Landschlacht, Switzerland, Friday 10 April 2020 (Lockdown Day #24)

At present, we live in interesting times, as the Chinese curse intended.

Stores are shuttered.

Church services suspended.

My sources of employment closed.

My movements outside of the apartment discouraged and travels outside the country denied.

For three weeks this has been normal life across this land and in many other nations around the globe.

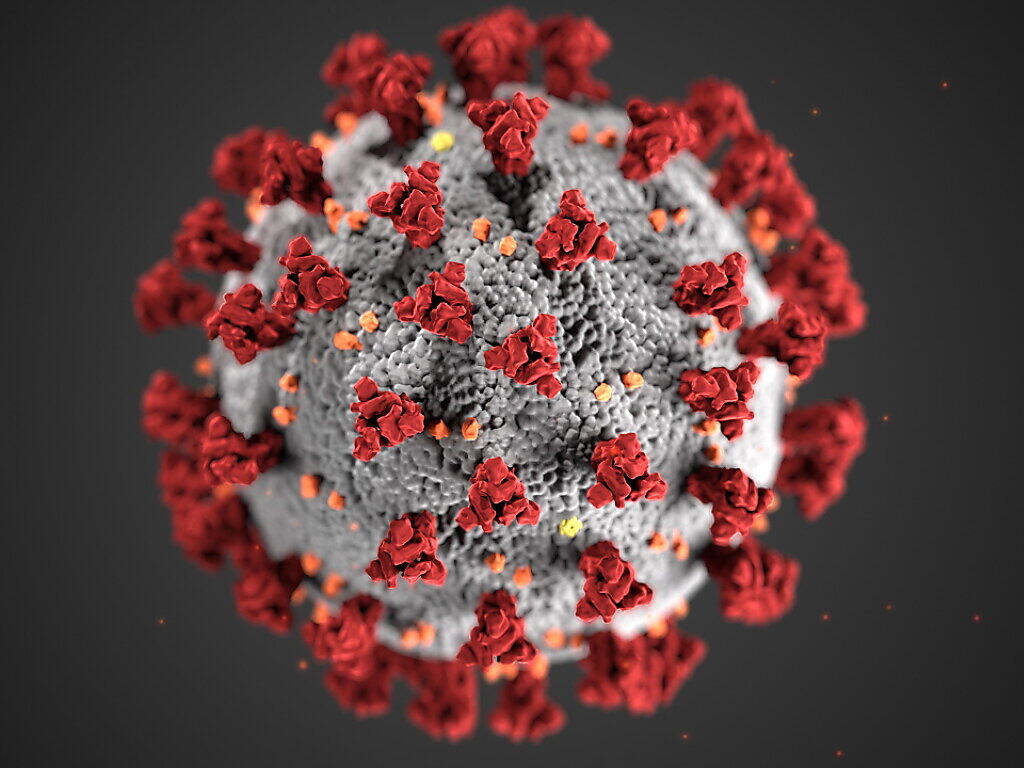

We struggle against a foe invisible and invincible and yet naively believe it can be conquered, for such is the indomitable spirit of man.

The Swiss government has extended the anti-corona virus restrictions in place for another week until 26 April, but it said it plans to examine an easing of measures at the end of the month.

The Covid-19 epidemic has spread widely in Switzerland but the speed at which it is spreading has slowed significantly in recent days, the government said on Wednesday.

The measures put in place to combat the virus are being followed well by the public and are having the desired effect, according to President Simonetta Sommaruga and Interior Minister Alain Berset.

“After four weeks the situation has evolved favourably,” Berset told a news conference.

“So, we’ve decided to extend the measures until 26 April and to proceed to the first loosening of some measures in some sectors.”

“We are on the right path, but we haven’t reached the finish line,” Sommaruga added.

A decision on the specific areas and measures to be relaxed will be presented on 16 April, the government said in a statement.

For the successful phase-out, certain requirements must be fulfilled, Berset explained.

These include a steady downward trend in number of new infections, hospitalisations and the death rate.

Above: Covid-19 in Switzerland – red: infected / green: recovered / black: dead – just a week prior to the lockdown

Switzerland remains one of the countries most affected by the corona virus, with more than 22,500 positive tests and more than 850 deaths in a population of 8.5 million.

Above: The number of corona virus (Covid-19) cases in Switzerland broken down by cantons as of 9 April 2020 – the darker the canton, the more cases therein

Berset said virus case figures were still rising, but in recent days there had been fewer daily infections and the number of people needing hospital treatment had stabilised.

“We are starting to see some light at the end of the tunnel, but discipline and patience is needed, especially during Easter when people must stay at home.

We must continue on this path for the next few weeks,” he declared.

The Interior Minister stressed that the population must continue to respect social distancing and hygiene measures, which are being well implemented and are working.

“We need to maintain these measures.

This is the condition by which we will be able to return to normal progressively,” he declared.

On 16 March, the government declared the corona virus pandemic an “extraordinary situation”, instituting a ban on all private and public events and ordering the closure of bars, restaurants, sports facilities and cultural spaces across the country.

Only businesses providing essential goods to the population – such as grocery stores, bakeries, pharmacies, banks and post offices – are allowed to remain open.

On the education front, schools are also closed nationwide.

Above: Bern, the capital of Switzerland, midday, midweek under lockdown

Switzerland could suffer its worst economic downturn on record, the government said on Wednesday, with the corona virus epidemic shrinking the economy by as much as 10.4% this year.

The scenario, far worse than the government’s previous forecast of a 1.5% contraction, would occur if there was a prolonged shutdown in Switzerland and as well as abroad, triggering bankruptcies and job cuts.

Economic Affairs Minister Guy Parmelin told reporters in Bern that the economy had been shaken by the virus and restrictions introduced to keep it from spreading.

He said nearly a third of the country’s workforce was on short-time work and unemployed numbers were on the rise.

“The scenarios are gloomy,” he told reporters.

“The health impact of the corona virus has been a concern for the Swiss government, but so has the effect on the economy.

It’s important we all do everything so that people in this country can work, despite the virus.”

Since I am not working I have a lot of leisure time on my hands.

It has often been said that a man’s character is best judged by not only what a job he does and how he performs in these duties, but as well a glimpse into who he really is can be observed by what he does with the time not devoted to an employer.

For myself, I try to take a walk outside for at least one hour everyday, occasionally I do the odd household duty or bit of decluttering when fits of ambition strike or the regular reminders from the wife become too much to tolerate, and I try to maintain a regular schedule of writing.

My formerly frantic work schedule and my travels here, there and everywhere have found me falling behind in the writing of my blogs, especially this one that focuses on travels done before the actual calendar year in which these posts are written down.

Now I have time to write and the time to read.

Of the latter, I, of course, try to keep au courant on current affairs both here in Switzerland and across the planet by reading news online and when possible from newspapers.

Though I am presently denied access to both bookstores and libraries, I do have in my possession my own burgeoning library that dominates our small apartment.

The guestroom bookshelves are burdened with works of fiction.

My study shelves hold books of and for teaching, history and politics, biography and autobiography, travel and travelogues, philosophy and psychology.

Of books I am drawn to buying and reading I find myself fascinated by the lives and observations of creative types, especially writers.

Certainly I seek the secrets of their success in an attempt to duplicate or at least emulate their methods and madness.

What writers do in their leisure hours often is the inspiration for their imaginative output.

I think of other activities some people practice during their private leisure hours, especially those who are young or young at heart.

Many activities revolve around the delightful duality of distraction and pleasure: physical intimacy with a nearby beloved, watching marathon episodes of regular series, and the ingestion of various substances that create excitement or ease the mind.

Here in Switzerland, access to alcohol and cannabis is not difficult for those determined to indulge themselves in this fashion, though for many there is little joy in indulging in these alone at home.

I will not judge others who do indulge, except to say it is my hope that they consider the effects of what they take into their bodies.

What was kept me on the straight and narrow has been a lack of curiosity and peer pressure to experiment with substances with which I have had no previous experience.

But, that having been said, though I lack the courage to experiment on myself, there has always been an idle curiosity in learning how such experiments have affected others.

Substances such as cocaine or heroin or others which cause distraction or delight have never piqued my curiosity, for the sole drugs with which I have any experience with – caffeine and alcohol – either wake me from slumber or cause me to sleep.

I have no desire to ingest something which may cause me to lose self-control (at least publicly).

Where my curiosity is piqued – though lack of courage keeps me from trying such things myself – is when I learn of substances that are said to induce creativity and expand imagination.

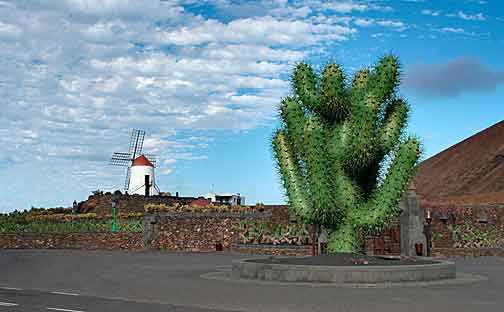

And it is this curiosity that makes me glad I only visited but don’t work at the Jardin de Cactus on the Canary Island of Lanzarote, for if I did I might be tempted to satisfy that curiosity…..

Guatiza, Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain, Monday 3 December 2018

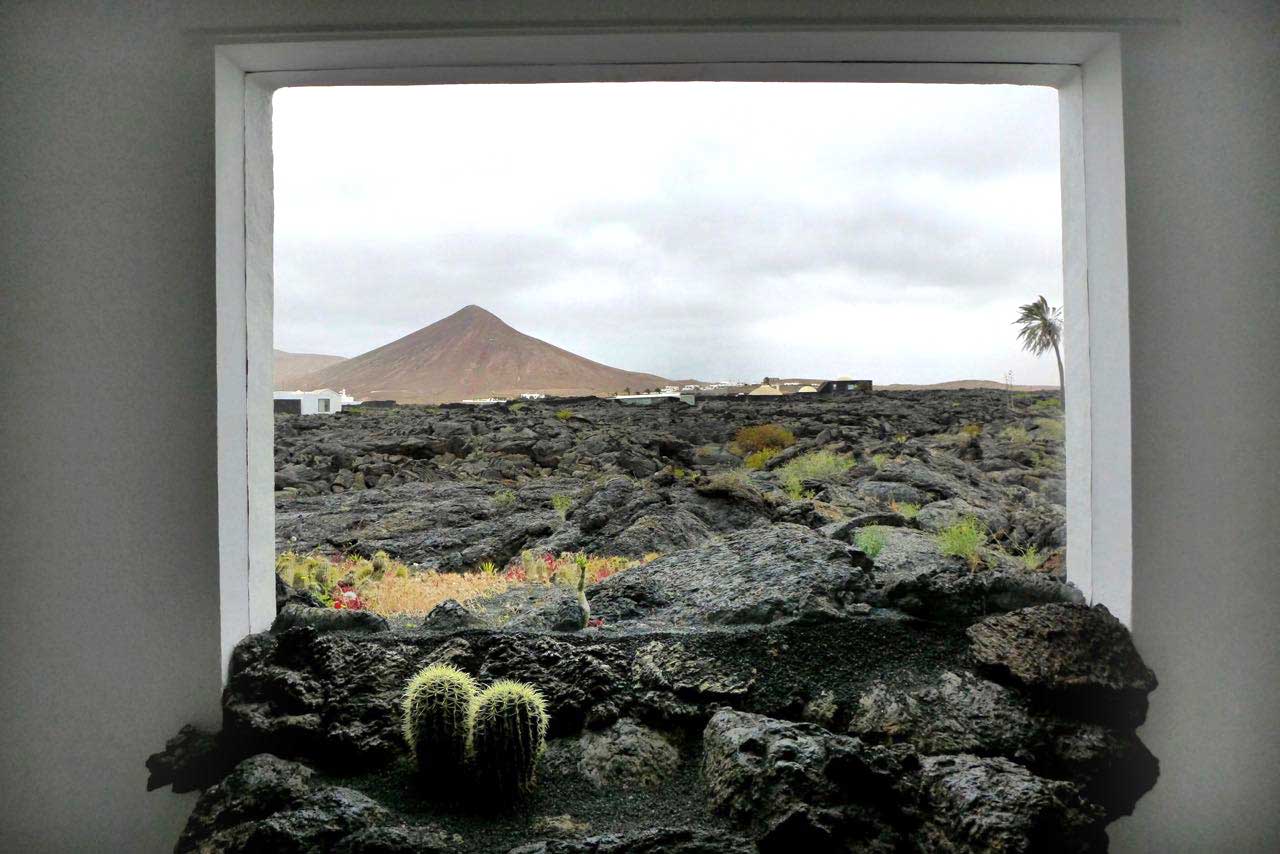

Guatiza is light and shade and purpose.

The visitor is inevitably surprised on arriving at Guatiza, located 2 km from the east coast of Lanzarote, 8 km east of the town Teguise and 14 km northeast of the island capital Arrecife, to find a village like any other but surrounded by a sea of green.

There are 612 species of ferns and flowering plants that grow spontaneously in Lanzarote.

Most of these plants are native.

Among them, 93 are endemic to the Canary Islands, while 20 are considered exclusive to Lanzarote.

Lanzarote’s endemic plant life may seem limited in comparison with the entire Canarian archipelago, in which there are 650 endemic species in about 7,200 square kilometres.

However, Lanzarote is rich and varied if compared to any European country, including Switzerland.

For example, 100 endemic species exist in France (560,000 square kilometres), 16 exist in Great Britain (250,000 square kilometres) and only six in Germany (350,000 square kilometres).

So, given this data, the importance of the islands’ flora is clear.

Vegetation on the Islands varies with the altitude and is conditioned by the constant flow of humid trade winds and the height of the island geography.

Lanzarote barely exceeds 600 metres above sea level at the summit of the oldest mountains.

Thus the winds generally pass over without releasing their moisture.

In contrast to the forests found on the higher Canary Islands, Lanzarote offers the best examples of the sub-desert habitats of the Canary Basal Floor, meaning that Lanzarote’s vegetative covering is rather poor, due not only to the arid climate but also to overgrazing.

Today, the decline of farming and grazing, as well as increased public awareness and the protection of large areas of territory, is enabling the slow recovery of profoundly transformed plant communities.

The local scrub thorn (commonly referred to as maleza, in Spanish) is the island’s most common plant formation, growing on the plains and low hills, as well as in undisturbed areas such as old cultivations.

There are five hundred different kinds of plants on the island, of which 17 species are endemic.

These plants have adapted to the relative scarcity of water in the same way as succulents.

They include the Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis), which is found in damper areas of the north, the Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis), ferns and wild olive trees (Olea europaea).

Laurisilva trees, which once covered the highest parts of Risco de Famara, are rarely found today.

After winter rainfall, the vegetation comes to a colourful bloom between February and March.

The vineyards of La Gería wine region, are a protected area.

Single vines are planted in pits 4–5 metres (13–16 feet) wide and 2–3 metres (6 feet 7 inches–9 feet 10 inches) deep, with small stone walls around each pit.

This agricultural technique is designed to harvest rainfall and overnight dew and to protect the plants from the winds.

What is not natural to Lanzarote, but found in Guatina in abundance, are cactus plants.

Guatina is a seemingly endless ocean of cactus whose large, oval proturbences blend into weird geometric forms.

At first glance, it seems that surely only some strange caprice of nature could have brought together in one same place such an enormous quantity of plants that normally elsewhere grow in defiant solitude.

But, no…..

This plantation of spines is the work of man and the plants are as well cared for as the children of man.

To be fair, man is assisted by nature now.

Draw close to the plants and observe them in detail, for then one can see that the cactus is covered by a myriad of tiny insects.

This creepy crawlers are “cochinillas“, a strange variety of parasite which, when dead, dried and ground, produces an extraordinary natural tint, cochineal, which is used in cosmetics and dyes and is renowned for its quality and resistence to external agents.

This exotic insect, originally from Mexico, arrived on Lanzarote in the 17th century and has since become a permanent resident, contributing significantly to the economy of Lanzarote.

As the cochinilla is an immigrant so too are Guatiza’s cacti.

Here is a flat, elongated place that you can find on a long avenue in the otherwise almost treeless Lanzarote.

For tourists, Guatiza is a pure transit point and is still entirely reserved for the Lanzarotenos.

Only the Jardín de Cactus at the northern end of the village, Manrique’s last creation in Lanzorote, attracts visitors in droves.

In the middle of the village, behind small stone walls, there are large prickly pear cactus fields, which were previously used extensively for the breeding of cochineal lice and which no longer tear down behind Mala.

Some dilapidated gofio mills set contrasts.

(A note about Lanzarote gastronomy:

Due to reasons of climate and customs, Lanzarote’e cuisine tends to be quite simple, based on elements common to the Island, like fish and local produce, seasoned with spices and special dressings.

Almost all Canarian dishes are served with an accompaniment known as gofio, which has been consumed for centuries.

Gofio is made from toasted grain flour.

Gofio amasado is made from mixing this flour with different ingredients, such as water, milk, broth, potatoes, honey, wine, etc. in a leather bag, pot or pan.

Most gofio is made with a mixture of wheat and barley grains, toasted and then milled.

Gofio de millo is also used: a coarse flour made from toasted corn.)

The pretty parish church of Santo Gusto stands out to the side of the main street.

The facade is covered with elegantly curved decorations made of brown lava stone.

In the high interior there are colored glass windows, a large altar and a heavy wooden gallery.

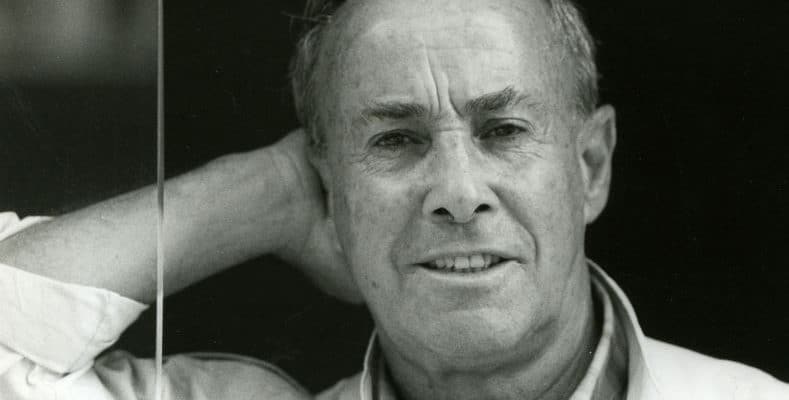

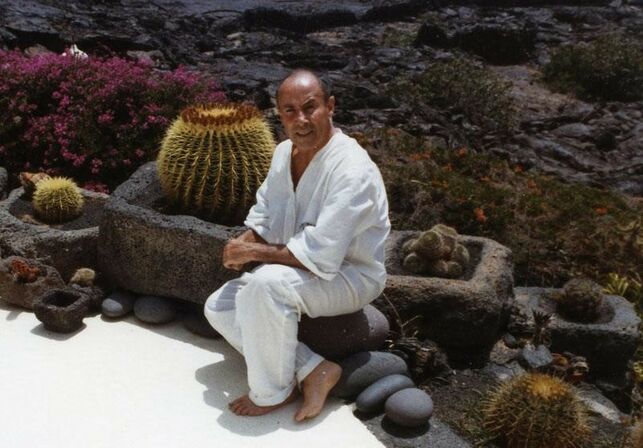

César Manrique (24 April 1919 – 25 September 1992) was a Spanish artist, sculptor, architect and activist from Lanzarote.

Manrique was born in Arrecife, Lanzarote.

He fought in the Spanish Civil War as a volunteer in the artillery unit on Franco’s side.

He attended the University of La Laguna to study architecture, but after two years he quit his studies.

He moved to Madrid in 1945 and received a scholarship for the Art School of San Fernando, where he graduated as a teacher of art and painting.

Between 1964 and 1966 he lived in New York City, where a grant from Nelson Rockefeller allowed him to rent his own studio.

He painted many works in New York, which were exhibited in the prestigious “Catherine Viviano” gallery.

Manrique returned to Lanzarote in 1966.

His legacy on the island includes:

- the art, culture and tourism centre at Jameos del Agua (1963 – 1987)

- his Volcano House, Taro de Tahiche (1968)

- the restaurant at the restored Castillo de San José at Arrecife (1976)

- the visitors center at the Timanfaya National Park (1971)

- his Palm Grove House at Haria (1986)

- the Mirador del Rio (1973)

- the Jardin de Cactus at Guatiza (1991)

He had a major influence on the planning regulations on Lanzarote following his recognition of its potential for tourism and lobbied successfully to encourage the sustainable development of the industry.

One aspect of this is the lack of high rise hotels on the island.

Those that are there are in generally keeping with the use of traditional colours in their exterior decoration.

As my wife and I drive around the Island we have made it one of our goals to see as much of Manrique’s legacy as we can during our six days here.

I find myself wondering what he would think of this day’s events.

I imagine he would have no great love for either Russia or America in terms of their attitudes towards Afghanistan, though he would probably be no fan of the Taliban either, especially in regards to their destruction of any cultural monuments that are not sufficiently reflective of Islam.

In 1999, Mullah Omar issued a decree protecting the Buddha statues at Bamyan, two 6th-century monumental statues of standing Buddhas carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan.

But in March 2001, the statues were destroyed by the Taliban of Mullah Omar, following a decree stating:

“All the statues around Afghanistan must be destroyed.”

Yahya Massoud, brother of the anti-Taliban and resistance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, recalls the following incident after the destruction of the Buddha statues at Bamyan:

It was the spring of 2001.

I was in Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley, together with my brother Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Afghan resistance against the Taliban, and Bismillah Khan, who currently serves as Afghanistan’s interior minister.

One of our commanders, Commandant Momin, wanted us to see 30 Taliban fighters who had been taken hostage after a gun battle.

My brother agreed to meet them.

I remember that his first question concerned the centuries-old Buddha statues that were dynamited by the Taliban in March of that year, shortly before our encounter.

Two Taliban combatants from Kandahar confidently responded that worshiping anything outside of Islam was unacceptable and that therefore these statues had to be destroyed.

My brother looked at them and said, this time in Pashto:

‘There are still many sun- worshippers in this country.

Will you also try to get rid of the sun and drop darkness over the Earth?’

I imagine that he would be on the side of Papuans desire for independence from Indonesia, though he might have approved of the violence used by either side of the ongoing conflict between Western New Guinea (Papua) and the Indonesian authorities.

I imagine he would be following with great interest the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference held from 2 to 16 December in Katowice, Poland.

A worldly wise and environmentally conscious artist like Manrique would probably have shared the opinion of many that Donald Trump was / is an idiot to withdraw America from the Paris Agreement, for the sole goal of dismantling and erasing any legacy that his predecessor Barack Obama had created.

The Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal is to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels; and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 °C, recognizing that this would substantially reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.

This should be done by peaking emissions as soon as possible, in order to “achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases” in the second half of the 21st century.

It also aims to increase the ability of parties to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change, and make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.”

Under the Paris Agreement, each country must determine, plan, and regularly report on the contribution that it undertakes to mitigate global warming.

No mechanism forces a country to set a specific emissions target by a specific date, but each target should go beyond previously set targets.

In June 2017, Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the agreement.

Under the agreement, the earliest effective date of withdrawal for the U.S. is November 2020, shortly before the end of President Trump’s 2016 term.

In practice, changes in United States policy that are contrary to the Paris Agreement have already been put in place.

Manrique would have followed yesterday’s Andalucia election results with avid fascination and especially the Constitutional Crisis just ended before we flew to Lanzarote.

The 2017–18 Spanish constitutional crisis, also known as the Catalan crisis, was a political conflict between the Government of Spain and the Generalitat de Catalunya under former President Carles Puigdemont—the government of the autonomous community of Catalonia until 28 October 2017—over the issue of Catalan independence.

It started after the law intending to allow the 2017 Catalan independence referendum was denounced by the Spanish government under Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and subsequently suspended by the Constitutional Court until it ruled on the issue.

Some international media outlets have described the events as “one of the worst political crises in modern Spanish history”.

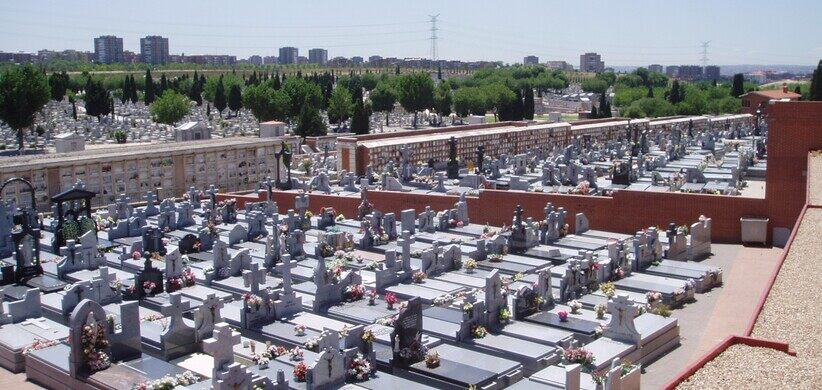

Above: Constitutional Court, Madrid

Though Manrique’s surviving the Spanish Civil War and the reign of France might have made his opinion as to the importance of this chapter in Spanish history differ from modern day commentators.

Puigdemont‘s government announced that neither central Spanish authorities nor the courts would halt their plans and that it intended to hold the vote anyway, sparking a legal backlash that quickly spread from the Spanish and Catalan governments to Catalan municipalities—as local mayors were urged by the Generalitat to provide logistical support and help for the electoral process to be carried out—as well as to the Constitutional Court, the High Court of Justice of Catalonia and state prosecutors.

By 15 September, as pro-Catalan independence parties began their referendum campaigns, the Spanish government had launched an all-out legal offensive to thwart the upcoming vote, including threats of a financial takeover of much of the Catalan budget, police seizing pro-referendum posters, pamphlets and leaflets which had been regarded as illegal and criminal investigations ordered on the over 700 local mayors who had publicly agreed to help stage the referendum.

Tensions between the two sides reached a critical point after Spanish police raided the Catalan government headquarters in Barcelona on 20 September, at the start of Operation Anubis, and arrested fourteen senior Catalan officials.

This led to protests outside the Catalan economy department which saw Civil Guard officers trapped inside the building for hours and several vehicles vandalized.

The referendum was eventually held, albeit without meeting minimum standards for elections and amid low turnout and police crackdown which at first seemed to have ended with hundreds injured, but was later rectified by the media since they were all deceived by the Catalan authorities, who had issued the Health Department to mix injured numbers with catered numbers, resulting in inflated figures.

Local hospitals reported figures of up to four injured people, two of them in critical state, one for a gum ball shot and the other one due to a heart attack.

Also the Spanish Ministry of Internal Affairs reported that up to 431 officers were injured, bruised or even bitten.

On 10 October, Puigdemont ambiguously declared and suspended independence during a speech in the Parliament of Catalonia, arguing his move was directed at entering talks with Spain.

The Spanish government required Puigdemont to clarify whether he had declared independence or not, to which it received no clear answer.

A further requirement was met with an implicit threat from the Generalitat that it would lift the suspension on the independence declaration if Spain “continued its repression“, in response to the imprisonment of the leaders of pro-independence Catalan National Assembly (ANC) and Òmnium Cultural, accused of sedition by the National Court because of their involvement in the 20 September events.

On 21 October, it was announced by Prime Minister Rajoy that Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution would be invoked, leading to direct rule over Catalonia by the Spanish government once approved by the Senate.

On 27 October, the Catalan parliament voted in a secret ballot to unilaterally declare independence from Spain, with some deputies boycotting a vote considered illegal for violating the decisions of the Constitutional Court of Spain, as the lawyers of the Parliament of Catalonia warned.

As a result, the government of Spain invoked the Constitution to remove the regional authorities and enforce direct rule the next day, with a regional election being subsequently called for 21 December 2017 to elect a new Parliament of Catalonia.

Puigdemont and part of his cabinet fled to Belgium after being ousted, as the Spanish Attorney General pressed for charges of sedition, rebellion and misuse of public funds against them.

We learned this morning that a far-right party in Spain broke new political ground Sunday after winning 12 seats in a regional election for the first time since the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975.

After the rejection of his budget, Sánchez called an early general election for 28 April 2019, making a television announcement in which he declared that “between doing nothing and continuing with the former budget and calling on Spaniards to have their say, I chose the second. Spain needs to keep advancing, progressing with tolerance, respect, moderation and common sense“.

Sánchez’s party the PSOE won the election, obtaining 29% of the vote which translated into 123 seats in the Congress of Deputies, well over the 85 seats and 23% share of the vote the party obtained in the 2016 election.

PSOE also won a majority in the Senate.

Whilst the PSOE were 53 seats short of the 176 seats needed for an outright majority in the Congress of Deputies, a three-way split in the centre-right vote assured that it was the only party that could realistically form a government.

On 6 June 2019, King Felipe VI, having previously held prospective meetings with the spokespeople of the political groups with representation in the new Congress of Deputies, formally proposed Sánchez as prospective Prime Minister.

Sánchez accepted the task of trying to form a government “with honor and responsibility“.

Several weeks of negotiations with the Podemos Party ended in an agreement that Sánchez would appoint several Podemos members to the Cabinet, although not the party’s leader Pablo Iglesias.

But in the final voting session, Podemos rejected the agreement and led Sánchez to try a second chance to be inaugurated in September.

Following the results of the November 2019 Spanish general election, on 12 November 2019, Pedro Sánchez and Iglesias announced a preliminary agreement between PSOE and Unidas Podemos to rule together creating the first coalition government of the Spanish democracy, for all purposes a minority coalition as it did not enjoy a qualified majority at the Lower House, thus needing further support or abstention from other parliamentary forces in order to get through.

On 7 January 2020, Pedro Sánchez earned a second mandate as Prime Minister after receiving a plurality of votes in the second round vote of his investiture at the Congress of Deputies.

He was then once again sworn in as Prime Minister by King Felipe on 8 January 2020.

Soon after, Sánchez proceeded to form a new cabinet with 22 ministers and four vice-presidencies, who assumed office on 13 January 2020.

Because of the corona virus pandemic, on 13 March 2020, Sánchez announced a declaration of the constitutional state of alarm in the nation for a period of 15 days, to become effective the following day after the approval of the Council of Ministers, becoming the second time in democratic history and the first time with this magnitude.

The following day imposed a nationwide lockdown, banning all trips that were not force majeure and announced it may intervene in companies to guarantee supplies.

The 2020 corona virus pandemic was confirmed to have spread to Spain on 31 January 2020, when a German tourist tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in La Gomera, Canary Islands.

By 24 February, Spain confirmed multiple cases related to the Italian cluster, originating from a medical doctor from Lombardy, Italy, who was on holiday in Tenerife.

Other cases involving individuals who visited Italy were also discovered in Peninsular Spain.

By 13 March, cases had been registered in all 50 provinces of the country.

A state of alarm and national lockdown was imposed on 14 March.

On 29 March it was announced that, beginning the following day, all non-essential workers were to stay home for the next 14 days.

By late March, the Community of Madrid has recorded the most cases and deaths in the country.

Medical professionals and those who live in retirement homes have experienced especially high infection rates.

On 25 March 2020, the death toll in Spain surpassed that reported in mainland China and only Italy had a higher death toll globally.

On 2 April, 950 people died of the virus in a 24-hour period—at the time, the most by any country in a single day.

The next day, Spain surpassed Italy in total cases and is now second only to the United States.

As of 7 April, Spain has the third largest number of confirmed cases per capita, behind Iceland and Luxembourg, not counting microstates.

As of 9 April 2020, there have been 153,222 confirmed cases with 52,165 recoveries and 15,447 deaths in Spain.

The actual number of cases, however, is likely to be much higher, as many people with only mild or no symptoms are unlikely to have been tested.

The number of deceased is also believed to be an underestimate due to lack of testing and reporting, perhaps by as much as 10,000 according to excess mortality analysis.

During the pandemic, the healthcare system is using triage, denying resources to elderly patients.

Furthermore, infected elderly people living in nursing homes are being rejected by hospitals.

As of 7 April 2020, the Canary Islands have 1,824 confirmed Covina-19 cases.

Of these, 730 have been hospitalized, 140 in intensive care units, 92 have died, 359 have recovered.

Had Manrique been alive in 2018 he would have been 98 years old but he was killed in a car crash in 1992.

Had he been alive in 2020, chances are strong that at his advanced age he would have been vulnerable to Covina-19 as many of the elderly are.)

As we wander amongst the cacti, row after row, terrase level atop terrase Level, I find myself wondering why Manrique chose such a plant not native to the Island.

From Manrique’s writings it is certainly clear of how he felt about nature:

“Nature’s freedom has modelled my freedom in life, as an artist and as a man.

I want to extract harmony from the Earth to unify it with my feeling for art.

We have to create a new universal conscience in order to try and save the natural environment from the encroachment of human egoism, capable only of seeing the benefits of economic interests in the thorough destruction of nature.

We must find time to enjoy contact with Mother Nature.

She teaches us to behold her awe-inspiring aesthetics and creativity.

We should learn from and use our own environment to create, without resorting to any preconceived ideas.

This is the fundamental factor which has strengthened Lanzarote’s personality.

We did not have to copy anybody.

Lanzarote taught us this other alternative.

The only thing I aim to achieve is to fuse with nature, so that she may be able to help me and I may be able to help her.

I wonder if Switzerland’s natural beauty was an inspiration for the feelings he harboured towards the environment, for Manrique, in 1959, participated in collective exhibitions devoted to young Spanish painters in ten cities, including Fribourg and Basel.

Manrique painted an oil canvas painting entitled Mexico in 1969.

The Fundación César Manrique is based in Taro de Tahiche in the former residence of the artist.

The property really reflects the concept that Manrique created, a wonderful mixture of the natural environment and modern design.

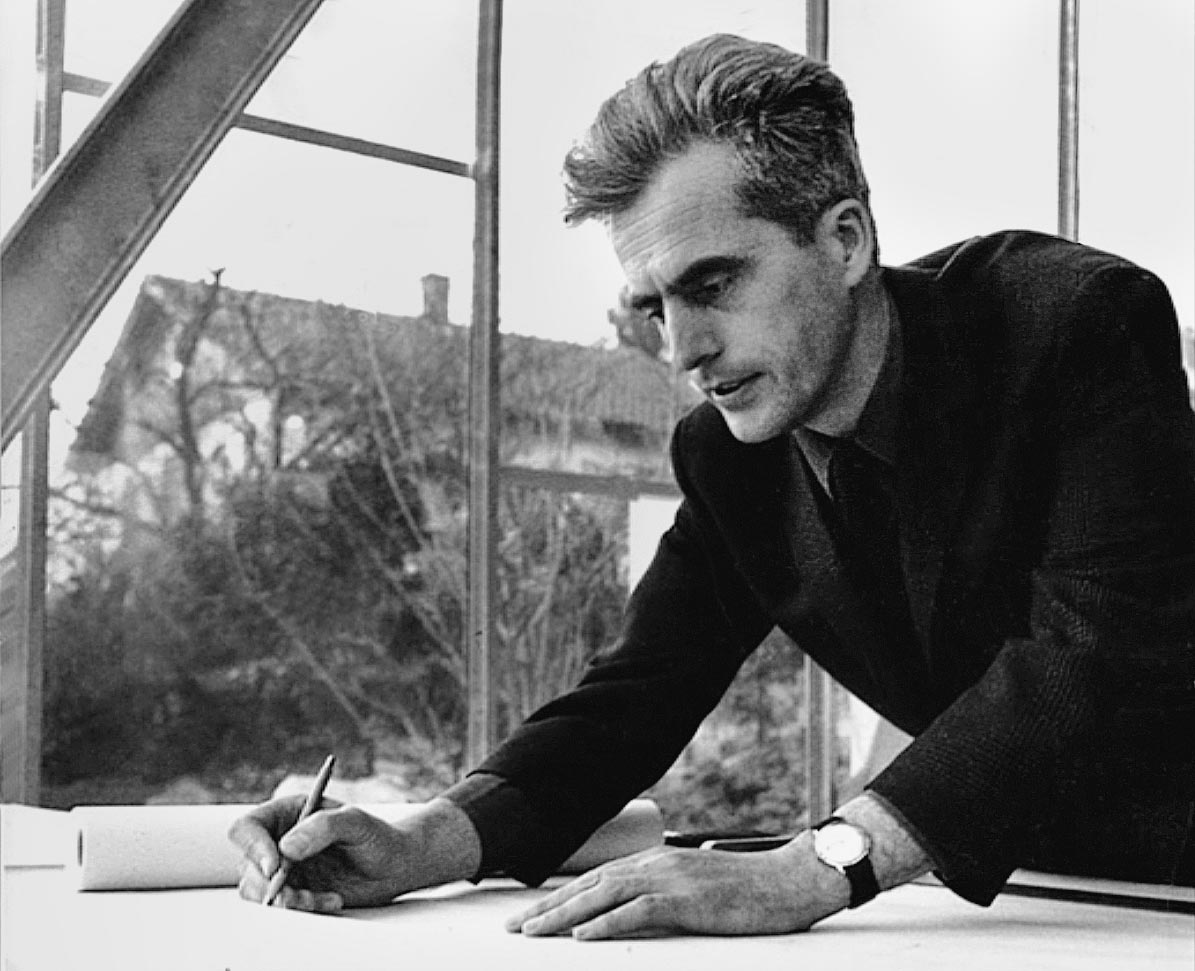

Architect Frei Otto said of the Taro de Tahiche property:

“It is something special.

It reminds me of similar houses in Pedregal, Mexico.….”

Did Manrique visit Mexico?

Jardines del Pedregal (Rocky Gardens) or simply El Pedregal (full name: El Pedregal de San Angel) is an upscale residential colonia (neighborhood) in southern Mexico City hosting some of the richest families of Mexico.

It is also known as the home to the biggest mansion in the city.

Its borders are San Jerónimo Avenue and Ciudad Universitaria at the north, Insurgentes Avenue at the east and Periférico at south and west.

Its 1,250 acres (5.1 km2) were the major real estate project undertaken by Mexican modernist architect Luis Barragán.

When it was originally developed, in the mid-1940s in the lava fields of the Pedregal de San Ángel, it was probably the biggest urban development the city had seen.

The first house to be built here was the studio/home of architect Max Cetto.

The area has changed a lot since its original development but even as its modernist spirit and its original elements of ecosystem protection are gone critics have described its original development, the houses and gardens as a turning point in Mexican architecture.

Some of the old modernist houses have been catalogued as part of Mexico’s national patrimony.

The Pedregal lava fields were formed by the eruption of the Xitle volcano around 5000 BC, but there are documented eruptions until 400 AD.

The area near what is currently el Pedregal, called Cuicuilco, has been inhabited since 1700 BC.

Around 300 BC, the area contained what was probably the biggest city in the Valley of Mexico at the time.

Its importance started to decline around 100 BC and was completely empty by 400.

In the mid-1940s Luis Barragán began a project to urbanize the area and protect its ecosystem.

Barragán had the idea of developing El Pedregal promoting the harmony between architecture and landscape.

The first structures built on the site were the Plaza de las Fuentes, or Plaza of the Fountains, the demonstration gardens and demonstration houses by Barragán and Max Cetto.

Other famous architects that contributed to the development of Pedregal include: Francisco Artigas, Enrique Castañeda Tamborrell, José María Buendía, Antonio Attolini, Fernando Ponce Pino, Óscar Urrutia and Manuel Rosen.

For sculptural effect, rocks and vegetation were left largely in place, crevices between the lava formations were cleared as paths, and at several points, rough-cut stairways passed between rock terraces.

These stairways led to pools or fountains of various configurations, or to small patches of flat ground, where loam was brought in and lawns planted.

The smooth surfaces of the lawns and pools provided contrast to the jagged rocks, while fountains lent kinetic and aural elements to the mix.

The botanical garden at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) was founded in 1959 by a pair of botanists who wanted to create a space on campus dedicated entirely to the study and preservation of Mexico’s extraordinarily diverse flora.

Mexico is one of the most biodiverse countries in terms of its vegetation, home to more plant species than the US and Canada combined.

It also has the highest diversity of cactus plants in the world at an estimated 800 recorded species.

Historically, Mexico City is no stranger to botanical gardens.

The Aztec emperors kept numerous planted areas of ornamental, medicinal, and edible plants collected from all over the empire, long before the arrival of the Spanish.

The UNAM botanical garden continues this tradition, but with an added focus on conservation, environmental education, and advancing botanical and taxonomic science.

Fittingly, the collection has an enormous collection of endemic cacti, and many of the species on display here are highly endangered due to habitat destruction, overexploitation, and climate change.

But the gardens contain much more than just cacti.

There are areas planted with beautiful ornamental plants, a medicinal plant garden with species used traditionally by indigenous communities, an orchidarium, and many waterlily pools also home to plump koi carp and languid turtles.

The green spaces here make for an ideal place to come and relax away from the chaos of Mexico City life.

The garden is also notable for being built on and around strange volcanic rock formations that were formed by lava flows during the Xitle volcanic eruption, which destroyed the nearby Cuilcuilca civilization in Mexico’s distant past.

As such, many of the gardens’ meandering footpaths pass under, over, and around naturally formed grottoes, ponds, mini waterfalls, and rockeries, making for a unique experience.

Wildlife can be seen here, too, and it is a particularly good area to spot birds such as woodpeckers, owls, orioles, and hummingbirds.

Also found here are reptiles like rattlesnakes, milksnakes, and lizards, numerous species of butterflies, and even the rare Pedregal tarantula, an endemic species that is found only in this small area of Mexico City.

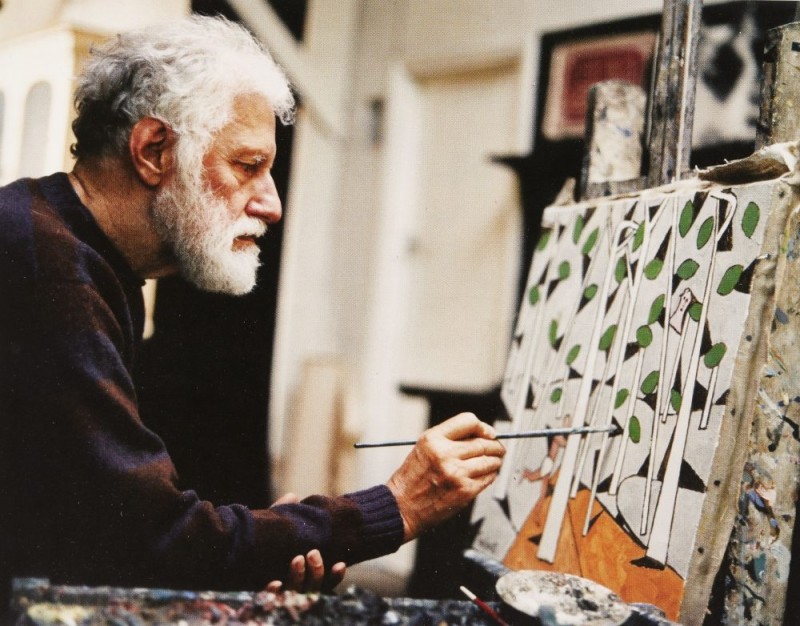

The Jardín de Cactus, situated in the Lanzarote village of Guatiza, in a former quarry where volcanic sand (picón) was extracted to spread on cultivated areas to retain moisture.

Prickly pears are grown in the area for the production of cochineal.

The cactus garden was created in 1991, the last project of César Manrique.

The botanist Estanislao González Ferrer was responsible for the selection and planting of the specimens.

Estanislao González Ferrer (1930- 1990) was a Spanish botanist, expert in the flora of the Canary Island of Lanzarote.

A flower endemic to the island was found by his disciples, with whom he used to go out to do field work studying and documenting species in situ, and named in his honor: the Helianthemum gonzalez ferreri.

Estanislao González Ferrer was a Lanzarote native especially involved in the conservation of nature and the historical heritage of his native island, specializing in botany.

In his day he was one of the people commissioned by the Arrecife City Council to form a previous commission for the creation of the city’s museum and among his best-known botanical contributions is his participation as botanical manager in the creation of the well-known Cactus Garden of Lanzarote by César Manrique.

A cactus (plural cacti, cactuses, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1,750 known species of the order Caryophyllales.

The word “cactus” derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Greek κάκτος, kaktos, a name originally used by Theophrastus for a spiny plant whose identity is now not certain.

Cacti occur in a wide range of shapes and sizes.

Above: Various Cactaceae 1-Nopalea coccinellifera 2-Cephalocereus senilis 3-Cereus giganteus 4-Mammillaria longimamma 5-Rhipsalis paradoxa 6-Echinocactus longihamatus 7-Echinopsis oxygona 8-Cereus grandiflorus 9-Echinocereus pectinatus 10-Leuchtenbergia principis 11-Phyllocactus ackermanni 12-Melocactus communis

Most cacti live in habitats subject to at least some drought.

Many live in extremely dry environments, even being found in the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth.

Cacti show many adaptations to conserve water.

Almost all cacti are succulents, meaning they have thickened, fleshy parts adapted to store water.

Unlike many other succulents, the stem is the only part of most cacti where this vital process takes place.

Most species of cacti have lost true leaves, retaining only spines, which are highly modified leaves.

As well as defending against herbivores, spines help prevent water loss by reducing air flow close to the cactus and providing some shade.

In the absence of leaves, enlarged stems carry out photosynthesis.

Cacti are native to the Americas, ranging from Patagonia in the south to parts of western Canada in the north—except for Rhipsalis baccifera, which also grows in Africa and Sri Lanka.

Cactus spines are produced from specialized structures called areoles, a kind of highly reduced branch.

Areoles are an identifying feature of cacti.

As well as spines, areoles give rise to flowers, which are usually tubular and multi-petaled.

Many cacti have short growing seasons and long dormancies, and are able to react quickly to any rainfall, helped by an extensive but relatively shallow root system that quickly absorbs any water reaching the ground surface.

Cactus stems are often ribbed or fluted, which allows them to expand and contract easily for quick water absorption after rain, followed by long drought periods.

Like other succulent plants, most cacti employ a special mechanism called “crassulacean acid metabolism” (CAM) as part of photosynthesis.

Above: A pineapple, an example of a CAM plant

Transpiration, during which carbon dioxide enters the plant and water escapes, does not take place during the day at the same time as photosynthesis, but instead occurs at night.

The plant stores the carbon dioxide it takes in as malic acid, retaining it until daylight returns, and only then using it in photosynthesis.

Because transpiration takes place during the cooler, more humid night hours, water loss is significantly reduced.

Many smaller cacti have globe-shaped stems, combining the highest possible volume for water storage, with the lowest possible surface area for water loss from transpiration.

Above: Overview of transpiration

- Water is passively transported into the roots and then into the xylem.

- The forces of cohesion and adhesion cause the water molecules to form a column in the xylem.

- Water moves from the xylem into the mesophyll cells, evaporates from their surfaces and leaves the plant by diffusion through the stomata

The tallest free-standing cactus is Pachycereus pringlei, with a maximum recorded height of 19.2 m (63 ft), and the smallest is Blossfeldia liliputiana, only about 1 cm (0.4 in) in diameter at maturity.

A fully grown saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) is said to be able to absorb as much as 200 US gallons (760 litres; 170 Impirical gallons) of water during a rainstorm.

A few species differ significantly in appearance from most of the family.

At least superficially, plants of the genus Pereskia resemble other trees and shrubs growing around them.

They have persistent leaves, and when older, bark-covered stems.

Their areoles identify them as cacti, and in spite of their appearance, they, too, have many adaptations for water conservation.

Pereskia is considered close to the ancestral species from which all cacti evolved.

In tropical regions, other cacti grow as forest climbers and epiphytes (plants that grow on trees).

Their stems are typically flattened, almost leaf-like in appearance, with fewer or even no spines, such as the well-known Christmas cactus or Thanksgiving cactus (in the genus Schlumbergera).

Cacti have a variety of uses:

Many species are used as ornamental plants, others are grown for fodder or forage, and others for food (particularly their fruit).

Cochineal is the product of an insect that lives on some cacti.

As of March 2012, there was still controversy as to the precise dates when humans first entered those areas of the New World where cacti are commonly found, and hence when they might first have used them.

An archaeological site in Chile has been dated to around 15,000 years ago, suggesting cacti would have been encountered before then.

Early evidence of the use of cacti includes cave paintings in the Serra da Capivara in Brazil, and seeds found in ancient middens (waste dumps) in Mexico and Peru, with dates estimated at 9,000 years ago.

Hunter-gatherers likely collected cactus fruits in the wild and brought them back to their camps.

It is not known when cacti were first cultivated.

Opuntias (prickly pears) were used for a variety of purposes by the Aztecs, whose empire, lasting from the 14th to the 16th century, had a complex system of horticulture.

Their capital from the 15th century was Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

One explanation for the origin of the name is that it includes the Nahuatl word nōchtli, referring to the fruit of an opuntia.

The coat of arms of Mexico shows an eagle perched on a cactus while holding a snake, an image at the center of the myth of the founding of Tenochtitlan.

The Aztecs symbolically linked the ripe red fruits of an opuntia to human hearts.

Just as the fruit quenches thirst, so offering human hearts to the sun god ensured the sun would keep moving.

Europeans first encountered cacti when they arrived in the New World late in the 15th century.

Their first landfalls were in the West Indies, where relatively few cactus genera are found.

One of the most common is the genus Melocactus.

Thus, melocacti were possibly among the first cacti seen by Europeans.

Melocactus species were present in English collections of cacti before the end of the 16th century (by 1570 according to one source) where they were called Echinomelocactus, later shortened to Melocactus by Joseph Pitton de Tourneville in the early 18th century.

Cacti, both purely ornamental species and those with edible fruit, continued to arrive in Europe, so Carl Linnaeus was able to name 22 species by 1753.

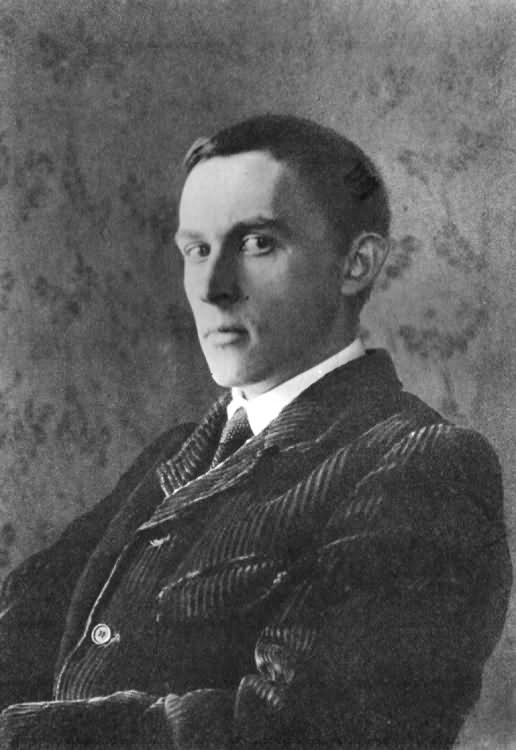

Above: Carl Linnaeus (1707 – 1778)

One of these, his Cactus opuntia (now part of Opuntia ficus-indica), was described as “fructu majore … nunc in Hispania et Lusitania” (with larger fruit … now in Spain and Portugal), indicative of its early use in Europe.

The plant now known as Opuntia ficus-indica, or the Indian fig cactus, has long been an important source of food.

The original species is thought to have come from central Mexico, although this is now obscure because the indigenous people of southern North America developed and distributed a range of horticultural varieties (cultivars), including forms of the species and hybrids with other opuntias.

Both the fruit and pads are eaten, the former often under the Spanish name tuna, the latter under the name nopal.

Cultivated forms are often significantly less spiny or even spineless.

The nopal industry in Mexico was said to be worth US$150 million in 2007.

The Indian fig cactus was probably already present in the Caribbean when the Spanish arrived, and was soon after brought to Europe.

It spread rapidly in the Mediterranean area, both naturally and by being introduced—so much so, early botanists assumed it was native to the area.

Outside the Americas, the Indian fig cactus is an important commercial crop in Sicily, Algeria and other North African countries.

Fruits of other opuntias are also eaten, generally under the same name, tuna.

Flower buds, particularly of Cylindropuntia species, are also consumed.

Almost any fleshy cactus fruit is edible.

The word pitaya or pitahaya (usually considered to have been taken into Spanish from Haitian Creole) can be applied to a range of “scaly fruit“, particularly those of columnar cacti.

The fruit of the saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) has long been important to the indigenous peoples of northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States, including the Sonoran Desert.

It can be preserved by boiling to produce syrup and by drying.

The syrup can also be fermented to produce an alcoholic drink.

Fruits of Stenocereus species have also been important food sources in similar parts of North America.

Stenocereus queretaroensis is cultivated for its fruit.

In more tropical southern areas, the climber Hylocereus undatus provides pitahaya orejona, now widely grown in Asia under the name dragon fruit.

Other cacti providing edible fruit include species of Echinocereus, Ferocactus, Mammillaria, Myrtillocactus, Pachycereus, Peniocereus and Selenicereus.

The bodies of cacti other than opuntias are less often eaten, although Anderson reported that Neowerdermannia vorwerkii is prepared and eaten like potatoes in upland Bolivia.

A number of species of cacti have been shown to contain psychoactive agents, chemical compounds that can cause changes in mood, perception and cognition through their effects on the brain.

Above: An assortment of psychoactive drugs—street drugs and medications:

- cocaine

- crack cocaine

- methylphenidate (Ritalin)

- ephedrine

- MDMA (Ecstasy – lavender pill with smile)

- mescaline (green dried cactus flesh)

- LSD (2×2 blotter in tiny baggie)

- psilocybin (dried Psilocybe cubensis mushroom)

- Salvia divinorum (10X extract in small baggie)

- diphenhydramine (Benadryl – pink pill)

- Amanita muscaria (red dried mushroom cap piece)

- Tylenol 3 (contains codeine)

- codeine containing muscle relaxant

- pipe tobacco (top)

- bupropion (Zyban – brownish-purple pill)

- cannabis (green bud center)

- hashish (brown rectangle)

Two species have a long history of use by the indigenous peoples of the Americas:

- peyote, Lophophora williamsii, in North America

- the San Pedro cactus, Echinopsis pachanoi, in South America.

Both contain mescaline.

Above: Laboratory synthetic mescaline.

Biosynthesized by peyote, this was the first psychedelic compound to be extracted and isolated.

L. williamsii is native to northern Mexico and southern Texas.

Individual stems are about 2–6 cm (0.8–2.4 in) high with a diameter of 4–11 cm (1.6–4.3 in), and may be found in clumps up to 1 m (3 ft) wide.

A large part of the stem is usually below ground.

Mescaline is concentrated in the photosynthetic portion of the stem above ground.

The center of the stem, which contains the growing point (the apical meristem), is sunken.

Experienced collectors of peyote remove a thin slice from the top of the plant, leaving the growing point intact, thus allowing the plant to regenerate.

Evidence indicates peyote was in use more than 5,500 years ago.

Dried peyote buttons presumed to be from a site on the Rio Grande, Texas, were radiocarbon dated to around 3780–3660 BC.

Peyote is perceived as a means of accessing the spirit world.

Attempts by the Roman Catholic Church to suppress its use after the Spanish conquest were largely unsuccessful, and by the middle of the 20th century, peyote was more widely used than ever by indigenous peoples as far north as Canada.

Above: Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

It is now used formally by the Native American Church.

Under the auspices of what came to be known as the Native American Church, in the 19th century, American Indians in more widespread regions to the north began to use peyote in religious practices, as part of a revival of native spirituality.

Its members refer to peyote as “the sacred medicine“, and use it to combat spiritual, physical, and other social ills.

Concerned about the drug’s psychoactive effects, between the 1880s and 1930s, US authorities attempted to ban Native American religious rituals involving peyote, including the Ghost Dance.

Today the Native American Church is one among several religious organizations to use peyote as part of its religious practice.

Some users claim the drug connects them to God.

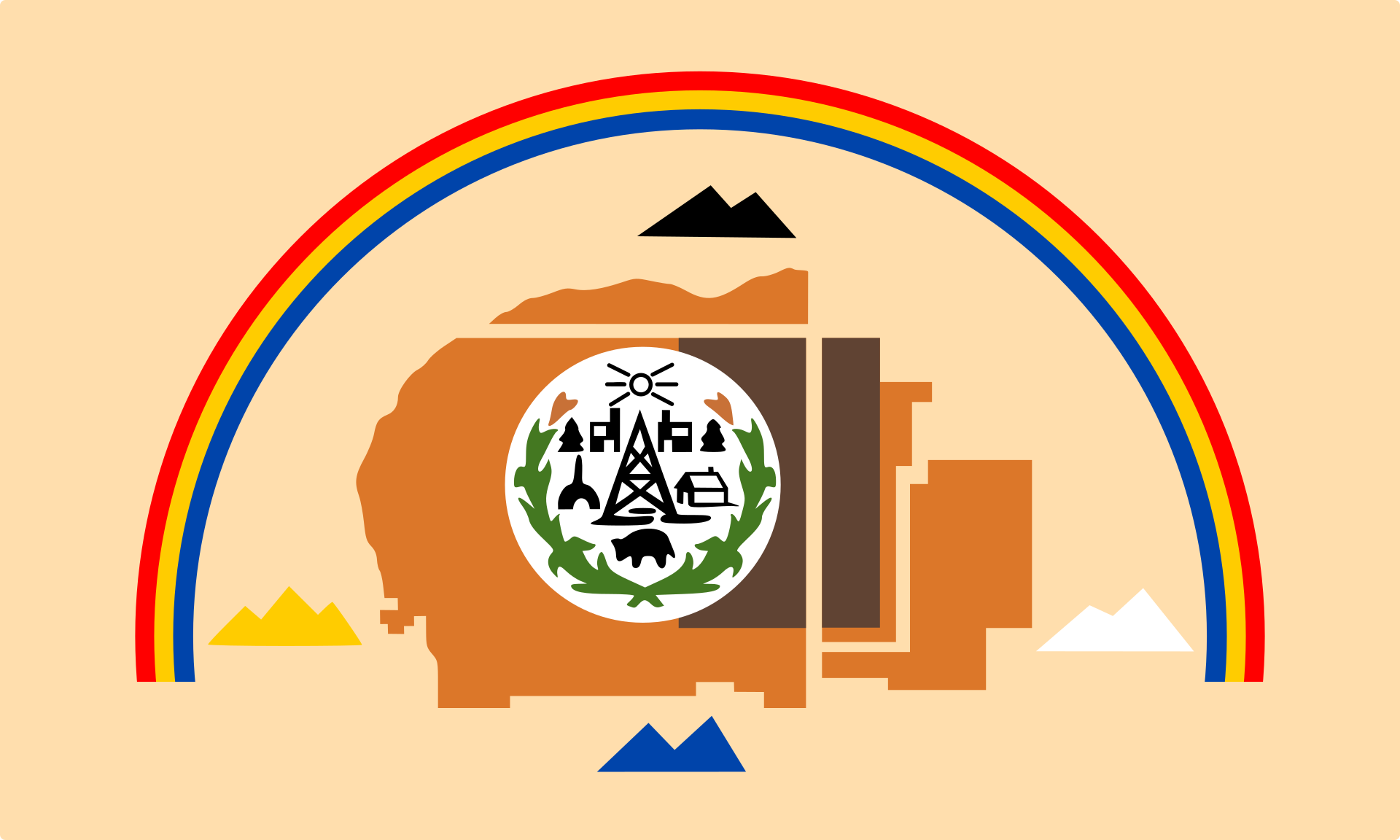

Traditional Navajo belief or ceremonial practice did not mention the use of peyote before its introduction by the neighboring Utes.

The Navajo Nation now has the most members of the Native American Church.

Dr. John Raleigh Briggs (1851–1907) was the first to draw scientific attention of the Western scientific world to peyote.

Louis Lewin described Anhalonium lewinii in 1888.

Arthur Heffter conducted self experiments on its effects in 1897.

Similarly, Norwegian ethnographer Carl Sofus Lumholtz studied and wrote about the use of peyote among the Indians of Mexico.

Lumholtz also reported that, lacking other intoxicants, Texas Rangers captured by Union forces during the American Civil War soaked peyote buttons in water and became “intoxicated with the liquid“.

The US Dispensatory lists peyote under the name Anhalonium, and states it can be used in various preparations for neurasthenia, hysteria and asthma.

Lophophora williamsii or peyote is a small, spineless cactus with psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline.

Peyote is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl, or Aztec, peyōtl, meaning “glisten” or “glistening“.

Other sources translate the Nahuatl word as “Divine Messenger“.

Peyote is native to Mexico and southwestern Texas.

It is found primarily in the Chihuahuan Desert and in the states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and San Luis Potosí among scrub.

It flowers from March to May, and sometimes as late as September.

The flowers are pink, with thigmotactic anthers (like Opuntia).

Echinopsis pachanoi is native to Ecuador and Peru.

It is very different in appearance from L. williamsii.

It has tall stems, up to 6 m (20 ft) high, with a diameter of 6–15 cm (2.4–5.9 in), which branch from the base, giving the whole plant a shrubby or tree-like appearance.

Archaeological evidence of the use of this cactus appears to date back to 2,000–2,300 years ago, with carvings and ceramic objects showing columnar cacti.

Although church authorities under the Spanish attempted to suppress its use, this failed, as shown by the Christian element in the common name “San Pedro cactus” — Saint Peter cactus.

Anderson attributes the name to the belief that just as St Peter holds the keys to heaven, the effects of the cactus allow users “to reach heaven while still on earth.”

It continues to be used for its psychoactive effects, both for spiritual and for healing purposes, often combined with other psychoactive agents, such as Datura ferox and tobacco.

Several other species of Echinopsis, including E. peruviana, also contain mescaline.

Mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic alkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.

It occurs naturally in the peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii), the San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi), the Peruvian torch (Echinopsis peruviana) and other members of the plant family Cactaceae.

It is also found in small amounts in certain members of the bean family, Fabaceae, including Acacia berlandieri.

However those claims concerning Acacia species have been challenged and have been unsupported in additional analysis.

Peyote has been used for at least 5,700 years by Native Americans in Mexico.

Europeans noted use of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies upon early contact, notably by the Huichols in Mexico.

Other mescaline-containing cacti such as the San Pedro have a long history of use in South America, from Peru to Ecuador.

In traditional peyote preparations, the top of the cactus is cut off, leaving the large tap root along with a ring of green photosynthesizing area to grow new heads.

These heads are then dried to make disc-shaped buttons.

Buttons are chewed to produce the effects or soaked in water to drink.

However, the taste of the cactus is bitter, so contemporary users will often grind it into a powder and pour it in capsules to avoid having to taste it.

The usual human dosage is 200–400 milligrams of mescaline sulfate or 178–356 milligrams of mescaline hydrochloride.

The average 76 mm (3.0 in) button contains about 25 mg mescaline.

Mescaline was first isolated and identified in 1897 by the German chemist Arthur Heffter and first synthesized in 1918 by Ernst Späth.

Frederick Smith, who in 1914 became head of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, now the Community of Christ, promoted the use of peyote during services, to induce the religious ecstasy he said he had experienced at ceremonies of various Native American nations.

During the Second World War, mescaline saw use in the infamous human experimentation programme of the Third Reich.

Nazi physician Kurt Plötner forced concentration-camp prisoners to take mescaline to see whether it would serve as a ‘truth serum’ during interrogation.

The US Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA, was testing mescaline as a ‘truth drug’ around the same time.

However, the concept was quickly rejected:

The nausea stopped participants trusting their interrogators.

The CIA later recruited Plötner for a project that evolved into the mind-control programme MKUltra.

In 1955, English politician Christopher Mayhew took part in an experiment for BBC’s Panorama, in which he ingested 400 mg of mescaline under the supervision of psychiatrist Humphry Osmond.

Though the recording was deemed too controversial and ultimately omitted from the show, Mayhew praised the experience, calling it “the most interesting thing I ever did”.

Artists and bohemians – mainly in Europe – tested mescaline’s creative potential.

Psychiatrists and psychologists jumped onto the bandwagon.

They administered it to writers, artists and philosophers, presented them with intellectual stimuli and observed their responses.

No pattern emerged.

- British surrealist painter of the 1930s, Julian Trevelyan, found ingestion inspiring.

- Basil Beaumont experienced “excruciating pain and fear“.

- Jean-Paul Sartre took mescaline shortly before the publication of his first book, L’Imaginaire.

He had a bad trip during which he was menaced by sea creatures.

For many years following this, he persistently experienced being followed by lobsters, and became a patient of Jacques Lacan in hopes of being rid of them.

Lobsters and crabs figure in his novel Nausea.

- Havelock Ellis was the author of one of the first written reports to the public about an experience with mescaline (1898).

- Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Polish writer, artist and philosopher, experimented with mescaline and described his experience in a 1932 book Nikotyna Alkohol Kokaina Peyotl Morfina Eter.

- Aldous Huxley described his experience with mescaline in the essay The Doors of Perception (1954).

- Martin Kemp, English actor and former Spandau Ballet bassist, described in an interview experiencing mescaline at a late-night party during the height of his musical career in the 1980s:

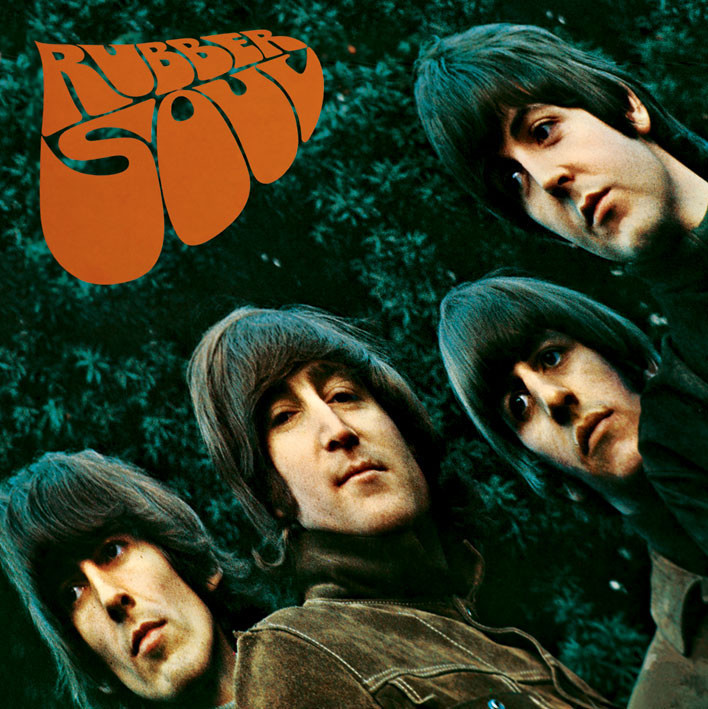

“Mescaline is the drug the Beatles wrote Rubber Soul about.

It turns everything to rubber.

Every step you take feels like rubber.

It is a lot of fun, I have to say.

But it goes on for hours – like eight hours”.

- Jim Carroll in The Basketball Diaries described using peyote that a friend smuggled from Mexico.

- Hunter S. Thompson wrote an extremely detailed account of his first use of mescaline in First Visit with Mescalito, and it appeared in his book Songs of the Doomed, as well as featuring heavily in his novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

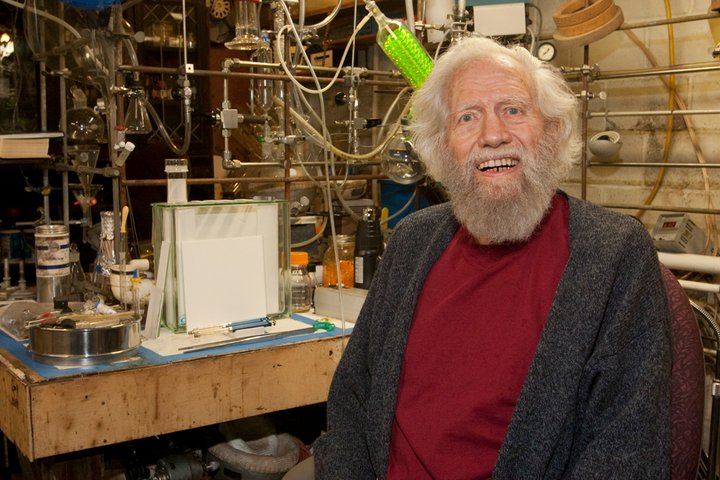

- Psychedelic research pioneer Alexander Shulgin said he was first inspired to explore psychedelic compounds by a mescaline experience.

- Bryan Wynter produced Mars Ascends after trying the substance his first time.

- According to Paul Strathern’s book Sartre in 90 Minutes, Jean-Paul Sartre experimented with mescaline, and his description of ultimate reality (in Nausea) as “viscous and obscene” was written under mescaline’s influence.

- George Carlin mentions mescaline use during his youth while being interviewed.

- Carlos Santana told in 1989 about his mescaline use in a Rolling Stone interview.

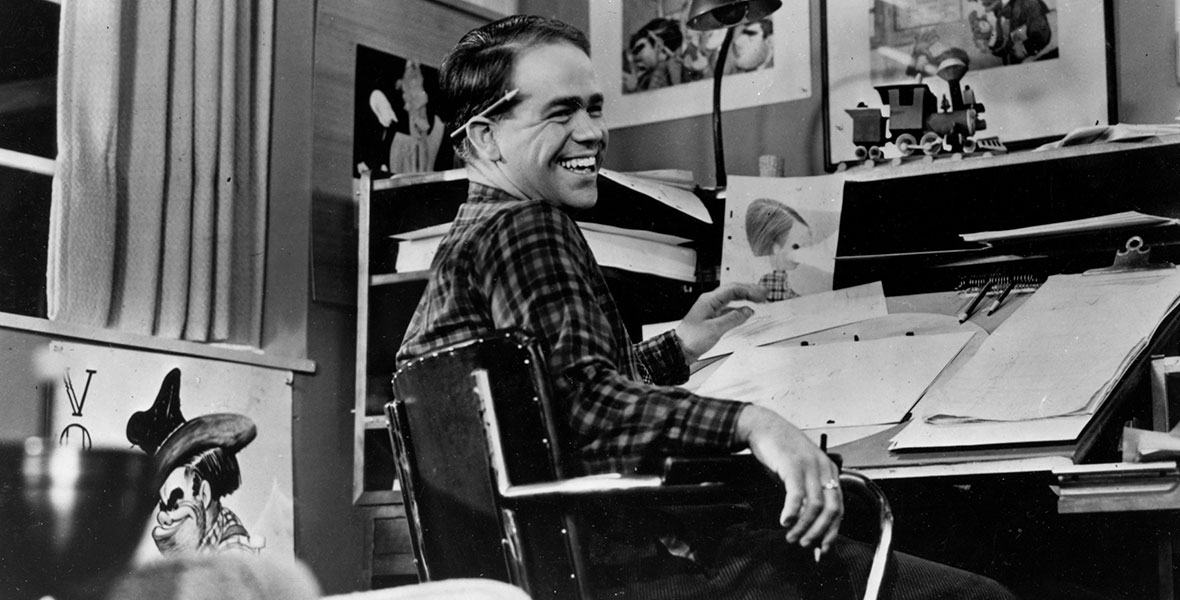

- Disney animator Ward Kimball described participating in a study of mescaline and peyote conducted by UCLA in the 1960s.

- Michael Cera used real mescaline for the movie Crystal Fairy & the Magical Cactus, as expressed in an interview.

- Philip K. Dick was inspired to write Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said after taking mescaline.

Before the 20th century, just a handful of people outside Indigenous American cultures had tried the extracts, but their reports sparked medical, spiritual and recreational interest for many decades.

The powers of endurance needed to take the drug became more widely known:

It induces hours of nausea and often vomiting before the hallucinations begin.

(In contrast to alcohol, mescaline gives you the hangover first.)

The hallucinations are now thought to be caused mainly by mescaline binding to and activating serotonin receptors in the brain.

In traditional ceremonial use, the hallucination phase has been reported as consistently transporting.

But outside these cultures, those eager to experiment have had disconcertingly unpredictable experiences.

In 1887, Texan physician John Raleigh Briggs was the first to describe, in a medical journal, his own, rather violent, symptoms — including a racing heart and difficulties breathing — after eating a small part of a ‘button’, or dried crown, of a peyote cactus.

The pharmaceutical company Parke–Davis in Detroit, Michigan, which had been investigating botanical sources of potential drugs from South America and elsewhere, took note.

The company was seeking an alternative to cocaine, whose addictive properties had become apparent.

It began offering peyote tincture as a respiratory stimulant and heart tonic in 1893.

A flurry of scientific trials began.

There was scant regard for ethics and safety — for the scientists, who frequently tested the mescaline themselves, or for test subjects.

In 1895, two reports demonstrating the drug’s unpredictability came out of what is now the George Washington University in Washington DC.

In one, a young, unnamed chemist chewed peyote buttons and then noted down his symptoms:

Nausea followed by pleasant visions over which he had some control, then depression and insomnia for 18 hours.

In the other, two scientists observed the drug’s effects on a 24-year-old man, who became deluded and paranoid.

In New York City, pharmacologists Alwyn Knauer and William Maloney carried out a more extensive trial, including 23 people, in 1913.

They hoped that mescaline, as a hallucinogen, might provide insight into the psychotic phenomena associated with schizophrenia.

It didn’t.

Above: John Nash, an American mathematician and joint recipient of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics, who had schizophrenia.

His life was the subject of the 1998 book, A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar.

The pair diligently recorded participants’ running commentaries on their hallucinations, but found no common characteristics.

(In later studies, people with schizophrenia could easily tell the difference between their own hallucinations and those induced by the drug.)

The pace of trials picked up after synthetic mescaline became available.

Chemist Ernst Späth at the University of Vienna was first to synthesize it, in 1919, and the German pharmaceutical company Merck marketed it the following year.

Yet trial outcomes did not become more reliable or illuminating.

Over the next couple of decades, theories that mescaline might reveal the biological basis of schizophrenia or help to cure other psychological disorders were serially dashed.

Above: A white cloth with seemingly random, unconnected text sewn into it using multiple colors of thread, embroidered by a schizophrenic

In the 1950s, the attention of biomedical researchers abruptly switched to a newly synthesized molecule with similar hallucinogenic properties but few physical side effects:

Lysergic acid diesthylamide (LSD).

First synthesized by Swiss scientist Albert Hoffmann in 1938, LSD went on to become a recreational drug of choice in the 1960s hippy era.

And, like mescaline, LSD teased psychiatrists without delivering a cure.

A study published in 2007 found no evidence of long-term cognitive problems related to peyote use in Native American Church ceremonies, but researchers stressed their results may not apply to those who use peyote in other contexts.

A four-year large-scale study of Navajo who regularly ingested peyote found only one case where peyote was associated with a psychotic break in an otherwise healthy person.

Above: Flag of the Navajo Nation

Other psychotic episodes were attributed to peyote use in conjunction with pre-existing substance abuse or mental health problems.

Later research found that those with pre-existing mental health issues are more likely to have adverse reactions to peyote.

Peyote use does not appear to be associated with hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (a.k.a. “flashbacks“) after religious use.

Peyote does not seem to be associated with physical dependence, but some users may experience psychological dependence.

Peyote can have strong emetic effects, and one death has been attributed to esophageal bleeding caused by vomiting after peyote ingestion in a Native American patient with a history of alcohol abuse.

Peyote is also known to cause potentially serious variations in heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and pupillary dilation.

Research into the Huichol natives of central-western Mexico, who have taken peyote regularly for an estimated 1,500 years or more, found no evidence of chromosome damage in either men or women.

Mescaline is listed as a Schedule III controlled substance under the Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, but peyote is specifically exempt.

Possession and use of peyote plants is legal.

This is not so in Switzerland:

Psychoactive cacti possession, sale, transport or cultivation is illegal.

Cacti were cultivated as ornamental plants from the time they were first brought from the New World.

By the early 1800s, enthusiasts in Europe had large collections (often including other succulents alongside cacti).

Rare plants were sold for very high prices.

Suppliers of cacti and other succulents employed collectors to obtain plants from the wild, in addition to growing their own.

In the late 1800s, collectors turned to orchids, and cacti became less popular, although never disappearing from cultivation.

Cacti are often grown in greenhouses, particularly in regions unsuited to the cultivation of cacti outdoors, such the northern parts of Europe and North America.

Here, they may be kept in pots or grown in the ground.

Cacti are also grown as houseplants, many being tolerant of the often dry atmosphere.

Cacti in pots may be placed outside in the summer to ornament gardens or patios, and then kept under cover during the winter.

Less drought-resistant epiphytes, such as epiphyllum hybrids, Schlumbergera (the Thanksgiving or Christmas cactus) and Hatiora (the Easter cactus), are widely cultivated as houseplants.

Cacti may also be planted outdoors in regions with suitable climates.

Concern for water conservation in arid regions has led to the promotion of gardens requiring less watering (xeriscaping).

For example, in California, the East Bay Municipal Utility District sponsored the publication of a book on plants and landscapes for summer-dry climates.

Cacti are one group of drought-resistant plants recommended for dry landscape gardening.

Cacti have many other uses.

They are used for human food and as fodder for animals, usually after burning off their spines.

In addition to their use as psychoactive agents, some cacti are employed in herbal medicine.

The practice of using various species of Opuntia in this way has spread from the Americas, where they naturally occur, to other regions where they grow, such as India.

Cochineal is a red dye produced by a scale insect that lives on species of Opuntia.

Long used by the peoples of Central and North America, demand fell rapidly when European manufacturers began to produce synthetic dyes in the middle of the 19th century.

Commercial production has now increased following a rise in demand for natural dyes.

Cacti are used as construction materials.

Living cactus fences are employed as barricades around buildings to prevent people breaking in.

They also used to corral animals.

The woody parts of cacti, such as Cereus repandus and Echinopsis atacamensis, are used in buildings and in furniture.

The frames of wattle and daub houses built by the Seri people of Mexico may use parts of Carnegiea gigantea.

The very fine spines and hairs (trichomes) of some cacti were used as a source of fiber for filling pillows and in weaving.

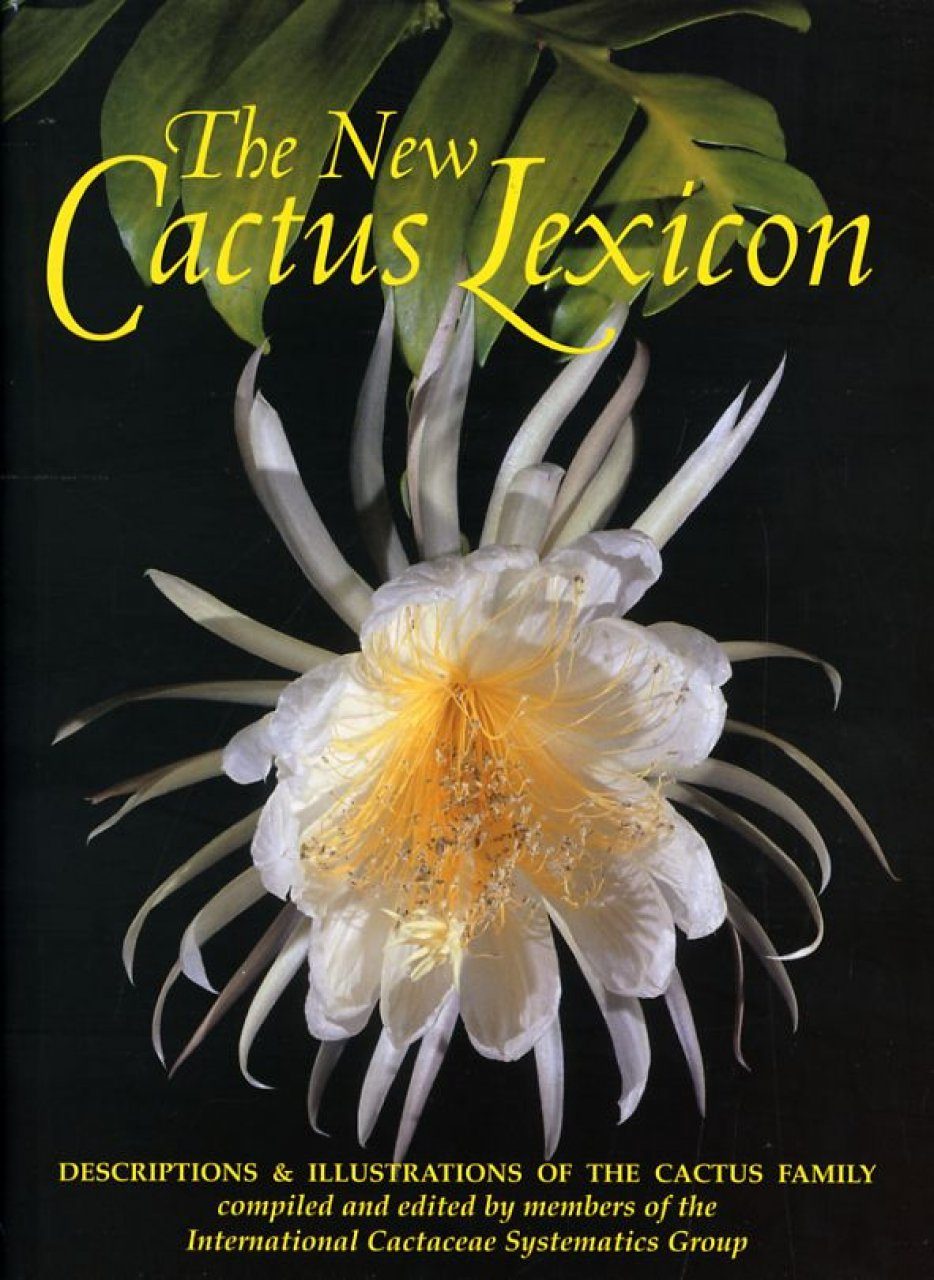

The popularity of cacti means many books are devoted to their cultivation.

The purpose of the growing medium is to provide support and to store water, oxygen and dissolved minerals to feed the plant.

In the case of cacti, there is general agreement that an open medium with a high air content is important.

When cacti are grown in containers, recommendations as to how this should be achieved vary greatly.

If asked to describe a perfect growing medium, “ten growers would give 20 different answers“.

The general recommendation of 25–75% organic-based material, the rest being inorganic such as pumice, perlite or grit, is supported by many sources.

Semi-desert cacti need careful watering.

General advice is hard to give, since the frequency of watering required depends on where the cacti are being grown, the nature of the growing medium, and the original habitat of the cacti.

More cacti are lost through the “untimely application of water than for any other reason” and that even during the dormant winter season, cacti need some water.

Other sources say that water can be withheld during winter (November to March in the Northern Hemisphere).

Another issue is the hardness of the water.

Where it is necessary to use hard water, regular re-potting is recommended to avoid the build up of salts.

The general advice given is that during the growing season, cacti should be allowed to dry out between thorough waterings.

A water meter can help in determining when the soil is dry.

Although semi-desert cacti may be exposed to high light levels in the wild, they may still need some shading when subjected to the higher light levels and temperatures of a greenhouse in summer.

Allowing the temperature to rise above 32 °C (90 °F) is not recommended.

The minimum winter temperature required depends very much on the species of cactus involved.

For a mixed collection, a minimum temperature of between 5 °C (41 °F) and 10 °C (50 °F) is often suggested, except for cold-sensitive genera such as Melocactus and Discocactus.

Some cacti, particularly those from the high Andes, are fully frost-hardy when kept dry (e.g. Rebutia minuscula survives temperatures down to −9 °C (16 °F) in cultivation) and may flower better when exposed to a period of cold.

Cacti can be propagated by seed, cuttings or grafting.

Seed sown early in the year produces seedlings that benefit from a longer growing period.

Seed is sown in a moist growing medium and then kept in a covered environment, until 7–10 days after germination, to avoid drying out.

A very wet growing medium can cause both seeds and seedlings to rot.

A temperature range of 18–30 °C (64–86 °F) is suggested for germination.

Soil temperatures of around 22 °C (72 °F) promote the best root growth.

Low light levels are sufficient during germination, but afterwards semi-desert cacti need higher light levels to produce strong growth, although acclimatization is needed to conditions in a greenhouse, such as higher temperatures and strong sunlight.

Reproduction by cuttings makes use of parts of a plant that can grow roots.

Some cacti produce “pads” or “joints” that can be detached or cleanly cut off.

Other cacti produce offsets that can be removed.

Otherwise, stem cuttings can be made, ideally from relatively new growth.

It is recommended that any cut surfaces be allowed to dry for a period of several days to several weeks until a callus forms over the cut surface.

Rooting can then take place in an appropriate growing medium at a temperature of around 22 °C (72 °F).

Grafting is used for species difficult to grow well in cultivation or that cannot grow independently, such as some chlorophyll-free forms with white, yellow or red bodies, or some forms that show abnormal growth (e.g., cristate or monstrose forms).

For the host plant (the stock), growers choose one that grows strongly in cultivation and is compatible with the plant to be propagated: the scion.

The grower makes cuts on both stock and scion and joins the two, binding them together while they unite.

Various kinds of graft are used—flat grafts, where both scion and stock are of similar diameters, and cleft grafts, where a smaller scion is inserted into a cleft made in the stock.

Commercially, huge numbers of cacti are produced annually.

For example, in 2002 in Korea alone, 49 million plants were propagated, with a value of almost US$9 million.

Most of them (31 million plants) were propagated by grafting.

A range of pests attack cacti in cultivation.

Those that feed on sap include:

- mealybugs, living on both stems and roots

- scale insects, generally only found on stems

- whiteflies, which are said to be an “infrequent” pest of cacti

- red spider mites, which are very small but can occur in large numbers, constructing a fine web around themselves and badly marking the cactus via their sap sucking, even if they do not kill it

- thrips, which particularly attack flowers.

Some of these pests are resistant to many insecticides, although there are biological controls available.

Above: Pesticide application can artificially select for resistant pests.

In this diagram, the first generation happens to have an insect with a heightened resistance to a pesticide (red).

After pesticide application, its descendants represent a larger proportion of the population, because sensitive pests (white) have been selectively killed.

After repeated applications, resistant pests may comprise the majority of the population.

Roots of cacti can be eaten by the larvae of sciarid flies and fungus gnats.

Slugs and snails also eat cacti.

Fungi, bacteria and viruses attack cacti, the first two particularly when plants are over-watered.

Fusarium rot can gain entry through a wound and cause rotting accompanied by red-violet mold.

“Helminosporium rot” is caused by Bipolaris cactivora (syn. Helminosporium cactivorum).

Phytophthora species also cause similar rotting in cacti.

Fungicides may be of limited value in combating these diseases.

Several viruses have been found in cacti, including cactus virus X.

These appear to cause only limited visible symptoms, such as chlorotic (pale green) spots and mosaic effects (streaks and patches of paler color).

However, in an Agave species, cactus virus X has been shown to reduce growth, particularly when the roots are dry.

There are no treatments for virus diseases.

As aforementioned, Jardín de Cactus was the last intervention work César Manrique performed in Lanzarote.

The artist from Lanzarote could see beyond how run down the ancient rofera was.

Roferas were the quarries that raids are taken from to create a very particular home for cactaceae flowers from all over the world.

Surrounded by the largest cactus plantation of the island, dedicated to crops of cochineal insect, a product of great financial relevance in Lanzarote in the 19th Century.

Jardín de Cactus has around 4,500 specimens of 450 different species, of 13 different families of cactus from the five continents.

The green shade of the plants stands out against the blue sky and the dark volcano creating a harmonious explosion of colour that impresses visitors.

The only sounds that break the peace and quiet that prevails, are singing birds and buzzing insects, enjoying their very own oasis.

High volcanic ash monoliths, that maintain the memory of years gone by, challenging plants from America, Africa and Oceania.

At the top, on a small hill, windmills can be seen on the horizon, still standing, where Canarian cornmeal was ground dating back to the 19th century.

While I have never been a big fan of cacti, I must admit that I was delightedly surprised by the Jardín’s display of such a wide variety of cacti, in all shapes, sizes and colours.

The impression we got from our guidebooks was that the Jardín was a large garden type set-up where you could walk around and basically get lost in a world of cacti.

Granted it is a large collection of cacti assembled and arranged in a quarry-type environment on different levels.

It is certainly impressive and the range of plants is extensive, but once you have paid the entrance fee and have passed through onto the uppermost level you have seen everything at a single glance.

And that is this attraction’s disadvantage.

You can go down to the lower levels and get up close to the individual plants but not too close.

As slow travellers it took us about an hour to see all there is to see, but most fellow tourists seemed sated with the Jardín within 30 minutes.

The reason why folks are quickly bored despite the bounty and beauty on display is that more information (such as that written above) about the cacti would be useful and entertaining.

Why did Manrique choose cacti?

Did he visit Mexico?

Did he try peyote?

Could peyote have inspired his art and architecture?

Are these psychoactive cacti part of the Jardín’s collection?

And what of the stories and legends behind each type of cactus?

In 1984, it was decided that the Cactaceae Section of the International Organization for Succulent Plant Study should set up a working party, now called the International Cactaceae Systematics Group (ICSG), to produce consensus classifications down to the level of genera.

Their system has been used as the basis of subsequent classifications.