lacks thankfulness” than one who disbelieves.

The more gratitude one feels, the more natural it feels to let the blessings of life to flow through one’s life and on to others, for hoard these blessings to only ourselves is as unnatural as trying to dam a waterfall.

The second obligation lies within the name of the religion itself.

“Islam” means “surrender”, not in the sense of miltiary defeat, but rather in the context of a wholehearted giving of oneself – to a cause, to friendship, to love.

Islam is, in other words, commitment.

The five pillars of this commitment to the straight path are:

- Confession of faith: The affirmation “There is no god but Allah and Muhammad is His Prophet.” said correctly, slowly, thoughtfully, aloud, with full understanding and with heartfelt conviction.

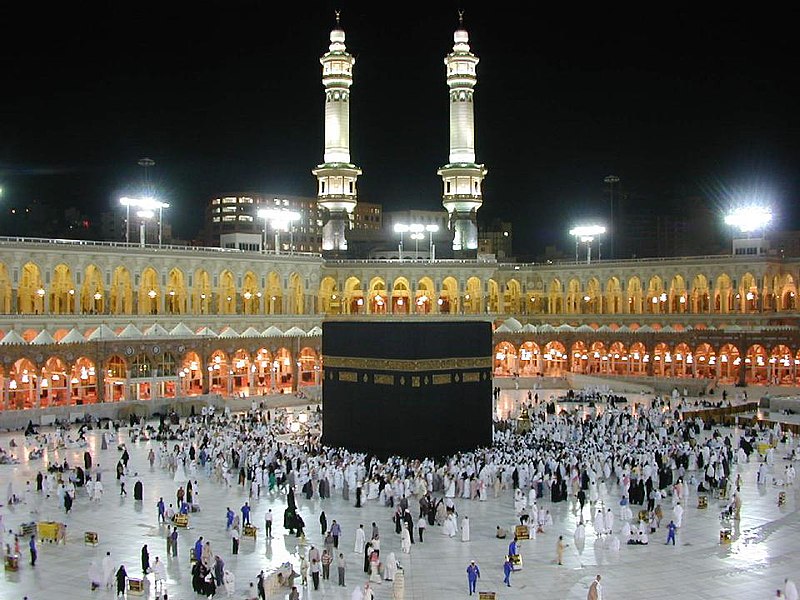

2. Constant prayer: To give thanks for life’s existence, to keep life in perspective, routinely done five times a day when possible, publicly when possible, kneeling and facing towards Mecca

3. Charity: Those who have much should help lift the burden of those who are less fortunate.

4. The observance of Ramadan, Islam’s holy month:

From the first moment of dawn to the setting of the sun, neither food nor drink nor smoke passes the Muslim’s lips.

After sundown, these may be consumed in moderation.

Why?

Fasting makes one think.

Fasting teaches self-discipline.

Fasting underscores one’s dependence on God, reminding one of a person’s fraility.

Fasting sensitizes compassion: Those who have fasted for 29 days tend to be more sympathetic to those who are hungry.

5. Pilgrimage: Once during his/her lifetime every Muslim who is physically and economically in a position to do so is expected to journey to Mecca.

The basic purpose of the pilgrimage is to heighten the pilgrim’s devotion to God.

The conditions of the pilgrimage are a reminder of human equality.

Upon reaching Mecca, pilgrims remove their normal attire, which carries marks of social status, and don two simple sheet-like garments.

Distinctions of rank and hierarchy are removed.

Prince and pauper stand before God in their undivided humanity.

A pilgrimage brings together people from various countries, demonstrating that they share a loyalty that transcends nations and ethnic groupings.

Pilgrims pick up information about other lands and peoples and return to their homes with better understanding of one another.”

(Huston Smith, The World’s Religions)

“You will inevitably come across Muslims who shake their heads at the state of affairs in the Islamic world and mutter:

“If only people were proper Muslims, then none of this would be happening.”

Some Muslims will say this when criticising official corruption in Muslim countries and when pointing out the alleged spread of immorality.

Some Muslims say this when promoting various forms of Islamic rule.

“Islam is the solution.”

It’s a brilliant slogan.

Lots of people believe in it.

The slogan is a shorthand for the argument that all the most glorious achievements in Islamic history – the conquests, the empires, the knowledge production, the wealth – occurred under some system of religious rule.

Therefore, if we want to revive this past glory in the modern era, we must reimpose such a system.

This argument holds that if a little Islam is good, then more Islam must be even better.

And if more Islam is better, then complete Islam must be best.

The most influential proponent of that position today is ISIS, with its unbridled enthusiasm for an all-encompassing religious caliphate.

![Black Standard[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/AQMI_Flag_asymmetric.svg/800px-AQMI_Flag_asymmetric.svg.png)

Above: Black standard of ISIS

It can be difficult to argue against that position without seeming to dispute the nature of Islam’s origins: the Prophet Muhammad was not only a religious leader but a political leader as well.

And this argument rests on the inexorable logic of extreme faith:

If Muslims declare that they are acting in Allah’s name, and if Muslims impose the laws of Islam, and if Muslims ensure the correct mental state of the Muslim population living in a chosen territory, then Allah will intervene to solve all our problems.

The genius of this argument is that any difficulties or failures can be attributed to the people’s lack of faith and piety.

Leaders need not fault themselves or their policies.

Citizens need not question their values or customs.

But piety will take us only so far.

Relying entirely on God to provide for us, to solve our problems, to feed and educate and clothe our children, is to take God for granted.

The only way we can improve the lot of the Muslim world is by doing what people elsewhere have done, and what Muslims in earlier eras did, in order to succeed:

Educate ourselves and work hard and engage with life’s difficult questions rather than retreat into religious obscurantism (intentional obscurity and vagueness).

Today, some Muslims demand that all Muslims accept only ideas that are Muslim in origin – namely, ideas that appear in the Koran, the early dictionaries of the Arabic language, the sayings of the Prophet, and the biographies of the Prophet and his Companions.

Meanwhile, Muslims must reject foreign ideas such as democracy, they maintain.

Confronted with more liberal views, which present discussion, debate and consensus building as ancient Islamic traditions, they contend that democracy is a sin against Allah’s power, against His will and against His sovereignty.

Some extremists are even willing to kill in defense of that position.

But do such people even know what democracy is?

Another “foreign” practice that causes a great deal of concern to Muslims is the mixing of the sexes.

Some Muslim-majority countries mandate the separation of the sexes in schools, universities and the workplace.

Authorities in these countries present such rules as being “truly Islamic” and argue that they solve the problem of illicit relationships outside marriage.

Perhaps that’s true.

But research and study of such issues – which is often forbidden – might show that no such effect exists.

And even if rigorous sex separation has some benefits, what are the costs?

Above: Aziz Osmanoglu, father of two daughters with Sehabat Kocabas, recently lost a decision in Strasbourg’s European Court of Human Rights over whether sending his daughters to a mixed gender swimming pool was a violation of Article 9 of the European Convention of Human Rights respecting religious practices.

(The court decided that in the interest of integration that his daughters were required to take swimming lessons in mixed gender groups, but they were permitted to wear burkinis (full body swimsuits).

Above: Islamic modest swimwear, known as a urqini or burkini

Basel Canton, the Islamic family’s residence, will fine parents CHF 1,400 should they not send their children to swimming pools for religious reasons.)

Could it be that rigorous sex separation leads to psychological confusion and turmoil for men and women alike?

Could it lead to an inability to understand members of the opposite sex when one is finally allowed to interact with thwm?

Governments in much of the Muslim world have no satisfactory answers to those questions, because they often don’t bother to ask.

Conservative readings of Islamic texts…the strict traditionalist view…presents women as fundamentally passive creatures whom men must protect from the ravages of the world.

That belief is sometimes self-fulfilling.

In many Muslim communities, men insist that women are unable to face the big, wild world, all the while depriving women of the basic rights and skills they would need in order to do so.

Other traditionalists base their position on women on a different argument:

If women were mobile and independent and working with men who were not family members, then they might develop illicit romantic or even sexual relationships.

Of course, that is a possibility.

But such relationships also develop when a woman lives in a home where she is given little love and self-respect.

The traditionalist position is based, ultimately, on a desire to control women.

But women do not need to be controlled.

They need to be trusted and respected.

Treating women as inferior is not a religious duty.

It is a practice of patriarchal societies.

Within the Islamic tradition, there are many models of how Muslim women can live and be true to their faith.

There is no hard-and-fast rule requiring women to wear the hijab (the traditional veil that covers the head and hair) or a burqa or a niqab which cover far more.

Islam calls on women to be modest in appearance, but veiling is actually a pre-Islamic tradition.

The limits placed on women in conservative Muslim societies (mandatory veiling, rules limiting their mobility, restrictions on work and education), have their roots not in Islamic doctrine but rather in men’s fear that they will not be able to control women – and their fear that women, if left uncontrolled, will overtake men by being more disciplined, more focused, more hard-working.

The Prophet spoke about the ummah – the Muslim community – but the concept of the ummah has allowed self-appointed religious authorites to speak in the name of all Muslims without ever asking the rest of Muslims what they think.

The idea of an ummah also makes it easier for extremists to depict Islam – and all of the world’s Muslims – as standing in opposition to the West, or to capitalism or to the cause de jour.

In that conception of the Muslim world, the individual’s voice comes second to the group’s voice.

(Omar Saif Ghobash, “Advice for Young Muslims”, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017)

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 4 March 2017

People have been trained over the years to put community ahead of individuality.

Dialogue and public debate about what it means to be an individual in the world would allow us to think more clearly about personal responsibility, ethical choices, and the respect and dignity that attaches to people rather than to families, tribes or sects.

Dialogue and public debate might lead us to stop insisting solely on our responsibilities to the group and start considering our responsibilities to ourselves and to others, whom we might come to see not as members of groups but rather as individuals regardless of our backgrounds.

We might begin to more deeply acknowledge the outrageous amount of people killed in the Muslim world in civil wars and in terrorist attacks carried out not by outsiders but by other Muslims.

We might memorialize these people not as a group but as individuals with names and faces and life stories – not to deify the dead but rather to recognize our responsibility to preserve their honour and dignity, and the honour and dignity of those who survive them.

The idea of the individual might help us improve how we discuss politics, economics and security.

If we start looking at ourselves as individuals first and foremost, perhaps we will build better societies.

Take hold of your fate and take hold of your life in the here and now, recognizing that there is no need to return to a glorious past in order to build a glorious future.

Our personal, individual interests might not align with those of the patriarch, the family, the tribe, the community or the state, but the embrace of each person’s individuality will lead to a rebalancing in the world in favour of more compassion, more understanding and more empathy.

If you accept the individual diversity of those inside your own faith, you are more likely to do the same for those of other faiths as well.

We can and should live in harmony with the diversity of humanity that exists outside of our faith, but we will struggle to do so until we truly embrace ourselves as individuals.

(Omar Saif Ghobash, “Advice for Young Muslims”, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017)

It is said that we fear what we do not understand.

To conquer fear, we must first try and understand that which we are afraid of.

Only then will peace be unto you.