20 September 2017, Landschlacht, Switzerland

Let´s be blunt.

Things are truly horrible in many countries on the planet these days.

Especially in America.

And there are some folks who suggest that a second US Civil War is coming.

Which raises two important questions….

Could it happen?

Should it happen?

In political philosophy, the right of revolution is the duty of the people of a nation to overthrow a government that acts against their common interests and/or threatens the safety of the people without probable cause.

Above: A replica of the Magna Carta on Display in the rotunda of the United States Capitol. The Magna Carta, the first constitutional charter of England, marks one of the earliest attempts to limit a sovereign´s authority.

Stated throughout history in one form or another, the belief in this right has been used to justify various revolutions, including the English Civil War, the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

Above: The storming of the Bastille prison, 14 July 1789, has come to symbolise the French Revolution, where a people rose up to exercise their right of Revolution.

By definition, a revolution is a fundamental change in political power or organisational structures that takes place in a relatively short time when the population rises up in revolt against the current authorities.

Could Americans become so dissatisfied that they would choose to take up arms against Washington DC and the Trump Administration?

Above: Donald John Trump (born 1947), 45th President of the United States (2017 – )

If it became clear that Trump and his posse was acting against Americans´ common interests (denial of universal health care, unequal taxation favouring the rich, etc) or was threatening the safety of the people without probable cause (threats to North Korea, denying conservation efforts, denying climate change, etc) then it could be argued that Trump and his gang of misfits should be removed from power.

But for a revolution to be effective, disgruntled Democrats and liberals cannot possibly win without greater support.

Without the overall consent of Congress against Trump -presently dominated by the Republicans…..

Above: The United States Capitol building, Washington DC

Without the support of the military willing to refrain from answering their call of duty to the government and instead standing up to be counted as supporters of a different way than that being practiced today….

Without the wealthy financially supporting the removal of the President….

Without the huge population of average workers that dominate the country statistically convinced that a change in the status quo will lead to a brighter and better tomorrow….

A revolution in America could not possibly succeed as things stand today.

Above: The presentation of the draft of the Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776

As much as private individuals feel like taking force against their rulers because of malice or because they have been injured by the rulers, they cannot succeed without support from the body of the people – a broad consensus involving all ranks of society.

Private individuals are socially forbidden to take force against their rulers until the body of the people feels concerned about the necessity of revolution.

Impeachment of President Trump may be desirable by many people, but only possible if both houses of the American government – the elected officials in Washington – decide that they can no longer tolerate Trump as the helm.

For now, the Republicans, of whom Trump leads, are more concerned with keeping their privileged positions rather than actually serving their country´s best interests.

Above: The logo of the US Republican Party

The Democrats, at present, lack cohesion.

Above: The donkey, a recognised symbol of the US Democratic Party, though not an official logo

Despite the popularity of Senator Bernie Sanders, the Democrats continue to marginalise anyone too progressive or too anti-Establishment among their ranks.

Above: US Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont

In this year 2017, a year where great change is desired but denied by circumstances, this year that marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, I think it might be interesting for those dissatisfied with the status quo to observe how within the span of a single week how a nation went from being an autocracy to becoming a republic.

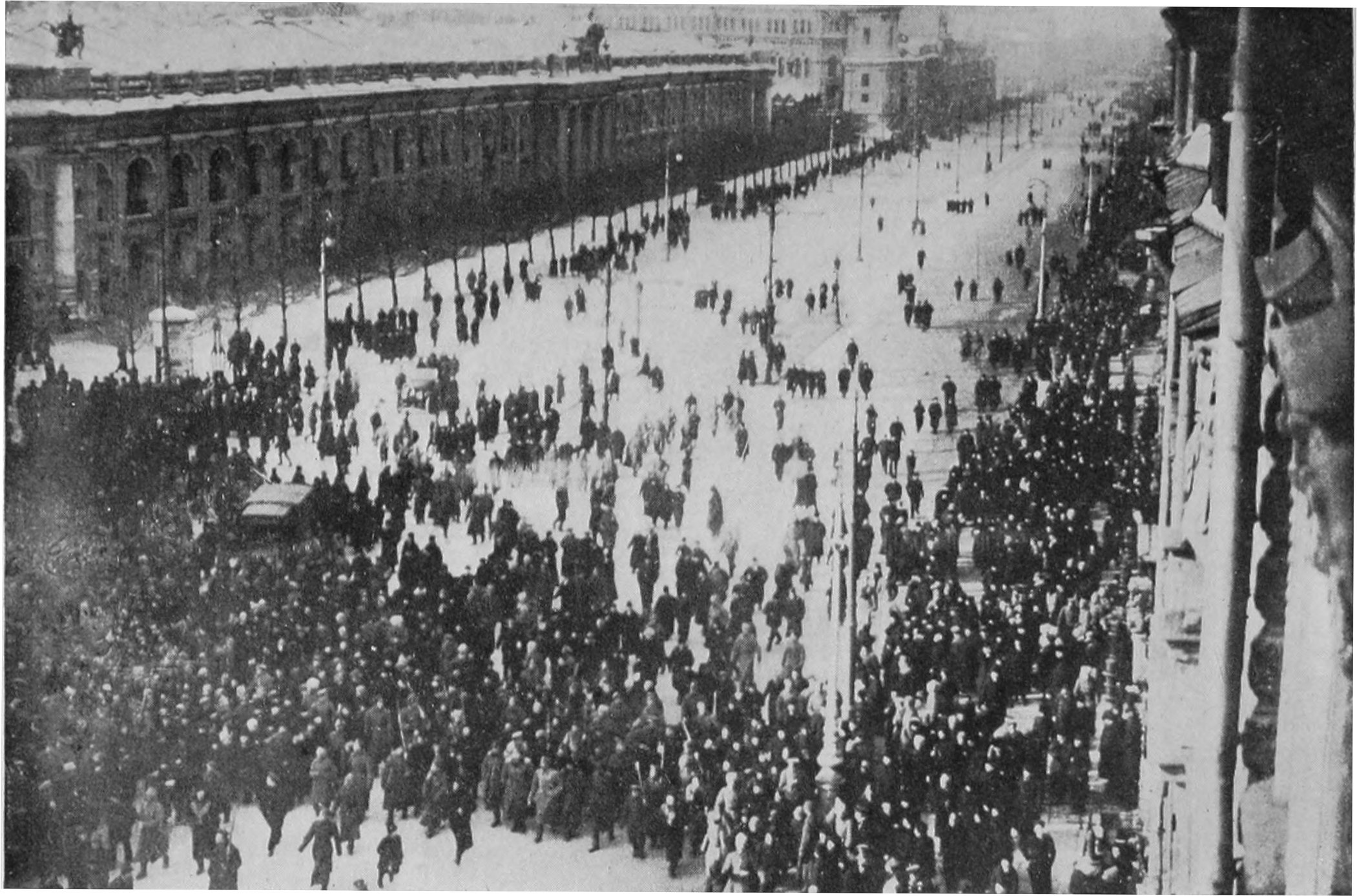

The February Revolution was the first of two Russian revolutions in 1917.

Above: Attacking the Tsar´s police during the first days of the February Revolution (23 February to 3 March 1917)

The Revolution centred on Petrograd (now known as St. Petersburg), then the Russian capital, where longstanding discontent with the monarchy erupted spontaneously into mass protests against food rationing, and armed clashes with police and military.

Above: Modern St. Petersburg.

(Clockwise from top left: Peter and Paul Fortress, Smolny Cathedral, Senate Square, the Winter Palace, Trinity Cathedral, and the General Staff Building)

Change should have begun within the Duma, the Russian Parliament.

Above: Tauride Palace, meeting place of the Duma and later the Russian Provisional Government

On 14 February 1917, after an extended Christmas break, the Duma assembled for another year.

At a time of mounting popular disturbance, and with several of its members engaged in covert plots to oust the Tsar, the session should have been a lively one.

Instead the deputies seemed to be wandering about “like emaciated flies.

No one believes anything.

All feel and know their powerlessness.

The silence is hopeless.” (A. I. Savenko)

The mood was sluggish and the speeches dull.

Outside the pompous meeting hall, the mood was no more positive among the leaders of the revolutionary underground.

“Not one party was preparing for the great upheaval.

Everyone was dreaming, ruminating, full of foreboding, feeling his way.” (Nikolai Sukhanov)

Across the water where the workers lived, the atmosphere was different.

The food crisis was now acute.

The wealthy could still have their fresh white bread in any restaurant, but families in the factory districts had begun to starve.

It was not just a question of inflation, although the price of everything from kerosene to eggs had multiplied beyond the reach of the hard-pressed.

The real problem in Petrograd, exacerbated by an overstretched railroad network in the provinces, was a shortage of grain.

The city´s wheat and flour stocks, already depleted, had fallen by more than 30% in January, leaving many without bread at all.

“Resentment is worse in large families, where children are starving and no words are heard except: peace, immediate peace, peace at any cost.” (Okhrana – Tsarist secret police – agent report, February 1917)

Even in 1917, Russia still produced enough food to feed itself.

The difficulty was to distribute it to the swollen population of the towns in Russia´s northern industrial regions and to the huge army concentrated in the Empire´s western borderlands.

The railway network had been geared in peacetime to moving grain surpluses from southern Ukraine and Russia´s southern steppe region not northward but to southern export outlets on the Black Sea.

As well there were problems with conflicts between the army, a number of civilian agencies and the local government bodies over how best to price and procure grain.

The big estates, which marketed all their grain, were hardhit by labour shortages, with 15 million men called up into the armed forces.

Meanwhile, industry could notsimultaneously supply the army and produce consumer goods at a price and quantity that would persuade peasants to sell their grain.

Part of the problem as regards food supply was that the Russian government had a weak presence in the villages where food was grown and most Russians lived.

The First World War required the unprecedented mobilisation of society behind the war effort.

Above: Scenes from World War I

This depended on a civil society with tentacles stretching down to every family and on a state closely allied to this society and capable of coordinating and co-opting its efforts.

To do this effectively, the state needed a high degree of legitimacy and the many groups and classes in society needed to have common values, confidence and commitments.

The Russian Empire entered the War deficient in all these respects.

The railways were a major problem with very serious consequences for military movements, food supply and industrial production.

Neither the railway network nor the rolling stock were adequate for the colossal demands of war.

In addition industry was diverted overwhelmingly to military production, with repairs to locomotives, rolling stock and railway lines suffering as a consequence.

Inflation took its toll on morale and discipline among railway men, as it did across the entire workforce.

The war – World War I (1914 – 1918) – was not going well for Russia.

Nearly six million casualities – dead, wounded and missing – had accumulated by January 1917.

Mutinies sprang up often, morale was low and the officers and commanders were very incompetent.

Like all major armies, Russia´s armed forces had inadequate supply.

The desertion rate ran at around 34,000 a month.

In the summer of 1915, in an attempt to boost morale and repair his reputation as a leader, Tsar Nicholas II announced that he would take personal command of the army, in defiance of almost universal advice to the contrary.

Above: Nicholas II of Russia (1868 – 1918), Tsar (1894 – 1917)

The result was disastrous.

The monarchy became associated with the unpopular war.

The monarchy´s legitimacy sank with every difficulty or failure in the war effort.

Nicholas proved to be a poor leader of men on the front, often irritating his own commanders with his intereference.

Being at the front meant he was not available to govern in Petrograd.

If Nicholas had departed for the front leaving behind a competent and authoritative Prime Minister to whom he had delegated full powers, this risk would have been worth taking.

He left the reins of power to his wife, the Tsarina Alexandra, who proved to be an ineffective ruler, announcing a rapid succession of different Prime Ministers and angering the Duma.

Above: Alexandra Feodorovna (1872 – 1918), Tsarina (1894 – 1917)

“In the 17 months of the Tsarina´s rule, from September 1915 to February 1917, Russia had 4 Prime Ministers, 5 Ministers of the Interior, 3 Foreign Ministers, 3 War Ministers, 3 Ministers of Transport and 4 Ministers of Agriculture.

This ministerial leapfrog not only removed competent men from power, but also disorganised the work of government since no one remained long enough in office to master their responsibilites.” (Orlando Figes, A People´s Tragedy)

The Duma President Mikhail Rodzianko, Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna and British Ambassador Sir George Buchanan joined calls for Alexandra to be removed from influence, but Nicholas refused.

Above: Mikhail Rodzianko (1859 – 1924), Duma Chairman (1911 – 1917)

The Duma warned the Tsar of the impeding danger and advised him to form a new constitutional government.

Nicholas ignored their advice.

Nicholas saw concessions to pressure as both a confession of weakness and a surrender of power to parliamentary government, which in his opinion was certain to lead to the disintegration of authority and lead to social and national revolution.

By stubbornly refusing to reach any working agreement with the Duma, Nicholas undermined the loyalty of even those closest to the throne and opened up an unbridgeable gap between himself and public opinion.

The Tsar no longer had the support of the military, the nobility, the Duma or the Russian people.

By 1917, the majority of Russians had lost faith in the Tsarist regime.

Government corruption was unrestrained.

The inevitable result was revolution.

Meanwhile, refugees from German-occupied Russia came in their millions.

The Russian economy was blocked from the Continent´s markets by the War.

Though industry did not collapse, it was considerably strained and when inflation soared, wages could not keep up.

To help conserve scarce flour stocks, the Commissioner of Food Supply prohibited the baking and sale of cake, buns, pies and biscuits.

There were also new restrictions on the provision of flour to factory kitchens and workers´ canteens.

The move had little impact on the bread supply, but working people greeted it with rage.

Because few people even had a vote, the only thing they could do was join a protest or a strike.

There was comfort in the thought that the most obvious discontent was economic.

“Such strikes as might occur would be primarily on account of the shortage of food supplies, but it is not considered likely that any serious disorders would take place.” (Sir George Buchanan)

Above: Sir George Buchanan (1854 – 1924), British Ambassador to Russia (1910 – 1918)

But what Buchanan failed to understand was that bread itself was political.

In factories and engine sheds, in shipyards and workers´ barracks, socialist activists were using hunger as a means to start a conversation with the people.

Leaflets, speeches and slogans connected the food shortage to the War and the autocracy.

Bread might have been their immediate grievance, but once the people joined a protest they were swept on by rousing songs and revolutionary catchphrases.

On 9 January 1917, the 12th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday Massacre of 1905, the protests were explicitly political.

Above: “Bloody” Sunday 22 January 1905 protest, led by Father Gapon, near Narva Gate, St. Petersburg

(See Canada Slim and the Bloodthirsty Redhead for more details about the Revolt of 1905.)

When the Duma convened on 14 February, the Mezhraionka (the Socialist Inter-District Committee) and its allies called the workers out again, this time with slogans about peace, democracy and even a republic.

There had been large scale protests before, but these were new, and called for more from government than cake and buns.

Even an outsider could pick up the change of mood.

“I was struck by the sinister expression on the faces of the poor folk who had lined up in a queue, most of whom had spent the whole night there.” (French Ambassador Maurice Paléologue, Diary entry of 21 February 1917)

Above: Maurice Paléologue (1859 – 1944), French Ambassador to Russia (1914 – 1917)

The peace of Petrograd was depended on its civil governor, Major General A. P. Balk, on the police (a force of 3,500 in a city of two and a half million) and on the governor of the military district, Major General S. S. Khabalov.

In charge of the coordination of them all was Interior Minister Alexander Protopopov, whose team was divided by mistrust.

Above: Alexander Protopopov (1866 – 1918), Russian Minister of the Interior (1916 – 1917)

Balk declared Khabalov to be “incapable of leading his own subordinates”.

No one trusted the police chief, A. T. Vasilev, whose promotion was entirely due to his friendship with Protopopov, and the best that anyone could say for Balk was that he was good at his paperwork.

Incompetents were nothing new in Russian government.

None of this might have mattered if the troops Khabalov commanded had been the right men for their job.

There were about 200,000 garrison soldiers in Petrograd, quartered in barracks all around the city centre.

Most lived in terrible conditions.

“The only troops in the capital were the depot battalions of the Guard and some depot Units of the line, most of whom had never been to the front.

They were officered by men who had been wounded at the front and who regarded their duty as a sort of convalescent leave from the trenches, or by youths fresh from the military schools.” (British military attaché Colonel Alfred Knox)

“In my opinion, this man (a disaffected Russian general) had confided in November 1916, the troops guarding the capital ought to have been weeded out long ago.

If God does not spare us a revolution, it will be started not by the people but by the army.”

The General was wrong.

The army played a crucial role, but only when the people had already kindled a revolt.

The February Revolution started with a celebration.

The festival of International Women´s Day had been created just before the War by German socialist Clara Zetkin.

Above: Clara Zetkin, German Marxist Feminist (1857 – 1933)

The event was planned in Petrograd for 23 February, but the comrades in the Russian empire were reluctant to make a special effort over Zetkin´s festival, disputing its propaganda value.

A march was planned, but it risked being small as well as mostly female.

“We need to teach the working class to take to the streets, but we have not had time.” (Alexander Shlyapnikov, letter to Lenin)

Back in December 1916, the Bolsheviks of Petrograd, the Petersburg Committee (they refused to adopt the Tsarist, more anti-German name of Petrograd) were raided by the Tsar´s secret police, the Okhrana, who not only arrested some of the Committee´s members but had captured its precious, costly and strategically vital printing press.

Without their precious printing press, the Bolsheviks could lead no one without a manifesto and a pile of pamphlets.

But other factions viewed the festival as a propaganda opportunity.

A leaflet from the Mezhraionka was crystal clear:

“The government is guilty.

It started the War and it cannot end it.

It is destroying the country and your starving is its fault.

Enough!

Down with the criminal government and the gang of thieves and murders!

Long live peace!”

Thursday 23 February 1916, Petrograd, Russia

If the weather had remained inhibitingly cold….

If Petrograd had received an adequate supply of flour….

If the workplace toilets had been heated to unfreeze the pipes….

The protests might have not been so large.

It was International Women´s Day and the embattled working women of Petrograd intended that their voices should be heard.

Hundreds of them – peasants, factory workers, students, nurses, teachers, wives whose husbands were at the front, and even a few upper class ladies – came out into the streets.

Although some carried banners with traditional suffrage slogans, most bore improvished placards referring to the food crisis.

“There is no bread. Our husbands have no work.”, they shouted.

As columns of women converged on Nevsky and Litieiny Prospekts, more militant women in the Vyborg (the industrial section of Petrograd) cotton mills were in no mood for compromise.

Since mid-January hunger had been worse by the continuing subzero temperatures affecting the supply of fuel into the city by rail.

Rowing boats on the Neva River were chopped up for firewood and, in the dead of night, people slunk into cemeteries “to fill whole sacks with the wooden crosses from the graves of poor folks and take them home for their fires”.

Throughout Petrograd strikes and protests had become so commonplace that the Okhrana were taking no chances.

On Protopopov´s orders, machine guns had been secretly mounted on the roofs of all the city´s major buildings, particularly around Petrograd´s main square, the Nevsky.

“The Cossacks are again patrolling the city on account of threatened strikes – for the women are beginning to rebel at standing in bread lines from 5 am for shops that open at 10 am in weather 25° below zero.”

(J. Butler Wright, Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright)

Their Women´s Day meetings resulted in a mass walk-out.

As they headed for the Neva, the ladies called on other workers to march with them, including the men of the New Lessner and Erikson factories, the major metalworks and munitions factories.

By noon, about 50,000 people had joined the protest on Vyborg´s main street, Sampsonievsky Prospect.

“I was extremely indignant at the behaviour of the strikers.

They were blatantly ignoring the instructions of the party district committees.

Yet suddenly here was a strike.

There seemed to be no purpose in it and no reason for it.”

(Bolshevik party representative and Erikson plant employee Kayurov)

They marched to the Liteiny Bridge to cross over to Nevsky Prospekt only to encounter police cordons on the Bridge barring their way.

The trams “stuffed full of workers” were surrounded by police when they reached the Liteiny Bridge.

Barging aboard, they checked every passenger to weed out those whose hands and clothes looked work-worn.

The idea was keep the poor where they belonged and make sure that their wretched protest could not interfere with decent life. (Alexander Shlyapnikov)

The more determined among them scrambled down onto the frozen river and made their way across the ice instead.

Others managed to get through the police block at the Troitsky Bridge only to be forced back by the police when they crossed the Neva.

On the Field of Mars, men and women were raised on the shoulders of others, shouting: “Let´s stop talking and act.”

A few women began singing the Marseillaise.

As the crowd moved off, heading for Nevsky Prospekt, a tram came swinging around the corner.

The marchers forced it to stop, took the control handle and threw it away into a snowbank.

The same happened to a second, third and fourth tram until the blocked cars extended all the way along the Sadovya to the Nevsky Prospekt.

Florence Harper – the first American female journalist in Petrograd – and her companion, photographer Donald Thompson from Topeka, Kansas, found themselves carried along with the tide of protesters.

Every policeman they passed tried to stop the marchers, but the women just kept on forging ahead, shouting, laughing and singing.

Walking at the head of the column, Thompson saw a man next to him tie a red flag onto a cane and start waving it in the air.

He decided that such a conspicuous position at the head of the marchers was “no place for an innocent boy from Kansas.”

“Bullets had a way of hitting innocent bystanders,” he told Harper, “so let´s beat it, while the going is good.”

That day, in response to increasing tension in the city, Khabalov had posters pasted on walls at every street corner, reassuring the public that “There should be no shortage in bread for sale.”

If stocks were low in some bakeries, this was because people were buying more than they needed and hoarding it.

“There is sufficient rye flour in Petrograd,” the proclamation insisted.

“The delivery of this flour continues without interruption.”

It was clear that the government had run out of excuses for the bread crisis – lack of fuel, heavy snow, rollling stock commandeered for military purposes, shortage of labour….

The people would not be fobbed off any longer.

Hunger was rife, fierce and unrelenting in half a million empty bellies across the working class factory districts.

“Here was a patent confession of laxity.

Whom was it expected to satisfy?

The Socialists who had already made up their minds for revolution, or the dissatisfied man in the street who did not want revolution, but pined for relief from an incapable government?” (Times correspondent Robert Wilton)

As the day went on, the rank of women marchers in and around the Nevsky swelled to around 90,000.

“The singing by this time had become a deep roar, terrifying, but at the same time fascinating….fearful excitement everywhere.” (Donald Thompson)

Once more the Cossacks appeared as if by magic, their long lances gleaming in the sunshine.

Time and again they attempted to scatter the columns of marching women by charging them at a gallop, brandishing their short whips, but the women merely regrouped, cheering the Cossacks wildly each time they charged.

When one woman stumbled and fell in front of them, they jumped their horses right over her.

People were surprised.

These Cossacks weren´t the fierce guardsmen of Tsardom whom the crowds had seen at work in 1905, when hundreds of protesters had been killed in the Bloody Sunday protest.

This time they were quite amiable, playful even.

They seemed eager to capitulate to the mood of the people, and took their hats off and waved them close to the crowd as they moved them on.

So long as they only asked for bread, the Cossacks told the marchers, they would not be on the receiving end of gunfire.

And so it went on, until six in the evening.

As the mob surged to the constant drumbeat calls for bread, the Cossacks charged and scattered people in all directions, but there was no real trouble.

Police rounded up anyone who attempted to stop and give speeches, but protestors otherwise walked the streets with their red flags all day long and had not been fired upon.

It was left to the tsarist police to finally disperse the crowds, who had largely gone home by 7 pm as the cold of the evening drew in.

Across the river, in the industrial quarters, acts of sporadic violence had erupted throughout the day.

Bakeries were broken into and raided.

Grocery stores had their windows smashed.

Later that evening, Major-General Alfred Knox met with the Duma industrialist Alexander Guchkov who described the food shortage as the worst catastrophe his government had faced to date, more crippling and more dangerous than any battlefield defeat.

Above: Alexander Guchkov (1862 – 1936), 4th Duma Chairman (1910 – 1911), Russian War Minister (1917)

Guchkov could already sense that trouble lay ahead.

“Questioned regarding the attitude of workmen in the towns towards the War, Guchkov conceeded that from 10% to 20% would welcome defeat as likely to strengthen their hands to overthrow the government.” (Alfred Knox)

Throughout the night strike committees in Petrograd and Vyborg were plotting to seize the moment.

A great many troops patrolled the city, for that day a disorganised and elemental force had finally been let loose on Petrograd.

The flame of Revolution had been lit among the hungry marchers on the Nevsky and the strikers across the river.

Revolution – so long talked of, dreaded, fought against, planned for, longed for, died for – had come at last, like a thief in the night, none expecting it, none recognizing it.

One week later Tsar Nicholas II would abdicate, ending the Romanov Dynasty, ending the Russian Empire, ending the chaos that had ensued in the days that followed the Women`s Day march.

Above: Nicholas II (seated) abdicating the Russian throne on 2 March 1917

A dynasty that had ruled for 300 years would depart within a week, with a whimper rather than a bang, because few Russians were willing to defend it.

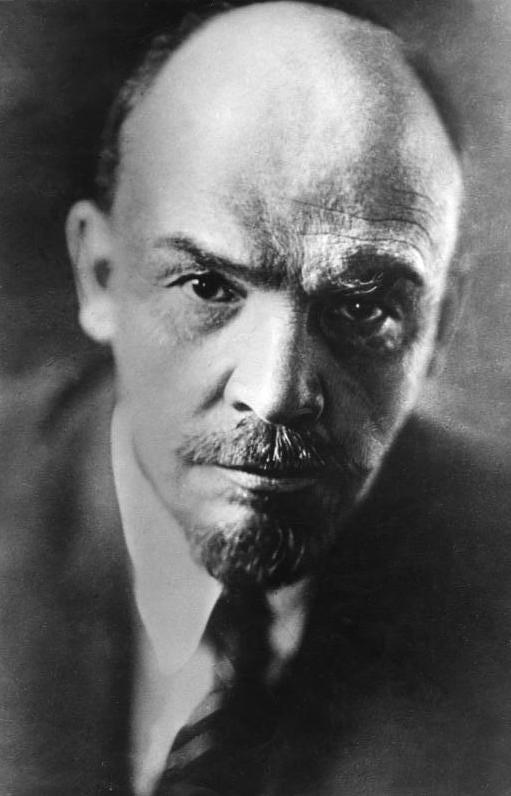

Eight months later, the second Revolution in Russia in 1917, the October or Bolshevik Revolution would occur when the Bolsheviks led by Lenin – returned from exile in Switzerland – would seize control of the government established after Nicholas´ abdication and transform the liberated-from-autocracy democratic republic into a totalitarian regime.

Above: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, aka Lenin (1870 – 1936)

But Russia had, for the briefest of moments, a chance for democracy.

Creating a peasant-based democracy almost from scratch in a country as enormous as Russia was a daunting task.

A democracy begun spontaneously by a group of women tired of long bread lines, tired of hunger, tired of frozen toilets, tired of their men away on the front, tired of casualities.

Brave enough to face certain death by men armed to the teeth.

Maybe that is how change might come to America.

Spontaneously.

When enough Americans become tired of the way things are and brave enough to stand up to the powers that have abused them for far too long.

Perhaps things have to get even worse before spontaneous and united dissatisfaction can occur.

Perhaps darkness must fall before dawn can arise.

Before a true unity – undivided by religion, race, income or partisan politics, but united by a desire for equality of opportunity and respect – can arise.

All things change.

Above: Cover of “Power to the People” single (1971), John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band

Sources: Wikipedia / Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917 / Catherine Merridale, Lenin on the Train / Dominic Lieven, Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia