Landschlacht, Switzerland, 24 August 2017

Let me begin with an apology or two.

Much time has gone by since I started this blog and I feel like a negligent parent towards this activity and the few folks who read this blog.

Life has been busy and it has been complicated, but let´s try to recapture the muse and endeavour to be both consistent and passionate about my writing once again.

Truth be told, one never knows how much time one actually has.

So, for those who have missed this blog I apologise for taking so long to return back to this activity.

As well, as I no longer possess a personal home computer those who read this blog today will find that I am forced to return to writing without the inclusion of photographs at this time, but I hope to add them at a future date.

Musical genius Jimi Hendrix once asked:

“Are you experienced?”.

When we are reunited with old friends or family members we often ask them:

“How have you’ve been?”

“Where have you’ve been?”

Lately I have rediscovered a passion for Sherlock Holmes that has made me consider both how I, like many people, see but do not observe, and how the past is not as removed from the present as might be first thought.

(Regarding the world’s and my evolution into Holmesian fandom, see Canada Slim and the Bimetallic Question of this blog.)

Through my reading and teaching I am beginning to see travelling from perspectives I had not previously considered.

(For more about the benefits of travel, see The Great Adventure of this blog.)

London, England, 1 April 1894

“Holmes!”, I cried.

“Is it really you?

Can it indeed be that you are alive?

Is it possible that you succeeded in climbing out of that awful abyss?”

…”I had no serious difficulty in getting out of it, for the very simple reason that I never was in it…

…We (Holmes and Moriarty) tottered upon the brink of the (Reichenbach) Falls….

I slipped through his grip…and over he went….

The instant that the Professor had disappeared it struck me what a really extraordinary lucky chance Fate had placed in my way.

I knew that Moriarty was not the only man who had sworn my death.

There were at least three others whose desire for vegeance upon me would only be increased by the death of their leader.

They were all most dangerous men.

One or other would certainly get me.

On the other hand, if all the world was convinced that I was dead they would take liberties, these men.

They would lay themselves open, and sooner or later I could destroy them.

Then it would be time for me to announce that I was still in the land of the living….

Several times during the last three years I have taken up my pen to write to you, but always I feared lest your affectionate regard for me should tempt you to some indiscretion which would betray my secret….

You may have read of the remarkable explorations of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend…”

(Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Empty House)

(See Canada Slim and the Final Problem for details as to how Holmes and Moriarty – and many years later I – came to be at Reichenbach Falls, near Meiringen.)

Holmes escaped, and for the next three years, a period which Sherlockians call “the Great Hiatus”, Holmes travelled the world.

It is implied, in Doyle’s The Adventure of the Empty House, through Holmes’ mention of several places in Asia – all British imperial hotspots – that Holmes was working as a secret agent for the British government.

(James Bond of the Victorian age?)

Doyle gave the reader a wealth of intriguing hints about what Holmes was up to in those three years.

Despite the story’s historic Victorian setting, Doyle also wove into his fiction up-to-the-minute global issues into Holmes’ adventures.

Holmes said he posed as a Norwegian explorer named Sigerson.

Perhaps “Sigerson” was inspired by the real life Swedish explorer Sven Hedin?

Above: Sven Hedin in 1910

I am inspired to write about Hedin for a number of reasons:

I want to show that we are all a product of those who came before us, not just genetically, but emotionally and spiritually as well.

I want to show that even great men and women are often swept up in the current of their times and often make bad decisions with the best intentions.

Hedin inspired a local writer and poet who in turn has inspired me in my writing this past year.

Sven Anders Hedin (1865 – 1952) was a Swedish geographer, topographer, explorer, photographer, travel writer and illustrator of his own works.

During four expeditions to Central Asia, Hedin made the Transhimalaya known to the West and located the sources of the Brahmaputra, Indus and Sutlej Rivers.

Hedin also mapped Lake Lop Nur and the remains of cities, grave sites and the Great Wall of China in the deserts of the Tarim Basin.

In his book From Pole to Pole, Hedin describes a journey through Asia and Europe between the late 1880s and the early 1900s, visited Istanbul, the Caucasus, India, China, Asiatic Russia and Japan.

On some levels I can relate to Hedin.

At 15 years of age, Stockholm resident Hedin witnessed the triumphal return of the Arctic Explorer Adolf Eric Nordenskiold after his first navigation of the Northern Sea Route.

Hedin describes the experience in his book My Life as an Explorer:

“On 24 April 1880, the steamer Vega sailed into Stockholm harbour.

The entire city was illuminated.

The buildings around the harbour glowed in the light of innumerable lamps and torches.

Gas flames depicted the constellations of Vega on the castle.

Amidst this sea of light the famous ship glided into the harbour.

I was standing on the Sondermalm heights with my parents and siblings, from which we had a great view.

I was gripped by great nervous tension.

I will remember this day until I die, as it was decisive for my future.

Thunderous jubliation resounded from quays, streets, windows and rooftops.

“That is how I want to return home some day.”, I thought to myself.

I was 15 as well on 14 May 1980 when a distant relative sent me the birthday present of a three-year subscription to National Geographic.

Seeing pictures of faraway places with strange-sounding names, reading of the exploits of a young man sailing around the world and another walking across the USA, and seeing that there still remained a world of adventure and experience beyond the dairy farms and ploughrow fields, beyond Mount Maple and the busy highway outside my yard, beyond the isolation of the tiny parish of St. Philippe d’Argenteuil de la Paroisse de St. Jerusalem, I began to plot my escape.

Especially motivating was the story of Peter Jenkins who left his house on the East Coast of America, walked down to New Orleans and then over to the West Coast.

Like Patrick Fermor who walked from England to Istanbul, or Laurie Lee who walked from the security of the Cotswolds to Spain, Jenkins followed the call of the road not knowing where it would lead beyond the notion of “Here’s a point on the map. I’ll go here.”

Above: Patrick Fermor, 1966

I could, if brave enough, throw a backpack on my shoulders and simply go.

Only later in life would I begin to realise that fame such as that achieved by Hedin and his hero Nordenskiold, or recognition the likes of Jenkins, Fermor or Lee requires an organised campaign almost akin to Hannibal crossing the Alps.

In my own adventures I realised that wide renown was never as important to me as the actual experience of travelling.

Chances are strong that I shall not long be remembered after these words are read, for I set no new records, made little publicity and have been content to simply write down my feelings and observations that someone might read and enjoy.

But without restless folks like Hedin, Jenkins, Fermor and Lee, I might have remained feeling limited to my origins and would have settled for a life of quiet desperation.

Without the accounts of folks like these I might not have been inspired to try my hand at writing.

And though there are those who cannot see beyond the 50-something tall, slightly overweight, balding barista and freelance teacher, I still see potential yet untapped.

I hope.

Hedin learned to seize opportunity where he could.

After graduating from high school in 1885, Hedin accepted an offer to accompany the student Erhard Sandgren as his private tutor to Baku, Azerbaijan, where Erhard’s father was working as an engineer in the oil fields of Robert Nobel.

Above: Maiden Tower, Baku, Azerbaijan

While in Baku, Hedin began to study languages: Latin, French, German, Persian, Russian, English and Tatar.

He would later learn several Persian dialects as well as Turkish, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Tibetan and some Chinese.

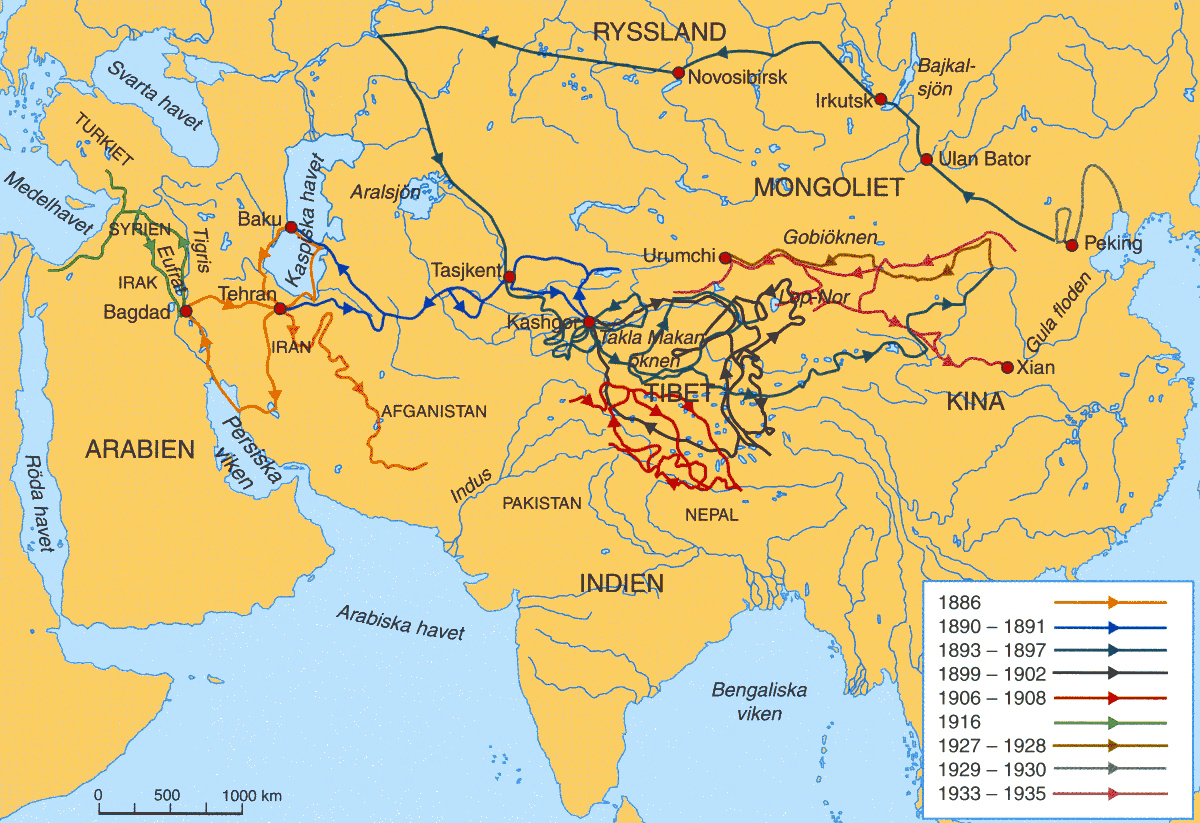

In 1886, Hedin left Baku for Iran, travelling by paddle steamer over the Caspian Sea, riding through the Alborz Range to Teheran, Esfahan, Shiraz and the harbour city of Bushehr.

Hedin then took a ship up the Tigris River to Baghdad, returning to Tehran via Kermanshah and then travelling through the Caucasus and over the Black Sea to Istanbul, then finally returning to Sweden.

He then published a book about these travels entitled Through Persia, Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

Hedin then returned to his studies, learning geology, mineralogy, zoology and Latin in Stockholm, Uppsala and Berlin.

In 1890 Hedin acted as interpreter and vice-consul to a Swedish legation to Iran, where he would meet and accompany the Shah of Iran on a climb up Mount Damavand.

He then travelled the Silk Road via the cities of Mashhad, Ashgabat, Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent and Kashgar to the western outskirts of the Taklamakan Desert.

On the trip home, Hedin visited the grave of the Russian Asian scholar Nikolai Przhevalsky in Karakol on the shore of Lake Issyk Kul.

Hedin published the books King Oscar’s Legation to the Shah of Persia in 1890 and Through Khorasan and Turkestan about this journey.

After completing his doctorate in Halle, Hedin was encouraged to become throughly acquainted with all branches of geographic science and its methodologies so that he could become a fully qualified explorer, but:

“I was not up to this challenge.

I had gotten out onto the wild routes of Asia too early.

I had perceived too much of the splendour and magnificence of the Orient, the silence of the deserts and the loneliness of long journeys.

I could not get used to the idea of spending a long period of time back in school.”

Hedin went against what remains very European thinking…the idea that a person cannot pursue his dreams without qualifications.

Hedin still remained dedicated to become an explorer.

He was attracted to the idea of travelling to the last mysterious portions of Asia and filling in the gaps by mapping areas completely unknown in Europe.

From 1893 to 1897, Hedin left Stockholm, travelling via St. Petersburg and Tashkent to the Pamir Mountains.

Several attempts to climb the 7,546-metre/24,757-foot high Muztagata Glacier were unsuccessful.

Hedin then tried to cross the Taklamakan Desert, but his water supply was insufficient resulting in the deaths of seven camels and two escorts.

(In 2000, Bruno Baumann travelled Hedin’s route and concluded that it is impossible for a camel caravan travelling in the springtime to carry enough water for both camels and travellers.)

Hedin’s ruthless behaviour and obsessive urge to complete his research would earn him massive criticism.

After a stopover in Kashgar, Hedin visited the 1,500-year-old abandoned cities of Dandan Oilik and Kara Dung, northeast of Khotan in the Taklamakan Desert.

He then discovered Lake Bosten, one of the largest inland bodies of water in Central Asia.

Hedin mapped Lake Kara-Koshun then travelled across northern Tibet and China to Beijing and returned to Stockholm via Mongolia and Russia.

From 1899 to 1902, Hedin navigated the Yarkand, Tarim and Kaidu Rivers and found the Lake of Lop Nur, where he discovered the ruins of the lost city of Loulan.

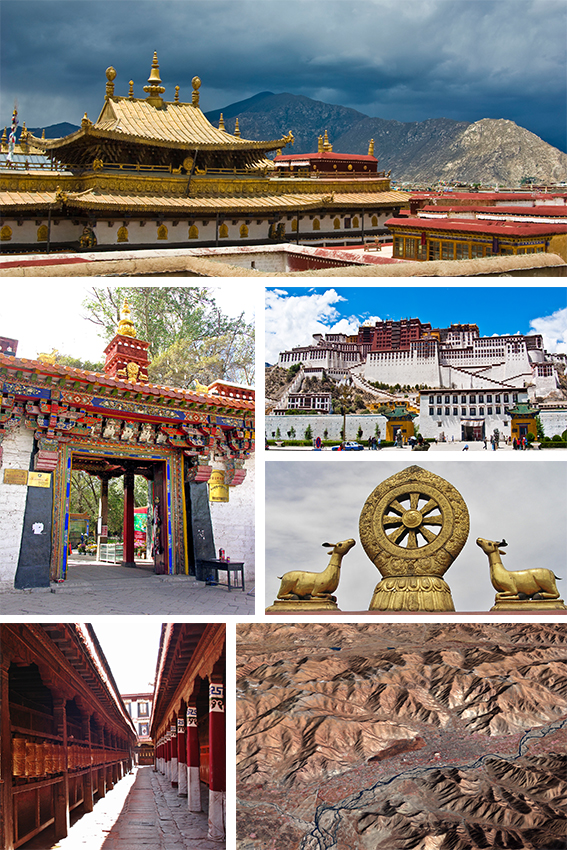

Above: Scenes of Lhasa

He attempted to reach the forbidden city of Lhasa and explored India.

This expedition resulted in 1,149 pages of maps of newly discovered lands.

Between 1905 and 1908, Hedin investigated the Central Iranian desert basins, the western highlands of Tibet and the Transhimalaya.

Hedin visited the Dalai Lama in the cloistered city of Tashilhunpo in Shigatse.

Hedin was the first European to reach the Kailash Region, including sacred Lake Manasarovar and Mount Kailash – the midpoint of the Earth according to Buddhist and Hindu mythology.

The most important goal of the expedition was the search for the sources of the Indus and the Brahmaputra Rivers, both of which Hedin found.

From India, he returned via Japan and Russia to Stockholm.

In 1923, Hedin travelled to Beijing via the USA – where he visited the Grand Canyon – and Japan.

He then travelled with Frans August Larson (aka “the Duke of Mongolia”) in a Dodge automobile from Beijing through Mongolia via Ulaanbataar to Ulan-Ude and from there across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow.

Between 1927 (Hedin was already 65.) and 1935, Hedin led the International Sino-Swedish Expedition which investigated the meteorological, topographic and prehistoric situation in Mongolia, the Gobi Desert and Xinjiang.

Above: Envelope of a letter from Hedin to his sister Alma with Chinese stamps issued on the occasion of the Sino-Swedish Expedition

Hedin was joined by eight Swedes, a Dane, ten Chinese, thirteen Germans (including local young man Fritz Mühlenweg), 66 camel riders and 30 soldiers.

Above: Fritz Mühlenweg in later years

Hedin described the Expedition as a peripatetic university in which the participating scientists worked almost independently, while he – like a local manager – negotiated with local authorities, made decisions, organised whatever was necessary, raised funds and recorded the route followed.

He gave these archaeologists, astronomers, botanists, geographers, geologists, meteorologists and zoologists the opportunity to participate in the Expedition while carrying out research in their areas of speciality.

Hedin was a prolific writer:

His publications amounted to some 30,000 pages, with 2,500 drawings and watercolors, films and many photographs.

And this doesn´t include his 25 volumes of travel and expedition notes and 145 volumes of diaries he regularly maintained between 1930 and 1952, totalling 8,257 pages.

Hedin´s expeditions laid the foundations for a precise mapping of Central Asia.

He was one of the first European scientific explorers to employ indigenous scientists and research assistants on his expeditions.

Even though Hedin was a man of small stature, with a bookish, bespectacled appearance, Hedin nevertheless proved himself a determined explorer, surviving several close brushes with death from hostile forces and the elements over his long career.

His scientific documentation and popular travelogues, illustrated with his own photographs, paintings and drawings, his adventure stories for young readers and his lecture tours abroad made him world famous.

(In the months after his return from the Sino-Swedish Expedition, Hedin held 111 lectures in 91 German cities as well as 19 lectures in other countries.

To accomplish this lecture tour, Hedin covered a stretch of road as long as the Equator, 23,000 km/14,000 miles by train and 17,000 km/11,000 miles by car – in a time period of only five months.)

With all his travels, Hedin never married and had no children.

Hedin remains a controversial figure and not only because of his fatal adventures in the Taklamakan Desert.

Even though Hedin would gain fame and glory for his accomplishments as an explorer and would be ceremoniously honoured by King and Shah, Czar and Kaiser, Viceroy and Emperor, Pope and President, Chancellor and Dictator, Hedin was often criticised for his political leanings.

Some historians claim that Hedin was a child of the 19th century unable and unwilling to align his thinking and actions according to the demands of the 20th century.

Others criticised Hedin for making his exclusive knowledge of Central Asia not only available to the Swedish government but to any government, including those of Chiang Kai-Shek and Adolf Hitler.

Hedin was a monarchist and was against democracy in Sweden, believing that democracy weakened national defence and military preparedness.

Hedin felt Russia was the greatest danger to Europe and Asia with its desire to dominate and control territories outside its borders, and so felt that Germany was Europe´s best defence against Russian expansionism.

Hedin viewed World War I as a struggle of the German race against Russia and particularly admired German Kaiser Wilhelm II, whom he even visited in his exile in the Netherlands.

Hedin´s conservative and pro-German views eventually translated into sympathy for the Third Reich.

Hedin saw Hitler´s rise to power as a revival of German fortunes and welcomed its challenge against Soviet Communism.

Hedin supported the Nazis in his journalistic activities.

Although Hedin was not a National Socialist (Nazi), his incredible naivete and gullibility as well as his hope that Nazi Germany would protect Scandinavia from invasion by the Soviet Union, brought Hedin in dangerous proximity to Nazis who exploited him as an author, destroying his reputation and put him into social and scientific isolation.

Even after the collapse of the Third Reich, Hedin did not regret his collaboration with the Nazis, because this cooperation had made it possible for Hedin to rescue numerous Nazi victims from execution or death in extermination camps.

Much of what happened in the early days of Nazi rule had his approval, but Hedin was not an entirely uncritical supporter of the Nazis.

He attempted to convince the German government to relent in its antireligious and antisemetic campaigns.

Hedin requested pardons for people condemned to death and for mercy, release and permission to leave the country for people interned in prisons or concentration camps.

Hedin tried to save over 100 deported Jews and Norwegians as well as acted on behalf of Norwegian activists.

Hedin died at Stockholm in 1952.

Among the many honours paid to Hedin by numerous countries, a glacier (the Sven Hedin Glacier), a lunar crater, a species of flower, a species of beetle and a species of butterfly, fossil discoveries as well as streets and squares have been named after him.

There is a permanent exhibition on Hedin and his expeditions in the Stockholm Ethnographic Museum and a memorial plaque dedicated to Hedin can be found in the Adolf Frederick Church.

In Swedish, it reads:

“Asia´s unknown expanses were his world. Sweden remained his home.”

Is it any wonder that folks like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Fritz Mühlenweg were so impressed by this little Swede who opened up the big world?

I wonder…

Would Hedin have explored and written so much had he been blessed with a wife and children?

Modern explorers like the aforementioned Peter Jenkins and train travelogue author Paul Theroux sacrificed their marriages to their wanderlust.

Above: Paul Theroux, 2008

I wonder…

Were I not married or if I had never married would I still be travelling?

Would I have been a more prolific writer had I explored roads and paths not taken?

Fritz Mühlenweg, after his travels in Mongolia, would meet and marry a woman and raise a family and beat back his wanderlust by writing and painting the Lake of Constance region he loved.

Like Mühlenweg, I too have travelled a wee bit in my younger days and married and settled by the Lake of Constance.

Is the cure for my own wanderlust that burns within my blood to write about where I have settled?

I wonder…

Sources: Wikipedia / Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of the Empty House”