Landschlacht, Switzerland, 12 March 2017

I like Facebook.

There I said it.

I like the variety of news items that appear, the exchange of ideas, the casual contact with friends and family close or far away, and I find Facebook gives me a forum to share my thoughts.

But a few days ago I began to notice a problem and I wrote about it in Facebook:

“Oh, Father Facebook, forgive me for I have sinned.

It has only been mere moments since I was online posting things that caught my eye and looking up from my phone screen I was embarrassed to realise that a morning went by without my noticing it.

I have become like those I once mocked and ridiculed for their electronic addiction.

I find myself spending too much time reading about life, instead of living life.

A to-do list goes undone.

Walking weather goes unused, literature unread, music unappreciated.

On Monday evening, Switzerland experienced a 4.5 on the Richter scale earthquake and I cannot honestly say whether it was felt here by the Lake of Constance and I was distracted by electronics, or whether there were no tremors this far north of its epicentre.

And this is just….sad.

So, Father Facebook, we need to re-evaluate our relationship.

I value what I have read and am always intrigued by the new items that keep appearing.

But you are creating bad habits in me by capturing my curiosity.

You show me life while I am neglecting my own.

So, Father Facebook, we need to spend less time with one another.

So, one hour a day, six days a week is my new belated New Year’s resolution.

There is life out beyond the flat screen.

I will report in on what I find.

In the name of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and the Ghost in the Machine.

Above: Steve Jobs (1955 – 2011)

Amen

Problematic Internet use, also called compulsive Internet use (CIU), Internet overuse, problematic computer use, pathological computer use, problematic Internet use (PIU) or Internet addiction disorder (IAD), all refer to excessive Internet use that interferes with daily life.

Above: The Internet Messenger, Buky Schwartz, Holon, Israel

IAD began as a joke.

Dr. Ivan Goldberg found the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to be overly complex and rigid, so as a combination hoax and parody he invented IAD, describing its symptoms: “important social or occupational activities that are given up or reduced because of Internet use”, “fantasies or dreams about the Internet” and “voluntary or involuntary typing movements of the fingers”.

Goldberg felt that to receive medical attention or support for every single human behaviour by giving each one a psychiatric name was ridiculous.

He felt that if every overdose behaviour can be labelled an addiction then this could lead us to have support groups for individuals that consistently cough or are addicted to books.

Goldberg took pathological gambling, as diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, as his model for the description of IAD.

To Goldberg’s surprise, IAD receives coverage in the press.

The possible future classification of IAD as a psychological disorder continues to be debated and researched in the psychiatric community.

Online habits, such as reading, playing computer games, or watching very large numbers of Internet videos, are troubling only to the extent that these activities interfere with normal life.

IAD is often divided into subtypes by activity, such as gaming, online social networking, blogging, emailing, Internet pornography, or Internet shopping.

Internet addiction is a subset of the broader category of technology addiction.

Mankind’s widespread obsession with technology goes back to radio in the 1930s and television in the 1960s, but this obsession has exploded in importance during the digital age.

Above: Bakelite radio, Bakelite Museum, Orchard Hill, England

A study published in the journal Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking has suggested that the prevalence of Internet addiction varies considerably among countries and is inversely related to quality of life.

(Cecilia Chang and Li Angel Yee-Lam, “Internet Addiction Prevalence and Quality of Real Life: A Meta-Analysis of 31 Nations Across Seven World Regions”, Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking, Issue 17, December 2014)

A conceptual model of IAD has been developed based on primary data collected from addiction researchers, psychologists and health care providers as well as older adolescents themselves.

(Moreno/Jelenchik/Christakis, “Problematic internet use among older adolescents: A conceptual framework”, Computers and Human Behaviour, Issue 29, 2013)

(Kim/Byrne, “Conceptualizing personal web usage in work contexts: A preliminary framework”, Computers and Human Behaviour, Issue 27, June 2011)

These studies have identified seven concepts that make up IAD: psychological risk factors, physical impairment, emotional impairment, social and functional impairment, risky Internet use, impulsive Internet use, and Internet use dependence.

It is not just the amount of time spent on the Internet that puts people at risk, but how the time is spent is also important.

There is a problem if you are unable to maintain a balance or control over your Internet use in relation to everyday life.

It is difficult to detect and diagnose someone with IAD as the Internet is a highly promoted tool.

Addiction to cyber sex, cyber relationships, Internet compulsions, information and research and computer gaming are often considered to be related to IAD, but this variety of rewarding and reinforcing stimuli online might not be addictions to the Internet itself but rather the Internet is the fuel to other addictions.

A 1999 study discovered that over half the people considered to be Internet dependent were new users of the Internet and are therefore more inclined to use the Internet regularly.

Non-dependent users had been using the Internet for more than a year, suggesting that overuse of the Internet could wear off over time.

(Yellowlees/Marks, “Problematic Internet use or Internet addiction?”, Computers in Human Behaviour, Issue 23, March 2005)

What creates in some these compulsive behaviours?

Accessibility: Because of the convenience of the Internet, users now have easy and intermediate access to gambling, gaming and shopping at any time of the day, without the hassles of everyday life, like travelling or queues.

Control: Internet users are in control of their own online activity. With the use of the latest technology, such as tablet computers and smartphones, users can go to the bathroom or another private place to engage with the Internet, without others knowing about it.

Excitement: Internet users often get an excited feeling of a rush or a buzz when they win an online auction, a video game or online gambling. This positive feedback can result in addictive behaviour. Some users use the Internet as a way of gaining this emotion.

The Centre for Online Addiction claims that IAD is a broad term that covers a wide variety of behaviours and impulse control problems, and categorises IAD into five specific subtypes:

- Cybersexual addiction: The compulsive use of adult websites for cybersex and cyberporn. Internet pornography use is increasingly common in Western cultures and the mental health community has witnessed a dramatic rise in problematic Internet pornography use. At present there is no widely accepted means of defining or assessing problematic Internet pornography use and the notion of Internet pornography addiction is still highly controversial.

- Cyber-relationship addiction: Overinvolvement in online relationships. A cyber-relationship addiction has been described as the addiction to social networking in all forms. Social networking, such as Facebook, and online dating services, along with many other communication platforms create a place to communicate with new people. Virtual online friends start to gain more communication and importance over time to the person becoming more important than real life family and friends. Some people are attracted to the silent, less visually stimulating, non-tactile quality of text relationships, especially those who are struggling to contain the overstimulation of past trauma. Text communication is a paradoxical blend of people being honest and close while simultaneously keeping their distance. People suffering with social anxiety or who have issues of shame and guilt may be drawn to text relationships because people cannot be seen. Text enables them to avoid the issue of physical appearance which they find distracting or irrelevant to the relationship. Without the distraction of in-person cues, they feel they can connect more directly to the mind and soul of the other person. Cyber-relationships can often be more intense than real life relationships, causing addiction to the relationship. With the ability to create whole new personas, people can often deceive the person they are communicating with. Everyone is looking for the perfect companion, but the perfect companion online is not always the perfect companion in real life. Although two people can commit to a cyber-relationship, while offline one of them could possibly not be the person they are claiming to be online. There are people who deliberately create fake personal profiles online with the intention of tricking an unsuspecting person into falling in love with them. These people are known as “catfish”. (The term “catfish” is derived from the title of a documentary film released in 2010, in which New York photographer Nev Schulman discovers the woman he had been continuing a cyber-relationship with had not been honest whilst describing herself.)

- Net compulsions: Obsessive online gambling, shopping or day-trading. According to David Hodgins, Professor of Psychology at the University of Calgary, online gambling is considered to be as serious as pathological gambling. The online gambler prefers to separate himself from interruptions and distractions. Online, the problem gambler can indulge in gambling without social influences swaying his decisions. Online stock trading, like online gambling, gives the participant an addictive rush. Traders have ownership towards when and how they trade stocks and distribute their money. There are no second parties, no bosses, no schedules, so the trader feels a sense of empowerment in his own little world outside reality.

Above: Logo of the University of Calgary

Above: Logo of the University of Calgary - Information overload: Compulsive web surfing or database searches

- Computer addiction: Obsessive computer game playing. Video game addiction is a problem around the world.

IAD is usually linked with existing health issues, most commonly depression, and effects the addict socially, psychologically and occupationally.

Above: Belgian singer Jonathan Vandenbroeck aka Milow, known for his hit single cover, Ayo Technology

Pathological use of the Internet can result in negative life consequences, such as job loss, marriage breakdown, financial debt and academic failure.

70% of Internet users in South Korea are reported to play online games, 18% of these are diagnosed as game addicts.

Above: The flag of South Korea

The majority of those afflicted with IAD suffer from interpersonal difficulties and stress, while those addicted to online games specifically hope to avoid reality.

A major reason why the Internet is so appealing is the lack of limits and the absence of accountability.

“There were lots of reasons why we pulled the plug on our electronic media…My children don’t use media. They inhabit media…as fish inhabit a pond. Gracefully and without consciousness or curiosity as to how they got there. They don’t remember a time before email, instant messaging or Google.

They download movies and TV shows and when I remind them piracy is a crime, they look at one another and laugh. These are children who shrug indifferently when they lose their iPods, with all 5,000 tunes plus video clips, feature films and TV shows….

(Who watches TV on a television anymore?)

…”There’s plenty more where that came from.”, their attitude says.

And the most infuriating thing of all?

They’re right.

The digital content that powers their world can never truly be destroyed.

…I had always been an enthusiastic user of information technology, but I was also beginning to have doubts about the power of media to improve our lives – let alone make them “easier”.

I had noticed that the more we seemed to communicate as individuals, the less we seemed to function together as a family.

And on a broader scale, the more facts we have at our fingerprints, the less we seem to know.

The “convenience” of messaging media (email, SMS, IM) consumes ever larger amounts of our time.

As a culture we are practically swimming in entertainment, yet remain more depressed than any people who have ever lived.

We began “The Experiment”, a six-month period during which we stopped using much of our electronic media, such as computers, televisions, game consoles and mobile phones.

Our family’s self-imposed exile from the Information Age changed our lives infinitely for the better.

I watched as my children became more focused, logical thinkers. I watched as their attention spans increased, allowing them to read for hours at a time. I watched as they began to hold longer and more complex conversations with adults and among themselves. I watched as they began to improve their capacity to think beyond the present moment.

They took the opportunity to go out more, to notice food more, to sleep more.”

(Susan Maushart, The Winter of Our Disconnect)

“And so it came to pass that in the winter of 2016 the world hit a tipping point…the moment when we realised that a critical mass of our lives and work had shifted away from the terrestrial world to a realm known as “cyberspace”… a critical mass of our interactions had moved to a realm “where we are all connected but no one is in charge.”

After all, there are no stoplights in cyberspace, no police officers walking the beat, no courts, no judges, no God who smites evil and rewards good…

If someone slimes you on Twitter or Facebook, well, unless it is a death threat, good luck getting it removed, especially if it is done anonymously, which in cyberspace is quite common.

Above: Company logo for Twitter

Yet this realm is where we now spend increasing hours of our day.

Cyberspace is now where we do more of our shopping, more of our dating, more of our friendship making and sustaining, more of our learning, more of our commerce, more of our teaching, more of our communicating, more of our news broadcasting and news seeking and more of our selling of goods, services and ideas.

It’s where both the US President and the leader of ISIS can communicate with equal ease with tens of millions of their respective followers through Twitter – without editors, fact checkers, libel lawyers or other filters.

![Black Standard[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/AQMI_Flag_asymmetric.svg/800px-AQMI_Flag_asymmetric.svg.png)

Even President Barack Obama was taken aback by the speed at which this tipping point tipped:

“I think that I underestimated the degree to which, in this new information age, it is possible for misinformation, for cyberhacking and so forth, to have an impact on our open societies.”, Obama told ABC News This Week.

Alan Cohen, chief commercial officer of the cybersecurity firm Illumio, noted in an interview on siliconAngle.com that the reason this tipping point tipped now was because so many companies, governments, universities, political parties and individuals have concentrated a critical mass of their data in computers.

Work has to start with every school teaching children digital civics, that the Internet is an open sewer of untreated, unfiltered information, where they need to bring skepticism and critical thinking to everything they read and basic civic decency to everything they write.

A Stanford Graduate School of Education study published in November 2016 found…

…”a dismaying inability by students to reason about information they see on the Internet.

Students had a hard time distinguishing advertisements from news articles or identifying where information came from.”

Professor Sam Wineburg, the lead author of the Stanford report, said:

“Many people assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally perceptive about what they find there.

Our work shows the opposite to be true.”

In an era when more and more of our lives have moved to this digital realm, that is downright scary.”

(Thomas Friedman, “Our lives are digital. Be careful.”, New York Times, 12 January 2017)

![]()

“Many men, women and children spend their days glued to their smartphones and their social media accounts.

No doubt you have seen the following scenarios many times:

- Young couples out to dinner pull out their smartphones to check messages, emails and social networks before scanning the menu and check their phones repeatedly during the meal.

- Shoppers and commuters standing in line, people crossing busy streets, even cyclists and drivers, have their eyes on their phones instead of their surroundings.

- Toddlers in strollers playing with a digital device instead of observing and learning from the world around them.

- People walking down the street with eyes on their phones, bumping into others, tripping over or crashing into obstacles.

Observations like these have prompted a New York psychotherapist to ask: “What really matters?” in life.

In her enlightening new book, The Power of Off, Nancy Colier observes that:

“We are spending far too much of our time doing things that don’t really matter to us.”

“We have become disconnected from what really matters, from what makes us feel nourished and grounded as human beings.”

The near universal access to digital technology, starting at ever younger ages, is transforming modern society in ways that can have negative effects on physical and mental health, neurological development and personal relationships, not to mention safety on our roads and sidewalks.

As with so much in life, moderation in our digital world should be the hallmark of a healthy relationship with technology.

Too many of us have become slaves to the devices that were supposed to free us and give us more time to experience life and the people we love.

Ms. Colier, a licensed clinical social worker, said:

“The only difference between digital addiction and other addictions is that this is a socially condoned behaviour.”

While Colier’s book contains a 30-day digital detox program, she offers three steps to help curb one’s digital dependence:

- Start by recognising how much digital use is really needed and what is merely a habit of responding, posting and self-distraction.

- Make little changes. Refrain from using your device while eating or spending time with your friends. Add one thing a day that is done without your phone.

- Become very conscious of what is important to you, what really nourishes you and devote more time and attention to it.

Linyi, Shandong Province, China, 17 January 2017

Above: The flag of the People’s Republic of China

Shandong Province is known for many things.

This stumpy peninsula jutting into the Yellow Sea, Shandong has a history that can be traced back to the origins of China itself.

Confucius, China’s great social philosopher, was born here and lived out his days here.

Above: Confucius (551 BC – 479 BC)

His ideas were championed by the great Confucian philosopher Mencius who also hailed from here.

Above: Mencius (372 BC – 289 BC)

Other local heroes include Wang Xizhi, China’s most famous calligrapher, and Zhuge Liang, a great military strategist.

Above: Wang Xizhi (265 – 420)

Above: Zhuge Liang (181 – 234)

Film star Gong Li, who set new benchmarks for Chinese beauty, grew up in this province.

Shandong has a firm foothold in China’s martial arts history: Wang Lang, the founder of Praying Mantis Fist – one of the most distinctive of the Chinese boxing arts, emulating the movements of the stick-like insect famed for its ferocity and speed – called Shandong home.

Shandong is home to one of China’s four major schools of cooking.

It is here that the Yellow River, the massive waterway that began in the mud of Tibet and exists as part of the myths that form this mighty land, exits China.

Above: Hukou Waterfall of the Yellow River (Huang He), 2nd longest in Asia, 6th longest in the world

Shandong is one of China’s wealthiest and most populous provinces, with much to attract the tourist.

Southern Chinese claim to have myriad mountains, rivers and geniuses, but Shandong citizens smugly boast they have one mountain (Tai Shan), one river (the Yellow River) and one saint (Confucius) – all that is needed.

Tai Shan is not only the most revered of China’s five holy Taoist peaks, it is the most climbed mountain on Earth.

It is said that if you climb Tai Shan you will live to be 100.

In ancient Chinese tradition, the sun began its westward journey from Tai Shan.

Tai’an is the gateway town to the sacred Tai Shan and the hometown of Jiang Qing, Mao’s 4th wife, ex-actress and the leader of the Gang of Four, on whom all of China’s ills are often blamed.

Above: Jiang Qing (1914 – 1991)

The Dai Temple is in the centre of town.

The Temple is a magnificent structure with yellow tiled roofs, red walls and ancient towering trees.

It is one of the largest and most celebrated temples in China.

100 km south is the dusty rural town of Qufu, the birthplace, residence and final resting place of Confucius – a teacher largely unappreciated in his lifetime.

Above: The Apricot Platform, Confucius Temple, Qufu, Shandong Province, China

Qufu is a harmony of carved stone, timber and imperial architecture, of airy courtyards, cypress trees and green grass, of twisted pines and mighty steles, singing birds serenade the seated souls upon quiet benches, unpolluted streets with little traffic, dusty, musty, home to the Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansions, the Confucian Forest…

To the south of the peninsula, the picture perfect town of Qingdao (also called Tsingtao)(Green Island) is called China’s Switzerland, which is surprising as its appearance is more reminiscent of a kind of Bavaria by the sea: cool sea breezes, balmy summer evenings, excellent seafood from dried fish shops, a Lutheran church, a German palace, and beaches of coarse sand covered in seaweed and bordered by concrete huts and stone statues of dolphins.

Above: Pictures of Qingdao

Jinan, the provincial capital is for most travellers a transit point on the road to other destinations, a city more famous for the celebrities it produced than for any virtues the city itself may possess: the film star Gong Li; Bian Que, the founder of traditional Chinese medicine; Zou Yan, the founder of the Yin and Yang five element school; Zhou Yongnian, the founder of China’s public libraries; and a number of nationally and internationally recognised writers.

Above: Pictures of Jinan

Above: Bian Que (or Qin Yueren)(died 310 BC)

Among these writers is the Song Poet.

Above: Statue of Li Qingzhao (1084 – 1155), Li Qingzhao Memorial, Jinan

Li Qingzhao is famed for her elegant language, strong imagery and her ability to remain unpretentious in her poetry:

Above: Li Qingzhao Memorial, Baotu Spring Garden, Jinan, Shandong Province, China

“Alone in the night, the warm rain and pure wind have just freed the willows from the ice.

As I watch the peach trees, spring rises from my heart and blooms on my cheeks.

My mind is unsteady, as if I were drunk.

I try to write a poem in which my tears will flow together with your tears.

My rouge is stale.

My hairpins are too heavy.

I throw myself across my gold cushions, wrapped in my lonely doubled quilt and crush the phoenixes in my headdress.

Alone, deep in bitter loneliness, without even a good dream, I lie, trimming the lamp in the passing night.”

As I type these words I wonder whether 16-year-old Chen Xin ever read these words of the Song Poet and felt herself identify with this poem, when she was growing up 1,000 km north of Shandong in the sub-Siberian wilderness of Heilongjiang Province, or when she was involuntary a resident of Linyi, or later when she returned to Heilongjiang traumatised from her Linyi experience.

Linyi (“close to the Yi River”) is a city in the south of Shandong Province and though it is not far from Yellow Sea ports and it sits astride the G2 Beijing-Shanghai Expressway, and though it has a history of over 2,400 years and possesses an attractive Confucian temple, Linyi’s claim to fame lies in it being a major centre of human rights abuses in China.

Above: Lin Yi Confucius Temple

Though Linyi has been home to many historical figures, notably Zhuge Liang (former Prime Minister and considered to be the most accomplished strategist of his era akin to Sun Tzu, the author of The Art of War) and Wang Xizhi (considered to be the greatest master of Chinese calligraphy that ever lived), most modern Chinese might recall the names of Chen Guangcheng (the barefoot lawyer) and Yang Yongxin (the brain waker) and, as a result, feel some compassion for the sad tale of Chen Xin.

Chen Guangcheng is the youngest of five brothers of a peasant family from the village of Dongshigu, Yinan County, Shandong Province.

When Chen was about six months old, he lost his sight due to a fever that destroyed his optic nerves.

His village was poor, with many families living at a subsistence level.

Chen’s father worked as an instructor at a Communist Party school.

When Chen was a child, his father would read literary works aloud to him and helped impart to his son an appreciation of the values of democracy and freedom.

In 1989, at the age of 18, Chen began attending school at the Elementary School for the Blind in Linyi.

In 1991, Chen’s father gave him a copy of The Law Protecting the Disabled, which elaborated on the legal rights and protections in place for disabled people in China.

In 1994, he enrolled at the Qingdao High School for the Blind where he remained until 1998, where he began developing an interest in law and would often ask his brothers to read legal texts to him.

Chen first petitioned authorities in 1996, when he travelled to Beijing to complain about taxes that were incorrectly being levied on his family.

(People with disabilities, such as Chen, are supposed to be exempt from taxation and fees.)

The complaint was successful and Chen began petitioning for other individuals with disabilities.

Chen became an outspoken activist for disability rights within the China Law Society.

His reputation as a disability rights advocate was solidified when he agreed to defend an elderly blind couple whose grandchildren sufered from paralysis. The family had been paying all of the regular taxes and fees, but Chen believed that, under the law, the family should have received government assistance and exemption from taxation. When the case went to court, blind citizens from surrounding counties were in attendance as a show of solidarity. The case was successful and the outcome became well-known.

Chen studied at the Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine from 1998 to 2001, specializing in acupuncture and massage – the only progrms available to the blind. He also audited legal courses, gaining a sufficient understanding of the law to allow him to aid his fellow villagers when they sought his assistance.

While studying in Nanjing, Chen learned that a program the leaders of Chen’s home village – implementing a land use plan that gave the authorities control over 60% of the land, which they then rented out at high cost to the villages – was illegal, he petitioned central authorities in Beijing to end the system.

In 2000, Chen returned from his studies in Nanjing to his village of Dongshigu in an effort to confront environmental pollution.

A paper mill constructed in 1988 had been dumping toxic wastewater into the Meng River, destroying crops and harming wildlife, as well as causing skin and digestive problems among villagers living downstream from the mill.

Chen organised villagers in his hometown and 78 other villages to petition against the mill. The effort was successful and resulted in the suspension of the paper mill.

In addition, Chen contacted the British Embassy in Beijing, informing them of the situation and requesting funding for a well to supply clean water to locals. The British government responded by providing funds towards a deep water well, irrigation systems and water pipelines.

After graduation from Nanjing, Chen returned to his home region and found a job as a masseur in Yinan County Hospital.

Chen met his wife, Yuan Weijing, in 2001, after listening to a radio show. Yuan had called into the show to discuss her difficulties in landing a job after graduating from the foreign language department of Shandong Chemistry Institute. Chen, who listened to the program, contacted Yuan and relayed his own story of hardship as a blind man. Moved by the exchange, Yuan travelled to Chen’s village to meet him.

The couple eloped in 2003. Yuan, who had been working as an English teacher, left her job in order to assist Chen in his legal work. Their son, Chen Kerui, was born later that year.

In March 2004, more than 300 residents from Chen’s village filed a petition to the village government demanding that they release the village accounts – which hadn’t been made public for 10 years – and address the issue of illegal land requisitions. When Dongshigu authorities failed to respond and villagers escalated their appeals to the township, county and municipal governments without response, village authorities began to threaten the villagers.

In November 2004, Chen acted on behalf of the villagers.

In 2005, Chen spent several months surveying residents of Shandong Province, collecting accounts of forced, late term abortions and forced sterilization of women who stood in violation of China’s one-child policy.

(In 2005, Chen and Yuan had a second child, a daughter named Chen Kesi, in violation of this one-child policy.)

Though Chinese central authorities have sought to curb the coercive enforcement of the one-child policy since 1990 by replacing measures such as forced abortions and sterilisations with a system of financial incentives and fines, Chen found that coercive practices remained widespread, documenting numerous cases of abuse.

Chen’s survey, based in Linyi, found an estimated 130,000 residents in the city had been forced into “study sessions” for refusing abortions or violating the one-child policy, imprisoned for days or weeks and beaten.

The case garnered international media attention.

The local authorities in Linyi retailiated against Chen, placing him under house arrest and embarking on a campaign to undermine his reputation, portraying him as working for “foreign anti-China forces”. The authorities threatened to levy criminal charges against Chen for providing state secrets or intelligence to foreign organisations.

Xinhua, the news agency of the Chinese government, stated that on 5 February 2006, Chen instigated others to damage and smash cars belonging to the Shuanghou Police Station and the Linyi government as well as attack local government officials.

Time reported that witnesses disputed the government’s version of events and Chen’s lawyers argued that he couldn’t have committed the crimes as he was already on house arrest and under constant surveillance by the police.

On the eve of Chen’s 18 August 2006 trial, all three of his lawyers were detained by Yinan police.

Neither Chen’s lawyers nor his wife were allowed in the courtroom for the trial.

Chen was sentenced to four years and three months for “damaging property and organising a mob to disturb traffic”.

Frank Ching, Globe and Mail (Toronto, Canada) columnist criticised the verdict:

“Even assuming Chen did damage doors and windows, as well as cars, and interrupt traffic for three hours, it is difficult to argue that a four-year prison sentence is somehow proportionate to the offence.”

Amnesty International declared Chen to be a prisoner of conscience, “jailed solely for his peaceful activities in defence of human rights.”

Above: The logo of Amnesty International

After his release in 2010, Chen was placed under house arrest against Chinese law and was closely monitored by security forces. Legally, he was proclaimed by the government to be a free man, but in reality the local government offered no explanation for the hundreds of unidentified agents monitoring his house and preventing visitors or escape.

Chen and Yuan attempted to communicate with the outside world via video tape and letters, describing beatings they were subjected to, seizure of documents and communication devices, cutting off of electric power to their residence, placing metal sheets over their windows, harassing Chen’s daughter by banning her from attending school and confiscating her toys, harassing Chen’s mother while she was working in the fields…

In 2011, the New York Times reported that a number of Chen’s supporters and admirers had attempted to penetrate the security monitoring Chen’s home, but were unsuccessful and subsequently pummeled, beaten and robbed by security forces. US Congressman Chris Smith attempted to visit Chen but was denied permission. Actor Christian Bale (Batman Begins) attempted to visit Chen along with a CNN crew, but was punched, shoved and denied access by Chinese security guards. Video footage showed Bale and the CNN crew having stones thrown at them and being pursued in their minivan for more than 40 minutes.

Above: Congressman Chris Smith of New Jersey

Above: Actor Christian Bale

On 22 April 2012, Chen escaped from house arrest. Under cover of darkness and with the help of his wife, Chen climbed over the wall around his house, breaking his foot in the process.

When he came upon the Meng River, Chen found it to be guarded, but he crossed anyway and was not stopped. He fell more than 200 times during his escape, but reached a pre-determined rendezvous point where He Peirong, an English teacher and activist, was waiting for him. Human rights activists then escorted him to Beijing.

Chen was given refuge at the US Embassy in Beijing. On 4 May, Chen made clear his desire to leave China for the United States. On 19 May, Chen, Yuan and their two children, having been granted US visas, departed Beijing for Newark, New Jersey.

Following his arrival in the US, the Chen family settled in a housing complex of New York University, in New York City’s Greenwich Village.

On 16 October 2013, Chen made his first public appearance, delivering a lecture at Princeton University.

Chen reminded the audience that even small actions undertaken in defense of human rights can have a large impact, because…

“Every person has infinite strength. Every action has an important impact. We must believe in the value of our own actions.”

Chen’s memoir, The Barefoot Lawyer, was published in 2015.

In February 2016, a young girl, Chen Xin, was forcibly taken away from her home in northern Heilongijang Province by two strange men in a car and driven to Linyi.

At the Internet Addiction Treatment Center, a boot camp at Linyi Mental Hospital, more than 6,000 Internet addicts – most of them teenagers – not only have their web access taken away, they are also treated with electro-shock therapy.

The boot camp is run by the “brain-waker” Yang Yongxin.

Yang, born in Linyi, graduated from Yishui Medical School, with a degree in Clinical Medicine in 1982. After graduation, Yang was aasigned by the state to the Linyi Mental Hospital, where he specialises in treating schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Yang started to investigate Internet addiction in 1999, when his teenage son began to show “addictive behaviour”. He began practicing electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in 2006.

Initially the Chinese media viewed Yang’s work with great enthusiasm, publishing a book called Fighting the Internet Demon and producing a documentary film of the same name.

Yang was awarded as one of 2007’s Top Ten Outstanding Citizens of Shandong Province “for protecting the minors of Shandong”.

Yang caused widespread controversy in China when China’s most viewed TV channel, state-run CCTV, aired a special coverage of Yang’s treatment centre in July 2008. The program, Fighting the Internet Demon Who Turned Our Geniuses into Beasts, reported positively on Yang’s ECT and sharply criticised the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, Irvine, California), then popular in China, blaming the game for many teenagers’ Internet addiction. The program caused an uproar in China’s World of Warcraft community, spreading to most of China’s Internet community. Yang’s critics revealed Yang’s controversial practices…

Yang claimed that patients with Internet addiction suffered from cognitive and personality disorders and he promoted electroconvulsive therapy as a means to remedy such disorders.

Yang’s patients ranged from 12 to 30 years old, most of whom were abducted by their parents or by “the Special Operation”, a branch of the treatment centre that would reward more senior patients to abduct new patients. The parents (even those of adult patients) would then sign a contract with the treatment centre, in which the parents would place the patients into foster care by the treatment centre.

Qu Xinjiu, a law professor at China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing said that the belief that parents have supreme jurisdiction over their children, and that even police officers have no right to intervene in family affairs, is widespread in China.

“That’s why there are so many parents sending their kids for electroshock therapy, even when outsiders think it’s wrong to do so.”, Professor Qu said.

After they were admitted, Yang’s patients were placed into a prisonlike environment, where they were forced to give away all online accounts and passwords. Yang managed his patients in a military style, where he encouraged the patients to act as informants and threatened resisting patients with ECT, as a means of torture.

In addition to electroconvulsive therapy, Yang used psychotropic drugs without the consent of the patients or their parents, claiming that the drugs were dietary supplements. The centre also has mandatory sessions with psychiatric counselors, where patients were taught absolute obedience to Yang and forced to call him “Uncle Yang”. He also warned the patients against asking their parents to take them home, another offense punishable by electroconvulsive therapy.

(All of this reminds me of the movie, starring Jack Nicholson, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.)

In 2009 China Youth Daily published the news of a patient who had escaped Yang’s treatment centre. The escaped patient jumped out from a second floor window at the treatment centre. Yang’s ECT / psychotropic medication treatment, which Yang dubbed xingnao (brain-waking), triggered cardiac arrhythmia (uneven heart palpitations or irregular heartbeats) in the escaped patient, questioning the safety of Yang`s treatment.

Also the same year, a 15-year-old boy from southern Guangxi Province died after being beaten by staff two days after arriving at a camp treating Internet addiction.

Yang claimed that 96% of the patients treated by his electric therapy had shown improvement.

In 2009, the Chinese Health Ministry issued guidelines against using electroshock therapy for Internet addicts, but despite the Health Ministry’s policy, “punitive practices continue to victimise China’s youth” in Internet detox camps”, said Dr. Bax, assistant professor of sociology at Ewha Women’s University in Seoul, South Korea.

In 2014, researchers from universities in Chian, Taiwan and Germany wrote in the journal Asia-Pacific Psychiatry that the highest prevalence of “problematic Internet use” had been observed in Asia.

A series of scandals have erupted in previous years over the treatment of patients at similar camps in China.

In 2014, a 19-year-old woman died at a treatment centre in Henan Province after being given treatment that involved being lifted off the ground and then dropped, the South China Morning Post reported, while another suffered head and neck injuries. Staff suspected the woman was feigning injury and continued to kick her on the ground, according to a China National Radio report.

Chen Xin’s parents had become concerned about her behaviour after she dropped out of school. On the suggestion of an aunt, the Chen family decided to send Xin to the camp, which had claimed to have cured 7,000 children of Internet addiction in the past two decades. The camp had become a last resort as they had become exasperated by their child’s habit of playing online games for hours.

Xin escaped the Internet Addiction Centre four months later.

In an online journal Xin complained that the centre’s trainers had beaten patients for no reason and ordered those who did not behave to eat in front of the pit latrine (sewer).

Thepaper.cn said it had received calls from several patients at the camp since they ran Chen’s story. They complained of being beaten, cursed at and insulted, of being watched even when using the toilet.

One former patient told Thepaper.cn:

“When the toilets clogged up, we were asked to empty the toilets with our hands. You get beaten up in the toilet and get beaten up again if you dare say no. You get beaten up if you are found to be in a relationship.”

In a journal post published 25 August 2016, Xin wrote:

“When you mentioned it to your relatives, they all said: ‘Isn’t it all in the past? We love you. You should forget all those things.’

I am angry. People point at my nose and call me unfilial (unloving daughter) and worse than a beast.

It was them who sent me there. It was them who cursed me and beat me. It was them who sabotaged my life and libelled my character, but it was also them who said they loved me.

My friends here, if it were you, what would you do?

I will use their money to practice boxing and martial arts and ambush them later. I will make them disabled, if not die.”

On 16 September 2016, Xin stabbed her father with a knife after they argued. He was hospitalised.

She tied her mother to a chair, shot photographs and a video of her mother, demanding money from her aunt to release her so Xin could go to a physics school in Harbin, the capital of Heilongjiang Province.

The money was sent the following week, but by then Xin discovered her starving mother was already dying. She called an ambulance, but it arrived too late.

Xin’s mother died on 23 September 2016.

In January 2017, the Chinese government drafted a law that will crack down on the camps’ worst excesses.

Medical specialists welcomed the law.

“It’s a very important move for protecting young children.”, said Dr. Tao Ran, director of the Internet Addiction Clinic at Beijing Military General Hospital.

Dr. Tao has seen several Chinese teenagers return from Internet addiction boot camps showing signs of lasting psychological trauma:

“They didn’t talk, were afraid to meet people and refused to leave their homes. They were panicked even to hear the word ‘hospital’ or ‘doctor’.”

The legislation also limits how much time each day that minors can play online games at home or in Internet cafés. Providers of the games are obliged to take measures to monitor and restrict use.

Many users of Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, were even more critical, saying policing teenage behaviour online is impractical and ill-informed.

Above: The logo for Sina Weibo

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 12 March 2017

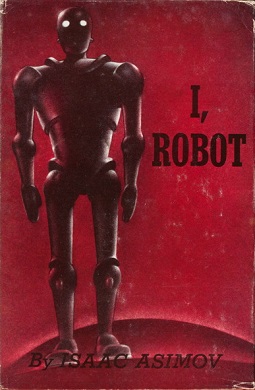

As I read over what I have written I am struck by a memory of Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, published in 1953.

The novel presents a future American society where books are outlawed and “firemen” burn any that are found. Bradbury described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.

In Part One of the book, my mind’s eye can still recall Guy Montag, the book’s protagonist, and the other firemen ransacking the book-filled house of an old woman. She refuses to leave her house and her books, choosing instead to burn herself alive. Like Montag I am discomfited by the woman’s suicide.

Montag’s boss, Captain Beatty, personally visits Montag to see how he is doing. Sensing Montag’s concerns, Beatty recounts how books lost their value, how over the course of several decades people embraced new media and sports and a faster pace of life. Books were ruthlessly abridged or degraded to accommodate a short attention span. Books were burned in the name of public happiness.

In Part Two, I recall Montag telling his wife that maybe the books of the past have messages that can save society from its own destruction. But Mildred is only interested in their large screen television. She invites her friends over to watch TV with her. Montag tries to engage them in meaningful conversation, but they are indifferent to all but the trivial.

And I wonder:

Is this the future?

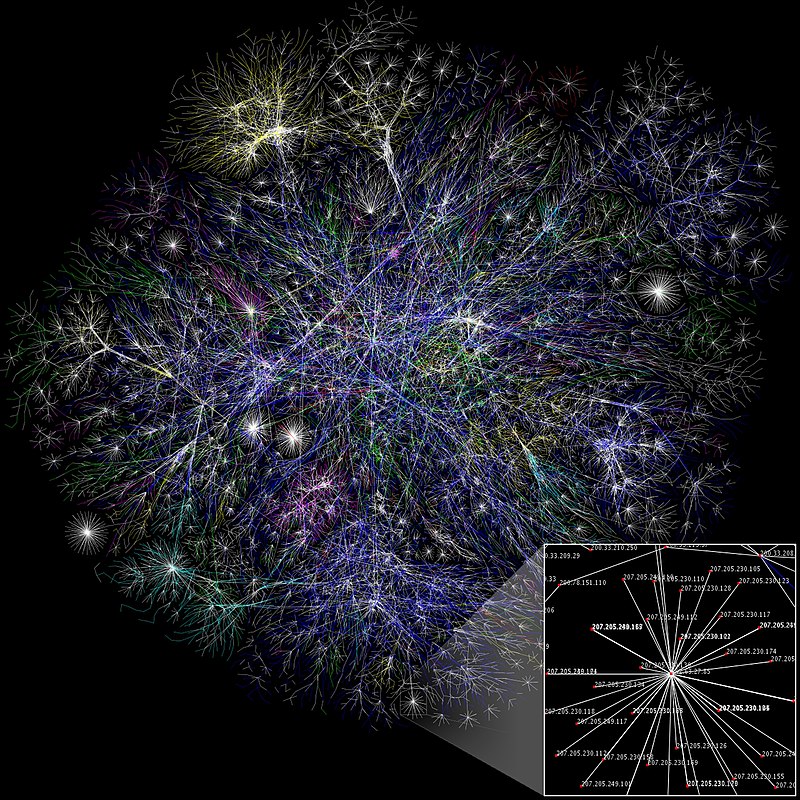

Above: A visualisation of a portion of the routes on the Internet

Have we become a society that has become addicted to distraction?

A society oblivious to everything, everyone, unconnected, disconnected to flat screens or headphones?

It is easy to condemn the acts of the Chinese state for attempting to gain control over its citizens seduced by technology and mass media, or for using technology or mass media to control its populace, but perhaps, both in the Orient as well as the West, it is the people, us, who are as much culpable as the state.

Perhaps the enemy we seek lies in the reflection cast by our flat screens?

Sources:

Wikipedia / Thomas L. Friedman, “Our lives are digital. Be careful.”, 12 January 2017, New York Times / Mike Ives, “China seeks to curb Internet addiction camps”, 17 January 2017, New York Times / Rough Guides China / Lonely Planet China