Eskişehir, Türkiye

Saturday 23 March 2024

“Inspiration does exist, but it has to find you working.“

(Pablo Picasso)

Above: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

“I had a poem in my head last night, flashing as only those unformed midnight poems can.

It was all made up of unexpected burning words.

I knew even in my half-sleep that it was nonsense, meaningless, but that forcing and hammering would clear its shape and form.

Now not a word of it remains, not even a hint of its direction.

What a pity one cannot sleepwrite on the ceiling with one’s finger or lifted toe.“

(23 March 1946, Denton Welch)

Above: British writer and artist Denton Welch (1915 – 1948)

Welch made one mistake.

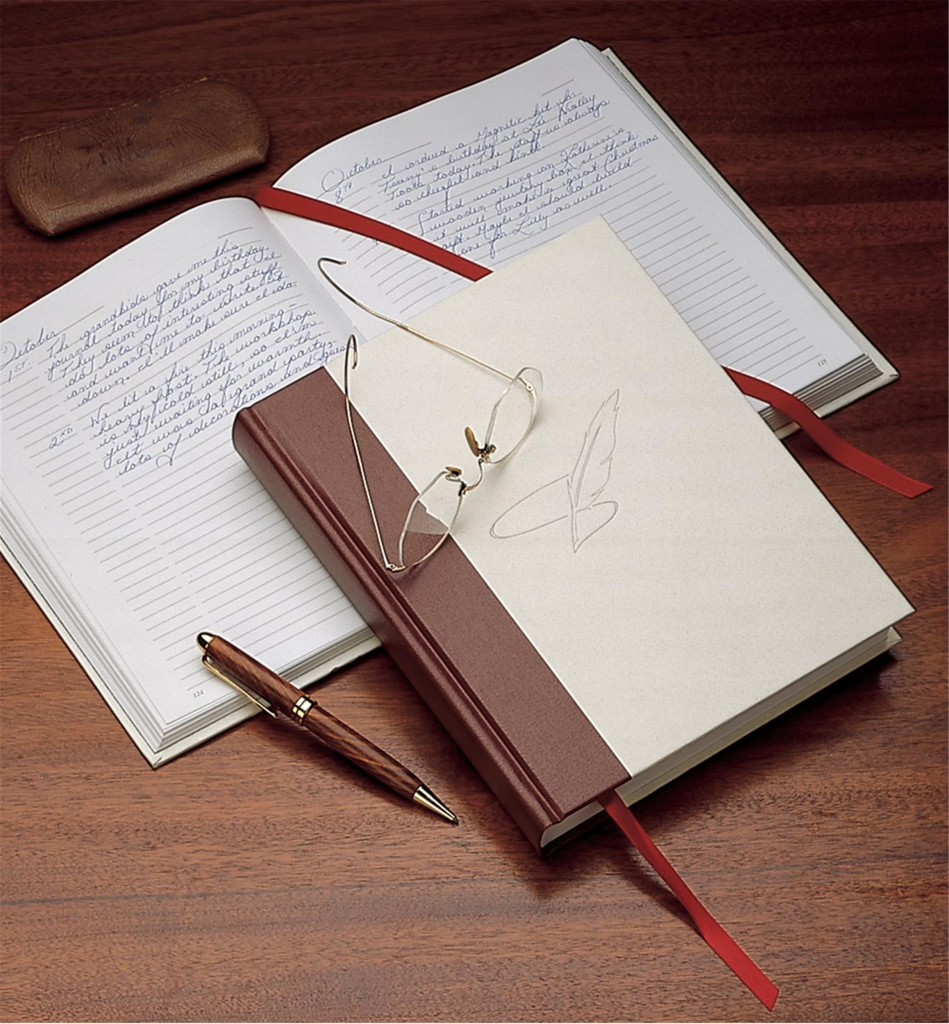

Always, always have a notebook to hand.

Many writers conscientiously keep dream diaries as repositories of the strange wisdom that comes to us in the night and which we can draw on later when creating our polished work.

Your notebook is a weapon for holding your free-range thoughts.

Ideas are tricky little creatures.

There are always millions of them around – more than enough for all the writers that have ever been or ever will be.

The organic free-range ideas that run through your head at all sorts of odd times can be speedy, fleeting, even ghostly creatures that are hard to catch.

But, if you make sure you have a notebook to hand at all times, you will stand a good chance of corralling them and developing them, so that these stray wild creatures become fully formed and wholly yours.

Sometimes, you will pin these ideas into the pages of your book and, on returning to them, find that they have withered away.

Sometimes they were so spindly that they had no chance of growing to a useable size however much you fed or watered them.

It is perhaps best to think of ideas, elusive and slippery things that they are, not as thoughts but as opportunities.

All of them may grow into the thing that helps you produce a great piece of work:

Something that may even make your name and your reputation.

If you don’t catch them as they pass, they will disappear.

Don’t trust that you will remember them or recapture the essence later.

You almost certainly won’t.

If you don’t write them down they will vanish, leaving just a sulphuric whiff of frustration and lost opportunity.

Some useful ideas may hurtle out of the sky or scurry through your mind as if from nowhere.

Others you may have to nurture from scratch.

Either way, the blank page (or screen) is always a tyrant to any writer, which is why so many start the day with automatic or free writing – anything to stop the oppression of all that white space.

Try your hand at free writing.

Set a timer to go off after five minutes and just keep writing for the whole of that time.

Don’t allow your conscious mind to interfere.

Just keep writing.

Keep your pen moving for the whole period.

At least one useful nugget will emerge that might be worked on later.

More than this, the act of writing will help you loosen up for the challenges of your current writing project.

“I never travel without my diary.

One should always have something sensational to read in the train.“

(Oscar Wilde)

Above: Irish writer Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

Keeping a regular journal is one of the most common pieces of advice given to aspiring writers.

Maintaining a record of the day-to-day events of our lives, the places we have been, the people we have met and the interesting, funny or odd things that happen to us as we move through our lives is excellent writing practice and a great source of ideas.

A journal is a private place in which you can write about anything you want.

It does not have to be a record of what you have done that day.

You can write about your memories or ambitions.

You can speculate on the private lives of others.

You can make lists of things you love and things you hate.

And if you don’t have anything to write about, you can just make something up.

There is no one right way to keep a journal, but if you have some sort of notebook that you return to often with your written thoughts, opinions, observations and various bits of wit, you will have a place in which to exercise your writing muscles.

You will learn to describe succinctly and clearly the events of your daily life.

You will learn to pluck from each event just the details needed to create a sense of the whole.

If you keep a journal, you will grow as a writer.

You will find that sooner or later, no matter what you have to write professionally, your personal experiences will play a part.

Keep in mind that a journal can be far more than just a diary.

You can take notes from a conversation.

You can take notes while you are reading or eating at a restaurant.

“What would happen if I forced myself over a period of seven months to sluice my mind the way I sluiced dirt in my gold-hunting days, using a diary as a sluicebox to trap whatever flakes of insight might turn up?“

Eric Hoffer asked himself that question in his journal on 26 November 1974.

He did not expect a happy outcome.

“I had the feeling that I had been scraping the bottom of the barrel and doubted whether I would ever get involved in a new seminal train of thought.

It was legitimate to assume that at the age of 72 my mind was played out.

Would it be possible to reanimate and cultivate the alertness to the first faint stirrings of thought?“

In due course, Hoffer was able to report that the experiment had succeeded reasonably well.

“It is more than six months since I started this diary.

I wanted to find out whether the necessity to write something significant every day would revive my flagging alertness to the first faint stirrings of new ideas.

I also hoped that some new insight caught in flight might be the seed of a train of thought that could keep me going for years.

Did it work?

The diary flows, reads well, and has something striking on almost every page.

Here and there I suggest that a new idea could be the subject of a book, but only one topic – “the role of the human factor” – gives me the feeling that I have bumped against something which is, perhaps, at the core of our present crisis.“

Above: American philosopher Eric Hoffer (1902 – 1983)

Keeping an intellectual journal is the besy way to cultivate your own “alertness to the first faint stirrings of thought“.

Vırtually every important writer and thinker has kept such a diary, whether they called it a notebook, daybook or something more personal.

Abraham Maslow pointed out:

“Every intellectual used to keep a journal and many have been published and are usually more interesting and more instructive than the final formal perfected pages which are so often phony in a way – so certain, so structured, so definite.

The growth of thought from its beginnings is also instructive – maybe even more so for some purposes.“

Above: American psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970)

The most ambitious log kept by any individual is Buckminster Fuller’s Chronolog.

It contains “any and every scrap of paper that was written by him, about him or to him“, according to one of his biographers, Athena Lord.

Fuller was encouraged in the practice by his first boss, the chief engineer of his factory:

“For your own sake and knowledge, you should keep a sketchbook of your work.”

Lord writes:

“Flushed with happiness, Bucky followed his advice.

The sketchbook made a kind of mental bank account from which he drew all his life.

From a shoebox full of paper, the collection has grown to six tons of records now stored in the Science Center in Philadelphia.“

Above: American architect Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983)

The charming Morning Notes of that remarkable amateur in psychology, philosophy and biology, Adelbert Ames, Jr., suggest how freewheeling and personal the style of such writing can be.

His friend and editor, Hadley Cantril, describes the method:

“He had the habit of putting a problem to hımself in the evening just before he went to bed.

Then he “forgot” it.

The problem never seemed to disturb his sleep, but he often”found” the next morning on awakening that he had made progress on the problem.

And as soon as he got to his office he would pick up his pencil and a pad of paper and begin to write.

He always said he did not know just “what would come out”.

Dozens of times he would call me at Princeton in the middle of the morning, ask, courteously, if I had a few minutes and say:

“Hadley, listen to this. I am surprised at the way it is turning out and I think it will interest you.“

It was almost as though he himself were a spectator.“

Above: American scientist Adelbert Ames Jr. (1880 – 1955)

You will gradually find your own best method of generating thoughts.

The crucial thing is to start.

It is the doing that teaches us how.

You will want to draw from a wide range of sources for your “sluicing“.

Perhaps, follow the suggestions of Dr. Ari Kiev:

“You might start by clipping and pasting newspaper articles that interest you for the next 30 days.

At the end of that time, see if there isn’t some trend suggestive of a deep-seated interest or natural inclination.

Keep alert each day to the slightest indications of special skills or talents, even when they seem silly or unimportant to you.

Take note of the remarks of friends and relatives when they say that something is “typical of you”.”

Above: American psychiatrist Dr. Ari Kiev (1934 – 2009)

Who are you?

- in terms of the kinds of people you most prefer to associate with

- in terms of your workplace

- in terms of what you can do

- in terms of what you already know and what your favourite interests

- in terms of where you would prefer to be

- in terms of what you are responsible for

- in terms of your goals, your sense of mission and purpose for your life

- in terms of what you find beautiful as felt by all your senses

- in terms of your health

- in terms of what you own and what you would like to possess

- in terms of matters of conscience

- in terms of those you love and the love that you seek

- in terms of how you like to relax

- in terms of how you interact with the world around you

- in terms of what you believe in

- in terms of what you know and what you are interested in knowing more about

Who are you?

Learning who you are allows you to:

- discover what you are passionate about

- learn what your strengths and skills are

- challenge societal definitions of balance and success

- commit to something bigger than yourself

- live authentically and with joy

- become good at what matters to you and what opportunities this presents

- feel pleasure in all that you do

- stay focused on well-being and life satisfaction

- find clarity and accept responsibility in designing your own life

- let the world know, with humility and assertiveness, what you have discovered what you want

Why do you write?

Because you have something to say.

The point of Life is to decide who you are and then try to become that person.

And how can you do this without writing?

How can we do that if we don’t try to express our own unique way of seeing the world?

Why do you write?

To discover what you think and feel.

When we write for others to read, we transform our own existence into words that delight, entertain, amuse or inform others.

Our words have value.

Our individual attempts to make sense of our lives contribute to the way humanity itself discovers its nature and purpose.

Everyone’s story has value.

It can all begin with the words….

“Dear Diary…“

Sources

- The Digital Nomad Handbook (Lonely Planet)

- What Color Is Your Parachute?, Richard Bolles (Ten Speed Press)

- The Independent Scholar’s Handbook, Ronald Gross (Ten Speed Press)

- Get Started in Creative Writing, Stephen May (Teach Yourself)

- 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing, Gary Provost (Berkley)