Landschlacht, Switzerland, 29 March 2017

You say you want a revolution, but you are not really sure where to start.

There are just so many things wrong with this world that demand change.

In this series A Revolution of One, I have written about the importance of passion and the value of keeping a journal to discover what potential lies within you.

(See: A Revolution of One: The Power of Passion and A Revolution of One: Seize the Day of this blog.)

So imagine you are now at the point where you have discovered some of the things that interest you.

What`s next?

You now need to do reconnaissance and discover what knowledge is out there.

“Most of my opinions on bookshops (and libraries) were formed by Donald Rumsfeld.

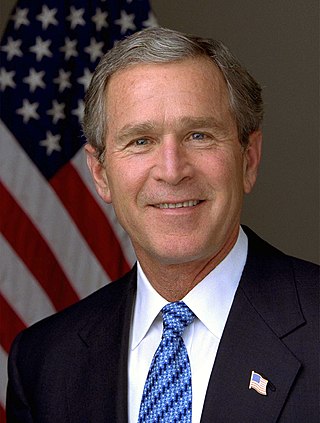

In case you’ve forgotten or never knew, Donald Henry Rumsfeld was the US Secretary of Defense in the administrations of Presidents Gerald Ford and George W. Bush….

Above: Gerald Ford (1913 – 2006), 38th President of the United States (1974 – 1977)

Above: George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States (2001 – 2009)

It is his opinion on the necessity of bookshops (and libraries) that truly binds us together.”

(Mark Forsyth, The Unknown Unknown: Bookshops and the Delight of Not Getting What You Want)

“There are things we know that we know.

There are known unknowns.

That is to say there are things that we now know we don’t know.

But there are also unknown unknowns.

There are things we do not know we don’t know.” (Donald Rumsfeld)

“For some reason that I shall never understand, there are those who find these lines perplexing.

They ridicule it.

The Plain English Campaign even awarded Rumsfeld their Foot in Mouth Award of 2003 for a ‘baffling comment by a public figure’.

But there’s nothing baffling in it really.

I know that Paris is the capital of France, but more importantly I know that I know Paris is the capital of France.

Above: The Eiffel Tower, Paris / Flag of France

I know that I don’t know the capital of Azerbaijan, although I am sure they have one.

Above: The flag of Azerbaijan

(It’s the sort of thing I really ought to check up on.)

But I do not know….

Well, here it gets complicated….

You do not know that you do not know the capital of Erewhon, because you had no idea that there was a country called Erewhon, and therefore you had no idea there was a gap in your knowledge.

Above: First edition (1872) of Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (or Over the Range)

You did not know that you did not know.

The same thing applies to books.

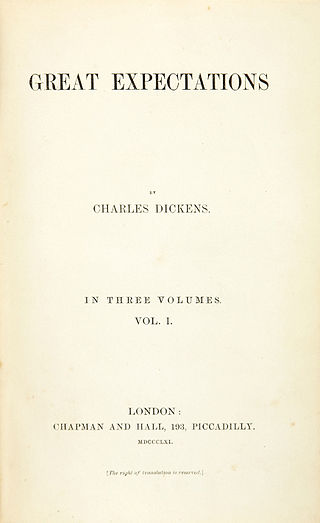

I know that I have read Great Expectations: it is a known known.

Above: Title page of 1st edition (1861) of Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations

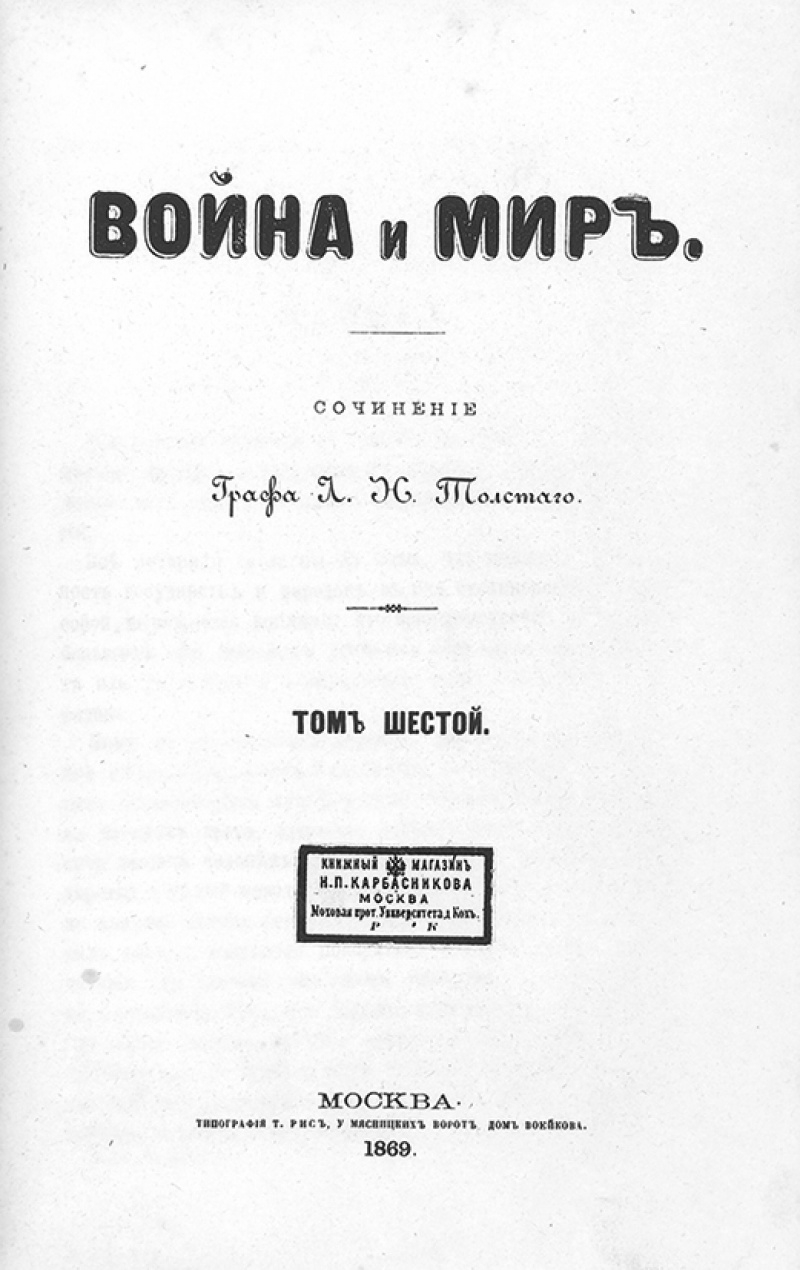

I know that I haven’t read War and Peace: it is a known unknown to me…

Above: Title page, 6th edition 1909, Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, in original Russian

(…and, barring a long prison sentence, is likely to remain so.)

But there are books I have never heard of.

And because I have never heard of them, I have no idea that I haven’t read them….

There are, as previously mentioned, three kinds of books: the ones you’ve read, the ones you know you haven’t read and the ones you didn’t know existed.

The books you’ve read, you don’t need to buy.

Presumably you bought (or borrowed) a copy before reading.

The famous books you haven’t read are easily obtainable on the Internet.

You type in War and Peace and all sorts of booktraders mention that they have it available for X amount of dollars/pounds/franks/etc and that a nice young man will bring it to your door by teatime.

I believe that here I ought to bemoan the modern age and go on and on about how human contact is lost and we are all going to Hell in a handbasket, but I just can’t.

The Internet is much too convenient….

…The Internet is a splendid invention and it won’t go away.

If you know you want something, the Internet can get it for you.

My point…is that it is not enough to get what you already know you wanted.

The best things are the things you never knew you wanted until you got them.

The Internet takes your desires and spits them back at you, consummated.

You search, you put in the words you know, the things that were already on your mind, and it gives you back a book or a picture or a Wikipedia article.

But that is all.

The unknown unknown must be found otherwise….

….Computers are machines.

The Internet is a huge army of machines.

Machines do not allow in the element of chance.

They do exactly what you tell them to do.

So the Internet means that, though you will get what you already knew you wanted, you will never get anything more.”

(Mark Forsyth, The Unknown Unknown: Bookshops and the Delight of Not Getting What You Want)

Above: Shakespeare and Company bookstore, Paris

“We have all browsed – in a bookstore or library or through someone else’s bookshelves.

Above: The Bookworm (1850), Carl Spitzweg

I am going to suggest an enhanced style of browsing that you can use as a way of finding new subjects of interest.”

(If you are already interested in a subject, you may want to skip the rest of this blogpost and visit the Internet.)

Even the most advanced scholars often find that wandering through the stacks of a library (or a bookshop), dipping into a book here and there as the spirit moves them, offers a serendipitious intellectual stimulation that is unavailable any other way.

By making the process of browsing more self-conscious, you can conduct your own informal reconnaissance of the terrain of learning.

All you have to do is follow three rules:

- Pick the best places.

- Keep moving.

- Keep a list.

By picking the best places, I simply mean the best library or bookstore or collection of other resources that you can find for your purposes.

Follow F. Scott Fitzgerald’s advice:

Above: F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896 – 1940)

‘Don’t marry for money – go where money is, then marry for love.’

Go where the richest resources are, then you can let serendipity take its course.

In a less rich environment, the items that might best turn you on might simply not be there.

What is the best place for you?

It is the best-stocked one within convenient range.

Many cities now have specialised bookstores, study centres and activists organisations or other agencies in numerous fields, one of which may be the right place for you once you have identified a broad field that you might get deeply interested in.

Once you are in the right place, keep moving and keep a list.

You are brainstorming, not postholding.

You want to get a comprehensive glimpse and taste of a wide range of works.

And you want to keep a log of your discoveries along the way, with notes in case you want to retrace your steps and delve more deeply.

You are compiling your ‘little black book’ of intellectual attractions – books, ideas, authors, points of views, realms of fact and imagination with which you want to make a date sometime, get to know better and, perhaps, come to fall in love with.

Major intellectual journeys (and social change) often begin with browsing.

As part of your browsing, you may want to take a fresh look at some of the important realms of learning, but from your own point of view.

The exhilirating prospect here is to ‘come to ourselves’ intellectually.

After years, sometimes decades, of learning for someone or something else we are now invited to begin using our minds for ourselves.

We are freed from being told what, why and how to learn.

We discover at once the first lesson of freedom in any realm:

Freedom is far more demanding than taking orders, but also far more rewarding.

Forget about which subjects you have already been told are important or prestigious.

Just let each one roll around in your head for a while to see whether it commands your interest.

Do not worry about how formidable each one sounds.

No one is a complete master of any of these realms.

Each category could fill years of study.

The point is to realise the wealth from which you can choose and to start modestly to sample one subject or another that especially appeals to you.“

(Ronald Gross, The Independent Scholar’s Handbook)

What makes an advocate for change organize that change?

Curiosity.

He/She is driven by a compulsive curiosity that knows no limits.

Life is a search for a pattern, for a meaning to the life around him/her and its relationship to his/her own life.

The search never ends.

There are no answers, only further questions.

The organizer/the advocate for change is a carrier of the contagion of curiosity.

It is in the question “Why?” that change can begin.

It is the questioning of the status quo, the delving into the “Why?” of accepted ways and values that the seeds of reformation and revolution begin to sprout.

Change begins with an individual.

Be the change you desire.