Landschlacht, Switzerland, 14 September 2017

“History is little more than the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind.” (Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

Above: Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794)

“I believe that are monsters born in the world to human parents.

Some you can see.

And just as there are physical monsters, can there not be mental or psychic monsters born?

The face and body may be perfect, but if a twisted gene or a malformed egg can produce physical monsters, may not the same process produce a malformed soul?

Monsters are variations from the accepted normal to a greater or a less degree.

As a child may be born without an arm, so one may be born without kindness or the potential of conscience.” (John Steinbeck, East of Eden)

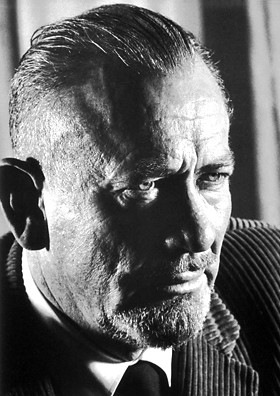

Above: John Steinbeck (1902 – 1968)

History is a chronicle of the most evil characters and wicked crimes: six million Jews killed in the Holocaust, the murdered millions of the Congo, Rwanda, the Armenians, the Hereros of Namibia, the East Timorese, and many many others.

In naming and chronicling their murderers, we defy the wishes of the killers who hoped that posterity would forget their crimes.

“Who now remembers the Armenians?”, mused Hitler, ordering the Final Solution.

Above: Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945)

His comment shows why history matters, because Hitler found encouragement and solace in the forgotten Armenian massacres.

Past and present are closely linked.

“No one remembers the boyars killed by Ivan the Terrible”, said Stalin, ordering the Great Terror.

Above: Joseph Vissariorovich Stalin (1878 – 1953)

In the colassally audacious, incredible scale of these crimes, these monsters found a diabolical sanctuary from comprehension and judgement.

“One death is a tragedy, but a million is a statistic.”, said Stalin.

The most disgusting of these crimes were committed in the 20th century when the corrosive all-embracing utopianism of insane ideologies dovetailed with modern technology and pervasive state power to make killing easier, quicker and possible on a gargantuan scale.

(Simon Sebag Montefiore, Monsters: History´s Most Evil Men and Women)

On my summer vacation with my wife, on our very first day of the vacation, we encountered the memory of such a monster.

Lake Como / Lago Como, Italy / Italia, 31 July 2017

Perhaps the problems of contemporary Italy are too disturbing and too difficult to understand.

Local political events have always seemed mysterious and negligible to the foreign visitor or resident expatriate.

Tourists don´t want to be reminded of a place´s dark heart or imperfect history.

The Italy for foreigners is mainly an imaginary country, for we often don´t really pay attention to or see clearly the Italy that Italians see.

We know too few natives and those we see are seen through a sunny haze too bright to understand Italians and their problems.

We meet hotel concierges, waiters, shopkeepers, and tourist information providers, but we may never know the great mass of the Italians for we are as ignorant as children in these matters.

But no matter where you go, where humans are, one can find the desperate struggles for money and power if one takes the time and looks beyond the surface impressions.

This universal struggle demands its daily sacrifices, its regular victims.

Even when violent death is not lurking in the shadows, when things look pleasant and peaceful and life seems secure, prosperous and easy, competition at every level and in every field is intense, ruthless and without pause.

Fortune is notoriously fickle and history restless.

The day had begun well.

We drove across the Swiss border into Italy and were immediately charmed by the Italian province of Lombardy, for though Italy is about as large as California the inhabitants are incredibly numerous – over 50 million of them – one does not get the feeling of crowdedness in the Italian town first encountered over the Passo Spluga: Montespluga.

Part of Montespluga´s isolation is of course related to the Splügen Pass being closed in winter months and generally avoided throughout the year by those craving speed who take the San Bernardino road tunnel, opened since 1967, to the west.

There is not much about Montespluga to warrant the praises of most guidebooks.

After all the village consists of only three main streets (Via Dogana, Via Ferre, Via Val Longa), some small shops, a couple of hotels and restaurants.

But the plus side of this isolation lends both a warm welcome to the traveller determined to visit and an amazingly beautiful and tranquil landscape.

Here wild ponies graze in the fields, just outside the pizzaria windows, calm but vigilant when humans venture the paths that bisect their territory.

Through here the fit and adventureous hiker can follow the 65-kilometre Via Spluga from Thusis, Switzerland to Chiavenna, Italy, totally immersed in the splendour of nature, with some of the path the remnants of old Roman roads.

After a hardy lunch and a stroll in the pasture of ponies, we drove along the Reservoir, the Lago di Montespluga, through the town of Campodolcino (home to the poet Giosue Carducci and writer/journalist Don Abramo Levi, and a centre for winter skiing) and the village of San Giacomo e Filippo to the town of Chivenna.

Chiavenna, picturesquely on the right bank of the river Mera, 16 km north of Lago Como, formerly the Roman town Clavenna, is crowned by a ruined castle.

It was in this castle in October 1154 that the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122 – 1190) met with his cousin Henry “the Lion” (1129 – 1195) and fell on his knees begging Henry´s aid against the cities of the Lombard League.

After all Frederick only wanted to impress the Pope and the Italians with his power, to plunder and raze city-states, to reward friends and allies and destroy enemies.

Isn´t that what rulers are supposed to do?

In the town is a statue of Peter de Salis (1738 – 1807), an Anglo-Swiss who resisted Napoleon, and was an extremely popular governor of the commune (1771 – 1773 / 1781 – 1783).

We did not linger in Chiavenna for my wife´s guidebook recommended a side trip to the Cascata dell´ Acquafraggia waterfalls, first recorded by Leonardo da Vinci in 1495 in his Codex Atlanticus.

This stream which flows from the Pizzo del Lago near the Swiss border then joins the Mera River at Borgonuovo, 5 km east of Chiavenna, imposingly descends into a series of waterfalls 170 metres high.

But the Cascata don´t feel like a tourist attraction as much as the local family picnic area and playground.

Somehow the waterfalls reminded me of the kind of setting that the original series of Star Trek might have used to film an alien paradise world.

Russian poet Apollon Nicolayevich Maykov once wrote enthusiatically: “Under that fiery sun, in the roar of a waterfall, inebriated you said to me: Here we can die together, the two of us.”

Above: Apollon Nicolayevich Maykov (1821 – 1897)

We lingered bathing our feet in the stream that collected below the cascade.

We lingered too long.

Beautiful scenery, the stage setting for a peaceful dream, is suddenly cluttered by thousands upon thousands of men, women and children, Vespas and noxious automobiles, bright lights and intense noise, construction, constriction and complication.

For the western shore of Lago Como from Sorico all the way down to Como was crowded, traffic insane, a rush hour when commuters were unable to rush, bumper to bumper with no relief.

And it was in this spirit of impatience and annoyance that we discovered a monster.

Between the towns of Gravedona and Musso, 40 km/25 miles northeast of the city of Como, one can find the Comune Dongo, with its two main sights: the Palazzo del Vescovo (Bishop´s Palace) – home to the International Piano Academy where seven pianists, chosen annually from a worldwide field of over 1,000 applicants, including many prizewinners, have the opportunity of studying for a week with piano virtusos – and the Palazzo Manzi – the town administrative centre and the Museo della Fine della Guerra (Museum of the End of the War) with displays of partisan activity in Dongo and the north Lake Como area from the time of the Italian armistice in September 1943 up to the end of the Second World War in 1945.

Above: The Palazzo Manzi

Why is this museum in this town?

Because it was in Dongo, on 27 April 1945, that Il Duce, Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945), Prime Minister of Italy (1922 – 1925), Dictator of Italy (1925 – 1943), Dictator of the Italian Social Republic (1943 – 1945) and the founder of fascism, was, along with other fascists, fleeing from Milano towards the Swiss border, captured by Urbano Lazzaro and other partisans and held prisoner within the walls of the Palazzo Manzi for most of the night before his last day alive.

Ruthlessly suppressing any form of dissent in Italy, Mussolini, a greedy colonialist with delusions of creating a post-modern new Roman Empire, was directly responsible for the deaths of over 30,000 Ethiopians in his infamous Abyssinian campaign, as well as being complicit, through his alliance with Adolf Hitler, in the atrocities of Nazi Germany.

Mussolini was born on 29 July 1883 in Dovia di Predappio, as the son of a blacksmith and a schoolteacher, a profession he tried in 1901 but swiftly abandoned.

Above: Birthplace of Mussolini, now a museum

In 1902 Mussolini fled to Switzerland to avoid conscription.

In Lausanne, Mussolini tried, once or twice, actually to become a member of the working class by getting a job as a labourer but discovered he didn´t like hard work.

He much preferred revolutionary literature and talking.

Mussolini preached indiscriminate violence to his Italian countrymen who were so impressed they elected him secretary of the bricklayers trade union.

Mussolini sought the company of other revolutionaries who were at the time mostly Russians who called him Benitushka.

Mussolini called himself an “apostle of violence”.

He never washed, seldom shaved and lived where he could.

The Swiss police watched him and arrested him several times for vagrancy.

Mussolini watched himself playing the great role he was inventing as he went along, hammering at it with gusto.

No earnest revolutionary in Switzerland at the time was as visibly frightening as he was.

Certainly not Lenin who resembled a little professor.

Above: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, aka Lenin (1870 – 1924)

In his twenties, following in the footsteps of his father, Mussolini became a committed socialist, editing a newspaper called La Lotta di Classe (the class struggle), before, in 1910, becoming secretary of the local socialist Party in Forli, where he edited the paper Avanti! (forward!).

Mussolini also wrote an unsuccessful novel called The Cardinal´s Mistress.

Increasingly known to the authorities for inciting disorder, Mussolini was imprisoned in 1911 for producing pacifist propaganda after Italy declared war on Turkey.

Mussolini initially opposed Italy´s entry in the First World War, but, believing a major conflict would overthrow capitalism, he changed his mind, which saw him expelled from the Socialist Party.

Mussolini became fascinated with militarism, founding a new paper, Il Popolo d’Italia, as well as the pro-war group Fasci d’Azione Rivoluzionaria (the Revolutionary Fascist Party).

His own military service was cut short in 1917 following injuries sustained in a grenade explosion in training.

Mussolini was now a confirmed anti-socialist, convinced that only authoritarian government could overcome the economic and social problems endemic in postwar Italy, as violent street gangs (including his own Fascisti) battled for supremacy.

In March 1919, the first Fascist movement in Europe cristallised under his leadership.

His black-shirted supporters, in stark contrast to the flailing liberal governments of the time, successfully broke up industrial strikes and dispersed socialists from the streets.

Though Mussolini was defeated in the 1919 elections, he was elected to Parliament in 1921, along with 34 other fascists.

In October 1922, after hostility between left wing and right wing groups had escalated into near anarchy, Mussolini – with thousands of his Blackshirts – staged the March on Rome, presenting himself as the only man who could restore order.

Above: The March on Rome, 28 October 1922

In desperation, King Vittorio Emanuele III asked Mussolini to form a government.

Above: Vittorio Emanuele III (1869 – 1947), King of Italy

Mussolini’s regime was built on fear.

By 1926, Mussolini had dismantled parliamentary democracy and stamped his personal authority on every aspect of government.

By 1928, Italy had become a one-party police state.

In 1935, seeking to make his dreams of Mediterranean domination and a North African empire, Mussolini ordered the invasion of Ethiopia.

Above: Italian artillery, Tembien, Ethiopia, 1936

His use of mustard gas there (300 to 500 tonnes), followed by the vicious suppression of a rebellion against Italian rule, lead the League of Nations (the precursor to today´s United Nations) to impose sanctions on Italy.

Above: Flag of the League of Nations, HQ in Geneva (1920 – 1945)

Increasingly isolated, Mussolini left the League and allied himself with Hitler in 1937, emulating the Führer in pushing through a series of anti-Semitic laws.

It soon became clear, however, that Mussolini was the minor partner in the relationship, Hitler failing to consult him on almost all military decisions.

After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Mussolini ordered the invasion (7 – 12 April 1939) of neighbouring Albania, his troops easily brushing aside the tiny army of King Zog.

Above: Italian troops in Albania

In May 1939, Hitler and Mussolini declared a Pact of Steel, pledging to support the other in the event of war.

Italy did not enter the Second World War until the fall of France in June 1940, when it looked like Germany was on course for a quick victory, but the Italian war was a total disaster.

For all the puffed-up militarism of his regime, Mussolini´s army was disastrously unprepared for war on this scale.

Following the Allied arrival on the shores of Sicily in June 1943, Mussolini´s fascist followers abandoned him and had him arrested, only for German commandos to rescue him from imprisonment and place him at the head of a puppet protectorate, the Italian Social Republic based at the town of Salo near Lago Garda in the north of Italy.

Above: Flag of the Italian Social Republic (1943 – 1945)

By 1944, the Salo Republic was threatened not only by the Allies advancing from the south bit also internally by Italian anti-fascist partisans in a brutal conflict that was to become known as the Italian Civil War.

Slowly fighting their way up the Italian peninsula, the Allies took Roma and Firenze in the summer of 1944 and later that year began advancing into northern Italy.

With the final collapse of the German army´s Gothic Line in April 1945, total defeat for the Salo Republic was imminent.

From mid-April 1945, Mussolini based himself in Milano, taking up residence in the city´s Prefecture.

At the end of the month, the partisan leadership, the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (CLNAI) declared a general uprising in the main northern cities as the German forces retreated.

With the CLNAI´s assumption of control in Milano and the German army about to surrender, Mussolini fled the city on 25 April and attempted to escape north to Switzerland.

Above: Mussolini abandoning the Prefecture in Milan, 25 April 1945.

This photo is believed the last photo of Mussolini alive.

On the same day as Mussolini left Milano, the CNLAI declared:

“The members of the fascist government and those fascist leaders who are guilty of having suppressed constitutional guarantee, destroyed the people´s freedoms, created the fascist regime, compromised and betrayed the country, bringing it to the current catastrophe are to be punished with the penalty of death.”

(CLNAI Decree, 25 April 1945)

On 27 April 1945, Mussolini and his mistress Claretta Petacci, together with other fascist leaders, were travelling in a German convoy near the village of Dongo.

Above: Claretta Petacci (1912 – 1945)

A group of local communist Partisans led by Pier Luigi Bellini delle Stelle and Urbano Lazzaro attacked the convoy and forced it to halt.

The Partisans recognised one Italian fascist leader in the convoy, but not Mussolini at this stage, and made the Germans hand over all the Italians in Exchange for allowing the Germans to proceed.

Eventually Mussolini was discovered slumped in one of the convoy vehicles.

Lazzaro later said:

“His face was like wax and his stare glassy, but somehow blind.

I read utter exhaustion, but not fear.

Mussolini seemed completely lacking in will, spiritually dead.”

The partisans arrested Mussolini and took him to Dongo, where he spent part of the night in the local barracks in the Palazzo Manzi.

In all, over 50 Fascist leaders and their families were found in the convoy and arrested by the partisans.

Aside from Mussolini and Petacci, 16 of the most prominent of them would be summarily shot in Dongo the following day and a further 10 would be killed over two successive nights.

Fighting was still going on in the area around Dongo.

Fearing that Mussolini and Petacci would be rescued by fascist supporters, the partisans drove them, in the middle of the night, to a nearby farm of a peasant family named De Maria.

They believed this would be a safe place to hold them.

Mussolini and Petacci spent the rest of the night and most of the following day there.

On the evening of Mussolini´s capture, Sandro Pertini, the socialist partisan leader in northern Italy, announced on Radio Milano:

“The head of this association of delinquents, Mussolini, while yellow with rancour and fear and trying to cross the Swiss frontier, has been arrested.

He must be handed over to a tribunal of the people so it can judge him quickly.

We want this, even though we think an executive platoon is too much of an honour for this man.

He would deserve to be killed like a mangy dog.”

“Everyone dies the death that corresponds to his character.”

(Benito Mussolini, 1932)

Luigi Longo, a senior communist in Milano, instructed a communist partisan of the General Command, Walter Audisio, to go immediately to Dongo…

Above: Walter Audisio (1909 – 1973)

“Go and shoot him (Mussolini)”.

Longo asked another partisan, Aldo Lampredi, to go as well because Longo thought Audisio was “impudent, too inflexible and rash”.

Audisio and Lampredi left Milano for Dongo early on the morning of 28 April to carry out Longo´s orders.

On arrival in Dongo, they met Bellini delle Stelle, the local partisan commander, to arrange for Mussolini to be handed over to them.

In the afternoon, Audisio, with other partisans, drove to the De Maria farmhouse to collect Mussolini and Petacci.

After they were picked up, they drove a short distance to the village of Giulino de Mezzegra.

So did we 72 years and 64 days later.

At the entrance of the Villa Belmonte on the narrow road XXIV maggio, Mussolini and Petacci were told to get out and stand by the Villa´s wall.

Audisio then shot them at 1610 hours, with a submachine gun.

Above: The French-made MAS-38 submachine gun, used by Walter Audisio to shoot Benito Mussolini, National Historical Museum, Tirane, Albania

My wife was tired and impatiently wanting to get to Como and our B & B.

I took photos of the execution site.

We drove on.

In the evening of 28 April 1945, the bodies of Mussolini, Petacci and the other executed fascists were loaded onto a van and trucked south to Milano.

On arriving in the city in the early hours of 29 April, the bodies were dumped on the ground in the Piazzale Loreto, a suburban square near the main railway station.

The choice of location was deliberate.

Fifteen partisans had been shot there in August 1944 in retaliation for partisan attacks and Allied bombing raids.

Their bodies had then been left for public display.

The fascist bodies were left in a heap and by 2100 hours a considerable crowd had gathered.

The corpses were pelted with vegetables, spat at, urinated on, shot at and kicked.

Mussolini´s face was disfigured by beatings.

An American eyewitness described the crowd as “sinister, depraved, out of control.”

After a while, the bodies were hoisted up onto the metal girder framework of a half-built Standard Oil service station, and hung upside down on meat hooks to protect the bodies from the mob.

Above: Piazza Loreto, Milano, 29 April 1945. Mussolini (second from left), Petacci (middle)

At about 1400 hours, the American military authorities, who had arrived in Milano, ordered the bodies be taken down and delivered to the city morgue for autopsies to be carried out.

On 30 April, an autopsy was carried out on Mussolini at the Institute of Legal Medicine in Milano.

Mussolini had been shot with nine bullets.

His body now rests at his place of birth in Dovia di Predappio.

A monster long dead, an apostle of violence long removed, the undignified deaths of Mussolini (age 62) and Petacci (age 33) linger in bad memory.

We hoped Como would find our smiles for us again….

Sources: Wikipedia / Luigi Barzini, The Italians / Simon Sebag Montefiore, Monsters: History´s Most Evil Men and Women