Sunday 2 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

The second day of February is a day of shadows and signals, omens and revelations, of humanity’s eternal dance with the unknown.

We search the skies, the ground, the movements of animals, and the echoes of history to divine what lies ahead.

It is a day of crossings, where survival meets fate, literature meets legend, and warnings either heed or fall to the abyss.

Each year, on this day, North America turns its gaze to a groundhog, waiting for a signal from nature.

Will winter persist, or will spring’s promise arrive early?

Above: A groundhog

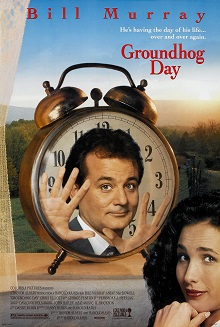

Groundhog Day (Pennsylvania German: Grund’sau dåk, Grundsaudaag, Grundsow Dawg, Murmeltiertag; Nova Scotia: Daks Day) is a tradition observed regionally in the United States and Canada on February 2 of every year.

It derives from the Pennsylvania Dutch superstition that if a groundhog emerges from its burrow on this day and sees its shadow, it will retreat to its den and winter will go on for six more weeks.

If it does not see its shadow, spring will arrive early.

In 2024, an early spring was predicted.

While the tradition remains popular in the 21st century, studies have found no consistent association between a groundhog seeing its shadow and the subsequent arrival time of spring-like weather.

The weather lore was brought from German-speaking areas where the badger (German: Dachs)(Turkish: Porsuk) is the forecasting animal, while in Hungary for example the bear serves the same purpose, and badgers were only watched when bears were not around.

Above: Porsuk Stream, Eskişehir, Turkiye

It is related to the lore that clear weather on the Christian festival of Candlemas forebodes a prolonged winter.

The Groundhog Day ceremony held at Punxsutawney in western Pennsylvania, centering on a semi-mythical groundhog named Punxsutawney Phil, has become the most frequently attended ceremony.

Grundsow Lodges in Pennsylvania Dutch Country in the southeastern part of the state observe the occasion as well.

Above: Two smiling men dressed in formal attire stand beside each other.

Other people and bare trees are visible in the background.

The man on the left holds groundhog Punxsutawney Phil in his arms.

The man on the right, wearing an earpiece, holds forward an open scroll, which reads in small text:

“Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye.

Today, 2-2-2025, welcome to Punxsutawney to celebrate Groundhog Day, the 139th annual trek of the Punxsutawney Groundhog Club.

Punxsutawney Phil, the Seer of Seers, the Prognosticator of all Prognosticators, was gently lifted from his burrow at 0725 am and held high to see his faithful followers had returned with glee!

Placing Phil on top of the stump, where in Groundhogese, he directed the President, ______________, and the inner circle to his prediction scroll that reads….“

Other cities in the United States and Canada also have adopted the event.

The Slumbering Groundhog Lodge, which was formed in 1907, has carried out the ceremonies that take place in Quarryville, Pennsylvania.

It used to be a contending rival to Punxsutawney over the Groundhog Day fame.

It employs a taxidermic specimen (stuffed woodchuck).

Above: Quarryville Library, Quarryville, Pennsylvania, USA

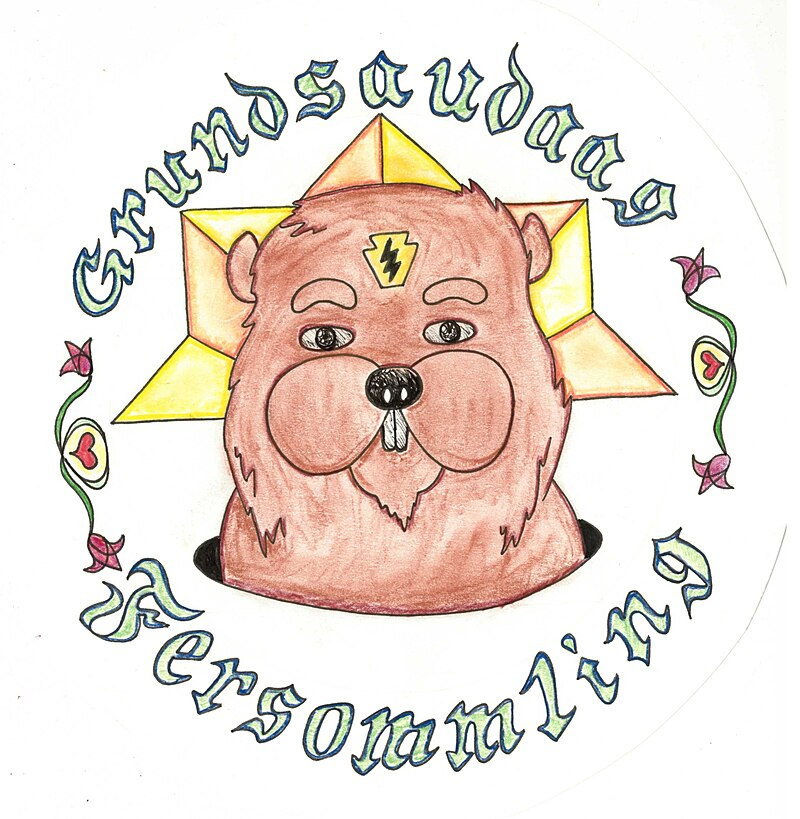

In Southeastern Pennsylvania, Groundhog Lodges (Grundsow Lodges) celebrate the holiday with fersommlinge, social events in which food is served, speeches are made, and one or more g’spiel (plays or skits) are performed for entertainment.

The Pennsylvania German dialect is the only language spoken at the event, and those who speak English pay a penalty, usually in the form of a nickel, dime, or quarter per word spoken, with the money put into a bowl in the center of the table.

(Perhaps this penalty idea should be applied to my students who speak Turkish in their English language lessons?)

In Milltown, New Jersey, Milltown Mel was purchased in 2008 in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, by Jerry and Cathy Guthlein, and lived in a cage in the Guthleins’ back yard.

Mel’s first event was at the family business, the Bronson and Guthlein Funeral Home, with later events moved to the American Legion Post, with free coffee and doughnuts served afterwards.

(Mel died in 2021.)

Above: Milltown Mel

Stonewall Jackson predicts at Space Farms Zoo and Museum.

Above: Attraction logo, Sussex, New Jersey, USA

Essex Ed the groundhog and Otis the Hedgehog predict at Turtle Back Zoo.

Above: Attraction logo, West Orange, New Jersey, USA

Malverne Mel is the groundhog of Malverne, in Long Island, New York.

Mel began his position in 1996.

Above: Malverne Mel

Great Neck Greta, of Great Neck, Long Island, New York, predicted in 2020.

Above: Great Neck Greta?

Quigley, of The Hamptons (resident of the Save the Animals Rescue Foundation), predicts at Quogue Village Fire Department.

Above: Sunrise over the beaches of Quogue, Long Island, New York

Staten Island Chuck is the stage name for the official weather-forecasting woodchuck for New York City, housed in the Staten Island Zoo.

Above: Staten Island Chuck

In 2009, Chuck bit then-NYC-Mayor Mike Bloomberg, prompting zoo officials to quietly replace him with his daughter Charlotte.

Above: Michael Bloomberg

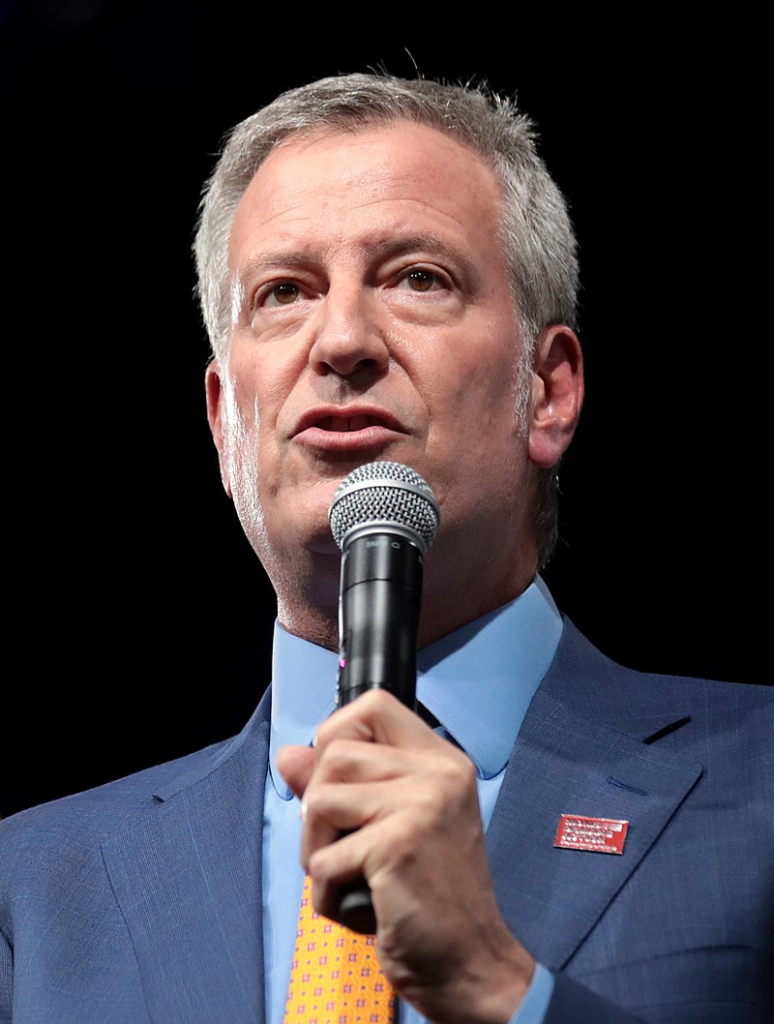

In 2014, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio, famously dropped Charlotte during the ceremony, visibly disturbing many of the children present for the event.

Charlotte’s untimely death a week later prompted rumors she was killed by the fall, although the zoo later said this was unlikely to be the cause of Charlotte’s demise.

As a result, Bill de Blasio did not participate in the tradition thereafter.

Above: Bill de Blasio

Dunkirk Dave (a stage name for numerous groundhogs that have filled the role since 1960) is the local groundhog for Western New York, handled by Bob Will, a typewriter repairman who runs a rescue shelter for groundhogs.

Will is adamant that Dunkirk Dave does not actually predict the date of spring because that is fixed by calendars, but instead predicts the harshness of the remainder of winter.

French Creek Freddie is West Virginia’s resident groundhog meteorologist.

A resident of the West Virginia State Wildlife Center in French Creek, West Virginia, Freddie made his debut in 1978, and boasts an accuracy rate of approximately 50%.

On Groundhog Day, 2022, Freddie predicted six more weeks of winter, with the Mayor of Buckhannon and members of the community in attendance.

Above: French Creek Freddie

Holtsville Hal resides at the Holtsville Ecology Site and Animal Preserve in Holtsville, NY.

He predicts the weather for Suffolk County, NY, in front of hundreds of residents each Groundhog Day.

Above: Lily pads and lotus flowers, Holtsville Ecology Park, Holtsville, New York

In the Midwest, Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, is the self-proclaimed “Groundhog Capital of the World“.

Above: Downtown Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, USA

This title taken in response to the Punxsutawney Spirit‘s 1952 newspaper article describing Sun Prairie as a “remote two cow village buried somewhere in the wilderness…”

In 2015, Jimmy the Groundhog bit the ear of Mayor Jon Freund and the story quickly went viral worldwide.

The next day a mayoral proclamation absolved Jimmy XI of any wrongdoing.

Above: Inspired by Mike Tyson (1997), Jimmy the Groundhog bites the Mayor’s ear, 2 February 2015

Buckeye Chuck, Ohio’s official State Groundhog, is one of two weather-predicting groundhogs.

He resides in Marion, Ohio.

Above: Buckeye Chuck

Woodstock Willie, in Woodstock, Illinois, the shooting location for the 1993 film Groundhog Day.

Above: The landmark Woodstock Opera House building in historic downtown Woodstock, Illinois, USA

Concord Casimir, while not a groundhog, is a weather-predicting cat whose forecast is based on how he eats his annual pierogi meal.

He resides in Concord, Ohio, on the outskirts of Cleveland.

Above: Conrad Casimir

In Washington DC, the Dupont Circle Groundhog Day event features Potomac Phil, another taxidermic specimen.

From his first appearance in 2012 to 2018, Phil’s spring predictions invariably agreed with those of the more lively Punxsutawney Phil, who made his predictions half an hour earlier.

In addition, Phil always predicted correctly six more months of political gridlock.

However, after being accused of collusion in 2018, Potomac Phil contradicted Punxsutawney Phil in 2019, and further, predicted two more years of political insanity.

Above: Potomac Phil

Birmingham Bill, at Birmingham Zoo, was “taking a break” from predicting in 2015.

Above: Attraction logo, Birmingham, Alabama, USA

In Raleigh, North Carolina, an annual event at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences included Sir Walter Wally.

According to museum officials, Wally had been correct 58% of the time vs. Punxsutawney Phil’s 39%.

Sir Walter Wally retired after 2022 leaving Snerd of Garner as the only weather-predicting groundhog in the state.

Elsewhere in the American South, the General Beauregard Lee makes predictions from Lilburn, Georgia (later Butts County, Georgia).

The University of Dallas in Irving, Texas has boasted of hosting the second largest Groundhog celebration in the world.

The day is observed with various ceremonies at other locations in North America beyond the United States.

Above: Seal of the University of Dallas, Dallas, Texas, USA

In Nova Scotia, Groundhog Day traditions arrived with German Foreign Protestant immigrants in the 1750s where it was known as “Daks Day” (from the German dachs in the German dialect of Lunenburg County settlers.)

Due to Nova Scotia’s Atlantic Time Zone, the province’s official groundhog, Shubenacadie Sam makes the first Groundhog Day prediction in North America, a tradition at Nova Scotia’s Shubenacadie Wildlife Park since 1987.

Above: Shubenacadie Sam celebrations

In French Canada, where the day is known as Jour de la marmotte, Fred la marmotte of Val-d’Espoir was the representative forecaster for the province of Québec from 2009 until his death in 2023.

A study also shows that in Québec, the marmot and groundhog (siffleux) are regarded as Candlemas weather-predicting beasts in some scattered spots, but the bear is the more usual animal.

Above: Fred la marmotte

Wiarton Willie forecasts annually from Wiarton, Ontario.

Above: Wiarton Willie

Manitoba Merv has been forecasting since the 1990s, at Oak Hammock Marsh.

Above: Oak Hammock Marsh, Manitoba, Canada

Winnipeg Wyn has been forecasting since the 2010s, at Prairie Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre.

Above: Winnipeg Wyn

Balzac Billy is the “Prairie Prognosticator“, a man-sized groundhog mascot who prognosticates weather on Groundhog Day from Balzac, Alberta.

Above: Balzac Billy

Nanaimo, a ferry port city on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada presents Chopper, Marlu, and Van Isle Violet, all wild Vancouver Island marmots, for forecasts, via the Marmot Recovery Foundation.

Above: Vancouver Island marmot, Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District, British Columbia, Canada

The Pennsylvania Dutch were immigrants from German-speaking areas of Europe.

The Germans had a tradition of marking Candlemas (February 2) as “Badger Day” (Dachstag), on which if a badger emerging from its den encountered a sunny day, thereby casting a shadow, it heralded four more weeks of winter.

Above: European badger

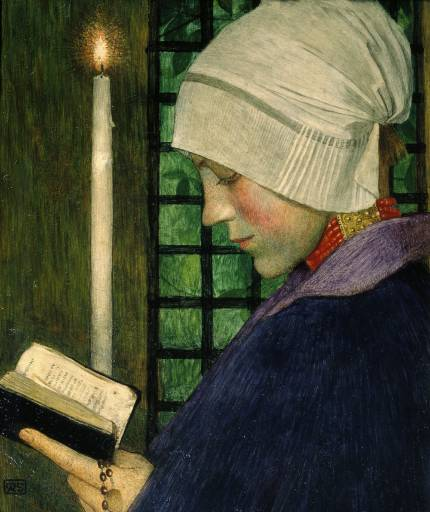

Candlemas is a Western Christian festival observed in the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches.

In folk religion, various traditional superstitions continue to be linked with the holiday, although this was discouraged by the Reformed Churches in the 16th century.

Notably, several traditions that are part of weather lore use the weather at Candlemas to predict the start of spring.

The weather-predicting animal on Candlemas was usually the badger, although regionally, the animal was the bear or the fox.

Above: Candlemas Day, Marianne Stokes (1901)

The original weather-predicting animal in Germany had been the bear, another hibernating mammal, but when they grew scarce, the lore became altered.

Similarity to the groundhog lore has been noted for the German formula:

Sonnt sich der Dachs in der Lichtmeßwoche, so geht er auf vier Wochen wieder zu Loche. (“If the badger sunbathes during Candlemas-week, for four more weeks he will be back in his hole.”)

A slight variant is found in a collection of weather lore (Bauernregeln: “farmers’ rules“) printed in Austria in 1823.

Above: European badger

The Pennsylvanians maintained the same tradition as the Germans on Groundhog Day, except that winter’s spell would be prolonged for six weeks instead of four.

For the Pennsylvania Dutch, the badger became the dox, which in Deitsch referred to “groundhog“.

The standard term for “groundhog” was grun’daks (from German dachs), with the regional variant in York County being grundsau, a direct translation of the English name, according to a 19th-century book on the dialect.

The form was a regional variant according to one 19th-century source.

However, the weather superstition that begins Der zwet Hær’ning is Grund’sau dåk. Wânn di grundsau îr schâtte sent… (“February second is Groundhog Day. If the groundhog sees its shadow…“) is given as common to all fourteen counties in Dutch Pennsylvania Country, in a 1915 monograph.

In The Thomas R. Brendle Collection of Pennsylvania German Folklore, Brendle preserved the following lore from the local Pennsylvania German dialect:

Wann der Dachs sei Schadde seht im Lichtmess Marye, dann geht er widder in’s Loch un beleibt noch sechs Woche drin.

Wann Lichtmess Marye awwer drieb is, dann bleibt der dachs haus un’s watt noch enanner Friehyaahr.”

(“When the groundhog sees his shadow on the morning of Mary Candlemas, he will again go into his hole and remain there for six weeks.

But if the morning of Mary Candlemas is overcast, the groundhog will remain outside and there will be another spring.”)

The form grundsow has been used by the lodge in Allentown and elsewhere.

Brendle also recorded the name “Grundsaudag” (Groundhog day in Lebanon County) and “Daxdaag” (Groundhog Day in Northampton County).

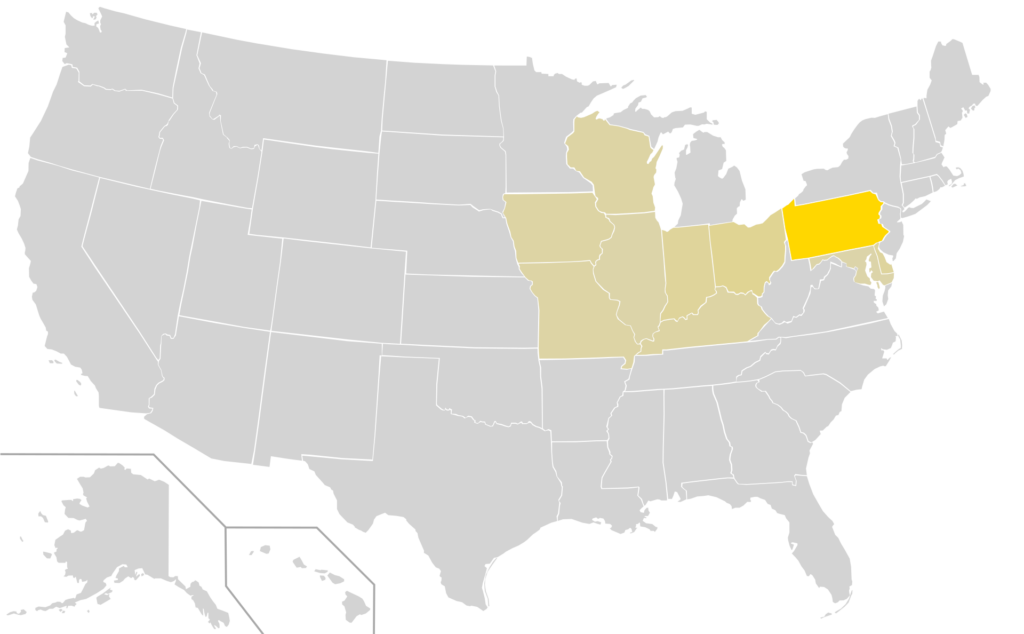

Above: Pennsylvania Dutch map distribution

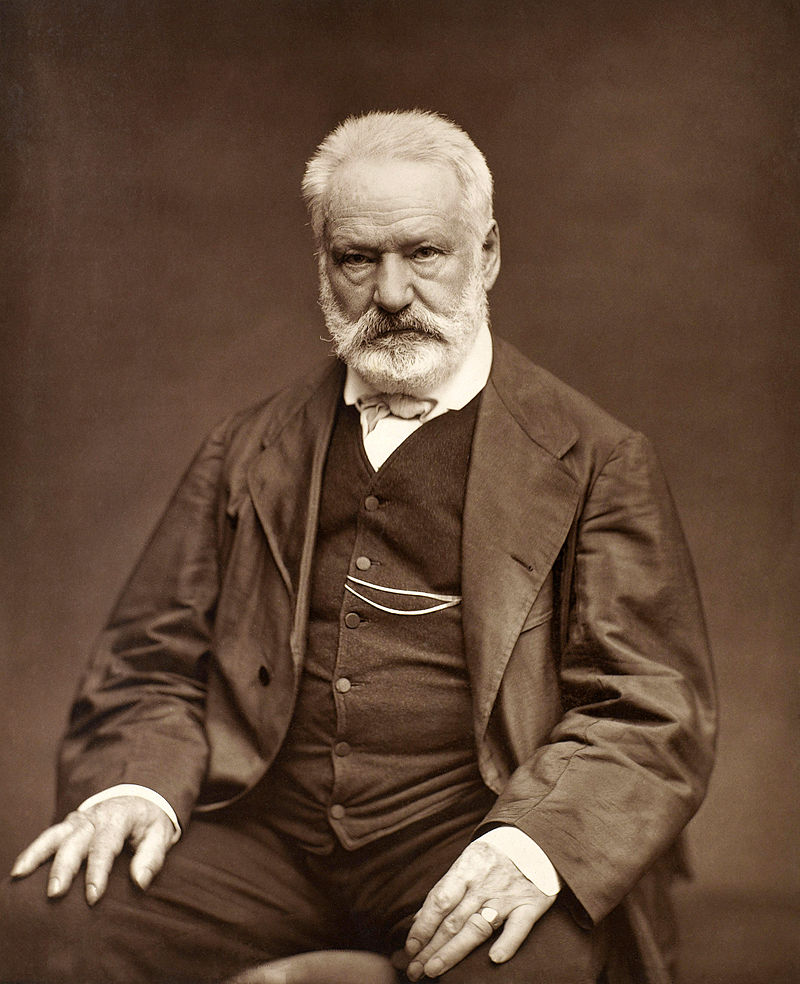

Victor Hugo, in Les Misérables, (1864) discusses the day as follows:

“…it was the second of February, that ancient Candlemas-day whose treacherous sun, the precursor of six weeks of cold, inspired Matthew Laensberg with the two lines, which have deservedly become classic:

‘Qu’il luise ou qu’il luiserne, l’ours rentre en sa caverne.‘

(Let it gleam or let it glimmer, the bear goes back into his cave.)”

Above: French writer Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

The observance of Groundhog Day in the United States first occurred in German communities in Pennsylvania, according to known records.

The earliest mention of Groundhog Day is an entry on February 2, 1840, in the diary of James L. Morris of Morgantown, in Pennsylvania Dutch Country.

The first reported news of a Groundhog Day observance was arguably made by the Punxsutawney Spirit newspaper of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, in 1886.

The largest Groundhog Day celebration is held in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, where crowds as large as 40,000 gather each year, nearly eight times the year-round population of the town which is 5,769 as of 2020.

The average draw had been about 2,000 until the 1993 film Groundhog Day, which is set at the festivities in Punxsutawney, after which attendance rose to about 10,000.

Above: Groundhog Day, Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania

This tradition, rooted in European lore, is more than mere superstition — it is a testament to humanity’s need for certainty in an uncertain world.

We seek shadows, interpreting them as omens, often reluctant to step forward without reassurance.

Yet, what do we do when the shadow is not cast by nature but by history, by our own fears, by the specters of our past?

Above: Flag of the European Union

Alexander Selkirk, marooned on an island in 1704 and rescued on February 2, 1709, lived four years in solitude, facing not only physical survival but the immense psychological weight of isolation.

His story inspired Robinson Crusoe, yet how many of us today feel stranded — waiting for rescue, for a sign, for someone to tell us which way to go?

Above: Statue of Alexander Selkirk (1676 – 1721) at the site of his original house on Main Street, Lower Largo Fife, Scotland

Alexander Selkirk was a Scottish privateer and Royal Navy officer who spent four years and four months as a castaway (1704 – 1709) after being marooned by his Captain, initially at his request, on an uninhabited island in the South Pacific Ocean.

He survived that ordeal, but died from a tropical illness (most likely yellow fever) years later while serving as a lieutenant aboard HMS Weymouth off West Africa.

Selkirk was an unruly youth and joined buccaneering voyages to the South Pacific during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 – 1714).

One such expedition was on Cinque Ports, captained by Thomas Stradling, under the overall command of William Dampier.

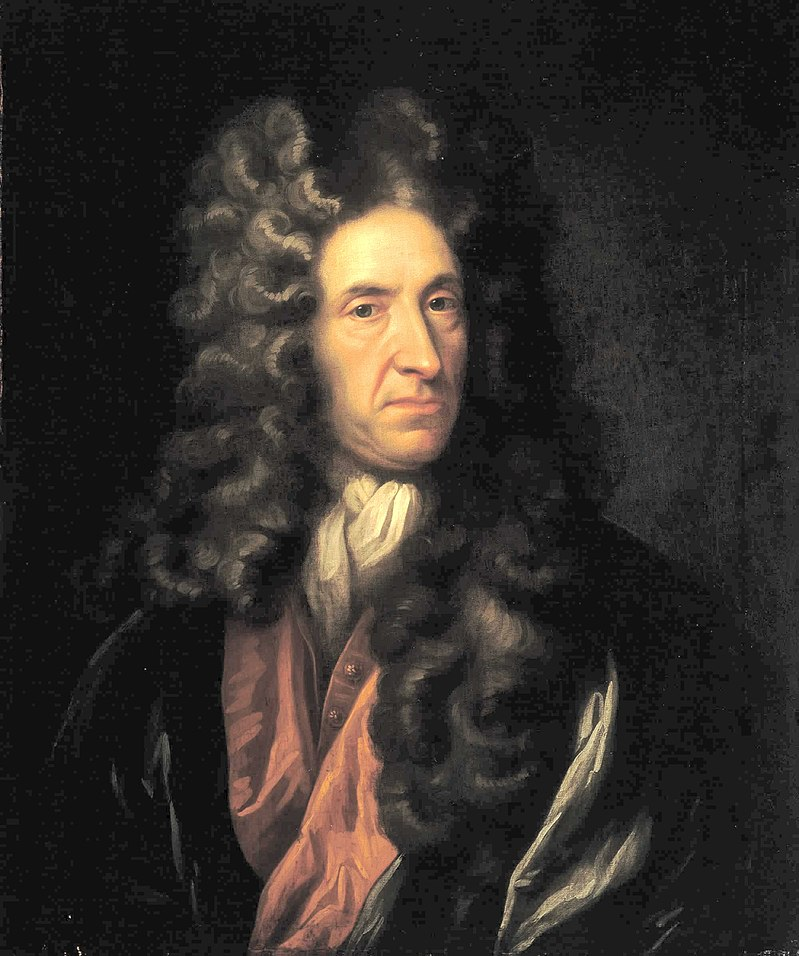

Above: English privateer William Dampier (1651 – 1715)

Stradling’s ship stopped to resupply at the uninhabited Juan Fernández Islands, west of South America.

Selkirk judged correctly that the craft was unseaworthy and asked to be left there.

Selkirk’s suspicions were soon justified, as Cinque Ports foundered near Malpelo Island 400 km (250 mi) from the coast of what is now Colombia.

Above: Malpelo Island

By the time he was eventually rescued by the privateer Woodes Rogers, who was accompanied by Dampier, Selkirk had become adept at hunting and making use of the resources that he found on the island.

Above: English privateer Woodes Rogers (1679 – 1732) receives a map of New Providence Island from his son

His story of survival was widely publicized after his return, becoming one of the reputed sources of inspiration for the English writer Daniel Defoe’s fictional character Robinson Crusoe.

Above: English writer Daniel Defoe (1660 – 1731)

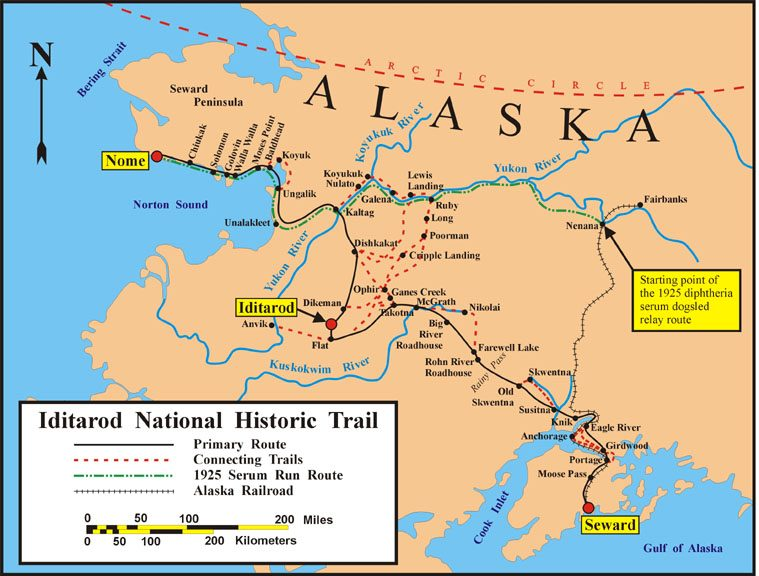

On this day in 1925, a different kind of signal raced across the frozen wilderness of Alaska — the life-saving serum run to Nome.

Dog sled teams, led by legendary canines like Balto and Togo, braved impossible conditions to deliver medicine and stave off a diphtheria outbreak.

It was a race against time, a battle where courage and resilience defied the icy grasp of death.

The 1925 serum run to Nome, also known as the Great Race of Mercy and The Serum Run, was a transport of diphtheria antitoxin by dog sled relay across the US territory of Alaska by 20 mushers and about 150 sled dogs across 674 miles (1,085 km) in 51⁄2 days, saving the small town of Nome and the surrounding communities from a developing epidemic of diphtheria.

Above: Nome, Alaska

Both the mushers and their dogs were portrayed as heroes in the newly popular medium of radio and received headline coverage in newspapers across the United States.

Balto, the lead sled dog on the final stretch into Nome, became the most famous canine celebrity of the era after Rin Tin Tin, and his statue is a popular tourist attraction in both New York City’s Central Park and downtown Anchorage, Alaska.

Above: Balto

Above: Balto statue, Central Park, New York City, New York, USA

But it was Togo’s team which covered much of the most dangerous parts of the route and ran the farthest:

Togo’s team covered 261 miles (420 km) while Balto’s team ran 55 miles (89 km).

Above: Musher Leonhard Seppala posing with six of his sled dogs, circa 1924-1925. Dogs’ names from left to right – Togo, Karinsky, Jafet, Pete, unknown dog, Fritz.

Thirty-four years later, also in the deep of winter, another group braved the snow, but with a far more tragic end.

The Dyatlov Pass Incident (1959) remains a chilling enigma — nine experienced hikers found dead in the Ural Mountains under mysterious circumstances.

Their tent slashed from within, bodies found in unnatural positions, some with inexplicable injuries.

What signal, what unseen force, drove them from their shelter into the night?

Science and speculation clash here — an avalanche, military tests, even folklore-driven fears of the supernatural.

Unlike the Nome run, where signals brought salvation, Dyatlov’s shadows led only to questions.

Above: The Mikhajlov Cemetry in Yekaterinburg. The tomb of the group who had died in mysterious circumstances in the northern Ural Mountains.

The Dyatlov Pass incident (Russian: Гибель тургруппы Дятлова, romanized: Gibel turgruppy Dyatlova, lit. ‘Death of the Dyatlov Hiking Group‘) was an event in which nine Soviet ski hikers died in the northern Ural Mountains between February 1 and 2, 1959, under uncertain circumstances.

The experienced trekking group from the Ural Polytechnical Institute, led by Igor Dyatlov, had established a camp on the eastern slopes of Kholat Syakhl in the Russian SFSR of the Soviet Union.

Above: Logo of the Ural State Technical University (USTU)

Overnight, something caused them to cut their way out of their tent and flee the campsite while inadequately dressed for the heavy snowfall and subzero temperatures.

After the group’s bodies were discovered, an investigation by Soviet authorities determined that six of them had died from hypothermia while the other three had been killed by physical trauma.

One victim had major skull damage, two had severe chest trauma, and another had a small crack in his skull.

Four of the bodies were found lying in running water in a creek, and three of these four had damaged soft tissue of the head and face – two of the bodies had missing eyes, one had a missing tongue, and one had missing eyebrows.

The investigation concluded that a “compelling natural force” had caused the deaths.

Above: A view of the tent as the rescuers found it on 26 February 1959.

The tent had been cut open from the inside, and most of the hikers had fled in socks or barefoot.

Numerous theories have been put forward to account for the unexplained deaths, including animal attacks, hypothermia, an avalanche, katabatic winds, infrasound-induced panic, military involvement, or some combination of these factors.

Russia opened a new investigation into the incident in 2019.

Its conclusions were presented in July 2020:

That an avalanche had led to the deaths.

Survivors of the avalanche had been forced to suddenly leave their camp in low-visibility conditions with inadequate clothing and had died of hypothermia.

Andrey Kuryakov, deputy head of the regional prosecutor’s office, said:

“It was a heroic struggle.

There was no panic.

But they had no chance to save themselves under the circumstances.”

A study led by scientists from EPFL and ETH Zürich, published in 2021, suggested that a type of avalanche known as a slab avalanche could explain some of the trekkers’ injuries.

A mountain pass in the area was later named “Dyatlov Pass” in memory of the group.

In many languages, the incident is now referred to as the “Dyatlov Pass incident“.

However, the incident occurred about 1,700 metres (5,600 ft) away, on the eastern slope of Kholat Syakhl.

A prominent rock outcrop in the area now serves as a memorial to the group.

It is located about 500 metres (1,600 ft) to the east-southeast of the actual site of the final camp.

Above: Tomb of the deceased at Mikhailovskoe Cemetery in Yekaterinburg, Russia

February 2, 1922, saw the publication of Ulysses, James Joyce’s sprawling, labyrinthine masterpiece.

A book dense with signals — of history, mythology, psychology —where every word carries echoes of past and future.

Ulysses is a modernist novel by the Irish writer James Joyce.

Partially serialized in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, the entire work was published in Paris by Sylvia Beach (1887 – 1962) on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s 40th birthday.

Above: American bookseller Sylvia Beach

It is considered one of the most important works of modernist literature and has been called “a demonstration and summation of the entire movement“.

The novel chronicles the experiences of three Dubliners over the course of a single day, 16 June 1904, which fans of the novel now celebrate as Bloomsday.

Ulysses is the Latinized name of Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, and the novel establishes a series of parallels between Leopold Bloom and Odysseus, Molly Bloom and Penelope, and Stephen Dedalus and Telemachus.

Above: Odysseus and the Sirens

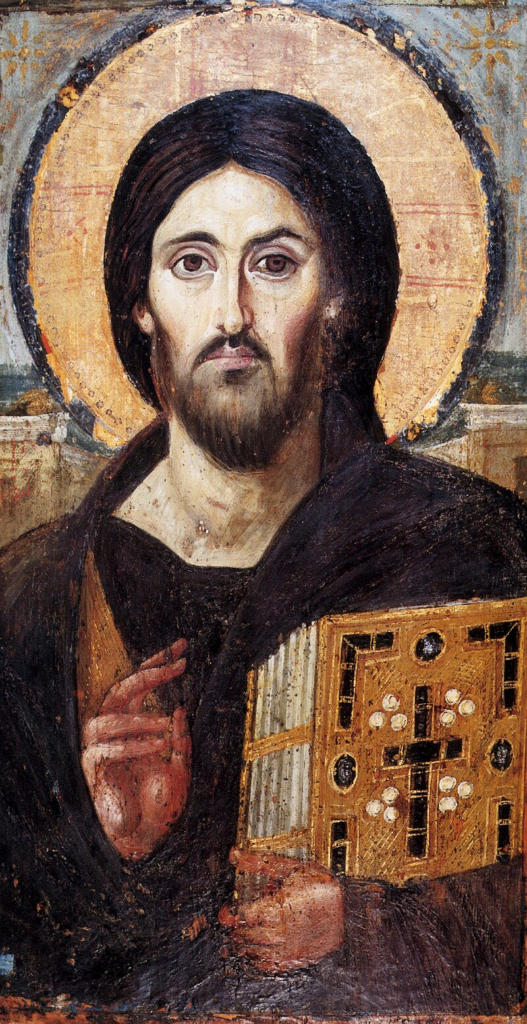

There are also correspondences with Shakespeare’s (1564 – 1616) Hamlet and with other literary and mythological figures, including Jesus (4 BC – AD 30), Elijah (d. 849 BC), Moses (13th century BC), Dante Aligheri (1265 – 1321) and Don Giovanni.

Above: English writer William Shakespeare

Above: The Christ Pantocrator of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, a 6th-century encaustic icon

Above: Elijah fed by the raven, Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo (1510)

Above: Moses with the Ten Commandments, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1659)

Above: Italian writer Dante Aligheri

Above: Don Juan, Józef Simmler (1846)

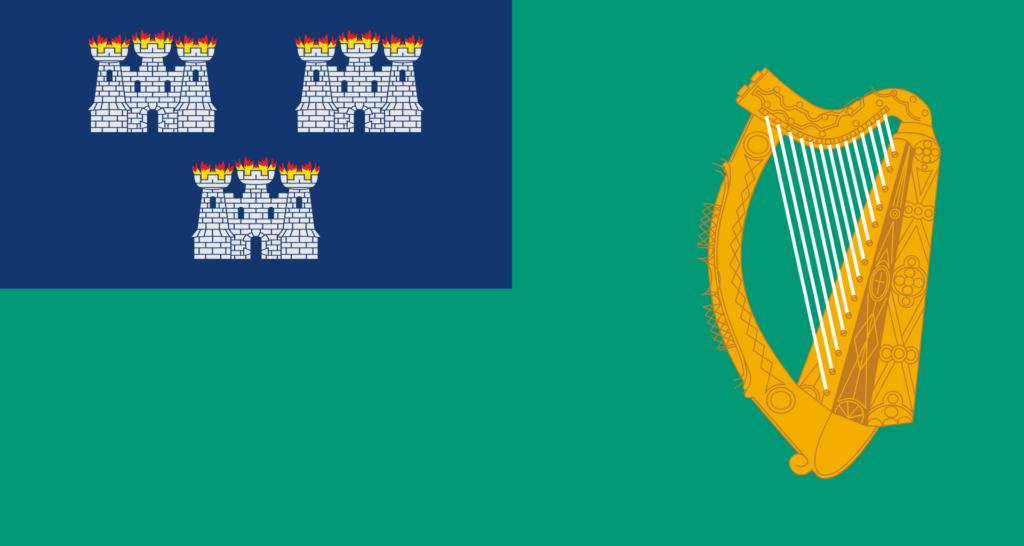

Such themes as antisemitism, human sexuality, British rule in Ireland, Catholicism and Irish nationalism are treated in the context of early 20th-century Dublin.

Above: Flag of Dublin, Ireland

The novel is highly allusive and written in a variety of styles.

Artist and writer Djuna Barnes (1892 – 1982) quoted Joyce as saying:

“The pity is the public will demand and find a moral in my book— or worse they may take it in some more serious way, and on the honour of a gentleman, there is not one single serious line in it.

In ‘Ulysses’ I have recorded, simultaneously, what a man says, sees, thinks, and what such seeing, thinking, saying does, to what you Freudians call the subconscious.“

Above: American artist Djuna Barnes

According to the writer Declan Kiberd:

“Before Joyce, no writer of fiction had so foregrounded the process of thinking“.

Above: Irish writer Declan Kiberd

The novel’s stream of consciousness technique, careful structuring, and experimental prose — replete with puns, parodies, epiphanies, and allusions — as well as its rich characterization and broad humour have led it to be regarded as one of the greatest literary works.

Since its publication, the book has attracted controversy and scrutiny, ranging from a 1921 obscenity trial in the United States to protracted disputes about the authoritative version of the text.

It is no coincidence that Joyce was born on this day in 1882, nor that Ulysses remains a beacon for those willing to decode its signals, to step beyond the immediate and embrace the unknown.

But Joyce is not alone.

Above: Irish writer James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Ayn Rand (1905), Khushwant Singh (1915), James Dickey (1923) —writers of vastly different styles and philosophies — were all born on this day, each in their own way casting shadows of influence and sending signals of thought to generations beyond them.

Writing itself is a signal, a way to bridge time, to send messages into the future, hoping someone will listen.

Above: Russian-born Ayn Rand (1905 – 1982)

Alice O’Connor (née Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand, was a Russian-born American writer and philosopher.

She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system which she named Objectivism.

Born and educated in Russia, she moved to the United States in 1926.

After two early novels that were initially unsuccessful and two Broadway plays, Rand achieved fame with her 1943 novel The Fountainhead.

In 1957, she published her best-selling work, the novel Atlas Shrugged.

Afterward, until her death in 1982, she turned to non-fiction to promote her philosophy, publishing her own periodicals and releasing several collections of essays.

Rand advocated reason and rejected faith and religion.

She supported rational and ethical egoism as opposed to altruism and hedonism.

In politics, she condemned the initiation of force as immoral and supported laissez-faire capitalism, which she defined as the system based on recognizing individual rights, including private property rights.

Although she opposed libertarianism, which she viewed as anarchism, Rand is often associated with the modern libertarian movement in the United States.

In art, she promoted romantic realism.

She was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her, with a few exceptions.

Rand’s books have sold over 37 million copies.

Her fiction received mixed reviews from literary critics, with reviews becoming more negative for her later work.

Although academic interest in her ideas has grown since her death, academic philosophers have generally ignored or rejected Rand’s philosophy, arguing that she has a polemical approach and that her work lacks methodological rigor.

Her writings have politically influenced some right-libertarians and conservatives.

The Objectivist movement circulates her ideas, both to the public and in academic settings.

Above: Grave marker for Ayn Rand and her husband at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York

Above: Indian writer Khushwant Singh (1915 – 2014)

Khushwant Singh (né Khushal Singh, 2 February 1915 – 2014) was an Indian author, lawyer, diplomat, journalist and politician.

His experience in the 1947 Partition of India inspired him to write Train to Pakistan in 1956 (made into film in 1998), which became his most well-known novel.

Born in Punjab, Khushwant Singh was educated in Modern School, New Delhi, St. Stephen’s College, and graduated from Government College, Lahore.

Above: Modern School, New Delhi, India

Above: Crest of St. Stephens College, University of Delhi, India

Above: Crest of Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan

Singh studied at King’s College London and was awarded an LL.B. from University of London.

Above: Coat of Arms of King’s College, London, England

Above: Coat of arms of the University of London

Singh was called to the bar at the London Inner Temple.

Above: Hare Court, Inner Temple, London, England

After working as a lawyer in Lahore High Court for eight years, Singh joined the Indian Foreign Service upon the Independence of India from the British Empire in 1947.

Above: Lahore High Court, Lahore, Pakistan

Above: Logo of the Indian Foreign Service

Singh was appointed journalist in the All India Radio in 1951, and then moved to the Department of Mass Communications of UNESCO at Paris in 1956.

Above: Logo of All India Radio

Above: Flag of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization)

These last two careers encouraged him to pursue a literary career.

As a writer, he was best known for his trenchant secularism, humour, sarcasm and an abiding love of poetry.

His comparisons of social and behavioural characteristics of Westerners and Indians are laced with acid wit.

He served as the editor of several literary and news magazines, as well as two newspapers, through the 1970s and 1980s.

Between 1980 and 1986 he served as Member of Parliament in Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Parliament of India.

Above: Logo of the Parliament of India

Khushwant Singh was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1974.

However, he returned the award in 1984 in protest against Operation Blue Star in which the Indian Army raided Amritsar.

Above: Golden Temple, Amritsar, India

In 2007, he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest civilian award in India.

Above: Khushwant Singh (right) receiving the Padma Vibhushan

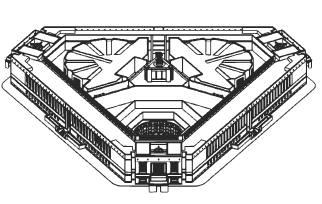

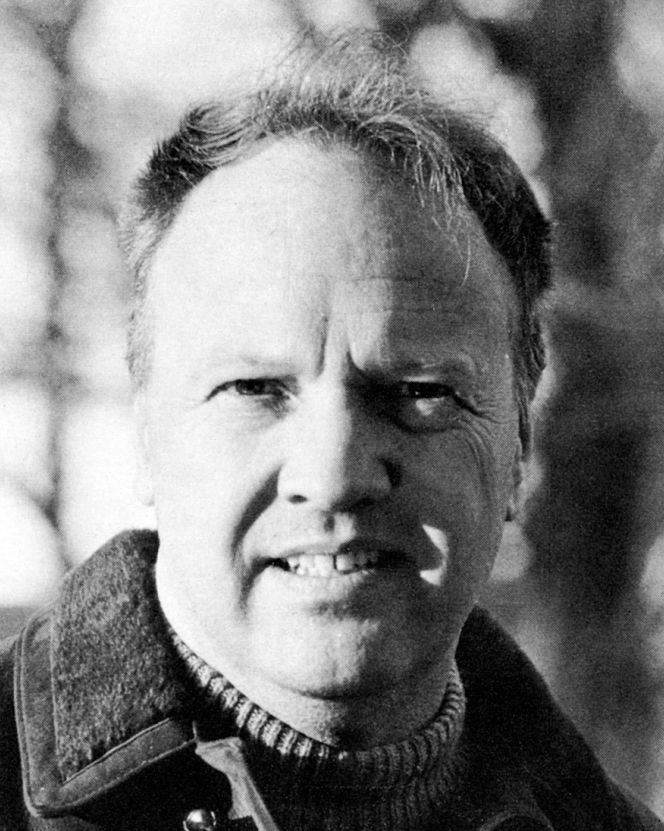

James Lafayette Dickey (February 2, 1923 – January 19, 1997) was an American poet and novelist.

He was appointed the 18th United States Poet Laureate in 1966.

He also received the Order of the South award.

Above: American writer James Dickey (1923 – 1997)

Dickey is best known for his novel Deliverance (1970), which was adapted into the acclaimed 1972 film of the same name.

On February 2, 1971, the Ramsar Convention was signed, a global effort to protect wetlands — those liminal spaces where land and water blur into one another.

Above: Logo of the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, like literature, like history, are fragile.

They absorb, they transform, they hold deep reservoirs of life and memory.

But without protection, they vanish.

The same can be said for our cultural and historical awareness.

Without careful stewardship, the signals of the past fade, and we are left blind to what came before.

Above: Freshwater swamp forest in Gowainghat of Sylhet district, Bangladesh

We are all, in some way, watching for shadows, searching for signals.

We wait for omens, for signs that will tell us whether to move forward or retreat.

Sometimes, the signals are clear — the race against time in Nome, the inked brilliance of Joyce, the cry for preservation from our vanishing wetlands.

Other times, the shadows loom — Selkirk’s exile, Dyatlov’s mystery, the fears that keep us trapped in indecision.

And so, on this February 2, we stand at the threshold between shadow and signal, between past and future.

Do we remain in the burrow?

Or do we step forward into the light, embracing both the known and the unknowable?

The answer, as always, is ours to find.