Eskişehir, Türkiye

Thursday 13 February 2025

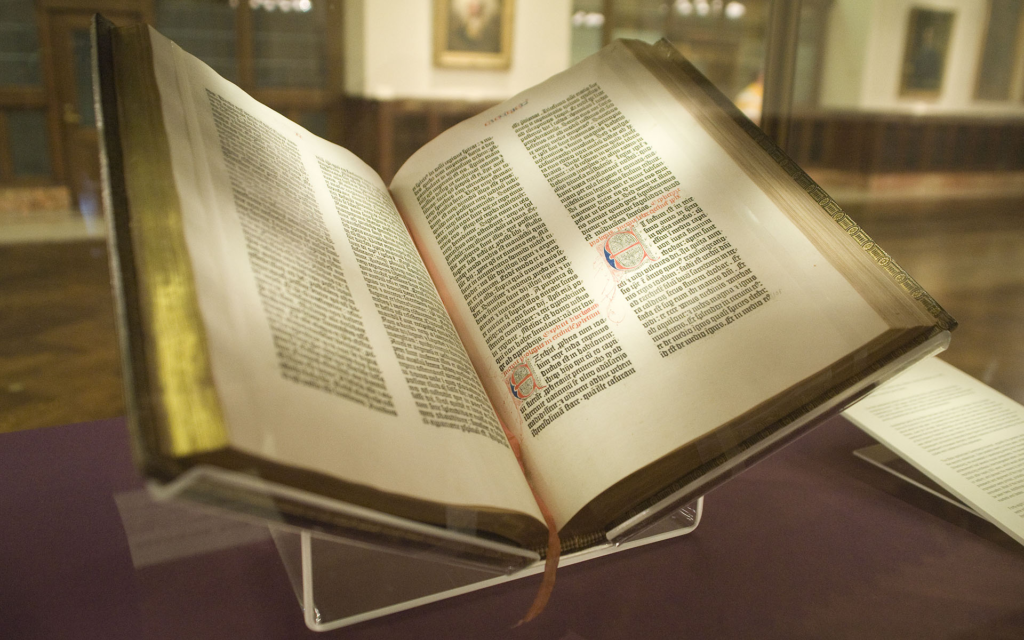

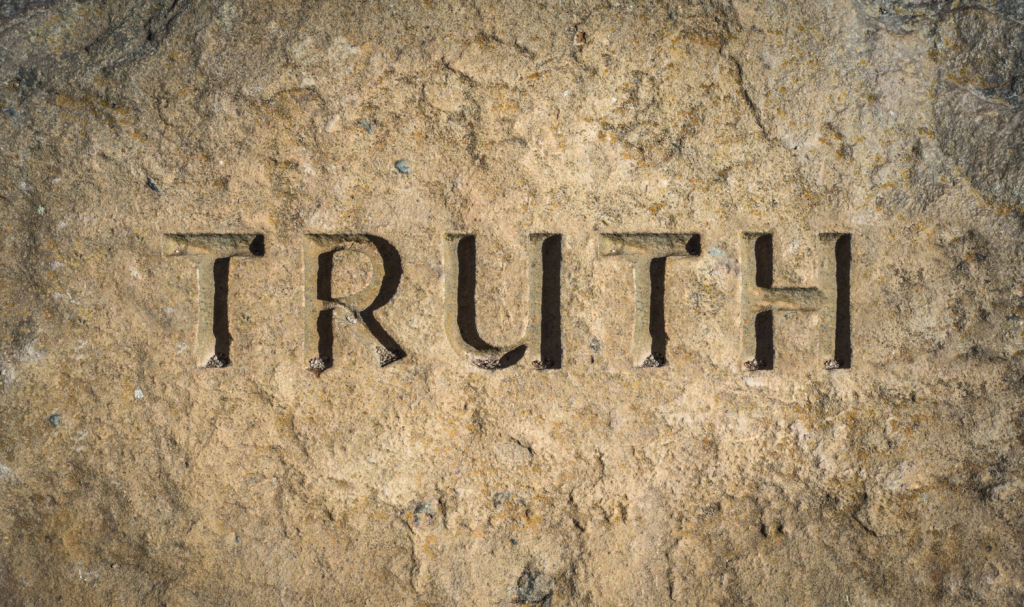

A hand, trembling, rests upon the worn leather of a Bible.

A voice, heavy with authority, asks:

“Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?“

A moment of hesitation.

A flicker of doubt.

The weight of the words presses down, demanding not just honesty but completeness.

Tasks often too great for the frailties of human nature.

Dear readers, I have been lying to you.

But, in full disclosure, I have been lying to myself as well, if not more.

The dateline reads 13 February, but the actual date that I am typing these words onto the screen will be later than the dateline.

Why?

Because this blog has been evolving.

The value of this blog is in the depth of the insights uncovered, not in rigid adherence to the calendar.

Truth, as we are exploring, is timeless — and so is the act of discovering it.

Whether I reveal the lessons of February 13 on that day or later, what matters is the meaning extracted, not the date stamped upon it.

This also frees me creatively.

Instead of racing to keep pace with the calendar, I can allow each entry to evolve naturally, giving it the space it needs.

The blog becomes a living, breathing chronicle — not a daily log, but something more – an ongoing conversation between past, present, and reflection.

A blog should serve the blogger, not the other way around.

If keeping it chronologically in sync has become a way to avoid deeper, necessary reflections on my life, then releasing myself from that constraint is a step toward reclaiming control — both of my writing and of my future.

Perhaps today‘s theme of truth and illusion is even more personal than I have initially thought.

Just as nations, businesses, and individuals tell themselves stories to avoid discomfort, I recognize that staying engrossed in historical exploration has, in some ways, shielded you from facing my own crossroads.

That’s a powerful insight.

So, let’s embrace flexibility.

I will continue to try and craft my posts with deliberate reflection, balancing them with the broader personal and professional decisions that also require my attention.

The Chronicles of Canada Slim is no longer just a blog.

It is the unfolding of a greater narrative, a novel-in-progress that captures my thoughts, my voice, and my evolution as both a writer and a man.

Each post, each reflection, is a chapter in that larger story, one that doesn’t need to be rushed or bound by arbitrary constraints.

It grows organically, deepening in meaning over time.

And yes, this practice is invaluable.

It sharpens my writing, builds my presence, and, most importantly, reveals my self to myself.

Writing, at its best, is an act of self-discovery — and perhaps through this ongoing conversation with the world (and with yourself), I will find the truth that will, in time, set men free.

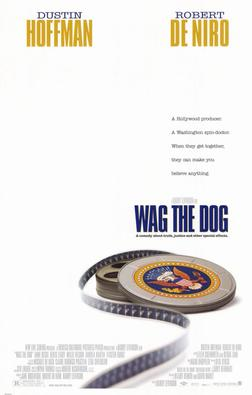

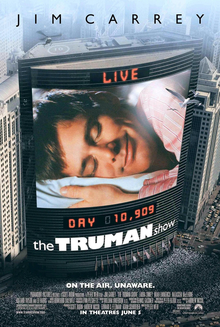

A Few Good Men is a 1992 American legal drama film based on Aaron Sorkin’s 1989 play.

The plot follows the court martial of two US Marines charged with the murder of a fellow Marine and the tribulations of their lawyers as they prepare a case.

At the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba, Private William Santiago (Michael DeLorenzo), a United States Marine, is tied up and beaten in the middle of the night.

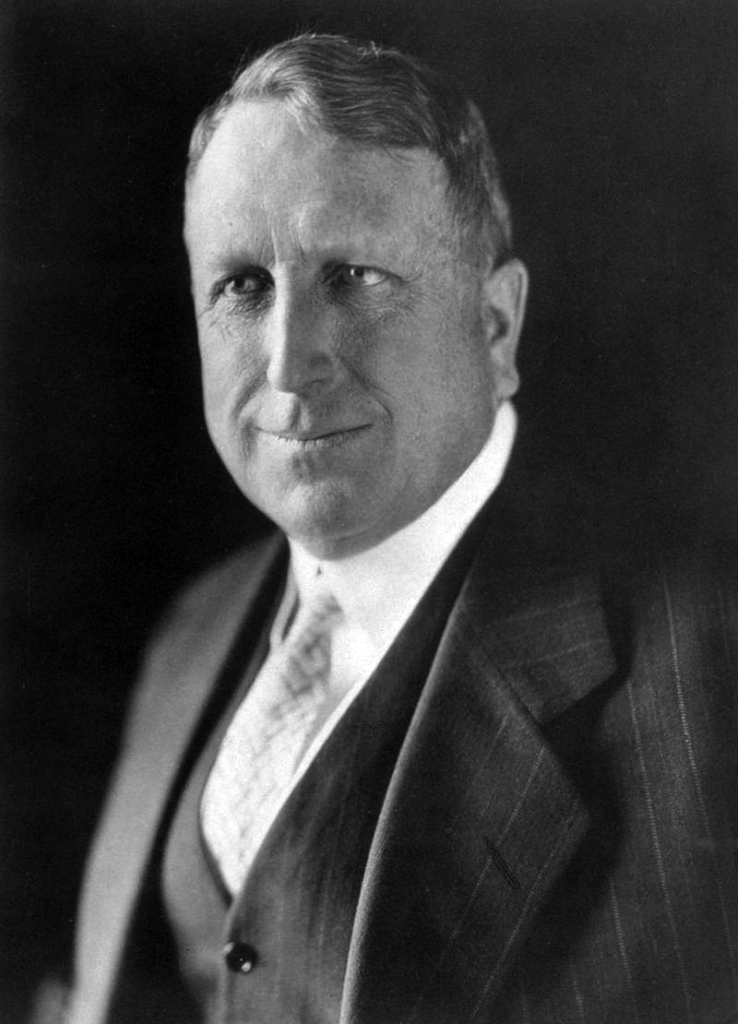

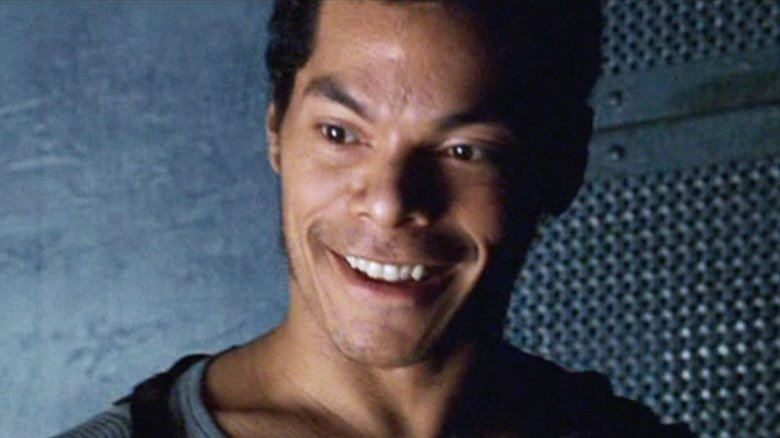

Above: American actor Michael DeLorenzo

After he is found dead, Lance Corporal Harold Dawson (Wolfgang Bodison) and Private First Class Louden Downey (James Marshall) are accused of his murder and face a court martial.

Above: American actor Wolfgang Bodison

Above: American actor James Marshall

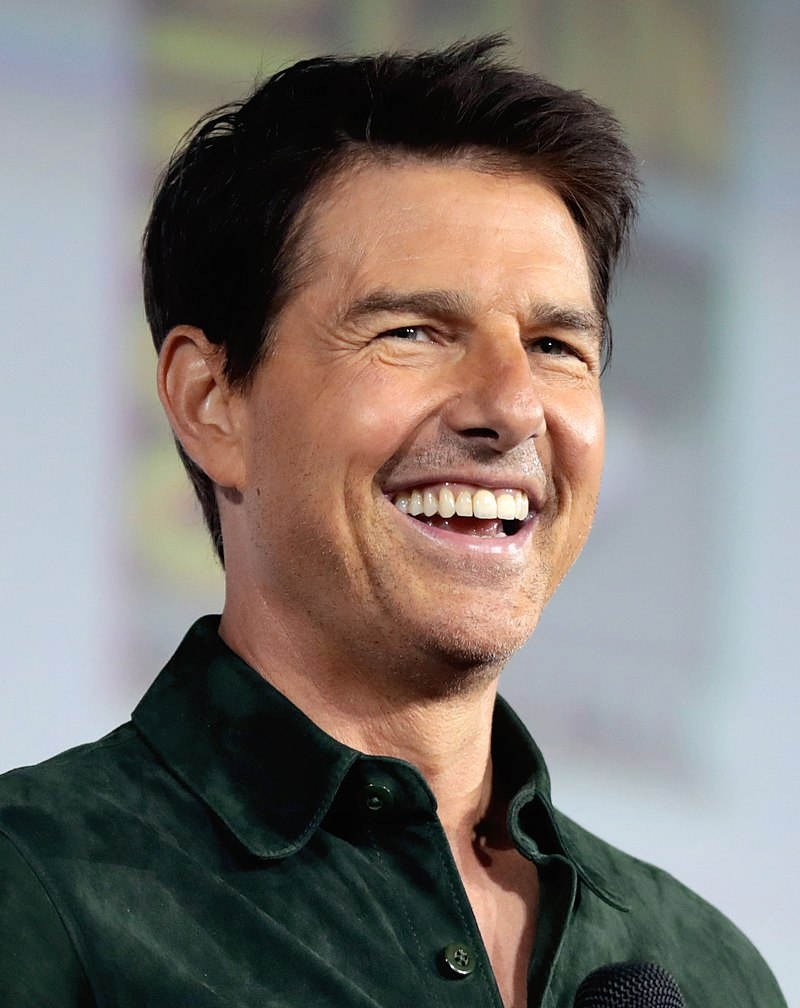

Their defense is assigned to United States Navy JAG Corps Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise), a callow lawyer with a penchant for plea bargains.

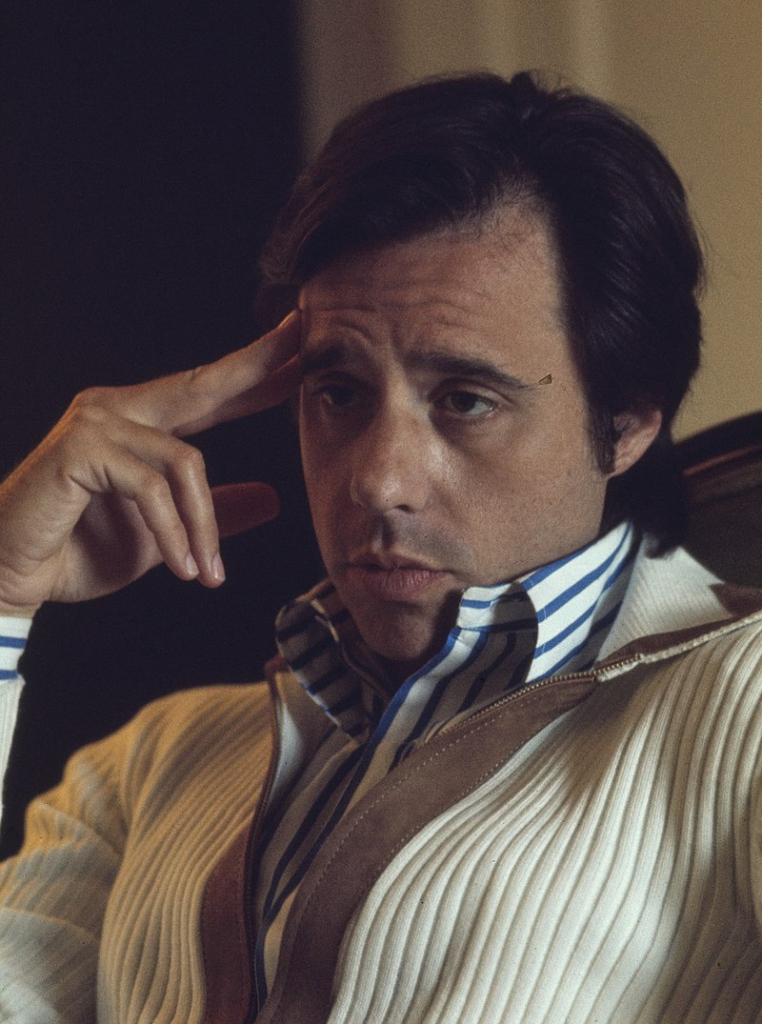

Above: American actor Tom Cruise

Another JAG attorney, Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway (Demi Moore), Kaffee’s superior, suspects something is amiss.

Above: American actress Demi Moore

Santiago died after he broke the chain of command to ask to be transferred away.

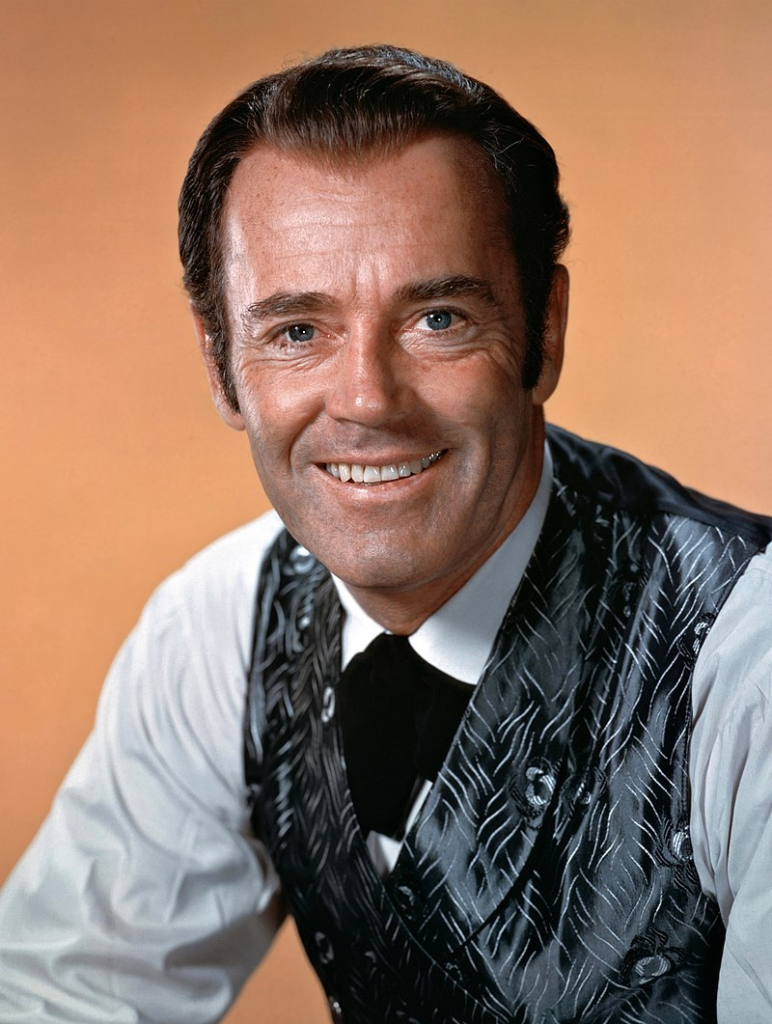

Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Markinson (J. T. Walsh) advocated for Santiago to be transferred, but Base Commander Colonel Nathan Jessep (Jack Nicholson) ordered Santiago’s platoon commander, Lieutenant Jonathan James Kendrick (Kiefer Sutherland), to “train” Santiago on the basis they are all at fault for Santiago’s substandard performance.

Above: Lieutenant Colonel rank insignia for the US Army, Air Force and Marine Corps

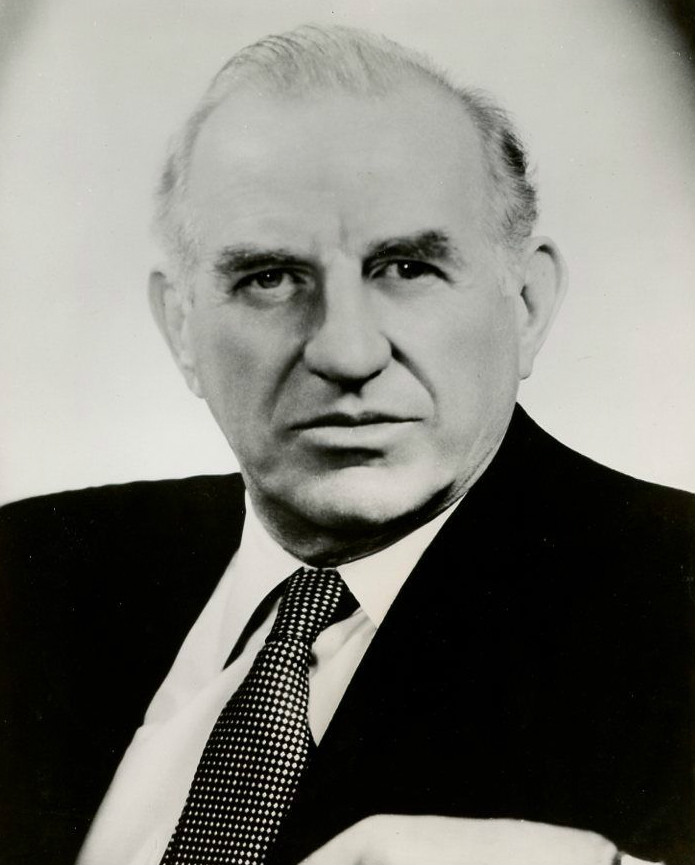

Above: American actor James Thomas Walsh (1943 – 1998)

Above: American actor Jack Nicholson

Above: Canadian actor Kiefer Sutherland

Galloway suspects that Dawson and Downey carried out a “code red” order:

A violent extrajudicial punishment.

Galloway is bothered by Kaffee’s blasé approach.

Kaffee resents Galloway’s interference.

Kaffee and Galloway question Jessep and others at Guantanamo Bay and are met with contempt from the Colonel.

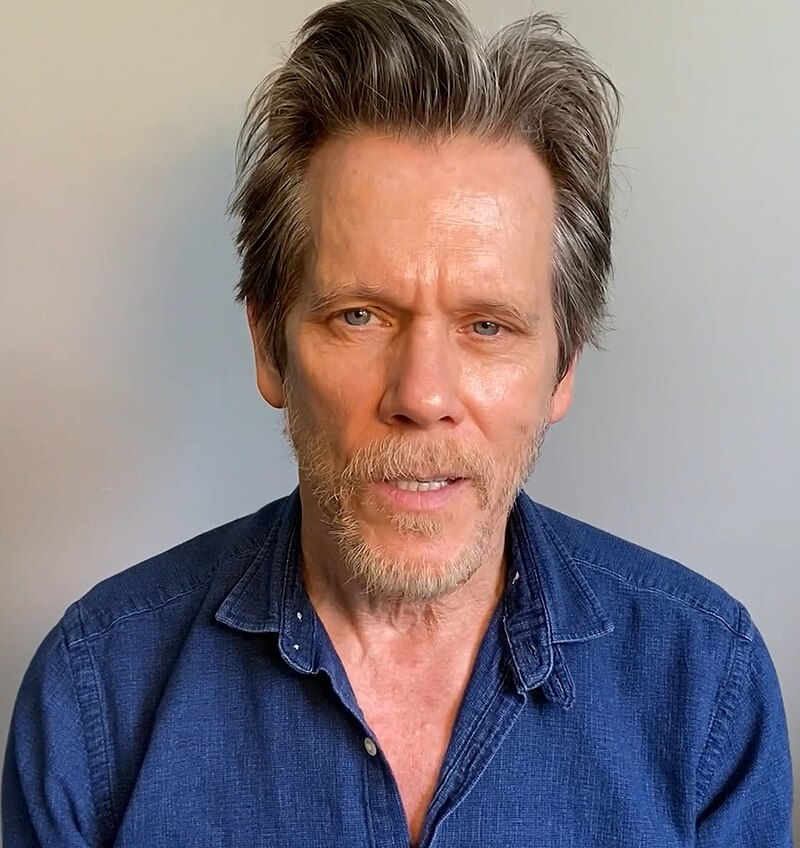

When Kaffee negotiates a plea bargain with the prosecutor, US Marine Judge Advocate Captain Jack Ross (Kevin Bacon), Dawson and Downey refuse, insisting that Kendrick gave them the “code red” order, that they never intended to kill Santiago, and that it would be dishonorable to pursue a plea bargain.

Above: American actor Kevin Bacon

Kaffee intends to get removed as counsel, but at the arraignment, he unexpectedly enters a plea of not guilty for the defendants.

He realized that he was chosen to handle the case because he was expected to accept a plea, so the matter would then be kept quiet.

Markinson meets Kaffee in secret and says that Jessep never ordered a transfer for Santiago.

The defense establishes that Dawson had been denied promotion for smuggling food to a Marine who had been sentenced to be deprived of food.

Dawson is portrayed in a good light, and the defense, through Downey, proves that “code reds” had been ordered before.

However, under cross-examination, Downey admits he was not present when Dawson received the supposed “code red” order.

Markinson, ashamed that he failed to protect a Marine under his command and unwilling to testify against Jessep, his longtime friend, commits suicide before he can testify.

Without Markinson’s testimony, Kaffee believes the case lost.

He returns home in a drunken stupor, lamenting that he fought the case instead of taking a deal.

Galloway encourages Kaffee to call Jessep as a witness, despite the risk of being court-martialed for challenging a high-ranking officer without evidence.

At the Washington Navy Yard court, Jessep spars with Kaffee’s questioning, but is unnerved when Kaffee points out a contradiction in his testimony.

Kaffee also calls into question Jessep’s claim that Santiago was to be put on the first flight home.

Upon further questioning, and disgusted by Kaffee’s attitude, Jessep extols the military’s, and his own, importance to national security.

Kaffee asks if Jessep ordered the “code red“, to which he bellows “You’re goddamn right I did!“.

Jessep tries to leave the courtroom but is arrested.

Above: Jack Nicholson and Tom Cruise, A Few Good Men

Dawson and Downey are cleared of the murder and conspiracy charges but found guilty of “conduct unbecoming” and will be dishonorably discharged.

Downey does not understand what they did wrong.

Dawson says that they failed to defend those too weak to fight for themselves.

Kaffee tells Dawson that it is not necessary to wear a patch on one’s arm to have honor.

Dawson acknowledges Kaffee as an officer by rendering a salute.

Kaffee and Ross exchange pleasantries before Ross departs to arrest Kendrick.

What grabs my attention is the final exchange between Kaffee and Jessup:

Kaffee: Now I’m asking you! Colonel Jessup, did you order the Code Red?!

Judge Randolph: You don’t have to answer that question!

Jessup: I’ll answer the question. You want answers?

Kaffee: I think I’m entitled to it!

Jessup: You want answers?!

Kaffee: I WANT THE TRUTH!!

Jessup:

You can’t handle the truth!

Son, we live in a world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns.

Who’s gonna do it?

You?

You, Lieutenant Weinberg?

I have a greater responsibility than you can possibly fathom.

You weep for Santiago and you curse the Marines.

You have that luxury.

You have the luxury of not knowing what I know:

That Santiago’s death, while tragic, probably saved lives.

And my existence, while grotesque and incomprehensible to you, saves lives!

You don’t want the truth, because deep down in places you don’t talk about at parties, you want me on that wall.

You need me on that wall.

We use words like “honor“, “code“, “loyalty“.

We use these words as the backbone of a life spent defending something.

You use them as a punchline!

I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very freedom that I provide, and then QUESTIONS the manner in which I provide it!

I would rather you just said “Thank you” and went on your way.

Otherwise, I suggest you pick up a weapon, and stand a post.

Either way, I don’t give a DAMN what you think you are entitled to!

Kaffee: Did you order the Code Red?

Jessup: I did the job that—

Kaffee: DID YOU ORDER THE CODE RED?!

Jessup: YOU’RE GODDAMN RIGHT I DID!!!

You can’t handle the truth!

Colonel Jessup’s words reverberate like a cannon blast in the courtroom.

The truth, raw and unvarnished, is too much to bear.

It shatters illusions, it exposes the darkness in good men’s hearts, and it demands accountability.

And so, the truth is hidden, softened, reshaped — because the world finds comfort in half-truths.

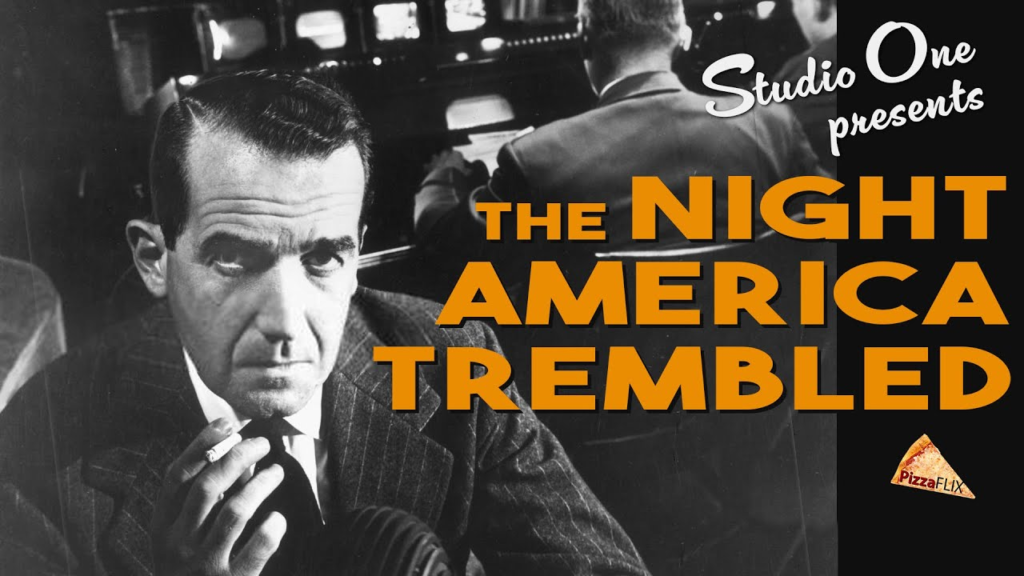

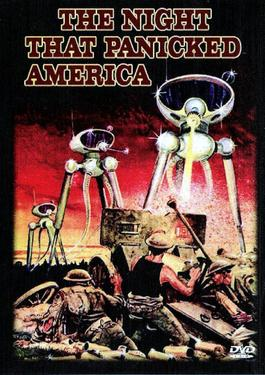

Twelve Angry Men is a play by Reginald Rose adapted from his 1954 teleplay of the same title for the CBS Studio One anthology television series.

The 1957 feature film adaptation is the version most of us think of when we hear the title Twelve Angry Men mentioned.

A critique of the American jury system during the McCarthy Era, the film tells the story of a jury of twelve men as they deliberate the conviction or acquittal of a teenager charged with murder on the basis of reasonable doubt.

Disagreement and conflict among the jurors forces them to question their morals and values.

On a hot summer day in the New York County Courthouse, the trial phase has just concluded for an impoverished 18-year-old boy accused of killing his abusive father.

The judge (Rudy Bond) instructs the jury.

Judge:

If there’s a reasonable doubt in your minds as to the guilt of the accused, a reasonable doubt, then you must bring me a verdict of not guilty.

If however, there is no reasonable doubt, then you must in good conscience find the accused guilty.

However you decide, your verdict must be unanimous.

In the event that you find the accused guilty, the bench will not entertain a recommendation for mercy.

The death sentence is mandatory in this case.

You are faced with a grave responsibility.

Thank you, gentlemen.

Above: American actor Rudy Bond (1912 – 1982)

At first, the case seems clear.

A neighbor testified to witnessing the defendant stab his father, from her window, through the windows of a passing elevated train.

Another neighbor testified that he heard the defendant threaten to kill his father, and the father’s body hitting the floor.

Then, as he ran to his door, he saw the defendant running down the stairs.

The boy had recently purchased a switchblade of the same type that was found, wiped of fingerprints, at the murder scene, but claimed he lost it.

In a preliminary vote, all jurors vote “guilty” except Juror 8 (Henry Fonda), who believes there should be some discussion before the verdict.

He says he cannot vote “guilty” because reasonable doubt exists.

Above: American actor Henry Fonda (1905 – 1982)

#8:

This kid has been kicked around all of his life.

You know, born in a slum.

Mother dead since he was nine.

He lived for a year and a half in an orphanage when his father was serving a jail term for forgery.

That is not a very happy beginning.

He is a wild, angry kid, and that’s all he has ever been.

And you know why because he has been hit on the head by somebody once a day, every day.

He has had a pretty miserable 18 years.

I just think we owe him a few words, that’s all.

#10:

I don’t mind telling you this, mister.

We don’t owe him a thing.

He got a fair trial, didn’t he?

What do you think that trial cost?

He’s lucky he got it.

You know what I mean?

Now look, we’re all grown-ups in here.

We heard the facts, didn’t we?

You’re not gonna tell me that we’re supposed to believe this kid, knowing what he is.

Listen, I’ve lived among them all my life.

You can’t believe a word they say.

You know that.

I mean, they’re born liars.

#9:

Only an ignorant man can believe that…

Do you think you were born with a monopoly on the truth?

When his first few arguments (including producing a recently purchased knife nearly identical to the murder weapon that was thought to be unique) seemingly fail to convince any of the other jurors, Juror 8 suggests a secret ballot, from which he will abstain.

If all the other jurors still vote guilty, he will acquiesce.

The ballot reveals one “not guilty” vote.

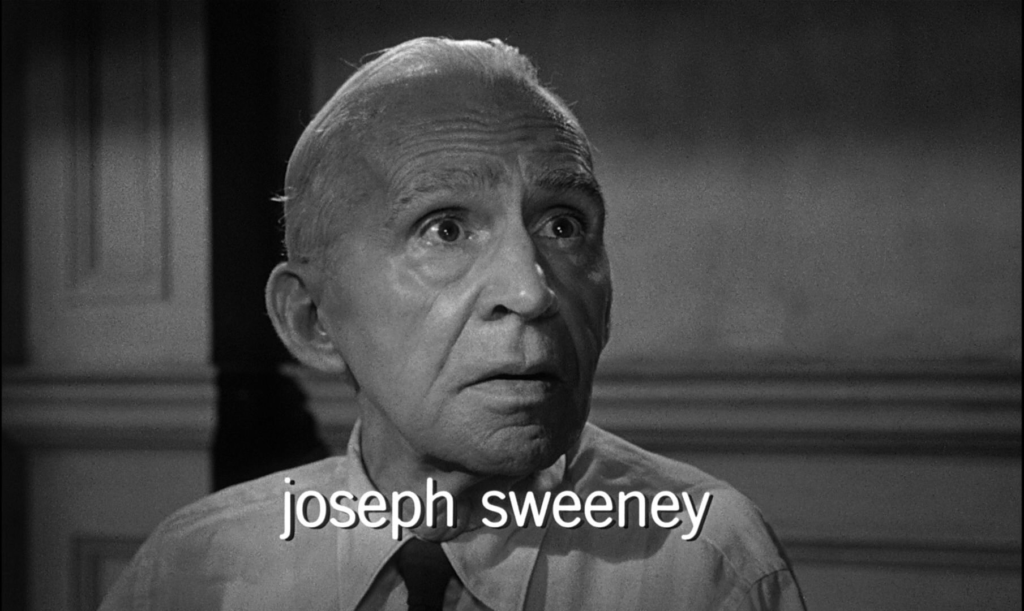

Juror 9 (Joseph Sweeney) reveals that he changed his vote.

He respects Juror 8’s motives, and agrees there should be more discussion.

Above: American actor Joseph Sweeney (1884 – 1963)

Juror 8 argues that the train noise would have obscured everything the second witness claimed to have overheard.

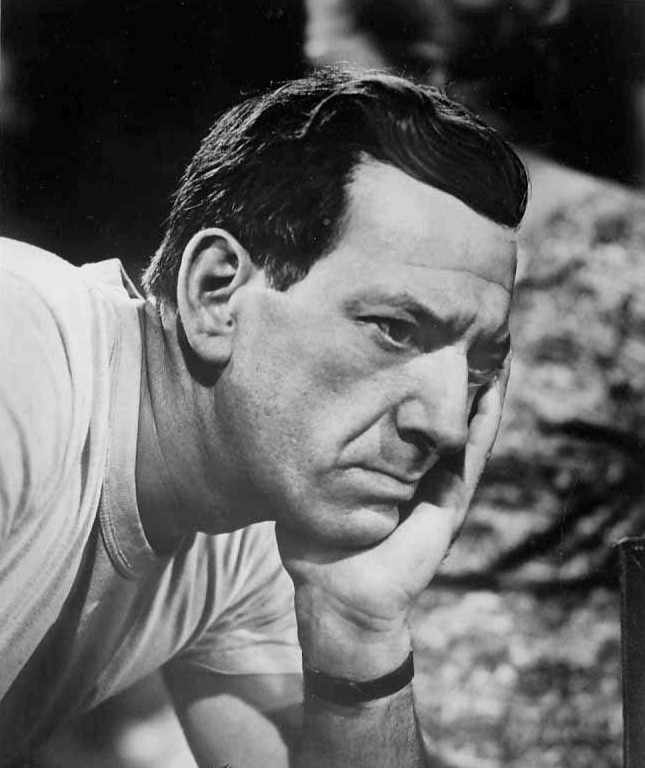

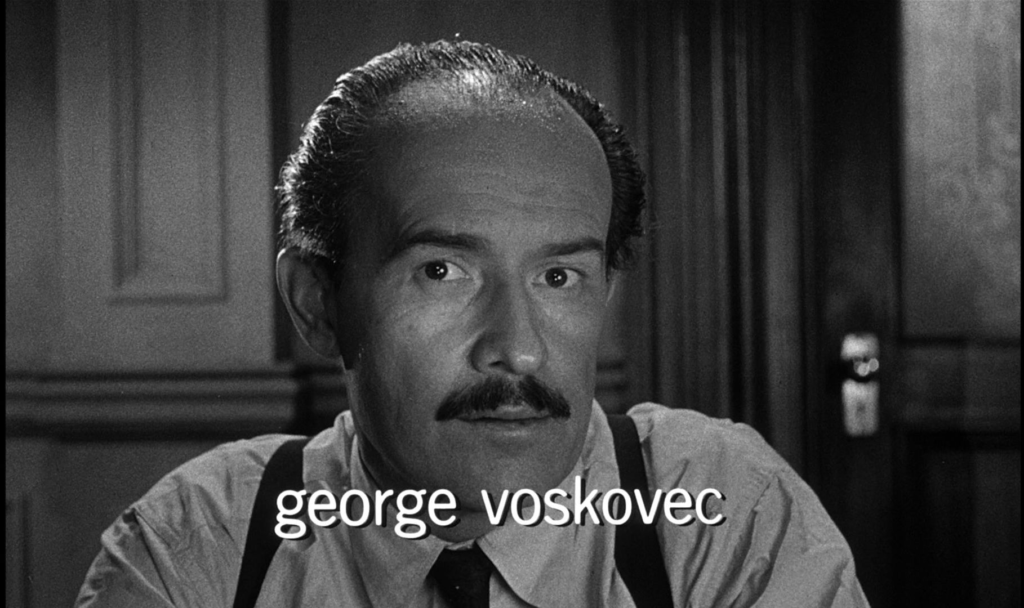

Jurors 5 (Jack Klugman) and 11 (George Voskovec) change their votes.

Above: American actor Jack Klugman (1922 – 2012)

Above: Czech actor George Voskovec (né Jiří Wachsmann)(1905 – 1981)

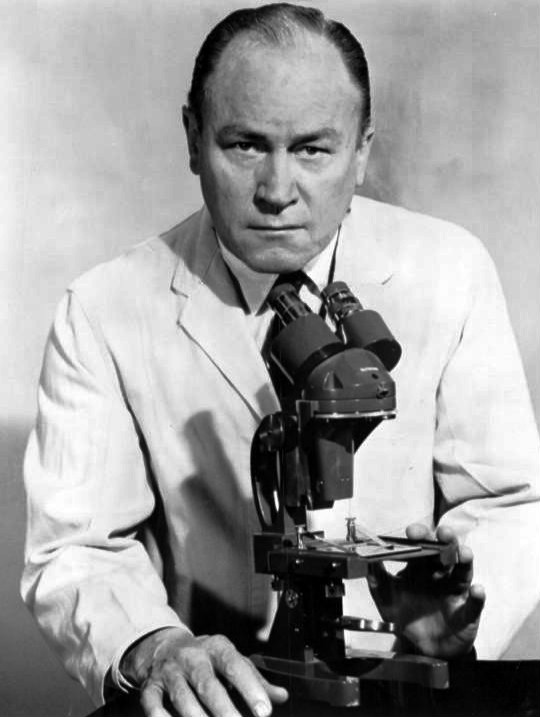

Jurors 5, 6 (Edward Binns) and 8 further question the second witness’s story, and question whether the death threat was figurative speech.

Above: American actor Edward Binns (1916 – 1990)

After looking at a diagram of the witness’s apartment and conducting an experiment, the jurors determine that it is impossible for the disabled witness to have made it to the door in time.

Juror 3 (Lee J. Cobb), infuriated, argues with and tries to attack Juror 8, yelling a death threat.

Above: American actor Lee J. Cobb (né Leo Jacoby) (1911 – 1976)

Jurors 5, 6 and 7 (Jack Warden) physically restrain Juror 3.

Above: American actor Jack Warden (né John Warden Lebzelter Jr.) (1920 – 2006)

Jurors 2 (John Fiedler) and 6 change their votes.

Above: American actor John Fiedler (1925 – 2005)

The jury is now evenly split.

Juror 4 (E. G. Marshall) doubts the defendant’s alibi, as the boy did not recall specific details.

Above: American actor E. G. Marshall (né Everett Eugene Grunz) (1914 – 1998)

Juror 8 tests Juror 4’s own memory to make a point.

Jurors 2 and 5 point out the father’s stab wound was angled downwards, although the boy was shorter than his father.

Juror 7 changes his vote out of impatience rather than conviction, angering Juror 11.

After another vote, jurors 1 (Martin Balsam) and 12 (Robert Webber) also change sides, leaving only three “guilty” votes.

Above: American actor Martin Balsam (1919 – 1996)

Above: American actor Robert Webber (1924 – 1989)

Juror 10 (Ed Begley) goes on a bigoted rant, causing Juror 4 to forbid him to speak for the remainder of the deliberation.

Above: American actor Ed Begley (1901 – 1970)

When Juror 4 is pressed as to why he still maintains a guilty vote, he declares that the woman who saw the killing from across the street stands as solid evidence.

Juror 12 reverts to a guilty vote.

After watching Juror 4 remove his spectacles and rub the impressions they made on his nose, Juror 9 realizes that the first witness was constantly rubbing similar impressions on her own nose, indicating that she also was a habitual glasses wearer, even though she chose not to wear her glasses in court.

Juror 8 remarks that the witness, who was trying to sleep when she saw the killing, would not have had glasses on or the time to put them on, making her story questionable.

Jurors 4, 10 and 12 all change their votes, leaving Juror 3 as the sole dissenter.

Juror 3 vehemently and desperately tries to convince the others of his argument, but realizes that his strained relationship with his own son makes him wish the defendant guilty.

He breaks down in tears and changes his vote to “not guilty“.

As the others leave, Juror 8 graciously helps Juror 3 put on his coat.

The defendant is acquitted off-screen.

As the jurors leave the courthouse, Jurors 8 (Davis) and 9 (McCardle) reveal their surnames to each other before parting ways.

A room filled with sweat and tension.

A single dissenting voice forces twelve men to examine their prejudices.

One by one, they unravel their own biases, confronted with the unsettling realization that truth is not always what it appears to be at first glance.

They resist.

They fight.

But truth, persistent and unrelenting, refuses to remain buried.

Above: Scene from Twelve Angry Men

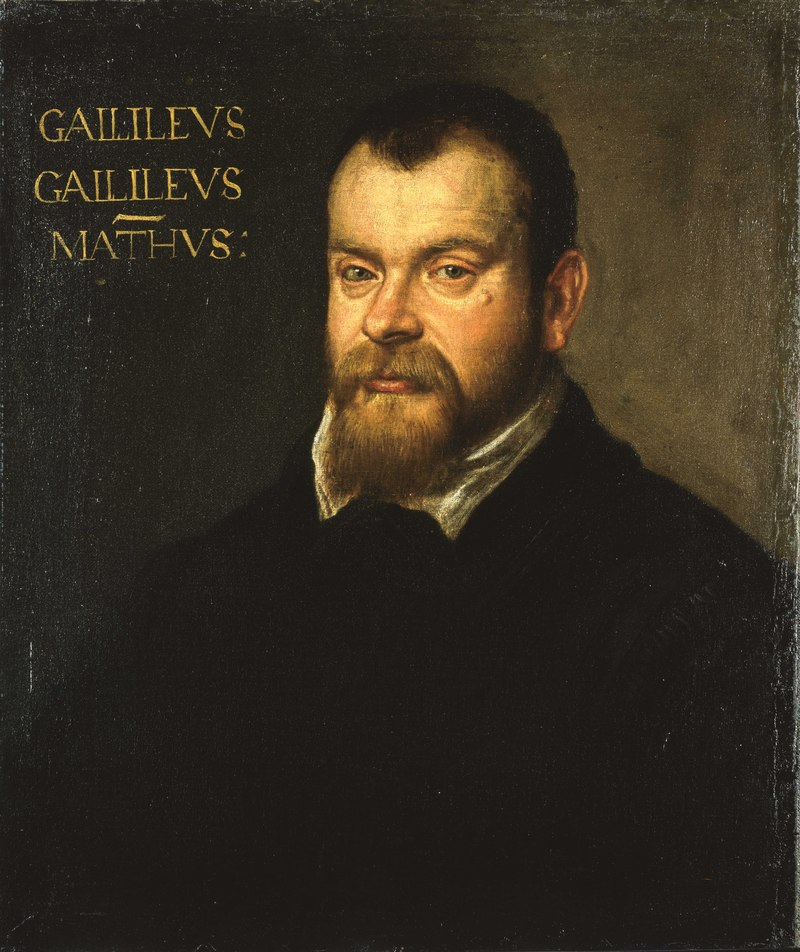

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de’ Galilei (1564 – 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath.

He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence.

Above: Pisa, Italy

Galileo has been called the father of observational astronomy, modern-era classical physics, the scientific method, and modern science.

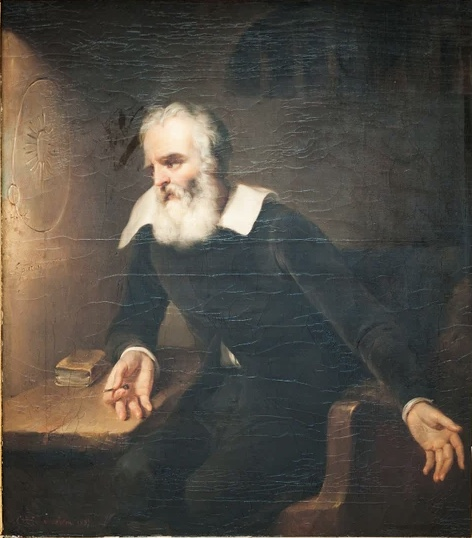

Above: Italian scientist Galileo Galilei

Galileo studied speed and velocity, gravity and free fall, the principle of relativity, inertia, projectile motion and also worked in applied science and technology, describing the properties of the pendulum and “hydrostatic balances“.

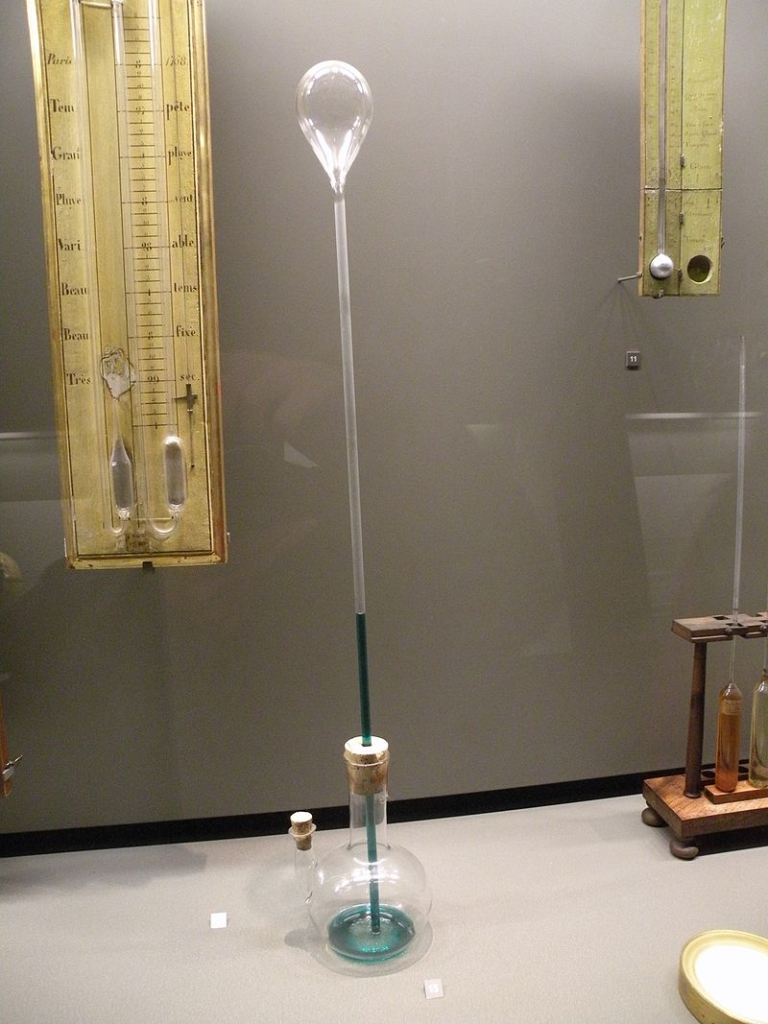

He was one of the earliest Renaissance developers of the thermoscope and the inventor of various military compasses.

Above: Galileo thermoscope, Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris, France

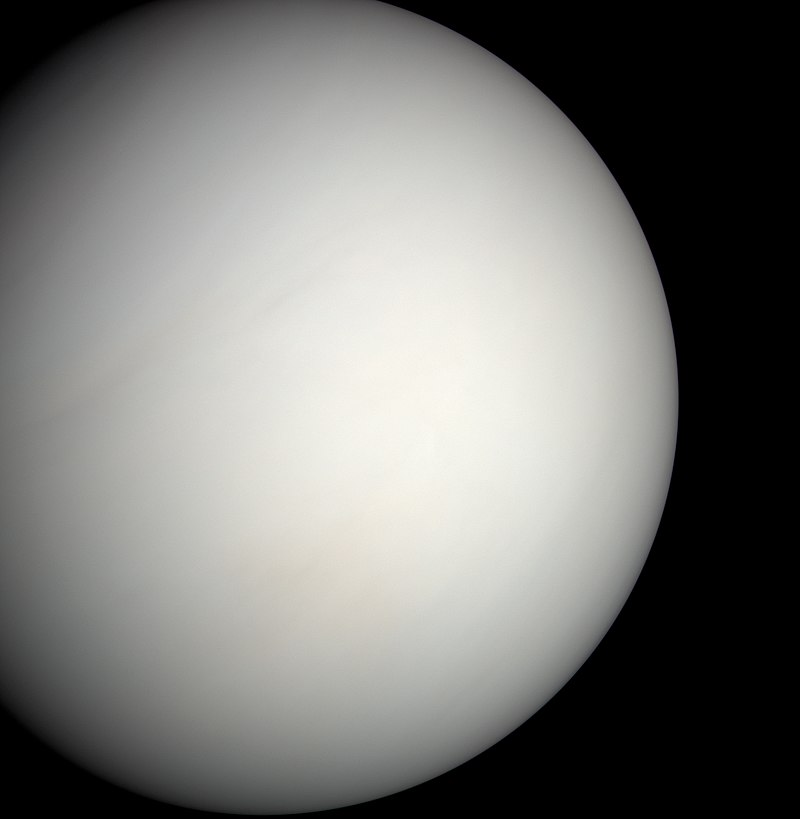

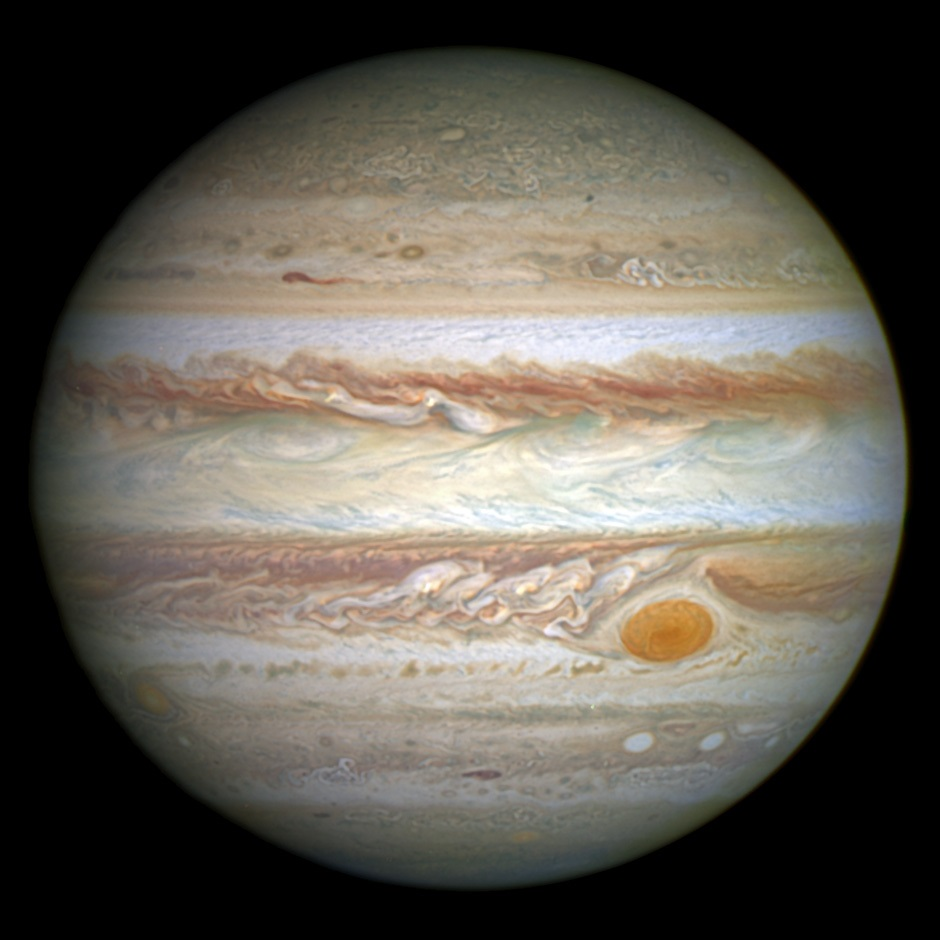

With an improved telescope he built, he observed the stars of the Milky Way, the phases of Venus, the four largest satellites of Jupiter, Saturn’s rings, lunar craters and sunspots.

Above: The Milky Way

Above: The planet Venus

Above: The planet Jupiter

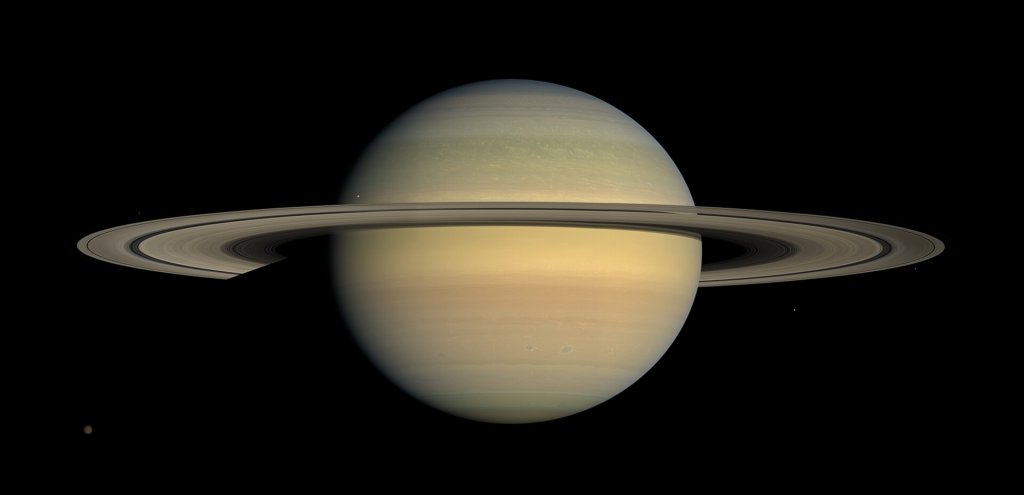

Above: The planet Saturn

Above: Lunar craters

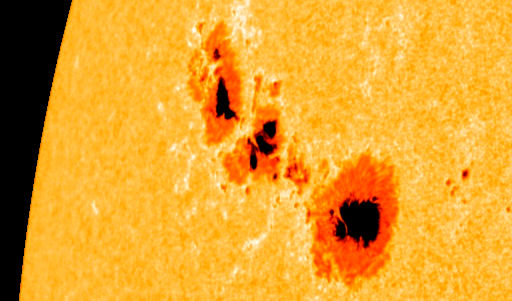

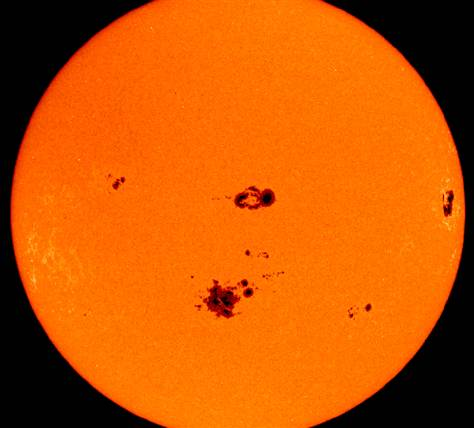

Above: Sunspots

He also built an early microscope.

Above: Microscope

Galileo’s championing of Copernican heliocentrism was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers.

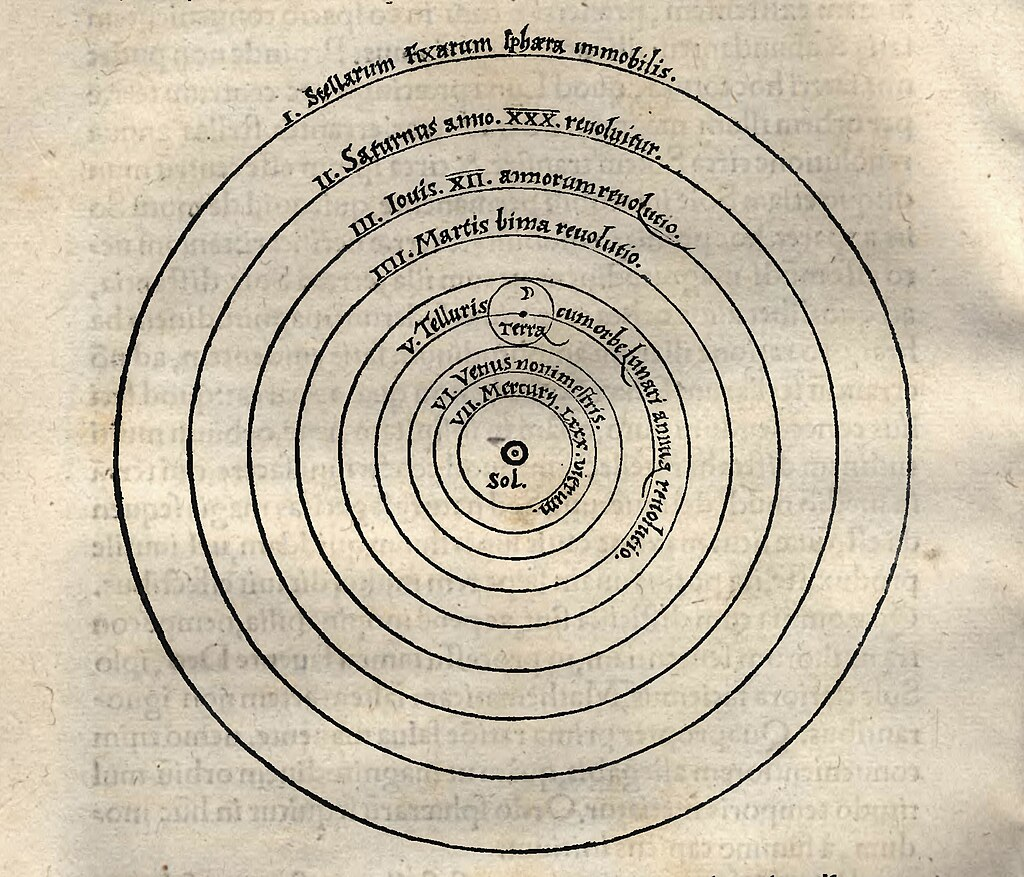

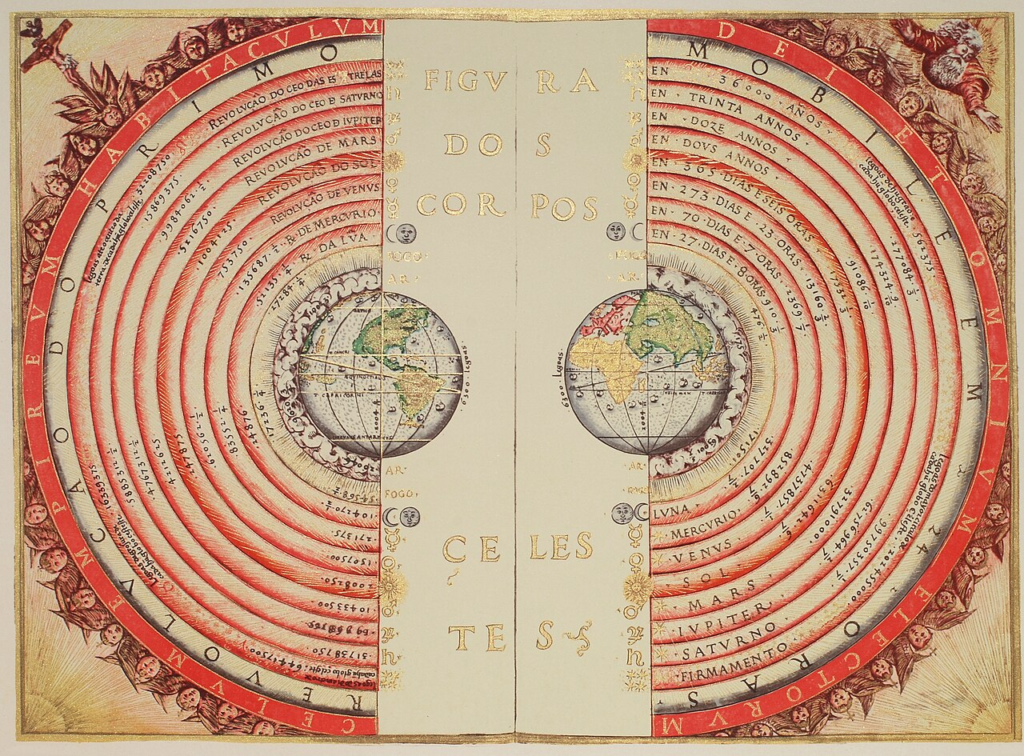

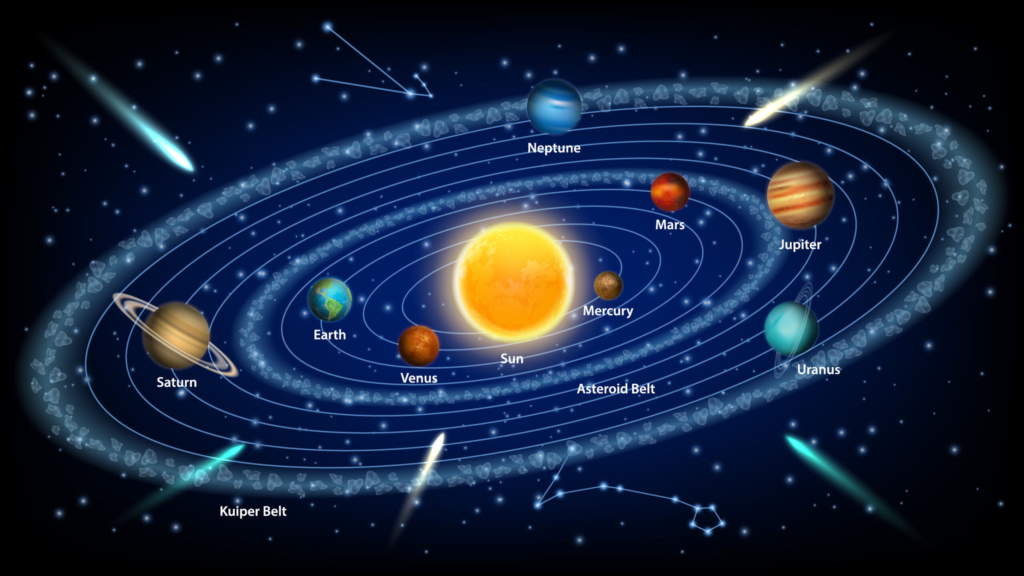

Above: Image of heliocentric model from Nicolaus Copernicus’ “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres)

The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that his opinions contradicted accepted Biblical interpretations.

Above: Emblem of the Holy See and the Papacy of the Catholic Church

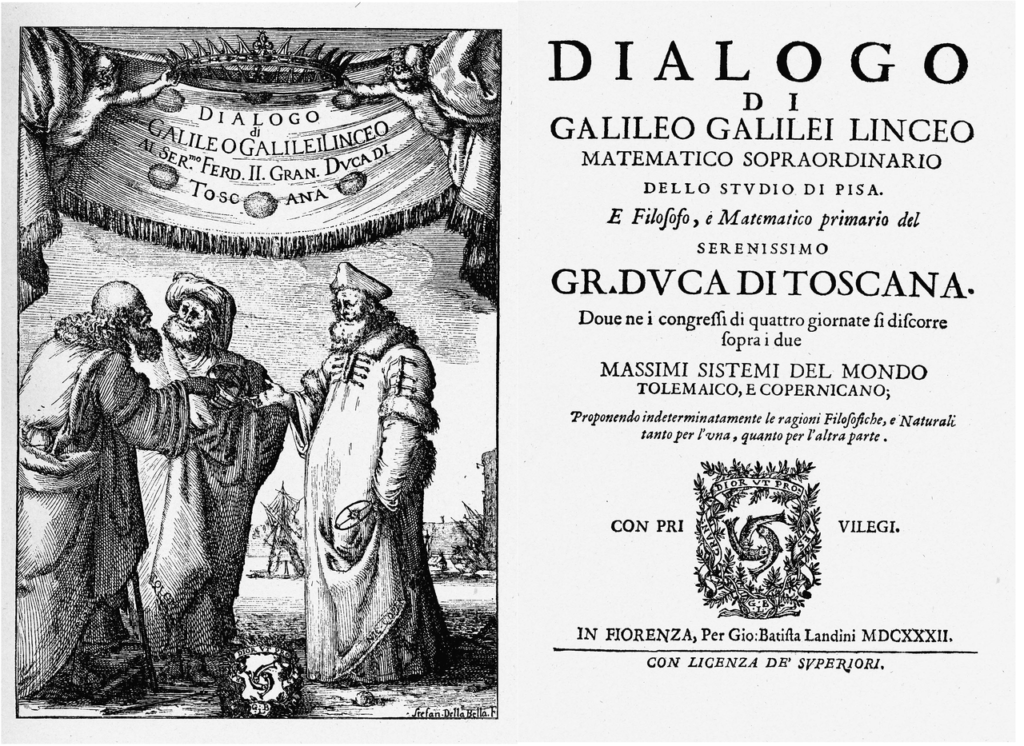

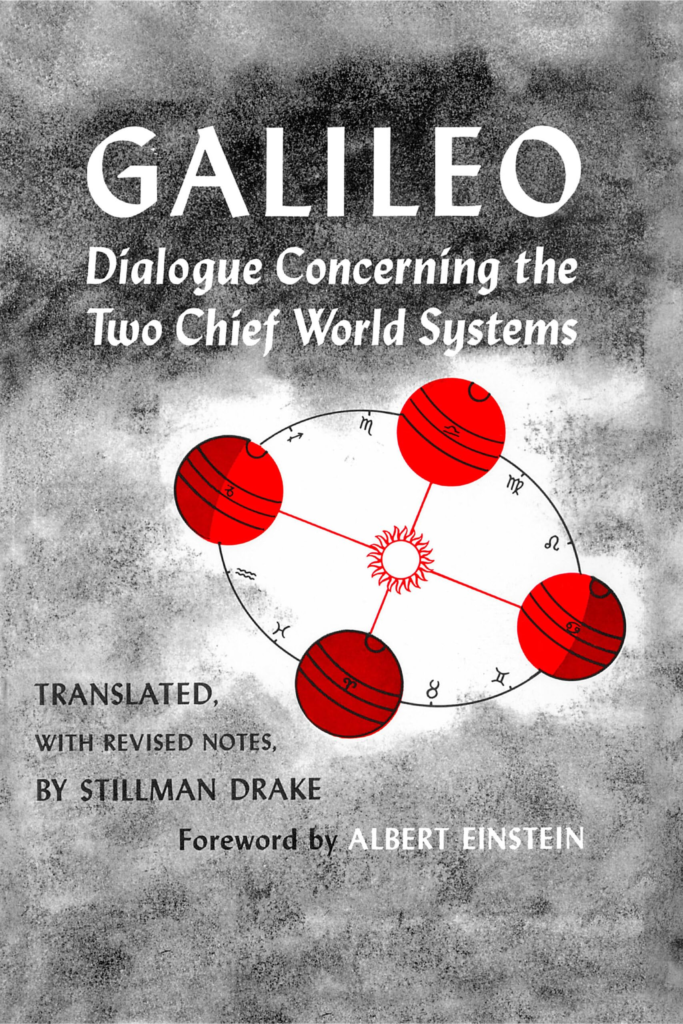

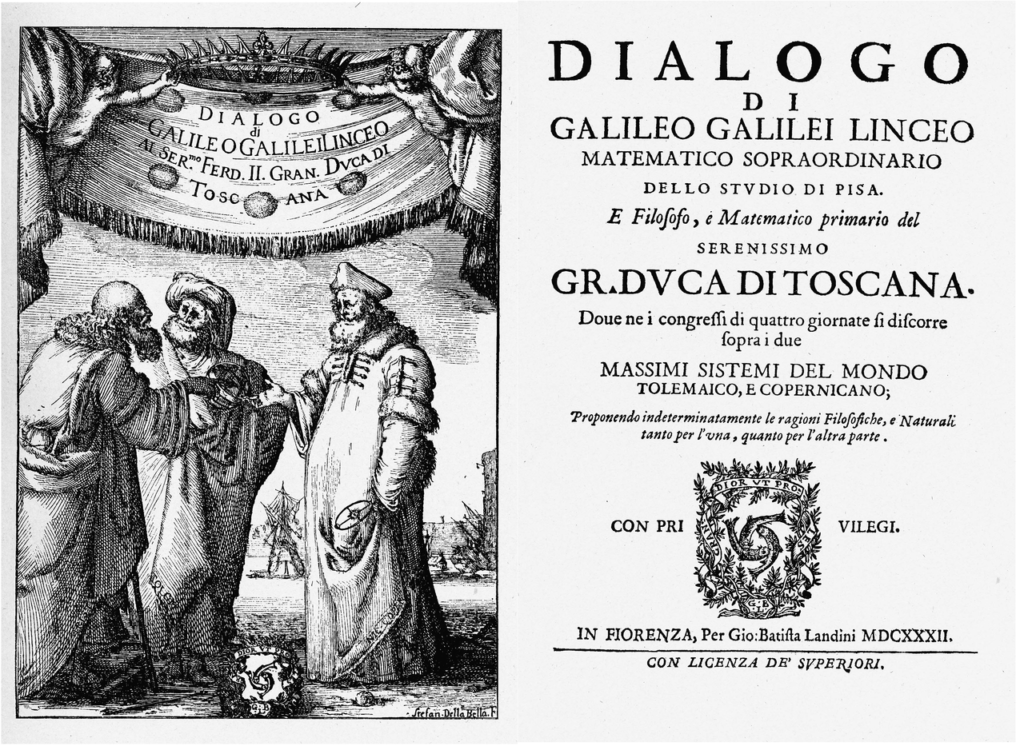

Galileo later defended his views in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which appeared to attack and ridicule Pope Urban VIII, thus alienating both the Pope and the Jesuits, who had both strongly supported Galileo up until this point.

Above: Italian Pope Urban VIII (né Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini)(1568 – 1644)

Above: Logo of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits)

He was tried by the Inquisition, found “vehemently suspect of heresy“, and forced to recant.

He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

During this time, he wrote Two New Sciences (1638), primarily concerning kinematics and the strength of materials.

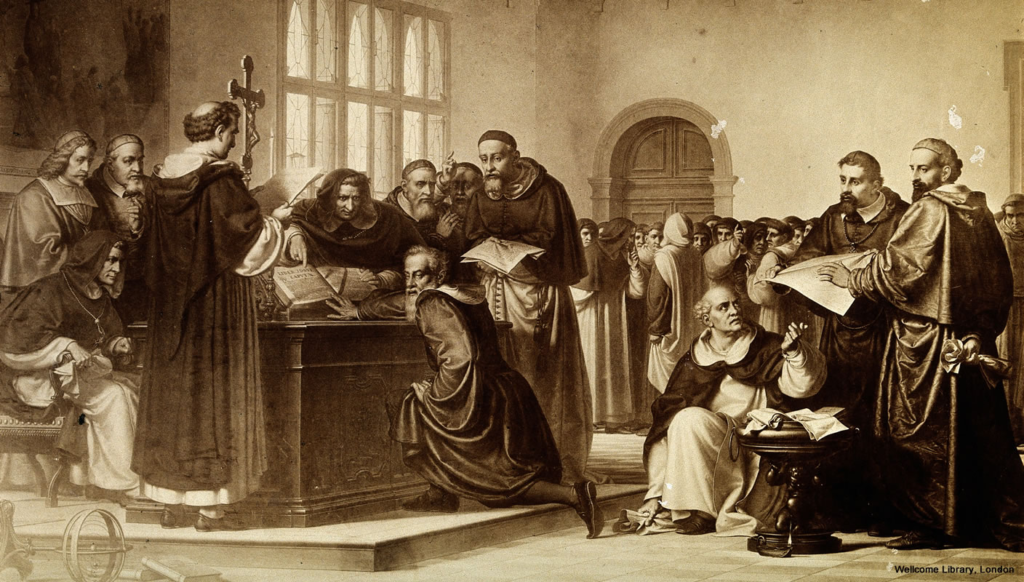

The Galileo affair (Italian: il processo a Galileo Galilei) began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633.

Galileo was prosecuted for holding as true the doctrine of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe.

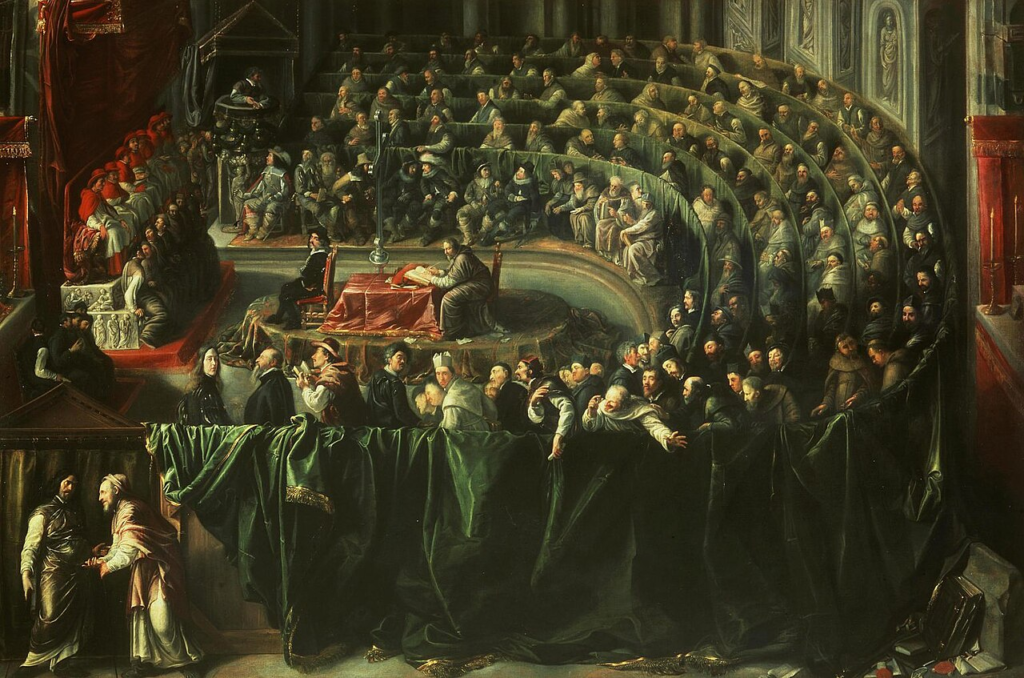

Above: Galileo facing the Roman Inquisition, Christiano Banti (1857)

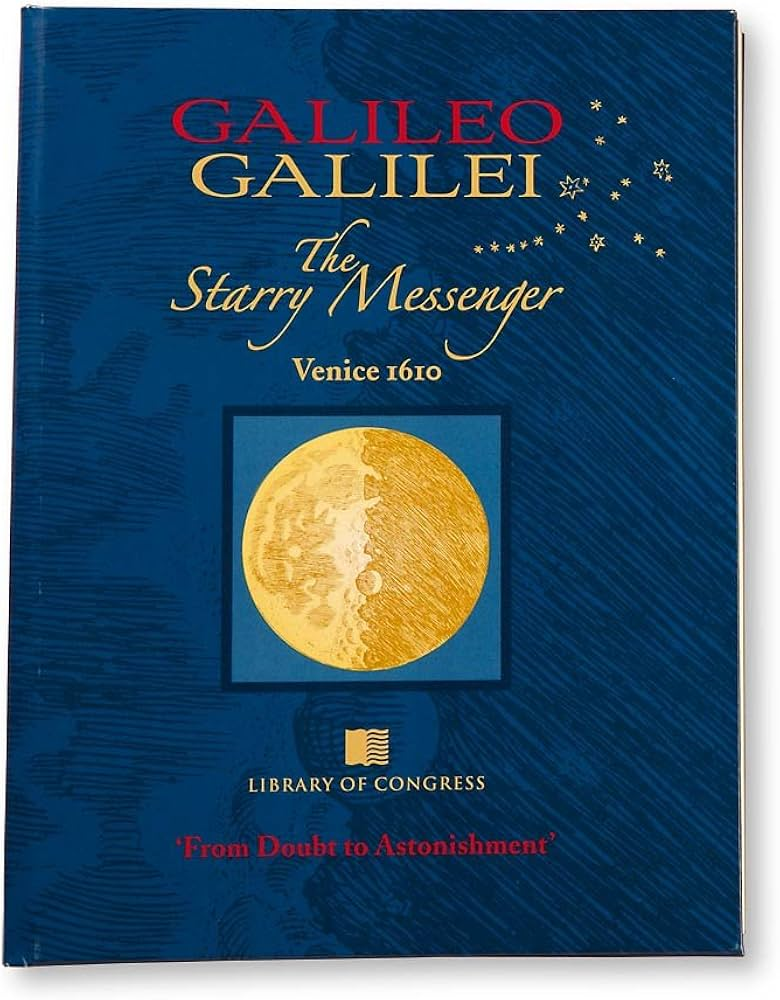

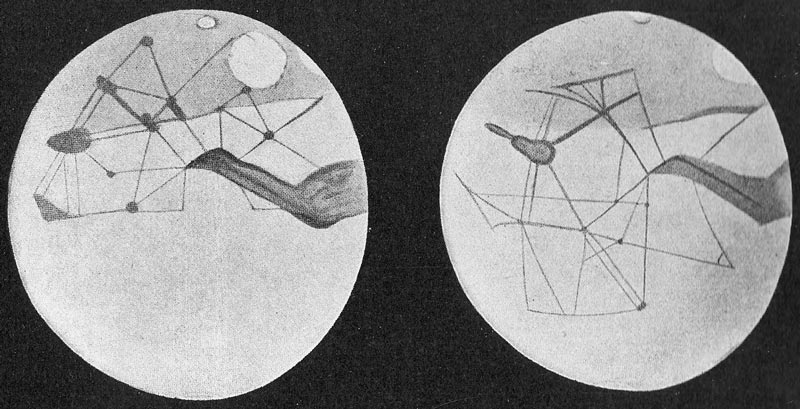

In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), describing the observations that he had made with his new, much stronger telescope, amongst them, the Galilean moons of Jupiter.

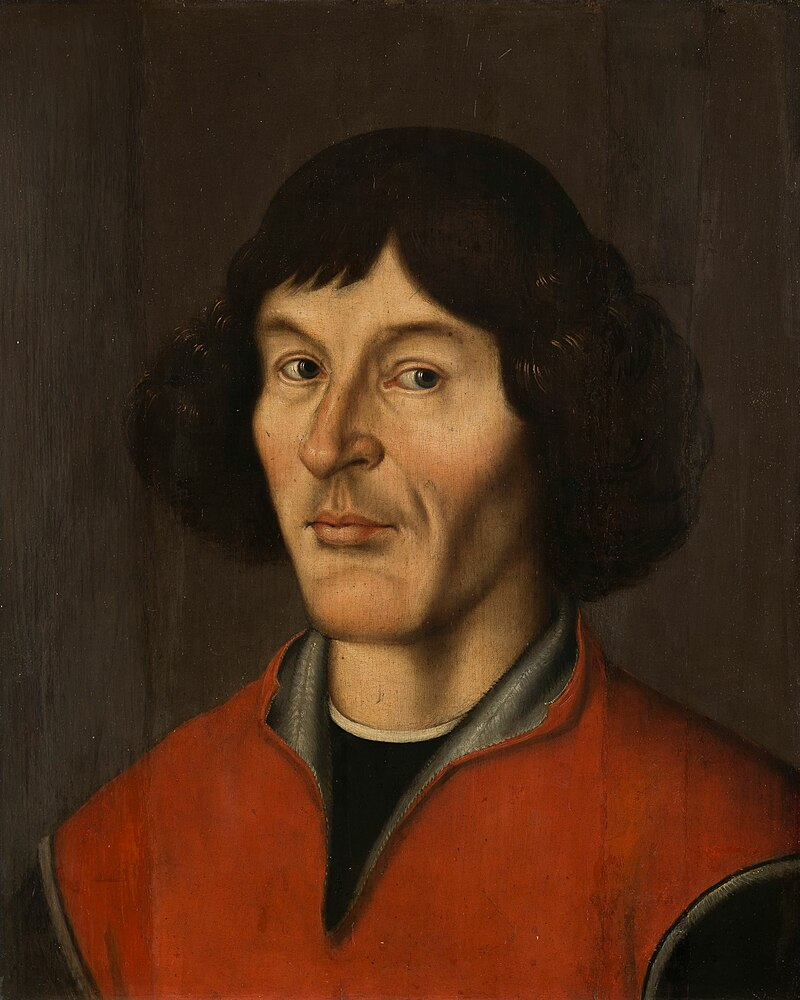

With these observations and additional observations that followed, such as the phases of Venus, he promoted the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus published in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543.

Above: Polish polymath Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543)

Galileo’s opinions were met with opposition within the Catholic Church.

Above: St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

In 1616 the Inquisition declared heliocentrism to be “formally heretical“.

Above: Galileo Galilei before the Holy Office, Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury (1847)

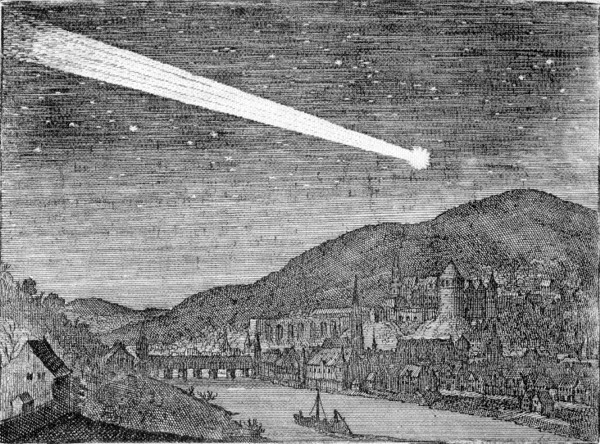

Galileo went on to propose a theory of tides in 1616 and of comets in 1619.

He argued that the tides were evidence for the motion of the Earth.

Above: Simplified schematic of only the lunar portion of Earth’s tides, showing (exaggerated) high tides at the sublunar point and its antipode for the hypothetical case of an ocean of constant depth without land, and on the assumption that Earth is not rotating – otherwise there is a lag angle.

Above: Heidelberg Comet (1618)

In 1632, Galileo published his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, which defended heliocentrism.

It was immensely popular.

Responding to mounting controversy over theology, astronomy and philosophy, the Roman Inquisition tried Galileo in 1633, found him “vehemently suspect of heresy” and sentenced him to house arrest where he remained until his death in 1642.

Above: Villa Il Gioiello (“the jewel“), Galileo home (1631 – 1642), Arcentri, Italy

At that point, heliocentric books were banned.

Galileo was ordered to abstain from holding, teaching or defending heliocentric ideas after the trial.

The affair was complex since very early on Pope Urban VIII had been a patron to Galileo and had given him permission to publish on the Copernican theory as long as he treated it as a hypothesis, but after the publication in 1632, the patronage was broken off due to numerous reasons.

Historians of science have corrected numerous false interpretations of the affair.

Above: Galileo Galilei

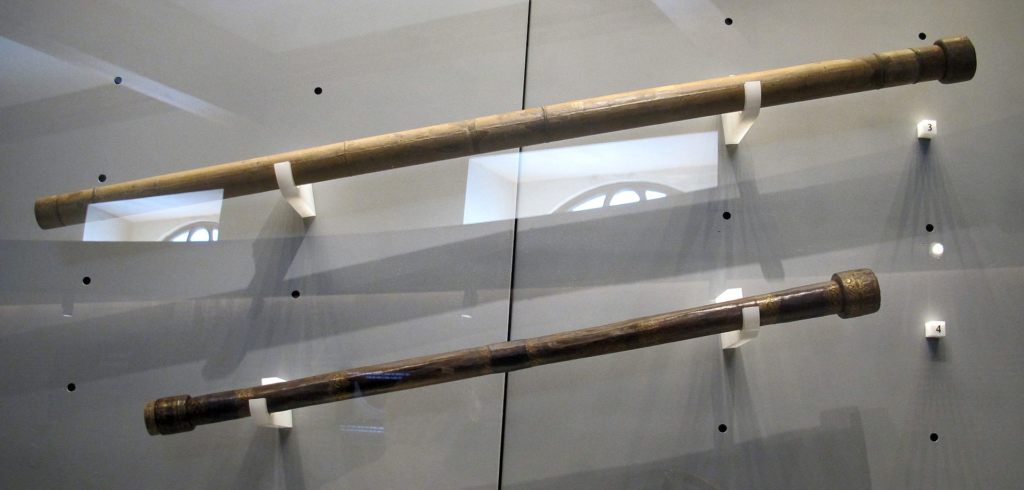

Galileo began his telescopic observations in the later part of 1609, and by March 1610 was able to publish a small book, The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius), describing some of his discoveries:

- mountains on the Moon

- lesser moons in orbit around Jupiter

- the resolution of what had been thought to be very cloudy masses in the sky (nebulae) into collections of stars too faint to see individually without a telescope.

Other observations followed, including the phases of Venus and the existence of sunspots.

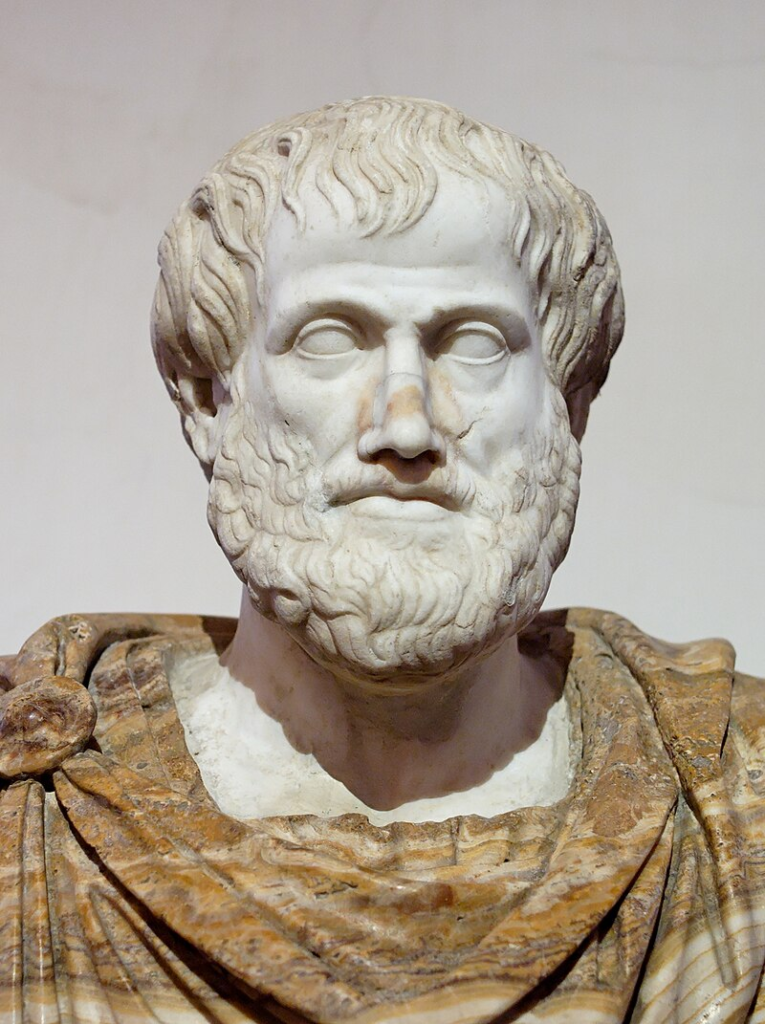

Galileo’s contributions caused difficulties for theologians and natural philosophers of the time, as they contradicted scientific and philosophical ideas based on those of Aristotle and Ptolemy and closely associated with the Catholic Church.

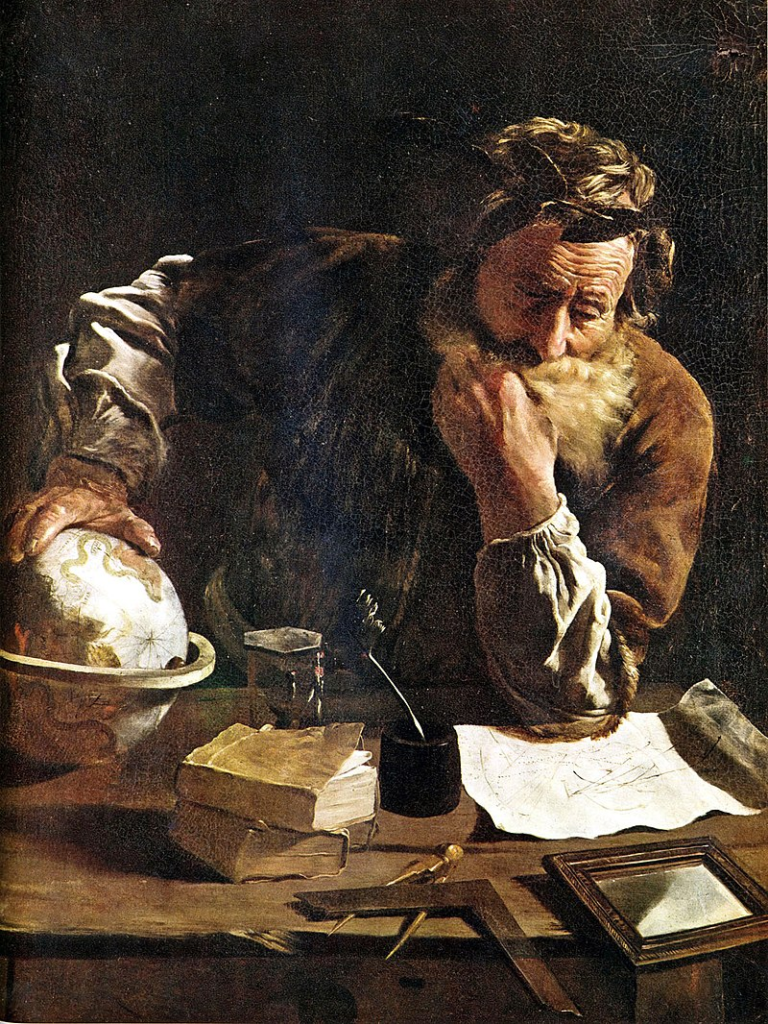

Above: Greek polymath Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

Above: Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy (100 – 170)

In particular, Galileo’s observations of the phases of Venus, which showed it to circle the Sun, and the observation of moons orbiting Jupiter, contradicted the geocentric model of Ptolemy, which was backed and accepted by the Roman Catholic Church, and supported the Copernican model advanced by Galileo.

Above: Phases of Venus

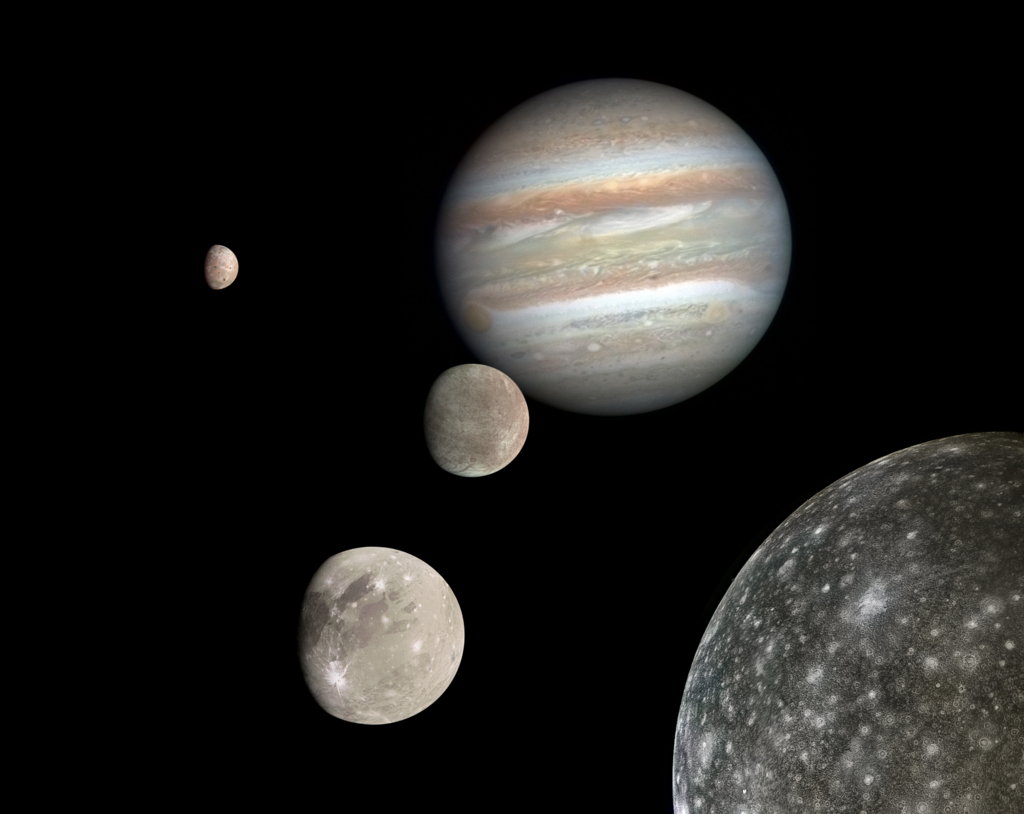

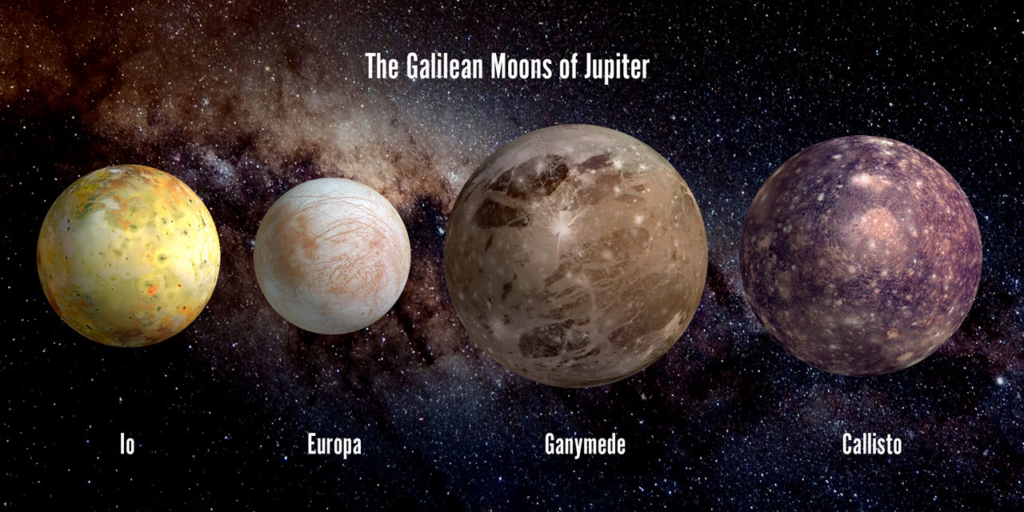

Above: The moons of Jupiter

There are 95 moons of Jupiter with confirmed orbits as of 5 February 2024.

This number does not include a number of meter-sized moonlets thought to be shed from the inner moons, nor hundreds of possible kilometer-sized outer irregular moons that were only briefly captured by telescopes.

All together, Jupiter’s moons form a satellite system called the Jovian system.

The most massive of the moons are the four Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, which were independently discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei and Simon Marius and were the first objects found to orbit a body that was neither Earth nor the Sun.

Much more recently, beginning in 1892, dozens of far smaller Jovian moons have been detected and have received the names of lovers (or other sexual partners) or daughters of the Roman god Jupiter or his Greek equivalent Zeus.

The Galilean moons are by far the largest and most massive objects to orbit Jupiter, with the remaining 91 known moons and the rings together comprising just 0.003% of the total orbiting mass.

Above: Jupiter and the Galilean moons

(From top to bottom: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto)

Jesuit astronomers, experts both in Church teachings, science, and in natural philosophy, were at first skeptical and hostile to the new ideas; however, within a year or two the availability of good telescopes enabled them to repeat the observations.

In 1611, Galileo visited the Collegium Romanum in Rome, where the Jesuit astronomers by that time had repeated his observations.

Above: Seal of the Gregorian University, Rome, Italy

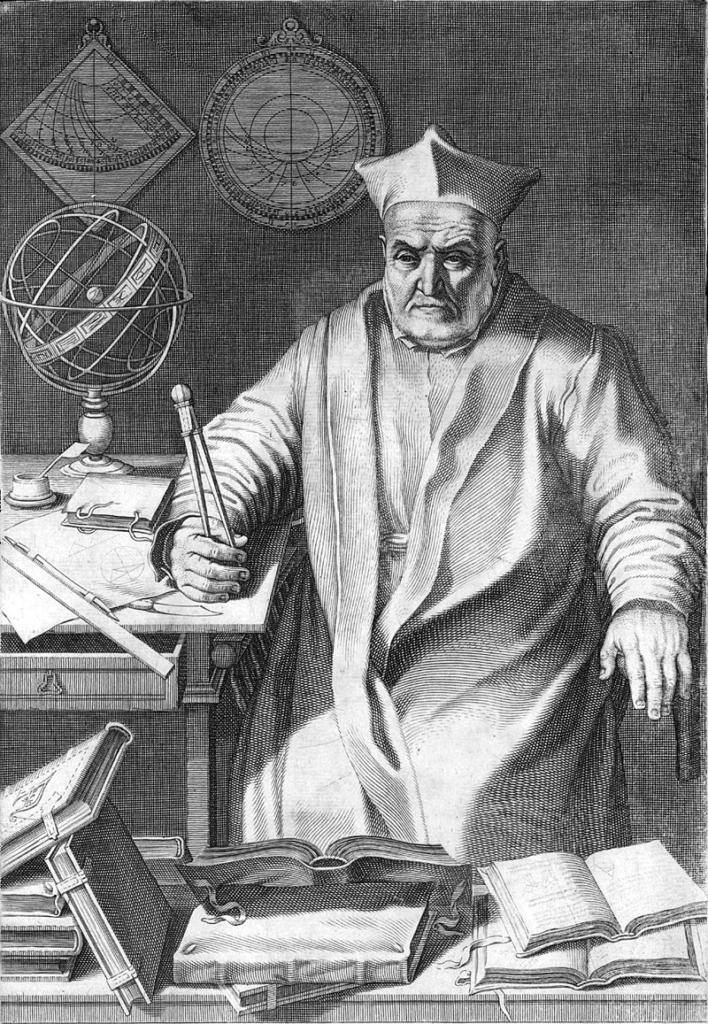

Christoph Grienberger, one of the Jesuit scholars on the faculty, sympathized with Galileo’s theories, but was asked to defend the Aristotelian viewpoint by Claudio Acquaviva, the Father General of the Jesuits.

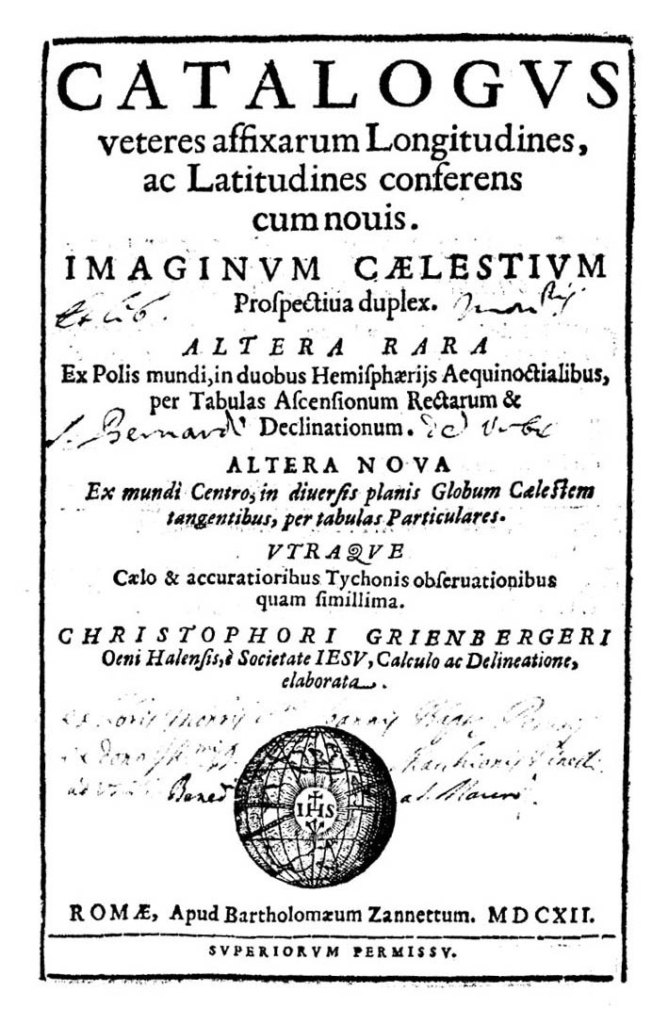

Above: Christoph Grienberger, Catalogus veteres affixarum longitudines, ac latitudines conferens cum novis, 1612

Above: Jesuit Superior General Claudio Acquaviva (1543 – 1615)

Not all of Galileo’s claims were completely accepted:

Christopher Clavius, the most distinguished astronomer of his age, never was reconciled to the idea of mountains on the Moon, and outside the Collegium many still disputed the reality of the observations.

Above: German astronomer Christopher Clavius (1538 – 1612)

In a letter to Kepler of August 1610, Galileo complained that some of the philosophers who opposed his discoveries had refused even to look through a telescope:

Above: Galileo’s “cannocchiali” telescopes at the Museo Galileo, Firenze (Florence), Italia (Italy)

My dear Kepler, I wish that we might laugh at the remarkable stupidity of the common herd.

What do you have to say about the principal philosophers of this academy who are filled with the stubbornness of an asp and do not want to look at either the planets, the moon or the telescope, even though I have freely and deliberately offered them the opportunity a thousand times?

Truly, just as the asp stops its ears, so do these philosophers shut their eyes to the light of truth.”

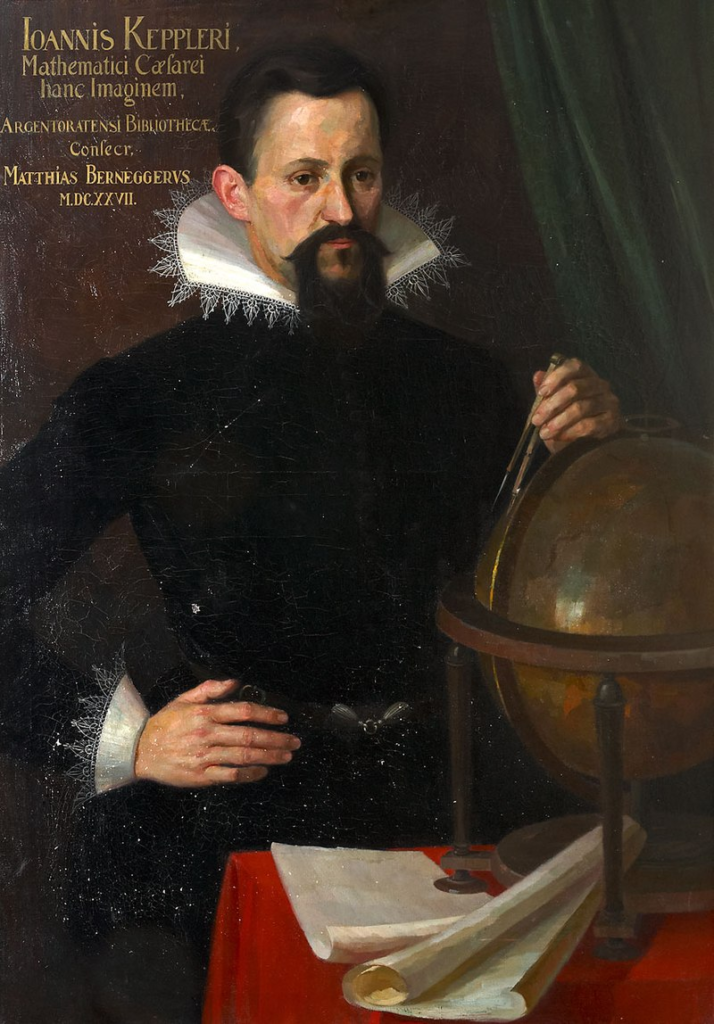

Above: German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630)

In 1611, the same year that Galileo visited the Collegium Romanum, his theories first came to the attention of the Roman Inquisition.

A commission of cardinals working with the Inquisition made inquiries into Galileo’s activites, and asked the city of Padua if he had any connections to Cesare Cremonini, a professor at the University of Padua who had been charged with heresy by the Inquisition.

Above: Padova (Padua), Italia (Italy)

These inquiries marked the first time Galileo’s name was brought before the Inquisition.

Above: Italian philosopher Cesare Cremonini (1550 – 1631)

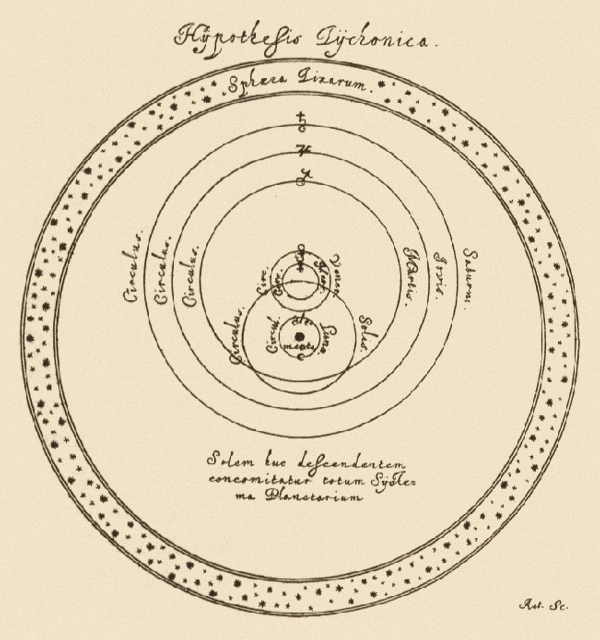

Geocentrists who did verify and accept Galileo’s findings had an alternative to Ptolemy’s model in an alternative geocentric (or “geo-heliocentric“) model proposed some decades earlier by Tycho Brahe – a model in which, for example, Venus circled the Sun.

Above: Tychonian system

Tycho argued that the distance to the stars in the Copernican system would have to be 700 times greater than the distance from the Sun to Saturn.

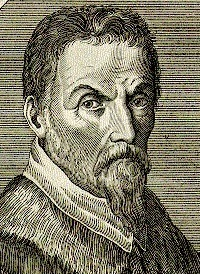

Above: Swedish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546 – 1601)

(The nearest star other than the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is in fact over 28,000 times the distance from the Sun to Saturn.)

Above: Proxima Centauri

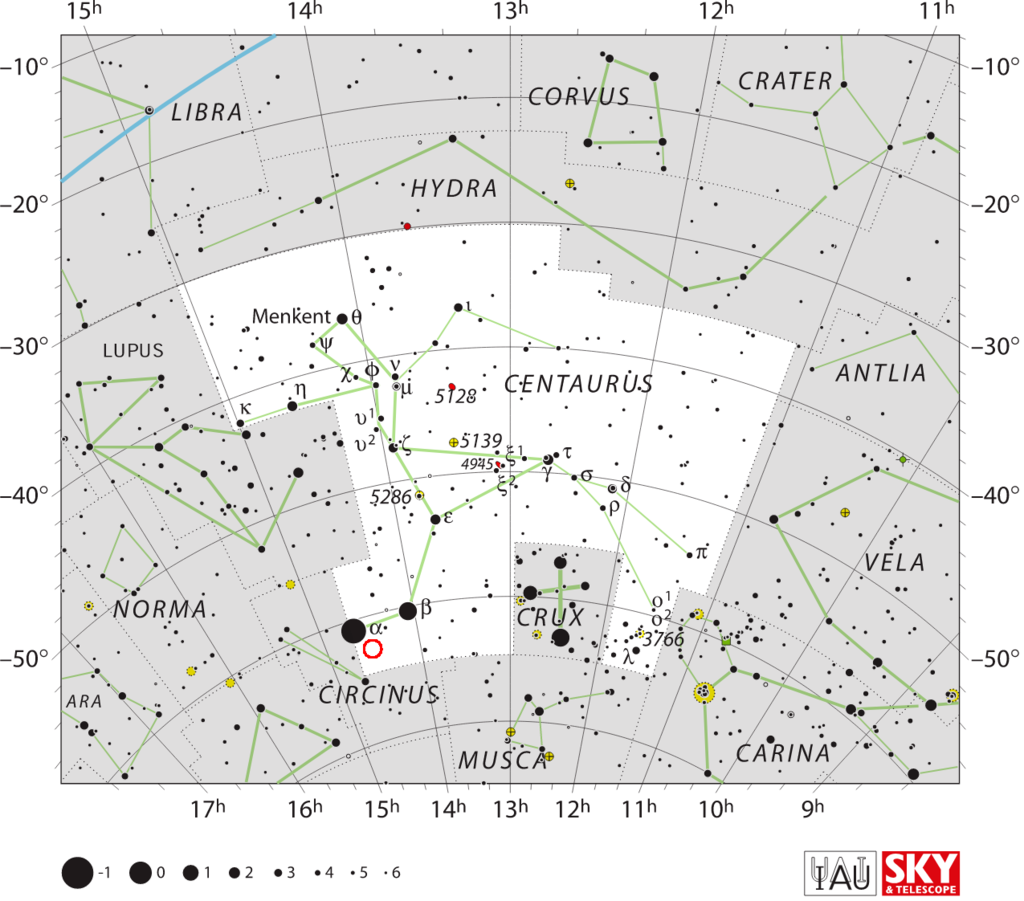

Proxima Centauri is the nearest star to Earth after the Sun, located 4.25 light years away in the southern constellation of Centaurus.

This object was discovered in 1915 by Robert Innes.

Above: South African astronomer Robert Innes (1861 – 1933)

It is a small, low-mass star, too faint to be seen with the naked eye, with an apparent magnitude of 11.13.

Its Latin name means the ‘nearest star of Centaurus‘.

Above: The location of Proxima Centauri (circled in red)

Proxima Centauri is a member of the Alpha Centauri star system, being identified as component Alpha Centauri C, and is 2.18° to the southwest of the Alpha Centauri AB pair.

It is currently 12,950 AU (0.2 light years) from AB, which it orbits with a period of about 550,000 years.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star with a mass about 12.5% of the Sun’s mass (M☉), and average density about 33 times that of the Sun.

Because of Proxima Centauri’s proximity to Earth, its angular diameter can be measured directly.

Its actual diameter is about one-seventh (14%) the diameter of the Sun.

Although it has a very low average luminosity, Proxima Centauri is a flare star that randomly undergoes dramatic increases in brightness because of magnetic activity.

The star’s magnetic field is created by convection throughout the stellar body.

The resulting flare activity generates a total X-ray emission similar to that produced by the Sun.

The internal mixing of its fuel by convection through its core and Proxima’s relatively low energy-production rate, mean that it will be a main-sequence star for another four trillion years.

Proxima Centauri has one known exoplanet and two candidate exoplanets:

- Proxima Centauri b

- the candidate Proxima Centauri d

- the disputed Proxima Centauri c.

Above: Schematic of the three planets (d, b, and c) of the Proxima Centauri system

Proxima Centauri b orbits the star at a distance of roughly 0.05 AU (7.5 million km) with an orbital period of approximately 11.2 Earth days.

Its estimated mass is at least 1.07 times that of Earth.

Proxima b orbits within Proxima Centauri’s habitable zone — the range where temperatures are right for liquid water to exist on its surface — but, because Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf and a flare star, the planet’s habitability is highly uncertain.

A candidate super-Earth, Proxima Centauri c, roughly 1.5 AU (220 million km) away from Proxima Centauri, orbits it every 1,900 days (5.2 years).

A candidate sub-Earth, Proxima Centauri d, roughly 0.029 AU (4.3 million km) away, orbits it every 5.1 days.

Moreover, the only way the stars could be so distant and still appear the sizes they do in the sky would be if even average stars were gigantic – at least as big as the orbit of the Earth, and of course vastly larger than the sun.

Galileo became involved in a dispute over priority in the discovery of sunspots with Christoph Scheiner, a Jesuit.

This became a bitter lifelong feud.

Above: German Jesuit astronomer Christoph Scheiner (1573 – 1650)

Neither of them, however, was the first to recognize sunspots:

The Chinese had already been familiar with them for centuries.

Above: Sol and sunspots

At this time, Galileo also engaged in a dispute over the reasons that objects float or sink in water, siding with Archimedes against Aristotle.

The debate was unfriendly.

Galileo’s blunt and sometimes sarcastic style, though not extraordinary in academic debates of the time, made him enemies.

Above: Greek scientist Archimedes (287 – 212 BC)

During this controversy one of Galileo’s friends, the painter Lodovico Cardi da Cigoli, informed him that a group of malicious opponents, which Cigoli subsequently referred to derisively as “the Pigeon League“, was plotting to cause him trouble over the motion of the Earth, or anything else that would serve the purpose.

According to Cigoli, one of the plotters asked a priest to denounce Galileo’s views from the pulpit, but the latter refused.

Above: Italian painter Ludovico Cardi da Cigoli (1559 – 1613)

Nevertheless, three years later another priest, Tommaso Caccini, did in fact do precisely that.

Above: Italian Dominican friar Tommaso Caccini (1574 – 1648)

In the Catholic world prior to Galileo’s conflict with the Church, the majority of educated people subscribed to the Aristotelian geometric view that the Earth was the centre of the universe and that all heavenly bodies revolved around the Earth, though Copernican theories were used to reform the calendar in 1582.

Above: Figure of the heavenly bodies – An illustration of a Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568

Geostaticism agreed with a literal interpretation of Scripture in several places, such as:

- 1 Chronicles 16:30

Tremble before him, all the Earth! The world is firmly established. It cannot be moved.

- Psalm 93:1

The Lord reigns. He is robed in majesty. The Lord is robed in majesty and armed with strength. Indeed, the world is established, firm and secure.

- Psalm 96:10

Say among the nations, “The Lord reigns.” The world is firmly established. It cannot be moved. He will judge the peoples with equity.

- Psalm 104:5

He set the Earth on its foundations. It can never be moved.

- Ecclesiastes 1:5

The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises.

- Job 26:7

He spreads out the northern skies over empty space. He suspends the Earth over nothing.

Heliocentrism, the theory that the Earth was a planet, which along with all the others revolved around the Sun, contradicted both geocentrism and the prevailing theological support of the theory.

Above: Christian painting of God creating the cosmos

One of the first suggestions of heresy that Galileo had to deal with came in 1613 from a professor of philosophy, poet and specialist in Greek literature, Cosimo Boscaglia.

In conversation with Galileo’s patron Cosimo II de’ Medici and Cosimo’s mother Christina of Lorraine, Boscaglia said that the telescopic discoveries were valid, but that the motion of the Earth was obviously contrary to Scripture:

Dr. Boscaglia had talked to Madame Christina for a while, and though he conceded all the things you have discovered in the sky, he said that the motion of the Earth was incredible and could not be, particularly since Holy Scripture obviously was contrary to such motion.”

Above: Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo II de’ Medici (1590 – 1621)

Above: Grand Duchess of Tuscany Christine de Lorraine (1565 – 1637)

Galileo was defended on the spot by his former student Benedetto Castelli, now a professor of mathematics and Benedictine abbot.

The exchange having been reported to Galileo by Castelli, Galileo decided to write a letter to Castelli, expounding his views on what he considered the most appropriate way of treating scriptural passages which made assertions about natural phenomena.

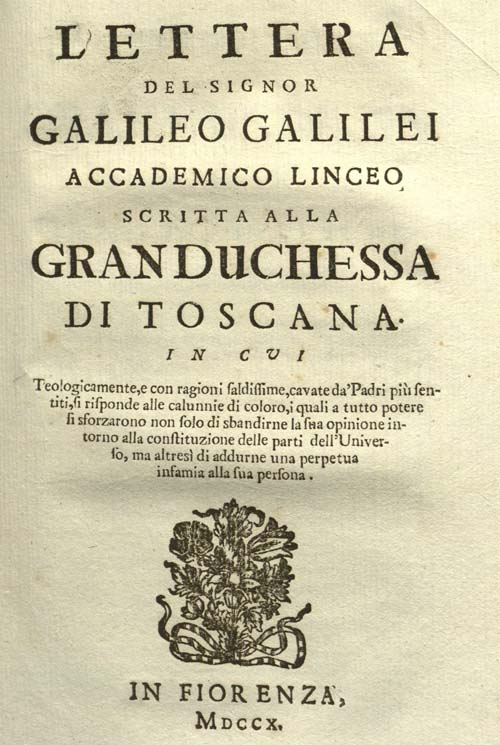

Later, in 1615, he expanded this into his much longer Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina.

Above: Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli (né Antonio Castelli) (1578 – 1643)

Tommaso Caccini, a Dominican friar, appears to have made the first dangerous attack on Galileo.

Preaching a sermon in Firenze (Florence) at the end of 1614, he denounced Galileo, his associates, and mathematicians in general (a category that included astronomers).

The Biblical text for the sermon on that day was Joshua 10, in which Joshua makes the Sun stand still.

This was the story that Castelli had to interpret for the Medici family the year before.

Above: Joshua makes the Sun stand still (Joshua 10: 1 – 15)

It is said, though it is not verifiable, that Caccini also used the passage from Acts 1:11:

“Men of Galilee”, they said. “Why do you stand here looking into the sky? This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into Heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into Heaven.”

In 1615, one of Caccini’s fellow Dominicans, Niccolò Lorini, acquired a copy of Galileo’s letter to Castelli.

Lorini and other Dominicans at the Convent of San Marco considered the letter of doubtful orthodoxy, in part because it may have violated the decrees of the Council of Trent:

…to check unbridled spirits, the Holy Council decrees that no one relying on his own judgement shall, in matters of faith and morals pertaining to the edification of Christian doctrine, distorting the Scriptures in accordance with his own conceptions, presume to interpret them contrary to that sense which the Holy Mother Church has held or holds.”

Decree of the Council of Trent (1545–1563)

Above: Council of Trento (Trent) (1545 – 1563)

Lorini and his colleagues decided to bring Galileo’s letter to the attention of the Inquisition.

In February 1615, Lorini accordingly sent a copy to the Secretary of the Inquisition, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati, with a covering letter critical of Galileo’s supporters:

All our Fathers of the devout Convent of St. Mark feel that the letter contains many statements which seem presumptuous or suspect, as when it states that the words of Holy Scripture do not mean what they say.

That in discussions about natural phenomena the authority of Scripture should rank last.

The followers of Galileo were taking it upon themselves to expound the Holy Scripture according to their private lights and in a manner different from the common interpretation of the Fathers of the Church.”

Letter from Lorini to Cardinal Sfrondato, Inquisitor in Rome, 1615

Above: (left) Italian Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati (1560 – 1618)

On 19 March, Caccini arrived at the Inquisition’s offices in Rome to denounce Galileo for his Copernicanism and various other alleged heresies supposedly being spread by his pupils.

Galileo soon heard reports that Lorini had obtained a copy of his letter to Castelli and was claiming that it contained many heresies.

He also heard that Caccini had gone to Rome and suspected him of trying to stir up trouble with Lorini’s copy of the letter.

As 1615 wore on Galileo became more concerned, and eventually determined to go to Rome as soon as his health permitted, which it did at the end of the year.

By presenting his case there, he hoped to clear his name of any suspicion of heresy, and to persuade the Church authorities not to suppress heliocentric ideas.

In going to Rome Galileo was acting against the advice of friends and allies, and of the Tuscan ambassador to Rome, Piero Guicciardini.

Above: The admonition of 1616

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, one of the most respected Catholic theologians of the time, was called on to adjudicate the dispute between Galileo and his opponents.

The question of heliocentrism had first been raised with Cardinal Bellarmine, in the case of Paolo Antonio Foscarini, a Carmelite father; Foscarini had published a book, Lettera sopra l’opinione del Copernico, which attempted to reconcile Copernicus with the Biblical passages that seemed to be in contradiction.

Bellarmine at first expressed the opinion that Copernicus’s book would not be banned, but would at most require some editing so as to present the theory purely as a calculating device for “saving the appearances” (i.e. preserving the observable evidence).

Foscarini sent a copy of his book to Bellarmine, who replied in a letter of 12 April 1615.

Galileo is mentioned by name in the letter, and a copy was soon sent to him.

After some preliminary salutations and acknowledgements, Bellarmine begins by telling Foscarini that it is prudent for him and Galileo to limit themselves to treating heliocentrism as a merely hypothetical phenomenon and not a physically real one.

Further on he says that interpreting heliocentrism as physically real would be “a very dangerous thing, likely not only to irritate all scholastic philosophers and theologians, but also to harm the Holy Faith by rendering Holy Scripture as false“.

Moreover, while the topic was not inherently a matter of faith, the statements about it in Scripture were so by virtue of who said them – namely, the Holy Spirit.

He conceded that if there were conclusive proof, “then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary, and say rather that we do not understand them, than that what is demonstrated is false“.

However, demonstrating that heliocentrism merely “saved the appearances” could not be regarded as sufficient to establish that it was physically real.

Although he believed that the former may well have been possible, he had “very great doubts” that the latter would be, and in case of doubt it was not permissible to depart from the traditional interpretation of Scriptures.

His final argument was a rebuttal of an analogy that Foscarini had made between a moving Earth and a ship on which the passengers perceive themselves as apparently stationary and the receding shore as apparently moving.

Bellarmine replied that in the case of the ship the passengers know that their perceptions are erroneous and can mentally correct them, whereas the scientist on the Earth clearly experiences that it is stationary and therefore the perception that the Sun, Moon and stars are moving is not in error and does not need to be corrected.

Bellarmine found no problem with heliocentrism so long as it was treated as a purely hypothetical calculating device and not as a physically real phenomenon, but he did not regard it as permissible to advocate the latter unless it could be conclusively proved through current scientific standards.

This put Galileo in a difficult position, because he believed that the available evidence strongly favored heliocentrism, and he wished to be able to publish his arguments.

Above: Italian Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542 – 1621)

In addition to Bellarmine, Monsignor Francesco Ingoli initiated a debate with Galileo, sending him in January 1616 an essay disputing the Copernican system.

Galileo later stated that he believed this essay to have been instrumental in the action against Copernicanism that followed in February.

According to philosopher Maurice Finocchiaro, Ingoli had probably been commissioned by the Inquisition to write an expert opinion on the controversy.

The essay provided the “chief direct basis” for the ban.

The essay focused on 18 physical and mathematical arguments against heliocentrism.

It borrowed primarily from the arguments of Tycho Brahe.

It notedly mentioned Brahe’s argument that heliocentrism required the stars to be much larger than the Sun.

Ingoli wrote that the great distance to the stars in the heliocentric theory “clearly proves the fixed stars to be of such size, as they may surpass or equal the size of the orbit circle of the Earth itself.”

Ingoli included four theological arguments in the essay, but suggested to Galileo that he focus on the physical and mathematical arguments.

Galileo did not write a response to Ingoli until 1624, in which, among other arguments and evidence, he listed the results of experiments such as dropping a rock from the mast of a moving ship.

On February 24, the Qualifiers delivered their unanimous report:

The proposition that the Sun is stationary at the centre of the Universe is “foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture“.

The proposition that the Earth moves and is not at the centre of the Universe “receives the same judgement in philosophy and in regard to theological truth it is at least erroneous in faith.“

At a meeting of the Cardinals of the Inquisition on the following day, Pope Paul V instructed Bellarmine to deliver this result to Galileo, and to order him to abandon the Copernican opinions.

Should Galileo resist the decree, stronger action would be taken.

On February 26, Galileo was called to Bellarmine’s residence and ordered,

to abstain completely from teaching or defending this doctrine and opinion or from discussing it, to abandon completely the opinion that the Sun stands still at the center of the world and the Earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing.”

The Inquisition’s injunction against Galileo, 1616

With no attractive alternatives, Galileo accepted the orders delivered, even sterner than those recommended by the Pope.

Galileo met again with Bellarmine, apparently on friendly terms.

On 11 March, he met with the Pope, who assured him that he was safe from prosecution so long as he, the Pope, should live.

Above: Italian Pope Paul V (né Camillo Borghese) (1550 – 1621)

Nonetheless, Galileo’s friends Sagredo and Castelli reported that there were rumors that Galileo had been forced to recant and do penance.

To protect his good name, Galileo requested a letter from Bellarmine stating the truth of the matter.

This letter assumed great importance in 1633, as did the question whether Galileo had been ordered not to “hold or defend” Copernican ideas (which would have allowed their hypothetical treatment) or not to teach them in any way.

If the Inquisition had issued the order not to teach heliocentrism at all, it would have been ignoring Bellarmine’s position.

In the end, Galileo did not persuade the Church to stay out of the controversy, but instead saw heliocentrism formally declared false.

It was consequently termed heretical by the Qualifiers, since it contradicted the literal meaning of the Scriptures, though this position was not binding on the Church.

Following the Inquisition’s injunction against Galileo, the papal Master of the Sacred Palace ordered that Foscarini’s Letter be banned, and Copernicus’ De revolutionibus suspended until corrected.

The papal Congregation of the Index preferred a stricter prohibition, and so with the Pope’s approval, on 5 March, the Congregation banned all books advocating the Copernican system, which it called “the false Pythagorean doctrine, altogether contrary to Holy Scripture“.

Francesco Ingoli, a consultor to the Holy Office, recommended that De revolutionibus be amended rather than banned due to its utility for calendrics.

In 1618, the Congregation of the Index accepted his recommendation, and published their decision two years later, allowing a corrected version of Copernicus’ book to be used.

The uncorrected De revolutionibus remained on the Index of banned books until 1758.

Galileo’s works advocating Copernicanism were therefore banned, and his sentence prohibited him from “teaching, defending or discussing” Copernicanism.

In Germany, Kepler’s works were also banned by the papal order.

In 1623, Pope Gregory XV died.

Above: Italian Pope Gregory XV (né Alessandro Ludovisi)(1554 – 1623)

He was succeeded by Pope Urban VIII who showed greater favor to Galileo, particularly after Galileo traveled to Rome to congratulate the new Pontiff.

Above: Italian Pope Urban VIII (né Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini)(1568 – 1644)

Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, which was published in 1632 to great popularity, was an account of conversations between a Copernican scientist, Salviati, an impartial and witty scholar named Sagredo, and a ponderous Aristotelian named Simplicio, who employed stock arguments in support of geocentricity, and was depicted in the book as being an intellectually inept fool. Simplicio’s arguments are systematically refuted and ridiculed by the other two characters with what Youngson calls “unassailable proof” for the Copernican theory (at least versus the theory of Ptolemy – as Finocchiaro points out, “the Copernican and Tychonic systems were observationally equivalent and the available evidence could be explained equally well by either“), which reduces Simplicio to baffled rage, and makes the author’s position unambiguous.

Indeed, although Galileo states in the preface of his book that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher (Simplicius in Latin, Simplicio in Italian), the name “Simplicio” in Italian also had the connotation of “simpleton“.

Authors Langford and Stillman Drake asserted that Simplicio was modeled on philosophers Lodovico delle Colombe and Cesare Cremonini.

Pope Urban demanded that his own arguments be included in the book, which resulted in Galileo putting them in the mouth of Simplicio.

Some months after the book’s publication, Pope Urban VIII banned its sale and had its text submitted for examination by a special commission.

With the loss of many of his defenders in Rome because of Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, in 1633 Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy “for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world” against the 1616 condemnation, since “it was decided at the Holy Congregation on 25 February 1616 that the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned“.

On 13 February 1633, Galileo Galilei arrives in Rome for his trial before the Inquisition.

Galileo was interrogated while threatened with physical torture.

A panel of theologians, consisting of Melchior Inchofer, Agostino Oreggi and Zaccaria Pasqualigo, reported on the Dialogue.

Their opinions were strongly argued in favor of the view that the Dialogue taught the Copernican theory.

Galileo was found guilty.

The sentence of the Inquisition, issued on 22 June 1633, was in three essential parts:

- Galileo was found “vehemently suspect of heresy“, namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to “abjure, curse, and detest” those opinions.

- He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition. On the following day this was commuted to house arrest, which he remained under for the rest of his life.

- His offending Dialogue was banned and, in an action not announced at the trial, publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.

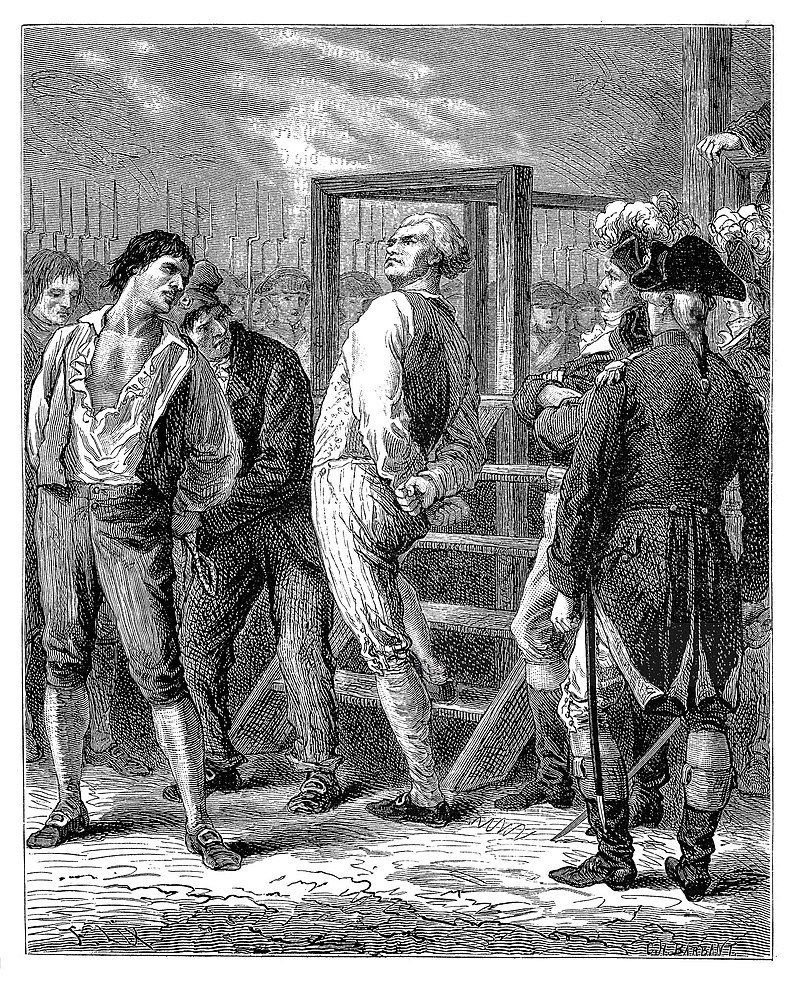

Above: The trial of Galileo Galilei before the Inquisition (1633)

According to popular legend, after his abjuration Galileo allegedly muttered the rebellious phrase “and yet it moves” (Eppur si muove), but there is no evidence that he actually said this or anything similar.

The first account of the legend dates to a century after his death.

The phrase “Eppur si muove” does appear, however, in a painting of the 1640s by the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

The painting depicts an imprisoned Galileo apparently pointing to a copy of the phrase written on the wall of his dungeon.

Above: Galileo in prison, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1837)

Galileo Galilei is depicted as holding a nail and gazing at diagrams he has scratched on the wall of his prison cell.

Underneath a diagram of the Earth orbiting the Sun, he has scratched the words “E pur si muove” (not completely legible in this image)

The Inquisitors stand in their robes of power, demanding submission.

Galileo, the man who dared to challenge the heavens, understands the cost of truth.

He looks into the abyss of martyrdom and chooses life instead.

He whispers under his breath — E pur si muove — and with that whisper, acknowledges the price of honesty in a world unready for it.

Above: Galileo before the Inquisition (1633)

After a period with the friendly Archbishop Piccolomini in Siena, Galileo was allowed to return to his villa at Arcetri near Florence, where he spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

Above: Shovel of Ascanio Piccolomini (1596 – 1671) in the Accademia della Crusca, Firenze, Italia

Galileo continued his work on mechanics.

In 1638 he published a scientific book in Holland.

His standing would remain questioned at every turn.

In March 1641, Vincentio Reinieri, a follower and pupil of Galileo, wrote him at Arcetri that an Inquisitor had recently compelled the author of a book printed at Florence to change the words “most distinguished Galileo” to “Galileo, man of noted name“.

However, partially in tribute to Galileo, at Arcetri the first academy devoted to the new experimental science, the Accademia del Cimento, was formed, which is where Francesco Redi performed controlled experiments, and many other important advancements were made which would eventually help usher in the Age of Enlightenment.

Above: Galileo Galilei

The Galileo affair was largely forgotten after Galileo’s death.

The controversy subsided.

The Inquisition’s ban on reprinting Galileo’s works was lifted in 1718 when permission was granted to publish an edition of his works (excluding the condemned Dialogue) in Firenze.

Above: Ponte Vecchio, Firenze, Italia

In 1741, Pope Benedict XIV authorized the publication of an edition of Galileo’s complete scientific works which included a mildly censored version of the Dialogue.

In 1758, the general prohibition against works advocating heliocentrism was removed from the Index of Prohibited Books.

However, the specific ban on uncensored versions of the Dialogue and Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus remained.

All traces of official opposition to heliocentrism by the Church disappeared in 1835 when these works were finally dropped from the Index.

Above: Italian Pope Benedict XIV (né Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini)(1675 – 1758)

Interest in the Galileo affair was revived in the early 19th century when Protestant polemicists used it (and other events such as the Spanish Inquisition and the myth of the flat Earth) to attack Roman Catholicism.

Interest in it has waxed and waned ever since.

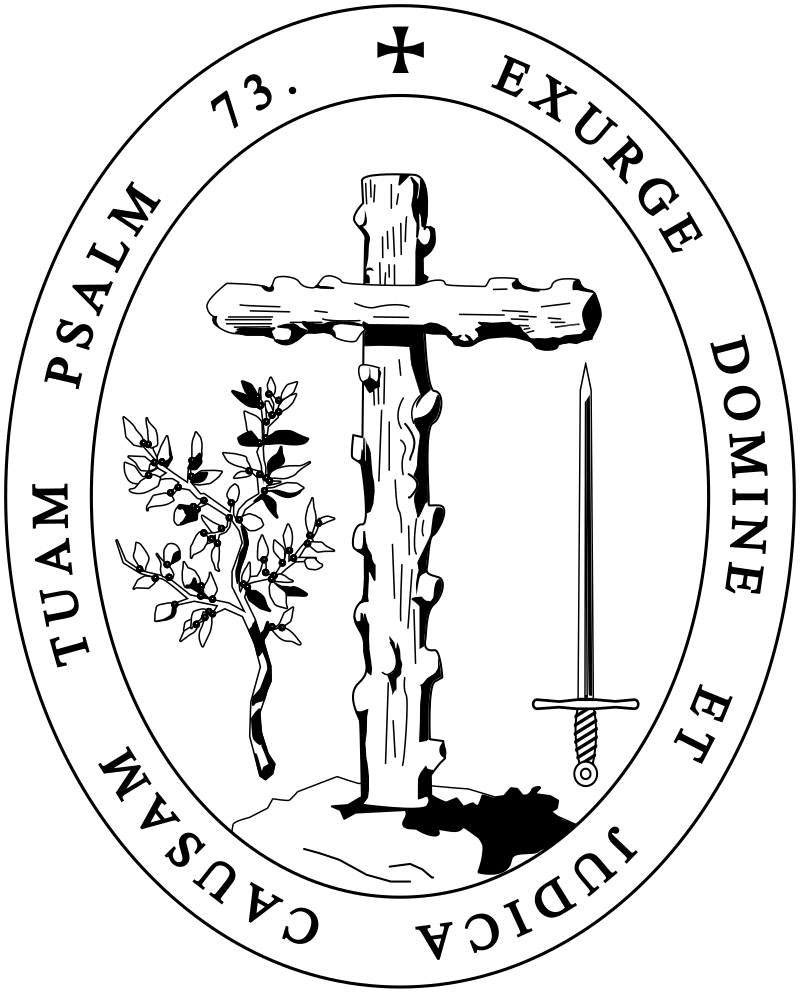

Above: Seal of the Spanish Inquisition (1478 – 1834)

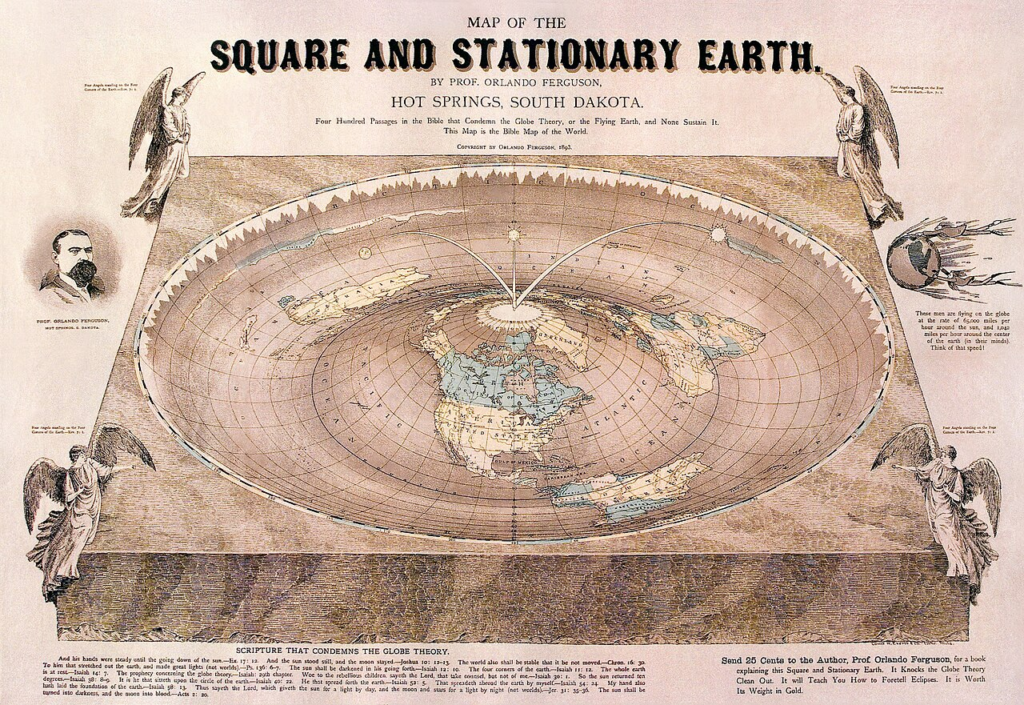

Above: Flat Earth map, Orlando Ferguson (1893)

In 1939, Pope Pius XII, in his first speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, within a few months of his election to the papacy, described Galileo as being among the “most audacious heroes of research not afraid of the stumbling blocks and the risks on the way nor fearful of the funereal monuments“.

His close advisor of 40 years, Professor Robert Leiber, wrote:

“Pius XII was very careful not to close any doors to science prematurely.

He was energetic on this point and regretted that in the case of Galileo.“

Above: Italian Pope Pius XII (né Eugenio Pacelli)(1876 – 1958)

On 15 February 1990, in a speech delivered at the Sapienza University of Rome, Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) cited some current views on the Galileo affair as forming what he called “a symptomatic case that permits us to see how deep the self-doubt of the modern age, of science and technology goes today“.

Some of the views he cited were those of the philosopher Paul Feyerabend, whom he quoted as saying:

“The Church at the time of Galileo kept much more closely to reason than did Galileo himself, and it took into consideration the ethical and social consequences of Galileo’s teaching too.

Its verdict against Galileo was rational and just and the revision of this verdict can be justified only on the grounds of what is politically opportune.”

The Cardinal did not clearly indicate whether he agreed or disagreed with Feyerabend’s assertions.

He did, however, say:

“It would be foolish to construct an impulsive apologetic on the basis of such views.“

Above: German Pope Benedict XVI (né Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger)(1927 – 2022)

On 31 October 1992, Pope John Paul II acknowledged that the Inquisition had erred in condemning Galileo for asserting that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

“John Paul said the theologians who condemned Galileo did not recognize the formal distinction between the Bible and its interpretation.“

Above: Polish Pope John Paul II (né Karol Józef Wojtyła)(1920 – 2005)

In March 2008, the head of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Nicola Cabibbo, announced a plan to honor Galileo by erecting a statue of him inside the Vatican walls.

Above: Emblem of the Papacy

In December of the same year, during events to mark the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s earliest telescopic observations, Pope Benedict XVI praised his contributions to astronomy.

A month later, however, the head of the Pontifical Council for Culture, Gianfranco Ravasi, revealed that the plan to erect a statue of Galileo on the grounds of the Vatican had been suspended.

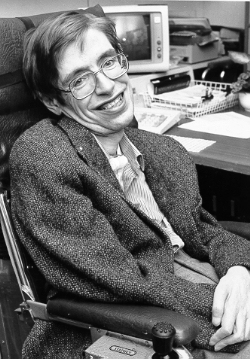

According to Stephen Hawking, Galileo probably bears more of the responsibility for the birth of modern science than anybody else.

Above: English physicist Stephen Hawking (1942 – 2018)

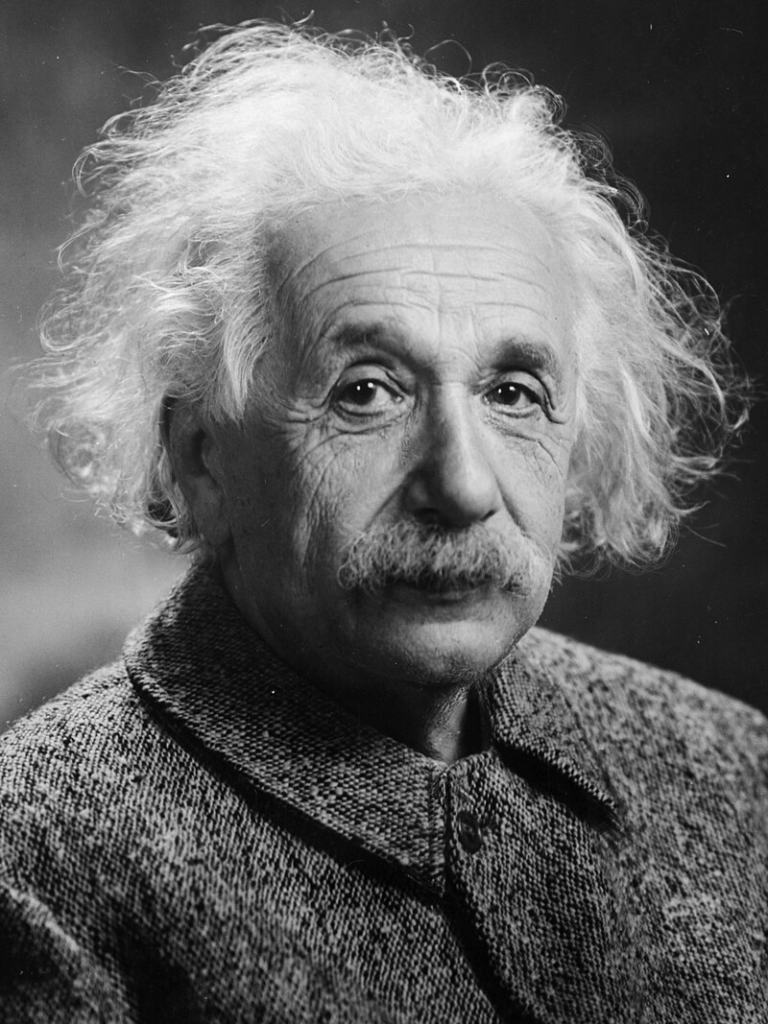

Albert Einstein called him the father of modern science.

In a foreword to Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Einstein wrote:

“The leitmotif I recognize in Galileo’s work is the passionate fight against any kind of dogma based on authority.

Only experience and careful reflection are accepted by him as criteria of truth.”

Above: German physicist Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

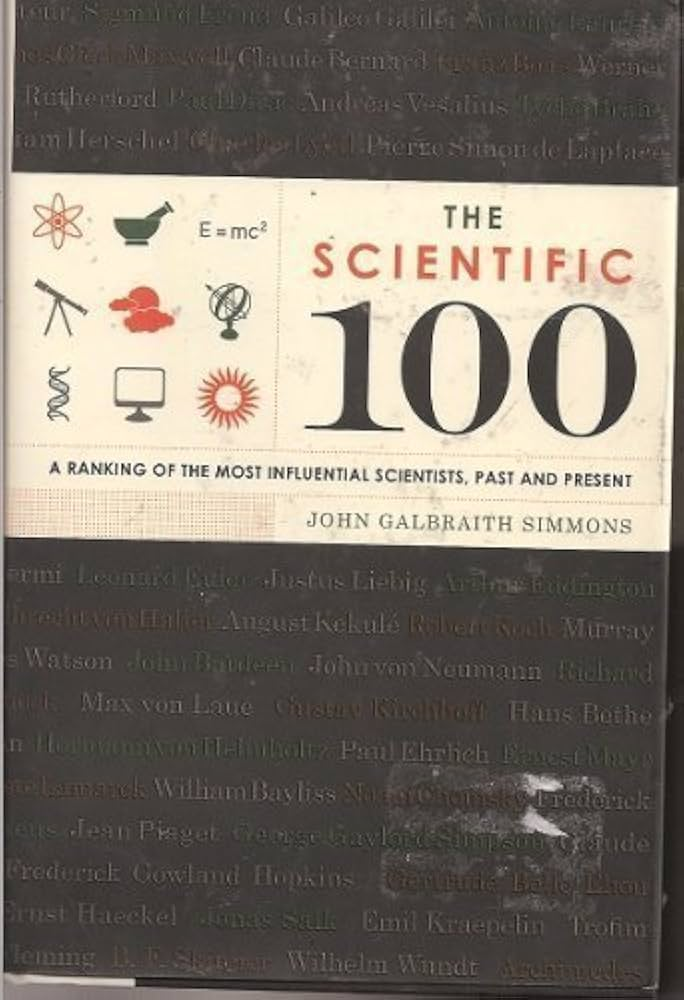

Author John G. Simmons notes Galileo’s place in the history of science as the embracing of a new outlook on science, stating that:

But perhaps most significant, Galileo epitomized a new scientific outlook.

By his rhetoric, supported by mathematical reasoning, and the force of his personality, Galileo helped to establish the Copernican model of the solar system as a revolution in science.”

Galileo’s astronomical discoveries and investigations into the Copernican theory have led to a lasting legacy which includes the categorization of the four large moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo (Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto) as the Galilean moons.

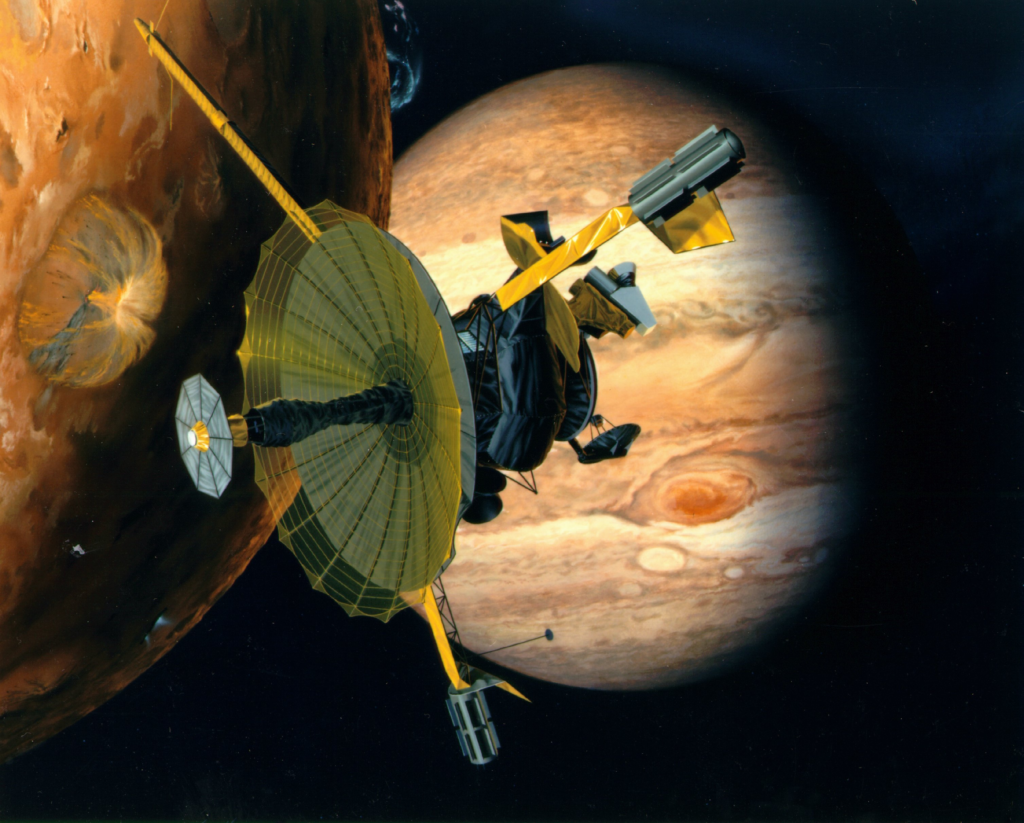

Other scientific endeavours and principles are named after Galileo including the Galileo spacecraft.

Above: Galileo (1989 – 2003)

Partly because the year 2009 was the 4th centenary of Galileo’s first recorded astronomical observations with the telescope, the United Nations scheduled it to be the International Year of Astronomy.

Galileo Galilei arrived in Rome on this day in 1633 to stand before the Inquisition, accused of heresy for championing a simple but radical truth:

The Earth moves around the Sun.

The Church, entrenched in dogma, saw this as a threat to its authority.

Galileo, a man of reason, was forced to recant, yet history would vindicate him.

The battle between knowledge and power is eternal.

What happens when truth is deemed too dangerous to be spoken?

Ivan Andreyevich Krylov (13 February 1769 – 21 November 1844) is Russia’s best-known fabulist and probably the most epigrammatic of all Russian authors.

Formerly a dramatist and journalist, he only discovered his true genre at the age of 40.

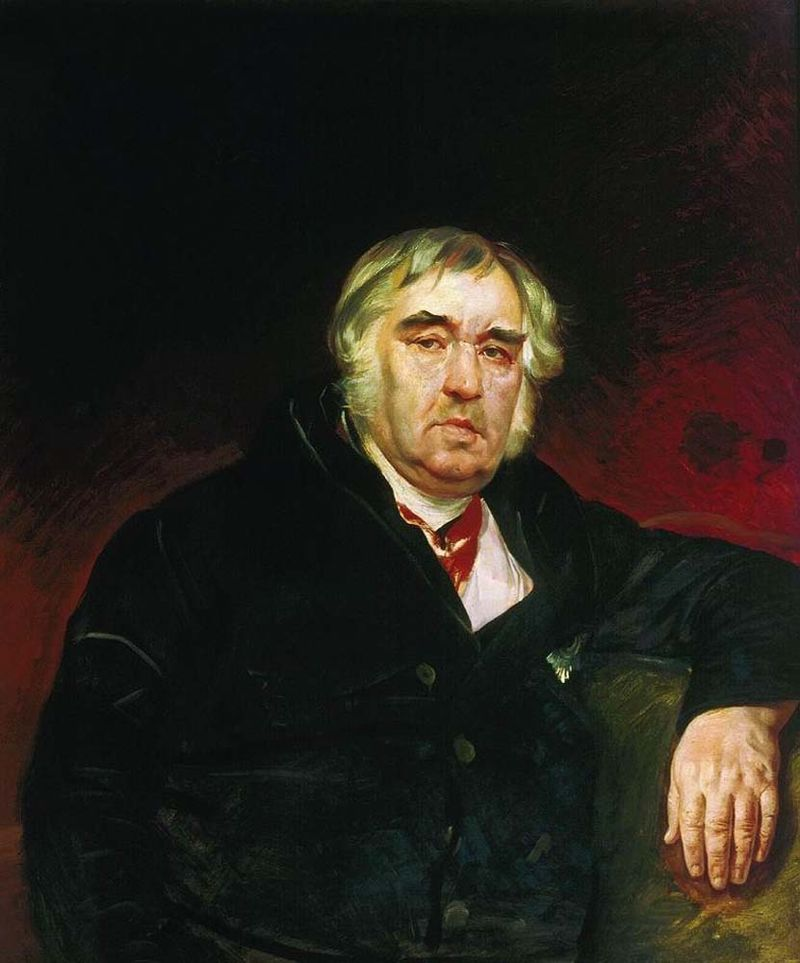

Above: Russian writer Ivan Krylov

While many of his earlier fables were loosely based on Aesop’s and La Fontaine’s, later fables were original work, often with a satirical bent.

Above: Bust of Greek storyteller Aesop (620 – 564 BC)

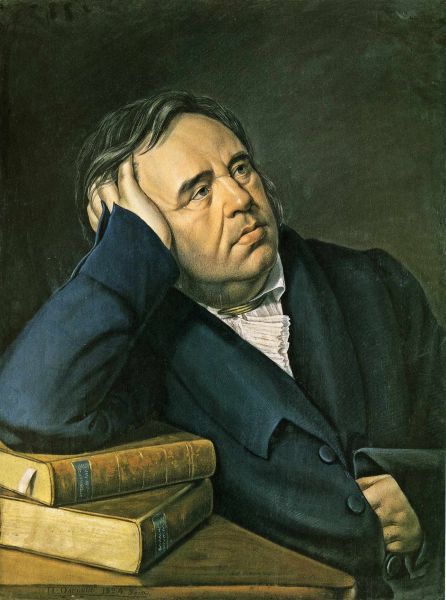

Above: French poet Jean de la Fontaine (1621 – 1695)

Ivan Krylov was born in Moscow, but spent his early years in Orenburg and Tver.

Above: Moscow, Russia

His father, a distinguished military officer, resigned in 1775 and died in 1779, leaving the family destitute.

A few years later Krylov and his mother moved to St. Petersburg in the hope of securing a government pension.

There, Krylov obtained a position in the civil service, but gave it up after his mother’s death in 1788.

Above: St. Petersburg, Russia

His literary career began in 1783, when he sold to a publisher the comedy “The coffee grounds fortune teller” (Kofeynitsa) that he had written at 14, although in the end it was never published or produced.

Above: Krylov Monument, Summer Garden, St. Petersburg

Receiving a sixty ruble fee, he exchanged it for the works of Molière, Racine, and Boileau.

Above: French writer Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (aka Molière)(1622 – 1673)

Above: French writer Jean-Baptiste Racine (1639 – 1699)

Above: French poet Nicholas Boileau-Despréaux (1636 – 1711)

It was probably under their influence that he wrote his other plays, of which his Philomela (written in 1786) was not published until 1795.

Above: Krylov on Soviet stamp (1959)

Beginning in 1789, Krylov also made three attempts to start a literary magazine, although none achieved a large circulation or lasted more than a year.

Despite this lack of success, their satire and the humor of his comedies helped the author gain recognition in literary circles.

Above: Ivan Krylov

For about four years (1797 – 1801) Krylov lived at the country estate of Prince Sergey Galitzine, and when the Prince was appointed military governor of Livonia, he accompanied him as a secretary and tutor to his children, resigning his position in 1803.

Above: Flag of Livonia

Little is known of him in the years immediately after, other than the commonly accepted myth that he wandered from town to town playing cards.

Above: Ivan Krylov

By 1806 he had arrived in Moscow, where he showed the poet and fabulist Ivan Dmitriev his translation of two of Jean de La Fontaine’s Fables, “The Oak and the Reed” and “The Choosy Bride“.

He was encouraged to write more.

Above: Illustration from La Fontaine’s Fables

Soon, however, Krylov moved on to St Petersburg and returned to play writing with more success, particularly with the productions of “The Fashion Shop” (Modnaya lavka) and “A Lesson For the Daughters” (Urok dochkam).

These satirised the nobility’s attraction to everything French, a fashion he detested all his life.

Krylov’s first collection of fables, 23 in number, appeared in 1809 and met with such an enthusiastic reception that thereafter he abandoned drama for fable writing.

By the end of his career he had completed some 200, constantly revising them with each new edition.

From 1812 to 1841 he was employed by the Imperial Public Library, first as an assistant, and then as head of the Russian Books Department, a not very demanding position that left him plenty of time to write.

Above: Russian National Library, St. Petersburg, Russia

Honors were now showered on him in recognition of his growing reputation:

The Russian Academy of Sciences admitted him as a member in 1811 and bestowed on him its gold medal in 1823.

Above: Logo of the Russian Academy of Sciences

In 1838 a great festival was held in his honor under imperial sanction, and the Emperor Nicholas, with whom he was on friendly terms, granted him a generous pension.

Above: Russian Emperor Nicholas I (1796 – 1855)

After 1830 Krylov wrote little and led an increasingly sedentary life.

A multitude of half-legendary stories were told about his laziness, his gluttony and the squalor in which he lived, as well as his witty repartee.

Above: Ivan Krylov

Towards the end of his life Krylov suffered two cerebral hemorrhages and was taken by the Empress to recover at Pavlovsk Palace.

Above: Pavlovsky Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia

After his death in 1844, he was buried in the Tikhvin Cemetery.

Above: Tikhvin Cemetery, St. Petersburg, Russia

By the time of Krylov’s death, 77,000 copies of his fables had been sold in Russia.

His unique brand of wisdom and humor has remained popular ever since.

His fables were often rooted in historic events and are easily recognizable by their style of language and engaging story.

Though he began as a translator and imitator of existing fables, Krylov soon showed himself an imaginative prolific writer, who found abundant original material in his native land and in the burning issues of the day.

Above: The oak and the reed (from Krylov’s fable), Achille Michallon (1816)

Occasionally this was to lead into trouble with government censors, who blocked publication of some of his work.

In the case of “The Grandee” (1835), it was only allowed to be published after it became known that Krylov had amused the Emperor by reading it to him, while others did not see the light until long after his death, such as “The Speckled Sheep“, published in 1867, and “The Feast” in 1869.

Beside the fables of La Fontaine, and one or two others, the germ of some of Krylov’s other fables can be found in Aesop, but always with his own witty touch and reinterpretation.

In Russia his language is considered of high quality:

His words and phrases are direct, simple and idiomatic, with color and cadence varying with the theme, many of them becoming actual idioms.

His animal fables blend naturalistic characterization of the animal with an allegorical portrayal of basic human types.

They span individual foibles as well as difficult interpersonal relations.

Many of Krylov’s fables, especially those that satirize contemporary political situations, take their start from a well-known fable but then diverge.

Krylov’s “The Peasant and the Snake” makes La Fontaine’s “The Countryman and the Snake” the reference point as it relates how the reptile seeks a place in the peasant’s family, presenting itself as completely different in behavior from the normal run of snakes.

To Krylov’s approbation, with the ending of La Fontaine’s fable in mind, the peasant kills it as untrustworthy.

Above: The countryman and the snake, La Fontaine’s Fables

“The Council of the Mice” uses another fable of La Fontaine (II.2) only for scene-setting.

Its real target is cronyism and Krylov dispenses with the deliberations of the mice altogether.

Above: The Council of the Mice, La Fontaine’s Fables

The connection between Krylov’s “The Two Boys” and La Fontaine’s “The Monkey and the Cat” is even thinner.

Though both fables concern being made the dupe of another, Krylov tells of how one boy, rather than picking chestnuts from the fire, supports another on his shoulders as he picks the nuts and receives only the rinds in return.

Fables of older date are equally laid under contribution by Krylov.

Above: The monkey and the cat, La Fontaine’s Fables

“The Hawk and the Nightingale” is transposed into a satire on censorship in “The Cat and the Nightingale“.

The nightingale is captured by a cat so that it can hear its famous song, but the bird is too terrified to sing.

In one of the mediaeval versions of the original story, the bird sings to save its nestlings but is too anxious to perform well.

Above: The hawk and the nightingale, Croxall’s The Fables of Aesop

Again, in his “The Hops and the Oak“, Krylov merely embroiders on one of the variants of “The Elm and the Vine” in which an offer of support by the tree is initially turned down.

In the Russian story, a hop vine praises its stake and disparages the oak until the stake is destroyed, whereupon it winds itself about the oak and flatters it.

Above: Grape gathering from elm trellises in Italy (1849)

Establishing the original model of some fables is problematical, however, and there is disagreement over the source for Krylov’s “The swine under the oak“.

There, a pig eating acorns under an oak also grubs down to the roots, not realizing or caring that this will destroy the source of its food.

A final verse likens the action to those who fail to honor learning although benefitting from it.

In his Bibliographical and Historical Notes to the fables of Krilof (1868), the Russian commentator V.F.Kenevich sees the fable as referring to Aesop’s “The Travellers and the Plane Tree“.

Although that has no animal protagonists, the theme of overlooking the tree’s usefulness is the same.

Above: The “useless” fruit of the plane tree

On the other hand, the French critic Jean Fleury points out that Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s fable of “The Oak Tree and the Swine“, a satirical reworking of Aesop’s “The Walnut Tree“, is the more likely inspiration, coalescing as it does an uncaring pig and the theme of a useful tree that is maltreated.

Above: German philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781)

I am reminded of Krylov’s “The Quartet“:

A rascal monkey, a donkey, a billy goat and a klunky bear set out to play a string quartet.

They found some scores, viola, bass and two violins and sat down in a lea beneath a linden tree to charm the world with their art.

They struck their strings and sawed with all their heart.

No luck.

“Arrete, my fellows, stop!“, shouts the monkey.

“Wait! How can the music play when you’re not sitting straight?

You, bear, opposite viola move your bass,

As primo, I’ll sit opposite secundo’s face

And then some music will take place.

We’ll make the hills and forests dance!“

They took their seats and started the Quartet,

And once again it came to nyet.

“Hold on! I know the secret!“, shouts the donkey.

“It is bound to come out fine

If everyone sits in a line.“

They followed the donkey’s plan and settled in a row;

But even so, the music would not go.

More fiercely than before they argued then about who should be sitting where.

A nightingale, in passing, chanced the noise to hear.

At once, they turned to her to solve their problem.

They pleaded:

“Please, spare us some time to make of our quartet a paradigm:

We have our instruments and scores, just tell us how to sit!“

“For making music, you must have the knack and ears more musical than yours.“, the nightingale comes back.

“And you, my friends, no matter your positions,

Will never be musicians!“

Above: The quartet

Four animals attempt to play music together, each convinced of their own talents.

They fail, not because they lack skill, but because they refuse to recognize the truth about themselves.

They cannot work together, for their egos demand a reality that does not exist.

The audience laughs, but beneath the laughter lies an uncomfortable lesson.

Above: The quartet

Sunset Boulevard is a 1950 American black comedy film noir directed and co-written by Billy Wilder (1906 – 2002).

It is named after a major street that runs through Hollywood.

At a mansion on Sunset Boulevard, police officers and photographers discover the body of Joe Gillis (William Holden) floating face down in the swimming pool.

In a flashback, Joe relates the events leading to his death.

Above: American actor William Holden (1918 – 1981)

Six months earlier, Joe, a down-on-his-luck screenwriter, tries to interest Paramount Pictures in a story he submitted.

Script reader Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson) harshly critiques it, unaware that Joe is listening.

Above: American actress Nancy Olson

Later, while fleeing from repo men seeking his car, Joe turns into the driveway of a seemingly deserted mansion inhabited by forgotten silent film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson).

Above: American actress Gloria Swanson (1899 – 1983)

Joe Gillis:

You’re Norma Desmond.

You used to be in silent pictures.

You used to be big.

Norma Desmond:

I am big.

It’s the pictures that got small.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

Learning that Joe is a writer, Norma asks his opinion of a script she has written for a film about Salome.

She plans to play the role herself in her return to the screen.

Above: Jewish princess Salome III with John the Baptist’s head

Joe finds her script abysmal but flatters her into hiring him as a script doctor.

Joe moves into Norma’s mansion at her insistence and sees that Norma refuses to believe that her fame has evaporated.

Her butler, Max (Erich von Stroheim), secretly writes all of the fan mail she receives in order to maintain the illusion.

Above: Austrian actor Erich von Stroheim (1885 – 1957)

At her New Year’s Eve party, Joe realizes that she has fallen in love with him.

He tries to let her down gently, but Norma slaps him and retreats to her room, distraught.

Above: New Year’s Eve party scene, Sunset Boulevard

Joe visits his friend Artie Green (Jack Webb) and again meets Betty, who thinks a scene in one of Joe’s scripts has potential.

When he phones Max to have him pack his things, Max tells him Norma has cut her wrists with his razor.

Above: American actor Jack Webb (1920 – 1982)

Joe then returns to Norma.

Their relationship becomes sexual.

Norma has Max deliver the edited Salome script to her former director Cecil B. DeMille (as himself) at Paramount.

She starts getting calls from Paramount executive Gordon Cole but refuses to speak to anyone except DeMille.

Above: American filmmaker Cecile DeMille (1881 – 1959)

Eventually, she has Max drive her and Joe to Paramount in her 1929 Isotta Fraschini.

DeMille welcomes her affectionately and treats her with great respect but tactfully evades her questions about the script.

Max then learns that Cole only called her because he wants to rent her Isotta Fraschini for use in a film.

Above: 1929 Isotta Fraschini

Preparing for her imagined comeback, Norma undergoes rigorous beauty treatments.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

Joe secretly works nights in Betty’s office, collaborating on an original screenplay.

She eventually confesses she has fallen for him.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

After learning of Joe’s moonlighting, Max reveals he was once a respected film director who discovered Norma, made her a star, and became her first husband.

Following their divorce, he abandoned his career to become her servant.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

Norma discovers a manuscript with Joe and Betty’s names on it and phones Betty, insinuating that Joe is not the man he seems.

Overhearing the call, Joe invites Betty to the mansion to see for herself.

When she arrives, he pretends that he is satisfied being a gigolo so that she can be with Artie.

However, after she tearfully leaves, he packs to return to his old newspaper job in Dayton, Ohio.

Above: Dayton, Ohio, USA

He bluntly informs Norma that there will be no comeback, that Max writes all of her fan mail, and that she has been forgotten, though Max refuses to break her delusions.

Joe disregards Norma’s threat to kill herself as she brandishes a gun.

As he leaves the house, Norma shoots him three times.

He collapses into the pool.

The flashback ends.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

The film returns to the present day, with Norma about to be arrested for murder.

The mansion is overrun with police and reporters with newsreel cameras, which she believes are film cameras.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

Joe Gillis:

Well, this is where you came in.

Back at that pool again, the one I always wanted.

It’s dawn now, and they must have photographed me a thousand times.

Then they got a couple of pruning hooks from the garden and fished me out, ever so gently.

Funny how gentle people get with you once you’re dead.

They beached me like a harpooned baby whale and started to check the damage, just for the record.

By this time, the whole joint was jumping – cops, reporters, neighbors, passersby, as much hoop-de-doo as we get in Los Angeles when they open a supermarket.

Even the newsreel guys came roaring in.

Here was an item everybody could have some fun with, the heartless so-and-sos!

What would they do to Norma?

Even if she got away with it in court – crime of passion, temporary insanity – those headlines would kill her:

‘Forgotten Star a Slayer‘

‘Aging Actress‘

‘Yesterday’s Glamour Queen‘…

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

Max pretends to “direct” her.

The police play along.

As the cameras roll, Norma descends the grand staircase.

Upon reaching the bottom, she stops and makes an impromptu speech about how happy she is to be making a film again.

She then says, “Alright, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” and approaches the camera.

Above: Scene from Sunset Boulevard

The street known as Sunset Boulevard has been associated with Hollywood film production since 1911, when the town’s first film studio, Nestor, opened there.

Above: Logo of Nestor Film Company (1909 – 1920)

The film workers lived modestly in the growing neighborhood, but during the 1920s, profits and salaries rose to unprecedented levels.

With the advent of the star system, luxurious homes noted for their often incongruous grandeur were built in the area.

Above: Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, California, USA

As a young man living in Berlin in the 1920s, Billy Wilder was interested in American culture, with much of his interest fueled by the country’s films.

In the late 1940s, many of the grand Hollywood houses remained, and Wilder, then a Los Angeles resident, found them to be a part of his everyday world.

Many former stars from the silent era still lived in them, although most were no longer involved in the film business.

Wilder wondered how they spent their time now that “the parade had passed them by” and began imagining the story of a star who had lost her celebrity and box-office appeal.

Above: Polish filmmaker Billy Wilder