Landschlacht, Switzerland, 15 January 2018

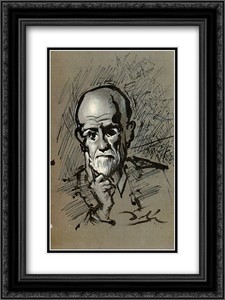

I have spoken of Sigmund Freud before.

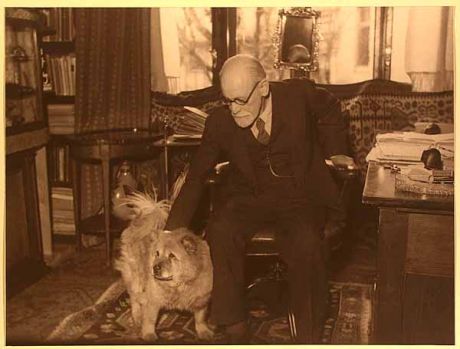

Above: Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

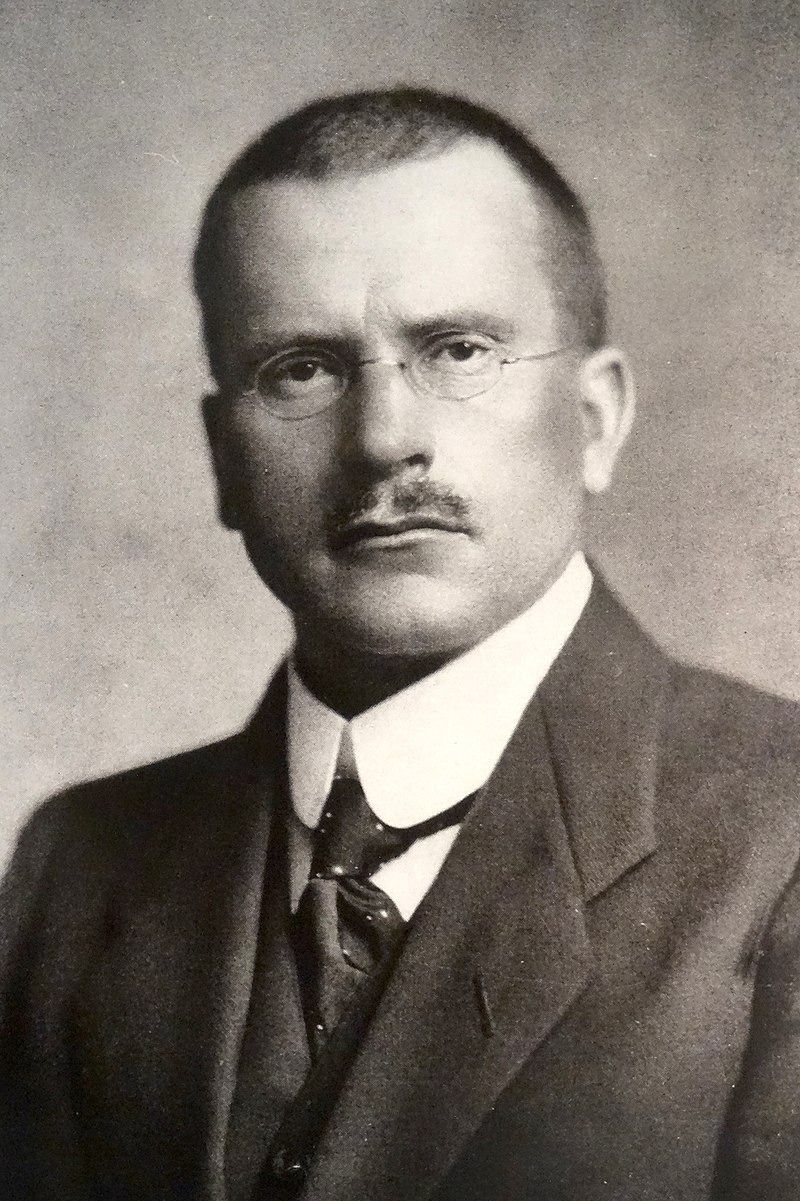

And I must confess to a reluctance to like the man and his theories, for the same reason I am reluctant to embrace Charles Darwin and his theories:

Above: Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882)

Admitting there may be some validity to their theories is to admit to embarrassing revelations about myself.

Maybe we did evolve from single cell organisms and apes through a process of millions of millennia, so perhaps a belief in an invisible God that created the world in seven calendar days and could bring me eternal life after death is less plausible than the acceptance that I am just the tiniest particle in the vast expanse of time, space and reality.

And maybe, just maybe, there might be more to Freud and his theories than just the scandalous unproven idea that he liked to watch his mother pee, and that some of the ways we think about ourselves and how our unconscious, dreams and sexuality as suggested by Freud’s theories might be somewhat uncomfortably plausible.

My wife, the medical doctor in the house, has, of course, had exposure during her studies to the work and thought of Freud in regards to child development.

During her internship in a Vienna practice she visited the Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna – there are three Freud Museums, the other two are in Pribor, Czech Republic, and in London – which she immensely enjoyed.

Above: Sigmund Freud Museum, Bergstrasse 19, Vienna

Knowing that she had some free time before her medical conference in London in October 2017, Ute was determined that she would visit the Freud Museum here as well.

Above: Freud Museum, London

I have already written extensively of some of the many sites we saw in London during our week there together and suffice to say that what I have said is a mere drop in the bucket of all that has been said or could be said by others.

(For more on London, please see:

- Canada Slim and the Body Snatchers /….and the Danger Zone / ….and the Paddington Arrival / ….and the Street Walked Too Often /….Underground / …. and the Outcast /…. and the Wonders on the Wall / …. and the Calculated Cathedral / …. and the Right Man / …. and the Queen’s Horsemen / …. and the Royal Peculiar / …. and the Uncertainty Principle / …. and the Museum of Many / …. and the Lamp Ladies / …. and the Breviary of Bartholomew of this blog. )

London, England, 25 October 2017

In North London, perched on a hill to the west of Hampstead Heath, Hampstead Village developed into a fashionable spa in the 18th century and was not much altered thereafter.

Being a sloping site deterred Victorian property speculators and put off the railway companies from destroying much of Hampstead.

Later it became one of the city’s most celebrated literary quartiers and even now retains a reputation as a bolt hole for high-profile intelligentsia and discerning pop stars.

The steeply inclined High Street, lined with posh shops and arty cafés, flaunts the area’s ever-increasing wealth, but far more appealing are the extensive, picturesque and precipitious maze of alleyways and steps radiating both east and west of Heath Street.

Proximity to Hampstead Heath is the true joy of the territory, for this mixture of woodland, smooth pasture and landscaped garden is simply the most exhilirating patch of greenery in London.

Over the years, countless writers, artists and politicos have been drawn to Hampstead, which has more blue plaques commemorating its residents than any London borough.

John Constable lived here in the 1820s, trying to make ends meet for his wife and seven children, painting cloud formations on the Heath.

Above: John Constable (1776 – 1837)

John Keats (1795 – 1821) moved into Well Walk in 1817 to nurse his dying brother then moved to a semi-detached villa, fell in love with the girl next door, bumped into Coleridge on the Heath and in 1821 went to Rome to die.

Above: Keats House, Spanish Steps, Rome

(I have visited Keats House in Rome and in London.)

Above: Keats House, Hampstead, North London

In 1856, Karl Marx finally achieved respectability when he moved into Grafton Terrace.

Above: Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)

Robert Louis Stevenson stayed here when he was 23 suffering from tuberculosis and thought Hampstead was “the most delightful place for air and scenery“.

Above: Robert Louis Stevenson (1850 – 1894)

Author H.G. Wells (1866 – 1946) lived on Church Row for three years just before World War One, while photographer Cecil Beaton (1904 – 1980) attended primary school and was bullied by author Evelyn Waugh (1903 – 1966) – the start of a lifelong feud.

The composer Edward Elgar became a special constable during the war, joining the Hampstead Volunteer Reserve.

Above: Edward Elgar (1857 – 1934)

Writer D.H. Lawrence (1885 – 1930) and his German wife Frieda (1879 – 1956) watched the first Zeppelin raid on London from the Heath in 1915 and decided to leave.

Above: Memorial, Camberwell Old Cemetery, London, to 21 civilians killed by Zeppelin bombings in 1917

Following the war, Lawrence’s friend and fellow writer Katherine Mansfield, lived for a couple of years in a big grey house overlooking the Heath, which she nicknamed “the Elephant“.

Above: Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

Actor Dirk Bogarde was born in a taxi in Hampstead in 1921.

Above: Dirk Bogarde (1921 – 1999)

Poet Stephen Spender spent his childhood in “an ugly house” on Frognal and went to school locally.

Above: Stephen Spender (1909 – 1995)

Elizabeth Taylor was born in Hampstead in 1932 and came back to live here in the 1950s during her first marriage to Richard Burton.

Above: Elizabeth Taylor (1932- 2011)

In the 1930s, Hampstead’s modernist Isokon Building, a block of flats on Lawn Road, became something of an artistic hangout, particularly the drinking den, the Isobar.

Above: Isokon Flats, Hampstead, North London

Architect Walter Gropius (1883 – 1969) and artists Henry Moore (1898 – 1986), Barbara Hepworth (1903 – 1975) and her husband Ben Nicholson (1894 – 1982) all lived here.

Another tenant, Agatha Christie (1890 – 1976), compared the exterior of Isokon to a giant ocean liner.

Architect Ernö Goldfinger (1902 – 1987) built his modernist family home at 2 Willow Road and local resident Ian Fleming named James Bond’s adversary after him.

Above: 2 Willow Road, Hampstead, North London

Mohammed Ali Jinnah abandoned India for Hampstead in 1932, living a quiet life with his daughter and his sister and working as a lawyer.

Above: Mohammed Ali Jinnah (1876 – 1948)

George Orwell lived rent-free above Booklovers’ Corner, a bookshop on South End Road, in 1934, in return for services in the shop in the afternoon.

Keep the Aspidistra Flying has many echoes of Hampstead and its characters.

Artist Piet Mondrian escaped to Hampstead from Nazi-occupied Paris, only to be bombed out a year later, after which he fled to New York.

Above: Piet Mondrian (1872 – 1944)

Nobel Prize-winning writer Elias Canetti (1905 – 1994) was another refugee from Nazi-occupied Europe as was painter/poet Oskar Kokoschka (1886 – 1980).

General Charles de Gaulle (1890 – 1970) got first-hand experience of Nazi air raids when he lived on Frognal with his wife and two daughters.

Ruth Ellis (1926 – 1955), the last woman to be hanged in Britain in 1955, shot her lover outside Magdala Tavern by Hampstead Heath Train Station.

Sid Vicious (1957 – 1979) and Johnny Rotten lived in a squat on Hampstead High Street in 1976.

John le Carré lived here in the 1970s and 1980s and set a murder in Smiley’s People on Hampstead Heath.

Above: John le Carré

Former Labour leader Michael Foot lived in a house he bought in 1945 with his redundancy cheque from The Evening Standard until the age of 96.

Above: Michael Foot (1913 – 2010)

Today comedian Ricky Gervais, director Ridley Scott, footballer Thierry Henry and pop stars Boy George and Harry Styles have homes here.

And it was here in Hampstead where the Austrian neurologist and the father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud spent the last year of his life, having reluctantly left Vienna following the Nazi Anschluss (annexation).

In January 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany and Freud’s books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed.

Freud remarked to Ernest Jones:

“What progress we are making!

In the Middle Ages they would have burned me.

Now, they are content with burning my books.“

Freud was wrong.

The Nazis would have gassed and incinerated him too in one of their death camps – as happened to millions of other Jews.

Freud continued to underestimate the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938, in which Nazi Germany annexed Austria, and the outbreaks of violent anti-Semitism that ensued.

Ernest Jones, the president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), flew into Vienna from London via Prague on 15 March determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain.

Above: Ernest Jones (1879 – 1958)

That same month Nazi S.A. men invaded Freud’s home searching for valuables.

Freud’s “Old Testament” frown frightened them away, though daughter Anna was detained by the Gestapo a whole day.

This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave Austria.

Jones left for London the following week with a list provided by Freud of the party of émigrés for whom immigration permits would be required.

Back in London, Jones used his personal acquaintance with the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, to expedite the granting of permits.

There were seventeen in all and work permits were provided where relevant.

Jones also used his influence in scientific circles, persuading the president of the Royal Society, Sir William Bragg, to write to the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, requesting to good effect that diplomatic pressure be applied in Berlin and Vienna on Freud’s behalf.

Freud also had support from American diplomats, notably his ex-patient and American ambassador to France, William Bullitt.

Bullitt alerted US President Roosevelt to the increased dangers facing the Freuds, resulting in the American consul-general in Vienna, John Cooper Wiley, arranging regular monitoring of Berggasse 19.

He also intervened by phone call during the Gestapo interrogation of Anna Freud.

The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938.

Freud’s grandson Ernst Halberstadt and Freud’s son Martin’s wife and children left for Paris in April.

Freud’s sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud’s daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.

By the end of the month, arrangements for Freud’s own departure for London had become stalled, mired in a legally tortuous and financially extortionate process of negotiation with the Nazi authorities.

Under regulations imposed on its Jewish population by the new Nazi regime, a Kommissar was appointed to manage Freud’s assets and those of the IPA whose headquarters were nearby Freud’s home.

Freud was allocated to Dr. Anton Sauerwald, who had studied chemistry at Vienna University under Professor Josef Herzig, an old friend of Freud’s.

Sauerwald read Freud’s books to further learn about him and became sympathetic towards his situation.

Though required to disclose details of all Freud’s bank accounts to his superiors and to arrange the destruction of the historic library of books housed in the offices of the IPA, Sauerwald did neither.

Instead he removed evidence of Freud’s foreign bank accounts to his own safe-keeping and arranged the storage of the IPA library in the Austrian National Library where it remained until the end of the war.

Though Sauerwald’s intervention lessened the financial burden of the “flight” tax on Freud’s declared assets, other substantial charges were levied in relation to the debts of the IPA and the valuable collection of antiquities Freud possessed.

Unable to access his own accounts, Freud turned to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the most eminent and wealthy of his French followers, who had travelled to Vienna to offer her support and it was she who made the necessary funds available.

This allowed Sauerwald to sign the necessary exit visas for Freud, his wife Martha and daughter Anna.

Above: Anton Sauerwald

They left Vienna on the Orient Express on 4 June, accompanied by their housekeeper and a doctor, arriving in Paris the following day where they stayed as guests of Princess Bonaparte before travelling overnight to London arriving at Victoria Station on 6 June.

Freud was immediately Britain’s most famous Nazi exile.

Among those soon to call on Freud to pay their respects were Salvador Dalí, Stefan Zweig, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf and H. G. Wells.

Representatives of the Royal Society called with the Society’s Charter for Freud, who had been elected a Foreign Member in 1936, to sign himself into membership.

Princess Bonaparte arrived towards the end of June to discuss the fate of Freud’s four elderly sisters left behind in Vienna.

Above: Princess Marie Bonaparte (1882 – 1962)

Her subsequent attempts to get them exit visas failed and they would all die in Nazi concentration camps.

In early 1939 Sauerwald arrived in London in mysterious circumstances where he met Freud’s brother Alexander.

He was tried and imprisoned in 1945 by an Austrian court for his activities as a Nazi Party official.

Responding to a plea from his wife, Anna Freud wrote to confirm that Sauerwald “used his office as our appointed commissar in such a manner as to protect my father“.

Her intervention helped secure his release from jail in 1947.

In the Freuds’ new home, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, North London, Freud’s Vienna consulting room was recreated in faithful detail.

He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness.

He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and in English the following year and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis which was published posthumously.

The ground floor of the museum houses Freud’s study, library, hall and the dining room.

Freud’s study and library look exactly as they did when Freud lived here – they were modelled on his Berggasse 19 flat in Vienna:

The large collection of antiquities and the psychiatrist’s couch, sumptiously draped in an opulent Iranian rug, were all brought here from Vienna.

Upstairs on the first floor in the video room there is some old footage of the Freud family.

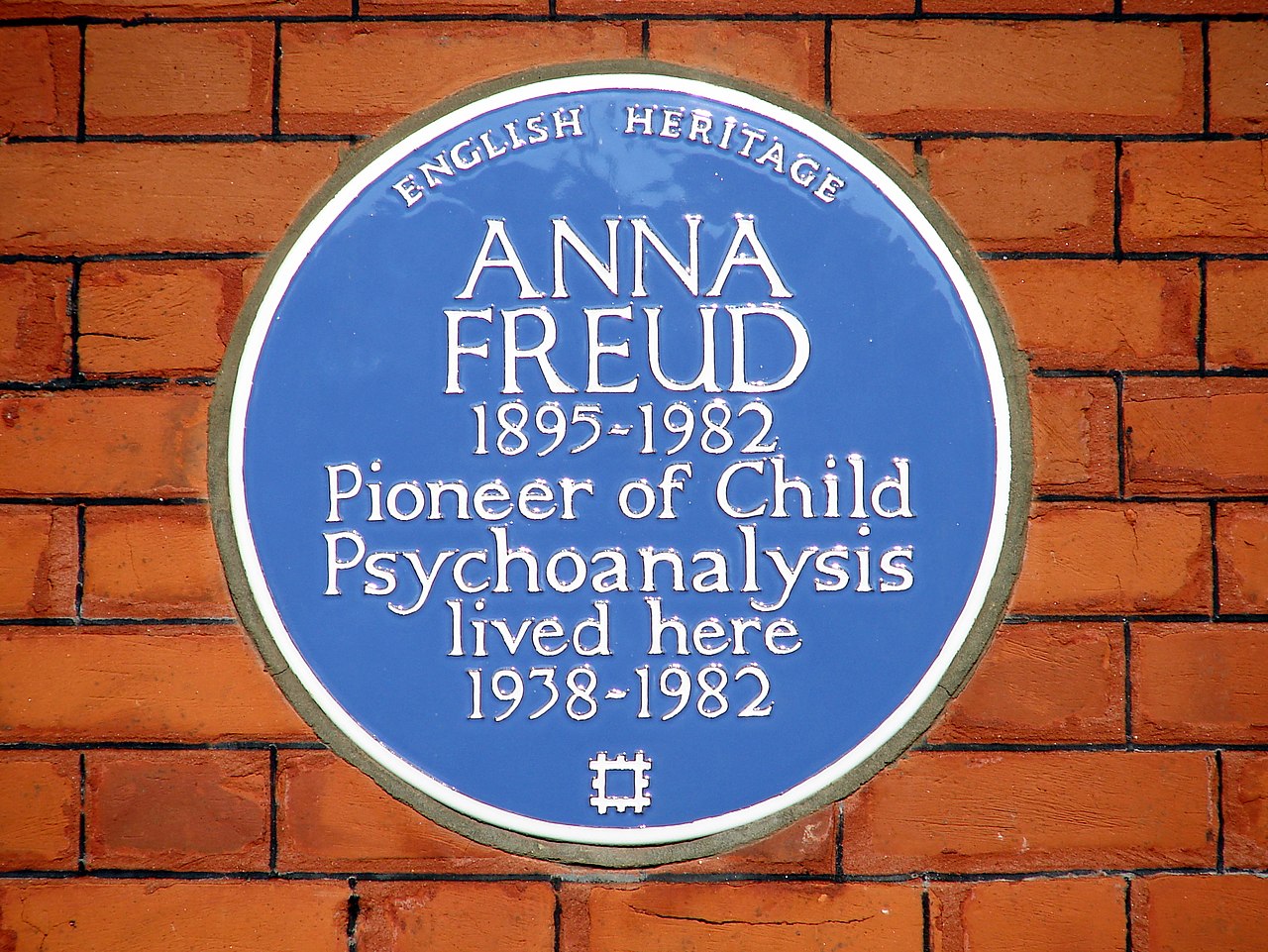

While another room is dedicated to Sigmund’s favourite daughter, Anna Freud, herself an influential child analyst.

There is a temporary exhibitions room which hosts alternate contemporary art and Freud-themed exhibitions.

Art installations often use several rooms within the museum, such as the 2001/02 exhibition “A Visit to Freud’s” by an Austrian female photographer Uli Aigner.

Many areas such as the kitchen and Anna Freud’s consulting room are out of public view and have been converted into offices.

The house had only finished being built in 1920 in the Queen Anne Style.

A small sun room (loggia) in a modern style was added at the rear by his architect son Ernst Ludwig Freud that same year so Sigmund could sit out and enjoy the garden.

It has since been enclosed and now serves as the museum shop, which flogs merchandise from silk scarves inspired by his patients’ artwork to novelty Freudian slippers, plus a good selection of books, including those used to research this post.

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth.

Freud initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed.

Freud consulted the dermatologist Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but lied about the growth’s seriousness, minimizing its importance.

Freud later saw Felix Deutsch who saw that the growth was cancerous.

He identified it to Freud using the euphemism “a bad leukoplakia” instead of the technical diagnosis epithelioma.

Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised.

Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a rhinologist (nose surgeon) whose competence he had previously questioned.

Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic’s outpatient department.

Freud bled during and after the operation and may narrowly have escaped death.

Freud subsequently saw Deutsch again.

Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required, but did not tell Freud that he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might wish to commit suicide.

Freud had been given just five years to live.

He lasted sixteen, but he was a semi-invalid when he arrived in London and rarely left the house except to visit his pet dog Chun who was held in quarantine for nearly a year.

Freud was over eighty at this time.

By mid-September 1939, Freud’s cancer of the jaw was causing him increasingly severe pain and had been declared to be inoperable.

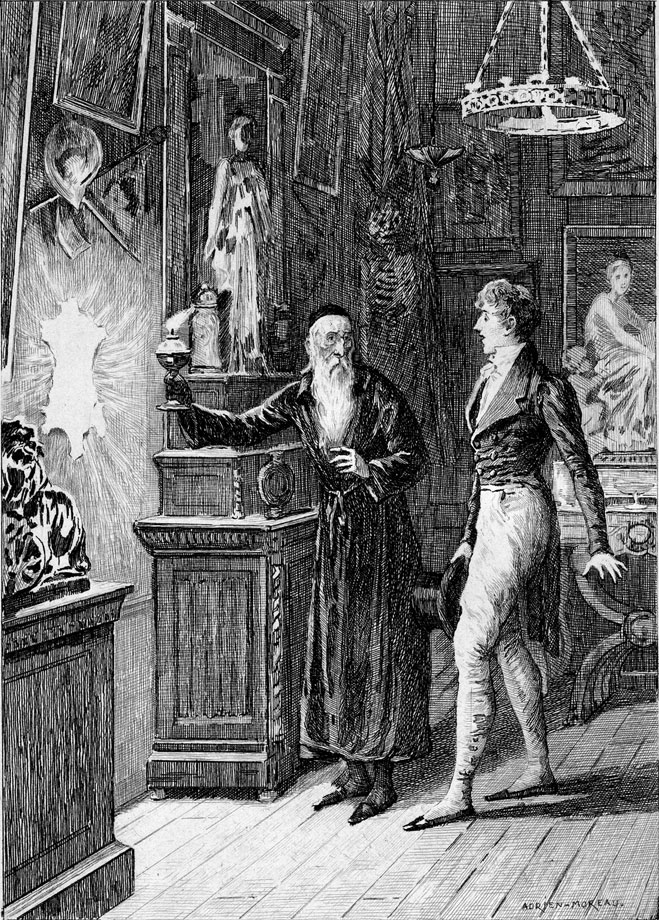

The last book he read, Balzac’s La Peau de Chagrin, prompted reflections on his own increasing frailty.

Above: Title page of Honoré Balzac’s La Peau de Chagrin (Skin of Sorrow)

A few days later he turned to his doctor, friend and fellow refugee, Max Schur, reminding him that they had previously discussed the terminal stages of his illness:

“Schur, you remember our ‘contract’ not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense.”

When Schur replied that he had not forgotten, Freud said, “I thank you.” and then “Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it’s right, then make an end of it.”

Anna Freud wanted to postpone her father’s death, but Schur convinced her it was pointless to keep him alive and on 21 and 22 September administered doses of morphine that resulted in Freud’s death around 3 am on 23 September 1939, age 83.

However, discrepancies in the various accounts Schur gave of his role in Freud’s final hours, which have in turn led to inconsistencies between Freud’s main biographers, has led to further research and a revised account.

This proposes that Schur was absent from Freud’s deathbed when a third and final dose of morphine was administered by Dr Josephine Stross, a colleague of Anna Freud’s, leading to Freud’s death around midnight on 23 September 1939.

Above: Freud’s ashes, Golders Green Crematorium

The house remained in his family until his youngest daughter Anna Freud, who was a pioneer of child therapy, died in 1982.

The house has a well maintained garden which is still much as Freud would have known it.

The Freuds moved all their furniture and household effects to London.

There are Biedermeier chests, tables and cupboards and a collection of 18th century and 19th century Austrian painted country furniture.

The museum owns Freud’s collection of Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Oriental antiquities, and his personal library.

Although Freud was not a practising Jew, he was very conscious of his Jewishness, which is reflected in the artifacts he collected, including an etching hanging in his study by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669) of Menasseh ben Israel (1604 – 1657), who persuaded Oliver Cromwell to allow Jews back into England in 1656.

Above: Rembrandt’s Portrait of Menasseh ben Israel

Freud’s “old and grubby gods” as he described his collection in a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess in 1899 are still on view to visitors, just as he left them.

Freud was an avid and knowledgable collector and often sought expert advice before purchasing.

As his collection grew, his study became a treasure trove of thousands of antiquities from all over the world, ranging from Roman glass objects to wooden Buddha statuettes, terracotta representations of the Greek god Eros, Egyptian gods cast in bronze, Chinese works in jade and a 20th century metal porcupine given to him during a visit to the United States in 1909.

Freud confessed that his passion for collecting was second only to his addiction to cigars.

The star exhibit in the museum is Freud’s psychoanalytic couch, which had been given to him by one of his patients, Madame Benvenisti, in 1890.

This was restored at a cost of £5000 in 2013.

This couch was where patients revealed their wildest dreams, forgotten trauma and hidden phobias or free associated whatever sprung into their minds before Freud would interpret their unconscious meanings.

In 2013, the Freud Museum’s curators worried about the deteriorating condition of the 125-year-old couch, which had begun to sag badly in the middle and was splitting along its seams.

Thanks to generous private donations and painstaking work by specialists, the couch was restored to its original splendour.

Covered with Oriental rugs and cushions it looks remarkably comfortable to recline upon and recall deep-seated memories.

The couch has seen a lot of Freud’s patients both in Vienna and London.

Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories.

Some patients known by pseudonyms were:

- Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben)

- Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945)

- Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser)

- Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss)

- Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich)

- Fräulein Lucy R.

- Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973)

- Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer, 1878–1914)

- Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild, 1878–1920)

- Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff, 1887–1979).

Other famous patients included:

- Prince Pedro Augusto of Brazil (1866–1934)

- H.D. (1886–1961)

- Emma Eckstein (1865–1924)

- Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation

- Princess Marie Bonaparte

- Edith Banfield Jackson (1895–1977)

- Albert Hirst (1887–1974).

The Wolf Man wrote of Freud’s home that….

“There was always a feeling of sacred peace and quiet here.

The rooms themselves must have been a surprise to any patient, for they in no way reminded one of a doctor’s office but rather of an archaeologist’s study.”

Above: The Wolf Man

To the Wolf Man Freud said:

“The psychoanalyst, like the archaeologist in his excavations, must uncover layer after layer of the patients’ psyche.”

In 2015 (the 50th anniversary of the Museum), the Museum, along with the artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, hired a police forensic team to scrutinize traces of DNA left on the couch.

The team found many examples, including strands of hair and a multitude of a multitude of dust particles, from Sigmund Freud, his patients and his family.

Freud did not sit on the couch himself when analyzing his patients, but sat out of sight next to it.

He once famously remarked to his friend, the psychoanalyist Hanns Sachs:

“I can’t let myself be stared at for eight hours daily.”

The study and library were preserved by Anna Freud after her father’s death.

The bookshelf behind Freud’s desk contains some of his favourite authors: not only Goethe and Shakespeare but also Heine, Multatuli and Anatole France.

Freud acknowledged that poets and philosophers had gained insights into the unconscious which psychoanalysis sought to explain systematically.

In addition to the books, the library contains various pictures hung as Freud arranged them; these include ‘Oedipus and the Riddle of the Sphinx‘ and ‘The Lesson of Dr Charcot‘ plus photographs of Martha Freud, Lou Andreas-Salomé, Yvette Guilbert, Marie Bonaparte and Ernst von Fleischl.

The collection includes a portrait of Freud by Salvador Dalí.

The museum organizes research and publication programmes and it has an education service which organises seminars, conferences and educational visits to the museum.

The museum is a member of the London Museums of Health & Medicine.

I quickly wandered through the Museum, upstairs and down, while Ute took the audio-guided tour.

I confess that I did not fully comprehend the importance of Sigmund Freud to the same extent as she did, for in our partnership she is both the brains and the beauty while I am simply loud and can lift heavy objects.

I still couldn’t explain the therapeutic techniques of free association and transference if my very life depended upon it.

And in this overly politically correct climate we now find ourselves living in these days I find myself quite discomfited by the notions of sexuality in infantile forms.

I have yet to be convinced of the soundness of his Oedipus complex theory that suggests that the ancient Greek legend of a king who kills his father and marries his mother is reflective of a child’s incest fantasy of falling in love with Mother and being jealous of Father.

Nor am I decided whether Freud’s idea that dreams are unconscious wish fulfillments as he suggests.

And I claim almost embarrassingly little understanding of that what he called the id, ego and superego, and very scant notions of what he terms the libido and the death drive.

But I will say that the Museum succeeded in capturing my curiosity about this man whose name, though a household one, remains almost as misunderstood as the unconscious mind.

Freud was born in Freiburg, Moravia (today’s Pribor, Czech Republic), the first of his mother’s eight children.

Above: Freud’s birthplace, Pribor, Czech Republic

His father, Jakob Freud (1815 – 1896) was a fairly successful wool merchant, who, at age 40, with two grown sons, Emanuel (1833 – 1914) and Philipp (1836 – 1911) and already a grandfather, married, for his second time, Sigmund’s mother Amalie Nathanson (1835 – 1930).

“Sigi” was the first – and favourite – of Amalie’s offspring, and Sigi knew it.

“A man who has been the indisputable favourite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror, that confidence of success, that often induces real success.”

Above: Sigi (age 16) and his mother Amalia, 1872

In 1859, the Freud family left Freiburg.

Freud’s half brothers emigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the “inseparable” playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel’s son, John.

Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud’s sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born: Rosa (b. 1860), Marie (b. 1861), Adolfine (b. 1862), Paula (b. 1864), Alexander (b. 1866).

Freud’s choice of boyhood heroes revealed a deep dislike of Imperial Austria: the anti-monarchist Oliver Cromwell and the Carthaginian general Hannibal.

Austria was Roman Catholic and anti-Semetic.

In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school.

He proved to be an outstanding pupil and graduated in 1873 with honors.

He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.

Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17 in 1873.

He had planned to study law, but joined the medical faculty at the university, where his studies included philosophy, physiology and zoology.

Freud’s special interests were histology (the scientific study of organic tissues) and neurophysiology (the scientific study of the nervous system).

He wanted to be a scientist – not a medical practicioner.

In 1876, Freud spent four weeks at a zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an inconclusive search for their male reproductive organs.

In 1877 Freud moved to Ernst Brücke’s physiology laboratory where he spent six years comparing the brains of humans and other vertebrates with those of invertebrates such as frogs, crayfish and lampreys.

His research work on the biology of nervous tissue proved seminal for the subsequent discovery of the neuron in the 1890s.

Freud’s research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year’s compulsory military service.

The lengthy downtimes enabled him to complete a commission to translate four essays from John Stuart Mill’s collected works.

He graduated with an MD in March 1881.

Freud was happy doing scientific work but Brücke gave him some fatherly advice.

Academic posts were few and badly paid and Freud’s chances of advancement as a Jew were bad, so with Freud’s father unable to support him – what with the Crash of 1873 ruining him and with six other children to support – and marriage plans with Martha Bernays (1861 – 1951), Freud began his medical career at the Vienna General Hospital.

Freud had to face another long training period in clinical medicine before starting his own private practice.

First he served (1882 – 1885) as assistant to Hermann Nothnagel (1841 – 1905), Professor of Internal Medicine, and spent five months (1183) working in the Psychiatric Clinic under Theodor Meynart (1833 – 1892), the greatest brain anatomist and neuropathologist at that time.

Meynart influenced Freud to become a specialist in neuropathology (diseases of the nervous system).

Freud’s research work in cerebral anatomy led to his studying the effects of cocaine – starting on himself.

He even prescribed it to Martha!

He felt that cocaine was nothing more than an anti-depressant, a harmless anaesthetic.

Freud’s close friend, the gifted physiologist Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow (1846 – 1891), suffered from a painful tumour of the hand and thus became a morphine addict.

Freud suggested that Ernst switch to cocaine instead.

Freud’s colleague Carl Koller put in his claim as the discoverer of cocaine, nearly ruining his reputation, because by 1886 cases of cocaine addiction were reported everywhere and Ernst had become a despairing addict.

Freud’s research would lead to the publication of an influential paper on the pallative effects of cocaine in 1884, but Ernst’s addiction would always make Freud regret that he had failed to anticipate cocaine’s addictive effects.

Above: Ernst von Fleschl-Marxow

His work on aphasia (the inability to comprehend or formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions as a result of a stroke or a head trauma) would form the basis of his first book On the Aphasias: a Critical Study, published in 1891.

Over a three-year period, Freud worked in various departments of the hospital.

His time spent in Theodor Meynert’s psychiatric clinic and as a locum (temporary replacement physician) in a local asylum led to an increased interest in clinical work.

His substantial body of published research led to his appointment as a university lecturer in neuropathology in 1885, a non-salaried post but one which entitled him to give lectures at the University of Vienna.

In 1886, Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in “nervous disorders“.

The same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg.

They had six children: Mathilde (b. 1887), Jean-Martin (b. 1889), Oliver (b. 1891), Ernst (b. 1892), Sophie (b. 1893), and Anna (b. 1895).

From 1891 until they left Vienna in 1938, Freud and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19, near Innere Stadt, a historical district of Vienna.

In 1896, Minna Bernays, Martha Freud’s sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé.

The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumours, started by Carl Jung, of an affair.

The discovery of a Swiss hotel log of 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst travelling with his sister-in-law, has been presented as evidence of the affair.

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24.

Initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker.

He believed that smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it.

Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually suffering a buccal (of the mouth) cancer.

Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, “the one great habit.”

Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection.

Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874).

Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept.

Freud owned and made use of Charles Darwin’s major evolutionary writings, and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann’s The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869).

Other texts of importance to Freud were by Gustav Fechner and Johann Friedrich Herbart with the latter’s Psychology as Science arguably considered to be of underrated significance in this respect.

Freud also drew on the work of Theodor Lipps who was one of the main contemporary theorists of the concepts of the unconscious and empathy.

Though Freud was reluctant to associate his psychoanalytic insights with prior philosophical theories, attention has been drawn to analogies between his work and that of both Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, both of whom he claimed not to have read until late in life.

One historian concluded, based on Freud’s correspondence with his adolescent friend Eduard Silberstein, that Freud read Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and the first two of the Untimely Meditations when he was seventeen.

In 1900, the year of Nietzsche’s death, Freud bought his collected works.

He told his friend, Fliess, that he hoped to find in Nietzsche’s works “the words for much that remains mute in me.”

Later, he said he had not yet opened them.

Freud came to treat Nietzsche’s writings “as texts to be resisted far more than to be studied.”

Above: Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

His interest in philosophy declined after he had decided on a career in neurology.

Freud read William Shakespeare in English throughout his life and it has been suggested that his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare’s plays.

Freud’s Jewish origins and his allegiance to his secular Jewish identity were of significant influence in the formation of his intellectual and moral outlook, especially with respect to his intellectual non-conformism, as he was the first to point out in his Autobiographical Study.

They would also have a substantial effect on the content of psychoanalytic ideas, particularly in respect of their common concerns with depth interpretation and “the bounding of desire by law”.

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was conducting scientific research into hypnosis.

He was later to recall the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.

Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience.

Once he had set up in private practice in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work.

He adopted the approach of his friend and collaborator, Josef Breuer, in a use of hypnosis which was different from the French methods he had studied in that it did not use suggestion.

The treatment of one particular patient of Breuer’s proved to be transformative for Freud’s clinical practice.

Described as Anna O., she was invited to talk about her symptoms while under hypnosis (she would coin the phrase “talking cure” for her treatment).

In the course of talking in this way these symptoms became reduced in severity as she retrieved memories of traumatic incidents associated with their onset.

Above: Bertha Pappenheim (aka Anna O.)(1859 – 1936)

The uneven results of Freud’s early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having reached the conclusion that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition, about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them.

In conjunction with this procedure, which he called “free association“, Freud found that patients’ dreams could be fruitfully analyzed to reveal the complex structuring of unconscious material and to demonstrate the psychic action of repression which, he had concluded, underlay symptom formation.

By 1896 he was using the term “psychoanalysis” to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.

Freud’s development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a “neurasthenia” which he linked to the death of his father in 1896 and which prompted a “self-analysis” of his own dreams and memories of childhood.

His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother’s affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses.

On the basis of his early clinical work, Freud had postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud’s seduction theory.

In the light of his self-analysis, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and that in either case they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.

This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes an autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud’s subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus complex.

Freud described the evolution of his clinical method and set out his theory of the psychogenetic origins of hysteria, demonstrated in a number of case histories, in Studies on Hysteria published in 1895 (co-authored with Josef Breuer).

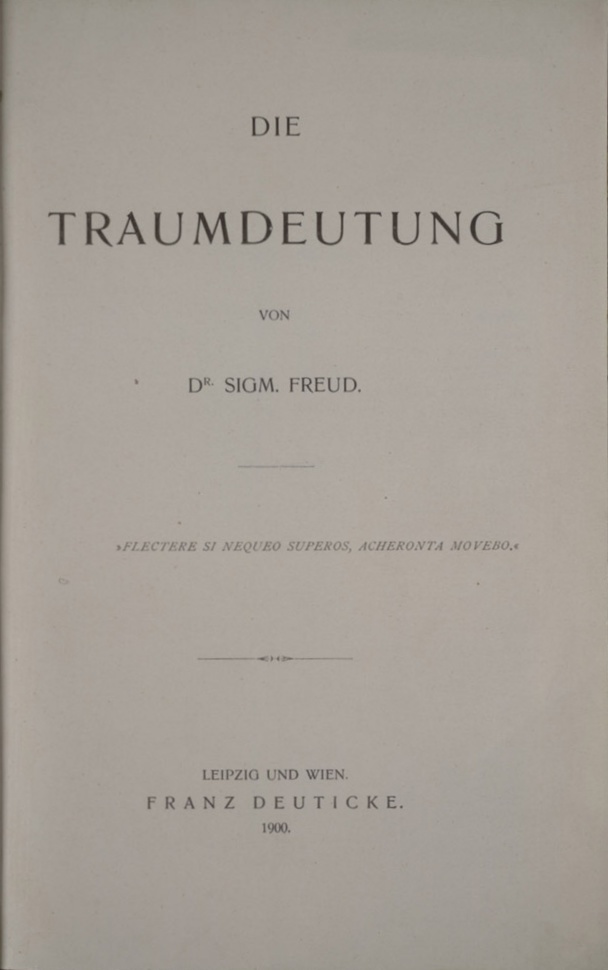

In 1899 he published The Interpretation of Dreams in which, following a critical review of existing theory, Freud gives detailed interpretations of his own and his patients’ dreams in terms of wish-fulfillments made subject to the repression and censorship of the “dream work“.

He then sets out the theoretical model of mental structure (the unconscious, pre-conscious and conscious) on which this account is based.

An abridged version, On Dreams, was published in 1901.

In works which would win him a more general readership, Freud applied his theories outside the clinical setting in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905).

In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its “polymorphous perverse” forms and the functioning of the “drives“, to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity.

The same year he published ‘Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (Dora)‘ which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.

During this formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin based ear, nose and throat specialist whom he had first met 1887.

Above: Freud (left) and Wilhelm Fliess (1858 – 1928)(right)

Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality.

Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudo-scientific.

He shared Freud’s views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality — masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms — in the etiology of what were then called the “actual neuroses“, primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.

They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess’s speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own ideas.

His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his Project for a Scientific Psychology was developed as a metapsychology with Fliess as interlocutor.

However, Freud’s efforts to build a bridge between neurology and psychology were eventually abandoned after they had reached an impasse, as his letters to Fliess reveal, though the soundest ideas of the Project were to be taken up again in the concluding chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams.

Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat “nasal reflex neurosis” and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him.

According to Freud her history of symptoms included severe leg pains with consequent restricted mobility, and stomach and menstrual pains.

These pains were, according to Fliess’s theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked, was curable by removal of part of the middle turbinate.

Fliess’s surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding – he had left a half-metre of gauze in Eckstein’s nasal cavity the subsequent removal of which left her permanently disfigured.

At first, though aware of Fliess’s culpability – Freud fled from the remedial surgery in horror – he could only bring himself to delicately intimate in his correspondence to Fliess the nature of his disastrous role and in subsequent letters maintained a tactful silence on the matter or else returned to the face-saving topic of Eckstein’s hysteria.

Freud ultimately, in light of Eckstein’s history of adolescent self-cutting and irregular nasal and menstrual bleeding, concluded that Fliess was “completely without blame“, as Eckstein’s post-operative hemorrhages were hysterical “wish-bleedings” linked to “an old wish to be loved in her illness” and triggered as a means of “rearousing [Freud’s] affection“.

Eckstein nonetheless continued her analysis with Freud.

She was restored to full mobility and went on to practice psychoanalysis herself.

Above: Emma Eckstein (1865 – 1924)

Freud, who had called Fliess “the Kepler of biology“, later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his “specifically Jewish mysticism” lay behind his loyalty to his Jewish friend and his consequent over-estimation of both his theoretical and clinical work.

Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud’s unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work.

After Fliess failed to respond to Freud’s offer of collaboration over publication of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1906, their relationship came to an end.

In 1902, Freud at last realised his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor.

The title “professor extraordinarius“was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of “professor ordinarius” in 1920).

Despite support from the university, his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was secured only with the intervention of one of his more influential ex-patients, a Baroness Marie Ferstel, who had to bribe the minister of education with a painting.

With his prestige thus enhanced, Freud continued with the regular series of lectures on his work which, since the mid-1880s as a lecturer of Vienna University, he had been delivering to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the university’s psychiatric clinic.

From the autumn of 1902, a number of Viennese physicians who had expressed interest in Freud’s work were invited to meet at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology.

This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft) and it marked the beginnings of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.

Freud founded this discussion group at the suggestion of the physician Wilhelm Stekel.

Stekel had studied medicine at the University of Vienna under Richard von Krafft-Ebing.

His conversion to psychoanalysis is variously attributed to his successful treatment by Freud for a sexual problem or as a result of his reading The Interpretation of Dreams, to which he subsequently gave a positive review in the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt.

Above: Wilhelm Steckel (1868 – 1940)

The other three original members whom Freud invited to attend, Alfred Adler, Max Kahane and Rudolf Reitler, were also physicians and all five were Jewish by birth.

Both Kahane and Reitler were childhood friends of Freud.

Kahane (1866 – 1923) had attended the same secondary school and both he and Reitler went to university with Freud.

They had kept abreast of Freud’s developing ideas through their attendance at his Saturday evening lectures.

In 1901, Kahane, who first introduced Stekel to Freud’s work, had opened an out-patient psychotherapy institute of which he was the director in Bauernmarkt, in Vienna.

In the same year, his medical textbook, Outline of Internal Medicine for Students and Practicing Physicians, was published.

In it, he provided an outline of Freud’s psychoanalytic method.

Kahane broke with Freud and left the Wednesday Psychological Society in 1907 for unknown reasons and in 1923 committed suicide.

Reitler (1865 – 1917) was the director of an establishment providing thermal cures in Dorotheergasse which had been founded in 1901.

He died prematurely in 1917.

Adler, regarded as the most formidable intellect among the early Freud circle, was a socialist who in 1898 had written a health manual for the tailoring trade.

He was particularly interested in the potential social impact of psychiatry.

Above: Alfred Adler (1870 – 1937)

Max Graf, a Viennese musicologist and father of “Little Hans” (Herbert Graf, 1903 – 1973), who had first encountered Freud in 1900 and joined the Wednesday group soon after its initial inception, described the ritual and atmosphere of the early meetings of the society:

The gatherings followed a definite ritual.

First one of the members would present a paper.

Then, black coffee and cakes were served; cigar and cigarettes were on the table and were consumed in great quantities.

After a social quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin.

The last and decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself.

There was the atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room.

Freud himself was its new prophet who made the heretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial.

Above: Max Graf (1873 – 1958)

By 1906, the group had grown to sixteen members, including Otto Rank, who was employed as the group’s paid secretary.

In the same year, Freud began a correspondence with Carl Gustav Jung who was by then already an academically acclaimed researcher into word-association and the Galvanic Skin Response, and a lecturer at Zurich University, although still only an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zürich.

Above: Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961)

In March 1907, Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, also a Swiss psychiatrist, travelled to Vienna to visit Freud and attend the discussion group.

Thereafter, they established a small psychoanalytic group in Zürich.

In 1908, reflecting its growing institutional status, the Wednesday group was renamed the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

After the founding of the IPA in 1910, an international network of psychoanalytical societies, training institutes and clinics became well established and a regular schedule of biannual Congresses commenced after the end of World War I to coordinate their activities.

In 1911, the first women members were admitted to the Society.

Tatiana Rosenthal (1885 – 1921) and Sabina Spielrein were both Russian psychiatrists and graduates of the Zürich University medical school.

Prior to the completion of her studies, Spielrein had been a patient of Jung at the Burghölzli and the clinical and personal details of their relationship became the subject of an extensive correspondence between Freud and Jung.

Both women would go on to make important contributions to the work of the Russian Psychoanalytic Society founded in 1910.

Above: Sabina Spielrain (1885- 1942)

Freud’s early followers met together formally for the first time at the Hotel Bristol, Salzburg on 27 April 1908.

This meeting, which was retrospectively deemed to be the first International Psychoanalytic Congress, was convened at the suggestion of Ernest Jones, then a London-based neurologist who had discovered Freud’s writings and begun applying psychoanalytic methods in his clinical work.

Jones had met Jung at a conference the previous year and they met up again in Zürich to organize the Congress.

There were, as Jones records, “forty-two present, half of whom were or became practicing analysts.”

In addition to Jones and the Viennese and Zürich contingents accompanying Freud and Jung, also present and notable for their subsequent importance in the psychoanalytic movement were Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon from Berlin, Sándor Ferenczi from Budapest and the New York-based Abraham Brill.

Important decisions were taken at the Congress with a view to advancing the impact of Freud’s work.

A journal, the Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologishe Forschungen, was launched in 1909 under the editorship of Jung.

This was followed in 1910 by the Monthly Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse edited by Adler and Stekel, in 1911 by Imago, a journal devoted to the application of psychoanalysis to the field of cultural and literary studies edited by Rank and in 1913 by the Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse, also edited by Rank.

Plans for an international association of psychoanalysts were put in place and these were implemented at the Nuremberg Congress of 1910 where Jung was elected, with Freud’s support, as its first president.

Freud turned to Brill and Jones to further his ambition to spread the psychoanalytic cause in the English-speaking world.

Both were invited to Vienna following the Salzburg Congress and a division of labour was agreed with Brill given the translation rights for Freud’s works, and Jones, who was to take up a post at the University of Toronto later in the year, tasked with establishing a platform for Freudian ideas in North American academic and medical life.

Jones’s advocacy prepared the way for Freud’s visit to the United States, accompanied by Jung and Ferenczi, in September 1909 at the invitation of Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, where he gave five lectures on psychoanalysis.

The event, at which Freud was awarded an Honorary Doctorate, marked the first public recognition of Freud’s work and attracted widespread media interest.

Freud’s audience included the distinguished neurologist and psychiatrist James Jackson Putnam, Professor of Diseases of the Nervous System at Harvard, who invited Freud to his country retreat where they held extensive discussions over a period of four days.

Putnam’s subsequent public endorsement of Freud’s work represented a significant breakthrough for the psychoanalytic cause in the United States.

When Putnam and Jones organised the founding of the American Psychoanalytic Association in May 1911 they were elected president and secretary respectively.

Brill founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society the same year.

His English translations of Freud’s work began to appear from 1909.

Some of Freud’s followers subsequently withdrew from the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) and founded their own schools.

From 1909, Adler’s views on topics such as neurosis began to differ markedly from those held by Freud.

As Adler’s position appeared increasingly incompatible with Freudianism, a series of confrontations between their respective viewpoints took place at the meetings of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in January and February 1911.

In February 1911, Adler, then the president of the society, resigned his position.

At this time, Stekel also resigned his position as vice president of the society.

Adler finally left the Freudian group altogether in June 1911 to found his own organization with nine other members who had also resigned from the group.

This new formation was initially called the Society for Free Psychoanalysis but it was soon renamed the Society for Individual Psychology.

In the period after World War I, Adler became increasingly associated with a psychological position he devised called individual psychology.

In 1912, Jung published Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious) making it clear that his views were taking a direction quite different from those of Freud.

To distinguish his system from psychoanalysis, Jung called it analytical psychology.

Anticipating the final breakdown of the relationship between Freud and Jung, Ernest Jones initiated the formation of a secret committee of loyalists charged with safeguarding the theoretical coherence and institutional legacy of the psychoanalytic movement.

Formed in the autumn of 1912, the Committee comprised Freud, Jones, Abraham, Ferenczi, Rank, and Hanns Sachs.

Max Eitingon joined the Committee in 1919.

Each member pledged himself not to make any public departure from the fundamental tenets of psychoanalytic theory before he had discussed his views with the others.

Above: The Committee (from left to right): Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sandor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones and Hanns Sachs

After this development, Jung recognised that his position was untenable and resigned as editor of the Jarhbuch and then as president of the IPA in April 1914.

The Zürich Society withdrew from the IPA the following July.

Later the same year, Freud published a paper entitled “The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement“, the German original being first published in the Jahrbuch, giving his view on the birth and evolution of the psychoanalytic movement and the withdrawal of Adler and Jung from it.

The final defection from Freud’s inner circle occurred following the publication in 1924 of Rank’s The Trauma of Birth which other members of the committee read as, in effect, abandoning the Oedipus Complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytic theory.

Abraham and Jones became increasingly forceful critics of Rank and though he and Freud were reluctant to end their close and long-standing relationship the break finally came in 1926 when Rank resigned from his official posts in the IPA and left Vienna for Paris.

His place on the committee was taken by Anna Freud.

Rank eventually settled in the United States where his revisions of Freudian theory were to influence a new generation of therapists uncomfortable with the orthodoxies of the IPA.

Psychoanalytic societies and institutes were established in Switzerland (1919), France (1926), Italy (1932), the Netherlands (1933), Norway (1933) and in Palestine (Jerusalem, 1933) by Eitingon, who had fled Berlin after Adolf Hitler came to power.

The New York Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1931.

The 1922 Berlin Congress was the last Freud attended.

By this time his speech had become seriously impaired by the prosthetic device he needed as a result of a series of operations on his cancerous jaw.

He kept abreast of developments through a regular correspondence with his principal followers and via the circular letters and meetings of the secret Committee which he continued to attend.

The Committee continued to function until 1927 by which time institutional developments within the IPA, such as the establishment of the International Training Commission, had addressed concerns about the transmission of psychoanalytic theory and practice.

There remained, however, significant differences over the issue of lay analysis – i.e. the acceptance of non-medically qualified candidates for psychoanalytic training.

Freud set out his case in favour in 1926 in his The Question of Lay Analysis.

He was resolutely opposed by the American societies who expressed concerns over professional standards and the risk of litigation (though child analysts were made exempt).

These concerns were also shared by some of his European colleagues.

Eventually an agreement was reached allowing societies autonomy in setting criteria for candidature.

In 1930 Freud was awarded the Goethe Prize in recognition of his contributions to psychology and to German literary culture.

Though in overall decline as a diagnostic and clinical practice, psychoanalysis remains influential within psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy, and across the humanities.

It thus continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate with regard to its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or is detrimental to the feminist cause.

Nonetheless, Freud’s work has suffused contemporary Western thought and popular culture.

In the words of W.H. Auden’s 1940 poetic tribute, by the time of Freud’s death, he had become “a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives.”

Somehow I got the feeling that the Freud Museum, try as it may, fails to truly capture the essence of what Sigi was trying to do.

Because the man was just too big.

At least in terms of the average tourist-layman, the simple man I am.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / The Rough Guide to London / Richard Appignanesi & Oscar Zarate, Introducing Freud / Joel Whitebook, Freud: An Intellectual Biography / Rebecca Wallersteiner, “If you’re sitting comfortably….a trip to the Sigmund Freud Museum!“, Spotlight, 23 October 2015 / Sophie Leighton, “Freud’s Collections“, Freud Museum London Friends News

.JPG?h=1080&w=1920&auto=format&fit=crop&q=40)

.JPG?h=1080&w=1920&auto=format&fit=crop&q=40)