Thursday 6 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

The former head teacher, dismissed and disillusioned, lay in his restless bed, his limbs heavy with exhaustion, his thoughts a storm of injustice and regret.

Losing your job can be a hideous blow, both to the pocket and to the ego.

The best way to deal with it is to try and see it as an opportunity – a chance to take a break from the daily toil, reconsider your options and perhaps expand into new territories.

Rather than conclude that you were a bad fit, decide that the job was a bad fit for you.

If you are not convinced, consider all the occasions on which, in your job, you did not want to do the things you were asked to do.

As I tell the Tale of the Terminated Teacher, I find myself thinking of Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener.

A scrivener (or scribe) was a person who, before the advent of compulsory education, could read and write or who wrote letters as well as court and legal documents.

Scriveners were people who made their living by writing or copying written material.

This usually indicated secretarial and administrative duties such as dictation and keeping business, judicial and historical records for kings, nobles, temples and cities.

Scriveners later developed into notaries, court reporters, and in England and Wales, scrivener notaries.

They were and are generally distinguished from scribes, who in the European Middle Ages mostly copied books.

With the spread of printing this role largely disappeared, but scriveners were still required.

Styles of handwriting used by scriveners included secretary hand, book hand and court hand.

Above: Telling a problem to a public scrivener. Istanbul (1878)

Bartleby is a scrivener and when he first arrives for duty at the narrator’s law office, “pallidly neat” and “pitiably respectable“, his employer thinks his sedate nature will have a calming influence on his other employees.

And at first Bartleby does seem to be the model worker, industriously copying out letters in quadruplicate.

But then he begins to rebel.

When his employer asks him to check over his writing, Bartleby gives the response:

“I would prefer not to.”

It soon becomes apparent that he will do nothing beyond the most basic elements of his job.

If asked to do anything more, “I would prefer not to.” comes the inflexible reply.

A dire impasse develops in which the employer cannot bring himself to fire the scrivener because he is so meek and seems to have no life whatsoever beyond his desk.

Bartleby will do only what he wants.

Be inspired by Bartleby’s act of resistance.

To what degree did your job entail compromising over what you really wanted to do?

Bartleby’s rebellion saw him refusing to leave his desk at all.

You, however, now have a chance to move on and find pastures new.

But the dismissed teacher’s despair is too fresh.

He had been asked his opinion how should the teachers be paid.

The boss has the idea of saving money on taxes by shifting some of the expected salary onto a food voucher card – a card not universally accepted nor universally functional.

He had given his opinion, had offered other options, had expressed his concern that by forcing the teachers to spend their hard-earned salaries on a card not wanted would remove from them the dignity of choosing to spend their salary in the manner in which they so desired or needed.

He had gone to work hopeful that his arguments had swayed the boss, that his opinion was as truly respected as the boss had claimed it was.

But the boss had made up his mind and had paid the salaries between bank account and food voucher card.

The morning came and he was greeted by a group of unhappy teachers.

Yet, he felt that perhaps the afternoon meeting – a meeting of teachers and boss – would result in open communication that would lower the temperature of heated tempers.

Those hopes were dashed.

The teachers expressed their concerns as did the head teacher.

The boss rattled on and on as to his difficulties of financing the school, only listening for the opportunity to speak again.

No thought is given to the teachers’ difficulties trying to make ends meet in a disintegrating economy and soaring prices.

He heard their arguments, but did not listen.

He saw their faces, but would not observe their dissatisfaction.

One teacher speaks his mind and something snaps inside the boss.

Debate decays into diatribe.

How he had given them the opportunity to work for him, how some were less competent than others, how he was transparent – not seeing the hypocrisy that was belied by his already done deed – with everyone, how they were ungrateful and disrespectful, how easily they could be replaced – it is an employer’s market – and they had the choice between his way or the highway.

The thought that it was their quality of teaching and their dedication to their craft and their devotion to their students made his wealth possible would never cross his mind.

The meeting had ended.

What had been a bad situation had turned worse.

Some had stormed off.

Some had cried.

The head teacher had held some in his arms seeking words of solace in a desert of despair.

The head teacher was handicapped by a lack of Turkish to communicate with a boss lacking English – a sad reality that the owners of English language schools cannot speak the language they are selling – and so had remained silent in the communal teachers’ room, while the boss had spoken with those who shared his language.

The head teacher had then been taken from public view and summarily fired, with the blame of the teachers’ negativity placed squarely upon his shoulders.

The disgraced dismissal had then returned to the communal room, had announced his sudden departure and had gathered his possessions from his locker and the common table and was then gone.

He blamed himself.

He had openly questioned his boss’ judgment and to save face the boss had fired him.

He had stood by his principles and had paid the price.

The powerless rarely persuade the powerful.

Those in power must quelch dissent, must assert authority, regardless of the damage to the institution or to his reputation.

Better to be feared than to be loved.

He was not their friend.

He was their boss.

The teacher knew that his dismissal did not diminish his experience, did not detract from the dedication he had brought to his role.

He had acted with the best of intentions and it had led to this – sudden unemployment and uncertainty about the future.

He knew it was natural to feel sad and disappointed – he had put his heart into the position.

I find myself thinking of Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim.

Perhaps you can even begin to celebrate the demise of your job.

When Jim Dixon is appointed lecturer in Medieval English History at a nondescript university in the Midlands.

Jim has no intention of messing things up.

He duly accepts his boss Neddy Welch’s invitation to attend an “arts weekend” in the country, realizing that he needs to keep “in” with Welch, but once there, he cannot seem to avoid getting himself into trouble.

Farcical scenes ensue, including burning bed sheets, drunken madrigal singing and various sexual entanglements.

It is when he gives his lecture about “Merrie England“, however, that he blows things most spectacularly delivering the final moments “punctuated by his own snorts of derision“.

Have a much-needed laugh, then start looking for the job that is even more suited to you.

Because there is an unexpected denouement to Jim’s very public disgrace.

Seeing someone make a pig’s dinner of their job – and still come out on top – will boost your morale no end.

Once again, he had fallen into a cowboy school where teachers were disposable pawns and students merely ATMs.

His dedication to real education — not just profit — makes him stand out as a good teacher, a good man, but sadly, integrity often clashes with systems that prioritize money over learning.

He felt that he deserved better, a place that values what he had to offer.

He had acted out of care — not just for himself, but for the teachers and the integrity of education itself.

And yet, instead of appreciation, he had been met with authoritarian indifference.

That kind of leadership only breeds resentment, and while he felt like he had misread the boss, the reality is that he had been simply holding onto the hope that reason and empathy would prevail.

He told himself that this was not a failing, but rather a mark of his character.

What saddened him the most, though he told himself that from this moment on the school was “not my circus, not my monkeys“, but he had quickly grown fond of these people and that loss felt like an exile from those whom he was beginning to love.

Sleep came reluctantly, creeping upon him like a thief.

And in that uneasy slumber, the world dissolved, reforming into something else entirely — a place not of punishment, but of reckoning.

He found himself standing in a vast hall of stone and light, surrounded by high archways that defied gravity, their keystones inscribed with words he had once cherished:

Libertas, Sapientia, Veritas — Freedom, Wisdom, Truth.

At the heart of this hall, a great round table, where ghostly figures conversed with the urgency of men whose warnings had gone unheeded.

He knew them at once, not by sight, but by the weight of their words in his bones.

The teacher recognizes Ivan Illich.

Ivan Dominic Illich (1926 – 2002) was an Austrian Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic.

Above: Ivan Illich

His 1971 book Deschooling Society criticises modern society’s institutional approach to education, an approach that demotivates and alienates individuals from the process of learning.

His 1975 book Medical Nemesis, importing to the sociology of medicine the concept of medical harm, argues that industrialized society widely impairs quality of life by overcommericalizing life, pathologizing normal conditions, creating false dependency, and limiting other more healthful solutions.

Illich called himself “an errant pilgrim“.

Deschooling Society begins as a polemical work that then proposes suggestions for changes to education in society and learning in individual lifetimes.

For example, he calls for the use of advanced technology to support “learning webs“, which incorporate “peer-matching networks“, where descriptions of a person’s activities and skills are mutually exchanged for the education that they would benefit from.

Illich argued that, with an egalitarian use of technology and a recognition of what technological progress allows, it would be warranted to create decentralized webs that would support the goal of a truly equal educational system:

A good educational system should have three purposes:

- It should provide all who want to learn with access to available resources at any time in their lives

- Empower all who want to share what they know to find those who want to learn it from them

- And, finally, furnish all who want to present an issue to the public with the opportunity to make their challenge known.“

Illich proposes a system of self-directed education in fluid and informal arrangements, which he describes as “educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring“.

Furthermore, he states:

Universal education through schooling is not feasible.

It would be no more feasible if it were attempted by means of alternative institutions built on the style of present schools.

Neither new attitudes of teachers toward their pupils nor the proliferation of educational hardware or software (in classroom or bedroom) nor finally the attempt to expand the pedagogue’s responsibility until it engulfs his pupils’ lifetimes will deliver universal education.

The current search for new educational funnels must be reversed into the search for their institutional inverse:

Educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring.

We hope to contribute concepts needed by those who conduct such counterfoil research on education — and also to those who seek alternatives to other established service industries.”

Illich’s view that education’s institutionalization fosters society’s institutionalization, and so de-institutionalizing education may help de-institutionalize society.

Further, Illich suggests reinventing learning and expanding it throughout society and across persons’ lifespans.

Once again, most influential was his 1971 call for advanced technology to support “learning webs“:

The operation of a peer-matching network would be simple.

The user would identify himself by name and address and describe the activity for which he sought a peer.

A computer would send him back the names and addresses of all those who had inserted the same description.

It is amazing that such a simple utility has never been used on a broad scale for publicly valued activity.“

According to a review in the Libertarian Forum (1969 – 1984):

“Illich’s advocacy of the free market in education is the bone in the throat that is choking the public educators.“

Yet, unlike libertarians, Illich opposes not merely publicly funded schooling, but schools as such.

Thus, Illich’s envisioned disestablishment of schools aimed not to establish a free market in educational services, but to attain a fundamental shift:

A de-schooled society.

In his 1973 book After Deschooling, What?, he asserted:

“We can disestablish schools, or we can de-school culture.”

In fact, he called advocates of free-market education “the most dangerous category of educational reformers.“

Developing this idea, Illich proposes four Learning Networks:

- Reference Service to Educational Objects – An open directory of educational resources and their availability to learners.

- Skills Exchange – A database of people willing to list their skills and the basis on which they would be prepared to share or swap them with others.

- Peer-Matching – A network helping people to communicate their learning activities and aims in order to find similar learners who may wish to collaborate.

- Directory of Professional Educators – A list of professionals, paraprofessionals and free-lancers detailing their qualifications, services and the terms on which these are made available.

Ivan Illich spoke first, his voice carrying the sorrow of lost possibility:

“You see, my friend, schools were never meant to liberate.

They were built to enclose, to regulate, to ensure that the mind does not wander too far.

De-schooling is not destruction.

It is the path to knowledge unchained.”

Above: Ivan Illich

The teacher sees Paulo Freire.

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire (1921 – 1997) was a Brazilian educator and philosopher who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy.

Above: Paulo Freire

His influential work Pedagogy of the Oppressed is generally considered one of the foundational texts of the critical pedagogy movement.

It was the third most cited book in the social sciences as of 2016 according to Google Scholar.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Portuguese: Pedagogia do Oprimido) is a book by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, written in Portuguese between 1967 and 1968, but published first in Spanish in 1968.

An English translation was published in 1970, with the Portuguese original being published in 1972 in Portugal, and then again in Brazil in 1974.

The book is considered one of the foundational texts of critical pedagogy, and proposes a pedagogy with a new relationship between teacher, student and society.

Dedicated to the oppressed and based on his own experience helping Brazilian adults to read and write, Freire includes a detailed Marxist class analysis in his exploration of the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized.

In the book, Freire calls traditional pedagogy the “banking model of education” because it treats the student as an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge, like a piggy bank.

Above: The banking model of education often places learners in a position to receive lectures by the teacher positioned as expert.

Freire argues that pedagogy should instead treat the learner as a co-creator of knowledge.

As of 2000, the book had sold over 750,000 copies worldwide.

Due to the 1964 Brazilian coup d’état, where a military dictatorship was put in place with the support of the United States, Paulo Freire was exiled from his home country, an exile that lasted 16 years.

Above: M41 tank and two jeeps of the Brazilian Army in the Ministries Esplanade, near the National Congress Palace (background) in Brasília, Brazil, 1964

Above: Flag of Brazil

After a brief stay in Bolivia, he moved to Chile in November 1964 and stayed until April 1969 when he accepted a temporary position at Harvard University.

His four-and-a-half year stay in Chile impacted him intellectually, pedagogically, and ideologically, and contributed significantly to the theory and analysis he presents in Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

In Freire’s own words:

When I wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed I was already completely convinced of the problem of social classes.

In addition, I wrote this book on the basis of my extensive experience with peasants in Chile.

Being absolutely convinced of the process of ideological hegemony and what that meant.

When I would hear the peasants speaking, I experienced the whole problem of the mechanism of domination.

Certainly, in my earliest writings I did not make this explicit, because I did not perceive it yet as such.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is also completely situated in a historical reality.

Above: Flag of Chile

Freire wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed between 1967 and 1968, while living in the United States.

Originally written in his native Portuguese, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was first published in Spanish in 1968.

This was followed by an English version, in a translation by Myra Bergman Ramos, in 1970.

The Portuguese original was released in Portugal in 1972 and in Brazil in 1974.

Though Ramos’ translation has received some degree of criticism, Freire approved of it and was involved in consultation during the translating process.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is divided into four chapters and a preface.

The front matter includes an epigraph that reads:

“To the oppressed, and to those who suffer with them and fight at their side“.

In the preface, Freire provides a background to his work and outlines potential opposition to his ideas.

He explains that his thinking originated in his experience as a teacher, both in Brazil and during his time in political exile.

During this time, he noticed that his students had an unconscious fear of freedom, or rather:

A fear of changing the way the world is.

Freire then outlines the likely criticisms he believes his book will face.

Freire’s intended audience is radicals — people who see the world as changing and fluid — and he admits that his argument will most likely be missing necessary elements to construct pedagogies in given material realities.

Basing his method of finding freedom on the poor and middle class’s experience with education, Freire states that his ideas are rooted in reality—not purely theoretical.

In the first chapter, Freire outlines why he believes an emancipatory pedagogy is necessary.

Describing humankind’s central problem as that of affirming one’s identity as human, Freire states that everyone strives for this, but oppression prevents many people from realizing this state of affirmation.

This is termed dehumanization.

Dehumanization, when individuals become objectified, occurs due to injustice, exploitation, and oppression.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is Freire’s attempt to help the oppressed fight back to regain their lost humanity and achieve full humanization.

Freire outlines steps with which the oppressed can regain their humanity, starting with acquiring knowledge about the concept of humanization itself.

It is easy for the oppressed to fight their oppressors, only to become the opposites of what they currently are. In other words, this just makes them the oppressors and starts the cycle all over again.

To be fully human again, they must identify the oppressors.

They must identify them and work together to seek liberation.

The next step in liberation is to understand what the goal of the oppressors is.

Oppressors are purely materialistic.

They see humans as objects and by suppressing individuals, they can own these humans.

While they may not be consciously putting down the oppressed, they value ownership over humanity, essentially dehumanizing themselves.

This is important to realize, as the goal of the oppressed is to not only gain power.

It is to allow all individuals to become fully human so that no oppression can exist.

Freire states that once the oppressed understand their oppression and discover their oppressors, the next step is dialogue, or discussion with others to reach the goal of humanization.

Freire also highlights other events on this journey that the oppressed must undertake.

There are many situations that the oppressed must be wary of.

For example, they must be aware of the oppressors trying to help the oppressed.

These people are deemed falsely generous, and to help the oppressed, one must first fully become the oppressed, mentally and environmentally.

Only the oppressed can allow humanity to become fully human with no instances of objectification.

In chapter 2, Freire outlines his theories of education.

The first discussed is the banking model of education.

He believes the fundamental nature of education is to be narrative.

There is one individual reciting facts and ideas (the teacher) and others who just listen and memorize everything (the students).

There is no connection with their real life, resulting in a very passive learning style.

This form of education is termed the banking model of education.

The banking model is very closely linked with oppression.

It is built on the fact that the teacher knows all and there exist inferiors who must just accept what they are told.

They are not allowed to question the world or their teachers.

This lack of freedom highlights the comparisons between the banking model of education and oppression.

Freire urges the dismissal of the banking model of education and the adoption of the problem-posing model.

This model encourages a discussion between teacher and student.

It blurs the line between the two as everyone learns alongside each other, creating equality and the lack of oppression.

There are many ways the banking model of education aligns with oppression.

Essentially, it dehumanizes the student.

If they are raised to learn to be blank slates molded by the teacher, they will never be able to question the world if they need to.

This form of education encourages them to just accept what is thrust upon them and accept that as correct.

It makes the first step of humanization very difficult.

If they are trained to be passive listeners, they will never be able to realize that there even exist oppressors.

Chapter 3 is used to expand on Freire’s idea of dialogue.

He first explains the importance of words, and that they must reflect both action and reflection.

Dialogue is an understanding between different people.

It is an act of love, humility and faith.

It provides others with the complete independence to experience the world and name it how they see it.

Freire explains that educators shape how students see the world and history.

They must use language with the point of view of the students in mind.

They must allow “thematic investigation“:

The discovery of different relevant problems (limited situations) and ideas for different periods.

This ability is the difference between animals and humans.

Animals are stuck in the present, unlike humans who understand history and use it to shape the present.

Freire explains that the oppressed usually are not able to see the problems of their own time, and oppressors feed on this ignorance.

Freire also stresses the importance of educators not becoming oppressors and not objectifying their students.

Educators and students must work as a team to find the problems of history and the present.

Freire lays out the process of how the oppressed can truly liberate themselves in chapter 4.

He explains the methods used by oppressors to suppress humanity and the actions the oppressed can take to liberate humanity.

The tools the oppressors use are termed “anti-dialogical actions” and the ways the oppressed can overcome them are “dialogical actions“.

The four anti-dialogical actions include conquest, manipulation, divide and rule, and cultural invasion.

The four dialogical actions, on the other hand, are unity, compassion, organization and cultural synthesis.

Paulo Freire nodded, his hands folded as if in silent prayer.

“And what has become of the students?

They do not learn — they store.

They do not think — they recite.

The oppressors have convinced them that their worth is measured in certificates, in letters on a page, rather than the fire of their own questioning.”

The teacher acknowledges John Taylor Gatto.

John Taylor Gatto (1935 – 2018) was an American author and school teacher.

After teaching for nearly 30 years he authored several books on modern education, criticizing its ideology, history, and consequences.

Above: John Taylor Gatto

He is best known for his books Dumbing Us Down: the Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling and The Underground History of American Education: A Schoolteacher’s Intimate Investigation Into the Problem of Modern Schooling which criticize the modern education system and promote the concept of unschooling and a return to homeschooling.

Gatto asserts the following regarding what school does to children in Dumbing Us Down:

- It confuses the students.

It presents an incoherent ensemble of information that the child needs to memorize to stay in school.

Apart from the tests and trials, this programming is similar to the television. It fills almost all the “free” time of children.

One sees and hears something, only to forget it again.

- It teaches them to accept their class affiliation.

- It makes them indifferent.

- It makes them emotionally dependent.

- It makes them intellectually dependent.

- It teaches them a kind of self-confidence that requires constant confirmation by experts (provisional self-esteem).

- It makes it clear to them that they cannot hide, because they are always supervised.

John Taylor Gatto leaned forward, his eyes alight with the mischief of a man who had long since abandoned decorum.

“Obedience, my dear friends, is the currency of modern education.

We do not create minds.

We manufacture cogs.

The schools are not broken — they function exactly as they were designed.”

Eric Blair, better known as George Orwell, rose to his feet.

Eric Arthur Blair (1903 – 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell.

His work is characterized by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to all totalitarianism (both authoritarian communism and fascism), and support of democratic socialism.

Above: George Orwell

Orwell is best known for his allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), although his works also encompass literary criticism, poetry, fiction and polemical journalism.

His non-fiction works, including The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), documenting his experience of working-class life in the industrial north of England, and Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences soldiering for the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), are as critically respected as his essays on politics, literature, language and culture.

Orwell’s work remains influential in popular culture and in political culture, and the adjective “Orwellian” — describing totalitarian and authoritarian social practices — is part of the English language, like many of his neologisms, such as “Big Brother“, “Thought Police“, “Room 101“, “Newspeak“, “memory hole“, “doublethink“, and “thoughtcrime“.

In 2008, The Times named Orwell the second-greatest British writer since 1945.

Above: George Orwell

Orwell stated in “Why I Write” (1946):

“Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.“

Down and Out in Paris and London is the first full-length work by the English author George Orwell, published in 1933.

It is a memoir in two parts on the theme of poverty in the two cities.

Its target audience was the middle- and upper-class members of society — those who were more likely to be well educated — and it exposes the poverty existing in two prosperous cities:

Paris and London.

The first part is an account of living in near-extreme poverty and destitution in Paris and the experience of casual labour in restaurant kitchens.

The second part is a travelogue of life on the road in and around London from the tramp’s perspective, with descriptions of the types of hostel accommodation available and some of the characters to be found living on the margins.

Keep the Aspidistra Flying, first published in 1936, is a socially critical novel by George Orwell set in 1930s London.

The main theme is Gordon Comstock’s romantic ambition to defy worship of the money-god and status, and the dismal life that results.

The Road to Wigan Pier is a book by the English writer George Orwell, first published in 1937.

The first half of this work documents his sociological investigations of the bleak living conditions among the working class in Lancashire and Yorkshire in the industrial north of England before World War II.

The second half is a long essay on his middle-class upbringing, and the development of his political conscience, questioning British attitudes towards socialism.

Orwell states plainly that he himself is in favour of socialism, but feels it necessary to point out reasons why many people who would benefit from socialism, and should logically support it, are in practice likely to be strong opponents.

The book grapples with the social and historical reality of Depression suffering in the north of England – Orwell does not wish merely to enumerate evils and injustices, but to break through what he regards as middle-class oblivion – Orwell’s corrective to such falsity comes first by immersion of his own body – a supreme measure of truth for Orwell – directly into the experience of misery.

Coming Up for Air is the 7th book and 4th novel by the English writer George Orwell, published in June 1939.

It was written between 1938 and 1939 while Orwell spent time recuperating from illness in French Morocco, mainly in Marrakesh.

The story follows George Bowling, a 45-year-old husband, father, and insurance salesman, who foresees World War II and attempts to recapture idyllic childhood innocence and escape his dreary life by returning to Lower Binfield, his birthplace.

The novel is comical and pessimistic, with its views that speculative builders, commercialism and capitalism are killing the best of rural England, and that his country is facing the sinister appearance of new, external national threats.

The book’s themes are nostalgia, the folly of trying to go back and recapture past glories, and the easy way the dreams and aspirations of one’s youth can be smothered by the humdrum routine of work, marriage, and getting old. It is written in the first person, with George Bowling, the forty-five-year-old protagonist, who reveals his life and experiences while undertaking a trip back to his boyhood home as an adult.

At the book’s opening, Bowling has a day off work to go to London to collect a new set of false teeth.

A news poster about the contemporary King Zog of Albania sets off thoughts of a biblical character Og, King of Bashan, whom he recalls from Sunday church as a child.

Along with ‘some sound in the traffic or the smell of horse dung or something‘, these thoughts trigger Bowling’s memory of his childhood as the son of an unambitious seed merchant in “Lower Binfield” near the River Thames.

Bowling relates his life history, dwelling on how a lucky break during the First World War landed him a comfortable job away from any action and provided contacts that helped him become a successful salesman.

Bowling is wondering what to do with a modest sum of money that he has won on a horserace and which he has concealed from his wife and family.

Bowling decides to use the money on a ‘trip down memory lane‘ to revisit the places of his childhood.

He recalls a pond with giant fish, which he had missed the chance to try and catch 30 years previously.

He, therefore, plans to return to Lower Binfield, but when he arrives, he finds the place unrecognizable.

Eventually, he locates the old pub where he is to stay, finding it much changed.

His home has become a tea shop.

Only the church and vicar appear the same, but he is shocked when he discovers an old girlfriend, for she has been so ravaged by the time that she is almost unrecognizable and utterly devoid of the qualities he once had adored.

She fails to recognize him at all.

Bowling remembers the slow and painful decline of his father’s seed business – resulting from the nearby establishment of corporate competition.

This painful memory seems to have sensitized him to – and given him a repugnance for – what he sees as the marching ravages of “Progress“.

The final disappointment is that the estate where he used to fish has been built over, and the secluded and once-hidden pond that contained the huge carp he constantly intended to take on with his fishing rod but never got around to has become a rubbish dump.

The social and material changes experienced by Bowling since childhood make his past seem distant.

The concept of “you can’t go home again” hangs heavily over Bowling’s journey as he realizes that many of his old haunts are gone or considerably changed from his younger years.

Throughout the adventure, he receives reminders of impending war, and the threat of bombs becomes real when one lands accidentally on the town.

“Politics and the English Language” (1946) is an essay by George Orwell that criticized the “ugly and inaccurate” written English of his time and examined the connection between political orthodoxies and the debasement of language.

The essay focused on political language, which, according to Orwell, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind“.

Orwell believed that the language used was necessarily vague or meaningless because it was intended to hide the truth rather than express it.

This unclear prose was a “contagion” which had spread to those who did not intend to hide the truth, and it concealed a writer’s thoughts from himself and others.

Orwell encourages concreteness and clarity instead of vagueness, and individuality over political conformity.

Orwell relates what he believes to be a close association between bad prose and oppressive ideology:

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible.

Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties.

Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.

Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets:

This is called pacification.

Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry:

This is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers.

People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps:

This is called elimination of unreliable elements.

Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

One of Orwell’s points is:

The great enemy of clear language is insincerity.

When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.”

The insincerity of the writer perpetuates the decline of the language as people (particularly politicians, Orwell later notes) attempt to disguise their intentions behind euphemisms and convoluted phrasing.

Orwell says that this decline is self-perpetuating.

He argues that it is easier to think with poor English because the language is in decline.

And, as the language declines, “foolish” thoughts become even easier, reinforcing the original cause:

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks.

It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language.

It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier to have foolish thoughts.“

Orwell discusses “pretentious diction” and “meaningless words“.

“Pretentious diction” is used to make biases look impartial and scientific, while “meaningless words” are used to stop the reader from seeing the point of the statement.

According to Orwell:

“In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism, it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning.“

Orwell notes that writers of modern prose tend not to write in concrete terms but use a “pretentious Latinized style“.

He claims writers find it is easier to gum together long strings of words than to pick words specifically for their meaning — particularly in political writing, where Orwell notes that “orthodoxy seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style“.

Political speech and writing are generally in defence of the indefensible and so lead to a euphemistic inflated style.

Orwell criticizes bad writing habits which spread by imitation.

He argues that writers must think more clearly because thinking clearly “is a necessary first step toward political regeneration“.

He later emphasises that he was not “considering the literary use of language, but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought“.

As a further example, Orwell “translates” Ecclesiastes 9:11:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill, but time and chance happeneth to them all.

– into “modern English of the worst sort“:

Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.“

Orwell points out that this “translation” contains many more syllables but gives no concrete illustrations, as the original did, nor does it contain any vivid, arresting images or phrases.

The headmaster’s wife at St Cyprian’s School, Mrs. Cicely Vaughan Wilkes (nicknamed “Flip“), taught English to Orwell and used the same method to illustrate good writing to her pupils.

She would use simple passages from the King James Bible and then “translate” them into poor English to show the clarity and brilliance of the original.

Orwell said it was easy for his contemporaries to slip into bad writing of the sort he had described and that the temptation to use meaningless or hackneyed phrases was like a “packet of aspirins always at one’s elbow“.

In particular, such phrases are always ready to form the writer’s thoughts, to save the writer the bother of thinking — or writing —clearly.

He did conclude though that the progressive decline of the English language was reversible and suggested six rules he claimed would prevent many of these faults, although “one could keep all of them and still write bad English“.

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(Examples that Orwell gave included ring the changes, Achilles’ heel, swan song and hotbed.

He described such phrases as “dying metaphors” and argued that they were used without knowing what was truly being said.

Furthermore, he said that using metaphors of this kind made the original meaning of the phrases meaningless because those who used them did not know their original meaning.

He wrote that “some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning without those who use them even being aware of the fact“.)

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

“The Prevention of Literature” is an essay published in 1946 by the English author George Orwell.

The essay is concerned with freedom of thought and expression, particularly in an environment where the prevailing orthodoxy in left-wing intellectual circles is in favour of the Communism of the Soviet Union.

Orwell introduces his essay by recalling a meeting of the PEN Club, held on the 300-year anniversary of Milton’s Areopagitica in defence of freedom of the press, in which the speakers appeared to be interested primarily in issues of obscenity and in presenting eulogies of Soviet Russia and concludes that it was really a demonstration in favour of censorship.

In a footnote he acknowledges that he probably picked a bad day, but this provides an opportunity for Orwell to discuss attacks on freedom of thought and the enemies of intellectual liberty.

He declares the immediate enemies of freedom of thought in England to be the concentration of the press in a few hands, monopoly of radio, bureaucracy and the unwillingness of the public to buy books.

However he is more concerned with the independence of writers being undermined by those who should be its defenders.

What is at issue is the right to report contemporary events truthfully.

He notes that 15 years previously it had been necessary to defend freedom against Conservatives and Catholics, but now it was now necessary to defend it against Communists and fellow-travellers declaring that there is “no doubt about the poisonous effect of the Russian mythos on English intellectual life“.

Orwell cites the Ukrainian famine, the Spanish Civil War and Poland as topics that the pro-Soviet writers fail to address because of the prevailing orthodoxy and sees organized lying as integral to totalitarian states.

Orwell notes that prose literature is unable to flourish under totalitarianism just as it was unable to flourish under the oppressive religious culture of the Middle Ages.

However, there is a difference which is that under totalitarianism the doctrines are unstable, so that the lies always have to change to keep up with a continual re-writing of the past.

This is leading to an age of schizophrenia rather than an age of faith.

Orwell suggests that, for various reasons, poetry can survive under totalitarianism, whereas prose writers are crippled by the destruction of intellectual liberty.

Speculating on the type of literature under a future totalitarian society Orwell predicts this to be formulaic and low grade sensationalism, but notes that one factor is that general populace is not prepared to spend as much on literature as on other recreations.

In criticising the Russophile intelligentsia, Orwell complains of the uncritical and indifferent attitude of scientists, who anyway have a privileged place under totalitarian states.

For Orwell, literature is doomed if liberty of thought perishes, but the direct attack on intellectuals is coming from intellectuals themselves.

“In our age the idea of intellectual liberty is under attack from two directions.

On the one side are its theoretical enemies, the apologists of totalitarianism, and on the other its immediate, practical enemies, monopoly and bureaucracy.

Any writer or journalist who wants to retain his integrity finds himself thwarted by the general drift of society rather than by active persecution.

The journalist is unfree, and is conscious of unfreedom, when he is forced to write lies or suppress what seems to him important news:

The imaginative writer is unfree when he has to falsify his subjective feelings, which from his point of view are facts.

He may distort and caricature reality in order to make his meaning clearer, but he cannot misrepresent the scenery of his own mind.

Political writing in our time consists almost entirely of prefabricated phrases bolted together like the pieces of a child’s Meccano set.

It is the unavoidable result of self-censorship.

To write in plain vigorous language one has to think fearlessly, and if one thinks fearlessly one cannot be politically orthodox.“

At Gatto’s remark, George Orwell let out a quiet, knowing laugh.

“And do you expect the system to correct itself?

Corruption is not a flaw — it is the foundation.

The administrators, the politicians — they know precisely what they do.”

Christopher Hitchens is in the room.

Christopher Eric Hitchens (1949 – 2011) was a British-born American author and journalist.

He was the author of 18 books on faith, religion, culture, politics and literature.

Above: Christopher Hitchens

He was born and educated in Britain, graduating in the 1970s from Oxford with a degree in philosophy, politics and economics.

In the early 1980s, he emigrated to the US and wrote for The Nation and Vanity Fair.

He gained prominence as a columnist and speaker.

His epistemological razor, which states that “what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence“, is still of mark in philosophy and law.

Hitchens’s political views evolved greatly throughout his life.

Originally describing himself as a democratic socialist, he was a member of various socialist organizations in his early life, including the Trotskyist International Socialists.

Above: Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky (1879 – 1940)

Hitchens was critical of aspects of American foreign policy, including its involvement in Vietnam, Chile and East Timor.

Above: Flag of Vietnam

Above: Flag of East Timor

Above: Flag of Kosovo

However, he also supported the United States in the Kosovo War.

Hitchens emphasized the centrality of the American Revolution and Constitution to his political philosophy.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

He held complex views on abortion:

Being ethically opposed to it in most instances and believing that a fetus was entitled to personhood, while holding ambiguous, changing views on its legality.

He supported gun rights.

He supported same-sex marriage, while opposing the war on drugs.

Beginning in the 1990s, and particularly after 9/11, his politics were widely viewed as drifting to the right, but Hitchens objected to being called ‘conservative‘.

Above: Images of 11 September 2001

During the 2000s, he argued for the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, endorsed the re-election campaign of US President George W. Bush in 2004, and viewed Islamism as the principal threat to the Western world.

Above: Flag of Iraq

Above: Flag of Afghanistan

Above: US President George W. Bush (r. 2001 – 2009)

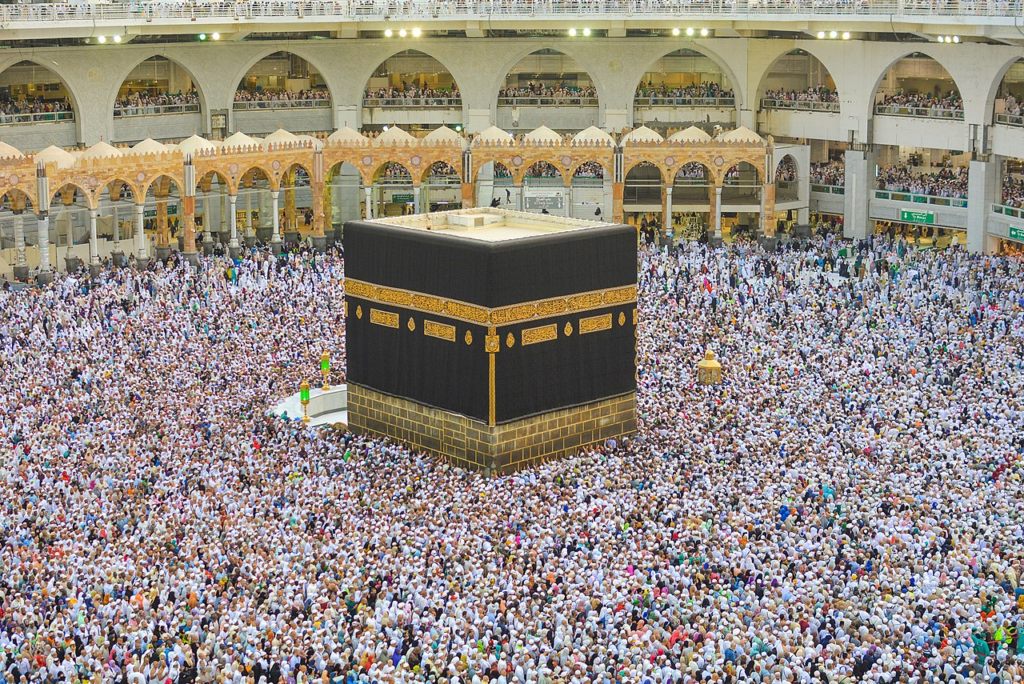

Above: The Kaaba, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during Hajj

Hitchens described himself as an anti-theist and saw all religions as false, harmful and authoritarian.

He endorsed free expression, scientific scepticism, and separation of church and state, arguing science and philosophy are superior to religion as an ethical code of conduct for human civilization.

Hitchens notably wrote critical biographies of Catholic nun Mother Teresa in The Missionary Position, President Bill Clinton in No One Left to Lie To, and American diplomat Henry Kissinger in The Trial of Henry Kissinger.

Hitchens died from complications related to oesophageal cancer in December 2011, at the age of 62.

Above: Christopher Hitchens

Letters to a Young Contrarian is Christopher Hitchens’ contribution, released in November 2001, to the Art of Mentoring series published by Basic Books.

Inspired by his students at The New School in New York City and “a challenge that was made to me in the early months of the year 2000“, the book is addressed directly to the reader — “My Dear X” — as a series of missives exploring a range of “contrarian“, radical, independent or “dissident” positions, and advocating the attitudes best suited to cultivating and to holding them.

Hitchens touches on his own ideological development, the nature of debate and humour, the ways in which language is slyly manipulated in apology for offensive and ridiculous positions, and how to see through this and recognize it whenever it arises in oneself.

Throughout, Hitchens makes reference to those dissenters who have inspired him over the years, including Émile Zola, Rosa Parks, George Orwell, Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke, and Václav Havel.

Above: French writer Émile Zola (1840 – 1902)

Above: American activist Rosa Parks (1913 – 2005)

Above: English poet and courtier Sir Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554 – 1628)

Above: Czech President Václav Havel (1936 – 2011)

The book also contains some of the critiques of religion and religious belief which Hitchens would later develop in his polemic God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything.

Why Orwell Matters, released in the UK as Orwell’s Victory, is a book-length biographical essay by Christopher Hitchens.

In it, the author relates George Orwell’s thoughts on and actions in relation to: the British Empire, the Left, the Right, the United States of America, English conventions, feminism, and his controversial list for the British Foreign Office.

Orwell never traveled to the US as he had little interest in it.

He was suspicious of the consumerist and materialistic culture.

He was somewhat resentful of its imperial ambitions and overly critical about its size and vulgarity.

Orwell did take American literature seriously, he recognized its success with the incomplete struggle for liberty, and discussed it on the BBC.

Near the end of his life when his health was failing due to tuberculosis, he began to have a change of heart towards America.

Orwell wrote about Jack London’s life and works and had a great appreciation for them.

Above: American writer Jack London (1876 – 1916)

He began to realize the appeal for North America’s vast land and fierce individualism.

Orwell’s admirers from the States urged him to visit them.

There were many suitable climates for his health and the streptomycin that might have healed his lungs was only manufactured and easily distributed in America.

Orwell briefly contemplated spending some time in the South writing, but he was too weak to visit.

Hitchens thinks that if Orwell had lived another ten years he would have visited the US after being persuaded by his friends in New York.

Orwell understood the importance of Thomas Paine and having a constitution.

His references to American history and American ideals are scarce but quite accurate.

Hitchens writes:

‘The American subject was in every sense Orwell’s missed opportunity.‘

Above: English writer Thomas Paine (1737 – 1809)

According to Hitchens, Orwell is still very modern because he writes about things relevant to today like machinery, modern tyranny and warfare, psychiatry.

Orwell’s style is fresh, clear, and persuasive. He managed to do this while dying of tuberculosis.

Hitchens:

“Power is only what you allow it to be.

You can resolve not to be a citizen like that, not to do the work of power for it.

The reading of Orwell is not an exercise in projecting blame on others but is an exercise in accepting a responsibility for yourself and it’s for that reason that he’ll always be honored and also hated. I think he wouldn’t have it any other way.“

Christopher Hitchens, glass in hand, tilted his head, unimpressed.

“The real tragedy is that we have allowed education to become a commodity, a product to be purchased.

The higher the fee, the greater the illusion of enlightenment.”

Above: Christopher Hitchens

The teacher sees Noam Chomsky and the writer does not seem happy.

Avram Noam Chomsky is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism.

Sometimes called “the father of modern linguistics“, Chomsky is also a major figure in analytic philosophy and one of the founders of the field of cognitive science.

He is a laureate professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona and an institute professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Above: Seal of the University of Arizona

Among the most cited living authors, Chomsky has written more than 150 books on topics such as linguistics, war, and politics.

In addition to his work in linguistics, since the 1960s Chomsky has been an influential voice on the American left as a consistent critic of US foreign policy, contemporary capitalism and corporate influence on political institutions and the media.

Above: Noam Chomsky

Born to Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia, Chomsky developed an early interest in anarchism from alternative bookstores in New York City.

Above: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

He studied at the University of Pennsylvania.

Above: Banner of University of Pennsylvania

During his postgraduate work in the Harvard Society of Fellows, Chomsky developed the theory of transformational grammar for which he earned his doctorate in 1955.

Above: Harvard University coat of arms

That year he began teaching at MIT, and in 1957 emerged as a significant figure in linguistics with his landmark work Syntactic Structures, which played a major role in remodeling the study of language.

From 1958 to 1959, Chomsky was a National Science Foundation (NSF) fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study.

He created or co-created the universal grammar theory, the generative grammar theory, the Chomsky hierarchy, and the minimalist program.

Chomsky also played a pivotal role in the decline of linguistic behaviorism.

He was particularly critical of the work of B. F. Skinner.

Above: US psychologist Burrhaus Frederic Skinner (1904 – 1990)

An outspoken opponent of US involvement in the Vietnam War, which he saw as an act of American imperialism, in 1967 Chomsky rose to national attention for his anti-war essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals“.

Above: A female demonstrator offers a flower to military police on guard at the Pentagon during an anti-Vietnam demonstration. Arlington, Virginia, USA – 20 October 1967

Becoming associated with the New Left, he was arrested multiple times for his activism and placed on President Richard Nixon’s list of political opponents.

Above: US President Richard Nixon (1913 – 1994)

While expanding his work in linguistics over subsequent decades, he also became involved in the linguistics wars.

In collaboration with Edward S. Herman, Chomsky later articulated the propaganda model of media criticism in Manufacturing Consent, and worked to expose the Indonesian occupation of East Timor.

His defense of unconditional freedom of speech, including that of Holocaust denial, generated significant controversy in the Faurisson affair of the 1980s.

Above: US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (1884 – 1962) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Above: Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson (1929 – 2018)

Chomsky’s commentary on the Cambodian genocide and the Bosnian genocide also generated controversy.

Above: Skulls at the Choeung Ek memorial in Cambodia

Above: Memorial stone at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Centre, Bosnia

Since retiring from active teaching at MIT, he has continued his vocal political activism, including opposing the 2003 invasion of Iraq and supporting the Occupy movement.

Above: US Marines with Iraqi POWs – 21 March 2003

An anti-Zionist, Chomsky considers Israel’s treatment of Palestinians to be worse than South African–style apartheid.

He criticizes US support for Israel.

Chomsky is widely recognized as having helped to spark the cognitive revolution in the human sciences, contributing to the development of a new cognitivistic framework for the study of language and the mind.

Chomsky remains a leading critic of US foreign policy, contemporary capitalism, US involvement and Israel’s role in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and mass media.

Above: A Palestinian child sitting on a roadblock at Al-Shuhada Street within the Old City of Hebron in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Palestinians have nicknamed the street “Apartheid Street” because it is closed to Palestinian traffic and open only to Israeli settlers and tourists.

Chomsky and his ideas remain highly influential in the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements.

Since 2017, he has been Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Agnese Nelms Haury Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona.

Chomsky is a prominent political dissident.

His political views have changed little since his childhood, when he was influenced by the emphasis on political activism that was ingrained in Jewish working-class tradition.

He usually identifies as an anarcho-syndicalist or a libertarian socialist.

He views these positions not as precise political theories but as ideals that he thinks best meet human needs:

Liberty, community and freedom of association.

Unlike some other socialists, such as Marxists, Chomsky believes that politics lies outside the remit of science, but he still roots his ideas about an ideal society in empirical data and empirically justified theories.

In Chomsky’s view, the truth about political realities is systematically distorted or suppressed by an elite corporatocracy, which uses corporate media, advertising, and think tanks to promote its own propaganda.

His work seeks to reveal such manipulations and the truth they obscure.

Chomsky believes this web of falsehood can be broken by “common sense“, critical thinking, and understanding the roles of self-interest and self-deception, and that intellectuals abdicate their moral responsibility to tell the truth about the world in fear of losing prestige and funding.

He argues that, as such an intellectual, it is his duty to use his social privilege, resources, and training to aid popular democracy movements in their struggles.

Although he has participated in direct action demonstrations —joining protests, being arrested, organizing groups — Chomsky’s primary political outlet is education, i.e., free public lessons.

Chomsky’s political writings have largely focused on ideology, social and political power, mass media, and state policy.

Above: Noam Chomsky

One of his best-known works, Manufacturing Consent, dissects the media’s role in reinforcing and acquiescing to state policies across the political spectrum while marginalizing contrary perspectives.

Chomsky asserts that this version of censorship, by government-guided “free market” forces, is subtler and harder to undermine than was the equivalent propaganda system in the Soviet Union.

As he argues, the mainstream press is corporate-owned and thus reflects corporate priorities and interests.

Acknowledging that many American journalists are dedicated and well-meaning, he argues that the mass media’s choices of topics and issues, the unquestioned premises on which that coverage rests, and the range of opinions expressed are all constrained to reinforce the state’s ideology.

Although mass media will criticize individual politicians and political parties, it will not undermine the wider state-corporate nexus of which it is a part.

As evidence, he highlights that the US mass media does not employ any socialist journalists or political commentators.

He also points to examples of important news stories that the US mainstream media has ignored because reporting on them would reflect badly upon the country, including the murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton with possible FBI involvement, the massacres in Nicaragua perpetrated by US-funded Contras, and the constant reporting on Israeli deaths without equivalent coverage of the far larger number of Palestinian deaths in that conflict.

Above: American activist Fred Hampton (1948 – 1969)

Above: Flag of Nicaragua

Above: Flag of Israel

Above: Flag of Palestine

To remedy this situation, Chomsky calls for grassroots democratic control and involvement of the media.

Chomsky considers most conspiracy theories fruitless, distracting substitutes for thinking about policy formation in an institutional framework, where individual manipulation is secondary to broader social imperatives.

He separates his Propaganda Model from conspiracy in that he is describing institutions following their natural imperatives rather than collusive forces with secret controls.

Instead of supporting the educational system as an antidote, he believes that most education is counterproductive.

Chomsky describes mass education as a system solely intended to turn farmers from independent producers into unthinking industrial employees.

Noam Chomsky sighed, his fingers tracing unseen patterns on the table.

“And yet, the greatest minds do not emerge from these gilded institutions.

They emerge from the cracks, from the margins, from those who see the lie and refuse to submit.”

Above: Noam Chomsky

The teacher can taste the restlessness of Jonathan Kozol.

Jonathan Kozol is an American writer, progressive activist, and educator, best known for his books on public education in the United States.

Above: Jonathan Kozol

Death at an Early Age, his first non-fiction book, is a description of his first year as a teacher in the Boston Public Schools.

It was published in 1967 and won the National Book Award in Science, Philosophy and Religion.

It has sold more than two million copies in the United States and Europe.

Death at an Early Age: The Destruction of the Hearts and Minds of Negro Children in the Boston Public Schools describes Kozol’s first year of teaching a 4th grade in one of the most overcrowded inner city schools in the Boston public school system.

Kozol recounts the deeply entrenched policies of racial segregation and inequality on the part of Boston Public Schools and testifies to a crumbling infrastructure in his Roxbury, Boston, neighborhood.

The “classroom” he was assigned turned out not to even be a room at all but a corner of an auditorium where other classes were also held.

One day a large window collapsed as he was teaching his class.

The book also documents the public outcry after his dismissal for teaching the Langston Hughes poem “The Ballad of the Landlord” to his reading class, which portrays the exploitation of black tenants by white landlords.

Landlord, landlord,

My roof has sprung a leak.

Don’t you ‘member I told you about it

Way last week?

Landlord, landlord,

These steps is broken down.

When you come up yourself

It’s a wonder you don’t fall down.

Ten bucks you say I owe you?

Ten bucks you say is due?

Well, that’s ten bucks more’n I’l pay you

Till you fix this house up new.

What? You gonna get eviction orders?

You gonna cut off my heat?

You gonna take my furniture and

Throw it in the street?

Um-huh! You talking high and mighty.

Talk on-till you get through.

You ain’t gonna be able to say a word

If I land my fist on you.

Police! Police!

Come and get this man!

He’s trying to ruin the government

And overturn the land!

Copper’s whistle!

Patrol bell!

Arrest.

Precinct Station.

Iron cell.

Headlines in press:

MAN THREATENS LANDLORD

TENANT HELD NO BAIL

JUDGE GIVES NEGRO 90 DAYS IN COUNTY JAIL!

Above: US writer Langston Hughes (1901 – 1967)

The day after presenting the poem to the class an official from the school district informed him that:

“No literature which is not in the course of study can ever be read by a Boston teacher without permission from someone higher up“.

He was fired from his position.

Among the other books by Kozol are Rachel and Her Children: Homeless Families in America, which received the Robert F. Kennedy Book award for 1989 and the Conscience-in-Media Award of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Savage Inequalities: Children in America’s Schools, which won the New England Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1992.

Savage Inequalities: Children in America’s Schools is a book written by Jonathan Kozol in 1991 that discusses the disparities in education between schools of different classes and races.

It is based on his observations of various classrooms in the public school systems of East St. Louis, Chicago, New York City, Camden, Cincinnati, and Washington DC.

Above: East St. Louis, Illinois, USA

Above: Chicago, Illinois, USA

Above: New York City, New York, USA

Above: Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Above: Washington DC

His observations take place in both schools with the lowest per capita spending on students and the highest, ranging from just over $3,000 in Camden, New Jersey to a maximum expenditure of up to $15,000 in Great Neck, Long Island.

Above: Camden, New Jersey, USA

In his visits to these areas, Kozol illustrates the overcrowded, unsanitary and often understaffed environment that is lacking in basic tools and textbooks for teaching.

He cites the large proportions of minorities in the areas with the lowest annual budgets, despite the higher taxation rate on individuals living in poverty within the school district.

Kozol cites various historical cases regarding lawsuits filed against school districts in East Orange, Camden, Irvington and Jersey City in which judges have sided with the children and concerned locals in a given district instead of adhering to state law concerning the taxation and distribution of funding.

Above: City Hall, East Orange, New Jersey, USA

Above: Jersey City, New Jersey, USA

He additionally goes into detail comparing the current conditions poor, minority children are expected to learn in, and the findings of the historical case Brown v. Board of Education and Plessy v. Ferguson.

He also mentions other such historical cases in which the outcomes have supported what he views to be an unjust system of funds distribution and taxation in Milliken v. Bradley, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, and through the overturning of State Supreme Court decisions in both Michigan and Texas by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Kozol argues that racial segregation is still alive and well in the American educational system, due to the gross inequalities that result from unequal distribution of funds collected through both property taxes and funds distributed by the State in an attempt to “equalize” the expenditures of schools.

His 1995 book, Amazing Grace: The Lives of Children and the Conscience of a Nation, described his visits to the South Bronx of New York City, the poorest congressional district in the US.

It received the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1996.

He published Ordinary Resurrections: Children in the Years of Hope in 2000 and The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America was released September 13, 2005.

Kozol documents the continuing and often worsening segregation in public schools in the US and the increasing influence of neoconservative ideology on the way children, particularly children of color and poor children of urban areas, are educated.

Kozol advocates for integrated public education in the US and is a critic of the school voucher movement.

He continues to condemn the inequalities of education and the apparently worsening segregation of black and Hispanic children from white children in the segregated public schools of almost every major city of the nation.

Kozol’s ethical argument relies heavily on comparisons between rich and poor school districts.

In particular, he analyzes the amount of money spent per child.

He finds that in school districts whose taxpayers and property-owners are relatively wealthy, the per-child annual spending is much higher (for example, over $20,000 per year per child in one district) than in school districts where poor people live (for example, $12,000 per year per child in one district).

He asks rhetorically whether it is right that the place of one’s birth should determine the quality of one’s education.

Jonathan Kozol stood, pacing.

“The poor are told that education will free them, yet the very system ensures their servitude.

The wealthy buy their knowledge.

The rest are left with scraps.”

Above: Jonathan Kozol

The teacher quietly waited for William Deresiewicz to speak.

William Deresiewicz is an American author, essayist, and literary critic, who taught English at Yale University from 1998 to 2008.

He is the author of A Jane Austen Education (2011), Excellent Sheep (2014) and The Death of the Artist (2020).

Above: William Deresiewicz

His criticism directed to a popular audience has appeared in The Nation, The American Scholar, The New Republic, The New York Times, The Atlantic and Harper’s.

In A Jane Austen Education, a memoir of a sort, Deresiewicz admits that he was initially resistant to reading 19th-century British fiction.

Soon, though, he discovered that Austen’s novels are valuable tools in the journey towards becoming an adult.

Above: English novelist Jane Austen (1775 – 1817)

Deresiewicz juxtaposes his reading of Jane Austen with insight into his own life.

For example, the reader learns about his controlling father, a series of girlfriends that come and go, and the struggles of being raised in a religious household.

In the summer of 2008, Deresiewicz published a controversial essay for The American Scholar titled “The Disadvantages of an Elite Education“.

In it, he criticizes the Ivy League (an American collegiate athletic conference of eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States) and other elite colleges and universities for supposedly coddling their students and discouraging independent thought.

He claims that elite institutions produce students who are unable to communicate with people who don’t have the same backgrounds as themselves, noting as the first example his own inability to talk to his plumber.

Deresiewicz then uses Al Gore and John Kerry, graduates of Harvard and Yale (respectively), as examples of politicians who are out of touch with the lives of most Americans.

Above: Former US Vice President Al Gore (r. 1993 – 2001)

Above: Former US Secretary of State John Kerry (r. 2013 – 2017)

The article became the groundwork for Deresiewicz’s book Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life (2014).

This work had a mixed response.

Dwight Garner, writing for the New York Times daily book review, praised it as “packed full of what Deresiewicz wants more of in American life:

Passionate weirdness.”

He characterized Deresiewicz as “a vivid writer, a literary critic whose headers tend to land in the back corner of the net“, one whose “indictment arrives on wheels:

He takes aim at just about the entirety of upper-middle-class life in America.”

Other responses, however, were more critical.

In the New York Times Sunday book review, Anthony Grafton conceded that “much of his dystopian description rings true” but argued that:

“The coin has another side, one that Deresiewicz rarely inspects.

Professors and students have agency.

They use the structures they inhabit in creative ways that are not dreamt of in Deresiewicz’s philosophy, and that are more common and more meaningful than the ‘exceptions’ he allows.“

In the New Yorker, Nathan Heller was critical from another corner, arguing that the “quandaries” Deresiewicz describes are “distinctly middle-class“.

Heller says that Deresiewicz argues the liberal arts “will help students hone their ‘moral imagination‘” but:

“The advice seems cheap.

When an impoverished student at Stanford, the first in his family to go to college, opts for a six-figure salary in finance after graduation, a very different but equally compelling kind of ‘moral imagination’ may be at play.

(Imagine being able to pay off your loans and never again having to worry about keeping a roof over your family’s heads.)”

Above: Seal of Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA

Despite this mixed critical response, the book was a New York Times bestseller.

In October 2009, Deresiewicz delivered a speech titled “Solitude and Leadership” to the plebe class at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Above: Coat of arms of West Point Military Academy, New York, USA

It was later published in The American Scholar and went viral online.

In it, he makes the case that leadership entails more than just success and accomplishment.

Above: William Deresiewicz

Citing observations he made of students at Yale and Columbia, Deresiewicz discusses the ubiquity of “world-class hoop jumpers” who “can climb the greasy pole of whatever hierarchy they decide to attach themselves to“.

Above: Logo of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Above: Coat of arms of Columbia University, New York City, USA

Instead, he argues, true leaders (such as General David Petraeus) are those who are able to step outside the cycle of achievement and hoop jumping in order to think for themselves.

Above: Former CIA Director David Petraeus (2011 – 2012)

Deresiewicz claims that solitude is essential to becoming a leader.

William Deresiewicz added:

“And even those who pay find themselves trapped.

They are not thinkers — they are performers in a game rigged against the soul.”

A hush settled, and then, from the shadows, stepped others —figures older, wilder, unafraid.

The teacher waited for Évariste Desiré de Forges, Vicomte de Parny (6 February 1753 – 5 December 1814), French Rococo poet, to speak.

Above: Évariste de Parny

De Parny was born in Saint-Paul on the Isle of Réunion (formerly Île de Bourbon).

Above: Saint Paul, Réunion

He came from an aristocratic family from the region of Berry, which had settled on the island in 1698.

He left the island at the age of ten years to return to France with his two brothers, Jean-Baptiste and Chériseuil.

Above: Location of Réunion

He studied with the Oratoriens at their college in Rennes and decided to enter their religious order.

Above: Place de la Mairie, Rennes, France

According to the historian Prosper Ève:

“A tradition developed by his enemies has it that at the age of 17, he considered embracing an ecclesiastical career with the firm intention of locking himself up in the convent of La Trappe“.

Above: Abbaye of Notre Dame de la Trappe, Soligny la Trappe, France

In fact, he had already “lost a faith that had never been very strong“.

He studied theology for six months at the Collège Saint-Firmin in Paris.

Catriona Seth’s thesis shows that the archives confirm the future writer’s stay at Saint-Firmin.

He officially left because of illness, but it may have been a diplomatic illness.

He decided finally instead on a military career, explaining that he was not religious enough to become a monk.

He was attracted to Christianity mainly by the poetic imagery of the Bible.

Above: College Saint-Firmin, Paris, france

His brother Jean-Baptiste, an equerry of the Count of Artois, introduced him at the French Court at Versailles, where he met two other soldiers, who, like him, were from the French colonies, and would make their names in poetry:

- Antoine de Bertin (1752 – 1790), also from the Isle of Bourbon

Above: French soldier / poet Antoine Bertin

- Nicolas-Germain Léonard (1744 – 1793), from Guadeloupe