Friday 7 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

The blank page is cold before the writer’s touch, a winter’s field before the kindling of thought.

But then — ah, then! — the first spark, the strike of flint against stone, and a small ember glows in the mind’s cavern.

A phrase, a character, a scene — it dances like the first whisper of flame, uncertain yet full of promise.

The night is rich with solitude, contemplation, and the flickering dance between warmth and isolation.

A lone figure, wrapped in layers, sits before a crackling candle in the depths of night.

Shadows stretch long behind me, cast by the flames that are both my refuge and my tether to existence.

The ember glows like a distant star.

The night breathes around me — silent, vast and eternal.

A memory returns, soft as a lover’s whisper.

The night stretched vast and indifferent, a boundless void swallowing the earth in its silent embrace.

Stars, distant and cold, flickered like dying embers in the black expanse above.

But here, on the ground, one fire still burned.

Solitary, I sat before it, my face carved by the shifting glow of the flames.

The fire, my only companion, crackled and whispered, speaking in tongues of heat and hunger.

It was a living thing — dancing, writhing, never still.

It licked at the darkness, casting fleeting shadows that twisted and swayed like restless spirits.

My hands, already rough and weathered by time, reached toward the warmth, as if seeking something beyond mere heat.

The wind howled through the trees, carrying the scent of damp earth and distant rain, but the fire held its ground, defiant against the cold.

I exhaled, watching my breath vanish into the night.

Was it solitude I craved or had the world simply forgotten me?

I could not say.

The fire did not ask.

It did not judge.

It simply burned, as it had since the dawn of time, as it would long after I was gone.

For now, it was enough.

I fed another branch to the flames and watched as it surrendered, consumed in a slow ballet of orange and gold.

The night remained vast.

The fire remained small.

But in its glow, I was not alone.

I am reminded of the past.

The fire has always spoken.

It has whispered in the solitude of cold nights and roared in the chaos of cities consumed.

It has crackled in laughter among friends and burned in quiet resentment where warmth was not welcome.

It has danced in the eyes of poets, priests, and madmen, offering both revelation and ruin.

A solitary man sits before a flame, pen in hand, seeking answers in the flickering light.

The candle trembles with each unseen breath of the room, its glow licking the air, restless.

I wonder — if I lean too close, will the fire burn me?

Will the flame answer or only consume?

My mind drifts, carried by the embers of memory.

I recall the gas stoves of Eskişehir, their blue flames steady beneath my hands.

Fire, here, is tamed — contained within metal and routine.

But still, it holds its mystery.

A candle, a hearth, a wildfire raging through the pages of time — each is fire, yet none are the same.

Is the answer in the flame?

I watch the wax pool, the wick blacken, the dance of light against the ceiling.

Fire is like love, it gives and it takes, destroys and renews, reveals and obscures.

Perhaps as a writer I will never truly grasp it, just as I will never fully capture love, loss or time.

But still, I write.

And still, the fire burns.

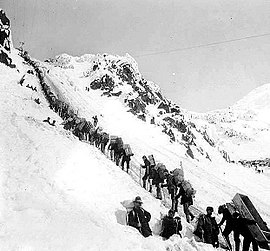

A campfire along the Rideau Canal, where voices lifted into the night, and a poem long committed to heart took on new life in the telling –There are strange things done in the midnight sun….

Above: Rideau Canal, Smiths Falls, Ontario, Canada

The words of Robert W. Service, warmed by firelight, met the eager ears of strangers, and for a moment, I belonged.

Above: British poet Robert W. Service (1874 – 1958)

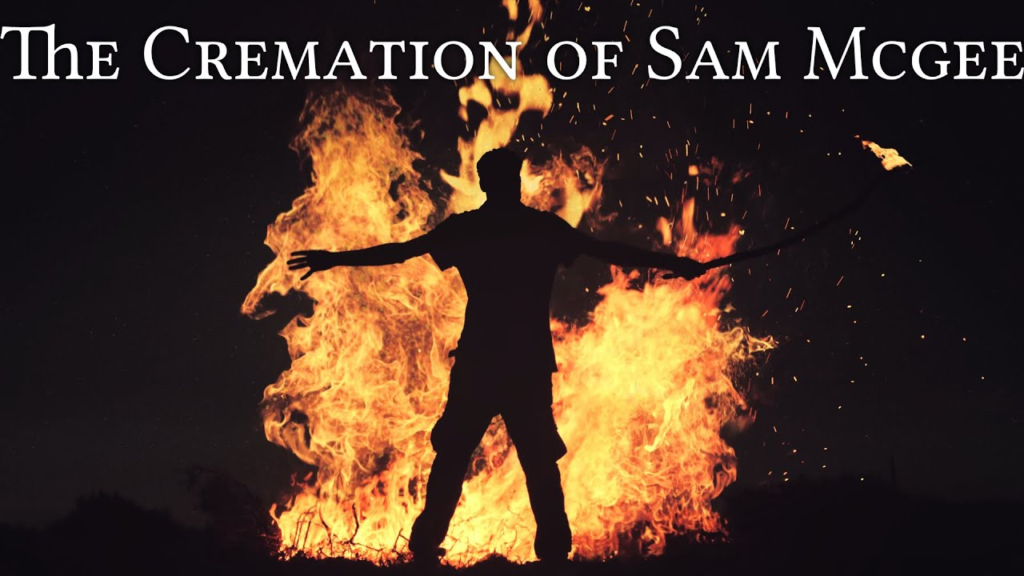

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee, where the cotton blooms and blows.

Why he left his home in the South to roam ’round the Pole, God only knows.

He was always cold, but the land of gold seemed to hold him like a spell;

Though he’d often say in his homely way that “he’d sooner live in Hell“.

Above: Flag of the US state of Tennessee

On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson Trail.

Talk of your cold! Through the parka’s fold it stabbed like a driven nail.

If our eyes we’d close, then the lashes froze till sometimes we couldn’t see;

It wasn’t much fun, but the only one to whimper was Sam McGee.

And that very night, as we lay packed tight in our robes beneath the snow,

And the dogs were fed, and the stars o’erhead were dancing heel and toe,

He turned to me, and “Cap“, says he, “I’ll cash in this trip, I guess;

And if I do, I’m asking that you won’t refuse my last request.“

Well, he seemed so low that I couldn’t say no; then he says with a sort of moan:

“It’s the cursèd cold, and it’s got right hold till I’m chilled clean through to the bone.

Yet ’tain’t being dead — it’s my awful dread of the icy grave that pains;

So I want you to swear that, foul or fair, you’ll cremate my last remains.“

A pal’s last need is a thing to heed, so I swore I would not fail;

And we started on at the streak of dawn; but God! he looked ghastly pale.

He crouched on the sleigh, and he raved all day of his home in Tennessee;

And before nightfall a corpse was all that was left of Sam McGee.

There wasn’t a breath in that land of death, and I hurried, horror-driven,

With a corpse half hid that I couldn’t get rid, because of a promise given;

It was lashed to the sleigh, and it seemed to say: “You may tax your brawn and brains,

But you promised true, and it’s up to you to cremate those last remains.“

Now a promise made is a debt unpaid, and the trail has its own stern code.

In the days to come, though my lips were dumb, in my heart how I cursed that load.

In the long, long night, by the lone firelight, while the huskies, round in a ring,

Howled out their woes to the homeless snows — O God! how I loathed the thing.

And every day that quiet clay seemed to heavy and heavier grow;

And on I went, though the dogs were spent and the grub was getting low;

The trail was bad, and I felt half mad, but I swore I would not give in;

And I’d often sing to the hateful thing, and it hearkened with a grin.

Till I came to the marge of Lake Lebarge, and a derelict there lay;

It was jammed in the ice, but I saw in a trice it was called the “Alice May“.

And I looked at it, and I thought a bit, and I looked at my frozen chum;

Then “Here“, said I, with a sudden cry, “is my cre-ma-tor-eum.“

Some planks I tore from the cabin floor, and I lit the boiler fire;

Some coal I found that was lying around, and I heaped the fuel higher;

The flames just soared, and the furnace roared — such a blaze you seldom see;

And I burrowed a hole in the glowing coal, and I stuffed in Sam McGee.

Then I made a hike, for I didn’t like to hear him sizzle so;

And the heavens scowled, and the huskies howled, and the wind began to blow.

It was icy cold, but the hot sweat rolled down my cheeks, and I don’t know why;

And the greasy smoke in an inky cloak went streaking down the sky.

I do not know how long in the snow I wrestled with grisly fear;

But the stars came out and they danced about ere again I ventured near;

I was sick with dread, but I bravely said: “I’ll just take a peep inside.

I guess he’s cooked, and it’s time I looked“; … then the door I opened wide.

And there sat Sam, looking cool and calm, in the heart of the furnace roar;

And he wore a smile you could see a mile, and he said: “Please close that door.

It’s fine in here, but I greatly fear you’ll let in the cold and storm—

Since I left Plumtree, down in Tennessee, it’s the first time I’ve been warm.“

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

Another fire, in the wilderness beyond Kingman, Arizona — embers shared among those who owned nothing but the night.

They did not ask my name nor where this hitchhiker had been.

They only passed me a place near the flames, an offering of warmth, and passed me a swig from a bottle of whisky, and words of welcome.

Fire had no prejudice there.

Above: Kingman, Arizona, USA

There were other fires:

- the hearth of a summer cottage on Pelee Point, where waves whispered against the shore beyond the glow

Above: Point Pelee National Park, Ontario, Canada

- the crackling heart of the Isis Tavern near Oxford, where history and ale mingled beneath soot-darkened beams

Above: Isis River Farmhouse Tavern, Oxford, England

- the fire built in our own home, hauling wood from the garage to the hearth, only to find the warmth did not reach my soul.

Above: Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

And those who wield words, much like those who wield flames, understand that destruction is sometimes necessary to force change.

The candle before me flickers, its light playing upon the pages of an unfinished thought.

As I write these words, I wonder how wise it would be to light candles inside the apartment, whether the flames would harm the ceiling, whether answers to life lie with the flickering light.

Fire like love is seen but never understood.

A beautiful cascade of memories — each fire a moment, a marker in time, a flickering reminder of where I have been and what I have felt.

Fire, like love, indeed resists understanding, revealing itself only in glimpses:

Warmth and destruction, comfort and danger, invitation and isolation.

Words weave a life shaped by flames — fires of necessity, of fellowship, of history, of longing.

Each blaze tells its own story, whether a humble gas stove in Eskişehir or the great infernos that reshaped cities.

Even now, I ponder the fragile dance of a candle’s glow, its reach upon a ceiling, its whisper of wisdom.

The great fires of history:

Fire would come — an unstoppable force of nature.

The Great Fire of London in 1666, a conflagration that began in a baker’s shop on Pudding Lane, consumed St. Paul’s Cathedral and much of the city.

Above: The Great Fire of London (England), 2 – 6 September 1666

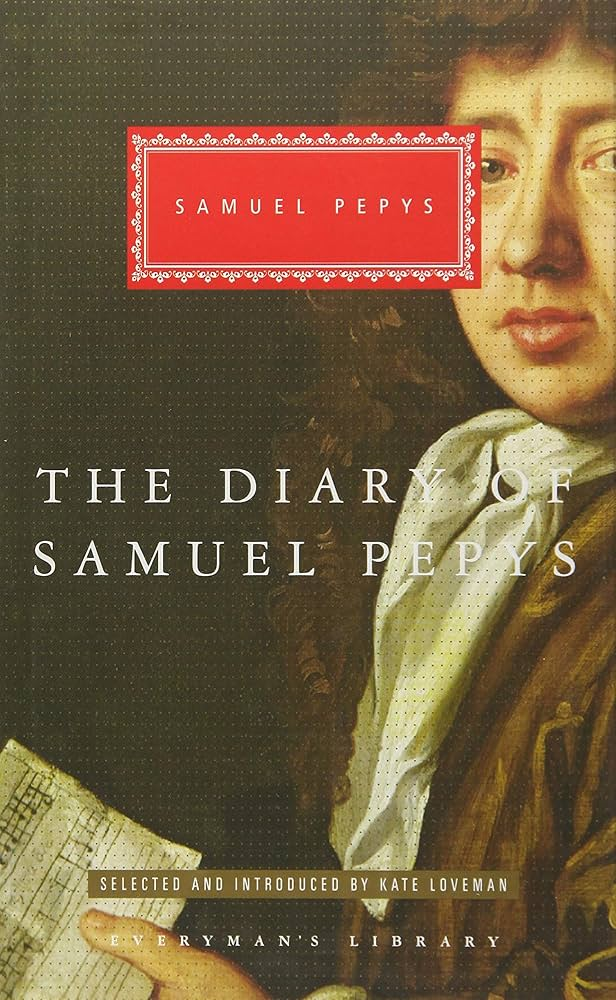

Samuel Pepys described the sight:

“The fire is an unquenched fury, rolling in waves of red upon the houses, melting lead as though it were butter.”

Above: English diarist Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703)

The fire burned so brightly that it turned night into day, and the air shimmered with heat even from a great distance.

Above: The Great Fire of London

The Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, were devoured by flame, their stone bones blackened against the winter sky.

A fire alarm was raised in the Centre Block on 3 February 1916, at 8:37 pm.

Something had been seen smouldering in a wastepaper basket in the Reading Room, but as that was not terribly unusual, a clerk was called to assist.

However, by that point, the fire had progressed beyond control in the wood-panelled and paper-filled room.

The House of Commons was in session that evening and was interrupted by the chief doorkeeper of the Commons calling for evacuation.

Some women in the gallery, unaware of the urgency, attempted to reclaim their fur coats from the coat check and perished.

Others, meanwhile, formed a human chain to carry furniture, files, and artwork out of the burning structure.

The portrait of Queen Victoria in the Commons Chamber was rescued from flames for the second time after the 1849 burning of the Parliament buildings in Montréal.

Half an hour after the fire started came the first of five explosions, and, shortly after midnight, the large bell in the Victoria Tower crashed to the ground.

It had tolled each hour until midnight, when, after ringing eleven times, it ceased to function.

When the fire crews thought that the inferno had been quelled, flames emerged in the Senate Chamber.

Within twelve hours, the building was completely destroyed, except for the Library of Parliament, spared by the closing of its heavy metal doors.

Bowman Brown Law was the only Member of Parliament who died in the fire, bringing the total to seven.

The Cabinet immediately moved to meet at the nearby Château Laurier hotel, while Parliament itself relocated to the Victoria Memorial Museum Building.

With the fire occurring during the First World War, rumours began to circulate a German arsonist had started the blaze, the Toronto Globe asserting that while the official cause of the fire was reported as a carelessly left cigar, “unofficial Ottawa, including many Members of Parliament, declare ‘the Hun hath done this thing.'”

Above: The Parliament Buildings, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada – the morning after the 3 February 1916 fire

The Hull-Ottawa fire of 1900 was a devastating fire in 1900 that destroyed much of Hull, Québec, and large portions of Ottawa, Ontario.

Around 10 AM on 26 April 1900, a defective chimney on a house in Hull caught fire, which quickly spread between the wooden houses due to windy conditions.

Within two hours the blaze had destroyed several surrounding blocks.

At that point it began to spread along the Ottawa River, where there were large lumber companies on the banks and islands, and huge amounts of stacked lumber that quickly ignited.

By 1 PM the fire jumped the River on embers and set the Ottawa side ablaze.

Two thirds of Hull was destroyed, including 40% of its residential buildings and most of its largest employers along the waterfront.

The fire also spread across the Ottawa River, carried by wind borne embers and destroyed a large swath of western Ottawa from the Lebreton Flats south to Dow’s Lake.

About one fifth of Ottawa was destroyed with almost everything in the band between Booth Street and the rail line leveled.

Much of the city’s industry was destroyed, including two major ironworks, two flourmills, and both the Ottawa Electric Railway and Electric Lighting Company.

Parliament was adjourned following the loss of power.

Seven people were killed in the blaze.

Fifteen thousand were made homeless, including 14% of the population of Ottawa and 42% of Hull’s population.

Property losses amounted to $6,200,000 in Ottawa and $3,300,000 in Hull, with insurance covering 50% of the damage in Ottawa but only 23% of the damage in Hull.

More were killed by disease in the densely packed tent cities where the people were forced to live afterwards.

Worldwide response to the disaster generated $957,000 in aid.

Above: The Ottawa – Hull fire, 26 April 1900

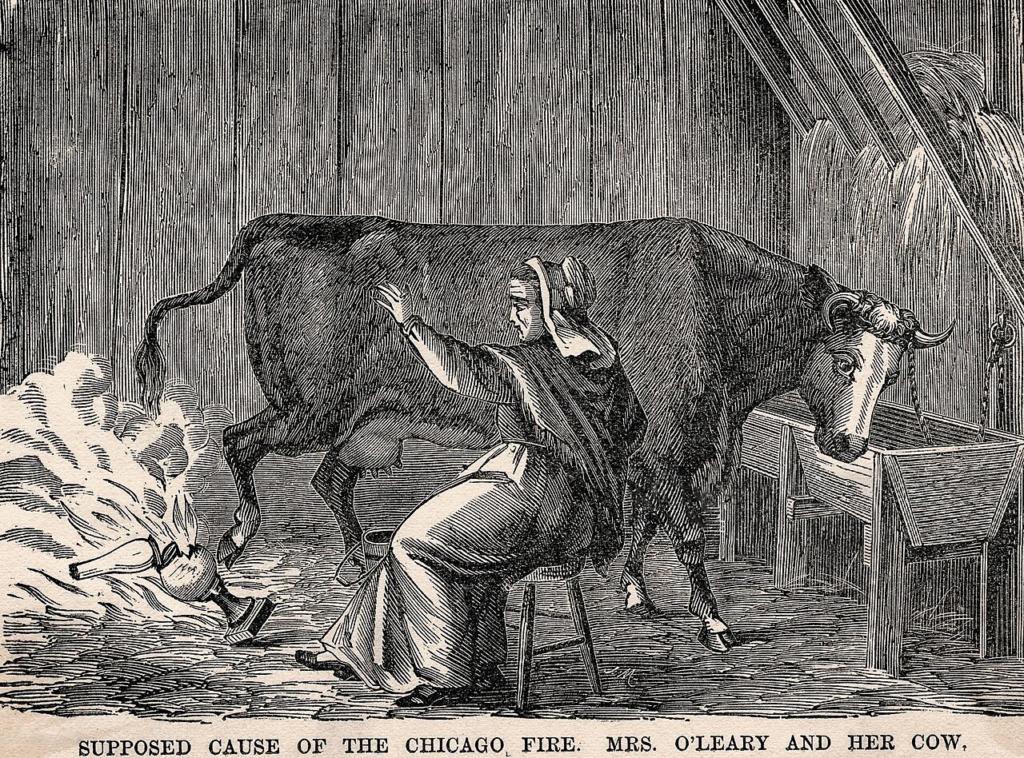

The Great Fire of Chicago, where legend placed the blame on a cow but history knew better — fire cares little for scapegoats.

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871.

The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly 3.3 square miles (9 km2) of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 100,000 residents homeless.

The fire began in a neighborhood southwest of the city center.

A long period of hot, dry, windy conditions, and the wooden construction prevalent in the city, led to the conflagration spreading quickly.

The fire leapt the south branch of the Chicago River and destroyed much of central Chicago and then crossed the main stem of the river, consuming the Near North Side.

Help flowed to the city from near and far after the fire.

The city government improved building codes to stop the rapid spread of future fires and rebuilt rapidly to those higher standards.

A donation from the United Kingdom spurred the establishment of the Chicago Public Library.

Above: The Great Chicago Fire, 8 – 10 October 1871

Almost from the moment the fire broke out, various theories about its cause began to circulate.

The most popular and enduring legend maintains that the fire began in the O’Leary barn as Mrs. O’Leary was milking her cow.

The cow kicked over a lantern (or an oil lamp in some versions), setting fire to the barn.

The O’Leary family denied this, stating that they were in bed before the fire started, but stories of the cow began to spread across the city.

Catherine O’Leary seemed the perfect scapegoat:

She was a poor, Irish Catholic immigrant.

During the latter half of the 19th century, anti-Irish sentiment was strong in Chicago and throughout the United States.

This was intensified as a result of the growing political power of the city’s Irish population.

Furthermore, the United States had been distrustful of Catholics (or papists, as they were often called) since its beginning, carrying over attitudes in England in the 17th century.

As an Irish Catholic, Mrs. O’Leary was a target of both anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiment.

This story was circulating in Chicago even before the flames had died out, and it was noted in the Chicago Tribune‘s first post-fire issue. In 1893 the reporter Michael Ahern retracted the “cow-and-lantern” story, admitting it was fabricated, but even his confession was unable to put the legend to rest.

Although the O’Learys were never officially charged with starting the fire, the story became so engrained in local lore that Chicago’s city council officially exonerated them — and the cow — in 1997.

Amateur historian Richard Bales has suggested the fire started when Daniel “Pegleg” Sullivan, who first reported the fire, ignited hay in the barn while trying to steal milk.

Part of Bales’ evidence includes an account by Sullivan, who claimed in an inquiry before the Fire Department of Chicago on November 25, 1871, that he saw the fire coming through the side of the barn and ran across DeKoven Street to free the animals from the barn, one of which included a cow owned by Sullivan’s mother. Bales’s account does not have consensus.

The Chicago Public Library staff criticized his account in their web page on the fire.

Despite this, the Chicago city council was convinced of Bales’s argument and stated that the actions of Sullivan on that day should be scrutinized after the O’Leary family was exonerated in 1997.

Anthony DeBartolo reported evidence in two articles of the Chicago Tribune (October 8, 1997, and March 3, 1998, reprinted in Hyde Park Media) suggesting that Louis M. Cohn may have started the fire during a craps game.

Following his death in 1942, Cohn bequeathed $35,000 which was assigned by his executors to the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

The bequest was given to the school on September 28, 1944.

The dedication contained a claim by Cohn to have been present at the start of the fire.

Above: Seal of Northwestern University

According to Cohn, on the night of the fire, he was gambling in the O’Learys’ barn with one of their sons and some other neighborhood boys.

When Mrs. O’Leary came out to the barn to chase the gamblers away at around 9:00, they knocked over a lantern in their flight, although Cohn states that he paused long enough to scoop up the money.

The argument is not universally accepted.

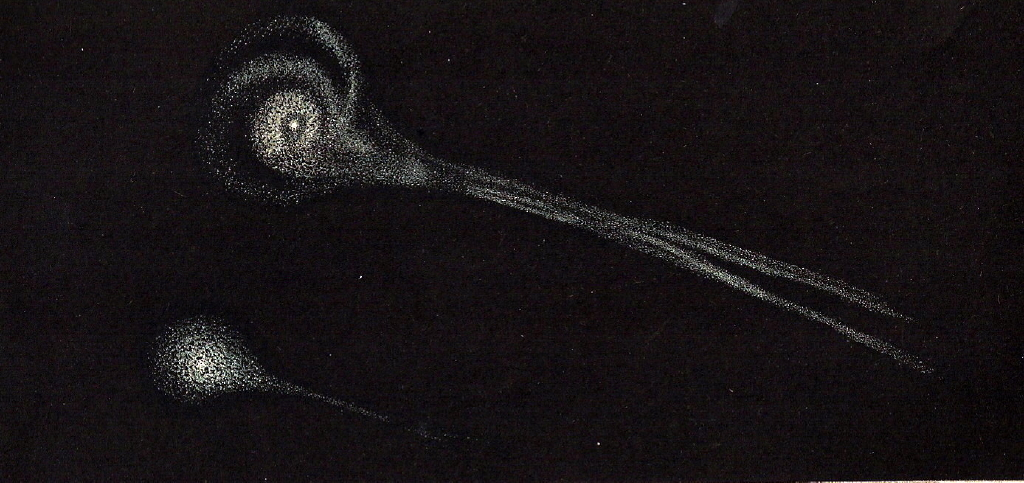

An alternative theory, first suggested in 1882 by Ignatius L. Donnelly in Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, is that the fire was caused by a meteor shower.

This was described as a “fringe theory” concerning Biela’s Comet.

Above: Ignatius Donnelly (1831 – 1901)

At a 2004 conference of the Aerospace Corporation and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, engineer and physicist Robert Wood suggested that the fire began when a fragment of Biela’s Comet impacted the Midwest.

Biela’s Comet had broken apart in 1845 and had not been observed since.

Above: Biela’s Comet

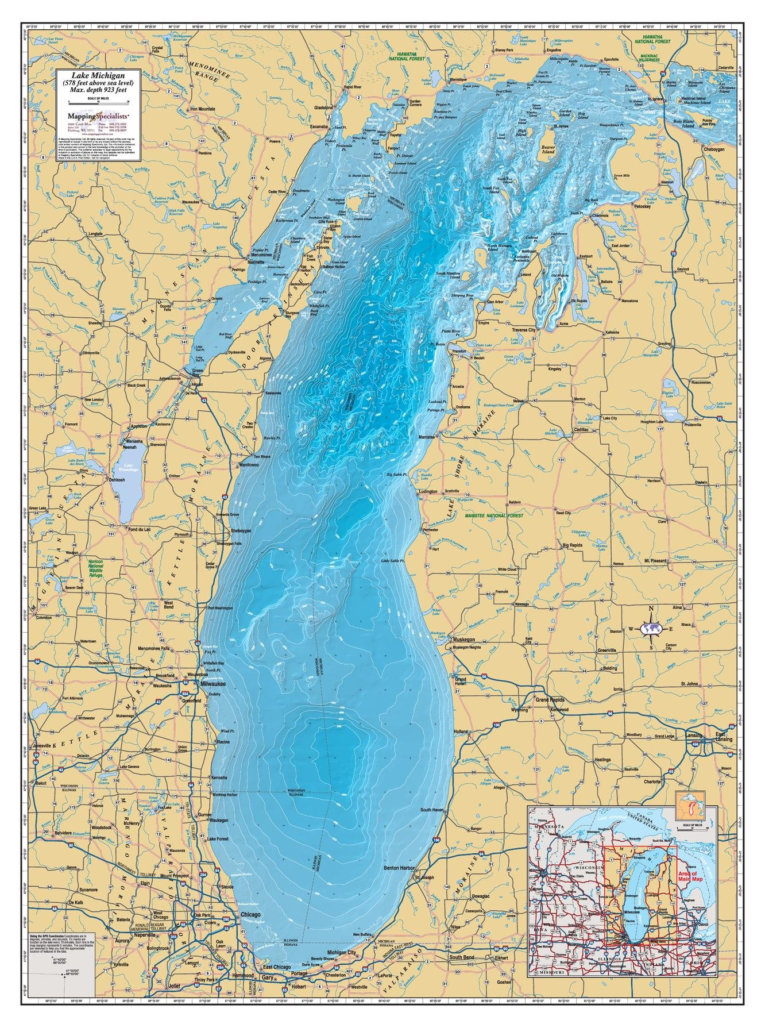

Wood argued that four large fires took place, all on the same day, all on the shores of Lake Michigan, suggesting a common root cause.

Eyewitnesses reported sighting spontaneous ignitions, lack of smoke, “balls of fire” falling from the sky, and blue flames.

According to Wood, these accounts suggest that the fires were caused by the methane that is commonly found in comets.

Meteorites are not known to start or spread fires and are cool to the touch after reaching the ground, so this theory has not found favor in the scientific community.

Methane-air mixtures become flammable only when the methane concentration exceeds 5%, at which point the mixtures also become explosive, a situation unlikely to occur from meteorites.

Methane gas is lighter than air and thus does not accumulate near the ground.

Any localized pockets of methane in the open air rapidly dissipate.

Moreover, if a fragment of an icy comet were to strike the Earth, the most likely outcome, due to the low tensile strength of such bodies, would be for it to disintegrate in the upper atmosphere, leading to a meteor air burst like the Tunguska event.

The specific choice of Biela’s Comet does not match with the dates in question, as the six-year period of the comet’s orbit did not intersect that of the Earth until 1872, one full year after the fire, when a large meteor shower was observed.

A common cause for the fires in the Midwest in late 1871 is that the area had had a dry summer, so that winds from the front that moved in that evening were capable of generating rapidly expanding blazes from available ignition sources, which were plentiful in the region.

Above: Aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire

The flames that swallowed Baltimore, twisting steel and brick into ruin, a city remade in the crucible of disaster.

In Baltimore, on 7 February 1904, flames consumed the heart of a great city.

The Great Fire of Baltimore devoured manuscripts and libraries, but in its wake, new books were written, new voices found their strength.

On a freezing February morning in 1904, the city of Baltimore awoke to an inferno.

The Great Fire consumed more than a thousand buildings, a blaze that spread faster than men could contain it.

The air filled with the scent of burning paper — ledgers, books, letters — whole lives recorded and lost in embers.

And yet, from destruction, a city was reborn, rising phoenix-like from its own smoldering ruins.

The city of Baltimore burned, its wooden structures and faulty fire-suppression systems fueling an inferno that consumed over 1,500 buildings in two days.

The fire that consumed Baltimore was described in contemporary reports as an “inferno beyond control“, with flames leaping from building to building, embers swirling like fireflies in the choking smoke.

The heat was so intense that metal streetcar rails twisted like soft vines, and brick structures crumbled as though struck by cannon fire.

Journalists wrote of “a city trapped in a storm of flame“, where even the air seemed to ignite, suffocating those who dared to linger.

The fire moved with a monstrous hunger, devouring 1,500 buildings before its embers finally died.

A city that had flourished in the embers of the Industrial Revolution found itself reduced to ruin, its skyline reshaped by flames.

And yet, as with all great fires, destruction was not the end of the story.

Baltimore rebuilt itself, stronger and more modern.

In the ashes of the past, a new city was born.

The Great Fire of Baltimore would tell another story — a city engulfed, businesses reduced to charred skeletons, iron bending under the heat’s insistence.

Newspapers recorded the sound of timbers collapsing as a roar, a groan, an almost human wail of protest against destruction.

And yet, from the smoldering ruin, Baltimore rose again — proving that fire may consume, but it also clears the ground for new beginnings.

Fire is not merely an end — it is often a beginning.

Above: Aftermath of the Great Baltimore Fire (7 – 8 February 1904)

Fire has always been both destroyer and creator — reducing the past to ash while lighting the way for something new.

The great fires of history destroyed much, but from their ashes, new worlds emerged.

The great fires of history destroyed much, but from their ashes, new worlds emerged.

The Bonfire of the Vanities sought to silence art, yet the very act of destruction reminds us of its power.

What is creativity but the defiance of oblivion?

The artist’s fire is not easily extinguished — it flickers in hidden corners, waiting to reignite.

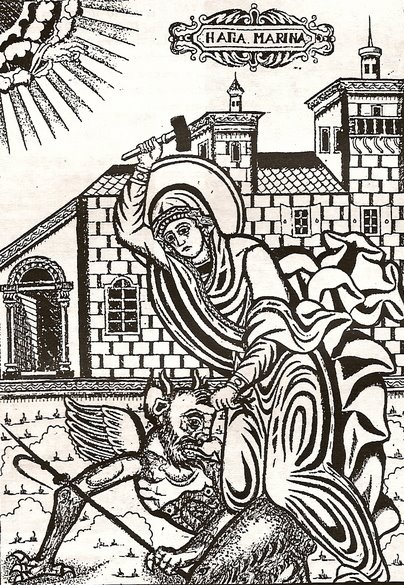

Above: Bernardino of Siena (1380 – 1444) organising the vanities bonfire

On the winter’s evening of 7 February 1497 in Florence, fire roared at the heart of the Piazza della Signoria.

A Dominican friar named Girolamo Savonarola had called for the Bonfire of the Vanities, demanding the faithful sacrifice their mirrors, their fine clothes, their manuscripts and paintings — all that was sinful, all that was beautiful.

And so, the flames licked at poetry and paintings alike, devouring the very art that once made the city glorious.

Fra Girolamo Savonarola’s infamous bonfire in Firenze (Florence) was not merely a fire of destruction but of purification — at least in his eyes.

Above: Italian preacher Girolamo Savonarola (1452 – 1498)

Eyewitness accounts describe the flames rising high in the Piazza della Signoria, fed by heaps of vanities:

Mirrors, cosmetics, books, musical instruments, and paintings.

The fire crackled and roared, its heat searing the faces of those who stood too close, its smoke curling into the sky as if the city itself exhaled a final breath of decadence.

It was not just a burning — it was a spectacle, a performance of moral cleansing through destruction.

The Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497 was not merely a fire of objects —it was the incineration of ideas, a purge of the Renaissance spirit.

The flames flickered against the frescoed walls of Florence, consuming books that once held wisdom, paintings that once captured beauty, and instruments that once played joy into the streets.

The fire was not just heat and light — it was a declaration, a warning, a torch held against the dawn of free thought.

But fire, like thought, does not die easily.

The very act of burning ideas ensures their survival in memory.

Above: The Bonfire of the Vanities, Firenze, Italia, 7 February 1497

Fire has long been a powerful symbol in the great faiths, evoking both destruction and renewal, punishment and enlightenment, warmth and divine presence.

The great faiths have long spoken of fire.

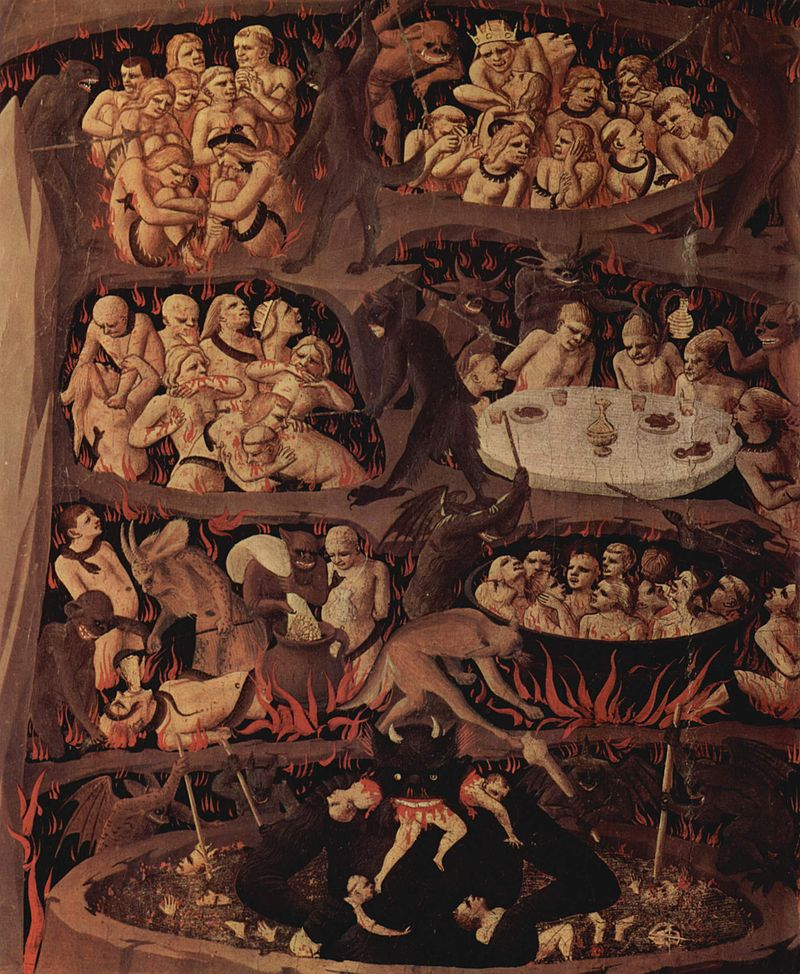

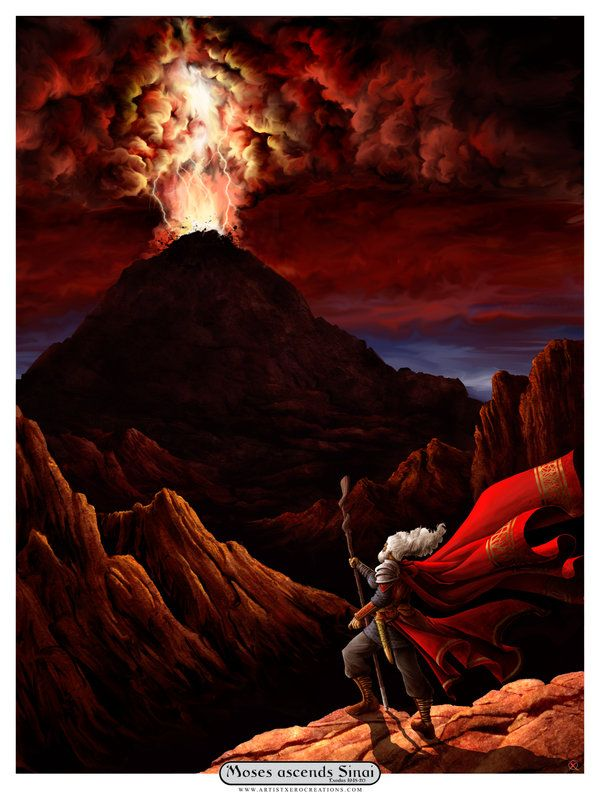

Fire is both punishment and purification, the flames of Hell and the burning bush of divine revelation.

Above: The Last Judgment, Fra Angelico (1431), depicting people being tormented in Hell

Above: The Burning Bush, Sébastien Bourdon (1650)

The congregation is logs upon a fire — when together, they burn brightly, but when separated, they smolder and die.

The Zoroastrians keep fire as a sacred presence, a symbol of truth.

Above: Zoroastrian Fire Temple, Yazd, Iran

The Greeks gave us Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods, gifting it to man — not just as warmth, but as knowledge, as defiance, as the first true revolution.

Above: Prometheus Brings Fire, Heinrich Füger (1817)

Let us journey through the sacred texts and traditions to see how fire has been used to illuminate the path of faith.

Christianity: Fire as Purification and Presence

“As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.“ (Proverbs 27:17)

Just as a lone log smolder out, so too does a believer grow cold without the warmth of community.

Fire in the Bible often represents divine presence and transformation:

- Moses and the Burning Bush:

“There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush.

Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up.“

(Exodus 3:2-4)

Here, fire is the medium through which God speaks — alive but not consuming, a paradox of power and peace.

- Pentecost: The Tongues of Fire

“They saw what seemed to be tongues of fire that separated and came to rest on each of them.

All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues.“

(Acts 2:3-4)

Fire here is enlightenment and divine inspiration, igniting the voices of the faithful.

- Purgatory and Refining Fire

“Each one’s work will become clear, for the Day it will declare it, because it will be revealed by fire, and the fire will test each one’s work, of what sort it is.“

(1 Corinthians 3:13-15)

Fire purges impurities, refining the soul, much as metal is purified in a forge.

Judaism: Fire as Covenant and Sacrifice

- The Pillar of Fire

“By day the Lord went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night.“

(Exodus 13:21)

Here, fire is guidance, the lamp of divine direction.

- The Eternal Flame (Ner Tamid)

In Jewish synagogues, a lamp is kept burning continuously, symbolizing God’s eternal presence.

This tradition comes from the command in Leviticus 6:13:

“The fire must be kept burning on the altar continuously; it must not go out.“

- The Fire on Mount Sinai

“Mount Sinai was covered with smoke, because the Lord descended on it in fire.“

(Exodus 19:18)

A moment of awe and terror — fire is the intensity of divine law and the unapproachable holiness of God.

Islam: Fire as a Test and a Punishment

- Hellfire (Jahannam)

Fire in Islam often represents divine justice:

“Indeed, those who disbelieve in Our verses —

We will drive them into a Fire.

Every time their skins are roasted through,

We will replace them with other skins so they may taste the punishment.“

(Qur’an 4:56)

- The Trial of Abraham

“We said, ‘O fire, be coolness and safety upon Abraham.’”

(Qur’an 21:69)

When Abraham was cast into the fire by his enemies, God turned the flames into peace, showing divine intervention can alter even the nature of fire itself.

Hinduism: Fire as Transformation and Witness

- Agni, the Fire God

Agni, the Hindu god of fire, is the messenger between gods and humans, carrying sacrificial offerings to the divine. Fire here is the bridge between mortal and immortal.

- The Sacred Fire in Weddings

Hindu marriage ceremonies take place around a sacred fire (Agni), which serves as a divine witness to the vows.

- The Bhagavad Gita: Fire as Knowledge

Krishna says:

“As a blazing fire reduces wood to ashes, so too does the fire of knowledge burn to ashes all karma.“

(Bhagavad Gita 4:37)

Fire is wisdom — it consumes ignorance and purifies the soul.

Above: Bhagavad Gita’s revelation: Krishna tells the Gita to Arjuna

Buddhism: Fire as Attachment and Suffering

- The Fire Sermon

The Buddha famously taught about the fires of desire, hatred, and delusion:

“The world is burning.

It is burning with the fire of greed, with the fire of hatred, with the fire of delusion.“

The goal of enlightenment is to extinguish these fires — hence the term nirvana, meaning “blown out” like a candle.

Across traditions, fire is both destruction and illumination, punishment and purification, wrath and warmth.

It is God’s presence and man’s trial.

It is a test, a guide and an eternal reminder of forces greater than us.

And those who wield words, much like those who wield flames, understand that destruction is sometimes necessary to force change.

On 7 February 1612, a child was born into a world of fire and spectacle.

Above: English dramatist Thomas Killigrew (1612 – 1683)

Thomas Killigrew (7 February 1612 – 19 March 1683) was an English dramatist and theatre manager.

He was a witty, dissolute figure at the court of King Charles II of England.

Thomas Killigrew, a playwright who would one day revel in wit and scandal, grew up to see fire not as a force of destruction but as a stage upon which life played its grandest performances.

His Restoration-era dramas flickered with the same light as a candlelit theater — an ephemeral glow, gone too soon, yet seared into memory.

Fire is not always contained within a script.

Thomas Killigrew reignited English theater after Puritan rule sought to snuff it out.

Killigrew’s comedies were embers of a world rekindled after puritanical darkness.

Theater, too, has burned — sometimes literally, as many of London’s great playhouses fell to flames, and sometimes metaphorically, when Puritan rule sought to extinguish the stage.

When Thomas Killigrew was born, the English theater stood on the brink of darkness.

The Puritans, seeing performance as sinful, closed playhouses and silenced actors.

But fires never truly die.

They smolder beneath the surface, waiting for the right breath of air.

When the monarchy was restored, so too was theater, and Killigrew— appointed to oversee the revival — lit the match.

He brought Shakespeare and new works back to life, proving that the power of storytelling could not be suppressed.

Killigrew was one of twelve children of Sir Robert Killigrew of Hanworth (1580 – 1633)(a courtier to James I) and his wife Mary née Woodhouse.

Above: English King James I (1566 – 1625)

Thomas became a page to King Charles I at about the age of thirteen.

Above: English King Charles I (1600 – 1649)

According to Samuel Pepys, the boy Killigrew used to volunteer as an extra, or “devil,” at the Red Bull Theatre (1604 – 1642), so that he could see the plays for free.

The young Killigrew had limited formal education.

The Court and the playhouse were his schoolroom.

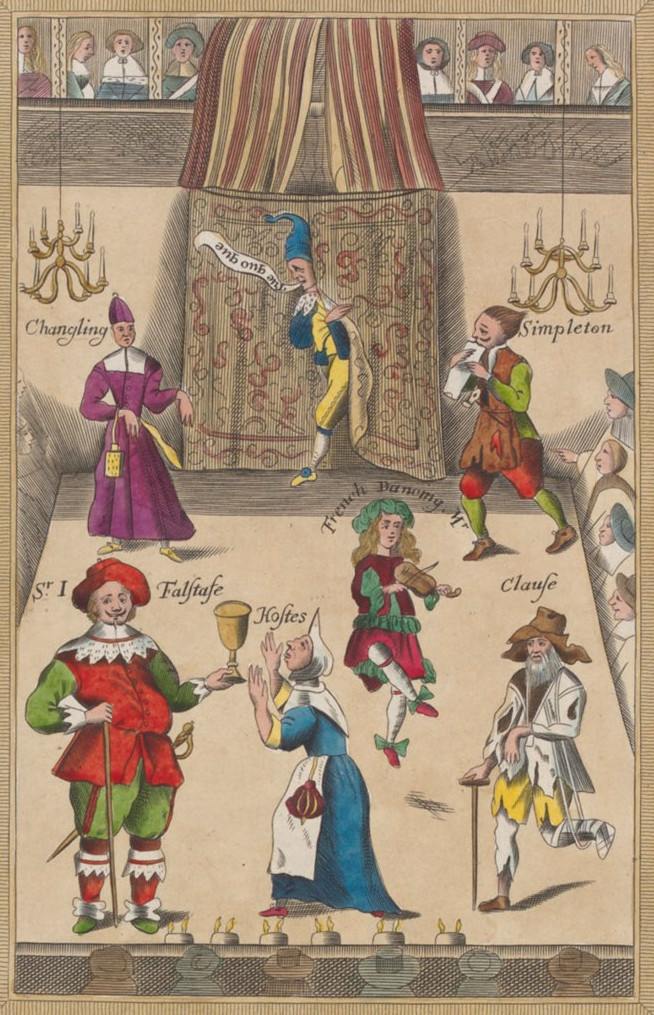

Above: A performance at the Red Bull

Killigrew was present at the exorcism of the possessed nuns of Loudun.

In 1635 he left a sceptical account of the proceedings.

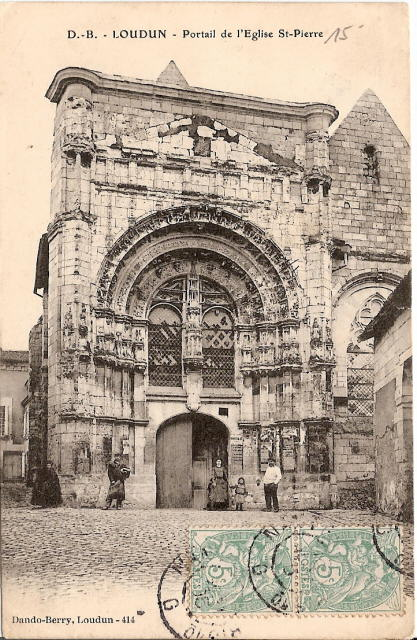

The Loudun possessions, also known as the Loudun possessed affair (French: Affaire des possédées de Loudun), was a notorious witchcraft trial that took place in Loudun, Kingdom of France, in 1634.

Above: Porte Martray, Loudon, France

In its continuing efforts to consolidate and centralize power, the Crown under Louis XIII ordered the walls around Loudun, a town in Poitou, France, to be demolished.

The populace were of two minds concerning this.

The Huguenots (Protestants), for the most part, wanted to keep the walls, while the Catholics supported the monarchy.

Above: French King Louis XIII (1601 – 1643)

In May 1632, an outbreak of the plague in Loudun claimed many lives.

Together, the events contributed to an atmosphere of anxiety and apprehension in the divided town.

Above: St. Peter Church, Loudon, Poitou, France

Urbain Grandier was born at Rouvère towards the end of the sixteenth century.

In 1617 he was appointed parish priest of St-Pierre-du-Marché in Loudun and a canon at the Church of Sainte-Croix.

Above: Holy Cross Abbey, Poitiers, France

Grandier was considered to be a good-looking man, wealthy and well-educated.

An eloquent and popular preacher, he incurred the envy of some of the local monks.

As he did not support Cardinal Richelieu’s policies, he was in favor of retaining the town’s wall.

Above: French Cardinal Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (1585 – 1642)

It was widely believed that Grandier had fathered a son by Philippa Trincant, the daughter of his friend, Louis Trincant, the King’s prosecutor in Loudun.

According to Monsieur des Niau, Counsellor at la Flèche, Grandier had aroused the hostility of a number of husbands and fathers, some quite influential, by the dishonor he had brought to their families through relations with the female members of their households.

(However, Niau’s views may be understood as those of a participant in the subsequent proceedings who fully endorsed them.)

Around 1629, Jacques de Thibault, possibly a relative of Philippa, was quite vocal in expressing his opinion of Grandier’s conduct with women.

When Grandier demanded an explanation, Thibault beat him with a cane outside the Church of Sainte-Croix.

In the course of the resulting trial, Thibault raised certain charges in his defense, causing the magistrates to turn Grandier over to the ecclesiastical court.

The Bishop then prohibited Grandier from performing any public functions as priest for five years in the Diocese of Poitiers, and forever in Loudun.

Grandier appealed to the court at Poitiers.

As a number of witnesses retracted their statements, the case was dismissed without prejudice should new evidence be presented.

Above: Cathédrale Saint-Pierre, Poitiers, France

A convent of Ursuline nuns said they had been visited and possessed by demons.

The Ursuline convent had been opened in Loudun in 1626.

In 1632 prioress Jeanne des Anges presided over seventeen nuns, whose average age was twenty-five.

Above: Ursuline Sister Marie Ieanne des Anges (1602 – 1665)

The first reports of alleged demonic possession began about five months after the outbreak of plague in 1632, as it was winding down.

While physicians and wealthy property owners had left town, (the physicians because there was nothing they could do), others attempted to isolate themselves.

The convents had shut themselves behind walls, the nuns discontinued receiving parlor visitors.

Grandier visited the sick and gave money to the poor.

A young nun said that she had had a vision of her recently deceased confessor, Father Moussant.

Soon other nuns reported similar visions.

Canon Jean Mignon, the convent chaplain who was also a nephew of Trincant, decided that a series of exorcisms was in order.

In the town, the people were saying it was an “imposture“.

The nuns claimed the demon Asmodai was sent to commit evil and impudent acts with them.

Above: Figure of Asmodai, Rennes, France

During questioning about the supposed evil spirit thought to be possessing them, the nuns gave several answers as to who caused its presence:

A priest, Peter, and Zabulon.

It was after almost a week, on 11 October, that Grandier was named as the magician responsible, though none of them had ever met him.

Next, people who were asserted to be physicians and apothecaries were brought in.

Canon Mignon informed the local magistrates of what was happening at the convent.

Grandier filed a petition stating that his reputation was under attack and that the nuns should be confined.

The Archbishop of Bordeaux intervened and ordered the nuns sequestered, upon which the appearances of possession seemed to subside for a time.

Above: Cathédrale Saint-André, Bordeaux, France

The nuns’ increasingly extreme behavior – shouting, swearing, barking, etc. – drew a considerable number of spectators.

Eventually, Cardinal Richelieu decided to intervene.

Grandier had already offended Richelieu by his public opposition to the demolition of the town walls, and his reputation for illicit relations with parishioners did not improve his standing with the Cardinal.

In addition, Grandier had written a book attacking the discipline of clerical celibacy as well as a scathing satire of the Cardinal.

Around the time of the nuns’ accusations, Jean de Laubardemont was sent to demolish the town tower.

He was prevented from doing so by the town militia, and upon returning to Paris reported on the state of affairs in Loudun including the recent disturbance at the Ursuline convent.

In November 1633, de Laubardemont was commissioned to investigate the matter.

Grandier was arrested as a precaution against his fleeing the area.

The Commissioner then began to take statements from witnesses who said Grandier often mysteriously appeared at the convent at all hours, although no one knew how he was able to get inside.

The priest was further accused of all manner of indecency.

Laubardemont then questioned Grandier as to the facts and articles of accusation, and after having made him sign his statement and denials, proceeded to Paris to inform the Court.

Letters from the Bailly of Loudun, Grandier’s chief supporter, to the Procurator-General of the Parlement, in which it was asserted that the possessions were an imposture, were intercepted.

The latter’s reply was also seized.

Grandier, who had been held at the prison of Angers, was returned to Loudun.

Above: Images of Angers, France

Laubardemont once again observed and interrogated the nuns, now dispersed among a number of convents.

The Bishop of Poitiers, after having sent several Doctors of Theology to examine the victims, came to Loudun in person, and over the next two and half months, he performed exorcisms, as did Father Tranquille.

On 23 June 1634, the Bishop of Poitiers and M. de Laubardemont being present, Grandier was brought from his prison to the Church of St. Croix in his parish, to be present at the exorcisms.

All the possessed were there likewise.

As the accused and his partisans declared that the possessions were mere impostures, he was ordered to be himself the exorcist, and the stole was presented to him.

He could not refuse, and therefore, taking the stole and the ritual, he received the pastoral benediction, and after the Veni Creator had been sung, commenced the exorcism in the usual form.

In August 1634, the case was heard before the local magistrates.

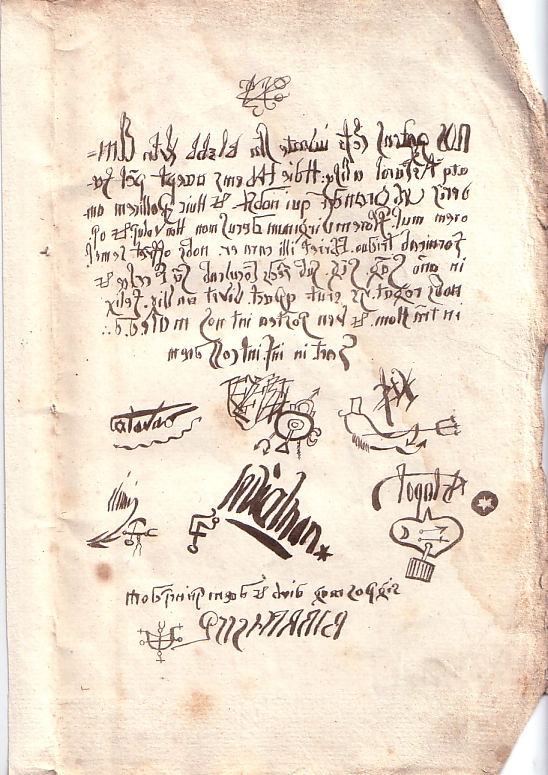

It was alleged that Grandier had made a pact with the Devil, and had invited someone to a witches’ sabbath.

Above: Urbain Grandier’s alleged diabolical pact

Grandier was found guilty of sorcery and placing evil spells to cause the possession of the Ursuline nuns.

He was condemned to be burned at the stake.

Grandier was taken to the Court of Justice of Loudun.

His sentence having been read to him, he earnestly begged M. de Laubardemont and the other Commissioners to mitigate the rigour of their sentence.

M. de Laubardemont replied that the only means of inducing the judges to moderate the penalties was to declare at once his accomplices.

The only answer he gave was that he had no accomplices.

Above: French Catholic priest Urbain Grandier (1590 – 1634)

Father Grandier was promised that he could have the chance to speak before he was executed, making a last statement, and that he would be hanged before the burning, an act of mercy.

From the scaffold Grandier attempted to address the crowd, but the monks threw large quantities of holy water in his face so that his last words could not be heard.

Then, according to historian Robert Rapley, exorcist Lactance caused the execution to deviate from the planned course of action —enraged by taunting from the crowd that gathered for the execution, Lactance lit the funeral pyre before Grandier could be hanged, leaving him to be burned alive.

The executioner then advanced, as is always done, to strangle him, but the flames suddenly sprang up with such violence that the rope caught fire.

Grandier fell alive among the burning wood.

In 1679, the English philosopher John Locke concluded:

“The story of the nuns of Loudun possessed, was nothing but a contrivance of Cardinal Richelieu to destroy Grandier, a man he suspected to have wrote a book against him, who was condemned for witchcraft in the case, and burnt for it.

The scene was managed by the Capuchins, and the nuns played their tricks well, but all was a cheat.“

Above: English philosopher John Locke (1632 – 1704)

Agénor de Gasparin suggests that the early so-called “demonic manifestations” were actually pranks played by some of the boarding students in an effort to frighten some of the nuns, and as the matters progressed, it was the chaplain Jean Mignon who introduced Grandier’s name to the suggestible nuns.

Above: French statesman/author Agénor de Gasparin (1810 – 1871)

Michel de Certeau attributes the symptoms of the nuns as due to some psychological disorder such as hysteria, and views the events in context of the shifting intellectual climate of 17th century France.

Possession allowed the nuns to express their ideas, concerns, and fears through the voice of another.

The events at Loudun played out over a number of years, and attracted a good deal of attention throughout France.

In this sense it was a sort of political-theatre.

Grandier serves as a scapegoat to deflect the Louduns’ ambivalence regarding the central Parisian authority.

Above: Flag of France

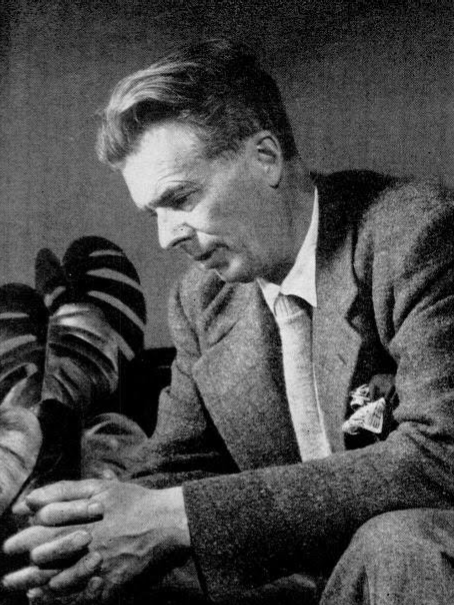

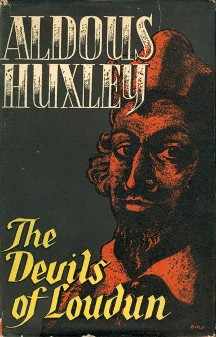

Aldous Huxley, in his non-fiction book, The Devils of Loudun, argued that the accusations began after Grandier refused to become the spiritual director of the convent, unaware that the Mother Superior, Sister Jeanne of the Angels, had become obsessed with him, having seen him from afar and heard of his sexual exploits.

Above: English writer/philosopher Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963)

According to Huxley, Sister Jeanne, enraged by his rejection, instead invited Canon Jean Mignon, an enemy of Grandier, to become the director.

Jeanne then accused Grandier of using black magic to seduce her.

The other nuns gradually began to make similar accusations.

However, Monsieur des Niau, Counsellor at la Flèche, said that Grandier applied for the position, but that it was instead awarded to Canon Jean Mignon, a nephew of Monsieur Trincant.

Before the English Civil War (1642 – 1651), Killigrew wrote several plays — tragicomedies like Claracilla and The Prisoners, as well as his most popular play, The Parson’s Wedding (1637).

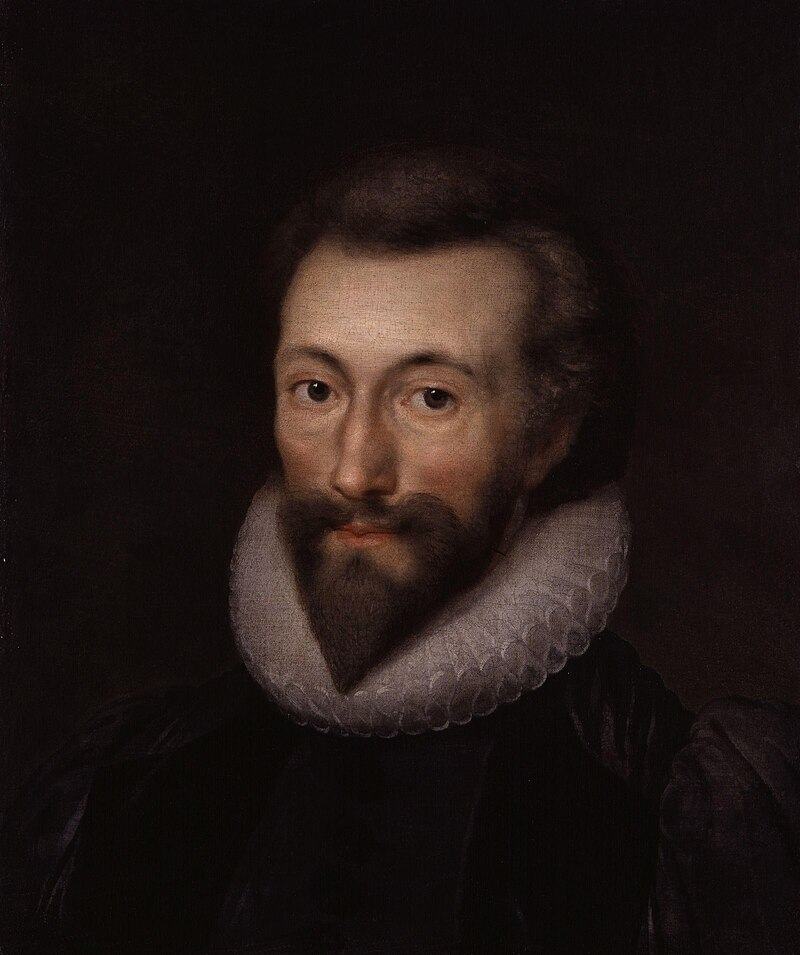

The latter play has been criticized for its coarse humour, but it also contains prose readings of John Donne’s poetry to pique a literate audience.

Above: English poet John Donne (1571 – 1631)

A Royalist and Roman Catholic, Killigrew followed Prince Charles (the future Charles II) into exile in 1647.

Above: English King Charles II (1630 – 1685)

In the years 1649 – 1651, he was in Paris, Geneva and Rome.

Above: Paris, France

Above: Genève (Geneva), Suisse (Switzerland)

Above: Roma (Rome), Italia (Italy)

In 1651, Killigrew was appointed Charles’ representative in Venice.

Above: Venezia (Venice), Italia (Italy)

(It has been said that Killigrew wrote each of his plays in a different city.

The Princess, or Love at First Sight was written in Naples.

Above: Napoli (Naples), Italia (Italy)

The Parson’s Wedding was written in Basel.

Above: Basel, Switzerland

Cicilia and Clorinda, or Love in Arms, a two-part play – Cicilia, was written in Turin, Clorinda was written in Florence.

Above: Torino (Turin), Italia (Italy)

Above: Images of Firenze (Florence), Italia (Italy)

Thomaso, or the Wanderer was written in Madrid)

Above: Madrid, España (Spain)

At the Restoration in 1660, Killigrew returned to England along with many other Royalist exiles.

Above: Coronation of King Charles II – 29 May 1660

Charles rewarded his loyalty by making him Groom of the Bedchamber and Chamberlain to Queen Catherine.

Above: Catherine of Braganza (1638 – 1705)

He had a reputation as a wit; in his famous Diary, Samuel Pepys wrote that Killigrew had the office of the King’s fool and jester, with privilege to mock and revile even the most prominent without penalty.

“Up, and to the office, where all the morning.

At noon home to dinner, and thence with my wife and Deb. to White Hall, setting, them at her tailor’s, and I to the Commissioners of the Treasury, where myself alone did argue the business of the East India Company against their whole Company on behalf of the King before the Lords Commissioners, and to very good effect, I think, and with reputation.

That business being over, the Lords and I had other things to talk about, and among the rest, about our making more assignments on the Exchequer since they bid us hold, where at they were extraordinary angry with us, which troubled me a little, though I am not concerned in it at all.

Waiting here some time without, I did meet with several people, among others Mr. Brisband, who tells me in discourse that Tom Killigrew has a fee out of the Wardrobe for cap and bells, under the title of the King’s Fool or jester, and may with privilege revile or jeer anybody, the greatest person, without offence, by the privilege of his place.

Thence took up my wife, and home, and there busy late at the office writing letters, and so home to supper and to bed.

The House was called over today.

This morning Sir G. Carteret come to the Office to see and talk with me:

He assures me that to this day the King is the most kind man to my Lord Sandwich in the whole world, that he himself do not now mind any public business, but suffers things to go on at Court as they will, he seeing all likely to come to ruin, that this morning the Duke of York sent to him to come to make up one of a Committee of the Council for Navy Affairs, where, when he come, he told the Duke of York that he was none of them, which shews how things are nowadays ordered, that there should be a Committee for the Navy, and the Lord Admiral not know the persons of it!

And that Sir G. Carteret and my Lord Anglesey should be left out of it, and men wholly improper put into it. I do hear of all hands that there is a great difference at this day between my Lord Arlington and Sir W. Coventry, which I am sorry for.“

Diary of Samuel Pepys, Thursday, 13 February 1668

Along with Sir William Davenant, Killigrew was given a royal warrant to form a theatre company in 1660 — which gave Killigrew a key role in the revival of English drama.

Above: English poet/playwright William Davenant (1606 – 1668)

Killigrew beat Davenant to a debut, at Gibbon’s Tennis Court in Clare Market, with the new King’s Company.

Above: Thomas Killigrew

Its original members were Michael Mohun, William Wintershall, Robert Shatterell, William Cartwright, Walter Clun, Charles Hart and Nicholas Burt.

They played for a time at the old Red Bull Theatre, but in 1663 the company moved to the new Theatre Royal in Drury Lane.

Above: Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, England

(Unfortunately, Killigrew gained a reputation as an incompetent manager.

He was constantly in disputes with his actors and had to bribe his stars to keep working for him.)

Above: English actor William Cartwright (d. 1686)

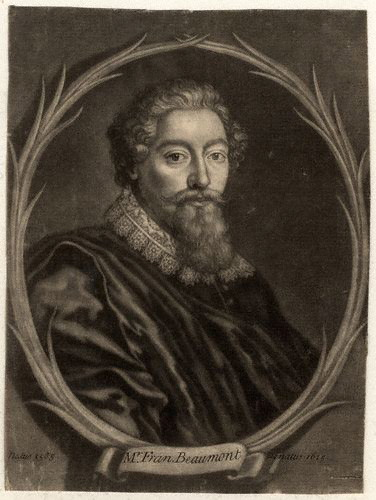

Killigrew staged plays by Aphra Behn, John Dryden, William Wycherley – and Thomas Killigrew, as well as revivals of Beaumont and Fletcher.

Above: English playwright Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689)

Above: English poet John Dryden (1631 – 1700)

Above: English playwright William Wycherley (1641 – 1716)

Above: English playwright Francis Beaumont (1584 – 1616)

Above: English playwright John Fletcher (1579 – 1625)

Having inherited the rights and repertory of the old King’s Men, the King’s Company performed many of Shakespeare’s works, in the rewritten forms that were so popular at the time and so disparaged later.

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Two Killigrew productions of his own Parson’s Wedding, in 1664 and 1672 – 1673, were cast entirely with women.

In 1673, Killigrew was appointed Master of the Revels.

He lost control of his theatre in a conflict with his son Charles in 1677.

(Charles, in turn, went bust a year later.)

Thomas Killigrew died at Whitehall on 19 March 1683.

Above: Whitehall Palace (1240 – 1698), London, England

Theater, like literature, is an act of defiance against silence.

And no one knew this better than the novelists who followed.

Perhaps no writer captured the dance of light and darkness quite like Charles Dickens.

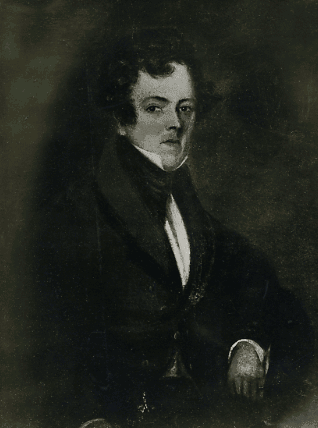

Above: English novelist Charles Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic.

He created some of literature’s best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era.

His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime and, by the 20th century, critics and scholars had recognized him as a literary genius.

His novels and short stories are widely read today.

Born in Portsmouth, Dickens left school at age 12 to work in a boot-blacking factory when his father John was incarcerated in a debtors’ prison.

Above: Portsmouth, England

Above: Charles Dickens’ birthplace, 393 Commercial Road, Portsmouth, England

Above: John Dickens (1785 – 1851)

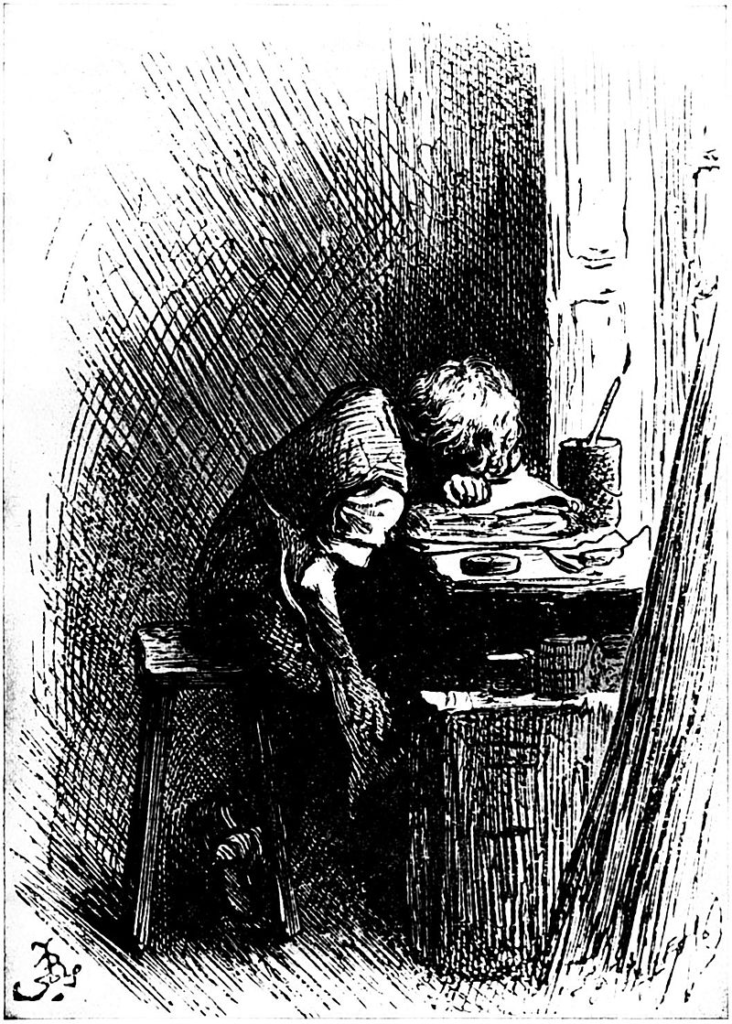

Above: Dickens at the blacking warehouse

After three years, he returned to school before beginning his literary career as a journalist.

Dickens edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas, hundreds of short stories and nonfiction articles, lectured and performed readings extensively, was a tireless letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children’s rights, education and other social reforms.

Above: Charles Dickens

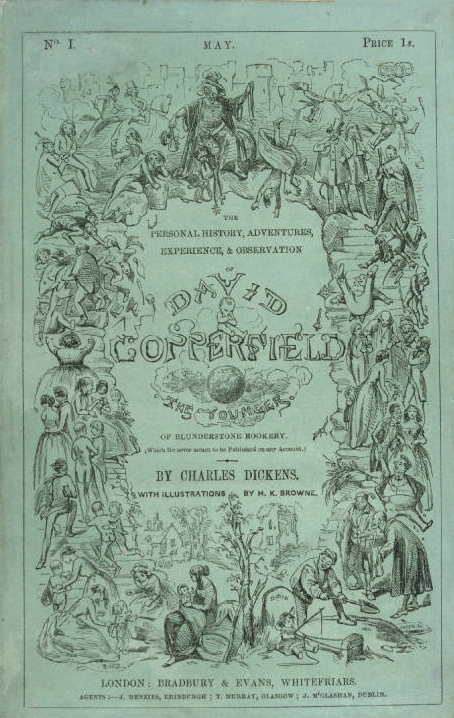

Dickens’s literary success began with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers, a publishing phenomenon — thanks largely to the introduction of the character Sam Weller in the fourth episode— that sparked Pickwick merchandise and spin-offs.

Above: The wise-cracking, warm-hearted servant Sam Weller from The Pickwick Papers made the 24-year-old Dickens famous.

Within a few years, Dickens had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire and keen observation of character and society.

His novels, most of them published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication.

Cliffhanger endings in his serial publications kept readers in suspense.

The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience’s reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback.

For example, when his wife’s chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her own disabilities, Dickens improved the character with positive features.

His plots were carefully constructed and he often wove elements from topical events into his narratives.

Masses of the illiterate poor would individually pay a halfpenny to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.

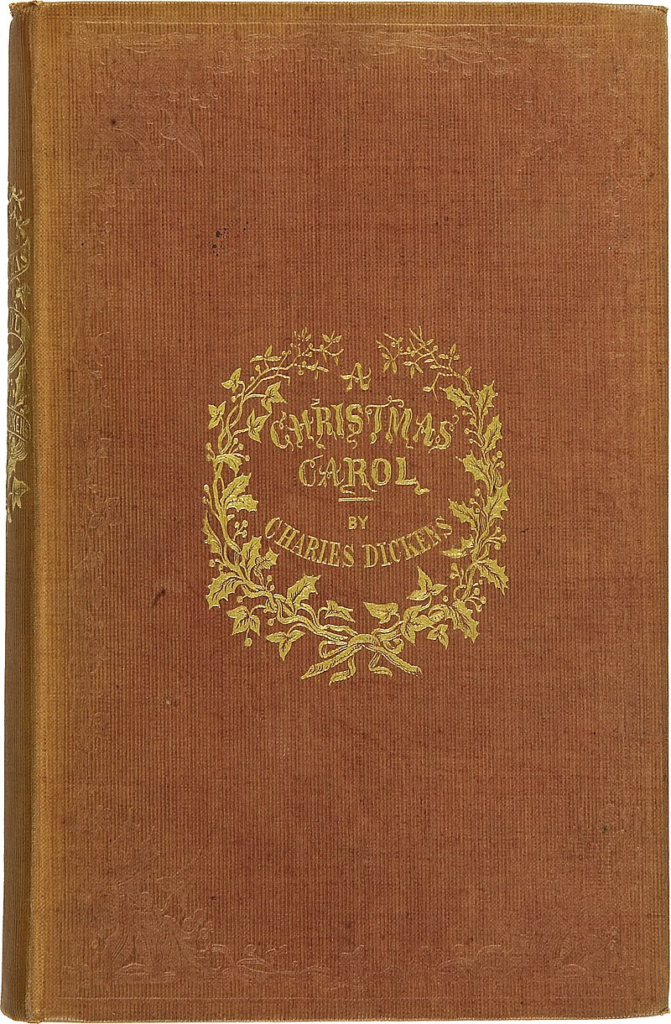

His 1843 novella A Christmas Carol remains especially popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every creative medium.

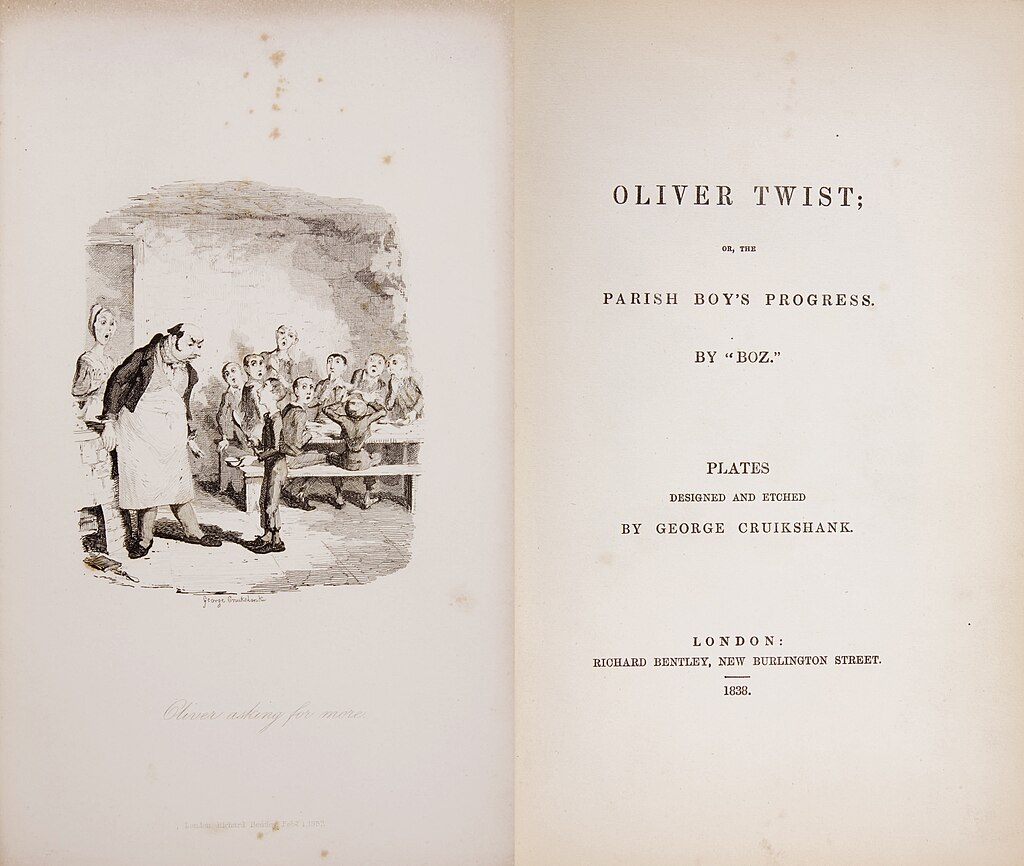

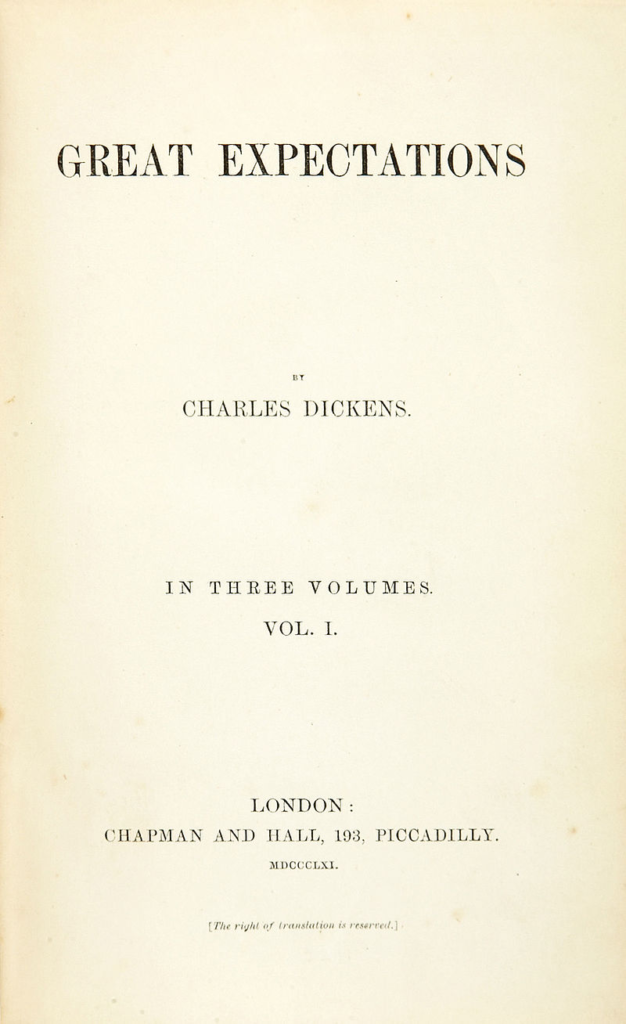

Oliver Twist and Great Expectations are also frequently adapted and, like many of his novels, evoke images of early Victorian London.

His 1853 novel Bleak House, a satire on the judicial system, helped support a reformist movement that culminated in the 1870s legal reform in England.

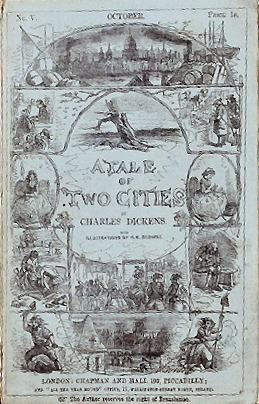

A Tale of Two Cities (set in London and Paris) is regarded as his best-known work of historical fiction.

The most famous celebrity of his era, he undertook, in response to public demand, a series of public reading tours in the later part of his career.

The term Dickensian is used to describe something that is reminiscent of Dickens and his writings, such as poor social or working conditions, or comically repulsive characters.

Above: Charles Dickens

In Great Expectations, fire warms the forge of Joe Gargery, a place of honest labor and simple kindness.

Yet, in the same breath, fire also consumes Miss Havisham’s decayed wedding dress, a spectral figure engulfed by the very passion she once sought to preserve.

For Dickens, fire was both the comfort of home and the raging force of fate.

Charles Dickens burned through hypocrisy with his novels, exposing the soot-covered underbelly of industrial England.

Dickens, born amidst the smoke of the Industrial Revolution, wielded fire both as destruction and as warmth — Miss Havisham’s tragic blaze, Joe Gargery’s comforting forge.

Dickens describes fire with a human quality, as if it breathes, leaps, and devours:

“The flames fell in love with her dress, and clasped her round with eager arms, and dragged her down to the ground, shrieking, with their fiery embrace.”

Dickens, ever the chronicler of human struggle, knew that fire could symbolize fate’s cruelty.

In Bleak House, the spontaneous combustion of Mr. Krook is described with eerie intensity:

“A thick yellow liquor, like oil, trickled down the window panes.

The smell of it filled the place with terror.”

Here, fire is not just destruction — it is punishment, inevitability, the unraveling of a life too steeped in its own filth.

Charles Dickens was born in an England choked by the smoke of industry and social inequality.

He wrote not for the elite, but for the masses, his serialized stories devoured by those who saw their own struggles in his pages.

His pen was his fire, searing into the consciousness of his readers the horrors of child labor, debtor’s prisons and hypocrisy.

Above: Charles Dickens

And then came Sinclair Lewis, a man who wielded words like a blacksmith wields flame, hammering out satirical critiques of American society.

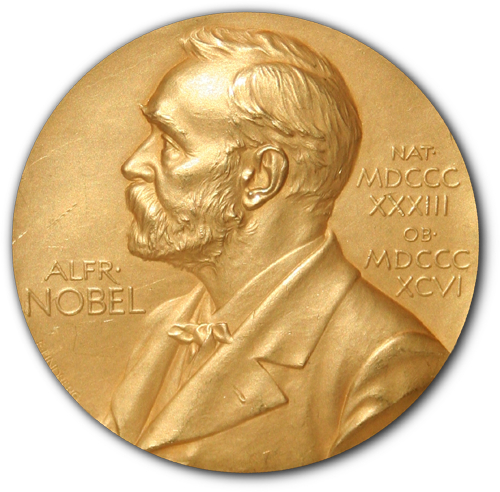

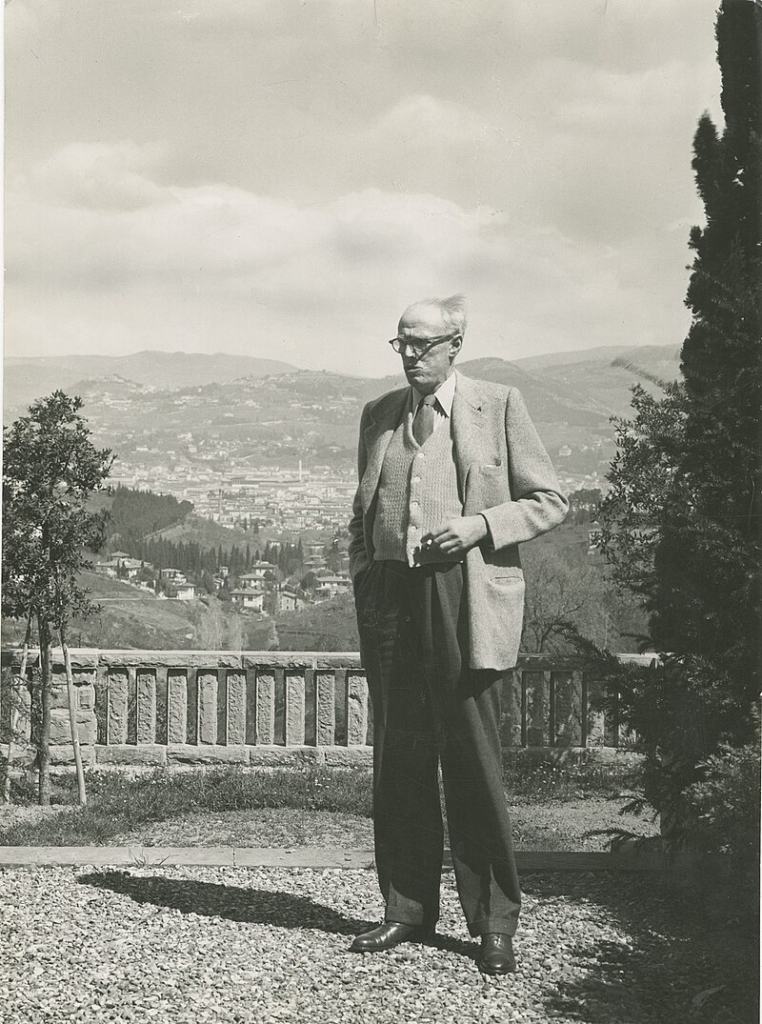

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American novelist, short-story writer and playwright.

Above: American writer Sinclair Lewis

In 1930, he became the first author from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded “for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters“.

Lewis wrote six popular novels:

- Main Street (1920)

- Babbitt (1922)

- Arrowsmith (1925)

- Elmer Gantry (1927)

- Dodsworth (1929)

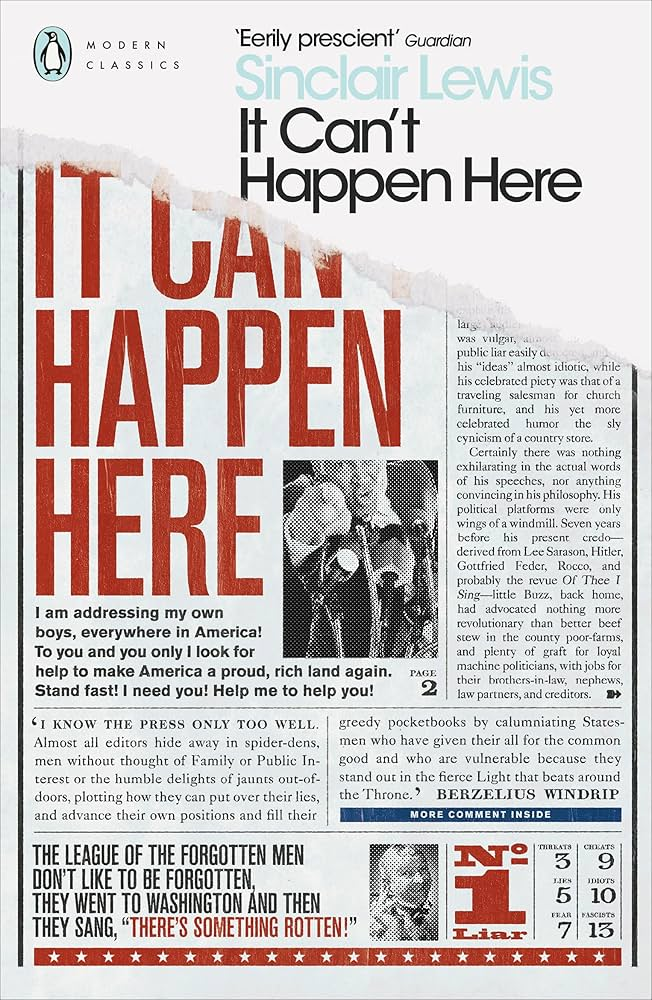

- It Can’t Happen Here (1935)

Several of his notable works were critical of American capitalism and materialism during the interwar period (1918 – 1939).

Lewis is respected for his strong characterizations of modern working women.

H. L. Mencken wrote of him:

“If there was ever a novelist among us with an authentic call to the trade, it is this red-haired tornado from the Minnesota wilds.“

Above: American writer Henry Louis Mencken (1880 – 1956)

Sinclair’s novels sparked controversy, his pen igniting more fires than any matchstick ever could.

He understood that fire did not have to be seen to be felt.

A single sentence, well-placed, could set an entire nation ablaze.

Sinclair Lewis would take up that torch in America, exposing the rot beneath the surface of middle-class respectability.

Where Dickens sought to inspire reform, Lewis wielded satire like a flame-thrower, scorching the illusions of small-town virtue and capitalist greed.

Above: Sinclair Lewis

His novel Babbitt ridiculed the emptiness of American conformity, and It Can’t Happen Here warned of the creeping dangers of fascism — warnings that, like embers in a strong wind, still flicker in relevance today.

Sinclair Lewis torched the illusions of the American Dream with satire as sharp as any flame.

Sinclair Lewis, a literary arsonist, set fire to hypocrisy with every word he wrote.

While Lewis’ descriptions of literal fire are less prominent, his Main Street and Babbitt both describe the burning pressures of conformity, the social fires that threaten to consume individuality.

In Arrowsmith, fire appears in a symbolic form:

The burning need for scientific truth against the backdrop of ignorance.

Sinclair Lewis wielded fire as satire.

His America was a landscape of burning pressures — social expectation, corporate greed, the unrelenting heat of conformity.

His characters, trapped in the flames of a world that demands success at any cost, either succumb to the fire or escape its grasp, often scarred but wiser.

Above: Sinclair Lewis

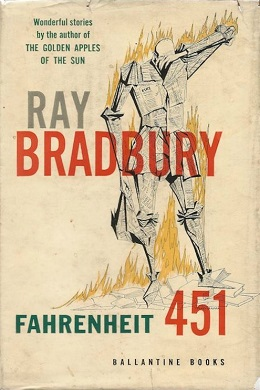

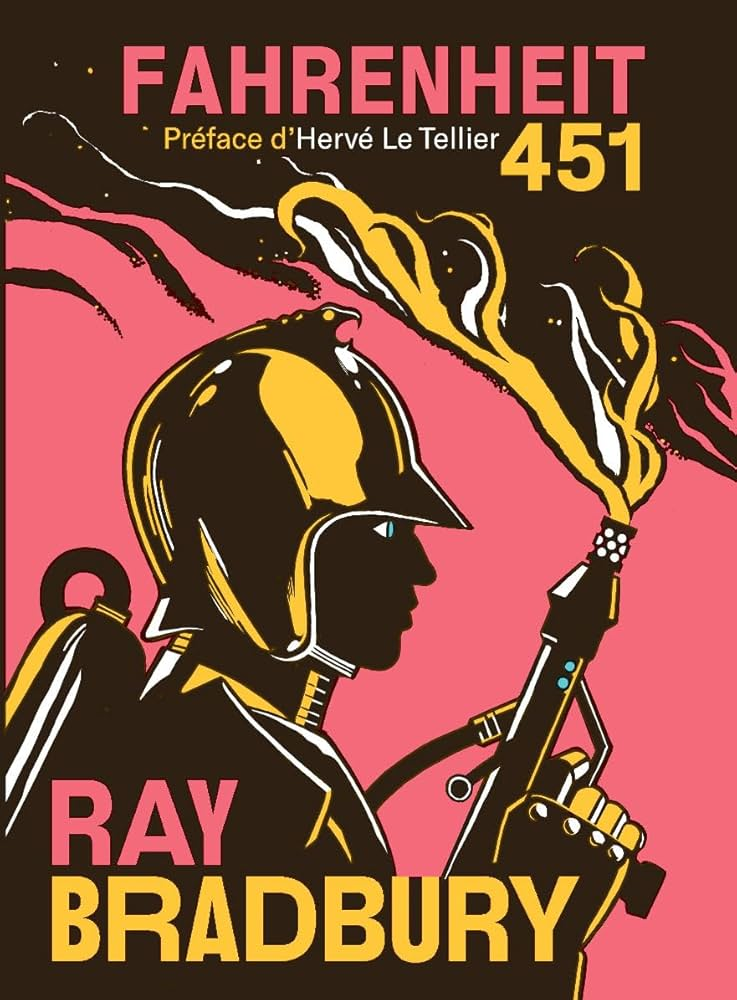

Literature has long carried the essence of fire, from the hearthside tales of old to the burning pages of Fahrenheit 451.

Some authors have seen fire as destruction, a force that swallows the past whole, leaving nothing but cinders.

Others have seen it as passion, the kindling of inspiration, the glow of a lover’s gaze.

Still others have wielded fire as a metaphor for rebellion, for defiance, for the refusal to be extinguished.

What is it that connects fire and the written word?

Both can be instruments of destruction — or tools of illumination.

Creativity is a slow-burning flame, nurtured by discipline, fanned by passion, shielded against doubt.

Some writers burn too brightly, exhausting themselves in the fever of their work.

Others smolder for years, their stories gathering heat until, one day, they burst forth in brilliance.

A writer’s fire must be tended.

Feed it too little, and it dies.

Give it too much air, and it rages out of control.

But when balanced, it warms the soul and lights the way — for the writer, for the reader, for all who seek the glow of truth within the pages of a book.

Fire has burned its way through literature in countless forms —sometimes a whispering ember, sometimes a raging inferno.

Writers have long been mesmerized by its flickering duality, shaping it into a symbol of passion, destruction, knowledge, and rebirth.

Let us explore how fire has been captured in words.

“Love is a fire.

But whether it is going to warm your hearth or burn down your house, you can never tell.“

Joan Crawford

Above: American actress Joan Crawford (1909 – 1977)

“The most powerful weapon on Earth is the human soul on fire.“ Ferdinand Foch

Above: French General Ferdinand Foch (1851 – 1929)

“I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land (fire and ruin intertwined)

Above: American-born British poet Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888 – 1965)

From the smoldering intensity of desire in Shakespeare’s sonnets to the fevered longing of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, fire has long been the language of love and obsession.

It is the blush of a first encounter, the slow burn of devotion, the reckless blaze that consumes lovers beyond reason.

Above: English writer Emily Brontë (1818 – 1848)

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.“ Plutarch

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Plutarch (46 – 129)

“Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

John Milton, Paradise Lost (Satan’s rebellion is a fire that refuses to be extinguished)

Above: English poet John Milton (1608 – 1674)

“We are all fools in fire and life.“

William Shakespeare, King Lear

Above: King Lear, George Frederick Bensell (2020)

Prometheus stole fire from the gods to give humanity wisdom, and ever since, fire has burned at the heart of knowledge.

Above: Prometheus

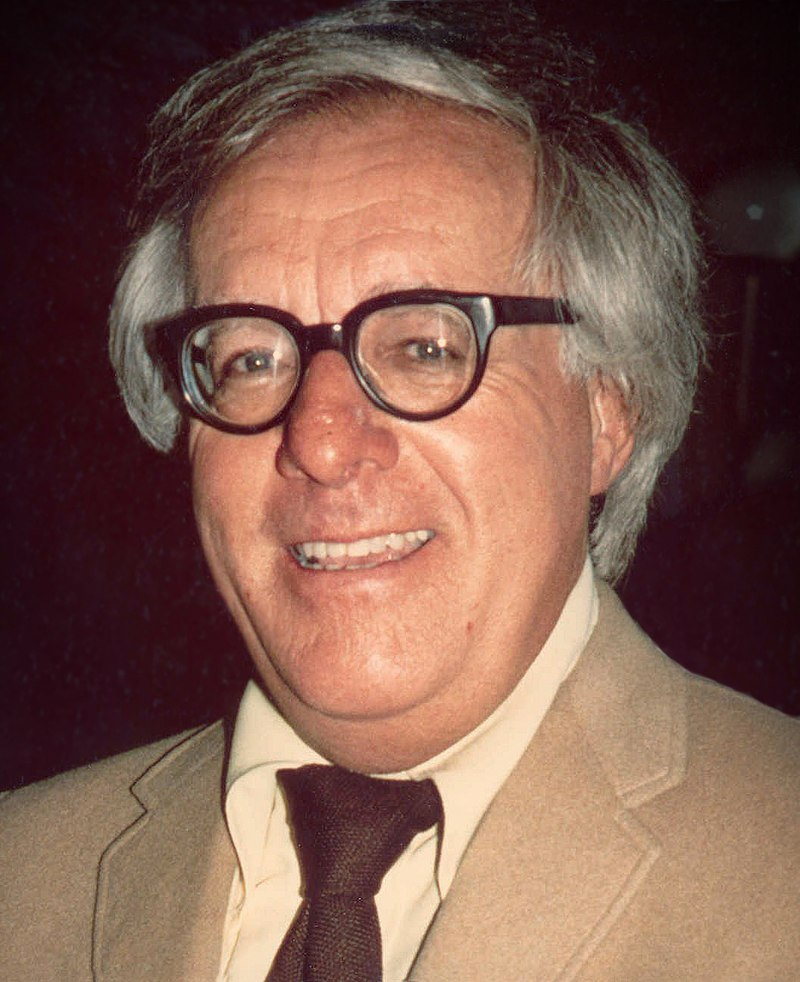

In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury turned fire into both an instrument of censorship and a symbol of illumination — books burning in the hands of the fearful, yet their words surviving in the minds of the brave.

Above: American writer Ray Bradbury (1920 – 2012)

Bradbury, in Fahrenheit 451, takes fire and places it in the hands of men, turning them into agents of ignorance rather than enlightenment.

The firemen do not save — they destroy, reducing books to ash.

But fire, as always, refuses to be tamed:

From the ashes of books, ideas rise, flickering back to life in human memory.

Fire, in its purest form, is the spark of curiosity, the fever of creation, the forge where ideas are tempered into wisdom.

“Fire is the test of gold; adversity, of strong men.“

Seneca

Above: Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger (4 BC – AD 65)

“It was a pleasure to burn.“

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

“From the ashes a fire shall be woken, a light from the shadows shall spring.“

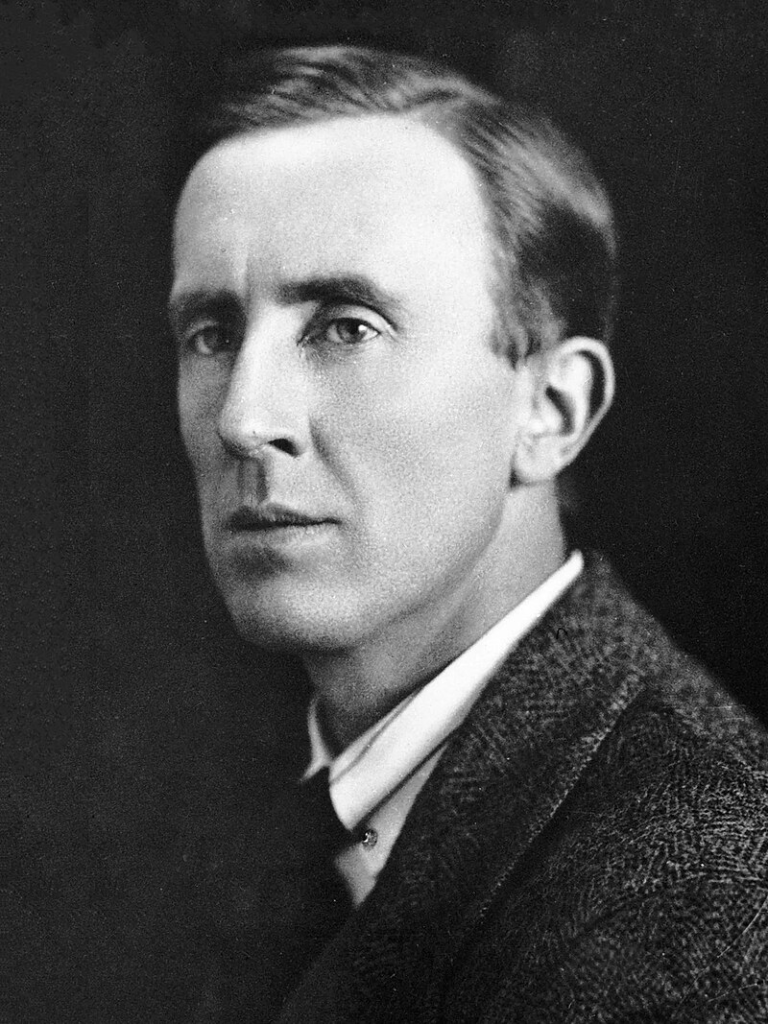

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

Above: South African writer John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892 – 1973)

From the burning of Troy to the flames that consume Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, fire is destruction, but not always an end.

It clears the old to make way for the new.

Above: The burning of Troy

In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë uses fire to reflect transformation—whether it is Bertha Mason’s madness setting Thornfield Hall ablaze or the embers of Jane’s passion smoldering beneath her outward restraint.

Above: English writer Charlotte Brontë (1816 – 1855)

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns yourself more than them.“

Chinese Proverb

Above: Flag of China

“We didn’t start the fire, it was always burning since the world’s been turning.“

Billy Joel

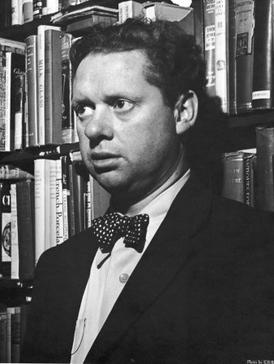

“Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.“

Dylan Thomas

Above: Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (1914 – 1953)

Fire is the weapon of the revolutionary, the voice of the unyielding.

Joan of Arc burned for her defiance, the Great Fire of London reshaped a city, and in The Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen becomes the “girl on fire”, her very existence a spark of resistance.

Above: Jeanne d’Arc (1412 – 1431)

Joan of Arc (French: Jeanne d’Arc) is honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronation of Charles VII of France during the Hundred Years’ War (1337 – 1453).

Claiming to be acting under divine guidance, she became a military leader who transcended gender roles and gained recognition as a savior of France.

Above: French King Charles VII (1403 – 1461)

Joan was born to a propertied peasant family at Domrémy in northeast France.

Above: Birthplace of Jeanne d’Arc, Doméry, France

In 1428, she requested to be taken to Charles VII, later testifying that she was guided by visions from the archangel Michael, Saint Margaret, and Saint Catherine to help him save France from English domination.

Above: Archangel Michael wages war in Heaven

Above: Margaret of Antioch (289 – 304)

Above: Catherine of Alexandria (287 – 305)

Convinced of her devotion and purity, Charles sent Joan, who was about seventeen years old, to the siege of Orléans as part of a relief army.

She arrived at the city in April 1429, wielding her banner and bringing hope to the demoralized French army.

Nine days after her arrival, the English abandoned the siege.

Above: Jeanne d’Arc at the siege of Orléans (12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429)

Joan encouraged the French to aggressively pursue the English during the Loire Campaign (12 October 1428 – 18 June 1429), which culminated in another decisive victory at Patay, opening the way for the French army to advance on Reims unopposed, where Charles was crowned as the King of France with Joan at his side.

Above: Jeanne d’Arc

Above: Battle of Patay – 18 June 1429

Above: Subé Fountain, Reims, France

These victories boosted French morale, paving the way for their final triumph in the Hundred Years’ War several decades later.

After Charles’s coronation, Joan participated in the unsuccessful siege of Paris in September 1429 and the failed siege of La Charité in November.

Above: Jeanne d’Arc at the siege of Paris (3 – 8 September 1429)

Her role in these defeats reduced the court’s faith in her.

In early 1430, Joan organized a company of volunteers to relieve Compiègne, which had been besieged by the Burgundians —French allies of the English.

Above: Siege of Compiègne (May – November 1430)

She was captured by Burgundian troops on 23 May. After trying unsuccessfully to escape, she was handed to the English in November.

She was put on trial by Bishop Pierre Cauchon on accusations of heresy, which included blaspheming by wearing men’s clothes, acting upon visions that were demonic, and refusing to submit her words and deeds to the judgment of the church.

Above: French Bishop Pierre Cauchon (1371 – 1442)

She was declared guilty and burned at the stake on 30 May 1431, aged about nineteen.

Fire is the rallying cry of those who refuse to be extinguished.

“The most tangible of all visible mysteries—fire.“

Leigh Hunt

Above: English poet Leigh Hunt (1784 – 1859)

“She walked as if the stars had set fire to her soul.“

Winston Churchill

Above: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965)

“I set myself on fire and people come to watch me burn.“

John Wesley

Above: English theologian John Wesley (1703 – 1791)

And what of poetry?

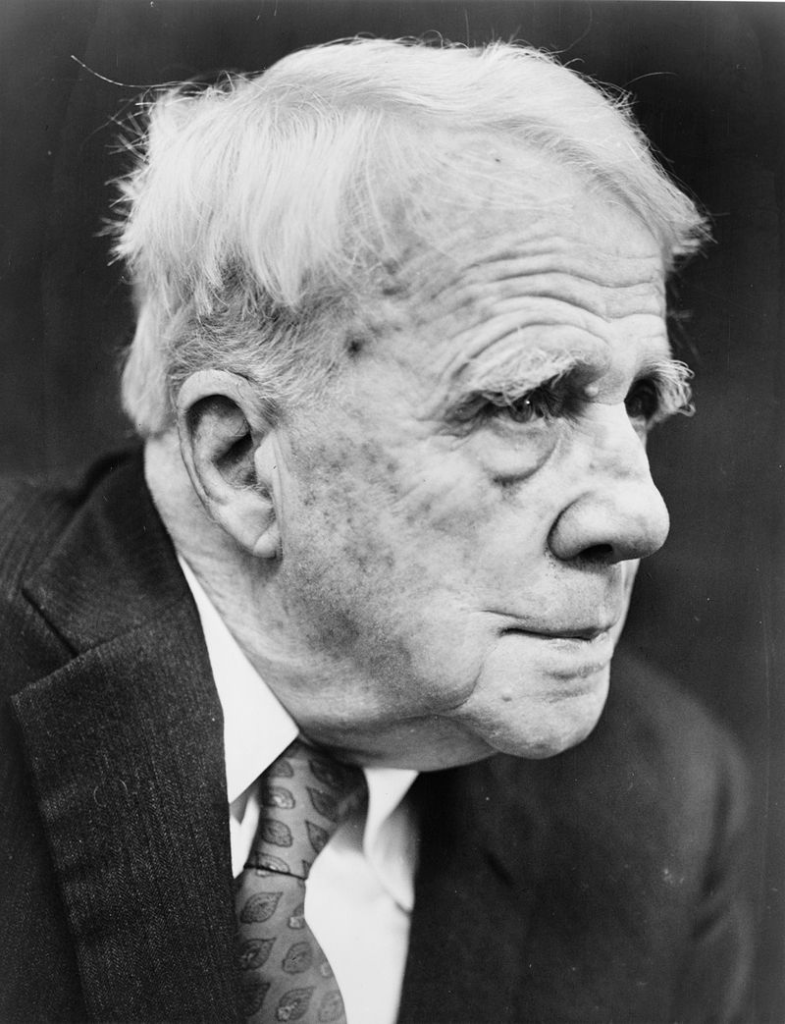

Robert Frost’s Fire and Ice asks whether the world will end in flame or in frozen indifference.

Above: American poet Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Fire is desire, passion, unchecked hunger.

Ice is hatred, slow and silent.

Which is worse?

The poet leaves it to us to decide.

There is a certain poetry in flames, the way they dance, the way they consume without remorse, the way they create light even as they destroy.

In poetry and prose alike, fire is mesmerizing, hypnotic — sometimes cruel, sometimes kind, but never indifferent.

Fire, the way it moves, the way it breathes, the way it plays with light and shadow – let us step closer to the flames and observe their flickering dance through the eyes of great writers.

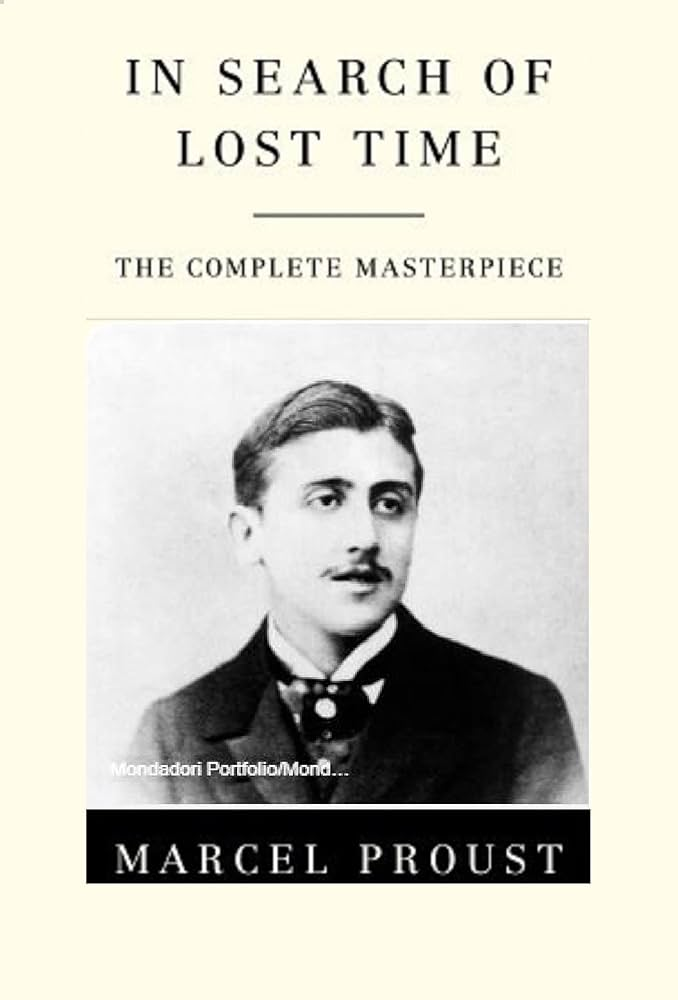

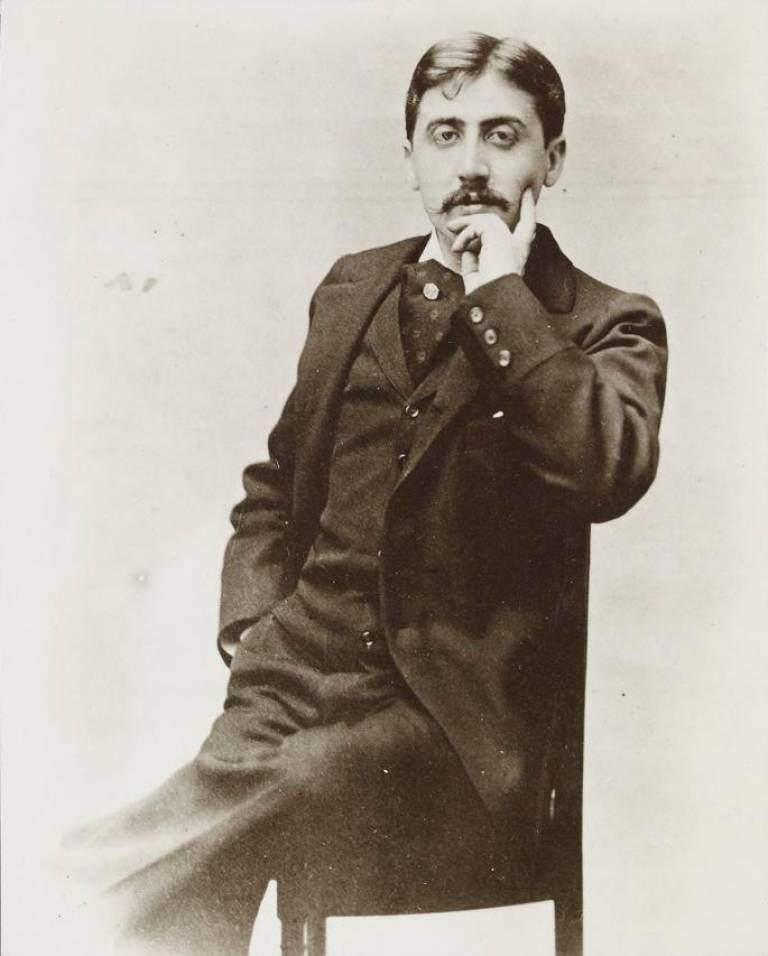

While Marcel Proust was more often preoccupied with memory, sensation and time, he did capture the visual poetry of fire.

Here’s a striking passage from In Search of Lost Time:

“Each flame that rose from the log, as though it were endowed with an individual existence, would suddenly rise up straight, darting forth its sharp tongue, put out feelers, sketch attitudes, suddenly change its place, die away, and begin again, while the log itself, like an ogre’s heart that was being broiled for his children’s dinner, crackled and moaned, with hot bursts of sound, and showered all around it a rain of melting red-hot particles.“

Proust, ever the master of sensory detail, sees fire as a living thing —dancing, stretching, consuming, and speaking in its own secret language.

Above: French novelist Marcel Proust (1871 – 1922)

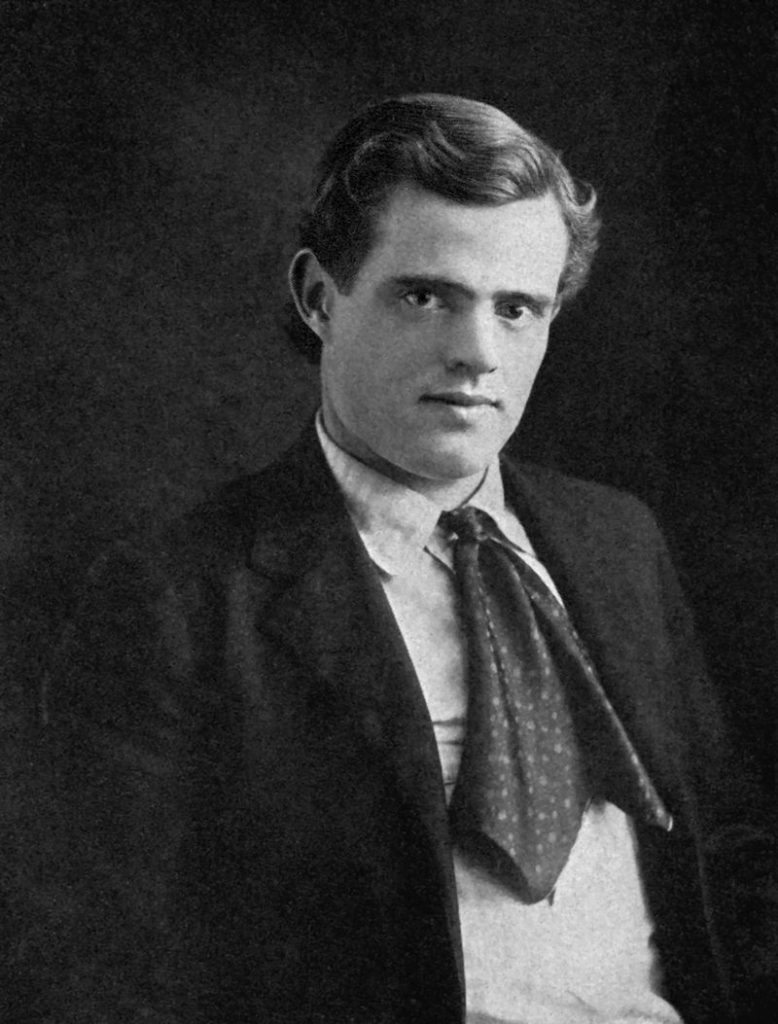

Jack London’s To Build A Fire describes fire in the cruel Arctic cold with a brutal realism:

“The flame sputtered and went out.

The sticks were full of ice, and the fire of late had been burning low.

The man turned aside from the stove to get more wood, and the freezing air bit into his cheeks and nose, making them sting and tingle.

He moved quickly, stamping his feet, but the numbing cold was coming on fast, creeping up his legs, dulling his fingers.“

Here, fire is not just warmth — it is survival, and its absence is death.

Above: American writer Jack London (1876 – 1916)

Ray Bradbury, of course, made fire his muse, both terrifying and seductive in Fahrenheit 451:

“It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed.

With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning.“

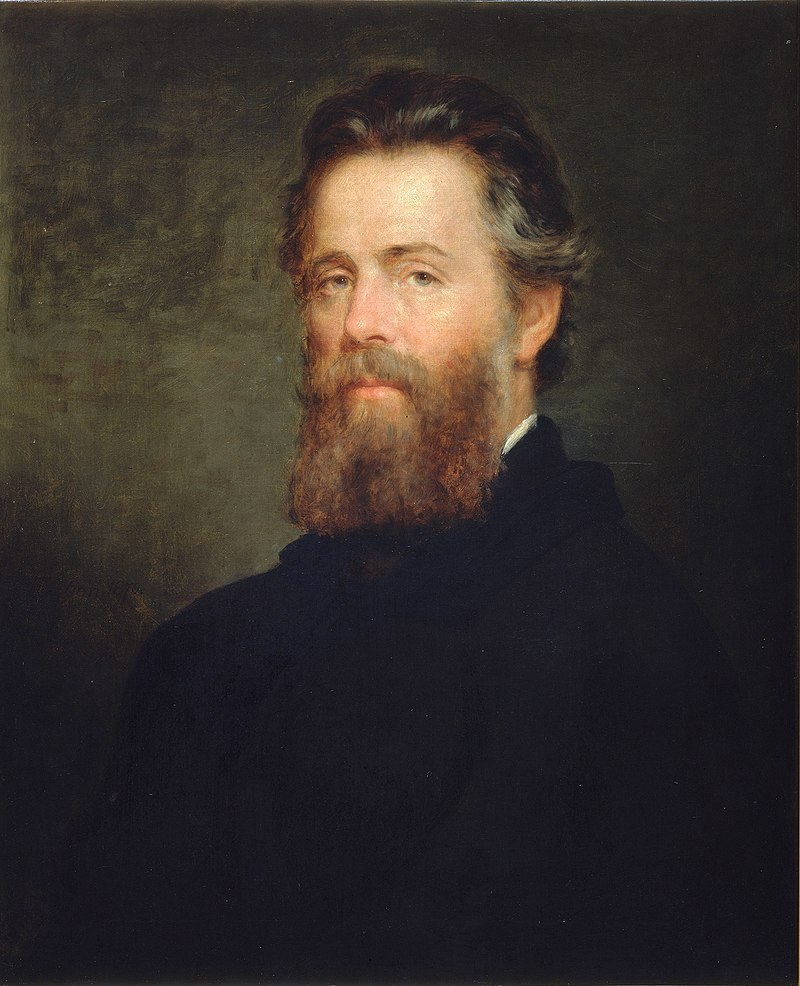

Herman Melville gives us the eerie, otherworldly glow of St. Elmo’s fire on a ship at sea in his classic Moby Dick:

“For an instant, the tranced boat’s crew stood still, then turned.

‘The ship?

Great God, where is the ship?’

Soon they, through dim, bewildering mediums, saw her sidelong fading phantom, as, in the gaseous Fata Morgana, only the uppermost masts out of the water, while fixed by infatuation, or fidelity, or fate, to their once lofty perches, the pagan harpooneers still maintained their sinking look-outs on the sea.“

Above: American writer Herman Melville (1819 – 1891)

“I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.“

Emily Dickinson’s fire is introspective, a searchlight illuminating the soul.

Above: American poet Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886)

In Dante’s Inferno, fire is both a torment and a truth:

“There is no greater pain than to remember happiness in the midst of wretchedness.“

Flames lick at the lost souls, their glow casting shadows of regret.

Above: Italian writer Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321)

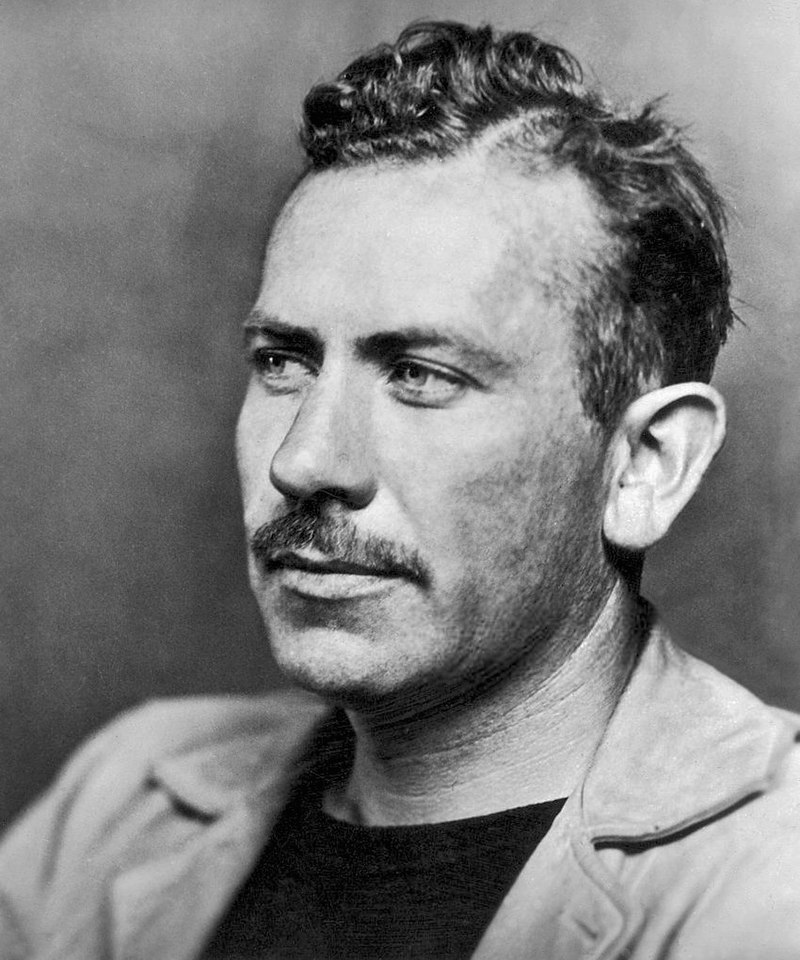

Fire is the final act of destruction in Steinbeck’s masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath:

“And as the embers grew dull and the sky grew dark, a sadness settled in.

There was nothing left now, only the road, the dust, and the unknown beyond.“

Above: American writer John Steinbeck (1902 – 1968)

And then, there was Alfred Adler.

A few years later, another mind that would kindle its own flame was born — Alfred Adler, a psychologist who saw fire not in the external world but within the human spirit.

His theories of inferiority and striving were born of an understanding that within every person, there is a burning need — a hunger to rise, to conquer, to illuminate.

The fire within, he argued, could warm or consume, depending on how it was tended.

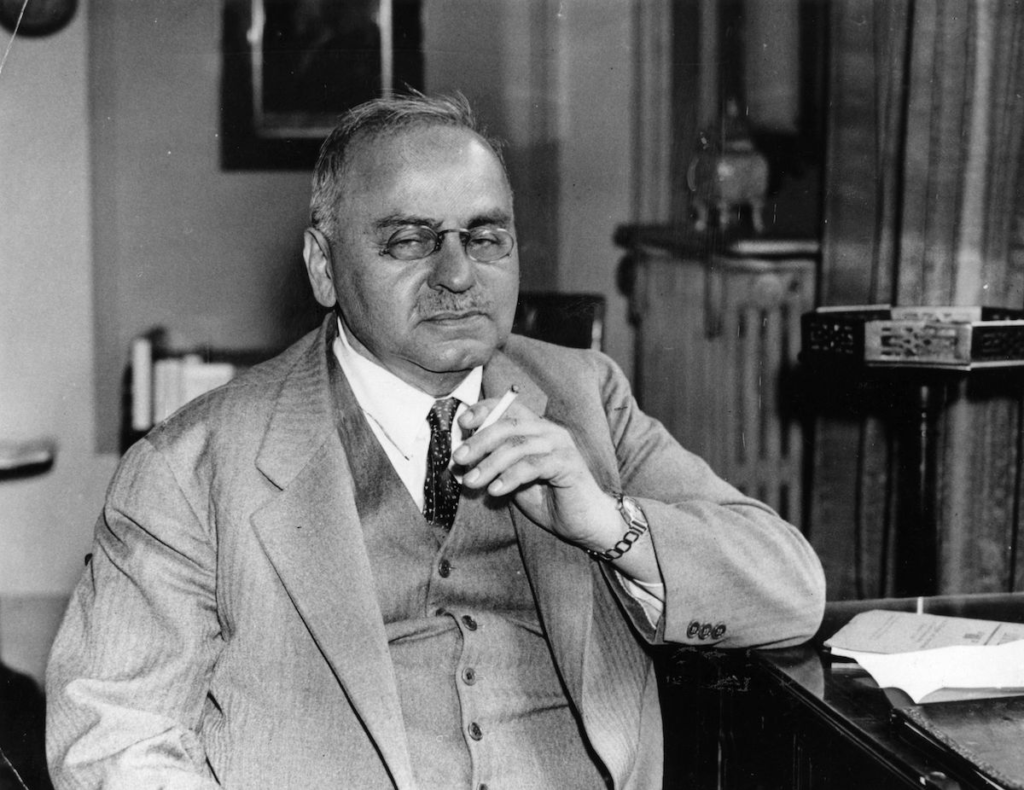

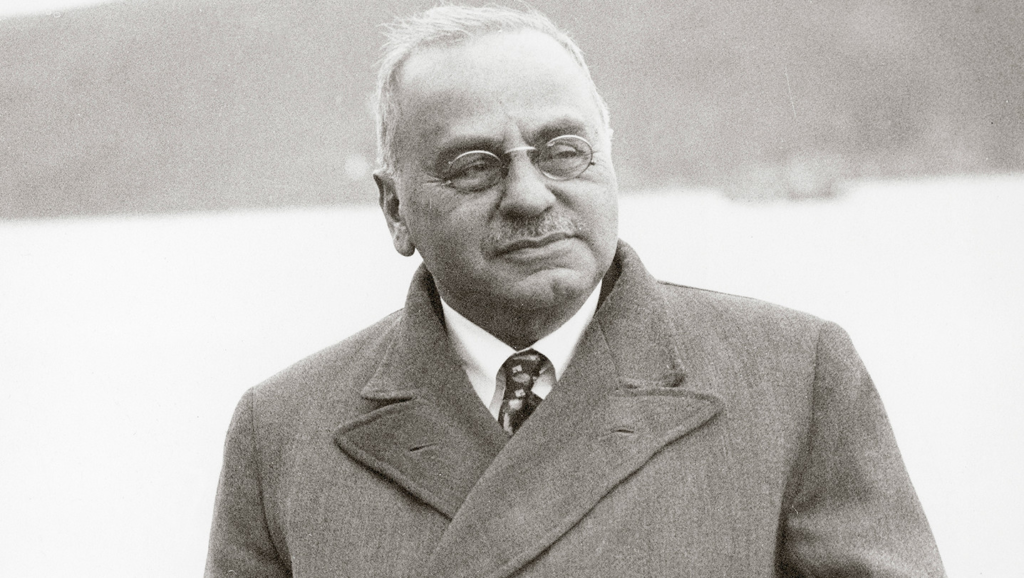

Above: Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler (1870 – 1937)

Alfred Adler (7 February 1870 – 28 May 1937) was an Austrian medical doctor, psychotherapist, and founder of the school of individual psychology.

His emphasis on the importance of feelings of belonging, relationships within the family, and birth order set him apart from Freud and others in their common circle.

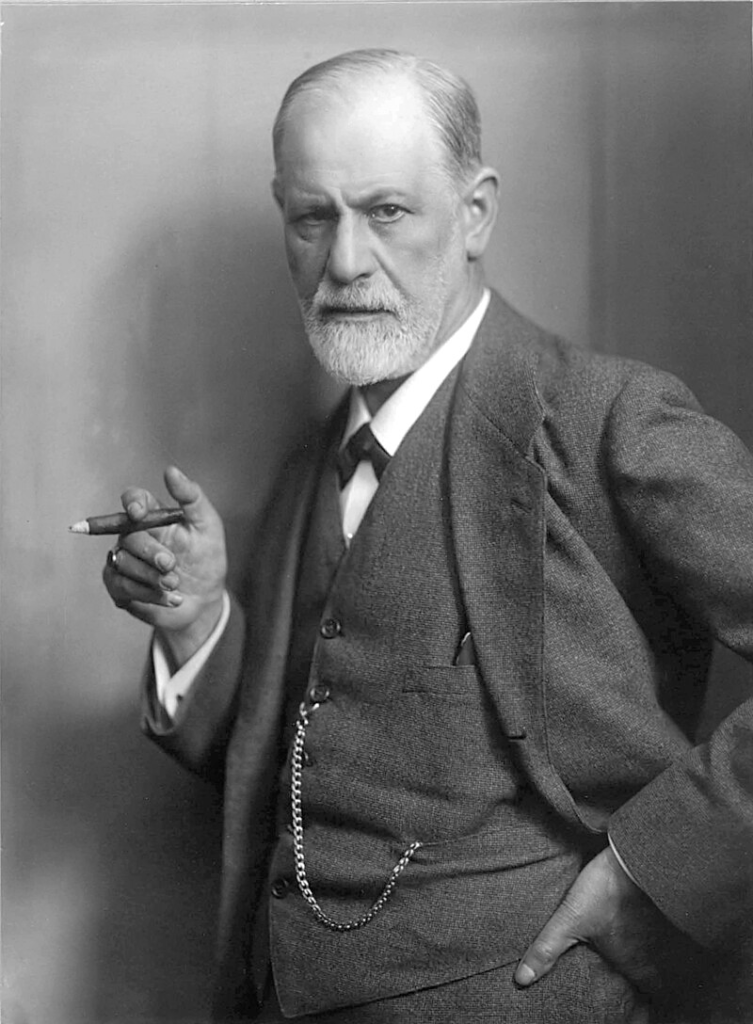

Above: Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

Adler proposed that contributing to others (social interest or Gemeinschaftsgefühl) was how the individual feels a sense of worth and belonging in the family and society.

His earlier work focused on inferiority, coining the term inferiority complex, an isolating element which he argued plays a key role in personality development.

Alfred Adler considered a human being as an individual whole, and therefore he called his school of psychology “individual psychology“.

Adler was the first to emphasize the importance of the social element in the re-adjustment process of the individual and to carry psychiatry into the community.

A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Adler as the 67th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.

Alfred Adler sparked a revolution in psychology, defying Freud and redefining human motivation.

Above: Sigmund Freud’s couch

Adler did not wield fire in the form of books or plays, but in the realm of ideas.

Adler did not describe fire in a physical sense, but his psychological theories burned with the idea of inner flames — the inferiority complex, the drive to prove oneself, the fire within that propels ambition.

Above: Alfred Adler

To Adler, fire was a metaphor:

Some are consumed by it.

Others are forged within it.

Adler challenged the psychological orthodoxy of his time, rejecting Freud’s notion that humans were driven primarily by repressed desires.

Instead, Adler saw the human spirit as a force struggling for significance — burning with a need for purpose, for self-improvement.

Where others saw people as prisoners of their past, Adler saw them as architects of their future.

Above: Alfred Adler

Adler saw fire in the human soul — not in destruction, but in drive.

The inferiority complex is a smoldering ember, a heat that compels men to prove themselves, to climb, to strive.

Some are burned by it.

Others are warmed and strengthened.

This is the fire of ambition, the heat that propels great men forward— sometimes into glory, sometimes into ruin.

His ideas, radical at the time, would go on to shape modern psychology, influencing everything from self-help to education.

Above: Alfred Adler

The blank page is cold before the writer’s touch, a winter’s field before the kindling of thought.

But then — ah, then! — the first spark, the strike of flint against stone, and a small ember glows in the mind’s cavern.

A phrase, a character, a scene — it dances like the first whisper of flame, uncertain yet full of promise.

And then, there is the fire of solitude — the flickering glow of a campfire, a lone traveler staring into the embers, watching them pulse like the heartbeat of the earth.

I have known such fires.

The warmth of a campfire, the curling flames of the hearth, gas burners in an Eskişehir quiet night.

Each flame a witness to a moment, a thought, a story untold.

A solitary man sits.

The flame dances, casting shadows, licking at the darkness beyond.

I watch, searching the embers for answers, for whispers of wisdom carried in the smoke.

Does the fire speak?

Or is it merely the echo of my own thoughts, reflected in the glow?

The fires are there — burning in history, in literature, in psychology.

Some rage in the streets, others flicker in the human soul.

Fire, in all its forms — consuming, illuminating, comforting, and destroying — has ever been the companion of humankind.

It has lit the halls of learning, burned the bridges of history, and whispered to the solitary writer, casting long shadows upon the walls of inspiration.

We return to where we began: