Landschlacht, Switzerland, 12 August 2018

Perhaps I should have been recovering from yesterday’s Street Parade in Zürich, at present the most attended techno-parade in the world.

Officially it is a demonstration for freedom, love and tolerance attended by up to one million people.

In reality it has all the character of a popular festival, despite (technically) being a political demonstration.

The streets are packed, the music is loud and live, electronics throb and flash, dancing till dizziness, alcohol flows, drugs dispensed….

Somehow the message is we should all live together in peace and tolerance.

In my experience a mob of drunken stoned revellers doesn’t suggest peace and tolerance.

Instead I quietly celebrated a sad anniversary today.

On this day in 1955 the Nobel Prize-winning German author Thomas Mann died.

Kilchberg, Swizerland, 12 August 2018

German author Thomas Mann and his family made their home in Kilchberg near Zürich overlooking the Lake of Zürich, and most of them are buried here.

As well, Swiss author Conrad Ferdinand Meyer lived and died in Kilchberg and is honoured by a Museum here.

(Today was my third and finally successful attempt to visit this Museum.

More on this in a future blog….)

The chocolatier David Sprüngli-Schwartz of the chocolate manufacturer Lindt & Sprüngli died in Kilchberg, now the headquarters of the company.

(More on Lindt in a future blog….)

Prior to moving to Switzerland in 2010, I had never met nor heard of anyone named Golo, which to my mind sounds like an instruction….

“I’ll take the high road.

You, go low.”

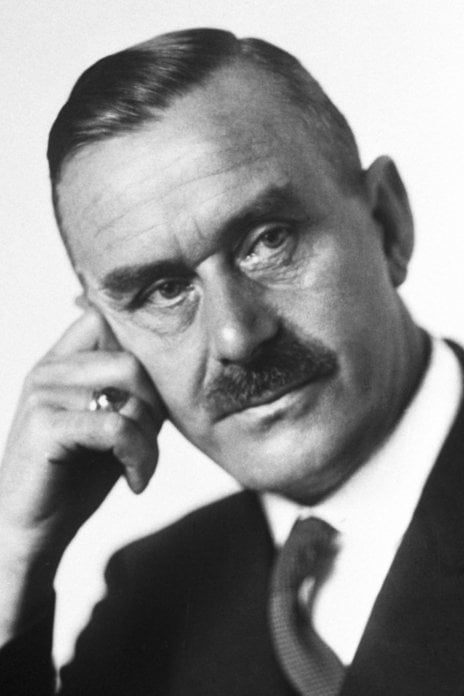

In this region, Golo is associated with, among other things, Thomas Mann (1875 – 1955), the Nobel Prize (1929) winning author of Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain, and his brood.

Above: Thomas Mann

Thomas and his wife Katia (1883 – 1980) had six children:

- Erika (1905 – 1969)

- Klaus (1906 – 1949)

- Golo (1909 – 1994)

- Monika (1910 – 1992)

- Elisabeth (1918 – 2002)

- Michael (1919 – 1977)

With the notable exception of Klaus who rests in peace in a cemetery in Cannes (France), Thomas lies buried with his wife and their other children in the same final resting ground of Kilchberg Cemetery just south of the city of Zürich.

Thomas, Katia, Erika, Monika, Elisabeth and Michael all share the same gravesite in the Kilchberg Cemetery.

Though Golo is in the same cemetery, his grave stands separated away from the rest of his Kilchberg-interred family, in fulfillment of his last will and testament.

There is no denying that Golo’s desire to be buried separately from his family made me curious….

During my convalescence in Klinik Schloss Mammern (19 May – 15 June) I took a day trip across the Lake of Constance to the German village of Gaienhofen with its Hermann Hesse Museum’s exhibition: “The Manns at Lake Constance“.

Above: Hermann Hesse Museum, Gaienhofen, Germany

(More on Hermann Hesse in future blogs…)

Also, I have long known that Golo Mann brought his family, in the summers of 1956 and 1957, to Altnau (the next town east on the Lake from Landschlacht).

Above: The guesthouse Zur Krone where Golo worked on his German History of the 19th and 20th Centuries, Altnau, Switzerland

In this day and age where many of us forget what we ate for supper without a photo on Instagram, many people (predominantly German speakers) still recall the name of Thomas Mann, but, as is common with the passage of time, we rarely recall the obscure names of the children of the more-famous parents.

Pop Quiz:

What were the names of the children of world famous William Shakespeare (1584 – 1616) or Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)?

Give up?

So did I.

I had to search on Wikipedia.

William’s:

Above: William Shakespeare

Susanna (1583 – 1649), Hamnet (1585 – 1596) and Judith (1585-1662)

Albert’s:

Above: Albert Einstein

Lieserl (1902 – 1903), Hans (1904 – 1973) and Eduard (1910 – 1965)

This is not to suggest that these six individuals are not worth remembering but rather that their memory is overshadowed by the fame of their fathers and the passage of time.

(To be fair, famous children have also been known to overshadow their progenitors.

Who knows the names of Sammy Davis Sr., Martin Luther King Sr., or Robert Downey Sr. without the fame of their sons?)

Above: Robert Downey Jr. (Chaplin, Air America, Iron Man)

So, I confess, my repeated encounters with the name of Golo Mann made me curious about him and his famous father.

Paul Thomas Mann (full name) was born in Lübeck, Germany, the second son of Lutheran Thomas Mann (grain merchant/senator) and Brazilian-born Roman Catholic Julia da Silva Bruhns.

Mann’s father died in 1891 and his trading firm liquidated.

Julia moved the family to Munich, where Thomas studied at the University of Munich to become a journalist.

Thomas lived in Munich until 1933, with the exception of a year spent in Palestrina, Italy, with his elder brother Heinrich.

Above: Heinrich Mann (1871 – 1950)

Thomas’s career as a writer began when he wrote for the magazine Simplicissimus, publishing his first short story “Little Mr. Freidemann” in 1898.

In 1901, Mann’s first novel Buddenbrooks was published.

Based on Mann’s own family, Buddenbrooks relates the decline of a merchant family in Lübeck over the course of three generations.

That same year, Mann met Englishwoman Mary Smith, but Mann was a friend of the violinist/painter Paul Ehrenberg, for whom he had feelings which caused Mann difficulty and discomfort and were an obstacle to marrying Smith.

By 1903, Mann’s feelings for Ehrenberg had cooled.

In 1905, Mann married Katia Pringsheim (1883 – 1980), daughter of a wealthy, secular Jewish industrial family.

Above: Thomas Mann and Katia Pringsheim-Mann

Erika was born that same year.

Above: Erika Mann-Auden (1905 – 1969)

Mann expressed in a letter to Heinrich his disappointment about the birth of his first child:

“It is a girl.

A disappointment for me, as I want to admit between us, because I had greatly desired a son and will not stop to hold such a desire.

I feel a son is much more full of poetry, more than a sequel and restart for myself under new circumstances.”

Klaus was born the following year, with whom Erika was personally close her entire life.

Above: Klaus Mann (1906 – 1949)

They went about “like twins” and Klaus would describe their closeness as:

“Our solidarity was absolute and without reservation.”

Golo (remember him?) was born in 1909.

Above: Golo Mann (1909 – 1994)

In her diary his mother Katia described him in his early years as sensitive, nervous and frightened.

His father hardly concealed his disappointment and rarely mentioned Golo in his diary.

Golo in turn described Mann:

“Indeed he was able to radiate some kindness, but mostly it was silence, strictness, nervousness or rage.”

Golo was closest with Klaus and disliked the dogmatism and radical views of Erika.

Monika, the 4th child of Mann and Katia, was born in 1910.

Above:(from left to right) Monika, Golo, Michael, Katia, Klaus, Elisabeth and Erika Mann, 1919

Mann’s diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality and longing for pederasty (sex between men and boys).

His diaries reveal how consumed his life had been with unrequited and subliminated passion.

In the summer of 1911, Mann stayed at the Grand Hotel des Bains on the Lido of Venice with Katia and his brother Heinrich, when Mann became enraptured by Wladyslaw Moes, a 10-year-old Polish boy.

Above: Grand Hotel des Bains, Venezia

This attraction found reflection in Mann’s Death in Venice (1912), most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio.

Mann’s old enemy, Alfred Kerr, sarcastically blamed Death in Venice for having made pederasty acceptable to the cultivated middle classes.

Above: Alfred Kerr (né Kempner)(1867 – 1948)

That same year, Katia was ill with a lung complaint.

Above: Wald Sanatorium, Davos

In 1912, Thomas and Katia moved to the Wald Sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, which was to inspire his 1924 book The Magic Mountain – the tale of an engineering student who, planning to visit his cousin at a Swiss sanatorium for only three weeks, finds his departure from the sanatorium delayed.

In 1914, the Mann family obtained a villa, “Poshi“, in Munich.

Above: The Mann residence “Poshi“, Munich

By 1917, Mann had a particular trust in Erika as she exercised a great influence on his important decisions.

“Little Erika must salt the soup.” was an often-used phrase in the Mann family.

Elisabeth, Mann’s youngest daughter, was born in 1918.

That same year, Mann’s diary records his attraction to his own 13-year-old son “Eissi” – Klaus:

5 June 1918: “In love with Klaus during these days“.

22 June 1918: “Klaus to whom I feel very drawn“.

11 July 1918: “Eissi, who enchants me right now“.

25 July 1918: “Delight over Eissi, who in his bath is terribly handsome. Find it very natural that I am in love with my son….Eissi lay reading in bed with his Brown Torso naked, which disconcerted me.”

In 1919, the last child and the youngest son, Michael was born.

On 10 March 1920, Mann confessed frankly in his diary that, of his six children, he preferred the two oldest, Klaus and Erika, and little Elisabeth:

“….preferred, of the six, the two oldest and Little Elisabeth with a strange decisiveness.”

(Golo and Michael are not mentioned.)

17 October 1920: “I heard noise in the boys’ room and surprised Eissi completely naked in front of Golo’s bed acting foolish. Strong impression of his premasculine, gleaming body. Disquiet.”

Klaus’s early life was troubled.

His homosexuality often made him the target of bigotry and he had a difficult relationship with his father.

In 1921, Erika transferred to the Luisen Gymnasium (high school).

While there she founded an ambitious theatre troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Miniker and was engaged to appear on the stage of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin for the first time.

The pranks she pulled with her Herzog Park Gang prompted Mann and Katia to send her and Klaus to a progressive residential school, the Bergschule Hochwaldhausen in Vogelsberg, for a few months.

Increasingly sensing his parents’ home as a burden, Golo attempted a kind of break-out by joining the Boy Scouts in the spring of 1921.

Sadly, on one of the holiday marches, Golo was the victim of a sexual violation by his group leader.

New horizons opened up for Golo in 1923, when he entered the boarding school in Salem, feeling liberated from home and enjoying the new educational approach.

There in the countryside near Lake Constance, Golo developed an enduring passion for hiking through the mountains, although he suffered from a lifelong knee injury.

Klaus began writing short stories in 1924, while Erika graduated and began her theatrical studies in Berlin, which were frequently interrupted by performances in Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, Bremen, and other places in Germany.

In 1925 Klaus became drama critic for a Berlin newspaper and wrote the play Anja und Esther – about a group of four friends who were in love with each other – which opened in October 1925 to considerable publicity.

Actor Gustaf Gründgens played one of the lead male roles alongside Klaus while Klaus’s childhood friend Pamela Wedekind and Erika played the lead female roles.

Above: Gustaf Gründgens (1899 – 1963)

During the year they all worked together, Klaus became engaged with Pamela and Erika with Gustaf, while Erika and Pamela and Klaus and Gustaf had homosexual relationships with each other.

That same year Golo suffered a severe mental crisis that overshadowed the rest of his life.

“In those days the doubt entered my life, or rather, broke in with tremendous power.

I was seized by darkest melancholy.”

For Erika and Gustaf’s honeymoon in July 1926, they stayed in the same hotel that Erika and Pamela had used as a couple, with Pamela checking in dressed as a man.

In 1927, Golo commenced his law studies in Munich, moving the same year to Berlin, switching to history and philosophy.

Klaus travelled with Erika around the world, visiting the US in 1927, and reported about this in essays published as a colloborative travelogue, Rundherum: Das Abenteuer einer Weltreise (All the Way Round) in 1929.

Klaus broke off his engagement with Pamela in 1928.

Golo used the summer of 1928 to learn French in Paris and to get to know “real work” in a coal mine in eastern Germany, abruptly stopping because of new knee injuries.

Erika became active in journalism and politics.

Golo entered the University of Heidelberg in 1929.

Erika and Gustaf divorced.

Meanwhile Mann had a cottage built in the fishing village of Nida, Lithuania, where there was a German artists colony, spending the summers of 1930 – 1932 working on Joseph and His Brothers.

(It took Mann 16 years to complete this.)

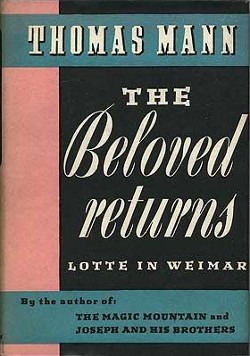

Above: Joseph the Provider, the 4th and last volume of the Joseph and His Brothers tetralogy (1943)

(Today, the cottage is a cultural centre dedicated to him.)

Above: Thomas Mann Cultural Centre, Nida, Lithuania

Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929.

That same year, Klaus travelled with Erika to North Africa, where they made the acquaintance of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, a Swiss writer and photographer, who remained close to them for the next few years.

Above: Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908 – 1942)

In 1930, Mann gave a public address in Berlin (“An Appeal to Reason“) strongly denouncing National Socialism (Nazis) and encouraging resistance against them by the working class.

Golo joined a socialist student group in Heidelberg.

Meanwhile, Monika, after boarding school at Schloss Salem, trained as a pianist in Lausanne and spent her youth in Paris, Munich, Frankfurt and Berlin.

In 1931, Erika was an actor in the Leontine Sagan film about lesbianism, Mädchen in Uniform (Maidens in Uniform) but left the production before its completion.

With Klaus, she published The Book of the Riviera: Things You Won’t Find in Baedekers.

In 1932, she published Stoffel fliegt übers Meer (Stoffel flies over the ocean), the first of seven children’s books.

That year, Erika was denounced by the Brownshirts after she read a pacifist poem to an anti-war meeting.

As a result she was fired from an acting role after the theatre concerned was threatened with a boycott by the Nazis.

She successfully sued both the theatre and a Nazi-run newspaper.

She had a role, alongside Therese Giehse, in the film Peter Voss, Thief of Millions.

In January 1933, Erika and Klaus and Therese Giehse founded a cabaret in Munich called Die Pfeffermühle (the pepper mill), for which Erika wrote most of the material, much of which was anti-Fascist.

The cabaret lasted two months before the Nazis forced it to close and Erika left Germany.

She was the last member of the Mann family to leave Germany after the Nazi regime was elected.

She saved many of Mann’s papers from their Munich home when she escaped to Zürich.

Heinrich, Mann’s brother, was the first person to be stripped of German citizenship when the Nazis took office.

When the Nazis came to power Mann and Katia were on holiday in Switzerland.

While at Sanary-sur-Mer in the southeast of France, (where Monika joined her parents) Mann learned from his children Klaus and Erika in Munich that it would not be safe for him to return to Germany due to Mann’s strident denunciation of Nazi policies.

Above: Sanary-sur-Mer, France

Golo looked after the Mann house in Munich in April, helped Monika, Elisabeth and Michael leave the country and brought most of his parents’ savings via Karlsruhe and the German embassy in Paris to Switzerland.

On 31 May 1933, Golo left Germany for the French town of Bandol.

He spent the summer at the mansion of the American travel writer William Seabrook near Sanary-sur-Mer and lived six weeks at the new family home in Küsnacht.

Above: List of literary celebrities who fled the Nazis and once lived in Sanary-sur-Mer (Not mentioned are Jacques Cousteau, Frederic Dumas and Ernest Blanc – oceanographers Cousteau and Dumas lived and invented the aqualung here while native Blanc was a famous opera performer.)

In November Golo joined the École Supérieure at Saint-Cloud (near Paris) as a German language teacher and wrote for the emigrants’ journal Die Sammlung (The Collection) founded by Klaus.

In 1934 Monika studied music and art history in Firenze, where she met Hungarian art historian Jenö Lányi.

In November 1934 Klaus was stripped of German citizenship by the Nazi government.

He became a Czechoslovak citizen through Czech businessman Rudolf Fleischmann, an admirer of Mann’s work, who arranged Klaus’ naturalization to his Bohemian town of Prosec.

Golo wanted to take the opportunity to continue his studies in Prague, but soon stopped the experiment.

In 1935, when it became apparent that the Nazis were intending to strip Erika of her German citizenship, she asked Christopher Isherwood (1904 – 1986) if he would marry her so she could become a British citizen.

Above: Christopher Isherwood (left) and W.H. Auden (right)

He declined but suggested the gay poet W.H. Auden (1907 – 1973) who readily agreed to a marriage of convenience.

Erika and Auden never lived together, but remained on good terms throughout their lives and were still married when Erika died in 1969, leaving him with a small bequest in her will.

In November, Golo accepted a position to teach German and German literature at the University of Rennes.

Golo’s travels to Switzerland prove that his relationship with his father had become easier as Mann had learned to appreciate his son’s political knowledge.

But it was only when Golo helped edit his father’s diaries in later years that he realized fully how much acceptance he had gained.

In a confidential note to the German critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Golo wrote:

“It was inevitable that I had to wish his death, but I was completely broken heartedly when he passed away.”

In 1936, the Nazi government also revoked Mann’s German citizenship.

Mann also received Czechoslovak citizenship and passport that same year through Fleischmann, but after the Nazis took over Czechoslovakia, he then emigrated with Klaus to the United States where he taught at Princeton University.

Klaus Mann’s most famous novel, Mephisto, a thinly-disguised portrait of Gustaf, was written this year and published in Amsterdam.

Die Pfeffermühle opened again in Zürich and became a rallying point for German exiles.

Auden introduced Erika’s lover Therese Giehse to the English writer John Hampson.

Above: Therese Giehse (1898 – 1975)

Giehse and Hampson married so she could leave Germany.

Above: Howard Castor as John Hampson (1901 – 1955)

In the summer of 1937, Klaus met his partner for the rest of the year Thomas Quinn Curtis.

Erika moved to New York where Die Pfeffermühle reopened its doors again.

There she lived with Klaus, Giehse and Annemarie Scharzenbach, amid a large group of artists in exile.

In 1938 Monika and Jenö left Firenze for London, while Erika and Klaus reported on the Spanish Civil War.

Erika’s book School for Barbarians, a critique of Nazi Germany’s educational system, was published.

Mann completed Lotte in Weimar (1939) in which he returned to Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther (1774).

Katia wrote to Klaus (in Princeton) on 29 August that she was determined not to say any more unfriendly words about Monika and to be kind and helpful.

Monika was NOT her parents’ favourite.

In family letters and chronicles, Monika was often described as weird:

“After a three-week stay here (in Küsnacht) she is still the same old dull quaint Mönle (her nickname in the family), pilfering from the larder….”

Klaus’s novel Der Vulkan (Escape to Life), co-written with Erika, remains one of the 20th century’s most famous novels about German exiles during World War II.

Early that year Golo travelled to Princeton where his father worked.

Although war was drawing closer, he hesitantly returned to Zürich in August to become the editor of the migrant journal Maß und Wert (Measure and Value).

Monika and Jenö married on 2 March 1939.

On 6 March 1939, Michael married the Swiss-born Gret Moser (1916 – 2007) in New York.

With her he would have two sons, Frido and Toni, as well as an adopted daughter.

The outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939 prompted Mann to offer anti-Nazi speeches in German to the German people via the BBC.

Erika worked as a journalist in London, making radio broadcasts in German, for the BBC throughout the Blitz and the Battle of Britain.

Monika and Jenö left for Canada on the SS City of Benares, which on 17 September was sunk by a torpedo from a German submarine.

Above: SS City of Benares

Monika survived by clinging to a large piece of wood, but Jenö drowned.

After 20 hours Monika was rescued by a British ship and taken to Scotland.

Also in 1939, Elisabeth married the anti-Fascist Italian writer Giuseppe Borgese (1882 – 1952), 36 years her senior.

Above: Giuseppe Borgese

As a reaction to Hitler’s successes in the West in May 1940, Golo decided to fight against the Nazis by joining a Czech military unit on French soil.

Upon crossing the Swiss border into Annecy, France, he was arrested and brought to the French concentration camp of Les Milles, a brickyard near Aix-en-Provence.

Above: Camp des Milles, Annecy, France

In August, Golo was released through the intervention of an American committee.

On 13 September 1940, he undertook a daring escape from Perpignan across the Pyrenees to Spain with his uncle Heinrich, Heinrich’s wife Nelly Kröger, Alma Mahler-Werfel and Franz Werfel.

They crossed the Atlantic from Lisbon to New York in October on board the Greek Steamer Nea Hellas.

Once in the US, Golo was initially condemned to inactivity.

He stayed with his parents in Princeton, then in New York.

Monika reached New York on 28 October 1940 on the troopship Cameronia and joined her parents.

They showed little sympathy for her.

Monika’s traumatic loss of her husband and her attempts at a new beginning were ignored.

In October 1940, Mann began monthly broadcasts (“Deutsche Hörer“- “German listeners“), recorded in the US and flown to London where the BBC broadcasted them to Germany.

In his eight-minute addresses, Mann condemned Hitler and his “paladins” as crude Philistines completely out of touch with European culture.

“The war is horrible, but it has the advantage of keeping Hitler from making speeches about culture.”

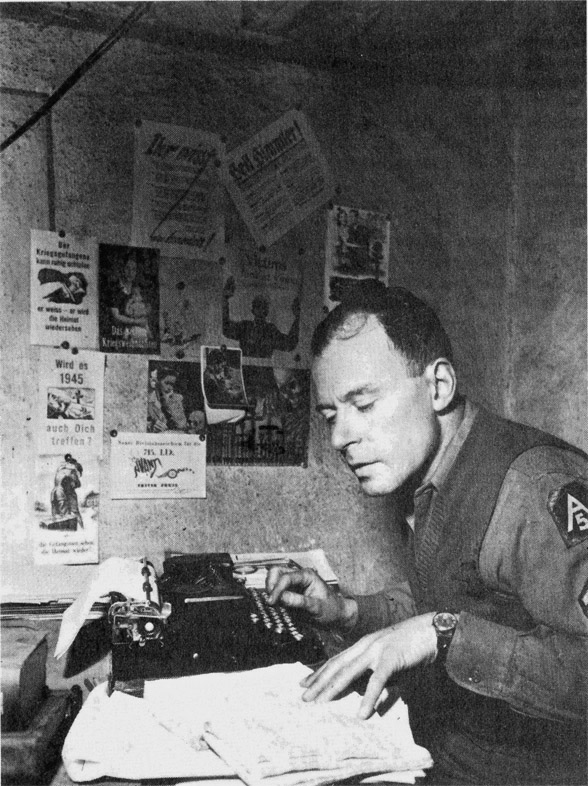

During the war, Klaus served as a Staff Sergeant of the 5th US Army in Italy.

In 1941, Elisabeth became an American citizen.

Mann was one of the few publicly active opponents of Nazism among German expatriates in America.

In 1942, the Mann family moved to Los Angeles, while Golo taught history at Olivet College in Michigan.

Between 1942 and 1947 Michael was a violinist in the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra.

Klaus became a US citizen in 1943 as Golo joined the US Army.

After basic training at Fort McClellan, Alabama, Golo worked at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)(forerunner of the CIA) in Washington DC.

Above: OSS insignia

As intelligence officer, it was his duty to collect and translate relevant information.

From 1943 to 1952 Monika lived in New York.

After attempts to renew her career as a pianist she turned to employment as a writer.

In April 1944, Golo was sent to London where he made radio commentaries for the German language division of the American Broadcasting Station (ABS).

On 23 June 1944, Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States.

After D-Day, Erika became a war correspondent attached to the Allied Forces advancing across Europe, reporting from recent battlefields in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

For the last months of World War II Golo worked for a military propaganda station in Luxembourg, then he helped organize the foundation of Radio Frankfurt.

During his journeys across Germany he was shocked at the extent of destruction, especially that caused by Allied bombing.

In the summer of 1945, Klaus was sent by Stars and Stripes to report from postwar Germany.

Erika entered Germany in June and was among the first Allied personnel to enter Aachen.

As soon as it was possible, she went to Munich to register a claim for the return of the Mann family home.

Arriving in Berlin on 3 July 1945, Erika was shocked at the level of destruction, describing the city as “a sea of devastation, shoreless and infinite.”

She was angry at the complete lack of guilt displayed by some of the German civilians and officials that she met.

During this period, as well as wearing an American uniform, Erika adopted an Anglo-American accent.

She attended the Nuremberg Trial each day from the opening session on 20 November 1945 until the court adjourned for Christmas.

Above: Nuremberg Courthouse where the Trials were held

She interviewed the defense lawyers and ridiculed their arguments in her reports and made clear that she thought the court was indulging the behaviour of the defendants, in particular Hermann Göring.

Above: Nuremberg Trial – Hermann Göring (far left, 1st row)

When the court adjourned for Christmas, Erika went to Zürich to spend time with Klaus, Betty Knox and Giehse.

Erika’s health was poor and on 1 January 1946 she collapsed and was hospitalized.

She was diagnosed with pleurisy.

After a spell recovering at a spa in Arosa, Erika returned to Nuremberg in March 1946 to continue covering the war crimes trial.

Above: Arosa

In May 1946, she left Germany for California to help look after Mann who was being treated for lung cancer.

That same year, Golo left the US Army by his own request, but nevertheless kept a job as civil control officer, watching the war crimes trial at Nuremberg in this capacity.

Also in 1946, Golo saw the publication of his first book of lasting value, a biography of the 19th century diplomat Friedrich von Gentz.

Above: Friedrich von Gentz (1764 – 1832)

Mann completed Doktor Faustus, the story of composer Adrian Leverkühn and the corruption of German culture before and during World War II in 1947.

From America, Erika continued to comment on and write about the situation in Germany.

She considered it a scandal that Göring had managed to commit suicide and was furious at the slow pace of the denazification process.

In particular, Erika objected to what she considered the lenient treatment of cultural figures who had remained in Germany throughout the Nazi period.

Her views on Russia and on the Berlin Airlift (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) led to her being branded a Communist in America.

In the autumn of 1947, Golo became an assistant professor of history at Claremont Men’s College in California.

In hindsight he recalled the nine-year engagement as “the happiest of my life“.

On the other hand he complained:

“My students are scornful, unfriendly and painfully stupid as never before.”

With the start of the Cold War, Mann was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism.

As a “suspected Communist“, Mann was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) who accused him as being “one of the world’s foremost apologists for Stalin and company“.

Both Klaus and Erika came under an FBI investigation into their political views and rumoured homosexuality.

On 21 May 1949, Klaus died in Cannes of an overdose of sleeping pills, though whether he committed suicide is uncertain, but he had become increasingly depressed and disillusioned over postwar Germany.

He is buried in Cannes’ Cimetière du Grand Jas.

Klaus’s death devastated Erika.

In an interview with the Toledo Blade (25 July 1949), Mann declared that he was not a Communist, but that Communism at least had some relation to the ideals of humanity and of a better future.

He said that the transition of Communism through revolution into an autocratic regime was a tragedy, while Nazism was only “devilish nihilism“.

Being in his own words a non-Communist rather than an anti-Communist, Mann openly opposed the HUAC allegations:

“As an American citizen of German birth I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends.

Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged ‘state of emergency’….

That is how it started in Germany.”

As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the Hollywood Ten (ten individuals working in Hollywood cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to answer questions about their alleged involvement with the Communist Party) and the firing of schoolteachers suspected of being Communists, Mann found “the media had been closed to him“.

In 1950, Mann met 19-year-old waiter Franz Westermeier, confiding in his diary:

“Once again this, once again love.”

(In 1975, when Mann’s diaries were published, creating a national sensation in Germany, the retired Westermeier was tracked down in the United States.

He was flattered to learn that he had been the object of Mann’s obsession, but was shocked at its depth.)

Due to the anti-communist red scare and numerous accusations from the McCarthy Committee, Mann was forced to quit his position as a consultant in Germanic literature at the Library of Congress in 1952, the Mann family left the US and moved back to Switzerland .

Erika began to help her father with his writing and became one of his closest confidantes.

Monika was granted US citizenship, but she had already planned to return to Europe.

In September she travelled with her sister Elisabeth’s family to Italy.

Elizabeth’s husband Giuseppe died that year and she would raise their two daughters, Angelica (b. 1941) and Dominica (b. 1944) as a single parent, though she would live with a new partner, Corrado Tumiati, from 1953 to 1967.

After a few months in Genoa, Bordighera and Rome, Monika fulfilled her desire to move to Capri, where she lived in the Villa Monacone with her partner, Antonio Spadaro.

In Capri she blossomed.

During this period she wrote five books and contributed regular features to Swiss, German and Italian newspapers and magazines.

Monika would remain in Capri for 32 years.

In March 1954, there were finally prospects of progress that Thomas Mann could buy a house in the old country road in the municipality of Kilchberg.

Above: Mann residence, Alten Landstrasse 39, Kilchberg

Kilchberg is an idyllic place, surrounded by meadows, vineyards and flower gardens.

The church on a hillside, with views over the Lake, dominate the place.

Mann would not live long to enjoy the home that was finally his.

Thomas Mann died on 12 August 1855, at age 80, of arteriosclerosis in a hospital in Zürich and is buried in Kilchberg.

Katia was not just the good spirit of the family, but the connection point that kept them all together.

She taught her children, was her husband’s manager, and was the family provider.

Katia outlived three of her children (Klaus, Erika and Michael) and her husband.

She died in 1980 and is buried in Kilchberg.

Erika died in 1969, age 63, of a brain tumor in a hospital in Zürich and is buried in Kilchberg.

Golo, after years of chronic overwork in his dual capacities of freelance historian and writer, died in Leverkusen in 1994, age 85.

A few days prior to his demise, Golo acknowledged his homosexuality in a TV interview:

“I did not fall in love often. I often kept it to myself. Maybe that was a mistake. It also was forbidden, even in America, and one had to be a little careful.”

According to Tilman Lahme, Golo’s biographer, he did not act out his homosexuality as openly as his brother Klaus but he had had love relationships since his student days.

His urn was buried in Kilchberg, but – in fulfillment of his last will – outside the communal family grave.

Monika, after her Capri partner Antonio died in 1986, spent her last years with Golo’s family in Leverkusen and died in 1992.

She is buried in the family grave in Kilchberg.

Elisabeth was in the mid-1960s the executive secretary of the board of Encyclopedia Britannica in Chicago.

At the age of 52, she had established herself as an international expert on the oceans.

Elisabeth was the founder and organizer of the first conference on the law of the sea, Peace in the Oceans, held in Malta in 1970.

From 1973 to 1982, she was part of the expert group of the Austrian delegation during the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

At the age of 59, in 1977, Elisabeth became a professor of political science in Canada’s Dalhousie University.

She became a Canadian citizen in 1983 and was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1988 at age 70.

Elisabeth kept up her teaching duties until age 81.

She died unexpectedly at the age of 83, during a skiing holiday in St. Moritz in 2002, and is buried in Kilchberg.

Michael, the youngest, made concert tours as a viola soloist until he was forced to give up professional music due to a neuropathy.

He then studied German literature at Harvard and later worked as a professor at the University of California in Berkeley.

Michael suffered from depression and died from the combined consumption of alcohol and barbituates in Orinda, California, in 1977.

He too lies in Kirchberg Cemetery, by the church on a hillside, with views over the Lake of Zürich, that dominates the town.

Kilchberg, 27 November 2017

It all began with an impulse.

As regular followers (both of them!) of my blogs (this one and Building Everest) know, I have, over the last year, retraced the “steps” of and written about the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli using the literary travel guide, Zwingli-Wege: Zu Fuss von Wildhaus nach Kappel am Albis – Ein Wander- und Lesebuch, by Marcel and Yvonne Steiner.

(See Canada Slim and…. the Privileged Place, the Monks of the Dark Forest, the Battle for Switzerland´s Soul, the Thundering Hollows, the Road to Reformation of this blog.)

For various reasons, I have not always been able to follow the Steiners’ suggested itineraries religiously.

Their 8th itinerary (Wädenswil to Zürich) has the hiker travel above the hills of Kilchberg rather than visit the town itself, which I felt remiss of the Steiners.

I went off-book and decided to explore the town.

Though Kilchberg may lack Zwingli connections, it is both an aestically pleasing and historically significant place worth lingering in for an afternoon.

A windswept day finds me asking a black cemetery caretaker for the location of the Mann burial plot and the English teacher/wordsmith in me sees the irony of the English word “plot” being both the chronology of a story and a final resting place.

I marvel at the history of this remarkable family and see irony in Thomas’ first real success as a writer was based on the fictional retelling of his own family’s past in Buddenbrooks, when his own family’s real history was equally, if not more, fascinating post-Buddenbrooks.

I am also left with many other reflections:

- I ponder the individual dilemmas Thomas, Erika, Klaus and Golo underwent in the expression of their sexual natures, and though in many Western nations in 2018 there is far greater openness and permissiveness towards non-heterosexual relationships, I can’t help but feel that there still remains stigma, confusion and miscommunication in mankind’s navigation of sexuality, gender and other boundaries towards loving relationships. (Perhaps a new Buddenbrooks of Thomas Mann and his offspring needs to be written to explores this ageless dilemma that keeps so much of humanity lost and alone.)

- I also wonder: What makes one person LGBT and another not? Thomas and Katia produced six children: two openly gay, one a closet gay, the other three – to the best of what is known – probably straight. So, what then determines a person’s sexual orientation? Genetics? Environment? Choice?

- And then there is the wonder of individuality where six children all grew up together yet lived very different lives from one another. How do we each develop our own separate personalities?

- I ask myself whether Thomas and Golo were right to conceal their hidden selves, yet when I see how imperfect the lives of the demonstrative Erika, Klaus and Monika were, I wonder if being themselves truly made them happier.

- I think of the Mann family and what comes to mind is conflict. Conflict between what they desired and what they were allowed. Conflict between their own expectations and the expectations of others. Conflict that results when speaking truth to power whether defying Nazis or HUAC. Conflict against disease, both physical and psychological. Conflict between their changing values and the inflexibility of old hierarchies being challenged.

The Manns were a restless family living in relentless times.

Though they now rest in peace, the world they helped create remains conflicted.

Sources: Wikipedia / Facebook / Ursula Kohler, Literarisches Reisefieber / Padraig Rooney, The Gilded Chalet: Off-piste in Literary Switzerland / Steffi Memmert-Lunau & Angelika Fischer, Zürich: Eine literarische Zeitreise / Albert Debrunner, Literaturführer Thurgau / Manfred Bosch, Die Manns am Bodensee / Thomas Sprecher & Fritz Gutbrodt, Die Famille Mann in Kilchberg / Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Haus, Kilchberg / Friedhof Gemeinde Kilchberg