Landschlacht, Switzerland, 21 January 2019

(Continued from Canada Slim and the Visionary & Canada Slim and the Current War)

“Imagine a man a century ago, bold enough to design and actually build a huge tower with which to transmit the human voice, music, pictures, press news and even power, through the Earth to any distance whatever without wires!

He probably would have been hung or burnt at the stake.”

(Hugo Gernsback, Preface to Nikola Tesla’s My Inventions: 5. The Magnifying Transmitter, Electrical Experimenter, June 1919)

Such was the high regard that Gernsback, Tesla’s greatest admirer, had for the Serbian inventor.

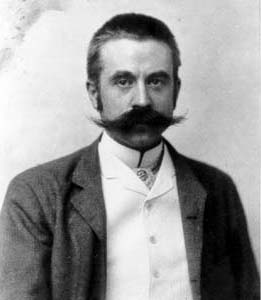

Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943) was one of the greatest scientists and innovators during the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The Serbian genius went to America in 1884 and would be followed by his Luxemburger admirer Hugo Gernsback (1884 – 1967) twenty years later.

Both men would come to America to bring realization to their visionary ideas.

Tesla is the creative genius behind many great inventions which are today utilized in radio, industrial and nuclear technology.

Gernsback’s contributions as a publisher were so significant that, along with the novelists H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, that he is sometimes called the Father of Science Fiction, and it is in his honour that the annual awards presented at the World Science Fiction Convention are named the Hugos.

For me there is an irony that Tesla was discovered by the world through Gernsback while I discovered Gernsback through the world of Tesla.

Belgrade, Serbia, 5 April 2018

A week’s vacation where boys will be boys in a part of the world far removed from our respective spouses found me visiting my Serbian friend Nesha in his home city of Belgrade.

Sadly, Nesha had more obligations in Serbia than just playing host to this Canadian blogger so half my stay involved me on my own.

I had arrived the previous day, travelling with Nesha from his home in Herisau, Switzerland, to his childhood house in the Serbian capital.

After breakfast the following morning, the dateline above, I set out to explore the city.

Krunska Street runs parallel to the Bulevar (King Aleksander Boulevard, one of the longest streets in Belgrade) and, in contrast, is a relatively quiet street and makes for a very pleasant stroll.

At Krunska 51, the Raska style villa of politician Dorde (George) Gencic, built in 1929, the Nikola Tesla Museum is engaged in educating and informing the public about the life and inventions of this Serbian scientist who died in Manhattan in 1943.

(Gernsback would die in the same city twenty-four years later.)

The Museum was founded when Sava Kosanovic, Tesla’s heir….

(Tesla never married.

He explained that his chastity was very helpful to his scientific abilities.

He once said in earlier years that he felt that he could never be worthy enough for a woman, considering women superior in every way.

His opinion started to sway in later years when he felt that women were trying to outdo men and make themselves more dominant.

(I know how he feels!)

This “new woman” was met with much indignation from Tesla, who felt that women were losing their feminity by trying to be in power.

In an interview with The Galveston Daily News on 10 August 1924, he stated:

“In place of the soft voiced, gentle woman of my reverant worship, has come the woman who thinks that her chief success in life lies in making herself as much as possible like man – in dress, voice and actions, in sports and achievements of every kind.

The tendency of women to push aside man, supplanting the old spirit of cooperation with him in all the affairs of life, is very disappointing to me.”

(Clearly his confusion has carried on into the modern age where the ongoing internal struggle between a woman defining herself and letting herself be defined by others still remains.)

Although he told a reporter in later years that he sometimes felt that by not marrying, he had made too great a sacrifice to his work, Tesla chose to never pursue or engage in any known relationships, instead finding all the stimulation he needed in his work.)

(Unlike Tesla, Gernsback would marry three times.)

Kosanovic brought Tesla’s effects and legacy to Belgrade.

These mainly consist of sketches of his unrealized works, his scientific journal, personal notes and also an urn containing his ashes.

Also at the Museum are thematic rooms, categorized according to different periods of his life.

The most interesting area is certainly that containing models which explain the functioning principles behind his inventions.

Above: Tesla two-phase induction motor

Though quite small the Museum has several interesting items on display and an interactive exposition that will capture your attention.

It holds more than 160,000 original documents, over 2,000 books and journals, over 1,200 historical technical exhibits, over 1,500 photographs and photo plates of original, technical objects, instruments and apparatus, and over 1,000 plans and drawings.

Above: Nikola Tesla’s baptismal certificate (24 July 1856)

The Museum is also of interest to researchers since it keeps almost all belongings left by the eccentric scientist.

Due to the importance that Tesla’s writings still have for science, the archive of the Museum has been added to the UNESCO Memory of the World list.

The Museum is divided into two parts.

The historical part is where one can see many of Tesla’s personal belongings, exhibits illustrating his life, awards and decorations bestowed.

The second presents the path of Tesla’s discoveries with models of his inventions in fields of electricity and engineering.

Guided tours in English and Serbian with fascinating demonstrations on how Tesla’s inventions work take place every hour on the hour.

Though Tesla never had great financial success, he nonetheless registered over 700 patents worldwide – examples of his best known discoveries being rotating magnetic fields, wireless communication (the foundation of remote control and radio) and rotary transformers.

During his life Tesla was recognized as a striking but sometimes eccentric genius.

Today he is praised for his great achievements:

In 1895 he designed the first hydroelectric power plant at the Niagara Falls.

Above: Schoellkopf Stations 3, 3B and 3C, Niagara Falls

His alternating current (AC) induction motor is considered one of the greatest discoveries of all time.

Tesla’s name has been honoured with the International Unit of Magnetic Flux Density, the Tesla (T).

Nevertheless I cannot help but wonder whether Tesla’s genius would be as well-known to the average man had it not been for Gernsback or whether he would have gone down in history as simply a clever eccentric without the additional fame Gernsback provided him.

And, to be fair, I wonder whether Gernsback would have found the inspiration for founding “scientifiction” had it not been for the scientific wonders that Tesla invented.

To bring these two men together I need to continue with Tesla’s story first.

From the 1890s through 1906, Tesla spent a great deal of time and fortune on a series of projects trying to develop the transmission of electrical power without wires.

It was an expansion of his idea of using coils to transmit power that he had been demonstrating in wireless lighting.

He saw this as not only a way to transmit large amounts of power around the world but also, as he had pointed out in his earlier lectures, a way to transmit worldwide communications.

At the time Tesla was formulating his ideas, there was no feasible way to wirelessly transmit communication signals over long distances, let alone large amounts of power.

By the mid 1890s, Tesla was working on the idea that he might be able to conduct electricity long distance through the Earth or the atmosphere, and began working on experiments to test this idea including setting up a large resonance transformer magnifying transmitter in his East Houston Street lab.

Above: Tesla’s East Houston Street lab, New York City

Seeming to borrow from a common idea at the time that the Earth’s atmosphere was conductive, he proposed a system composed of balloons suspending, transmitting, and receiving, electrodes in the air above 30,000 feet (9,100 m) in altitude, where he thought the lower pressure would allow him to send high voltages (millions of volts) long distances.

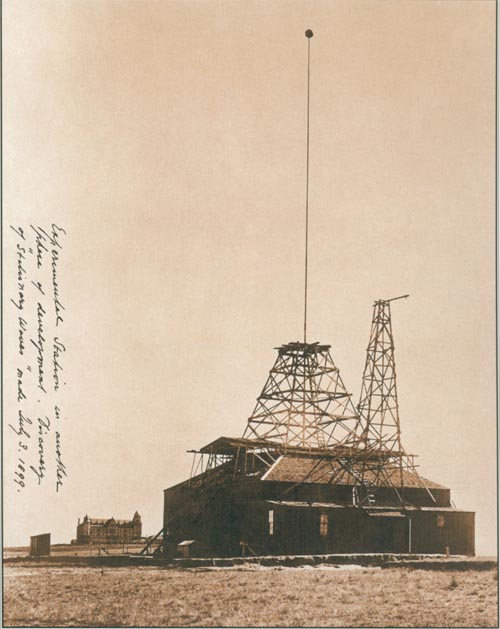

To further study the conductive nature of low pressure air, Tesla set up an experimental station at high altitude in Colorado Springs during 1899.

The Experimental Station was located on empty land on the highest local point (Knob Hill) between the 1876 Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind and the Union Printers Home, where Tesla conducted the research described in the Colorado Springs Notes, 1899-1900.

A few papers of the times listed Tesla’s lab as about 200 feet east of the Deaf and Blind School and 200 feet north of Pikes Peak Ave.

This put it on top of the hill at E. Kiowa St. and N. Foote Ave (facing west); as documented by Pikes Peak Library District.

There he could safely operate much larger coils than in the cramped confines of his New York lab, and an associate had made an arrangement for the El Paso Power Company to supply alternating current free of charge.

Tesla was focused in his research for the practical development of a system for wireless transmission of power and a utilization system.

Tesla said, in “On electricity“, Electrical Review (27 January 1897):

- “In fact, progress in this field has given me fresh hope that I shall see the fulfillment of one of my fondest dreams; namely, the transmission of power from station to station without the employment of any connecting wires.“

Tesla went to Colorado Springs in mid-May 1899 with the intent to research:

- Transmitters of great power.

- Individualization and isolating the energy transmission means.

- Laws of propagation of currents through the earth and the atmosphere.

Tesla spent more than half his time researching transmitters.

Tesla spent less than a quarter of his time researching delicate receivers and about a tenth of his time measuring the capacity of the vertical antenna.

Also, Tesla spent a tenth of his time researching miscellaneous subjects.

J. R. Wait’s commented on Tesla activity:

- “From an historical standpoint, it is significant that the genius Nikola Tesla envisaged a world wide communication system using a huge spark gap transmitter located in Colorado Springs in 1899.

- A few years later he built a large facility in Long Island that he hoped would transmit signals to the Cornish coast of England.

- In addition, he proposed to use a modified version of the system to distribute power to all points of the globe”.

To fund his experiments he convinced John Jacob Astor IV to invest $100,000 to become a majority share holder in the Nikola Tesla Company.

Above: John Jacob Astor IV (1864 – 1912)(died on the Titanic)

Astor thought he was primarily investing in the new wireless lighting system.

Instead, Tesla used the money to fund his Colorado Springs experiments.

Upon his arrival, he told reporters that he planned to conduct wireless telegraphy experiments, transmitting signals from Pikes Peak to Paris.

Above: Pike’s Peak, 12 miles / 19 km west of Colorado Springs

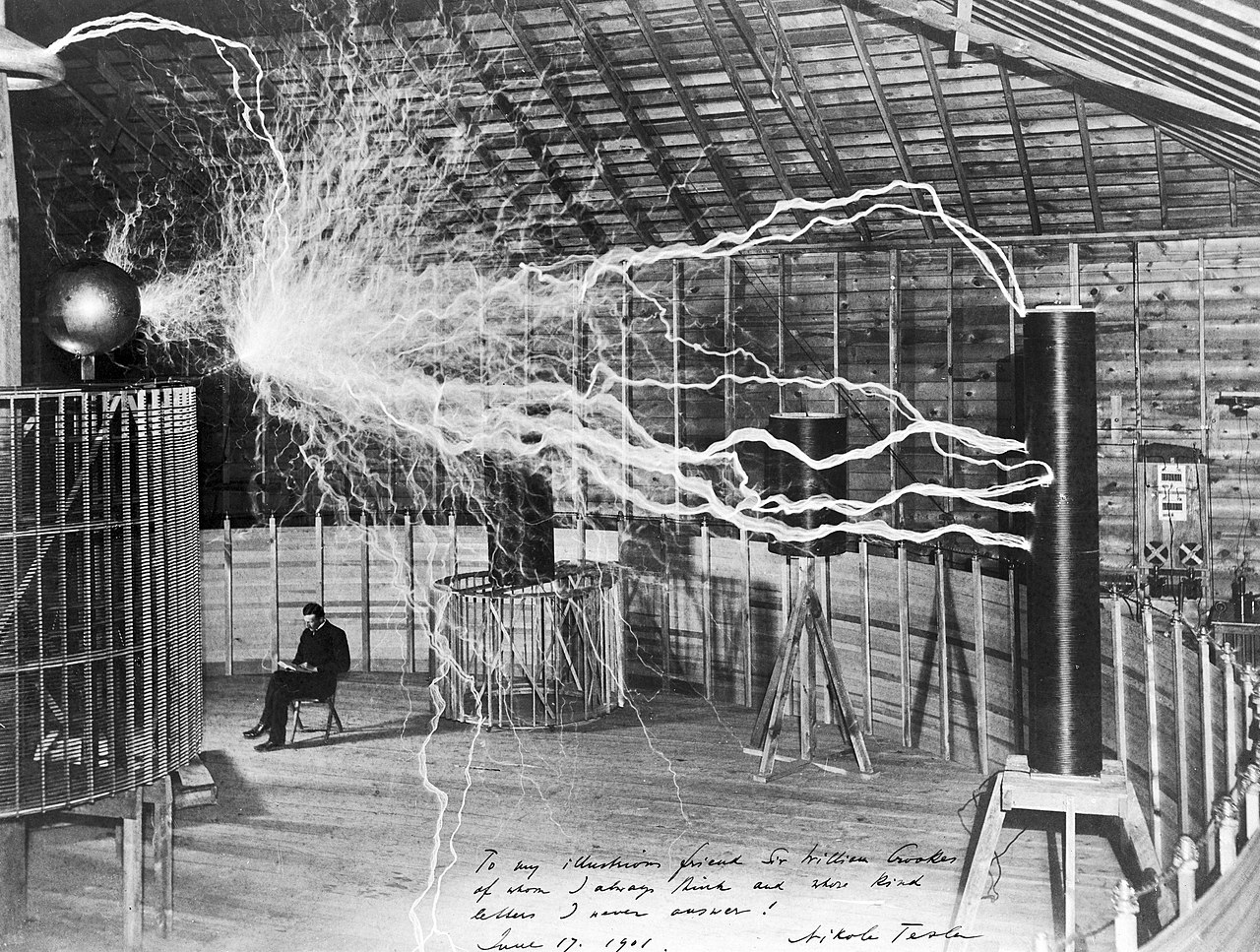

The lab possessed the largest Tesla coil ever built, 49.25 feet (15 m) in diameter, which was a preliminary version of the magnifying transmitter planned for installation in the Wardenclyffe Tower.

He produced artificial lightning, with discharges consisting of millions of volts and up to 135 feet (41 m) long.

Thunder from the released energy was heard 15 miles (24 km) away in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

People walking along the street observed sparks jumping between their feet and the ground.

Sparks sprang from water line taps when touched.

Light bulbs within 100 feet (30 m) of the lab glowed even when turned off.

Horses in a livery stable bolted from their stalls after receiving shocks through their metal shoes.

Butterflies were electrified, swirling in circles with blue halos of St. Elmo’s fire around their wings.

While experimenting, Tesla inadvertently faulted a power station generator, causing a power outage.

In August 1917, Tesla explained what had happened in The Electrical Experimenter:

“As an example of what has been done with several hundred kilowatts of high frequency energy liberated, it was found that the dynamos in a power house 6 miles (10 km) away were repeatedly burned out, due to the powerful high frequency currents set up in them, and which caused heavy sparks to jump through the windings and destroy the insulation!“

There he conducted experiments with a large coil operating in the megavolts range, producing artificial lightning (and thunder) consisting of millions of volts and up to 135 feet (41 m) long discharges and, at one point, inadvertently burned out the generator in El Paso, causing a power outage.

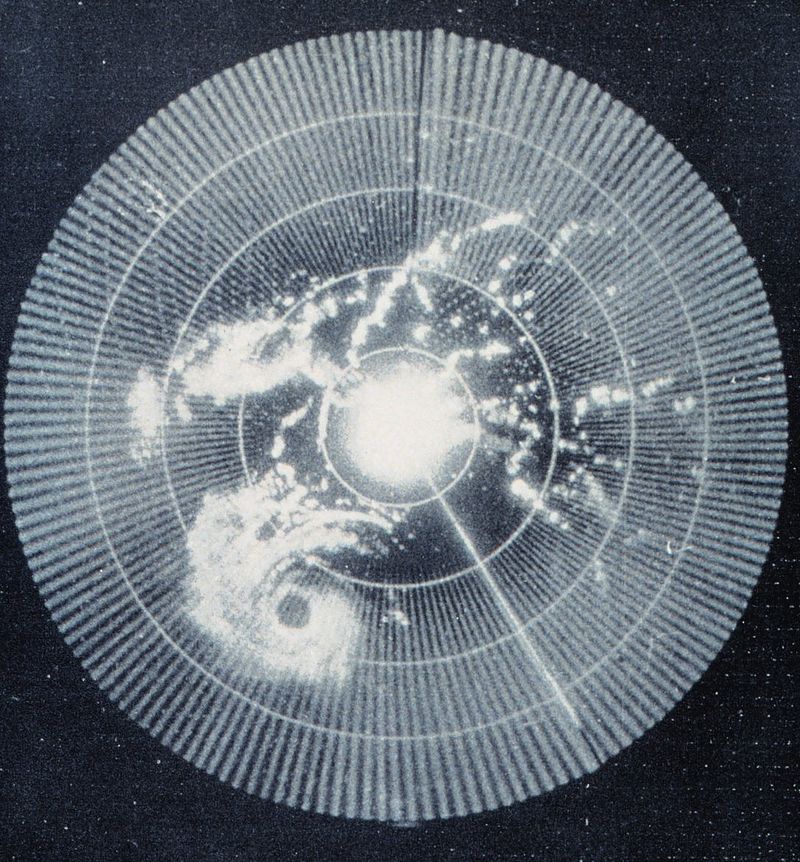

The observations he made of the electronic noise of lightning strikes, led him to (incorrectly) conclude that he could use the entire globe of the Earth to conduct electrical energy.

During his time at his laboratory, Tesla observed unusual signals from his receiver which he speculated to be communications from another planet.

He mentioned them in a letter to a reporter in December 1899 and to the Red Cross Society in December 1900.

Reporters treated it as a sensational story and jumped to the conclusion Tesla was hearing signals from Mars.

Above: Mars

He expanded on the signals he heard in a 9 February 1901 Collier’s Weekly article “Talking With Planets” where he said it had not been immediately apparent to him that he was hearing “intelligently controlled signals” and that the signals could come from Mars, Venus, or other planets.

It has been hypothesized that he may have intercepted Guglielmo Marconi’s European experiments in July 1899—Marconi may have transmitted the letter S (dot/dot/dot) in a naval demonstration, the same three impulses that Tesla hinted at hearing in Colorado—or signals from another experimenter in wireless transmission.

Above: Guglielmo Marconi (1874 – 1937)

Tesla had an agreement with the editor of The Century Magazine to produce an article on his findings.

The magazine sent a photographer to Colorado to photograph the work being done there.

The article, titled “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy“, appeared in the June 1900 edition of the magazine.

He explained the superiority of the wireless system he envisioned but the article was more of a lengthy philosophical treatise than an understandable scientific description of his work, illustrated with what were to become iconic images of Tesla and his Colorado Springs experiments.

Tesla made the rounds in New York trying to find investors for what he thought would be a viable system of wireless transmission, wining and dining them at the Waldorf-Astoria’s Palm Garden (the hotel where he was living at the time), The Players Club and Delmonico’s.

On 7 January 1900 Tesla made his final entry in his journal while in Colorado Springs.

In 1900 Tesla was granted patents for a “system of transmitting electrical energy” and “an electrical transmitter.”

When Guglielmo Marconi made his famous first-ever transatlantic radio transmission in 1901, Tesla quipped that it was done with 17 Tesla patents, though there is little to support this claim.

Above: Marconi watching his associates raising the kite used to lift the antenna, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 12 December 1901

In 1904, Tesla was sued for unpaid debts in Colorado Springs.

His lab was torn down and its contents were sold two years later at auction at the court house to satisfy his debts.

In March 1901, Tesla obtained $150,000 ($4,517,400 in today’s dollars) from J. Pierpont Morgan in return for a 51% share of any generated wireless patents and began planning the Wardenclyffe Tower facility to be built in Shoreham, New York, 100 miles (161 km) east of the city on the North Shore of Long Island.

Tesla’s design for Wardenclyffe grew out of his experiments beginning in the early 1890s.

His primary goal in these experiments was to develop a new wireless power transmission system.

He discarded the idea of using the newly discovered Hertzian (radio) waves, detected in 1888 by German physicist Heinrich Rudolf Hertz since Tesla doubted they existed and basic physics told him, and most other scientists from that period, that they would only travel in straight lines the way visible light did, meaning they would travel straight out into space becoming “hopelessly lost“.

Above: Heinrich Hertz (1857 – 1894)

In laboratory work and later large scale experiments at Colorado Springs in 1899, Tesla developed his own ideas on how a worldwide wireless system would work.

He theorized from these experiments that if he injected electric current into the Earth at just the right frequency he could harness what he believed was the planet’s own electrical charge and cause it to resonate at a frequency that would be amplified in “standing waves” that could be tapped anywhere on the planet to run devices or, through modulation, carry a signal.

His system was based more on 19th century ideas of electrical conduction and telegraphy instead of the newer theories of air-borne electromagnetic waves, with an electrical charge being conducted through the ground and being returned through the air.

Tesla’s design used a concept of a charged conductive upper layer in the atmosphere, a theory dating back to an 1872 idea for a proposed wireless power system by Mahlon Loomis.

Above: Mahlon Loomis (1826 – 1886)

Tesla not only believed that he could use this layer as his return path in his electrical conduction system, but that the power flowing through it would make it glow, providing night time lighting for cities and shipping lanes.

In a February 1901 Collier’s Weekly article titled “Talking With Planets” Tesla described his “system of energy transmission and of telegraphy without the use of wires” as “using the Earth itself as the medium for conducting the currents, thus dispensing with wires and all other artificial conductors … a machine which, to explain its operation in plain language, resembled a pump in its action, drawing electricity from the Earth and driving it back into the same at an enormous rate, thus creating ripples or disturbances which, spreading through the Earth as through a wire, could be detected at great distances by carefully attuned receiving circuits.

In this manner I was able to transmit to a distance, not only feeble effects for the purposes of signaling, but considerable amounts of energy, and later discoveries I made convinced me that I shall ultimately succeed in conveying power without wires, for industrial purposes, with high economy, and to any distance, however great.”

Although Tesla demonstrated wireless power transmission at Colorado Springs, lighting electric lights mounted outside the building where he had his large experimental coil, he did not scientifically test his theories.

He believed he had achieved Earth resonance which, according to his theory, would work at any distance.

Tesla began working on his wireless station immediately.

As soon as the contract was signed with Morgan in March 1901 he placed an order for generators and transformers with the Westinghouse Electric Company.

Tesla’s plans changed radically after he read a June 1901 Electrical Review article by Marconi entitled SYNTONIC WIRELESS TELEGRAPH.

At this point Marconi was transmitting radio signals beyond the range most physicists thought possible (over the horizon) and the description of the Italian inventor’s use of a “Tesla coil” “connected to the Earth” led Tesla to believe Marconi was copying his earth resonance system to do it.

Tesla, believing a small pilot system capable of sending Morse code yacht race results to Morgan in Europe would not be able to capture the attention of potential investors, decided to scale up his designs with a much more powerful transmitter, incorporating his ideas of advanced telephone and Image transmission as well as his ideas of wireless power delivery.

Above: J.P. Morgan (1837 – 1913)

In July 1901 Tesla informed Morgan of his planned changes to the project and the need for much more money to build it.

He explained the more grandiose plan as a way to leap ahead of competitors and secure much larger profits on the investment.

With Tesla basically proposing a breach of contract, Morgan refused to lend additional funds and demanded an account of money already spent.

Tesla would claim a few years later that funds were also running short because of Morgan’s role in triggering the stock market panic of 1901, making everything Tesla had to buy much more expensive.

Despite Morgan stating no additional funds would be supplied, Tesla continued on with the project.

He explored the idea of building several small towers or a tower 300 feet and even 600 feet tall in order to transmit the type of low-frequency long waves that Tesla thought were needed to resonate the Earth.

His friend, architect Stanford White, who was working on designing structures for the project, calculated that a 600-foot tower would cost $450,000 and the idea had to be scrapped.

Above: Stanford White (1853 – 1906)

By July 1901, Tesla had expanded his plans to build a more powerful transmitter to leap ahead of Marconi’s radio based system, which Tesla thought was a copy of his own system.

He approached Morgan to ask for more money to build the larger system but Morgan refused to supply any further funds.

A month after Marconi’s success, Tesla tried to get Morgan to back an even larger plan to transmit messages and power by controlling “vibrations throughout the globe“.

Over the next five years, Tesla wrote more than 50 letters to Morgan, pleading for and demanding additional funding to complete the construction of Wardenclyffe.

Tesla continued the project for another nine months into 1902.

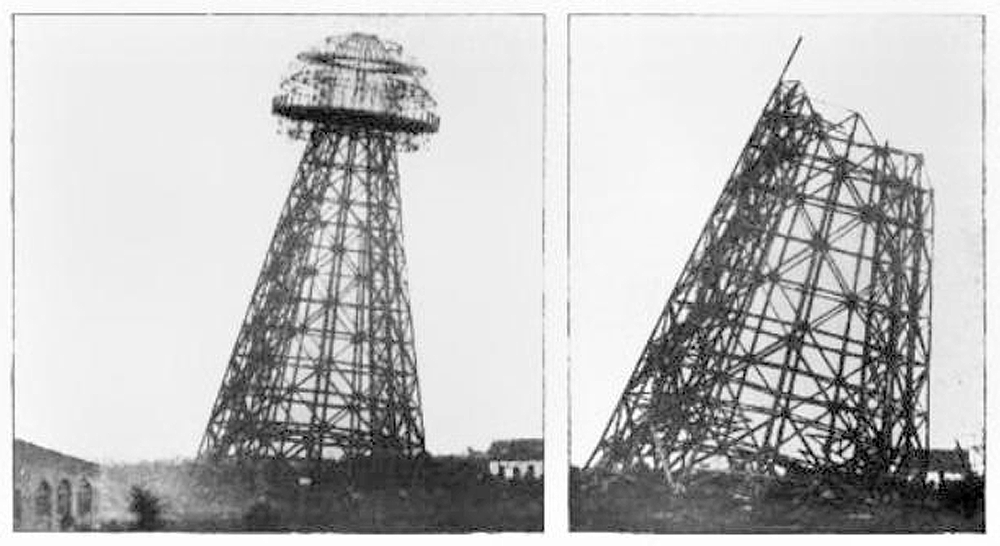

The tower was erected to its full 187 feet (57 m).

In June 1902, Tesla moved his lab operations from Houston Street to Wardenclyffe.

In 1906 the financial problems and other events may have led to a nervous breakdown on Tesla’s part.

The mentally unstable multimillionaire Harry Kendall Thaw shot and killed the prominent architect and New York socialite Stanford White in front of hundreds of witnesses at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden on the evening of 25 June 1906, leading to what the press would call the “Trial of the Century“.

During the trial, Nesbit testified that five years earlier, when she was a stage performer at the age of 15 or 16, she had attracted the attention of White, who first gained her and her mother’s trust, then sexually assaulted her while she was unconscious, and then had a subsequent romantic and sexual relationship with her that continued for some period of time

Above: Evelyn Nesbit (1884 – 1967)

In October, long time investor William Rankine died of a heart attack.

Things were so bad by the fall of that year George Scherff, Tesla’s chief manager who had been supervising Wardenclyffe, had to leave to find other employment.

The people living around Wardenclyffe noticed the Tesla plant seemed to have been abandoned without notice.

In 1904 Tesla took out a mortgage on the Wardenclyffe property with George C. Boldt, proprietor of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, to cover Tesla’s living expenses at the hotel.

Above: George Boldt (1851 – 1916)

In 1908 Tesla procured a second mortgage from Boldt to further cover expenses.

The facility was partially abandoned around 1911, and the tower structure deteriorated.

Between 1912 and 1915, Tesla’s finances unraveled, and when the funders wanted to know how they were going to recapture their investments, Tesla was unable to give satisfactory answers.

The 1 March 1916 edition of the publication Export American Industries ran a story titled “Tesla’s Million Dollar Folly” describing the abandoned Wardenclyffe site:

There everything seemed left as for a day — chairs, desks, and papers in businesslike array.

The great wheels seemed only awaiting Monday life.

But the magic word has not been spoken, and the spell still rests on the great plant.

Investors on Wall Street were putting their money into Marconi’s system, and some in the press began turning against Tesla’s project, claiming it was a hoax.

The project came to a halt in 1905.

Tesla mortgaged the Wardenclyffe property to cover his debts at the Waldorf-Astoria, which eventually mounted to $20,000 ($500,300 in today’s dollars).

He lost the property in foreclosure in 1915 and by mid-1917 the facility’s main building was breached and vandalized.

In 1917 the Tower was demolished by the new owner to make the land a more viable real estate asset.

Meanwhile….

Gernsback was an entrepreneur in the electronics industry, importing radio parts from Europe to the United States and helping to popularize amateur “wireless“.

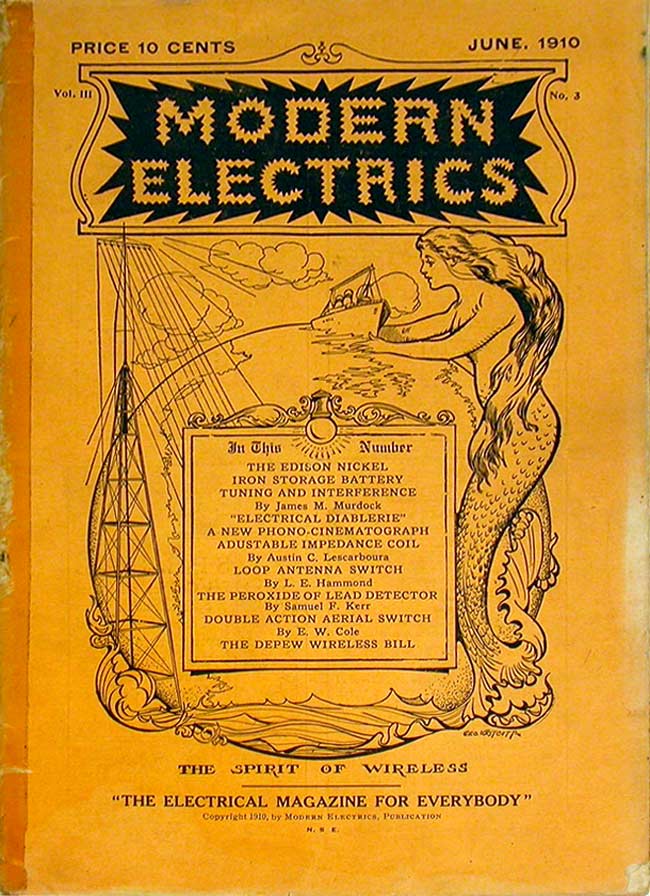

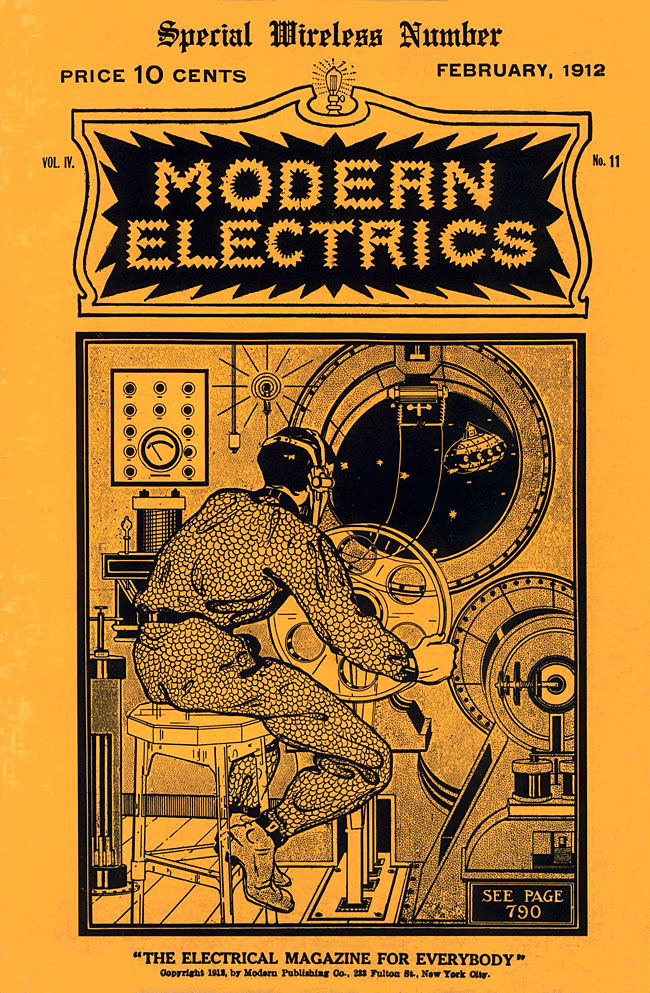

In April 1908, he founded Modern Electrics, the world’s first magazine about both electronics and radio (“wireless“).

While the cover of the magazine itself states it was a catalog, most historians note that it contained articles, features and plotlines, qualifying it as a magazine.

Under its auspices, in January 1909, Gernsback founded the Wireless Association of America, which had 10,000 members within a year.

In 1912, Gernsback said that he estimated 400,000 people in the US were involved in amateur radio.

In 1913, he founded a similiar magazine, The Electrical Experimenter, which became Science and Invention in 1920.

It was in these magazines he began including scientific fiction stories alongside science journalism – including his own novel Ralph 124c 41+ which he ran for 12 months in Modern Electrics.

By playing a key role in the wireless industry, Gernsback secured a position and a significant influence on the adoption of new legal regulations.

At the same time, aware of the low level of education of radio amateurs, he founded several magazines covering radio and later also television.

It is widely believed that the term television appeared for the first time in the December 1909 issue of his Modern Electrics, in the article “Television and the Telephot“.

Gernsback began publishing articles with a futuristic view of scientific and technological developments very early.

When finishing the preparation of an issue of his magazine Modern Electrics in 1911, Gernsback discovered that some free space remained on one of the pages.

Since he was already used to writing his predictions for the future of radio and other technologies, which were well received by the readers, he decided to go one step further.

He wrote a short adventure story, focusing on the application of technology in the year 2660.

It was a spur of the moment thing that he wrote late at night in his office and the text was long enough to fit into the available space into the magazine.

The readers wanted to learn what happened next.

And so the next installment came about – 12 of them in total until the story was completed.

Encouraged by its popularity, Gernsback continued to publish this specific type of texts, which he called scientifiction, later to be known as science fiction.

As the publisher of successful magazines, Gernsback managed to draw the attention of leading scientists, including Tesla, Marconi, Fessenden, Edison and many others….

Above: Hugo Gernsback demonstrating his television goggles in 1963 for Life magazine

After Wardenclyffe closed, Tesla continued to write to Morgan.

After “the great man” died, Tesla wrote to Morgan’s son Jack, trying to get further funding for the project.

In 1906, Tesla opened offices at 165 Broadway in Manhattan, trying to raise further funds by developing and marketing his patents.

Above: City Investing Building, 165 Broadway, Manhattan

On his 50th birthday, in 1906, Tesla demonstrated a 200 horsepower (150 kilowatts) 16,000 rpm bladeless turbine.

During 1910–1911 at the Waterside Power Station in New York, several of his bladeless turbine engines were tested at 100–5,000 hp.

Tesla worked with several companies including the period 1919–1922 working in Milwaukee for Allis-Chalmers.

He spent most of his time trying to perfect the Tesla turbine with Hans Dahlstrand, the head engineer at the company, but engineering difficulties meant it was never made into a practical device.

Tesla did license the idea to a precision instrument company and it found use in the form of luxury car speedometers and other instruments.

Tesla went on to have offices at the Metropolitan Life Tower from 1910 to 1914, rented for a few months at the Woolworth Building, moving out because he could not afford the rent, and then to office space at 8 West 40th Street from 1915 to 1925.

After moving to 8 West 40th Street, he was effectively bankrupt.

Above: Tesla working in his office, 8 W. 40th Street, New York City

Most of his patents had run out and he was having trouble with the new inventions he was trying to develop.

By 1915, Tesla’s accumulated debt at the Waldorf-Astoria was around $20 thousand ($495 thousand in 2018 dollars).

When Tesla was unable to make any further payments on the mortgages, Boldt foreclosed on the Wardenclyffe property.

Boldt failed to find any use for the property and finally decided to demolish the tower for scrap.

On 4 July 1917 the Smiley Steel Company of New York began demolition of the tower by dynamiting it.

The tower was knocked on a tilt by the initial explosion but it took till September to totally demolish it.

The scrap value realized was $1,750.

Since this was during World War I a rumor spread, picked up by newspapers and other publications, that the tower was demolished on orders of the United States government with claims German spies were using it as a radio transmitter or observation post, or that it was being used as a landmark for German submarines.

Tesla was not pleased with what he saw as attacks on his patriotism via the rumors about Wardenclyffe, but since the original mortgages with Boldt as well as the foreclosure had been kept off the public record in order to hide his financial difficulties, Tesla was not able to reveal the real reason for the demolition.

George Boldt decided to make the property available for sale.

When World War I broke out, the British cut the transatlantic telegraph cable linking the US to Germany in order to control the flow of information between the two countries.

They also tried to shut off German wireless communication to and from the US by having the US Marconi Company sue the German radio company Telefunken for patent infringement.

Telefunken brought in the physicists Jonathan Zenneck and Karl Ferdinand Braun for their defense and hired Tesla as a witness for two years for $1,000 a month.

The case stalled and then went moot when the US entered the war against Germany in 1917.

In 1915, Tesla attempted to sue the Marconi Company for infringement of his wireless tuning patents.

Marconi’s initial radio patent had been awarded in the US in 1897, but his 1900 patent submission covering improvements to radio transmission had been rejected several times, before it was finally approved in 1904, on the grounds that it infringed on other existing patents including two 1897 Tesla wireless power tuning patents.

Tesla’s 1915 case went nowhere, but in a related case, where the Marconi Company tried to sue the US government over WWI patent infringements, a Supreme Court of the United States 1943 decision restored the prior patents of Oliver Lodge, John Stone and Tesla.

The court declared that their decision had no bearing on Marconi’s claim as the first to achieve radio transmission, just that since Marconi’s claim to certain patented improvements were questionable, the company could not claim infringement on those same patents.

On 6 November 1915, a Reuters news agency report from London had the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla.

However, on 15 November, a Reuters story from Stockholm stated the prize that year was being awarded to Sir William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg “for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays.”

There were unsubstantiated rumors at the time that either Tesla or Edison had refused the prize.

The Nobel Foundation said:

“Any rumor that a person has not been given a Nobel Prize because he has made known his intention to refuse the reward is ridiculous“.

A recipient could decline a Nobel Prize only after he is announced a winner.

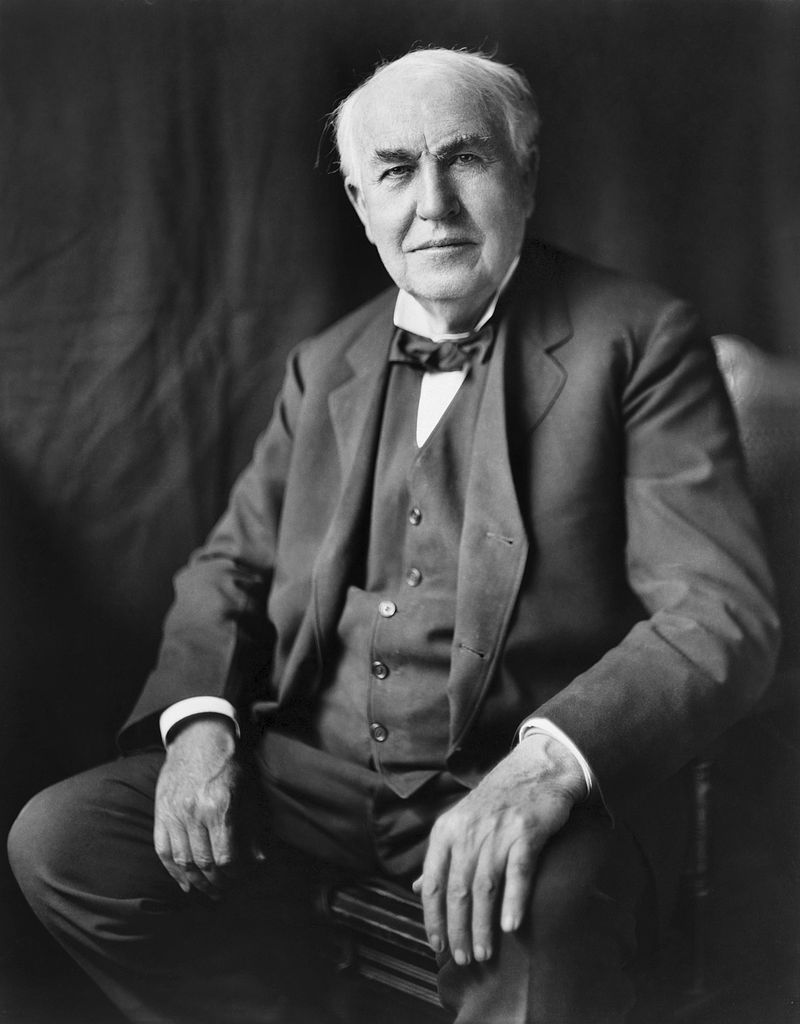

There have been subsequent claims by Tesla biographers that Edison and Tesla were the original recipients and that neither was given the award because of their animosity toward each other, that each sought to minimize the other’s achievements and right to win the Award, that both refused ever to accept the award if the other received it first, that both rejected any possibility of sharing it, and even that a wealthy Edison refused it to keep Tesla from getting the $20,000 prize money.

In the years after these rumors, neither Tesla nor Edison won the prize (although Edison did receive one of 38 possible bids in 1915 and Tesla did receive one of 38 possible bids in 1937).

On 20 April 1922, Tesla lost an appeal of judgment on Boldt’s foreclosure of Wardenclyffe.

This effectively locked Tesla out of any future development of the facility.

Tesla attempted to market several devices based on the production of ozone.

These included his 1900 Tesla Ozone Company selling an 1896 patented device based on his Tesla coil, used to bubble ozone through different types of oils to make a therapeutic gel.

He also tried to develop a variation of this a few years later as a room sanitizer for hospitals.

Tesla theorized that the application of electricity to the brain enhanced intelligence.

In 1912, he crafted “a plan to make dull students bright by saturating them unconsciously with electricity,” wiring the walls of a schoolroom and, “saturating the schoolroom with infinitesimal electric waves vibrating at high frequency.

The whole room will thus, Mr. Tesla claims, be converted into a health-giving and stimulating electromagnetic field or ‘bath.'”

The plan was, at least provisionally, approved by then superintendent of New York City schools, William H. Maxwell.

Before World War I, Tesla sought overseas investors.

After the war started, Tesla lost the funding he was receiving from his patents in European countries.

In the August 1917 edition of the magazine Electrical Experimenter, Tesla postulated that electricity could be used to locate submarines via using the reflection of an “electric ray” of “tremendous frequency,” with the signal being viewed on a fluorescent screen (a system that has been noted to have a superficial resemblance to modern radar).

Tesla was incorrect in his assumption that high frequency radio waves would penetrate water.

Émile Girardeau, who helped develop France’s first radar system in the 1930s, noted in 1953 that Tesla’s general speculation that a very strong high-frequency signal would be needed was correct.

Girardeau said:

“Tesla was prophesying or dreaming, since he had at his disposal no means of carrying them out, but one must add that if he was dreaming, at least he was dreaming correctly.”

Above: Émile Girardeau (1882 – 1970)

In 1928, Tesla received U.S. Patent 1,655,114, for a biplane capable of taking off vertically (VTOL aircraft) and then of being “gradually tilted through manipulation of the elevator devices” in flight until it was flying like a conventional plane.

Tesla thought the plane would sell for less than $1,000, although the aircraft has been described as impractical.

Above: VTOL (vertical take-off/landing) Harrier

This would be his last patent and at this time Tesla closed his last office at 350 Madison Avenue, which he had moved into two years earlier.

Above: Borden Building, 350 Madison Avenue, New York City

Since 1900, Tesla had been living at the Waldorf Astoria in New York running up a large bill.

Above: Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

In 1922, he moved to St. Regis Hotel and would follow a pattern from then on of moving to a new hotel every few years leaving behind unpaid bills.

Above: St. Regis New York

Tesla would walk to the park every day to feed the pigeons.

He took to feeding them at the window of his hotel room and bringing the injured ones in to nurse back to health.

He said that he had been visited by a specific injured white pigeon daily.

Tesla spent over $2,000, including building a device that comfortably supported her so her bones could heal, to fix her broken wing and leg.

Tesla stated:

I have been feeding pigeons, thousands of them for years.

But there was one, a beautiful bird, pure white with light grey tips on its wings.

That one was different.

It was a female.

I had only to wish and call her and she would come flying to me.

I loved that pigeon as a man loves a woman, and she loved me.

As long as I had her, there was a purpose to my life.

Tesla’s unpaid bills, and complaints about the mess from his pigeon-feeding, forced him to leave the St. Regis in 1923, the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1930 and the Hotel Governor Clinton in 1934.

At one point, he also took rooms at the Hotel Marguery.

In 1934, Tesla moved to the Hotel New Yorker and Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company began paying him $125 per month as well as paying his rent, expenses the company would pay for the rest of Tesla’s life.

Accounts of how this came about vary.

Several sources say Westinghouse was worried (or warned) about potential bad publicity surrounding the impoverished conditions under which their former star inventor was living.

The payment has been described as being couched as a “consulting fee” to get around Tesla’s aversion to accept charity, or according to one biographer as a type of unspecified settlement.

Tesla worked every day from 9:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. or later, with dinner from exactly 8:10 p.m., at Delmonico’s restaurant and later the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Tesla would telephone his dinner order to the headwaiter, who also could be the only one to serve him.

“The meal was required to be ready at eight o’clock …

He dined alone, except on the rare occasions when he would give a dinner to a group to meet his social obligations.

Tesla would then resume his work, often until 3:00 a.m.”

For exercise, Tesla walked between 8 and 10 miles (13 and 16 km) per day.

He curled his toes one hundred times for each foot every night, saying that it stimulated his brain cells.

Tesla became a vegetarian in his later years, living on only milk, bread, honey and vegetable juices.

Tesla read many works, memorizing complete books and supposedly possessed a photographic memory.

He was a polyglot, speaking eight languages: Serbo-Croatian, Czech, English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, and Latin.

Tesla claimed never to sleep more than two hours per night.

However, he did admit to “dozing” from time to time “to recharge his batteries.”

On one occasion at his laboratory, Tesla worked for a period of 84 hours without rest.

Kenneth Swezey, a journalist whom Tesla had befriended, confirmed that Tesla rarely slept.

Swezey recalled one morning when Tesla called him at 3 a.m.:

“I was sleeping in my room like one dead …

Suddenly, the telephone ring awakened me …

Tesla spoke animatedly, with pauses, as he worked out a problem, comparing one theory to another, commenting.

And when he felt he had arrived at the solution, he suddenly closed the telephone.”

Tesla was asocial and prone to seclude himself with his work.

However, when he did engage in a social life, many people spoke very positively and admiringly of Tesla.

Writer Robert Underwood Johnson described him as attaining a “distinguished sweetness, sincerity, modesty, refinement, generosity, and force.”

Above: Robert Underwood Johnson (1853 – 1937)

His secretary, Dorothy Skerrit, wrote:

“His genial smile and nobility of bearing always denoted the gentlemanly characteristics that were so ingrained in his soul.”

Tesla’s friend, writer Julian Hawthorne, commented:

“Seldom did one meet a scientist or engineer who was also a poet, a philosopher, an appreciator of fine music, a linguist, and a connoisseur of food and drink.”

Above: Julian Hawthorne (1846 – 1934)

Tesla was a good friend of Francis Marion Crawford, Robert Underwood Johnson, Stanford White, Fritz Lowenstein, George Scherff and Kenneth Swezey.

In middle age, Tesla became a close friend of Mark Twain.

They spent a lot of time together in his lab and elsewhere.

Twain notably described Tesla’s induction motor invention as “the most valuable patent since the telephone.”

Above: Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain)(1835 – 1910)

At a party thrown by actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1896, Tesla met Indian Hindu monk Vivekananda and the two talked about how the inventors ideas on energy seemed to match up with Vedantic cosmology.

Above: Narendranath Datta (aka Swami Vivekananda)(1863 – 1902)

In the late 1920s, Tesla befriended George Sylvester Viereck, a poet, writer, mystic, and later, unfortunately, a Nazi propagandist.

Tesla occasionally attended dinner parties held by Viereck and his wife.

Above: George Viereck (1884 – 1962)

Tesla could be harsh at times and openly expressed disgust for overweight people, such as when he fired a secretary because of her weight.

He was quick to criticize clothing.

On several occasions, Tesla directed a subordinate to go home and change her dress.

When Thomas Edison (b. 1847) died, in 1931, Tesla contributed the only negative opinion to The New York Times, buried in an extensive coverage of Edison’s life:

He had no hobby, cared for no sort of amusement of any kind and lived in utter disregard of the most elementary rules of hygiene …

His method was inefficient in the extreme, for an immense ground had to be covered to get anything at all unless blind chance intervened and, at first, I was almost a sorry witness of his doings, knowing that just a little theory and calculation would have saved him 90% of the labor.

But he had a veritable contempt for book learning and mathematical knowledge, trusting himself entirely to his inventor’s instinct and practical American sense.

Tesla was 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) tall and weighed 142 pounds (64 kg), with almost no weight variance from 1888 to about 1926.

His appearance was described by newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane as “almost the tallest, almost the thinnest and certainly the most serious man who goes to Delmonico’s regularly“.

He was an elegant, stylish figure in New York City, meticulous in his grooming, clothing, and regimented in his daily activities, an appearance he maintained as to further his business relationships.

He was also described as having light eyes, “very big hands“, and “remarkably big” thumbs.

Hugo Gernsback was literally spellbound with Tesla and believed that the ideas of the great inventor were the salvation for all of mankind.

This is how Gernsback describes Tesla in the February 1919 issue of Electrical Experimenter:

“The door opens and out steps a tall figure – over six feet high – gaunt but erect.

It approaches slowly, stately.

You become conscious at once that you are face to face with a personality of a high order.

Nikola Tesla advances and shakes your hand with a powerful grip, surprising for a man over 60.

A winning smile from piercing light blue-gray eyes, set in extraordinarily deep sockets, fascinates you and makes you feel at once at home.

You are guided into an office immaculate in its orderliness.

Not a speck of dust is to be seen.

No papers litter the desk.

Everything just so.

It reflects the man himself, immaculate in attire, orderly and precise in his every movement.

Dressed in a dark frock coat, he is entirely devoid of all jewelry.

No ring, stickpin or even watch-chain can be seen.

Tesla speaks – a very high almost falsetto voice.

He speaks quickly and very convincingly.

It is the man’s voice chiefly which fascinates you.

As he speaks you find it difficult to take your eyes off his own.

Only when he speaks to others do you have a chance to study his head, predominant of which is a very high forehead with a bulge between his eyes – the neverfailing sign of an exceptional intelligence.

Then the long, well-shaped nose, proclaiming the scientist….

His only vice is his generosity.

The man who, by the ignorant onlooker has often been called an idle dreamer, has made over a million dollars out of his inventions – and spent them as quickly on new ones.

But Tesla is an idealist of the highest order and to such men money itself means but little.”

I wonder if Tesla felt the same towards Gernsback….

Gernsback was noted for sharp (and sometimes shady) business practices,and for paying his writers extremely low fees or not paying them at all.

H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith referred to him as “Hugo the Rat“.

As Barry Malzberg has said:

Gernsback’s venality and corruption, his sleaziness and his utter disregard for the financial rights of authors, have been well documented and discussed in critical and fan literature

That the founder of genre science fiction who gave his name to the field’s most prestigious award and who was the Guest of Honor at the 1952 Worldcon was pretty much a crook (and a contemptuous crook who stiffed his writers but paid himself $100K a year as President of Gernsback Publications) has been clearly established.

Nonetheless, Gernsback earned Tesla’s sympathy and Gernsback became an important publisher of Tesla’s articles in his many publications.

In the August 1917 Electrical Experimenter, under the title “Tesla’s Views on Electricity and the War“, Tesla made the first technical description of radar.

The author of the article (H. Winfield Secor, the magazine’s Associate Editor) explained to his readers that “Dr. Tesla had invented, among other things, an electric ray to destroy or detect submarines under water at a considerable distance.

Mr. Tesla very courteously granted the writer an interview and some of his ideas on electricity’s possible role in helping to end the Great War.”

Later that year, in addition to Tesla’s autobiographical serial My Inventions, the Electrical Experimenter also published a number of other Tesla-authorized articles with considerable regularity:

- The Effect of Statics on Wireless Transmission

- Famous Scientific Illusions

- Tesla’s Egg of Columbus (or how Tesla performed the feat of Columbus without cracking the Egg)

- The Moon’s Rotation

- The True Wireless

- Tesla’s Bulbs

- Electrical Oscillators

- Can Radio Ignite Balloons?(or the Opinions of Nikola Tesla and Other Radio Experts)

Tesla and Gernsback started correspondence with one another from the end of 1918 and throughout 1919.

Tesla could not fit himself into the strict deadlines presented to him by the rules of periodical press and wrote to Gernsback at the end of July 1919:

“I think it well on this occasion to notify your readers, as a precaution, that I am not one of those who display the sign ‘Do it now.’ on their desks and office doors.

My motto is: ‘Do not do it now. Think it over.‘ ”

Over the next several years, only a few letters were exchanged between Tesla and Gernsback, in which the famous publisher tried whatever he could to appease his most prominent writer and resume their cooperation, but as a reply received very cold letters, demonstrating Tesla’s injured pride and his objections to the egoism of the publisher.

In one of the last letters, Tesla wrote:

“I appreciate your unusual intelligence and enterprise but the trouble with you seems to be that you are thinking only of H. Gernsback first of all, once more and then again.”

Tesla wrote a number of books and articles for magazines and journals.

Among his books are My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla, The Fantastic Inventions of Nikola Tesla and The Tesla Papers.

Many of Tesla’s writings are freely available online, including the article “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy,” published in The Century Magazine in 1900 and the article “Experiments With Alternate Currents Of High Potential And High Frequency” published in his book Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla.

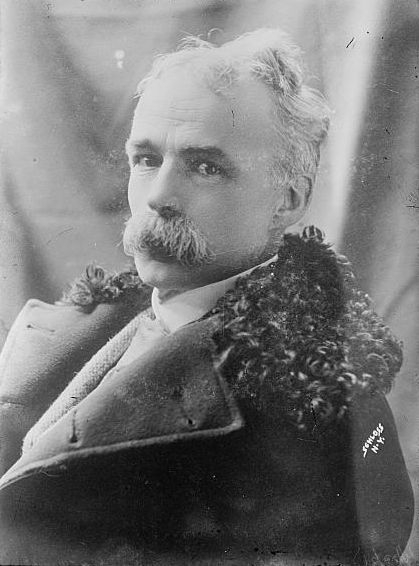

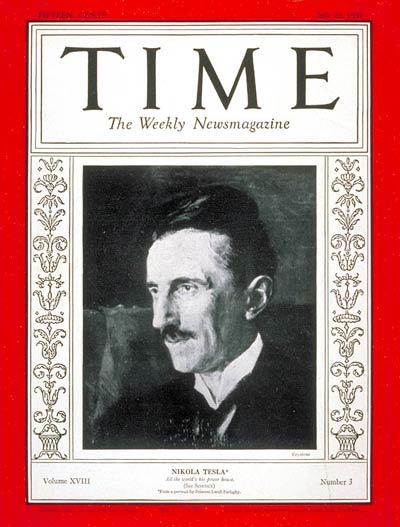

In 1931, Kenneth Swezey, a young writer who had been associated with Tesla for some time, organized a celebration for the inventor’s 75th birthday.

Tesla received congratulatory letters from more than 70 pioneers in science and engineering, including Albert Einstein, and he was also featured on the cover of Time magazine.

The cover caption “All the world’s his power house” noted his contribution to electrical power generation.

The party went so well that Tesla made it an annual event, an occasion where he would put out a large spread of food and drink (featuring dishes of his own creation) and invite the press to see his inventions and hear stories about past exploits, views on current events, or sometimes odd or baffling claims.

At the 1932 occasion, Tesla claimed he had invented a motor that would run on cosmic rays.

In 1933, at age 77, Tesla told reporters that, after thirty-five years of work, he was on the verge of producing proof of a new form of energy.

He claimed it was a theory of energy that was “violently opposed” to Einsteinian physics and could be tapped with an apparatus that would be cheap to run and last 500 years.

He also told reporters he was working on a way to transmit individualized private radio wavelengths, working on breakthroughs in metallurgy, and developing a way to photograph the retina to record thought.

At the 1934 party, Tesla told reporters he had designed a superweapon he claimed would end all war.

He would call it “teleforce“, but was usually referred to as his death ray.

Tesla described it as a defensive weapon that would be put up along the border of a country to be used against attacking ground-based infantry or aircraft.

Tesla never revealed detailed plans of how the weapon worked during his lifetime, but in 1984, they surfaced at the Nikola Tesla Museum archive in Belgrade.

The treatise, The New Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through the Natural Media, described an open-ended vacuum tube with a gas jet seal that allows particles to exit, a method of charging slugs of tungsten or mercury to millions of volts, and directing them in streams (through electrostatic repulsion).

Tesla tried to interest the US War Department, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia in the device.

In 1935, at his 79th birthday party, Tesla covered many topics.

He claimed to have discovered the cosmic ray in 1896 and invented a way to produce direct current by induction, and made many claims about his mechanical oscillator.

Describing the device (which he expected would earn him $100 million within two years) he told reporters that a version of his oscillator had caused an earthquake in his 46 East Houston Street lab and neighboring streets in downtown New York City in 1898.

He went on to tell reporters his oscillator could destroy the Empire State Building with 5 lbs of air pressure.

He also explained a new technique he developed using his oscillators he called “Telegeodynamics“, using it to transmit vibrations into the ground that he claimed would work over any distance to be used for communication or locating underground mineral deposits.

At his 1937 celebration in the Grand Ballroom of Hotel New Yorker, Tesla received the “Order of the White Lion” from the Czechoslovakia ambassador and a medal from the Yugoslavian ambassador.

On questions concerning the death ray, Tesla stated:

“But it is not an experiment …

I have built, demonstrated and used it.

Only a little time will pass before I can give it to the world.”

In the fall of 1937, after midnight one night, Tesla left the Hotel New Yorker to make his regular commute to the cathedral and the library to feed the pigeons.

While crossing a street a couple of blocks from the hotel, Tesla was unable to dodge a moving taxicab and was thrown to the ground.

His back was severely wrenched and three of his ribs were broken in the accident.

The full extent of his injuries were never known.

Tesla refused to consult a doctor, an almost lifelong custom, and never fully recovered.

On 7 January 1943, at the age of 86, Tesla died alone in Room 3327 of the New Yorker Hotel.

Above: Room 3327, New Yorker Hotel, Present day

His body was later found by maid Alice Monaghan after she had entered Tesla’s room, ignoring the “do not disturb” sign that Tesla had placed on his door two days earlier.

Assistant medical examiner H.W. Wembley examined the body and ruled that the cause of death had been coronary thrombosis.

Two days later the Federal Bureau of Investigation ordered the Alien Property Custodian to seize Tesla’s belongings.

John G. Trump, a professor at MIT and a well-known electrical engineer serving as a technical aide to the National Defense Research Committee, was called in to analyze the Tesla items, which were being held in custody.

Above: John G. Trump (1907 – 1985)(Donald’s paternal uncle)

After a three-day investigation, Trump’s report concluded that there was nothing which would constitute a hazard in unfriendly hands, stating:

Tesla’s thoughts and efforts during at least the past 15 years were primarily of a speculative, philosophical, and somewhat promotional character often concerned with the production and wireless transmission of power, but did not include new, sound, workable principles or methods for realizing such results.

In a box purported to contain a part of Tesla’s “death ray“, Trump found a 45-year-old multidecade resistance box.

At the request of Gernsback, on 9 January 1943, two days after Tesla’s death, a death mask of the inventor was made by F. Moynihan.

On 10 January 1943, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia (1882 – 1947) read a eulogy written by Slovene-American author Louis Adamic live over the WNYC radio while violin pieces “Ave Maria” and “Tamo daleko” were played in the background.

On 12 January, two thousand people attended a state funeral for Tesla at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine.

After the funeral, Tesla’s body was taken to the Ferncliff Cemetery in Ardsley, New York, where it was later cremated.

The following day, a second service was conducted by prominent priests in the Trinity Chapel (today’s Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sava) in New York City.

Above: Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sava, New York City

On the occasion of 100 years since Tesla’s birth, on 25 June 1956, the aforementioned death mask was placed on the business premises of Gernsback Publications in New York.

On a marble pedestal, in relief, were presented the symbols of Tesla’s greatest discoveries and ideas – the first induction motor, Tesla’s transformer, and the famous Wardenclyffe Tower at Long Island intended for the “World System” project….

An astonishly accurate prediction of the electronic and wireless world we live in today.

The symbol of Tesla’s great and unfulfilled dream.

In Hugo Gernback’s honour, the Hugo Awards or “Hugos” are the annual achievement awards presented at the World Science Fiction Convention, selected in a process that ends with vote by current Convention members.

They originated and acquired the “Hugo” nickname during the 1950s and were formally defined as a convention responsibility under the name “Science Fiction Achievement Awards” early in the 1960s.

The nickname soon became almost universal and its use legally protected; “Hugo Award(s)” replaced the longer name in all official uses after the 1991 cycle.

In 1960 Gernsback received a special Hugo Award as “The Father of Magazine Science Fiction“.

Hugo Gernsback died at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City on 19 August 1967.

In late 2002 Gernsback Publications went out of business.

Tesla’s legacy has endured in books, films, radio, TV, music, live theater, comics and video games.

In Jim Jarmusek’s film Coffee and Cigarettes, Jack shows Meg his Tesla coil!

Tesla features prominently in the movies The Prestige (David Bowie as Tesla) and The Current War, as well as in Family Guy‘s Season 9, Episode 15.

Above: David Bowie as Nikola Tesla, The Prestige

Tesla appears in Ron Horsley’s and Ralph Vaughan’s re-imaginings of the famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes.

In The Big Bang Theory, Tesla is referred to as “a poor man’s Sheldon Cooper“.

In 2011, Sesame Street introduced the world to grumpy Professor “Nikola Messla“.

The impact of the technologies invented or envisioned by Tesla is a recurring theme in several types of science fiction.

In science and engineering Tesla has given his name to the Tesla coil and the singing Tesla coil, Tesla’s Egg of Columbus, the Tesla Experimental Station, Tesla’s oscillator, the Tesla Principle, the Tesla Tower, the Tesla turbine, the Tesla unit and the Tesla valve.

Tesla is a 26-km wide crater on the far side of the Moon as well as a minor planet (2244 Tesla).

There is both the Nikola Tesla Award and the Nikola Tesla Satellite Award.

Tesla was an electrotechnical conglomerate in the former Czechoslovakia.

Tesla is an American electric car manufacturer, the Croatian affliliate of the Swedish telecommunications equipment manufacturer Ericsson, a bank in Zagreb and two companies in the Serbian cities of Novi Sad and Plandiste.

His birthday (10 July) is celebrated every year in Croatia, in Vojvodina and in Niagara Falls.

Every year the annual Nikola Tesla Electric Vehicle Rally is held in Croatia.

In music, there is Tesla (US), Tesla Boy (Russia) and Tesla Coils (Australia) – all the names of band groups, while “Tesla Girls” is a song by the British pop band Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD) released in 1984.

The groups They Might Be Giants released “Tesla“, The Handsome Family “Tesla’s Hotel Room” and the Polish band Silver Rocket‘s last album was named “Tesla“.

There is a Tesla STEM High School in Redmond, Washington.

Tesla is both an Airport and a Museum in Belgrade.

TPP Nikola Tesla is the largest power plant in Serbia.

And 128 streets in Croatia have been named after Nikola Tesla, making him the 8th most common street name in the country.

It took me a few hours, despite the Museum’s small size, for my eyes to absorb all that was revealed about Tesla here.

It has taken me months for my mind to absorb all that I have learned since my visit.

But of all of this I find myself drawn not to his inventions but to his character.

I walked away from the Museum that day, sat on a bench and watched a pigeon approach.

I thought of Tesla.

The pigeon and I looked at each other.

No words were needed.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Nikola Tesla, My Inventions / Vladimir Dulovic, Serbia In Your Hands / Marija Stosic, Belgrade