Landschlacht, Switzerland, Monday 2 June 2019

Thursday was Ascension Day, a holiday commemorated in both Thurgau Canton (where my wife works) and in St. Gallen Canton (where I work), and, to our mutual surprise, we found ourselves both free from the obligations of employment simultaneously.

A miracle almost as spectacular as someone rising to Heaven in a cloud!

We decided to visit the Hundertwasser Exhibition at the Kunstmuseum in Lindau, Germany, by taking a train to Romanshorn, then another to Rorschach Harbour and then finally a boat across the Lake of Constance to Bavaria’s only port.

This post is not that story, though it is this story that inspires this post.

In thinking about how my wife and I interacted on yesterday’s day trip I invariably compare it to other times we have travelled together.

(For previous posts about Porto, please see Canada Slim and the War of the Oranges as well as Canada Slim and the Station Sanctuary of this blog.)

The wife and I have been together for 23 years – she IS tough – and we always somehow muddle through.

We forgive one another.

She forgives me for being wrong and I forgive her for pointing out how truly wrong I can be!

Sadly, the amnesia of our conflicts is sometimes not as permanent as it should be….

Porto, Portugal, Wednesday 25 July 2018

It is a warm day in this the most western country of Continental Europe and happily we are in a city we both like.

Porto is more than a twee tourist trap of little more than pomp and ceremony, like Lisboa the Portuguese capital.

Porto is Portugal’s Chicago, a busy commercial centre, whose fascination lies in its riverside setting and day-to-day life.

Make no mistake there are sites in Porto worth seeing….

- The riverside barrio of Ribeira with waterfront cafés and restuarants

- The landmark Clérigos Tower

- The Sé, Porto’s cathedral

- The contemporary art gallery and park at the Fondacao de Serralves

- The port wine lodges across the Douro River in Vila Nova de Gaia

- A Douro River cruise

- The bridges that span the Douro: the Ponte Dom Luis I, the Ponte Infante, the Ponte María Pia

- The Salào Árabe of the Palácio da Bosa

Above: Images of Porto

We had walked through the cathedral square the day previously, but this morning we were determined to explore all the sites that surrounded it.

But the morning began badly.

A wardrobe malfunction made us return back to our B & B bedroom.

Then we discovered the English language guidebook we were dependent upon had somehow gone missing.

We returned once again to the room, didn’t find it, so we were forced to find a bookshop and buy the book anew.

We made our way back to the Sé and then she discovered her German-language guidebook was not to be found with us.

She rushed back to the room and left me in the bright sunshine waiting her return.

Set on a rocky outcrop, a couple of hundred metres from Sao Bento Station, Porto’s Cathedral, the Sé, commands fine views over the rooftops.

I look up at the Sé’s North Tower, the one with the bell, and my eyes trace the worn bas-relief depicting a 14th century ship – a reminder of the earlier days of Portugal’s maritime epic, when sailors inched nervously down the west Saharan coastline not knowing what dangers were ahead.

Perhaps my wife’s impatience with the morning was partially affected by our cathedral visit, for the Sé’s interior is a disquieting, disastrous doomsday design of Baroque blended with rough Romanesque and gargantuan Gothic architecture that has a spirit as gloomy as a bride and groom forced to wed whom they do not love.

The Sé is redeemed its ghastly first impressions once the senses escape into the cathedral cloisters, with walls lovingly draped with glowing azulejos and a grand staircase that ascends to the breathtaking chapterhouse for panoramic perspectives of the world from the windows.

The Sé is a holy seductress with a mask of beauty that barely conceals a darkness and depth that dares not expose itself to the light.

The Sé is not an intimate ingress of inspiration but rather a stern sorrow-laden scourge of sin and sacrifice designed to intimidate and threaten those unworthy of salvation.

The old dowager lacks teeth, her majesty missing, her glory gone, her gloom inescapable.

The wife returned to retrieve her German-language Müller Guide which I should have packed in my rucksack and didn’t.

Boys, or men who eternally and internally remain boys, are book-bearing beasts of burden meant to be present but unobtrusive, to be seen but not heard.

I sit in the sun with clear directives to accomplish as set by my bothered bride.

I must plan our progress for the rest of the day.

Planning is never a prospect I embrace, for invariably my plans falls short of her perception of what a perfect plan entails.

I soak the warmth of the sunbaked stone into my already weary bones and tired mind.

I am unmoving and unmoved, immensely immovable.

On the south side of the Sé stretches the grandiose facade of the Paco Episcopal, the medieval archbishop’s palace, where the first King of Portugal was crowned and spent his wedding night.

Like the Sé, the Paco is a mishmash of architectural elements: a Rococo stairway lined with carved granite flowers, Neoclassical doorways with Baroque decor, priceless furniture of luxurious lifestyle exposed to penny-pinching voyeuristic peasants, a lodging financed by a love of God with 17th century Indonesian cabinets hewed from blood and sweat, toil and tears hatefully demanded by harsh Portuguese taskmasters, religious paintings ironically produced in the secular scene of the first Portuguese Republic (1911 – 1956).

The Palace does not intice nor excite me.

But the notion of politics and history does, as I read A.H. de Oliveira Marques’ A Very Short History of Portugal and I wonder, as I often do, at what compels a man to demand better from those who would rule him.

The reckless courage that is required to speak truth to power and demand justice from the unjust has always fascinated me.

I am a foreigner living in Switzerland and though my lot as a Canadian is far more fortunate than that of other nationalities exiled here, there does exist inequalities and injustices enforced by the Swiss upon those who were not born in the Helvetian Republic.

Just to name a few: taxation without any or only minor representation, difficulty to find employment matching the expat’s experience and the unnecessary requirement that rejects qualifications not obtained within Switzerland, the blatant racial and religious profiling done at border crossings by unsympathetic customs pitbull police, the sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant, xenophobia encouraged by the eternally re-elected party in power, the bureaucracy that is bathed with greed and complexity, the fortress mentality of a nation determined to remain neutral yet one that profits from the spoils of war, a people who confuse quality of life by quantity of franks in silent bank vaults and wonder why having it all isn’t so much fun….

I often want to climb the stairs to our apartment building’s roof and shout obscenities down upon the unsuspecting neighbourhood of Landschlacht.

But I lack the courage, for attention garnered may mean expulsion, and, for better or worse, Switzerland has been my home for nine years.

I am a whisper on the Internet, a voice without echo, in a world blind to everything but the square screen of the preset mobile device upon their palms.

I think about what we could tour next.

The house behind the Sé at Rua de Dom Hugo 32 was once the home of the poet and writer Guerra Junquiero whose works reflected the revolutionay turmoil of the Republican era.

Today the Casa Museu Guerra Junquiero exhibits the Iberian and Islamic art, the Seljuk pottery, glassware and glazed earthenwear that he had collected over his lifetime, in rooms that recapture the atmosphere of the poet’s last home.

My guidebooks speak of the Junquiero Museum but none lavishes praise upon it, primarily for the reason that all is written only in Portuguese.

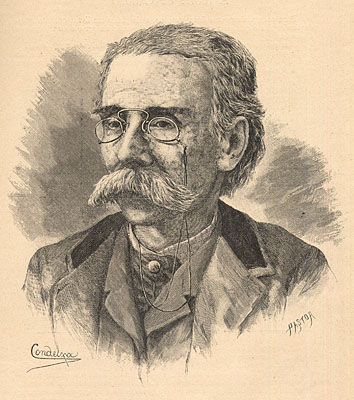

Abílio Manuel Guerra Junqueiro (1850 – 1923) was a Portuguese top civil servant, a member of the Portuguese House of Representatives, a journalist, author and poet.

His work helped inspire the creation of the Portuguese First Republic.

Junqueiro wrote highly satirical poems criticizing conservatism, romanticism and the Church, leading up to the Portuguese Revolution of 1910.

He was one of Europe’s greatest poets.

Born in Freixo de Espada à Cinta, Trás-os-Montes, Portugal to José António Junqueiro Júnior, a supply trader and farmer, and wife Ana Maria Guerra.

His mother died when he was only three years old.

He completed his secondary studies in Bragança and at sixteen, he enrolled at the University of Coimbra to study theology.

Guerra Junqueiro began his literary career in a promising way in Coimbra in the literary journal A Folha, directed by the poet João Penha, of which later he was editor.

Above: Bust of Joao Penha (1838 – 1919), Braga, Portugal

Here Junquiero created friendly relations with some of the best writers and poets of his time, a group generally known as the Generation of 70.

Guerra Junqueiro from a very young age began to manifest remarkable poetic talent, and already by 1867 his name was included among the most hopeful of the new generation of Portuguese poets.

In the same year, in the book entitled The Portuguese Aristarchus, appreciating the book Vozes Sem Echo (Voices without Echo), published in Coimbra in 1867 by Guerra Junqueiro, an auspicious future was already foreseen for its author.

In Porto, on the same date, another work appeared, Baptismo de Amor (Baptism of Love), accompanied by a preamble written by Camilo Castelo Branco.

In Coimbra, Junqueiro published the Lira dos quatorze anos (The Book of Fourteen Years), a volume of poetry, and the poem Mysticae nuptiae.

In Porto, in 1870 the Vitória da Franca (Victory of France) was published, then later republished in Coimbra in 1873.

In 1873, when a republic was proclaimed in Spain, Junquiero wrote the vehement poem À Espanha livre (To free Spain).

Junqueiro concluded his study of law also in 1873.

He became secretary of the governors of Angra do Heroísmo, Azores, and later of Viana do Castelo.

In 1874 his poem A morte de D. Joao (The death of D. João) achieved great success.

Camilo Castelo Branco dedicated an article to him in the Nights of Insomnia, and Oliveira Martins, in the magazine Arts and Letters.

Above: Camilo Castelo Branco (1825 – 1890)

In Lisbon, Junquiero was a contributor of prose and verse, for political and artistic journals, such as The Magic Lantern and António Maria, with the collaboration of drawings by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro.

In 1875 Junquiero wrote O Crime, a poem on the murder of Ensign Palma de Brito, the poem Aos Veteranos da Liberdade (To the Veterans of Freedom) and the volume of Contos para a infancía (Tales for Childhood).

In Diário de Notícias (The Daily News) he also published the poem Fiel e Na Ferra da Ladra (Fiel and the Story of Feira da Ladra).

In 1878 he published in Lisbon the poem Tragédia infantil.

Junquiero collaborated to several periodical publications, namely: Atlantida (1915-1920), Branco e Negro (1896-1898), Brazil Portugal (1899-1914) (1884-1885), The Press, The Universal Illustration (1884-1885), The Portuguese Illustration (1885-1891), Sunday’s Newspaper (1881-1888), The Reading (1894-1896), Light and Life (1879), The West (1878-1915), Renaissance (1878-1879), The Pantheon (1880-1881), The Portuguese Republic (1901-1911), Azulejos (1907-1909), in the Tourism magazine, begun in 1916 and in the newspaper O Azeitonense (1919-1920).

A great part of the poetic compositions of Guerra Junqueiro is reunited in the volume A Musa Em Férias (The Muse on Vacation), published in 1879.

This year he also wrote the poem O Melro (O Blackbird), which was later included in A Velhice do Padre Eterno (The Old Age of the Eternal Father) of 1885.

Idílios e Sátrias (Idylls and Satires) was a translated and collected volume of short stories by Hans Christian Andersen and others.

Above: Hans Christian Andersen (1805 – 1875)

After a stay in Paris, apparently for treatment of digestive disease contracted during his stay in the Azores, Junquiero published in 1885, in Porto, A Velhice do Padre Eterno (The Old Age of the Eternal Father), a work that provoked bitter retorts by the clerical opinion, represented in the press, among others, by the canon José Joaquim de Sena Freitas.

Above: José Joaquim de Sena Freitas (1840 – 1913)

Controversial with regard to religion, other writings of anticlerical nature by its author have been found in periodical publications like The Lucta and The Light (1919 -1921).

When the conflict with England over the “pink map“, which culminated in the British Ultimatum of 11 January 1890, Guerra Junqueiro became deeply interested in this national crisis and wrote Finis Patriae (The end of country) and A Cancao do Ódio (The Song of Hate), to which Miguel Ângelo Pereira wrote the music.

(The 1890 British Ultimatum was an ultimatum by the British government delivered on 11 January 1890 to Portugal.

The ultimatum forced the retreat of Portuguese military forces from areas which had been claimed by Portugal on the basis of historical discovery and recent exploration, but which the United Kingdom claimed on the basis of effective occupation.

Portugal had attempted to claim a large area of land between its colonies of Mozambique and Angola including most of present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia and a large part of Malawi, which had been included in Portugal’s “Rose-coloured Map“.

It has sometimes been claimed that the British government’s objections arose because the Portuguese claims clashed with its aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway, linking its colonies from the south of Africa to those in the north.

Above: British colonies (pink), Portuguese colonies (purple)

This seems unlikely, as in 1890 Germany already controlled German East Africa, now Tanzania, and Sudan was independent under Muhammad Ahmad.

Rather, the British government was pressed into taking action by Cecil Rhodes, whose British South Africa Company was founded in 1888 south of the Zambezi and the African Lakes Company and British missionaries to the north.

Above: Cecil Rhodes (1853 – 1902)

When Portugal acquiesced to British demands, it was considered as a breach of the Treaty of Windsor (1386) and seen as a national humiliation by republicans in Portugal, who denounced the government and the King as responsible for it.

On 14 January, the progressive government fell and the leader of the Regenerador Party, António de Serpa Pimentel, was chosen to form the new government.

Above: António de Serpa Pimental (1825 – 1900)

The progressivists then began to attack the King, voting for republican candidates in the March election of that year, questioning the colonial agreement then signed with the British.

Feeding an atmosphere of near insurrection, on 23 March 1890, António José de Almeida, at the time a student in the University of Coimbra and, later on, President of the Republic, published an article entitled Bragança, o último, considered slanderous against the King and led to Almeida’s imprisonment.

Above: António José de Almeida (1866 – 1929)

On 1 April 1890, the explorer Silva Porto (1817 – 1890) immolated himself (set himself on fire), wrapped in a Portuguese flag in Kuito, Angola, after failed negotiations with the locals, attributed to the Ultimatum.

The death of the well-known explorer of the African continent generated a wave of national sentiment and his funeral was followed by a crowd in Porto.

On 11 April, Guerra Junqueiro’s poetic work Finis Patriae, a satire criticising the King, went on sale.

In the city of Porto, on 31 January 1891, a military uprising against the monarchy took place, constituted mainly by sergeants and enlisted ranks.

The rebels, who used the nationalist anthem A Portuguesa as their marching song, took the Paços do Concelho, from whose balcony, the republican journalist and politician Augusto Manuel Alves da Veiga proclaimed the establishment of the republic in Portugal and hoisted a red and green flag belonging to the Federal Democratic Centre.

The movement was, shortly afterwards, suppressed by a military detachment of the municipal guard that remained loyal to the government, resulting in 40 injured and 12 casualties.

The captured rebels were judged. 250 received sentences of between 18 months and 15 years of exile in Africa.

A Portuguesa was forbidden.

Despite its failure, the rebellion of 31 January 1891 was the first large threat felt by the monarchic regime and a sign of what would come almost two decades later.

The British Ultimatum was considered by Portuguese historians and politicians at that time to be the most outrageous and infamous action of the UK against its oldest ally.

The 1890 ultimatum was said to be one of the main causes for the Republican Revolution, which ended the monarchy in Portugal 20 years later (5 October 1910) and the Lisbon assassinations of the Portuguese king (Carlos I of Portugal) and the crown prince on 1 February 1908.

After the British Ultimatum and the political crisis associated, he was involved in the political debate in 1891, writing some best sellers that had huge impact on public opinion, contributing to the discredit of the Portuguese monarchy and the success of the Portuguese Republican Party in the 1910 Portuguese Revolution.

The 5 October 1910 revolution was the overthrow of the centuries-old Portuguese monarchy and its replacement by the Portuguese Republic.

It was the result of a coup d’état organized by the Portuguese Republican Party.

By 1910, the Kingdom of Portugal was in deep crisis: British pressure on Portugal’s colonies, the royal family’s expenses, the assassination of the King and his heir in 1908, changing religious and social views, instability of the two political parties (Progressive and Regenerador), the dictatorship of João Franco and the regime’s apparent inability to adapt to modern times all led to widespread resentment against the Monarchy.

The proponents of the republic, particularly the Republican Party, found ways to take advantage of the situation.

The Republican Party presented itself as the only one that had a programme that was capable of returning to the country its lost status and place Portugal on the way of progress.

(Why does this sound so familiar?)

(Make Portugal great again?)

After a reluctance of the military to combat the nearly two thousand soldiers and sailors that rebelled between 3 and 4 October 1910, the Republic was proclaimed at 9 o’clock of the next day from the balcony of the Paços do Concelho in Lisbon.

After the revolution, a provisional government led by Teófilo Braga directed the fate of the country until the approval of the Constitution in 1911 that marked the beginning of the First Republic.

Above: Joaquim Teofilo Fernandes Braga (1843 – 1924)

Among other things, with the establishment of the republic, national symbols were changed: the national anthem and the flag.

The revolution produced some civil and religious liberties, although there were no advances in women’s rights and in workers’ rights, unlike what had happened in other European countries.

The First Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: Primeira República Portuguesa; officially: República Portuguesa, Portuguese Republic) spans a complex 16-year period in the history of Portugal, between the end of the period of constitutional monarchy marked by the 5 October 1910 revolution and the 28 May 1926 coup d’état.

The sixteen years of the First Republic saw nine presidents and 44 ministries and has been described as consisting of “continual anarchy, government corruption, rioting and pillage, assassinations, arbitrary imprisonment and religious persecution“.

The latter movement instituted a military dictatorship known as Ditadura Nacional (national dictatorship) that would be followed by the corporatist Estado Novo (new state) regime of António de Oliveira Salazar.

Above: António de Oliveria Salazar (1889 – 1970)

Kidnapped and driven off into darkness after Salazar snatched power in 1928, Portugal was absent from the Second World War and through most of the 20th century was economically isolated and politically smothered.

Portugal is rich with potential and a certain backwardness adds to the charm.

It is easy to fall in love with this fair land on this final edge of the world, though it could use a bit more self-confidence and a lot more marketing of itself and its heritage.)

Junquiero married Filomena Augusta da Silva Neves on 10 February 1880.

The couple had two children: Maria Isabel Guerra Junqueiro on 11 November 1880 and Júlia Guerra Junqueiro in 1881.

He died in Lisbon at the age of 72.

In 1940 Junqueiro’s daughter donated his estate in Porto that became the Guerra Junqueiro Museum.

Chronology of Guerra Junquiero:

1850: Born in Ligares, Freixo de Espada a Cinta

1864: The Book of Fourteen Years

1866: Studies theology at the University of Coimbra;

1867: Voices Without Echo

1868: Baptism of Love. Enrolls in the Faculty of Law of the University of Coimbra.

1873: Free Spain. Collaboration to The Leaf of João Penha. He earns a bachelor’s degree in law.

1874: The Death of D. João

1875: First issue of The Magic Lantern to which he collaborates

1878: He is appointed Secretary General of the Civil Government in Angra do Heroísmo.

1879: The Muse on Vacation and The Blackbird. Joins the Progressive Party. He is transferred from Angra do Heroísmo to Viana do Castelo and elected to the Chamber of Deputies.

1880: Married on 10 February to Filomena Augusta da Silva Neves. 11 November, their daughter Maria Isabel is born.

1881: Daughter Julia is born. Diagnosed with dementia, hospitalized in Porto.

1885: The Old Age of the Eternal Father. Creation of the “New Life” movement of which Junqueiro is a sympathizer.

1887: Second trip to Paris

1888: The group “Losers of Life” is formed. The Legitimate.

1889: His wife, Filomena Augusta Neves, dies whom he will mourn until the end of his days.

1890: Finis Patriae. Guerra Junqueiro is elected deputy by the Quelimane circle.

1895: Sells most of the artistic collections he had accumulated;

1896: The Fatherland. Departs for Paris.

1902: Prayer for Bread

1903: Lives in Vila do Conde.

1904: Prayer to the Light

1905: A visit to the Polytechnic Academy of Porto prompts him to settle in this city.

1908: He is candidate of the Republican Party for Porto.

1910: He is appointed Extraordinary Envoy and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Portuguese Republic to the Swiss Confederation in Berne

1914: Exonerated from the functions of Minister Plenipotentiary

1920: Sparse Prose

1923: He died on 7 July in Lisbon.

1966: His body is solemnly transferred from the Jerónimos Monastery where it had been interred to the National Pantheon of the Church of Santa Engrácia, Lisbon, in a ceremony held to honor other illustrious Portuguese figures.

Those are the facts as drily given by Wikipedia and Google, but who was the man?

How should we categorize him?

Should we?

Can we?

Was he a mere bureaucratic drone who dabbled in poetry?

Or a poet who dabbled in government work?

Did his writing incite a revolution or did it merely capture the spirit of the times?

As I sit in the sun my mind should be planning our travel itinerary for the day so to placate my wife upon her return.

But instead I think of Junqueiro and his Museum I won’t mention to the wife, already unhappy with the start of our first full day in Porto.

I think instead of the power of the printed word and of the impossibility, even through the written expression of a writer’s thoughts, of truly knowing another person.

Though it may be acknowledged that it is surely difficult for us to know a Portuguese poet long dead from nearly a century ago, it must also be acknowledged that even those we presently love remain unsolved mysteries to us.

“We are all patchwork, and so shapeless and diverse in composition that each bit, each moment, plays its own game.

And there is as much difference between us and ourselves as between us and others.” (Michel de Montaigne, Essais)

Above: Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592)

“Each of us is several, is many, is a profusion of selves.

So that the self who disdains his surroundings is not the same as the self who suffers or takes joy in them.

In the vast colony of our being, there are many species of people who think and feel in different ways.” (Fernando Pessoa, Livro do Desassossego)

Above: Fernando Pessoa (1888 – 1935)

I think of the mix of contradictory emotions that fill me anticipating my wife’s return, both eagerly awaiting and decidedly dreading her return.

I think of how each of us carries around inside ourselves whole worlds.

I am more than a sweaty balding head.

I am also a tear-softened soul.

I think of how much life I might still have before me, how open my future might be, how much could still happen, how much there might still be experienced.

Can anyone see beneath my mask that I am a mix of modesty and immodesty, of conformity and eccentricity, that within me lies a silent rage aimed at a pompous world, an unbending defiance against the world of show-offs whose only real accomplishment is their accidental connectivity to realms of power and prestige denied the average man?

I sit in the sun, uncertain of what to suggest next, unwilling to face my wife’s disapproval at what she will perceive to be laziness instead of confusion.

Perhaps we travel not to experience another world, but to flee from our own experience, simultaneously running to and from life.

Portugal is a land always in the shadows, a land of foggy fishing villages and tiny hamlets set deep in cork forests.

It is a land of mournful fado wailing and legendary sightings of the Virgin Mary.

Critics, most of them Portuguese, call Portugal the graveyard of ambition, the kingdom of mediocrity, where the national pastime is complaining and the ambitious leave.

As late as 2005, Portugal still had 13% of women who couldn’t read, less than 50% of children who made it to high school and was the lowest earner of the EU.

Porto, historically the country’s wine distribution centre, is said to be the hardest working part of Portugal:

“Lisbon plays, Porto pays, Coimbra prays.”

I want to visit the archbishop’s palace and the poet’s place, for I take great comfort from the calm of everything past.

So often I am alone with my thoughts, even when surrounded by a cacophony of chaotic conversations convulsing from a crowd.

My mind is sealed and my tongue falters in failing to express the vaulted thought.

My wife speaks and my ears hear and my heart listens, but my mind is my own, adrift on its own adventure, lost in its own odyssey.

I am reminded of my reading on the flight the day before, of the writing of Amadeu Prado, as invented by Swiss writer Pascal Mercier in his book Night Train to Lisbon:

“Of the thousand experiences we have, we find language for one experience at most and even this one merely by chance and without the care it deserves.

Buried under all the mute experiences are those unseen ones that give our life its form, its colour and its melody.

Then, when we turn to these treasures, as archaeologists of the soul, we discover how confusing they are.

The object of contemplation refuses to stand still, the words bounce off the experience and in the end, pure contradictions stand on the paper.”

What benefit is there in being the archaeologist of one’s self, to dig for buried experience?

“Given that we can live only a small part of what there is in us, what happens to the rest?”

The Wikipedia photo of Junquiero shows a man of intelligence and self-confidence and boldness.

Or is what I perceive only an observation of qualities I wish I possessed beneath the mask I wear?

Yet the contradiction that is a man’s character sometimes wonders could something be made different from my life, that there may be more to me than anyone knows.

In the centre of the city, in the centre of my life, I sit in the sun in the square of the cathedral.

I reflect how we live in an age rushing through a timeless universe only appreciated when contemplated quietly and calmly.

I think of the life of a man I never knew, a poet whose words I never read, who wrote in a language I never spoke.

Is Junqueiro only identifiable by what he did and the words he wrote?

Was there more to the man than anyone besides himself could ever possibly know?

“Is there a mystery under the surfaces of human action?

Or are human beings utterly what their obvious acts indicate?”

The words that Junquiero wrote, the words I have never read, are they expressions of eternally, essentially, the same things others have said before?

“Words are so horribly frayed and threadbare, worn out by being used millions of times.

Do they still have any meaning?

Naturally, the exchange of words functions.

People act on them.

They laugh and cry.

They go left or right.

The waiter brings the coffee or tea.

But that’s not what I want to ask.

The question is:

Are they still an expression of thoughts?

Or only effective sounds that drive people here and there because the worn grooves of babble incessantly flash?“

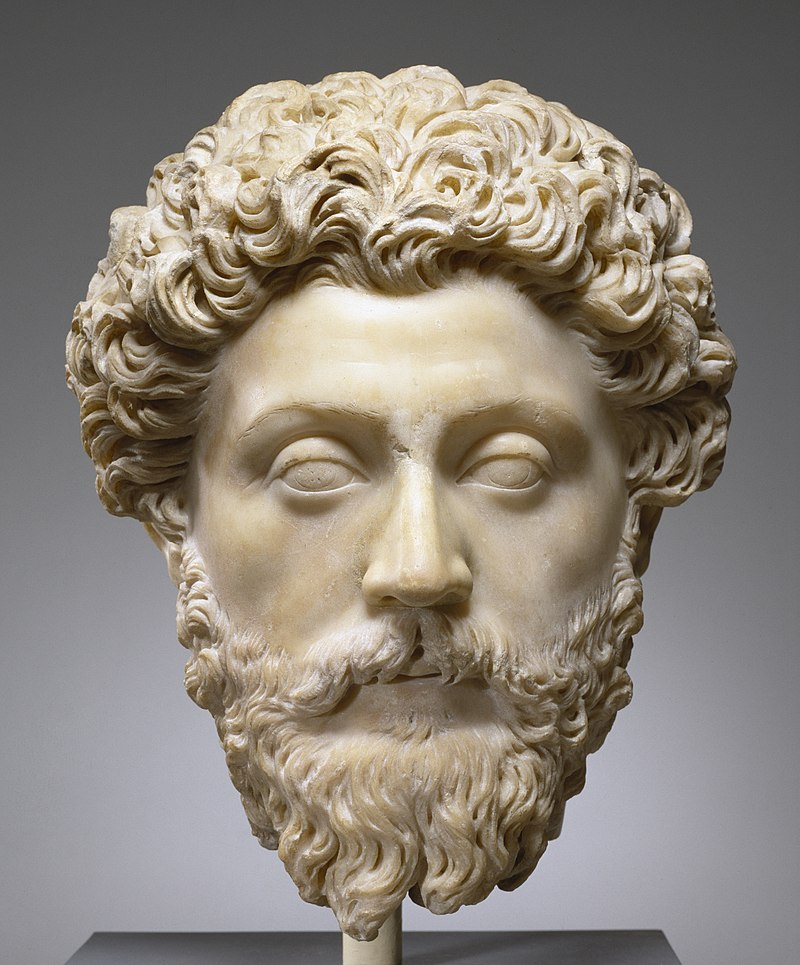

Perhaps I should follow the advice of Marcus Aurelius when he writes in his Meditations:

“Do wrong to thyself.

Do wrong to thyself, my soul, but later thou wilt no longer have the opportunity of respecting and honouring thyself.

For every man has but one life….

Those who do not observe the impulses of their own minds must of necessity be unhappy.“

Above: Marble bust of Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180)

She returns to me still sitting in the sun, with little progress on the planning made.

I imagine her thinking:

“What is the point of having a husband if he does not do what he is told?”

I imagine that she feels the weight of the world on her shoulders having a man about who is so completely useless at times.

I smile foolishly and say pointless words to defend my pointlessness.

I don’t mention Junquiero’s house and she never asks.

I also know I would be frustrated being in a museum whose signage I couldn’t read, despite the unfair expectation that a Portuguese museum have any other language besides Portuguese for a poet unknown outside of Portugal.

With a heavy sigh, she plans for us.

The morning has been shot to hell, so lunch across the Douro River in Gaia might inspire us.

Like the animal I am, I respond greedily to the prospect of food.

I know there is no excuse for my behaviour and no words to justify it, so I don’t bother trying.

Above: Vila Nova de Gaia

As I rise to my feet, carefully – I am just recovering from an accident where I broke both my arms – I think of Prado who never existed and Junquiero who no longer exists, then I focus on matters at hand.

The universe may be timeless but our vacation time is not.

But reading Mercier’s novel and learning of Junquiero’s life has inspired me.

I will ask when I can at random bookshops for the poems of Junquiero available in English translation.

Above: Livraria Lello, Porto

I know that the rhythm and subtlity of his poetry will be inadequately conveyed in translation, but I also know the painfully slow process of translating the original Portuguese into English I understand will somehow destroy the passion with which I started to read.

Nonetheless there is too little poetry in my life and even the muse of love has her limits and I must make amends for this deficiency.

I will return from the vacation and do the things I must do.

Work where and when I can.

Meet my obligations to others as best as I can.

I will seek no evil to see, no evil to hear, no evil to speak.

I remain a true husband, a good friend and loyal employee.

But my mind is my own and my words, as imprecise as they can be, will seek to speak my mind.

Perhaps through reading poetry I shall find the means to express myself.

I am my own archaeologist of my own self.

So much generated from simply sitting in the sun.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Lonely Planet Portugal / Rough Guide Portugal / Pocket Rough Guide Porto / Matthew Hancock, Xenophobe’s Guide to the Portuguese / A.H. de Oliveira Marques, A Very Short History of Portugal / Pascal Mercier, Night Train to Lisbon / Pedro Rodrigues, Porto and Northern Portugal: Journeys and Stories / Melissa Rossi, The Armchair Diplomat on Europe / Jürgen Strohmeier, Nordportugal