Landschlacht, Switzerland, 1 November 2017

Within a week, last week, spent in London we crossed Praed Street at least a dozen times, a street “not at any time one of London´s brighter thoroughfares”. (John Rhode, The Murders in Praed Street)

Above: Praed Street, Paddington district, London

“I´ve walked this street in far too many towns….

Same scraps of paper blown, same windows full of girlie mags, the cheap gold lettering on doors: Suits altered. Come in and browse….

You live this road forever and no love comes by….

I´ve walked this street in lots of towns, always foreign weather at my throat.

Same paper blown, same broken man begging me for money and I overgive.”

(Richard Hugo, “Walking Praed Street“, The Lady in Kicking Horse Reservoir)

Another American like Hugo, August Derleth had his 1920s successor to Sherlock Holmes, Solar Pons, with offices based at 7B Praed Street.

Above: August Derleth (1909 – 1971)

Yet another American compared Bramford House in New York City where the principal characters live to “a house in London, on Praed Street, in which five separate murders took place within sixty years”.

(Ira Levin, Rosemary´s Baby)

Above: Ira Levin (1929 – 2007)

Praed Street appeared in the BBC drama series House of Cards, as an accommodation address set up by main protagonist Francis Urquhart as part of a plot to force the resignation of the sitting Prime Minister.

In Lawrence Durrell´s The Dark Labyrinth, a character complains he “could not be carried away by fairy tales of the Second Coming written in the Praed Street vein”.

Above: Lawrence Durrell (1912 – 1990)

Praed Street runs straight in a southwesterly direction from Edgware Road to Eastbourne Terrace in London´s Paddington district.

Above: London Paddington Station

Besides the mentions in literature, Praed Road is known for only five things: Paddington Station, the Hilton London Metropole Hotel (formerly the Great Western Hotel), the Royal Mail western depot, the Moroccan Consulate (only known by Moroccan expats or travellers to Morocco) and St. Mary´s Hospital.

Above: The Hilton Hotel on Praed Street, London

Praed Street is named after William Praed (1747-1833), chairman of the company which built the Grand Union Canal basin which lies just to the north of Paddington Station.

Crossing Praed Street, my wife and I, much like Richard Hugo, mused and mulled over each day what we could do while we were in London:

“I could sound cultured in the drab East End, or sweet in Soho, or in Barclays Limited (so limited they don´t cash Barclays checks) gracious as I compliment the Tube.

I´m learning manners. Thank you very much.

The money stops me. What is 8 and 6?….

Tonight I´ll hear the jazz in Golders Green.

Above: Golders Green Clock Tower, London

Tomorrow the Hampstead literary scene.

Above: Poet John Keats´ House, Hampstead, London

Next day, up river to the park at Kew and next day, you.

Above: The Great Pagoda, Kew Gardens, London

Ah, love, to feed the ravens in St. James, and that frightfully stuffy, hopelessly dignified, brazenly British, somewhat mangy lion in the Zoo….”

Above: St. James Park Lake with Buckingham Palace in the background

(Richard Hugo, “Walking Praed Street”, The Lady in Kicking Horse Reservoir)

Where precisely is the East End of London?

I remain unsure.

Time spent in Soho, a district to the southeast of Paddington, was indeed sweet.

Above: A typical Soho backstreet scene

And money did confuse us.

Not only had the pound coins we had from previous visits to Britain lost their validity a fortnight before, but as well every country´s small change uses different coin sizes for varying coin values, so while a half franc/50 rappen coin is Switzerland´s smallest silver coin, in Britain a half pound/50 pence coin is Britain´s biggest silver coin.

Barclays directed us to the Royal Mail or the Bank of England if we desired to exchange old pound coins for new.

We didn´t bother, but instead gave away the coins at museum donation boxes when we could.

We never got to Golders Green, but we did hear jazz at the Montreux Jazz Café in Zürich Airport.

Above: The Montreux Jazz Cafe, Zürich Airport

We visited Hampstead and thought about Iain Fleming, Goldfinger and John Keats.

Kew, we did not do, but St. James we did see, not ravens but Canada geese and many ducks.

Above: Duck Island Cottage, St. James Park, London

There was no time for the Zoo nor the Wetlands, and, alas!, no time to explore the parks or walkways that run through this great metropolis.

As for the Tube, London´s Underground, I feel towards it as I feel towards the City that spawned it – decidedly undecided as to whether to love or loathe it.

Travelling with my wife inevitably leads to a hospital and a graveyard.

She likes to peek at other hospitals outside the ones she works at and into graveyards as She finds them peaceful and artistic havens within a city.

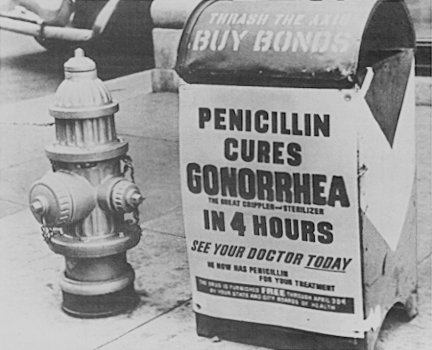

St. Mary´s Hospital, of course, was tempting, for it was here where both heroin and pencillin were discovered.

Here is a kind of Royal baby factory where Princess Charles and Princess Diana´s sons William (1982) and Harry (1984) were born, followed two decades later by Prince William and Duchess Kate´s children George (2013) and Charlotte (2015).

Above: The British Royal Coat of Arms

The Hospital has seen other notable births like Olivia Robertson (1917 – 2013), author, co-founder and High Priestess of the Fellowship of Isis; British musician Elvis Costello (1954), and Canadian actor Kiefer Sutherland (1966).

Above: Kiefer Sutherland

And the Hospital has had notable people on staff like Nobel Prize winners Alexander Fleming and Rodney Porter; Augustus Waller, whose research led to the invention of the electrocardiogram (ECG); Wu Lien-teh, the Plague fighter of China; and Neurology Professor Roger Bannister, the first man to run a mile in four minutes.

Above: Roger Bannister

I like the story of Charles Wright (1844-1894), who while searching for a non-addictive alternative to morphine discovered heroin.

Above: Charles Wright (1844 – 1894)

Heinrich Dreser, a chemist at Bayer Laboratories, would continue to test heroin and Bayer would market it as a sedative for coughs in 1888.

When heroin´s addictive potential was recognised, Bayer ceased its production in 1913.

Wu Lien-teh (1879 – 1960) spent his undergraduate clinical years at St. Mary´s before returning to Malaysia in 1903.

Above: Wu Lien-teh

Wu was very vocal in the social issues of his time and founded the Anti-Opium Association, which attracted the attention of the powerful forces involved in the lucrative trade in opium.

This led to a search and subsequent discovery of a mere ounce of opium in Dr. Wu´s dispensary, which was considered illegal, even though he was a fully qualified doctor who had purchased this to treat opium patients.

His prosecution and appeal rejection attracted worldwide publicity.

In the winter of 1910, Dr. Wu was given instructions by Peking to travel to Harbin, China, to investigate an unknown disease which killed 99.9% of its victims, the beginning of a large plague across Manchuria and Mongolia which ultimately claimed 60,000 victims.

Dr. Wu would be remembered for his role in asking for imperial sanction to cremate plague victims, as cremation of these infected victims turned out to be the turning point of the epidemic.

The suppression of this plague changed medical progress in China.

A blue plaque outside St. Mary´s alerts passers-by that Alexander Fleming (1881-1955) discovered penicillin in the second-storey room above the Hospital´s dingy Norfolk Place entrance.

Above: Alexander Fleming

When Fleming was born, antibiotics did not exist.

Minor infections often proved fatal and a quarter of all hospital patients died of gangrene after surgery.

When Fleming enrolled as a medical student at St. Mary´s in 1900, he dreamed of becoming a surgeon, but he was given a position in the Inoculation Department, where he remained until his death.

The poky laboratory where he worked between 1919 and 1933 is today a Museum.

Inside, the wooden counter is cluttered with vials and test tubes containing mysterious fluids, tattered leather-bound tomes, a couple of antique microscopes and glass culture dishes.

One day in 1922, Fleming was hunched over his bacteria cultures as usual, despite suffering from a nasty cold.

A drop of snot landed on his petri dish, which led to his discovery of the antiseptic qualities of mucus, saliva and tears.

In September 1928, Fleming made other chance discovery that changed the course of medical history.

When one of his cultures was contaminated with mould from a lab downstairs, Fleming hit on the healing properties of fungus, effectively inventing penicillin.

Fleming´s assistant, Stuart Craddock, ate some of this “mould juice” to prove it was not poisonous.

Craddock claimed that it tasted like Stilton cheese, prompting a flurry of sensational headlines about mouldy cheese being a miracle cure for disease.

“It couldn´t have happened anywhere but this musty, dusty lab, as the mould would not have grown in a more hygienic environment.”

(Kevin Brown, Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum curator)

This street containing a Hospital with record-breaking runners, plague fighters and medical discoverers ends in the southwest at Eastbourne Terrace.

But should the curious pedestrian wish to continue to follow the now-named Craven Road which is renamed yet again as Craven Hill to Leinster Gardens in the Bayswater district….

When London´s first Tube line was extended westwards, inevitably some houses had to be demolished.

The owners of 23/24 Leinster Gardens sold up, but local residents demanded that the facade of these five-storey terraces be rebuilt to keep up appearances.

At first glance, the fake facades are indistinguishable from their neighbours.

Above: 22 Leinster Gardens (left) and 23 Leinster Gardens (right)

But look closer and you will see that all 18 windows are blacked out with grey paint.

Although there are no letterboxes, the address is predictably common with conmen.

Above: Behind the facade of 23/24 Leinster Gardens

In the 1930s, unsuspecting guests turned up to a charity ball at 23 Leinster Gardens in full evening dress.

They never got their money back.

And in a way the fake houses of Leinster Gardens, the accidental discoveries, the trust of royalty and celebrity, and the unexpected heroes of St. Mary´s all seem to say one thing.

There may be more than meets the eye to a place or to a person.

There is more than scraps of paper or windows full of girlie magazines or lettering on doors.

Wherever you are, who is to know who will fail and not fail?

Who is to know the banging storm within these hearts or the returning winds that stir these souls?

We must not only see.

We must observe.

Above: Praed Street, London

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Rachel Howard and Bill Nash, Secret London: An Unusual Guide