Landschlacht, Switzerland, 6 August 2018

Back a few days ago from my third trip to Portugal, my first to Porto and the north of the country.

The most western nation of continental Europe, Portugal shares the Iberian Peninsula with Spain, but this land of foggy fishing villages and tiny hamlets set deep in cork forests has a quarter of Spain’s population, is less than a fifth of Spain’s geographical size and in Portugal they don’t speak Spanish, they speak Portuguese.

Above: Flag of Portugal

Loud, exuberent Spain is paella and bullfights.

Reserved Portugal is the mournful wailing of fado and legendary sightings of the Virgin Mary.

The Spanish are fiercely proud of their past accomplishments.

The Portuguese are quietly proud of their future potential.

Disregard the critics who will gleefully tell you that Portugal is the graveyard of ambition, a kingdom of mediocrity where the national hobby is complaining and the ambitious leave.

Instead….

Picture Portugal as a land of resilience.

An earthquake may have cost them an empire, but Portugal still stands.

Dictators may have halted their progress for decades, but Portugal still stands.

Imagine a land that was economically isolated and politically smothered now striving to overcome an international reputation that suggests that the Portuguese are unproductive, unfit, unhealthy and unattractive.

Spend time with them and realize that though there are some that fit these negative descriptions, the vast majority of the people are simply and quietly going about their business.

They don’t lack self-esteem.

They simply haven’t practiced self-marketing as successfully as their European counterparts, for why tout your superiority when you know who you are and what you can do?

To be fair, judging Portugal by one’s impressions of Porto is a lot like judging America from only a visit to Chicago or England from time spent exclusively in Birmingham.

Just as New York and London overshadow hard-working Chicago and Birmingham so does Lisboa (Lisbon) dominate people’s minds over Porto.

Above: Images of Porto

Traditionally Portugal’s wine distribution centre, the scenic city of Porto – Portugal’s second biggest city – straddles the Douro River and is a lively transport hub, in part due to its famous export, port.

If the adage “Lisbon plays, Porto pays, Coimbra prays” can be believed, then Porto is the hardest working place in Portugal.

Historically (and practically) Porto puts the Portu in Portugal as the name dates from Roman times, when Lusitanian settlements straddled both sides of the Rio Douro.

The area was briefly in the hands of Moors but was reconquered by the year 1000 and reorganized as the County of Portucale with Porto as its capital.

Henri of Burgundy was granted the land in 1095 and it was from here that Henri’s son and Portuguese hero Afonso Henriques launched the Reconquista (Christian reconquest), ultimately winning Portugal the status of an independent kingdom….part of the Iberian Peninsula, but not part of Spain.

Above: King Afonso I Henriques of Portugal (1106 – 1185)

The Portuguese are akin to Canadians, Swiss and New Zealanders in that they do not care to be mistaken for being a countryman of their more powerful and prominent neighbour.

When addressed in Spanish by a foreigner, a Portuguese would rather answer in English or French.

Spain is the loud neighbour with the big house and the trees that block out the light.

To get to Portugal the rest of Europe passes through Spain, leaving tourist revenues and business investment on Spanish shores.

The Spanish are not the neighbours from Hell, but they are neighbours the Portuguese resent.

“Neither good winds nor good marriages come from Spain.” goes the well-known Portuguese saying.

Over 400 years ago Spain relinquished occupation of Portugal, but distrust runs deep after a bloody history of wars and border skirmishes.

Even now, many Portuguese claim the town of Olivenca in Spanish Extremadura as their own invoking a treaty of 1815 which Spain continues to conveniently forget.

Portugal’s economy hangs on the coat tails of Spain much as Canada’s economy is dependent on American trade and Switzerland’s upon trade with Germany.

We all look with alarm when German companies take over slices of Switzerland’s economy or Americans financially invade Canada or the Spanish seize Portuguese banks or real estate.

Yet for the Swiss to go to Germany or Canadians to go to America or Portuguese to go to Spain is a certain sign that you’ve entered the Big Time.

“Big time. I’m on my way. I’m making it….big time.” (Peter Gabriel)

Many of Portugal’s top footballers leap at the chance to play for Real Madrid, much like Canadian hockey players jump for joy when recruited by American teams.

Above: Real Madrid Football Club logo

(The world is strange.

How are hockey teams in two nations considered part of one National Hockey League?

Why is the finale in North American baseball called the World Series when only (with rare exception, Canada’s Toronto Blue Jays) American teams compete?

I am so confused.)

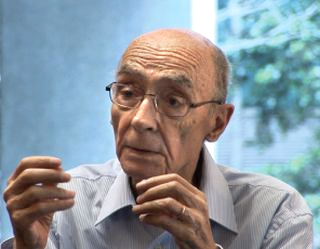

Nobel Prize winning author José Saramago (The History of the Siege of Lisbon / Blindness) left Portugal to live in Spanish Tenerife, much like Wayne Gretzky and Jim Carrey left Canada to live in LA.

Above: José Saramago (1922 – 2010)

Like the British and Canadians are cynical about Americans, like Austrians and Swiss are cynical about Germans, the Portuguese too are cynical about the Spanish.

And like Anglos with America and Swiss with Germany, the Portuguese secretly hanker to be like the Spanish.

The first day of my third Portuguese adventure was a reminder of this problematic relationship with Spain.

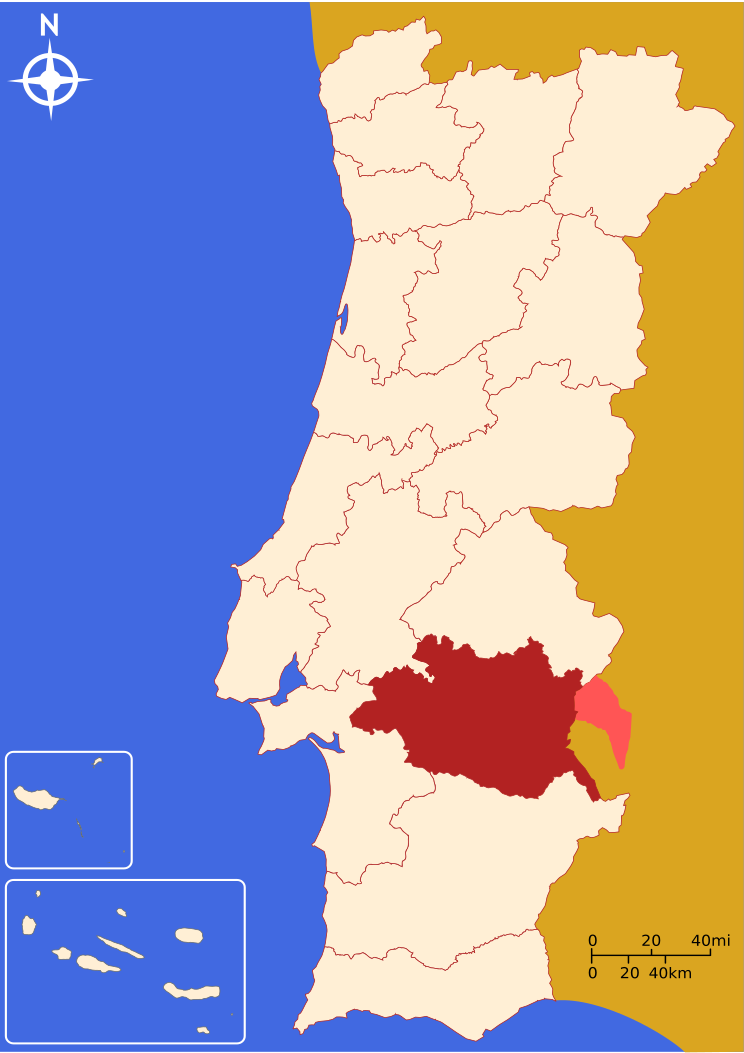

Above: The Iberian Peninsula

Porto, Portugal, 24 July 2018

I have nothing against the Spanish.

Above: Flag of Spain

I enjoyed my two previous visits to Spain’s San Sebastian (let’s leave questions of Basque independence aside at this time) and Barcelona (ditto for Catalona).

I am emotionally unaffected by the planning that resulted in flying two Spanish airlines (Iberia and Vueling) from Zürich to Porto and return.

The flights booked through the Internet, which might not have been the least expensive method, was at least the most efficient way to go.

(Most Internet travel agencies work by connecting a website to a computerized reservation service (CRS) that in turn is linked to the airlines.

Because the airlines and the CRSs only list official, published fares in their databases, most Internet travel agencies only sell tickets at published fares and have no discounts.

Most international air ticket prices are not shown in any CRS, are not available directly from the airline, and are not available from any Internet site that depends on airlines and/or CRSs as a source of fares.)

Still I may not have had a choice as TAP, Portugal’s national airline, flies only to the western Swiss city of Genève rather than that most convenient airport of Zürich in eastern Switzerland.

So, can Spanish airlines be blamed too harshly for taking up the Portuguese slack?

Iberia flight 1077, Zürich (ZUR) to Porto (POR) with a stopover in Madrid (MAD), is aboard an Airbus A319 plane named the Ciudad de Baiez.

Intercom announcements and seat pocket literature are in English and Spanish.

Unlike Swiss teacher Raimund Gregorius of Pascal Mercier’s Night Train to Lisbon, (begun to be read during this flight) there were no chance encounters with mysterious suicidal Portuguese bridge jumpers or tomes of philosophical enigmatic aristocrats found in dusty corners of antiquarian bookshops to inspire this trip to Portugal.

A vacation was needed and Porto had not yet been explored.

I did not impulsively leave Switzerland as Gregorius left his job.

There was a plan, organization, flight and hotel reservations.

Like Gregorius, I would have preferred to travel to Portugal slower than flying, but like most tourists I am limited by constraints of time, money and responsibility.

The Ronda, Iberia’s seat pocket magazine, distracts me from the haunted journey of Gregorius.

I read about the Bloop Festival of Ibiza, Brunch in the Park in Barcelona, and recommended explorations of Japan with their 40 sumo wrestling training gyms, 3,000 public thermal baths and 21 UNESCO World Heritage sites.

I read of Barcelona and the Lavender Road of Provence, of the paradise that is Patagonia and the temptations of Tenerife, of summer flights to Croatia and of “somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember“.

I am flying to Portugal, but there is no whisper about the place aboard the flight.

The gluten-free muffins, the Linda limonada, the MIOS patatas are all Spanish.

Above: Aeroporto Porto

After touchdown at Porto Airport, taxi into town and check-in at the Casa de Cativo in the Batalha district of central Porto, we find ourselves drawn to explore.

My eyes are immediately drawn to the Sé – Porto’s Cathedral.

This Roman Catholic Cathedral is one of the most relevant and oldest monuments of the city.

Located in the heart of the historical centre the Sé rises from the landscape as an eye-catching icon atop a rocky outcrop a couple of hundred metres from Sao Bento Station and commands a fine view over the rooftops of Porto.

In front of the Cathedral, a lone sentinel on horseback, Vimara Peres (d. 873), the first King of the County of Portugal, stands watch over the city in stone silence.

The Sé is flanked by two square towers that stretch like arms reaching for Heaven.

Each tower is supported by two buttresses and crowned with a cupola.

On the North Tower (the one with the bell) look for the worn bas-relief depicting a 14th century ship – a coca – a reminder of the earliest days of Portugal’s maritime epic when sailors inched tentatively down the west Saharan coastline in fear of monsters.

The facade lacks decoration and yet is not lacking in beauty.

The Baroque porch and the delicate Romanesque rose window under the crenellated arch lend the Sé the impression of a fort, a sort of setting suited for the commencement of some holy quest or mighty crusade.

Inside, the blend of Baroque, original Romanesque and Gothic architecture – a kind of structural bouillabaisse – is a strange marriage of prevading gloom.

But maybe gloom – an uneasy spectre of death – was what was sought after when the Sé was being designed.

Around 1333 the Gothic funerary chapel of Joao Gordo was added – his tomb decorated with his recumbent figure and reliefs of the Apostles – the Beatles of the New Testament in regards to their creativity.

Gordo was a Knight Hospitalier who worked for King Dinis I (1261 – 1325).

Above: Flag of the Knights Hospitaller

(The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, also known as the Order of Saint John, Order of Hospitallers, Knights Hospitaller, Knights Hospitalier or Hospitallers, was a medieval Catholic military order, headquartered in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, on the island of Rhodes, in Malta and St Petersburg.)

(King Dinis I, also called the Farmer King and the Poet King, was King of Portugal (1279 – 1325) for over 46 years and is remembered by the Portuguese as a major contributor to the formation of a sense of national identity and an awareness of Portugal as a nation-state.

He worked to organize his country’s economy and gave an impetus to Portuguese agriculture.

He ordered the planting of a large pine forest (that still exists today) near Leiria to prevent soil degradation that threatened the region and as a source of raw materials for the construction of the royal ships.

Above: Leiria Castle

Dinis was known for his poetry, which constitutes a major contribution to the development of Portuguese as a literary language.)

(More on Dinis in a future post….)

In 1387, the Cathedral was embellished to celebrate the wedding of Portuguese King Jaoa I with the English Princess Philippa of Lancaster (reinforcing the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance).

Above: Wedding of Portuguese King Joao I and English Princess Philippa of Lancaster, Porto Cathedral, 11 February 1387

It was this matrimonial bond of man and wife, this Alliance of Portugal and England within this Sé that would witness within those same walls that which was a celebration of the newly-wed would become a commiseration of the bloody dead.

On 29 January 1801, an ultimatum from Spain and France forces Portugal to decide between France and Britain, even as its government has tried to negotiate favorable relations with the two powers rather than abrogate the Treaty of Windsor (1386).

The French sent a five-point statement to Lisbon demanding that Portugal:

- Abandon its traditional alliance with Great Britain and close its ports to British shipping;

- Open its ports to French and Spanish shipping;

- Surrender one or more of its provinces, equal to one fourth part of her total area, as a guarantee for the recovery of Trinidad, Port Mahon (Menorca) and Malta;

- Pay a war indemnity to France and Spain;

- Review border limits with Spain.

If Portugal failed to accomplish the five conditions of this ultimatum, it would be invaded by Spain, supported by 15,000 French soldiers.

The British could not promise any effective relief, even as Prince Joao VI appealed to Hookham Frere, who arrived in November 1800.

Above: Joao VI “the Clement” (1767 – 1826)

In February, the terms were delivered to the Prince-Regent.

Although he sent a negotiator to Madrid, war was declared.

At the time, Portugal had a poorly trained army, with less than 8,000 cavalry and 46,000 infantry troops.

Its military commander, João Carlos de Bragança e Ligne (2nd Duke of Lafões), had barely raised 2,000 horse and 16,000 troops and was compelled to contract the services of a Prussian colonel, Count Karl Alexander von der Goltz, to assume command as field marshal.

The Spanish Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief, Manuel de Godoy, had some 30,000 troops at his disposal, while the French troops under General Charles Leclerc (Napoleon’s brother-in-law) arrived in Spain too late to assist Godoy, as it was a short military campaign.

On May 20, Godoy finally entered Portugal.

This incursion was a precursor of the Peninsular War that would engulf the Iberian Peninsula.

The Spanish army quickly penetrated the Alentejo region in southern Portugal and occupied Olivença, Juromenha, Arronches, Portalegre, Castelo de Vide, Barbacena and Ouguela without resistance.

Campo Maior resisted for 18 days before falling to the Spanish army, but Elvas successfully resisted a siege by the invaders.

An episode which occurred during the siege of Elvas accounts for the name, “War of the Oranges“:

Godoy, celebrating his first experience of generalship, plucked two oranges from a tree and immediately sent them to Queen Maria Luisa of Spain, mother of Carlota Joaquina and supposedly his lover, with the message:

I lack everything, but with nothing I will go to Lisbon.

Manuel de Godoy

The conflict ended quickly when the defeated and demoralized Portuguese were forced to negotiate and accept the stipulations of the Treaty of Badajoz, signed on 6 June 1801.

As part of the peace settlement, Portugal recovered all of the strongholds previously conquered by the Spanish, with the exception of Olivença and other territories on the eastern margin of the Guadiana and a prohibition of contraband was enforced near the border between the two countries.

The treaty was ratified by the Prince-Regent on 14 June, while the King of Spain promulgated the treaty on 21 June.

A special convention (the Treaty of Madrid) on 29 September 1801 made additions to that of Badajoz whereby Portugal was forced to pay France an indemnity of 20 million francs.

This treaty was initially rejected by Napoleon, who wanted the partition of Portugal, but he accepted once he concluded a peace with Great Britain at Amiens.

Above: Napoléon (1769 – 1821)

Portugal divides itself into 18 districts.

Porto is the capital city of the Porto District, which is itself divided into 18 municipalities.

Of these municipalities the close-by city of Amarante lies to the northeast of Porto.

During this War of the Oranges (20 May – 9 June 1801) while a battle raged in Amarante, a group of Spanish soldiers briefly took control of the Porto Cathedral before being overcome by the locals of the town.

A marble plaque hangs behind the altar in memory of those who lost their lives regaining control of the chapel.

The plaque has a magnetic backing that was chosen to order to remind those travelling near the Cathedral to orient themselves in the direction their compasses have been altered towards.

I can´t help but wonder what Hollywood would have done with a story like this:

Soldiers seize a church.

Locals battle to regain it.

But details are hard to come by here in distant Landschlacht and there is a tragic lack of ability in my reading Portuguese.

But I can imagine it.

Sunday 31 May 1801, Porto, Portugal

It was the perfect opportunity.

A full moon week meant the soldiers could ride in the Saturday night moonlight and lie in wait inside the Cathedral until the faithful showed up the following morning.

The Cathedral would have gold and the parishioners – faithful tithe-givers to the last – would have money.

The soldiers simply sought profits but they would be ignored if the parishioners didn’t believe that the soldiers would slay them if they did not obey.

The locals outside the church would be half-mad with grief and worry and would do anything to ensure the safety of their loved ones within.

The Bishop would be outraged at the sacreligious nature and audacity of the soldiers’ act.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 6 August 2018

At this point of planning the plot of this historical drama I would require the aforementioned details that language and long distance deny me.

Was blood shed?

By whom upon whom?

History records the soldiers were unsuccessful, but what was their fate?

Who were these people: the Bishop, the faithful, the townsfolk, the soldiers?

Do I actually need historical facts and actual accuracy to tell their story?

Take the movie Braveheart about the Scottish hero William Wallace.

Many liberties were taken and the plot is filled with historical inaccuracies but is it a damn good movie?

Absolutely.

I am reminded again of Portuguese author José Saramago – a writer damnably difficult to read for his deliberate determination not to use punctuation or paragraphs but a fine storyteller nonetheless.

In his The History of the Siege of Lisbon, Saramago asks:

What happens when the facts of history are replaced by the mysteries of love?

“When Raimundo Silva, a lowly proofreader for a Lisbon publishing house, inserts a negative into a sentence of a historical text, he alters the whole course of the 1147 Siege of Lisbon.

Fearing censure he is met instead with admiration: Dr. Maria Sara, his voluptuous new editor, encourages him to pen his own alternative history.

As his retelling draws on all his imaginative powers, Silva finds – to his nervous delight – that if the facts of the past can be rewritten as a romance then so can the details of his own dusty bachelor present.”

Saramago suggests so many scenarios one could use and have been used by other authors in the past:

What if you had the power to change the past? (time travel)(Time Cop)

What if you had the power to enter the world of literature? (fantasy)(Inkheart)

What if you deliberately altered the record of the past to better reflect and justify the present? (George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four)

Telling the tale of the taking of Porto Cathedral also carries with it some responsibility.

I don’t wish to glorify the Portuguese, for their history is not a bloodless nor innocent one in regards to their colonialism or dark dictatorship days.

I don’t wish to increase the innate antagonism between the Portuguese and the Spanish, for, in my humble opinion, writing should seek to unite humanity rather than divide it, even if history is truly horrific.

Still I smell a story just begging to be written, replete with drama and suspense – a kind of Die Hard meets Braveheart scenario, maybe mixed with a dash of Timeline and Timecop.

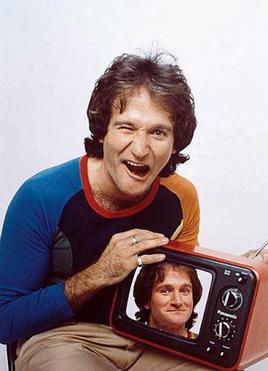

Maybe this is all just idle musings, for my mind is much like the late comedian Robin Williams’ observations of former US President George W. Bush’s span of attention:

“My fellow Americans….

Oh! Look at the baby!

Squirrel!”

Above: Robin Williams (1951 – 2014)

What I am left with when I consider the taking of Porto Cathedral is not so much that an extraordinarily beautiful house of worship was seized or a symbol of a religious affliation defiled.

Rather I find it interesting that the very church where the English-Portuguese Alliance came into being would become a battlefield in maintaining that alliance.

The whole story has the feel of witnessing a bully at a wedding seize one of the guests and threaten to kill him if the couple continues on with the nuptial ceremony.

Couples may not always co-exist harmoniously but nothing unites a couple more than someone else trying to separate them.

Though Portugal may have lost the War of the Oranges, Portugal’s defiance of bullying Spain ensured Britain’s assistance a few years later and strengthened Portuguese resolve to maintain their own alliances on their own terms.

I don’t see prevailing gloom within the Sé of Porto but rather my mind escapes up from the shadows and into the cloisters of magnificent azulejos and ascends the grand staircase to the dazzling chapterhouse with its sweeping views from the windows.

It is all a matter of perspective.

The Spanish seized a Cathedral and lost it.

The French and the Spanish defeated Portugal and later were defeated by the very alliance they tried to destroy.

Red may have spilled from soldier wounds and the faithful injured, but red is also half the colour of the Portuguese flag: combative, hot, virile.

A singing, ardent, joyful colour ever reminding of victory despite the high cost.

I don’t hear the lamentations of the frightened nor the murmuring of prayers and exhortations to God, but rather the fever and fervour of the resilient and determined.

As the words ring out strong and clear the Portuguese national anthem proudly proclaims:

“Unfurl the unconquerable flag in the bright light of your sky!

Cry out all Europe and the whole world that Portugal has not perished.

Your happy land is kissed by the ocean that murmurs with love.

And your conquering arm has given new worlds to the world!”

Two centuries, four months and a matter of weeks later, America would on 11 September 2001, suffer an attack far more devastating and tragic than the now-and-long forgotten taking of Porto Cathedral, but nothing strengthens a nation more than adversity or unites it into determined defiance against those who would seek to diminish it.

Like the United States, no one bothers or bullies Portugal any more.

Of the trials and tribulations Portugal, like the United States, has endured, much has been created by itself and resolved by itself.

To be blunt, the Sé, this Cathedral of Porto, to this world weary traveller is quite forgettable.

What Porto Cathedral represents, isn’t.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / The Rough Guide to Portugal / Porto and Northern Portugal: Journeys and Stories