Landschlacht, Switzerland, 25 May 2017

We live in an age where we take for granted many things and we only seem to question things when they don’t happen as we think they should.

We live in an age where we casually accept what is, without questioning how it came to be.

The older I get, the more I am convinced that there is no such thing as coincidence.

We may not understand why things happen, but I believe that things happen (or don’t happen) for a reason, even if we don’t know what that reason is.

“God only knows.

God makes His plans.

The information is unavailable to the mortal man.

We work at our jobs.

Collect our pay.

Believe we’re gliding down the highway, when in fact we’re slip-sliding away.”

(Paul Simon, “Slip-Sliding Away”)

I recently discovered a book called Literaturführer Thurgau, which has me looking anew at the region where I live, through the eyes of writers who have experienced this region.

(See Dreams of Dragonflies of this blog for the start of my walking adventures tracing the literary figures of Canton Thurgau.)

Reading this book and as well about recent events have led me to consider the topic of flying.

I am very much like the John McClane character, portrayed by Bruce Willis, in the Die Hard movie series….

I hate flying.

Or, put another way, I am the composite antithesis of the Ryan Bingham character, portrayed by George Clooney, in the film Up In the Air, whereas Bingham lives to fly, I will fly only when I truly feel I have no other choice.

I am an English teacher who has found himself, much to my own surprise, teaching aircraft technicians and engineers, pilots and cabin crew, the necessary English they need to do their jobs more professionally.

So, ignorance is bliss…

For knowing what keeps a plane functioning, what allows it to fly, land and take off safely, and what passengers know and don’t know about the flight happening around them…

This knowledge does not comfort me.

I know what can go wrong.

I like to travel and to do so I have flown across continents and oceans.

I have been buffeted by winds that have caused my pants to get stained by coffee.

I have been bumped up to first class and have been bumped off flights that had been overbooked.

I have missed flights due to changes in either the airline schedule or my inability to meet the airline schedule.

All part of the experience…

Overbooking, also known as overselling, is the sale of a good or service in excess of the actual supply, or ability to supply, that good or service.

It is a common practice in the travel industry, because it is expected that some people will cancel or miss their flights.

By overselling, the supplier is ensured that 100% of the available supply will be used, resulting in the maximum return on the supplier’s investment.

But if most customers do wish to purchase or use the good or service, this practice of overselling leaves some customers lacking the good or service they paid for and expected to receive.

Overselling is regulated, but rarely prohibited.

Companies that practice overbooking are usually required to offer large amounts of compensation to customers as an incentive for them to not claim their purchase.

An alternative to overbooking is discouraging customers from buying services they don’t actually intend to use by making reservations non-refundable or requiring them to pay a termination fee.

An airline can book more customers onto a flight than can actually be accommodated by the aircraft, allowing the airline to have a full aircraft on most flights, even if some customers are denied their flight.

Airlines may ask for volunteers to give away their seats or refuse boarding to certain passengers in exchange for a compensation that may include an additional free ticket or an upgrade on a later flight.

Airlines can do this and still make more money than if they booked only to the plane’s capacity and had taken off with empty seats.

Some airlines do not overbook as a policy that provides incentive and avoids customer disappointment.

By making their tickets non-refundable, these airlines lower the chances of passengers missing their flights.

A few airline frequent flier programs allow a customer the privilege of flying an already overbooked flight, requiring other customers being asked to deplane.

Often it is only Economy Class that is overbooked, while higher classes are not, allowing the airlines to upgrade some passengers to otherwise unused seats while providing assurance to higher paying customers.

Chicago O’Hare Airport, 9 April 2017

Early April 2017 saw severe weather on the east coast of the United States, causing many flight cancellations.

Due to the large number of stranded passengers trying to board flights, many flights were far too overbooked.

On this date of 9 April 2017, United Airlines Express Flight 3411 was scheduled to leave O’Hare at 5:19 pm/1719 hours.

After passengers were seated in the aircraft, bound for Louisville, Kentucky, but while the plane was still at the gate, the flight crew announced that they needed to remove four passengers to accommodate four staff members who had to cover an unstaffed flight at another location.

Passengers were initially offered $400 US in vouchers for future travel, a hotel stay and a seat on a plane leaving more than 21 hours later, if they voluntarily deplaned.

No volunteers.

The offer was increased to $800 in vouchers.

Still no volunteers.

A manager boarded and informed the flight that four people would be chosen by computer (based on specific factors such as priority to remain aboard for frequent fliers and those who had paid higher fares).

Three of the computer-selected customers agreed to deplane.

The 4th selected passenger, Asian American 69-year-old Dr. David Dao of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, refused, saying he needed to see patients the next day at his clinic.

Above: Dr. David Dao (on the left) with his family

United Airlines decided it required assistance from Chicago Department of Aviation Security officers.

A security officer threw the Doctor against the armrest of his seat, causing injuries to the physician’s head and mouth (a broken nose, the loss of two front teeth, sinus injuries and a concussion), before dragging Dao down the aisle by his arms unconscious.

Other passengers on the flight recorded the incident on video using their Smartphone cameras and the incident was quickly and widely circulated on social media and was picked up by the mainstream media agencies.

The violent methods used by the security personnel distressed a number of passengers who voluntarily left the aircraft along with the three passengers who had been selected for deplaning.

Four United Airlines staff promptly sat in the now vacated seats.

The flight departed at 1921 hours – two hours and two minutes behind schedule – and arrived at Louisville at 2101 hours – two hours behind schedule.

Back in Chicago, Dao was taken to hospital and would require reconstructive surgery.

No one has been fired as a result of this incident, which could have been avoided had United simply had the computer choose another passenger when Dao had refused to leave.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 25 May 2017

Imagine how differently things might have been had the effects of overbooking and a methodology had been practiced to deal with dissatisfied customers by United.

In fairness, running an airline is not an easy task.

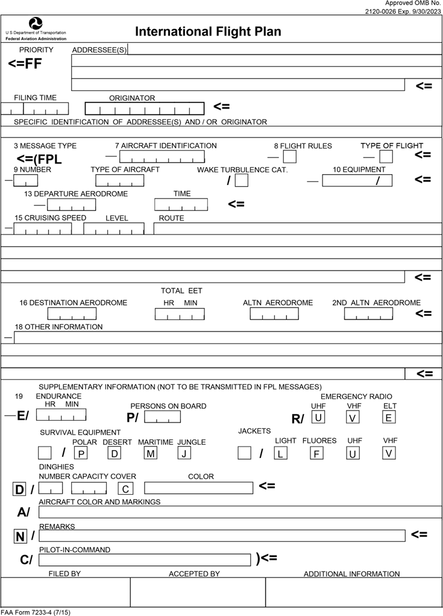

So far we have considered ourselves only with the issue of assigning and seating the passengers, but now let’s think about the men and women who actually pilot these aircraft.

What must they plan for?

Part of a pilot’s job is straightforward and traditional: inspecting the aircraft about to be piloted.

The pilot looks at the external surfaces of the aircraft for signs of damage, then he/she checks the nose undercarriage for excessive wear and the tires for any cuts.

The leading edges of the wings are inspected for damage, the fastenings on the engine cowling are checked and the visible fan blades on the engine are examined.

Moving along the fuselage to the tail, the pilot does the same visual checks over all surfaces before ensuring that all cargo doors and access hatches are securely fastened.

All pretty standard operating procedure….

But not only must the pilot be concerned as to whether the craft can fly, but as well thought must be brought to bear on the actual flight itself.

In the very early days of powered flight, pilots were contented with simply getting airborne and flying short distances.

Navigational aids did not exist and the basic technique followed was pilotage – flights were at low altitudes and the pilot simply looked out the window and navigated with reference to known landmarks.

In some cases, it was just a question of the pilot following a road, river or railway to the desired destination.

Planes nowadays fly further, so they need a method to find their way safely and efficiently to their final flight arrival.

As well an airplace can only carry a limited amount of fuel.

Failure to reach a destination before the fuel runs out might have fatal consequences.

In modern times all flights operate under VFR (visual flight rules) or IFR (instrument flight rules).

A VFR pilot is qualified and authorised to fly only in good weather conditions and is responsible for maintaining separation from other aircraft and obstructions based on what can be seen.

An IFR pilot is permitted to fly in all weather conditions, including when visibility may be low, relying on flight instruments and navigational aids to follow a safe course.

While an IFR pilot may still use VFR pilotage techniques, it is advisable for all pilots that their flights be planned careful before taking off, using detailed navigational charts.

Pilots plan their routes, taking into consideration natural obstacles and airspace which may be restricted, which they then mark on their charts.

Planning a flight is dependent upon a number of factors: topographical, geographical and meteorological.

An area needs to have been mapped out, navigational beacons established, geographical features noted and the weather conditions monitored.

But in the pioneering days of public air transportation, there were few maps, few beacons, few airports and few refuelling locations.

Before satellites, there was only one way to ascertain what route lay ahead, someone had to go there first.

As well, as any reader of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War can tell you, one cannot defeat a potential enemy if one is unprepared for the terrain upon which one might be forced to battle.

So geographical knowledge is not only an exercise in exploration, it is crucial for the planning of strategy, both politically and militarily.

Konstanz, Germany, 4 January 1927

It was a time of great change.

Germany was still the Weimar Republic and to reduce the state’s cost of funding two airlines, Deutsch Aero Lloyd and Junkers Luftverkehr, a merger of the two under the composite name of Deutsche Luft Hansa (German Air Hanseatic) was born on 6 January 1926.

British and Belgian troops had left German soil and many of the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, that marked Germany’s World War One defeat, had been lifted, enabling Deutsche Luft Hansa to expand its routes beyond the borders of Germany worldwide.

Luft Hansa planned an airline connection between Berlin and Beijing and needed to know the meteorological conditions of the land over which it planned to fly – Mongolia, the Gobi Desert and the Chinese province of Xinjian (then known as East Turkestan) – as well as possible locations for landing, weather monitoring and refuelling.

The top man for such an expedition, the only man capable of leading such an expedition, was someone who had experience in such matters.

Swedish geographer, topographer, explorer, photographer, travel writer and illustrator Sven Anders Hedin (1865 – 1952) was the man chosen to lead this Sino-Swedish Expedition of 1927 – 1928.

Already Hedin had made four expeditions to Central Asia, explored the Himalayas, located the sources of the rivers Brahmaputra, Indus and Sutlej, mapped the “wandering lake” Lop Nur and discovered the remains of cities, grave sites and the Great Wall of China in the deserts of the Tarim Basin.

Hedin had visited Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, India, China, Russia and Japan, in an age where air travel was not common, trains were not everywhere and where the automobile had yet to be developed to a point of affordable utility.

Hedin would enter uncharted territory and literally put these places on the map, filling the “white spaces” up with his discoveries.

On the Sino-Swedish Expedition, Hedin, age 62, would be accompanied by a multinational team of 29 men, among them a humble bookkeeper who would serve as the Expedition’s logistics manager.

This bookkeeper, the son of a Konstanz pharmacist, would later write about his adventures in Mongolia (and his explorations of the Lake of Constance upon his return home), which would be published by a small Lengwil publisher.

Fritz Mühlenweg (1898 – 1961), educated as a chemist in Bielefeld and taking over his family’s business when his father died, left Konstanz for Berlin and began to work for Deutsche Luft Hansa.

On this day of 4 January 1927, Mühlenweg said his final farewells to his family in Konstanz and boarded a train bound for Berlin where the Expedition would begin, not knowing when or if he would ever return.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 25 May 2017

Through Mühlenweg’s youthful eyes – he was 29 at the start of the Expedition – and masterful writing, not only is the reader exposed firsthand to countries that, even today, few Westerners visit, but as well the reader is given the common man’s perspective of travelling with a legendary explorer.

I have been inspired by the writing of Fritz Mühlenweg, for he sought not just to see the places he visited but to understand what he saw, to see the romance in the commonplace, the exotic in the familiar and the familiar in the exotic.

Like Mühlenweg, I intend to expose my readers to both the exotic and familiar in the hopes that they too will see the wonder of the world as I do.

Men like Mühlenweg and Hedin have been mostly forgotten and our ability to traverse oceans and continents taken for granted.

Journeys that once took months now take only hours.

Journeys that once demanded much time and money are now expected to be quick and affordable.

We now move through and over landscapes that once meant something, that have now been reduced to simply spaces of transit, where everything is temporary and everyone is just passing through.

The wonder of the distinctiveness of a place has been replaced with a disdain for the local and an indifference to the uniqueness of every locality.

Human progress is now measured out in air miles, while communities find their common ground in cyberspace rather than terra firma.

We live in an age where we wish the world to be fully codified and collated, a world where ambiguity and ambivalence have been so sponged away that we know exactly and objectively where everything is and what it is called.

We want to arrive, instead of travel.

The case of Dr. Dao and United Airlines is a malaise particular to our modern age.

We conveniently forget that for every gain there is a loss.

Completeness removes the possibility of exploration, escape and hope.

We need the unnamed and the unexplored.

We need to examine our discarded sense of place and explore places both distant and at our doorstep.

For romance needs place and in a world “fully” discovered exploration must never stop.

The idea of exploration now needs to be reinvented.

We must not only see a place but as well observe it for its uniqueness and romance.

Let’s go on a journey – to the ends of the Earth and the other side of the street, as far or as close as we need to go to get away from the familiar and the routine prisons we have built for ourselves.

Whether they be good or bad, scary or wonderful, we need unruly and unexplored places that defy our expectations and make us question our preconceptions.

Love of place can never and should never be extinguished or sated.

Utopia (from the Greek for “no place”) is a happy land.

Sometimes the most fascinating places are often also the most disturbing, entrapping and appalling and often temporary.

In ten years’ time, most places will look very different.

Some will no longer exist, because nature is often horrible and life is transitory.

Love of place is not finding a place that is cute and cuddly, but rather love of place is a fierce love, a dark enchantment, that runs deep and demands our attention.

As Herman Melville wrote, in Moby Dick, when the first mate of the Pequod was describing his home:

“It is not down in any map.

True places never are.”

Sources:

Alastair Bonnett, Off the Map: Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands, Feral Places and What They Tell Us About the World

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Scandal in Bohemia

Albert M. Debrunner, Literaturführer Thurgau

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Fritz Mühlenweg, Drei Mal Mongolei

Wikipedia