Landschlacht, Switzerland, 11 November 2017

I have a man cold.

I should have been at work yesterday, but, oh!, the agony, the suffering!

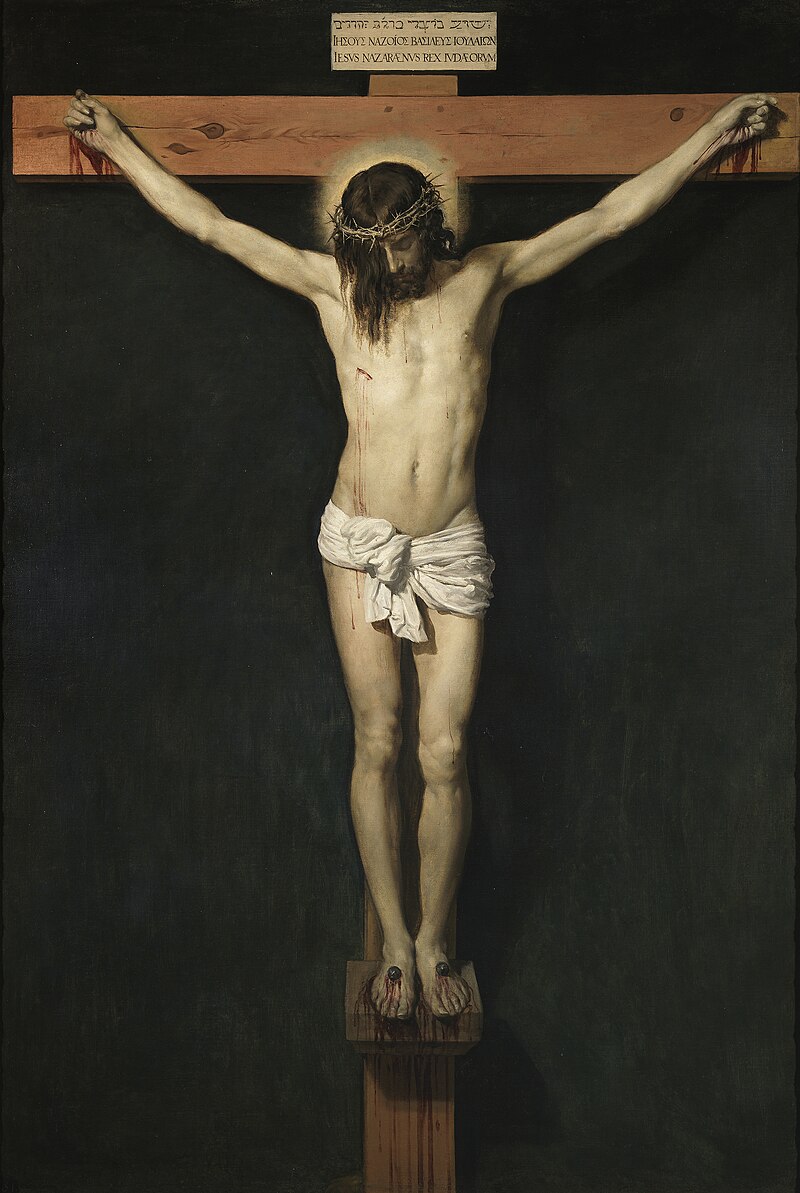

My God! My God! Why have you forsaken me?

But with voice muted and a head full of unmentionables one shouldn´t mention, I find myself running between toilet and kitchen, bedroom and study, torn between the discomfort of body and the restlessness of mind.

When one is ill and alone, thoughts drift to ideas of mortality.

No, a man cold won´t kill me, but life is not enjoyed in the living through it.

I am not dying, but my imagination imagines it so.

When one is ill and alone, one begins to question one´s beliefs about religion, Karma, God, that sort of thing.

I have written about this idea of religion before….

(See Buddha by the Mosel, No Jains in Switzerland, Them and Us: Points of View, The glory departed, Tough to be the Chosen, The desire for an Amish paradise, The Little Shop of Ethics, How to convert this barbarian, Giving thanks, Saints and Monsters, The Jihad of Canada Slim, Snowflakes from Nazareth, Unwanted Christmas presence, Reformation by the River and the Railroad Tracks, Flames and broken promises, Burkinis on the beach, the trilogies Moving heaven and earth and Adam in the Abbey, Behind the veil: Islam (ophobia) for dummies of this blog.)

….but as the year draws to a close – as Christmas decorations already present in November remind us – I realise that 2017 marks an important religious event.

Less than a fortnight ago the Christian world, i.e. the non-Catholic Christian world, celebrated the 500th anniversary of the start of the Reformation.

It is said that on the night of 31 October 1517, Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) nailed his protest, his Ninety-Five Theses, against the Catholic Church´s practices on the door of the All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany.

His cause would be adopted and adapted by other religious reformers in other nations.

Among these other reformers would be the famous Swiss reformers John Calvin (1509 – 1564) and Huldrych (or Ulrich) Zwingli (1484 – 1531).

Above: John Calvin

Above: Huldrych Zwingli

I have spoken of Zwingli before in Reformation by the River and the Railroad Tracks and of the early reformer Jan Hus and the Council of Constance in Flames and broken promises.

Above, I used the words Christ was said to have used when he was hanging on the cross.

I used these words in jest to mock how exaggerated a man can make a man cold sound.

Without the Reformation….

I would have been guilty of sacrilege, possibly punishable by death.

I knew of these words independently through my own reading from my own Bible.

Without the Reformation…..

I could not have discovered them without my having been educated by the Church, from the only Bible my particular church happened to have.

I knew these words in English.

Without the Reformation…..

I would only have known them through a priest who would have spoken these words in Latin.

So before the sun sets on 2017 I want to speak once again in detail of Zwingli – local to the part of Switzerland I live in – and of why his actions were not only a Reformation of the Church in Switzerland but also shaped the political destiny of the country as well, as one of the men and women, one could say, built Switzerland.

Similar to the approach I took earlier with the story of Lenin in Switzerland….

Above: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, aka Lenin (1870 – 1924)

(See Canada Slim and the Bloodthirsty Redhead, CS and the Zimmerwald Movement, CS and the Forces of Darkness, CS and the Dawn of a Revolution, CS and the Bloodstained Ground, CS and the High Road to Anarchy, CS and the Birth of a Nation, CS and the Coming of the Fall, CS and the Undiscovered Country, and, finally, CS and the Sealed Train of this blog.)

….I shall take you, gentle reader, to the places where Zwingli actually walked and will retrace his steps half a millennium later within Switzerland.

I have already walked three separate days “in his steps” from Wildhaus, in the Toggenburg region where he was born, to Weesen, by the Walensee, where he attended school.

(For more on the Toggenburg region, please see The Poor Man of Toggenburg of this blog.)

In the future – health, weather and time permitting – I intend to walk, a six-day walk, from Weesen to Kappel am Albis, where Zwingli died, via Glarus, Einsiedeln and Zürich, places quite important in his biography.

Similar to Lenin, there are things about Zwingli I have not liked to learn, but like Lenin, Zwingli had an impact on the world that cannot be lightly dismissed nor should be forgotten.

As I interspersed tales of Lenin within tales of northern Italy/southern Switzerland and London, so I shall alternate between Zwingli, London and northern Italy/southern Switzerland (and perhaps other tales), so hopefully that neither I as writer nor you as reader become bored.

The story of Zwingli will not be short in the telling, but I will try not to make the story feel long.

To speak of Zwingli, one needs to first understand what led to the world in which Zwingli came to be.

(For Switzerland´s early history as a Confederation, please see The underestimated 1: The bold and the reckless of this blog.)

The history of Christianity was not an easy one.

Founded by Jews who truly believed that the man Jesus Christ was truly the divine son of God, the saviour of mankind, Christianity grew from being a scattering of Christian communities in Anatolia (“the seven churches in Asia”, according to Revelations), to being persecuted by the Roman Empire, to being adopted by Rome, with religious headquarters established in Rome and Christianity´s leader the Pope.

Much debate and division occurred through the centuries over theological truths, sometimes resolved through ecclesiastical meetings called Councils, sometimes through bloodshed and sometimes through parting of the ways between disagreeing factions.

The Great Schism of 1054 saw the Christian Church split in two, to form the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church.

The Western Schism saw the Catholic Church (1378 – 1417) split in which by the end of 1413 three men simultaneously claimed to be the true Pope.

This Schism was ended when the Council of Constance (Konstanz)(1414 – 1418) dismissed the three contenders and elected a fourth agreeable to everyone.

Above: Council Hall, Konstanz

Unrest due to this Great Schism of Western Christianity excited wars between princes, uprisings among the peasants and widespread concern over corruption in the Church.

New perspectives on Christianity and how it should be practiced came from John Wycliffe at Oxford University and from Jan Hus at Charles University in Prague.

Above: John Wycliffe (1320 – 1384)

Hus (1369 – 1415), influenced by Wycliffe´s ideas, objected to some of the practices of the Church and wanted to return the Church in Bohemia and Moravia to early Christian practices of liturgy (how mass is presented) in the language of the people – for Hus´ people, Czech – (The Church universally spoke only Latin wherever it was.), the non-ecclesiastical or lay population receiving communion (the ceremony where bread and wine are consumed to represent the body and spirit of Christ) just as religious leaders did, married priests (The Church required its leaders to be chaste and celebate, so as to avoid sex and pleasure distracting from the worship of God.), and the elimination of indulgences (a payment to the Church to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins – acts of bad behaviour) and the concept of purgatory (an intermediate state of being or place in which those who wish to go to heaven must first undergo purification to achieve the necessary holiness to enter this eternal place of joy).

Hus rejected indulgences and adopted a justification by grace through faith alone or sola fide – the idea that faith alone, not anything a person might do in good works, saves souls from eternal damnation.

The Catholic Church officially concluded this debate at the Council of Constance by condemning Hus, who was executed by burning despite a promise of safe conduct.

Above: Jan Hus (centre) at the Council of Constance

The Church maintained its position that it was and should be the West´s foremost temporal (earthly/political) and divine power.

The Council did not address the national tensions nor the theological questions stirred up by the past century, which would immediately result in the Hussite Wars and later to the Reformation.

The Hussite Wars (1419 – 1434), also called the Bohemian Wars, were fought between the protesting followers of Jan Hus and various European monarchs loyal to the Catholic Church, as well among various factions of the Hussites themselves.

Above: The burning of Jan Hus by the Council of Constance, 6 July 1415

The Hussite community of believers included most of the Czech population of the Kingdom of Bohemia and formed a major spontaneous military power.

They defeated five crusades proclaimed against them by the Pope and intervened in the wars of neighbouring countries.

The fighting ended when the moderate faction of the Hussites defeated the radical faction.

They agreed to submit to the authority of the Catholic Church and the King of Bohemia in exchange for being allowed to practice their variant form of Catholicism of universal communion, that whomsoever did wrong was no longer protected by divine immunity, that the Church would own no worldly wealth save that which was needed to function.

Prior to Pope Sixtus IV (1471 – 1484), indulgences were sold only for the benefit of the living.

Above: Francesco della Rovere, aka Sixtus IV, Pope (1471 – 1484)

Sixtus established the practice of selling indulgences for the dead to be released from purgatory, thus establishing a new lucrative stream of revenue for the Church with agents scattered across Europe to collect this.

Pope Alexander VI (1492 – 1503), one of the most controversial Popes who fathered seven children by mistresses and was suspected of gaining the papal throne through bribery and increased family finances by selling off Church positions of power.

Above: Rodrigo de Borja, aka Alexander VI, Pope (1492 – 1503)

It would be this papal corruption, particularly the sale of indulgences, that would inspire Luther to write his 95 Theses and nail them to the Wittenberg church door.

Martin Luther was born to Hans and Margarethe Luther in Eisleben, Saxony, on 10 November 1483.

Above: Martin Luther

His family moved to Mansfeld in 1484, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelter and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local town council.

Hans became a town councillor in 1492.

Martin had several brothers and sisters.

Hans was ambitious for himself and his family and was determined that Martin, his eldest son, would become a lawyer.

In accordance to his father´s wishes, Martin enrolled in law school at the University of Erfurt in 1505.

On 2 July 1505, Martin was returning to university on horseback after a trip home.

During a thunderstorm, a lightning bolt struck near him.

Terrified of death and divine judgment, Martin cried out:

“Help! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!”

He left law school, sold his books and entered St. Augustine´s Monastery in Erfurt on 17 July 1505.

On 3 April 1507, the Bishop of Brandenburg ordained Luther in Erfurt Cathedral.

In 1508, von Staupitz, the first dean of the newly founded University of Wittenberg, sent for Luther to teach theology.

On 19 October 1512, Luther was awarded his doctorate in theology and succeeded Staupitz as the chair of the theology faculty.

Luther was made provincial vicar of Saxony and Thuringia in 1515 and was required to visit and oversee each of the eleven monasteries in his province.

In 1516, Johann Tetzel (1465 – 1519), a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church´s Pope Leo X (1513 – 1521) to sell indulgences to raise money in order to rebuild St. Peter´s Basilica in Rome (which had begun in 1506).

Above: Johann Tetzel

Tetzel´s experiences as a preacher of indulgences led to his appointment by Albrecht von Brandenburg (1490 – 1545), the Archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt, had to contribute a considerable sum toward the rebuilding of St, Peter´s.

Above: Albrecht von Brandenburg

Archbishop Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo to conduct the sale of a special indulgence that wouldn´t just reduce time in purgatory but would eliminate it completely, in return for half the sale proceeds going to Rome and the other half to pay the Archbishop´s debts.

Above: Giovanni di Lorenzo de´ Medici, aka Leo X, Pope (1513 – 1521)

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his Archbishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences, enclosing with his letter a copy of his Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, which came to be known as the 95 Theses.

In Theses 86, Luther asked:

“Why does the Pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?”

(Marcus Licinius Crassus (115 – 53 BC) was a Roman general and politician who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire, who amassed an enormous fortune during his life and who was considered to be one of the wealthiest men in Roman history.)

Above: Bust of Crassus, Louvre Museum, Paris

Luther strongly objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel:

“As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.”

Luther insisted that, since forgiveness is God´s alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error.

Within two weeks, copies of the 95 Theses had spread throughout Germany.

Within two months, they had spread throughout Europe.

This spread was a result of Gutenberg´s printing press (invented in 1439) which allowed the dissemination of information in the language of the people possible and swift.

Above: Johannes Gutenberg (1400 – 1468)

Thus the Reformation was born, which would give rise to Protestant movements across Europe and into America and would lead to extreme bloodshed especially in central Europe.

The Reformation and the resulting warfare and bloodshed would last until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, leaving behind a West that would forever be transformed for both better and worse.

Reformation would take two forms: Magisterial (with the support of political authorities) and Radical (without political authority support).

Luther´s initial movement (Lutheranism) within Germany diversifed and other reform impulses arose independently of Luther.

The Reformation would occur, either simultaneously or subsequently, in the Baltics, Scandinavia, Switzerland, Hungary, France, the Netherlands, Scotland and England.

The end result would be that northern Europe would come under the influence of Protestantism, southern Europe remained Catholic, while central Europe was the site of fierce bloody conflict, culminating in the Thirty Years War (1618 – 1648), which left it devastated.

The Thirty Years War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in human history, the deadliest European religious war in history, a war that resulted in eight million fatalities.

Meanwhile in Switzerland….

Above: Map of Switzerland, 1530

The Swiss Confederation in Huldrych Zwingli´s time consisted of 13 Cantons.

Unlike today´s Switzerland, which operates under a federal government, each of the thirteen cantons was nearly independent, conducting its own domestic and foreign affairs.

Each canton formed its own alliances within and without the Confederation.

This relative independence served as the basis for conflict.

Military ambitions gained additional impetus with the competition to acquire new territory and resources.

Toggenburg, the region of Huldrych´s birth and early childhood, had seen warfare in his father´s time.

The Old Zürich War (1440 – 1446) had seen Canton Zürich, allied with the Hapsburgs of Austria and the Kingdom of France, fight the Swiss Confederacy – Bern, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Glarus, Zug and Appenzell – over the succession of the Count of Toggenburg.

The end result was inconclusive with both sides exhausted.

Zürich was readmitted into the Confederation when it dissolved its alliances with Austria and France.

The war showed that the Confederation had grown into a political alliance so close that it no longer tolerated separatist tendencies of a single member.

Shortly before Huldrych´s birth, the Confederation was engaged in the Burgundian Wars (1474 – 1477) allied with the Duchy of Lorraine against the Duchies of Burgundy and Savoy, which gave the Swiss Confederation the reputation of being one of the most powerful military forces in Europe of near invincibility and the rise of the practice of engaging the services of Swiss mercenaries on the battlefields of Europe.

By the time Huldrych reached his 16th year, the Swiss Confederation, victorious in its last conflict against the Habsburgs, the Swabian War of 1499, the Swiss Confederation was de facto independent.

This sense of pride in Swiss military prowess gave rise to a Swiss national consciousness and patriotism.

At the same time, Renaissance humanism, with its universal values and emphasis on scholarship had taken root in the Confederation.

The Renaissance (1345 – 1492) was a time in Western history that would see new developments in educational reforms, diplomacy and inductive reasoning.

Francesco Petrarca (1304 – 1374), aka Petrarch, rediscovered the letters of Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC) to his best friend Titus Pomponicus Atticus (110 – 32 BC).

Above: Bust of Cicero

Cicero, a Roman politician and lawyer, is considered to be one of Rome´s greatest orators and prose stylists.

His influence on the Latin language was so immense that the subsequent history of prose, not only in Latin but in European languages up to the 19th century, was said to be either a reaction against or a return to his style.

Cicero introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary (words such as evidence, humanity, Quality, quantity, essence).

Petrarch´s rediscovery of his letters is often credited for initiating the Renaissance in public affairs, humanism and classical Roman culture.

Cicero would be rediscovered again during the Enlightenment (1715 – 1789) and would have an important impact on leading 18th century thinkers like John Locke (1632 – 1704), David Hume (1711 – 1776), Charles de Montesquieu (1689 – 1755) and Edmund Burke (1730 – 1797).

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (35 – 100 AD), aka Quintilian, a Roman rhetorician from Hispania (modern Spain), declared that Cicero was “not the name of a man, but of eloquence itself.”

Cicero is credited with transforming Latin from a modest utilitarian language into a versatile literary medium capable of expressing abstract and complicated thoughts with clarity.

Petrarch´s rediscovery of Cicero´s letters in 1345 provided the impetus for searches for ancient Greek and Latin writings scattered across Europe.

Disdaining what he believed to be the ignorance of the centuries between the fall of the Roman Empire and the era in which Petrarch lived, he is credited with the coining the phrase “the Dark Ages”.

Cicero´s letters to Atticus contained such a wealth of detail concerning the inclinations of leading men, the faults of the generals and the revolutions in the government that the reader has little need for a history of that period.

Following the invention of Johannes Gutenberg´s printing press, Cicero´s On Obligations (his ideas on the best way for a person to live, behave and observe moral obligations) was the second book printed in Europe after the Gutenberg Bible.

Cicero´s writing inspired the Founding Fathers of the American Revolution and the revolutionaries of the French Revolution.

Petrarch himself would become a Cicero of his age, noted for his epic poetry and extensive correspondence, his travels as ambassador and for pleasure (Petrarch has been called the first tourist.), and his volumimous library of ancient manuscripts.

Above: Francesco Petrarca, aka Petrarch

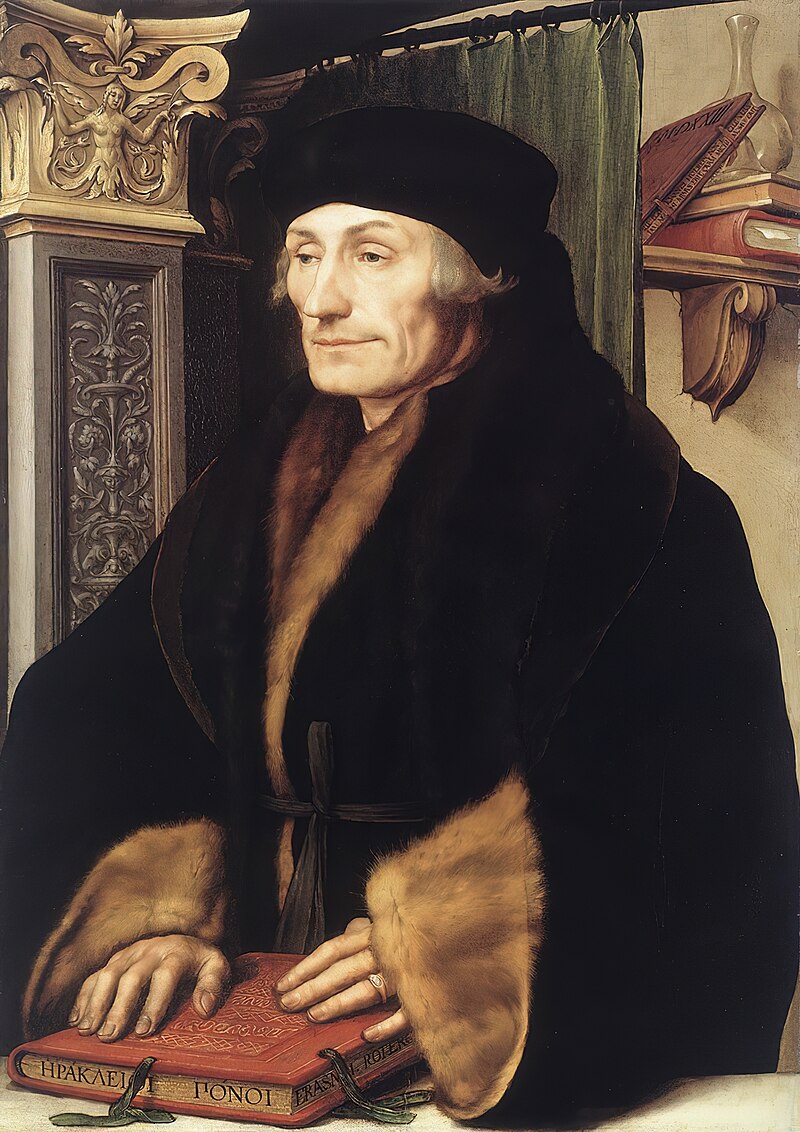

Another admirer of Cicero´s would be Martin Luther´s and Huldrych Zwingli´s contemporary, Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (1466 – 1536), aka Erasmus of Rotterdam, who though critical of the abuses he saw within the Catholic Church and called for reform, he kept his distance from Luther and continued to recognise the authority of the Pope, emphasizing a middle way with a deep respect for tradition, piety and grace, rejecting Luther´s emphasis on faith alone.

Above: Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, aka Erasmus

When Erasmus hesistated to support him, Luther became angered that Erasmus was avoiding the responsibility of reform due either to cowardice or a lack of purpose.

But any hesitancy on Erasmus´ part stemmed, not from lack of courage, but rather from a concern over mounting disorder and violence of the reform movement.

When writing to one of the leaders of Lutheranism, Erasmus wrote:

“I know nothing of your church.

At the very least it contains people who will, I fear, overturn the whole system and drive the princes into using force to restrain good and bad alike.

The gospel, the word of God, faith, Christ and the Holy Spirit – these words are always on their lips.

Look at their lives and they speak quite another language.”

Later Erasmus would complain of the doctrines and morals of the Reformers:

“You declaim bitterly against the luxury of priests, the ambition of bishops, the tyranny of the Roman pontiff and the babbling of the sophists (teachers of philosophy), against our prayers, fasts and masses.

You are not content to retrench the abuses that may be in these things, but must needs abolish them entirely.

Look around on this “evangelical” generation, and observe whether amongst them less indulgence is given to luxury, lust or avarice, than amongst those whom you so detest.

Show me any one person who by that Gospel has been reclaimed from drunkenness to sobriety, from fury and passion to meekness, from reviling to well-speaking, from wantonness to modesty.

I will show you a great many who have become worse through following it.

The solemn prayers of the Church are abolished, but now there are very many who never pray at all….

I have never entered their conventicles,(churches) but I have sometimes seen them returning from their sermons, the countenances of all of them displaying rage, and wonderful ferocity, as though they were animated by the evil spirit….

Who ever beheld in their meetings any one of them shedding tears, smiting his breast, or grieving for his sins?

Confession to the priest is abolished, but very few now confess to God.

They have fled from Judaism that they may become Epicureans (those who do not believe in superstitution or divine intervention).”

“Would a stable mind depart from the opinion handed down by so many men famous for holiness and miracles, depart from the decisions of the Church, and commit our souls to the faith of someone like you who has sprung up just now with a few followers?

The leading men of your flock do not agree with you or among themselves – indeed you don´t even agree with yourself, since in this same assertion you say one thing in the beginning and something else later on, recanting what you said before.”

“You (Luther) stipulate that we should not ask for or accept anything but Holy Scripture, but you do it in such a way as to require that we permit you to be its sole interpreter, renouncing all others.”

“I detest dissension because it goes against the teachings of Christ and against a secret inclination of nature.

I doubt that either side in the dispute can be suppressed without grave loss.”

Zwingli would meet with Erasmus when the Dutchman was in Basel between August 1514 and May 1516, having studied the older man´s writings during Zwingli´s years in Glarus and Einsiedeln.

Erasmus would have a great influence on Zwingli´s relative pacifism and his subsequent focus on preaching when he began his work in Zürich, but as sympathetic as Zwingli was to Erasmus´ approach to reform via independent scholarship and seeking to change the Catholic Church from within, Zwingli did not see the danger that Erasmus saw this division in the Church would mean.

And this would cost Zwingli his life and the lives of millions of others.

A childhood begun in the shadow of war would lead to a life that would be ended by war.

I would begin my exploration of Huldrych Zwingli in the place of his birth…..

(To be continued)

Sources: Wikipedia / Google