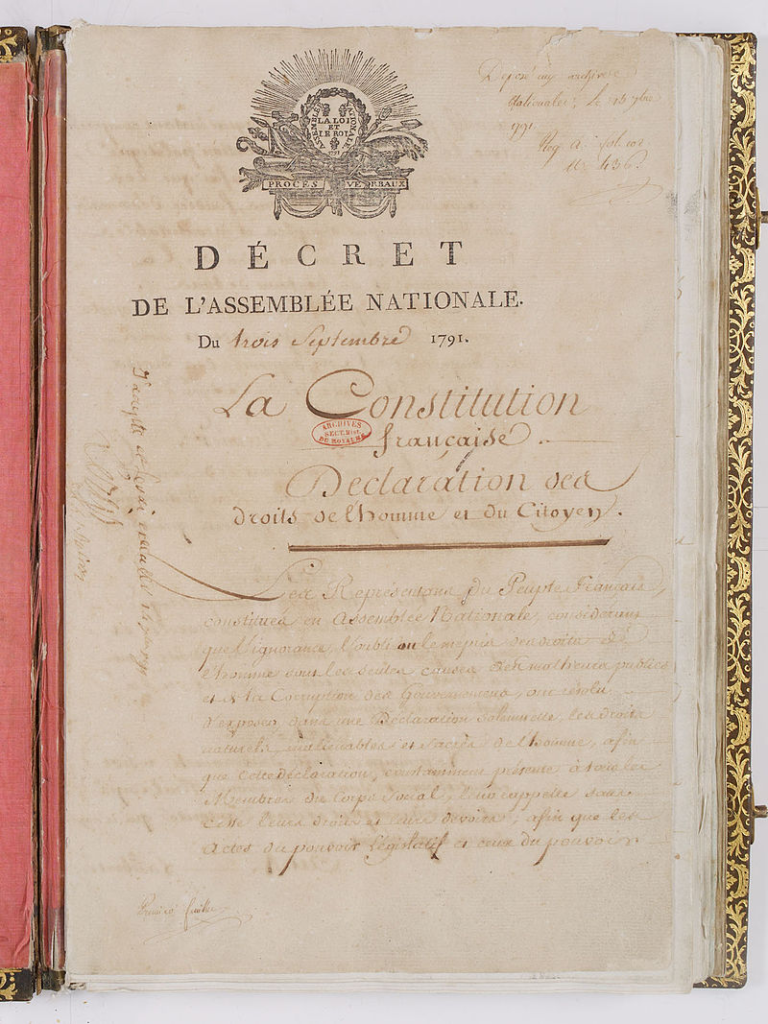

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 12 February 2025

We tell ourselves war ends when the treaties are signed, when the guns fall silent.

But for those who bear its scars, war is never truly over.

The fight continues — not on the battlefield, but in the struggle to heal, to be seen, to be whole again.

And in that battle, no one walks away untouched.

Above: The Bayeux Tapestry

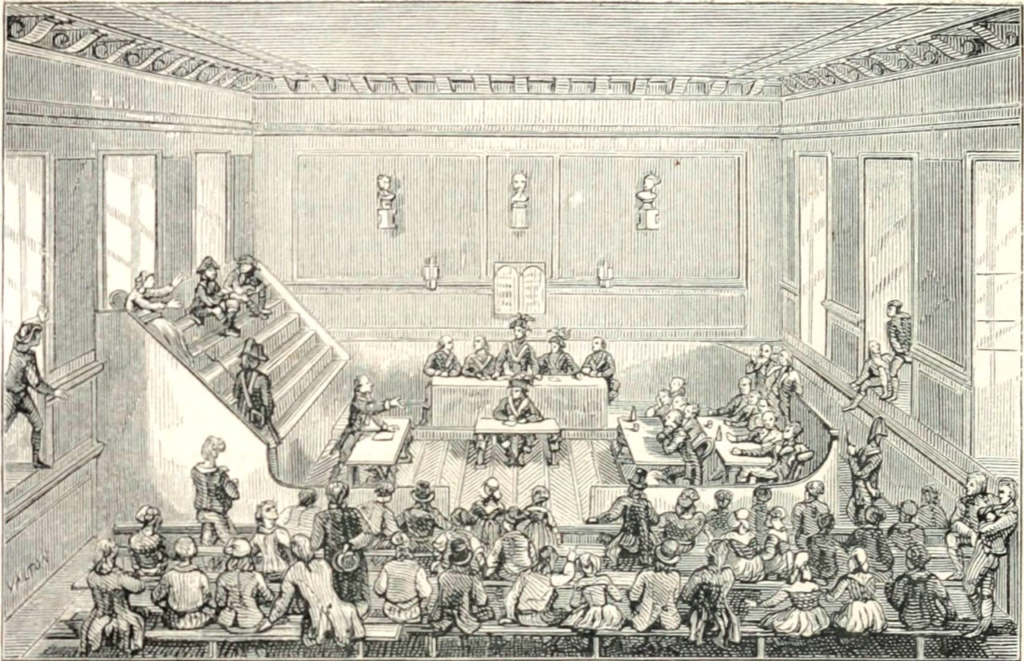

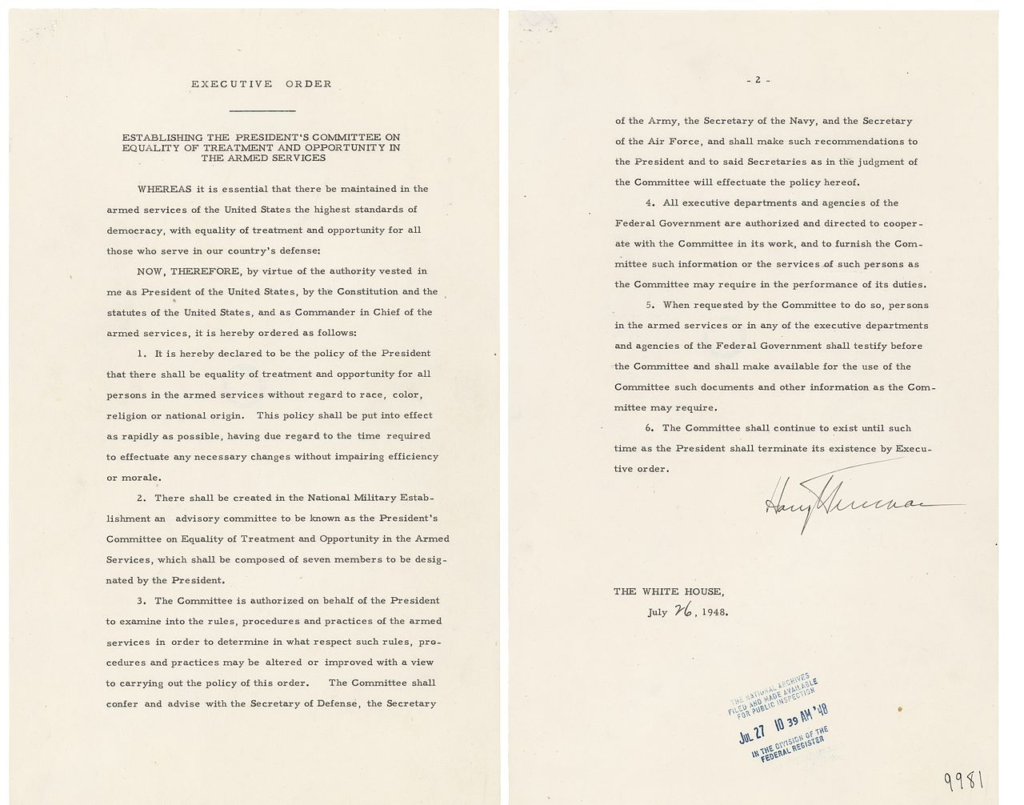

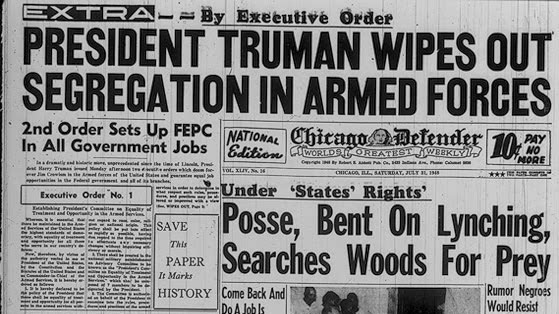

On February 12, 2025, a declaration is made – negotiations to end the Russo-Ukrainian War are set to begin immediately.

A world-weary sigh of relief follows.

Perhaps, at last, peace is within reach.

But is it?

Even if weapons are lowered, the war does not simply vanish.

Cities remain in ruins, families remain broken, and those who fought return home forever changed.

Peace may be a political agreement, but the battlefield lingers in the minds of those who endured its horrors.

President Donald Trump said negotiations to end the Ukraine war will start “immediately” after holding a “lengthy and highly productive” telephone call with Russian President Vladimir Putin on Wednesday morning.

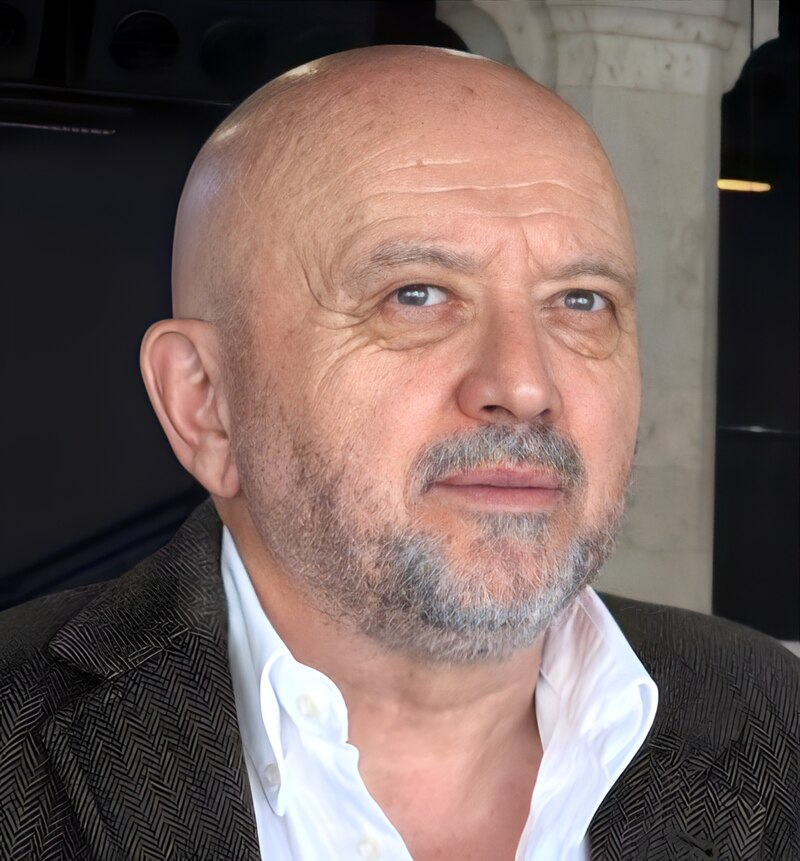

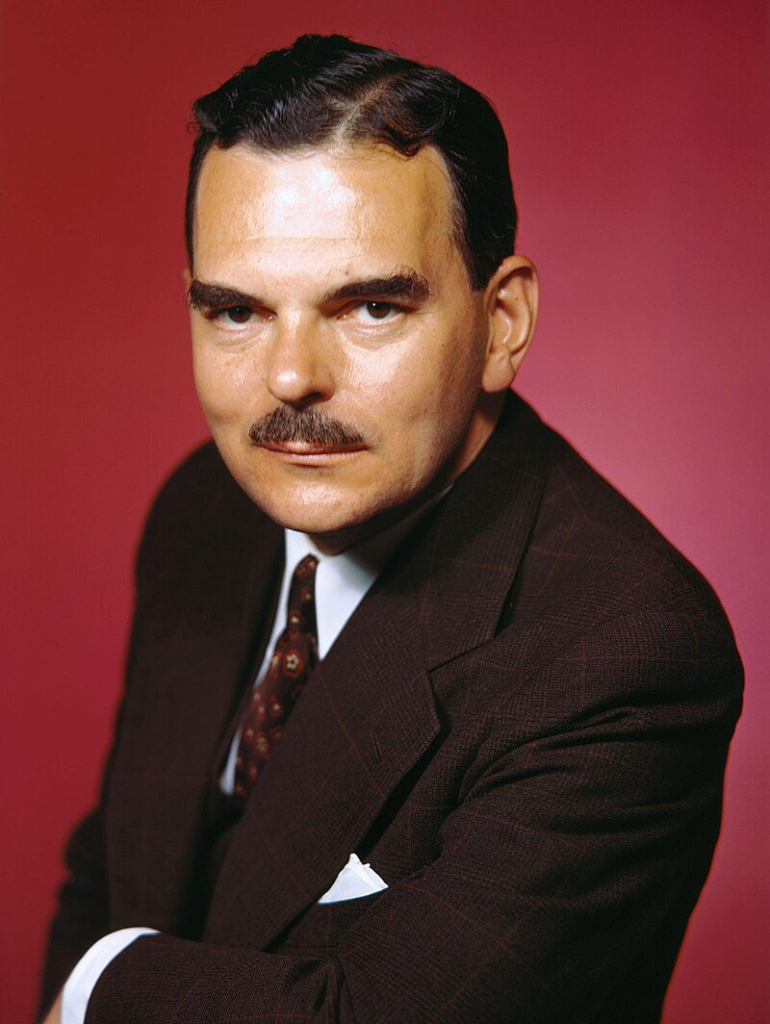

Above: US President Donald Trump

Above: Russian President Vladimir Putin

The call, which is the first known conversation between the Presidents since Trump assumed office last month, came as as Trump makes clear to his advisers he wants to bring the Ukraine conflict to a swift end.

Trump administration officials said they hoped a prisoner “exchange” on Tuesday could portend renewed efforts to end the war, which is about to enter its fourth year.

Above: Scene from Bridge of Spies (2015)

Now, as the two leaders resume communication after a long period of silence between the White House and the Kremlin, the contours of Trump’s settlement plan are coming into clearer focus.

Above: The White House, Washington DC, USA

Above: The Kremlin, Moscow, Russia

In a readout of the conversation posted on Truth Social, Trump said:

“We discussed Ukraine, the Middle East, energy, Artificial Intelligence, the power of the dollar, and various other subjects.

Above: Flag of Ukraine

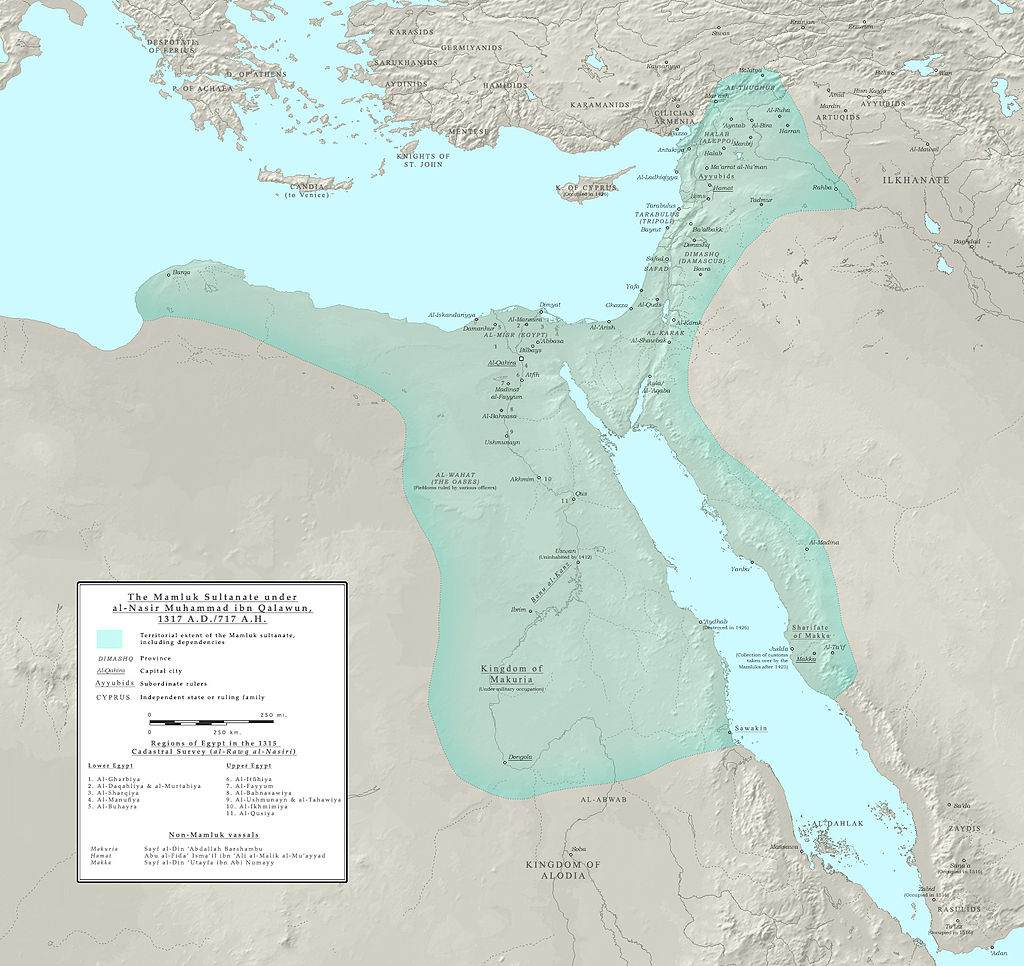

Above: (in green) The Middle East

“We agreed to work together, very closely, including visiting each other’s nations.

We have also agreed to have our respective teams start negotiations immediately.

We will begin by calling President Zelenskyy, of Ukraine, to inform him of the conversation, something which I will be doing right now,” Trump wrote.

Above: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy

Both Washington and Moscow, in their descriptions of the call, suggested the men assumed a conciliatory tone.

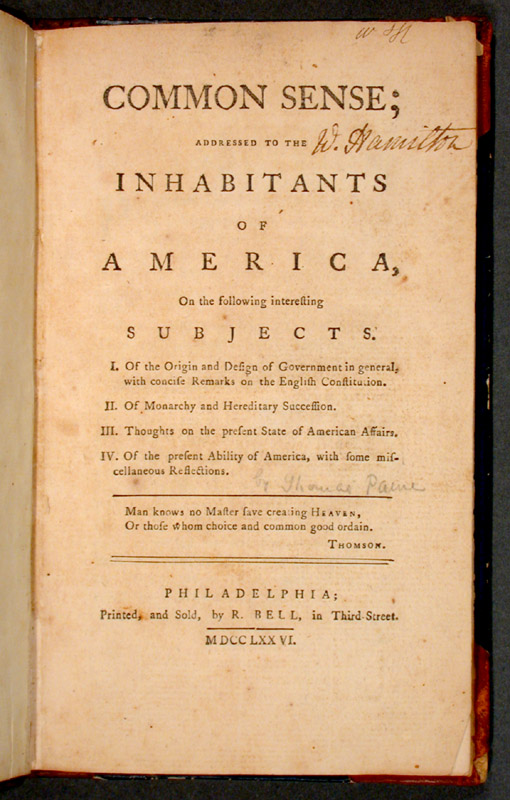

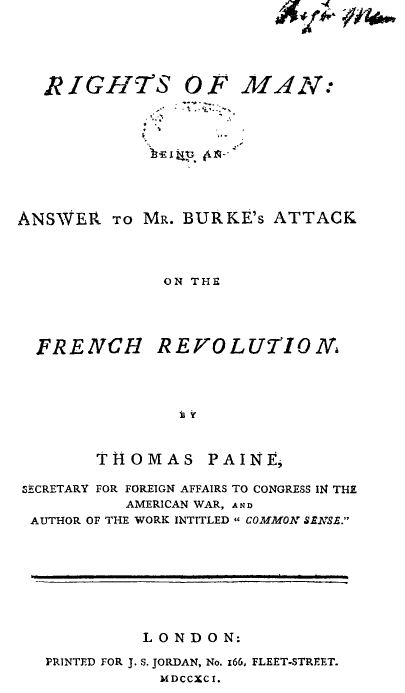

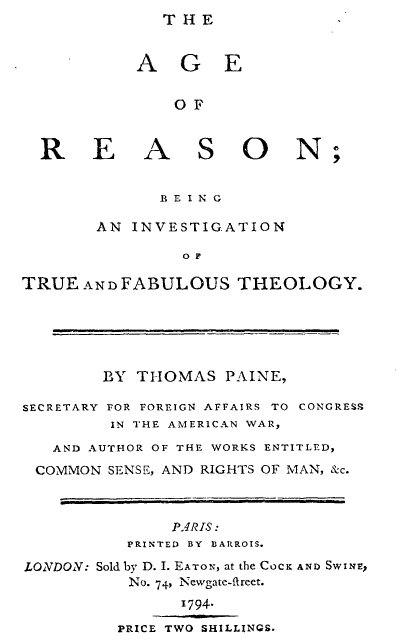

“President Putin even used my very strong campaign motto of ‘COMMON SENSE.’

We both believe very strongly in it,” Trump wrote, suggesting the former KGB agent on the other end of the line had chosen his words carefully to appeal to the US leader.

The Kremlin said Trump and Putin spoke for nearly 90 minutes.

Trump had been signaling for weeks his desire to speak with Putin as he works to resolve the Ukraine conflict.

As American officials travel in Europe this week, they have begun taking clearer positions on how the conclusion of the Ukraine war might look.

Speaking to a conference in Brussels, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said Kyiv joining NATO is unrealistic and that the US will no longer prioritize European and Ukrainian security as the Trump administration shifts its attention to securing US borders and deterring war with China.

Above: Logo of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Above: Flag of the European Union

Above: Flag of China

Meanwhile, Trump has spoken of striking a deal with Ukraine’s Zelensky for American access to the country’s valuable rare earth minerals as payment for continued American assistance.

Trump spoke with Zelensky midday, shortly after getting off the phone with Putin.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

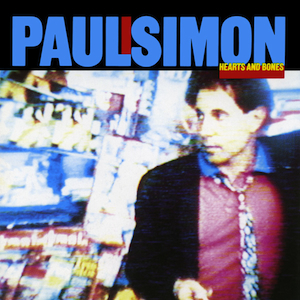

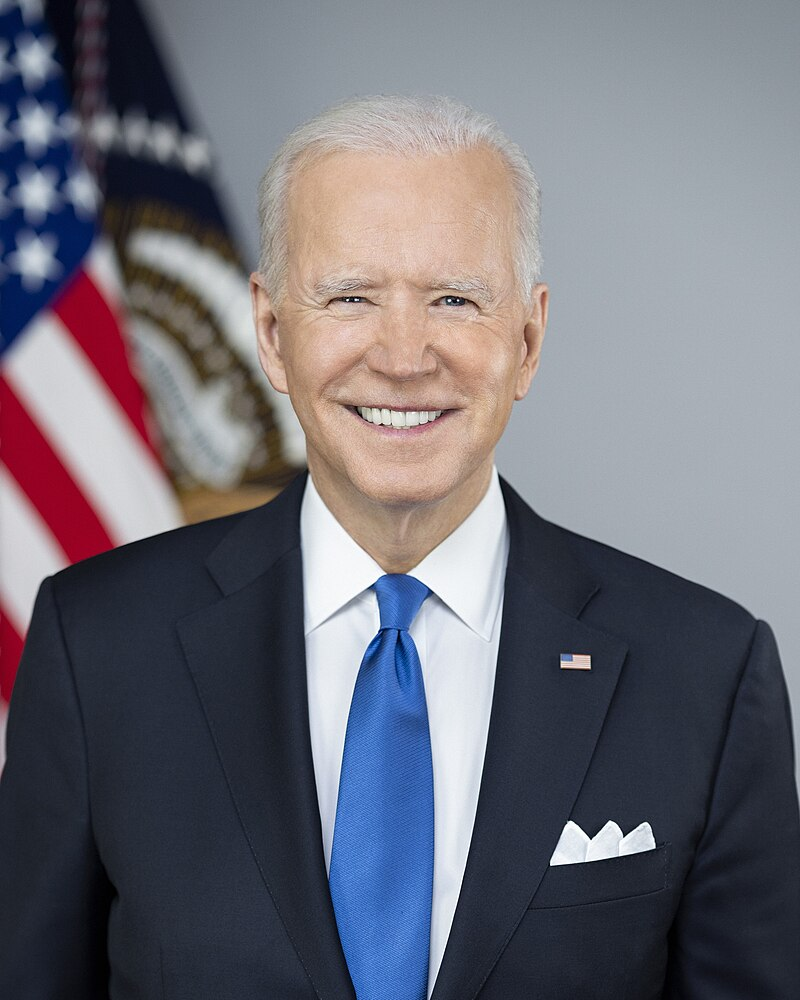

His predecessor, President Joe Biden, hadn’t spoken to his Russian counterpart in nearly three years, believing there was little to be gained in speaking to a leader he had deemed a war criminal.

Above: US President Joe Biden (r. 2021 – 2025)

The last US president to visit Russia was Barack Obama in 2013, when he attended a G20 summit.

Above: US President Barack Obama (r. 2009 – 2017)

Putin last visited in the United States in 2015 to attend United Nations talks.

Above: Flag of the United Nations

Later on Wednesday, Trump indicated that he could soon meet with Putin in Saudi Arabia but cautioned that no formal decision has been made on the matter.

“We think we’re going to probably meet in Saudi Arabia, the first meeting,” Trump said, hours after the two spoke by phone.

Above: Flag of Saudi Arabia

The President indicated that Saudi Arabian leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman would play a role in the discussions, saying, “We know the Crown Prince, and I think it’d be a very good place to be.”

A date for that meeting, Trump said, “hasn’t been set”, but he said it could be in the “not too distant future.

Above: Saudi Crown Prince/Prime Minister Mohammad bin Salman

Trump added he has not yet committed to go to Ukraine.

Asked whether Zelensky would be in attendance when he meets with Putin, Trump appeared to suggest he would not be present for the initial meeting:

“Probably we’ll have a first meeting and then we’ll see what we can do about the second meeting.”

“I would think about going, I’d think about it, no problem.”, he said.

Above: (in green) Ukraine

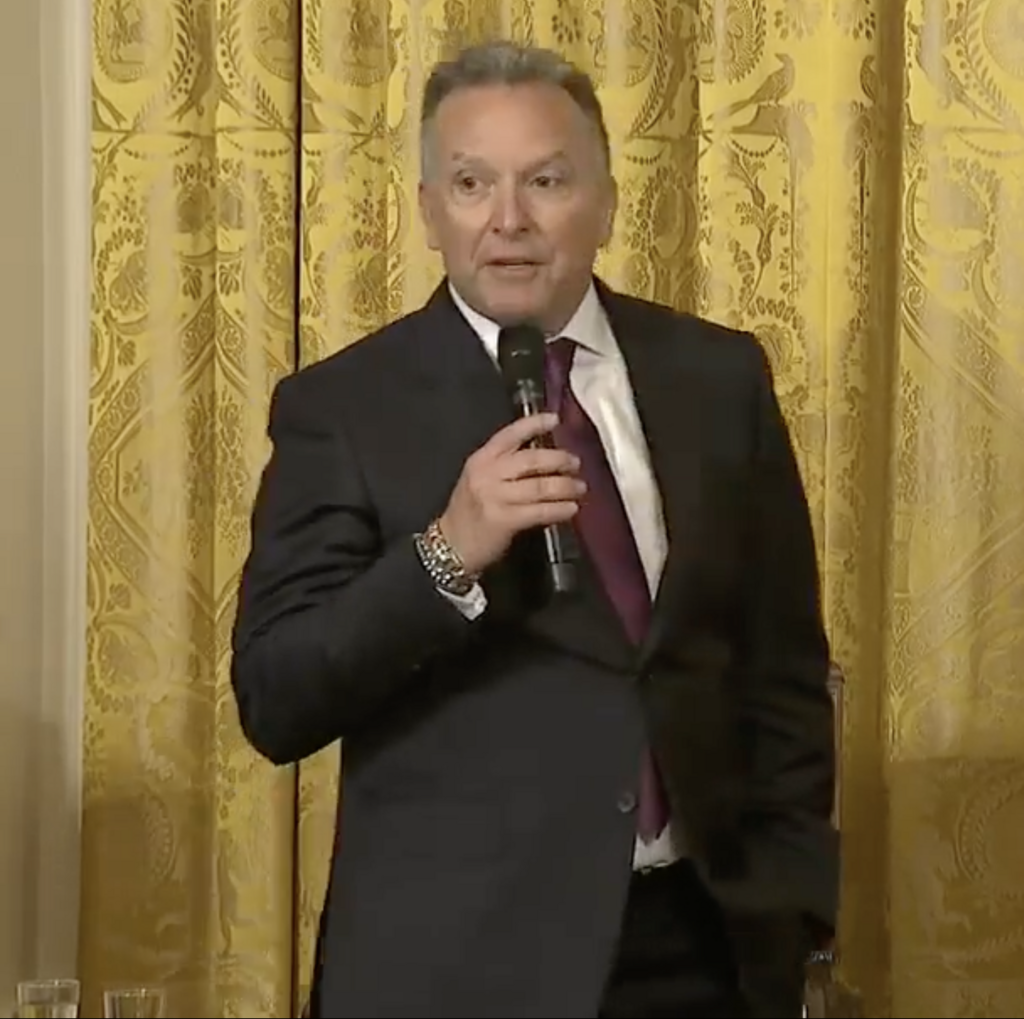

Steve Witkoff, who will be among Trump’s top negotiators on the conflict, pointed earlier Wednesday to the release of wrongfully detained American Marc Fogel as “an indication of what the possibilities are” for the future of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Above: American schoolteacher Marc Fogel

Marc Hilliard Fogel was arrested in August 2021 by Russian authorities for trying to enter Russia with 0.6 ounces (17 g) of medical cannabis.

In June 2022, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

He was released from Russia on 11 February 2025.

“I think that’s maybe a sign about how that working relationship between President Trump and President Putin will be in the future, and what that may portend for the world at large, for conflict and so forth.

I think they had a great friendship, and I think now it’s going to continue, and it’s a really good thing for the world.”, he said.

Above: US Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff

Witkoff met privately with Putin while in Moscow on Tuesday, two sources familiar with the meeting told CNN.

Above: Logo of the Cable News Network (CNN)

US President Donald Trump has held separate phone calls in quick succession with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on potentially moving forward with peace talks.

In a post on social media platform Truth Social, Trump said he had a “lengthy and highly productive phone call‘ with Russian President Vladimir Putin regarding negotiations to end the war in Ukraine.

Above: Flag of Russia

In the same post, Trump wrote:

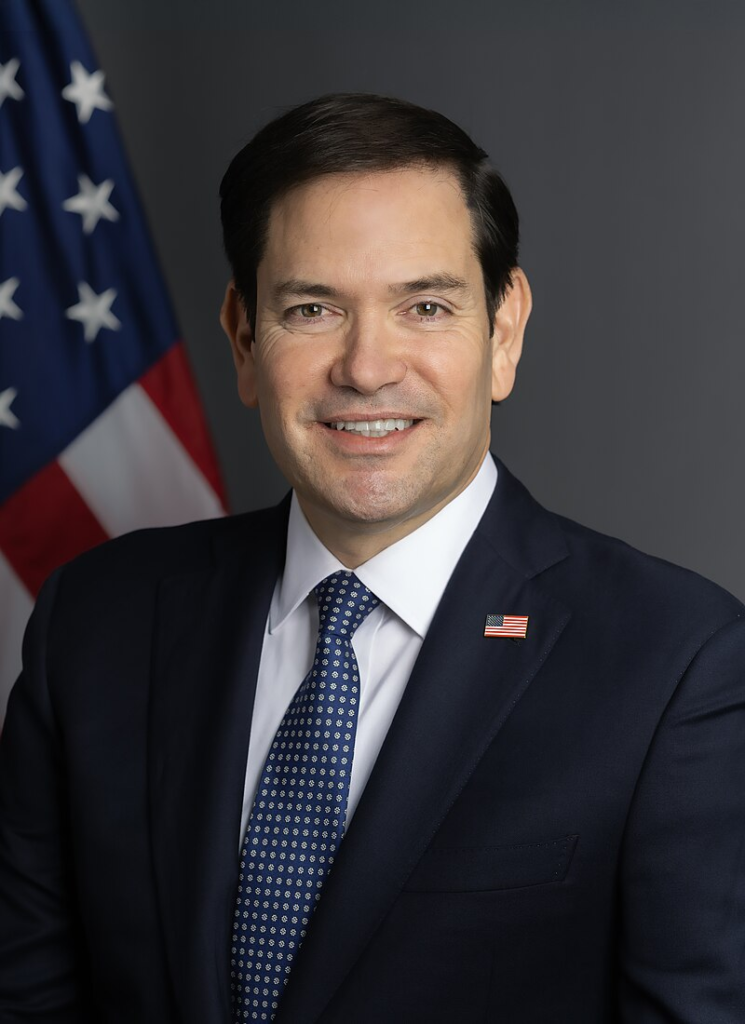

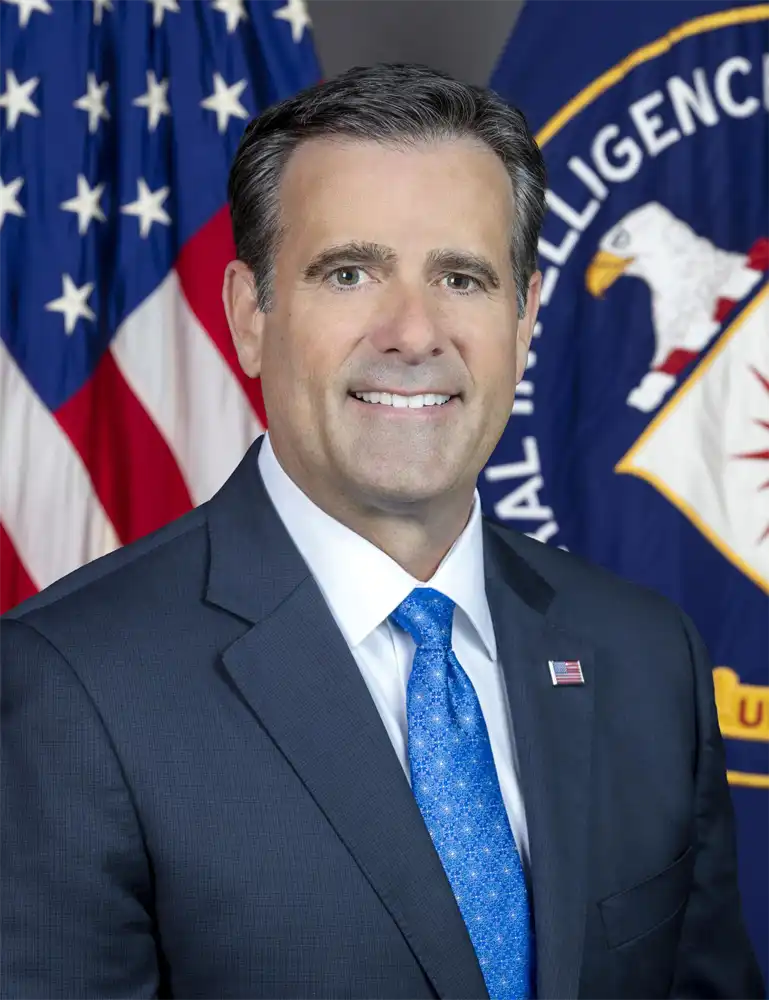

“I have asked Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Director of the CIA John Ratcliffe, National Security Advisor Michael Waltz, and Ambassador and Special Envoy Steve Witkoff, to lead the negotiations which, I feel strongly, will be successful.“

Above: US Secretary of State Marco Rubio

Above: CIA Director John Ratcliffe

Above: US National Security Advisor Michael Waltz

Trump said he and Putin also discussed other topics including the Middle East, energy, Artificial Intelligence and “the power of the dollar“, as well as reflected on the “great history of our nations“, and thanked him for the release of American school teacher Marc Fogel as part of a prisoner swap with Alexander Vinnik, a convicted Russian criminal.

Above: Russian computer expert Alexander Vinnik

On 25 July 2017, Vinnik was arrested in Ouranoupoli, Greece at the request of the US on suspicion of laundering $4 billion through the digital currency Bitcoin.

Above: Ouranoupoli, Greece

Above: Logo of Bitcoin

At the time, Vinnik denied the charges.

In late July 2017, US officials requested Vinnik’s extradition from Greece.

Above: Flag of Greece

In early October 2017, his extradition was requested by the Prosecutor General of Russia.

Above: Emblem of the Office of the Prosecutor General of Russia

In late June 2018, France requested his extradition, accusing him of fraud.

In early July 2018, Russia submitted a new extradition request, reportedly based on a confession to additional hacking offenses.

In November 2018, Vinnik went on a three-month hunger strike in protest of his detainment in Greece.

In January 2020, Vinnik was extradited to France.

Above: Flag of France

In June 2020, New Zealand Police announced the seizure of $90 million from WME Capital Management, a company in New Zealand registered to Vinnik.

Above: Flag of the New Zealand Police

In December 2020, Vinnik was acquitted on involvement with the Locky ransomware charges, but was sentenced to five years in prison for money laundering.

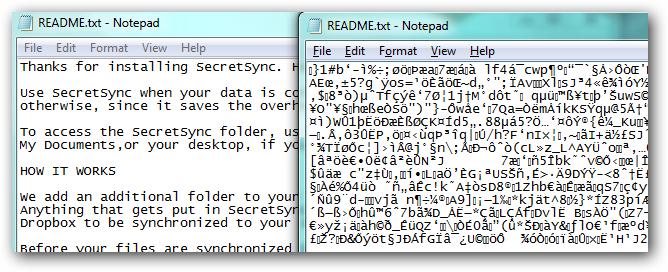

(Locky is ransomware malware released in 2016.

It is delivered by email (that is allegedly an invoice requiring payment) with an attached Microsoft Word document that contains malicious macros.

When the user opens the document, it appears to be full of gibberish, and includes the phrase “Enable macro if data encoding is incorrect“, a social engineering technique.

If the user does enable macros, they save and run a binary file that downloads the actual encryption Trojan, which will encrypt all files that match particular extensions.

Filenames are converted to a unique 16 letter and number combination. Initially, only the .locky file extension was used for these encrypted files.

Subsequently, other file extensions have been used, including .zepto, .odin, .aesir, .thor, and .zzzzz.

After encryption, a message (displayed on the user’s desktop) instructs them to download the Tor browser and visit a specific criminal-operated Web site for further information.

The website contains instructions that demand a ransom payment between 0.5 and 1 bitcoin (as of November 2017, one bitcoin varies in value between $9,000 and $10,000 via a bitcoin exchange).

Since the criminals possess the private key and the remote servers are controlled by them, the victims are motivated to pay to decrypt their files.

Cryptocurrencies are very difficult to trace and are highly portable.)

Above: Encrypted file

On 4 August 2022, Vinnik was extradited from Greece to the United States to face charges of money laundering and operation of an unlicensed money service business in the US.

On 5 August 2022, the United States Justice Department released a statement saying Vinnik’s first appearance for the 21-count superseding indictment from January 2017 had been that morning at a federal court in California.

In May 2024, Vinnik pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering.

Vinnik’s lawyer, Arkady Bukh, stated that he pled guilty “on a restricted number of charges” and that as a result of the plea bargain Bukh now expected Vinnik to get a prison term of less than 10 years.

Above: Azerbaijani American lawyer Arkady Bukh

On 12 February 2025, the US government announced it was releasing Vinnik as part of an exchange with Russia for the imprisoned American schoolteacher Marc Fogel.

Vinnik arrived in Russia the next day aboard a US Air Force special flight via Poland.

Soon after his conversation with Putin, Trump spoke with Zelenskyy, who later posted on X saying the two talked “about opportunities to achieve peace, discussed our readiness to work together at the team level. I am grateful to President Trump for his interest in what we can accomplish together“.

“Together with the US, we are charting our next steps to stop Russian aggression and ensure a lasting, reliable peace.”, said Zelenskyy.

“As President Trump said, let’s get it done.”, he continued, adding that the two had “agreed to maintain further contact and plan upcoming meetings“.

Zelenskyy also mentioned discussions he had had with US Secretary of Treasury Scott Bessent on the “preparation of a new document on security, economic cooperation, and resource partnership“.

Above: US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent

Meanwhile, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said Putin and Trump agreed in the telephone conversation to organize a meeting in person, and that the Russian President told Trump he is ready to receive Americans in the country.

“The Russian President supported one of the main theses of the head of the American state that the time has come for our countries to work together.”, the Kremlin spokesperson said.

Above: Kremlin Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov

Speaking about the war in Ukraine, Trump claimed that millions of people had died in a conflict that “would not have happened” if he were President when it began, and added that “it did happen, so it must end“.

Negotiations begin, but does that mean peace?

Wars do not simply end.

They leave scars, reshape borders, and rewrite lives.

Even if an agreement is reached, Ukrainians will still live with the destruction of cities, the loss of loved ones, and the psychological wounds of war.

Peace is more than laying down arms.

It is the fight to rebuild, to heal, to ensure that war does not return.

In the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, various stakeholders have pursued distinct objectives:

Russia:

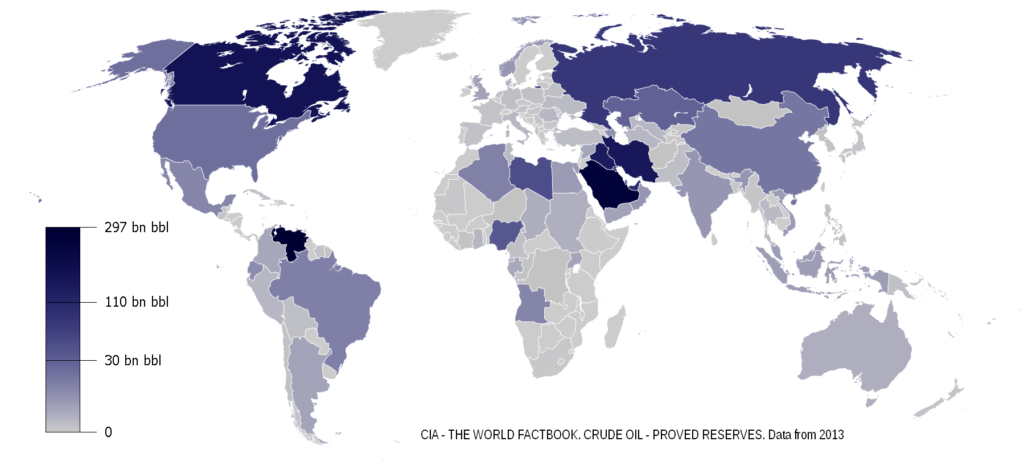

Aims to reassert its influence over Ukraine, prevent its integration into Western alliances like NATO and the EU, and secure access to valuable resources, including significant energy reserves in regions like Donbas.

Above: Coat of arms of Russia

Ukraine:

Seeks to preserve its sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence, striving for closer ties with Western nations to bolster security and economic development.

Above: Coat of arms of Ukraine

Western Countries (e.g., EU, USA):

Intend to support Ukraine’s sovereignty, counter Russian aggression, and maintain regional stability.

This involves imposing sanctions on Russia and providing military and economic aid to Ukraine.

Above: (in green) NATO members

Global Defense and Energy Sectors:

Defense industries have seen increased demand due to heightened security concerns, while energy markets have experienced volatility, affecting global oil and gas prices.

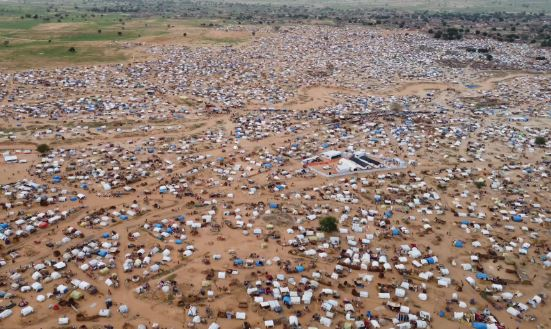

The civil war in Sudan has pushed a camp housing about 500,000 displaced people near the besieged Darfur city of El-Fasher into famine, an independent group of food security experts says.

Above: Aerial view of El-Fasir, North Dafur, Sudan

The 16-month conflict and restrictions on aid deliveries were to blame, the IPC’s Famine Review Committee (FRC) concluded after looking at new data.

“The scale of devastation brought by the escalating violence in el-Fasher is profound and harrowing.”, it said, explaining how Zamzam camp’s population had ballooned since April.

Above: Aerial view of the Zamzam refugee camp

The war – a power struggle between the Sudanese Army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – has created the world’s largest humanitarian crisis forcing 10 million people from their homes.

It comes as US-mediated talks, scheduled to begin in two weeks, appear to be in jeopardy.

Above: Flag of Sudan

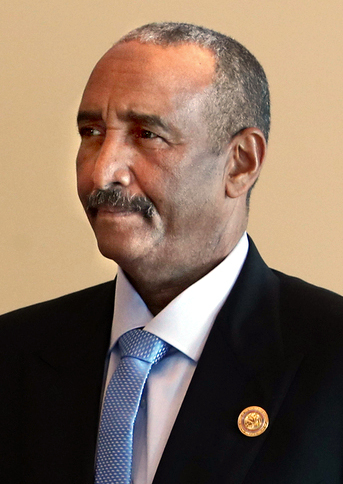

The RSF has accepted the invitation to Geneva, but it is unclear whether the army will go following Wednesday’s alleged assassination attempt on military leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Above: Emblem of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)

“The main drivers of famine in Zamzam camp are conflict and lack of humanitarian access, both of which can immediately be rectified with the necessary political will.”, the FRC said.

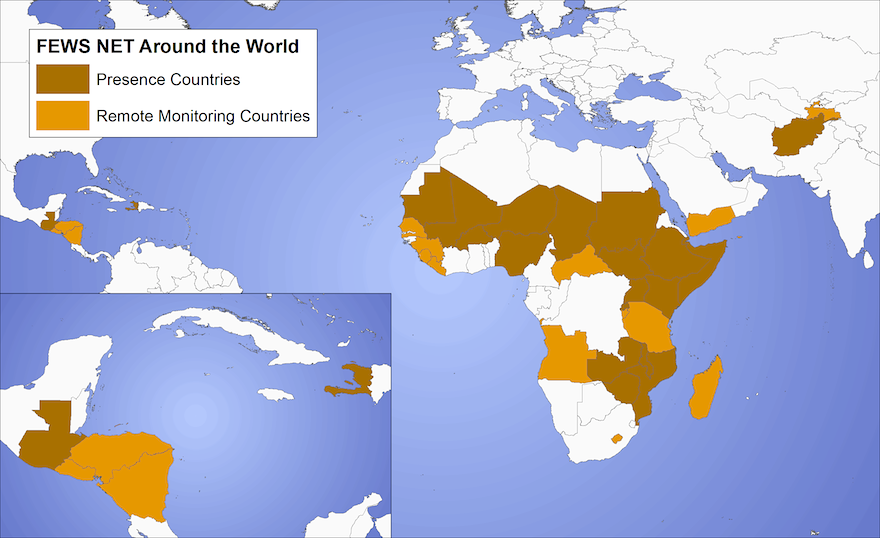

The committee, linked to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) – a global initiative by UN agencies, aid groups and governments which identifies famine conditions – analyzed two reports:

- the IPC’s Sudan working group’s latest assessment, which says 25.6 million people, or 54% of the population, are in high levels of acute food insecurity with 14 areas at risk of famine

- data published on Thursday from a US agency, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS Net)

FEWS Net said it was possible that famine was also ongoing in Abu Shouk and Al Salam camps, also near El-Fasher, but there was not enough evidence to conclusively say so.

The conditions for classifying an area to be in famine are that at least 20% of households must be facing an extreme lack of food, with 30% of children acutely malnourished and two people out of every 10,000 dying daily from starvation or from malnutrition and disease.

According to the FRC, around 320,000 people are believed to have fled the city, with around 150,000 to 200,000 moving to Zamzam camp “in search of security, basic services and food” in just a few weeks in May.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

That month the UN expert on genocide prevention said many civilians in El-Fasher were being targeted based on their ethnicity – warning that there was a growing risk of genocide.

Above: Kids playing, El-Faser, Sudan

The violence in Darfur is similar to the ethnic cleansing unleashed by Arab Janjaweed militias on non-Arab communities two decades ago.

Above: Flag of Darfur

The main market in Zamzam camp was now only open intermittently and by June prices had rocketed – by 63% for cooking oil, 190% for sugar, 67% for millet and 75% for rice, the FRC said, giving a glimpse in its 47-page report into what conditions are like in the crowded camp.

Famine conditions prevailed in June and July and were likely to persist until October – the harvest season.

However, the experts fear that the hunger crisis will not ease much as war has prevented many farmers from planting.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

The dire situation revealed by the reports about El-Fasher, particularly in Zamzam camp, was “merely the tip of the iceberg”, Barrett Alexander, from the aid agency Mercy Corps, warned.

“Drawing from our experience with previous famines, we know that widespread deaths have already occurred by the time a famine is officially declared.”

He added that a recent Mercy Corps assessment in Central and South Darfur had revealed that nine out of 10 children were suffering from life-threatening malnutrition.

Above: Logo of US NGO Mercy Corps

One of the last aid groups operating in El-Fasher, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), said things were likely to get worse if an apparent blockade on humanitarian aid was not lifted urgently.

“Our trucks left N’Djamena in Chad over six weeks ago and they should have reached el-Fasher by now, but we have no idea when they will be released.”, said MSF’s Stéphane Doyon, MSF’s head of emergencies in Sudan.

The warring sides have both been accused of blocking and looting aid.

Both deny the allegations.

The MSF lorries are carrying therapeutic food and medical supplies for children in Zamzam camp as well as surgical supplies for the last remaining hospital in El-Fasher that does surgery.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

The Saudi hospital was hit by shelling on Monday that killed three staff and injured at least 25 people – the 10th attack in under three months, the charity said.

“We do not know if hospitals are being intentionally targeted, but the incident on Monday shows that the belligerents are not taking any precautions to spare them.” Doyon said.

Above: Saudi Hospital, El-Fashir, Sudan

A paramilitary force in Sudan has stormed the country’s largest displacement camp, looting and setting fire to the market and several homes, a local refugee group has said.

The Zamzam camp in North Darfur has been hit by intense artillery shelling since late last year, but this is the first time the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has been accused of sending in fighters.

An eyewitness told the BBC the situation at the camp was “extremely catastrophic“, and there were many casualties.

The nearby city of El-Fasher, one of the centres of the civil war that erupted in 2023, is already under siege by the RSF as it battles the army.

The military and RSF had been allies – coming to power together in a coup – but fell out over an internationally backed plan to move towards civilian rule.

The Sudanese IDPs and Refugees Bloc said Zamzam camp was invaded on Tuesday.

However, an RSF spokesman denied its fighters had penetrated it, saying they had seized a nearby military base belonging to an armed group that fights alongside the Sudanese military, after it had shelled RSF checkpoints for days.

BBC Verify has confirmed social media footage that shows men waving guns triumphantly with flames behind them and saying they are in the camp.

The insignia has been removed from their uniforms, but the man filming the video has RSF markings.

Asked about the damage to the market the RSF spokesman said the group had “circulated a message in which we committed to protect the camp residents and asked them to stay away from the fire exchange areas“.

Zamzam hosts about half a million displaced people who were already suffering from famine.

Reports said the attack forced thousands of them to flee again.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

Medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which runs a hospital in Zamzam, said it had received seven dead bodies and 21 injured people at the hospital it runs in Zamzam.

Most of them were in a serious condition, but the hospital lacked the ability to care for all of them, an MSF spokesperson added.

The eyewitness the BBC spoke to said the hospital no longer had a functioning surgery.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

North Darfur’s Health Minister Ibrahim Abdullah Khater told the BBC that the wounded were not able to reach El-Fasher for treatment because the RSF was blocking the road and preventing access to the city.

“The ones suffering the most are the displaced people.”, he said.

Above: Flag of North Dafur

The humanitarian catastrophe worsened late last year when Zamzam came under heavy artillery fire, which aid organizations, including MSF, blamed on the RSF.

A group of international non-governmental organizations issued a statement in December, saying the attacks on Zamzam marked “an escalation in violence on a site which has previously been spared from active hostilities“, although it was “consistent with a pattern of attacks” on other camps for displaced people.

“This underscores the reality that there are now no safe places for people to flee to in North Darfur.”, it said.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

The siege of El-Fasher began last April – a year into the conflict.

It is the only city still under army control in Darfur, where the RSF has been accused of carrying out ethnic cleansing against non-Arab communities.

Above: El-Fasher, Sudan

In April last year, Sudan was thrown into disarray when its army and a powerful paramilitary group began a vicious struggle for power.

The war, which continues to this day, has claimed more than 15,000 lives.

And in what the United Nations has called one of the world’s “largest displacement crises“, about nine million people have been forced to flee their homes.

There have been warnings of genocide regarding the western region of Darfur, where residents say they have been targeted by fighters based on their ethnicity.

Above: (in yellow) Darfur, Sudan

Here is what you need to know.

Sudan is in northeast Africa and is one of the largest countries on the continent, covering 1.9 million sq km (734,000 sq miles).

The population of Sudan is predominantly Muslim.

The country’s official languages are Arabic and English.

Above: (in green) Sudan

Even before the war started, Sudan was one the poorest countries in the world.

Its 46 million people were in 2022 living on an average annual income of $750 (£600) a head.

The conflict has made things much worse.

Last year, the economy shrunk by 40%, Sudan’s Finance Minister said.

After the 2021 coup, a council of generals ran Sudan, led by the two military men at the centre of this dispute:

- General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of the armed forces and in effect the country’s President

Above: Sudanese General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan

- His deputy and leader of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as “Hemedti“

Above: Sudanese General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo

They disagreed on the direction the country was going in and the proposed move towards civilian rule.

The main sticking points were plans to include the 100,000-strong RSF into the army, and who would then lead the new force.

The suspicions were that both generals wanted to hang on to their positions of power, unwilling to lose wealth and influence.

Above: Insignia of the Sudanese Armed Forces

The RSF was formed in 2013 and has its origins in the notorious Janjaweed militia that brutally fought rebels in Darfur, where they were accused of ethnic cleansing against the region’s non-Arabic population.

Since then, General Dagalo has built a powerful force that has intervened in conflicts in Yemen and Libya.

He has also developed economic interests including controlling some of Sudan’s gold mines.

Before the current conflict erupted, the RSF had been accused of human rights abuses, including the massacre of more than 120 protesters in June 2019.

Such a strong force outside the army has been seen as a source of instability in the country.

Above: Flag of the Rapid Support Forces

Shooting between the two sides began on 15 April 2023 following days of tension as members of the RSF were redeployed around the country in a move that the army saw as a threat.

There had been some hope that talks could resolve the situation but these never happened.

It is disputed who fired the first shot but the fighting swiftly escalated in different parts of the country.

This fighting is the latest episode in bouts of tension that followed the 2019 ousting of long-serving President Omar al-Bashir, who came to power in a coup in 1989.

There were huge street protests calling for an end to his near-three decade rule and the army mounted a coup to get rid of him.

Above: Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (r. 1993 – 2019)

But civilians continued to campaign for the introduction of democracy.

A joint military-civilian government was then established but that was overthrown in another coup in October 2021, when General Burhan took over.

And since then the rivalry between General Burhan and General Dagalo has intensified.

A framework deal to put power back in the hands of civilians was agreed in December 2022 but talks to finalize the details failed.

When it began, the conflict appeared to be around the control of key installations.

However, much of it is now happening in urban areas and civilians have become unwitting victims.

The RSF captured much of the capital Khartoum, as well as Darfur.

Above: Khartoum, Sudan

The military controls most of the north and the east, including the key Red Sea port of Port Sudan.

Above: Port Sudan, Sudan

In a major blow to the army, the RSF seized the strategic city of Wad Madani in December, along with much of the surrounding Gezira state.

Hundreds and thousands of civilians were forced to flee the city, which had become a hub for humanitarian services and a refuge for those who had escaped conflict in other parts of the country.

Above: Wad Madani, Sudan

In February, the army recaptured the centre of Omdurman, one of three cities along the River Nile that form Sudan’s wider capital, Khartoum.

It regained control of the state broadcaster there – a symbolic breakthrough for the army.

Above: Market, Omdurman, Sudan

Attention is now on El-Fasher, the last major urban centre in Darfur that is still held by the army.

The RSF has laid siege to the city, causing hundreds of casualties, overwhelming hospitals and blocking food supplies.

There are wars that never make headlines.

Or they make headlines for as long as it takes until something else somewhere else happens.

When the cameras are turned off and the crews have left does not mean that the death and destruction departed with them.

The violence continues whether the world is watching or not.

The people of Zamzam — many of them displaced, their lives shattered— were attacked in a place that was supposed to be a refuge.

For them, there is no “after” the war.

There is only survival.

Whether they once held weapons or were merely caught in the fire, their war is not over.

Above: Zamzam refugee camp

The Rapid Support Forces stormed the Zamzam Refugee Camp in North Darfur, attacking those who had already lost everything.

Where can one flee when war does not recognize safe havens?

The people of Zamzam did not sign up for battle, yet they live and die by its brutal terms.

Some may have once been soldiers, but many were simply caught in the crossfire.

Their war is not fought with weapons — it is fought in the struggle to survive, to find shelter, to hold on to the last remnants of humanity.

Above: Zamzam camp near el-Fasher is hosting an estimated 500,000 people, who are living in famine conditions

Red Hand Day, or the International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers, has been observed on February 12 annually since 2002, where pleas are made to political leaders and events are staged around the world to draw attention to child soldiers:

Children under the age of 18 who participate in military organizations of all kinds.

Red Hand Day aims to call for action to stop this practice, and support children affected by it.

Above: Red Hand Day logo

Children in the military, including state armed forces, non-state armed groups, and other military organizations, may be trained for combat, assigned to support roles, such as cooks, porters/couriers, or messengers, or used for tactical advantage such as for human shields, or for political advantage in propaganda.

Children (defined by the Convention on the Rights of the Child as people under the age of 18) have been recruited for participation in military operations and campaigns throughout history and in many cultures.

Children are targeted for their susceptibility to influence, which renders them easier to recruit and control.

Relative to adults, the neurological underdevelopment of children, including adolescent children, renders them more susceptible to recruitment and also more likely to make consequential decisions without due regard to the risks.

Once recruited, children are easier than adults to indoctrinate and control, and are more motivated than adults to fight for non-monetary incentives such as religion, honor, prestige, revenge and duty.

While some are recruited by force, others choose to join up, often to escape poverty or because they expect military life to offer a rite of passage to maturity.

Child soldiers who survive armed conflict frequently develop psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioral problems such as heightened aggression, which together lead to an increased risk of unemployment and poverty in adulthood.

Research in the United Kingdom has found that the enlistment and training of adolescent children, even when they are not sent to war, is often accompanied by a higher risk of suicide, stress-related mental disorders, alcohol abuse and violent behavior.

Since the 1960s, a number of treaties have successfully reduced the recruitment and use of children worldwide.

Nonetheless, around a quarter of armed forces worldwide, particularly those of Third World nations, still train adolescent children for military service, while elsewhere, the use of children in armed conflict and insurgencies has increased in recent years.

Above: Child Soldier in the Ivory Coast, Gilbert G. Groud (2007)

As of 2022, the United Nations (UN) verified that nine state armed forces were using children in hostilities:

- Central African Republic

Above: Flag of the Central African Republic

As many as 10,000 children were used by armed groups in the armed conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) between 2012 and 2015, and as of 2024 the problem persists nationwide with a most likely greater amount fighting now.

The mainly Muslim “Séléka” coalition of armed groups and the predominantly Christian, “Anti-Balaka” militias have both used children in this way; some are as young as eight.

Above: (in green) Central African Republic

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

Above: Flag of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

During the first (1996 – 1997) and second (1998 – 2003) civil conflicts which took place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), all sides involved in the war actively recruited or conscripted child soldiers, known locally as Kadogos which is a Swahili term meaning “little ones“.

In 2011 it was estimated that 30,000 children were still operating with armed groups.

The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), released a report in 2013 which stated that between 1 January 2012 and August 2013 up to 1,000 children had been recruited by armed groups, and described the recruitment of child soldiers as “endemic“.

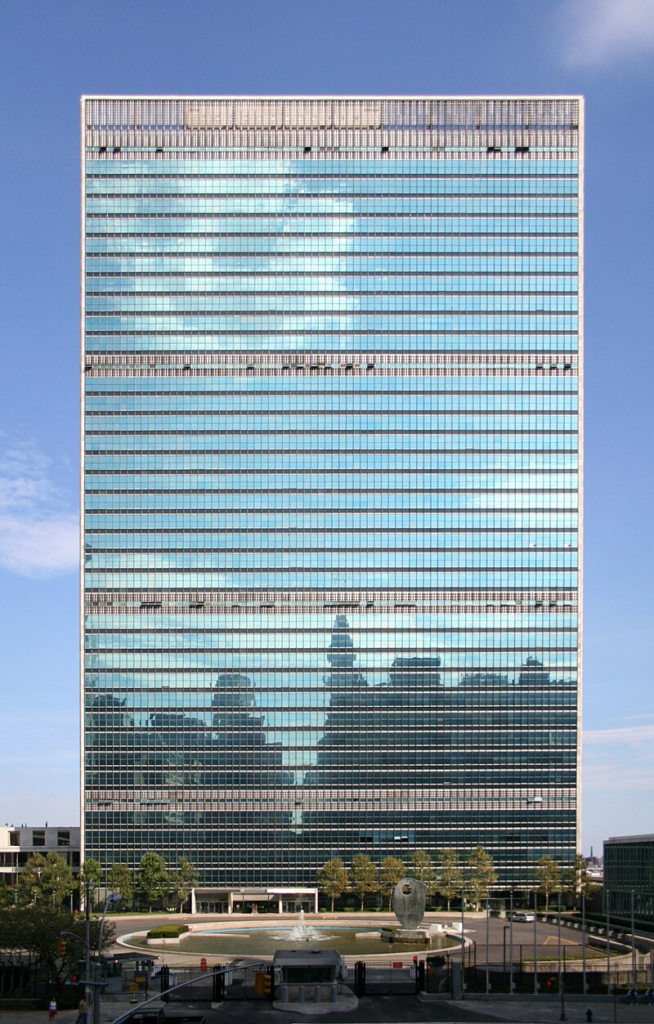

Above: Emblem of the United Nations

Former President Laurent-Désiré Kabila used children in the Second Congo War from 1996 onwards.

It is estimated that up to 10,000 children, some aged only seven years old, served under him.

Kabila was assassinated by one of these child soldiers during the Second Congo War in 2001.

Above: Congolese President Laurent Désiré Kabila (1939 – 2001)

The International Criminal Court (ICC), in the first trials held on human rights violations in the DRC, led to the first indictments, the first trials and the first convictions, in national jurisprudence for the use of children in combat.

Above: Logo of the International Criminal Court, Den Haag, Netherlands

Above: (in green) Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Mali

Above: Flag of Mali

Above: (in green) Mali

- Somalia

Above: Flag of Somalia

The use of child soldiers in Somalia has been an ongoing issue.

In the battles for Mogadishu, all parties involved in the conflict such as the Union of Islamic Courts, the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism, and the Transitional Federal Government (TFG)(2004 – 2012) forces recruited children for use in combat.

Above: Images of Mogadishu, Somalia

The TFG is listed by the United Nations (UN) as one of the greatest offenders in recruiting children into their armed forces.

The militant rebel group al-Shabaab who are fighting to establish an Islamic state is another major recruiter of children.

Above: Flag of Al-Shabaab

The European Union (EU) and the United States (US) were the primary supporters of the TFG, with the US having paid wages to the TFG armed forces, in violation of the US Child Soldiers Protection Act.

In 2010, Human Rights Watch reported that Al-Shabaab was recruiting children as young as ten to bolster their forces.

Children are abducted from their homes and schools with entire classes at times being abducted.

In 2012 Michelle Kagari, Amnesty International’s deputy director for Africa, stated that:

“Somalia is not only a humanitarian crisis:

It is a human rights crisis and a children’s rights crisis.

Children in Somalia risk death constantly.

They can be killed, recruited, and sent to the frontline, punished by al-Shabab because they are caught listening to music or ‘wearing the wrong clothes’, be forced to fend for themselves because they have lost their parents or even die because they don’t have access to adequate medical care.“

In 2017, UN Secretary-General António Guterres commented on a report from the UN Security Council, which estimated that over 50% of Al-Shabaab’s fighting strength was made up of children, with some as young as nine being sent to the front.

The report verified that 6,163 children had been recruited between 1 April 2010 and 31 July 2016, of which 230 were girls.

According to the report, a task force in Somalia verified the recruitment and use of 6,163 children – 5,993 boys and 230 girls – during the period from 2010, to 2016, with more than 30% of the cases in 2012, with the Somali National Army accounted for 920 children serving.

Al-Shabaab accounted for 70% of verified cases.

Above: UN Secretary-General António Guterres

Above: (in green) Somalia

- South Sudan

Above: Flag of South Sudan

Above: (in green) South Sudan

- Palestine

Above: Flag of Palestine

Above: (in green) Palestine

- Syria

Above: Flag of Syria

Above: (in green) Syria

- Yemen

Above: Flag of Yemen

Above: (in green) Yemen

- Afghanistan

Above: Flag of Afghanistan

Above: (in green) Afghanistan

- Myanmar

Above: Flag of Myanmar

Above: (in green) Myanmar

The United Nations (UN) Committee on the Rights of the Child and others have called for an end to the recruitment of children by state armed forces, arguing that military training, the military environment, and a binding contract of service are not compatible with children’s rights and jeopardize healthy development.

In 2003, one estimate calculated that child soldiers participated in about three-quarters of ongoing conflicts.

In the same year, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) estimated that most of these children were aged over 15, although some were younger.

Due to the widespread military use of children in areas where armed conflict and insecurity prevent access by UN officials and other observers, it is difficult to estimate how many children are affected.

In 2003, UNICEF estimated that some 300,000 children are involved in more than 30 conflicts worldwide.

Above: Logo of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

In 2017, Child Soldiers International (1998 – 2019) estimated that several tens of thousands of children, possibly more than 100,000, were in state and non-state military organizations around the world.

In 2018 the organization reported that children were being used to participate in at least 18 armed conflicts.

In 2023, the UN Secretary General report presented 7,622 verified cases of children being recruited and used in armed conflicts in 23 countries.

Above: The Secretariat Building is a 154-metre-tall (505 ft) skyscraper and the centerpiece of the Headquarters of the United Nations, New York City, USA

More than 12,460 children formerly associated with armed forces or groups received protection or reintegration support during 2022.

Child soldiers who survive armed conflict face a markedly elevated risk of debilitating psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioral problems.

Above: Child soldier, Yemen

Research in Palestine and Uganda, for example, has found that more than half of former child soldiers showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and nearly nine in ten in Uganda screened positive for depressed mood.

Above: Child soldier, Uganda

Above: Flag of Uganda

Above: (in green) Uganda

Researchers in Palestine also found that children exposed to high levels of violence in armed conflict were substantially more likely than other children to exhibit aggression and anti-social behavior.

Above: Child soldier, Palestine

The combined impact of these effects typically includes a high risk of poverty and lasting unemployment in adulthood.

Further harm is caused when armed forces and groups detain child recruits.

Above: Child soldier, Yemen

Children are often detained without sufficient food, medical care, or under other inhumane conditions.

Some experience physical and sexual torture.

Some are captured with their families, or detained due to one of their family members’ activity.

Lawyers and relatives are frequently banned from any court hearing.

Above: Child soldier, South Sudan

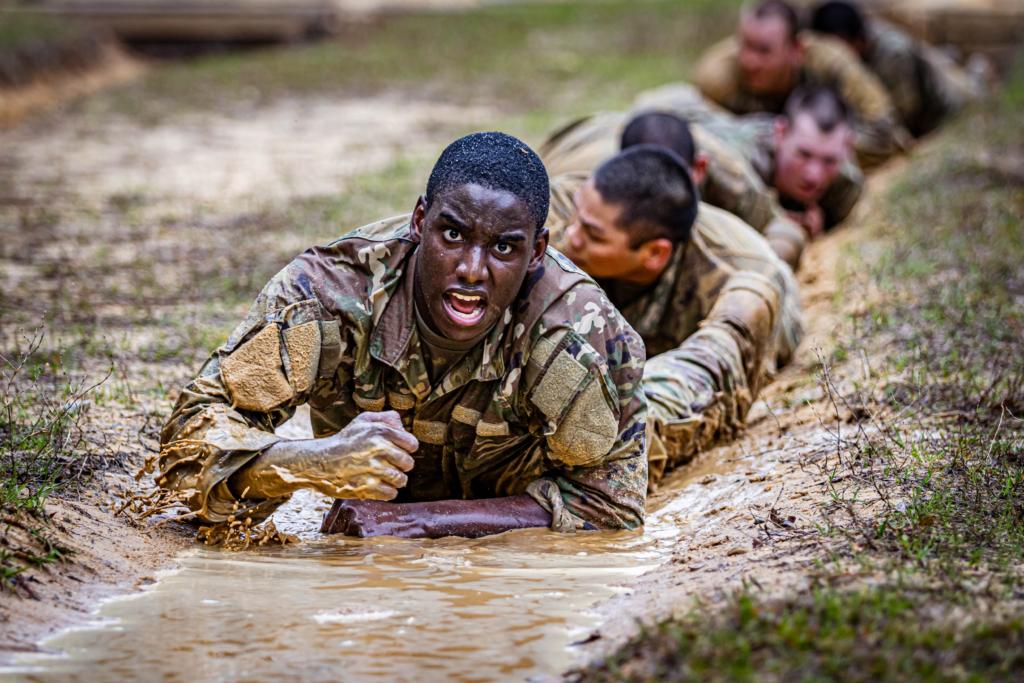

While the use of children in armed conflict has attracted most attention, other research has found that military settings present several serious risks before child recruits are deployed to war zones, particularly during training.

Research from several countries finds that military enlistment, even before recruits are sent to war, is accompanied by a higher risk of attempted suicide in the US, higher risk of mental disorders in the US and the UK, higher risk of alcohol misuse and higher risk of violent behavior, relative to recruits’ pre-military experience.

Military academics in the US have characterized military training as “intense indoctrination” in conditions of sustained stress, the primary purpose of which is to establish the unconditional and immediate obedience of recruits.

The research literature has found that adolescents are more vulnerable than adults to a high-stress environment, particularly those from a background of childhood adversity.

It finds in particular that the prolonged stressors of military training are likely to aggravate pre-existing mental health problems and hamper healthy neurological development.

Military settings are characterized by elevated rates of bullying, particularly by instructors.

In the UK between 2014 and 2020, for example, the Army recorded 62 formal complaints of violence committed by staff against recruits at the military training centre for 16- and 17-year-old trainee soldiers, the Army Foundation College.

Joe Turton, who joined up aged 17 in 2014, recalls bullying by staff throughout his training.

For example:

The corporals come into the hangar where we sleep and they’re wild-eyed, screaming, shoving people out.

A massive sergeant lifts a recruit in the air and literally throws him into the wall.

A corporal smacks me full-force around the head — I’ve got my helmet on but he hits me so hard that I’m knocked right over, I mean this man’s about 40 and I’m maybe 17 by then.

A bit later, we’re crawling through mud and a corporal grabs me and drags me along the ground, half-way across a field.

When he lets go I’m in that much pain that I’m whimpering on the ground.

When the other corporal, the one who hit me, sees me crying on the ground, he just points at me and laughs.”

Above: Logo of the Army Foundation College, Harrogate, England

In many countries growing populations of young people relative to older generations have made children a cheap and accessible resource for military organizations.

Some leaders of armed groups have claimed that children, despite their underdevelopment, bring their own qualities as combatants to a fighting unit, often being remarkably fearless, agile and hardy.

The global proliferation of light automatic weapons, which children can easily handle, has also made the use of children as direct combatants more viable.

Above: Child soldier, South Sudan

In a 2004 study of children in military organizations around the world, Rachel Brett and Irma Specht pointed to a complex of factors that incentivize children to join military organizations, particularly:

- Background poverty including a lack of civilian education or employment opportunities

- The cultural normalization of war

- Seeking new friends

- Revenge (for example, after seeing friends and relatives killed)

- Expectations that a “warrior” role provides a rite of passage to maturity

Above: Child soldiers, South Sudan

The following testimony from a child recruited by the Cambodian armed forces in the 1990s is typical of many children’s motivations for joining up:

I joined because my parents lacked food and I had no school.

I was worried about mines but what can we do — it’s an order to go to the front line.

Once somebody stepped on a mine in front of me — he was wounded and died.

I was with the radio at the time, about 60 metres away.

I was sitting in my hammock and saw him die.

I see young children in every unit.

I’m sure I’ll be a soldier for at least a couple of more years.

If I stop being a soldier, I won’t have a job to do because I don’t have any skills.

I don’t know what I’ll do.”

Above: Flag of Cambodia

Above: (in red) Cambodia

Above: Emblem of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces

February 12 marks Red Hand Day, a reminder of the thousands of children forced into war.

They do not get the chance to be soldiers who come home.

They do not get a choice at all.

Given rifles instead of toys, taught to kill before they learn to dream, they are robbed of innocence and thrust into nightmares they can never escape.

Even if they are freed, what remains of them?

How does a child unlearn war?

There is no choice in their war.

Above: Warsaw’s (Poland) Little Insurgent monument commemorates all child soldiers who fought in World War II and earlier conflicts.

Child soldiers are born into conflict, ripped from their families, and forced to kill before they can understand what life should be.

And even if they escape, how do they return to a world they never knew?

For them, war is not just a battle.

It is their stolen childhood, their stolen peace, their stolen humanity.

Does struggle shape our humanity?

Or does our humanity make struggle inevitable?

Perhaps the answer is both.

Above: French Emperor Napoleon I’s (1769 – 1821) retreat from Moscow, Russia (1812)

Throughout history, adversity has been a catalyst for growth, resilience, and ingenuity.

Whether through war, hardship or inner turmoil, humans are often refined by their struggles.

Great art, literature, philosophy, and even technological progress have often emerged from conflict — whether external or internal.

In this sense, struggle defines us, forcing us to confront our limitations and, in doing so, transcend them.

Above: D-Day Landing, Normandy, France – 6 June 1944

Would we appreciate peace, love, or freedom if we had never known war, loss, or oppression?

Would we strive for greatness if not for the obstacles in our path?

At the same time, human nature — driven by desire, fear, ambition, and ego — creates struggle where none might have existed.

Even when resources are plentiful, we find reasons to compete.

Even when peace is possible, we distrust it.

Even when we have enough, we want more.

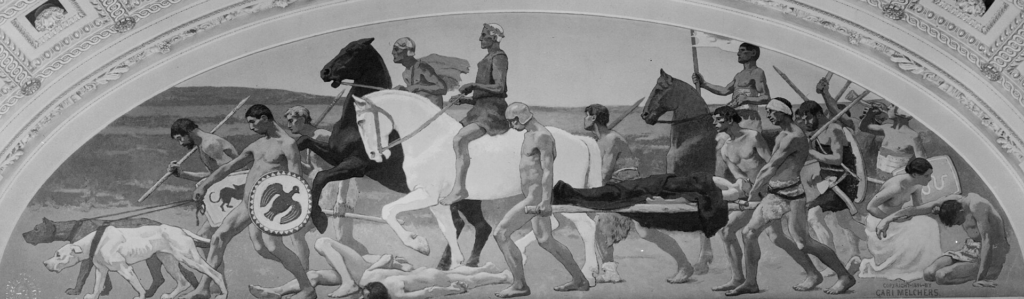

Above: War, Gari Melchers (1896)

Our ability to dream, to desire, to push beyond what we have been given is what makes us human.

But it also makes struggle inevitable.

Above: American tanks moving in formation during the Gulf War (1990 – 1991)

We wage wars not only over land and power, but also over ideas, identity and belief.

We struggle against nature, against each other, and, most of all, against ourselves.

If struggle is what shapes us, but our humanity ensures we will always struggle, then peace — true, lasting peace — becomes almost unnatural.

And yet, we long for it.

Above: US Army soldiers engaged in a firefight with Taliban insurgents during the War in Afghanistan (2009)

Perhaps, then, the most human thing of all is the desire for peace, even as we are trapped in the cycle of struggle.

To seek peace, knowing we may never truly achieve it, is the ultimate act of defiance against our own nature.

Would we ever be willing to let go of the struggle?

Or is it the striving, the constant reaching, that gives our lives meaning?

Above: The remains of dead Crow Indians killed and scalped by Sioux (1874)

Thomas Millman, physician to the North American Boundary Commission, kept a diary of his experiences while in the West.

On 31 July 1874, he wrote:

“We met with Boswell & Dawson & the photographers.

They were getting the photo of some dead Indians.

They appear to be Crow Indians killed last winter by the Pegans.

About 20 altogether were riddled with bullet holes & every one scalped.

Most of them had their shirts & every one had a gash in their side.

Bodies were shriveled up but skin pretty sound.”

That line — between necessary struggle and unwarranted violence — is one of the most difficult to define.

It shifts with time, perspective and circumstance.

Yet, if we are to strive for a more just world, we must attempt to draw it.

Above: Ruins of Warsaw’s Napoleon Square in the aftermath of World War II (1939 – 1945)

Some struggles are essential to human dignity and progress:

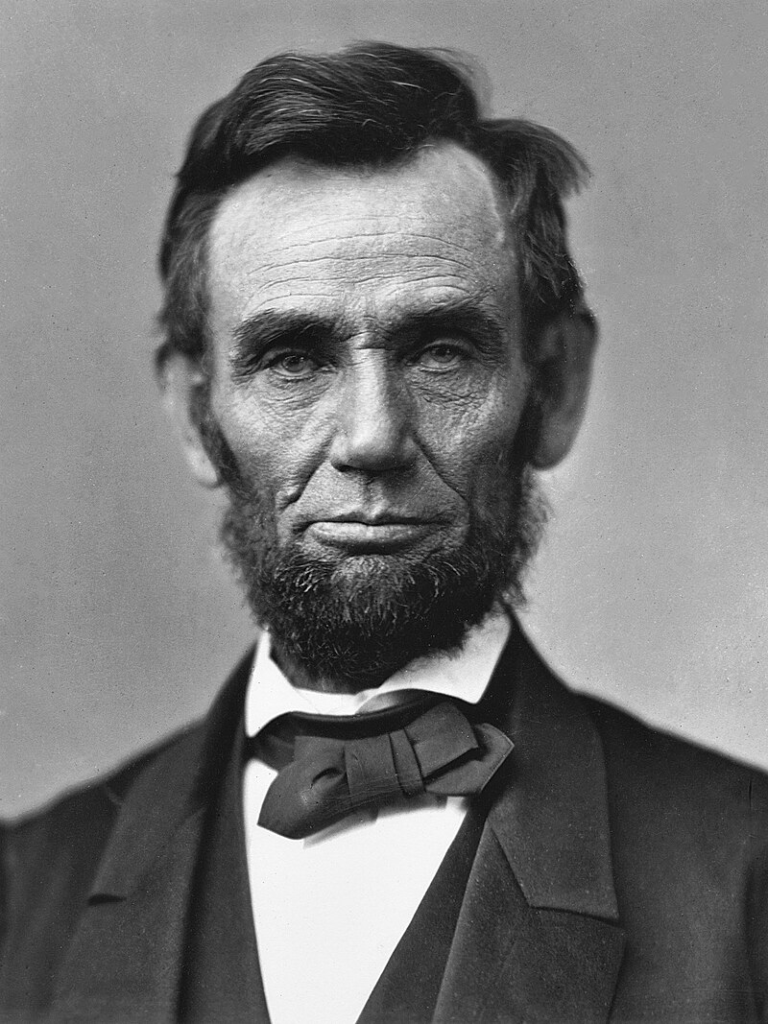

- The Struggle for Freedom and Rights

History shows that without struggle, oppression persists.

From the abolition of slavery to civil rights movements, people have fought for justice, often at great cost.

These struggles are not about destruction but about dismantling systems of injustice so that all can live with dignity.

Above: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 28 August 1963.

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929 – 1968) grew up in a time of extreme segregation, but he did not let that stop him from being a dreamer.

He had a dream that would resonate with his country, and he became a major leader of the civil rights movement.

- The Struggle for Survival and Progress

Whether in personal growth, scientific discovery, or overcoming hardship, struggle can be a source of resilience and innovation.

Struggling to learn, to build, to heal — these are the struggles that elevate humanity.

- Defensive Struggle

There are times when force is used to protect rather than conquer.

Defending oneself, one’s home, or the vulnerable against aggression is not the same as initiating violence.

Above: Battle of Stalingrad, Russia

Violence becomes unwarranted when:

- It is motivated by greed, power or hate.

Wars fought for conquest, genocide, ethnic cleansing and acts of terror stem from a place of destruction rather than progress.

For example:

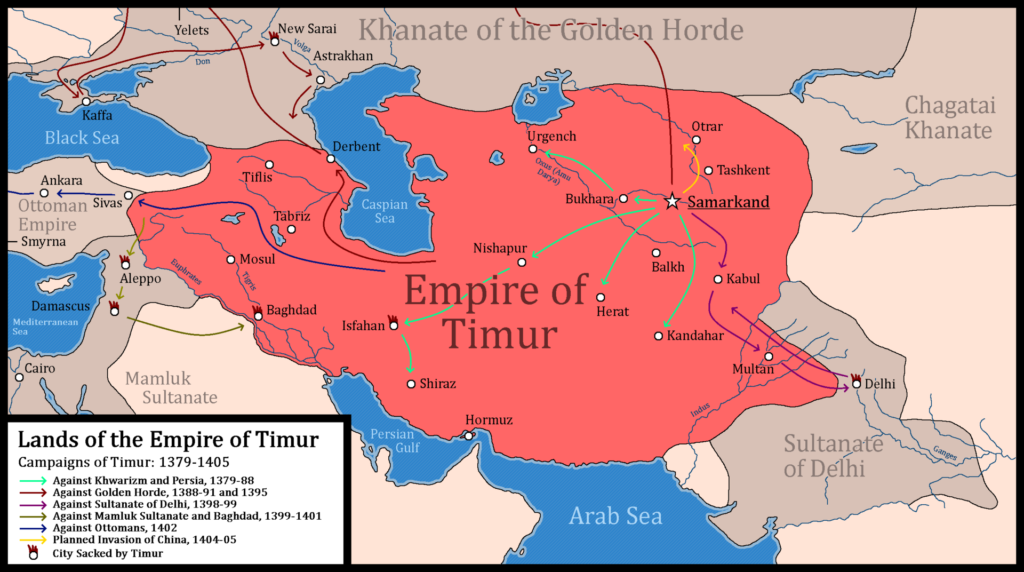

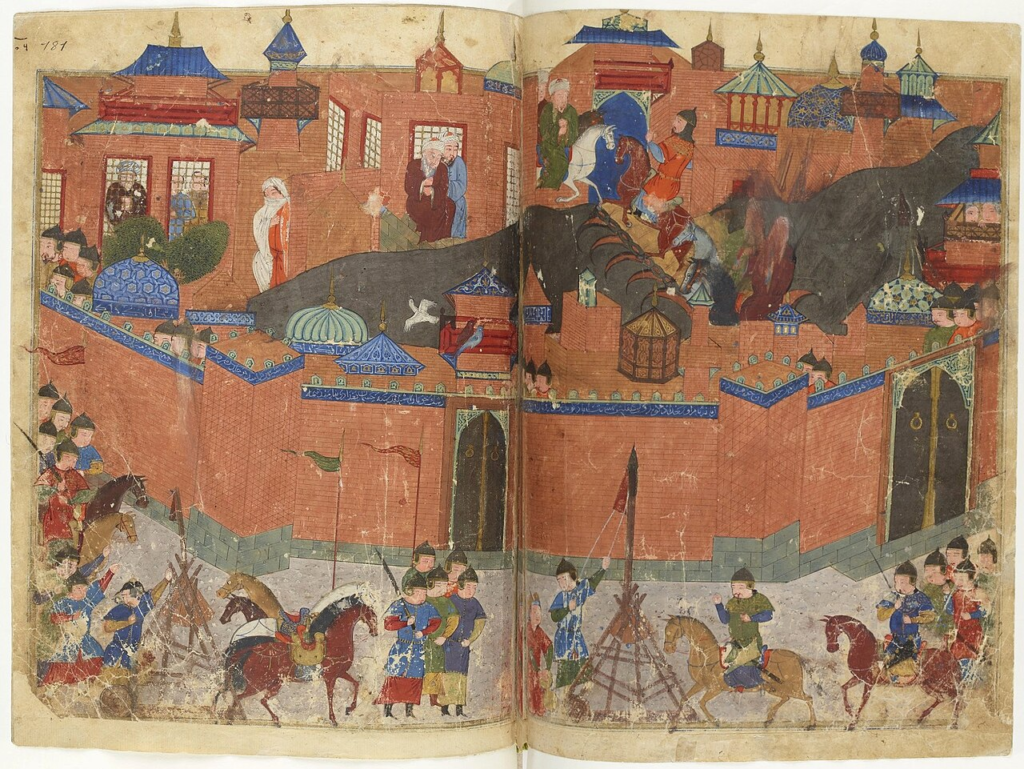

The Conquests of Timur (Tamerlane) (14th Century)

Timur waged brutal campaigns across Persia, India, the Middle East, and Central Asia, not to build a stable empire, but to plunder, destroy and assert dominance.

His conquests resulted in the deaths of an estimated 17 million people, often leaving entire cities in ruins.

Unlike empire-builders such as Genghis Khan, Timur seemed less interested in governance and more in demonstrating sheer military might.

Above: Mongol conqueror Timur (1320 – 1405)

The Armenian Genocide (1915-1917)

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Above: Flag of the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922)

Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through the mass murder of around one million Armenians during death marches to the Syrian Desert and the forced Islamization of others, primarily women and children.

Above: Emblem of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) (1889 – 1918)

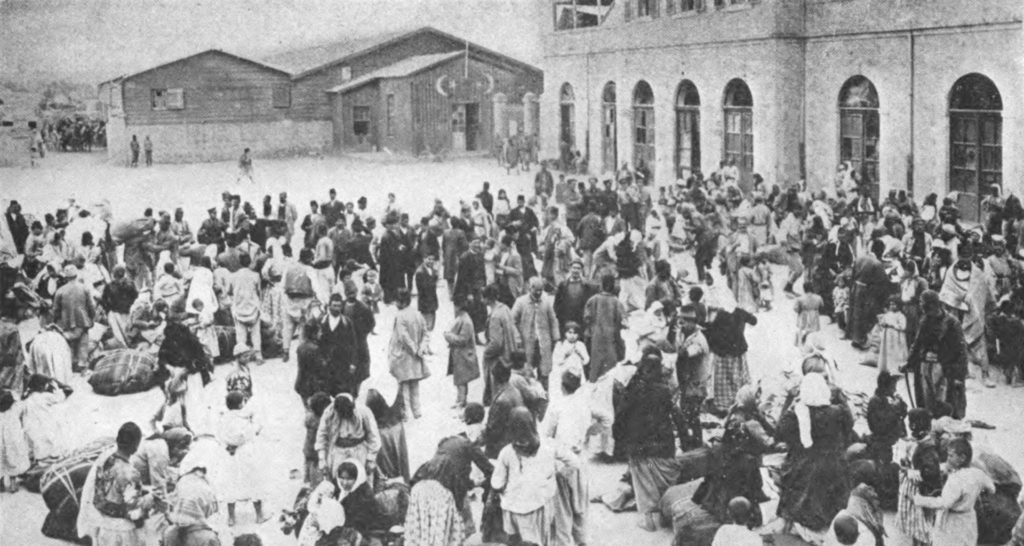

Before World War I, Armenians occupied a somewhat protected, but subordinate, place in Ottoman society.

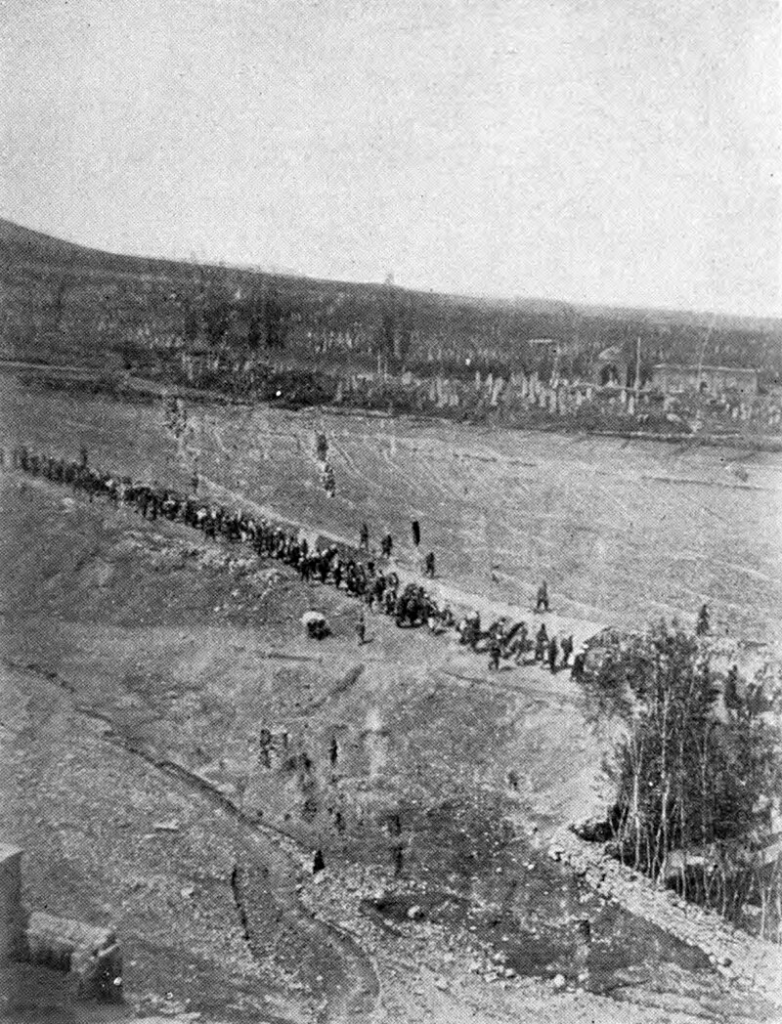

Above: A LONG LINE THAT SWIFTLY GREW SHORTER – Column of Armenian deportees guarded by gendarmes in Harput vilayet

31 December 1917

One of the most striking photographs of the deportations that have come out of Armenia.

Here is shown a column of Christians on the path across the great plains of the Mamuret-ul-Aziz.

The zaptieths are shown walking along at one side.

Large-scale massacres of Armenians had occurred in the 1890s and 1909.

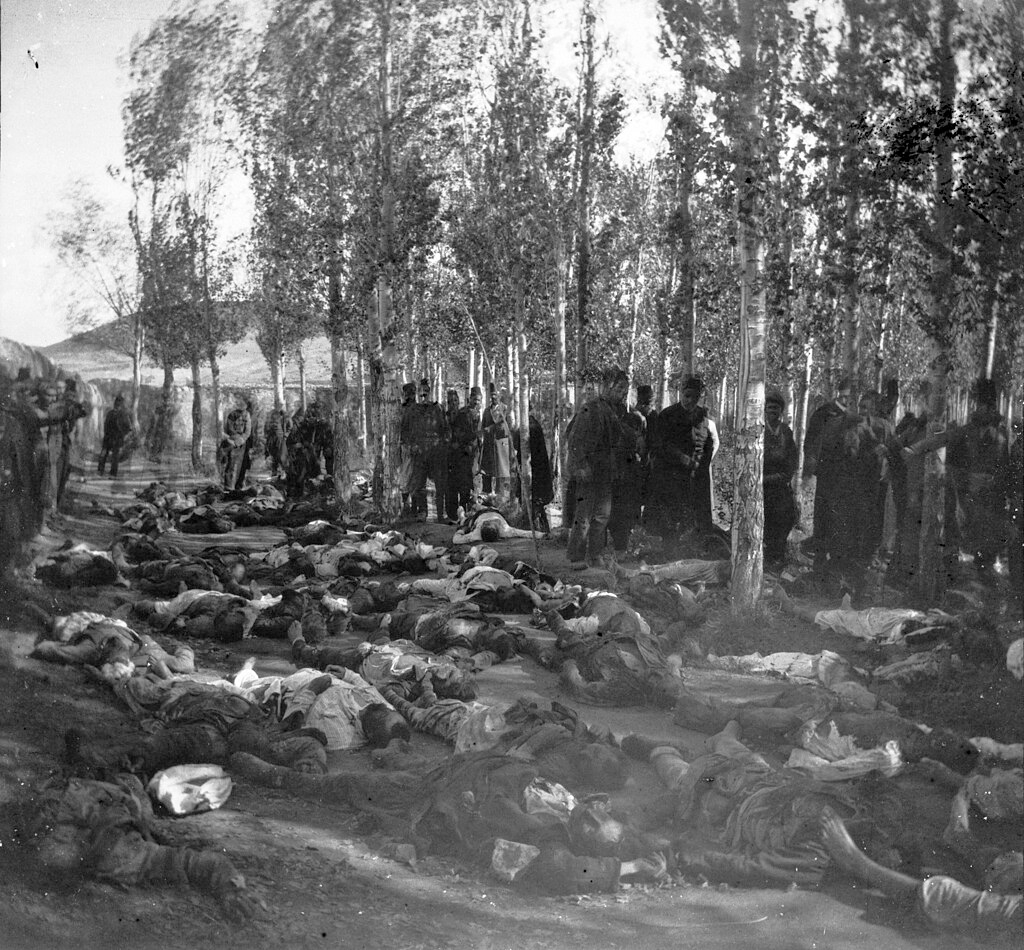

Above: The massacre at Erzeroum. The Graphic, 7 December 1895.

A photograph, taken by the American W. L. Sachtleben, depicting the victims of a massacre of Armenians in Erzerum on 30 October 1895, being gathered for burial at the town’s Armenian cemetery.

“What I myself saw this Friday afternoon 1 November is forever engraved on my mind as the most horrible sight a man can see.

I went with one of the cavasses of the English Legation, a soldier, my interpreter, and a photographer (Armenian) to the Armenian Gregorian cemetery.

The municipality had sent down a number of bodies, friends had brought more, and a horrible sight met my eyes.

Along the wall on the north …. lay 321 dead bodies of the massacred Armenians.

Many were fearfully mangled and mutilated.

I saw one with his face completely smashed in with a blow of some heavy weapon after he was killed.

I saw some with their necks almost severed by a sword cut.

One I saw whose whole chest had been skinned, his forearms were cut off, while the upper arm was skinned of flesh.

I asked if the dogs had done this.

‘No, the Turks did it with their knives‘.

A dozen bodies were half burned.

A crowd of a thousand people, mostly Armenians, watched me taking photographs of their dead.

Many were weeping beside their dead fathers or husbands.“

W. L. Sachtleben (1866 – 1953), London Times, 14 December 1895

The Hamidian massacres also called the Armenian massacres, were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1890s.

Estimated casualties ranged from 100,000 to 300,000, resulting in 50,000 orphaned children.

Above: Armenian victims of the massacres being buried in a mass grave at Erzerum cemetery, Harpers Weekly, 14 December 1895

The massacres are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who, in his efforts to maintain the imperial domain of the declining Ottoman Empire, reasserted pan-Islamism as a state ideology.

Above: Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1842 – 1918)

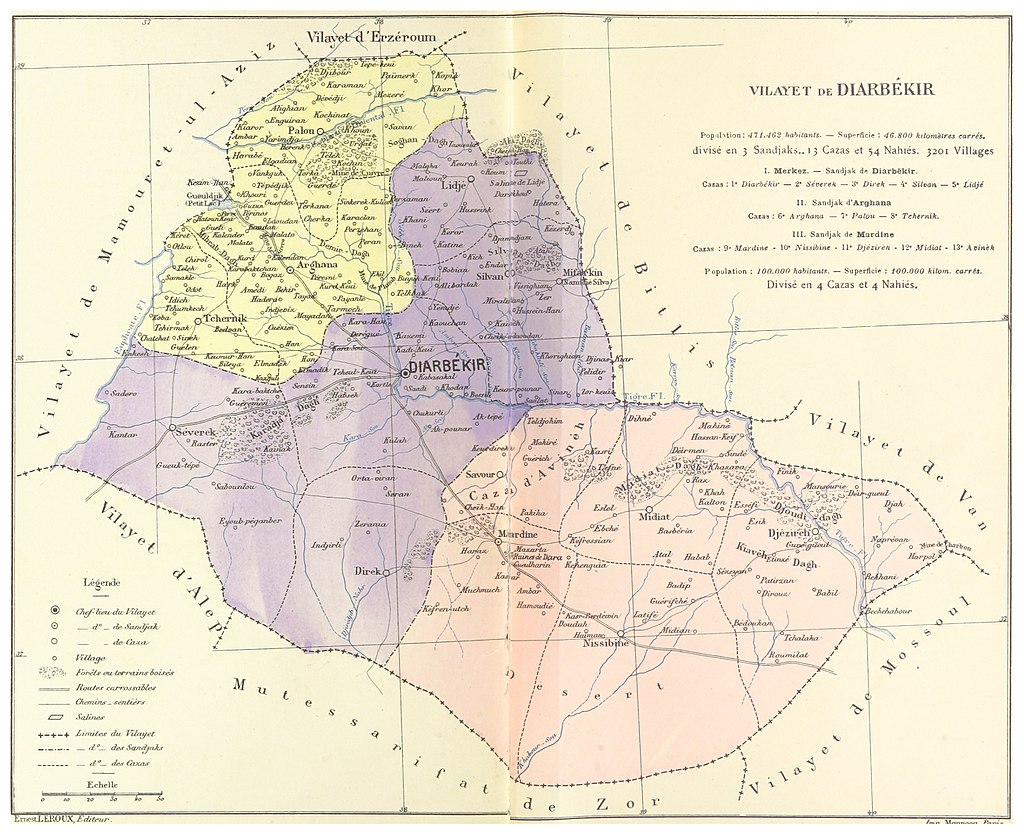

Although the massacres were aimed mainly at the Armenians, in some cases they turned into indiscriminate anti-Christian pogroms, including the Diyarbekır massacres, where, at least according to one contemporary source, up to 25,000 Assyrians were also killed.

Above: Diyarbakır Armenians

Especially in Diyarbakır, Armenian people had very serious influence on urban life and culture.

Their number was also high.

The Armenian population comprised 30% of the whole population in the city, which is not an insignificant statistic.

Above: Diyarbekır, Türkiye

In his travelogue the Seyâhatnâme, Evliya Çelebi said that Diyarbakır is also an Armenian city.

Above: Statue of Ottoman explorer Evliya Celebi (1611 – 1682)

According to him, as plenty of Armenians were settled there and left their mark on the culture, art, music, life styles and commerce of the city.

It is an Armenian city.

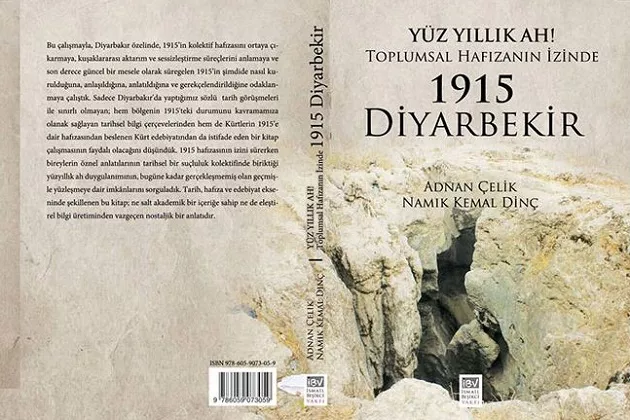

An important center of the Armenian genocide was Diyarbakır.

Both the urban Armenian population and the convoys passing through the city were massacred.

In their study “One Hundred Years of Sorrow – On the Track of Social Memory: 1915 Diyarbakır”, (“Yüzyıllık Ah! – Toplumsal Hafızanın İzinde: 1915 Diyarbekir”) published by the İsmail Beşikçi Foundation, Adnan Çelik and Namık Kemal Dinç searched for the specter of genocide haunting the city by drawing on intergenerational transmissions, political facts and the reflections of the genocide in Kurdish literature.

There are stories about children seized or hidden by others, but it is impossible to talk about families or men continuing their lives.

After the retreat of the Russian army, conflicts were experienced with the remaining Armenians, which led to mutual massacres.

Physically speaking, perhaps it was impossible to speak of Armenians in Diyarbakır anymore, but Islamized Armenians continued their existence considerably.

There are some church remnants, some properties left over by Armenians, yet Armenians themselves do not exist there anymore.

Why do people of Diyarbakır and Kurds remember the Armenian genocide so vividly?

Extreme forms of violence were implemented during the genocide.

This violence has been inscribed into the bodies, hearts and memories of people.

It is still traumatic that people have not been able to forget these violence narratives.

it is difficult to talk about it, but it is perhaps something inexpressible.

However, when one refers to the past practices of violence, the seriousness and the scale of the situation becomes apparent.

The majority of Armenian convoys brought from the north during the genocide passed through Diyarbakır and Mardin.

Many killings were perpetrated in the province of Diyarbakır.

Some places where people were killed are now associated with this slaughter.

The memories of these places had a great impact upon people.

These are desolate places.

These are places out of sight.

Places where it is possible to rapidly and easily make the bodies of killed people disappear.

Chasms, caves, pits, straits, cisterns…

There were many Armenians in Diyarbakır who were able to survive.

Some of them were Islamized and some of them continued their daily existence in their own religion.

Above: Diyarbekır Vilayet (1867 – 1922)

The massacres began in the Ottoman interior in 1894, before they became more widespread in the following years.

The majority of the murders took place between 1894 and 1896.

The massacres began to taper off in 1897, following international condemnation of Abdul Hamid.

The harshest measures were directed against the long persecuted Armenian community as its calls for civil reform and better treatment were ignored by the government.

The Ottomans made no allowances for the victims on account of their age or gender.

As a result, they massacred all of the victims with brutal force.

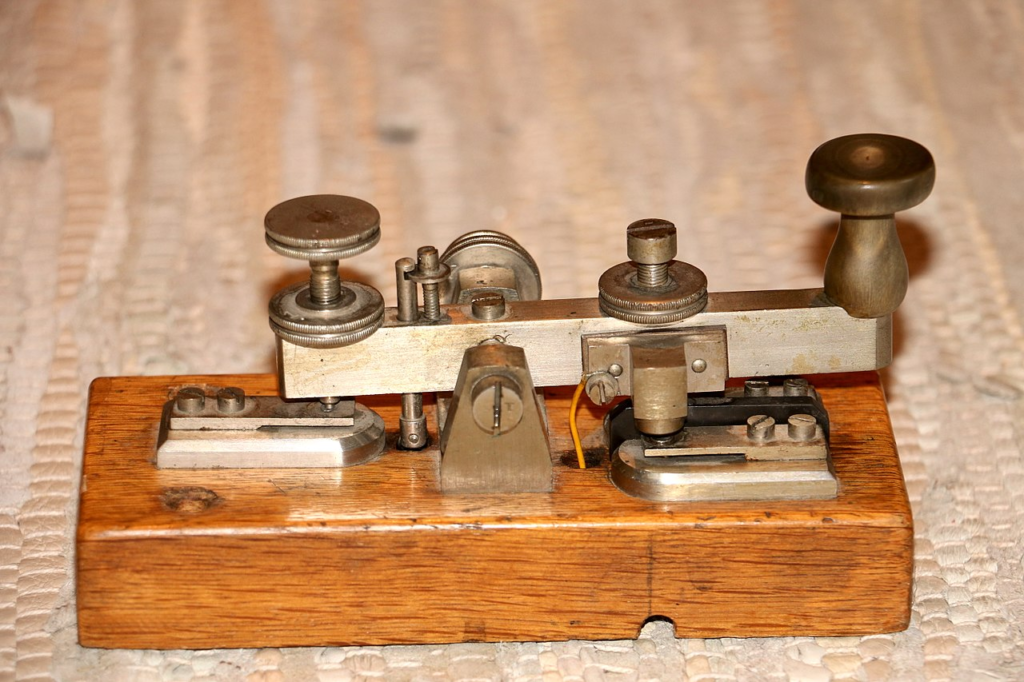

The telegraph spread news of the massacres around the world, leading to a significant amount of coverage of them in the media of Western Europe, Russia and North America.

Above: Morse telegraph

The Adana massacres occurred in the Adana Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire in April of 1909.

Many Armenians were slain by Ottoman Muslims in the city of Adana as the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 triggered a series of pogroms throughout the province.

Around 20,000 to 25,000 ethnic Armenians were killed and tortured in Adana and surrounding towns, it was reported that about 1,300 Assyrians were also killed during the massacres.

Unlike the previous Hamidian massacres, the events were not officially organized by the central government, but culturally instigated via local officials, Islamic clerics, and supporters of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).

After the Hamidian massacres, the Great Powers (Britain, France, Russia) forced Hamid to sign a new reform package designed to curtail the powers of the Hamidiye in October 1895 which, like the Berlin treaty, was never implemented.

On 1 October 1895, two thousand Armenians assembled in Constantinople (Istanbul) to petition for the implementation of the reforms, but Ottoman police units converged on the rally and violently broke it up.

Upon receiving the reform package, the Sultan is said to have remarked:

“This business will end in blood.“

After revolutionary groups had secured the deposition of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the restoration of the Second Constitutional Era (Ottoman Empire) in 1908, a military revolt directed against the Committee of Union and Progress seized Constantinople.

While the revolt lasted only ten days, it reignited anti-Armenian sentiment in the region and precipitated the mass destruction of Armenian businesses and farms, public hangings, sexual violence, and executions rooted in political, economic and religious prejudice.

These massacres continued for more than one month.

The Armenian quarter of Adana was described as the “richest and most prosperous“.

The violence included destruction of “tractors and other kinds of mechanized equipment“.

Above: Adana – Christian Quarter, 1 June 1909

The Ottoman Empire suffered a series of military defeats and territorial losses — especially during the 1912–1913 Balkan Wars —leading to fear among CUP leaders that the Armenians would seek independence.

Above: A Bulgarian postcard depicting the Battle of Lule Burgas

28 October – 2 November 1912

During their invasion of Russian and Persian territory in 1914, Ottoman paramilitaries massacred local Armenians.

Ottoman leaders took isolated instances of Armenian resistance as evidence of a widespread rebellion, though no such rebellion existed.

Mass deportation was intended to permanently forestall the possibility of Armenian autonomy or independence.

Above: A poor, widowed Armenian woman and her children, Makarid (on her back) and Nuvart (standing next to her).

In 1899, after the murder of her husband in the aftermath of the Armenian Massacres of 1894 – 1896, the family walked from their home in the Geghi region to Kharpert (Harput), eastern Anatolia (Turkey) seeking help from missionaries.

On 24 April 1915, the Ottoman authorities arrested and deported hundreds of Armenian intellectuals and leaders from Constantinople (Istanbul).

At the orders of Talaat Pasha, an estimated 800,000 to 1.2 million Armenians were sent on death marches to the Syrian Desert in 1915 and 1916.

Above: Grand Vizier Mehmet Tâlat (1874 – 1921)

Driven forward by paramilitary escorts, the deportees were deprived of food and water and subjected to robbery, rape and massacres.

In the Syrian Desert, the survivors were dispersed into concentration camps.

In 1916, another wave of massacres was ordered, leaving about 200,000 deportees alive by the end of the year.

Around 100,000 to 200,000 Armenian women and children were forcibly converted to Islam and integrated into Muslim households.

Massacres and ethnic cleansing of Armenian survivors continued through the Turkish War of Independence (1919 – 1923) after World War I (1914 – 1918), carried out by Turkish nationalists.

Above: Armenians gathered in a city prior to deportation.

They were murdered outside the city.

This genocide put an end to more than 2,000 years of Armenian civilization in eastern Anatolia.

Together with the mass murder and expulsion of Assyrian/Syriac and Greek Orthodox Christians, it enabled the creation of an ethnonationalist Turkish state, the Republic of Turkey.

Above: The corpses of Armenians beside a road, a common sight along deportation routes – 31 December 1917

Image taken from Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, written by Henry Morgenthau, Sr. and published in 1918.

Original description:

“THOSE WHO FELL BY THE WAYSIDE.

Scenes like this were common all over the Armenian provinces, in the spring and summer months of 1915.

Death in its several forms — massacre, starvation, exhaustion —destroyed the larger part of the refugees.

The Turkish policy was that of extermination under the guise of deportation”

The Ottoman Empire tried to prevent journalists and photographers from documenting the atrocities, threatening them with arrest.

Nevertheless, substantiated reports of mass killings were widely covered in Western newspapers.

On 24 May 1915, the Triple Entente (Russia, Britain, and France) formally condemned the Ottoman Empire for “crimes against humanity and civilization“, and threatened to hold the perpetrators accountable.

Witness testimony was published in books such as The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire (1916) and Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story (1918), raising public awareness of the genocide.

The German Empire was a military ally of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

German diplomats approved limited removals of Armenians in early 1915, and took no action against the genocide, which has been a source of controversy.

Above: Flag of Germany (1867 – 1918)

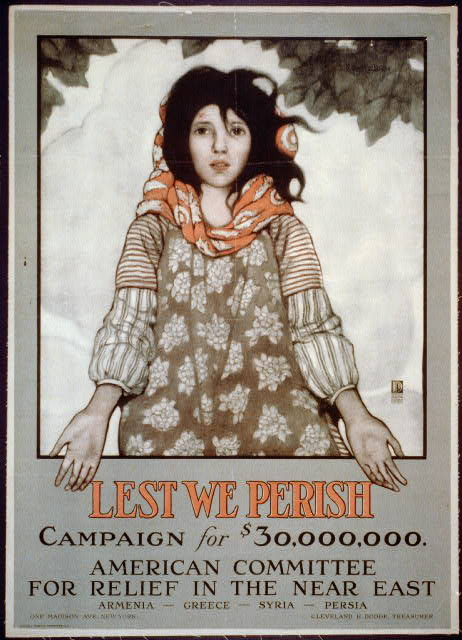

Relief efforts were organized in dozens of countries to raise money for Armenian survivors.

By 1925, people in 49 countries were organizing “Golden Rule Sundays” during which they consumed the diet of Armenian refugees, to raise money for humanitarian efforts.

Between 1915 and 1930, Near East Relief raised $110 million ($2 billion adjusted for inflation) for refugees from the Ottoman Empire.

The Turkish government maintains that the deportation of Armenians was a legitimate action that cannot be described as genocide.

The Turkish state perceives open discussion of the genocide as a threat to national security because of its connection with the foundation of the Republic, and for decades strictly censored it.

In 2002, the AK Party came to power and relaxed censorship to a certain extent.

Above: Justice and Development Party logo

The profile of the issue was raised by the 2007 assassination of Hrant Dink, a Turkish-Armenian journalist known for his advocacy of reconciliation.

Above: Hrant Dink (1954 – 2007)

Although the AK Party softened the state denial rhetoric, describing Armenians as part of the Ottoman Empire’s war losses, during the 2010s political repression and censorship increased again.

Turkey’s century-long effort to prevent any recognition or mention of the genocide in foreign countries has included millions of dollars in lobbying, as well as intimidation and threats.

As of 2025, 34 countries have recognized the events as genocide, concurring with the academic consensus.

The genocide is extensively documented in the archives of Germany, Austria, the United States, Russia, France, and the United Kingdom, as well as the Ottoman archives, despite systematic purges of incriminating documents by Turkey.

There are also thousands of eyewitness accounts from Western missionaries and Armenian survivors.

Above: Monument to Humanity, Kars, Türkiye, commemorating the Armenian Genocide was demolished one month after it was constructed.

Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide in 1944, became interested in war crimes after reading about the 1921 trial of Soghomon Tehlirian for the assassination of Talaat Pasha.

Lemkin recognized the fate of the Armenians as one of the most significant genocides in the 20th century.

Above: Raphael Lemkin (1900 – 1959)

Almost all historians and scholars outside Turkey, and an increasing number of Turkish scholars, recognize the destruction of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire as genocide.

The Ottoman Empire systematically exterminated 1.5 million Armenians through mass killings, forced marches, and starvation.

This was not a war for territory but a deliberate attempt to erase an ethnic group.

The genocide was driven by nationalist paranoia, not strategic necessity.

Above: Coat of arms of the Ottoman Empire

A country facing up to its historical wrongs isn’t about self-flagellation but about growth, reconciliation, and setting the moral foundations for the future.

A nation’s strength lies in its ability to confront the truth.

Denial distorts history and weakens moral authority.

Germany has gained global respect for facing its past.

Japan’s refusal to fully acknowledge its wartime atrocities has hindered relations with its neighbors.

Acknowledging past wrongs allows for reconciliation.

When Germany accepted responsibility, it fostered better relations with former adversaries, including France, Israel, and Poland.

Türkiye, by acknowledging the Armenian Genocide, could improve diplomatic ties with Armenia and other nations.

Denial creates internal and external divisions.

Recognition can help unite people by acknowledging shared pain and fostering a collective sense of justice.

Admitting past crimes ensures that history is not forgotten or repeated.

Germany’s commitment to Holocaust education has made it a leader in human rights advocacy.

Rather than framing it as guilt or blame, Türkiye could present recognition as a step toward healing a shared history of suffering.

A narrative like:

“In the chaos of war, terrible things happened to many, including Armenians, and we acknowledge this pain and loss.“

Without necessarily using the word “genocide” (if politically impossible), Türkiye could hold ceremonies or build memorials honoring Armenian victims — similar to Japan’s partial apologies to Korea and China.

Rather than a sudden declaration, Türkiye could slowly shift its stance, beginning with humanitarian recognition of suffering and gradually adopting stronger statements over time.

Recognition shouldn’t be about weakness or shame but about Türkiye’s maturity and strength as a modern nation, unafraid of truth and committed to justice.

Would this approach work in Türkiye’s current political climate?

That’s another challenge entirely, but history shows that nations that face their past with honesty often emerge stronger.

The Holocaust (1941 – 1945)

Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe.

The Holocaust saw the murder of 90% of Polish Jews and two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe.

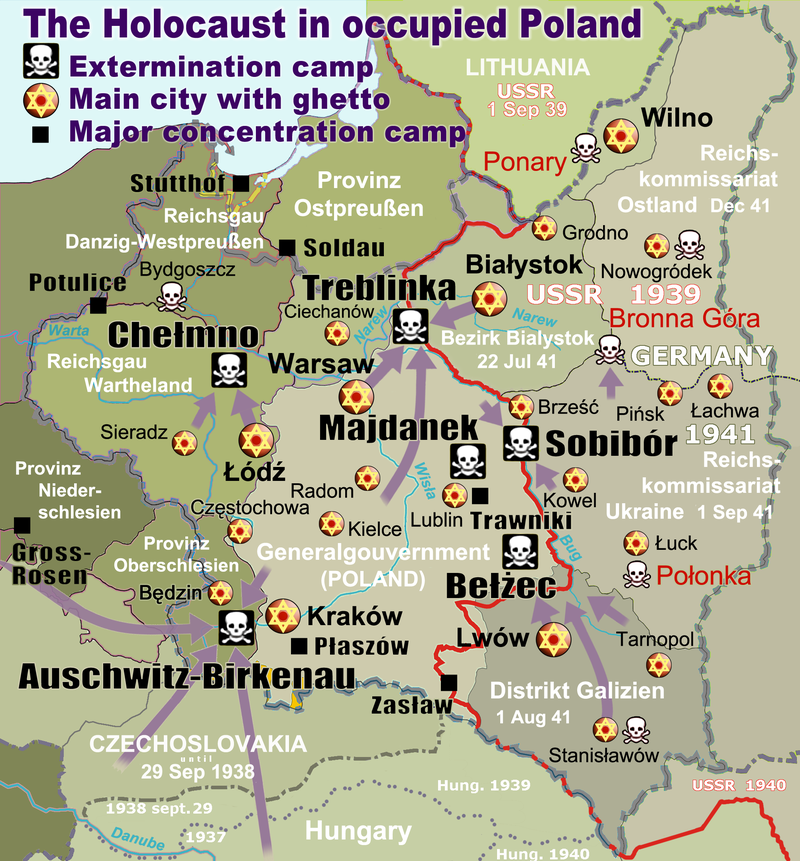

The murders were carried out primarily through mass shootings and poison gas in extermination camps, chiefly Auschwitz -Birkenau, Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor and Chełmno in occupied Poland.

Above: “Selection” of Hungarian Jews on the ramp at Auschwitz II -Birkenau in German-occupied Poland, May/June 1944, during the final phase of the Holocaust.

Jews were sent either to work or to the gas chamber.

The photograph is part of the collection known as the Auschwitz Album, which was donated to Yad Vashem by Lili Jacob, a survivor, who found it in the Mittelbau – Dora concentration camp in 1945.

Yad Vashem:

“The Auschwitz Album is the only surviving visual evidence of the process leading to mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau.”

The collection was first published as The Auschwitz Album in 1980 in the United States, Canada and elsewhere, by the Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, but individual images had been published before that — for example, during the 1947 Auschwitz trial in Poland and the 1963–1965 Frankfurt Auschwitz trials.

It is not known when this particular image was first published.

Separate Nazi persecutions killed a similar or larger number of non-Jewish civilians and prisoners of war (POWs).

The Nazis developed their ideology based on racism and pursuit of “living space“, and seized power in early 1933.

Above: German dictator Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945)

Meant to force all German Jews to emigrate, regardless of means, the regime passed anti-Jewish laws, encouraged harassment, and orchestrated a nationwide pogrom in November 1938.

Above: Members of the Sturmabteilung installing a sign on the front window of a Jewish-owned store in Berlin on 1 April 1933, as part of the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, which the Nazi Party claimed was in response to the 1933 anti-Nazi boycott.

The sign reads:

“Germans! Defend yourselves, do not buy from the Jews!“

After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, occupation authorities began to establish ghettos to segregate Jews.

Above: Images of the German invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939)

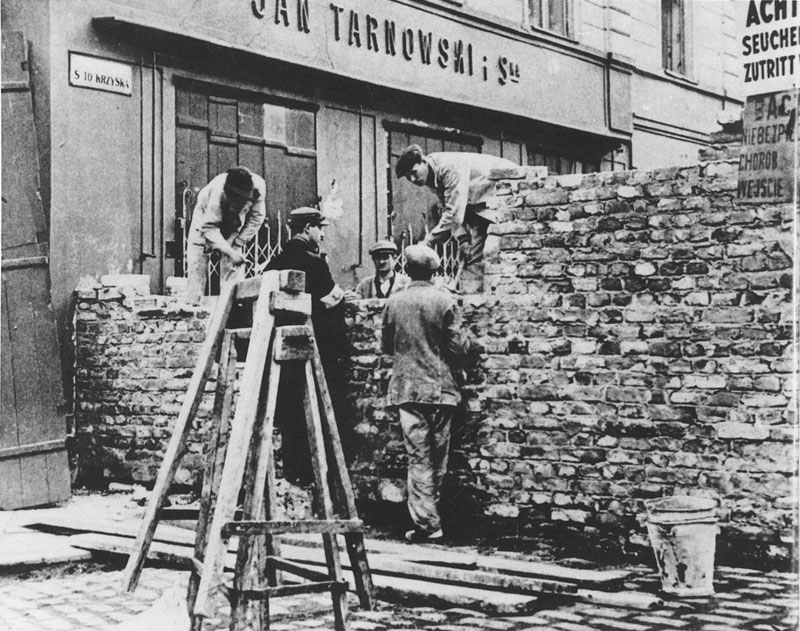

Above: Warsaw Ghetto (1940 – 1943) during the German occupation of Poland: Construction of Ghetto wall across Świętokrzyska Street near intersection with Marszałkowska Street – August 1940

Following the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, 1.5 to 2 million Jews were shot by German forces and local collaborators.

Above: Images of the German invasion of Russia – Operation Barbarossa (22 June – 5 December 1941)

By early 1942, the Nazis decided to murder all Jews in Europe.

Above: Hitler’s prophecy speech – 30 January 1939

Hitler accused Jews of having “nothing of their own, except for political and sanitary diseases” and being parasites on the German nation, turning Germans into “beggars in their own country“.

He asserted there had to be an end to the misconception that “the good Lord had meant the Jewish nation to live off the body and productive work of other nations“, or else the Jews would “succumb to a crisis of unimaginable severity“.

Hitler claimed that the Jews were trying to incite “millions among the masses of people into a conflict that is utterly senseless for them and serves only Jewish interests“.

Hitler then arrived at his main point:

I have very often in my lifetime been a prophet and have been mostly derided.

At the time of my struggle for power it was in the first instance the Jewish people who only greeted with laughter my prophecies that I would someday take over the leadership of the state and of the entire people of Germany and then, among other things, also bring the Jewish problem to its solution.

I believe that this hollow laughter of Jewry in Germany has already stuck in its throat.

I want today to be a prophet again:

If international finance Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, the result will be not the Bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.”

The term “Final Solution” was a euphemism used by the Nazis to refer to their plan for the annihilation of the Jewish people.

Broadly speaking, the extermination of Jews was carried out in two major operations.

With the onset of Operation Barbarossa, mobile killing units of the SS, the Einsatzgruppen, and Order Police battalions were dispatched to the occupied Soviet Union for the express purpose of murdering all Jews.

During the early stages of the invasion, Himmler himself visited Białystok at the beginning of July 1941, and requested that, “as a matter of principle, any Jew” behind the German-Soviet frontier was to be “regarded as a partisan“.

His new orders gave the SS and police leaders full authority for the mass murder behind the front lines.

By August 1941, all Jewish men, women and children were shot.

Above: Heinrich Himmler (1900 – 1945)

In the second phase of annihilation, the Jewish inhabitants of central, western, and southeastern Europe were transported by Holocaust trains to camps with newly built gassing facilities.

Raul Hilberg wrote:

“In essence, the killers of the occupied USSR moved to the victims, whereas outside this arena, the victims were brought to the killers.

The two operations constitute an evolution not only chronologically, but also in complexity.“

Massacres of about one million Jews occurred before plans for the Final Solution were fully implemented in 1942, but it was only with the decision to annihilate the entire Jewish population that extermination camps such as Auschwitz II Birkenau and Treblinka were fitted with permanent gas chambers to murder large numbers of Jews in a relatively short period of time.

Above: Gas chamber at Majdanek concentration camp, Lublin, Poland

The plans to exterminate all the Jews of Europe were formalized at the Wannsee Conference, held at an SS guesthouse near Berlin, on 20 January 1942.

The conference was chaired by Heydrich and attended by 15 senior officials of the Nazi Party and the German government.

Above: Reinhard Heydrich (1904 – 1942)

Most of those attending were representatives of the Interior Ministry, the Foreign Ministry and the Justice Ministry, including Ministers for the Eastern Territories.

At the conference, Heydrich indicated that approximately 11,000,000 Jews in Europe would fall under the provisions of the “Final Solution“.

This figure included not only Jews residing in Axis-controlled Europe, but also the Jewish populations of the United Kingdom and of neutral nations (Switzerland, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, and European Turkey).

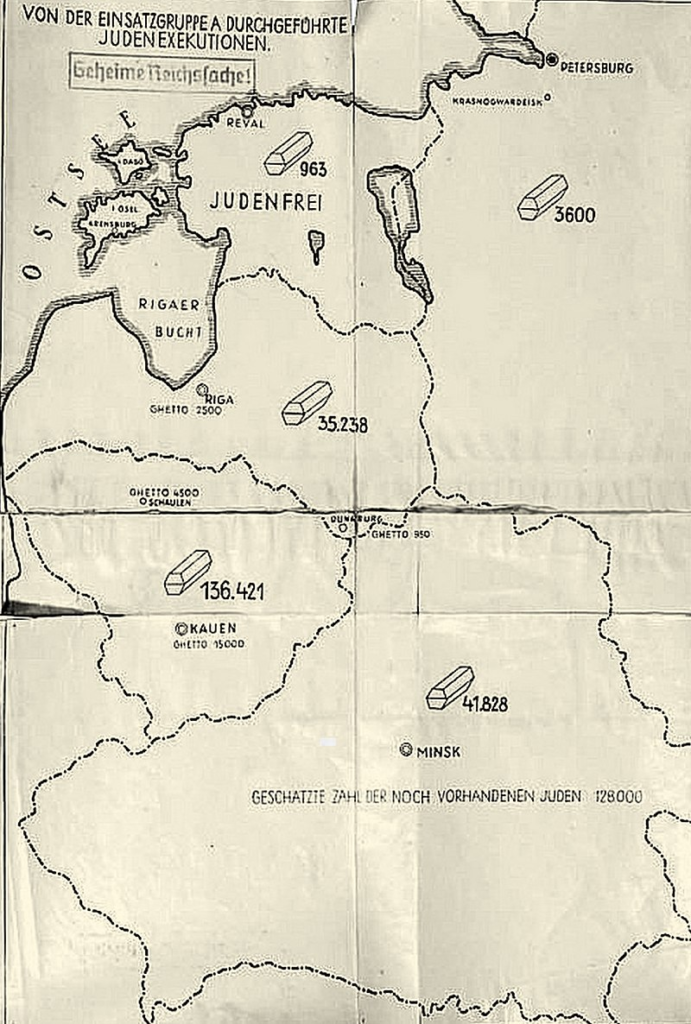

Above: Original annotated map from Franz Walter Stahlecker’s (1900 – 1942) report, summarizing murders committed by Einsatzgruppen in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus and Russia until January 1942

Eichmann’s biographer David Cesarani wrote that Heydrich’s main purpose in convening the conference was to assert his authority over the various agencies dealing with Jewish issues.

“The simplest, most decisive way that Heydrich could ensure the smooth flow of deportations” to death camps, according to Cesarani, “was by asserting his total control over the fate of the Jews in the Reich and the east” under the single authority of the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office / “Reichssicherheitshauptamt“) .

Above: Adolf Eichmann (1906 – 1962)

A copy of the minutes of this meeting (later called the Wannsee Conference Protocol) was found by the Allies in March 1947.

It was too late to serve as evidence during the first Nuremberg Trial, but was used by prosecutor General Telford Taylor (1908 – 1998) in the subsequent Nuremberg Trials (1945 – 1946).

Above: The villa at 56–58 Am Großen Wannsee, where the Wannsee Conference (20 January 1942) was held, is now a memorial and museum.

Victims were deported to extermination camps where those who had survived the trip were killed with poisonous gas, while others were sent to forced labor camps where many died from starvation, abuse, exhaustion, or being used as test subjects in experiments.

Above: Original Nazi propaganda caption: – “A 14-year-old youth from Ukraine repairs damaged motor vehicles in a Berlin workshop of the German Wehrmacht. January 1945.”

Property belonging to murdered Jews was redistributed to the German occupiers and other non-Jews.

Above: Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, 23 April 1945