Landschlacht, Switzerland, 20 April 2019

The Norwegians find them insufferably puffed up.

The Danes consider them to be party poopers.

The Brits see them as sexy but cold.

The Americans think they are Swiss!

Above: Flag of Sweden

Author Sven Linquist summed it up thus:

The Swedes look at the world through a square frame nailed together by Martin Luther, Gustav Vasa (the founder of the Swedish state), the Temperance Movement and 100 years of socialism.

Luther contributed the Swedish taste for simplicity.

Vasa gave the Swedes a national identity.

The Temperance Movement gave rise to the Swedish tendency to be sanctimonious.

Socialism gave the Swedes a mentality of work as necessary but not everything.

Foreigners living in Sweden find the natives socially impenetrable, as neighbours mind their own business and colleagues go straight home after work.

The Swedes themselves don’t actually dislike any nation in particular, because they are quietly confident in Swedish superiority.

Foreigners are good news, because with their funny faces and horrific habits they remind Swedes how wonderful it is to be Swedish and normal.

I have vacationed in Sweden with my wife and I have worked with a Swede in Switzerland and I find very little that is objectionable about the Swedes.

I find them less puffed up than Parisians, more party hardy than my fellow Canadians, as sexy as teenage voyeurism once suggested but not tempting enough to test my marriage vows, and I see in them more similarities with their Scandinavian neighbours than they would care to admit.

Simple?

Maybe the architecture and IKEA furniture is, but a Swedish woman is no less and no more complicated than her international counterparts.

Patriotic?

Certainly, they are not more patriotic than Canadians or Swiss.

Though they display their national flag everywhere as the Americans do theirs, the Swedish are far more secure in their superiority than the Americans are.

The Swedes don’t need to boast.

They simply and quietly know their own value.

Above: The coat of arms of Sweden

Sanctimonious?

Perhaps the women are, for the Swedes believe that they are the first in the world to achieve total equality between the sexes, thus a man who isn’t taciturn and submissive is a threat to that uneasy balance between the sexes.

I feel that in the quest to be emancipated the Swedish female feels threatened if the male requests the same.

Only a woman dares tell a man how wrong he is.

A man dares not do the same to her without serious conflict and consequence.

As for the work ethic, I can only say that the Sweet Suede that I once worked with was a hardy and competent and well-respected worker beloved by both staff and customers.

I never thought that I would even think about Sweden and Swedish women during my visit to the Alsace Wine Route.

I was wrong.

Alsace, France, 2 January 2019

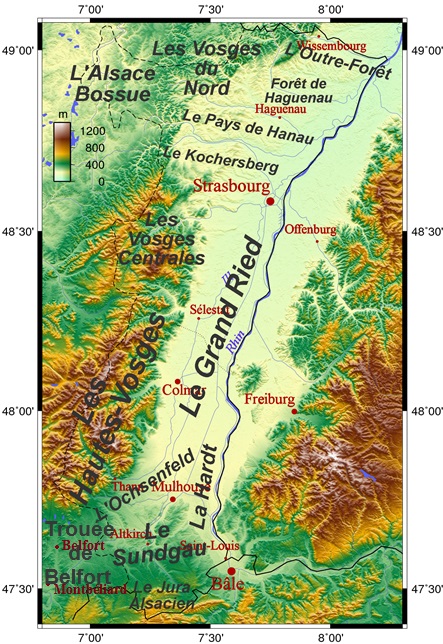

Alsace is the smallest region in France as regards area, but the most highly populated as regards density.

Alsace has 1,734,000 inhabitants – 209 inhabitants per square kilometre, whereas the average number of inhabitants per square kilometre in Metropolitan France is 108.

This is by no means the only peculiarity of this region….

Officially the Alsace Wine Route is broken into two sections: the one most folks travel and the northern section most don’t.

The northern section begins in the town of Wissembourg.

I have written about Wissembourg before.

A monastery town and former garrison, Wissembourg offers numerous attractions such as the Abbey Church of St. Peter and St. Paul with its gigantic representation of St. Christopher, the Fritz House built in 1550, and the Bruch – the town’s old quarter.

(Please see Canada Slim and the Burning King of my other blog Building Everest for more on Wissembourg. https://buildingeverest.wordpress.com)

Far away from the traditional half of the famous Alsatian wine route between Marlenheim and Thann, quite competitive wine is also being produced near Wissembourg at the base of the first foothills of the northern Vosges in heavy, fat clay soil.

Viticulture here has a long tradition.

Introduced by the roamin’ Romans, later promoted by the monks of Wissembourg, today 200 sideline wine makers cultivate some 175 hectares of all sorts of grape varieties like Graubünden, Pinot Blanc and Gewürztraminer, from the five villages of Rott, Oberhoffen, Steinseltz, Riedseltz and Cleebourg.

Private wine sales are not common as the wine makers deliver almost all of their grapes to the Cleebourg Wine Cooperative which wine lovers should not miss.

In the lovely hilly countryside around the five villages with their vineyards and numerous fruit trees you can also go for a walk and then stop in at the Ferme Auberge Moulin des 7 Fontaines (Mill of the Seven Fountains) in the area – a particularly beautiful place.

A 47 minute, 3.5 kilometre stroll south west of Wissembourg finds the pedestrian in the village of Rott (population: 473) where one finds a barrel that the enterprising Mayor Louis Andres Rott turned into a bar, engraved with the worthy maxim:

“If you drink, you die.

If you don’t drink you die, so….“

Above: Rott, Alsace, France

Rott is one of 50 Alsatian communities with a simultaneum (or shared church) with different Christian denominations meeting at different times and presided over by different clergy.

Above the village on the Col de Pigeonnier stands the electric tower, the Émetteur de l’Eselsberg.

The Cleebourg vineyard is at the northernmost point of the Alsatian winemaking area and covers all its communes as well as Wissembourg, the main town in the canton.

The vineyard stretches from Rott, with its belfry / clock tower overlooking the cemetery that doubled as a defensive hideout in the 18th century, to Riedseltz on the banks of the Rhine.

Planted mainly with hybrids or fallen into disuse until the end of the Second World War, the vines were uprooted and the vineyards replanted with the now-famous classic Alsace varieties since the 1950s.

The local wine producers belong to the Cleebourg cooperative, which has an excellent reputation for all things Pinot, including a blanc de blanc crémant, the Prince Casimir.

Follow the signs of the small rural routes to the village of Oberhoffen lès Wissembourg.

With about 300 inhabitants, Oberhoffen-lès-Wissembourg is one of the smallest communes in the community of communes whose main resource comes from the communal forest.

Orchards and vineyards surround the village.

The vines that contribute to the development of the Karschweg, the Pinot gris (formerly Tokay pinot gris) local vinified by the Cleebourg cooperative cellar.

The discovery of the village can also be done by taking the tree path that crosses the town.

Located at the foot of the Vosges hills, Oberhoffen-lès-Wissembourg was first attached to the bailiwick of Cleebourg, then passed under the influence of Puller de Hohenbourg to finish as the Duchy of Deux-Ponts where it will remain until the revolution.

It was not until 1927 that the town became known as Oberhoffen-lès-Wissembourg because of its geographical proximity to Wissembourg.

Close by is the equally small village of Steinseltz by the River Hausauerbach in the region known as Outre-Forêt (“beyond the forest“).

The origin of the history of Steinseltz is closely linked to that of the Abbey of Wissembourg, founded in the 8th century by the monk Dagobert of Speyer.

Locals still bear witness to this distant time like that of Auf der Hub.

A hub was a plot of land rented by the convent to private individuals against a well-defined tenancy.

In 1401, after the decline of the Abbey of Wissembourg, the lords of Hohenbourg, seized the village as well as those of Cleebourg, Oberhoffen-lès-Wissembourg and Rott.

His successor Wirich II built Castle Cleebourg in 1412.

In 1475, Wirich III allied with Duke Louis de Deux-Ponts against the Elector Palatine Frédéric.

Victorious, the latter annexed the village of Steinseltz.

In 1504, Maximilian of Habsburg attributed the village of Steinseltz to the Duchy of Zweibrücken, which thus exercised a right of collation.

They integrated Steinseltz to the Bailiwick of Cleebourg, which they held until the Revolution.

On 4 August 1870, the Imperial Prince Frederick William went to the locality of Schafbusch to bow before the remains of Abel Douay.

In Steinseltz, every August in odd years, there is a feast in honor of the geranium, a symbol of Alsace.

At the heart of the village, Ferme Burger welcomes, every first Wednesday of the month, a market of local and organic products.

There are food products (breads, vegetables, fruits, oils, chocolate, honey) as well as aesthetic products such as essential oils, soaps or herbs.

And Steinseltz produced Marie….

Marie (Trautmann) Jaëll (17 August 1846 – 4 February 1925) was a French pianist, composer and pedagogue.

Marie Jaëll composed pieces for piano, concertos, quartets, and others.

She dedicated her cello concerto to Jules Delsart and was the first pianist to perform all the piano sonatas of Beethoven in Paris.

She did scientific studies of hand techniques in piano playing and attempted to replace traditional drilling with systematic piano methods.

Her students included Albert Schweitzer, who studied with her while also studying organ with Charles-Marie Widor in 1898-99.

Her father was the mayor of Steinseltz in Alsace and her mother was a lover of the arts.

She began piano studies at the age of six and by seven, she was studying under piano pedagogues F.B. Hamma and Ignaz Moscheles in Stuttgart.

Marie’s mother served as her advocate and manager.

A year after she began lessons with Hamma and Moscheles, she gave concerts in Germany and Switzerland.

In 1856, the ten-year-old Marie was introduced to the piano teacher Heinrich Herz at the Paris Conservatory.

After just four months as an official student at the Conservatory, she won the First Prize of Piano.

Her performances were recognized by the public and local newspapers.

The Revue et gazette musicale printed a review on 27 July 1862 that read: “She marked the piece with the seal of her individual nature.

Her higher mechanism, her beautiful style, her play deliciously moderate, with an irreproachable purity, an exquisite taste, a lofty elegance, constantly filled the audience with wonder.”

On August 9, 1866, at twenty years of age, Marie married the Austrian concert pianist, Alfred Jaëll.

Above: Alfred Jaell (1832 – 1882)

She was then known variously as Marie Trautmann, Marie Jaëll, Marie Jaëll Trautmann or Marie Trautmann Jaëll.

Alfred was fifteen years older than Marie and had been a student of Chopin.

The husband and wife team performed popular pieces, duos, solos, and compositions of their own throughout Europe and Russia.

As a pianist, Marie specialized in the music of Schumann, Liszt, and Beethoven.

They transcribed Beethoven’s “Marcia alla Turca Athens Ruins” for piano.

The score was successfully published in 1872.

Alfred was able to use his success and fame to help Marie meet with various composers and performers throughout their travels.

In 1868, Marie met the composer and pianist Franz Liszt.

A record of Liszt’s comments about Marie survives in an article published in the American Record Guide:

“Marie Jaëll has the brains of a philosopher and the fingers of an artist.“

Liszt introduced Marie to other great composers and performers of the day—for example, Johannes Brahms and Anton Rubinstein.

By 1871, Marie’s compositions began to be published.

With the death of her husband in 1881, Marie had the opportunity to study with Liszt in Weimar and with Camille Saint-Saëns and César Franck in Paris.

She also had composition lessons with César Franck and Camille Saint-Saëns, who dedicated his Piano Concerto No. 1 and the Étude en forme de valse to her.

Saint-Saëns thought highly enough of Marie to introduce her to the Society of Music Composers—a great honor for women in those days.

After struggling with tendonitis, Jaëll began to study neuroscience.

The strain on her playing and performing led her to research physiology.

Jaëll studied a wide variety of subjects pertaining to the functioning of the body and also ventured into psychology:

“She wanted to combine the emotional and spiritual act of creating beautiful music with the physiological aspects of tactile, additive, and visual sensory.“

Dr. Charles Féré assisted Jaëll in her research of physiology.

Her studies included how music affects the connection between mind and body, as well as how to apply this knowledge to intelligence and sensitivity in teaching music.

Liszt’s music had such a tremendous influence on Jaëll that she sought to gain as much insight into his methods and techniques as possible.

This research and study lead to Jaëll creating her own teaching method based on her findings.

Jaëll’s teaching method was known as the ‘Jaëll Method‘.

Her method was created through a process of trial and error with herself and her students.

Jaëll’s goal was for her students to feel a deep connection to the piano.

An eleven-book series on piano technique resulted from her research and experience.

Piano pedagogues have since drawn insight into teaching techniques of the hand from her method and books.

In fact, her method is still in use today.

As a result of her studies, Jaëll was able to compile her extensive research into a technique book entitled L’intelligence et le rythme dans les mouvements artistiques.

This text is used by pianists and piano pedagogues as a reference, specifically with hand position and playing techniques.

She died in Paris.

Walk out of Jaell’s Steinseltz and head west and then south following signposts to Cleebourg.

Cleebourg is a quiet village, with some half-timbered winemakers’ houses built on sandstone bedrock.

Cleebourg’s vineyards are the northernmost point of the Wine Route and though they are planted with the classic varieties, Pinot Gris is indisputably the most successful wine made here.

The grapes, grown on a rocky volcanic soil, produce crisp wine with a characteristically smoky aroma with lily undertones.

Cleebourg used to belong to the Palatin Zweibrückens, but a curious love story in the 17th century brought it under the Swedish crown….

John Casimir, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken-Kleeburg (1589 – 1652) was the son of John I, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken and his wife, Duchess Magdalene of Jülich-Cleves-Berg and was the founder of a branch of Wittelsbach Counts Palatine often called the Swedish line, because it gave rise to three subsequent kings of Sweden, but more commonly known as the Kleeburg (or Cleebourg) line.

In 1591 his father stipulated that, as the youngest son, John Casimir would receive as appanage the countship of Neukastell in the Palatinate.

Upon their father’s death in 1611, however, the eldest son, John II, Count Palatine of Zweibrucken, instead signed a compromise with John Casimir whereby the latter received only the castle at Neukastell coupled with an annuity of 3000 florins from the countship’s revenues (similarly, John Casimir’s elder brother, Frederick Casimir, received the castle at Landsberg with a small surrounding domain, instead of the entire Landsberg appanage bequeathed to him paternally).

On 11 June 1615, Casimir married his second cousin Catherine of Sweden, and their son eventually became King Charles X of Sweden.

Five of his children with Catherine survived infancy:

- Christina Magdalena (1616–1662)

- married Frederick VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach.

- King Adolf Frederick of Sweden was her great-grandson.

- King Charles X Gustav of Sweden (1622–1660)

- Maria Eufrosyne (1625–1687)

- married Count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie

- Eleonora Catherine (1626–1692)

- married Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Eschwege

- Adolf John (1629–1689)

Catherine of Sweden (Swedish: Katarina) (1584 – 1638) was a Swedish princess and a Countess Palatine of Zweibrücken as the consort of her second cousin John Casimir of Palatinate-Zweibrücken.

She is known as the periodical foster mother of Queen Christina of Sweden.

Catherine was the daughter of King Charles IX of Sweden and his first spouse Maria of the Palatinate-Simmern.

Her personality was described as “a happy union of her father’s power and wisdom and her mother’s tender humility“.

Her mother died in 1589 and Catherine was placed in the care of the German Euphrosina Heldina von Dieffenau, whom she praised much later in life.

In 1592, her father remarried to Christina of Holstein-Gottorp.

She reportedly got along well with her stepmother and was close to her half siblings, especially her eldest brother, the future King Gustavus Adolphus, who is noted to have been very affectionate toward her.

In later letters to her consort, however, it seems that she was not always as much in agreement with her stepmother as she gave the impression to be.

Her father became regent in 1598 and was crowned king in 1607.

In 1611, her brother succeeded her father as King Gustavus Adolphus.

Her brother found Catherine sensible and wise and she is reported to have acted as his confidante and adviser on several occasions.

Catherine married late for a Princess of her period.

Although she was a great heiress, her status on the international royal marriage market was uncertain because of the political situation in Sweden after her father had conquered the throne from his nephew Sigismund.

Her parents’ marriage had been an alliance with the anti-Habsburg party in Germany, which in turn was allied with King Henry IV of France and the French Huguenots.

In 1599, there were plans to arrange a marriage between her and the Protestant French Prince Henri, Duke of Rohan, leader of the French Huguenots.

Henry married Marguerite de Béthune in 1603.

After the Treaty of Knäred in 1613, her status became more secure.

With the support of her stepmother Queen Dowager Christina, the queen dowager’s brother Archbishop John Frederik of Bremen arranged the marriage between Catherine and her relative (Count Palatine) John Casimir of Palatinate-Zweibrücken.

Though relatively poor, he had contacts which were deemed valuable to Sweden, though Count Axel Oxenstierna opposed the marriage.

The marriage took place on 11 June 1615 in Stockholm.

Above: Stockholm Royal Palace

Catherine was, by the will of both her parents as well as by the law regarding the dowry of Swedish Princesses, one of the wealthiest heirs in Sweden.

As the economic situation at the time was strained, she remained in Sweden the first years after her marriage to guard her interests.

In January 1618, she left for Alsace.

There, the couple was given the Kleeburg Castle as their residence.

The year after, John Casimir started to build a new residence, the Renaissance Palace Katharinenburg near Kleeburg.

In 1620, the Thirty Years’ War forced them to flee to Strasbourg.

In 1622, her brother King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden asked her to return to Sweden with her family.

The death of her younger brother in Sweden, as well as the lack of heirs to the Swedish throne was evidently the reason why the monarch wished to move her to safety away from the Thirty Years’ War.

Catherine accepted the invitation and arrived to Sweden with her family in June 1622.

At her arrival, the birth of her son Charles immediately strengthened her position.

In Sweden, she and her consort were granted Stegeborg Castle and a county in Östergötland as their fief and residence and as payment of her dowry:

Catherine was styled Countess of Stegeborg.

Catherine and John Casimir settled in well at Stegeborg, where they maintained a royal standard of living:

They kept a court with 60 formal ladies-in-waiting and courtiers and an official table.

Catherine actively engaged herself in the management of the estates, and was in 1626 given Skenas Royal Estate as her personal fief.

Catherine was on very good terms with her brother King Gustavus Adolphus, who is known to have asked her for advice.

During his trips, he often asked her to try to console and control his consort, Queen Maria Eleonora.

Catherine was exposed to certain intrigues at court with the purpose of blackening her name in the eyes of the royal couple, but she managed to avoid these plots.

She was on good terms with the dynasties of Pfalz and Brandenburg, with whom she corresponded and who considered her to be wise and to have good judgment.

In 1631, Catherine was given the custody of her niece, Princess Christina, the heir to the throne, when the queen was allowed to join the king in Germany, where he participated in the Thirty Years’ War.

Christina remained in her care until Maria Eleonora returned to Sweden upon the death of Gustavus Adolphus in 1632.

After the death of King Gustavus Adolphus, the couple came in conflict with the Guardian Government of Queen Christina over their position and rights to Stegeborg.

When John Casimir broke with the royal council in 1633, the couple retired from court to Stegeborg.

Catherine did not show any interest in participation in state affairs.

In 1636, however, Queen Dowager Maria Eleonora was deemed an unsuitable guardian and deprived of the custody of the young monarch, and Catherine was appointed official guardian and foster mother with the responsibility of the young queen’s upbringing.

The appointment was made upon the recommendation of Count Axel Oxenstierna and she reportedly accepted the task with reluctance.

This appointment destroyed her relationship with Maria Eleonora.

The years in Catherine’s care are described by Christina as happy ones.

Princess Catherine personally enjoyed great respect and popularity in Sweden as a member of the royal house and as the foster parent of the monarch:

However, this respect did not include her consort, who was given no task or position at court whatsoever.

John Casimir was himself careful to point out her rank as a Royal Princess, but he was himself exposed to some humiliation because of their difference in rank.

One example was at the opening of Parliament in 1633, when Catherine in accordance with the wish of the Royal Council followed Queen Christina in the procession, while John Casimir was given the choice to stand and watch the ceremony from a window or not be present at all.

Catherine died in Västerås, where the royal court had fled from an outbreak of plague in Stockholm.

At her death, Axel Oxenstierna said, that he would rather have buried his own mother twice, than once again see “the premature death of this noble Princess“.

After her death, the royal council appointed two foster mothers for the queen to replace her: Countess Ebba Leijonhufvud and Christina Natt och Dag.

The Katarina kyrka in Stockholm is named after her.

The marriage of John and Katarina reminds me of two other marriages: Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and my own.

Victoria and Albert were, like John and Katarina, cousins.

The Princes Consort were considered less worthy of respect than their lady heiresses to major kingdoms’ thrones.

Both royal couples gave birth to children who would rise to great power.

My wife and I are not cousins nor nobility of any sort, but, like Katarina, my wife is considered sensible and wise.

She, like many women, could certainly have married a man far more appropriate for her and her ambitions, and yet we, like John and Katarina, like Victoria and Albert, have remained together despite our inequalities.

Like John and Katarina, my wife and I lived apart from one another for years despite our union.

I, like John, followed my bride to her home country.

(Less than 4 kilometres south of Cleebourg is the municipality of Drachenbronn-Birlenbach, where one can find both the original site of Katharienburg as well as the Musée Pierre Jost.

The Pierre Jost Museum is situated near the Ouvrage Hochwald, one of the major fortifications of the Maginot Line in France, which documents the story of the fortifications before, during and after World War II.

The Ouvrage Hochwald fortification was built in the Hochwald massif between 1929 and 1935 and was the strongest in Alsace.

It was capable of housing 1,200 men.

It had eleven blocks, with turrets, casemates to house the infantry, three entry blocks and an anti-tank ditch.

Construction of the Museum in honor of the builders and defenders of the Maginot Line began in 1972, led by Pierre Jost.

The Museum was set up in the old M1 magazine.

The original museum was closed in 2009 since it no longer met public safety standards.

On 12 September 2011 the museum was re-opened in building T4 at airbase 901 in Drachenbronn-Birlenbach.

The new premises, opened in time for Heritage Day on 18 September 2011, has more than 350 square metres (3,800 sq ft) of space.

The first room has some artillery pieces, in use until 1940, and press clippings of the early days of liberation towards the end of World War II.

The Museum has rooms for exhibits that cover each period in the life of the fortification:

- Construction in 1930–1935

- Occupation by the French in 1935–1940

- Occupation by the Germans in 1940–1945

- The Cold War, when the fortification was viewed as defense against Soviet tanks advancing towards Paris.

- The room for the 1935–1940 period has the equipment, arms and personal effects of soldiers of that period.

- The 1940–1945 room has German propaganda posters and relics from the liberation.

- Part of the Museum also tells the story of the airbase.

- There are many photographs showing the daily life of the soldiers during the different periods.

Sadly, the Musée Pierre Jost is open only during the Journées des Patrimoine, three days each September.)

Alsace is wine-growing country.

It has long been so and will probably long be so, but Sweden, on the other hand….

Sweden is well north of the area where the European vine, Vitis vinifera, occurs naturally.

There is no tradition of wine production from grapes in the country.

Some sources claim that some monastic vineyards were established when the Roman Catholic church established monasteries in Sweden in medieval times, when Sweden’s climate was milder, but traces of this supposed viticulture are much less evident than the corresponding activities in England, for example.

Small-scale growing of grapes in Swedish orangeries and other greenhouses have occurred for a long time, but the purpose of such plantations were either to provide fruit (grapes) or for decoration or exhibition purposes and not to provide grapes for wine production.

Towards the end of the 20th century, commercial viticulture slowly crept north, into areas than the well-established wine regions, as evidenced by Canadian wine, English wine and Danish wine.

This trend was partially made possible by the use of new hybrid grape varieties and partially by new viticultural techniques.

The idea of commercial freeland viticulture in Sweden appeared in the 1990s.

Some pioneers, especially in Skåne (Scania), took their inspiration from nearby Denmark, where viticulture started earlier than in Sweden, while others took their inspiration from experiences in other winemaking countries.

Perhaps surprisingly, the first two wineries of some size were not established in the far south of Sweden, but in Södermanland County close to Flen (in an area where orchards were common) and on the island of Gotland, which has the largest number of sunshine hours in Sweden.

Later expansions have mostly taken place in Scania, though.

There are also small-scale viticulturalists who grow their grapes in greenhouses rather than in the open.

Small quantities of a few commercial wines made their way into the market via Systembolaget from the early 2000s.

Only a handful of Swedish producers can be considered to be commercial operations, rather than hobby wine makers.

In 2006, the Swedish Board of Agriculture counted four Swedish companies that commercialized wine produced from their own vineyards.

The total production was 5,617 litres (1,236 imperial gallons; 1,484 US gallons), of which 3,632 litres (799 imperial gallons; 959 US gallons) were red and 1,985 litres (437 imperial gallons; 524 US gallons) white, and this amount was produced from around 10 hectares (25 acres) of vineyards.

The Association of Swedish winegrowers estimates 30-40 vinegrowing establishments in Scania, but this number includes hobby growers with a fraction of a hectare of vineyards.

And here’s the thing, the point I am trying to make….

Sometimes things, sometimes people, thrive where no one thinks they will.

Sometimes places, sometimes people, have a past never imagined by others.

There is absolutely no reason to imagine that this quiet obscure section of the Alsace Wine Route could produce anything or anyone worthy of attention.

And yet the wine is very fine and the region has fostered both talent and royalty.

There is absolutely no proof in my possession that John and Katarina ever inspired Swedish wine production through their Alsatian experiences, but nonetheless I am seduced by the possibility.

There was no reason why the Maginot Line should not have defended France for centuries to come.

Unless invading Germans simply go around this line of walled fortifications.

(Trump could learn from the Maginot Line that a border wall is useless if desperate folks use desperate tactics like simply flying over the thing.)

There is no just cause why Alsace should be considered either French or German despite centuries of struggle and bloodshed, for even the smallest of walks through the Alsatian countryside reveals that these people are neither French nor German but are instead indefatiguably, eternally, proudly and uniquely Alsatian.

Is life in this tiny corner of France simple?

It is no less fascinating, no less complicated, than anywhere else humanity has chosen to settle.

Are Alsatians proud French patriots?

In the sense of defending their homes against the destructiveness of invasion, Alsatians are patriotic, but this patriotism is reserved for Alsace alone.

For here the visitor hears both French and German spoken, and sees le francais and Deutsch written everywhere.

Alsace once upon a time was conquered by the French, was then conquered by the Germans, then liberated once more by the French.

But it is a long way, both geographically and philosophically, from Berlin and Paris.

Could one suggest that Alsatians are sanctimonious?

Perhaps.

But only because they quietly know their own value and sense their own superiority.

Today is Saturday and all of this conversing about wine has given me a craving for a fine glass of pinot.

I wonder whether the wine shop between Starbucks and the train station in St. Gallen will be still open after my shift ends.

I wonder whether I will buy a bottle of the Alsatian or the Swedish.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Peter Berlin, Xenophobe’s Guide to the Swedes / Marie-Christine Périllon, Alsace: A Tourist Guide to the Entire Region / Jacky Bind & Jean Claude Colin, Alsace: The Wine Route / Michèle-Caroline Heck, The Golden Book of Alsace / Antje & Gunther Schwab, Elsass / Rough Guide France / Lonely Planet France