Landschlacht, Switzerland, 30 May 2017

Marriage ain’t easy.

“My successful marriage is built on mistakes.

It may be founded on love, trust and a shared sense of purpose, but it runs on cowardice, impatience, ill-advised remarks and low cunning.

But also: apologies, belated expressions of gratitude and frequent appeals for calm.

Every day is a lesson in what I am doing wrong.”

“Twenty years ago my wife and I embarked on a project so foolhardy, the prsopect of which seemed to us both so weary, stale and flat that even thinking about it made us shudder….

We simply agreed – we’ll get married – with the resigned determination of two people plotting to bury a body in the woods.”

(Guardian columnist Tim Dowling, How to Be a Husband)

Since autumn of 2016 I have been teaching technical English to a company in two locations: Amriswil in Canton Thurgau (the Canton where I reside) and in Neuhaus in Canton St. Gallen (the Canton where I mostly work) on the border of Canton Zürich.

From Neuhaus it is closer to visit Zürich than it is for me to return back to Landschlacht, so when my schedule as a freelance English teacher finds me with a free afternoon after the company class I take myself down to Zürich.

Zürich possesses many temptations for me: museums, bookshops, the Limmat River, the Lake of Zürich, restaurants and cafés.

And as well Zürich is where my wife resides from Sunday afternoon to Thursday evening every week.

And somewhere buried deep within our marriage contract in words only my wife can read is a clause that insists that I occasionally be nice and visit the Wife, aka my own personal She Who Must Be Obeyed.

Upon my arrival in Zürich yesterday a bus ride and a train journey later, I still had a few hours to myself with which I had the illusion of freedom to do what I wished before my wife, the doctor, finished work at her hospital.

I foolishly forgot that most museums in Switzerland are closed on Mondays and I had this explained to me politely by a security guard at the Swiss National Museum.

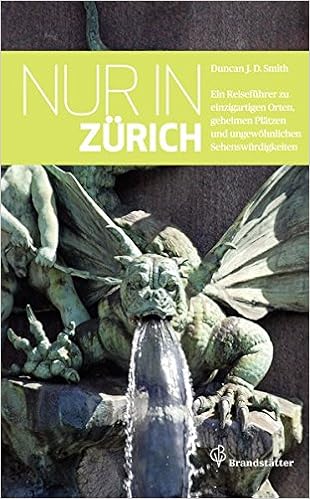

But like every bibliophile bookworm I never travel without literature for such situations, so with Duncan Smith’s Only in Zürich: A Guide to Unique Locations, Hidden Corners and Ununsual Objects in hand I once again set out to discover Zürich before meeting the wife who would then set my agenda for me.

All guidebooks to Zürich mention the fact that Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955) spent time in the city during the years leading up to the First World War.

Seven years and eight months (1896 – 1900 / 1909 – 1911 / 1912 – 1914 / 1919), to be precise, at six different addresses (Unionstrasse 4 / Klosbachstrasse 87 / Dolderstrasse 17 / Moussonstrasse 12 / Hofstrasse 116 / Hochstrasse 37).

Albert Einstein’s name is now synonymous with genius and his face has become a 20th century icon.

But what about his wife during this time, the gifted mathematician Mileva Maric (1875 – 1948)?

Few books mention her name and even fewer mention that she was buried in an unmarked grave in Zürich.

Albert Einstein arrived in Zürich in October 1896 to study at the Federal Polytechnic Institute (Eidgenössisches Polytechnikum) – today the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule)(ETH).

A wall plaque at Unionstrasse 4 marks one of the addresses where Albert lived during this period.

In the same year Mileva attended the same institution and the two soon became close friends.

Born to wealthy parents in Titel (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today a part of Serbia), Mileva was the first and favourite child of an ambitious pesant who had joined the army, married into money and then dedicated himself to making sure his brilliant daughter was able to prevail in the male world of mathematics and physics.

Mileva spent most of her childhood in Novi Sad and attended a variety of ever more demanding schools, at each of which she was at the top of her class, culminating when her father convinced the all-male Classical Gymnasium in Zagreb to let her enroll.

Above: St. Mark’s Church, Zagreb, Croatia

After graduating there with the top grades in physics and math, Mileva made her way to Zürich, where she became, just before she turned 21, the only woman in Albert’s section of the Polytechnic.

More than three years older than Albert, she was afflicted with a congenital hip dislocation that cause her to limp.

She was prone to bouts of tuberculosis and despondency.

Mileva was known for neither her books nor her personality.

One of her female friends in Zürich described her as “very smart and serious, small, delicate, brunette, ugly”.

But she had qualities that Albert, in his romantic scholar years, found attractive: a passion for math and science, a brooding depth and a beguiling soul.

Her deepset eyes had a haunting intensity, her face an enticing touch of melancholy.

Mileva would become, over time, Albert’s muse, partner, lover, wife, bête noire and antagonist and she would create an emotional field more powerful than that of anyone else in Albert’s life.

Mileva would alternately attract and repulse Albert, with a force so strong that a mere scientist, a mere man, like himself would never be able to fathom it.

Mileva and Albert met when they both entered the Polytechnic in October 1896, but their relationship took a while to develop.

They were nothing more than classmates that first academic year, but they did, however, decide to go hiking together in the summer of 1897.

“Frightened by the new feelings she was experiencing” because of Albert, Mileva decided to leave the Polytechnic temporarily and instead audit classes at Heidelberg University.

Mileva and Albert corresponded, her letters a mix of playfulness and seriousness, of lightheartednes and intensity, of intimacy and detachment.

Albert urged her to return to Zürich.

By February 1898, Mileva made up her mind to do so.

By April she was back, in a boarding house a few blocks from him and now they were a couple.

They shared books, intellectual enthusiasms, intimacies and access to each other’s apartments.

Friends were surprised that a sensuous and handsome man such as Albert, who could have almost any woman fall for him, would find himself with a short and plain Serbian who had a limp and exuded an air of melancholy.

But it is easy to see why Albert felt such an affinity for Mileva.

They were kindred spirits who perceived themselves as aloof scholars and outsiders, rebellious toward others’ expectations, intellectuals who sought as lovers someone who would also be a partner, a colleague and collaborator.

Above all else, Albert loved Mileva for her mind.

She would eventually gain the same score in physics as Albert.

In 1900 Albert presented his first published scientific paper to the Annalen der Physik, Europe’s leading physics journal, in which his unified physical law of relativity was already apparent.

In February 1901, Switzerland made Albert a citizen, but his parents insisted that he go with them to Milan and live there if he could not find work in Zürich.

Both in Zürich and in Milan, Albert was unsuccessful at attaining fulltime employment.

He spent most of 1901 juggling temporary teaching assignments and some tutoring.

Waiting for a decent post to materialise, Albert accepted a temporary post at a technical school in Winterthur for two months, filling in for a teacher on military leave, while Mileva remained in Zürich.

To make up for his absences, Albert proposed that they have a romantic getaway by Lake Como.

It was early Sunday morning, 5 May 1901, Albert waited for Mileva at the train station in the village of Como, “with open arms and a pounding heart”.

Mileva became pregnant by Albert.

Back in Zürich preparing to take her exams and hoping to go on to get a doctorate and become a physicist, she decided instead that she wanted Albert’s child – even though he was not yet ready or willing to marry her.

Perhaps as a consequence of her pregnancy or her dissatisfaction that Albert went on summer vacation with his parents and sister in the Alps instead of finding employment after Winterthur as he had promised her, Mileva failed her exams and gave up her dream of being a scientific scholar.

In the fall of 1901, Einstein took on a job as a tutor of a rich English schoolboy at a little private academy in Schaffhausen.

Mileva was eager to be with Albert, but her pregnancy made it impossible for them to be together in public, so she stayed at a small hotel in a neighbouring village.

Their relationship became strained, as Albert came only infrequently to visit her claiming he did not have the spare money.

Albert was desperately unhappy with his job in Schaffhausen so it was with some relief that his friend Marcel Grossmann told him that a job as a Bern patent office clerk would soon be his.

Albert moved to Bern in late January 1902, while Mileva returned to her parents’ home in Novi Sad to have their baby, a girl they called Lieserl.

Above: Petrovaradin Fortress, Novi Sad, Serbia

Though Albert wrote to Mileva asking about Lieserl, his love for the child was mainly abstract.

Albert did not tell his friends or family about his daughter and never once publicly speak of her or even acknowledge she existed.

Albert found a large room in Bern but Mileva would not be sharing it.

They were not married and an aspiring Swiss civil servant could not be seen cohabitating in such a way.

After a few months Mileva moved back to Zürich to wait for Albert to marry her as he had promised.

She did not bring Lieserl with her.

Albert and Lieserl never laid eyes on each other.

Lieserl was left back in Novi Sad with relatives and friends, so that Albert could maintain both his unencumbered lifestyle and respectability he needed to become a Swiss official.

The fate of Lieserl remains unknown.

Albert finally was rewarded the position on 16 June 1902.

Albert married Mileva at a tiny civil ceremony in Bern’s registry office on 6 January 1903.

Their son Hans Albert Einstein was born on 14 May 1904.

After gaining his doctorate in 1905 while working in the Swiss Patent Office, assessing the worth of electromagnetic devices, Albert wrote four groundbreaking articles: one concerning the photoelectric effect (for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921) and another containing his now famous mass-energy equivalence equation: E=mc squared.

In 1909 Albert and Mileva along with Hans moved back to Zürich, where Albert was made Associate Professor of Physics at the University of Zürich.

The Einstein family lived on the second floor at Moussonstrasse 12, where in 1910 their second son Eduard “Tete” Einstein was born.

In March 1911 the family relocated to Prague, where Albert became full professor at Charles University.

Einstein’s fame would lead him to wander around Europe giving speeches and basking in his renown, while Mileva stayed behind in Prague, a city she hated.

She brooded about not being part of his scientific circles that she had once struggled to join.

She became even more gloomy and depressed than her natural disposition had often led her to before.

So it was in this instability between them that Albert travelled alone to Berlin during the Easter holidays of 1912 and became reacquainted with a cousin, three years older, whom he had known as a child, Elsa.

Elsa Einstein had been married, divorced and now at age 36 was living with her two daughters in the same apartment buildings as her parents.

Albert was looking for new companionship and thus began secret romantic correspondence between them.

But after returning to Prague from Berlin, Albert began to develop qualms about his affair with his cousin.

What remained between Mileva and Albert was a feeling that living among the middle class German community in Prague had become wearisome, so they decided to return to the one place they thought could restore their relationship: Zürich.

In July 1912 the Einsteins returned once more to Zürich, where Albert took up a professorship at the Polytechnikum.

Life should have been glorious.

They were able to afford a modern six-room apartment with good views.

Above: Hofstrasse 116, Zurich

They were reunited with old friends.

But Mileva’s depression continued to deepen and and her health to decline.

After a year of silence, Elsa wrote to Albert.

So, when a few months later, Einstein received an offer to work in Berlin and be with Elsa, he was quite receptive.

This time they lived at Hofstrasse 116 where they remained until February 1914, when Albert became professor at Berlin’s Humboldt University.

Mileva was unhappy in Berlin and their marriage was dissolving.

She had become more depressed, dark and jealous.

He had become emotionally withdrawn.

Mileva became involved with Zagreb mathematics professor Vladimir Varicak who challenged Einstein’s theories.

In July Mileva moved out with the two boys into the house of her only friend Clara Haber and her husband the chemist Fritz.

Albert was prepared to take her back if she agreed to a brutal ultimatum of her duties and responsibilites.

He was prepared to live with Mileva again because he didn’t want to lose his children but it was out of the question that they would resume a friendly relationship but he aimed for a businesslike arrangement.

Mileva and the two boys left for Zürich on 29 July 1914.

She filled her time giving private lessons in mathematics, physics and piano playing.

Einstein returned to Zürich once more in January/February 1919 to lecture on his Theory of Relativity, staying at Hochstrasse 37.

That same year Albert divorced Mileva, giving her the proceeds from his Nobel Prize for her and their children’s support.

Mileva invested the money in three properties in Zürich, occupying one of them herself at Huttenstrasse 62, which has been identified by a memorial plaque since 2005.

Hans Einstein (1904 – 1973) would go on to study engineering at Zürich Polytechnic, get married, become a father to two sons and a daughter with his first wife Frieda, move to the United States becoming a professor of hydraulic engineering at Berkeley, remarry after Frieda’s death, father two more children.

Above: Hans Einstein’s final resting place, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA

Eduard Einstein (1910 – 1965) was smart and artistic.

Obsessed about Freud, Eduard hoped to be a psychiatrist, but he succumbed to his own schizophrenia and was institutionalised in Switzerland for much of the rest of his life at Zürich University Psychiatric Hospital.

Albert would go on to access even greater fame and award, eventually marrying his cousin Elsa.

And what of Mileva?

By the 1930s, the costs of treating Eduard for schizophrenia had overwhelmed her.

She was forced to sell her two investment properties and to transfer the rights to Huttenstrasse to Albert so as not to lose it.

Although he made regular payments to her Mileva died penniless in 1948.

She is buried in an unmarked grave in Zürich’s Nordheim Cemetery and mostly forgotten.

It was not until 2009 that a memorial gravestone was erected by the Serbian Diaspora Ministry, just inside the cemetery entrance on Käferholzstrasse.

I visited the places Mileva had known in reverse order from the cemetery to the first apartment she had shared with Albert.

And I found parallels with my own past…

I too had been left behind by my parents like Lieserl.

My mother lies buried in an unmarked grave, but unlike Mileva there is no society to put a plaque on Fort Lauderdale´s cemetery.

Like Mileva I have married a partner more successful professionally than myself, though unlike Mileva I have no illusions about my ever having the same aptitudes as my wife possesses, nor do I feel jealousy or resentment for her success.

Mileva’s partner required that she uproot her life several times to different locations in Zürich and to other cities like Prague and Berlin.

As my wife´s career is more stable than mine, I have moved with/for her from the Black Forest to the Rhine River border near Basel up to Osnabruck and then to this wee village by the Lake of Constance here in Switzerland.

I, like Mileva, am less attractive and outgoing than my spouse.

I, like Mileva, have my own quiet struggles with depression, but, so far, these bouts seem far less serious than those she suffered.

I came from work at the company in Neuhaus dressed for executive type work.

The temperature in Zürich yesterday was 32°, hot and humid.

Elves could have taken a bath in the pools of sweat gathered under my armpits.

Zürich like Rome is built upon hills so seeing the former abodes of the late Mrs. E demanded energy.

Happily if one gets thirsty in Zürich there is no need to find a café or a supermarket because it is quite acceptable to drink from a public fountain.

One never has to travel far to find a fountain because there are few cities with more fountains than Zürich, again compareable to Rome.

At last count, this city boasts a total of around twelve hundred fountains.

Above: The Napfbrunnen Fountain

With portable Starbucks cup in hand, I drank deeply and often.

Albert, with his great intelligence, achieved great fame and fortune.

Mileva, also possessing great intelligence, gave up fame and fortune for her family.

If Albert was a bad husband and father, history has no record in Mileva’s handwriting.

Her secrets and potential lie buried somewhere beneath the earth of the sprawling necropolis in the metropolis she chose to call home.

Daughter of Serbia, wife of a genius, mother to an abandoned daughter, sons becoming a wandering engineer and an ill schizophrenic, a victim of depression, genetics and passion, Mileva Maric Einstein was many things.

Now she is just a historical footnote lost in the shadows of an uncommunicative cemetery visited by a sweaty Canadian with too much time on his hands.

Mileva had her flaws and made her mistakes, but in the end analysis I am glad I found out about her.

I meet the wife later for a quick bite after her work and before her tango dance lesson and as I watch her speak with drama and passion, and as I consider both are good and bad times I can quietly smile and know that I have met my match, muse, partner, lover, wife, bête noire and antagonist.

I don’t know what the future holds, but I will say that she has made my past quite interesting.

Being a husband ain’t easy, but it sure isn’t boring.

Sources:

Tim Dowling, How to Be a Husband

Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe

Duncan J.D. Smith, Only in Zürich

Wikipedia