Landschlacht, Switzerland, 22 December 2017

This week I returned back to work after being absent at home for the past two weeks.

It was a warm welcome with hugs and expressions of delight.

So much so that one witnessing customer commented:

“I want to work here!”

Back home after work:

First World problems.

Ah, the problem of having too many choices!

I don´t own (and happily don´t owe) much in this world.

What I possess is an (over)abundance of books and DVDs for a man of my modest income.

If I had to estimate I would say that I probably have at least 1,000 or more DVDs.

Of these I would safely say that there are only about a dozen films that I find myself watching again and again.

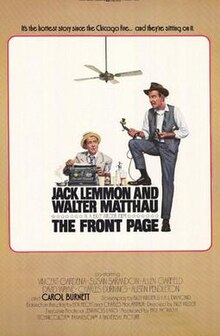

For example, I recently watched for the nth time the 1974 Billy Wilder film The Front Page starring Jack Lemmon and Walter Mathau.

Director Wilder, a newspaperman in his younger days recalled:

“A reporter was a glamourous fellow in those days, the way he wore a hat and a raincoat and a swagger, and had a camaderie with fellow reporters and with local police, always hot on the trail of tips from them and from the fringes of the underworld.”

Wilder set the movie in 1929, because the daily newspaper was no longer the dominant news medium in 1974.

(Even less so in 2017….)

The movie has reminded me of the old idea that there are basically only two types of people: those who make the News and those who follow the News.

Those who are remembered by history are those who have made history, who have made the News.

And if there is one place where a person´s legacy seems to matter is within the confines of a famous cathedral.

The decision to create a mausoleum or memorial for a person is determined by what the person accomplished in their life.

Especially for the Christian West it seems the bigger the mausoleum, the grander the grave, the more remarkable the memorial, the more attention and recognition is paid (or should be paid) to the legacy a person left behind.

The downside of this thinking is the presumption that those without a mausoleum, those lacking a memorial, those without a grave, must then be undeserving of respect, unworthy of memory, unloved and forgettable.

First World thinking and materialist obsessiveness carry on even beyond one´s life and onwards in the legacy of those who no longer live.

This kind of thinking was quite evident in our visit to London in October….

London, England, 24 October 2017

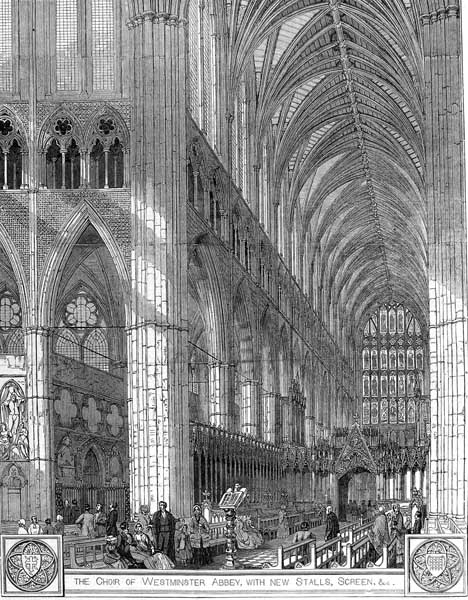

The Houses of Parliament overshadow a much older neighbour, Westminster Abbey.

Westminster Abbey has stood in London longer than any other building and embodies much of the history of England.

It was so named to differentiate it from the “east minster“, St. Paul´s Cathedral.

It is the finest Gothic building in London, the most important religious building in England, with the highest nave of any English church.

Over the centuries Westminster Abbey has meant many things to many people.

The Abbey has been the venue for every Coronation since the time of William the Conqueror (1028 – 1087)

It has been the site of every royal burial for some 500 years between the reigns of Henry III (1207 – 1272) and George II (1683 – 1760).

Scores of the nation´s most famous citizens are honoured here and the interior of the Abbey is cluttered with hundreds of monuments, reliefs and statues.

With over 3,300 people buried beneath the Abbey´s flagstones and countless others commemorated here, Westminster is, in essence, a massive mausoleum, more tourist attraction than house of God.

Would a modern day Jesus´ visit to this temple result in His repeating:

Above: Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco)

“Make not My Father´s house a house of merchandise.” ?

Would the Black Adder of the first BBC series wherein his father makes him the Archbishop of Canterbury (Episode 3)(transplanted to today) gleefully rub his hands together at all the modern wealth to be generated by the faithful and the curious?

Above: Tony Robinson / Baldrick (left), Tim McInnery / Lord Percy Percy (middle), and Rowan Atkinson / The Black Adder / Prince Edmund / The Archbishop of Canterbury

“Holy Moses! Take a look!

Flesh decayed in every nook!

Some rare bits of brain lie here,

Mortal loads of beef and beer.”

(Amanda McKittrick Ros, “Visiting Westminster Abbey”)

No one knows exactly when the first church was built on this site, but it was well over a thousand years ago.

At its genesis, this area was a swampy and inhospitable place on the outskirts of London.

The church stood on an island called Thorney Island, surrounded by tributaries of the River Thames.

In 960, Dunstan, the Bishop of London, brought 12 Benedictine monks from Glastonbury to found a monastery at Westminster.

Above: Dunstan (909 – 988)

One hundred years later King Edward the Confessor founded his church on the site.

Above: Edward the Confessor of England (1003 – 1066), King (1042 – 1066)

Edward was driven from England by the Danes.

During his exile in Normandy, Edward vowed that if his kingdom was restored to him, he would make a pilgrimage to Rome.

When Edward did eventually reclaim his throne in 1042, there was so much unrest in the kingdom that he was advised not to make the perilous journey in case a coup occurred while he was away.

The Pope absolved Edward of his vow on condition that he raise or restore a church in honour of St. Peter.

Edward´s Abbey was consecrated on 28 December 1065, but the King was too ill to attend.

He died a few days later and was buried before the high altar.

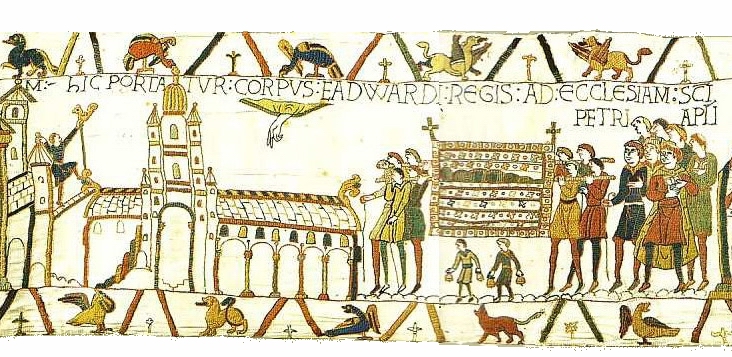

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts Edward´s body being carried into the Abbey for burial.

After Edward´s death his reputation as a holy man grew.

Miracles were said to have occurred at his tomb.

In 1161, Edward was made a saint.

King Henry III held the Confessor in such reverance that he resolved to build a new shrine for Edward in a yet more glorious church.

Above: Henry III of England (1207 – 1272), King (1216 – 1272)

The new church was consecrated on 13 October 1269.

In 1539, England´s monastries faced a crisis.

Henry VIII had fallen out with the Pope because the Pope refused to annul the King´s marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Above: Henry VIII of England (1491 – 1547), King (1509 – 1547)

Henry declared himself supreme head of the Church of England.

In 1540, Henry dissolved the monasteries and seized their assets.

Westminster Abbey fared better than most religious houses, because of its royal connections, so instead of being stripped and aband0ned it was refounded as a cathedral, with a Bishop and a Dean.

In 1553 Queen Mary succeeded Henry´s son, Edward VI, and Roman Catholicism became once more the approved religion.

Above: Mary I of England (1516 – 1558), Queen (1553 – 1558)

Mary made the Abbey a monastery again and the monks returned.

Her successor, Queen Elizabeth I, who came to the throne just five years later, in 1558, reversed Mary´s changes and refounded the Abbey yet again, this time with a Dean and a Chapter.

Above: Elizabeth I of England (1533 – 1603), Queen (1553 – 1603)

The Dean was answerable to no one but herself as sovereign, and it is in this form, not subject to the jurisdiction of a Bishop, as are most churches, but as a special church under the Queen – an institution known as a Royal Peculiar.

During the English Civil War, which culminated in the execution of Charles I and the establishment in 1649 of Oliver Cromwell´s Commonwealth, the Abbey was damaged when Puritans smashed altars, destroyed religious images and the organ, and seized the crown jewels.

Above: Oliver Cromwell (1599 – 1658), Lord Protector (1553 – 1558)

The Puritans were keen to rid the Abbey of all symbols of religious “superstition”.

Although the Abbey escaped wanton destruction better than many churches, it still bears the scars to this day.

The Abbey faced new peril during the Second World War.

Westminster miraculously survived, although bombs destroyed parts of it.

Walk with me through the Abbey.

Edward the Confessor´s church was the first in England to be built in the form of a cross, with the North and South Transepts forming its arms.

Most visitors, as did my wife and I, enter the Abbey via the North Transept.

The first impression one gets is of the soaring height of the vaulting.

At 102 feet, it is the highest in Britain.

The rose window above the entrance dates from 1722 and depicts the Apostles, excluding Judas Iscariot.

The rose window in the opposite transept depicts a variety of religious and other figures.

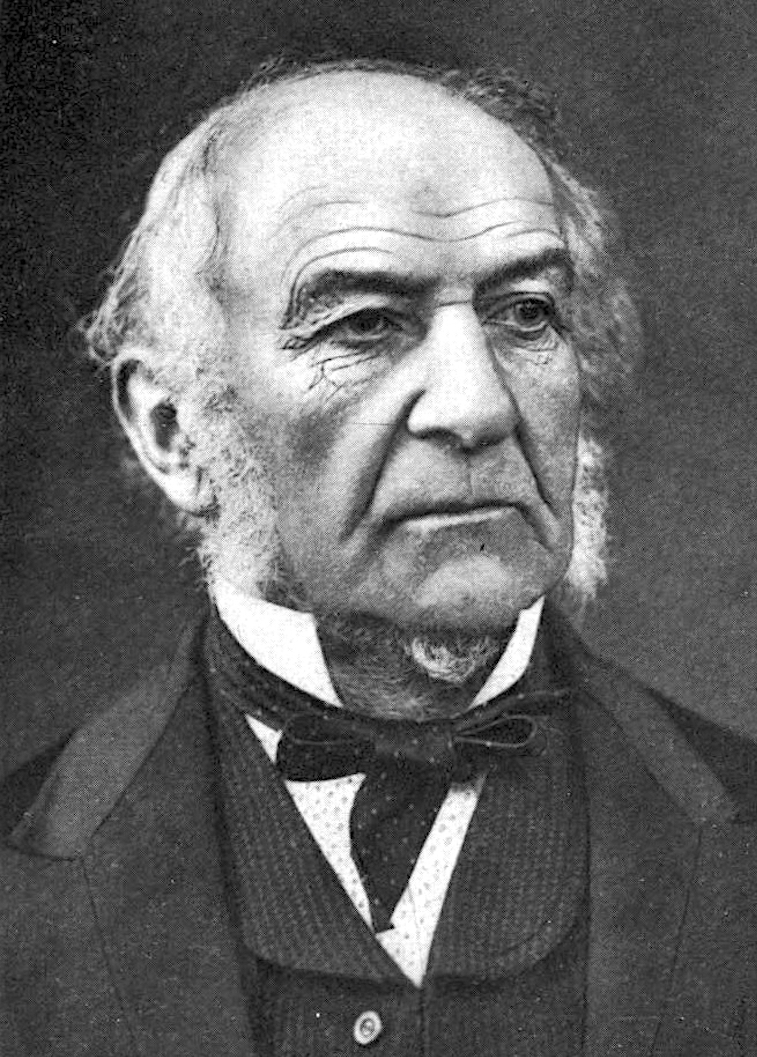

The North Transept is also known as the Statesmen´s Aisle, because it is littered with overblown monuments to long-forgotten empire builders and 19th century politicians, including Prime Ministers Viscount Palmerston (1784 – 1865), Robert Peel (1788 – 1850), Benjamin Disraeli (1804 – 1881) and William Gladstone (1809 – 1898) who are buried nearby.

Above: William Gladstone (1809 – 1898), UK Prime Minister (1868 – 1874 / 1880 – 1885 / 1886 / 1892 – 1894

Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder (1708 – 1778) is featured in a 30-foot memorial, buried alongside his son Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759 – 1806), who became Prime Minister at the age of just 24 and whose monument is over the Abbey´s west door.

Above: William Pitt the Younger (1759 – 1806), Prime Minister (1783 – 1806)

The North Transept leads down to the crossing – the centre of the church.

To the west is the Quire – an intimate space forming essentially a church within a church.

This was where the monks worshipped and this is where the Choir sits for the eight regular Choral Services (Matins, Holy Communion (4x), Eucharist, Evensong and Evening Service) each week.

The Choir consists of 12 men, known as Lay Vicars, and 24 boys, who come from the Abbey´s own choir School, now the only school in England exclusively for the education of choristers.

In the Middle Ages the Quire was the scene of a horrible murder.

In those days criminals could seek sanctuary in the Abbey.

Once they were within the walls, the law could not reach them.

But in 1378 fifty of the King´s men, ignoring the right of sanctuary, chased a prisoner into the Quire.

One of the soldiers “clove his head to the very brains” and also killed a monk who tried to rescue the poor man.

From the Statesmen´s Aisle, go straight to the central Sanctuary, site of the royal coronations.

Look down at the floor.

This precious work of art is the 13th century (1268) Italian floor mosaic known as the Cosmati Pavement, which consists of about 80,000 pieces of red and green porphyry, glass and onyx set into marble.

The swirling patterns of the universe were designed to encourage the monks in their contemplation.

Look for the inscription in brass letters, which foretells when the universe will end – 19,683 years after the Creation.

On the north side of the Sanctuary is an important group of medieval tombs.

Nearest the steps is the tomb of Countess Aveline of Lancaster.

In 1269, aged just 12, she was married to Edmund Crouchback, the youngest son of Henry III, in the Abbey´s first royal wedding.

Above: Royal seal of Edmund Crouchback (1245 – 1296)

Aveline lived only five more years and died in 1274.

Nearest the altar screen is the tomb of her husband, who outlived his child bride by 22 years, dying in 1296.

Between husband and wife is the tomb of Edmund´s cousin Earl Aymer de Valence of Pembroke, who died in 1324.

These three tombs were originally beautifully coloured and decorated, so that in the candlelight they shimmered with an extraordinary luminescence now lost in time.

The elaborate gilded screen behind the High Altar once protected Henry III´s original altarpiece (“retable”), dating from 1270, the oldest oil painting in Britain and now on display in the Abbey Museum.

The Feeding of the 5000 is an exceptionally important work, and though the centuries have not treated it kindly, what remains gives a tantalising insight into what it must once have been like.

Behind the Altar is St. Edward the Confessor´s Chapel, the spiritual heart of the Abbey.

It was here in 2010 that Pope Benedict XVI, making the first ever visit of a Pope to the Abbey, prayed alongside the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Above: Joseph Ratzinger (b. 1927), Pope Benedict XVI (2005 – 2013)

Around the shrine in the centre, which contains Edward´s body, lie five kings and four queens.

Here is the double tomb of King Richard II (1367 – 1399) and his Queen, Anne of Bohemia (1366 – 1394).

Above: Richard II of England (1367 – 1399), King (1377 – 1399)

They were married in the Abbey in 1382.

Richard´s body was not allowed to rest in peace.

In the 18th century someone drilled a hole on the side of his tomb through which visitors could put their hand.

A number of bones went missing, including Richard´s jawbone which was only restored to the corpse in 1906.

Here are also buried King Edward III (1312 – 1377) and his wife Philippa (1310 – 1369).

Above: Effigy of Edward III of England (1312 – 1377), King (1327 – 1377)

The Confessor´s devotee King Henry III has his tomb here as well – beautifully decorated, cast in bronze and gilt.

Here lie the remains of Queen Eleanor of Castille (1241 – 1290), first wife of Edward I.

Above: Statue of Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 1290), Queen (1272 – 1290)

And here lies Edward I (1239 – 1307), at 6 feet 2 inches, very tall for those days, hence his nickname Edward Longshanks.

Above: Edward I of England (1239 – 1307), King (1272 – 1307)

And seek here the tomb of Henry V (1387 – 1422) beside that of his wife Catherine de Valois (1401 – 1437).

Above: Wedding of Henry V and Catherine de Valois

Her coffin and corpse were in full public view for centuries.

Henry V was considered one of England´s greatest monarchs, a fine military commander and an outstanding statesman.

Above: Henry V of England (1386 – 1422), King (1413 – 1422)

(His archers beat the French at Agincourt.)

The English were devastated when he died suddenly in 1422, aged only 35.

He was buried in the Abbey on 7 November, “with such solemn ceremony, such mourning of Lords, such prayer of priests, such lamentation of the common people as never was before that day seen in the realm of England.”

The diarist Samuel Pepys, on a visit to the Abbey in 1669, kissed Catherine´s leathery lips, wrote:

Above: Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703)

“This was my birthday, 36 years old and I did first kiss a queen.”

Henry and Catherine are now protected by an iron grille.

The chairs and footstools in front were given in 1949 by the people of Canada for royal use.

To the south of the Altar are the medieval seats (“sedilia”) for the priests.

Above their heads are the paintings of Henry III and Edward I.

To the west of the sedilia is the flat-topped tomb of Anne of Cleves, the 4th wife of Henry VIII.

Above: Anne of Cleves (1515 – 1557), Queen (1540)

There are more than 600 tombs and monuments in the Abbey, some of them quite massive.

Many people commemorated here are remembered because of their distinguished careers, but quite a few owe their presence in the Abbey more to their wealth or social status.

Today distinguished figures are still commemorated in the Abbey, but our tributes today are rather muted compared with the flamboyance of previous centuries.

The huge monument in the North Ambulatory to General James Wolfe (1727 – 1759) reflects the 18th and 19th centuries´ glorification of military figures, especially when they have died at the moment of victory.

Above: James Wolfe (1727 – 1759)

Wolfe was killed, aged 32, while fighting on the Plains of Abraham, Québec City, in order to capture Canada from the French.

His opponent, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, being French who also died on the Plains, is given no mention.

Above: Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (1712 – 1759)

Some of the best funereal art is tucked away in St. Michael´s Chapel, east of the Statesmen´s Aisle.

Admire the remarkable monument to Francis Vere (1560 – 1609), one of the greatest soldiers of the Elizabethan period, made out of two slabs of black marble, between which lies Sir Francis.

On the upper slab, supported by four knights, Francis´ armor is laid out, to show that he died away from the field of battle.

Near this a most striking grave, in which Elizabeth Nightingale, who died from a miscarriage, collapses in her husband Joseph´s arms while he tries to fight off the spear aimed at her by the skeletal figure of Death, who is climbing out of the tomb.

Above: Tomb of Joseph (1695 – 1752) and Elizabeth Nightingale (1704 – 1731)

In the North Ambulatory, two more chapels contain ostentatious Tudor and Stuart tombs.

One of the most extravagant tombs is that of Lord Hunsdon, Lord Chancellor to Elizabeth I, which not only dominates the Chapel of St. John the Baptist, it is, at 36 feet in height, the tallest tombs in the entire Abbey.

Above: Henry Carey, Lord Dunsdon (1526 – 1596)

From the second chapel, the Chapel of St. Paul, climb the stairs and enter the Lady Chapel (or Henry VII´s Chapel), the most dazzling part of the Abbey.

Begun by Henry VII in 1503 and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the Lady Chapel is beautiful, light, intricately carved vaulting, fan.shaped gilded Pendants and the statues of nearly one hundred Saints, high above the choir stalls decorated with banners and emblems.

Above: Henry VII of England (1457 – 1509), King (1485 – 1509)

George II, the last King to be buried in the Abbey, lies under your feet, along with his Queen Caroline – their coffins fitted with removable sides so that their remains can mingle.

Above: George II of England (1683 – 1760), King (1727 – 1760)

(Certainly a different idea of necrophilia…)

Beneath the altar is the grave of Edward IV, the single sickly son of Henry VIII.

Above: Edward IV of England (1442 – 1483), King (1461 – 1470 / 1471 – 1483)

Behind the Chapel´s centrepiece, the black marble sacrophagus of Henry VII and his spouse – their lifelike gilded effigies are perfectly obscured an ornate grille, designed by an artist more famous for fleeing Italy after breaking Michelangelo´s nose than for his own art: Pietro Torrigiano.

Above: Bust of Henry VII by Pietro Torrignano (1472 – 1528)

His funeral on 11 May 1509 was lavish:

“All the heralds cast their coats of armor off and hung them upon the rails of the hearse, crying lamentably in French – ´Le noble roi Henri le septieme est mort.´ – and as soon as they had done so, every herald put on his armor again and cried with a loud voice – ´Vive le roi Henri le huiteme.´”

Here one finds James I as well as James´ lover Duke George Villiers of Buckingham, the first non-royal to be buried in the Abbey.

Above: George Villiers (1592 – 1628)

Villiers was killed by one of his own disgruntled soldiers.

To the east the Royal Air Force Chapel: stained glass with airmen and angels in the Battle of Britain.

In the floor, a plaque marks the spot where Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell rested….

Briefly.

Until the Restoration, whereupon his mummified body was unearthed, dragged through the streets, hanged and beheaded.

To the north four maidens hold up a vast bronze canopy and weep for another of James I´s “favourites”, Ludovic Stuart.

Above: Ludovic Stuart (1574 – 1624)

Before descending the steps back into the Ambulatory, pop into the Chapel´s north aisle.

Here siblings and hated rivals in life now lie side by side reconciled in death, Elizabeth I and her Catholic half-sister “Bloody” Mary.

“All those who divided at the Reformation by different convictions laid down their lives for Christ and conscience´s sake.”

At the far end is Innocents´ Corner.

Here James I´s infant daughters lie: Princess Sophia who died aged 3 days (1607) and Princess Mary who died the same year aged 2 (1605 – 1607)

Set in the wall between the sisters is the urn containing the bones of the Princes in the Tower, Edward V and his younger brother Richard.

Above: Richard (1473 – 1483) and Edward V of England (1470 – 1483)

As you leave the Lady Chapel, look for the Coronation Chair, a decrepit oak graffiti-covered throne which has been used in every coronation since 1308.

It was custom-built to incorporate the Stone of Scone (the Stone of Destiny), a great slab of redstone which acted as the Scottish coronation stone for centuries before Edward I stole it in 1296.

William the Conqueror was crowned here on 25 December 1066.

Above: Coin of William the Conqueror (1028 – 1087), King (1066 – 1087)

It did not go well.

“When Archbishop Ealdred asked the English, and Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutences asked the Normans, if they would accept William as their King, all of them gladly shouted out with one voice, if not in one language, that they would.

The armed guard (William´s Norman troops), hearing the tumult of the joyful crowd in the church and the harsh accents of a foreign tongue, imagined that some treachery was afoot and foolishly set fire to some of the buildings.

The fire spread rapidly from house to house.

The crowd that had been rejoicing in the church took fright and throngs of men and women of every rank and condition rushed out of the church in haste.

Only the Bishops and a few clergy and Monks remained, terrified, in the Sanctuary, and with difficulty completed the consecration of the King, who was trembling from head to foot.”

On 25 February 1308 Edward II´s ceremony was dominated by his boyfriend Piers Gaveston (1284 – 1312).

Above: Edward II and Piers Gaveston by Marcus Stone (1872)

“Seeking his own glory rather than the King´s”, Gaveston wore an outfit of royal purple, trimmed with pearls.

Nor should he have walked in front of the King in the procession, nor carried Edward´s crown.

The barons were so annoyed at Galveston´s presumption that there was talk of killing him on the spot.

Both Edward and Piers would be assassinated later.

Henry VIII was only 17 at his coronation on 24 June 1509.

He walked to the Abbey from Westminster Palace along a carpet of royal blue.

The crowd was so enthusiastic that they fell on the carpet and cut it up for souvenirs.

Anne Boleyn, the second of Henry VIII´s six wives, was crowned Queen on 1 June 1533.

Above: Anne Boleyn (1501 – 1536)

The ceremony lasted 8 hours and at one point Archbishop Cranmer required Anne to lie on her face in front of the altar – not easy, when she was six months pregnant.

William III´s coronation in 1689 was spoiled by having his money pickpocketed.

Above: William III of England (1650 – 1702), King (1689 – 1702)

To the south is the Abbey´s most popular spot: The Poets´ Corner.

Above: Poets´ Corner with Shakespeare Memorial in the centre

The first occupant, Geoffrey Chaucer, was buried here in 1400.

Above: Geoffrey Chaucer (1343 – 1400)

When Edmund Spenser chose to be buried close to Chaucer in 1599, his fellow poets – Shakespeare among them – threw their own works and quills into the grave.

Above: Edmund Spenser (1552 – 1599)

More than 100 poets, dramatists and prose writers are buried or commemorated here, as well as the composer George Frederick Handel.

Above: George Frederick Handel (1685 – 1759)

(Handel´s funeral on 20 April 1759 was supposed to be private.

3,000 people turned up.)

“Upon the Poets´ Corner in Westminster Abbey

Hail, sacred relics of the tuneful train!

Here ever honoured, ever loved remain.

No other dust of the once great or wise,

As each beneath the hallowed pavement lies,

To this old dome a juster reverence brings….”

Who decides who is to be immortalized in Poets´ Corner?

The Dean of Westminster consults his colleagues in the Chapter and in the literary world, before reaching a decision which, by law, is his alone to make.

It is rare for a recently deceased poet to be memorialized.

The longest period between a poet´s death and memorialization is 1,3oo years: Caedmon (657 – 680), regarded as the first English language poet.

Above: Caedmon Memorial, St. Mary´s Churchyard, Whitby

The Corner has become a Valhalla for poets and a place of pilgrimage for lovers of literature.

The Poets´ Corner´s most famous memorial is that to William Shakespeare, erected 124 years after his death.

Above: William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

His body remains in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, with the inscription:

“Good friend, for Jesus´ sake, forbear

To dig the dust enclosed here!

Blest be the man that spares these stones

And curst be he that moves my bones.”

Why tempt fate?

The Abbey recalls actors: David Garrick, Henry Irving, William Walton, Laurence Olivier, William Walton and Peggy Ashcroft.

Here one finds a controversy:

Ben Jonson was an arrogant man who did not suffer fools and frequently quarrelled with his fellow dramatists.

Above: Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637)

He lived apart from his wife, whom he described as “a shrew, yet honest.”

One of his plays caused grave offence by its lewdness and he was imprisoned.

He later killed a man in a duel and narrowly escaped the gallows.

As Jonson grew older he became fat and alcoholic.

He was too poor for a proper grave and said that a two-foot square would be enough for him.

And that´s what he got, as he was buried standing up.

His bones and coffin have been exposed three times since his burial.

His skull is missing.

Christopher Marlowe was memorialized 409 years after his death because it was felt the Poets´ Corner was already overcrowded.

Above: Christopher Marlowe (1564 – 1593)

Tennyson called Marlowe the morning star which heralded Shakespeare´s dazzling sun.

Another description called him “intemperate and of a cruel heart.”

In 1593, at a Deptford tavern in South London, aged 29, Marlowe was fatally stabbed above his right eye, over a bill for supper.

John Milton had to wait more than 60 years before being memorialized.

Above: Bust of John Milton (1608 – 1674), Temple of British Worthies, Stowe

Milton, famous for his Paradise Lost, could have used the title for his autobiography.

In 1642 he married.

She left him after a few weeks.

In 1648 he began to go blind.

By 1652 he had lost his sight completely, as well as his wife and his only son.

In 1656 Milton married again but she died shortly after giving birth to a daughter.

He was passionate about what he hated.

Anti-Catholic, he called for bishops to be executed and prophesied that they would spend eternity in hell.

Milton attacked the greed of the clergy, rallied against censorship and wrote passionately against the monarchy.

On the Restoration of the monarchy, Milton went into hiding, his arrest was ordered and his books burned.

He was imprisoned in the Tower of London but was later pardoned and released.

Charles II greatly admired Samuel Butler.

Above: Samuel Butler (1612 – 1680)

The King enjoyed Butler´s Hudibras so much that he never ate, drank, slept or went to church without having Hudibras beside him.

Despite the King´s adoration, Butler died penniless.

“While Butler, needy wretch, was yet alive

No generous patron would a dinner give!

See him, when starved to death and turned to dust

Presented with a monumental bust!

The poet´s fate is here in emblem shown

He asked for bread and he received a stone!”

Here one finds an impressive memorial to Matthew Prior, famous for sayings like:

Above: Matthew Prior (1664 – 1721)

“It takes two to quarrel, but only one to end it.”

“The ends must justify the means.”

“They never taste who always drink.

They always talk who never think.”

John Gay was said to be….

Above: John Gay (1685 – 1732)

“In wit, a man; simplicity, a child.”

On Gay´s monument, Alexander Pope wrote a long epitaph, but Gay had the last laugh for two lines are Gay´s not Pope´s:

“Life is a jest, and all things show it.

I thought so once, and now I know it.”

Poets´ Corner is a Who´s Who of the English dead: Longfellow, Wilde, T.S. Elliot, Lewis Carroll, Trollope, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Austen, Keats, Shelley, Burns, the Bronte sisters, Thackeray, Gray, Goldsmith, Blake, Scott, Dickens, Lear, Browning, Brooke, Dylan Thomas, Auden….

Above: Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

(Charles Dickens was buried secretly on 14 June 1870 to avoid crowds, but so many wanted to pay their respects that the grave had to be left open for a time so the public could see him.)

Just to name a few….

Before you enter the Cloisters, check out the South Choir Aisle.

See the tomb of Thomas Thynne that shows how three thugs did him in.

Above: Tomb of Thomas Thynne (1610 – 1669)

Or consider the ironic fate of Admiral Shovell, who survived a shipwreck, was washed up alive on a beach in the Scilly Isles, only to be killed by a fisherwoman who wanted his emerald ring.

Above: Cloudesley Shovell (1650 – 1707)

Or that of the court portrait painter Godfrey Kneller who declared:

Above: Geofrey Kneller (1646 – 1723)

“By God, I will not be buried in Westminster – they do bury fools here.”

Kneller is the only artist to be commemorated in the Abbey.

Enter the Cloisters where Parliament once met, beneath the southern wall where the Whore of Babylon rides the scarlet seven-headed beast from the Book of Revelations.

See the Pyx Chamber which acted like a medieval high security safety deposit box.

Robbers broke in on 24 April 1303 and stole jewels and riches.

Some of them were hanged the following March.

The ringleader of the Pyx robbery was whipped and nailed to the door of the Pyx Chamber as a warning to others.

500 years later pieces of human skin could still be found in the door hinges.

Before you leave the Cloisters enter the Nave itself.

The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior with his garland of red poppies recalls the million British soldiers who died in World War One, with an equivalent number of women dying unmarried because there were no husbands for them.

A tablet in the floor near the Tomb marks the spot where George Peabody, the 19th century philantropist whose housing estates in London still provide homes for those in need, was buried for a month before being exhumed and removed to Massachusetts.

Above: George Peabody (1795 – 1869)

Peabody remains the only American to have been buried in Westminster.

Above the Nave´s west door, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger at just 25 teaches Anarchy while History takes notes.

With all I have described it certainly is no wonder why Westminster Abbey is so popular with tourists.

So much to see, so much to learn and yet Westminster left me with a sense of disappointment.

Not so much with the Abbey itself as much as what the Abbey represents.

Death has become a spectacle and a source of profit.

Does a life have no value if it is not commemorated grandly after death?

Does this mean that the Hindus value life less by burning the bodies of their dead?

And what of the poor who lie in anonymous mass graves unmarked and forgotten?

What of the millions who have died in war or in prison or by dread disease?

Did all these lives have no value because there are no markers to show where their bones are piled?

Does a life have no value if it is not historically significant?

Did all these lives lose their value once their bodies turned to ashes and dust?

I believe that the value of life is in the living, in the apppreciation of the moment, in the appreciation of the Now.

I believe that as long as my life is without extreme pain – physical or psychological – and I am not causing pain to others, then my life has value, at least to myself and hopefully beyond myself.

I don´t require assurance that my remains be assigned some grand memorial in some magnificent cathedral.

I don´t require a cemetery plot or even a funeral.

(Though a drinking party where folks dance with joy celebrating that they continue to live on without me would please me greatly.)

I don´t require a dim unprovable hope that some form of existence awaits me after death.

Am I suggesting that the visitor avoid Westminster Abbey?

No.

It is truly a magnificent structure and is peculiar in its own ways.

But I would be more satisfied with plaques that spoke to me of who a deceased person was, both as a person and someone who accomplished great things.

Epitaphs sound grandiose when read aloud but they speak little about what a person was like when they were alive.

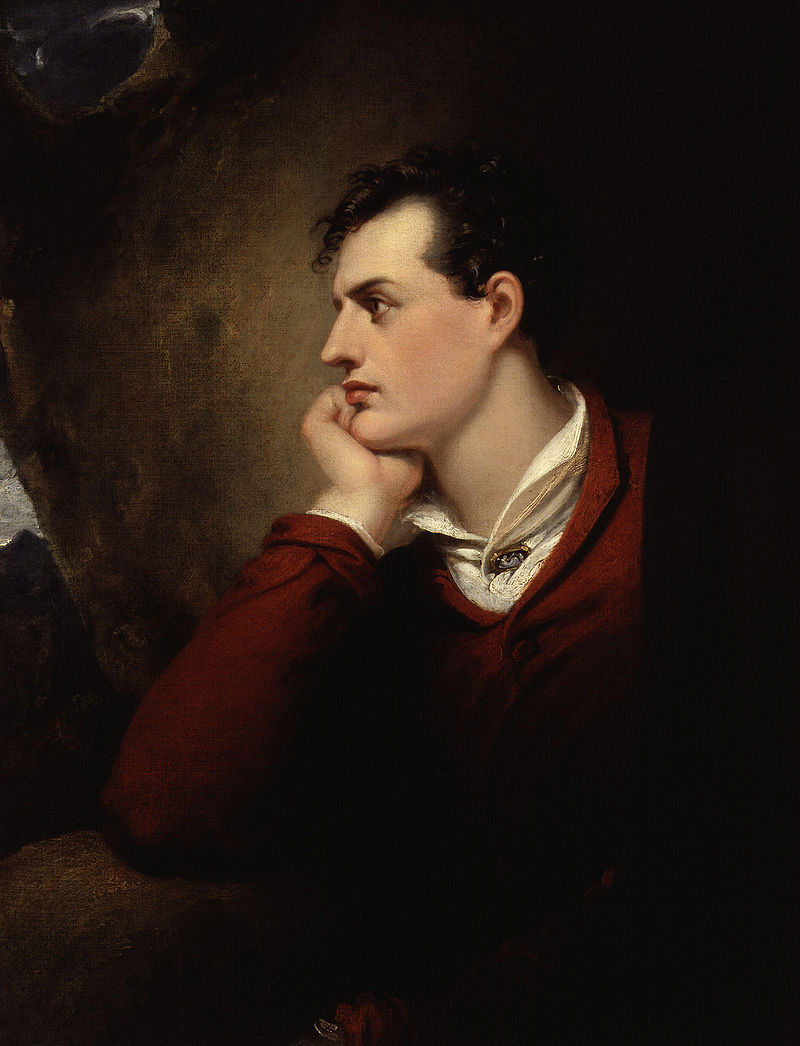

Byron´s monument: “But there is that within me whuch shall tire torture and time and breathe when I expire.”

But who was Byron?

Above: Lord George Byron (1788 – 1824)

T. S. Eliot: “The communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.”

Fine words, but what of the poet who wrote them?

Above: Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888 – 1965)

Trollope: “Now I stretch out my hand and from the further shore I bid adieu to all who have cared to read any among the many words I have written.”

Wouldn´t it be more respectful to read the actual words Trollope wrote then to just simply view his gravesite?

Above: Anthony Trollope (1815 – 1965)

D. H. Lawrence is labelled as “Home sum! The adventurer…” and G. M. Hopkins as “priest and poet, immortal diamond”.

But these words say nothing of who these genetlemen were.

The honour is in appreciating them for what they wrote and the life captured within their words.

Otherwise despite the fine artistry of the graves of Westminster, without an appreciation of who the dead were, what lies beneath slabs of stone is nothing but dust and ashes and the merest whisper of existence.

It would be better to show those that we love that they are loved, rather than mourn their passage which our dead cannot appreciate.

Westminster shows me that death is the great equalizer of us all, no matter how one wishes to decorate the tombs of kings and queens or poets and generals.

If while I live, others are happy that I do so….

“Wouldn´t you like to get away?

Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name.

And they´re always glad you came.

You want to go where you know troubles are all the same.

You want to go where everybody knows your name.”

With a place like this, where everybody knows my name while I am still alive, I don´t need to be buried in some great cathedral.

A great grave doesn´t make a life great.

Great love does.

Sources: Wikipedia / The Rough Guide to London / Julian Beecroft, For the Love of London: A Companion / Nicholas Best, London: In the Footsteps of the Famous / Simon Leyland, A Curious Guide to London / Oliver Tearle, Britain by the Book: A Curious Tour of Our Literary Landscape / www.westminster-abbey.org