Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 27 March 2024

ADDRESSED TO A CERTAIN NOBODY

Poland Street, London, 27 March 1768

To have some account of my thoughts, manners, acquaintances and actions, when the hour arrives in which time is more nimble than memory, is the reason which induces me to keep a Journal.

A Journal in which I must confess my every thought, must open my whole heart!

But a thing of this kind ought to be addressed to somebody – I must imagine myself to be talking – talking to the most intimate of friends – to one in whom I should take delight in confiding and remorse in concealment – but who must this friend be?

To make choice of one in whom I can but half rely, would be to frustrate entirely the intention of my plan.

The only one I could wholly, totally confide in, lives in the same house with me, and not only never has, but never will, leave me one secret to tell.

To whom, then, must I dedicate my wonderful, surprising and interesting adventures?

To whom dare I reveal my private opinion of nearest relations?

My secret thoughts of my dearest friends?

My own hopes, fears, reflections and dislikes?

Nobody?

To Nobody, then, will I write my Journal!

Since to Nobody can I be wholly unreserved – to Nobody can I reveal every thought, every wish of my heart, with the most unlimited confidence, the most unremitting sincerity to the end of my life!

For what chance, what accident can end my connections with Nobody?

No secret can I conceal from Nobody and to Nobody can I be ever unreserved.

Disagreements cannot stop our affection.

Time itself has no power to end our friendship.

The love, the esteem I entertain for Nobody.

Nobody does not have the power to destroy.

From Nobody I have nothing to fear, the secrets sacred to friendship.

Nobody will not reveal when the affair is doubtful. Nobody will not look towards the side least favourable.

I will suppose you, Nobody, then, to be my best friend, (though God forbid you ever should!) my dearest companion – and a romantic, for mere oddity may perhaps be more sincere – more tender – than if you were a friend in propria persona – in as much as imagination often extends reality.

In your breast my errors may create pity without exciting contempt, may raise your compassion without eradicating your love. From this moent, then, my dear – but why, permit me to ask, must you be made Nobody?

Ah, my dear, what were this world good for were Nobody real?

And now I have done with preambulation.“

(Fanny Burney)

Above: Frances Burney (aka Fanny Burney) (1752 – 1840)

Who knows my secret broken bone?

Who feels my flesh when I am gone?

Who was a witness to the dream?

Who kissed my eyes and saw the scream

Lying there?

Nobody

Who is my reason to begin?

Who plows the earth, who breaks the skin?

Who took my two hands and made them four?

Who is my heart, who is my door?

Nobody

Nobody but you, girl

Nobody but you

Nobody in this whole wide world

Nobody

Who makes the bed that can’t be made?

Who is my mirror, who is my blade?

When I am rising like a flood

Who feels the pounding in my blood?

Nobody

Nobody but you

Nobody but you, girl

Nobody in this whole wide world

Nobody, girl

Nobody

Nobody but you

Nobody but you

Nobody in this whole wide world

Nobody, nobody

Nobody

(Paul Simon, One Trick Pony, 1980)

The Scottish poet William Soutar wrote:

“A diary is like drink, we tend to indulge in it over often.

It becomes a habit which would ever seduce us to say more than we have the experimental qualifications to state.”

It must be said that Soutar, bedridden with a wasting illness, was a special case.

Trapped from a young age in a small room in his parents’ house in Perth, his view of the world circumscribed by the size of his window.

Above: Perth, Scotland

He was, in effect, a prisoner.

His diary was his constant companion, a visitor who never went away.

Thus the temptatıon to overindulge.

Above: Bust of William Soutar (1898 – 1943)

For many people, however, a diary is like a reproach, a perpetual reminder of our lack of discipline, absence of application, weakness of resolve.

How many diaries, started in the first flush of a New Year, peter out even before the memort of the annual hangover?

We open the pristine book with enthusiasm but after a few days what had been a torrent turns into a drip.

Soon, whole weeks go by unremarked, blank page followed by blank page.

Humdrum life intrudes and the compulsion to memorialize in print evapoarates.

There are few things quite as capable of inducing guilt as an empty diary.

Soutar, his life cruelly condemned, came to depend on his diary.

It was his friend, crutch, confidant, shrink, father confessor, mirror of himself, for a diary is the most flexible and intimate of literary forms.

Diaries have been kept by everyone, from the barely literate to the leaders of men and women, from serial killers to conmen, kitchen maids to all-conquering heroes, children and nonagenarians, tinkers, tailors, soldiers and spies.

Some diarists are chroniclers of the everyday.

Others have kept their books only in special times – over the course of a trip or during a crisis.

Some have used them to record journeys of the soul, plan the art of the future, confess the sins of the flesh, lecture the world from beyond the grave.

And some of them, prisoners and invalids, have used them not so much to record lives as create them, their diaries being the only world in which they could fully live.

Into the last category falls William Soutar, who but for his diary and a few verses in Scots for children – would now be forgotten.

Though he began keeping a diary in 1917, when he was 19 years old and serving in the Atlantic with the Navy, it comprised little more than brief notes of appointments and books read.

His diary took on a fresh complexion, however, after February 1929, when he fell ill with pneumonia.

His right leg became increasingly disabled.

In hindsight, the prescribed treatment seems medieval.

Weights were put on the leg to counteract muscle contraction.

When this failed, the only hope was surgery.

In May 1930, Soutar was operated on, paraphrasing Milton as he went to his fate:

“This is the day and the happy morn.

At 0930 got morphine and atropine injection.

Off to theatre – sine crepuscula toga – at 10 a.m.

Never saw actual theatre – elderly doctor chloroformed me in the “green room”.

Woke up again at 11:20 or so.

Wasn’t sick.

Not an extra lot of reaction.

Plaster of Paris troubling me more than the leg – nasty nobbly part at back – can’t be comfortable.“

Above: English poet John Milton (1608 – 1674)

The operation was unsuccessful but the stoical philosophical Soutar gives little indication of despair, of the hopelessness of his plight.

Soutar’s main interest was not his own invalidism but the general human situation.

On occasion, he fletfrustrated and sorry for himself but more often he managed to transcend his illness, setting himself goals – reading the Encyclopaedia Britannica, for example – and pursuing his ambitions.

Due to his unusual circumstances, the world had to come to him, rather than the other way around.

But unlike many other diarists who are consumed with themselves, egocentrics who seem to live only inside their heads and are obsessed with their own troubles, Soutar managed to transcend the self and entered an elevated state of being.

Just a month before he died in October 1943, he wrote:

“The true diary is one, therefore, in which the diarist is, in the main, communing with himself, conversing openly and without pose, so that trifles will not be absent, not the intimate and little confessions and resolutions which, if voiced at all, must be voiced in such a private confessional as this.“

Above: William Soutar Trail, Perth, Scotland

When, truly, is a diary a diary?

What is the difference between a diary and journal or, for that matter, a log or a notebook?

Dictionary definitions are not much help.

A diary is “a daily record of events, transactions, thoughts, etc., especially ones involving the writer.”

A journal, on the other hand, is defined thus:

“A personal record of events or matters of interest, written up every day or as events occur, usually in ore detail than a diary.”

It is a fine distinction and one which individual writers seem blithely to ignore.

In his Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce wrote:

“Diary: a daily record of that part of one’s life which he can relate to himself without blushing.”

Above: American writer Ambrose Bierce (1842 – 1914)

Oscar Wilde, however, went a step further:

“I never travel without my diary.

One should always have something sensational to read in the train.”

Above: Irish writer Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

For others, though, a diary serves more prosaic purposes.

“If a man has no constant lover who shares his soul as well as his body he must have a diary – a poor substitute, but better than nothing.“, mused James Lees-Milne.

Above: English writer James Lees-Milne (1908 – 1997)

More often or not, writers question why they do or do not keep a diary:

The Reverend Francis Kilvert asked:

“Why do I keep this voluminous journal?

I can hardly tell.

Partly because life appears to me such a curious and wonderful thing that it almost seems a pity that even such a humble and uneventful life as mine should pass altogether away without some such record as this, and partly too because I thnk the record may amuse and interest some who come after me.”

Above: English diarist Robert Francis Kilvert (1840 – 1879)

Sir Walter Scott deemed not keeping a diary one of the regrets of his life.

Above: Scottish writer Walter Scott (1771 – 1832)

But perhaps one of the most curious comments on diary-keeping came from A.A. Milne when he remarked in 1919:

“I suppose this is the reason why diaries are so rarely kept nowadays – that nothing ever happens to anybody.“

Above: English writer Alan Alexander Milne (1882 – 1956)

The idea that diaries are not only worth keeping when great events are in train is hardly worthy of examination.

The human condition is such that there is always something happening somewhere, whether personally or politically, parochially or on the international stage.

The most durable diarists have not always been those who mix in high society or are connected with the great and the good and have the opportunity to peek through the keyhole as momentous events unfold.

The best diaries are those in which the voice of the individual comes through untainted by self-censorship or a desire to please.

First and foremost, the diarist must write for himself.

Those who do not, who are invariably looking towards publication and public recognition, invariably strike a phoney note.

The first real diarist was Samuel Pepys, who may not have patented the form but was certainly instrumental in its development.

Pepys’ naive enthusiasm for self-reckoning has been echoed by diarists down the decades.

Life, unvarnished and uncensored, is what Pepys’ diary such a constant source of wonder.

In every entry, Pepys reveals something of his true self, from his disquiet at discovering that the food he had been served at a friend’s house was rotten to his views on Shakespeare and his unalloyed and unequivocal delight at coming into a legacy.

Above: English diarist Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703)

A diary, at least to begin with, is not a daunting prospect, like an epic poem or a play or a novel.

There is no imperative to publish or show anyone how it is progressing.

You don’t need to do any research or check facts.

Entries can be long or short, factual or inaccurate, real or imagined.

Though diarists, invariably, attempt to keep up a daily routine they just as invariably fail.

Life has its insidious way of interrupting the flow.

Some diarists take this in their stride while it throws others into a spin, as if they had forgotten to turn up for a dinner party or missed a job interview.

Time after time one comes across diarists chastising themselves for their laziness, their inconstancy, their lack of fidelity to a diary which they address as they might address a lover.

For communion with a diary is unlike any other literary activity.

Once a diarist, always a diarist, it seems.

A diary becomes part of a diarist’s routine, an integral part of his household, a member of the family which needs to be nurtured like a baby or a pet kitten.

Neglect is conspicuous but it need not be harmful, for silence has its own eloquence.

While many diarists write entries daily, as if brushing their teeth, others let weeks and months go by without so much as writing a few lines.

Some diarists write during times of emotional and financial crisis, others when they are at their most happy and socially active.

Evelyn Waugh, one of the great 20th century diarists, kept a diary for diverse reasons:

“Fading memory and a senile itch to write to the Times on all topics have determined me to keep irregular notes of what passes through my mind.”

Waugh, in common with most diarists, wrote with no intention of seeing his diary in the public domain.

He wrote privately and did not tell many of his friends that he kept a diary.

Even his wife did not know.

Though not by nature furtive, he seemed to want to keep his diaries to himself.

Why?

No one knows.

Above: English writer Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (1903 – 1966)

Each diarist is an individual describing his life, for which he needs make no excuses.

Curiosity is not the least of the attractions of reading a diary.

Until the ğresent age, when it is possible if one is so inclined to view every moment of complete strangers’ lives via the Internet, a diary was the closest one could get to understanding the way people lived and thought.

Without the commonplace and the trivial the best diaries would be bereft of much that makes them compelling and enduringly fascinating.

That which many people might not deem worth recording sheds the most brilliant light on the diarist’s character or illuminates the times in which he lived.

Often, one is struck by the ability of great diarists to combine in a single entry news either momentous or terrifying, or both, with some minor observations or irritation of everyday life.

It is in a diary that our private world imperceptibly merges with the cataclysmic events which make headlines in every language.

All human life is here.

The diarist is a genre to which it is impossible to ascribe formulas and standards.

Ultimately, any attempt at definition is defeated by the diarists themselves who are the most singular of species.

More than any other branch of literature, diaries revel in otherness.

Like a chameleon, a diary can change in colour to suit the mood of its keeper.

It can be whatever the diarist wants it to be.

Franz Kafka used his to pour out his angst and limber up for his novels and short stories.

Above: Bohemian writer Franz Kafka (1883 – 1924)

Dorothy Wordsworth brought her botanical eye to the landscape of the Lake District, providing rich source material which her brother William mined for his poetry.

Above: English writer Dorothy Wordsworth (1771 – 1855)

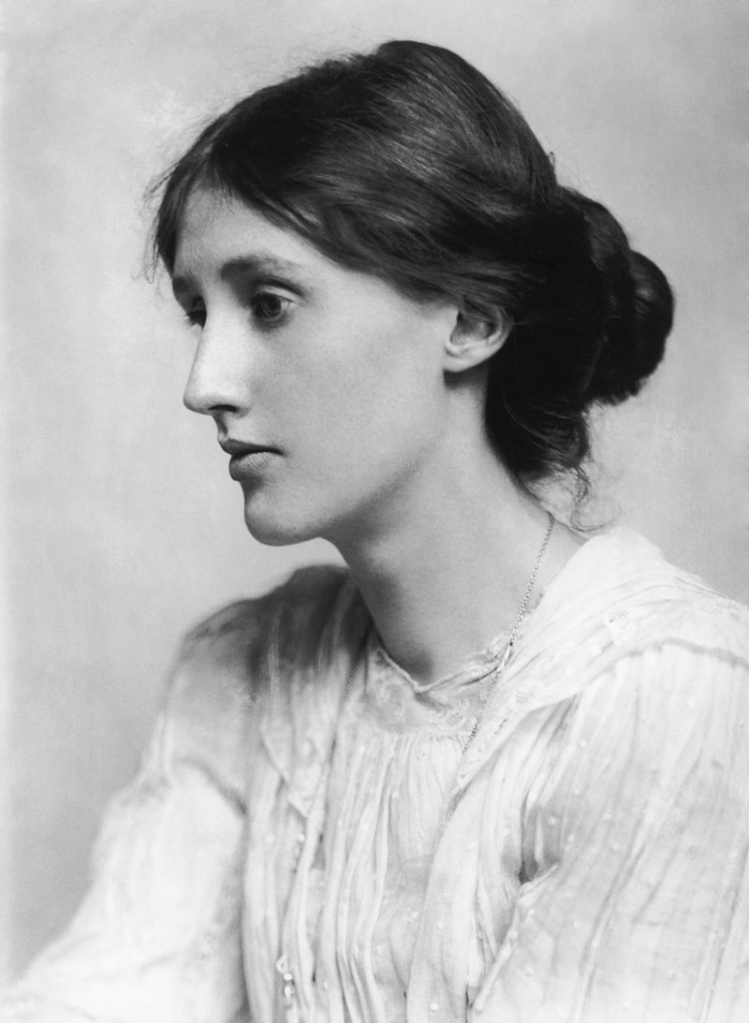

Virginia Woolf spoke to hers as she might to an intimate friend, in so doing etching a portrait of the artist on the edge of the abyss.

Above: English writer Adeline Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941)

All contributed to the mosaic that is life, but one keeps coming back to William Soutar, lyıng on his back in bed as his health evaporated.

His diary is an inspiration.

It may be the work of a dying man but he lived for the moment.

Soutar sagely realized better than most the ambiguous potential of a diary, imbued as it inevitably is with secrecy and all it implies.

A diary may be like drink, but it is also only as reliable as the diarist.

Not only can it persuade us to betray the self, “it tempts us to betray our fellows also, becoming thereby an alter ego sharing with us the denigrations which we would be ashamed of voicing aloud.

A diary is an assassin’s cloak which we wear when we stab a comrade in the back with a pen.

And here is the diary proving its culpability to its own harm –

For how much on this page is true to the others?“

Above: Pavement poem (William Soutar) Writers Museum, Edinburgh, Scotland

“Write what you know” might be the single most uttered writing maxim.

Most fiction is full of an author’s story, whether real life is cast through a fictional lens or in the themes, motifs and conflicts that preoccupy the writer.

Aristotle said that the secret to moving the passions in others is to be moved oneself.

Above: Bust of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

Moving oneself is made possible by bringing to the fore the visions and experiences of one’s life.

“Write what you know” does not instruct you to put your life directly on the page, but rather to take the rich mulch of your experience and let stories grow from it in other forms.

As Saul Bellow said:

“Fiction is the higher autobiography.“

Above: Canadian- American writer Saul Bellow (né Solomon Bellows) (1915 – 2005) was a Canadian–American writer

Writing what you know becomes something like a pilgrimage, a chase scene, a dreamscape, a meditation and a scientific experiment all in one.

Don’t shortchange your experiences.

You have a rich life to draw on in your writing.

We have all felt a deep range of emotions, emotions that we can amplify with our imaginations to infuse our stories with the deep truths of life.

Write who you are.

Write what you know.

Write what you need to know.

A diary is a way to explore who you are.

Just keep writing.

He’s a real nowhere man

Sitting in his nowhere land

Making all his nowhere plans for nobody

Doesn’t have a point of view

Knows not where he’s going to

Isn’t he a bit like you and me?

Nowhere man please listen

You don’t know what you’re missing

Nowhere man, the world is at your command

He’s as blind as he can be

Just sees what he wants to see

Nowhere man, can you see me at all

Nowhere man don’t worry

Take your time, don’t hurry

Leave it all ’til somebody else

Lends you a hand

Ah, la, la, la, la

Doesn’t have a point of view

Knows not where he’s going to

Isn’t he a bit like you and me?

Nowhere man please listen

You don’t know what you’re missing

Nowhere man, The world is at your command

Ah, la, la, la, la

He’s a real nowhere man

Sitting in his nowhere land

Making all his nowhere plans for nobody

Making all his nowhere plans for nobody

Making all his nowhere plans for nobody

(The Beatles, Rubber Soul, 1966)

Sources

- “Nobody“, One Trick Pony, Paul Simon, 1980

- “Nowhere Man“, Rubber Soul, The Beatles, 1966

- Pep Talks for Writers, Grant Faulkner

- The Assassin’s Cloak: An Anthology of the World’s Greatest Diarists, edited by Irene and Alan Taylor