Landschlacht, Switzerland, 18 December 2017

Battlefields can be deceptive when viewed long after the battles have been fought.

Take the example of Waterloo.

Above: The Battle of Waterloo, Belgium, 18 June 1815

Once the tourist gets beyond the huge pyramid and the facilities set up to view and visit it he/she finds him/her self in quiet tranquil dairy country.

(For a glimpse of today´s Waterloo, please see That Which Survives: A Matter of Perspective of this blog.)

Go to Battle, near Hastings, and beyond the markers that indicate that major events took place here in 1066 resulting in the Norman Conquest of England, it is difficult to picture these tranquil fields the scene of anything beyond a hiker´s pleasant place for a stroll.

Above: The Bayeux Tapestry, showing the Battle of Hastings, England, 14 October 1066

Yes, even today a few poppies grow between the crosses row by row in Flanders Field, the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting in World War One.

And while no birds sang back then, today ignorant avian creatures soar and swoop above farmers´ fields that have known the plow for centuries before and will probably know the plow for centuries to come.

It is difficult to understand the past through the eyes of the present.

It is difficult to understand the people of the past through our present perspectives.

As a resident in Switzerland these past seven years I find myself still waging an internal war within, between my preconceptions of the Swiss before I lived here and the reality and the history of who the Swiss actually are and how they got that way.

I once viewed the Swiss as nothing more than banking gnomes with the passion of dry toast, similar to the goblins that run Gringot´s Bank in the Harry Potter series.

My view later expanded to see the Swiss through the eyes of Johanna Spyri´s children´s classic Heidi and I began to imagine the rural Swiss as hayseed farmers leading processions of bell-ringing bovine over hills reminiscient of Salzburg, Austria, where Julie Andrews reminds us that those hills are alive with the Sound of Music.

Above: Swiss CHF50 commemorative coin (2001)

To be fair, Switzerland does indeed have bankers and farmers that partially validate my preconceptions, but the Swiss are so much more than these.

If we consider that two symbols of Switzerland are the Swiss Army knife and the Swiss Guard that protects the Pope, it might help us to view the Swiss militarily as well.

Today we view Switzerland simply as a place where conflicting groups go to Geneva, have a little chocolate, discuss a bit of politics, shake hands and sign treaties.

We forget that once the Swiss were considered the world´s fiercest warriors and that warring nations eagerly bought their mercenaries from Switzerland, for even then: Swiss meant quality.

We forget that had it been in Swiss nature to be conquerors beyond their frontiers and had they acted when they held military superiority, today´s political map might look quite different.

Little did I know as I followed the footsteps of religious reformer Huldrych Zwingli that I would encounter the very events that would determine Swiss independence from Hapsburg rule, compel the country to adapt a policy of neutrality and redefine the role of the Swiss mercenary.

Above: Huldrych Zwingli (1484 – 1531)

Glarus, Switzerland, 15 November 2017

The walk continues.

My little Zwingli Project begun a month previously has brought me here, back to the Walensee, a beautiful lake – 24.1 square kilometres of mysterious water that never fails to capture one´s breath.

Above: Walensee and Kerenzerburg Mountain

I had already walked from Zwingli´s birthplace in Wildhaus to Strichboden (13 km / 4 hours walk), to Arvenbüel (9 km / 3 hours walk), to Weesen (five km / 2 hours walk) and had learned and seen a lot.

(See Canada Slim and the Road to Reformation, ….and the Wild Child of Toggenburg, ….and the Thundering Hollows, ….and the Basel Butterfly Effect, ….and the Vienna Waltz for the events and background of the Zwingli Project in this blog.)

After a train to St. Gallen, another to Uznach and a third to Ziegelbrücke, followed by a bus to Weesen, I set off for Glarus, Zwingli´s first ecclesiastical post.

I walked past Weesen Harbour, the path clinging to the shoreline of the Walensee.

Above: Harbour, Weesen, Walensee

Summer had clearly abandoned the lake: no boats afloat, no campfires burning, no kiosks surrounded by clamouring kids.

I saw only the occasional woman or retired gentleman walking their dogs.

The path left the lake, climbed to the highway leading to Ziegelbrücke, clung to a bridge crossing the Linth Canal that goes to where the Promised Land of Zürich beckons, descended back to the lake through a campground to a second canal – the Escher.

I followed canal and towpath straight south, but less than a kilometre later the signage and my travelling companion guidebook failed me.

There were no signs and as beautiful as the ascent and the walk atop the mountains could have been, I lacked important information:

Were there cable cars, up the mountains, then, after hours of walking, back down the mountains, operating?

It was a workday and summer had long since passed.

If there were cable cars in operation, how passable were the mountains?

Were the paths blocked by snow?

Were trail markings still visible?

I decided to err on the side of caution and continued to follow the Escher Canal.

My guidebook ultimately leads the hiker to Glarus and my topographic map suggested the Canal continued straight south to Glarus, so – mountain views be damned – from the Canal I would not stray.

The territory I was walking through wasn´t so alien for me.

I had previously walked from where the Escher Canal (which manages the Linth River) begins in Linthal to Glarus.

I had taken a cable car from Linthal to visit the cars-free town of Braunwald.

Above: The village of Braunwald

I had ridden a Postbus from Linthal to Klausenpass and the Uri cantonal capital Altdorf.

Above: Klausen Pass

And to accomplish these adventures to and from Glarus and Linthal I had ridden the train a number of times from Ziegelbrücke.

(For a glimpse of this, please see Glarus: Every Person a Genius of this blog.)

According to the legend, the inhabitants of the Linth River valley were converted to Christianity by the Irish monk St. Fridolin, who, after founding Säckingen Abbey in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, decided to keep travelling and keep on converting those he met during his travels.

In Switzerland, Fridolin spent considerable time where he converted the landowner Urso.

Above: Fridolin (left), Urso (middle) and Landolf (right). Urso´s brother Landolf protests against his brother´s landholdings being passed to Fridolin, so Fridolin resurrects Urso to confirm the land grant.

On his death Urso left his enormous landholdings to Fridolin, who founded numerous churches all dedicated to St. Hilarius (the origin of the name “Glarus”).

From the 9th century, the Glarus region was owned by Säckingen Abbey until the Habsburgs claimed all the Abbey’s rights by 1288.

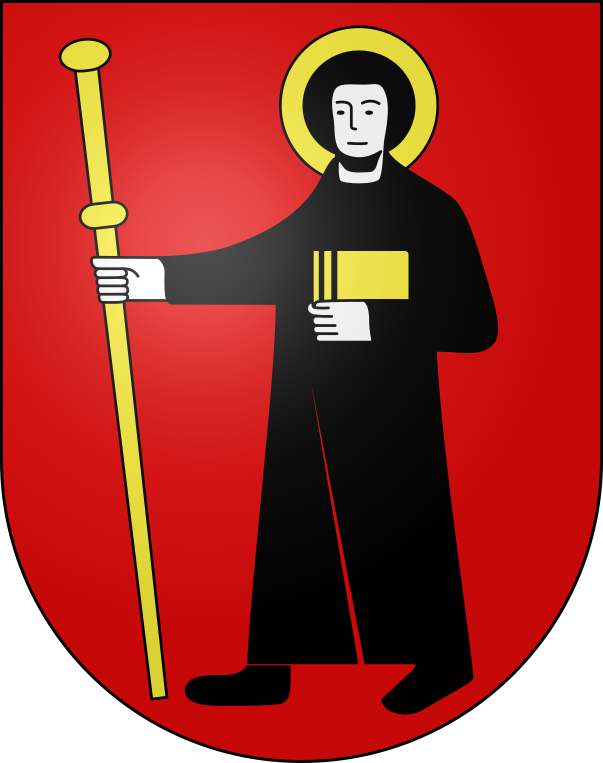

St. Fridolin has never been forgotten.

Canton Glarus joined the Swiss Confederation in 1352.

On 9 July 1386, the Swiss Confederation attacked and conquered the Habsburg village of Weesen.

The following year Canton Glarus rose up against the Habsburgs and destroyed Windegg Castle.

In response, on the night of 21-22 February 1388, a Habsburg army attacked the village of Weesen and drove out the Confederation forces.

In the beginning of April, two Habsburg armies marched out to cut off Canton Glaurus from the rest of the Confederation.

The main Confederation army, with about 5,000 men, marched towards Näfels under the command of Count Donat of Toggenburg and the knight Peter von Thorberg.

A second column, with about 1,500 men under the command of Count Hans von Werdenberg-Sargans, marched over the Kerenzerberg Pass above the Walensee.

Habsburgian attempts to reconquer the valley were repelled in the Battle of Näfels in 1388, where a banner depicting St. Fridolin was used to rally the people of Glarus to victory.

The main army, under Toggenburg and Thorberg, attacked and captured the fortifications around Näfels.

As they retreated, the Austrian army spread out to plunder the villages and farms.

The Glarners then emerged from the snow and fog to take the Habsburg troops by surprise as they were preoccupied with looting.

The Battle of Näfels, the last major battle of the Old Swiss Confederation vs the Austrian Hapsburgs, fought on 9 April 1388, was decisive, despite the forces of Glarus being outnumbered 16 to 1.

2,500 Austrians died.

Only 54 men of Glaurus were killed.

The disorganized Austrians broke and fled towards Weesen, but the collapse of the bridge over the Linth River dropped much of their army into the water where they drowned.

In 1389, a seven years´ peace treaty was signed in Vienna.

Above: Monument to the Battle of Näfels (9 April 1388)

That same year, the first Näfelserfahrt (Näfels pilgrimage) to the site of the battle was held.

This pilgrimage, which still occurs, happens on the first Thursday in April in memory of this battle.

From that time onwards Canton Glarus has used the image of St. Fridolin on its flags and in its coat of arms.

I lingered in Näfels after an hour´s stroll along the Escher Canal.

I visited the Glarus Cantonal Museum in the Freulerpalast (Freuler Palace), the Church of St. Hilarius with the grave of General Niklaus Franz von Bachmann (1740 – 1831) who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, and the Battlefield Memorial.

Above: Freuler Palace, Näfels, Canton Glarus

The diverse history of the Canton is shown here with precious objects and paintings.

Here you can learn interesting facts on immigration and emigration, the practice of direct democracy and the Great Fire of Glarus.

(On the first Sunday in May, the Landesgemeinde brings out traditionally clad voters who publicly debate and decide politics in a manner rarely seen elsewhere.)

Above: Landesgemeinde Glarus

You can see the development of textile printing that once was the most important industry in Glarnerland, the military and defence of Glarus and the significance of the region in alpine ski sport.

(The Museum is open from 1 April to 30 November, 1000-1200/1400-1730. Please see www.freulerpalast.ch.)

The towpath along the Escher Canal continues to Netstal, a town that lies beneath Wiggis Mountain where the Löntsch River (from the Klöntal) meets the Linth.

Above: Netstal

Here one finds both a Catholic and a Reformed church, a beautiful half-timbered house (the Stählihaus), a plaque on the side of the Ambühlhaus in memory of Battle of Näfels warrior Mathias Ambühl, and a memorial stone regarding an unfortunate mine launcher accident that took place on 15 December 1941 resulting in the loss of four soldiers´ lives.

Netstal was home to cartographer Rudolf Leuzinger (1826 – 1896), the youngest Swiss traitor ever executed Fridolin Beeler (1921 – 1943) and writers Ludwig Hohl (1904 – 1980) and Marcel Schwander (1929 – 2010).

In the 118 years between the Battle of Näfels and Zwingli assuming his post as priest in Glarus in 1506, Switzerland was far from being a peaceful place, for when the Swiss weren´t fighting against others they were fighting amongst themselves.

There had been the Appenzell Wars (1403 – 1428), war with Milan (1403 – 1428), the Basel War (1409), the annexations of Aargau (1415) and Thurgau (1460), the Raron Affair (1418 – 1419), the Old Zürich War (1436 – 1450), the St. James War (1445 – 1449), the Freiburg War (1447 – 1448), the Waldshut War (1468), the Burgundian Wars (1474 – 1477), the St. Gallen War (1489 – 1490), the Italian Wars (1495 – 1522) and the Swabian War (1499).

(The Swabian War is called the Swiss War by the Germans and the Engadin War by the Austrians.)

(For the fascinating story of the Burgundian Wars and how it lead to the Swiss being recognized as the militarily superior force in Europe, please see The Underestimated: The Bold and the Reckless of this blog.)

Often these wars were of Cantons seeking independence from Habsburg control and the Habsburg Empire seeking to regain it.

Bloodshed and violence were commonplace.

As previously mentioned in former blog posts, Zwingli had completed his studies in Weesen, Bern, Basel and Vienna, was ordained in Konstanz and celebrated his first mass in his hometown of Wildhaus, before his first ecclesiastical post in Glarus where he would remain for a decade. (1506 – 1516)

Above: Birthplace of Huldrych Zwingli, Wildhaus

It was in Glarus, whose soldiers were used as mercenaries throughout Europe, that Zwingli became involved in politics.

The hiring of young men to fight in other nations´ wars, including battles for the Pope, was one of the major industries for the Swiss.

During Zwingli´s pastorate in Glarus, the Swiss Confederation was embroiled in various campaigns with its neighbours: the French, the Habsburgs and the Papal States.

Zwingli placed himself solidly on the side of the Roman See.

In return, Pope Julius II honoured Zwingli by providing him with an annual pension.

Above: Giuliano della Rovere (1443 – 1513), “the Fearsome Warrior Pope” Pope Julius II (1503 – 1513)

Zwingli took the role of chaplain in several Swiss campaigns of the aforementioned Italian Wars.

The Italian Wars (also referred to as the Great Italian Wars or the Great Wars of Italy or the Renaissance Wars) were a series of conflicts from 1494 to 1559 that involved, at various times, most of the city-states of Italy, the Papal States, the Republic of Venice, most of the major states of Western Europe (France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburg Empire, England, Swiss mercenaries and Scotland) as well as the Ottoman Empire.

The Italian Wars are: the First Italian War / King Charles VIII´s War (1494 – 1498), ….

Above: Charles VIII of France (1470 – 1498), King (1483 – 1498)

(Charles VIII of France invaded Italy with 25,000 men, including 8,000 Swiss mercenaries.)

….the Second Italian War / King Louis XII´s War (1499 – 1504), ….

Above: Louis XII of France (1462 – 1515), King (1499 – 1515)

(Louis XII of France invaded Italy with 27,000 men, including 5,000 Swiss mercenaries. Julius II became Pope in 1503.)

….the Third Italian War / the War of the League of Cambrai (1508 – 1516), ….

(The Pope hired 6,000 Swiss mercenaries in the War against the French.)

….the Italian War of 1521 – 1526, the War of the League of Cognac (1526 – 1530), the Italian War of 1536 – 1538, the Italian War of 1542 – 1546, and the Habsburg-Valois War of 1551 – 1559.

The attentive reader may note that I do not mention Swiss mercenary involvement in the last five Italian conflicts.

That is because three battles – one in King Louis´ War and two in the War of the League of Cambrai – would make the Swiss question themselves as regards to their military role and their allegiance to the Catholic Church.

While Zwingli was in Vienna, he probably had heard of the Treason of Novara in 1500.

King Louis XII of France had conquered the Duchy of Milan in 1499 with the help of Swiss mercenaries.

In the spring of 1500, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, in his turn hired Swiss mercenaries in his bid to reconquer the Duchy.

Above: Ludovico Sforza (1452 – 1508), Duke (1494 – 1499)

The two groups of Swiss mercenaries found themselves on both sides of a conflict.

The two mercenary armies confronted one another at Novara, a city west of Milan.

6,000 Swiss under the command of Sforza defended the city, while 10,000 Swiss under the command of Louis laid siege to it.

A meeting of delegates from the Swiss soldiers´ individual cantons called for negotiations between the two sides in an attempt to prevent the worst case scenario of the Swiss being forced to slaughter one another, “brothers against brothers and fathers against sons”.

Louis agreed to a conditional surrender which would grant free passage to the Swiss abandoning the city, under the condition that Sforza would be surrendered.

However, the Swiss on Sforza´s side, under an oath of loyalty to their employer, decided to dress Sforza as a Swiss and smuggle him out of town.

On 10 April 1500, the Swiss garrison was leaving Novara, passing a cordon formed by the Swiss on the French side.

French officers were posted to oversee their exit.

As the disguised Sforza passed the cordon, one Swiss mercenary Hans Turman of Uri made signs giving away Sforza´s identity.

Above: Sforza handed over to the French

The Duke was apprehended by the French and died eight years later as a prisoner in the castle of Loches.

Above: Loches Castle

The French rewarded Turman for his treason with 200 gold crowns (corresponding to five years´ salary of a mercenary).

Turman escaped to France, but after three years he returned home to Uri.

He was immediately arrested for treason and executed by decapitation.

The Treason left a mark on the Swiss conscience.

Were they nothing more than men without honour, selling themselves to the highest bidder?

Was Swiss unity so cheaply sacrificed?

I am uncertain as to the exact demands required of an army chaplain in Zwingli´s day, but I suspect that in spite of his religious role he was expected to raise arms against the enemy when it was required, for it was in battle in Kappel am Albis in 1531 that Zwingli would meet his demise and Zwingli´s most prominent statue – at Zürich´s Wasserkirche – shows him with sword firmly in hand.

Zwingli´s battle experiences would make him question the role of the Swiss as mercenaries which mainly enriched cantonal authorities.

On 6 June 1513, in the aforementioned city of Novara (Naverra) where the Swiss had gained the reputation of being treasonous, Zwingli was part of a force of some 12,000 troops that surprised the occupying French and soundly defeated them.

It was a shockingly bloody battle, with 5,000 casualities on the French side and 1,500 for the Swiss pikemen.

Above: The Battle of Novara, 6 June 1513

After the battle, the Swiss executed the hundreds of German Landsknecht mercenaries they had captured that had fought for the French.

Having routed the French army, the Swiss were unable to launch a close pursuit because of their lack of cavalry, but nonetheless several contingents of Swiss mercenaries followed the French withdrawl all the way to Dijon before the French paid them to leave France.

This one French defeat forced Louis XII to withdraw from Milan and Italy.

Did Zwingli witness these events and contemplate the morality of such actions?

The citizenry, Zwingli´s parishioners, remained loyal to the idea of fighting for the Pope until 13 September 1515….

16 km southeast of Milan is the town of Melegnano, then called Marignano.

This battle between the French and the Swiss would change everything.

The French army was composed of the best armored lancers and artillery in Europe and led by Francis I, newly crowned King of France and one day past his 21st birthday.

Above: Francis I of France (1494 – 1547), King (1515 – 1547)

With Francis were German Landknechts, bitter mercenary rivals of the Swiss for fame and renown in war, and late arriving Venetian allies.

Prior to Marignano there were years of Swiss successes, during which French fortunes in northern Italy had suffered greatly.

The prologue to the battle was a remarkable Alpine passage, in which Francis hauled 72 large cannons over new-made roads over the Col d´Argentiere, a previously unknown route on the French-Italian border.

Above: The village of Larche, France, and the Col d´Argentiere

This was, at the time, considered one of the foremost military exploits of the age and the equal of Hannibal´s crossing of the Alps in 218 BC.

At Villafranca, the French surprised and captured the commander of the Papal forces in a daring raid deep behind enemy lines, seizing Commander Colonna and his staff, 600 horses and a great deal of booty.

The capture of Prospero Colonna, along with the startling appearance of the French army on the plains of Piedmont, stunned the Papal allies.

Above: Prospero Colonna (1452 – 1523)

The Pope and the Swiss both sought terms with Francis, while the Pope´s Spanish allies en route from Naples halted to await developments.

The main Swiss army retreated to Milan, while a large faction, tired of the War and eager to return home with the profits of years of successful campaigning, urged terms with the French.

Though the parties reached an agreement that gave Milan back to the French, the arrival of fresh and bellicose troops from the Swiss cantons annulled the agreement, as the newly arrived men had no desire to return home empty-handed and refused to abide by the treaty.

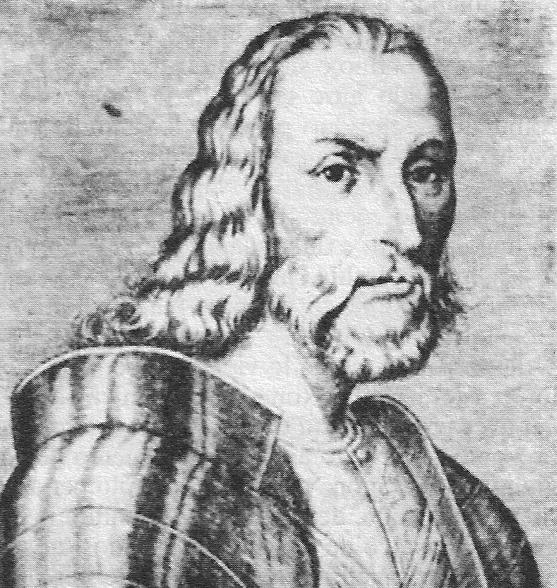

Discord swept through the Swiss forces until Matthäus Schiner, Cardinal of Sion and archenemy of Francis, inspired the Swiss with a fiery speech, reminding them of what a smaller Swiss army had achieved against as powerful a French army at the Battle of Novara.

Above: Matthäus Schiner (1465 – 1522)

Schiner pointed out the enormous profits of victory, appealed to national pride, and urged the Swiss to immediate battle.

The Swiss encountered Francis´ forces at the little burnt-out village of Marignano on a featureless plain.

A treaty signed, the French were not expecting battle.

Francis was in his tent, trying on a new suit of armor, when scouts reported the coming of the Swiss.

The French army quickly sprang into action.

The fighting, begun at sunset of 13 September, continued until smoke and the disappearance of moonlight halted the battle during the darkest hours of the night.

At dawn of 14 September the battle began again.

Above: The Battle of Marignano (13 – 14 September 1515)

The midmorning arrival of the French´s allies from Venice turned the tide against the Swiss.

Their attacks repulsed everywhere, their ranks in bloody shambles, the Swiss grudgingly gave ground and withdrew.

The battle was a decisive victory for Francis, for even though the Swiss were heavily outnumbered and outgunned, they had proved themselves during the preceding decades and had habitually emerged victorious from the most disadvantageous situations.

“I have vanquished those whom only Caesar vanquished” was printed on the medal Francis ordered struck to commemorate the victory.

Considering this battle his most cherished triumph, Francis praised Marignano as the “battle of giants” and stated that all previous battles in his lifetime had been “child´s sport”.

This battle ended once and for all Swiss aspirations for conquest.

There never was any Swiss military offensive against an external enemy again.

After lengthy negotiations, a peace treaty between the Swiss and the French was signed in Fribourg on 29 November 1516.

This treaty would be known as the Treaty of Perpetual Peace, a peace that remained unbroken until the French invaded Switzerland in 1798 during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Zwingli was present at the Battle of Marignano.

He would witness the slaughter of 6,000 of his countrymen in the service of the Pope.

Above: Dying Swiss, Retreat from Marignano, by Ferdinand Hodler (1898)

In Glarus, there had been political controversy on which side the young men seeking employment as mercenaries should take service, the side of France or the side of the Papal States.

They wanted to prevent that men of Glarus took service on both sides of the war as had been the case at Novara in 1500.

Zwingli had supported the Pope before the Battle of Marignano, and even after the Battle, he opposed the peace with France and continued to support the side of the Papal States.

Since public opinion in Glarus had shifted towards a clearly pro-French stance, Zwingli was forced to abandon his position in Glarus, taking employment elsewhere at Einsiedeln Abbey.

Above: Einsiedeln Abbey

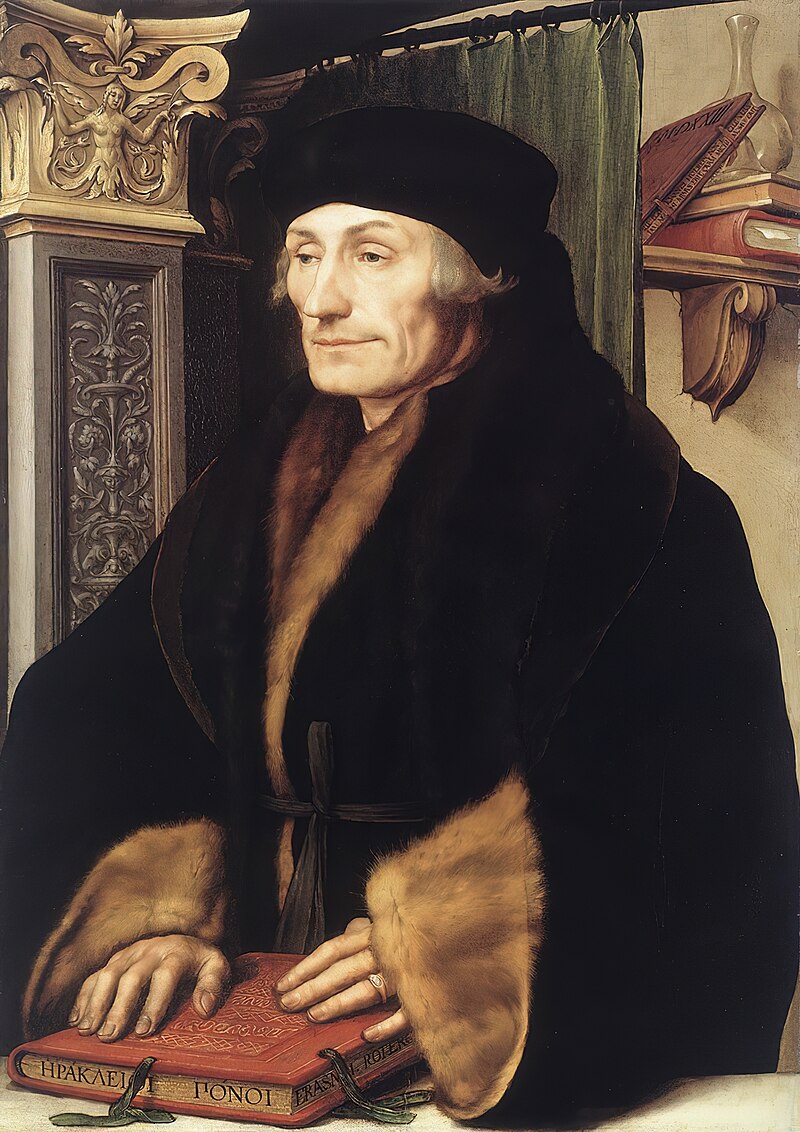

Based on his experience in the War, Zwingli became an outspoken opponent of mercenary service, arguing with Erasmus of Rotterdam that “war is sweet only to those who have not experienced it”.

Above: Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (1466 – 1586)

He returned from Marignano determined to abolish this mercenary practice of “selling blood for gold”.

Zwingli blamed the warmongery on the part of Cardinal Schiner for the disaster at Marignano and began to preach against the high clergy, the first sign of his radicalization that would culminate in the Swiss Reformation.

I continued to follow the Canal to the Canton Glarus capital also named Glarus.

Above: The City of Glarus

Of interest to the visitor are the Stadtkirche (city church), the Kunsthaus (art museum), the Anna Göldi Museum and the Cantonal library.

Above: Anna Göldi (1734 – 1782)

(Anna Göldi was the last person in Europe to be executed for witchcraft.)

(For the story of witchcraft in Switzerland, please see Five Schillings´ Worth of Wood of this blog.)

Though the Stadtkirche was once the church where Zwingli presided and is today a Reformed Church, there still seems to be no love lost for Zwingli.

Above: Stadtkirche, Glarus

I explored the church inside and out, but I could find no plaques or markers indicating that he had ever been here.

Glarus´ grudge towards Zwingli was neither forgiven nor forgotten.

Glarus was not shaped by Zwingli during his lifetime, but Glarus and Zwingli´s war experiences certainly shaped him.

I have always loved Glarus, this picturesque wee capital dwarfed by the looming Glarnsch Massif.

I have always loved Glarnerland, this tract of mountain territory with widely spaced settlements and very low-key tourism.

Isolation is attractive.

Sources: Wikipedia / Glarus Tourism / Josef Schwitter and Urs Heer, Glarnerland: A Short Portrait / Marcel and Yvonne Steiner, Zwingli-Wege: Zu Fuss von Wildhaus nach Kappel am Albis