Landschlacht, Switzerland, Thursday 13 June 2019

In everyone’s life there are marker moments that separate who you were from who you are, as significant to the individual as BC and AD are to the Western calendar.

I have had my share of such moments in my own life.

Some are as obvious as scar tissue from accidents and operations.

Others are so subtle, so intimate, that they are as soft as a lover’s whisper in the night, and are no less important, nay, sometimes are far more important, than moments that clearly marked and marred you in the eyes of others.

Who we were, who we are and who we will become are often determined by what happens where we happen to be.

Certainly there are those who argue that we make our own destiny, that we create our own karma, but it is usually those who have known little hardship who wax poetically upon how they would have acted differently had they been in situations alien to their experience and understanding.

Their songs of self-praise usually play to the tune of “had I been there I would have….“.

“If I had been living in Germany during the Second World War I would have sheltered Jews.”

“If my country suffered a famine I would not remain.”

“If I lived in North Korea I would rise in revolt against the Kim dynasty.”

Truth be told, we may have the potential to freely make such brave decisions, but in the harsh chill of grim reality whether we would actually possess the needed courage and have the opportunity to successfully act is highly debatable.

If the consequence of helping others might lead to your death and the death of your loved ones, would you really risk everything to shelter those whom your government deems enemies of the state?

Would you be able to abandon your family to famine to save yourself?

Would you really defy your entire country’s military might to speak truth to power and say that what is being done in the name of nationalism is wrong for the nation?

It is easy to condemn the Germans of the National Socialist nightmare, the starving masses in Africa and India, the North Koreans under the Kims, and suggest that they were weak to allow themselves to be dominated by circumstances.

The self-righteous will argue with such platitudes like “Evil can only triumph when the good stay silent.“, but martyrdom’s recklessness is not easily embraced by everyone.

I was born in an age and have lived in places where I have never personally experienced the ravages of war firsthand.

I have known hunger and thirst but have never been hungry or thirsty to the brink of my own demise.

I have been fortunate to live in places where democracy, though imperfectly applied at times, dominated society rather than being sacrificed for security.

As a Canadian born in the 60s, who has never been in a military conflict, it is not easy for me to fully appreciate the difficulties of others that I myself have never experienced.

I count former refugees among my circle of friends, but I cannot claim to fully comprehend what they have endured or what they continue to quietly endure.

I have known those who chose not to be part of a military machine, despite the accusation of treason and disloyalty to their nation this suggests, because they chose not to act in the name of a nation that does not respect a person’s rights to choose not to kill their fellow human beings.

I love my homeland of Canada but I have never been called to defend her, have never had to choose between patriotism and humanity.

Canada’s leaders I have known may not have been great statesmen, but neither have they been as reprehensible as the leadership of other nations.

Can it be easy to be a true believer in Turkey under a tyrant like Erdogan?

Can it be easy to be a patriotic American with an amateur like Trump?

Can it be easy to call yourself a native of a nation whose government does things that disgust the conscience and stain the soil?

I grew up in Québec as an Anglophone Canadian and fortunately I have never been forced to choose between the province and the nation.

I now live in a nation that certainly isn’t a paradise for everyone within its boundaries, but its nationalism has not tested my resolve nor has it required the surrender of my conscience.

Oh, what a lucky man I have been!

Others have not been so fortunate.

I have visited places that have reminded me of my good fortune because of their contrast to that good fortune.

I have seen the ruins of the Berlin Wall and the grim reality of Cyprus’s Green Wall.

I have stood inside an underground tunnel between the two nations of South and North Korea, where two soldiers stand back-to-back 100 meters apart, and though they share the same language and the same culture, they are ordered to kill the other should the other speak.

I have seen cemeteries of fallen soldiers and the ravaged ruins that wars past have left behind.

I have seen the settings of holocaust and have witnessed racism firsthand.

I have heard the condemnation of others for the crime of being different.

How dare they love who they choose!

How dare they believe differently than we!

How dare they look not as we do!

How dare they exist!

Some places are scar marks on the conscience, wounds on the world.

Some places whisper the intimate injury of injustice and barely breathe the breeze of silent bravery against insurmountable obstacles.

I have not lived in a nation torn against itself where bully bastards hide their cruelty behind an ideological -ism that is a thinly disguised mask for their sadism.

What follows is the tale of one man who did, a man who lived in Belgrade, Serbia’s eternal city, and gave the world an image of the place’s perpetuity, the mirage of immortality….

A man’s whose life has made me consider my own….

Above: Belgrade

“Some folk tales have such universal appeal that we forget when and where we heard or read them, and they live on in our minds as memories of our personal experiences.

Such is, for example, the story of a young man who, wandering the Earth in pursuit of happiness, strayed onto a dangerous road, which led into an unknown direction.

To avoid losing his way, the young man marked the trees along the road with his hatchet, to help him find his way home.

That young man is the personification of general, eternal human destiny on one hand, there is a dangerous and uncertain road, and on the other, a great human need to not lose one’s way, to survive and to leave behind a legacy.

The signs we leave behind us might not avoid the fate of everything that is human: transience and oblivion.

Perhaps they will be passed by completely unnoticed?

Perhaps nobody will understand them?

And yet, they are necessary, just as it is natural and necessary for us humans to convey and reveal our thoughts to one another.

Even if those brief and unclear signs fail to spare us all wandering and temptation, they can alleviate them and, at least, be of help by convincing us that we are not alone in anything we experience, nor are we the first and only ones who have ever been in that position.”

(Ivo Andric, Signs by the Roadside)

Belgrade, Serbia, Thursday, 5 April 2018

The weather was worsening but my spirits were high.

I was on a mini-vacation, a separate holiday without my spouse, in a nation completely alien to me.

My good friend Nesha had graciously offered me the use of his apartment while he was away on business in Tara National Park, and so I was at liberty to come and go as I pleased without any obligations to anyone else but myself.

Above: Flag of Serbia

The day had started well.

I had visited Saint Sava Cathedral, the Nikola Tesla Museum and had serendipitiously stumbled upon a second-hand music store that sold Serbian music that my guidebooks had recommended I discover.

Above: Saint Sava Cathedral

Above: Nikola Tesla Museum

(For details of these, please see Canada Slim and….

- the Land of Long Life

- the Holy Field of Sparrows

- the Visionary

- the Current War

- the Man Who Invented the Future)

I was happy and so I would remain in the glorious week I spent in Belgrade and Nis.

I was learning so much!

(I still am.)

This journey I was making reminded me once again of just how ignorant I was (and am) of the world beyond my experience.

Before I began travelling the existence of life outside my senses remained naught more than rumours.

For example, I remember distinctly reading of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, but it was far removed from my life until I moved to Germany and later visited Berlin before I began to understand why this had been a significant event, a big deal.

I partially blame my ignorance on the circumstances of my life in Canada.

Canadian news dominates Canadian media, which isn’t surprising as we are more interested in that which is closest to our experience.

English-language literature remains more accessible in Anglophone parts of Canada than other languages and so that is mostly what we know.

Too few Canadians speak more than their native tongues of either English or French.

Only 10% of Canadians are truly bilingual and not necessarily in the other official Canadian language.

How sad it is that so many North Americans know so little of the outside world unless there is a military conflict or diplomatic gesture in which they are involved.

Send a Canadian soldier or the Canadian Prime Minister to Serbia then a few Canadians might make a curious effort to find Serbia on a world map.

Part of the problem and the reason why world peace and true unity eludes humanity is nationalism.

Why care about those who are not us?

If “us” is defined and limited by our national boundaries then how can we include “them” in our vision of fellow human beings?

Only the truly exceptional of that which is foreign grabs our momentary attention.

How can we understand one another if that which has shaped us is unknown by others and that which has shaped them is alien to us?

Can a Serbian truly understand a Canadian without knowing of Terry Fox and Wayne Gretzky, Robert W. Service and Margaret Atwood, Just for Laughs and Stephan Leacock, the Stanley Cup and the CBC, Sergeant Renfrew and Constable Benton Fraser?

Can a Canadian truly understand a Serbian without knowing of Novak Djokovic and Nemanja Vidic, the Turija sausage fest and the Novi Sad Exit, the Drina Regatta and the Nisville Jazz Festival, Emir Kusturica and Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac and Ivo Andric?

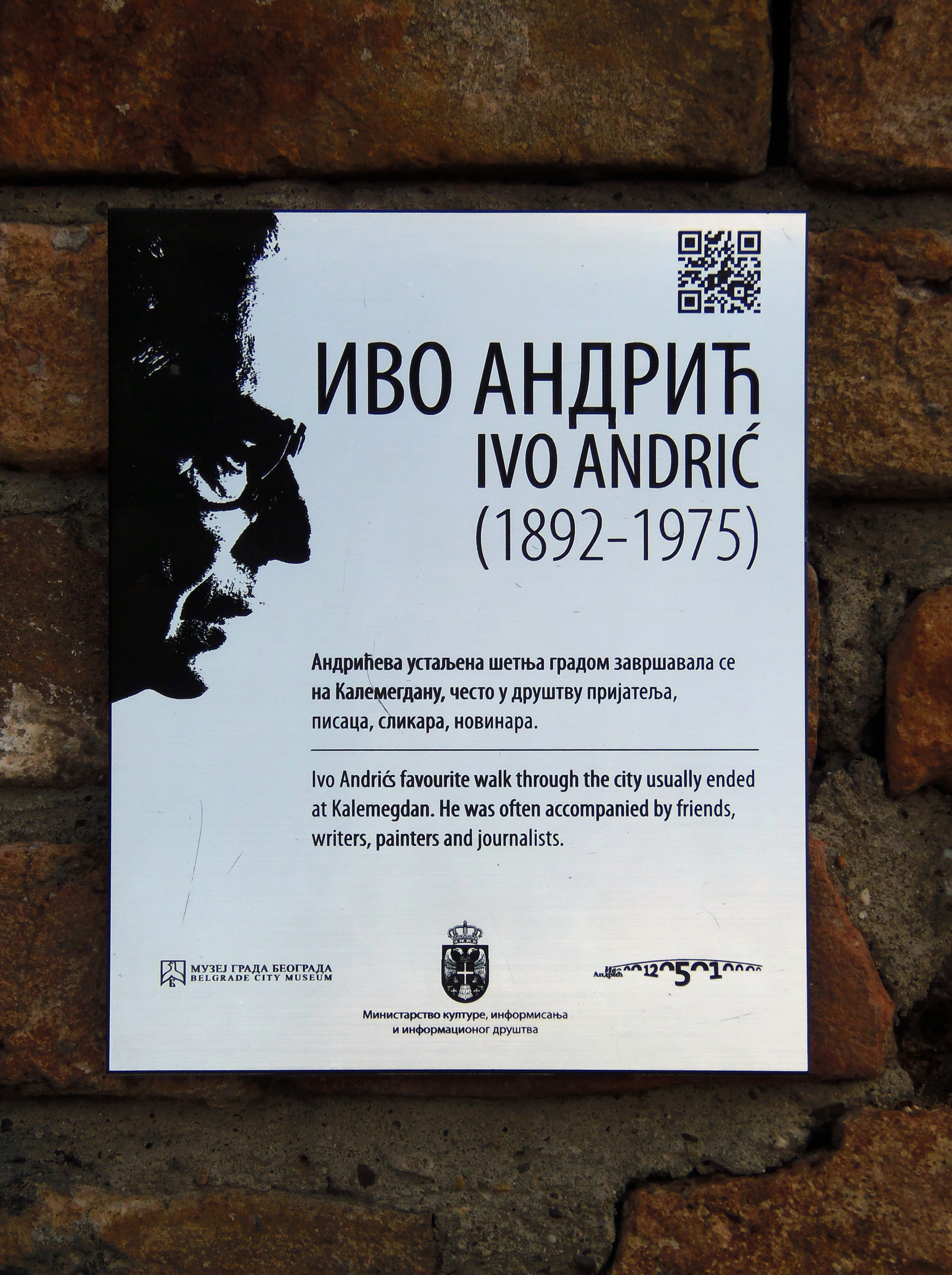

Above: Ivo Andric (1892 – 1975)

Possibly not.

I often think that it would be a good idea for the young to not only read what is / was written in their own tongue but as well to read Nobel Prize winning books translated from other languages.

It might even be a step towards world unity.

In my school years I was exposed to the writing of Nobel Prize winners Kipling, O’Neill, Buck, Eliot, Faulkner, Hemingway, Steinbeck and Bellow.

I had to travel to discover other Nobel laureates like Pamuk, Jelinek, Saramango, Neruda, Sartre, Camus, Marquez, Solzhenitsyn, Gidé, Mann and Andric by accident.

How much we miss when we stick to only our own!

How can we possibly have world peace when we are so ignorant of the world’s music, art and literature?

The street that runs beside Belgrade’s New Palace, now the seat of the President of Serbia, is named Andrićev venac (Andrić’s Crescent) in his honour.

It includes a life-sized statue of the writer.

The flat in which Andrić spent his final years has been turned into a museum.

Several of Serbia’s other major cities, such as Novi Sad and Kragujevac, have streets named after Andrić.

Streets in a number of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such as Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Tuzla, and Višegrad, also carry his name.

Andrić remains the only writer from the former Yugoslavia to have been awarded the Nobel Prize.

Given his use of the Ekavian dialect, and the fact that most of his novels and short stories were written in Belgrade, his works have become associated almost exclusively with Serbian literature.

(I asked my good friend Nesha whether Serbians can communicate with Bosnians and Croatians in a similar language, whether there was a Slavic tongue that unites the three.

He responded that it is all one Serbo-Croatian language with a difference in dialects that changes from region to region and divided by three different accents: Ekavica, Jekavic and Ijekavica

Even though Slovenians and Macedonians speak a little differently, they all understand and speak a Serbian-type speech.)

The Slavonic studies professor Bojan Aleksov characterizes Andrić as one of Serbian literature’s two central pillars, the other being Njegoš.

“The plasticity of his narrative,” Moravcevich writes, “the depth of his psychological insight, and the universality of his symbolism remain unsurpassed in all of Serbian literature.“

Though it has been said that the Serbian novel did not begin with Ivo Andric – (that honour lies with Borisav Stankovic (1867 – 1927) who explored the contradictions of man’s spiritual and sensory life in his 1910 work Bad Blood, the first Serbian novel to receive praise in its foreign translations) – it was Andric who took Serbian literature’s oral traditions and epic poetry and developed and perfected its narrative form.

To this day, Andric remains probably the most famous writer from former Yugoslavia.

And, sadly, I had never heard of him prior to this day.

A visit to the Memorial Museum of Ivo Andric (to give its official title) this day helped correct this imbalance….

By a decision of the Belgrade City Assembly, the property of Ivo Andric was heritage-listed and entrusted to the Belgrade City Museum immediately following Andric’s death on 13 March 1975.

It was an act meant to express the city’s deep respect for Andric as a writer and as a person.

In accordance with the practice common all over the world, Belgrade wished to preserve the original appearance of the writer’s apartment, surrounded by the Belgrade Old and New Courts and Pionirski Park, in its picturesque environment, to honour its famous citizen.

The establishment of this Memorial Museum also throws light on a very remarkable period in history encompassing the two world wars, as well as the post-war years, on which Andric left a strong personal and creative impact.

The holdings of Ivo Andric’s legacy chiefly consist of items found and inventoried at his apartment after his death – the underlying idea being to reflect the spirit and atmosphere of privacy and nobility surrounding him.

Andric’s personal library contains 3,373 items, along with archival materials, manuscripts, works of fine and applied arts, diplomas and decorations, 1,070 personal belongings and 803 photographs.

The apartment covers an area of 144 square metres (somewhat larger than my own apartment) and is divided into three units:

- the authentic interior, encompassing an entrance hall, a drawing room and Andric’s study

- the exhibition rooms, created by the adaptation of two bedrooms

- the curators’ and guides offices and the museum storerooms, occupying the former kitchen, the maid’s room, the bathroom and the lobby

It is both an unusual and a subtle combination of ambiguously private and unabasedly public, presenting an overview of Andric’s private life while depicting his vivid diplomatic, national, cultural and educational activities.

Ivo Andric was an unusual man who lived in unusual times, a life captured by a small apartment museum that like Andric himself is deceptively normal in appearance….

The original appearance and the function of the entrance hall have been preserved to a great extent.

The showcase with publications and souvenirs of the Belgrade City Museum is the only sign indicating that a visitor, though in residential premises, is actually in a Museum.

Already at the entrance to the Museum, an open bookshelf populated with thick volumes of Serbo-Croatian and foreign language dictionaries and encyclopedias and literary works in French, German and English, symbolizes Andric’s communication with European and world literature, history and philosophy as well as his own creative endeavours.

This is where the story of the writer begins to unfold….

Ivan Andrić was born in the village of Dolac, near Travnik, on 10 October 1892, while his mother, Katarina (née Pejić), was in the town visiting relatives.

Above: The house in which Andric was born, now a museum

(Travnik has a strong culture, mostly dating back to its time as the center of local government in the Ottoman Empire.

Travnik has a popular old town district however, which dates back to the period of Bosnian independence during the first half of the 15th century.

Numerous mosques and churches exist in the region, as do tombs of important historical figures and excellent examples of Ottoman architecture.

The city museum, built in 1950, is one of the more impressive cultural institutions in the region.

Travnik became famous by important persons who were born or lived in the city.

The most important of which are Ivo Andrić, Miroslav Ćiro Blažević (football coach of the Croatian national team, won third place 1998 in France), Josip Pejaković (actor), Seid Memić (pop singer) and Davor Džalto (artist and art historian, the youngest PhD in Germany and in the South-East European region).

Above: Images of Travnik

One of the main works of Ivo Andrić is the Bosnian Chronicle, depicting life in Travnik during the Napoleonic Wars and written during World War II.

In this work Travnik and its people – with their variety of ethnic and religious communities – are described with a mixture of affection and exasperation.

The Bosnian Tornjak, one of Bosnia’s two major dog breeds and national symbol, originated in the area, found around Mount Vlašić.)

Andrić’s parents were both Catholic Croats.

He was his parents’ only child.

(I too was raised as an only child.)

His father, Antun, was a struggling silversmith who resorted to working as a school janitor in Sarajevo, where he lived with his wife and infant son.

(The Museum disagrees with Wikipedia, describing Antun as a court attendant.)

At the age of 32, Antun died of tuberculosis, like most of his siblings.

Andrić was only two years old at the time.

(My mother died, of cancer, when I was three.)

Widowed and penniless, Andrić’s mother took him to Višegrad and placed him in the care of her sister-in-law Ana and brother-in-law Ivan Matković, a police officer at the border military police station.

The couple were financially stable but childless, so they agreed to look after the infant and brought him up as their own in their house on the bank of the Drina River.

Meanwhile, Andrić’s mother returned to Sarajevo seeking employment.

Andrić was raised in a country that had changed little since the Ottoman period despite being mandated to Austria-Hungary at the Congress of Berlin in 1878.

Eastern and Western culture intermingled in Bosnia to a far greater extent than anywhere else in the Balkan peninsula.

Having lived there from an early age, Andrić came to cherish Višegrad, calling it “my real home“.

Though it was a small provincial town (or kasaba), Višegrad proved to be an enduring source of inspiration.

It was a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional town, the predominant groups being Serbs (Orthodox Christians) and Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks).

Above: Images of Visegrad

(Like Andric, I was born elsewhere than the place I think of as home, though to Andric’s credit he lovingly wrote about his birthplace in The Travnik Chronicle.

I could imagine writing about St. Philippe, my childhood hometown, but I feel no intimate connection to St. Eustache, my birthplace, whatsoever, despite the latter having a larger claim to fame than the “blink-or-you’ll-miss-it” village of my youth.)

Above: St. Eustache City Hall

(My imagination plays with the notion of St. Philippe as “St. Jerusalem” and St. Eustache described during the Rebellion of 1837.)

Above: The Battle of St. Eustache, 14 December 1837

From an early age, Andrić closely observed the customs of the local people.

These customs, and the particularities of life in eastern Bosnia, would later be detailed in his works.

Andrić made his first friends in Višegrad, playing with them along the Drina River and the town’s famous Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge.

(The area was part of the medieval Serbian state of the Nemanjić dynasty.

It was part of the Grand Principality of Serbia under Stefan Nemanja (r. 1166–96).

In the Middle Ages, Dobrun was a place within the border area with Bosnia, on the road towards Višegrad.

After the death of Emperor Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–55), the region came under the rule of magnate Vojislav Vojinović, and then his nephew, župan (count) Nikola Altomanović.

The Dobrun Monastery was founded by župan Pribil and his family, some time before the 1370s.

Above: Dobrun Monastery

The area then came under the rule of the Kingdom of Bosnia, part of the estate of the Pavlović noble family.

The settlement of Višegrad is mentioned in 1407, but is starting to be more often mentioned after 1427.

In the period of 1433–37, a relatively short period, caravans crossed the settlement many times.

Many people from Višegrad worked for the Republic of Ragusa.

Srebrenica and Višegrad and its surroundings were again in Serbian hands in 1448 after Despot Đurađ Branković defeated Bosnian forces.

Above: Durad Brankovic (1377 – 1456)

According to Turkish sources, in 1454, Višegrad was conquered by the Ottoman Empire led by Osman Pasha.

It remained under the Ottoman rule until the Berlin Congress (1878), when Austria-Hungary took control of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge was built by the Ottoman architect and engineer Mimar Sinan for Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha.

Construction of the bridge took place between 1571 and 1577.

It still stands, and it is now a tourist attraction, after being inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site list.

The Bosnian Eastern Railway from Sarajevo to Uvac and Vardište was built through Višegrad during the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Construction of the line started in 1903.

It was completed in 1906, using the 760 mm (2 ft 5 15⁄16 in) track gauge.

With the cost of 75 million gold crowns, which approximately translates to 450 thousand gold crowns per kilometer, it was one of the most expensive railways in the world built by that time.

This part of the line was eventually extended to Belgrade in 1928.

Višegrad is today part of the narrow-gauge heritage railway Šargan Eight.

The area was a site of Partisan–German battles during World War II.

Višegrad is one of several towns along the River Drina in close proximity to the Serbian border.

The town was strategically important during the Bosnian War conflict.

A nearby hydroelectric dam provided electricity and also controlled the level of the River Drina, preventing flooding downstream areas.

The town is situated on the main road connecting Belgrade and Užice in Serbia with Goražde and Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a vital link for the Užice Corps of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) with the Uzamnica camp as well as other strategic locations implicated in the conflict.

On 6 April 1992, JNA artillery bombarded the town, in particular Bosniak-inhabited neighbourhoods and nearby villages.

Murat Šabanović and a group of Bosniak men took several local Serbs hostage and seized control of the hydroelectric dam, threatening to blow it up.

Water was released from the dam causing flooding to some houses and streets.

Eventually on 12 April, JNA commandos seized the dam.

The next day the JNA’s Užice Corps took control of Višegrad, positioning tanks and heavy artillery around the town.

The population that had fled the town during the crisis returned and the climate in the town remained relatively calm and stable during the later part of April and the first two weeks of May.

On 19 May 1992 the Užice Corps officially withdrew from the town and local Serb leaders established control over Višegrad and all municipal government offices.

Soon after, local Serbs, police and paramilitaries began one of the most notorious campaigns of ethnic cleansing in the conflict.

There was widespread looting and destruction of houses, and terrorizing of Bosniak civilians, with instances of rape, with a large number of Bosniaks killed in the town, with many bodies were dumped in the River Drina.

Men were detained at the barracks at Uzamnica, the Vilina Vlas Hotel and other sites in the area.

Vilina Vlas also served as a “brothel“, in which Bosniak women and girls (some not yet 14 years old), were brought to by police officers and paramilitary members (White Eagles and Arkan’s Tigers).

Above: Vilina Vlas Hotel today

Bosniaks detained at Uzamnica were subjected to inhumane conditions, including regular beatings, torture and strenuous forced labour.

Both of the town’s mosques were razed.

According to victims’ reports some 3,000 Bosniaks were murdered in Višegrad and its surroundings, including some 600 women and 119 children.

According to the Research and Documentation Center, at least 1,661 Bosniaks were killed/missing in Višegrad.

With the Dayton Agreement, which put an end to the war, Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided into two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, the latter which Višegrad became part of.

Above: Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Before the war, 63% of the town residents were Bosniak.

In 2009, only a handful of survivors had returned to what is now a predominantly Serb town.

On 5 August 2001, survivors of the massacre returned to Višegrad for the burial of 180 bodies exhumed from mass graves.

The exhumation lasted for two years and the bodies were found in 19 different mass graves.

The charges of mass rape were unapproved as the prosecutors failed to request them in time.

Cousins Milan Lukić and Sredoje Lukić were convicted on 20 July 2009, to life in prison and 30 years, respectively, for a 1992 killing spree of Muslims.

Above: Milan Lukic

The Mehmed Pasa Sokolovic Bridge was popularized by Andric in his novel The Bridge on the Drina.

A tourist site called Andricgrad (Andric Town) dedicated to Andric, is located near the Bridge.

Construction of Andrićgrad, also known as Kamengrad (Каменград, “Stonetown“) started on 28 June 2011, and was officially opened on 28 June 2014, on Vidovdan.)

Above: Main Street, Andricgrad

Throughout his life Andric was tied to Visegrad by pleasant reminiscences and bright memories of childhood.

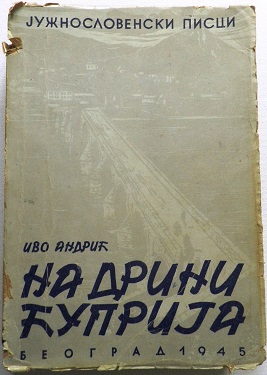

Above: First edition of The Bridge on the Drina (Serbian)

At the age of ten, he received a three-year scholarship from a Croat cultural group called Napredak (Progress) to study in Sarajevo.

In the autumn of 1902, he was registered at the Great Sarajevo Gymnasium (Serbo-Croatian: Velika Sarajevska gimnazija), the oldest secondary school in Bosnia.

While in Sarajevo, Andrić lived with his mother, who worked in a rug factory as a weaver.

(Today Sarajevo is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits.

The Sarajevo metropolitan area, is home to 555,210 inhabitants.

Nestled within the greater Sarajevo valley of Bosnia, it is surrounded by the Dinaric Alps and situated along the Miljacka River in the heart of the Balkans.

Sarajevo is the political, financial, social and cultural center of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a prominent center of culture in the Balkans, with its region-wide influence in entertainment, media, fashion, and the arts.

Due to its long and rich history of religious and cultural diversity, Sarajevo is sometimes called the “Jerusalem of Europe” or “Jerusalem of the Balkans“.

It is one of only a few major European cities which have a mosque, Catholic church, Orthodox church and synagogue in the same neighborhood.

A regional center in education, the city is home to the Balkans first institution of tertiary education in the form of an Islamic polytechnic called the Saraybosna Osmanlı Medrese, today part of the University of Sarajevo.

Although settlement in the area stretches back to prehistoric times, the modern city arose as an Ottoman stronghold in the 15th century.

Sarajevo has attracted international attention several times throughout its history.

In 1885, Sarajevo was the first city in Europe and the second city in the world to have a full-time electric tram network running through the city, following San Francisco….)

At the time, the city was overflowing with civil servants from all parts of Austria-Hungary, and thus many languages could be heard in its restaurants, cafés and on its streets.

Culturally, the city boasted a strong Germanic element, and the curriculum in educational institutions was designed to reflect this.

From a total of 83 teachers that worked at Andrić’s school over a twenty-year period, only three were natives of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“The teaching program,” biographer Celia Hawkesworth notes, “was devoted to producing dedicated supporters of the Habsburg Monarchy.”

Andrić disapproved.

“All that came at secondary school and university,” he wrote, “was rough, crude, automatic, without concern, faith, humanity, warmth or love.“

Andrić experienced difficulty in his studies, finding mathematics particularly challenging, and had to repeat the sixth grade.

For a time, he lost his scholarship due to poor grades.

Hawkesworth attributes Andrić’s initial lack of academic success at least partly to his alienation from most of his teachers.

Nonetheless, he excelled in languages, particularly Latin, Greek and German.

Although he initially showed substantial interest in natural sciences, he later began focusing on literature, likely under the influence of his two Croat instructors, writer and politician Đuro Šurmin and poet Tugomir Alaupović.

Of all his teachers in Sarajevo, Andrić liked Alaupović best and the two became lifelong friends.

Above: Tugomir Alaupovic (1870 – 1958)

Andrić felt he was destined to become a writer.

He began writing in secondary school, but received little encouragement from his mother.

He recalled that when he showed her one of his first works, she replied:

“Did you write this? What did you do that for?”

Andrić published his first poem “U sumrak” (At dusk) in 1911 in a journal called Bosanska vila (Bosnian Fairy), which promoted Serbo-Croat unity.

At the time, he was still a secondary school student.

His poems, essays, reviews, and translations appeared in journals such as Vihor (Whirlwind), Savremenik (The Contemporary), Hrvatski pokret (The Croatian Movement), and Književne novine (Literary News).

One of Andrić’s favorite literary forms was lyrical reflective prose, and many of his essays and shorter pieces are prose poems.

The historian Wayne S. Vucinich describes Andrić’s poetry from this period as “subjective and mostly melancholic“.

Andrić’s translations of August Strindberg’s novel Black Flag, Walt Whitman, and a number of Slovene authors also appeared around this time.

Above: Swedish writer August Strindberg (1849 – 1912)

In 1908, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, to the chagrin of South Slav nationalists like Andrić.

In late 1911, Andrić was elected the first president of the Serbo-Croat Progressive Movement (Serbo-Croatian: Srpsko-Hrvatska Napredna Organizacija; SHNO), a Sarajevo-based secret society that promoted unity and friendship between Serb and Croat youth and opposed the Austro-Hungarian occupation.

Its members were vehemently criticized by both Serb and Croat nationalists, who dismissed them as “traitors to their nations“.

Unfazed, Andrić continued agitating against the Austro-Hungarians.

On 28 February 1912, he spoke before a crowd of 100 student protesters at Sarajevo’s railway station, urging them to continue their demonstrations.

The Austro-Hungarian police later began harassing and prosecuting SHNO members.

Ten were expelled from their schools or penalized in some other way, though Andrić himself escaped punishment.

Andrić also joined the South Slav student movement known as Young Bosnia, becoming one of its most prominent members.

In 1912, Andrić registered at the University of Zagreb, having received a scholarship from an educational foundation in Sarajevo.

He enrolled in the department of mathematics and natural sciences because these were the only fields for which scholarships were offered, but was able to take some courses in Croatian literature.

(Today Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of Croatia.

It is located in the northwest of the country, along the Sava River, at the southern slopes of Mount Medvednica.

The climate of Zagreb is classified as an oceanic climate, but with significant continental influences and very closely bordering on a humid Continental climate as well as a humid subtropical climate.

Zagreb has four separate seasons.

Summers are warm, at the end of May the temperatures start rising and it is often pleasant with occasional thunderstorms.

Heatwaves can occur but are short-lived.

Temperatures rise above 30 °C (86 °F) on an average 14.6 days each summer.

Rainfall is abundant in the summertime and it continues to be in autumn as well.

Zagreb is Europe’s 9th wettest capital, behind Luxembourg and ahead of Brussels, Belgium.

Autumn in its early stages is mild with an increase of rainy days and precipitation as well as a steady temperature fall towards its end.

Morning fog is common from mid-October to January with northern city districts at the foothills of the Medvednica mountain as well as those along the Sava river being more prone to all-day fog accumulation.

Winters are cold with a precipitation decrease pattern.

Even though there is no discernible dry season, February is the driest month with 39 mm of precipitation.

On average there are 29 days with snowfall with first snow falling in early November.

Springs are generally mild and pleasant with frequent weather changes and are windier than other seasons.

Sometimes cold spells can occur, mostly in its early stages.

The average daily mean temperature in the winter is around 1 °C (34 °F) (from December to February) and the average temperature in the summer is 22.0 °C (71.6 °F).

Zagreb is a city with a rich history dating from the Roman times to the present day.

The oldest settlement located in the vicinity of the city was the Roman Andautonia, in today’s Ščitarjevo.

The name “Zagreb” is recorded in 1134, in reference to the foundation of the settlement at Kaptol in 1094.

Zagreb became a free royal town in 1242.

In 1851 Zagreb had its first mayor, Janko Kamauf.

After the 1880 Zagreb earthquake, up to the 1914 outbreak of World War I, development flourished and the town received the characteristic layout which it has today.

Zagreb still occasionally experiences earthquakes, due to the proximity of Žumberak-Medvednica fault zone.

It’s classified as an area of high seismic activity.

The area around Medvednica was the epicentre of the 1880 Zagreb earthquake (magnitude 6.3), and the area is known for occasional landslide threatening houses in the area.

The proximity of strong seismic sources presents a real danger of strong earthquakes.

Croatian Chief of Office of Emergency Management Pavle Kalinić stated Zagreb experiences around 400 earthquakes a year, most of them being imperceptible.

However, in case of a strong earthquake, it’s expected that 3,000 people would die and up to 15,000 would be wounded.

Above: Damage done to Zagreb Cathedral, 9 November 1880

The first horse-drawn tram was used in 1891.

The construction of the railway lines enabled the old suburbs to merge gradually into Donji Grad, characterised by a regular block pattern that prevails in Central European cities.

This bustling core hosts many imposing buildings, monuments, and parks as well as a multitude of museums, theatres and cinemas.

An electric power plant was built in 1907.

Since 1 January 1877, the Grič cannon is fired daily from the Lotrščak Tower on Grič to mark midday.

The first half of the 20th century saw a considerable expansion of Zagreb.

Before World War I, the city expanded and neighbourhoods like Stara Peščenica in the east and Črnomerec in the west were created.

The transport connections, concentration of industry, scientific, and research institutions and industrial tradition underlie its leading economic position in Croatia.

Zagreb is the seat of the central government, administrative bodies, and almost all government ministries.

Almost all of the largest Croatian companies, media, and scientific institutions have their headquarters in the city.

Zagreb is the most important transport hub in Croatia where Central Europe, the Mediterranean and Southeast Europe meet, making the Zagreb area the centre of the road, rail and air networks of Croatia.

It is a city known for its diverse economy, high quality of living, museums, sporting and entertainment events.

Its main branches of economy are high-tech industries and the service sector.

Zagreb is an important tourist centre, not only in terms of passengers travelling from the rest of Europe to the Adriatic Sea, but also as a travel destination itself.

It attracts close to a million visitors annually, mainly from Austria, Germany and Italy, and in recent years many tourists from the Far East (South Korea, Japan, China and India).

It has become an important tourist destination, not only in Croatia, but considering the whole region of southeastern Europe.

There are many interesting sights and happenings for tourists to attend in Zagreb, for example, the two statues of Saint George, one at the Republic of Croatia Square, the other at Kamenita vrata, where the image of Virgin Mary is said to be only thing that hasn’t burned in the 17th-century fire.

Also, there is an art installation starting in Bogovićeva street, called Nine Views.

Most people don’t know what the statue “Prizemljeno Sunce” (The Grounded Sun) is for, and just scrawl graffiti or signatures on it, but it’s actually the Sun scaled down, with many planets situated all over Zagreb in scale with the Sun.

There are also many festivals and events throughout the year, making Zagreb a year-round tourist destination.

The historical part of the city to the north of Ban Jelačić Square is composed of the Gornji Grad and Kaptol, a medieval urban complex of churches, palaces, museums, galleries and government buildings that are popular with tourists on sightseeing tours.

The historic district can be reached on foot, starting from Jelačić Square, the centre of Zagreb, or by a funicular on nearby Tomićeva Street.

Each Saturday, (April – September), on St. Mark’s Square in the Upper town, tourists can meet members of the Order of The Silver Dragon (Red Srebrnog Zmaja), who reenact famous historical conflicts between Gradec and Kaptol.

It’s a great opportunity for all visitors to take photographs of authentic and fully functional historical replicas of medieval armour.

Numerous shops, boutiques, store houses and shopping centres offer a variety of quality clothing.

There are about fourteen big shopping centres in Zagreb.

Zagreb’s offerings include crystal, china and ceramics, wicker or straw baskets, and top-quality Croatian wines and gastronomic products.

Notable Zagreb souvenirs are the tie or cravat, an accessory named after Croats who wore characteristic scarves around their necks in the Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century and the ball-point pen, a tool developed from the inventions by Slavoljub Eduard Penkala, an inventor and a citizen of Zagreb.

Many Zagreb restaurants offer various specialties of national and international cuisine.

Domestic products which deserve to be tasted include turkey, duck or goose with mlinci (a kind of pasta), štrukli (cottage cheese strudel), sir i vrhnje (cottage cheese with cream), kremšnite (custard slices in flaky pastry) and orehnjača (traditional walnut roll). )

Andrić was well received by South Slav nationalists in Zagreb and regularly participated in on-campus demonstrations.

This led to his being reprimanded by the university.

In 1913, after completing two semesters in Zagreb, Andrić transferred to the University of Vienna, where he resumed his studies.

(Vienna is the federal capital, largest city and one of nine states of Austria.

Vienna is Austria’s principal city, with a population of about 1.9 million (2.6 million within the metropolitan area, nearly one third of the country’s population), and its cultural, economic and political centre.

It is the 7th-largest city by population within city limits in the European Union.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, it was the largest German-speaking city in the world, and before the splitting of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I, the city had 2 million inhabitants.

Today, it has the second largest number of German speakers after Berlin.

Vienna is host to many major international organizations, including the United Nations and OPEC.

The city is located in the eastern part of Austria and is close to the borders of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary.

These regions work together in a European Centrope border region.

Along with nearby Bratislava, Vienna forms a metropolitan region with 3 million inhabitants.

In 2001, the city centre was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In July 2017 it was moved to the list of World Heritage in Danger.

Apart from being regarded as the City of Music because of its musical legacy, Vienna is also said to be “The City of Dreams” because it was home to the world’s first psychoanalyst – Sigmund Freud.

The city’s roots lie in early Celtic and Roman settlements that transformed into a Medieval and Baroque city, and then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It is well known for having played an essential role as a leading European music centre, from the great age of Viennese Classicism through the early part of the 20th century.

The historic centre of Vienna is rich in architectural ensembles, including Baroque castles and gardens, and the late-19th-century Ringstraße lined with grand buildings, monuments and parks.

Vienna is known for its high quality of life.

In a 2005 study of 127 world cities, the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked the city first (in a tie with Vancouver and San Francisco) for the world’s most liveable cities.

Between 2011 and 2015, Vienna was ranked second, behind Melbourne.

In 2018, it replaced Melbourne as the number one spot.

For ten consecutive years (2009–2019), the human-resource-consulting firm Mercer ranked Vienna first in its annual “Quality of Living” survey of hundreds of cities around the world.

Monocle’s 2015 “Quality of Life Survey” ranked Vienna second on a list of the top 25 cities in the world “to make a base within.”

The UN-Habitat classified Vienna as the most prosperous city in the world in 2012/2013.

The city was ranked 1st globally for its culture of innovation in 2007 and 2008, and sixth globally (out of 256 cities) in the 2014 Innovation Cities Index, which analyzed 162 indicators in covering three areas: culture, infrastructure, and markets.

Vienna regularly hosts urban planning conferences and is often used as a case study by urban planners.

Between 2005 and 2010, Vienna was the world’s number-one destination for international congresses and conventions.

It attracts over 6.8 million tourists a year.)

Above: Images of Vienna (Wien)

While in Vienna, Andric joined South Slav students in promoting the cause of Yugoslav unity and worked closely with two Yugoslav student societies, the Serbian cultural society Zora (Dawn) and the Croatian student club Zvonimir, which shared his views on “integral Yugoslavism” (the eventual assimilation of all South Slav cultures into one).

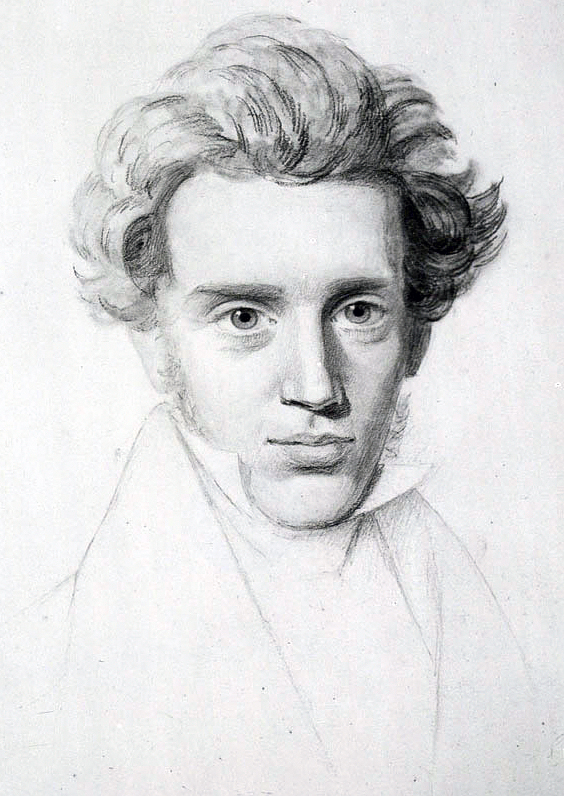

Andric became acquainted with Soren Kierkegaard’s book Either / Or, which would have a lasting influence on him.

Above: Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

Despite finding like-minded students in Vienna, the city’s climate took a toll on Andrić’s health.

He contracted tuberculosis and became seriously ill, then asked to leave Vienna on medical grounds and continue his studies elsewhere, though Hawkesworth believes he may actually have been taking part in a protest of South Slav students that were boycotting German-speaking universities and transferring to Slavic ones.

For a time, Andrić had considered transferring to a school in Russia but ultimately decided to complete his fourth semester at Jagiellonian University in Kraków.

Above: Logo of Jagiellonian University

(Kraków is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland.

Situated on the Vistula River, the city dates back to the 7th century.

Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 and has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, economic, cultural and artistic life.

Cited as one of Europe’s most beautiful cities, its Old Town was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The city has grown from a Stone Age settlement to Poland’s second most important city.

It began as a hamlet on Wawel Hill and was already being reported as a busy trading centre of Central Europe in 965.

With the establishment of new universities and cultural venues at the emergence of the Second Polish Republic in 1918 and throughout the 20th century, Kraków reaffirmed its role as a major national academic and artistic centre.

The city has a population of about 770,000, with approximately 8 million additional people living within a 100 km (62 mi) radius of its main square.

After the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany at the start of World War II, the newly defined Distrikt Krakau (Kraków District) became the capital of Germany’s General Government.

The Jewish population of the city was forced into a walled zone known as the Kraków Ghetto, from which they were sent to German extermination camps such as the nearby Auschwitz never to return, and the Nazi concentration camps like Płaszów.

In 1978, Karol Wojtyła, archbishop of Kraków, was elevated to the papacy as Pope John Paul II—the first Slavic pope ever and the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

Above: Pope John Paul II (1920 – 2005)

Also that year, UNESCO approved the first ever sites for its new World Heritage List, including the entire Old Town in inscribing Kraków’s Historic Centre.

Kraków is classified as a global city with the ranking of high sufficiency by GaWC.

Its extensive cultural heritage across the epochs of Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque architecture includes the Wawel Cathedral and the Royal Castle on the banks of the Vistula, the St. Mary’s Basilica, Saints Peter and Paul Church and the largest medieval market square in Europe, the Rynek Główny.

Kraków is home to Jagiellonian University, one of the oldest universities in the world and traditionally Poland’s most reputable institution of higher learning.

In 2000, Kraków was named European Capital of Culture.

In 2013 Kraków was officially approved as a UNESCO City of Literature.

The city hosted the World Youth Day in July 2016.)

Throughout his life Andric would feel that he owed much to the Polish excursion.

Andric met and mingled with painters Jovan Bijelic, Roman Petrovic and Peter Tijesic.

He transferred in early 1914 and continued to publish translations, poems and reviews.

Six poems written by Andric were included in the anthology Hrvatska Mlada Linka (Young Christian Lyricists).

In the words of literary critics:

“As unhappy as any artist. Ambitious. Sensitive. Briefly speaking, he has a future.”

Above: Flag of Poland

(This perspective has always made me wonder….

Must a man suffer before he can call himself an artist?)

Certainly, Andric lost his father and was separated from his mother in his childhood and the domination of his homeland by the Austrian-Hungarian Empire clearly bothered him, nonetheless Andric had had the distinct privilege of living and studying in four of the most beautiful and cultural cities that Eastern Europe offers.

Certainly, Andric would be plagued with ill health often during the course of his lifetime, but it would not be until the outbreak of war in 1914 that his, and Europe’s, suffering would truly begin….

(To be continued….)

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Lonely Planet Eastern Europe / Belgrade City Museum, Memorial Museum of Ivo Andric Guide / Komshe Travel Guides, Serbia in Your Hands / Top Travel Guides, Belgrade / Bradt Guides, Serbia / Aleksandar Diklic, Belgrade: The Eternal City / Ivo Andric, The Bridge on the Drina / Ivo Andric, Signs by the Roadside