Landschlacht, Switzerland, 8 October 2018

anachronic: not belonging to the time where one finds oneself

There are some places in the world where a person is immediately drawn to explore, either because of the sheer immensity of the place or because there is something truly remarkable there that cries out to be visited.

Kilchberg, a small town just south of Zürich on the western shore of the Lake of Zürich, fits neither description.

Kilchberg, unlike huge metropolises like London or Istanbul, does not offer surprises around every corner.

It takes only a well-planned excursion to see what little there is to see in this town: the Mann legacy of house and gravesites, the chocolate factory, and a museum dedicated to an anachronic man.

This post is this anachronic man’s story.

His museum is, to be frank, only of interest to those who can read fluently in German, for there are no descriptions in any other language within his last abode and his works seem to be only available in the Teutonic tongue.

The Museum, though named after the man who lived there, is not exclusively about him, as the scattered collections also focus on the bulk of the Klaus Mann family who lived and died in Kilchberg, as well as the local history of the community.

And those who run the Museum certainly do nothing to make a person want to make an effort to visit it, as the Museum is open only six hours a week on Wednesdays and Sundays from 2 to 5 pm.

(To be fair to the Museum, limited opening times and almost non-existent promotion are a typical problem of many museums in Switzerland.

The motivation to see such an attraction must have been driven from yourself, for it won’t have been created by anything the Swiss did.

For example, there is a Police and Criminal Museum in St. Gallen I knew nothing about until recently, despite my having worked in St. Gallen for the past eight years.

Now that I know it exists I am compelled to visit it soon, but its promised treasures are available for viewing at very limited opening times and with next to nothing and no one actively promoting it.)

As related in the previous post Canada Slim and the Family of Mann, my visit on 12 August 2018 to Kilchberg’s Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Museum was a third and final attempt to learn about Meyer.

And though Meyer is of little interest to most folks except those with either a passion for local history or Swiss literature, there are certain aspects about the life of Meyer with which I (and maybe you too, my gentle reader)can relate.

Conrad Ferdinand Meyer was born on 11 October 1825 in Zürich of patrician descent (i.e. nobility).

Above: Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825 – 1898)

His father, who died early, was a statesman and historian, while his mother was a highly cultured woman.

Throughout Meyer’s childhood two traits were observed that later characterized the man and the writer:

- He had a most scrupulous regard for neatness and cleanliness (a place for everything and everything in its place to the point of cleanliness nest to godliness).

- He lived and experienced more deeply in memory than in the immediate present.

(Blogger’s personal note:

I have always been surprised that any museum one visits always show the subject of the museum as an organized and tidy individual, when it has been my experience that those of a creative nature rarely are.)

Meyer suffered from bouts of mental illness, sometimes requiring hospitalization.

His mother, similarly but more severely affected, killed herself.

I am reminded of Lewis Carroll….

Once Meyer’s secondary education was completed, he took up the study of law, but history and the humanities were of greater interest to him.

He spent considerable amounts of time in Lausanne, Genève, Paris and Italy, immersed in historical research.

The two historians who influenced Meyer the most were Louis Vulliemin at Lausanne and Jacob Burkhardt in Basel whose book on the Culture of the Renaissance stimulated his imagination and interest.

Above: Jacob Burkhardt (1818 – 1897)

From Meyer’s travels in France and Italy, he derived much inspiration for the settings and characters of his historical novels.

Meyer’s master of realism was uncanny to the point that the reader is convinced that he lived what he wrote.

Reading his historical novels or narrative ballads the readers feel that they are living the past settings now.

What follows is the stuff of science fiction and immense improbability….

It is uncertain if time travel to the past is physically possible, but there are solutions in general relativity that allow for it, though the solutions require conditions not feasible with current technology.

The earliest science fiction work about backwards time travel is uncertain.

Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733) is a series of letters from British ambassadors in 1997 and 1998 to diplomats in the past, conveying the political and religious conditions of the future.

Above: Samuel Madden (1686 – 1765)

In the science fiction anthology Far Boundaries (1951), editor August Darleth claims that the earliest short story about time travel is “Missing One’s Coach: An Anachronism“, written for the Dublin Literary Magazine by an anonymous author in 1838.

The narrator of this short story waits under a tree for a coach to take him out of Newcastle, when he is transported in time over a thousand years.

The narrator encounters the Venerable Bede (672 – 735) in a monastery and explains to him the developments of the coming centuries.

Above: Bede the Venerable

The story never makes it clear whether these events are real or a dream.

There are a number of science fiction classics that suggest that the mind can transport a person back into the past.

Mark Twain (1835 – 1910)(Tom Sawyer / Huckleberry Finn), A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889):

Connecticut engineer Hank Morgan receives a severe blow to the head and is somehow transported in time and space to England during the reign of King Arthur.

After some initial confusion and his capture by one of Arthur’s knights, Hank realizes that he is actually in the past, and he uses his knowledge to make people believe that he is a powerful magician.

He attempts to modernize the past in order to make people’s lives better, but in the end he is unable to prevent the death of Arthur and an interdict against him by the Catholic Church of the time which grows fearful of his power….

Above: Mark Twain (pen name of Samuel Clemens)

Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989)(Rebecca / Jamaica Inn), The House on the Strand (1969):

Dick Young, has given up his job and been offered the use of the ancient Cornish house of Kilmarth by an old university friend Magnus Lane, a leading biophysicist in London.

He reluctantly agrees to act as a test subject for a drug that Magnus has secretly developed.

On taking it for the first time, Dick finds that it enables him to enter into the landscape around him as it existed during the early 14th century.

He becomes drawn into the lives of the people he sees there and is soon addicted to the experience….

Above: Daphne du Maurier

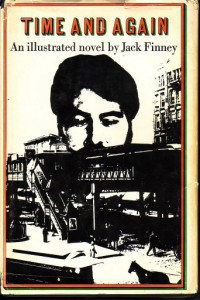

Jack Finney (1911 – 1995)(The Body Snatchers), Time and Again (1970)

In November 1970, Simon Morley, an advertising sketch artist, is approached by U.S. Army Major Ruben Prien to participate in a secret government project.

He is taken to a huge warehouse on the West Side of Manhattan, where he views what seem to be movie sets, with people acting on them. It seems this is a project to learn whether it is feasible to send people back into the past by what amounts to self-hypnosis—whether, by convincing oneself that one is in the past, not the present, one can make it so.

As it turns out, Simon (usually called Si) has a good reason to want to go back to the past—his girlfriend, Kate, has a mystery linked to New York City in 1882.

She has a letter dated from that year, mailed to an Andrew Carmody (a fictional minor figure who was associated with Grover Cleveland).

The letter seems innocuous enough—a request for a meeting to discuss marble—but there is a note which, though half burned, seems to say that the sending of the letter led to “the destruction by fire of the entire world“, followed by a missing word.

Carmody, the writer of the note, mentioned his blame for that incident.

He then killed himself.

Si agrees to participate in the project, and requests permission to go back to New York City in 1882 in order to watch the letter being mailed (the postmark makes clear when it was mailed).

The elderly Dr. E.E. Danziger, head of the project, agrees, and expresses his regret that he can’t go with Si, because he would love to see his parents’ first meeting, which also occurred in New York City in 1882.

The project rents an apartment at the famous Dakota apartment building.

Si uses the apartment as both a staging area and a means to help him with self-hypnosis, since the building’s style is so much of the period in which it was built and faces a section of Central Park which, when viewed from the apartment’s window, is unchanged from 1882.

Si is successful in going back to 1882….

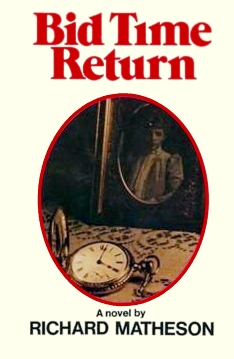

Richard Matheson (1926 – 2013)(I Am Legend), Bid Time Return (1975):

Richard Collier is a 36-year-old screenwriter who has been diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor and has decided, after a coin flip, to spend his last days hanging around the Hotel del Coronado.

Most of the novel represents a private journal he is continually updating throughout the story.

He becomes obsessed with the photograph of a famous stage actress, Elise McKenna, who performed at the hotel in the 1890s.

Through research, he learns that she had an overprotective manager named William Fawcett Robinson, that she never married and that she seemed to have had a brief affair with a mysterious man while staying at this hotel in 1896.

The more Richard learns, the more he becomes convinced that it is his destiny to travel back in time and become that mysterious man.

Through research, he develops a method of time travel that involves using his mind to transport himself into the past.

After much struggle, he succeeds.

At first, he experiences feelings of disorientation and constantly worries that he will be drawn back into the present, but soon these feelings dissipate.

He is unsure what to say to Elise when he finally does meet her, but to his surprise she immediately asks, “Is it you?”

(She later explains that two psychics told her she would meet a mysterious man at that exact time and place.)

Without telling her where (or, rather, when) he comes from, he pursues a relationship with her, while struggling to adapt himself to the conventions of the time.

Inexplicably, his daily headaches are gone, and he believes that his memory of having come from the future will ultimately disappear.

But Robinson, who assumes that Richard is simply after Elise’s wealth, hires two men to abduct Richard and leave him in a shed while Elise departs on a train.

Richard manages to escape and make his way back to the hotel, where he finds that Elise never left.

They go to a hotel room and passionately make love.

In the middle of the night, Richard leaves the room and bumps into Robinson.

After a brief physical struggle, Richard quickly runs back into the room, and he casually picks a coin out of his pocket.

Realizing too late that it is a 1970s coin, the sight of it pushes him back into the present.

At the end of the book, we find out that Richard died soon after.

A doctor claims that the time-traveling experience occurred only in Richard’s mind, the desperate fantasy of a dying man, but Richard’s brother, who has chosen to publish the journal, is not completely convinced….

There have been various accounts of persons who allegedly travelled through time reported by the press or circulated on the Internet.

These reports have generally turned out either to be hoaxes or to be based on incorrect assumptions, incomplete information, or interpretation of fiction as fact, many being now recognized as urban legends.

I am not suggesting that Meyer’s writing is superior to other historical writers.

Nor am I suggesting at all that Conrad Ferdinand Meyer was a time traveller, but rather he was an anachronic man, a man more at home in the memory of the past than the reality of the present.

Perhaps Meyer had even hypnotized himself into believing he had visited the past upon which he wrote so convincingly, but there is absolutely not a shred of proof to support such a wild hypothesis.

Above: Conrad Ferdinand Meyer

In 1875, Meyer settled at Kirchberg.

Meyer found his calling only late in life.

(He was 46 when his first work Hutten’s Last Days was published.)

Being fluently bilingual, Meyer wavered between French and German.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870 – 1871) cemented his final decision to write in German.

In Meyer’s novels, a great crisis releases latent energies and precipitates a catastrophe.

In the same manner, his own life, which before the War had been one of dreaming and experimenting, was stirred to the very depths by the events of 1870.

Meyer identified himself with the German cause and as a manifesto of his sympathies published the aforementioned Hutten’s Last Days in 1871.

After that his works appeared in rapid succession and were collected into eight volumes in 1912, fourteen years after his death.

The periods of the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries) and the Counter Reformation (1545 – 1648) furnished the subjects for most of his novels.

Most of his plots spring from the deeper conflict between freedom and fate and culminate in a dramatic crisis in which the hero, in the face of a great temptation, loses his moral freedom and is forced to fulfill the higher law of destiny.

His two most famous novels are gripping and provocative.

In Jürg Jenatsch (1876), which takes place in Swiss Canton Graubünden during the Thirty Years War (1618 – 1648), a Protestant minister and fanatic patriot who, in his determination to preserve the independence of Switzerland, does not shrink from murder and treason and in whom noble and base motives are strangely blended.

Above: Jörg Jenatsch (1596 – 1639)

In The Wedding of the Monk (1884), the renowned writer Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321) is introduced at the court of Cangrande in Verona, who narrates the strange adventure of a monk who, after the death of his brother, is forced by his father to break his monastic vows but who, instead of marrying the widow, falls in love with another young girl and runs blindly to his fate.

Above: Dante Aligheri

Meyer has written about the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (the night of 23 – 24 August 1572)(The Amulet), Thomas Becket (1119 – 1170)(The Saint), the Renaissance in Switzerland (Plautus in the Nunnery), France during the reign of Louis XIV (1638 – 1715)(The Suffering of a Boy), Charlemagne (742 – 814) and his Palace School (The Judge), and a tale of a great crisis in the life of Fernando d’Ávalos (1489 – 1525)(The Temptation of Pescara).

Yet if Meyer is remembered by the Swiss at all, it is as a master of narrative ballads, such as the aforementioned Hutten’s Last Days.

Meyer fascinated a man whose name is more recognizable to my gentle readers: psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

Freud in reflecting on Meyer’s life and works argued that there is a widespread existence among neurotics of a fable in which the present day parents are imposters, replacing a real and more aristocratic pair.

In repudiating the parents of today, the child is merely “turning away from the father whom he knows today to the father he believed in the earliest years of his childhood“.

He identified this psychological complex as the family romance.

Above: Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

(I am reminded of Joanne Greenberg’s semi-autobiographical novel – written under the pen name Hannah Green – I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, where Hannah shares a room with a memory-impaired girl who gives herself multiple sets of musical celebrity parents. “My father is (Igancy Jan) Paderewski (1860 – 1941) and my mother is Sophie Tucker (1886 – 1996).”

Greenberg’s novel was made into a film in 1977 and a play in 2004.

Perhaps it may have inspired Lynn Anderson’s 1967 song Rose Garden.)

Perhaps Meyer’s legacy of a father’s early death and a mother’s suicide made Meyer retreat from his grim reality and escape into the past.

Perhaps his pain made it possible for him to write so convincingly about a past he never personally witnessed except through his research.

Meyer’s genius is such that his readers are made to believe that they too are in the midst of the past stories he relates.

(If years rather than places were made into travel guides for time travellers I would suggest adapting Meyer’s works into such a form.

Imagine such a concept….

1313: A Travel Guide

“This time travel guide is invaluable for showing the prospective reader what dates to visit, what places are “happening” then, and all the dangers and delights of the time of the Battle of Gamelsdorf and the Siege of Rostock, the birth of the Infanta Maria of Portugal and the death of Austrian Saint Notburga.

Don’t leave your era without it!“)

Perhaps the difference, then as now, between a good artist and a great one is not only a question of talent….

Perhaps it is a question of successfully marketing that talent….

Though Meyer is lost in the shadows of time, perhaps a consideration of who he was and what he wrote is finally due.

Perhaps his story makes his Museum, even with German-only captions, worth a visit….

Sources: Wikipedia, www.kilchberg.ch

Above: The TARDIS, BBC Doctor Who