Tuesday 11 February 2025

Eskişehir / Ankara, Türkiye

The day begins in the embrace of motion — a train bound for Ankara, a city that has become familiar yet remains distant from the rhythms of my daily life.

The capital of modern Türkiye has many roles to play.

It is the conflicts between these roles that make the city so intriguing.

Above: Ankara, Türkiye

When Atatürk declared Ankara the capital of the new Turkish Republic in 1923, he was making a calculated move away from the Byzantine and Ottoman associations of Istanbul and its past and back to the original Anatolian heartlands.

Above: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the father of modern Türkiye

Atatürk called for a national election to establish a new Turkish Parliament seated in Angora (Ankara) – the “Grand National Assembly” (GNA).

On 23 April 1920, the GNA opened with Atatürk as the Speaker.

Above: Seal of the Turkish Parliament

When Atatürk first moved his headquarters to Ankara in 1919, at the beginning of the War of Independence, the town had a mere 30,000 inhabitants.

Ankara’s present population is nearly six million.

Above: Atatürk Railway Museum, Ankara

The contrast between the old town and the new city centre contributes to Ankara’s strange character and points to its split identity, one that is more marked than in any other city in Türkiye.

The main boulevard is lined with luxury high rise hotels and impressive new embassies and government buildings, while in the old streets around the Citadel and the Ulus Meydanı (the People’s Square) you could be forgiven for thinking you were back in a simple and traditional Anatolian town.

It is a split that symbolizes the curious dilemma of Türkiye as a whole:

Part modern, part traditional.

Above: Ankara Castle

Above: Ulus Meydanı, Ankara

Türkiye’s “other city” may not have any showy Ottoman palaces or regal façades, but Ankara thrums in a vivacious youthful beat unmarred by the tug of history.

Above: Temple of Augustus and Rome, Ankara

Drawing comparisons with Istanbul is pointless – the flat modest surroundings are hardly the stuff of national poetry – but the civic success of this dynamic and intellectual city is assured thanks to student panache and foreign embassy intrigue.

The country’s capital has made remarkable progress from a dusty Anatolian backwater to today’s sophisticated arena for international affairs.

Above: Atakule TV tower with attached shopping mall in Ankara

Türkiye’s economic success (?) is reflected in the booming (?) restaurant scene around Kavaklıdere and the ripped jean politik of Kızılay’s sidewalk cafés, frequented by hip students, old timers and businessmen alike.

Above: Kavaklidere, Ankara

And while the dynamic street life is enough of a reason to visit, Ankara also boasts two extraordinary monuments to the Turkish story – the beautifully conceived Museum of Anatolian Civilizations and the Anıt Kabir, a colossal tribute to Atatürk, modern Türkiye’s founder.

Above: Logo of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara

Above: Anıtkabir (the mausoleum with Atatürk’s tomb) in Ankara

Few cities have changed so much so quickly as the Turkish capital of Ankara.

Above: Ankara Kocatepe Mosque

Few individuals have changed as much as I have since my last visit here.

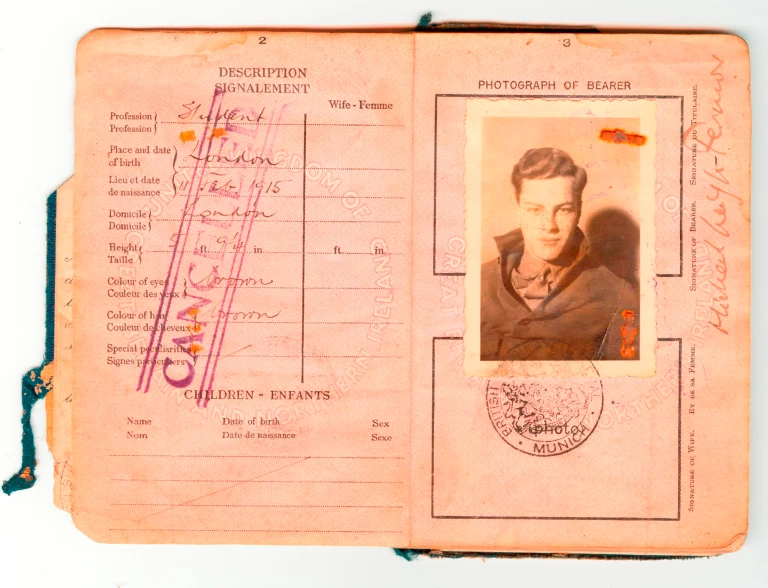

Above: Your humble blogger

When Atatürk declared it capital of his nascent republic, it was little more than a small provincial town, known chiefly for its production of angora, soft goat’s wool.

Above: Flag of the Turkish Republic

Fast forward to the present day and it is a bustling modern city, its buildings spreading to the horizon in each direction across what, not too long ago, was unspoiled steppe.

This was, of course, Atatürk’s vision all along – a carefully planned attempt to create a seat of government worthy of a modern Westernized state.

Above: Republic Museum, Ankara

Many visitors to Türkiye, of course, believe Istanbul to be the nation’s capital and comparisons between the two cities are almost inevitable.

Above: İstanbul

While Ankara is never going to be as attractive a destination, it certainly holds enough to keep you occupied for a while – diverting sights, good restaurants and pumping nightlife.

Above: YDA building, Ankara

Most visitors’ first taste of Ankara is Ulus, an area where a couple of Roman monuments lurk beneath the prevailing modernity.

Above: Ulus, Ankara

Heading east you will pass the superb Museum of Anatolian Civilizations before heading up to Hisar, the oldest part of the city.

Above: Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara

Here, the walls of a Byzantine citadel enclose an Ottoman era village of cobbled streets.

Climbing on up will buy you a jaw-dropping city view.

Above: Aerial view of Kale (with Ankara Citadel in the background) in Ankara

Heading south of Ulus you will soon come to student Kızılay, filled with bars and cheap restaurants.

Above: Atatürk Bulvarı, Kızılay, Ankara

Real estate values increase exponentially as you move south again towards Kavaklıdere and Çankaya where the cafés and restaurants are somewhat more salubrious.

Above: Kavaklıdere, Ankara

Above: Çankaya, Ankara

I am neither drawn to the capital’s youthful beat nor its historic tug.

I come not to revisit the Museum nor the mausoleum, not to climb above the Citadel nor crawl along the pubs.

My companion for the journey, Daly, is on his way to take the IELTS test, and I choose to accompany him, not merely as a gesture of support, but perhaps as a subconscious need to witness someone in pursuit of a future yet to be written.

International English Language Testing System (IELTS) is an international standardized test of English language proficiency for non-native English language speakers.

(Daly hails from Tunisia.)

Above: Flag of Tunisia

IELTS is jointly managed by the British Council, the International Development Program (IDP) and Cambridge English.

It was established in 1989.

IELTS is one of the major English-language tests in the world.

The IELTS test has two modules:

Academic and General Training.

IELTS One Skill Retake was introduced for computer-delivered tests in 2023, which allows a test taker to retake any one section (Listening, Reading, Writing and Speaking) of the test.

IELTS is accepted by most Australian, British, Canadian, European, Irish and New Zealand academic institutions, by over 3,000 academic institutions in the United States, and by various professional organizations across the world.

Above: Flag of the European Union

IELTS is approved by UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) as a Secure English Language Test for visa applicants only inside the UK.

Above: Flag of the United Kingdom

It also meets requirements for immigration to Australia, where Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and Pearson Test of English Academic are also accepted, and New Zealand.

Above: Flag of Australia

Above: Flag of New Zealand

In Canada, IELTS, Test d’évaluation de français (TEF) or the Canadian English Language Proficiency Index Program (CELPIP) are accepted by the immigration authority.

Above: Flag of Canada

No minimum score is required to pass the test.

An IELTS result or Test Report Form is issued to all test takers with a score from “Band 1” (“non-user“) to “Band 9” (“expert user“) and each institution sets a different threshold.

There is also a “Band 0” score for those who did not attempt the test.

Institutions are advised not to consider a report older than two years to be valid, unless the user proves that they have worked to maintain their level.

In 2017, over three million tests were taken in more than 140 countries, up from two million tests in 2012, 1.7 million tests in 2011 and 1.4 million tests in 2009.

In 2007, IELTS administered more than one million tests in a single 12-month period for the first time ever, making it the world’s most popular English language test for higher education and immigration.

In 2019, over 508,000 international students came to study in the UK, making it the world’s most popular UK ELT (English Language Test) destination.

Over half (54%) of those students were under 18 years old.

Though I have helped students prepare for an IELTS exam, I personally have never needed to take one as my mother tongue is English, but for Daly who is nevertheless trilingual in Arabic, French and English, a successful IELTS scoring might enhance his future.

Above: The word “Arabic” written in Arabic

The train hums along tracks that cut through landscapes of stillness.

The journey is punctuated by moments of quiet reflection.

We arrive at Ankara Main Station.

Ankara railway station (Ankara Garı) is the main railway station in Ankara and a major transportation hub within the city.

Above: Ankara Station logo

The Station is on the rail corridor which connects east and west Turkey, which is high speed between Istanbul and Sivas.

Above: Sivas

Ankara Station is also a hub for YHT high-speed trains, with its own exclusive platforms and concourse.

TCDD Taşımacılık also operates intercity train service to Kars, Tatvan and Kurtalan as well as Başkentray commuter rail service.

Above: Kars

Above: Tatvan

Above: Kurtalan

Above: An eastbound Ankara suburban train

Located within the historic Ulus quarter, the Station is a landmark of the city.

Above: Ankara Garı

In 2016, a new building was opened above the YHT platforms known as Ankara Tren Garı (ATG).

The ATG building serves as a hub for high-speed rail with its own concourse containing information and tickets booths, waiting rooms and a VIP lounge, and is connected to the rest of the station via a skybridge.

Above: Ankara Tren Garı

As we drink coffee at the Caribou Coffee Café above the street entrance, we talk about work, as pigeons fling themselves suicidal dive bombing from balcony above to concrete floor below and perch atop wooden tables spilling unemptied cups and unwisely indulging a surprising caffeine habit.

Above: Caribou Coffee, Ankara Station

Above: Pigeons

We speak of what had gone wrong.

New hires come into a new organization.

They bring impressive backgrounds and lots of potential.

And yet, somehow we get off on the wrong foot.

Perhaps we never quite fit in with the company culture, rub key people the wrong way, make fatal misjudgments.

We try to remember the basics, to listen and learn about the new environment and yet a misstep and the job can suddenly end.

Dissent or mere disagreement can be viewed as disloyalty.

And at the end of the day a bad situation may simply a bad boss.

We can move on.

We must move on.

The question is how.

In the train concourse and along the streets heading to the nondescript testing centre, more pesky pigeons careen dangerously close to our path — seemingly indifferent to the notion of self-preservation.

They are creatures either oblivious to or defiant of the machinery that thunders through their domain.

I wonder if they feel like they belong here.

I wonder if they are reacting to us because they feel we don’t belong here.

Annie Lennox croons in my mind:

“Dying is easy.

It’s living that scares me to death.“

I look at Ankara once again and I cannot imagine ever wanting to live here.

Above: Kızılay Square and Emek Business Center (1959 – 1965), the first International Style office tower and shopping center in Turkey

Serving as the capital of the ancient Celtic state of Galatia, from whence came the Galatians (280 – 64 BC), and later of the Roman province with the same name (25 BC–7th century), Ankara has various Hattian, Hittite, Lydian, Phrygian, Galatian, Greek, Persian, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman archaeological sites.

Ankara was historically known as Ancyra and Angora.

Above: The Dying Galatian was a famous statue commissioned between 230 and 220 BC by King Attalos I (269 – 197 BC) of Pergamon to honor his victory over the Celtic Galatians in Anatolia

Above: Hattian ewer (2000 – 1700 BC)

Above: Empire of the Hittites (1650 – 1180 BC)

Above: The Phrygian Kingdom (1200 – 675 BC)

Above: Winged Nike of Samothrace, Hellenistic period (323 – 30 BC)

Above: The Capitoline Wolf, symbol of the Roman Empire (753 BC – AD 476)

Above: The Byzantine Empire (476 – 1453) at its greatest extent

Above: Flag of the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922)

The Ottomans made the city the capital first of the Anatolia Eyalet (1393 – late 15th century) and then the Angora Eyalet (1827–1864) and the Angora Vilayet (1867 – 1922).

Above: (in red) Anatolia Eyalet (1393 – 1827)

Above: (in red) Angora Eyalet (1827 – 1864)

Above: Map of the Ankara Eyalet (1864 – 1922)

The historical center of Ankara is a rocky hill rising 150 m (500 ft) over the left bank of the Ankara River, a tributary of the Sakarya River.

Above: Ankara River and Akköprü at Yenimahalle

The hill remains crowned by the ruins of Ankara Castle.

Above: Ankara Castle

Although few of its outworks have survived, there are well-preserved examples of Roman and Ottoman architecture throughout the city, the most remarkable being the 20 BC Temple of Augustus and Rome that boasts the Monumentum Ancyranum, the inscription recording the Res Gestae Divi Augusti.

Above: Temple of Augustus and Rome, Ankara

On 23 April 1920, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey was established in Ankara, which became the headquarters of the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence.

Ankara became the new Turkish capital upon the establishment of the Republic on 29 October 1923, succeeding in this role as the former Turkish capital Istanbul following the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

The government is a prominent employer, but Ankara is also an important commercial and industrial city located at the center of Turkey’s road and railway networks.

Above: General Assembly Hall, Grand National Assembly of Turkey, Ankara

Ankara is the center of the state-owned and private Turkish defence and aerospace companies, where the industrial plants and headquarters of the Turkish aerospace industries and numerous other firms are located.

Exports to foreign countries from these defense and aerospace firms have steadily increased in the past decades.

The International Defence Industry Fair (IDEF) in Ankara is one of the largest international expositions of the global arms industry.

A number of the global automotive companies also have production facilities in Ankara, such as the German bus and truck manufacturer MAN SE.

Ankara hosts the OSTIM (Ortadoğu Sanayi ve Ticaret Merkezi) industrial zone, Türkiye’s largest industrial park.

Above: OSTIM panorama

A large percentage of the complicated employment in Ankara is provided by the state institutions, such as the ministries, sub-ministries, and other administrative bodies of the Turkish government.

There are also many foreign citizens working as diplomats or clerks in the embassies of their respective countries.

Above: (in green) Türkiye

The city gave its name to the Angora wool shorn from Angora rabbits, the long-haired Angora goat (the source of mohair), and the Angora cat.

Above: Angora rabbit

Above: Angora goat

Above: Angora cat

The area is also known for its pears, honey and Muscat grapes.

Above: Ankara pears

Above: Ankara honey

Above: Ankara Muscat grapes

Although situated in one of the driest regions of Turkey and surrounded mostly by steppe vegetation (except for the forested areas on the southern periphery), Ankara can be considered a green city in terms of green areas per inhabitant, at 72 square meters (775 square feet) per head.

Above: Ankara

I have tried to like Ankara, but it reminds me more of what it isn’t or hasn’t more than what it is or has.

It is historic, but it is no Rome.

Above: Rome, Italy

It is a national capital, but it is no Washington DC.

Above: Washington DC, USA

It has ruined temples, but it is no Athens.

Above: Athens, Greece

It has a citadel, but it is no Edinburgh.

Above: Edinburgh, Scotland

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656 – 1708) was a French botanist, notable as the first to make a clear definition of the concept of genus for plants.

Tournefort was born in Aix-en-Provence and studied at the Jesuit convent there.

It was intended that he enter the Church, but the death of his father allowed him to follow his interest in botany.

After two years collecting, he studied medicine at Montpellier, but was appointed professor of botany at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris in 1683.

During this time he travelled through Western Europe, particularly the Pyrenees, where he made extensive collections.

Between 1700 and 1702 he travelled through the islands of Greece and visited Constantinople, the borders of the Black Sea, Armenia and Georgia, collecting plants and undertaking other types of observations.

He was accompanied by the German botanist Andreas Gundelsheimer (1668–1715), and the artist Claude Aubriet (1651–1742).

His description of this journey was published posthumously (Relation d’un voyage du Levant), he himself having been killed by a carriage in Paris; the road on which he died now bears his name (Rue de Tournefort in the 5ème arrondissement).

Botanist Charles Plumier (1646 – 1704) was his pupil and also accompanied him on his voyages.

Above: French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort visited the city in 1701 and pronounced it one of his favorites in all Asia.

Above: Tournefort’s research journeys

He writes:

“Angora delighted us more than any other city in the Levant.

We imagined the blood of those brave Gauls, who formerly possessed the country around Toulouse and between the Cevennes and the Pyrenees, still ran in the veins of the inhabitants of this place.

Those generous Gauls, confined in their own country too much for their courage, set out to the number of 30,000 men to go and make conquests in the Levant under the conduct of many commanders.

While General Brennus ravaged Greece and plundered the temple of Delphos of its immense riches, 20,000 of this army marched into Thrace with Leonorius.

The Gauls spread terror all over Asia, as we learn from Livy.

The Roman Emperor Augustus did, no doubt, beautify Angora and it was probably in acknowledgment that the inhabitants consecrated the city to him.“

This temple of Rome and Augustus had first been observed by the French scholar Laisné late in 1670.

He would not trouble to copy the remains of the inscription, so damaged by “time and the barbarism of the Turks“, but Tournefort made a copy.

The published text is one of our most valuable sources for the history of Augustus’ reign.

With the growing instability on the decline of Roman power, Angora changed rulers many times:

“The situation of Angora in the middle of Asia has frequently exposed it to great ravages.

It was taken by the Persians in 611, in the time of Heraclius, and ruined in 1101 by that dreadful army of Normans.

Above: Route of the Crusade of 1101

The Tartars made themselves masters of Angora in 1239.

It was afterwards the chief seat of the Ottomans.”

Above: Ottoman houses in Hamamönü district, Ankara

When Bayezid became Ottoman Sultan his power was such that even the Emperor of Byzantine had to fall at his feet.

Above: Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I (or Bajazet) (1360 – 1403)

To preserve the peace the Byzantine Emperor Manual II Palaeologus had to present himself as a vassal in December 1391 at Bayezid’s court, where he was received with all the supercilious indifference that was to become familiar to later visitors to the Ottoman court.

His letter to the Sultan is pitiful:

“How is it possible that I should be in want, I who, for a long time now, have been leading such a great army into a strange land in winter – though many call the land a friendly one?

Add to this the shortage of victuals and the need to buy these at great expense, which has absorbed all of our attention, as in the enemy territory we have used up all the supplies we brought with us from home.

How will my comrades feel, who are familiar neither with the customs nor the language nor the religion, and in a well-governed city can hardly buy the remnants of the goods on sale in the market, where indeed they must virtually fight with you, if by brute force they are to snatch something from the hands of the second-hand goods merchants?

Consider in addition the haughtiness, the contempt of those who hold the highest ranks next to the Sultan, the greed, the insatiability, the readiness to demand, the savage nature, the mutual envy, the anger of each one of them against the foreigners, the hatred, if they should not leave them their possessions and return home denuded of everything.

This too must not be passed over: the daily hunt, the succeeding immoderation at table, the swarms of actors, the groups of flautists, the choruses of singers, the masses of dancers, the noise of cymbals, the rowdy laughter that follows the drinking of water – does it not mean that those who make such behavior their constant companion, are indeed stupid?

It is only circumstances which compel us to undertake such a difficult task, enveloped though we are in so much misfortune. It is the result of your and your sons’ valorous pride.

For I do not see you going directly from the midday meal to the evening meal (like those who are considered happy among you) and from this to sleep and then again to the midday meal in a perpetual cycle, so that their life consists of sloth and excess, in no way becoming to men.

Oh, that this evil connection could be broken!

But everything that breaks it is “of no value“, that is, nothing that is better and more honorable, but only the opposite.

If, then, your wisdom, understanding and humility did not give me courage to speak, you may be sure that I should give up the task at once.“

Manuel Paleologus, Letters

Above: Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (1350 – 1425)

Those tales of luxury are corroborated by the Greek historians.

It was that hedonism that proved Bayezid’s downfall, as Tournefort relates:

“Angora was fatal to the Ottoman and the battle which Tamerlane (or Timur) obtained there over Bajazet, had well nigh destroyed their empire.

Bajazet, the haughtiest man in the world, too confident in himself, left his camp to go a-hunting.

Tamerlane, whose troops began to want water, laid hold on this opportunity and rendering himself master of the small river which ran between the two armies, three days after forced Bajazet to give him battle, to prevent his army from dying of thirst.

His army was cut to pieces and the Sultan taken prisoner on 7 August 1401.“

J. P. de Tournefort

Above: Mongol conqueror Tamerlane (Timur) (1320 – 1405)

Gibbon’s account of the Battle of Angora is vivid and the tale inspired Marlowe too.

Above: Battle of Ankara, 28 July 1402

“Firm in his plan of fighting in the heart of the Ottoman Kingdom, he avoided their camp, dexterously inclined to the left, occuped Caesarea (Kayseri), traversed the salt desert and the river Halys, and invested Angora, while the Sultan, immoveable and ignorant in his post, compared the Tartar swiftness to the crawling of a snail.

He returned on the wings of indignation to the relief of Angora, and, as both generals were alike impatient for action, the plans round that city were the scene of a memorable battle, which has immortalized the glory of Timor and the shame of Bajazet.

For this signal victory, the Mogul Emperor was indebted to himself, to the genius of the moment and the discipline of 30 years.

He had improved the tactics without violating the manners of his nation, whose force still consisted in the missile weapons and rapid evolutions of a numerous cavalry.

From a single troop to a great army, the mode of attack was the same:

A foremost line first advanced to the charge and was supported by a just order by the squadrons of the great vanguard.

The general’s eye watched over the field and at his command the front and rear of the right and left wings successively moved forwards in their several divisions and in a direct or oblique line.

The enemy was pressed by 18 or 20 attacks and each attack afforded a chance of victory.

If they all proved fruitless or unsuccessful, the occasion was worthy of the Emperor himself, who gave the signal of advancing to the standard and main body, which he led in person.

But in the Battle of Angora, the main body itself was supported, on its flanks and in the rear, by the bravest squadrons of the reserve, commanded by the sons and grandsons of Timor.

The conqueror of Hindustan ostentatiously showed a line of elephants, the trophies rather than the instruments of victory.

The use of the Greek fire was familiar to the Moguls and Ottomans, but had they borrowed from Europe the recent invention of gunpowder and cannon, the artificial thunder in the hands of either nation must have turned the fortune of the day.

On that day, Bajazet displayed the qualities of a soldier and a chief, but his genius sunk under a stronger attendant and from various motives the greatest parts of his troops failed him at the decisive moment.“

Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Above: English historian Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794)

Bajazeth:

“Now shall you feel the force of Turkish arms, which lately made all Europe quake for fear.

I have of Turks, Arabians, Moors and Jews enough to cover all Bithynia.

Let thousands die.

Their slaughtered carcasses shall serve for walls and bulwarks to the rest.

And as the heads of Hydra, so my power subdued shall stand as mighty as before.

If they should yield their necks unto the sword, your soldiers’ arms could not endure to strike so many blows as I have heads for you.

You know it not, foolhardy Tamburlaine, what it is to meet me in the open field that leaves no ground for you to march upon.”

Tamburlaine:

“Our conquering swords shall marshal us the way we use to march upon the slaughtered foe, trampling their bowels with our horses’ hoofs, brave horses bred on the white Tartarian hills.

My camp is like to Julıus Caesar’s host that never fought but had the victory.

Not in Pharsalia was there such hot war as these my followers willingly would have.

Legions of spirits, fleeting in the air, direct our bullets and our weapons’ points and make your strokes to wound the senseless air.

And when she sees our bloody colors spread, then Victory begins to take her flight, resting herself upon my milk-white tent.

But come, my lords, to weapons let us fall.

The field is ours, the Turk, his wife and all.“

Bajazeth:

“Come, kings and bassoes, let us glut our swords, that thirst to drink the feeble Persians’ blood.“

But later:

Bajazeth:

“Great Tamburlaine, great in my overthrow, ambitious pride shall make you fall as low, for treading on the back of Bajazeth, that should be horsed on four mighty kings.“

Tamburlaine:

“Your names and titles and your dignities are fled from Bajazeth and remain with me, that will maintain it against a world of kings.

Put him in again.“

Bajazeth is thrown into a cage.

Bajazeth:

“Is this a place for mighty Bajazeth?

Confusion light on him that helps you thus.“

Tamburlaine:

“There, while he lives, shall Bajazeth be kept, and, where I go, be thus in triumph drawn.

And you, his wife, shall feed him with the scraps my servants shall bring you from my board, for he that gives him other food than this shall sit by him and starve to death himself.

This is my mind and I will have it so.

Not all the kings and emperors of the Earth, if they would lay their crowns before my feet, shall ransom him or take him from his cage.

The ages shall talk of Tamburlaine, even from this day to Pluto’s wondrous year, shall talk how I have handled Bajazeth.

These Moors that drew him from Bithynia to fair Damascus where we now remain shall lead him wheresoever we go.

Techelles and my loving followers, now may we see Damascus’ lofty towers like to the shadows of the Pyramids that with their beauties graced the Memphis fields, that spreads her wings upon the city walls, shall not defend it from our battering shot.

The townsmen mask in silk and cloth of gold and every house is as a treasury.

The men, the treasure and the town are ours.“

Christopher Marlowe, Tamburlaine

Above: English dramatist Christopher Marlowe (1564 – 1593)

The historian Gibbon is more skeptical of this memorable piece of cruelty:

“The iron cage in which Bajazet was imprisoned by Tamerlane, so long and so often repeated as a moral lesson, is now rejected as a fable by modern writers who smile at the vulgar credulity.

They appeal with confidence to the Persian history of Sherefeddin Ali, which has been given to our curiosity in a French version and from which I shall collect and abridge a more specious narrative of this memorable transaction.

No sooner was Timor informed that the captive Ottoman was at the door of his tent than he graciously stepped forwards to receive him, seated him by his side and mingled with just reproaches a soothing pity for his rank and misfortune.

“Alas!“, said the Emperor.

“The decree of fate is now accomplished by your own fault.

It is the web which you have woven, the thorns of the tree which yourself have planted.

I wished to spare and even to assist the champion of the Muslims.

You braved our threats.

You despised our friendship.

You forced us to enter your Kingdom with our invincible armies. Behold the event.

Had you vanquished, I am not ignorant of the fate which you reserved for myself and my troops, but I disdain to retaliate.

Your life and honor are secure and I shall express my gratitude to God by my clemency to man.“

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Above: Battle of Ankara

By 1701, things had quieted down a bit in Angora.

“Angora, at present, is one of the best cities in Anatolia.

Everywhere shows marks of its ancient magnificence.

One sees nothing in the streets but pillars and old marbles.

The walls of the city are low and furnished with very sorry battlements.

They have indifferently made use of pillars, architraves, capitals, bases and other ancient pieces, intermingled with masonry, to build the wall, especially in the towers and gates, which nevertheless are not at all the more beautiful.

For the towers are square and the gates plain.

They breed the finest goats in the world in the champaign of Angora.

They are of a dazzling white and their hair, which is as fine as silk, naturally curled in locks of eight or nine inches long, is worked up into the finest stuffs, especially camlet, but they don’t suffer these fleeces to be exported unspun, because the country people gain their livelihood thereby.“

J. P. de Tournefort

Above: Illustration of Ankara, J. P. de Tournefort

Tournefort duly provided an illustration of one of those famous goats, which should have attracted the attention of other writers.

Above: Angora goat, J. P. Tournefort

Yes, Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and, as such, should be a little special.

However, as with many capital cities, the prime role is to cater for the bureaucracy of running a country,

This can and does cause many capital cities to be a bit soulless.

Ankara is a city that no one much writes about as a tourist destination.

Ankara presents itself at first glance as an austere concrete jungle – dry and sterile.

Above: Ankara

The historical Old Quarter is real Ankara, real people walking around, pottering in their gardens and smiling and waving.

This is where the men are drinking coffee at cafes, and there are spice markets.

The streets are tight:

Cobble-stoned and at times steep and winding to reveal more of life.

Watch school kids be typical kids mucking around in the playground.

This is where I feel much more comfortable and at ease in a place with some soul and a lot of warmth.

This is where people make handmade shoes that are stunningly crafted and beautiful.

This is where food is homemade and excellent.

This is where you keep finding things that you didn’t expect.

There are stacks of crowded little shops.

Above: Old Ankara

Ankara has an underbelly.

This is good and not so good.

The good is that there is a lively arts and music scene.

The bad is the proliferation of brothels in the city, where men are allotted seven minutes to a Natasha, a prostitute bought in from Russia.

They are all called Natasha.

Apparently one of the wealthiest women in Turkey was a brothel owner from Ankara.

There are queues around the corners to get the seven-minute service, at many venues all over the city, day and night.

Or so it is said.

Even Daly from distant Tunisia, though today is his first time here, has heard the rumors.

There are also queues of unemployed men waiting to get some day work.

At times, it is hard to tell which queue they are in.

Or so it is said.

Ankara defies description so few writers have bothered with it.

Sabahattin Ali’s Madonna in a Fur Coat opens and ends in Ankara though the tragic love story revolves around Berlin and Prague.

The story takes place in Ankara in the 1930s.

The narrator is going through hard times of unemployment and poverty.

With the help of a former friend, he finds a job as a clerk in a firm.

There, he shares his office with an ordinary looking man, Raif, who he calls:

“The sort of man who causes us to ask ourselves:

‘What do they live for?

What do they find in life?

What logic compels them to keep breathing?‘”

As they keep working together, they form a friendship.

One day, the narrator finds out that Raif has fallen sick and decides to visit him.

As they talk, Raif asks his friend to destroy a notebook that is hidden in a drawer.

The narrator picks up the notebook, reads a few sentences and asks Raif if he can borrow it for a day.

Raif allows him to keep the notebook, but says he must destroy it after reading.

The narrator walks to his home and starts reading the notebook.

The narrator meets a younger Raif as he reads the notebook.

On his deathbed, Raif is dying with guilt.

The next day, the narrator goes to Raif’s house to give back the notebook and talk, but Raif has died.

The narrator goes to their office, sits on Raif’s desk and reads the notebook once again.

As I walk the streets trying to locate the bookshops that my Eskişehir friend Hakan recommended, I find myself asking of those in Ankara I meet:

“What do they live for?

What do they find in life?

What logic compels them to keep breathing?

Why have they decided to call Ankara “home“?”

The Turkish State Opera and Ballet, the national directorate of opera and ballet companies of Turkey, has its headquarters in Ankara, and serves the city with three venues.

Above: Ankara State Opera

Ankara is host to five classical music orchestras and four concert halls and also has a number of concert venues, which host the live performances and events of popular musicians.

The Turkish State Theatres also has its head office in Ankara and runs ten stages in the city.

Above: The head office of Turkish State Theatres, Ankara

In addition, the city is served by several private theater companies.

Above: Logo of the Ankara Art Theatre

There are about 50 museums in the city.

I have been to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Anıtkabir, the Ankara Ethnography Museum, and the Ankara Citadel.

I would like to visit the Mehmet Akif Literature Museum Library, an important literary museum and archive opened in 2011 and dedicated to Mehmet Akif Ersoy (1873 – 1936), the poet of the Turkish National Anthem.

Above: Mehmet Akif Literature Museum Library, Ankara

Widely regarded as one of the premiere literary minds of his time, Ersoy is noted for his command of the Turkish language, as well as his patriotism and role in the Turkish War of Independence.

Above: Mehmet Akif

A framed version of the national anthem by Ersoy typically occupies the wall above the blackboard in the classrooms of every public as well as most private schools around Turkey, along with a Turkish flag, a photograph of the country’s founding father Atatürk, and a copy of Atatürk’s speech to the nation’s youth.

Above: Reverse of the 100 lira banknote (1983–1989)

As with all other cities of Turkey, football is the most popular sport in Ankara.

Above: Ankara Arena

Here one can also find facilities, whether voyeur or participant, for basketball, volleyball, ice skating, ice hockey, skateboarding and handball.

Above: Logo of the Turkish Men’s Volleyball League

Above: BelPa Ice Skating Facility, Ankara

Above: THF Sport Hall, Ankara

Ankara has many parks and open spaces mainly established in the early years of the Republic and well maintained and expanded thereafter.

Above: Seğmenler Park, Ankara

Ankara is noted, within Turkey, for the multitude of universities it is home to.

I stopped counting once I reached the number 18.

Above: Logo of Ankara University

I could feel at home here, I suppose, if I tried.

Home is where we are free to be ourselves.

But what of those who have never truly had that freedom?

The books I acquire at Sanat Bookshop seem to whisper reflections of this question.

Above: Sanat Bookshop, Ankara

Ezra Pound, exiled for his politics.

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (1885 – 1972) was an American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a collaborator in Fascist Italy and the Salò Republic during World War II.

Above: Ezra Pound

His works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his 800-page epic poem The Cantos (1917 – 1962).

Pound’s contribution to poetry began in the early 20th century with his role in developing Imagism, a movement stressing precision and economy of language.

Working in London as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, he helped discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as:

- H. D.

Above: American poet Hilda Doolittle (aka H. D.)(1886 – 1961)

- Robert Frost

Above: American poet Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

- T. S. Eliot

Above: American-born English poet Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888 – 1965)

- Ernest Hemingway

Above: American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961)

- James Joyce

Above: Irish writer James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Pound was responsible for the 1914 serialization of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the 1915 publication of Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock“, and the serialization from 1918 of Joyce’s Ulysses.

Hemingway wrote in 1932 that, for poets born in the late 19th or early 20th century, not to be influenced by Pound would be “like passing through a great blizzard and not feeling its cold“.

Angered by the carnage of World War I, Pound blamed the war on finance capitalism, which he called “usury“.

Above: Scene from World War I (1914 – 1918)

He moved to Italy in 1924 and through the 1930s and 1940s promoted an economic theory known as social credit, wrote for publications owned by the British fascist Sir Oswald Mosley, embraced Benito Mussolini’s fascism, and expressed support for Adolf Hitler.

Above: British politician Oswald Mosley (1896 – 1980)

Above: Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

Above: German dictator Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945)

During World War II, Pound recorded hundreds of paid radio propaganda broadcasts for the fascist Italian government and its later incarnation as a German puppet state, in which he attacked the United States federal government, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Great Britain, international finance, munitions makers, arms dealers, Jews, and others, as abettors and prolongers of the war.

Above: Ezra Pound

Above: Flag of Italy (1861 – 1946)

Above: Coat of arms of the United States of America

Above: US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945)

Above: Star of David, symbol of Judaism

Pound also praised both eugenics and the Holocaust in Italy, while urging American GIs to throw down their rifles and surrender.

Above: A 1930 exhibit by the Eugenics Society.

Some of the signs read “Healthy and Unhealthy Families“, “Heredity as the Basis of Efficiency” and “Marry Wisely“

In 1945, Pound was captured by the Italian Resistance and handed over to the US Army’s Counterintelligence Corps, who held him pending extradition and prosecution based on an indictment for treason.

Above: Flag of the Italian Committee of National Liberation (CLN)(1943 – 1947)

Pound spent months in a US military detention camp near Pisa, including three weeks in an outdoor steel cage.

Above: Pisa, Italy

Ruled mentally unfit to stand trial, Pound was incarcerated for over 12 years at St. Elizabeths Psychiatric Hospital in Washington, D.C., whose doctors viewed Pound as a narcissist and a psychopath, but otherwise completely sane.

Above: Saint Elizabeths, Washington DC

While in custody in Italy, Pound began work on sections of The Cantos, which were published as The Pisan Cantos (1948), for which he was awarded the Bollingen Prize for Poetry in 1949 by the Library of Congress, causing enormous controversy.

After a campaign by his fellow writers, he was released from St. Elizabeth’s in 1958 and returned to Italy, where he posed for the press giving the Fascist salute and called America “an insane asylum“.

Above: The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louıs David (1784)

Pound remained in Italy until his death in 1972.

Above: Flag of Italy

His economic and political views have ensured that his life and literary legacy remain highly controversial.

Ezra Pound, ever the modernist and exile, would have had a complicated relationship with the idea of home.

For Pound, “home” was never just a physical place but an intellectual and cultural belonging.

His life was one of perpetual movement — born in Idaho, educated in the US, but making his literary home in London, Paris, and eventually Italy.

Above: Homer Pound House, Hailey, Idaho – birthplace of Ezra Pound

Pound saw himself as a citizen of artistic tradition rather than any one nation.

Given his belief in the “permanent values” of art and history, he might argue that home exists wherever those values are nurtured and respected.

He championed the idea that true belonging comes from being understood and from contributing to something greater than oneself — whether that be an artistic movement, a literary lineage, or a place where one’s ideas can take root.

At the same time, Pound was obsessed with exile.

His own experiences — especially his controversial political views and eventual imprisonment — left him both physically and ideologically homeless.

The isolation he felt, particularly in his later years in St. Elizabeths Hospital, could speak to a darker theme:

What happens when the world does not allow one to exist freely?

Pound might have rewritten my earlier statement about home as:

“Home is not just where we live.

It is where our voices are heard and our visions are allowed to take shape.”

Ezra Pound’s poetry is deeply infused with the idea of home as something beyond a physical dwelling — a place of cultural, intellectual, and artistic belonging.

His works often reflect both a longing for a true home and the alienation of exile.

Pound believed that true belonging came not from geography but from cultural and intellectual tradition.

His epic poem, The Cantos, is a sprawling work that weaves together classical, Renaissance and Eastern influences, attempting to create a kind of artistic “home” in tradition itself.

In Canto I, he reworks Homer’s Odyssey, casting himself as Odysseus — a wanderer seeking a place of return.

This suggests that home is not just a place but a pursuit, a process of finding where one’s mind and spirit can thrive.

His translation work, particularly Cathay, shows his reverence for poetic lineage.

He was at home in words and ideas, borrowing from ancient Chinese poetry and Provençal troubadours.

For Pound, home was where literature and history allowed one to exist meaningfully.

Despite his attempts to create an intellectual home, much of Pound’s work expresses the pain of exile — both literal and figurative.

His political entanglements and imprisonment made him an outcast, and his later Pisan Cantos (written while detained in an open-air prison in Italy) are perhaps his most poignant reflections on isolation.

Above: The Leaning Tower of Pisa

In Canto LXXIV, he describes his time in the US military prison:

“And the days are not full enough / And the nights are not full enough / And life slips by like a field mouse / Not shaking the grass.“

Here, home is absent — not just physically but emotionally.

He is a man without a place, his existence reduced to mere survival.

Canto LXXXI contains the famous lines:

“What thou lovest well remains, the rest is dross / What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee.“

This suggests that home, as a place where one is allowed to exist, might not be a location but rather the things we hold onto — our passions, our art, our deeply felt truths.

Above: Ezra Pound

Pound’s fascination with Confucian ideals suggests he saw home as a place where order, beauty and justice prevail.

He longed for a world where people could exist meaningfully within a well-structured society — one reason he was drawn to the economic and political philosophies that led to his downfall.

In his translations of Confucius, he emphasizes the idea that home is where one’s virtue is recognized:

“A man’s home is the place where he is honored.”

Above: Chinese philosopher Confucius (551 – 479 BC)

Home is not just shelter, but a space where one’s existence is affirmed.

Pound’s poetry reflects the tension between the intellectual home he sought, the physical home he lost, and the cultural home he tried to build.

He might say that home is where one’s ideas are given space to grow — yet his own life proved how fragile that can be when society rejects the thinker.

Above: Ezra Pound

Harry Sinclair Lewis (1885 – 1951) was an American novelist, short story writer, and playwright.

Above: Sinclair Lewis

In 1930, he became the first author from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded “for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters“.

Lewis wrote six popular novels:

- Main Street (1920)

- Babbitt (1922)

- Arrowsmith (1925)

- Elmer Gantry (1927)

- Dodsworth (1929)

- It Can’t Happen Here (1935).

Several of his notable works were critical of American capitalism and materialism during the interwar period.

Lewis is respected for his strong characterizations of modern working women.

H. L. Mencken wrote of him:

“If there was ever a novelist among us with an authentic call to the trade, it is this red-haired tornado from the Minnesota wilds.“

Above: Flag of the US state of Minnesota

Sinclair Lewis, whose It Can’t Happen Here warns of freedom lost under the guise of security.

Sinclair Lewis, the sharp-eyed critic of American society, would likely approach the theme of home with a mix of irony and social realism.

His novels repeatedly challenge the idea that “home” is necessarily a place of belonging, instead portraying it as a battleground of conformity versus individuality.

Lewis often depicted home as a stifling, conformist space rather than a place where people are “allowed to exist“ as their true selves.

In Babbitt (1922), George F. Babbitt is a real estate salesman living in the fictional Midwestern city of Zenith.

His home and community embody material success, yet they leave him emotionally and spiritually empty.

Home, for Babbitt, is not where he is allowed to exist but where he is expected to conform.

His attempts at rebellion — flirting with liberal politics, having an affair, questioning societal norms — are met with disapproval, forcing him back into the mold of middle class respectability.

Lewis might argue that home, as understood by mainstream America, is a manufactured illusion, existing only for those willing to suppress their individuality.

For those who resist the pressures of society, home becomes a place of exile rather than belonging.

This is especially evident in Main Street (1920), where Carol Kennicott, a well-educated woman from the city, moves to the small town of Gopher Prairie after marrying a doctor.

Carol dreams of making her new home a place of culture and intellectual growth, but the town resents her efforts.

She gradually realizes that home, as defined by small-town America, does not include space for independent thought.

By the end, she returns, defeated but not entirely broken, accepting that true belonging might be impossible in such a rigid society.

While Lewis criticizes the false comforts of home, he doesn’t suggest that exile is the only answer.

Instead, his characters often search for a middle ground — a place where they can be true to themselves without complete alienation.

In Arrowsmith (1925), Dr. Martin Arrowsmith struggles with whether to pursue medical ideals or conform to a career in profit-driven medicine.

The novel suggests that a true “home” is found not in physical space but in work, purpose, and intellectual honesty — a place where one’s ideals can exist freely.

Through Lewis’ lens:

“Home is not just where we live.

It is where we are tolerated — until we refuse to conform.”

Gibran Khalil Gibran (1883 – 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran, was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist.

He was also considered a philosopher, although he himself rejected the title.

Above: Kahlil Gibran

He is best known as the author of The Prophet, which was first published in the United States in 1923 and has since become one of the best-selling books of all time, having been translated into more than 100 languages.

Born in Bsharri, a village of the Ottoman-ruled Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate to a Maronite Christian family, young Gibran immigrated with his mother and siblings to the United States in 1895.

Above: Bsharri, Lebanon

As his mother worked as a seamstress, he was enrolled at a school in Boston, where his creative abilities were quickly noticed by a teacher who presented him to photographer and publisher F. Holland Day.

Above: F. Holland Day (1864 – 1933)

Gibran was sent back to his native land by his family at the age of 15 to enroll at the Collège de la Sagesse in Beirut.

Above: Beirut, Lebanon

Returning to Boston upon his youngest sister’s death in 1902, he lost his older half-brother and his mother the following year, seemingly relying afterwards on his remaining sister’s income from her work at a dressmaker’s shop for some time.

Above: Boston, Massachusetts, USA

In 1904, Gibran’s drawings were displayed for the first time at Day’s studio in Boston.

His first book in Arabic was published in 1905 in New York City.

Above: New York City, New York, USA

With the financial help of a newly met benefactress, Mary Haskell, Gibran studied art in Paris from 1908 to 1910.

Above: American educator Mary Haskell (1873 – 1964)

While there, he came in contact with Syrian political thinkers promoting rebellion in Ottoman Syria after the Young Turk Revolution.

Above: Declaration of the Young Turk Revolution in the Ottoman Empire, 3 – 24 July 1908

Some of Gibran’s writings, voicing the same ideas as well as anti-clericalism, would eventually be banned by the Ottoman authorities.

In 1911, Gibran settled in New York, where his first book in English, The Madman, was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1918, with writing of The Prophet or The Earth Gods also underway.

His visual artwork was shown at Montross Gallery in 1914 and at the galleries of M. Knoedler & Co. in 1917.

He had also been corresponding remarkably with May Ziadeh since 1912.

Above: Palestinian poet May Ziadeh (1886 – 1941)

In 1920, Gibran re-founded the Pen League with fellow Mahjari poets.

The Pen League was the first Arabic-language literary society in North America, formed initially by Nasib Arida and Abd al-Masih Haddad in 1915 and subsequently re-formed in 1920 by a larger group of Mahjari writers in New York led by Kahlil Gibran.

They had been working closely since 1911.

The League dissolved following Gibran’s death in 1931 and Mikhail Naimy’s return to Lebanon in 1932.

The primary goals of the Pen League were, in Naimy’s words as Secretary, “to lift Arabic literature from the quagmire of stagnation and imitation, and to infuse a new life into its veins so as to make of it an active force in the building up of the Arab nations“.

As Naimy expressed in the by-laws he drew up for the group:

The tendency to keep our language and literature within the narrow bounds of aping the ancients in form and substance is a most pernicious tendency.

If left unopposed, it will soon lead to decay and disintegration.

To imitate them is a deadly shame.

We must be true to ourselves if we would be true to our ancestors.”

Above: Four members of the Pen League in 1920.

Left to right: Nasib Arida (1887 – 1946), Kahlil Gibran, Abd al-Masih Haddad (1890 – 1963) and Mikhail Naimy (1889 – 1988)

By the time of his death at the age of 48 from cirrhosis and incipient tuberculosis in one lung, Gibran had achieved literary fame on “both sides of the Atlantic Ocean“.

The Prophet had already been translated into German and French.

His body was transferred to his birth village of Bsharri (in present-day Lebanon), to which he had bequeathed all future royalties on his books, and where a museum dedicated to his works now stands.

Above: Kahlil Gibran Museum, Bsharri, Lebanon

In the words of Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins, Gibran’s life was “often caught between Nietzschean rebellion, Blakean pantheism and Sufi mysticism“.

Above: German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

Above: English poet William Blake (1757 – 1827)

Above: Tomb of Sufi leader Abdul Qadir Jilani, Baghdad, Iraq

Gibran discussed different themes in his writings and explored diverse literary forms.

Salma Khadra Jayyusi has called him “the single most important influence on Arabic poetry and literature during the first half of the 20th century“.

Above: Palestinian writer Salma Jayyusi (1925 – 2023)

Gibran is still celebrated as a literary hero in Lebanon.

Above: Flag of Lebanon

At the same time, “most of Gibran’s paintings expressed his personal vision, incorporating spiritual and mythological symbolism“, with art critic Alice Raphael recognizing in the painter a classicist, whose work owed “more to the findings of Da Vinci than it did to any modern insurgent“.

His “prodigious body of work” has been described as “an artistic legacy to people of all nations“.

Above: Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

Kahlil Gibran, a voice of longing for a homeland both physical and spiritual.

Kahlil Gibran, the poet of the soul’s longing and the mystic’s vision, would embrace our theme with a deeply spiritual and philosophical perspective.

For Gibran, home was never just a place — it was the essence of belonging, love, and self-realization.

His works frequently depict exile and the search for a true home, making him a fitting voice for our theme.

Gibran, a Lebanese immigrant to the United States, understood home not as a fixed geographical space but as the sanctuary where one’s spirit is free to exist and grow.

In The Prophet (1923), his most famous work, the titular figure Almustafa has lived in a foreign land for years, longing to return to his “home” — not just a physical place, but a space where his soul is truly understood.

In the chapter “On Houses,” Gibran suggests that true home is not walls or possessions but something deeper:

“Your house shall not be an anchor but a mast.“

He implies that home should not confine us but give us the freedom to move and grow.

Almustafa’s departure from the city at the end of The Prophet reflects a deeper truth:

Home is not just where we live, but where our spirit finds peace.

Gibran’s personal life mirrored this struggle — born in Lebanon, he immigrated to America but never felt entirely at home in either place.

His writings reflect the sorrow of exile, a longing for a home that may never be fully regained.

In his poem “My People“, he mourns the suffering of his homeland:

“My people died of hunger, and he who did not perish from starvation was slain with the sword.“

Here, home is not just a place to live — it is a space where people should be allowed to exist without fear or suffering.

His essay “The Coming of the Ship” suggests that we are all wanderers searching for home, but that true belonging lies within, rather than in any external location.

For Gibran, the closest thing to a true home is found in love, human connection and self-fulfillment.

In The Prophet, he writes:

“Let there be spaces in your togetherness.“

This suggests that home is not about physical proximity but about being fully seen and accepted.

In Sand and Foam, he writes:

“You may house their bodies but not their souls.“

Home is not just a structure but a place where people are allowed to exist as their true selves.

Gibran would likely reframe our statement as:

“Home is not where we live, but where our souls are free to be.”

His vision of home transcends walls, nations, or even exile.

It is found in love, understanding and spiritual peace — a concept that deeply resonates with the human longing for belonging.

A theme emerges:

The fragility of home, the battle to preserve it, and the struggle of those who have none.

I prepare myself for the goal of writing about this day in history, 11 February.

Four names leap to my attention: Marie-Joseph Chénier, Else Lasker-Schüler, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Nelson Mandela.

Marie-Joseph Blaise de Chénier (11 February 1764 – 10 January 1811) was a French poet, dramatist and politician of French and Greek origin.

Above: Marie-Joseph Blaise de Chénier

The younger brother of André Chénier, Joseph Chénier was born at Constantinople (Istanbul), but brought up at Carcassonne.

Above: Carcassonne, France

He was educated in Paris at the Collège de Navarre.

Above: Collège de Navarre (1305 – 1805), Université de Paris, France

Entering the army at 17, he left it two years afterwards.

At 19 he produced Azémire, a two-act drama (acted in 1786), and Edgar, ou le page supposé, a comedy (acted in 1785), which both failed.

His Charles IX was kept back for nearly two years by the censor. Chénier attacked the censorship in three pamphlets.

Above: French King Charles IX (1550 – 1574)

The commotion aroused by the controversy raised keen interest in the piece.

When it was at last produced, on 4 November 1789, it was an immense success, due in part to its political suggestion, and in part to François Joseph Talma’s magnificent portrayal of King Charles IX of France.

Above: French actor François Joseph Talma (1763 – 1826)

Camille Desmoulins said that the piece had done more for the French Revolution than the days of October.

A contemporary memoir-writer, the Marquis de Ferrire, said that the audience came away “ivre de vengeance et du tourment d’un soir de sang“(“drunk with the vengeance and torment of an evening of blood“).

Above: French writer Camille Desmoulins (1760 – 1794)

The performance was the occasion of a split among the actors of the Comédie Française, and the new theatre in the Palais Royal, established by the dissidents, was inaugurated with Henri VIII (1791), generally recognized as Chénier’s masterpiece.

Jean Calas, ou l’école des juges (“Jean Calas, or the judges’ school“) followed in the same year.

In 1792 he produced his Caïus Gracchus, which was even more revolutionary in tone than its predecessors.

It was nevertheless proscribed in the next year at the instance of the Montagnard Deputy Albitte, for the anti-anarchical hemistich Des lois et non du sang (“Laws, and not blood“).

Fénelon (1793) was suspended after a few representations.

In 1794, Timoléon, set to Etienne Méhul’s music, was also proscribed.

This piece was played after the Reign of Terror, but the fratricide of Timoléon became the text for insinuations to the effect that by his silence Joseph Chénier had connived at the judicial murder of his brother, André, whom Joseph’s enemies alluded to as Abel.

Above: French poet André Chénier (1762 – 1794)

In fact, after some fruitless attempts to save his brother, variously related by his biographers, Joseph became aware that André’s only chance of safety lay in being forgotten by the authorities, and that ill-advised intervention would only hasten the end.

Joseph Chénier had been a member of the National Convention and had voted for the death of Louis XVI.

Above: French King Louis XVI (1754 – 1793)

Chénier belonged to the Committees of General Security, and of Public Safety (1793 – 1795).

Chénier was, nevertheless, suspected of moderate sentiments, and before the end of the Terror had become a marked man.

Above: Scene from the Reign of Terror (1792 – 1794)

Chénier had a seat in the Council of Five Hundred and the Tribunate.

Above: General Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821) surrounded by members of the Council of Five Hundred (1795 – 1799) during the 18 Brumaire coup d’état – 9 November 1799

In 1801, Chénier was one of the educational jury for the Seine départment.

Above: Coat of arms of the Seine départment

His political career ended in 1802, when he was eliminated with others from the Tribunate for his opposition to Napoleon Bonaparte.

Above: French Emperor Napoleon I (1769 – 1821)

From 1803 to 1806 Chénier was Inspector General of Public Instruction.

He had allowed himself to be reconciled with Napoleon’s government.

Cyrus, represented in 1804, was written in his honour, but he was temporarily disgraced in 1806 for his Épître à Voltaire.

In 1806 and 1807, Chénier delivered a course of lectures at the Athéne on the language and literature of France from the earliest years.

In 1808 at the Emperor’s request, he prepared his Tableau historique de l’état et du progrés de la littérature française depuis 1789 jusqu’à 1808 (“Historical view of the state and progress of French literature from 1789 to 1808“), a book containing some good criticism, though marred by the violent prejudices of its author.

The list of his works includes:

- hymns and national songs – among others, the famous Chant du départ

- odes

- Sur la mort de Mirabeau

Above: French writer Honoré Mirabeau (1749 – 1791)

- Sur l’oligarchie de Robespierre, etc.

Above: French statesman Maximilien Robespierre (1758 – 1794)

- tragedies which never reached the stage

- Brutus et Cassius

Above: Coinage of Roman politician / assassin Marcus Junius Brutus (85 – 42 BC)

Above: Bust of Roman senator/assassin Gaius Cassius Longinus (86 – 42 BC)

- Philippe deux

Above: Seal of French King Philippe II (1165 – 1223)

- Tibère

Above: Coinage of Roman Emperor Tiberius Augustus (42 BC – AD 37)

- translations from:

- Sophocles

Above: Mosaic of Greek tragedian Sophocles (497 – 405 BC)

- Lessing

Above: German philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781)

- Thomas Gray

Above: English poet Thomas Gray (1716 – 1771)

- Horace

Above: Medallion image of Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus (aka Horace) (65 – 8 BC)

- Tacitus

Above: Statue of Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (56 – 120)

- Aristotle

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

- elegies (dedications said for the dead)

- dithyrambics (Greek hymns honoring Greek god of wine Dionysus)

Above: Dionysus extending a drinking cup

- Ossianic rhapsodies

Above: Scottish orator Ossian Singing, Nicolai Abildgaard (1787)

As a satirist Chénier possessed great merit, though he sins from an excess of severity, and is sometimes malignant and unjust.

He is the chief tragic poet of the revolutionary period.

As Camille Desmoulins expressed it:

Above: French writer Camille Desmoulins (1760 – 1794)

“He decorated Melpomene with the tricolour cockade“.

Above: Melpomene, Greek Muse of tragedy

Marie-Joseph Chénier fought for a France where freedom could be home to all, but his ideals clashed with the tide of history, leaving him exiled from the very revolution he championed.

Marie-Joseph Chénier, the French playwright and poet of the revolutionary era, would likely interpret our theme through the lens of liberty, exile and the struggle for a just society.

Chénier lived through the turbulence of the French Revolution, and his works often reflected a belief that true “home” is not just a dwelling but a place where freedom and justice allow one to exist fully.

In Charles IX ou la Saint-Barthélemy (1789), his play about the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, Chénier exposes the brutality of tyranny and religious persecution.

For the persecuted Huguenots in the play, home is denied to them not because they lack houses, but because they are not allowed to exist freely within their own country.

Above: St. Bartolomew’s Day Massacre – 23–24 August 1572

The Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre (Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French Wars of Religion (1562 – 1598).

King Charles IX ordered the killing of a group of Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, and the slaughter spread throughout Paris.

Lasting several weeks in all, the massacre expanded outward to the countryside and other urban centres.

Modern estimates for the number of dead across France: 30,000.

This aligns with our theme — home is not just physical but a space of security, dignity and the right to be.

His revolutionary odes champion the idea that a nation must be a home for all its people, not just for the privileged.

His famous poem “L’Invention de la Liberté“ (The Invention of Liberty) suggests that without freedom, even one’s homeland can become a prison.

Like many revolutionaries, Chénier understood that one could be exiled even within one’s own land.

Above: Marie-Joseph Chénier

Chénier himself fell in and out of favor during the political upheaval of his time.

His brother, André, a poet and critic of Robespierre’s excesses, was executed during the Reign of Terror.

Marie-Joseph survived but understood that home can be lost when tyranny takes hold.

This reflects the idea that home is not merely a birthplace or a residence — it is a place where one’s voice and identity are allowed to exist.

Chénier’s works often celebrate revolution and justice as the foundations of a true home.

In his writings, he suggests that France itself can only be a true home when it allows all its people — not just the aristocracy — to exist freely.

His tragedies and poems depict home as an ideal to strive for, rather than a fixed place.

If injustice rules, home is no longer home — it must be fought for.

Home is not where we live, but where justice allows us to exist.

For him, home is a moral and political concept — a place where people are not just housed, but free.

He would view our theme through the revolutionary lens, emphasizing that when freedom is denied, home ceases to exist, even if one remains in their birthplace.

Above: Marie Joseph Chénier

Else Lasker-Schüler (née Elisabeth Schüler) (11 February 1869 – 22 January 1945) was a German poet and playwright famous for her bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and her poetry.

Above: Else Lacker-Schüler

She was one of the few women affiliated with the Expressionist movement.

Lasker-Schüler, who was Jewish, fled Nazi Germany and lived out the rest of her life in Jerusalem.

Above: Jerusalem, Israel

Schüler was born in Elberfeld, now a district of Wuppertal.

Above: Elberfeld, Wuppertal, Germany

Her mother, Jeannette Schüler (née Kissing) was a central figure in her poetry.

The main character of her play Die Wupper was inspired by her father, Aaron Schüler, a Jewish banker.

Her brother Paul died when she was 13.

Else was considered a child prodigy because she could read and write at the age of four.

From 1880 she attended the Lyceum West an der Aue.

After dropping out of school, she received private lessons at her parents’ home.

In 1894, Else married the physician and chess master Berthold Lasker and moved with him to Berlin, where she trained as an artist.

Above: German chess master brothers Emanuel (1868 – 1941) and Berthold Lasker (1860 – 1928)

On 27 July 1890 her mother died, her father followed 7 years later.

On 24 August 1899, her son Paul was born and her first poems were published.

She published her first full volume of poetry, Styx, three years later, in 1902.

On 11 April 1903, she and Berthold Lasker divorced.

On 30 November, she married Georg Lewin, artist, and founder of the Expressionist magazine Der Sturm.

His pseudonym, Herwarth Walden, was her invention.

Above: German artist Georg Lewin (aka Herwarth Walden)(1879 – 1941)

Lasker-Schüler’s first prose work, Das Peter Hille Buch, was published in 1906, after the death of Hille, one of her closest friends.

In 1907, she published the prose collection Die Nächte der Tino von Bagdad, followed by the play Die Wupper in 1909, which was not performed until later.

A volume of poetry called Meine Wunder, published in 1911, established Lasker-Schüler as the leading female representative of German Expressionism.

After separating from Herwarth Walden in 1910 and divorcing him in 1912, she found herself penniless and dependent on the financial support of her friends, in particular Karl Kraus.

Above: Austrian writer Karl Kraus (1874 – 1936)

In 1912, she met Gottfried Benn.

An intense friendship developed between them which found its literary outlet in a large number of love poems dedicated to him.

Above: German writer Gottfried Benn (1886 – 1956)

In May 1922, she attended the International Congress of Progressive Artists and signed the “Founding Proclamation of the Union of Progressive International Artists“.

The aim of creating an international organisation of radical artists led to differing conceptions of how this should be done.

Theo van Doesburg wrote “A short review of the proceedings” which included a proclamation calling for a permanent, universal, international exhibition of art from everywhere in the world and an annual universal, international music festival.

Above: Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg (1883 – 1931)

With the slogan “Artists of all nationalities unite” they declared that “Art must become international or it will perish.”

According to van Doesburg, when those who refused to sign this proclamation were threatened with exclusion, this led to uproar.

Above: Participants in the International Congress of Progressive Artists, Düsseldorf, 29 – 31 May 1922

(from left to right: unknown boy, Werner Graeff, Raoul Hausmann, Theo van Doesburg, Cornelis van Eesteren, Hans Richter, Nelly van Doesburg, De Pistoris, El Lissitzky, Ruggero Vasari, Otto Freundlich, Hannah Höch, Franz Seiwert and Stanislav Kubicki)

In 1927, the death of her son sent her into a deep depression.

Despite winning the Kleist Prize in 1932, as a Jew she was physically harassed and threatened by the Nazis.

Above: German writer Heinrich von Kleist (1777 – 1811)

She emigrated to Zürich but there, too, she could not work.

Above: Zürich, Switzerland

She subsequently went to British-ruled Palestine in 1934.

She finally settled in Jerusalem in 1937.

Above: British Mandatory Palestine (1920 – 1948)

In 1938 she was stripped of her German citizenship and the outbreak of World War II prevented any return to Europe.

Above: Scene from World War II (1939 – 1945)

According to her first Hebrew translator, Yehuda Amichai, she lived a life of poverty and the children in the neighborhood mocked her for her eccentric dress and behavior.

Above: Israeli writer Yehuda Amichai (1924 – 2000)

She formed a literary salon called “Kraal” which philosopher Martin Buber opened on 10 January 1942 at the French Cultural Center.

Above: Austrian philosopher Martin Buber (1878 – 1965)

Some leading Jewish writers and promising poets attended her literary programs, but Lasker-Schüler was eventually banned from giving readings and lectures because they were held in German.

She begged the head of the German synagogue in Jerusalem to let her use his Gotteshaus (‘house of God‘) one more time:

“Wherever I was, German is not allowed to be spoken.

I want to arrange the last Kraal evening for a poet who is already broken, to recite from his translations into German of a great Hebrew.”

In her final years, Lasker-Schüler worked on her drama IchundIch (IandI), which remained a fragment.

She finished her volume of poems, Mein Blaues Klavier (“my blue piano“)(1943), printed in a limited edition of 330 copies.

“Her literary farewell became her last attempt to overcome loneliness.

Significantly, she dedicated the work to “my unforgettable friends in the cities of Germany and to those, like me, exiled and dispersed throughout the world, in good faith.”

In one of her final acts, she asked that her hometown of Wuppertal and its surrounding area be spared from Allied bombing.

She tended to spend whatever money she had all at once which made her go for days without food or shelter.

Heinz Gerling, secretary of the Hitachdut Olei Germania (Association of Immigrants from Germany, later renamed to cover all of Central Europe) and the poet Manfred Sturmann came to her aid.

Gerling opened a bank account for her and arranged for regular payments to cover her expenses whereas Sturmann edited her work and helped with her dealings with publishers.

After her death, Sturmann became the trustee of her legacy and during the 1950s and 1960s dealt extensively with publishers in East and West Germany, Switzerland and Austria who wished to publish her works.

In 1944, Lasker-Schüler’s health deteriorated.

She suffered a heart attack on 16 January, and died in Jerusalem on 22 January 1945.

She was buried on the Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery.

Above: Grave of Else Lasker-Schüler

Lasker-Schüler left behind several volumes of poetry and three plays, as well as many short stories, essays and letters.

During her lifetime, her poems were published in various magazines, among them the journal Der Sturm edited by her second husband, and Karl Kraus’ literary journal Die Fackel.

She also published many anthologies of poetry, some of which she illustrated herself.

Examples are:

- Styx (1902)

- Der siebente Tag (1905)

- Meine Wunder (1911)

- Gesammelte Gedichte (1917)

- Mein blaues Klavier (1943)

Lasker-Schüler wrote her first and most important play, Die Wupper, in 1908.

It was published in 1909 and the first performance took place on 27 April 1919 at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin.

A large part of her work is composed of love poetry, but there are also deeply religious poems and prayers.

Transitions between the two are often quite fluid.

Her later work is particularly rich in biblical and oriental motifs.

Lasker-Schüler was very free with regard to the external rules of poetic form, however her works thereby achieve a greater inner concentration.

She was also not averse to linguistic neologisms.

A good example of her poetic art is her 1910 poem “Ein alter Tibetteppich“(“An old Tibetan rug“):

Your soul, which loveth mine,

Is woven with it into a Tibetan-rug.

Strand by strand, enamoured colours,

Stars that courted each other across the length of heavens.

Our feet rest on the treasure

Stitches-thousands-and-thousands-across.

Sweet lama-son on your musk-plant-throne

How long has your mouth been kissing mine,

And cheek to cheek colorfully woven times?

Else Lasker-Schüler, Jewish and defiant, was cast out of Germany, her poetry becoming the only home she had left.

Else Lasker-Schüler, the avant-garde poet and expressionist writer, would likely approach our theme with deep emotional intensity, blending themes of exile, identity, longing and spiritual belonging.