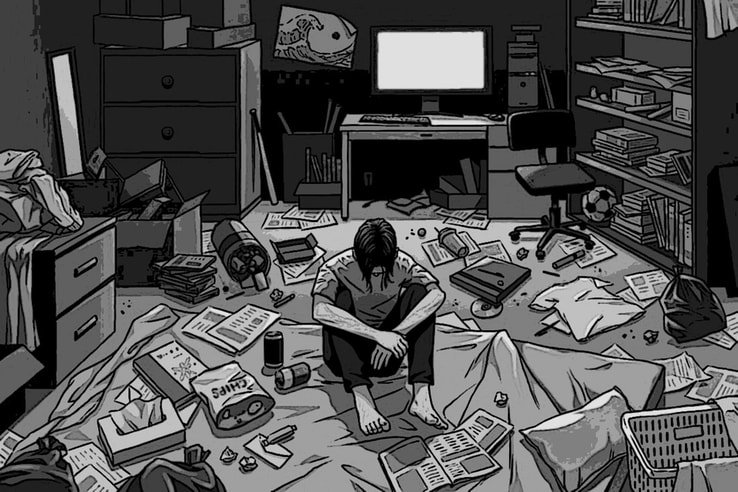

Hikikomori (Japanese):

Total withdrawal from society

Fujimaki:

“I have been suffering from this disabling social phobia for many years and I am still struggling in my recovery.

After receiving six months of therapy, I am gradually trying to reintegrate into society, but I am still pretty reclusive.

When I think back, I realize that even before I started school, I had had a tendency to isolate myself and had been more comfortable staying at home than going places.

However, the problem started to escalate during my high school education.

The pressure to be successful was disabling.

The only topics of conversation in our home became school, exams and my future career.

In order to avoid reality, I began to cut myself off from my family by spending more and more time alone in my room.

When questioned about this by my mother or brothers, I just blamed the exams.

My parents couldn’t understand what was happening to me.

They were expecting me to become a successful lawyer like my father, but after a while, they stopped trying to coerce me out of my room.

As I began to spend more and more time in seclusion, I started to experience overwhelming feelings of panic just at the thought of having to go somewhere.

During the times that I did go out, I suffered from extreme self-consciousness.

Before my problems began, I had been one of the top students in my class, but later when I had to sit at my exams, I couldn’t write a word, because I was convinced that everyone was looking at me.

I don’t believe hikikomori is a predominantly Japanese phenomenon.

It is perhaps given different labels in other countries, but it is definitely present in other societies.

Japanese society does however, play a strong role in the nurturing of this lifestyle and more needs to be done to help those suffering from this problem.”

Above: Flag of Japan

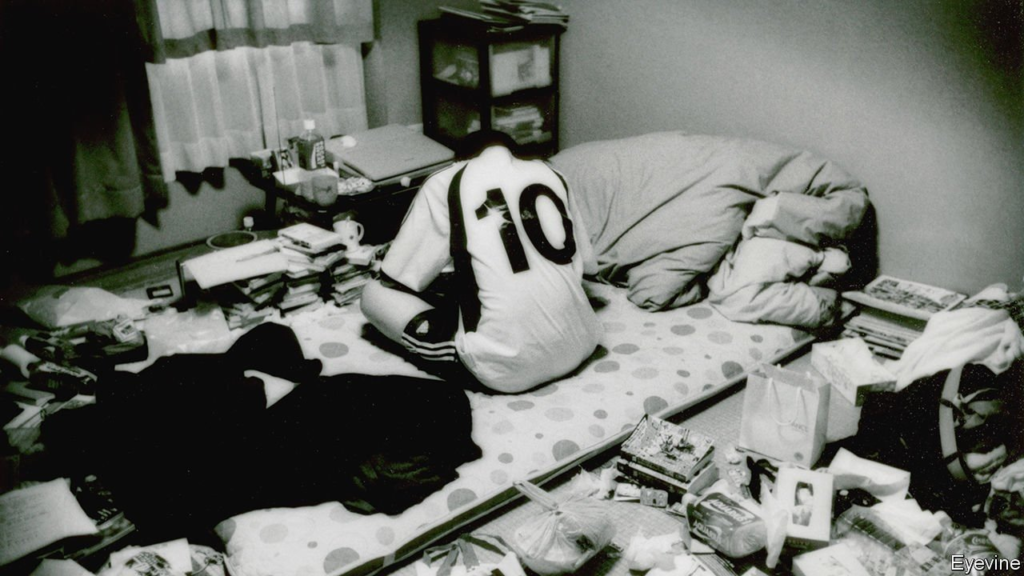

Yatsuhiro:

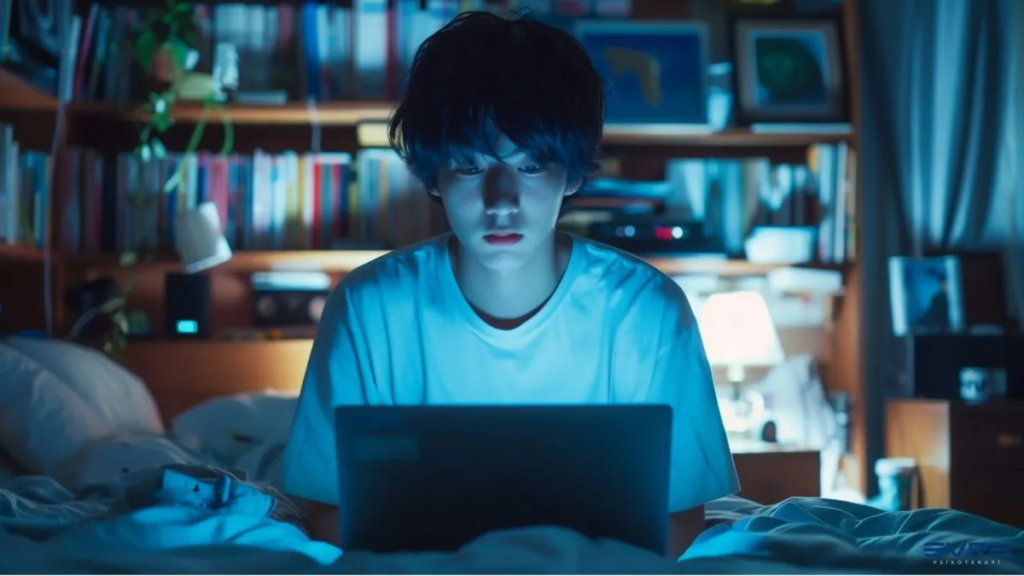

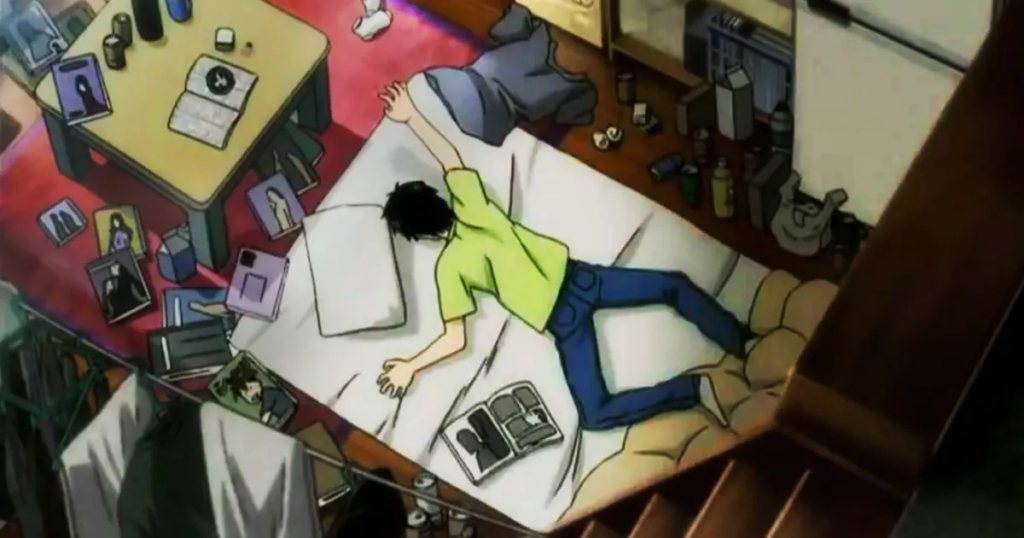

“Until a few months ago, I had spent nearly five years isolated from the world as a hikikomori.

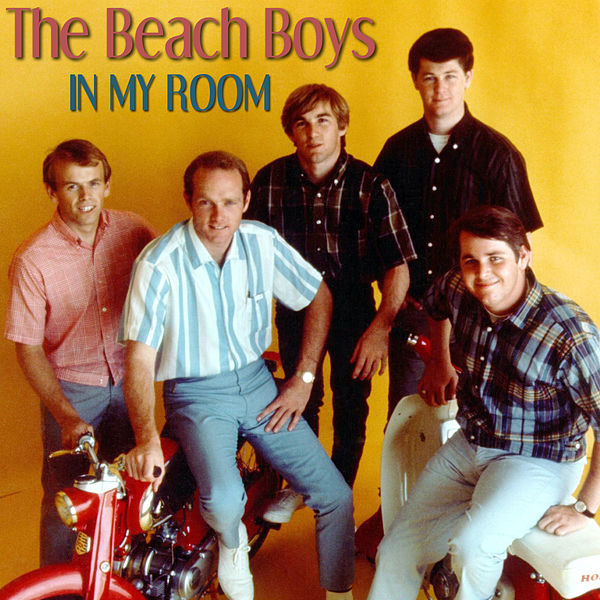

For those five years my world consisted of my bedroom.

I only felt safe when I was alone in my room.

I knew it was abnormal, but I didn’t want to change.

It was easy to shut myself away, because I had as much entertainment as I could want via the Internet.

I would read and play computer games all night long, then sleep during the day, sneaking out of my room at night to go find food in the kitchen.

During my high school years, I was doing well in school and studying night and day to get the grades I needed to go to one of the leading universities, but then my world fell apart when I failed my exams.

The shame and embarrassment I was feeling led me to isolate myself from the world.

I couldn’t bear to face people, not even my family, so I just stayed in my room.

My mother had always been overprotective, so she never forced me to go outside and face my fears.

The longer I stayed in my room, the harder it became to go outside.

It was finally my brother who forced me to seek help.

He had been watching a TV documentary about hikikomori, when he realized how serious my condition was.

At the end of the documentary, a helpline number was given.

After building up the courage to contact this group and with my brother’s encouragement, I began to receive help.

Now, after six months of therapy, I am making slow but steady progress.

Before I began therapy, just speaking to other people had been a challenge, but now I am starting to go shopping.

It takes time to rebuild trust and confidence.

Sometimes I feel hopeless, but step by step I am beating this affliction.

There are many more boys and young men like me in Japan who have become hikikomori as a result of the social pressures in my culture.”

Ruriko:

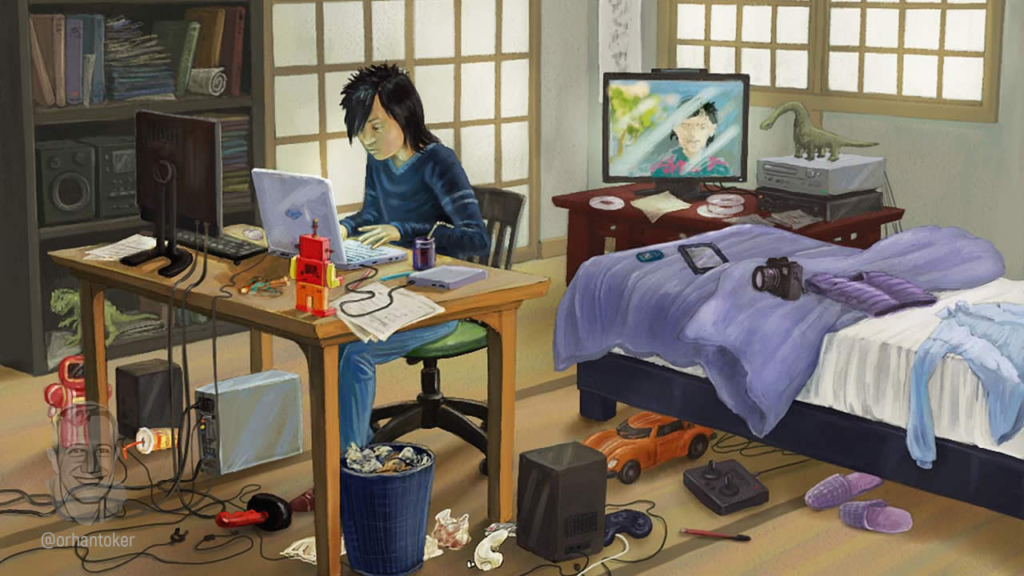

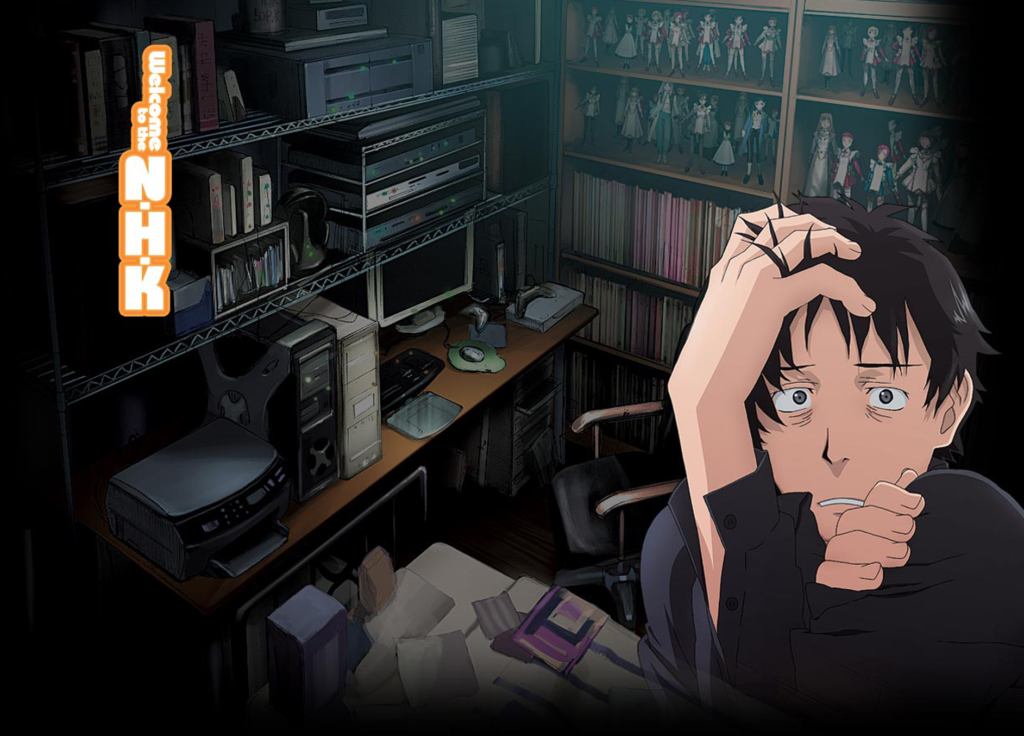

“Hikikomori, which literally means ‘pulling inwards’ in Japanese, is a term used to describe young people, generally males, who demonstrate extreme social withdrawal.

The term itself can be used to refer to the individual or to the lifestyle.

According to official government statistics, the number of sufferers is at least 700,000, but other sources estimate that the actual number could in fact be much higher.

In the past, the official standpoint had been that Hikikomori did not exist.

The Hikikomori remained undetected and ignored by Japanese society.

Above: National Seal of Greater Japan

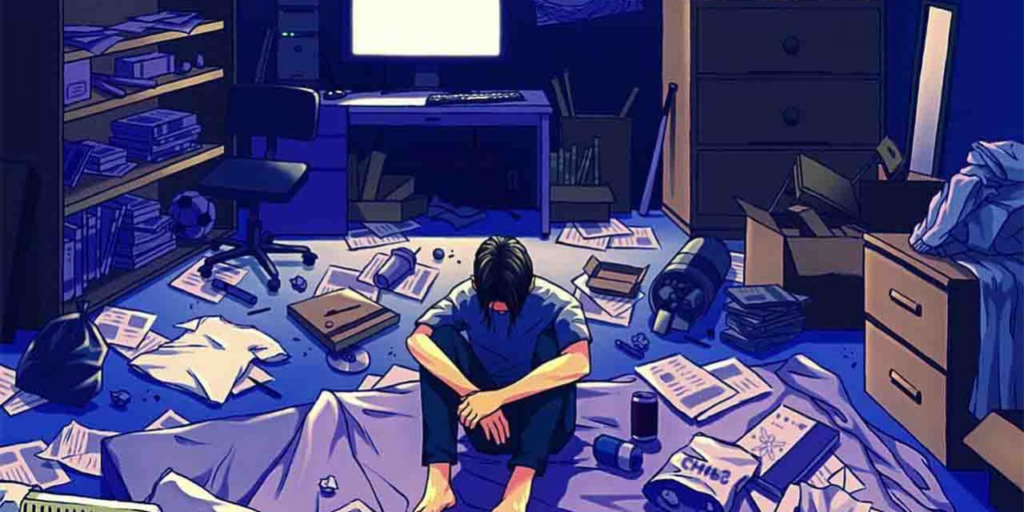

Hikikomori is characterized by a complete withdrawal from society.

Most sufferers confine themselves to their apartments or homes and avoid all social contact for a period of at least six months.

Most sufferers are young and male.

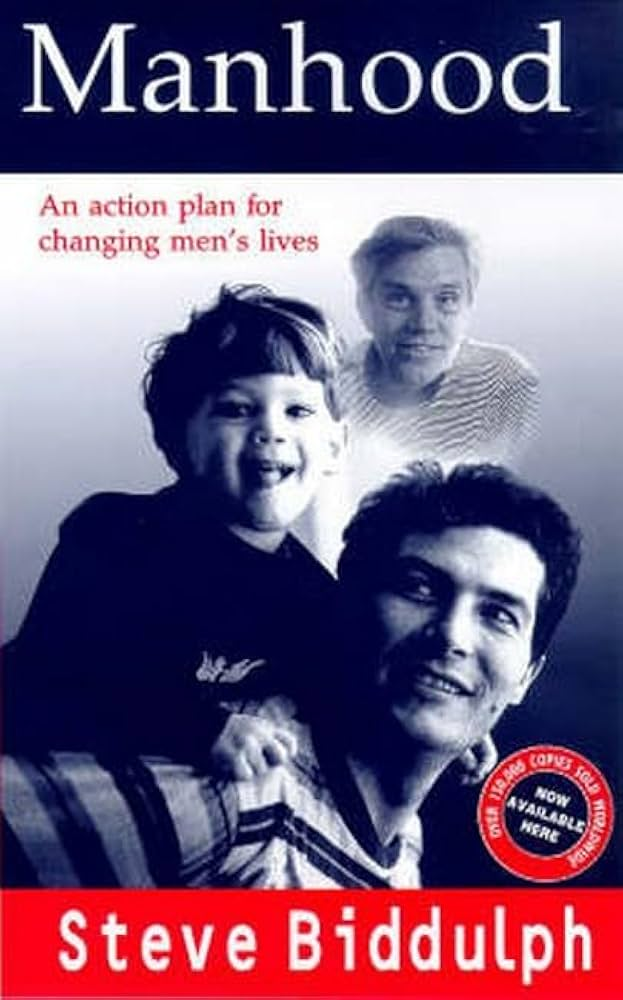

Why mostly men?

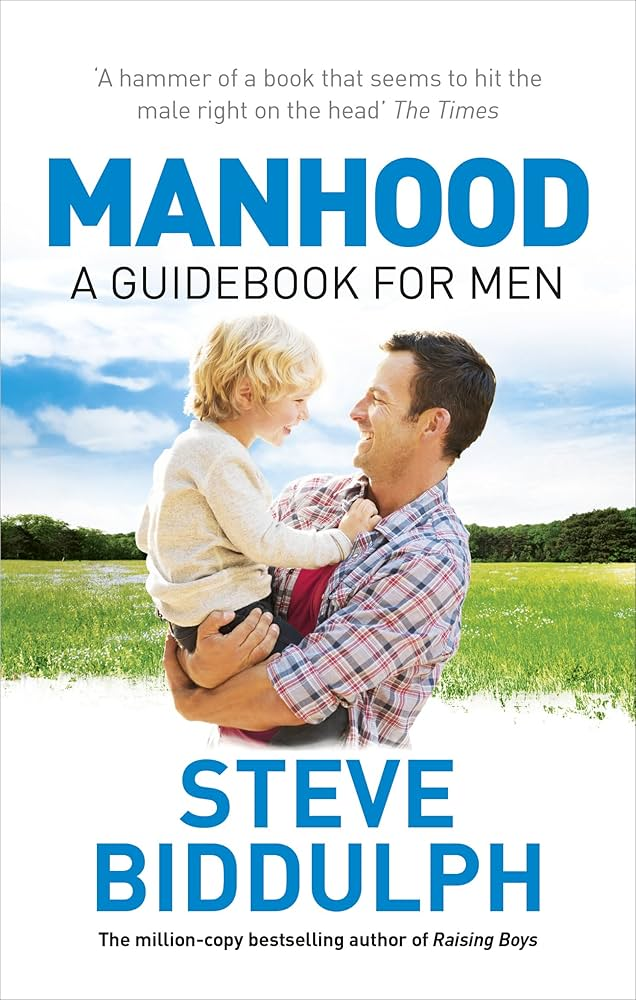

Most men don’t have a life.

Instead, we have just learned to pretend.

Much of what men do is an outer show, kept up for protection.

Most women today are not like this.

They act from inner feeling and spirit.

More and more they know who they are and what they want.

Little children of both sexes start out well.

They are alive to themselves, expecting to be joyful, expecting Life to be an adventure.

But a boy’s spirit begins to shrivel very early in life, until (often as not) he loses touch with it completely.

By the time he becomes a man, he is like a tiger raised in a zoo – confused and numb, with huge energies untapped.

He feels that there must be more, but does not know what that more is.

So he spends his life pretending to be happy – to himself, his friends and his family.

Sometimes there is a breakthrough in this pretense.

Sometimes men get a taste of what Life could be like or experience moments of real passion and glory in being alive.

It can happen in surprising ways – surviving an accident, finding yourself alone on a stretch of beach, having a certain kind of moment with a woman, being reunited with your children after time apart.

We glimpse something, unsettling but beautiful.

And then the moment passes.

We don’t know how to bring it back.

The sheer intensity just serves to frighten us, upsets the charade we have constructed as a stage set for our lives.

Not sure what to do, we quickly go back to pretending everything is OK.

We pretend and we wait and we hope things will improve.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

What a piece of work is a man!

How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty!

In form and moving how express and admirable!

In action how like an angel,

in apprehension how like a god!

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

Men are hurting.

They are also hurting others.

Men are a mess.

The terrible effects on our marriages, fathering abilities, our health and our leadership skills are a matter of public record.

Our marriages fail.

Our kids hate us.

We die from stress.

And on the way we destroy the world.

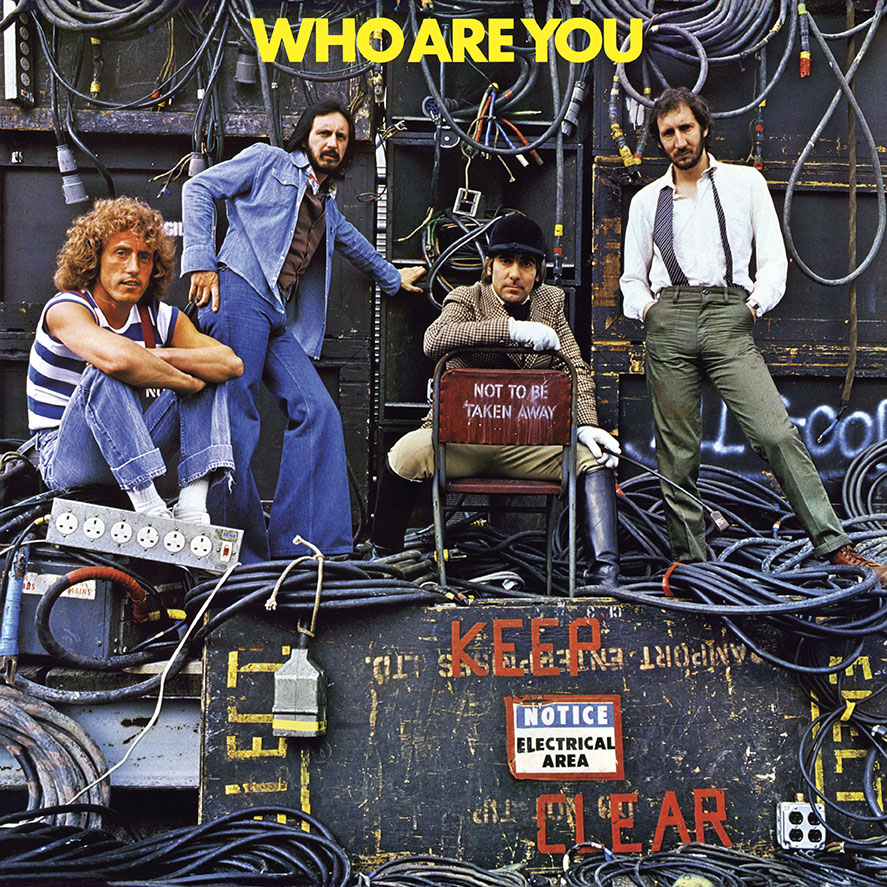

Above: James Brown, “This is a Man’s World“

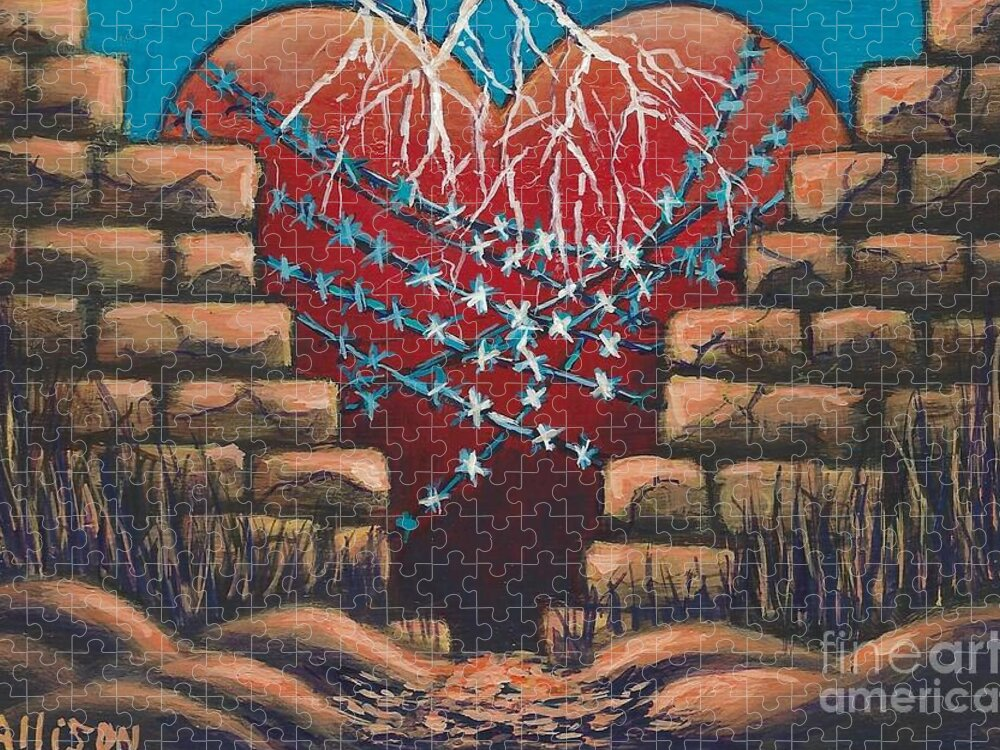

Women have had to overcome oppression, but men’s difficulties are with isolation.

The enemies, the prisons, from which men must escape, are:

- loneliness

- compulsive competition

- lifelong emotional timidity

Women’s enemies are largely in the world around them.

Men’s enemies are often on the inside – in the walls we put up around our hearts.

Certain aspects of Japanese culture help to foster this complaint.

For example, the extreme pressures of the Japanese education system added to a cultural phenomenon known as ‘sekentie’ in Japanese are contributing factors.

Sekentie refers to a high awareness of personal reputation and social standing, which places enormous pressure on young men to achieve success.

Unfortunately, this problem is compounded by parents’ resistance to seek help as a result of their preoccupation with the family’s social standing.

In other words, the family feels ashamed of the condition and fears the stigma associated with failure.

Another aspect of Japanese society which contributes to the high incidence of hikikomori is ‘amae’, which refers to the extreme dependence of Japanese youth on their parents.

In Japanese socıety, it is the norm for young people to remain living in the family home until they get married.

Many parents are overprotective and would prefer their unmarried offspring to stay at home than to embrace the outside world.

As a result, those falling into the hikikomori lifestyle are not encouraged to deal with their social withdrawal.

Although the condition is now officially recognized, much still needs to be done to reach those young people who have been ignored by Japanese society until now.”

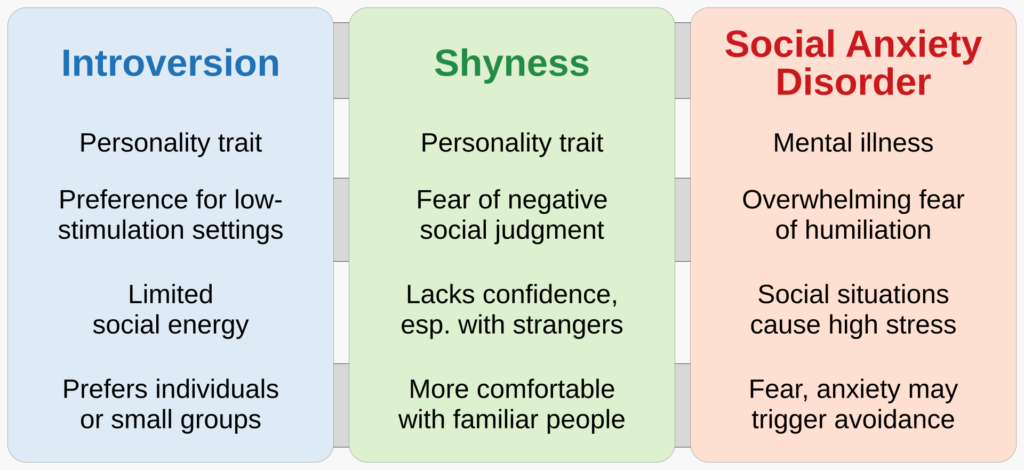

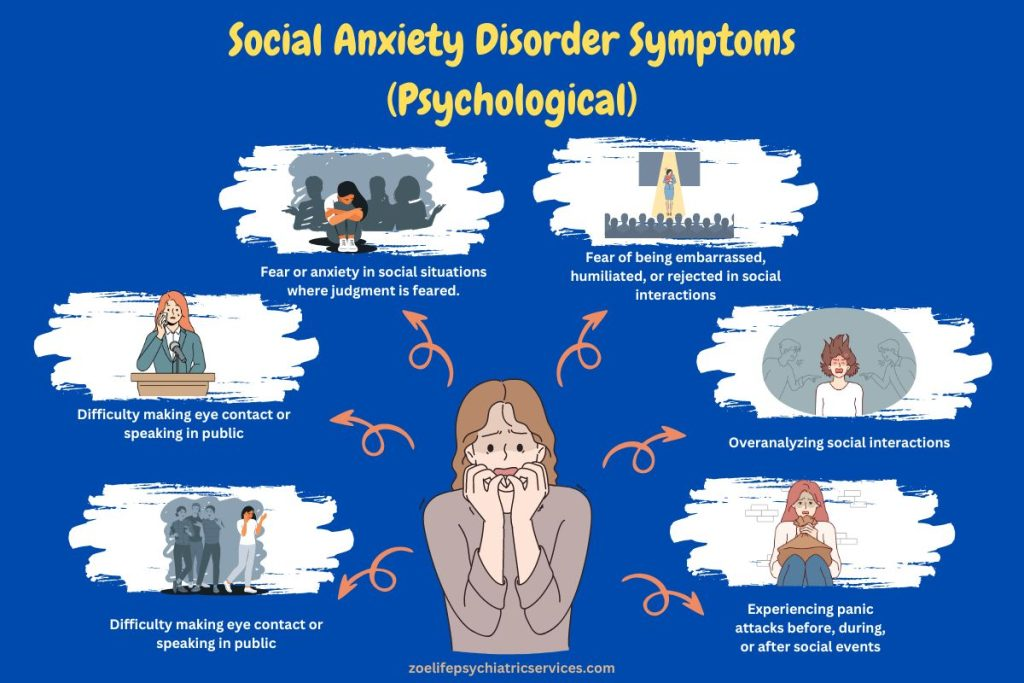

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), also known as social phobia, is an anxiety disorder characterized by sentiments of fear and anxiety in social situations, causing considerable distress and impairing ability to function in at least some aspects of daily life.

These fears can be triggered by perceived or actual scrutiny from others.

Individuals with social anxiety disorder fear negative evaluations from other people.

Physical symptoms often include excessive blushing, excessive sweating, trembling, palpitations, rapid heartbeat, muscle tension, shortness of breath and nausea.

Stammering may be present, along with rapid speech.

Panic attacks can also occur under intense fear and discomfort.

Some affected individuals may use alcohol or other drugs to reduce fears and inhibitions at social events.

It is common for those with social phobia to self-medicate in this fashion, especially if they are undiagnosed, untreated, or both.

This can lead to alcohol use disorder, eating disorders or other kinds of substance use disorders.

SAD is sometimes referred to as an illness of lost opportunities where “individuals make major life choices to accommodate their illness“.

According to the International Classification of Diseases guidelines, the main diagnostic criteria of social phobia are fear of being the focus of attention, or fear of behaving in a way that will be embarrassing or humiliating, avoidance and anxiety symptoms.

Standardized rating scales can be used to screen for social anxiety disorder and measure the severity of anxiety.

The first line of treatment for social anxiety disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Medications such as SSRIs are effective for social phobia, especially paroxetine.

Above: Paroxetine is an antidepressant used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

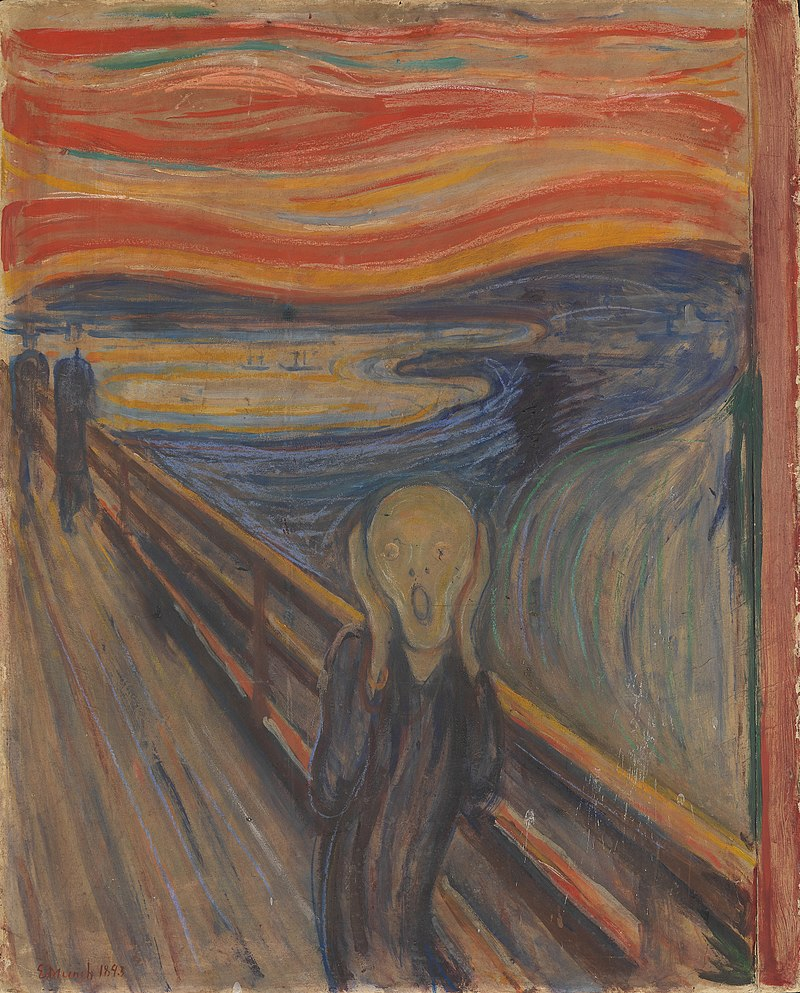

Above: The Scream, Edvard Munch (1893)

It has also been used in the treatment of premature ejaculation and hot flashes due to menopause.

It is taken orally (by mouth).

Common side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating, trouble sleeping, and sexual dysfunction.

Serious side effects may include suicidal thoughts in those under the age of 25, serotonin syndrome, and mania.

While the rate of side effects appears similar compared to other SSRIs (Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and SNRIs (Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), antidepressant discontinuation syndrome may occur more often.

Use in pregnancy is not recommended, while use during breastfeeding is relatively safe.

It is believed to work by blocking the reuptake of the chemical serotonin by neurons in the brain.

Paroxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1992 and initially sold by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

It is on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) List of Essential Medicines.

It is available as a generic medication.

In 2022, it was the 92nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 7 million prescriptions.

In 2018, it was in the top 10 of most prescribed antidepressants in the United States.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

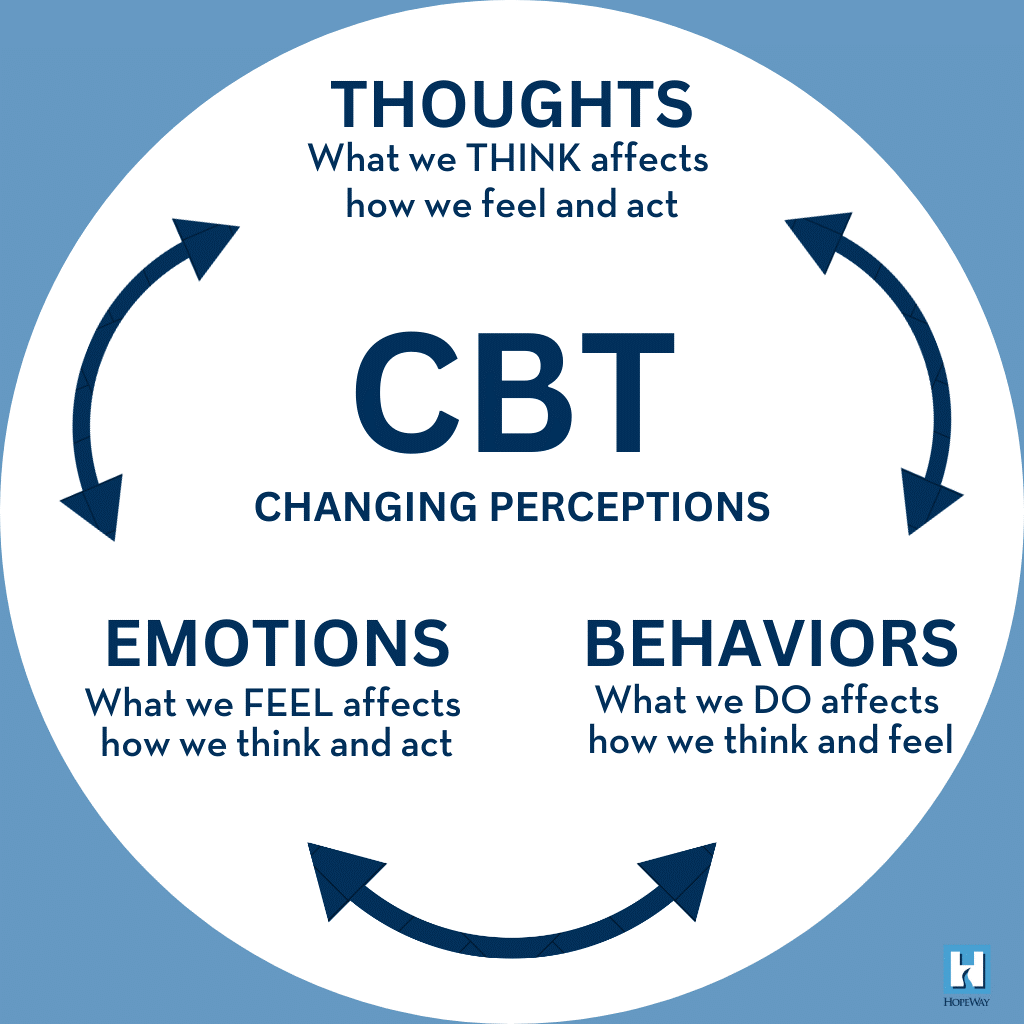

CBT is effective in treating this disorder, whether delivered individually or in a group setting.

The cognitive and behavioral components seek to change thought patterns and physical reactions to anxiety-inducing situations.

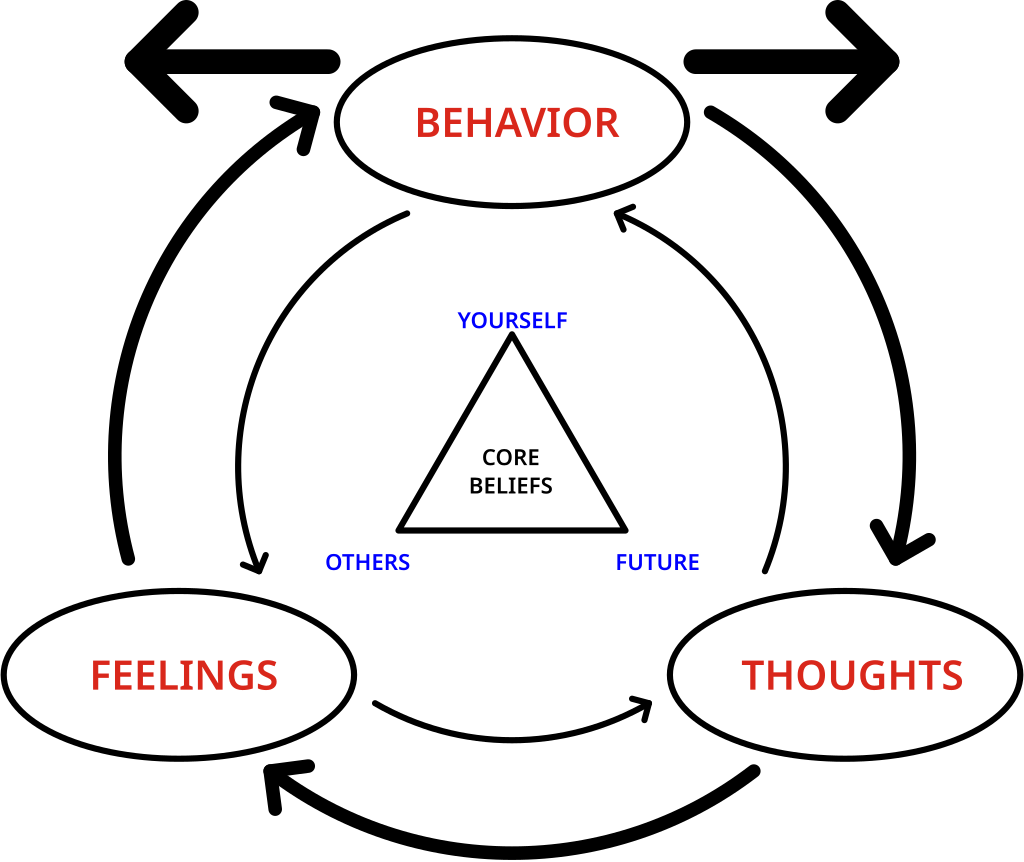

Above: The diagram depicts how feelings, thoughts, and behaviors all influence each other.

The triangle in the middle represents CBT’s tenet that all humans’ core beliefs can be organized using three categories: self, others, future.

The attention given to social anxiety disorder has significantly increased since 1999 with the approval and marketing of drugs for its treatment.

Prescribed medications include several classes of antidepressants:

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

Other commonly used medications include beta blockers and benzodiazepines.

Above: The Lady Apothecary, Alfred Jacob Miller (1850)

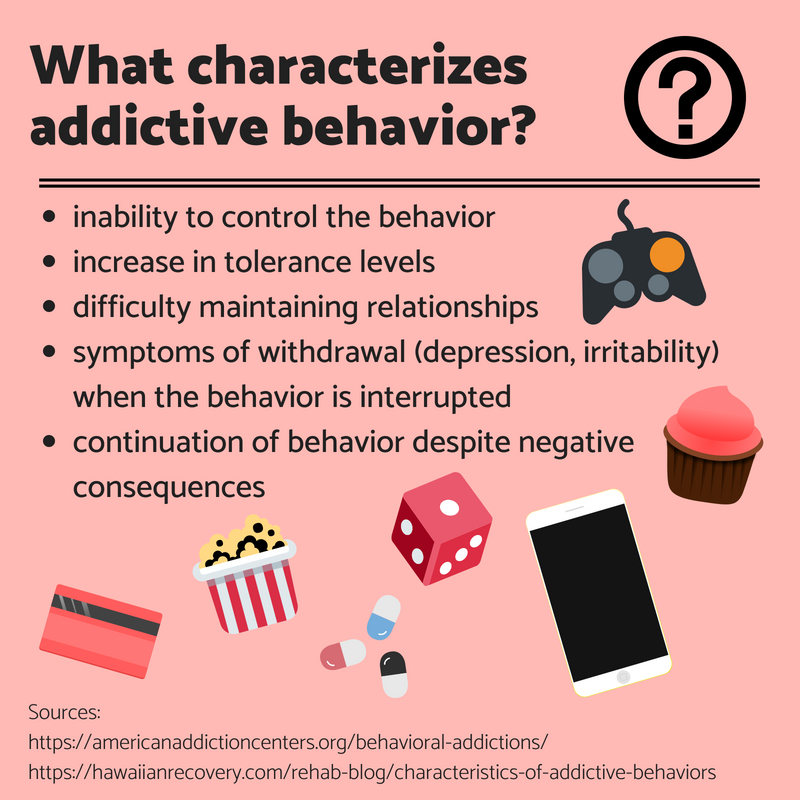

The World Council of Anxiety does not recommend benzodiazepines for the long-term treatment of anxiety due to a range of problems associated with long-term use including:

- tolerance

- psychomotor impairment

- cognitive and memory impairments

- physical dependence

- a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome upon discontinuation of benzodiazepines.

Despite increasing focus on the use of antidepressants and other agents for the treatment of anxiety, benzodiazepines have remained a mainstay of anxiolytic pharmacotherapy due to their robust efficacy, rapid onset of therapeutic effect, and generally favorable side effect profile.

Treatment patterns for psychotropic drugs appear to have remained stable over the past decade, with benzodiazepines being the most commonly used medication for panic disorder.

People with SAD avoid situations that most people consider normal.

They may have a hard time understanding how others can handle these situations so easily.

People with SAD avoid all or most social situations and hide from others, which can affect their personal relationships.

Social phobia can completely remove people from social situations due to the irrational fear of these situations.

People with SAD may be addicted to social media networks, have sleep deprivation, and feel good when they avoid human interactions.

SAD can also lead to low self-esteem, negative thoughts, major depressive disorder, sensitivity to criticism, and poor social skills that do not improve.

People with SAD experience anxiety in a variety of social situations, from important, meaningful encounters, to everyday trivial ones.

These people may feel more nervous in job interviews, dates, interactions with authority, or at work.

In March 2019, the International Journal of Adolescence and Youth published a systematic review of 13 studies comprising 21,231 adolescent subjects aged 13 to 18 years that found that social media screen time, both active and passive social media use, the amount of personal information uploaded, and social media addictive behaviors all correlated with anxiety.

In February 2020, Psychiatry Research published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies that found positive associations between problematic smartphone use and anxiety and positive associations between higher levels of problematic smartphone use and elevated risk of anxiety.

Meanwhile, Frontiers in Psychology published a systematic review of 10 studies of adolescent or young adult subjects in China that concluded that the research reviewed mostly established an association between social networks use disorder and anxiety among Chinese adolescents and young adults.

Above: Flag of the People’s Republic of China

In September 2023, Frontiers in Public Health published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 studies comprising 36,013 subjects aged 14 to 24 years that found a positive and statistically significant association between problematic internet use and social anxiety.

Meanwhile, the British Journal of Psychiatry published a systematic review of 140 studies published from 2000 through 2020 found that social media use for more than three hours per day and passive browsing was associated with increased anxiety.

In January 2024, the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication published a meta-analysis of 141 studies comprising 145,394 subjects that found that active social media use was associated with greater symptoms of anxiety and passive social media use was associated with greater symptoms of social anxiety.

In February 2024, Addictive Behaviors published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 53 studies comprising 59,928 subjects that found that problematic social media use and social anxiety are highly and positively correlated.

Meanwhile, The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery published a systematic review of 15 studies researching associations between problematic social media use and anxiety in subjects from the Middle East and North Africa (including 4 studies with subjects exclusively between the ages of 12 and 19 years) that established that most studies found a significant association.

Above: Flag of the Arab Republic of Egypt

Research into the causes of social anxiety and social phobia is wide-ranging, encompassing multiple perspectives from neuroscience to sociology.

Scientists have yet to pinpoint the exact causes.

Studies suggest that genetics can play a part in combination with environmental factors.

Social phobia is not caused by other mental disorders or substance use.

Generally, social anxiety begins at a specific point in an individual’s life.

This will develop over time as the person struggles to recover.

Eventually, mild social awkwardness can develop into symptoms of social anxiety or phobia.

Passive social media usage may cause social anxiety in some people.

A previous negative social experience can be a trigger to social phobia, perhaps particularly for individuals high in “interpersonal sensitivity“.

For around half of those diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, a specific traumatic or humiliating social event appears to be associated with the onset or worsening of the disorder.

This kind of event appears to be particularly related to specific social phobia, for example, regarding public speaking.

As well as direct experiences, observing or hearing about the socially negative experiences of others (e.g. a faux pas committed by someone), or verbal warnings of social problems and dangers, may also make the development of a social anxiety disorder more likely.

Social anxiety disorder may be caused by the longer-term effects of not fitting in, or being bullied, rejected, or ignored.

Shy adolescents or avoidant adults have emphasized unpleasant experiences with peers or childhood bullying or harassment.

In one study, popularity was found to be negatively correlated with social anxiety, and children who were neglected by their peers reported higher social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation than other categories of children.

Socially phobic children appear less likely to receive positive reactions from peers, and anxious or inhibited children may isolate themselves.

Cultural factors that have been related to social anxiety disorder include a society’s attitude towards shyness and avoidance, affecting the ability to form relationships or access employment or education, and shame.

One study found that the effects of parenting are different depending on the culture:

American children appear more likely to develop social anxiety disorder if their parents emphasize the importance of others’ opinions and use shame as a disciplinary strategy, but this association was not found for Chinese/Chinese-American children.

In China, research has indicated that shy-inhibited children are more accepted than their peers and more likely to be considered for leadership and considered competent, in contrast to the findings in Western countries.

Purely demographic variables may also play a role.

Problems in developing social skills, or ‘social fluency‘, may be a cause of some social anxiety disorder, through either inability or lack of confidence to interact socially and gain positive reactions and acceptance from others.

The studies have been mixed, however, with some studies not finding significant problems in social skills while others have.

What does seem clear is that the socially anxious perceive their own social skills to be low.

It may be that the increasing need for sophisticated social skills in forming relationships or careers, and an emphasis on assertiveness and competitiveness, is making social anxiety problems more common, at least among the ‘middle classes‘.

An interpersonal or media emphasis on ‘normal‘ or ‘attractive‘ personal characteristics has also been argued to fuel perfectionism and feelings of inferiority or insecurity regarding negative evaluation from others.

The need for social acceptance or social standing has been elaborated in other lines of research relating to social anxiety.

Research has indicated the role of ‘core‘ or ‘unconditional‘ negative beliefs (e.g. “I am inept.”) and ‘conditional‘ beliefs nearer to the surface (e.g. “If I show myself, I will be rejected.”).

They are thought to develop based on personality and adverse experiences and to be activated when the person feels under threat.

Recent research has also highlighted that conditional beliefs may also be at play (e.g., “If people see I’m anxious, they’ll think that I’m weak.”).

A secondary factor is self-concealment which involves concealing the expression of one’s anxiety or its underlying beliefs.

One line of work has focused more specifically on the key role of self-presentational concerns.

The resulting anxiety states are seen as interfering with social performance and the ability to concentrate on interaction, which in turn creates more social problems, which strengthens the negative schema.

Also highlighted has been a high focus on and worry about anxiety symptoms themselves and how they might appear to others.

A similar model emphasizes the development of a distorted mental representation of the self and overestimates of the likelihood and consequences of negative evaluation, and of the performance standards that others have.

Such cognitive-behavioral models consider the role of negatively biased memories of the past and the processes of rumination after an event, and fearful anticipation before it.

Studies have also highlighted the role of subtle avoidance and defensive factors, and shown how attempts to avoid feared negative evaluations or use of “safety behaviors” can make social interaction more difficult and the anxiety worse in the long run.

This work has been influential in the development of cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder, which has been shown to have efficacy.

The first-line treatment for social anxiety disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), with medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) used only in those who are not interested in therapy.

According to research studies, combining the use of CBT with escitalopram (a type of SSRI) in contrast to using CBT with a placebo reduced anticipatory speech-state anxiety and increased reductions of social anxiety symptoms, revealing the potential of combining various treatment methods.

Self-help based on principles of CBT is a second-line treatment.

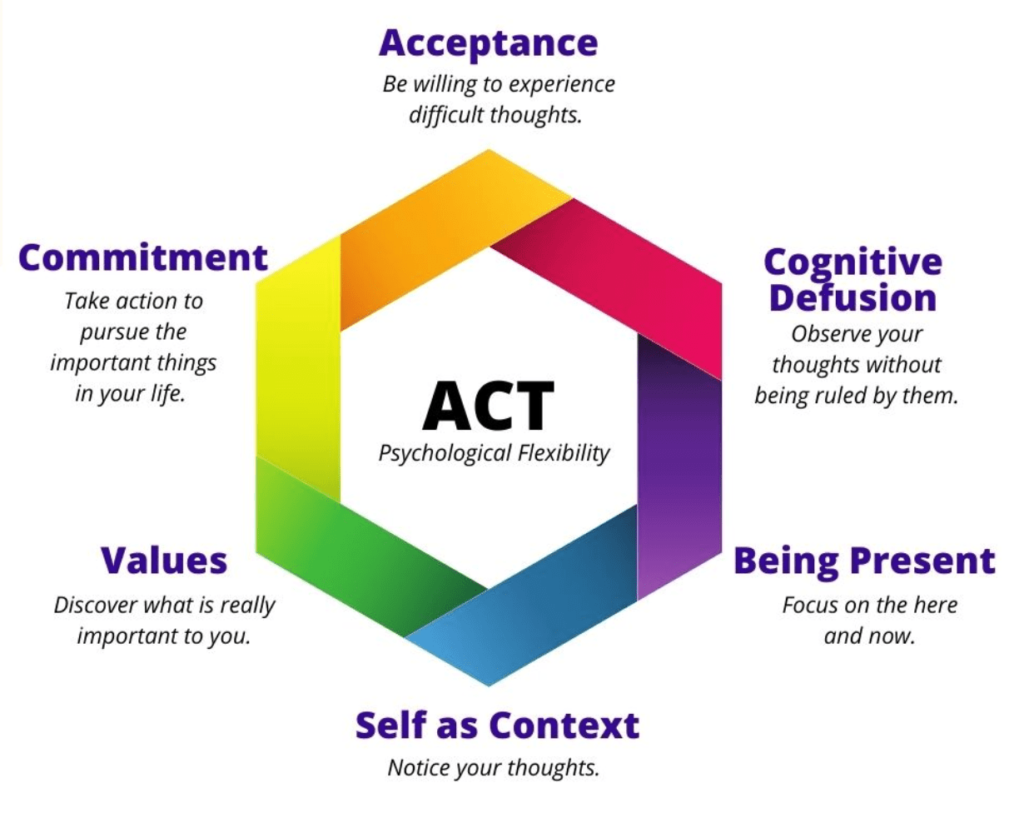

There is some emerging evidence for the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in the treatment of social anxiety disorder.

ACT is considered an offshoot of traditional CBT and emphasizes accepting unpleasant symptoms rather than fighting against them, as well as psychological flexibility – the ability to adapt to changing situational demands, to shift one’s perspective, and to balance competing desires.

ACT may be useful as a second line treatment for this disorder in situations where CBT is ineffective or refused.

Some studies have suggested social skills training (SST) can help with social anxiety.

Examples of social skills focused on during SST for social anxiety disorder include:

- initiating conversations

- establishing friendships

- interacting with members of the preferred sex

- constructing a speech and assertiveness skills.

However, it is not clear whether specific social skills techniques and training are required, rather than just support with general social functioning and exposure to social situations.

There is some evidence that expressive therapies (e.g. painting, drawing or musical therapy) can be effective for treating social anxiety disorder in certain contexts.

A 2019 study, for example, found that art therapy produced an “increase in subjective quality of life (both with large effects) and an improvement in accessibility of emotion regulation strategies” in adult women with anxiety.

Both the Visual Arts and Galleries Association (VAGA) and the American Art Therapy Association run specific workshops for social anxiety disorder.

Furthermore, error-related brain activity varies in accordance to factors that affect the motivational significance of behavioral performance, such as social contexts and personality traits, suggesting that understanding how individuals appraise the relevance of incentives in a given context is crucial for designing interventions to ameliorate or prevent maladaptive patterns of performance evaluation, particularly with regards to social anxiety disorder and substance abuse.

Given the evidence that social anxiety disorder may predict subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders such as depression, early diagnosis and treatment is important.

Social anxiety disorder remains under-recognized in primary care practice, with patients often presenting for treatment only after the onset of complications such as clinical depression or substance use disorders.

Let me preface what you are about to read with an advisory warning.

Your humble blogger is not a medical nor psychological expert or professional.

I have absolutely no educational background or much experience in medicine or psychology other than second-hand encounters, at best.

I am simply a 59-year-old Canadian man teaching English to adults in Türkiye.

This does NOT make me an authority in these matters.

I am merely a man with opinions, which, to be fair, can be taken with whatever relevance you wish to give them.

Above: Your humble blogger

I do not want to suggest that sufferers of social anxiety should seek or avoid professional help.

Being ignorant of the effects of the aforementioned medications, I am hesitant to advocate or reject their use for the simple reason that I believe that every person’s body chemistry is unique and that there may be a chance, perhaps only a small chance, that introducing drugs into a body that may already be chemically unwell could compound a person’s problems with other difficulties.

As I said, I am not an expert.

I am simply saying that I feel nervous on the topic of medication.

I am not against cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

I am not an expert on all the particulars involved with CBT or ACT, but I believe that they both involve the afflicted speaking with others about how they are afflicted.

I believe that a conversation with the unwell is necessary, despite the possible mutual discomfort inherent in this endeavor.

Ignoring a problem hoping it will simply heal itself is folly.

Talking about a problem and actively seeking a solution that the afflicted can live with may be a good first step in their healing.

Conversation is the first step.

It needs to be established that there is a desire in the afflicted to seek happiness beyond their present circumstances.

There needs to be a willingness to change, despite the fear that is often associated with change.

I think that social skills training (SST) can help with social anxiety.

I think the introduction of SST should begin with parenting and in schools.

Once the desire is there then I believe that the next step is to encourage healing through the changing of thought patterns and habitual behaviours.

The afflicted need to learn how to help themselves.

I believe expressive therapies (e.g. writing, painting, drawing or music) can be effective not only for treating social anxiety disorder but for everyone.

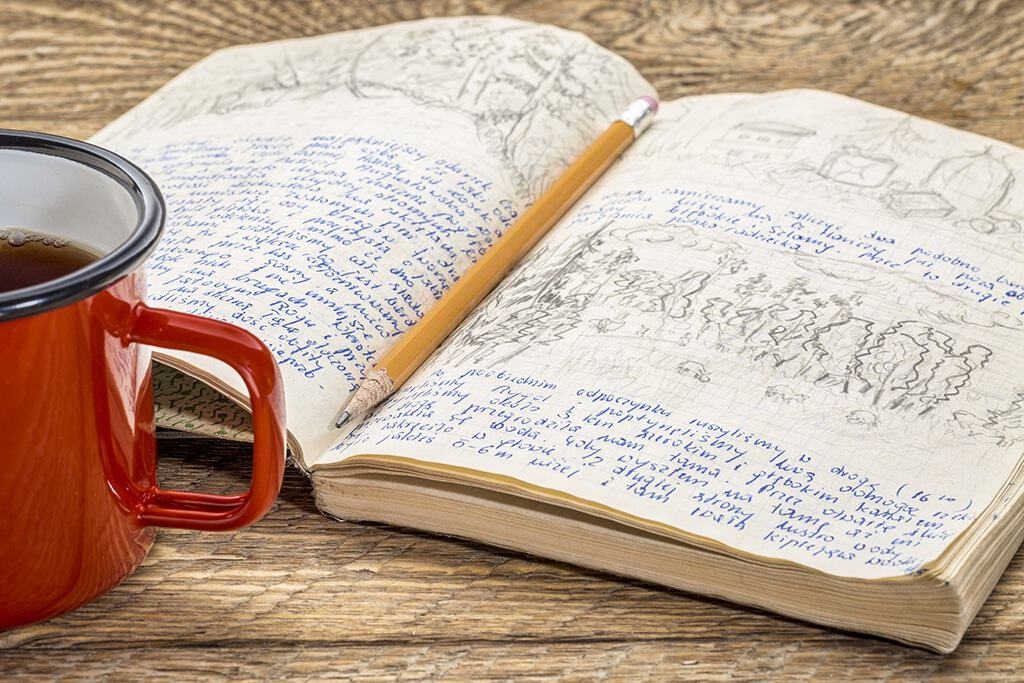

For example, the very effort of composing a few lines about a subject is the best path to understanding it.

There are times when we learn a lesson from something that happened to us or we reach a conclusion about a topic we have been pondering and we make a mental note to keep it in mind, but I am a firm believer that you don’t really know what you are truly thinking or feeling until you express yourself.

Part of the problem is our tendency to engage in unnecessary and unhealthy classifications.

Not only do stereotypes prevent us from evaluating people according to objective criteria, they also influence our relationships and breed conflict.

I think that part of our problems is that we have neglected people in the pursuit of performance.

Results taking precedence over the well-being of those we demand results from.

Performance becomes the overriding goal.

Human relationships are pushed to the back burner.

Team spirit is sacrificed, lying broken and bloody upon the bottom line of the balance sheet.

Civilization dies.

Cliques emerge.

Human dignity no longer matters.

Information is concealed, for a thinking man might have thoughts detrimental to the groupthink.

No one trusts anyone anymore.

Being hikikomori suddenly seems safer, for this is a planet without pity, wherein the only pleasure possible lies in own’s privacy.

Where we fail is in the abandonment for the search for meaning in all that we do, all that we are, all that we can be.

A world-class education should teach us how to acquire expertise and skills applicable anywhere in the world.

The work we relegate ourselves to doing should increase our creativity, help in our self-development and add meaning to our lives.

A good education should not only provide us with the skills needed to do a job, but should also aid us psychologically and socially to live a truly happy existence.

It is not enough to teach others how to acquire knowledge.

We need to teach others how to develop themselves – not only academically and financially, but also psychologically and socially.

We need to teach others how to manage their own personal development, rather than giving them a diploma or a degree than throw them into the deep end of the society pool and hope they instinctively know how to swim.

We need to understand what a person values, how they learn and the kind of situations they thrive in before we judge (or worse, dismiss) them.

We need to encourage them to follow their interests and strengths rather than compel them to follow paths already paved for them.

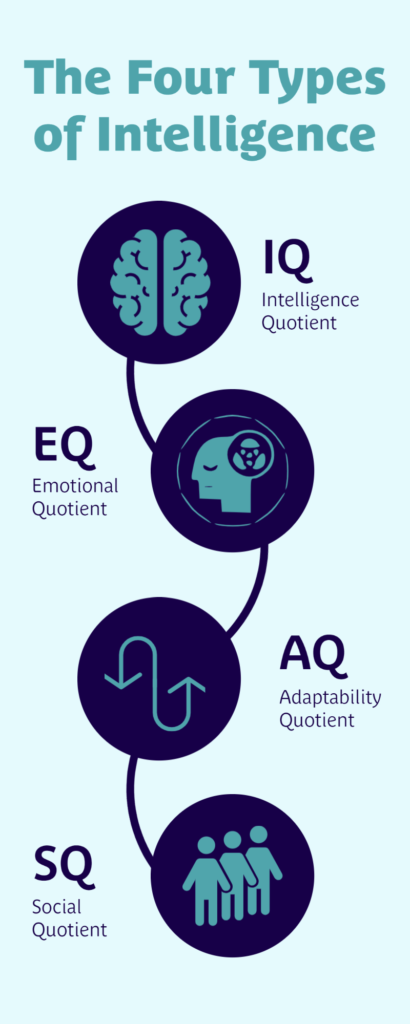

We need to develop not only our intelligence quotient (IQ) (which is not a guarantee of success, merely a potential for success) but as well as our emotional quotient (EQ) – the ability to enrich life by understanding and regulating your emotions and feeling empathy for the emotions of others.

Developing yourself, both your IQ and EQ, begins with reading.

Seek from books what is important, interesting and relevant to you, as an individual.

Read to think better.

Don’t read to just acquire knowledge.

Read to acquire wisdom.

Certainly, general knowledge is essential first and foremost so we can understand what we know, but education should be more than a mere funneling of people into professions and fields of specialization, education should be about a person’s development.

The inherent danger of education is that we lock ourselves into a culture, an ideology, thought patterns or technical fields that cause us to belittle that which is different or outside our experience.

Creating the notion of what is unknown must be unacceptable and unnecessary.

The more superior you think your thought system is, the more you believe it offers the solution to every problem.

As this belief grows stronger, you become trapped in your own world of thought.

You become an ignorant expert.

From: Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982)

The most fundamental precondition for sound decision making is an environment that encourages social debate, where everyone can express their opinion freely.

Insufficient participation can lead the ignorant expert into making boneheaded decisions.

We need to look for people who show curiosity and humility.

They may know a lot, but they acknowledge that there is much still to be learned.

They feel honored and humble if there is something that they know that may help others.

We need to teach perseverance.

We need to encourage passion.

How do we discover passion?

By being curious people.

By believing and living as though everything (and everyone) around us merits our curiosity, our discovery, our analysis, our study, our time and attention.

What interests us and is followed fervently becomes our passion.

Passion combined with perseverance equals success.

We need to balance the need to show others how to do something with the belief in an individual’s innate ingenuity to do what needs to be done if properly motivated and encouraged.

We need to celebrate individuality and reward accomplishments.

We need to encourage others to be creative and take initiative in their work.

We need to listen to their voice and allow them to determine their own destiny, not necessarily the path that we ourselves might prefer.

We need to share information.

We need to support one another.

We need to provide opportunities for socializing in an environment where trust is high and pressure to perform is low.

The mistake that is made with the SAD and the Hikikomori is we do to them what they do to themselves.

We allow them to separate themselves apart from us, thus separating ourselves from those we do not (and believe, cannot) understand.

Part of the solution is to let the afflicted know that they matter to us, that their feelings and individuality matter to us and that belong to the world even if they don’t at present feel that belonging.

I am not suggesting that we suddenly force the introverted into becoming extroverted, but I do feel that we shouldn’t ignore the introverted either.

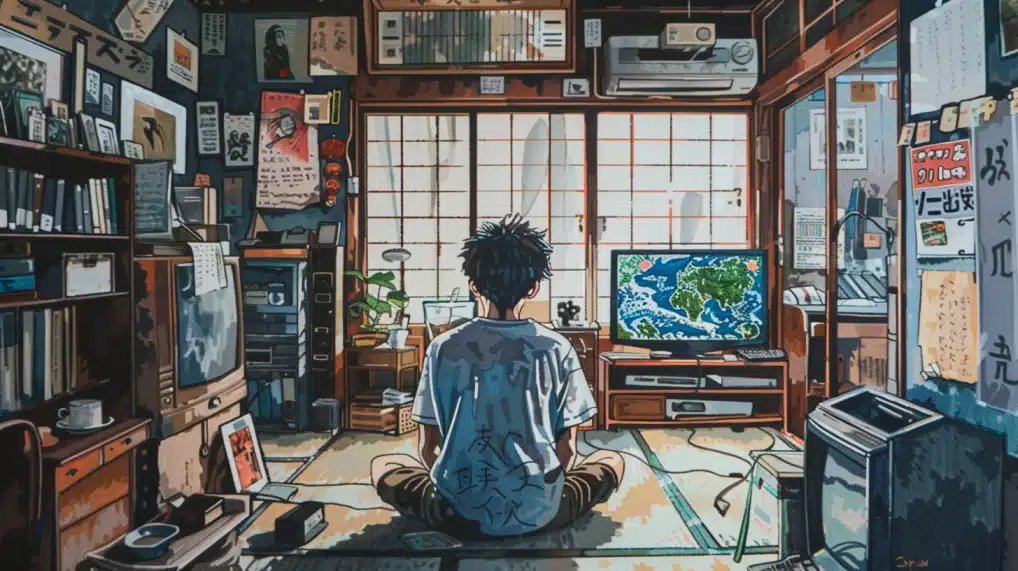

I think that there may be ways to channel the desire for solitude into positive possibilities that may benefit others.

I think simply remaining in one’s room seeking only to entertain and distract oneself from one’s involuntary isolation through the Internet and social media is not the answer.

I am not suggesting that the answer is to suddenly join clubs or begin to haunt bars and nightclubs in a “face your fears” challenge.

I am suggesting that what you choose to do in your solitude matters.

The solitaire could read.

We read to know that we are not alone in the Universe.

We read to know that what we feel and think has been felt and thought by others in their own individual manner of expression.

The solitaire could write.

We write to know what we think and feel.

Perhaps sharing what we think and feel might aid others into thinking and feeling that being merely human is acceptable and even glorious.

We could take a walk.

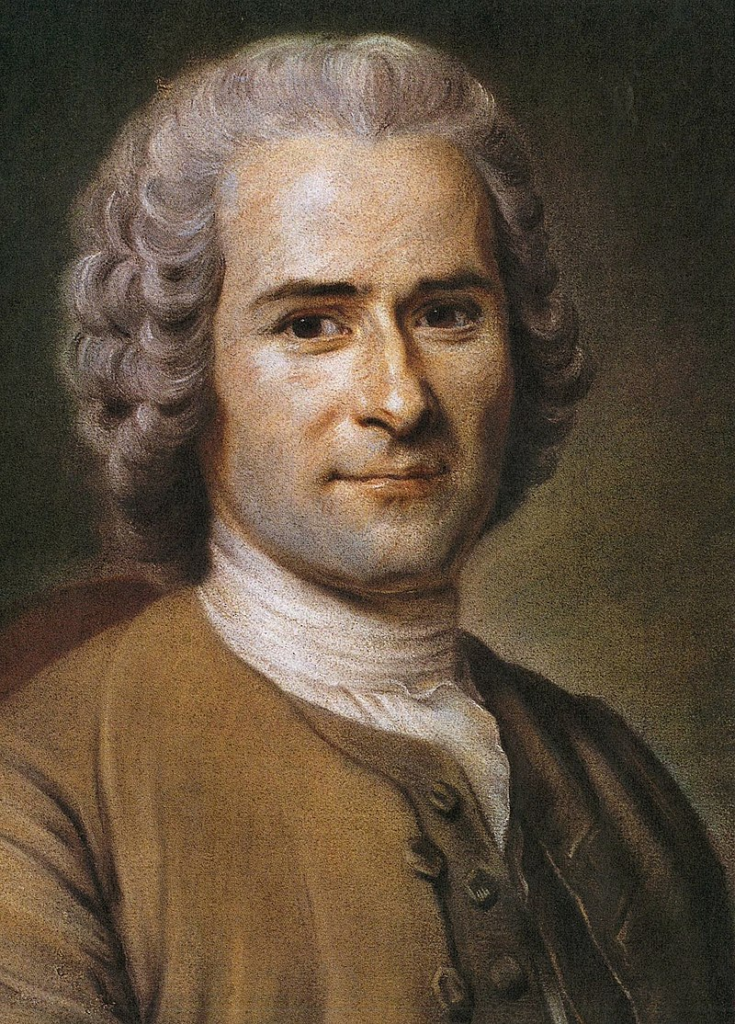

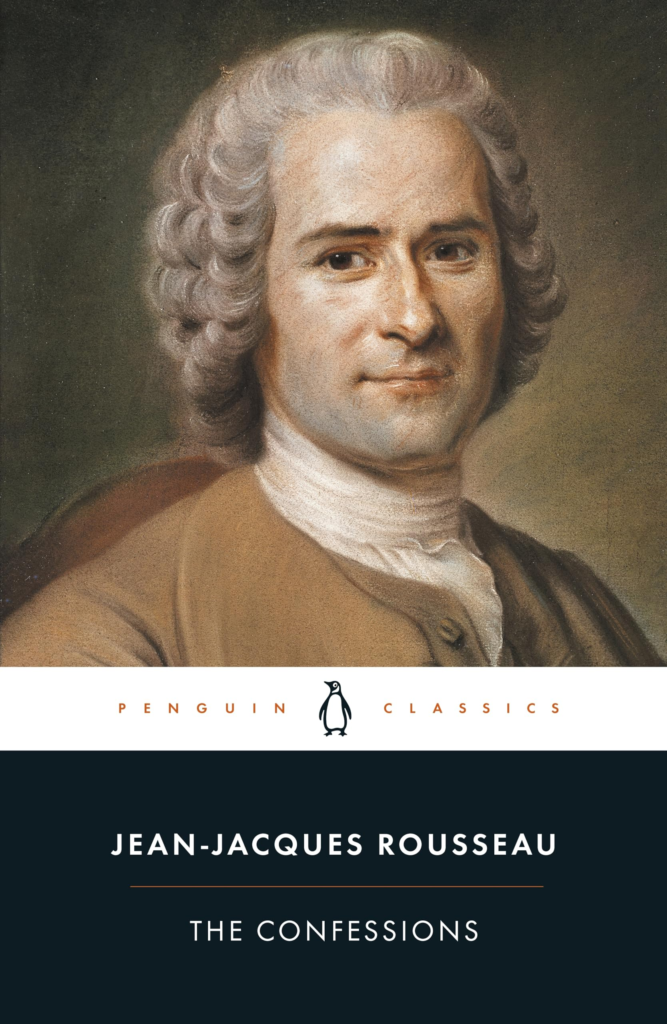

Jean Jacques Rousseau remarked in his Confessions:

“I can only meditate when I am walking.

When I stop, I cease to think, my mind only works with my legs.“

Above: Swiss writer / philosopher / composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Long after Rousseau, the association between walking and philosophizing became so widespread that Central Europe has places named after it:

- the celebrated Philosophenweg in Heidelberg where Hegel walked

Above: Heidelberg, Germany

Above: German philosopher Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel (1770 – 1831)

- the Philosophendamm in Königsberg that Kant passed on his daily stroll

Above: Königsberg Castle, Kalingrad, Russia

Above: German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804)

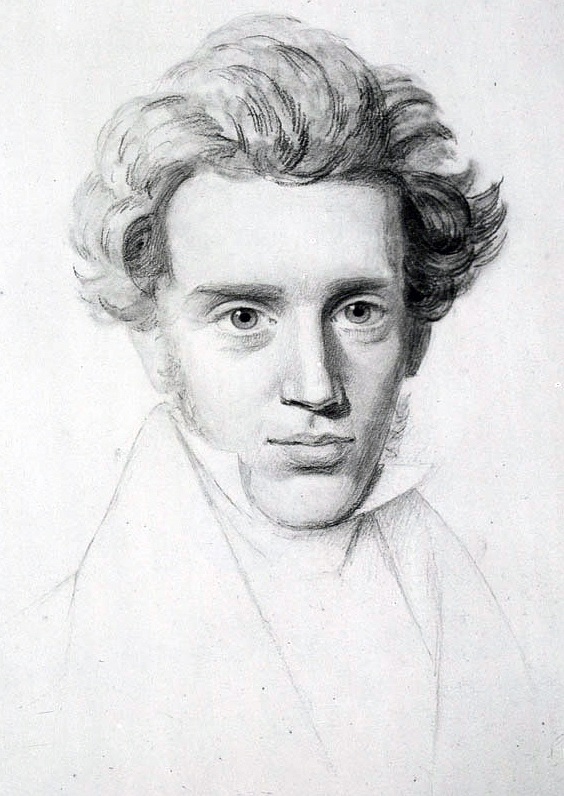

- the Philosopher’s Way Kierkegaard walked in Copenhagen

Above: Copenhagen, Denmark

Above: Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

Philosophers walked.

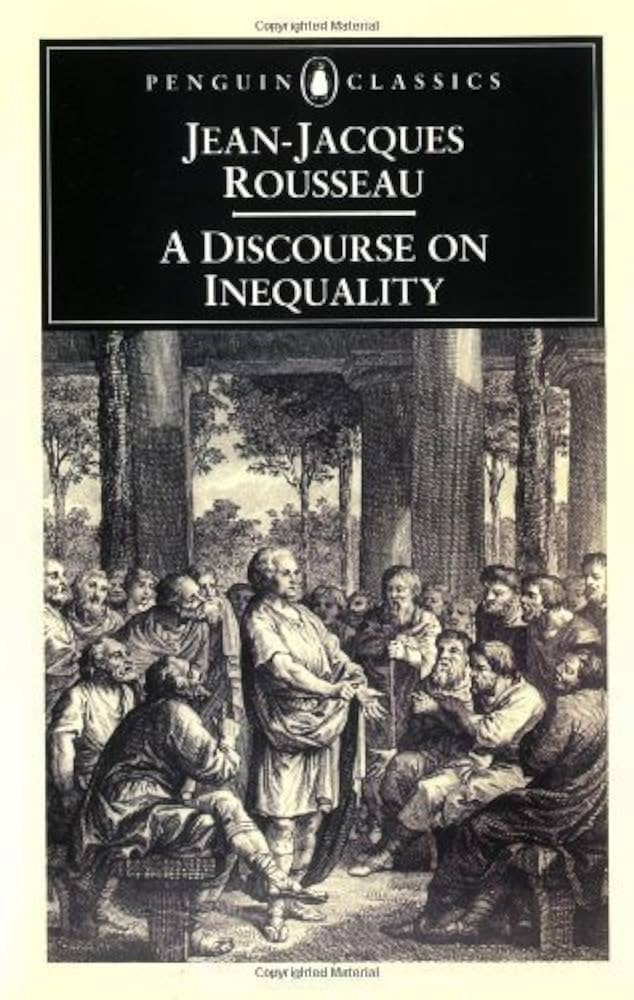

In his Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau portrays man in his natural condition:

“Wandering in the forests, without industry, without speech, without domicile, without war and without liaisons, with no need of his fellow men, likewise with no desire to harm them.“

Walking functions as an emblem of the simple man.

When the walk is solitary and rural, it is a means of being in nature and outside society.

The walker has the detachment of the traveller but travels unadorned and unaugmented, dependent on his bodily strength and wits rather than on conveniences that can be made and bought.

Walking is an activity essentially unimproved since the dawn of time.

“I do not remember ever having had in all my life a spell of time so completely free from care and anxiety.

This memory has left me the strongest taste for everything associated with it, for mountains especially and for travelling on foot. It has always been a delight to me.

Never did I think so much, exist so vividly and experience so much.

Never have I been so much myself as in the journeys I have taken alone and on foot.

There is something about walking which stimulates and enlivens my thoughts.

When I stay in one place I can hardly think at all.

My body has to be on the move to set my mind going.

The sight of the countryside, the succession of pleasant views, the open air, a sound appetite, and the good health I gain by walking, the easy atmosphere of an inn, the absence of everything that makes me feel my dependence, of everything that recalls me to my situation – all these serve to free my spirit, to lend a greater boldness to my thinking, so that I can combine them, select them and make them mine as I will, without fear or restraint.“

For Rousseau, walking is both an exercise of simplicity and a means of contemplation.

A solitary walker is in the world, but apart from it, with the detachment of the traveller rather than the ties of the worker, the dweller, the member of a group.

Within a walk you are able to live in thought and reverie, to be self-sufficient, and thus to survive a world that you feel has betrayed you.

A walk encourages digression and association.

Walking is both an analytical and an improvisational act.

Walking the streets is a way to be among people for someone who cannot be with them, a way to bask in the faint human warmth of brief encounters, acquaintances’ greetings and overheard conversations.

A lone walker is both present and detached from the world around, more than an audience but less than a participant.

Walking relieves and legitimizes alienation:

One is mildly disconnected because one is walking, not because one is incapable of connecting.

Kierkegaard wrote in his Journal:

“In order to bear mental tension such as mine, I need diversion, the diversion of chance contacts on the streets and alleys, because association with a few exclusive individuals is actually no diversion.“

Kierkegaard proposes that the mind works best when surrounded by distraction, that it focuses in the act of withdrawing from surrounding from surrounding bustle rather than in being isolated from it.

“This very moment there is an organ grinder down in the street playing and singing.

It is wonderful.

It is the accidental and insignificant things in Life that are significant.”

Walking is an activity that requires openness, engagement and few expenses.

The new millennium is a dialectic between secrecy and openness, between consolidation and dispersal of power, between the private and the public, between power and life.

Walking is on the side of openness and life.

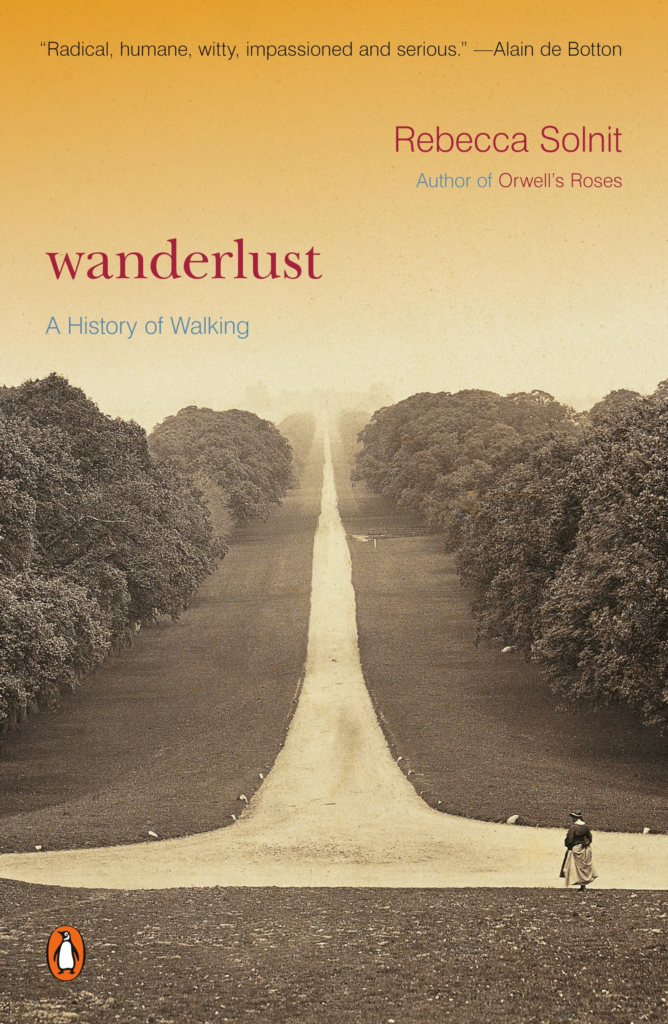

I often quote Rebecca Solnit, for she aptly says the thoughts I feel.

“İnsidious forces are marshalled against the time, space and will to walk and against the version of humanity that act embodies.

One force is the filling-up of “the time in-between”, the time of walking to or from a place, of meandering, of running errands.

That time has been deplored as a waste, reduced. Its remainder filled with earphones playing music and mobile phones relaying conversations.

The very ability to appreciate this uncluttered time, the uses of the useless, often seems to be evaporating, as does the appreciation of being outside – including outside the familiar.

Mobile phone conversations seem to serve as a buffer against solitude, silence and encounters with the unknown.

Above: American writer Rebecca Solnit

People forget that their bodies could be adequate to the challenges that face them and a pleasure to use.

They perceive and imagine their bodies as essentially passive, a treasure or a burden, but not a tool for work and travel.

There is a joy in finding that your body is adequate to get you where you want to go.

It is a gift to develop a more tangible, concrete relationship to your surroundings and its denizens.

To travel assisted by wheels beneath us, where things must be planned and scheduled beforehand, denies us the sense of place that can only be gained on foot.

Too many people nowadays live their lives in a series of interiors – home, car, gym, office, shops – disconnected from the world, and each other.

On foot everything stays connected.

One lives in the whole world rather than in the interiors built up against it.

It is the unpredictable incidents between official events that add up to a life, the incalculable that gives Life value.

The random, the unscreened, allows you to find what you don’t know you are looking for.

You don’t know a place, a person, yourself, until you are surprised by this.

When you give yourself to places (and to people), they give you yourself back.

The more one comes to know them, the more one seeds them with an invisible crop of memories and associations.

Even if you walk the same trail again and again, like Heraclitus’ famous dictum about rivers, you never really step on the same road twice.

Something is always different.

The old becomes new again.

New places offer up new thoughts, new possibilities.

Exploring the world is one of the best ways of exploring the mind.

Walking travels both terrains.

While walking, the body and the mind work together.

Thinking becomes almost a physical, rhythmic act.

Spirituality and sexuality both enter in.

The past and present are brought together.

Each walk moves through space like a thread through fabric, sewing it together into a continuous experience – so unlike the way air / car / train travel chops up time and space, but we can choose to reclaim it, again and again, and some do.

The fields and streets are waiting.“

I cannot and will not judge the hikikomori.

You will emerge from your shadows when and if you are ready.

I can only say that there is life beyond your bedroom and that you can still benefit from your chosen solitude.

We are more connected than ever.

Or so we are told.

We can travel to other continents in just a few hours.

We can speak to friends and family whenever we want, wherever we are, at any time of day.

We can even see their faces beaming from our laptops and mobile phones.

We need never be alone again.

And yet…

One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do

Two can be as bad as one, it’s the loneliest number since the number one

‘No’ is the saddest experience that you’ll ever know

Yes, it’s the saddest experience you’ll ever know

Yes, because one is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do

One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever know

It’s just no good anymore since you went away

Now I spend my time just making thoughts of yesterday

(one by one)

Because one is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do

One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever know

One, is the loneliest number

One, is the loneliest number

One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do

One is the loneliest number, much worse than two

One is a number divided by two

We have never felt more lonely.

On the train or bus on our daily commutes we avoid eye contact with those around us.

We pass the time listening to podcasts or familiar music or to the sound of chosen conversations.

We stare at social media and mutely ponder the lives of others.

We are adrift in the human ocean, in a crowd, permanently alone.

The paradox is that the closer we have moved to other people – crammed into sprawling cities and permanently connected via the Internet, the lonelier we have become.

The history of modernity is the chronicle of loneliness.

We can (and perhaps should) counteract this loneliness by making more meaningful connections, by playing active roles in our communities, by taking more seriously the links we already have.

But we can also be comfortable on our own – to be happy, to even thrive alone.

The cure for loneliness can be solitude.

Instead of feeling deprived of the company of others, we should feel satisfied within ourselves, with the boundless world each of us contains and inhabits.

One can feel utterly alone in a crowd of people, but completely content alone at the top of a mountain – and, crucially, vice versa.

Solitude can (and should) be balanced with sociability.

Both are needed for a fulfilling life.

The classical world was wary of excessive solitude.

Socrates said that the unexamined life was not worth living, but he meant examined in company.

Above: Marble bust of Greek philosopher Socrates (470 – 399 BC)

Plato wrote dialogues, not monologues.

Above: Portrait bust of Greek philosopher Plato (428 – 348 BC)

Aristotle believed that humans are fundamentally social.

He declared that a person who is unable to live in society or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself must either be a beast or a god.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

At the twilight of classıcal antiquity, however, something changed.

People started choosing to be alone.

Repulsed by the corruption of the world, tired of its limitless greed, devout men and women elected for a life of solitude.

Some chose to be hermits, separating themselves entirely from the society around them.

Above: Hermit caves, Spain

Others formed small, largely self-sufficient, communities where they could be alone, together.

In solitude they pursued rigorous programs of prayer and introspection.

Their writing influenced centuries of thought on what it means to be human.

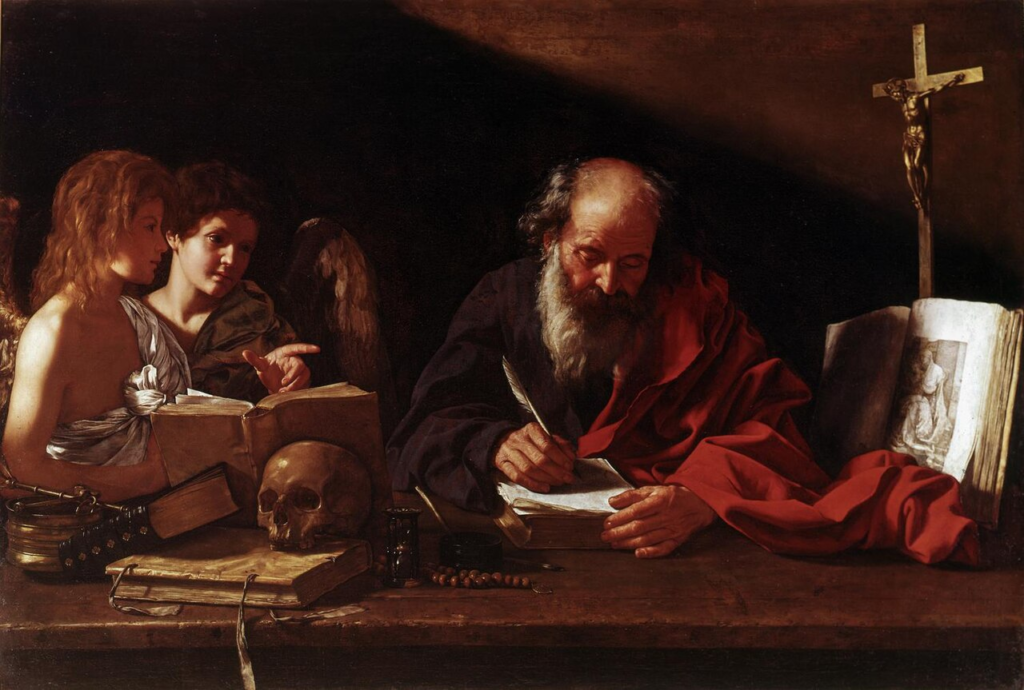

Above: Jerome of Stridon (342 – 420) who lived as a hermit near Bethlehem, depicted in his study being visited by two angels, Bartolomeo Cavarozzi (1650)

Eventually, during the Renaissance, people began to pay increased attention to individuals – to their unique qualities and capacities and to their inner lives as separate from religious considerations.

To understand what could be discovered about one’s self and the world in solitude.

Above: The School of Athens, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1511)

This new emphasis on the individual led to a more formal interest in what one could independently verify.

By the 17th century, certain thinkers began to distinguish between received wisdom and what each person could discover and prove for themselves.

René Descartes felt that he needed solitude to truly doubt what he had been taught to believe, to be free of received wisdom and to discover the truth about our world.

Above: French philosopher René Descartes (1596 -1650)

In the 18th century, people reacted against the cold rationalistic view of human life.

They began to focus instead on their emotions, charting and describing their shifting emotional states and contrasting their various sentiments and sensibilities.

Novels which paid sustained attention to the lives of individual people became popular.

The novel heralded the rise of that most solitary act:

Private reading.

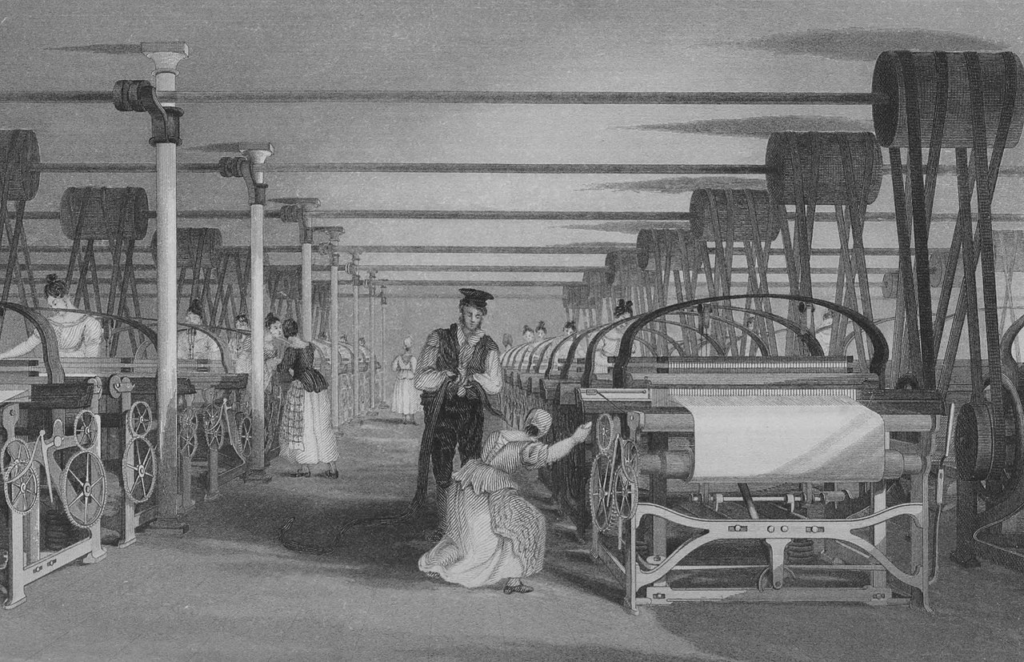

By the 19th century, many writers were seeking solitude in the beauty and splendor of the natural world as an aid to poetic introspection, but while such people explored their inner lives by reading from the Book of Nature or by reflecting on the latest novel, others were busy transforming the natural world.

New machinery and management techniques sped up production, but they required huge numbers of workers.

People left the countryside to take up these new jobs and swelled the ranks of city dwellers.

The modern crowd was born and with it a whole new way of being alone.

The Industrial Revolution led to a host of new political and social problems.

Many people were eager to escape the effects of this new industrialized world.

One popular form of escape was the pursuit of solitude, especially in those places which remained untouched by industrial progress.

Only there could one be truly natural, uncorrupted by society or by the mechanization of the world.

Already in the 19th century, people worried about where our ruthless treatment of nature would lead us and what its destruction would do to our spirits.

At the turn of the 20th century, people began to realize that whole social groups had been left out of such considerations.

The English historian Edward Gibbon declared that:

“Conversation enriches the understanding, but solitude is the school of genius.“

Solitude was necessary to create art.

Above: English historian Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794)

We need to cope with the fact – as Joseph Conrad put it – that we live as we dream – alone.

Above: Polish-born English writer Joseph Conrad (né Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski) (1857 – 1924)

We must truly connect with ourselves and, in the process, how we can meaningfully connect with those around us, including the Earth itself.

Solitude is always focused both inward and outward, towards the self and towards the world.

The cure for loneliness is, in the end, the art of solitude.

In a little while from now

If I’m not feeling any less sour

I promise myself to treat myself

And visit a nearby tower

And climbing to the top

Will throw myself off

In an effort to

Make it clear to whoever

Wants to know what it’s like when you’re shattered

Left standing in the lurch at a church

Were people saying, “My God, that’s tough,

She stood him up.

No point in us remaining.

We may as well go home.”

As I did on my own

Alone again, naturally

To think that only yesterday

I was cheerful, bright and gay

Looking forward to who wouldn’t do

The role I was about to play

But as if to knock me down

Reality came around

And without so much as a mere touch

Cut me into little pieces

Leaving me to doubt

Talk about, God in His mercy

Oh, if he really does exist

Why did he desert me

In my hour of need

I truly am indeed

Alone again, naturally

It seems to me that

There are more hearts broken in the world

That can’t be mended

Left unattended

What do we do

What do we do

Alone again, naturally

Looking back over the years

And whatever else that appears

I remember I cried when my father died

Never wishing to hide the tears

And at sixty-five years old

My mother, God rest her soul

Couldn’t understand why the only man

She had ever loved had been taken

Leaving her to start

With a heart so badly broken

Despite encouragement from me

No words were ever spoken

And when she passed away

I cried and cried all day

Alone again, naturally

Alone again, naturally

Sources

Manhood, Steve Biddulph

Just to Keep in Mind: Essays from a Life in Business, Bülent Eczacibaşi

The Independent Scholar’s Handbook, Ronald Gross

Real World English, Shirley Hudson

“One is the Loneliest Number“, Aimee Mann

“Alone Again (Naturally)“, Gilbert O’Sullivan

Confessions, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Art of Solitude, edited by Zachary Seager

Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit

Wikipedia

Wikiquote