Landschlacht, Switzerland, 19 March 2017

Everyone has their own ideas about what is wrong with the world.

We will argue amongst ourselves about which are the most important issues.

But I think we all agree that things could be a lot better than they are.

Something really needs to be done.

We are all fired up with passion, with a thirst to change the world.

But then what?

Do we just leave it to governments and international institutions?

Or are there things we can do that will actually make a difference?

The issues that confront us are HUGE, complicated, difficult.

It is hard to believe that anything we can do will have a meaningful impact.

But…there are a lot of us in the world.

A lot of people doing a lot of little things could have a HUGE impact.

By doing something, we also demonstrate that lots of people really do care.

That isn’t only a world of sadness and sorrow, of only the bad and corrupt, it is also filled with average, ordinary, loving, compassionate people.

So where should you begin?

Begin with you.

San Francisco, California, 26 November 1974

“What would happen if I forced myself over a period of several months to sluice my mind the way I sluiced dirt in my gold-hunting days, using a journal as a sluicebox to trap whatever flakes of insight might turn up?”

Eric Hoffer asked himself this question in his journal.

He did NOT expect a happy outcome.

“I had the feeling that I had been scraping the bottom of the barrel and I doubted whether I would ever get involved in a new seminal train of thought.

Would it be possible to reanimate and cultivate the alertness to the first faint stirrings of thought?”

No philosopher’s beginnings were messier than Eric Hoffer’s.

“You might say I went straight from the nursery to the gutter.”, Hoffer confessed in an interview.

Hoffer was born in 1898 in the Bronx of New York City to Knut and Elsa Hoffer.

His parents were immigrants from Alsace.

Above: Flag of Alsace, France

By age 5, Hoffer could already read in both English and his parents’ native German.

That same year, Elsa fell down the stairs with him in her arms.

She did not recover and died in the second year after the fall.

Hoffer lost his sight.

At the age of 9, Hoffer was told by Martha, who raised him after Elsa’s death and the person he trusted the most, that – with his short-lived parents’ genes – he would definitely not live past the age of 40.

“I believed her absolutely.

When I was almost 20, my life was half over, so what was the point of getting excited about anything?”

Hoffer’s sight inexplicably returned when he was 15.

Fearing he might lose it again, Hoffer seized on the opportunity to read as much as he could.

His recovery proved permanent, but Hoffer never abandoned his reading habit.

Hoffer was a young man when he also lost his father Knut.

The cabinetmaker’s union paid for Knut Hoffer’s funeral and gave Eric about $300 insurance money.

“I made up my mind to go to California because California was the place for the poor.

So I bought a bus ticket to Los Angeles and I landed on Skid Row and I stayed there for the next ten years.”

He still kept reading, occasionally writing, and working at odd jobs.

In 1931, Hoffer considered suicide by drinking a solution of oxalic acid, but he could not bring himself to do it.

He left Skid Row and became a migrant worker, following the harvests in California.

Hoffer did only manual work: dishwashing, claw-the-Earth prospecting, railroading, lumbering, migrant farmwork and later mostly waterfront day labour on the San Francisco docks.

A loner all his life, Hoffer was entirely self-educated.

Hoffer was a voracious reader.

He had library cards from virtually every library up and down the California railroad lines.

There was no subject he was afraid to tackle, no author who intimidated him.

Yet he felt no compulsion to pursue, let alone admire, certain authors generally considered essential reading for an intellectual.

Hoffer freely admitted never to have read Freud and confessed he “never got anything from Plato.”

Above: Bust of Plato (428 BC – 348 BC)

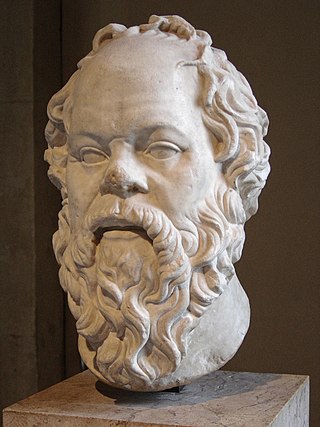

“Socrates was supposed to be a workingman, wasn’t he?

Above: Bust of Socrates (470 BC – 399 BC)

A stonemason or something.

But this is not the way a self-taught mason would argue.

He would tell stories to illustrate his points.

How can you convince anybody by going after him the way Socrates did – another question, another question – showing him how stupid he is?”

Prospecting for gold in the mountains and snowed in for the winter, Hoffer read Montaigne’s Essays and Hoffer had his first flash that he himself might become a writer:

Above: Original manuscript of Michel de Montaigne’s Essais

“Here was this 16th century aristocrat…and I found out that he was talking about nothing else but Eric Hoffer!

Above: Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592)

That’s how I learned about human brotherhood.”

Montaigne impressed Hoffer deeply and Hoffer often made reference to him.

He also developed a respect for America’s underclass, whom he said was “lumpy with talent.”

Hoffer was influenced by his modest roots and working class surroundings, seeing in it vast human potential.

“When I got out of the woods and back to town, I had money.

First I bought all new clothes and threw the old ones away.

Then I went to the Japanese barber where he and his wife not only cut my hair but got way down into my ears and nose to clean them out.

Then I got myself a room halfway between the library and the whorehouse.

Both were equally important.”

Hoffer wrote a novel, Four Years in Young Hank’s Life, and a novella, Chance and Mr. Kunze, both partly autobiographical.

He also penned a long article based on his experiences in a federal work camp, “Tramps and Pioneers”.

Hoffer tried to enlist in the US Army at age 40 during World War II but was rejected because of a hernia.

He began work as a longshoreman on the docks of San Francisco in 1943 and began to write seriously.

“A common labourer who had been blind in childhood, who had then recovered his eyesight and proceeded to educate himself entirely by his own efforts, whose reading had been broader and deeper than that of many leading intellectuals in United States and Europe, whose ideas were frequently more penetrating and provocative than theirs, and whose prose style was a monument to economy and precision.

‘Who the hell is Eric Hoffer?’, I asked myself as I read his books and how did he happen?” (James Koerner)

How Hoffer “happened” – how he found his ideas, cultivated them and did his research – was outrageously unconventional and wonderfully quickening for our own creativity.

“I’m not a professional philosopher.

My train of thought grew out of my life just the way a leaf or a branch grows out of a tree.”

Hoffer’s thinking and writing occurred as a regular part of his life.

In one of his books Thinking and Working on the Waterfront, Hoffer wrote:

“My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight, in the fields while waiting for a truck and at noon after lunch.

Now and then I take a day off to ‘put myself in order’.

I go through the notes, pick and discard.

The residue is usually a few paragraphs.

My mind must always have something to chew on.

I think on man, America and the world.

It is not as pretentious as it sounds.”

Hoffer described how a specific key idea came to him out of an immediate experience.

One day on the docks he drew as partner the worst worker there, a clumsy and inept man avoided by everyone.

“We went to work and started to build our load.

On the docks it’s very simple – you build your side of the load and your partner builds his side, half and half.

But that day I noticed something funny.

My partner was always across the aisle, giving aid to somebody else.

He wasn’t doing his share of the work on our load, but he was helping others with theirs.

There was no reason to think he disliked me.

But I remember how that day I got started on a beautiful train of thought.

I started to think why it was that this fellow, who couldn’t do his own duty, was so eager to do things above and beyond his duty.

And the way I explained it was that if you are clumsy in doing your duty, you will be ridiculous, but that you will never be ridiculous in helping others – nobody will laugh at you.

That man was trying to drift into a situation where his clumsiness would not be conspicuous, would not be blamed.

And once I started to think like that, I abandoned him entirely.

My head was in orbit!

I started to think about avant-garde, about pioneering in art, in literature.

Above: Film The Love of Zero (1927)

I thought that all people without real talent, without skill, whether as writers or artists and so on, will try to drift into a situation where their clumsiness will be natural and expected.

What situation will that be?

Of course – innovation.

Everybody expects the new to be ill-shapen, to be clumsy.

I said to myself, the innovators, with a few exceptions, are probably people without real talent and that’s why practically all avant-garde art is ugly.

But these people, these innovators, have a necessary role to play because they keep things from ossifying, they keep the gates open and then eventually a man with real talent will move in and make use of the techniques worked out by clumsy people.

A man of talent can make use of any technique.

Oh, I worked and worked on this train of thought.

I was excited all day long and I have a whole aphorism that came as a result.

When I got back to my room all I had to do was write it down.

It often happened to me just that way – and all on the company’s time!”

To give his ideas finished form, Hoffer retreated to Golden Gate Park, following a favourite path down to where the Park meets the ocean.

The walk took him about an hour from where the bus left him at the entrance, which was just right for chewing over the concept or problem he had selected for scrutiny.

Then, sitting on a bench facing the Pacific, he transcribed the product of his thinking in his notebook, “adding crumb to crumb”.

Hoffer hated “intellectuals”, but by the term “intellectual”, he did NOT mean men and women of the mind who pursue truth and understanding for its own sake – he exemplified that breed.

The criterion for “intellectual” in his lexicon was not a passion for truth but a passion for power, especially power over people.

He defined an “intellectual” as “a self-appointed soul engineer who sees it as his sacred duty to operate on mankind with an axe.”

“I am not venting any personal grievance against the intellectual.

They have treated me fine, but anyone who wants to be a member of an elite goes against my grain, and that’s what the intellectuals who now make most of the noise really want.”, Hoffer insisted.

Hoffer knew from his own experience that intelligence, perceptiveness, understanding, mental capacity, indeed wisdom are far more widely diffused among people than we usually imagine.

“Every ‘intellectual’ thinks that talent, that genius is a rare exception.

It’s not true.

Talent and genius have been wasted on an enormous scale throughout our history.

This is all I know for sure.”

Hoffer knew for sure because he developed his own ideas through discussion with the men with whom he worked and spent his leisure time – suggesting that we too might find far more intellectual stimulation among such people than we might expect.

“I have never felt cut off intellectually, but I have never associated with literary people.

I could always talk to the people around me and discuss my ideas with them.

All experiences are equidistant from an idea if your mind is keyed up.

The crucial factor is not the set of circumstances in which we find ourselves, but the ‘keyed-up’ mind.”

In a nutshell, keeping a journal is the best way to cultivate your own “alertness to the first, faint stirrings of thought.”

Above: Facsimile of orignal diary of Anne Frank on display in Berlin

“It is more than six months since I started this diary.

I wanted to find out whether the necessity to write something significant every day would revive my flagging alertness to the first, faint stirrings of new ideas.

I also hoped that some new insight caught in flight might be the seed of a train of thought that could keep me going for years.

Did it work?

The diary flows, reads well and has something striking on every page.

Here and there I suggest that a new idea could be the subject of a book, but only one topic, ‘the role of the human factor’, gives me the feeling that I have bumped against something which is, perhaps, at the core of our present crisis.”

Virtually every important writer and thinker has kept a journal.

For example, Leonardo da Vinci, Abraham Maslow, Franz Kafka, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevski, Francoise du Maurier, Eugene Delacroix, William Gibson, Paul Gauguin, John Steinbeck and Gertrude Stein all kept notebooks or journals in which they shared their thoughts and work, in steps small enough so that we can easily follow.

“Every intellectual used to keep a journal and many have been published and are more interesting and more instructive than the final formal perfected pages which are so often phony in a way – so certain, so structured, so definite.

The growth of thought from its beginnings is also instructive – maybe even more so for some purposes.” (Abraham Maslow)

Above: Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970)

You will gradually find your own best method of generating thoughts.

The crucial thing is to start.

It is the doing that teaches us how.

“You might start by clipping and pasting newspaper articles that interest you for the next 30 days.

At the end of that time, see if there isn’t any trend suggestive of a deep-seated interest or natural inclimation.

Keep alert each day…” (Dr. Ari Kiev)

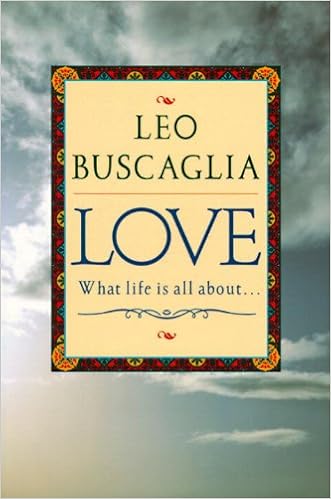

A book I cannot imagine living without is a psychology / philosophy book by Felice Leonardo Buscaglia, aka Leo Buscaglia, with the simple title: Love.

Above: Professor Leo Buscaglia (1924 – 1998)

I love this warm and wonderful book and the way Buscaglia envelops the reader in his warm embrace through his quiet simple manner.

“…they didn’t know about Papa’s rule that before we left the table, we had to tell him something new we had learned that day.

We thought that this was really horrible – what a crazy thing to do!

While my sisters and I were washing our hands and fighting over the soap, I’d say:

‘Well, we’d better learn something.’

We’d dash to the encyclopedia and flip to something like ‘The population of Iran is…’

Above: Flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran

We’d mutter to ourselves ‘The population of Iran is…’

We’d sit down and after a dinner of great big dishes of spaghetti and mounds of veal so high you couldn’t even see across the table, Papa would sit back and take out his little black cigar and say, “Felice, what did you learn new today?”

And I’d drone ‘The population of Iran is…’

Nothing was insignificant to this man.

He’d turn to my mother and say, ‘Rosa, did you know that?’

She’d reply, impressed, ‘No.’

We’d think ‘Gee, these people are crazy.’

But I’ll tell you a secret.

Even now going to bed at night, so exhausted as I often am, I still lie back and say to myself, ‘Felice, old boy, what did you learn new today?‘.

And if I can’t think of anything, I’ve got to get a book and flip to something before I can get to sleep.

Maybe this is what learning is all about.’

(Leo Buscaglia, Love)

I think keeping a journal is more than just recounting the events of your day.

It is about what you have learned from those events and from that day.

“He had no education, save that of experience.”

(Mahatma Gandhi, An Autobiography)

Gandhi’s father was not educated beyond the elementary grades and had nothing more than an education that gave him basic literacy.

“Of history and geography he was innocent.”, Gandhi wrote.

Nevertheless. he judged that his father’s “rich experience of practical affairs” enabled him to solve “the most intricate questions” and prepared him to manage business.

Our age is obsessed with diplomas and certificates, which are, certainly, of value.

However, it is a big mistake to minimize the value of experience – the best teacher of all.

Let your journal show you what issue(s) are important to you, that deserve your time, attention and passion.

Use your journal to think about your issue(s) and why you want to see change.

Find out what you believe in.

Find something YOU wholeheartedly believe in – and most likely others will too.

So, tell me…

What did you learn today?

Sources: Wikipedia / Eric Hoffer, Working and Thinking on the Waterfront / Eric Hoffer, Before the Sabbath / Mahatma Gandhi, An Autobiography / Alan Axelrod, Gandhi CEO / Ronald Gross, The Independent Scholar’s Handbook / Lucy-Anne Holmes, How to Start a Revolution / Michael Norton, 365 Ways to Change the World / Adam Kerr, “All You Need is Cafuné”, The Chronicles of Canada Slim, 10 October 2015)