Saturday 1 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

February 1 is a day where the echoes of past struggles ring through history, where freedom found often stands on the precipice of being lost.

It is a day of amendments and uprisings, of poets and revolutionaries, of movements born and battles still being fought.

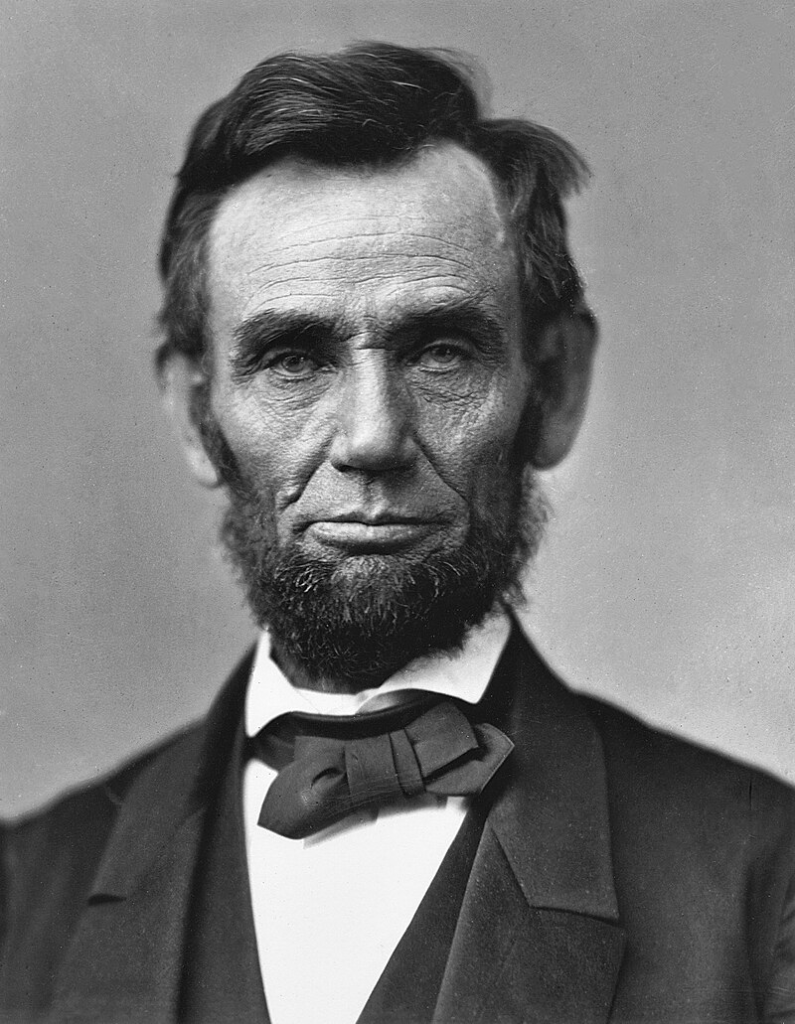

On this day in 1865, the United States ratified the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, declaring once and for all that no human being should be owned.

Above: Coat of arms of the United States of America

And yet, a century later, young Black men in Greensboro, North Carolina, had to take seats at a lunch counter where their presence was unwelcome, demanding to be seen as equals.

Above: The Greensboro Four: David Richmond (1941 – 1990), Franklin McCain (1941 – 2014), Ezell A. Blair, Jr. (born 1941) and Joseph McNeil (born 1942)

Above: Former F. W. Woolworth Co. store in Greensboro, North Carolina, the site of a now-famous “sit-in” protest by black college students in 1960

And today, does freedom truly exist if systemic barriers remain? If dignity is still something to be fought for?

The ink had barely dried on that Amendment when the Voice of America first crackled across the airwaves in 1942, promising to bring truth in the face of war’s deception.

But what is truth when it is shaped by those in power?

When does a voice for people become a voice of propaganda?

Above: Logo of the Voice of America

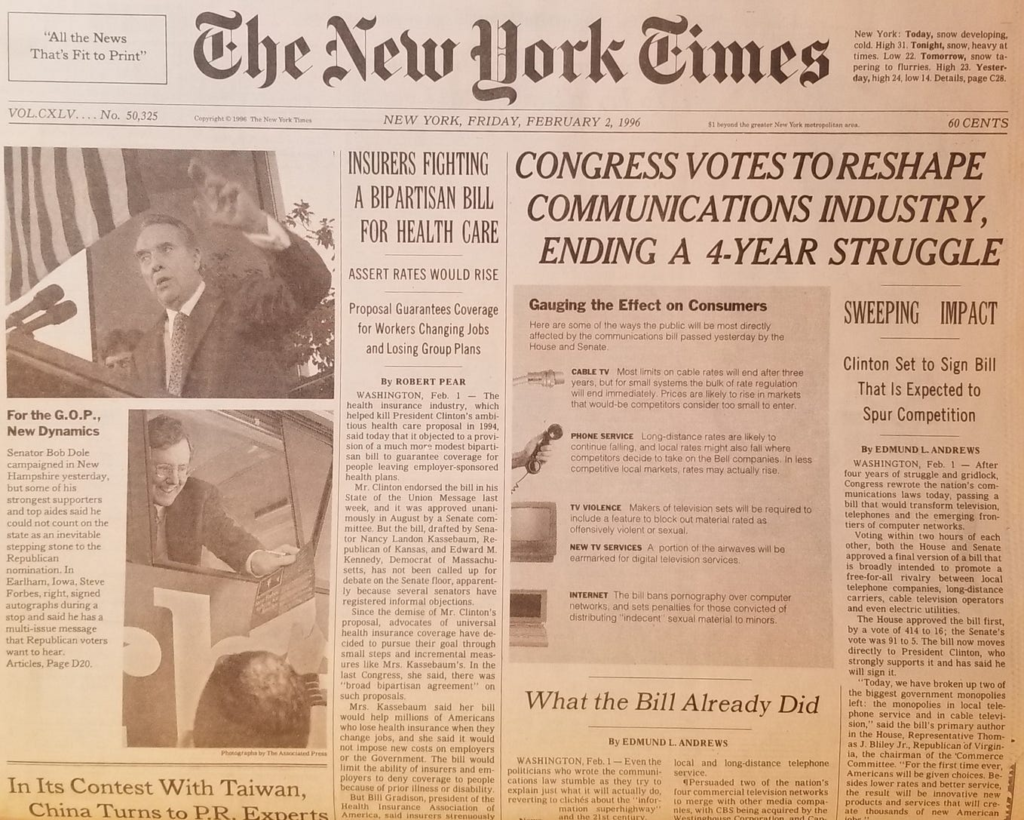

In 1996, the Communications Decency Act sought to regulate speech on the burgeoning Internet, a digital frontier that promised limitless expression.

But whose speech was being protected, and whose was being silenced?

And in 2021, Myanmar awoke to the sounds of military boots once again.

A coup d’état, crushing the fragile democracy it had only just begun to nurture.

How quickly freedom fades when vigilance falters.

Above: Flag of Myanmar

But this day is not only about laws and uprisings:

It is also about the voices that remind us of what is at stake.

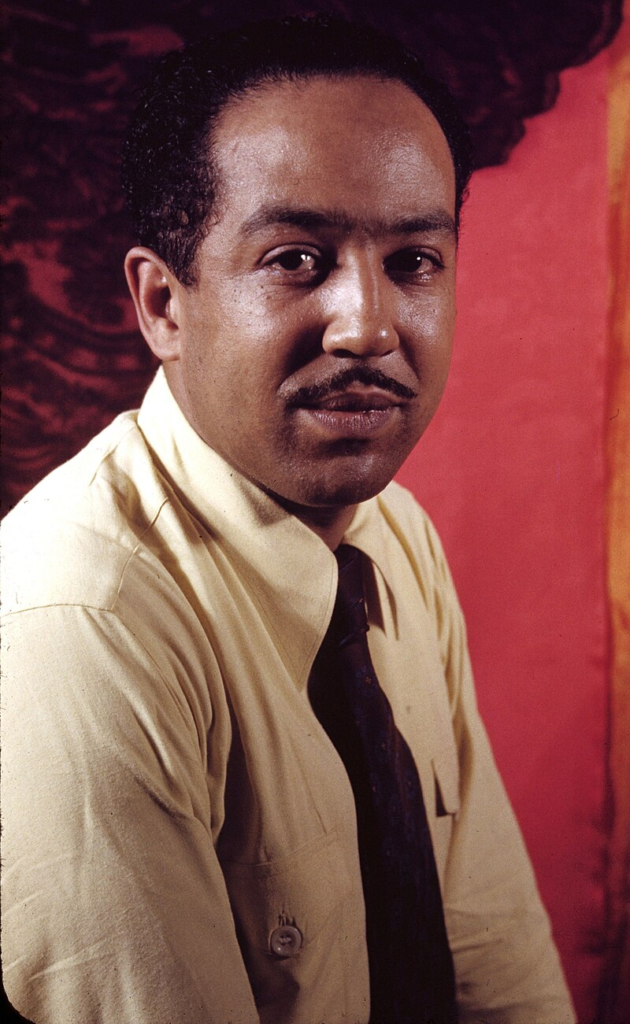

Langston Hughes, born on this day in 1902, saw America as both a promise and a betrayal.

I, too, sing America, he wrote, defiantly, reminding the world that those once enslaved would not be erased.

If Hughes could see 2025, would he believe his song had been fully heard, or would he find himself writing yet another verse, lamenting the unfinished work of justice?

Would he see the fights for racial equality, the movements against oppression, and the voices still struggling to be recognized as a sign of progress — or as proof of a dream deferred?

Above: American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967), one of the earliest innovators of the literary form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

Growing up in the Midwest, Hughes became a prolific writer at an early age.

He moved to New York City as a young man, where he made his career.

He studied at Columbia University in New York City.

Above: Coat of arms of Columbia University, New York City, New York

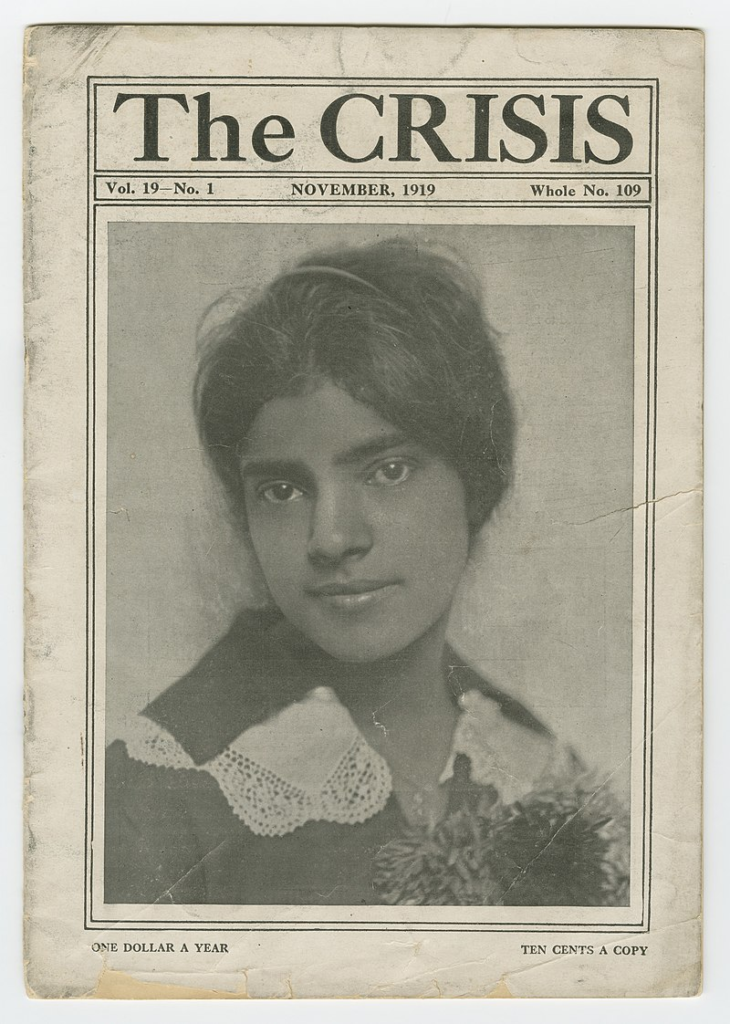

Although Hughes dropped out, he gained notice from New York publishers, first in The Crisis magazine and then from book publishers, and became known in the creative community in Harlem.

His first poetry collection, The Weary Blues, was published in 1926.

Hughes eventually graduated from Lincoln University.

In addition to poetry, Hughes wrote plays and published short story collections, novels, and several nonfiction works.

From 1942 to 1962, as the civil rights movement gained traction, Hughes wrote an in-depth weekly opinion column in a leading black newspaper, The Chicago Defender.

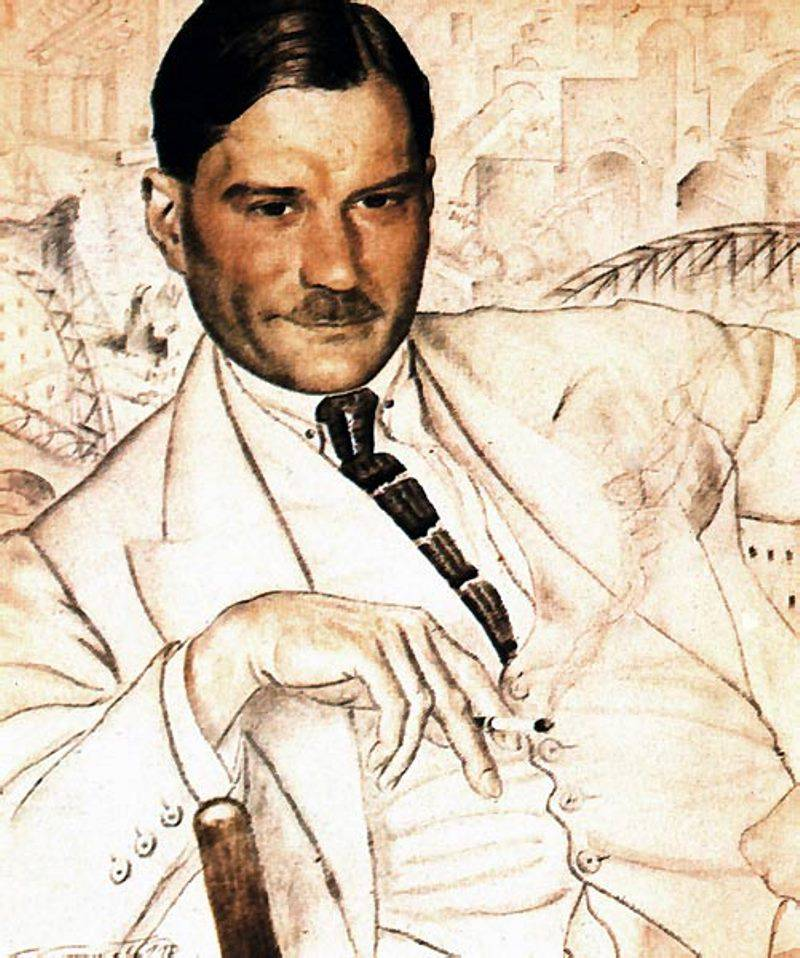

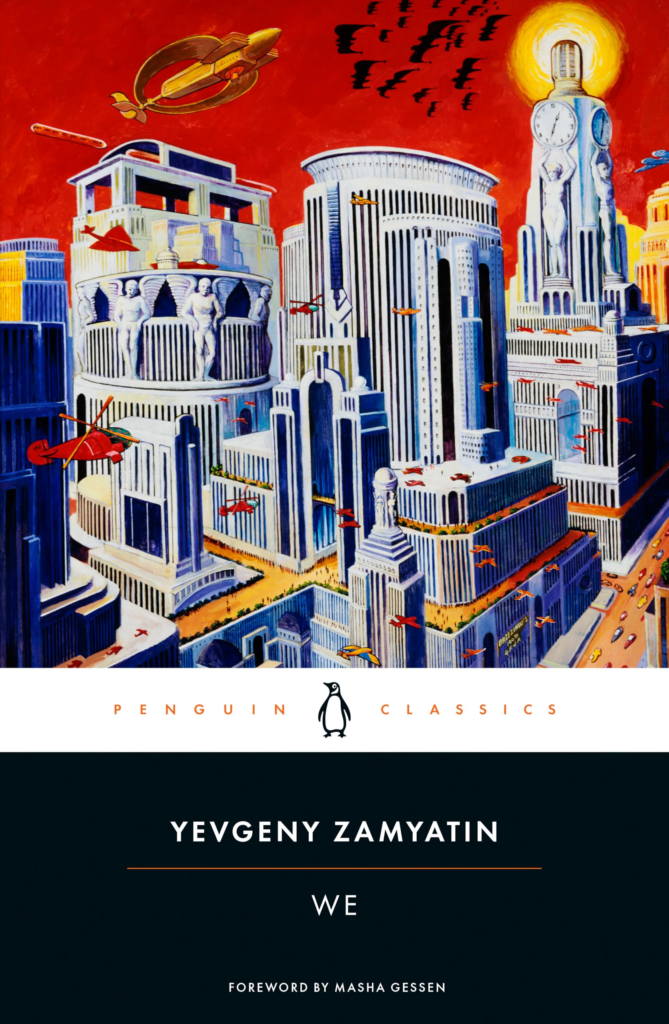

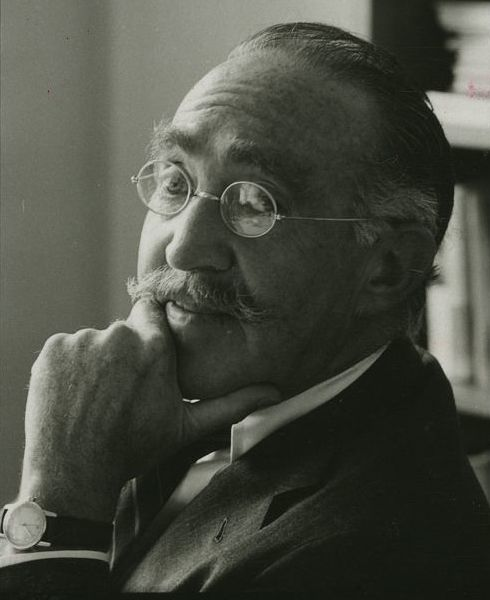

Yevgeny Zamyatin, born on this day in 1884, warned of a future where individuality is crushed beneath the weight of a totalitarian machine.

Above: Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin (February 1, 1884 – March 10, 1937)

The son of a Russian Orthodox priest, Zamyatin lost his faith in Christianity at an early age and became a Bolshevik.

As a member of his Party’s Pre-Revolutionary underground, Zamyatin was repeatedly arrested, beaten, imprisoned, and exiled.

However, Zamyatin was just as deeply disturbed by the policies pursued by the All-Union Communist Party following the October Revolution as he had been by Tsarist policy.

Above: Communist Party of the Soviet Union logo (1912 – 1991)

Due to his subsequent use of literature to both satirize and criticize the Soviet Union’s enforced conformity and increasing totalitarianism, Zamyatin, dubbed “a man of incorruptible and uncompromising courage“, is now considered one of the first Soviet dissidents.

He is most famous for his highly influential and widely imitated 1921 dystopian science fiction novel We, which is set in a futuristic police state.

In 1921, We became the first work banned by the Soviet censorship board.

Ultimately, Zamyatin arranged for We to be smuggled to the West for publication.

The outrage this sparked within the Party and the Union of Soviet Writers led directly to the State-organized defamation and blacklisting of Zamyatin and his successful request for permission from Joseph Stalin to leave his homeland.

Above: Soviet leader Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953)

In 1937 Zamatin died in poverty in Paris.

After his death, Zamyatin’s writings were circulated in samizdat (censored and underground makeshift publications) and continued to inspire multiple generations of Soviet dissidents.

Above: Grave of the Russian author Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin in the Cimetière parisien de Thiais (Division 21, Line 5, Grave 36)

His novel We became a blueprint for Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World.

If Zamyatin were to look upon the world today, would he see his dystopian visions come to life?

The rise of surveillance states, the algorithms that dictate human behavior, the illusions of choice in an age of corporate and governmental control — would he nod knowingly, or would he recoil in horror at how prophetic his warnings have proven to be?

Above: Yevgeny Zamyatin

Hughes’ vision, a world where all voices are heard and equality is not just promised but realized — feels both closer and yet frustratingly out of reach.

His optimism might be tempered by the persistence of systemic inequalities, yet he would likely still believe in the fight.

His poem Harlem asked:

“What happens to a dream deferred?”

Above: Langston Hughes

In 2025, the answer still depends on who is answering.

Some would say it festers, others that it explodes.

Zamyatin’s world, meanwhile, seems eerily prescient.

The rise of digital surveillance, AI-driven social control, and the manipulation of public thought through technology bear unsettling similarities to We.

Would Zamyatin recognize our world as a more sophisticated version of the dystopia he envisioned?

Likely, but unlike Orwell’s 1984, where control is brutally enforced, today’s world subtly nudges people into compliance — through convenience, misinformation, and corporate interests rather than overt oppression.

Huxley’s vision in Brave New World looms large here, a world where people are enslaved not by chains, but by their own willingness to surrender critical thought in exchange for comfort.

Their visions, in different ways, live on.

Do you think Hughes would see more hope or disappointment in today’s world?

And would Zamyatin find rebellion still possible, or would he see a society too comfortable to fight back?

And what of those who found freedom not in revolution but in the quiet power of words?

Muriel Spark, sharp as a dagger, exposing the hypocrisies of polite society.

Above: Scottish novelist Muriel Spark (1 February 1918 – 13 April 2006)

S. J. Perelman, who laughed at the absurdity of it all, because sometimes humor is the only weapon left.

Above: US humorist Sidney Joseph Perelman (February 1, 1904 – October 17, 1979)

Meg Cabot, spinning fairy tales for modern girls, where the princess saves herself.

Above: American novelist Meg Cabot

Today is also a day of remembrance and identity.

St. Brigid’s Day (Imbolc) in Ireland, a moment where Celtic tradition and Christian faith intertwine, much like the country itself — a nation always seeking to balance its past with its future.

Above: St. Brigid’s cross

National Freedom Day in the US, marking that first step toward emancipation, a step that still requires marching.

National Freedom Day is an observance on February 1 honoring the signing by President Abraham Lincoln of a joint House and Senate resolution that later was ratified as the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution.

President Lincoln signed the Amendment abolishing slavery on February 1, 1865, although it was not ratified by the states until later.

Above: US President Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865)

The start of Black History Month, where stories must be told so they are never forgotten.

Black History Month is an annually observed commemorative month originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month.

It began as a way of remembering important people and events in the history of the African diaspora, initially lasting a week before becoming a month-long observation since 1970.

It is celebrated in February in the United States and Canada, where it has received official recognition from governments, and more recently has also been celebrated in Ireland and the United Kingdom where it is observed in October.

World Hijab Day, a celebration of choice, a reminder that freedom means different things to different people, and yet it remains a struggle for all.

Perhaps that is the lesson of February 1.

Freedom is never won, it is only ever borrowed, and only for as long as we guard it.

From amendments to uprisings, from poets to prophets, from symbols to speech, the struggle is unending.

And as history has shown us time and again, when we take freedom for granted, we risk losing it.

What will you do with your borrowed freedom?

Will you defend it, question it, challenge it — or let it slip quietly away?

The voices of the past are calling, but the answer is ours to give.

The individual’s power lies in awareness, resistance, and creation.

Awareness means recognizing the forces that shape our reality —whether corporate influence, political control, or societal complacency.

Resistance can be grand, like protests and activism, or quiet, like choosing where to place one’s attention, what stories to amplify, and what truths to speak.

Creation is perhaps the most lasting form of rebellion: writing, art, music, and ideas that challenge the status quo and keep freedom alive in the minds of those who engage with them.

Hughes and Zamyatin would likely say that the individual’s power is never lost, but it is often surrendered.

The question is whether we will use it.