Landschlacht, Switzerland, 26 May 2017

I read the news and I feel sometimes that all the media seems to report is bad news – news that angers or saddens me.

To be fair, it’s not the media’s fault completely…

Bad things happen in the world.

It is a terrible thing to admit, but nothing encourages us to remember Life more than a sudden threat to it or its sudden ending.

Recently Chris Cornell, former lead singer of the rock groups Audioslave and Soundgarden, died.

Suddenly I am reminded of two of his songs: Black Hole Sun and You Know My Name (the theme song of the Bond film Casino Royale), which play again and again like a skipping vinyl record in the jukebox of my mind.

On 22 May, a suicide bombing was carried out at Manchester Arena after a concert by American singer Ariana Grande.

The attacker was identified by police as Salman Ramadan Abedi, a 22-year-old of Libyan ancestry, who detonated a homemade explosive device as concertgoers were leaving the Arena.

23 people, including Abedi himself, were killed and approximately 120 were injured.

My ignorance of things Mancunian, Libyan and the music of Ariana Grande is made manifest and I find myself suddenly searching literature both hard copy and electronic to know more about these things in an attempt to understand an event that is incomprehensible.

Increased hits on search engines like Google show that I am not alone in this regard.

I am saddened by the loss of those so young whose only desire was to celebrate life’s rhythms.

I am saddened by the insanity that would drive a young man to commit such an atrocity.

I am angered that the Right will use this incident as a justification for their Islamophobia, making a cowed and frightened populace accept the usurpation of their freedom in the name of “guaranteed” security and create further hate and violence against others whose only “crime” is being of a different faith.

I am angered by those who would use religion as a justification for violence.

I am saddened that the tendency to label entire groups of people by the actions of a few still remains a constant impulse.

I am saddened that only those who think and act upon their consciences seek justice and compassion, while too many of us crave bloody revenge for this carnage committed against innocents.

I am saddened that those who have been chosen to lead us failed to protect us and may have been partially responsible for the violence visited upon us.

The lines between black and white, villain and hero, remain blurred.

Only the victims seem untainted of blame.

I, like many others, ask what could possibly be gained by anyone committing such an act.

A fearful populace brought to its knees who will seek to appease their attackers?

A spotlight thrown upon our vulnerability?

A desperate attack made to show the consequences of the actions made against others by those who lead us?

Events like Manchester also bring out the conspiracy theorists, whom are much harder to dismiss after a tragedy such as this.

The identification of the villains that inspired such violence is not so clear.

The child within me wishes for an obvious hero to combat such villainy, to save us as we cannot save ourselves.

A hero obvious who tells us: You know my name.

A hero like Bond.

James Bond.

A person with a license to kill, to mete out revenge disguised as justice.

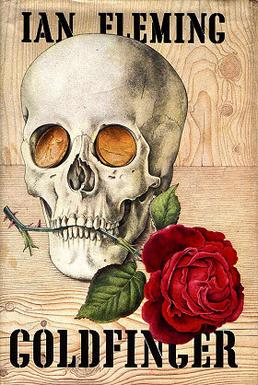

But is Ian Fleming’s fictional creation, immortalised in literature and film, truly a hero?

“James Bond lives in a nightmarish world where laws are written at the point of a gun, where coercion and rape are considered valour and murder is a funny trick.

Bond’s job is to guard the interests of the property class, and he is no better than the youths Hitler boasted he would bring up like wild beasts to be able to kill without thinking.”

(Yuri Zhukov, Pravda, 30 September 1965)

Harsh criticism, but was this journalist completely inaccurate?

“It was part of his profession to kill people.

He had never liked doing it and when he had to kill he did it as well as he knew how and forgot about it.

As a secret agent who held the rare double-O prefix – the license to kill in the Secret Service – it was his duty to be as cool about death as a surgeon.

If it happened, it happened.

Regret was unprofessional – worse, it was a death-watch beetle in the soul.”

(Ian Fleming, Goldfinger)

But, by this analysis, where do we draw the line between soldier and criminal?

Is every act justifiable if it is done for Queen and country, or in the name of religion?

Since 1953, Bond has been in the public consciousness from Fleming’s literature and since 1962 from a never-ending series of films.

We are reminded of Bond these days, not only for the death of Chris Connell, but for the death, the day after Manchester, of one of the seven actors who have played Bond in the 26 films starring this character (including the Woody Allen spoof of Casino Royale and the independent film Never Say Never Again), Roger Moore, who played the secret agent in seven feature films between 1973 and 1985.

Above: Sir Roger Moore (1927 – 2017)

Roger Moore died on 23 May 2017, age 89, in his home in Crans-Montana, Switzerland.

It is easy to think of Bond as a hero, for his villains are easy to identify.

And perhaps it is this dispatching of these villains that has somehow given the character its own immortality, regardless of the mortality of those who portray him on the silver screen.

Those who portray Bond have a terrible time afterwards of being identified only for the role as Bond.

Roger Moore, who played Bond more than any other actor, had this typecasting problem.

But unlike the villains Bond dispatched or the victims of real-life villains that strike down civilians, Moore did not end his days violently.

In his acting roles, Moore encountered his share of villains who would have delighted in his demise, yet, with the exception of one film, Moore’s character of the moment would survive any and all opposition.

(In the 1956 film Diane, Moore, in the role of French King Henri II, is killed in a jousting tournament.)

Moore’s characters were survivors, whether he was a highwayman against the armed might of a Duke (The Lion’s Thief, 1955) or a soldier in the Battle of Salamanca (The Miracle, 1959).

Moore played more roles than he is remembered for.

Moore played Sir William of Ivanhoe (1958 – 59), Silky Harris (The Alaskans, 1959 – 60), 14 Carat John (The Roaring Twenties, 1960 – 62), Beau Maverick (1960 – 61), Simon Templar (The Saint, 1962 – 69), Gary Fenn (Crossplot, 1969), Harold Pelham (The Man Who Haunted Himself, 1970), Lord Brett Sinclair (The Persuaders, 1971), Rod Slater (Gold, 1974), Sherlock Holmes (Sherlock Holmes in New York, 1976), Sebastian Oldsmith (Shout at the Devil, 1976), Shawn Fynn (The Wild Geese, 1978), Rufus Excalibar ffolkes (North Sea Hijack, 1979), Major Otto Hecht (Escape to Athena, 1979), Captain Gavin Stewart (The Sea Wolves, 1980),Seymour Goldfarb Jr. (Cannonball Run, 1981), Inspector Clouseau (The Curse of the Pink Panther, 1983), “Adam” (Bed and Breakfast, 1992), Lord Edgar Dobbs (The Quest, 1996), “The Chief” (Spice World, 1997) and Lloyd Faversham (Boat Trip, 2002).

These TV/movie roles, which can still be seen on websites like YouTube, are just some of the roles Moore played in a long and successful acting career.

Most of these roles had him play the hero.

Most of these roles had moments when the hero’s life was in grave danger.

As Ivanhoe, Moore suffered broken ribs and a battleaxe blow to his helmet.

In The Man Who Haunted Himself, Moore’s character briefly suffered clinical death after a car accident, but the movie’s director Basil Dearden would die for real in a car accident shortly thereafter.

In For Your Eyes Only, Moore, as Bond, would mourn the death of his wife, though in real life Moore would himself marry four times and was the father of three children.

Moore acted the hero in more than his screen appearances:

He was a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador (1991) and the voice of Father Christmas in a UNICEF cartoon (2004) and narrated a video for PETA protesting against the production and wholesale of foie gras (2008).

Moore’s greatest villain was poor health.

He nearly died from double pneumonia when he was five.

He was a long-term sufferer of kidney stones and needed to be hospitalised during the making of the Bond film Live and Let Die (1973) and again during the production of Bond film Moonraker (1979).

In 1993, Moore was diagnosed with prostrate cancer and underwent successful surgery for the disease.

He collapsed on stage while appearing on Broadway in 2003 and was fitted with a pacemaker to treat a potentially deadly slow heartbeat.

In 2012, Moore revealed he had been treated for skin cancer several times.

In 2013, he was diagnosed with diabetes.

His greatest villain, cancer, finally beat him on 23 May 2017.

Terrorism is a villainous act I shall never understand, because despite the headlines it garnishes it is only common to my own life indirectly in headlines.

Diseases, like cancer, on the other hand, are something I, like the common man, can relate to.

In my own life I have lost classmates, my mother and my two foster parents to this disease.

The obituary pages are filled with names of people whose lives were snuffed out by disease.

Still we tend to find death’s arrival after a long battle against a disease easier to cope with, for there is a sense of preparedness / readiness for the fatal end, as unwanted as it may be.

Deaths from accident or from incidents such as Manchester are much harder to accept, for we weren’t ready for our loved ones suddenly departing from our lives.

We are saddened by the deaths of entertainment legends, for we feel that their entertainment touched our lives, but their deaths remind us that, like us, they were mortal too.

But when we compare the death of Moore to the deaths of Manchester, we are left with a sense of unfairness.

Moore was 89 and had lived a full life.

The youngest victim of the Manchester bombing was 8.

Chris Cornell and Salman Abedi could be compared in that they both committed suicide because they were both psychologically unhealthy, but Cornell brought value to the world while Abedi took it away.

So, in these times living in the shadow of death, who or what is the greatest villain?

I believe the greatest villain is: apathy.

When someone dies, whether we knew them or not, it should matter to us.

And it shouldn’t take the death of someone for us to finally realise their value to us.

Don’t take your loved ones for granted.

Don’t take life and health for granted.

Manchester bothers me.

It was senseless and sad.

I refuse to hate.

Abedi was one man, but not all are cast in the same mold.

I refuse to be afraid.

I will live my life to the fullest, knowing that there is no way to predict when my final moment will arrive.

I hope I never forget to be grateful for the life I have and the people within it.

To those reading these words, please know that you are loved and have value.

And it is my hope, whether my life ends in tragic suddenness in some senseless attack or unexpected accident, or if I cling to life against the onslaught of age or disease, that I will be considered to have lived a life of value because I cared.

The greatest villain is apathy.

The best solution is love.

Sources:

James Bond: The Secret World of 007 (Dorling Kindersley)

The James Bond Encyclopedia (Dorling Kindersley)

Ian Fleming, Goldfinger

New York Times, 24 May 2017

Wikipedia