Landschlacht, Switzerland, 25 December 2018

Picture if you will a lake without compare, a Mediterranean oasis immersed in the savage grandeur of alpine mountains.

A merger of nature and history brought together to form a corner of Paradise, where sandstone meets spinosa, and lemons are kissed by oleander, where bay and cedar and orange dance together by shores where virgin waters gush out of living rock formed by ancient volcanoes encircled by periwinkles, heather, daisies and geraniums.

Where once the deer played, the wolf howled and the wild boar foraged and eagles and hawks once filled the skies, now ancient monasteries quietly crumble invisible as speed boats race and only the carp seem unimpressed by man’s ceaseless destructive cycles.

This is a land where the restless never lingered.

Through here marched Ligurians and Euganians, Etruscans and Enetites, Isarcs, Erectus and Celts.

Rome would drive an empire through here but all empires fall.

Let us speak mere mentions of the tribes Fabia and Polibia before they too fall before Ostrogoths, Goths and the Alemanni, who themselves were supplanted by Byzantines and Longobards.

Bishop saints and ancient churches stand and fall before Carolingian and Hun.

A lake that held secure in its bosom widows and heretics greeted Guelphs and Ghibellini and trembled as emperors rose and fell and Verona fought Venice.

Fall, Venice to Napoleon, the French to Austria.

Then cry the winds of freedom and join to form the new Rome, a proud Italy defiant regardless of the odds or whether king or Fascist, democrat or autocrat sits above all others in power and glory.

Upon this guarded Garda there is a spot of elegance and beauty, where magnificent vegetation thrives within a mild climate and where a famous, international sojourn lies among bright hills, large gardens, voluptuous villas and halycon hotels.

This is Gardone Riviera, a small town with a short history, designed by a German fighting for Italian independence whose peculiar impulses caused him to love the locale at once, inspiring him to construct hotels and found initiatives and cultivate contacts with the cosmopolitan world.

Soon would follow promenades and villas and the casino, but of all these nothing and no one enlivened this artificial tourist town more than Gabriele D’Annunzio: child prodigy of outstanding talent, poet, lover, man of society, father, journalist, novelist, playwright, pilot, francophile and art collector, war hero and conqueror, Fascist and anti-Fascist, architect and adventurer.

Ask not what did D’Annuzio do, for it is more remarkable how little he didn’t do.

On reading D’Annunzio’s tale and of his labour and the legacy of love that remains here, you may very well find yourself absolutely loving or loathing the man, but once you learn of this man you may find it difficult to forget the man or the mansion he built and named the Shrine of Italian Victories.

This is his story.

D’Annunzio was born in the township of Pescara, in the province of Abruzzo, the son of a wealthy landowner and mayor of the town Francesco Paolo Rapagnetta d’Annunzio (1831–1893) and his wife Luisa de Benedictis (1839-1917).

Above: Gabriele D’Annunzio Birthplace Museum, Pescara

His father had originally been born plain Rapagnetta (the name of his single mother), but at the age of 13 had been adopted by a childless rich uncle Antonio d’Annunzio.

Legend has it that he was initially baptized Gaetano and given the name of Gabriele later in childhood, because of his angelic looks.

His precocious talent was recognised early in life and he was sent to school at the Liceo Cicognini in Prato, Tuscany.

He published his first poetry while still at school at the age of 16 — a small volume of verses called Primo Vere (1879).

Influenced by Giosuè Carducci’s Odi barbare, he posed side by side some almost brutal imitations of Lorenzo Stecchetti, the fashionable poet of Postuma, with translations from the Latin.

His verse was distinguished by such agile grace that Giuseppe Chiarini on reading them brought the unknown youth before the public in an enthusiastic article.

In 1881, D’Annunzio entered the University of Rome, where he became a member of various literary groups, including Cronaca Bizantina, and wrote articles and criticism for local newspapers.

In those university years he started to promote Italian irredentism.

(Italian irredentism was a nationalist movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Italy with goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous ethnic Italians and Italian-speaking persons formed a majority, or substantial minority, of the population.)

He published Canto novo (1882), Terra vergine (1882), L’intermezzo di rime (1883), Il libro delle vergini (1884) and the greater part of the short stories that were afterwards collected under the general title of San Pantaleone (1886).

Canto novo contains poems full of pulsating youth and the promise of power, some descriptive of the sea and some of the Abruzzese landscape, commented on and completed in prose by Terra vergine, the latter a collection of short stories dealing in radiant language with the peasant life of the author’s native province.

Intermezzo di rime is the beginning of D’Annunzio’s second and characteristic manner.

His conception of style was new and he chose to express all the most subtle vibrations of voluptuous life.

Both style and contents began to startle his critics.

Some who had greeted him as an enfant prodige rejected him as a perverter of public morals, whilst others hailed him as one bringing a breath of fresh air and an impulse of new vitality into the somewhat prim, lifeless work hitherto produced.

Meanwhile, the review of Angelo Sommaruga perished in the midst of scandal and his group of young authors found itself dispersed.

Some entered the teaching career and were lost to literature.

Others threw themselves into journalism.

Gabriele D’Annunzio took this latter course, and joined the staff of the Tribuna, under the pseudonym of “Duca Minimo“.

Here he wrote Il libro d’Isotta (1886), a love poem, in which for the first time he drew inspiration adapted to modern sentiments and passions from the rich colours of the Renaissance.

Il libro d’Isotta is interesting, because in it one can find most of the germs of his future work, just as in Intermezzo melico and in certain ballads and sonnets one can find descriptions and emotions which later went to form the aesthetic contents of Il piacere, Il trionfo della morte and Elegie romane (1892).

D’Annunzio’s first novel Il piacere (1889, translated into English as The Child of Pleasure) was followed in 1891 by Giovanni Episcopo, and in 1892 by L’innocente (The Intruder).

These three novels made a profound impression.

L’innocente, admirably translated into French by Georges Herelle, brought its author the notice and applause of foreign critics.

His next work, Il trionfo della morte (The Triumph of Death)(1894) was followed soon by Le vergini delle rocce (1896) and Il fuoco (1900).

The latter is in its descriptions of Venice perhaps the most ardent glorification of a city existing in any language.

D’Annunzio’s poetic work of this period, in most respects his finest, is represented by Il Poema Paradisiaco (1893), the Odi navali (1893), a superb attempt at civic poetry, and Laudi (1900).

A later phase of D’Annunzio’s work is his dramatic production, represented by Il sogno di un mattino di primavera (1897), a lyrical fantasia in one act.

His Città Morta (1898) was written for Sarah Bernhardt.

Above: Poster of Sarah Bernhardt (1844 – 1923)

In 1898 he wrote his Sogno di un pomeriggio d’autunno and La Gioconda.

In the succeeding year La gloria, an attempt at contemporary political tragedy, met with no success, probably because of the audacity of the personal and political allusions in some of its scenes.

Francesca da Rimini (1901) was a perfect reconstruction of medieval atmosphere and emotion, magnificent in style, and declared by an authoritative Italian critic – Edoardo Boutet – to be the first real, if imperfect, tragedy ever given to the Italian theatre.

At the height of his success, D’Annunzio was celebrated for the originality, power and decadence of his writing.

Although his work had immense impact across Europe, and influenced generations of Italian writers, his fin de siècle works are now little known, and his literary reputation has always been clouded by his fascist associations.

Indeed, even before his fascist period, he had his strong detractors.

A New York Times review in 1898 of his novel The Intruder referred to him as “evil“, “entirely selfish and corrupt“.

Three weeks into its December 1901 run at the Teatro Constanzi in Rome, his tragedy Francesca da Rimini was banned by the censor on grounds of morality.

A prolific writer, his novels in Italian include Il piacere (The Child of Pleasure)(1889), Il trionfo della morte (The Triumph of Death)(1894) and Le vergini delle rocce (The Virgins of the Rocks)(1896).

He wrote the screenplay to the feature film Cabiria (1914) based on episodes from the Second Punic War.

D’Annunzio’s literary creations were strongly influenced by the French Symbolist school and contain episodes of striking violence and depictions of abnormal mental states interspersed with gorgeously imagined scenes.

One of D’Annunzio’s most significant novels, scandalous in its day, is Il fuoco (The Flame of Life)(1900), in which he portrays himself as the Nietzschean Superman Stelio Effrena, in a fictionalized account of his love affair with Eleonora Duse.

His short stories showed the influence of Guy de Maupassant.

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica wrote of him:

The work of d’ Annunzio, although by many of the younger generation injudiciously and extravagantly admired, is almost the most important literary work given to Italy since the days when the great classics welded her varying dialects into a fixed language.

The psychological inspiration of his novels has come to him from many sources—French, Russian, Scandinavian, German—and in much of his earlier work there is little fundamental originality.

His creative power is intense and searching, but narrow and personal.

His heroes and heroines are little more than one same type monotonously facing a different problem at a different phase of life.

But the faultlessness of his style and the wealth of his language have been approached by none of his contemporaries, whom his genius has somewhat paralysed.

In his later work, when he begins drawing his inspiration from the traditions of bygone Italy in her glorious centuries, a current of real life seems to run through the veins of his personages.

The lasting merit of D’Annunzio, his real value to the literature of his country, consists precisely in that he opened up the closed mine of its former life as a source of inspiration for the present and of hope for the future, and created a language, neither pompous nor vulgar, drawn from every source and district suited to the requirements of modern thought, yet absolutely classical, borrowed from none, and, independently of the thought it may be used to express, a thing of intrinsic beauty.

As his sight became clearer and his purpose strengthened, as exaggerations, affectations and moods dropped away from his conceptions, his work became more and more typical Latin work, upheld by the ideal of an Italian Renaissance.

In Italy some of his poetic works remain popular, most notably his poem “La pioggia nel pineto” (The Rain in the Pinewood), which exemplifies his linguistic virtuosity as well as the sensuousness of his poetry.

In 1883, D’Annunzio married Maria Hardouin di Gallese, and had three sons, Mario (1884-1964), Gabriele Maria “Gabriellino” (1886-1945) and Ugo Veniero (1887-1945), but the marriage ended in 1891.

In 1894, he began a love affair with the actress Eleonora Duse which became a cause célèbre.

Above: Eleonora Duse (1858 – 1924)

He provided leading roles for her in his plays of the time such as La città morta (The Dead City) (1898) and Francesca da Rimini (1901), but the tempestuous relationship finally ended in 1910.

After meeting the Marchesa Luisa Casati in 1903, he began a lifelong turbulent on again off again affair with Luisa, that lasted until a few years before his death.

Above: Luisa Casati (1881 – 1957)

In 1897 D’Annunzio was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for a three-year term, where he sat as an independent.

By 1910, his daredevil lifestyle had forced him into debt and he fled to France to escape his creditors.

There he collaborated with composer Claude Debussy on a musical play Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (The Martyrdom of St Sebastian)(1911), written for Ida Rubinstein.

The Vatican reacted by placing all of his works in the Index of Forbidden Books.

The work was not successful as a play, but it has been recorded in adapted versions several times, notably by Pierre Monteux (in French), Leonard Bernstein (sung in French, acted in English) and Michael Tilson Thomas (in French).

In 1912 and 1913, D’Annunzio worked with opera composer Pietro Mascagni on his opera Parisina, staying sometimes in a house rented by the composer in Bellevue, near Paris.

After the start of World War I, D’Annunzio returned to Italy and made public speeches in favor of Italy’s entry on the side of the Triple Entente of Russia, France and Great Britain.

Since taking a flight with Wilbur Wright in 1908, D’Annunzio had been interested in aviation.

Above: Wilbur Wright (1867 – 1912)

With the war beginning he volunteered and achieved further celebrity as a fighter pilot, losing the sight of an eye in a flying accident.

In February 1918, he took part in a daring, if militarily irrelevant, raid on the harbour of Bakar (known in Italy as La beffa di Buccari, literally the Bakar mockery), helping to raise the spirits of the Italian public, still battered by the Caporetto disaster.

Above: The harbour of Bakar

On 9 August 1918, as commander of the 87th fighter squadron “La Serenissima“, he organized one of the great feats of the war, leading nine planes in a 700-mile round trip to drop propaganda leaflets on Vienna.

This is called in Italian “il Volo su Vienna“(the flight over Vienna).

The war strengthened his ultra-nationalist and irredentist views and he campaigned widely for Italy to assume a role alongside her wartime allies as a first-rate European power.

Angered by the proposed handing over of the city of Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) whose population, outside the suburbs, was mostly Italian, at the Paris Peace Conference, on 12 September 1919, he led the seizure by 2,000 Italian nationalist irregulars of the city, forcing the withdrawal of the inter-Allied (American, British and French) occupying forces.

Above: Fiume, September 1919

The plotters sought to have Italy annex Fiume, but were denied.

Instead, Italy initiated a blockade of Fiume while demanding that the plotters surrender.

D’Annunzio then declared Fiume an independent state, the Italian Regency of Carnaro.

Above: Flag of Carnaro

The Charter of Carnaro foreshadowed much of the later Italian Fascist system, with himself as “Duce” (leader).

Some elements of the Royal Italian Navy, such as the destroyer Espero joined up with D’Annunzio’s local forces.

He attempted to organize an alternative to the League of Nations for selected oppressed nations of the world (such as the Irish, whom D’Annunzio attempted to arm in 1920) and sought to make alliances with various separatist groups throughout the Balkans (especially groups of Italians, though also some Slavic and Albanian groups) without much success.

D’Annunzio ignored the Treaty of Rapallo and declared war on Italy itself, only finally surrendering the city in December 1920 after a bombardment by the Italian navy.

D’Annunzio is often seen as a precursor of the ideals and techniques of Italian fascism.

His political ideals emerged in Fiume when he coauthored a constitution with syndicalist Alceste de Ambris, the Charter of Carnaro.

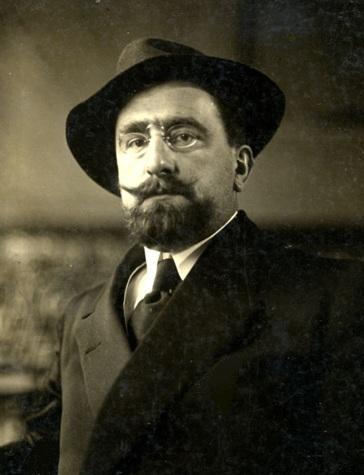

Above: Alceste De Ambris (1874 – 1934)

De Ambris provided the legal and political framework, to which D’Annunzio added his skills as a poet.

De Ambris was the leader of a group of Italian seamen who had mutinied and then given their vessel to the service of D’Annunzio.

The constitution established a corporatist state, with nine corporations to represent the different sectors of the economy (workers, employers, professionals) and a tenth (D’Annunzio’s invention) to represent the “superior” human beings (heroes, poets, prophets, supermen).

The Carta also declared that music was the fundamental principle of the state.

It was rather the culture of dictatorship that Benito Mussolini imitated and learned from D’Annunzio.

Above: Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

D’Annunzio has been described as the John the Baptist of Italian Fascism, as virtually the entire ritual of Fascism was invented by D’Annunzio during his occupation of Fiume and his leadership of the Italian Regency of Carnaro.

These included the balcony address, the Roman salute, the cries of “Eia, eia, eia! Alala!” taken from the Achilles’ cry in the Iliad, the dramatic and rhetorical dialogue with the crowd and the use of religious symbols in new secular settings.

It also included his method of government in Fiume: the economics of the corporate state, stage tricks, large emotive nationalistic public rituals and black-shirted followers, the Arditi, with their disciplined, bestial responses and strongarm repression of dissent.

He was even said to have originated the practice of forcibly dosing opponents with large amounts of castor oil, a very effective laxative, to humiliate, disable or kill them, a practice which became a common tool of Mussolini’s black shirts.

D’Annunzio advocated an expansionist Italian foreign policy and applauded the invasion of Ethiopia.

Above: Flag of Italian East Africa

After the Fiume episode, D’Annunzio retired to his home on Lake Garda and spent his latter years writing and campaigning.

Although D’Annunzio had a strong influence on the ideology of Benito Mussolini, he never became directly involved in fascist government politics in Italy.

As John Whittam notes in his essay “Mussolini and The Cult of the Leader“:

This famous poet, novelist and war hero was a self-proclaimed Superman.

He was the outstanding interventionist in May 1915 and his dramatic exploits during the war won him national and international acclaim.

In September 1919 he gathered together his ‘legions’ and captured the disputed seaport of Fiume.

He held it for over a year and it was he who popularised the black shirts, the balcony speeches, the promulgation of ambitious charters and the entire choreography of street parades and ceremonies.

He even planned a march on Rome.

One historian had rightly described him as the ‘First Duce’ and Mussolini must have heaved a sigh of relief when he was driven from Fiume in December 1920 and his followers were dispersed.

But he remained a threat to Mussolini and in 1921 Fascists like Balbo seriously considered turning to him for leadership.

In contrast Mussolini vacillated from left to right at this time.

Although Mussolini’s fascism was heavily influenced by the Carta del Carnaro, the constitution for Fiume written by Alceste De Ambris and D’Annunzio, neither wanted to play an active part in the new movement, both refusing when asked by Fascists to run in the elections of 15 May 1921.

D’Annunzio was seriously injured when he fell out of a window on 13 August 1922.

Shortly before the march on Rome, he was pushed out of a window by an unknown assailant, or perhaps simply slipped and fell out himself while intoxicated.

He survived but was badly injured and only recovered after Mussolini had been appointed Prime Minister.

Subsequently the planned “meeting for national pacification” with Francesco Saverio Nitti and Mussolini was cancelled.

Above: Francesco Nitti (1868 – 1953), Prime Minister (1919 – 1920)

The incident was never explained and is considered by some historians an attempt to murder him, motivated by his popularity.

Despite D’Annunzio’s retreat from active public life after this event, the Duce still found it necessary to regularly dole out funds to D’Annunzio as a bribe for not re-entering the political arena.

When asked about this by a close friend, Mussolini purportedly stated:

“When you have a rotten tooth you have two possibilities open to you:

Either you pull the tooth or you fill it with gold.

With D’Annunzio, I have chosen for the latter treatment.”

In 1924 D’Annunzio was ennobled by King Victor Emmanuel III and given the hereditary title of Prince of Montenevoso (Italian: Principe di Montenevoso).

Above: Italian King Victor Emmanuel III (1869 – 1947)

Nonetheless, D’Annunzio kept attempting to intervene in politics almost until his death in 1938.

He wrote to Mussolini in 1933 to try to convince him not to take part in the Axis pact with Hitler.

Above: Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945)

In 1934, he tried to disrupt the relationship between Hitler and Mussolini after their meeting, even writing a satirical pamphlet about Hitler.

Again, in September 1937, D’Annunzio met with the Duce at the Verona train station to convince him to leave the Axis alliance.

Mussolini in 1944 admitted to have made a mistake not following his advice.

In 1937, D’Annunzio was made president of the Royal Academy of Italy.

D’Annunzio died in 1938 of a stroke at his home in Gardone Riviera.

He was given a state funeral by Mussolini and was interred in a magnificent tomb constructed of white marble at Il Vittoriale degli Italiani.

D’Annunzio’s life and work are commemorated in a museum, Il Vittoriale degli Italiani.

The Vittoriale degli italiani (English translation: The shrine of Italian victories) is a hillside estate in the town of Gardone Riviera overlooking Lake Garda.

It is where the Italian writer Gabriele d’Annunzio lived after his defenestration in 1922 until his death in 1938.

The estate consists of the residence of d’Annunzio called the Prioria (priory), an amphitheatre, the protected cruiser Puglia set into a hillside, a boathouse containing the MAS vessel used by D’Annunzio in 1918 and a circular mausoleum.

Its grounds are now part of the Grandi Giardini Italiani.

The Prioria itself consists of a number of rooms opulently decorated and filled with memorabilia.

Notable are the two waiting rooms: one for welcome guests, one for unwelcome ones.

It is the latter where Benito Mussolini was sent to on his visit in 1925.

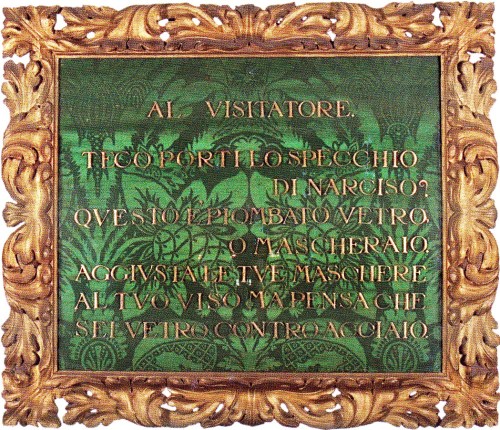

A phrase was inscribed specifically for him above the mirror:

- To the visitor:

- Are you bringing Narcissus’ mirror?

- This is leaded glass, my mask maker.

- Adjust your mask to your face,

- But mind that you are glass against steel.

The leper’s room is where D’Annunzio’s wake was held upon his death.

Its name comes from the fact that D’Annunzio felt that he was being spurned by the government due to their continued efforts to keep him in Gardone, rather than possibly in the limelight in Rome.

The relic room holds a large collection of religious statues and images of different beliefs, purposely placed together to make a statement about the universal character of spirituality.

The inscription on the inner wall reads:

- As there are five fingers on a hand, there are only five mortal sins.

D’Annunzio wished to make clear hereby that he didn’t believe that lust and greed should be considered sinful.

A most unlikely relic is the distorted steering wheel of racing speedboat Miss England II, donated after the coppa dell oltranza powerboating trophy, organized under D’Annunzio patronage, was held in 1931.

Miss England II had crashed in a world speed record attempt, killing her pilot, Sir Henry Seagrave in 1930 (though winning the record nevertheless) and was rebuilt to race and win at Lake Garda the following year with Kaye Don at the helm.

D’Annunzio, who was a syncretist (believer in all religions), deemed the distorted steering wheel “a relic of the religion of courage“.

The amphitheatre is the first major structure one comes across after entering the estate and was clearly based upon classic models, the architect Maroni even visiting Pompeii for inspiration.

Its location, like the other buildings of the Vittoriale undeniably offers a majestic view of Lake Garda, it is still used for performances today.

References to the Vittoriale range from a “monumental citadel” to a “fascist lunapark”, the site inevitably inheriting the controversy surrounding its creator.

He planned and developed it himself, adjacent to his villa at Gardone Riviera on the southwest bank of Lake Garda, between 1923 and his death.

Now a national monument, it is a complex of military museum, library, literary and historical archive, theatre, war memorial and mausoleum.

The museum preserves his torpedo boat MAS 96 and the SVA-5 aircraft he flew over Vienna.

The house, Villa Cargnacco, had belonged to the German art historian of the Italian Renaissance Henry Thode from whom it was confiscated by the Italian state, including artworks, a collection of books, and a piano which had belonged to Liszt.

D’Annunzio rented it in February 1921 and within a year reconstruction started under the guidance of architect Giancarlo Maroni.

Due to D’Annunzio’s popularity and his disagreement with the fascist government on several issues, such as the alliance with Nazi Germany, the fascists did what they could to please D’Annunzio in order to keep him away from political life in Rome.

Part of their strategy was to make huge funds available to expand the property, to construct or modify buildings and to create the impressive art and literature collection.

In 1924, the airplane that D’Annunzio used for his pamphleteering run over Vienna during World War I was brought to the estate, followed in 1925 by the MAS naval vessel used by him to taunt the Austrians in 1918 in the Beffa di Buccari.

In the same year the protected cruiser Puglia was hauled up the hill and placed in the woods behind the house and the property was expanded by acquisition of surrounding lands and buildings.

Jutting out of one of the hilltops the cruiser Puglia makes a surreal sight.

It was placed there, with its bow pointing in the direction of the Adriatic, “ready to conquer the Dalmatian shores”.

The ship was equipped with a main armament of four 15 cm (5.9 in) and six 12 cm (4.7 in) guns, and she could steam at a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

88.25 meters (289.5 ft) long overall and had a beam of 12.13 m (39.8 ft) and a draft of 5.45 m (17.9 ft).

She displaced up to 3,110 metric tons (3,060 long tons; 3,430 short tons) at full load.

Her propulsion system consisted of a pair of vertical triple-expansion engines, with steam supplied by four cylindrical water-tube boilers.

Puglia was capable of steaming at a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

The ship had a cruising radius of about 2,100 nautical miles (3,900 km; 2,400 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

She had a crew of between 213 to 278.

Puglia was armed with a main battery of four 15 cm (5.9 in) L/40 guns mounted singly, with two side by side forward and two side by side aft.

Six 12 cm (4.7 in) L/40 guns were placed between them, with three on each broadside.

Light armament included eight 57 mm (2.2 in) guns, eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and a pair of machine guns.

She was also equipped with two 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes.

Puglia was protected by a 25 mm (0.98 in) thick deck.

Her conning tower had 50 mm thick sides.

Puglia served abroad for much of her early career, including periods in South American and East Asian waters.

She saw action in the Italo-Turkish War in 1911–1912, primarily in the Red Sea.

During the war she bombarded Ottoman ports in Arabia and assisted in enforcing a blockade on maritime traffic in the area.

She was still in service during World War I.

The only action in which she participated was the evacuation of units from the Serbian Army from Durazzo in February 1916.

During the evacuation, she bombarded the pursuing Austro-Hungarian Army.

After the war, Puglia was involved in the occupation of the Dalmatian coast, and in 1920 her captain was murdered in a violent confrontation in Split with Croatian nationalists.

The old cruiser was sold for scrapping in 1923.

While the ship was being dismantled, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini donated the ship’s bow section to the writer and ardent nationalist Gabriele D’Annunzio, who had it installed at his estate as part of the Vittoriale degli italiani museum.

In 1926, the government donated an amount of 10 million lire, which allowed a considerable enlargement of the Villa, with a new wing named the Schifamondo.

In 1931, construction was started on the Parlaggio, the name for the amphitheatre.

The mausoleum was designed after D’Annunzio’s death but not actually built until 1955 and D’Annunzio’s remains were finally brought there in 1963.

The circular structure is situated on the highest point on the estate.

It contains the remains of men who served D’Annunzio and died during the Fiume incident and d’Annunzio himself.

Luigi Barzini once argued that Gabriele D’Annunzio was perhaps more Italian than any other Italian, because for Italians the first purpose of life is to make life acceptable.

Life in the raw is notoriously meaningless and frightening, therefore dull and insignificant moments in life must be made decorous and agreeable with decoration and ritual.

Everything must be made to sparkle whether it be a simple meal, an ordinary transaction, a dreary speech, or a cowardly capitulation, all must be embellished and ennobled with euphemisms, adornments and pathos.

Not because Italians find life rewarding and exhilarating but because Italians are a pessimistic, realistic, resigned and frightened people.

Even though D’Annunzio was a penniless provincial son of a small merchant, he lived like a Renaissance prince, a figure of voluptuousness, surrounding himself with a gaudy clutter of antiques, brocades, rare Oriental perfumes and flamboyant, inexpensive jewellery.

He dressed like a London Beau Brummel, slept with duchesses, world famous actresses and mad Russian ladies, wrote exquisitely wrought prose and poetry, rode to hounds, hounded Italian politics with extreme right politics.

Like his role model Cola di Rienzo, D’Annunzio believed that facade and reality were one and the same thing.

Thus in seeking to disguise an ordinary origin in extraordinary finesse, D’Annunzio would lead an exceptional life.

As much as I am disgusted by his aggressive nationalism and appalled by his reckless reputation as a womanizer, D’Annunzio lived a life of overheated emotion and sexuality and was a man of original talent remarkable not only in his time but as well in the ambigous legacy he left behind.

I cannot but notice.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Gabriele d’Annunzio: An Exceptional Life (Skira editore Vittoriale souvenir album) / The Rough Guide to Italy / Writers: Their Lives and Works (Dorling Kindersley) / Luigi Barzini, The Italians