Landschlacht, Switzerland, 22 November 2017

I have just returned home from the dentist (one more tooth less) and I find that listening to Franz Liszt´s Hungarian Rhapsodies seems to keep pace with the throbbing pain experienced inside my mouth, as if each tooth is an ivory piano key pressed upon in tempo with the music being produced by pianist Georges Cziffra.

Above: The flag of Hungary

As if to mock me, the weather outside, though seasonably cold, is astonishingly beautiful and invites exploration, but I am later committed to teaching this afternoon, toothache or sunny day be damned.

Liszt listening has become my latest hobby as I keep stumbling across his name in my travels: he visited Weesen, his daughter Cosima was conceived in Como and later born in Bellagio when he visited the town with his lover and mistress the Comtesse Marie d´Agoult.

Above: Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886)

He also spent time in other places I have visited, like Budapest, Paris, Rome, Sopron, Vienna and Zürich.

(More on Weesen later in this blog…)

(Clearly Liszt must make a future contribution to this blog.)

Facebook recently drew my attention to a Swiss Info article of three days ago that says, for the first time, Switzerland has two million foreigners living in its midst, which accounts for nearly 25% of the nation´s 8.3 million population.

More than 80% of the foreigners living in Switzerland are from European countries, with half of these coming from Italy, Germany, France and Portugal.

(The latter does bring sense to Swiss philosophy teacher-writer Pascal Mercier´s Night Train to Lisbon.)

Above: Poster from the film adaptation starring Jeremy Irons (2013)

These non-Swiss, of whom I am one, are often the subject of huge political debate especially by the current xenophobic government party, the SVP (the Schweizer Volks Partei or Swiss People´s Party).

The big issue, of course, is:

Will all these pesky foreigners and their foreign ideas change the character of the place?

This effect of an alien group affecting the area they choose to alight upon was much on my mind the day my wife and I visited Bellagio….

Bellagio, Italy, 3 August 2017

Women worry too much.

Too many of them are convinced that their men remain with them only because they have been able to maintain the illusion of youth, and that once the spell has been broken by the inevitable passage of time fickle men will trade them in for newer models.

Nevertheless there remains good men, men who fall in love with a woman´s character and inner beauty that no horrid hourglass, no mere mirror could ever alter.

For these men, a woman´s beauty is eternal.

Only women can really judge how many of these men there actually are.

I have tried to be a man worthy of the title.

My wife´s birthday, a deeply guarded secret and not a cause for celebration despite my desires to celebrate her life and its importance to my own, finds us in Bellagio, a northern Italian town famous for both its location and the visitors attracted to it over the centuries.

Above: Bellagio

Bellagio sits at the peak of the Larian Triangle, the peninsula that divides Lake Como into two arms of an inverted Y, and looks across at the northern trunk of the Lago and behind this the Alps extending from Switzerland.

Bellagio is luxury itself with a myriad of trees, including the laurel tree from which the peninsula gets its name, and flowers favoured by a mild and sweet climate.

The Borgo, the historic centre of Bellagio, lies southwest of the promontory tip between hilltop Villa Serbelloni and Como´s southwest arm.

Beyond the Serbelloni are a park and a marina.

Parallel to the shore are three streets: Mazzini (after Italian author and politician Giuseppe Mazzini), Centrale and Garibaldi (after Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi) in ascending order.

Cutting across them to form a sloped grid are seven medieval stone staircases running uphill.

The Basilica of San Giacomo and the Torre delle Arti Bellagio (the last remnant of medieval defences) sit in a piazza at the top.

Above: The Basilica of San Giacomo

There have been signs of humanity around Bellagio since 30,000 years ago, but only in the 7th to 5th centuries before Christ did there appear a place of worship and exchange upon the promontory.

The first identifiable inhabitants of Bellagio, from 400 BC, were the Insubres, a Celtic tribe.

The Insubres lived free and independently until the arrival of the Gauls, led by Belloveso, around 600 BC, whom they replaced or intermarried.

The Gauls created a garrison at the extreme point of the promontory, Bellagio, after their commander Belloveso.

(Another theory is that Bellagio was originally Bilacus – in Latin, “between the lakes”)

In 225 BC, the territory of the Gauls was occupied by the Romans in their gradual expansion to the north.

The Romans, led by consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus, defeated the Gauls in a fierce battle near Camerlata.

Gaulish hopes of independence were raised by an alliance with Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but dashed by defeat in 104 BC and absorbed into a Roman province in 80 BC.

Bellagio became both a Roman garrison and a point of passage and wintering for the Roman armies on the way to the Splügen Pass.

Troops wintered at the foot of the promontory, sheltered from north winds and the Mediterranean climate.

In the early decades of the Roman Empire, two great figures brought fame to the Lake and Bellagio: Virgil and Pliny the Younger.

Virgil, the Latin poet, visited Bellagio and remembered the lake in his second book of the Georgics.

Above: Publius Vergilius Maro, aka Virgil (70 – 19 BC)

Pliny the Younger, resident in Como for most of the year, had, among others, a summer villa near the top of the hill of Bellagio, known as “Tragedy”, which he described in a letter the long periods he spent there not only studying and writing but also hunting and fishing.

Above: Statue of Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus aka Pliny the Younger (61 – 113 AD), Cathedral of Santa Maria Maggiore, Como

In 9 AD, the Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus passed through Bellagio en route to the Splügen Pass then onwards to Germany against Arminius.

They were annihilated in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, near present day Osnabrück, Germany.

At the time of the barbarian invasions, Narses, a general of Justinian, in his long wanderings through Italy waging war, created along Lake Como a fortified line against the Gauls.

Nevertheless, around 568 the Lombards, led by Alboin, poured into the Po Valley and settled in various parts of Lombardy, in the alpine Valleys and along the lakes.

With their arrival in Italy, the Franks of Charlemagne descended on Lombardy through the high Alps and defeated the Lombards in the Battle of Pavia (773).

The suzerainty of the Frankish kings was followed by the rule of the Ottonian dynasty of Germany.

By 1100 Bellagio was already a free commune and the seat of a tribunal.

In 1154, under Frederick Barbarossa, Bellagio was forced to swear loyalty and pay tribute to Como.

Towards the end of the 13th century, Bellagio, which had participated in numerous wars, became the property of the House of Visconti and was integrated into the Duchy of Milan.

With the death of Filippo Maria, the House of Visconti lost power.

For a short time the area was transformed into the Ambrosian Republic (1477 – 1450), until Milan capitulated to Francesco Sforza, who became Duke of Milan and Lombardy.

In 1535, when Francisco II Sforza, the last Duke of Milan, died, then began two centuries of Spanish rule.

Favoured by Bellagio´s ideal position for transport and trade, various small industries flourished, most notably candle making and silk weaving

During the brief Napoleonic period, the port of Bellagio assumed military and strategic importance and Count Francesco Melzi d´Eril established his summer home here.

Above: Villa Melzi d´Eril, Bellagio

Melzi proceeded to build his magnificent Villa, bringing to the area the flower of the Milanese nobility and the promontory was transformed into a most elegant and refined court.

(For more on the Villa Melzi, please see Canada Slim and the Holiday Chronicles of this blog.)

The fame of the lakeside town became well known outside the borders of the Kingdom of Lombardy – Venetia.

Emperor Francis I of Austria visited in 1816 and again in 1825.

Stendhal first visited Bellagio in 1810:

Above: Marie-Henri Beyle aka Stendhal (1783 – 1842)

“What can one say about ……Lake Como, unless it be that one pities those who are not badly in love with them…..

The sky is pure, the air mild, and one recognises the land beloved of the gods, the happy land that neither barbarous invasions nor civil discords could deprive of its heaven-sent blessings.”

At Bellagio he was the guest of Melzi d´Eril, from whose Villa he wrote:

“I isolate myself in a room on the second floor. There, I lift my gaze to the most beautiful view in the world, after the Gulf of Naples.”

In January 1833, the 21-year-old Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt met Comtesse Marie d´Agoult, a Parisian socialite six years his senior.

Above: Author Marie d´Agoult (pen name: Daniel Stern)(1805 – 1876)

She had been married since 1827 to Comte Charles d´Agoult and had borne two daughters, but the marriage had become sterile.

Drawn together by their mutual intellectual interests, Marie and Franz embarked on a passionate relationship.

In March 1835 the couple fled Paris for Switzerland.

Ignoring the scandal they left in their wake, they settled in Geneva where, on 18 December 1835, Marie gave birth to a daughter, Blandine-Rachel.

In the following two years Liszt and Marie travelled widely in pursuit of his career as a concert pianist.

Franz and Marie d´Agoult stayed for four months in Bellagio in 1837.

Here, on Christmas Eve 1837, in a lakeside hotel in Bellagio, a second daughter was born, named Francesca Gaetana Cosima.

It is as “Cosima” that the child would become known.

In Bellagio, Franz wrote many of the piano pieces which became Album d´un Voyageur, which later became landscapes seen through the eyes of Byron and Senancour.

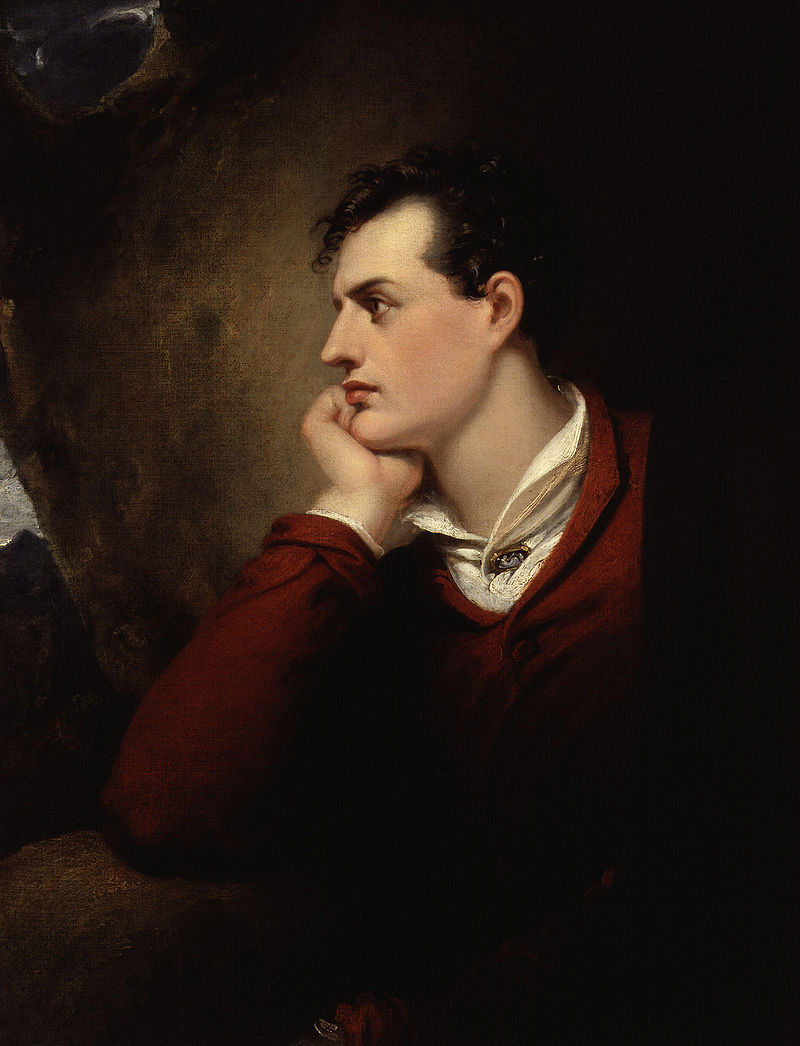

Above: Lord George Gordon Byron (1788 – 1824)

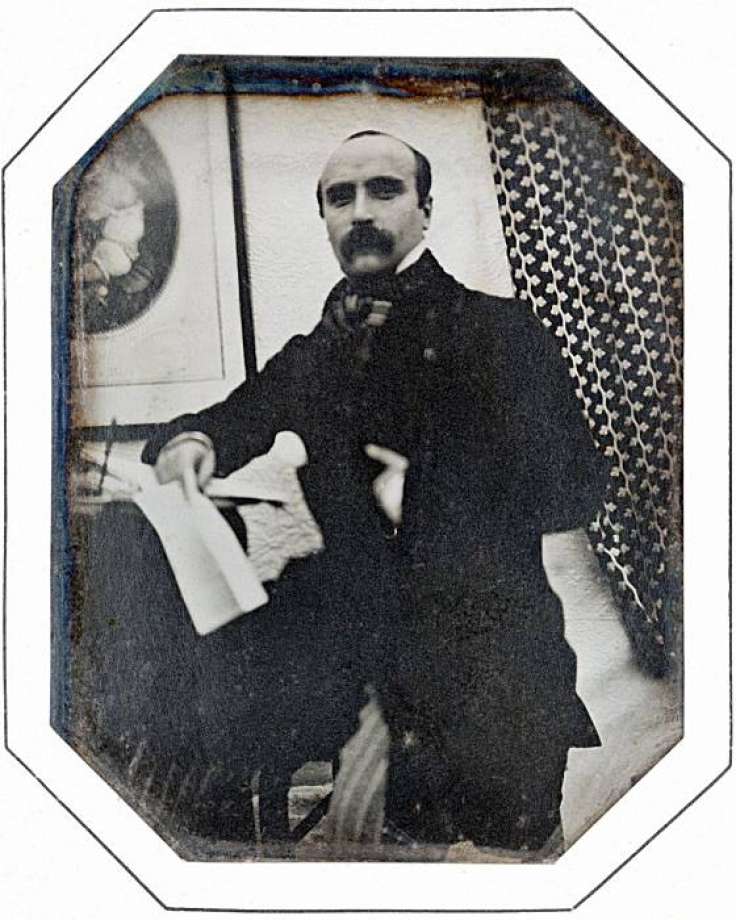

Above: Étienne Pivert de Senancour (1770 – 1846)

These works contributed much to the image of Bellagio and Lake Como as a site of romantic feeling.

The Comtesse´s letters show that they were sadly aware of drawing an age of motorised tourism in their train.

Franz and Marie continued to travel in Europe.

Their third child and only son, Daniel, was born on 9 May 1839 in Venice.

That same year, while Franz continued his travels, Marie took the social risk of returning to Paris with Blandine and Cosima.

Marie´s hopes of regaining her social status in Paris were denied when her influential mother, Madame de Flavigny, refused to acknowledge the children.

Marie would be socially shunned while her daughters were clearly in evidence.

Franz´s solution was to remove the girls from Marie and place them with his mother Anna in her Paris home.

By this means, both Marie and Franz could continue their independent lives.

Relations between the couple cooled, and by 1841 they were seeing little of each other.

They were both engaged in their own affairs.

In 1838, Bellagio received with all honours the Emperor Ferninand I, the Archduke Rainer and the Minister Metternich, who came from Varenna (on the east shore of Como north of Bellagio) on the Lario, the first steamboat on the Lake, launched in 1826.

Bellagio was much frequented by the nobility and saw the construction of villas and gardens.

Luxury shops opened in the village and tourists crowded onto the lakeshore drive.

Gustav Flaubert visited Bellagio in 1845.

Above: Gustave Flaubert (1821 – 1880)

He told his travel diary:

“One could live and die here. The outlook seems designed as a balm to the eyes….

The horizon is lined with snow and the foreground alternates between the graceful and the rugged – a truly Shakespearean landscape, all the forces of nature are brought together with an overwhelming sense of vastness.”

In 1859, Bellagio became part of the Kingdom of Italy until 1943 when Germany created the Italian Social Republic under Benito Mussolini.

Bellagio was part of the Italian Social Republic until 1945.

The Futurist writer and poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, a Mussolini loyalist who had helped shape Fascist philosophy, met his death from a heart attack in Bellagio in December 1944.

Above: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876 – 1944)

Since the end of the Second World War, Bellagio has degenerated into a place of mass tourism.

There are at least seven churches in the area where the visitor can recite the Lord´s Prayer, beseeching God that he/she be not lead into temptation.

For beauty can lead to temptation, here in this cradle between cypress-spiked hills, with promenades planted with oleander and limes, fin de siecle hotels painted in pastel shades of butterscotch, peach and cream, steep cobbled streets and secret alleyways.

This village lined with upmarket souvenir shops, piped music and scandalous swimwear worn by carefree sun worshippers enjoying the days of summer in the waters of the Lido.

This is not a local´s village.

Here one finds money in all of its denominations from old money sitting silently in mute accounts and spent on old patrician houses that line the banks of the promontory, to new money unashamedly exposed and spent carelessly in boutiques and fancy hotels.

This is not a local´s village.

Just behind the hill of the promontory, protected from the winds of change, sits the Villa Serbelloni, which dominates the town´s historic centre.

Above: Villa Serbelloni, Bellagio

Serbelloni was built in the 15th century in place of an old castle razed in 1375, and has been rebuilt several times.

In 1798 it came into possession of Alessandro Serbelloni (1745 – 1826) who enriched it with precious decorations and works of art of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In 1905, the Villa was transformed into a luxury Hotel, which still offers the well-to-do their own private jetty, beach, tennis courts, fitness centre, sauna, poolside restaurant and beauty farm as just some of the luxurious facilities available.

In 1959, it became the property of the Rockefeller Foundation of New York.

Since then, the Bellagio Center in the Villa has been home to international conferences, held by American scholars, housed in the Villa.

This is not a local´s Villa.

Today the visitor can visit only the gardens, while trails lead to the remains of a 16th century Capuchin monastery.

The gardens of Serbelloni resemble a woodland where paths spacious invite strolls amongst oaks, firs, osmanti, myrtles, junipers and pines which shade confidences and confidently screen against storms.

Outside these gardens of lost Eden, the locals quietly enjoy rowing and football at the Bellagio Sporting Union, eat tóch (polenta mixed with butter and cheese), share red wine from communal jugs, and enjoy miasca, pan mein, and paradel for dessert.

At least this is what the tourists are taught that the locals do.

No one meets the locals.

Service to the foreigner is, more often than not, provided by other foreigners.

No one comes to Bellagio in search of Italy, but rather in search of a sort of sexual electricity that is produced by foreigners mingling with other foreigners in a Mediterranean Babel and babble of intertwining nationalities and languages.

Some foreigners reside here, retire here and some even respire here, for Bellagio even has a small cemetery for foreigners.

Here lies Nellie, 25, the wife of Arthur Charles Parkinson of London, who died here after only 10 days of marriage on 10 June 1895.

Nearby lies Sidney Brunner, of Nennington, Cheshire, 23, who lost his life saving his older brother from drowning on 8 September 1890.

Why wife and brother were left to rest in peace in an isolated forgotten cemetery in Bellagio rather than back in England, posterity does not record.

The wife and I do as the other tourists do: we eat in cafés, we shop in boutiques, we wander the streets, we linger at the Lido.

There is beauty here in Bellagio but it feels purchased, artificial, imported.

A few hours here and we feel no impulse to linger.

We let the rich be rich and the tourist be complacent in his superiority.

There is life beyond Bellagio, richer in quality and more beautiful in substance than this pastel Paradise.

We create and carry with us our own sexual electricity.

We don´t need Bellagio for this.

“Oz never did give nothing to the Tin Man that he didn´t already have.”

Sources: Wikipedia / The Rough Guide to Italy / Lonely Planet Italy / America, In the Country, “Tin Man”