“Life is other than what we write.“

André Breton, Nadja (1928)

Friday 7 March 2025

Landschlacht, Schweiz

Above: Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Literature is both a mirror and a chisel:

One reflecting the world as it is.

The other carving out the world as it could be.

This blog may not be literature, but the concept is the same.

There is what is.

There is what should be.

Above: St. Leonhard’s Chapel, Landschlacht

I have a golden opportunity to spend 3.5 months in relative leisure that should be used to write.

The reality is that my world here is filled with distraction and interruption.

I have a man cold:

Stuffed nose, coughing, sinus headache.

The body craves sleep, but the mind is restless.

Am I never happy?

This involuntary banishment is an opportunity and yet I cannot but feel it is a punishment.

I am dealing with the situation as best as I can.

I have contacted Eskişehir to maintain my apartment and my online lessons during my absence.

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Switzerland

I have visited St. Gallen in search of work, but I don’t want to pretend that I seek fulltime employment that I will then just abandon after a mere three months.

So instead I wander the streets.

St. Gallen is a museum of my history.

I did that there.

I worked over here.

Above: St. Gallen, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

Persons A, B and C have moved on.

Persons X, Y and Z are still here.

X has changed her apartment, her relationship status, her hair.

Her job remains the same, because she is a realist.

Some things are unwise to change.

Some things must go.

Y tells me of A, B and C.

A has his own store, has married, has a child, is apparently deliriously happy.

B still has his own store, remains happy as husband and father, continues to prosper.

C found a new girlfriend with whom he lives, still in physical pain but emotionally healthy.

Y’s life remains the same.

She is as constant as the North Star.

Z remains active – her own business, raising a daughter on her own.

Hasn’t got time for the pain or much else for that matter.

And tell me, I am asked, what’s new with you?

Not much.

Worked at one school 3.5 years, at another 3.5 months, and ended at a third for 3.5 weeks.

Will be in Switzerland for 3.5 months before returning back to Eskişehir and Türkiye.

Uncertain if that return is a loss or a win.

Above: Flag of Switzerland

I have dined out with the wife already three times this week.

Monday afternoon coffee at street café Sorriso in Kreuzlingen.

Reason for being in Kreuzlingen?

Above: Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Shopping for shoes for me.

Apparently my Eskişehir-repaired shoes resemble an old tramp’s.

Above: Charlie Chaplin, The Tramp (1915)

Salad and cola and potato chips from grocery store.

Walk along Bohmer Wiehre – a pond beyond the city centre.

Tuesday dinner at the Rotes Haus, a half-timbered house in the village of Landschlacht, an Italian restaurant on Highway 13, my first taste of gluten-free pizza in months.

The wife doesn’t want to cook after a long hard slog of work.

I don’t cook in a kitchen whose geography I do not dare disturb.

Ordnung ist Alles.

Order is everything.

A place for everything and everything in its place.

I was meant to be a guest for five days, not a lodger for 15 weeks.

Guests don’t need to know where things go.

Lodgers learn quickly.

Above: Rotes Haus Restaurant, Landschlacht

Wednesday lunch at the Ignaz Restaurant, across from the main train station in Konstanz – a shopping trip for food and clothes.

Potato soup and skewered lamb for lunch.

Above: Brasserie Ignaz, Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

I accompany her about town, led around like a helpless child whose impatient parent tries to tolerate her charge’s reluctance.

Three months linger longer than three months.

Above: Konstanz, Germany

Yesterday, a return to St. Gallen for a reunion with old friend/former student.

I clandestinely restart to build my home library from Orell Füseli and Lüthy bookshops.

There will be books in Landschlacht.

Books will be luggage to Eskişehir.

Already a dozen added to collection.

Meet friend in town.

Gluten-free spaghetti carbonara, cola and espresso at Dolce Lucia Italian restaurant.

Tea at Benedikt Buchcafé.

Coffee at Chocolaterie.

My friend has found religion.

Or has religion found him?

Above: The conversion of Saul into Paul the Apostle on the road to Damascus

Zealot seeks to seduce me to his cause.

I am unmoved but remain polite.

Our sole subject:

My soul.

Heathen hesitation harried.

Did I become Muslim?

No, I respond.

Like Groucho Marx, I refuse to join any organization that unwisely welcomes me into its ranks.

He does not see the humor.

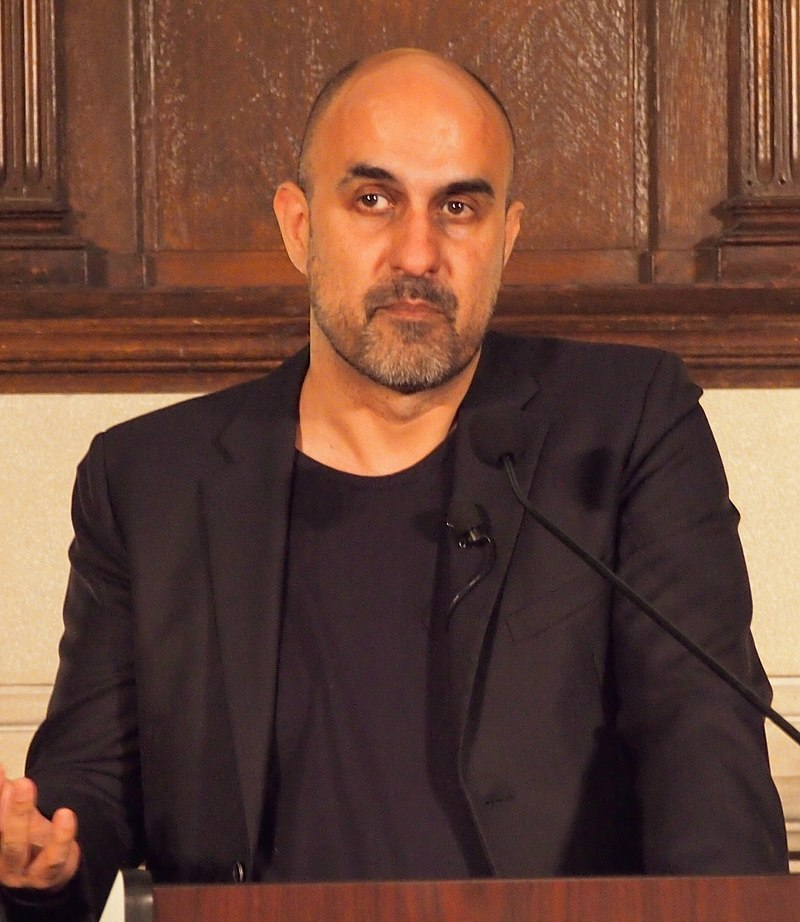

Above: American comedian Groucho Marx (1890 – 1977)

Zealots rarely laugh.

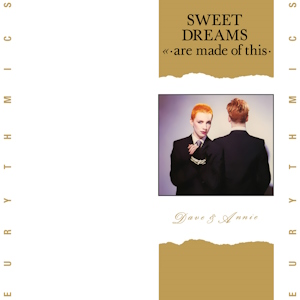

Well I was born an original sinner.

I was borne from original sin.

And if I had a dollar bill

For all the things I’ve done

There’d be a mountain of money

Piled up to my chin

My mother told me good

My mother told me strong.

She said “Be true to yourself

And you can’t go wrong.”

“But there’s just one thing

That you must understand.”

“You can fool with your brother

But don’t mess with a missionary man.“

Don’t mess with a missionary man.

Don’t mess with a missionary man.

Well the missionary man

He’s got God on his side.

He’s got the saints and apostles

Backin’ up from behind.

Black eyed looks from those Bible books.

He’s a man with a mission

Got a serious mind.

There was a woman in the jungle

And a monkey on a tree.

The missionary man he was followin’ me.

He said “Stop what you’re doing.”

“Get down upon your knees.”

“I’ve a message for you that you better believe.“

I work on my blog – easier than the slog of book-writing.

I had intended to visit Joan Miro exhibition in Rorschach’s Fondation Würth Museum.

This idea is squashed.

No museums unless accompanied by a spouse.

Above: Rorschach, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

I had considered a walking day:

Train to Frauenfeld, bus to Oberneunforn, walk 14.3 km back to Frauenfeld via Uesslingen, Buch and Ittingen.

Above: Frauenfeld, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Gemeindehaus (Municipal Hall), Oberneunforn, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Uesslingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Buch, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Kartause (Charterhouse) Ittingen, Warth, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Thurgauer Rebenweg (Wine Way) – Wanderroute (Walking trail) 910

Man-cold keeps me housebound.

I return to my blog.

I consult my journal which I had the forethought to bring from Eskişehir.

Wednesday 19 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Conversation online with student friend.

Discussion about my dismissal.

I should try private schools, he says.

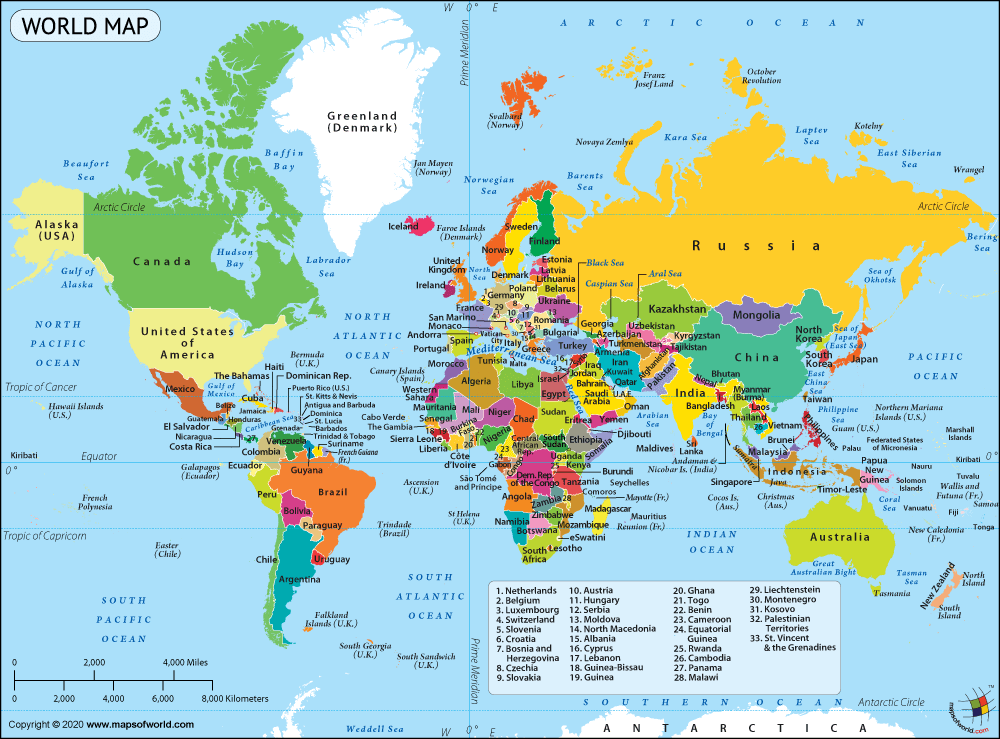

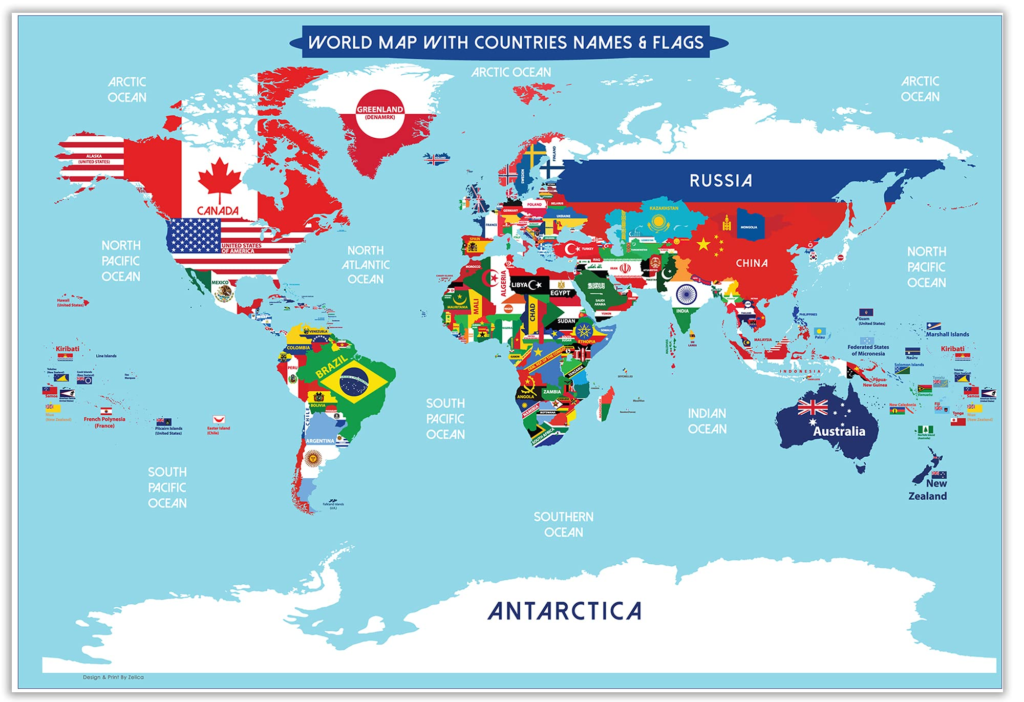

Think beyond Eskişehir – Istanbul and Izmir, Ankara and Antalya, Konya and Kastamonu.

Above: Bridge over Porsuk River in Eskişehir, Turkey

Above: Istanbul, Turkey

Above: Izmir, Turkey

Above: Ankara, Turkey

Above: Antalya, Turkey

Above: Konya, Turkey

Above: Kastamonu, Turkey

There is more in Heaven and Earth than is dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio.

I mention Baku.

Above: Baku, Azerbaijan

He counters with the observation that:

If Azerbaijan is so wonderful, then why did your Azerbaijani friend leave?

Above: Flag of Azerbaijan

I respond with:

If Canada is so wonderful, why did I leave Canada?

Answer:

Sometimes you need to leave the forest to truly see the beauty of it.

Above: Flag of Canada

I focus on my reading.

On 19 February, the world welcomed several writers who, in their own ways, reshaped literature, bending reality to their vision.

Their works remind us that storytelling is not merely about chronicling events but about preserving and reinterpreting human experience.

Of the past, what should be preserved?

Of the past, what interpretation of human experience can be gleaned?

Above: The Thinker, Auguste Rodin (1904), Paris, France

Count Froben Christoph of Zimmern (19 February 1519 – 27 November 1566) was the author of the Zimmern Chronicle and a member of the von Zimmern family of Swabian nobility.

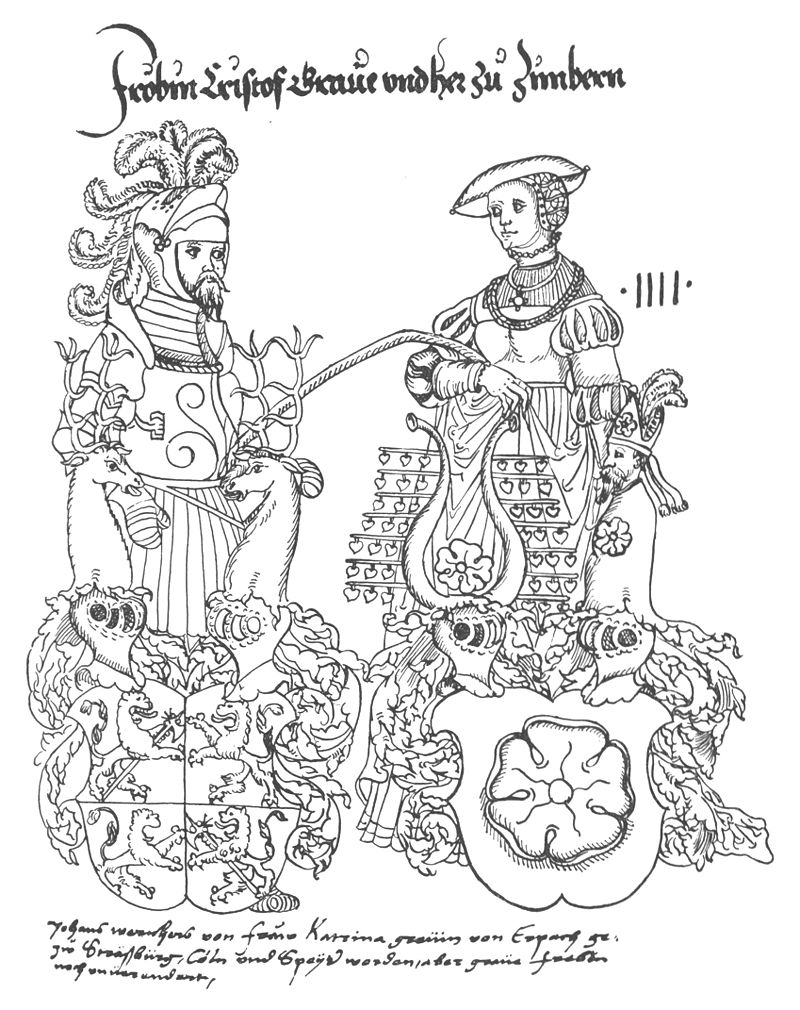

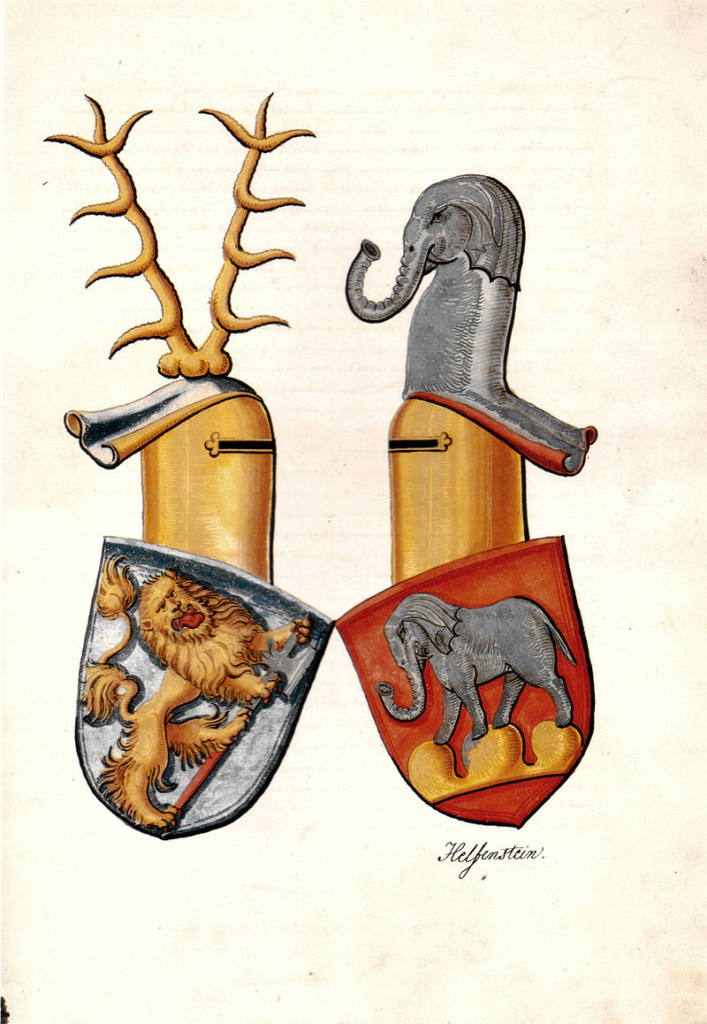

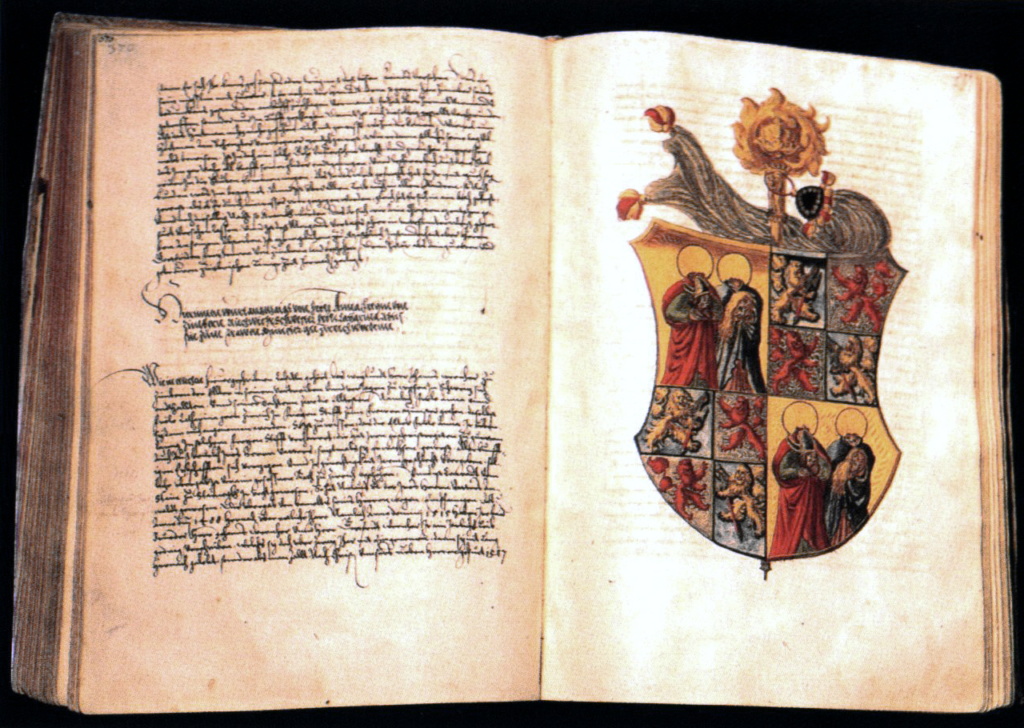

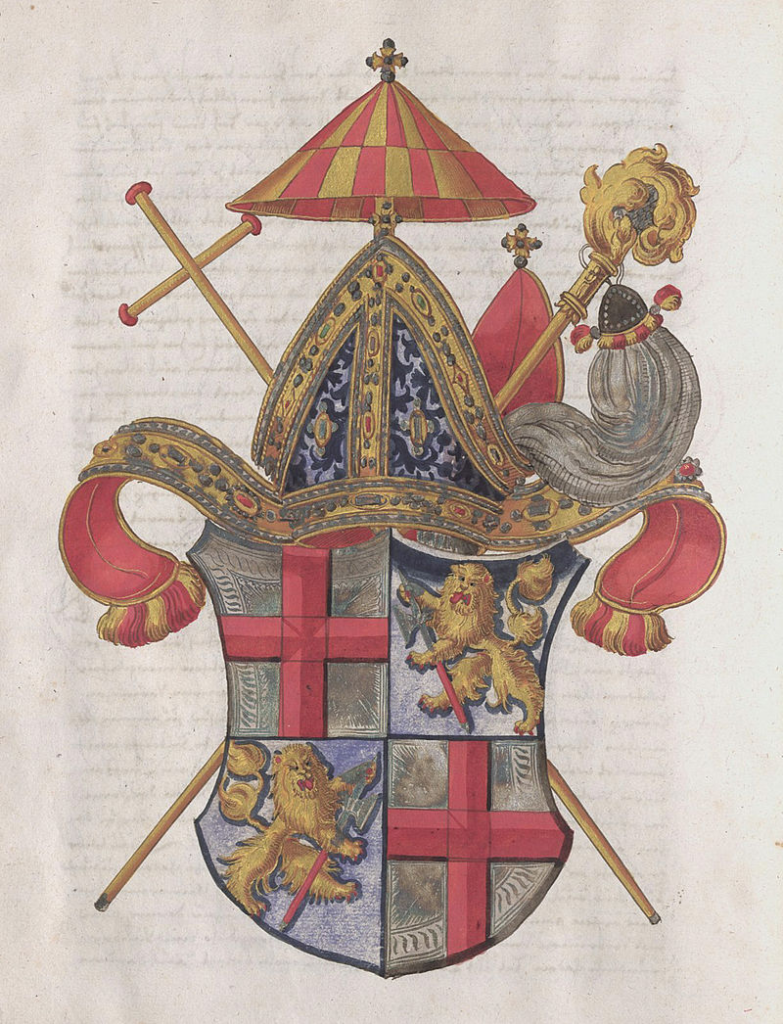

Above: Froben and his wife Kunigunde with their heraldic achievements

Froben Christoph was born at Mespelbrunn Castle in the Spessart as the son of Johann Werner and his wife Katharina of Erbach.

Above: The Mespelbrunn Castle, a moated castle on the territory of the town of Mespelbrunn, is situated remotely in the Elsava valley in the Spessart (between Frankfurt and Würzburg), Bayern (Bavaria), Deutschland (Germany).

Since the early 15th century it has been owned by the family Echter of Mespelbrunn.

The oldest parts were built in 1427, the current appearance was created from 1551 to 1569.

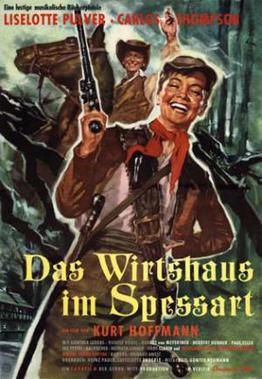

The castle was location of the 1958 German comedy film The Spessart Inn with the the famous German cinema actress Liselotte Pulver.

Consequently it gained nationwide popularity.

It is one of the most visited moated castles in Germany and is frequently featured in tourist books.

The annual numbers of visitors are just under 100,000.

Above: Poster from Das Wirtshaus im Spessart (1958)

He was raised there and in Aschaffenburg by his step-grandfather Philipp Echter and his grandmother, the Countess of Werdenberg.

Above: Aschaffenburg Castle, Bavaria, Germany

He did not visit Meßkirch (Zimmern) until 1531.

Above: Messkirch, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

During a short stay at Falkenstein Castle, he had a conflict-charged meeting with his father.

Above: Falkenstein Castle, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

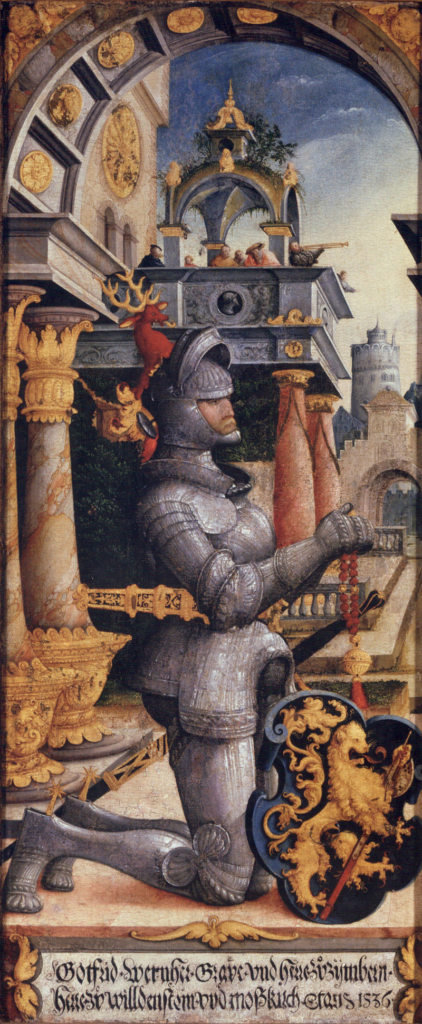

After that meeting, he moved in with his uncle Gottfried Werner in Meßkirch.

It is remarkable that Froben had virtually no contact with his father during the first 23 years of his life.

He didn’t see his father at all during the first twelve years.

He met his father only four times in the next 11, for a total time of significantly less than twelve months.

Their dislike was mutual.

It is therefore not surprising that Froben spent the years until he’d inherit the county in Meßkirch with his uncle Gottfried Werner, rather than at Falkenstein Castle with his father.

Gottfried may have seen Froben as the son he didn’t have himself, or at least as a guarantee for the continued existence of the von Zimmerns.

In any case, he took care of Froben’s education.

The next twelve years were hard, as Werner Gottfried kept his protégé on a very short leash.

Nevertheless, the Zimmern Chronicles suggests a cordial relationship still existed between them.

He fulfilled social obligations for his uncle, and after his father’s death in January 1548, also for his own properties.

Above: Messkirch Castle, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

In 1533, Froben Christoph and his elder brother Johann began studying at the University of Tübingen.

Above: Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

After a stay in Strasbourg, he studied from early 1534 to 1535 in Bourges.

Above: Strasbourg, Alsace, France

Above: Bourges, Cher Department, France

During the winter of 1536 – 1537, he studied in Köln, and from Easter 1537, without his brother, in Leuven, where he remained until July 1539.

Above: Köln (Cologne), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Above: Leuven, Brabant Province, Belgium

After a short stay at home, he travelled to Leuven in November 1539, intending to continue his studies in Spain.

He then changed his plans and in December 1539, he travelled via Paris to Angers.

Above: Images of Angers, Maine et Loire Department, France

On 23 February 1540 in Paris, he completed his first historical work, the liber rerum Cimbriacarum, which is virtually a first (short) version of his Zimmern Chronicle.

Above: Paris, France

Shortly after Easter 1540, Froben traveled to Angers, together with his younger brother Gottfried, whom he had met in Paris.

In the winter of 1540 – 1541, they continued their studies in Tours, as the cost of living in Angers had become too high.

Froben became very ill during that period.

This may have been a case of smallpox, or the effect of one of his alchemical experiments.

Above: Plumereau Square, Tours, Indre et Loire Department, France

After his recovery, he made a hasty return to Meßkirch, because he, because he feared for his life, due to a feud against his family.

He reached Meßkirch at the end of July 1541.

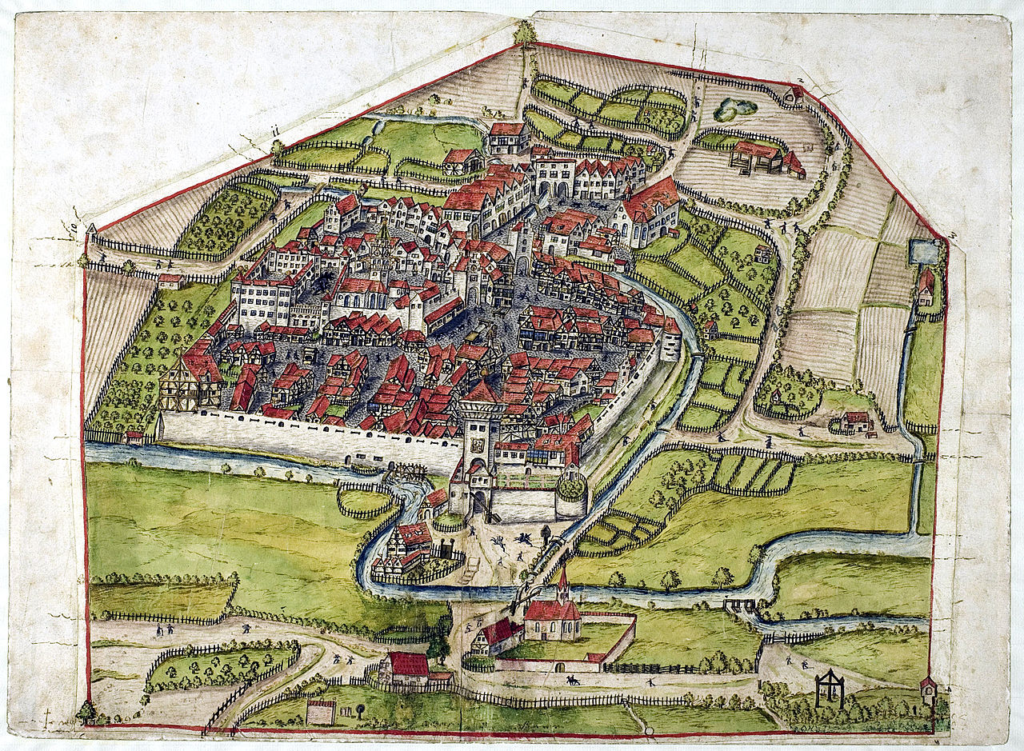

Above: Bird’s eye view of Meßkirch in 1575

His fears proved unfounded, so he continued his studies in the fall in Speyer.

In Speyer, he lived in the house of his uncle Wilhelm Werner, who was at that time assessor at the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court) and would be promoted to a full judge in 1548.

In July 1542, Wilhelm Werner temporarily suspended his work for the Reichskammergericht – one of the two highest judicial institutions in the Holy Roman Empire, the other one being the Aulic Council in Wien (Vienna).

Froben Christoph finished his studies.

Above: Speyer, Rheinland-Palatinate, Germany

In 1544, Froben married Kunigunde, a daughter of Wilhelm IV of Eberstein.

Above: Tombstone of Wilhelm IV of Eberstein (1497 – 1562) and Johanna of Hanau-Lichtenberg (1507 – 1572), Gernsbach, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

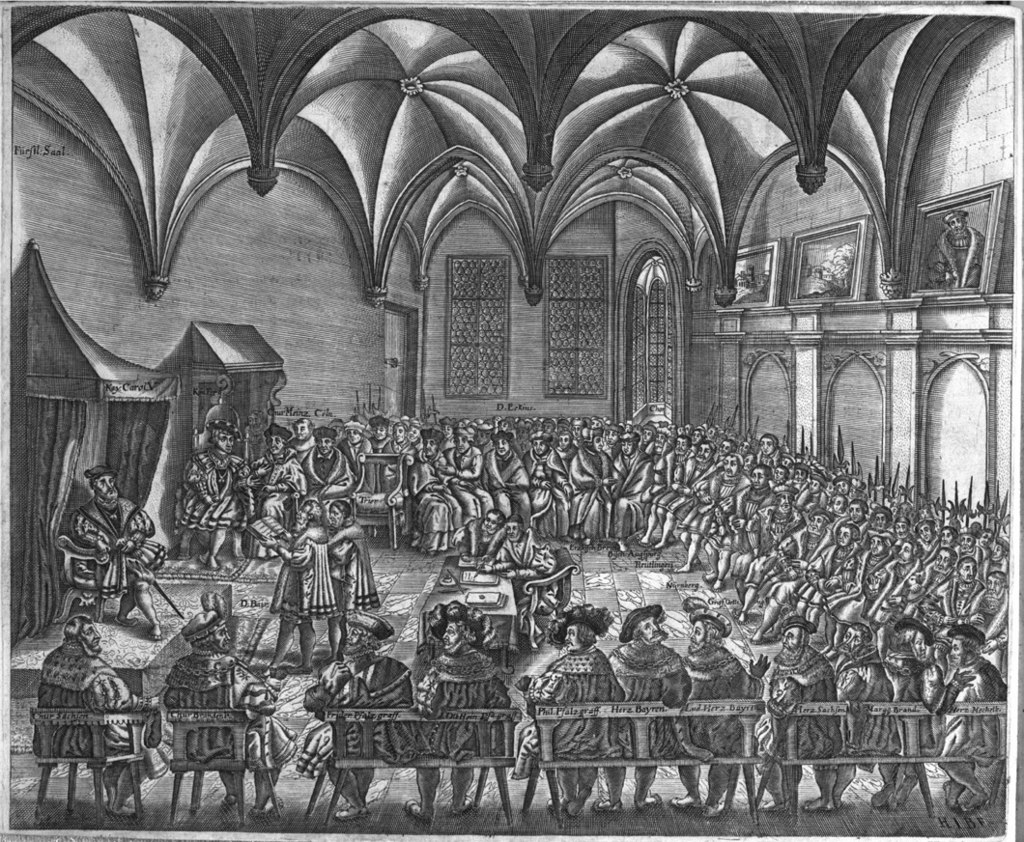

Three years later, in 1547, he took part in the Diet of Augsburg.

Above: Saxon Chancellor Christian Beyer (1482 – 1535) proclaiming the Augsburg Confession (the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Reformation) in the presence of Emperor Charles V (1500 – 1558) – 25 June 1530.

After his father died in 1548, he took care to secure his inheritance.

This included paying his father’s mistress and securing his brother’s renunciation of his rights to inherit.

In June 1549, he traveled to Innsbruck, to receive confirmation of a fief in Austria.

Above: Innsbruck, Tirol (Tyrol), Österreich (Austria)

His only son, Wilhelm, was born on 17 June 1549.

This proved to be a trigger to initiate construction projects, like his uncle Gottfried Werner had done.

In 1550, he started construction of a new suburb of Meßkirch.

On 9 March 1554, his uncle suffered his first stroke.

His uncle then handed the keys and title to all his worldly possessions to Froben, in the presence of witnesses.

After Gottfried Werner died on 12 April 1554, Froben immediately asked his subjects to swear an oath of fealty to him.

He also quickly invited his brothers to renew the renunciation of their right to inherit.

When his brother-in-law Philipp of Eberstein married Countess Joanna of Donliers in St. Omer in 1556, Froben and his relatives used the occasion to organize a journey to Flanders via Zweibrücken, Trier, Liège, Tongeren, Leuven and Brussels.

Above: Cathedral, St. Omer, Pas de Calais Department, France

Above: Zweibrücken, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Above: Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Above: Liège, Belgium

Above: Grote Markt, Tongeren, Limburg Province, Belgium

Above: Grand Place, Brussels, Belgium

On 9 May 1557, he laid the foundation stone for the reconstruction of the castle in Meßkirch.

It would be the first four-winged, Italian style castle in southern Germany.

Above: Messkirch Castle

In the spring of 1558, he added an orchard modeled after one at the court in Heidelberg.

Above: Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

On 8 October 1558, his 7th child was born.

This was the last entry in the Zimmern Chronicles (apart from the supplements).

In 1559, he retired from all public duties.

However, he did attend the Diet in Augsburg.

Above: Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany

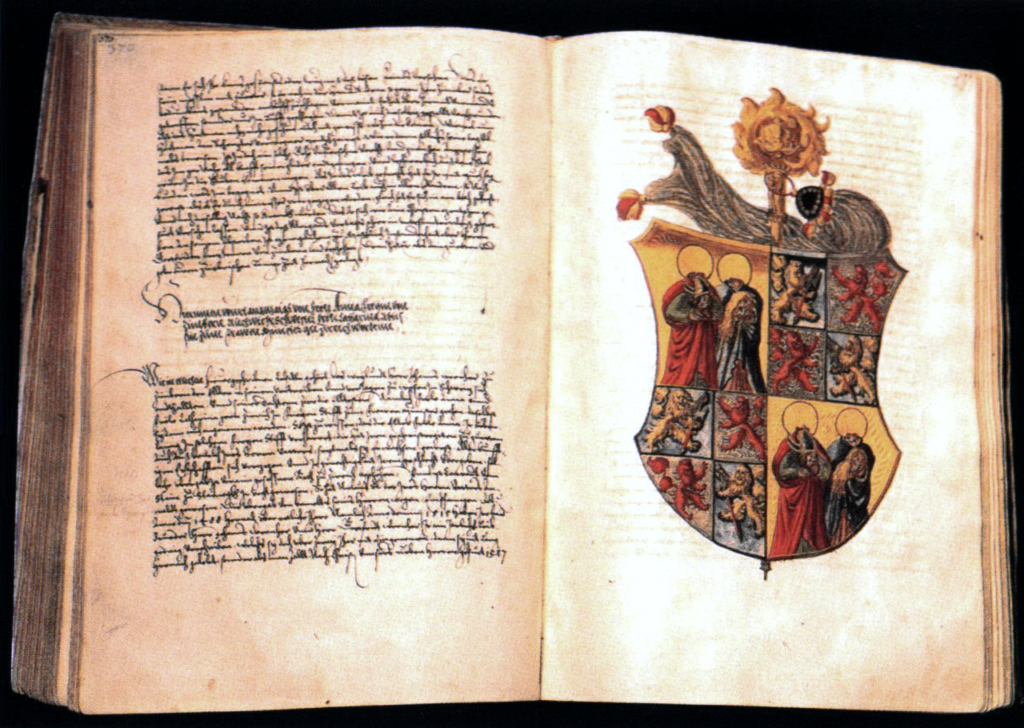

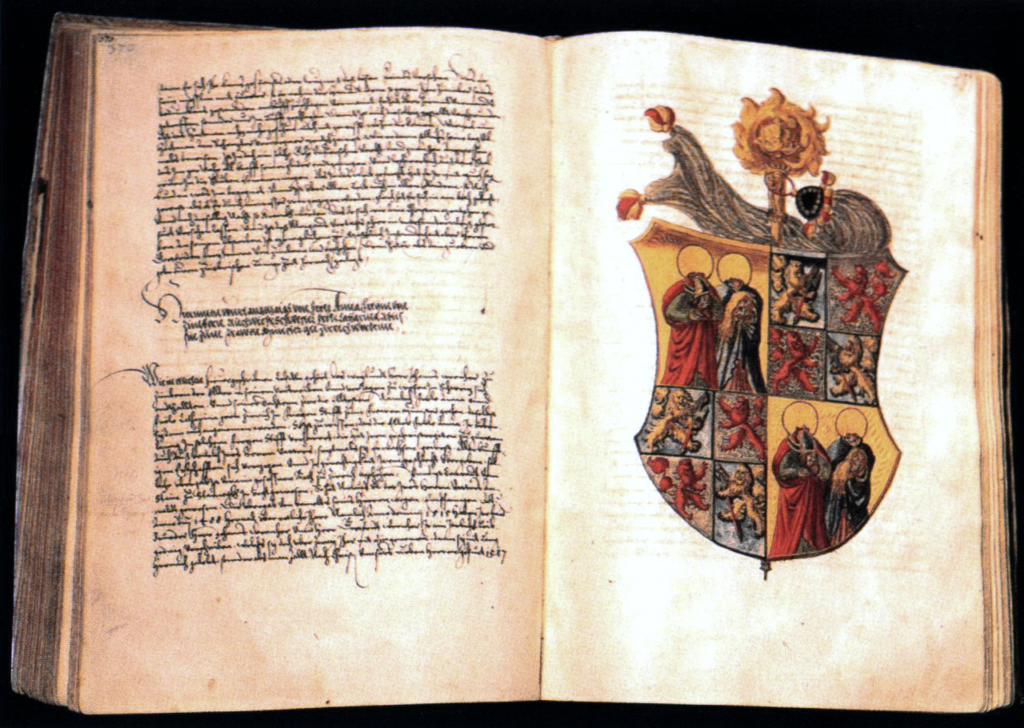

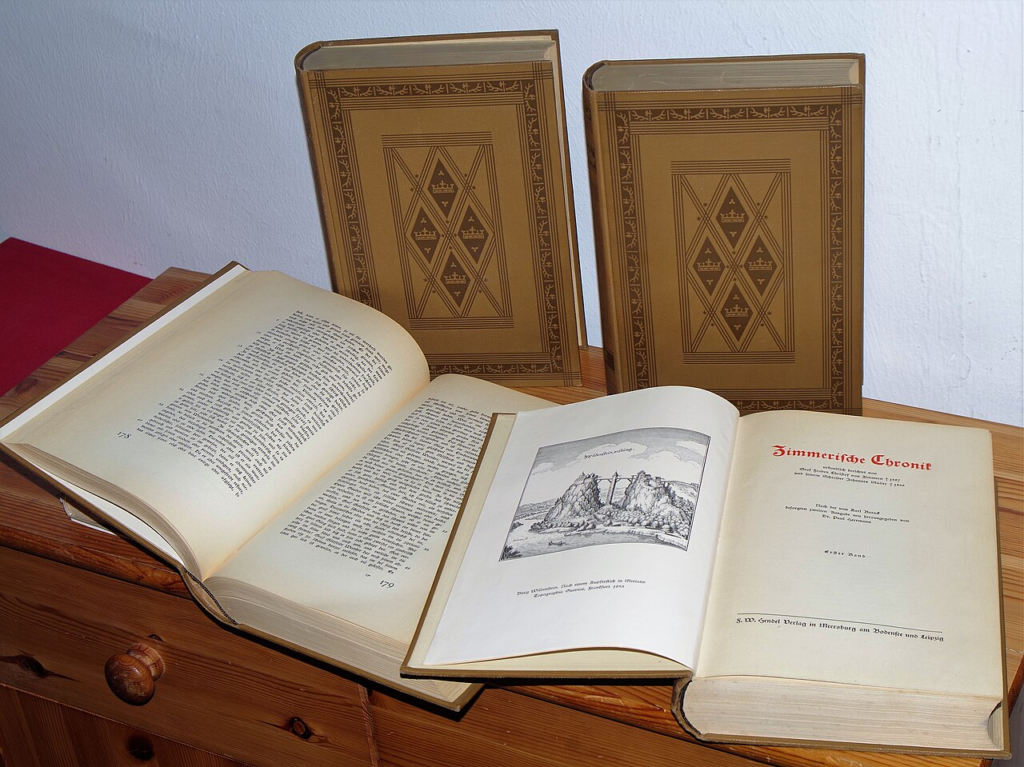

Manuscript A of the Zimmern Chronicles most likely originated around this time.

Manuscript B was drafted from 1565.

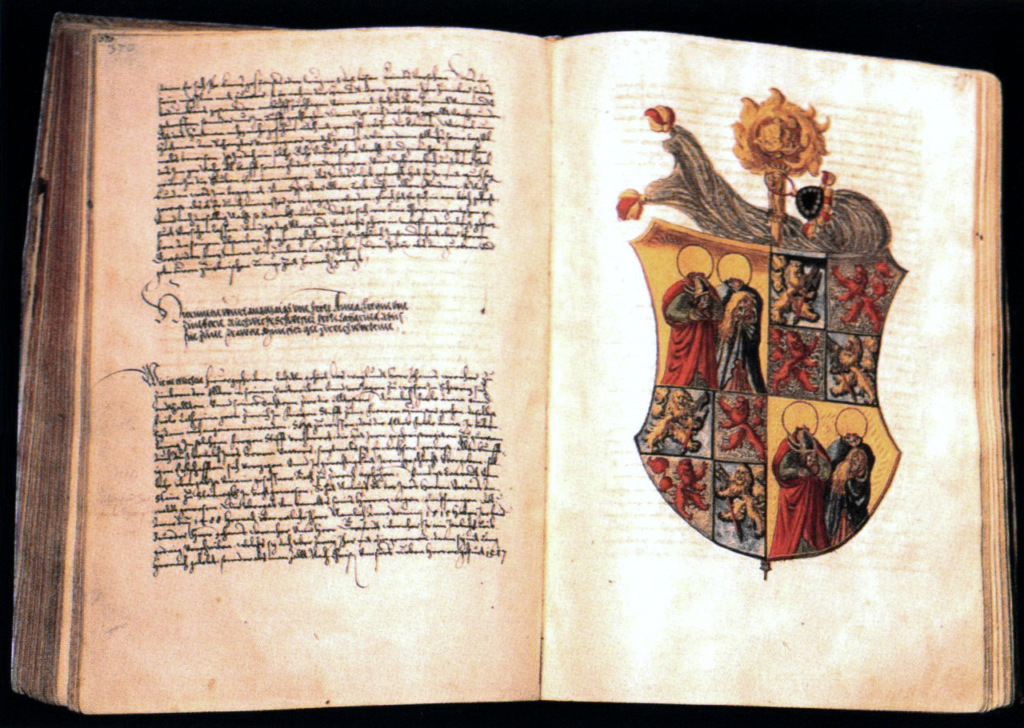

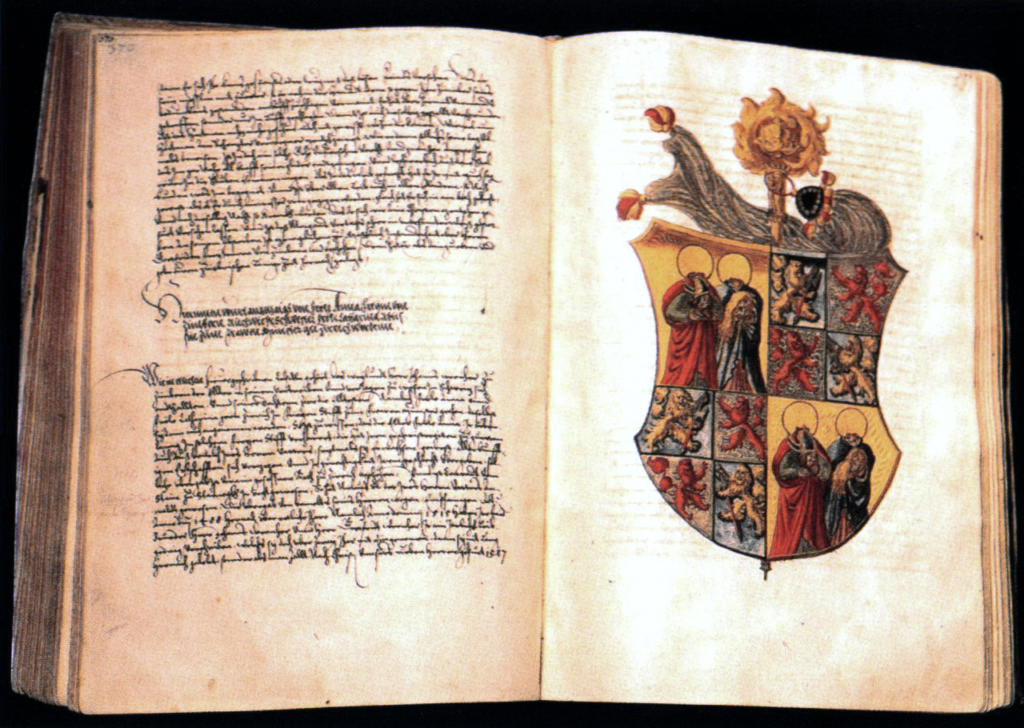

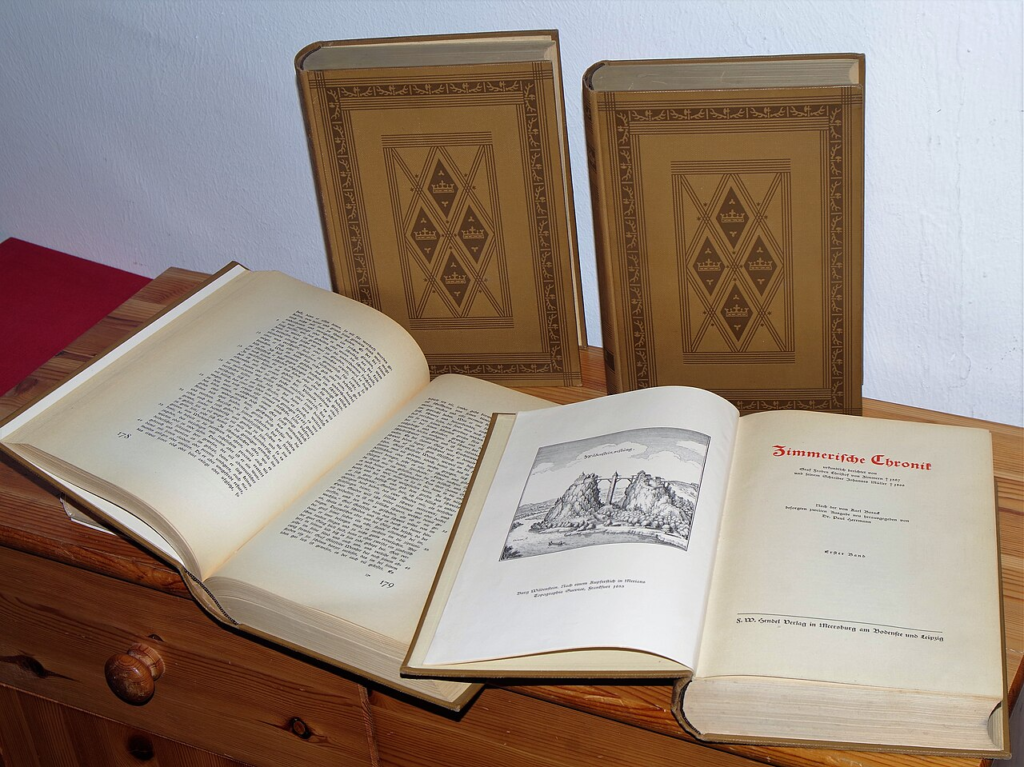

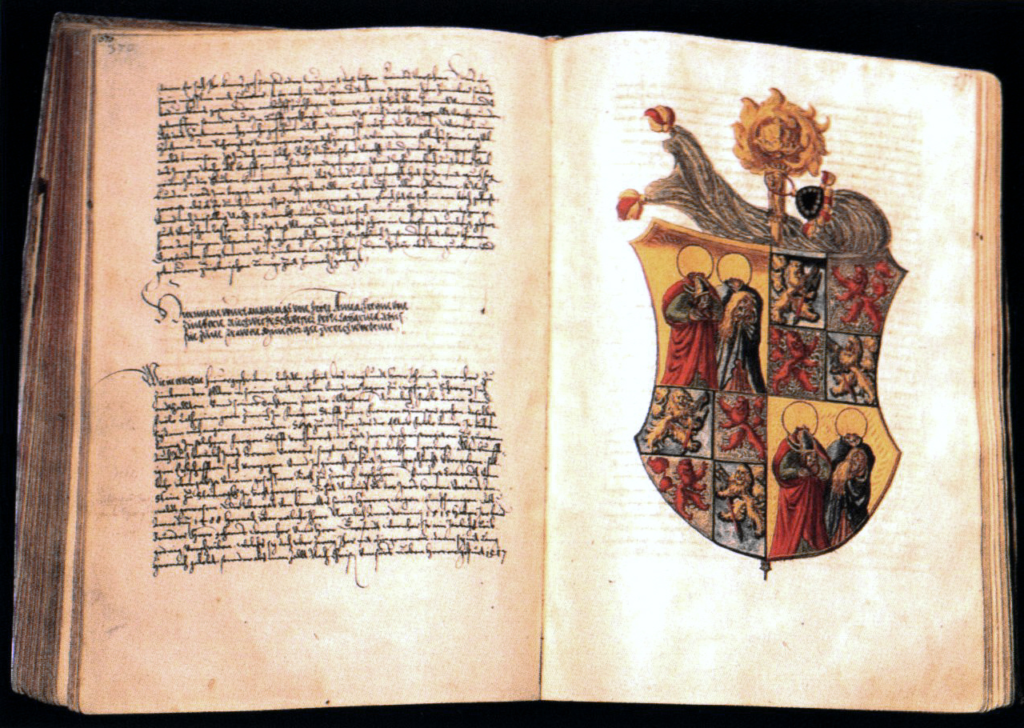

Above: Zimmern Chronicle (Manuscript B)

In the winter of 1565 – 1566, he probably made a journey to Italy, which had been a long cherished dream from his youth.

He had wanted to study in Bologna, but his father had not allowed this.

Above: Map of Bologna, Italia (Italy) (1640)

Notes from the Chronicle mention visits to Venice and Rome.

Above: Grand Canal, Venezia (Venice), Italy

Above: Roma (Rome), Italia

He died on 27 November 1566, probably in Meßkirch.

Above: Messkirch

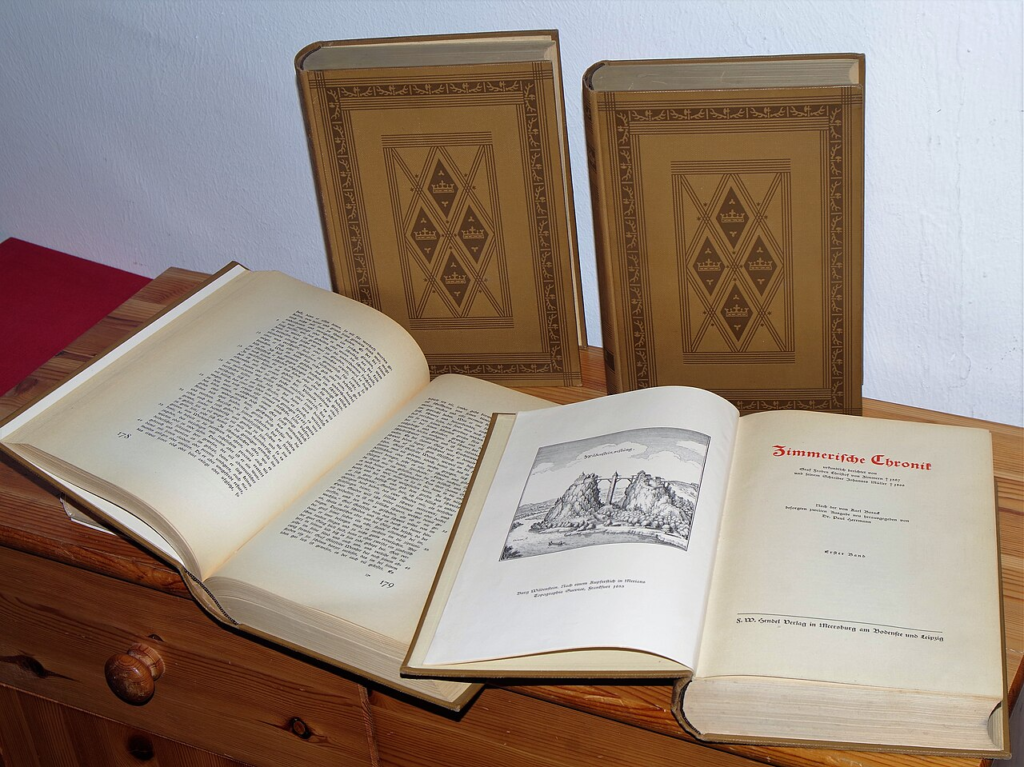

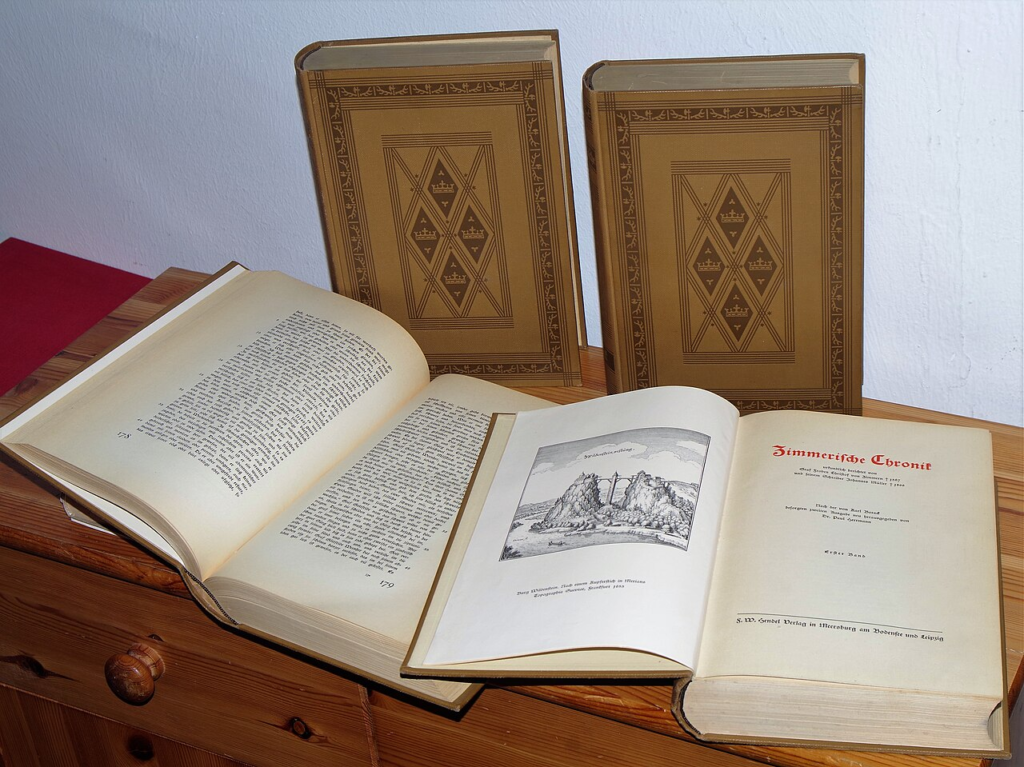

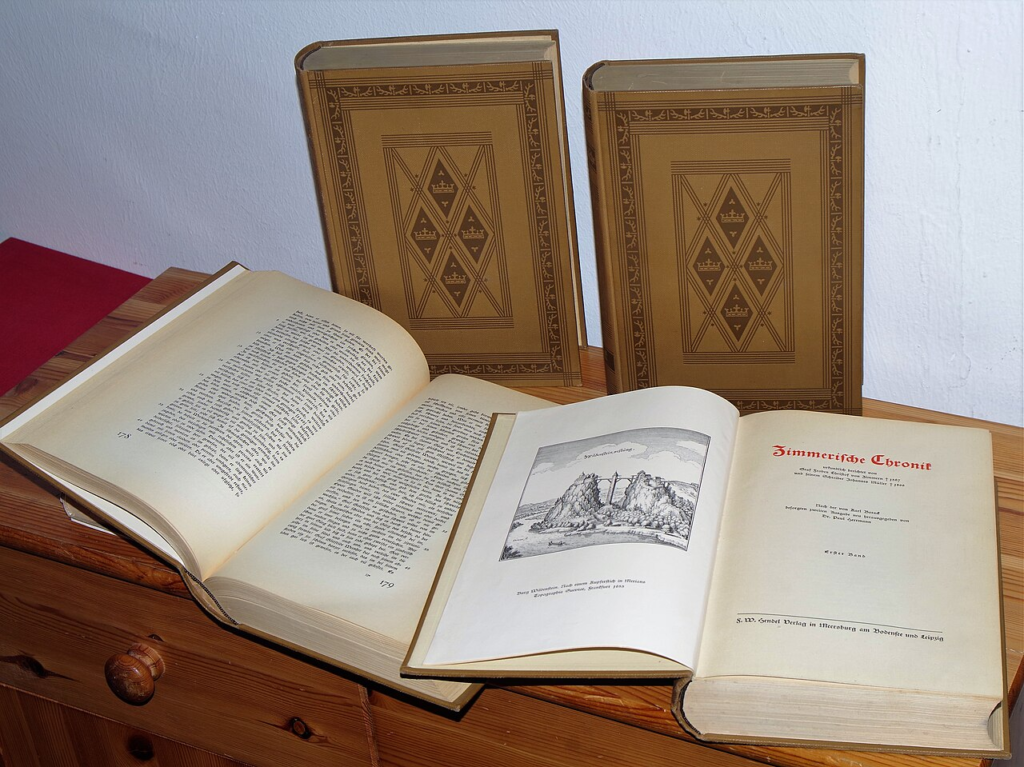

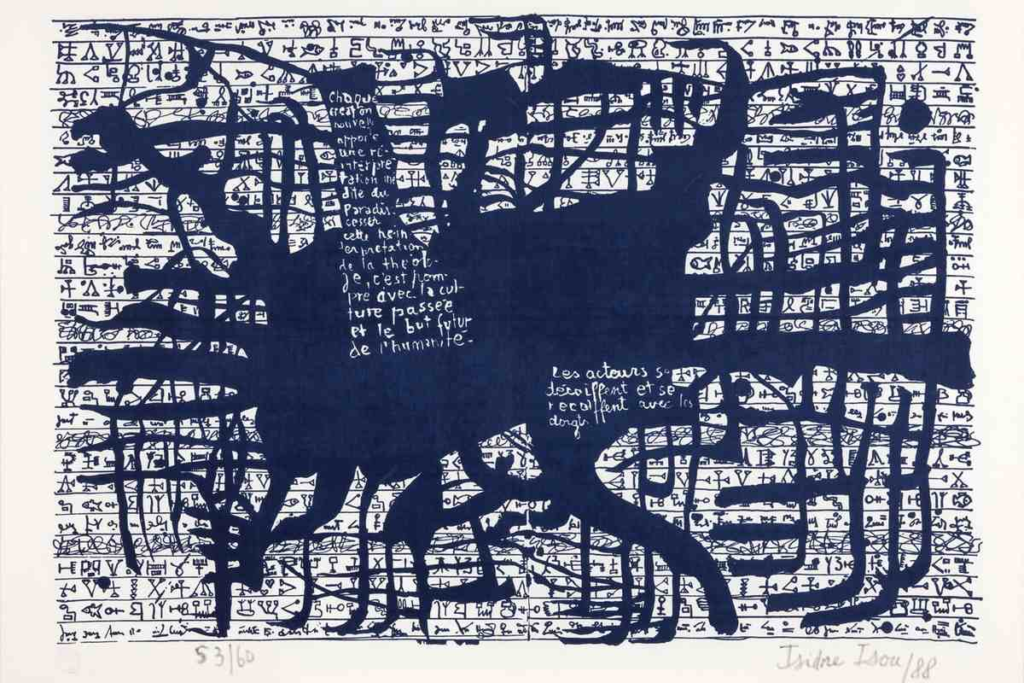

The Zimmern Chronicle (German: Zimmerische Chronik or Chronik der Grafen von Zimmern) is a family chronicle describing the lineage and history of the noble family of Zimmern, based in Meßkirch, Germany.

It was written in a Swabian variety of Early New High German by Count Froben Christoph of Zimmern (1519 – 1566).

The Chronicle is an eminent historical source of information about 16th century nobility in Southwest Germany, its culture and its values.

It is also an important literary and ethnological source for its many folkloristic texts.

The text has survived in two manuscripts, both in possession of the Württembergische Landesbibliothek (Württemberg State Library) in Stuttgart.

Above: Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart, Germany

When the anonymous, unpublished chronicle was rediscovered in the 19th century, historians were not sure about the identity of the author.

(Most of the Chronicle is written in the third person, while at some times the writer slips into the first person.)

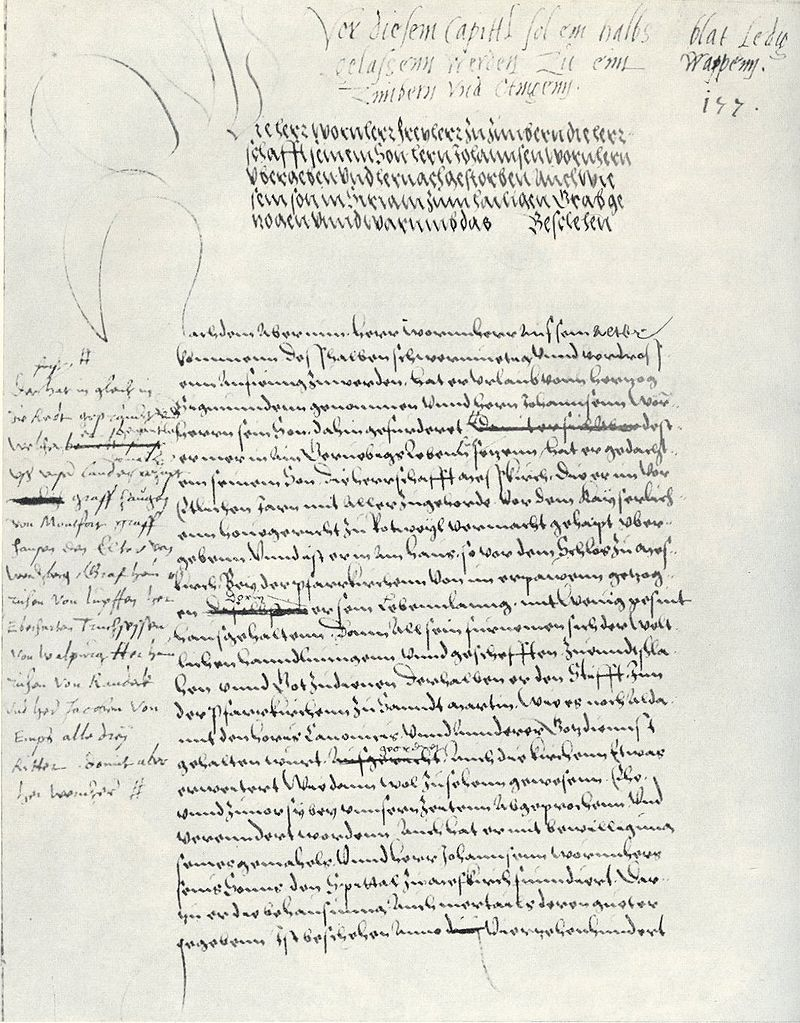

Above: Zimmern Chronicle folio

While some considered the author to be the famous law scholar and Imperial judge, Wilhelm Werner von Zimmern (Froben Christopher’s uncle), others believed Count Froben Christopher and his secretary Johannes Müller (1600) to be the writers.

In 1959, Beat Rudolf Jenny proved in his thoroughly researched book that Froben Christopher is the sole author of the Chronicle.

However, Wilhelm Werner’s influence on his nephew is palpable in some passages.

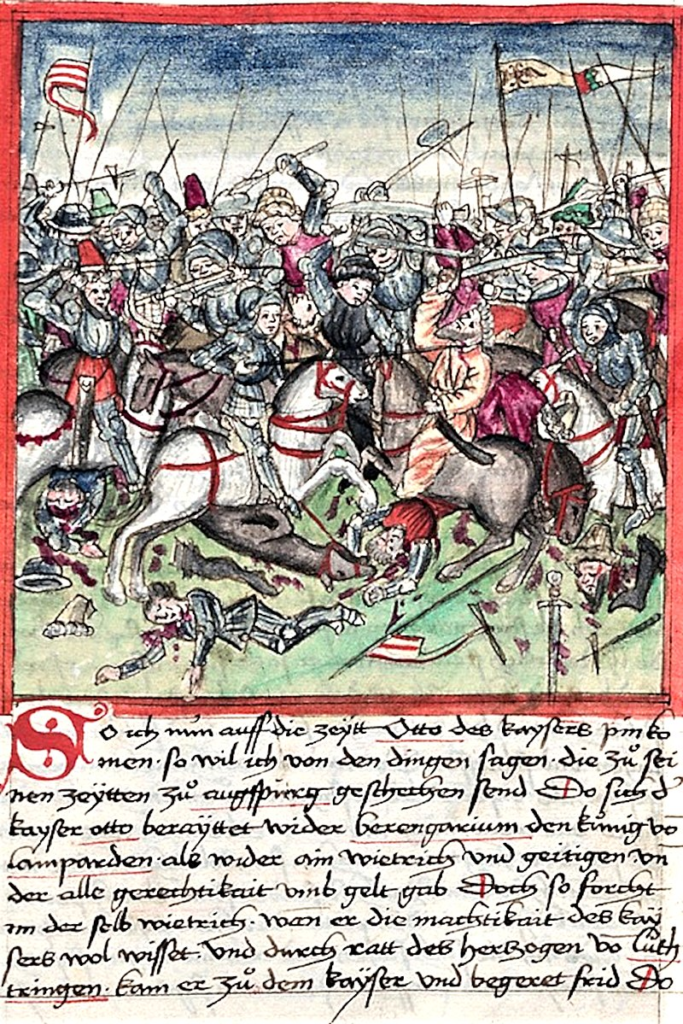

Above: Zimmern Chronicle illustration

Writing or ordering a genealogy was a rather common form of representation for Germany’s noble families of the time.

However, the Zimmern Chronicle surpasses other contemporary texts in both volume and scope.

It is a compilation of many types of texts, including simple genealogical information, psychologically rich biographies of ancestors and members of other noble families, fables, schwanks (droll stories) and facetiae (comic and/or erotic short stories).

The purpose of the work is probably twofold:

Firstly, Froben Christopher wanted to prove the nobility of his family and to preserve that knowledge to posterity.

Secondly, the Chronicle was a means to educate future family members.

The author does not only tell the stories of shining examples of nobility, but he also gives proof of bad examples.

He clearly condemns some of his more spendthrift ancestors for selling family goods and hence giving away economic and political power.

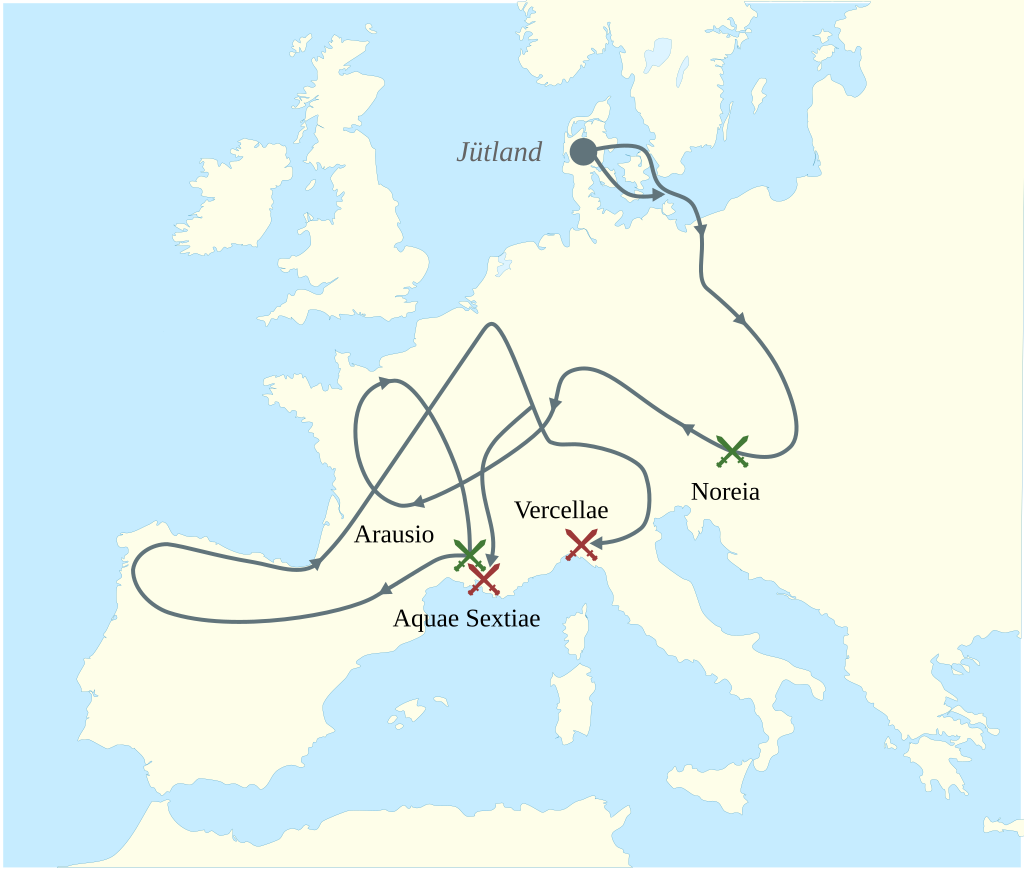

The Zimmern Chronicle begins with the history of the Cimbri, an ancient Germanic tribe, and tells the story of the Cimbri’s forced relocation to the Black Forest (Schwarzwald) under the reign of Charlemagne.

Above: The defeat of the Cimbri

Above: Frankish King Charlemagne (748 – 814)

While the link between the Cimbri and the Zimmern family is fictional and only induced by the similar-sounding name, Froben recounts several episodes woven into a stream of historical information to prove it.

The work also includes a complete fictional genealogy starting in the 10th century.

Historical evidence is entered with the first actually known family member, Konrad von Zimmern, Abbot of Reichenau Abbey from 1234 to 1255.

Above: Reichenau Abbey, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Starting with the early 14th century, the genealogical and historical parts of the Zimmern Chronicle are finally reduced to facts.

Still, Froben inserts entertaining stories to enliven his characterizations and to prove his political points.

The Zimmern Chronicle differs from other contemporary aristocratic and diocesan chronicles (and thus also from the work of Wilhelm Werner von Zimmern) in that it goes beyond genealogical lists of generational successions and presents the people described as psychologically differentiated personalities.

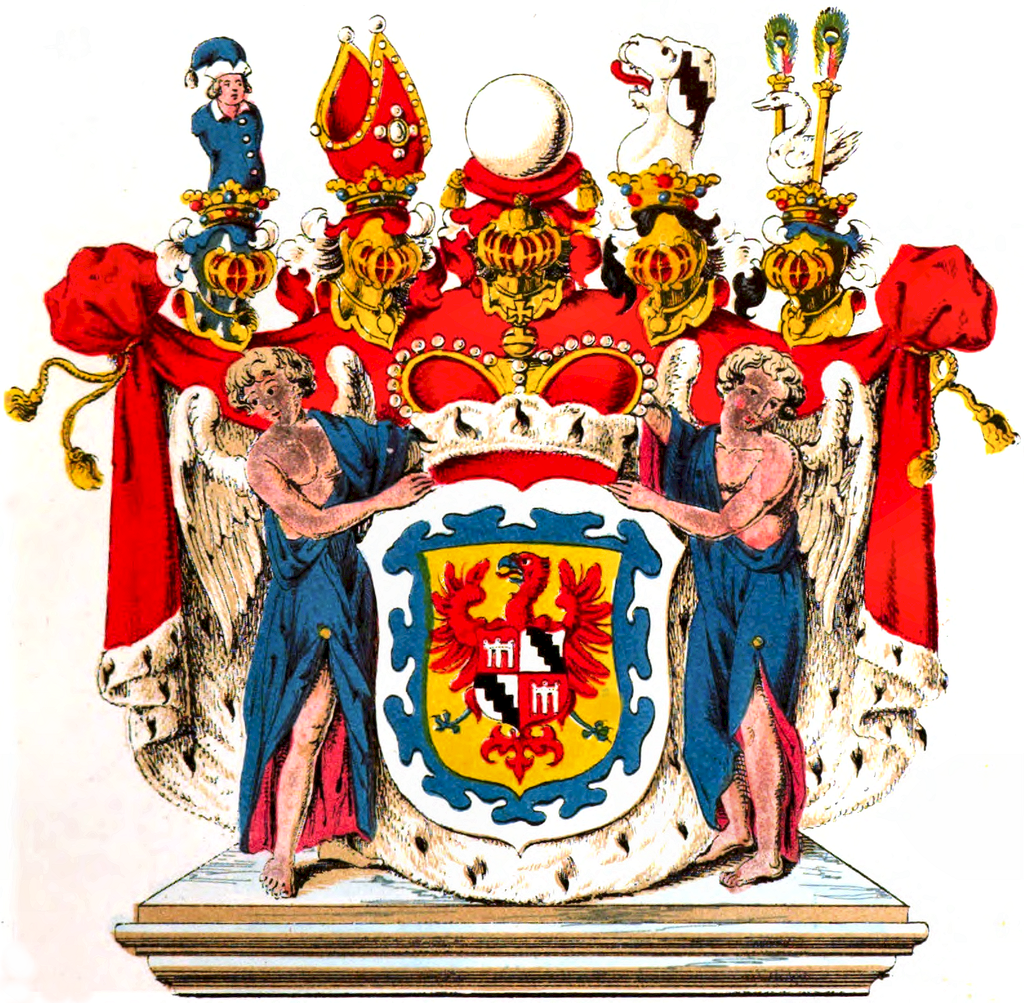

Above: Wilhelm von Zimmern (1549 – 1594)

This is done not only for the Zimmern family members, but also for neighboring noble families:

- Württemberg

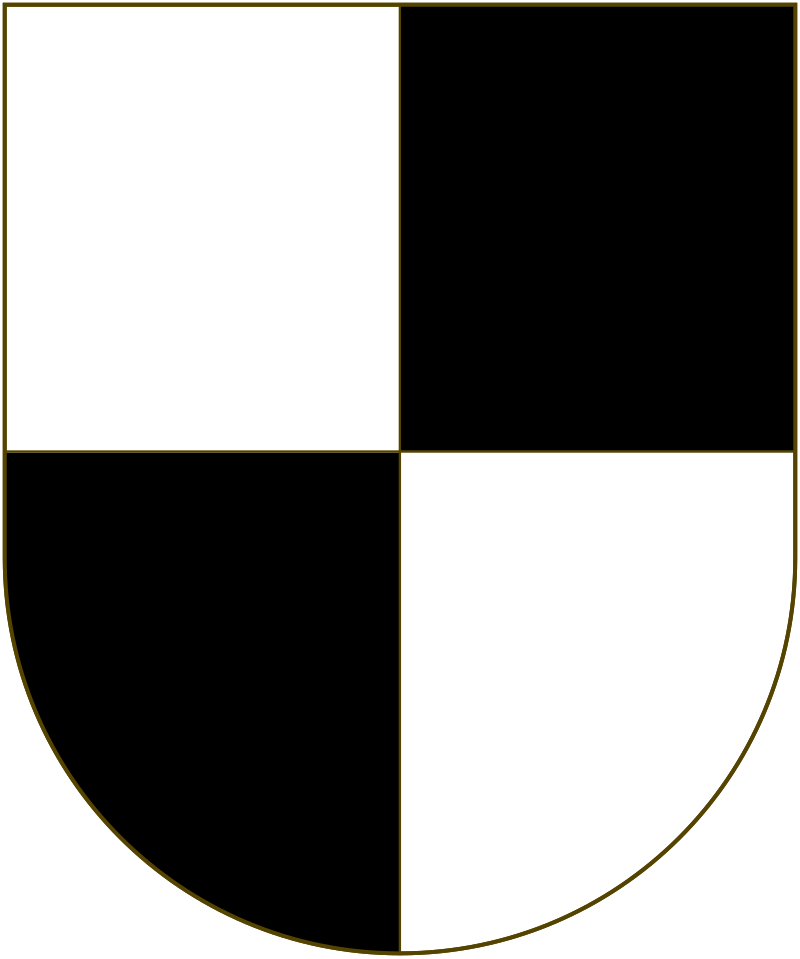

Above: Coat of arms of Württemberg

- Zollern

Above: Coat of arms of Hohenzollern dynasty

- Werdenberg

Above: Werdenberg Castle, Grabs, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

- Waldburg

Above: Coat of arms of Waldburg dynasty

- Fürstenberg

Above: Coat of arms of the Fürstenberg dynasty

Images and fables as well as factions known to the literary-educated contemporary reader are also used for characterization.

Some of the reports therefore take on the character of what we today call urban legends.

The Chronicle is mostly told in the third person, with the first person occasionally creeping in.

Count Froben Christoph von Zimmern has been considered the sole author.

His secretary Johannes (Hans) Müller (d. 1600) was previously considered a co-author, but he probably only worked as a scribe.

It is certainly true that the Chronicle was significantly influenced by Froben Christoph’s uncle, the chamber judge and historian Wilhelm Werner von Zimmern.

However, Froben Christoph’s work is characterized by an independent style and a completely different narrative approach.

A distinction between a scientifically working uncle and an amateur nephew is therefore not tenable.

Froben Christoph wrote the Liber rerum Cimbriacarum as early as 1540.

This can be considered the forerunner of the Zimmer Chronicle.

The original has not survived, but we know of it through two copies.

The content already corresponds to the basic framework of the later Chronicle:

- Cimbrian induction – derivation of Zimmern’s descent from the Cimbrians

Above: Migrations of the Cimbri and Teutons

- Forced relocation of Roman nobles to the Black Forest by Charlemagne, the first rooms

Above: Statue of Charlemagne

- Gap of 120 years

- Invasion of the Huns in 934 : Beginning of the lineage with the victorious hero of a duel with a Hunnic giant (missing in the Chronicle)

Above: Battle of Lechfeld, Bavaria – 10 August 955

- A complete list of the names of the family tree (husband, wife, children)

- 1104: Legend of the Deer Miracle on the Stromberg

Above: Stromberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- The historical news begins with Konrad von Reichenau

Above: Coat of arms of Konrad von Zimmern (died 1255)

- The Rohrdorf Heritage, beginning of the 14th century, is the final departure from inventions.

Above: Ruins of Benzenburg, Rohrdorf, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- The complaint about the accident of the family (Werdenberg feud, ostracism of the grandfather) in 1486, introduces the “present” – The Werdenberg feud was the dispute between the

branch of the Werdenberg family based in Sigmaringen and their immediate neighbors in Meßkirch, the Zimmer family.

Above: Ruins of Herrenzimmern, Oberndorf am Neckar, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- The father, Johannes Werner, is only mentioned by name.

Above: Johann Werner von Zimmern (1480 – 1548)

- Uncle Gottfried Werner is honored with a panegyric (lavish eulogy).

Above: Gottfried Werner von Zimmern (1484 – 1554)

The comments about Wilhelm Werner are the most fruitful.

Froben Christoph thanks him for his advice, support and encouragement.

In contrast to the Liber rerum Cimbriacarum, the Zimmer Chronicle is much more narrative in nature, which is only the case in the Liber rerum in the Cimbrian deduction and in the Stromberg saga.

Froben Christoph uses jokes and entertaining stories very consciously and purposefully.

They serve to characterize the people he describes using literary patterns that were very familiar to readers at the time.

The purpose of the Chronicle was, firstly, to provide future generations with evidence of the family’s origins and property after the house’s rise to the rank of Count.

(Past generations were negligent in preserving documents.

Gottfried Werner still allowed glue to be made from old parchments.)

Secondly, the actions of the Zimmern ancestors were to serve as instructions for future members of the House of Zimmern.

Therefore, the condemnation of wasteful behavior and the sale of Zimmern property on the one hand and the praise of increasing property on the other hand run like a common thread through the Chronicle.

Service for more powerful ruling houses, e.g. Austria or Württemberg, is condemned.

In retrospect, it was usually associated with disadvantages for the House of Zimmern.

Examples from other noble houses are also used solely from this point of view.

Ivan Vanko (Mickey Rourke):

You come from a family of thieves and butchers.

And like all guilty men, you try to rewrite your history.

To forget all the lives that the Stark family has destroyed.

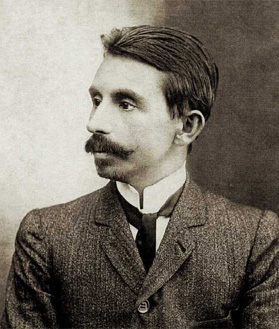

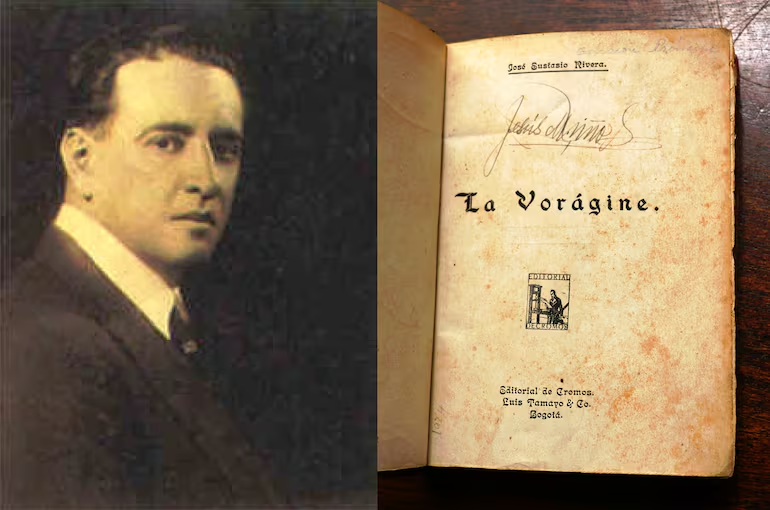

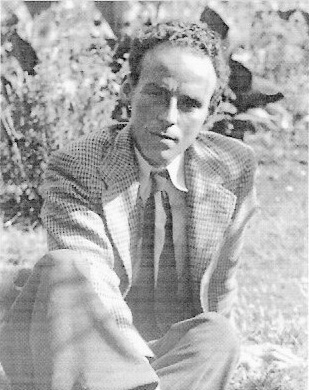

José Eustasio Rivera Salas (February 19, 1888 – December 1, 1928) was a Colombian lawyer and author primarily known for his national epic The Vortex.

Above: José Eustasio Rivera

José Eustasio Rivera was born in Aguas Calientes, a hamlet of the city of Neiva, later that year the hamlet was incorporated into the newly created municipality of San Mateo, which was later renamed Rivera in honor of José Eustasio.

Above: Rivera, Huila Department, Colombia

His parents were Eustasio Rivera Escobar and Catalina Salas.

He was the first boy and fifth child out of eleven children, of whom eight reached adulthood: José Eustasio, Luis Enrique, Margarita, Virginia, Laura, Susana, Julia and Ernestina.

Above: Nevia, Huila Department, Colombia

In spite of his family’s economic situation, he received a Catholic education thanks to the help of other relatives and his own efforts.

He attended Santa Librada school in Neiva and then San Luis Gonzaga in Elías.

Above: Elias, Huila Department, Colombia

In 1906 he received a scholarship to study at the normal school in Bogotá.

Above: Bogotá, Colombia

In 1909, after graduating, he moved to Ibagué where he worked as a school inspector.

Above: Ibagué, Tolima Department, Colombia

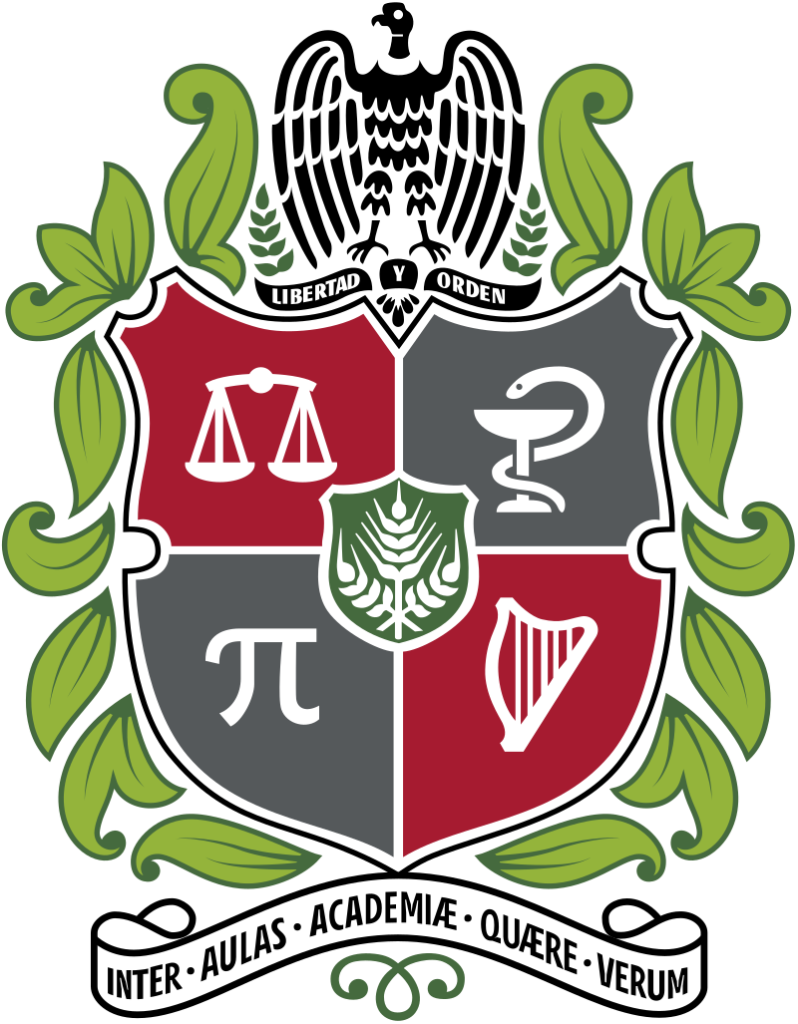

In 1912 he enrolled at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of National University, graduating as a lawyer in 1917.

Above: Coat of arms of the Escudo de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia

After a failed attempt to be elected to the Senate, he was appointed Legal Secretary of the Colombo-Venezuelan Border Commission to determine the limits with Venezuela, there he had the opportunity to travel through the Colombian jungles, rivers, and mountains, giving him a first hand experience of the subjects he would later write.

Disappointed with the lack of resources offered by his government for his trip, he abandoned the Commission and continued travelling on his own.

He later rejoined the Commission, but before that he went to Brazil, where he became acquainted with the work of important Brazilian writers of his time, particularly Euclides da Cunha.

Above: Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha (1866 – 1909)

Euclides da Cunha was a Brazilian journalist, sociologist and engineer.

His most important work is Os Sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands), a non-fictional account of the military expeditions promoted by the Brazilian government against the rebellious village of Canudos, known as the War of Canudos.

Influenced by theories like positivism and social Darwinism from the end of the 19th century, Cunha discussed the forming of a new Brazilian Republic and also its racial composition and its promising future of progress and civilization.

The book is originally divided into three parts:

- 1) “A Terra” (The Land), which portrays the northeastern backland and the physical setting of the war

- 2) “O Homem” (The Man) exposes the land’s inhabitants and their race composition, explaining the individual by its phenotype and emphasizing the opposition between the coast and the backlands men. Here Da Cunha utilizes much of the racial and psychiatric theories then in vogue to explain the backwardness and “objectified insanity” of the sertanejos.

- 3) “A Luta” (The Rebellion), which narrates the conflict between the republican army and the sertanejos who, despite being considered “racially degenerate“, succeed in winning many battles, even though they lost the war.

Throughout the book, Da Cunha seems to have sympathy for the oppressed sertanejos and to doubt the progress and modernity of Republican ideals.

Through their conflict with the Canudos commune, the forces of modernity and progress are revealed to be just as irrational as their supposedly “uncivilized” opponents and the legitimacy of the Republic is shaken at its foundations.

Os Sertões is considered one of the most important Brazilian works from this historical period, an effort to represent the nation as a totality.

Despite its outdated scientific and historical ideas, Da Cunha’s book is a cornerstone of Brazilian literary and political culture.

Mixing science and literature, the author narrates the true story of a war that happened at the end of the 19th century in Canudos, a settlement of Bahia’s Sertão (“backland“), an extremely arid region where, even now, struggles against poverty, drought and political corruption continue.

During the war (1893 – 1897) against the Republican army, the sertanejos (inhabitants of the backlands) were commanded by a messianic leader called Antônio Conselheiro.

Above: The only photograph of Antonio Conselheiro (1830 – 1897), the mystic rebel and spiritual leader of the War of Canudos, taken after his death

This book was a favorite of American poet Robert Lowell, who ranked it above Tolstoy.

Above: American poet Robert Lowell (1917 – 1977)

Above: Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910)

Jorge Luis Borges also commented on it in his short story “Three Versions of Judas“.

Above: Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899 – 1986)

Os Sertões characterized the coast of Brazil as a chain of civilizations while the interior remained more primitive.

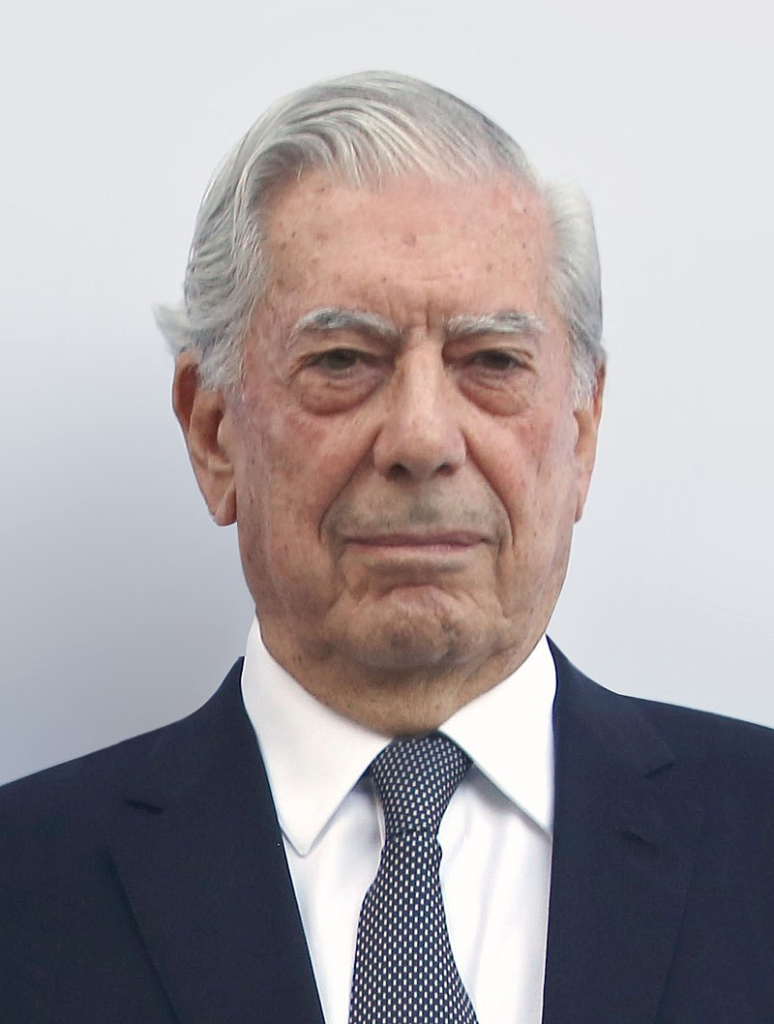

Da Cunha served as inspiration for the character of The Journalist in Mario Vargas Llosa’s The War of the End of the World.

Above: Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa

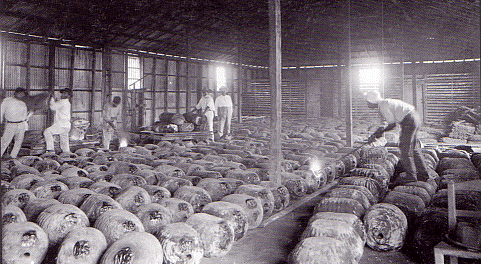

In this venture Rivera became familiar with life in the Colombian plains and with problems related to the extraction of rubber in the Amazon jungle, a matter that would be central in his major work, La vorágine (1924) (translated as The Vortex), now considered one of the most important novels in Latin American literary history.

To write this novel he read extensively about the situation of rubber workers in the Amazon basin.

The Vortex (Spanish: La Vorágine) is a novel written in 1924, set in at least three different bioregions of Colombia during the rubber boom (1879 – 1912).

Above: Rubber bales, ready for removal, Cachuela Esperanza, 1914

This novel narrates the adventures of Arturo Cova, a hot-headed proud chauvinist and his lover Alicia, as they elope from Bogotá, through the eastern plains and later, escaping from criminal misgivings, through the Amazon rainforest of Colombia.

In this way Rivera is able to describe the magic of these regions, with their rich biodiversity, and the lifestyle of the inhabitants.

However, one of the main objectives of the novel is to reveal the appalling conditions that workers in the rubber factories experience.

La Vorágine also introduces the reader to the tremendous hardship of enduring the overwhelming and adverse environment of the rainforest, as the protagonists (Arturo Cova and Alicia) get lost and are unable to be found.

As the book says: ¡Los devoró la selva! (“The jungle devoured them!“).

Above: Amazon Rainforest, Columbia

The novel is written in an elegant and refined prose, full of metaphors and prosaic poetry, that shows the beauty and exoticism of the virgin rainforest.

Above: Amazon Rainforest

The book focuses on two rubber collecting regions, one on the border near Venezuela, during Tomás Funes’ reign of terror.

Above: Amazonas Governor Tomàs Funes (1855 – 1921)

While the second region is in the Putumayo, controlled by Julio César Arana.

Above: Peruvian Senator Julio César Arana del Águila (1864 – 1952)

The author, José Eustasio Rivera, personally visited the region near Venezuela in 1918 as part of a commission.

The novel is divided into six narratives, taking the form of different characters.

Don Clemente Silva’s experience is based on the Putumayo region, while Ramiro Estébanez recalls the crimes of Funes.

La Vorágine is noteworthy as the seminal novel of Latin American regionalism, the “jungle novel“, and recognized as one of the best novels written in Colombia.

After the success of his novel, he was elected, in 1925, as a member for the Investigative Commission for Exterior Relations and Colonization.

He also published several articles in newspapers in Colombia.

In these pieces, he criticized irregularities in government contracts, and denounced the abandonment of the rubber areas of Colombia and the mistreatment of workers.

He also publicly defended his novel, which had been criticized by some Colombian literary critics as being too poetic.

This criticism would be largely silenced by the wide praise the novel was receiving everywhere else.

Above: Flag of Columbia

Rivera had arrived in New York the last week of April 1928 in the hopes of translating his novel into English, publishing it in the US, and turning it into a motion picture film with the goal of exporting Colombian culture abroad.

His venture, although riddled with difficulties, was moving along when, on 27 November, he suffered an attack of seizures.

He was taken to the Stuyvesant Polyclinic Hospital where he remained for four days in a comatose state until his death on 1 December 1928.

Above: Ottendorfer Public Library (left) and Stuyvesant Polyclinic Hospital (right), East Village, Manhattan, New York, USA

After his death, his body was transported by ship from New York to Barranquilla on the United Fruit Company’s ship the Sixaola.

Above: Barranquilla, Atlántico Department, Colombia

Above: Maritime flag of the United Fruit Company (1899 – 1970)

At his arrival on port, his body was transported in procession to the Pro-Cathedral of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino where a requiem mass was given and the body laid in chapelle ardente.

The casket then made its way down the Magdalena onto Bogotá on the mail steamship Carbonell González, arriving in Girardot and finishing by train to arrive in Bogotá on 7 January 1929.

It was taken directly to the Capitolio Nacional, where it was placed lying in state for public viewing.

Above: Congreso Columbia, Bogotá, Columbia

His body was finally laid to rest in the Central Cemetery of Bogotá on 19 January.

Above: Portal of the Central Cemetery, Bogotá, Colombia

Unlike the others on this list, José Rivera remains an enigma, with little known about his life.

Perhaps this is fitting — after all, literature often thrives in ambiguity.

Who he was matters less than what he represents:

The countless forgotten writers who have shaped our world, their words surviving even when their names fade.

Above: José Eustasio Rivera / The Vortex

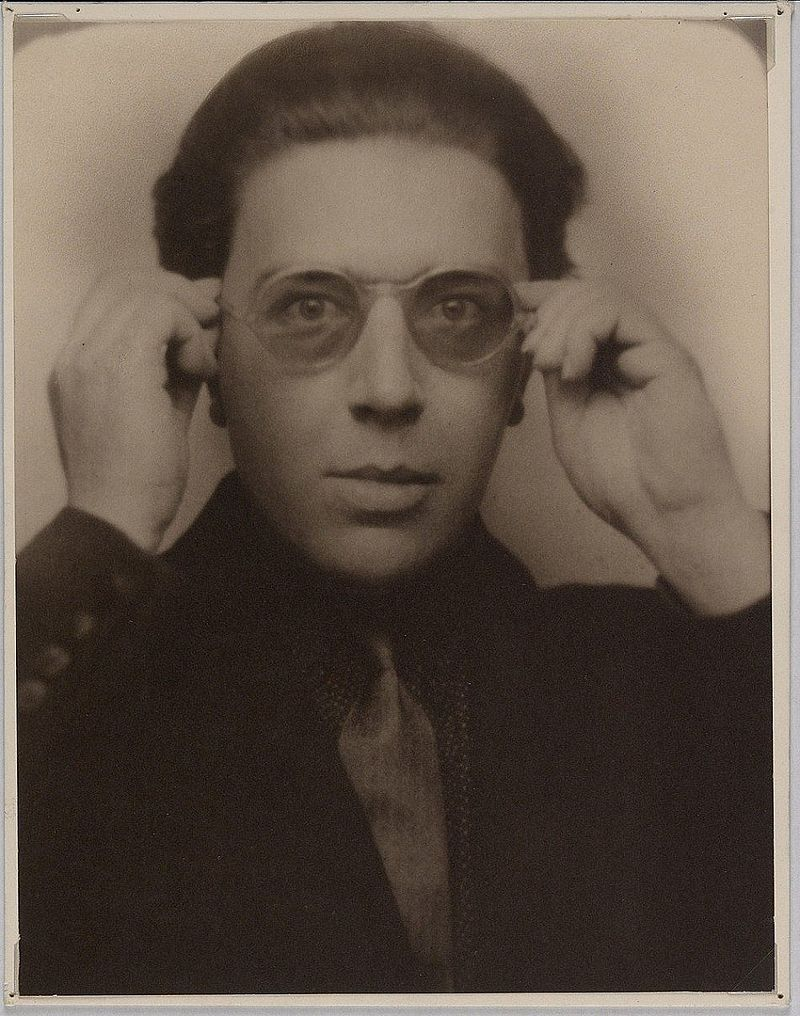

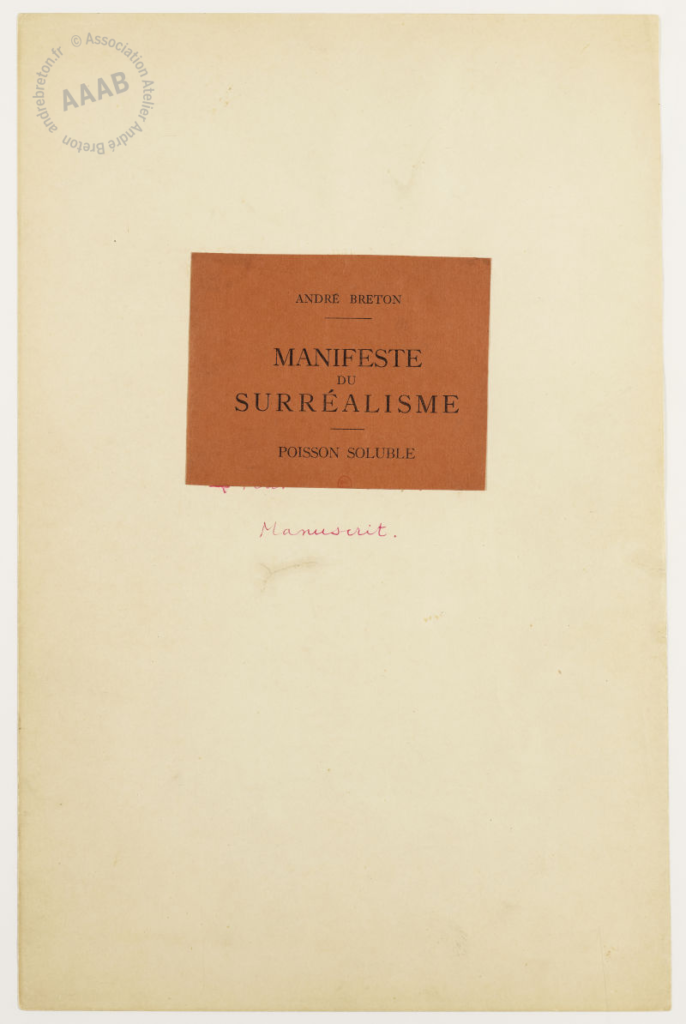

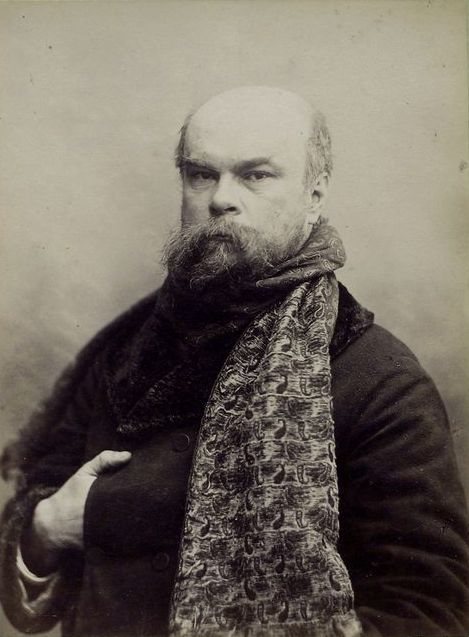

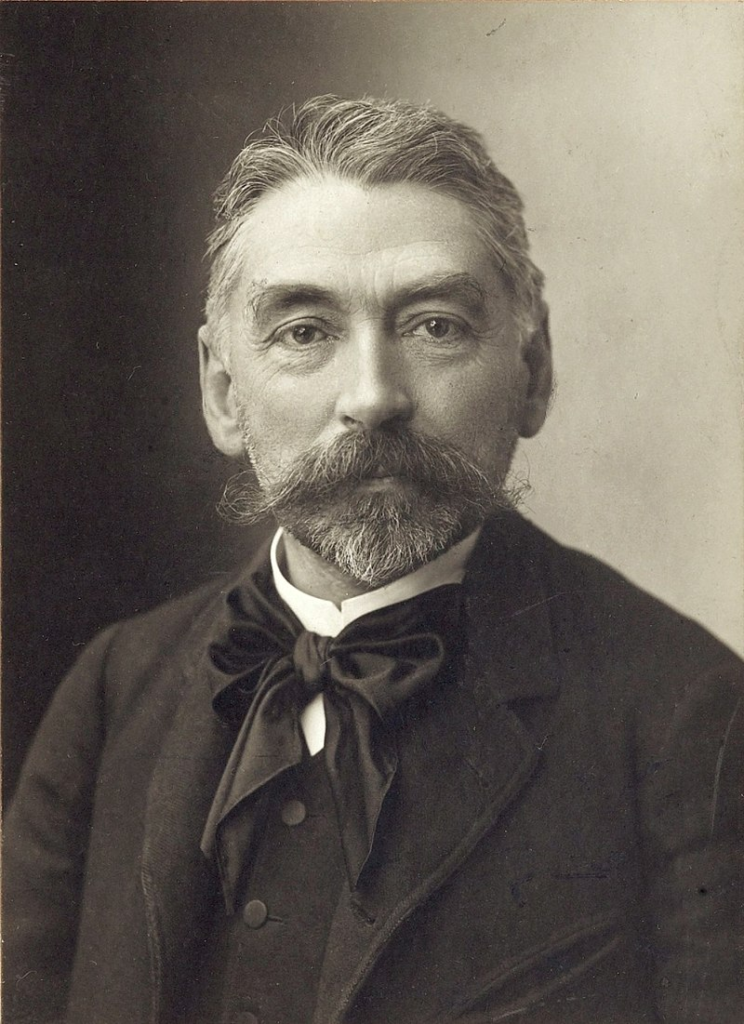

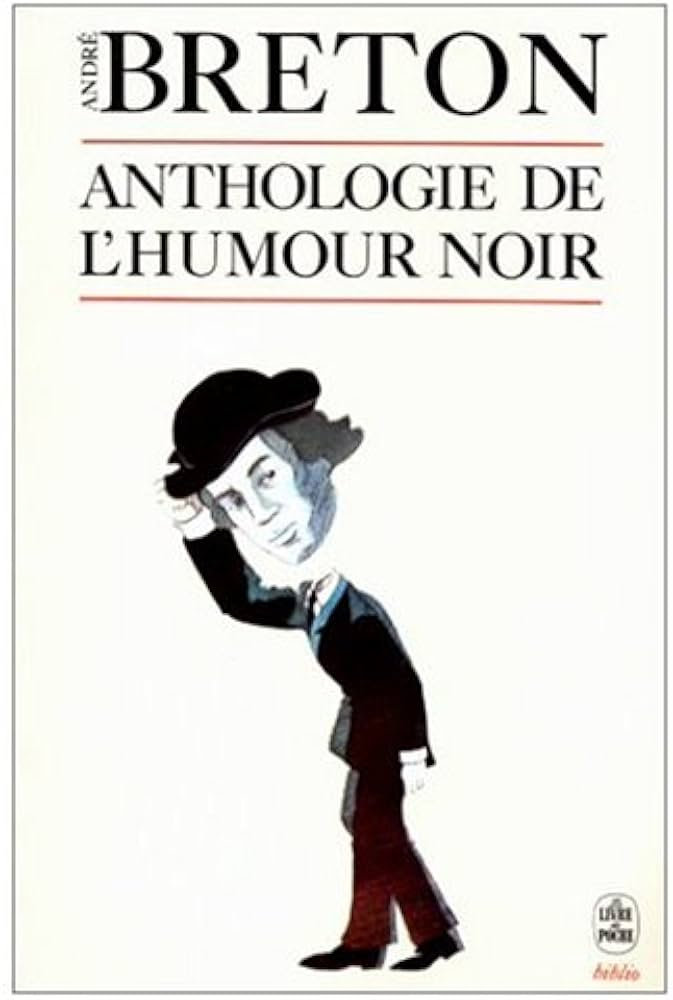

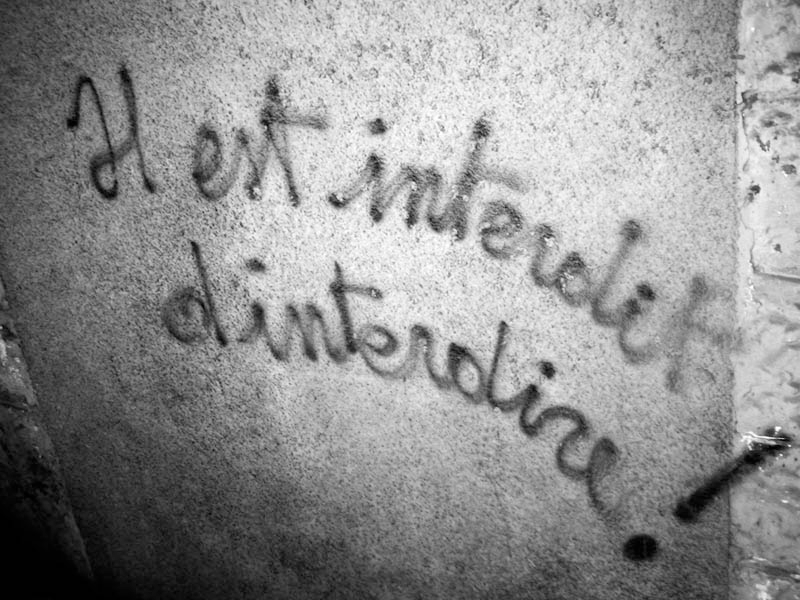

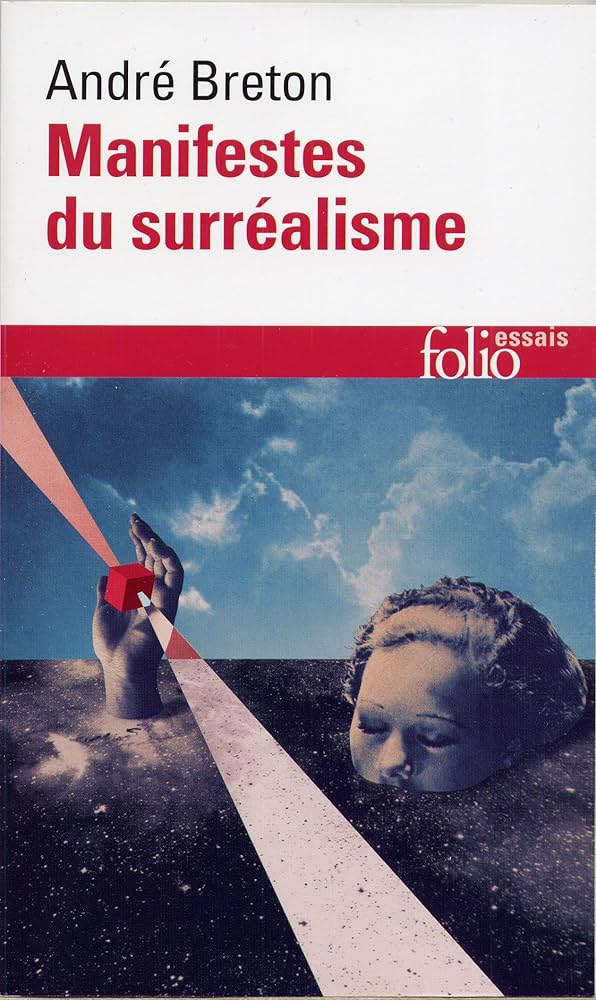

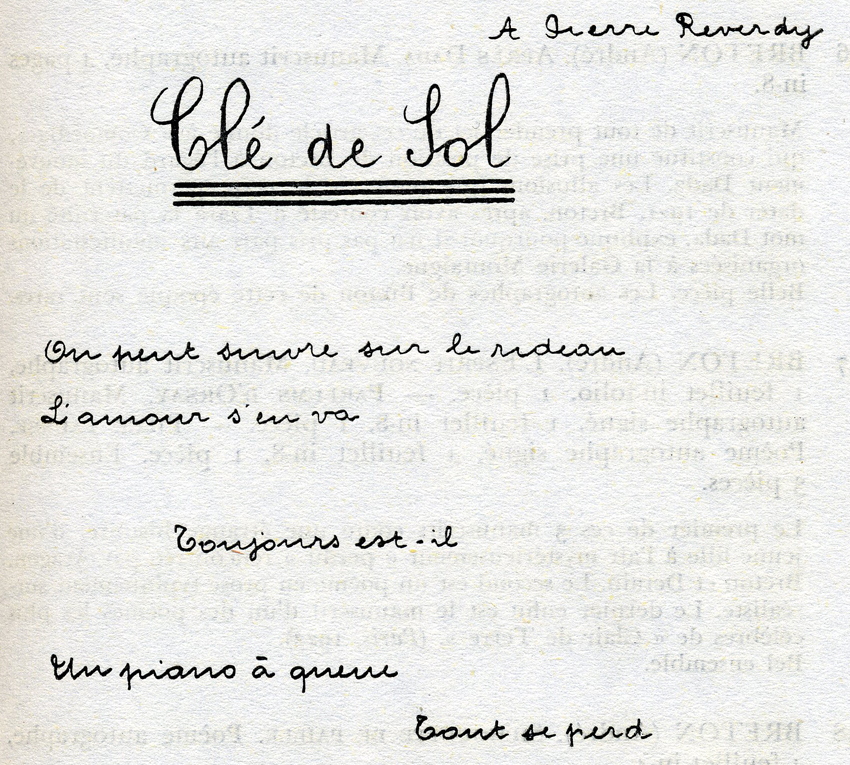

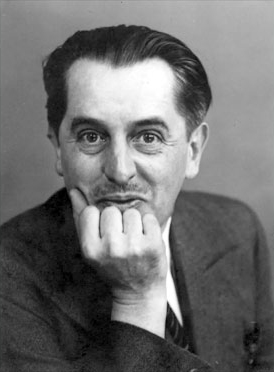

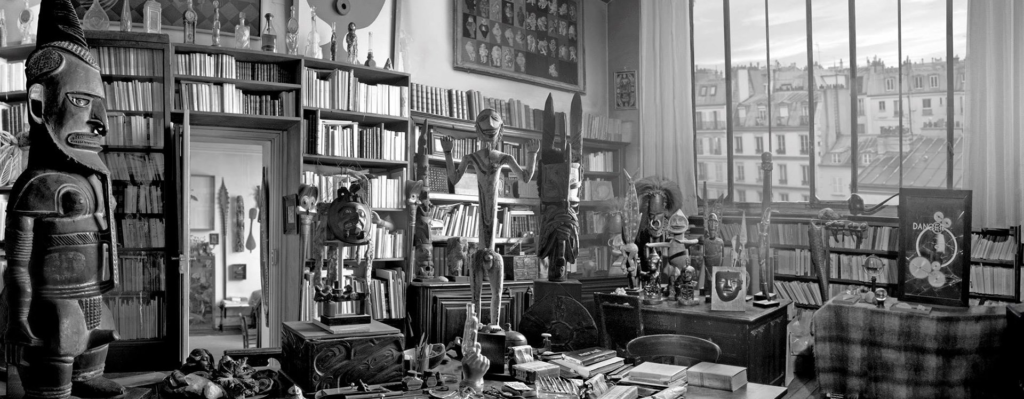

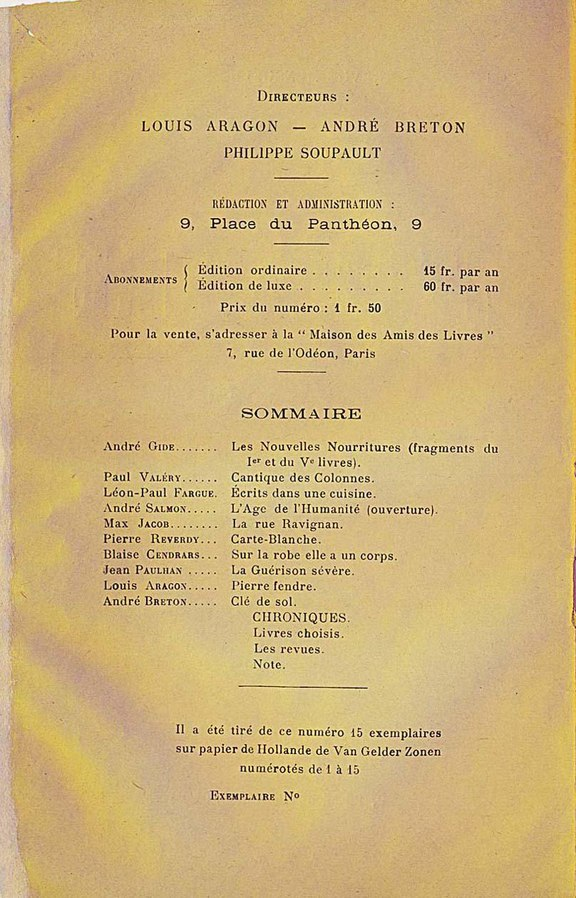

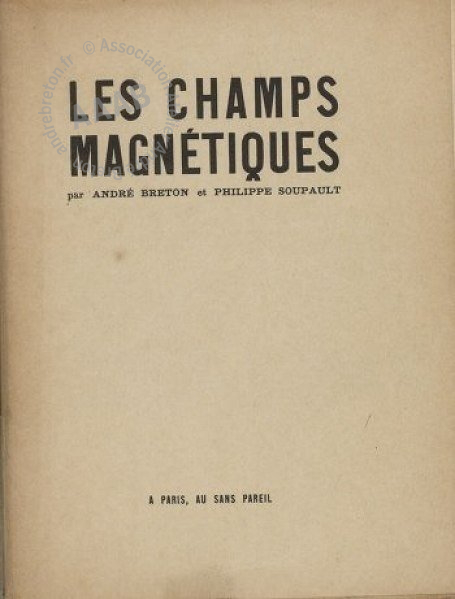

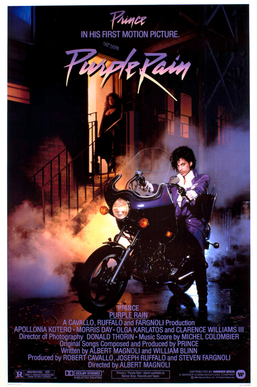

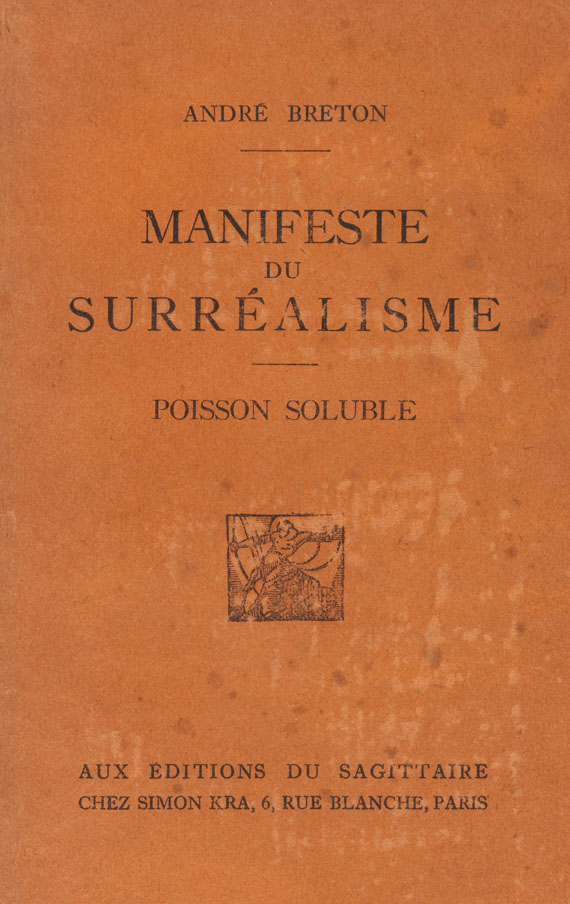

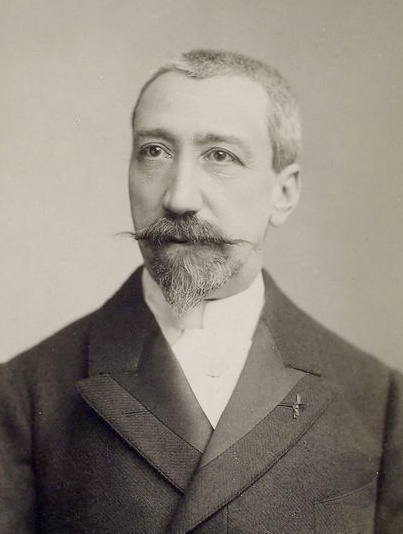

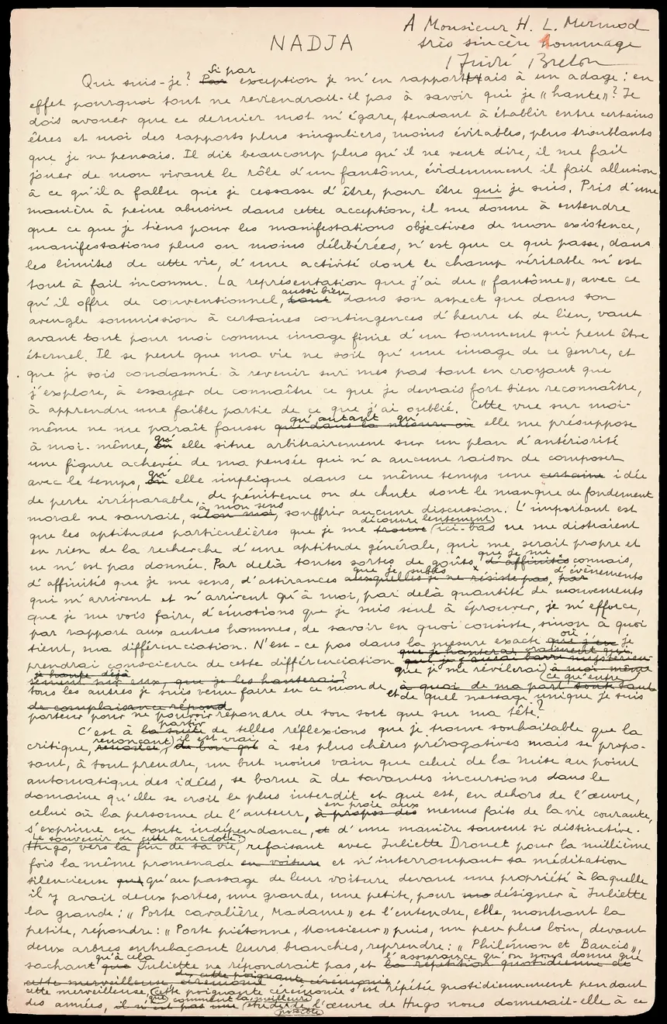

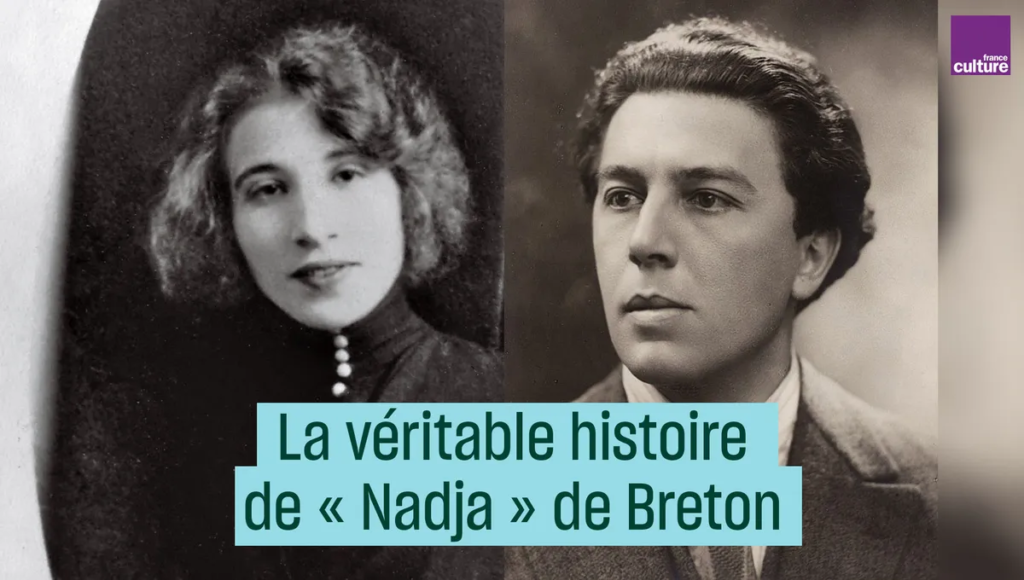

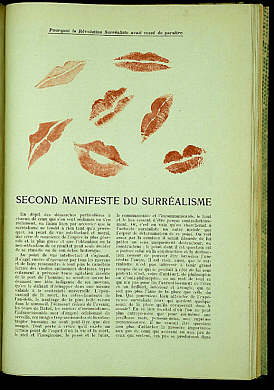

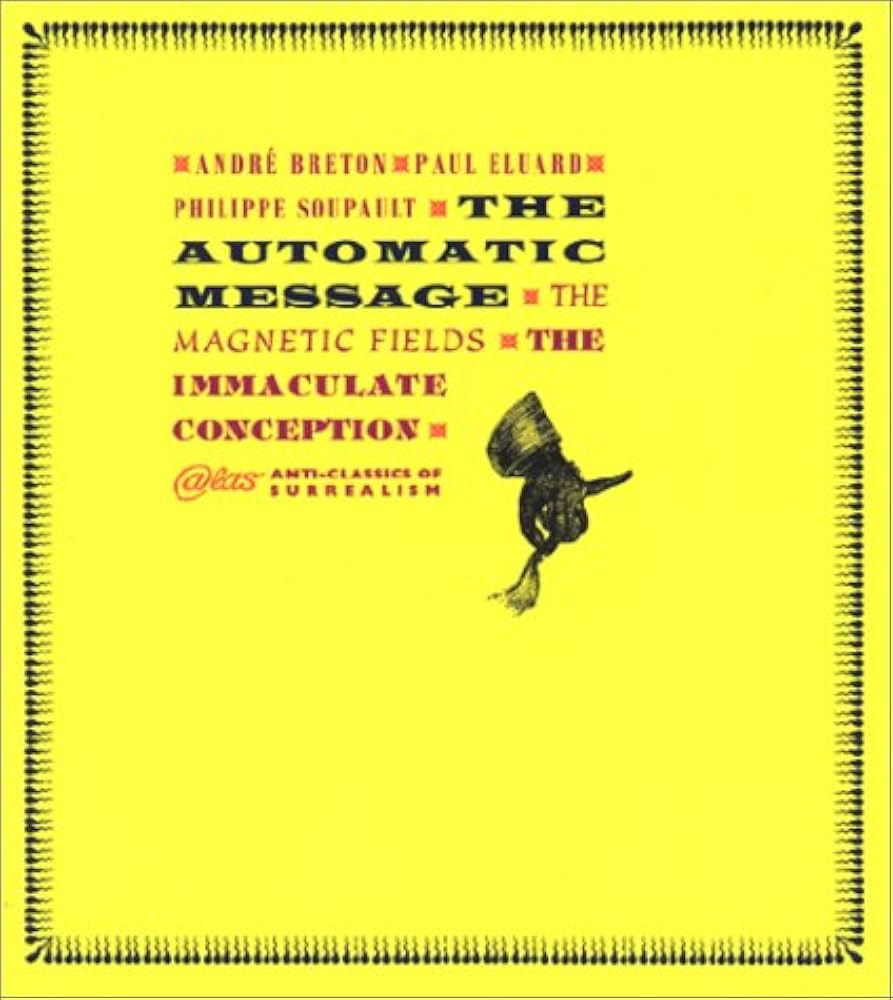

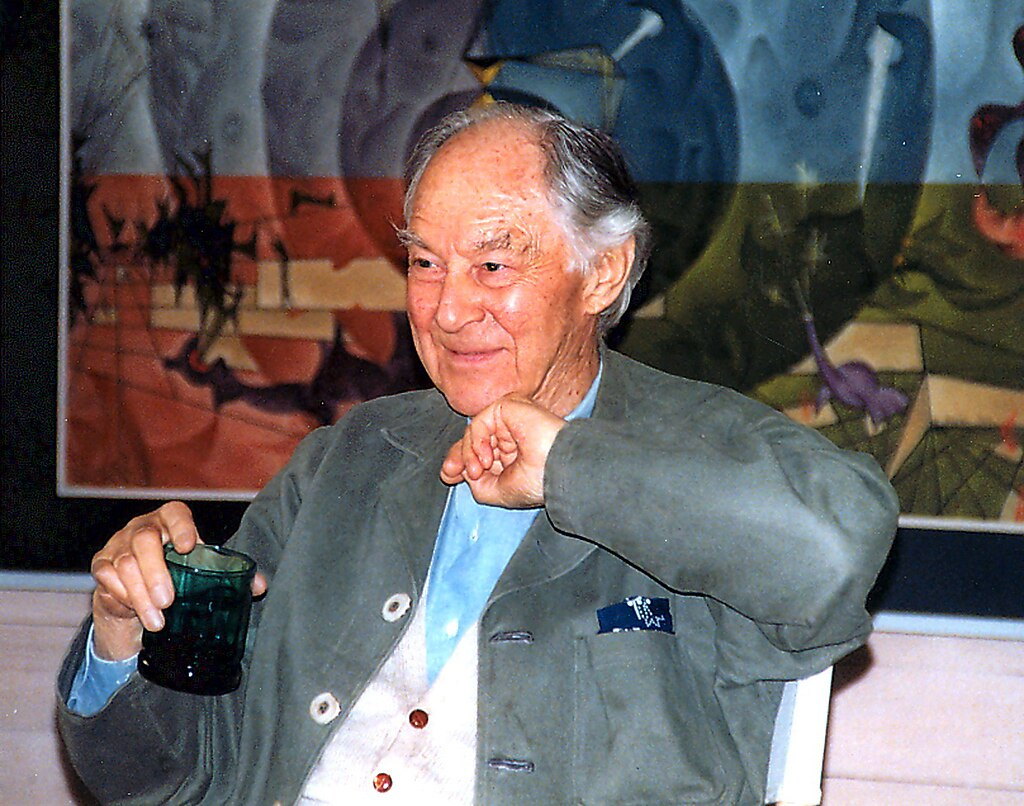

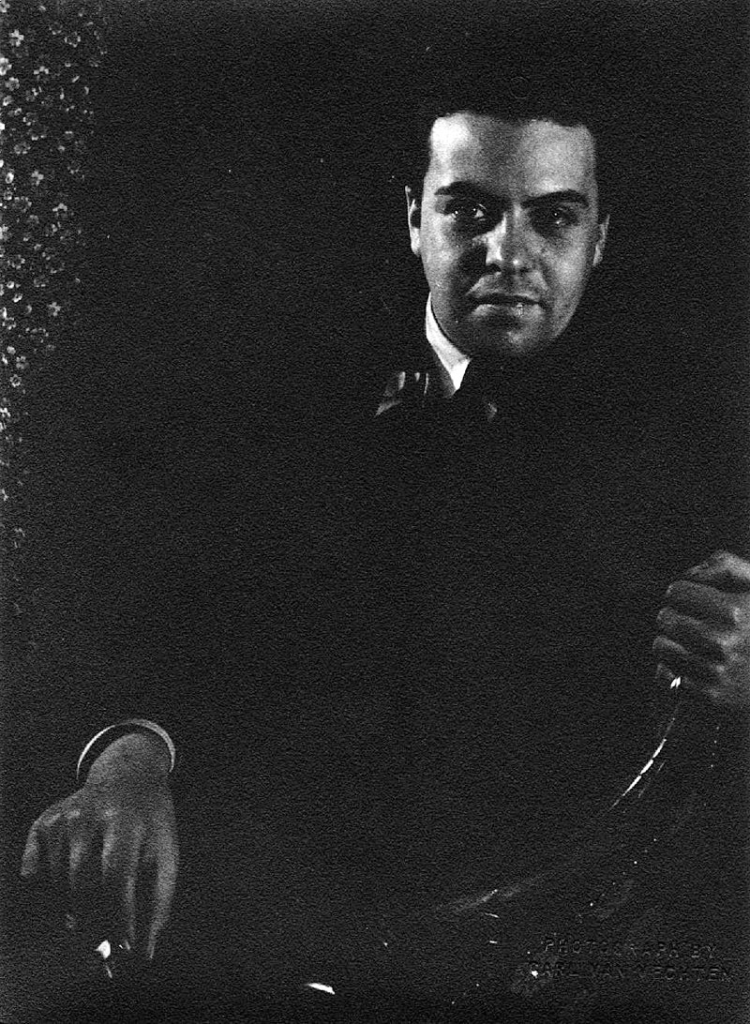

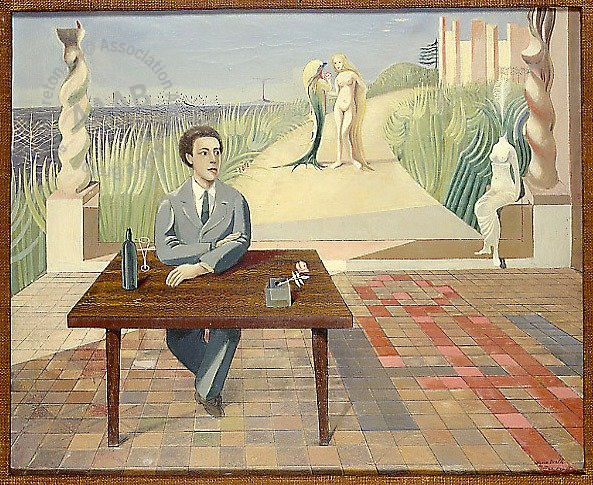

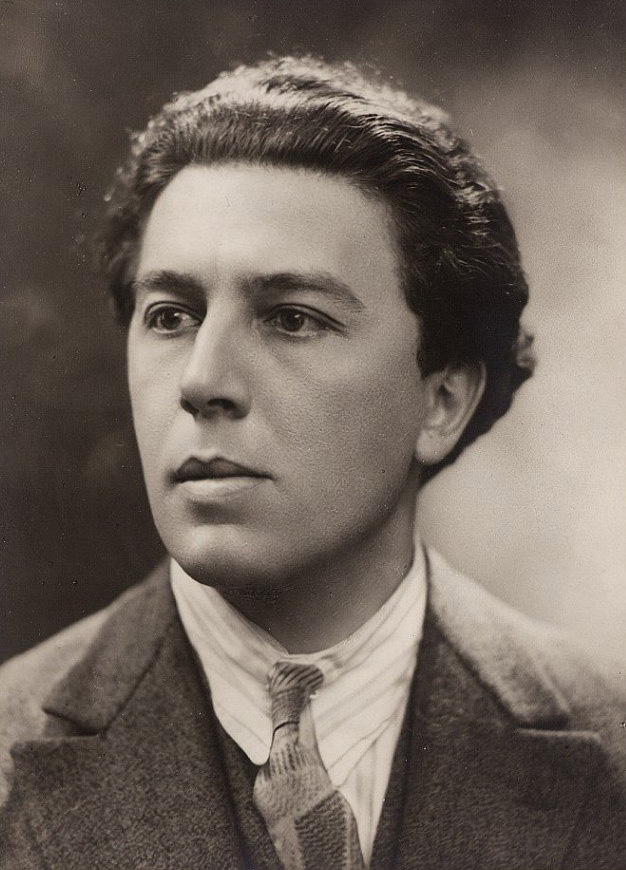

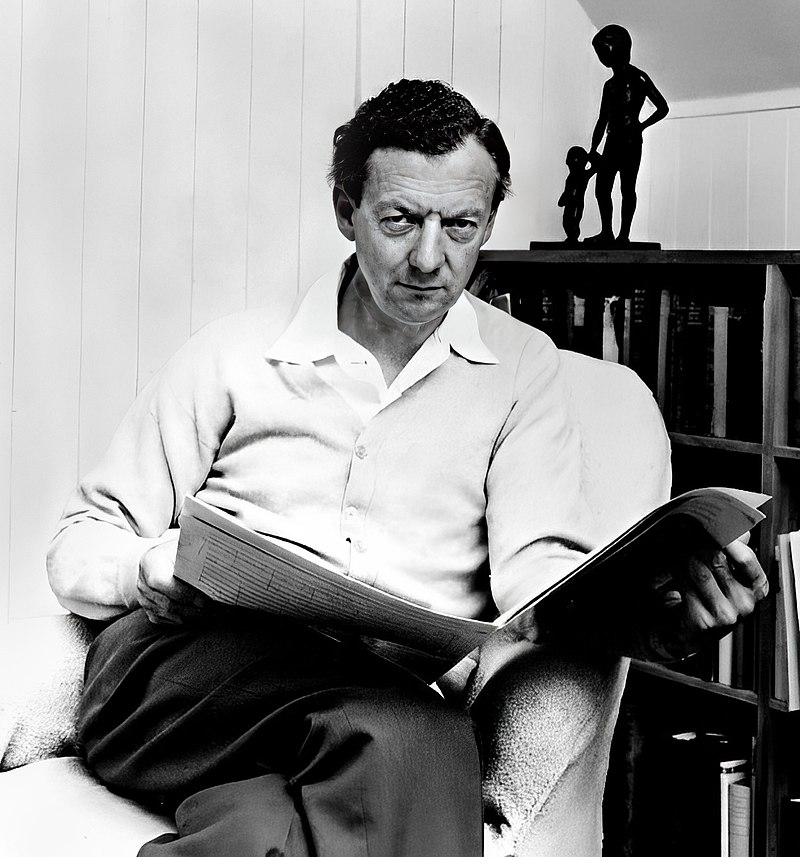

André Robert Breton (19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism.

His writings include the first Surrealist Manifesto (Manifeste du surréalisme) of 1924, in which he defined surrealism as “pure psychic automatism“.

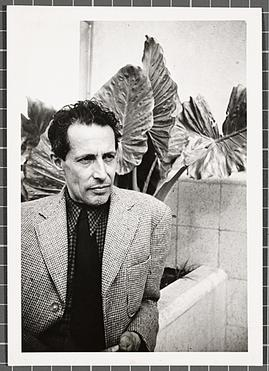

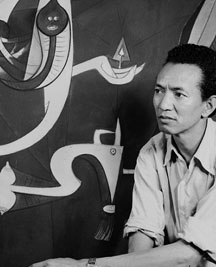

Above: André Breton

Along with his role as leader of the surrealist movement he is the author of celebrated books such as Nadja and L’Amour fou.

Those activities, combined with his critical and theoretical work on writing and the plastic arts, made André Breton a major figure in 20th century French art and literature.

André Breton was the only son born to a family of modest means in Tinchebray (Orne) in Normandy, France.

His father, Louis-Justin Breton, was a policeman and atheist.

His mother, Marguerite-Marie-Eugénie Le Gouguès, was a former seamstress.

Breton attended medical school, where he developed a particular interest in mental illness.

His education was interrupted when he was conscripted for World War I.

Above: Tinchebray, Orne Department, France

During World War I, he worked in a neurological ward in Nantes, where he met the Alfred Jarry devotee Jacques Vaché, whose anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition influenced Breton considerably.

Above: Nantes, Loire-Atlantique Department, France

Vaché committed suicide when aged 23.

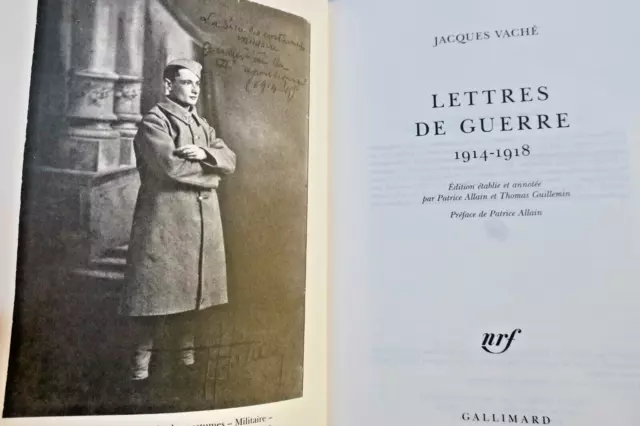

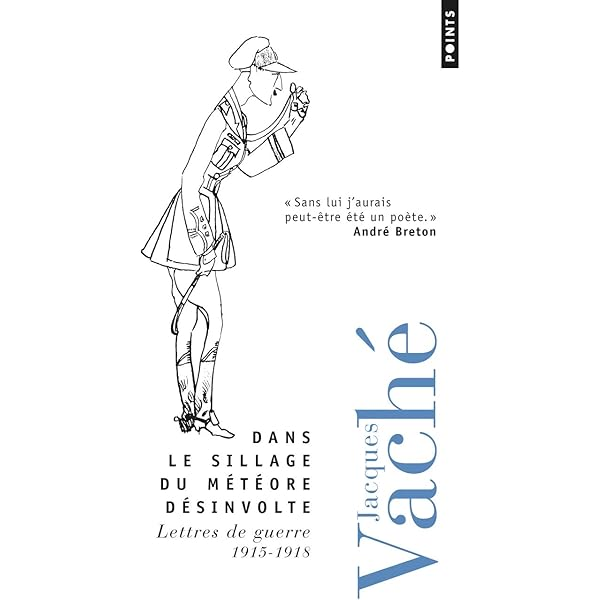

Above: French writer Jacques Vaché (1895 – 1919)

Vaché was one of the chief inspirations behind the Surrealist movement.

He left behind only a series of letters, a few texts and a few drawings.

The tone of his work is deliberately provocative, pacifist and even anti-militarist.

Called to the Front during the First World War, he returned wounded and deeply marked.

His personality had a profound influence on the surrealists and, in particular, on André Breton, whom he met during his convalescence.

Breton would mythologize Vaché and consider him as the precursor of the movement in his Manifesto of Surrealism.

Breton said:

“En littérature, je me suis successivement épris de Rimbaud, de Jarry, d’Apollinaire, de Nouveau, de Lautréamont, mais c’est à Jacques Vaché que je dois le plus.”

(“In literature, I was successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most.”)

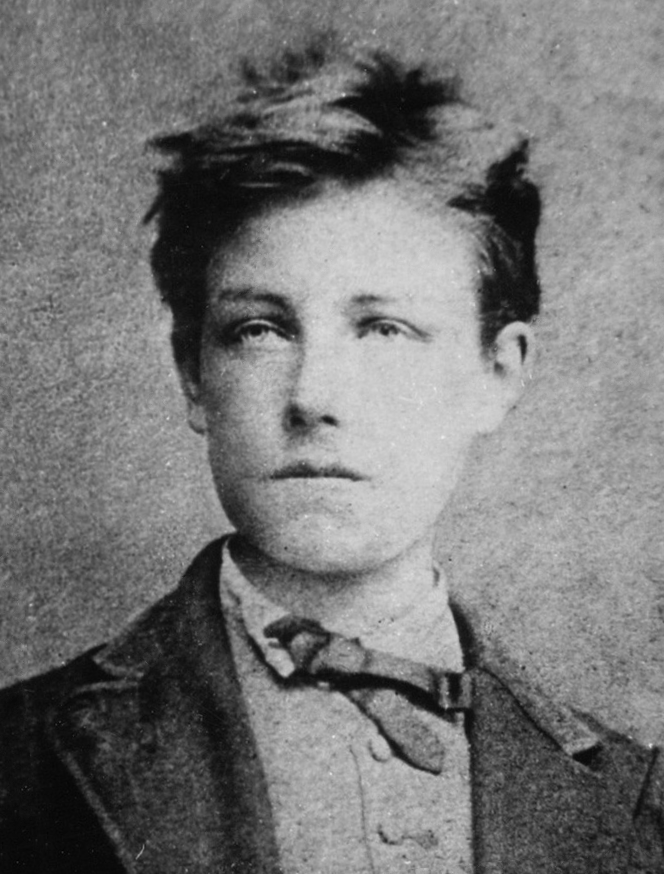

Above: French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854 – 1891)

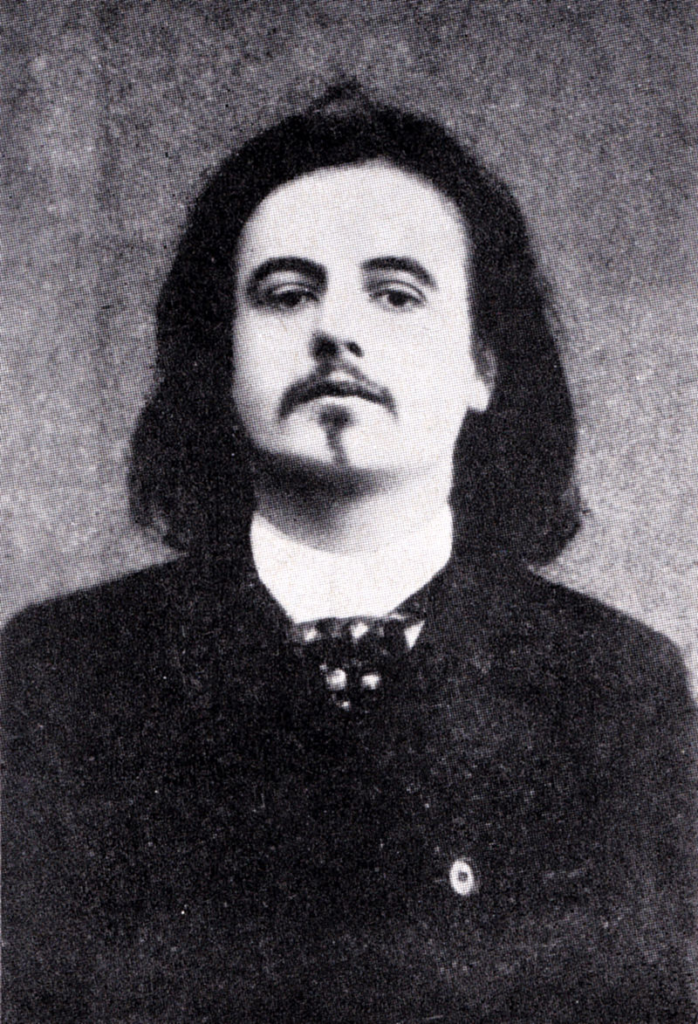

Above: French writer Alfred Jarry (1873 – 1907)

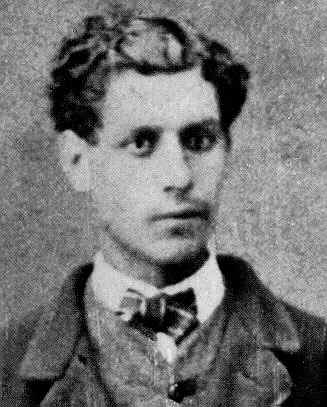

Above: French writer Guillaume Apollinaire (1880 – 1918)

Above: French poet Germain Nouveau (1851 – 1920)

Above: Uruguayan French poet Isidore Lucien Ducasse (aka Comte de Lautreamont) (1846 – 1870)

Above: Jacques Vaché

Jacques Vaché came from a family originally from Aytré on his father’s side, whose mother was English, and from Noizay on his mother’s side.

His father, James Samuel Vaché, was an artillery captain.

Born in Lorient, Jacques Vaché lived for a while in Indochina where his father was posted.

Above: Lorient, Morbihan Department, France

Above: French Indochina (1887 – 1954)

In 1910, his father was posted to Senegal.

Jacques was then sent to his uncle and aunt Guibal in Nantes.

Above: Nantes, Loire-Atlantique Department, France

Initially a student at the Externat des Enfants Nantais, Vaché was expelled in March 1911.

He then joined the Grand Lycée de Nantes (now the Lycée Clemenceau), where Vaché demonstrated literary talent.

Above: Lycée Clemenceau, Nantes

With his classmates Eugène Hublet, Pierre Bissérié and Jean Bellemère (alias Jean Sarment), he founded the “Sârs group” also known as the “Nantes group“.

Passionate about poetry, theatre and literature, they all wrote.

At the beginning of 1913, Sarment even became the Nantes correspondent for the magazine Comoedia Illustrée.

Bissérié and Vaché also practiced drawing.

Above: Eugene Hublet (1896 – 1916)

Above: Pierre Bissérié

Above: Jean Bellemère (aka Jean Sarment) (1897 – 1978)

“They have their conventions, their code, their personal accommodations with the French language.

Their sense of values and hierarchies.

Thus, they have established a social classification.

At the top, the “Mîmes”.

Why?

They like the word.

It evokes the “mystical grandeur of silence that expresses itself”, as Jacques Bouvier [alias Vaché] defined it.

Below the “Mîmes”, the “Sârs”, homage to Péladan, to the esoteric “Rose Croix”, to anything you want, which they do not seek to specify.

Below: men (homo vulgaris).

Below men, sub-men.

Below sub-men, “supermen”.

Further down, going down the ladder, the non-commissioned officer.

And, at the last rung, sunk in shame and ignominy – another delicate idea of Bouvier’s – the “generals”.

No one deigns to use the agreed plural.

A general, generals.

Only Bouvier persists in asking whether one could not find for his father colonel a designation – below general – which would make of this nervous, authoritarian, highly decorated and very aged little man, and doubtless very tired, something like an “untouchable”.

Jean Sarment, Cavalcadour (1977)

Above: Passage Pommeraye, Nantes

If I had to designate a place of surrealist imagination in Nantes, it would undoubtedly be the Passage Pommeraye.

This covered gallery, with its exuberant and fantastic decor, capturing shadow and light, inspires surrealist writers.

The Parisian covered passages are frequented by these artists: Aragon sees there a “modern light of the unusual“, Breton “the shadow and the prey melted in a single flash“, but it is in Nantes that Pieyre de Mandiargues makes it the subject of one of his short stories.

In Le Passage Pommeraye, the place is mysterious, the encounter with the woman-creature disturbing, the descent into the depths of the Fosse fatal.

“But I suddenly saw this crushing mouth move in front of me.

These beautiful rounded lips opened, hesitated, turned back with the appearance of the most complete confusion, let out a single word that the echo reverberated at length in the emptiness of the deserted gallery:

“Echidna”.

It was the only time I ever heard this voice and this northern hoarseness, a little singsong, coming as if with effort from a tight throat.”

André Pieyre de Mandiargues, Le passage Pommeraye in Le Musée noir (1946)

Sarment also evokes these years of youth in his first novel,

Jean-Jacques de Nantes:

In the group, Vaché is the Anglomaniac dandy inspired by Oscar Wilde.

He may already be reading Alfred Jarry.

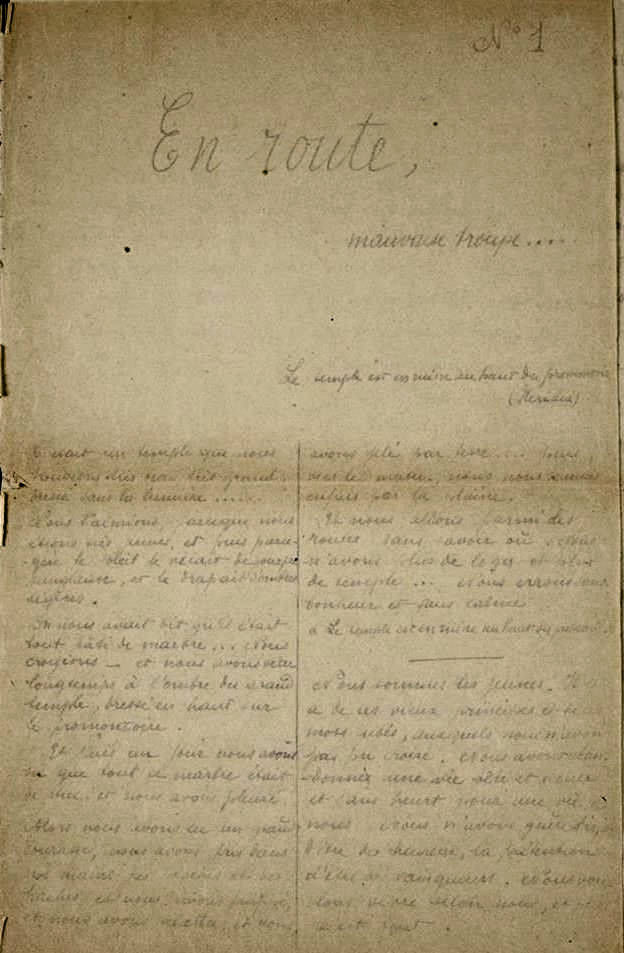

At the beginning of 1913, the Sars founded a first magazine entitled

En route mauvaise troupe! (“On the road, bad troop!“), in homage to Paul Verlaine, which only had a single issue printed in 25 copies.

Above: French writer Paul Verlaine (1844 – 1896)

The tone of the content, described as “subversive and pacifist” – independence of mind, freedom of criticism and hatred of the bourgeoisie, conventions and the army – triggered clashes within the school.

Above: First page of the Sârs magazine En route mauvaise troupe! (February 1913)

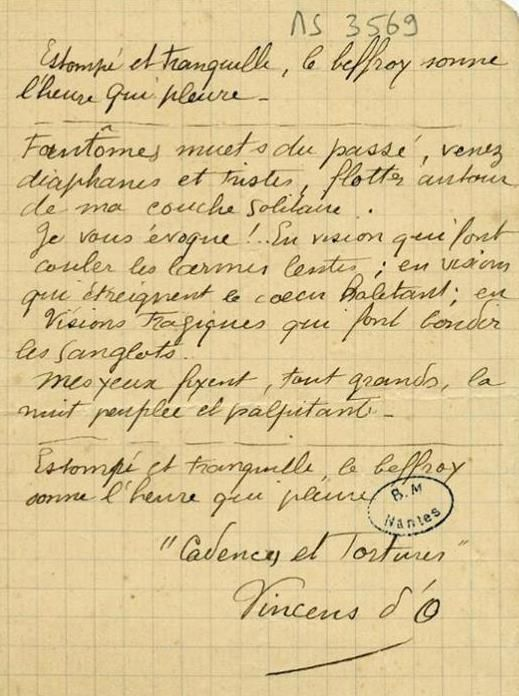

In this magazine to which Vaché contributed two poems, an article by Pierre Riveau, inspired by Kropotkin, and entitled “L’anarchie ” appeared, which triggered the affair within the high school.

Above: “Fade and Quiet“, a prose poem by Vaché, published in En route mauvaise troupe!

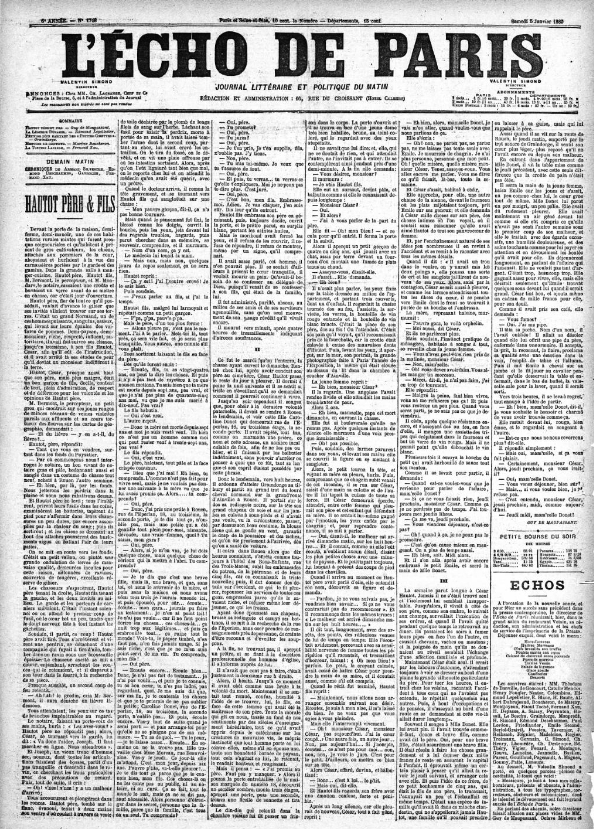

The controversy swelled in the local newspapers, and was even reported in some conservative Parisian dailies such as l’Écho de Paris.

This incident earned him exclusion from the school.

The four comrades continued their literary activities in spite of everything, and published four issues of Le Canard sauvage in the

same spirit.

Above: The Sârs’ second magazine Le Canard Sauvage (“the wild duck“)

The young poets finally experiment with collective writing, of which a few rare manuscripts have been preserved by Jean Sarment.

In Cavalcadour, Sarment recounts a session during which the Sârs devote themselves to this “unanimous poetry“:

“Each will add a verse; or two, if inspiration strikes.

HARBONNE [alias Hublet] – I had a heart, I had a soul

BOUVIER [alias Vaché] – Listen to my epithalamium.

HARBONNE – My soul has gone among the trade winds.

PATRICE [aka Sarment] – I searched for my soul everywhere.

BOUVIER – where the riverboats took me…

BILLENJEU [alias Bisserié] – at the Eskimos and Kalmyks.

PATRICE – In my buttercup suit.

BILLENJEU – I went to the pink pole

BOUVIER – the pink pole of the North Pole

HARBONNE – I drank the dew from the evening mirror…

BOUVIER – And then the incense from the censer…

And this continues, ad libitum, until we want to move on to something else.

Jean Sarment, Cavalcadour, 1977.

It is at the port of Trentemoult that the Sârs group meets for the last time.

It is October 1914.

The war has begun.

The young people sit down at one of the port’s cafés.

They already know they are destined for somewhere else.

In Calvalcadour, Jean Sarment recounts that before parting ways and to keep a record of this moment, they once again indulge in a writing game.

The tone is casual and disillusioned:

“You are right.”, said Billenjeu (Bissérié).

“We must not let anything go to waste.”

With his pipe in the corner of his lips, he absorbed himself in a meticulous task.

From a blotter that extolled the virtues of an aperitif, he took yellowish envelopes, emptied them with small jolts, well and evenly distributed, the contents of the ashtray, sealed them, traced an inscription in arabesques on the one that he handed to Harbonne (Hublet).

“Here, old man, put this aside for the future.”

Harbonne reads:

“Ashes of our dreams“.

“Why not?“, he says.

Hip, hip, hip.

Everyone has their envelope.

Everyone writes the inscription on it with ironic gravity.

“Ashes of our dreams“.

“Oh!“, said Bouvier (Vaché).

He dropped his monocle as if overwhelmed with nostalgia and, not to be like everyone else, in his little upside-down handwriting, wrote in green ink:

“Ashes of our dreams“.

Mobilized in August 1914, Vaché was sent to the Front incorporated into the 19th Regiment in June 1915 then into the 64th Regiment.

Above: Jacques Vaché (right) in the French Army

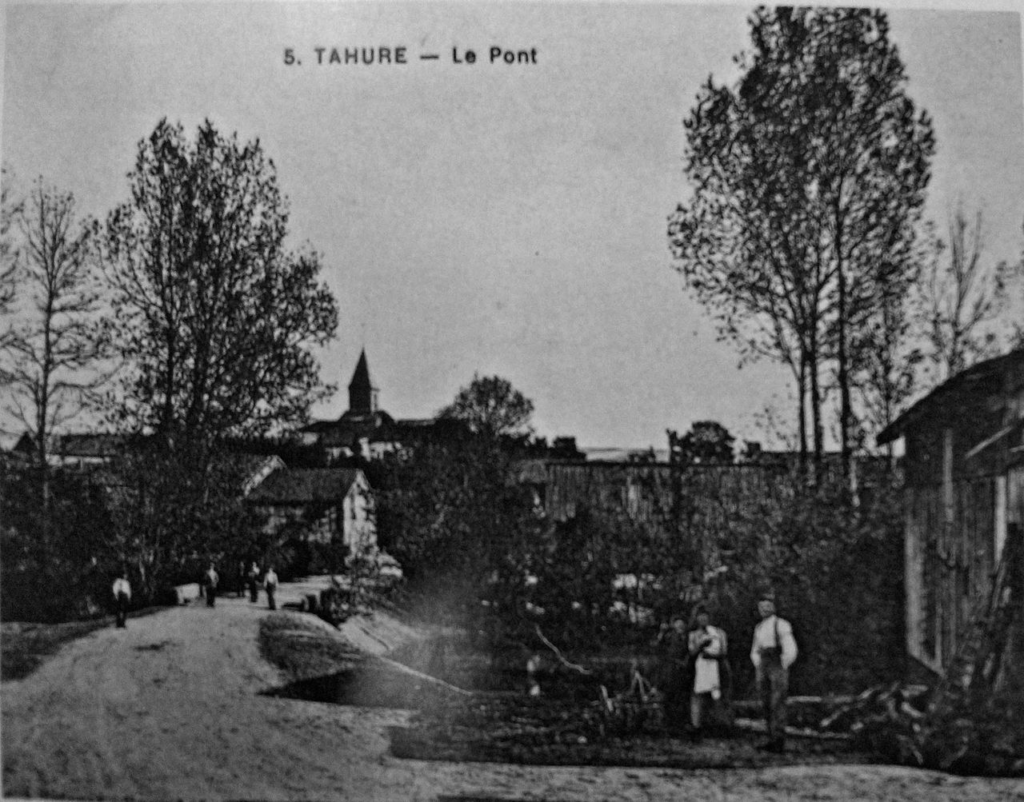

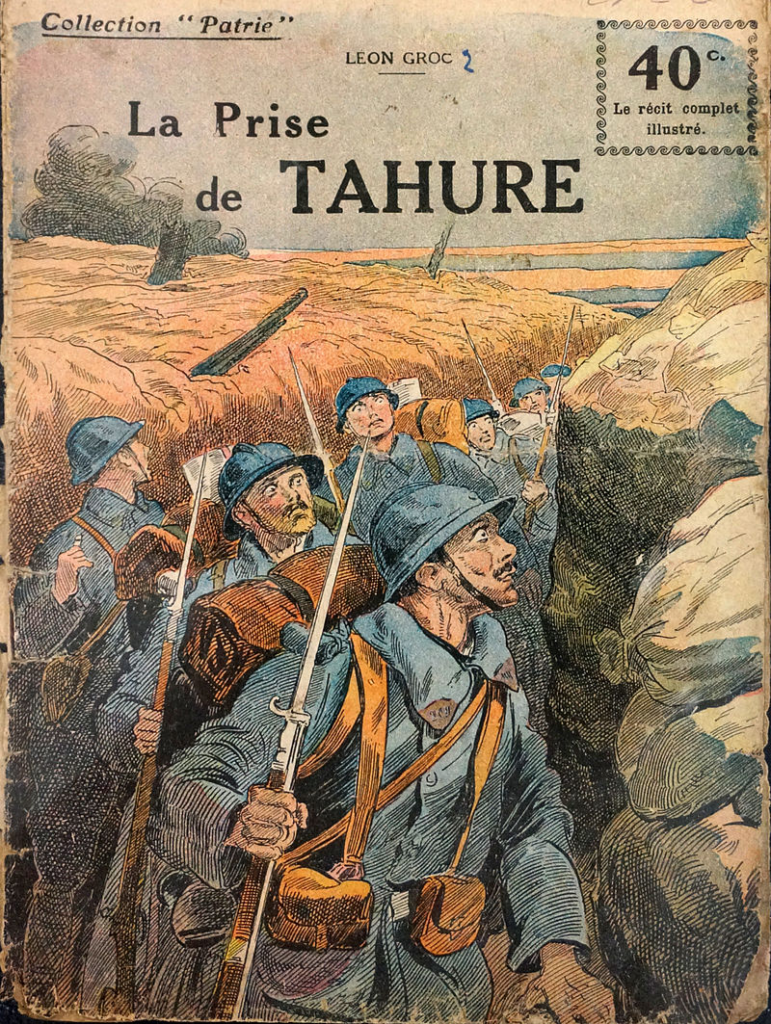

He was wounded in the legs on 25 September 1915 in Tahure, following the explosion of a bag of grenades during the Battle of Champagne (25 September – 6 October 1915).

Above: Tahure, Marne Department, France, before the First World War

The village of Tahure, located near the source of the Dormoise River, covered 2,200 hectares of arable land and 112 hectares of woods.

It had 185 inhabitants in the 1911 census.

The church, which the municipality had just equipped with a new clock in the spring of 1914, lost its bell tower during the fighting in September 1914 and was reduced to ruins following incessant artillery fire.

The terrible fighting that took place in this sector where the Germans had firmly entrenched themselves after the First Battle of the Marne (5 – 12 September 1914), wiped out the village.

It never rose again, a victim of this war.

When the Suippes military camp was created in 1950, the commune was officially abolished and its territory attached to the neighboring commune of Sommepy, which then took the name Sommepy-Tahure to perpetuate the memory of the vanished village.

The memory of Tahure is preserved in the poem Le poète by Guillaume Apollinaire:

“For ten days at the bottom of a corridor too narrow

In the landslides and the mud and the cold

Among the suffering flesh and in the rot

Anxious we keep the road to Tahure“

Tahure is also mentioned in Guignol’s Band by Louis-Ferdinand Céline:

“Under the floods of fireworks.

Prancing for the challenges! and Tahure!“

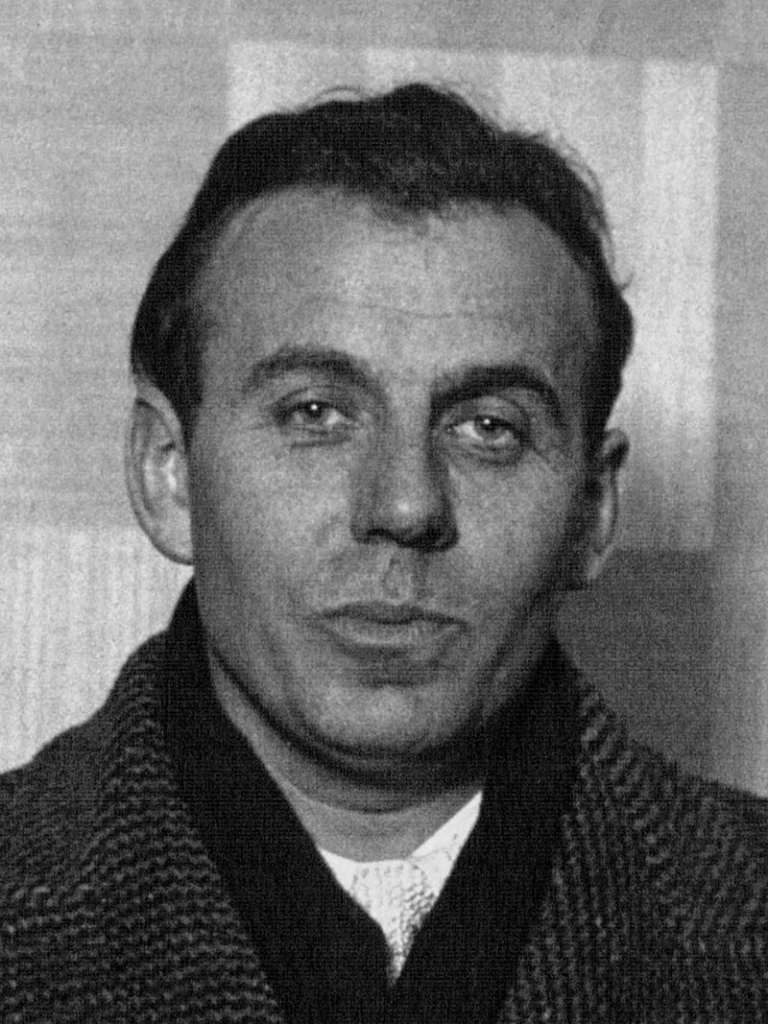

Above: French writer Louis Ferdinand Céline (1894 – 1961)

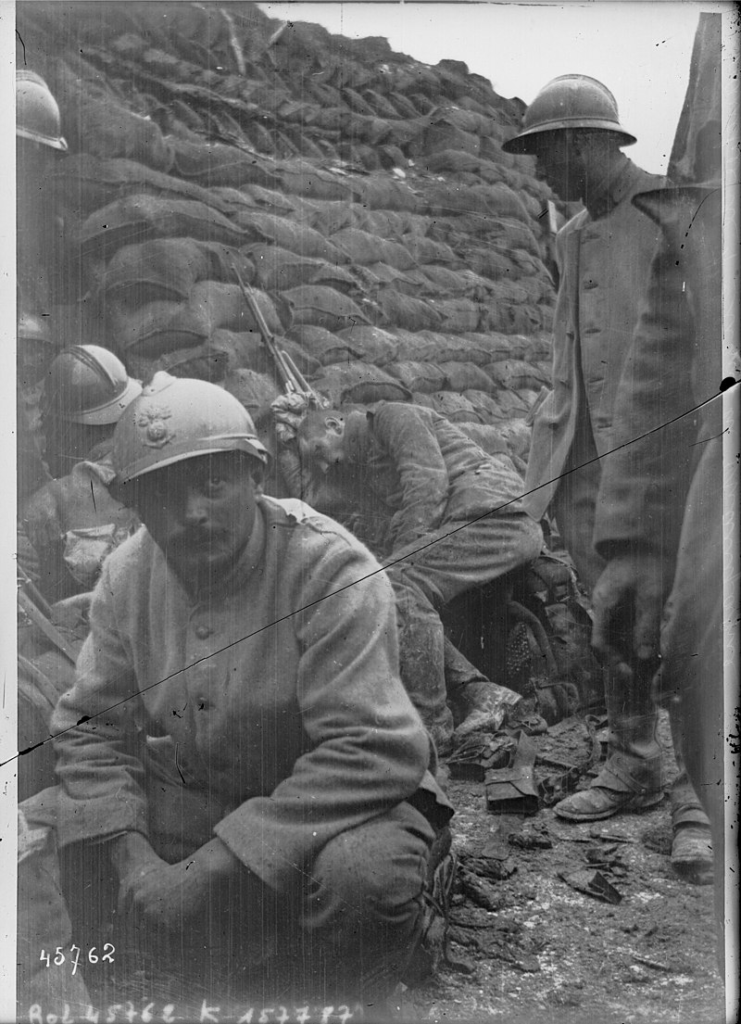

Above: Frontline trench, Champagne, France

The objective set by General Joffre was fourfold:

- to limit the reinforcement of the German army on the Russian front and thus help Russia, which had lost Poland and whose armies were in retreat

- to convince certain still neutral nations to enter the war on the side of the Allies, particularly Italy

- relaunch the war of movement to restore the morale of the French military, which had been considerably undermined by the Allied inaction, and to end the War as soon as possible

- possibly allowing Joffre to strengthen his credibility with the French political authorities.

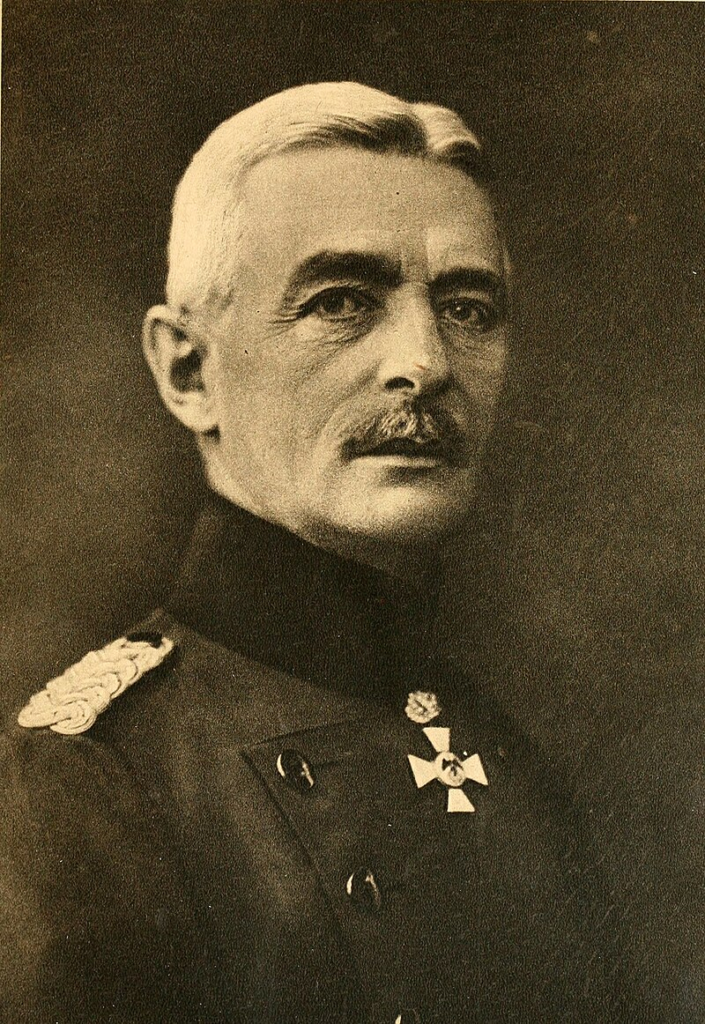

Above: French General Joseph Joffre (1852 – 1931)

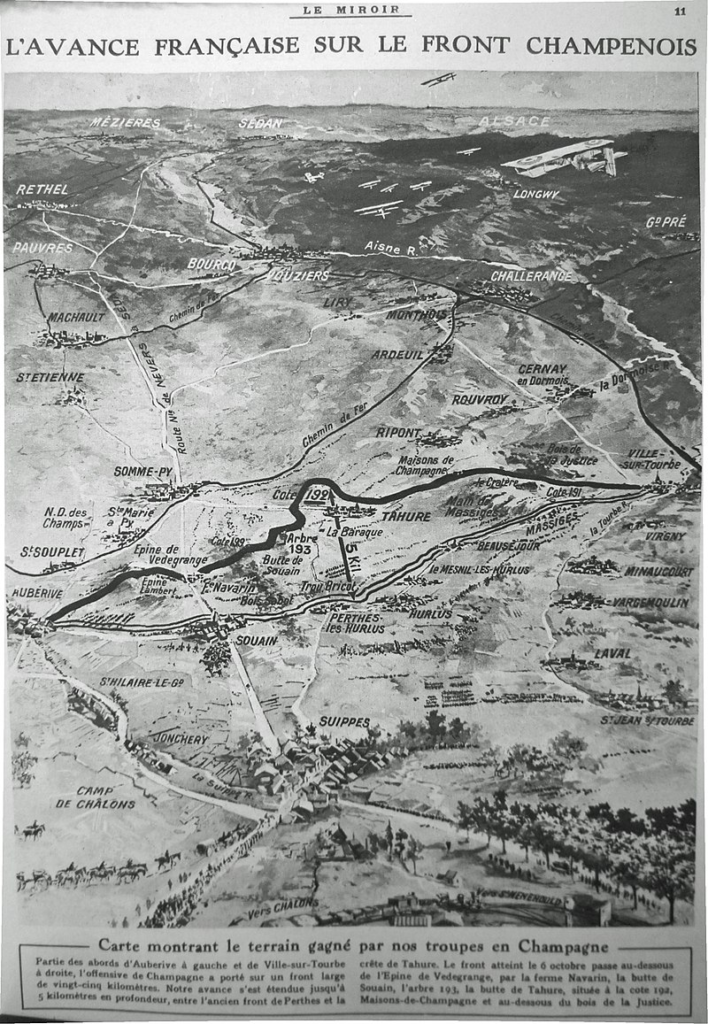

The principle was to launch a massive offensive in a sector limited to 25 kilometers between Aubérive on the Suippe valley and Ville-sur-Tourbe to obtain the break, ensure a deep exploitation on the rear of the German army, and force the withdrawal of the entire western part of its device.

Above: Aubérive Church, July 1915

Above: Ville sur Tourbe, before the First World War

This is the reason why each army was reinforced by a cavalry corps.

This attack was coordinated with a joint Franco-British offensive in Artois which served as a fixed point for the Germans.

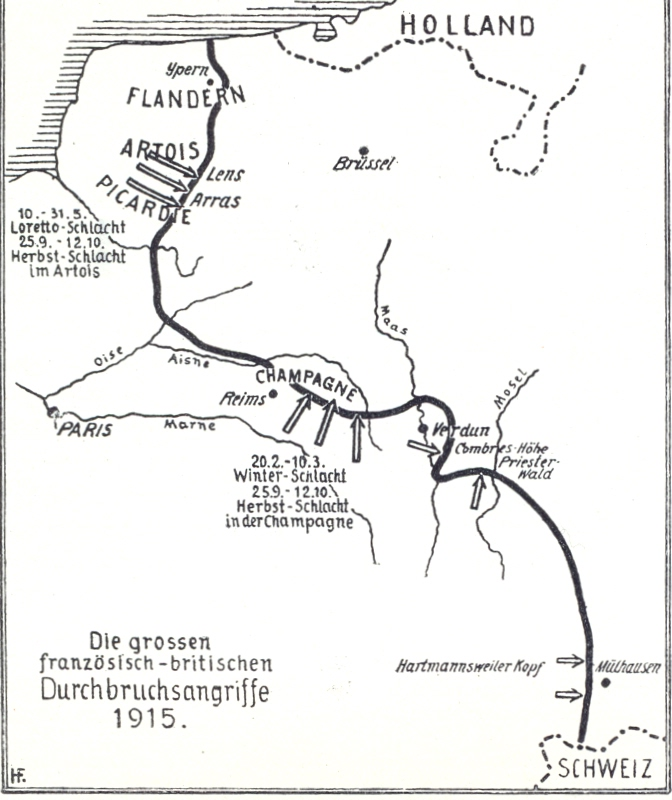

Above: French-British offensive, 1915

This sector of Champagne was chosen by General de Castelnau because of its geographical characteristics.

The terrain was relatively flat.

There were no built-up areas that could serve as a point of resistance for the Germans.

The terrain was either open or diffusely wooded, suitable for ensuring a smooth progression of the assault waves.

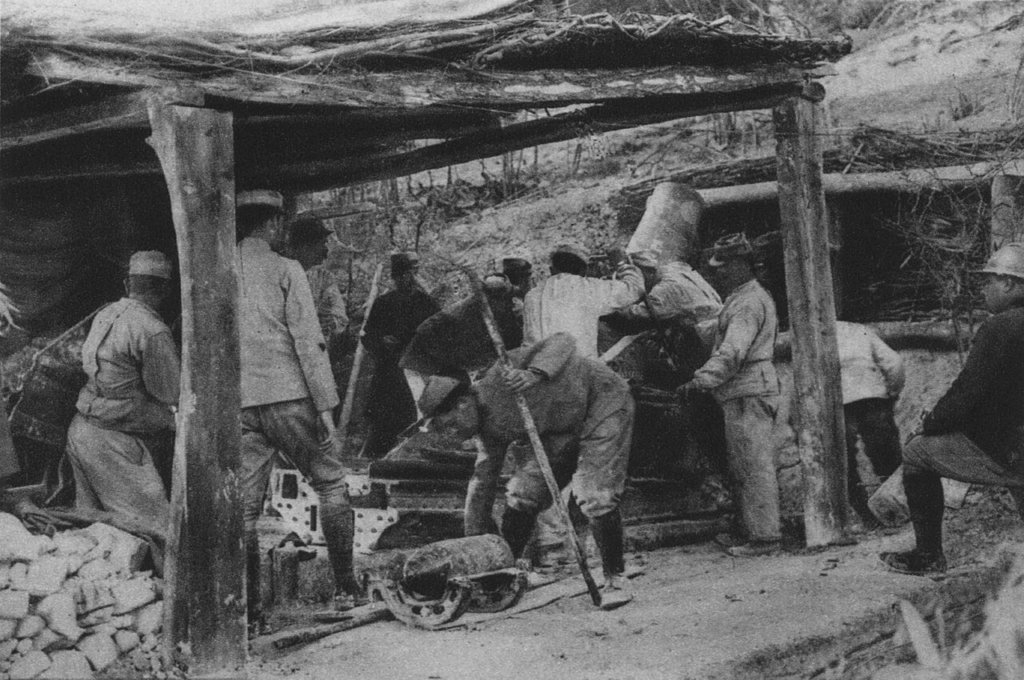

It was therefore a question, after a massive artillery preparation to be guided by the Air Force, of conquering the German lines by attacking the resistance points head-on and enveloping them from the flanks with interval troops in continuous waves until the rupture was created and exploited with the help of the second line troops.

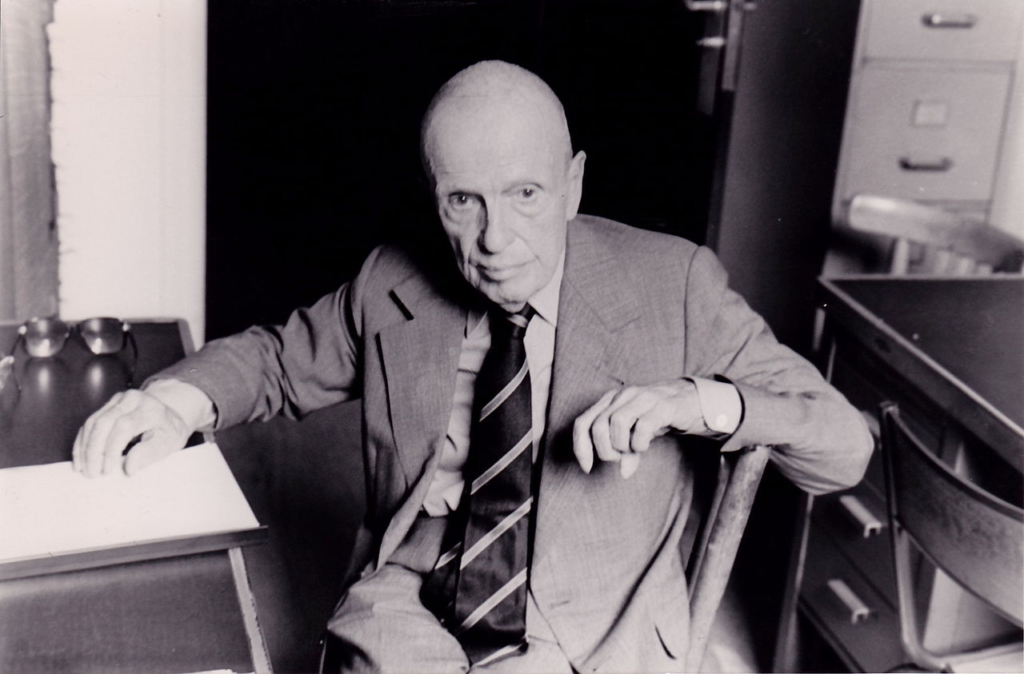

Above: French General Édouard de Castelnau (1851 – 1944)

The Second Battle of Champagne left 27,851 killed, 98,305 wounded, 53,658 prisoners or missing on the French side and much lower losses on the German side.

The Front advanced 3 to 4 km, but the breakthrough was not achieved.

The Germans were able to cope initially with local reserves and, in a second phase, with the arrival of the 10th Corps initially intended for Russia.

It demonstrated the impossibility of crossing two lines of defense in a single movement without inter-arms preparation and coordination and the need to treat each line separately.

It also demonstrated the lack of cooperation between the lines within the French armies, particularly between heavy artillery and infantry, partly due to the absence of aviation due to weather conditions to inform the gunners.

It saw the introduction of the Adrian helmet and the massive use of trench artillery.

The Battle was a significant success in terms of logistics and movements, but showed a lack of preparation for the number of shells in reserve.

Foch’s failed offensive in Artois a few months earlier had made a serious dent in the stocks.

Above: French General Ferdinand Foch (1851 – 1929)

The allocation was 1,200 rounds per 75mm cannon.

It was burned in six days.

1,200,000 shells were consumed on this offensive.

The strategic reserves would be doubled.

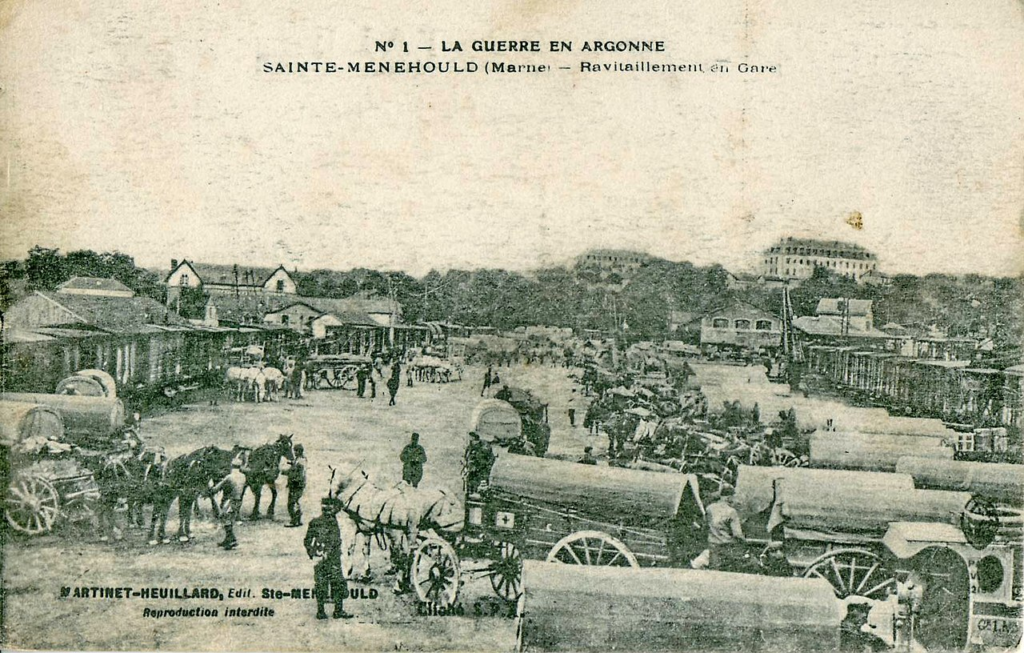

Above: Logistics was an essential element in enabling major battles. Here, French supplies at Sainte-Menehould station.

Vaché was repatriated to Nantes for treatment.

At the military hospital on rue Marie-Anne-du-Boccage (future Lycée Guist’hau), to pass the time, he painted postcards depicting fashion figures accompanied by bizarre captions.

Above: Lycée Guist’hau, Nantes

A pacifist and anarchist, he was disgusted by war.

In his writings, he spoke of “the absolute reign of mud“, “the trench of corpses“, like a “sea of excrement” where “in the evening great desolate red twilights drag themselves“.

“I will come out of the war gently senile“, he admitted.

Above: Jacques Vaché

In January 1916, he met André Breton and Théodore Fraenkel assigned as medical interns to the military hospital.

A commemorative plaque erected on the centenary of this event commemorates this.

The two young men were barely 20 years old, but had already been confronted with the atrocities of war.

Jacques Vaché was assigned to the 64th Infantry Regiment in June 1915 and sent to the Front.

Wounded in the leg in September, he returned to Nantes at the end of the year.

André Breton was then an intern at the hospital on rue du Boccage.

For a few months, the two men conversed and discussed literature.

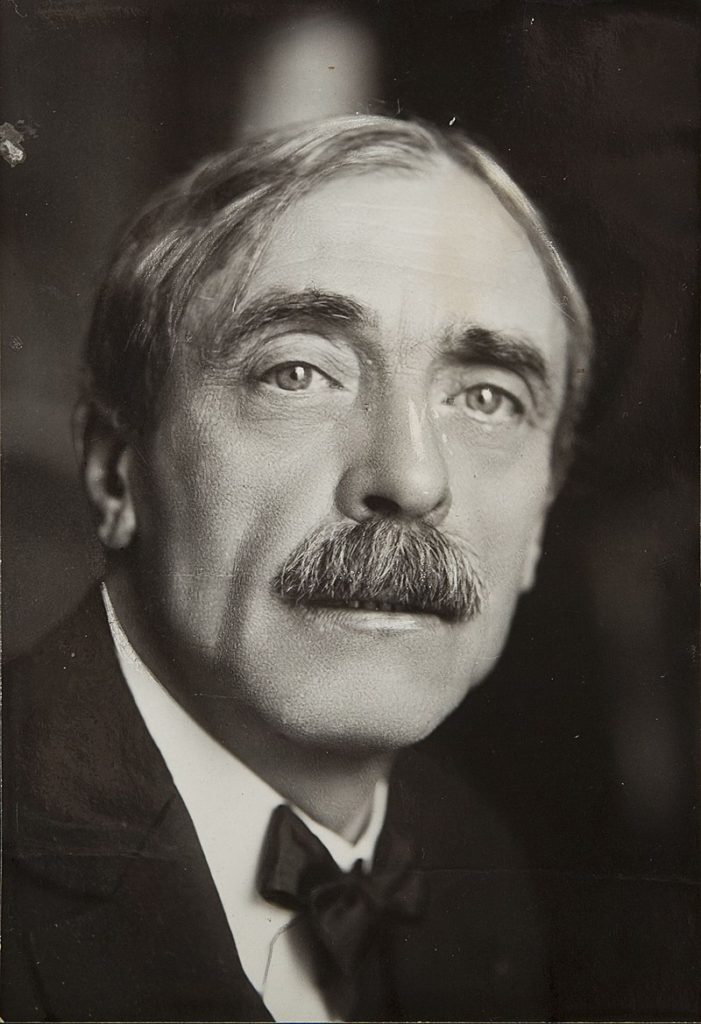

Together, they shared Mallarmé, Valéry, Apollinaire and Rimbaud.

Above: French poet Stéphane Mallarmé

Above: French writer Paul Valéry (1871 – 1945)

Beyond intellectual affinities, it is also a form of relationship to the world and to life that they maintain together, André Breton admiring in his friend his taste for dandyism and subversion.

These moments are short-lived since Jacques Vaché returns to the front in May 1916.

A few letters and a few meetings will follow.

André Breton keeps a tenacious memory of this period, having a deep admiration for Jacques Vaché, to the point of making him, posthumously, a figure of surrealism.

“Jacques Vaché is surrealist in me.”

André Breton, Manifesto of surrealism, 1924.

Above: André Breton (top right) and Théodore Fraenkel (top left), at the Lycée Chaptal, Paris, in 1912, who would become friends with Vaché during the war

André Breton was immediately seduced by the attitude of this “very elegant young man, with red hair“, who introduced him to Alfred Jarry, opposed to everyone “desertion within oneself” and obeyed only one law, “humor (without an h)“.

Above: Jacques Vaché

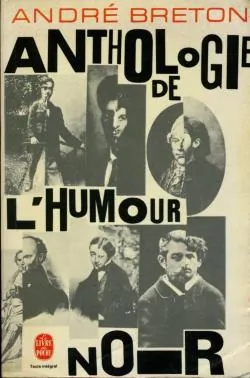

Despite his attempt to have the concept of umor explained by Vaché, Breton would spend part of his life looking for a definition.

It was probably a kind of black humor.

From his research, Breton would draw his Anthology of Black Humor.

As for Fraenkel, Vaché nicknamed him in his letters “the Polish people” and took him as a model for his short story “The Bloody Symbol” (character of Théodore Letzinski).

Above: French writer/doctor Theodore Fraenkel (1896 – 1964)

In March, Jacques Vaché was assigned to the auxiliary service due to myopia (short-sightedness).

In the month of May 1916, Jacques Vaché joined the 81st Infantry Regiment.

Above: Badge of the 81st Regiment

Later, because he spoke English fluently, he was sent back to the front as an interpreter for the British troops.

Contact with André Breton resumed in October with a first letter:

“I walk from ruins to villages with my crystal monocle and a theory of disturbing paintings – I have successively been a crowned writer, a famous pornographic cartoonist and a scandalous cubist painter.”

On 27 October 1916, his former comrade from the Nantes group, Eugène Hublet, was killed on the Somme Front.

Above: Tank, Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916)

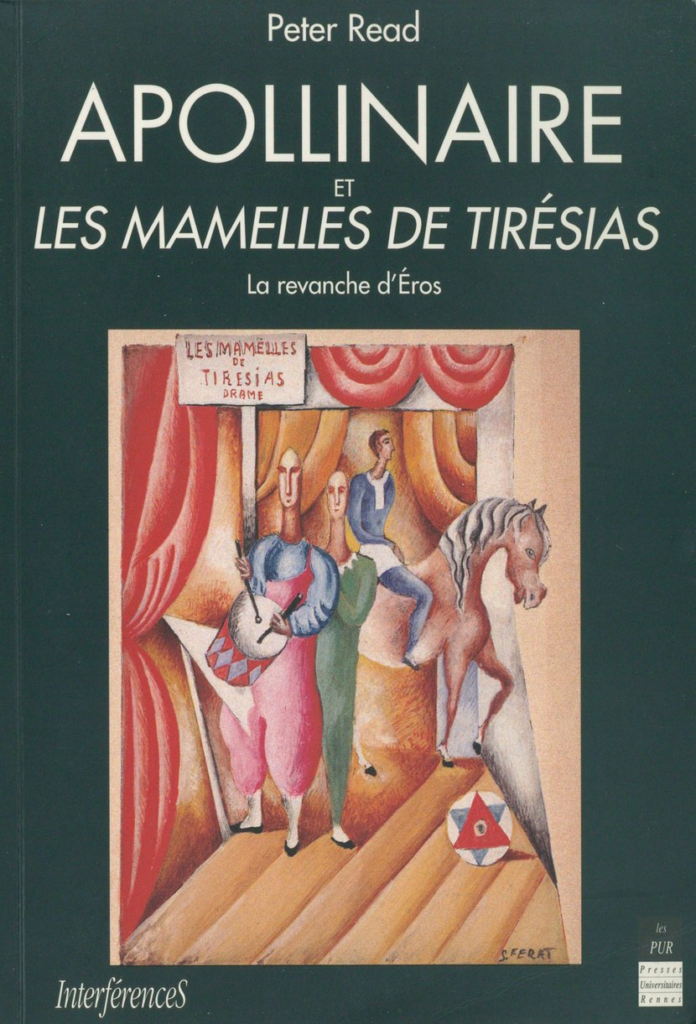

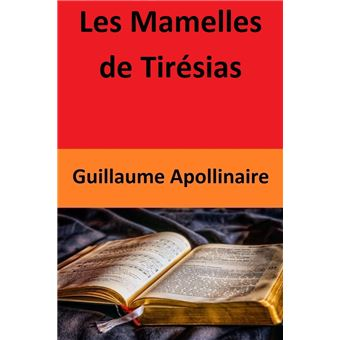

On 24 June 1917, while on leave, he attended the premiere of Guillaume Apollinaire’s play, Les Mamelles de Tirésias (“The breasts of Tirésias“), subtitled surrealist drama.

The show turned into a fiasco.

In December 1916, the poet Pierre Albert-Birot asked Apollinaire to write a play that would be in the theatre, “what they do on all other levels of art.”

Above: French poet Pierre Albert-Birot (1876 – 1967)

The latter accepted, wishing to develop an idea that had been his in draft form since 1903:

A woman decides to change gender, and her breasts represented by balloons fly away from her bodice.

Apollinaire set to work, writing and rewriting his play.

He profoundly modified his text over the course of the rehearsals, depending on their effect, as Albert-Birot testifies:

“Apollinaire understood more and more clearly that theatre is poetry that is seen.“

Apollinaire was inspired by the myth of the blind soothsayer of Thebes, Tirésias, while applying modern and provocative themes: feminism and anti-militarism, perhaps themselves mocked.

Above: Relief of Ulysses consulting Tirésias

The story is based on that of Tirésias, who undergoes a gender transition to gain power among men.

Her goal is to change customs, rejecting the past to establish gender equality.

The conclusion of the play nevertheless sees her accept the role of procreator that they want to assign to her and puts an end to the carnivalesque reversal.

The play was written during the First World War, a period when women were doing jobs traditionally done by men, the latter having gone to the Front.

Above: Rosie the Riveter

The first presentation took place on 24 June 1917 at the Conservatoire Renée Maubel, rue de l’Orient, Paris, in a staging by Pierre Albert-Birot.

Above: Théâtre Montmartre Galabru, Paris, France

In the idea of abandoning referential realism, masks were used.

The work was created under uncertain conditions.

With the exception of Louise Marion, all the actors were young beginners making their first appearance on a theatre stage.

Herrand also nearly withdrew five days before the performance, following the death of his father.

Due to the war context, the budget was reduced:

The set was made of paper.

Thérèse’s breasts flying away were to be represented by helium -filled balloons, but since the gas was reserved for the army, bales of pressed fabric were used.

A single pianist was responsible for the music and the sound effects.

Apollinaire announced that the music initially written for an orchestra had to be reduced, but there is no evidence that such a version of Germaine Albert-Birot’s music existed.

Above: Interior of the Théâtre Montmartre Galabru

This premiere took place in front of a packed house.

“A large number of advertisements in the newspapers” attracted “a good part of the artistic world and the Parisian press critics.”

The evening had a taste of a Dada evening:

First of all, through the passionate reactions, the show was as much on stage as in the audience, the latter having been excited by a “crush to get in” and several hours of delay, the sets not being finished.

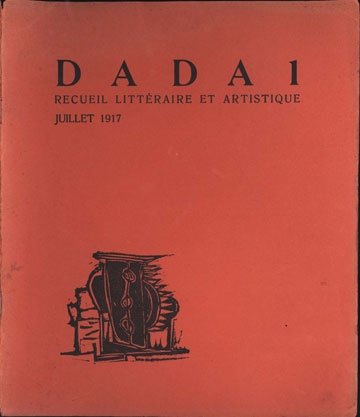

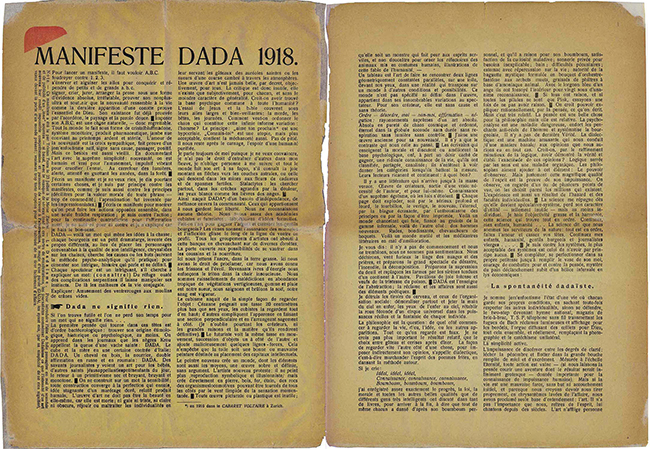

(Dada or Dadaism was an anti-establishment art movement that developed in 1915 in the context of the Great War and the earlier anti-art movement.

Above: Cover of the 1st edition of the publication Dada, Zürich, 1917

Early centers for dadaism included Zürich and Berlin.

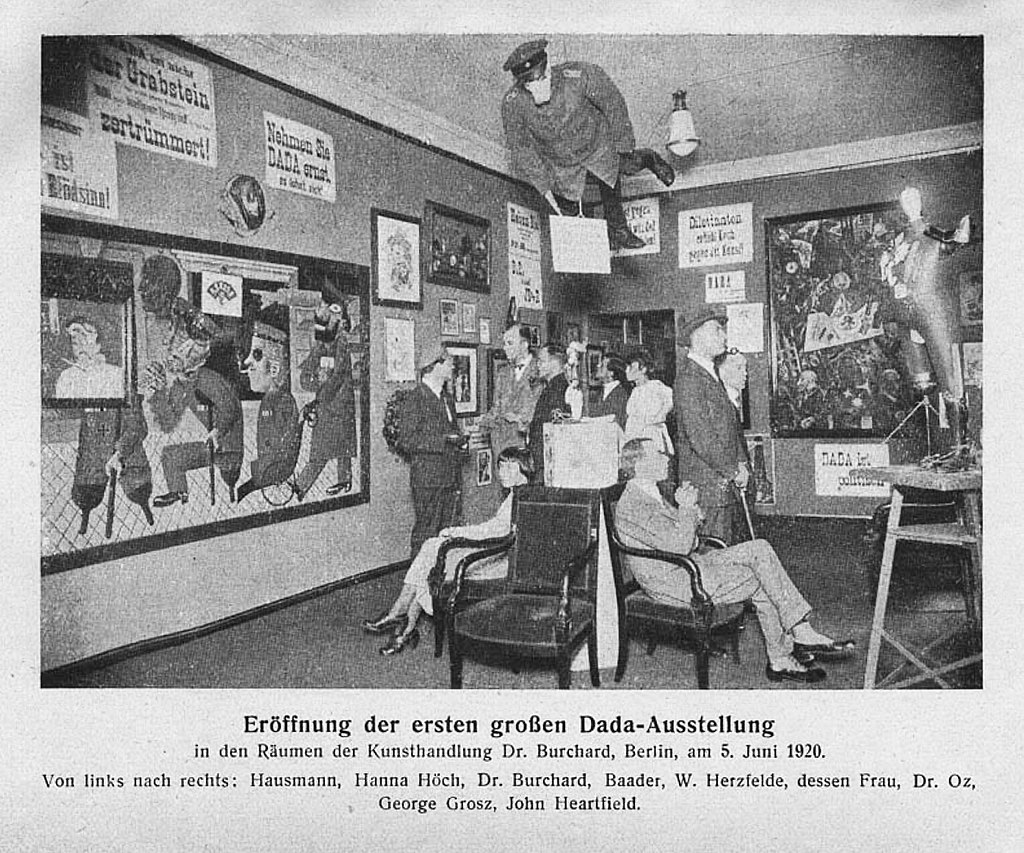

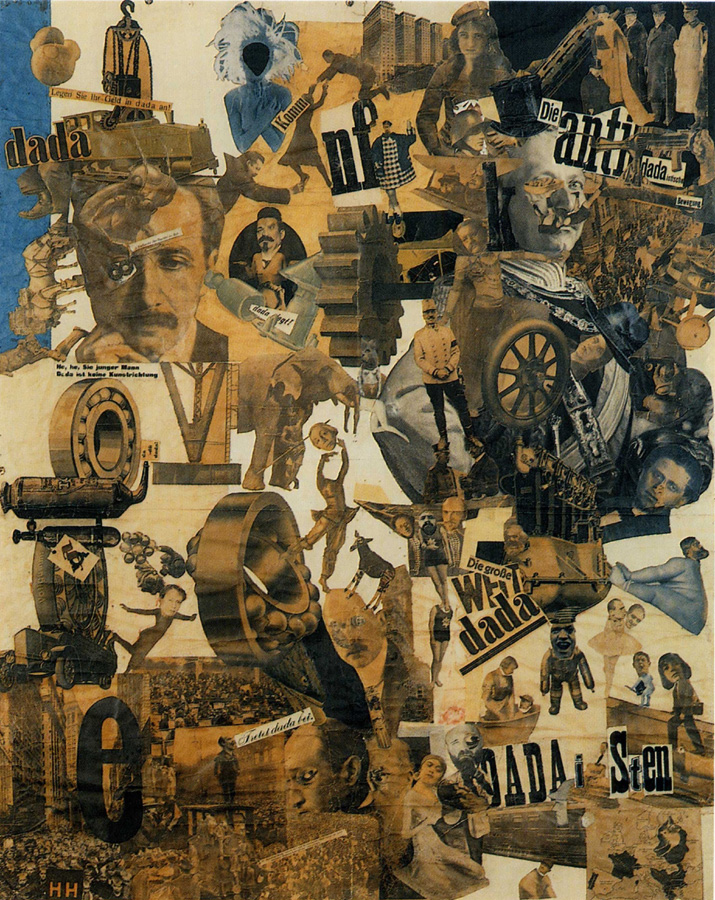

Above: Grand opening of the first Dada exhibition, Berlin, 5 June 1920

Within a few years, the movement had spread to New York City and a variety of artistic centers in Europe and Asia.

Within the umbrella of the movement, people used a wide variety of artistic forms to protest the logic, reason and aestheticism of modern capitalism and modern war.

To develop their protest, artists tended to make use of nonsense, irrationality, and an anti-bourgeois sensibility.

The art of the movement began primarily as performance art, but eventually spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound poetry, cut-up writing, and sculpture.

Above: Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Epoch of Weimar Beer-Belly Culture in Germany, 1919

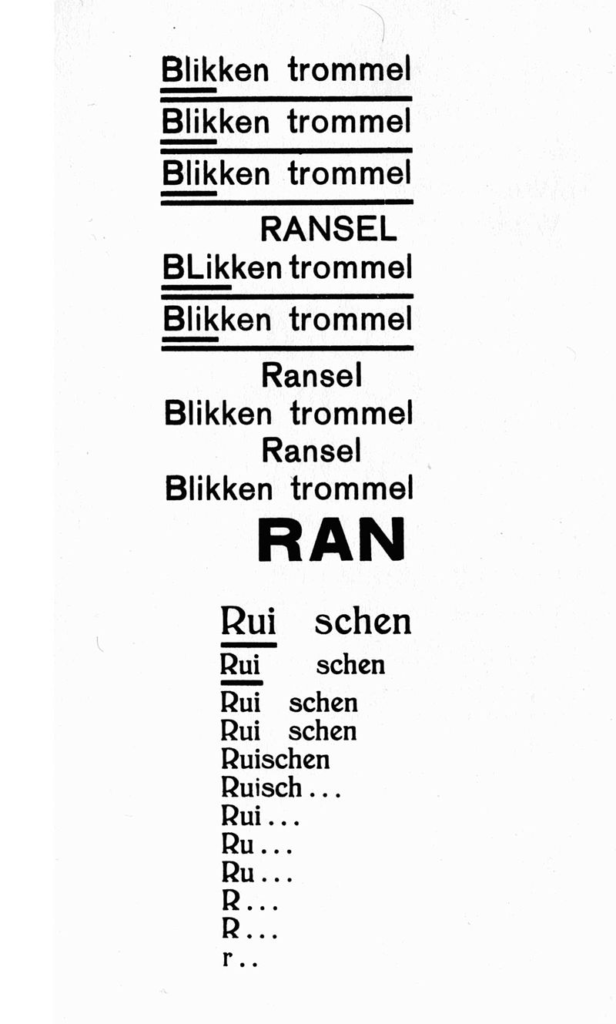

Above: Bonset sound-poem, “Passing troop“, 1916

TO MAKE A DADAIST POEM

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are – an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

Tristan Tzara

Above: Romanian artist Tristan Tzara (1896 – 1963)

Dadaist artists expressed their discontent toward violence, war, and nationalism and maintained political affinities with radical politics on the left-wing and far-left politics.

The movement had no shared artistic style, although most artists had shown interest in the machine aesthetic (art that draws inspiration from industrialization).

There is no consensus on the origin of the movement’s name.

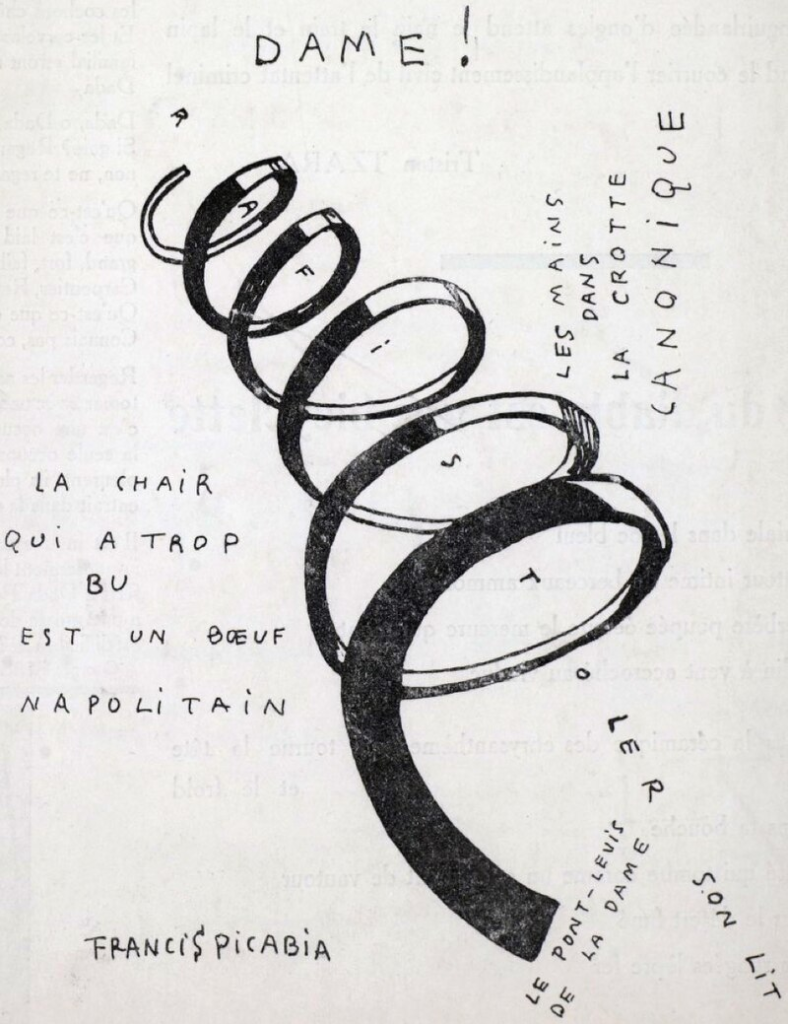

Above: Francis Picabia, Dame! Illustration for the cover of the periodical Dadaphone, n. 7, Paris, March 1920

A common story is that the artist Richard Huelsenbeck slid a paper knife randomly into a dictionary, where it landed on “dada“, a French term for a hobby horse.

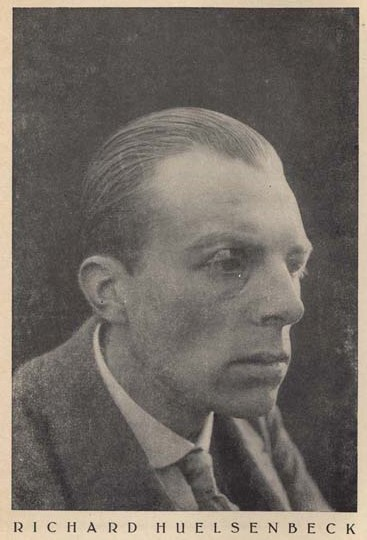

Above: German artist Richard Huelsenbeck (1892 – 1974)

Others note it suggests the first words of a child, evoking a childishness and absurdity that appealed to the group.

Above: Child with a hobby-horse

Still others speculate it might have been chosen to evoke a similar meaning (or no meaning at all) in any language, reflecting the movement’s internationalism.

The roots of Dada lie in pre-war avant-garde.

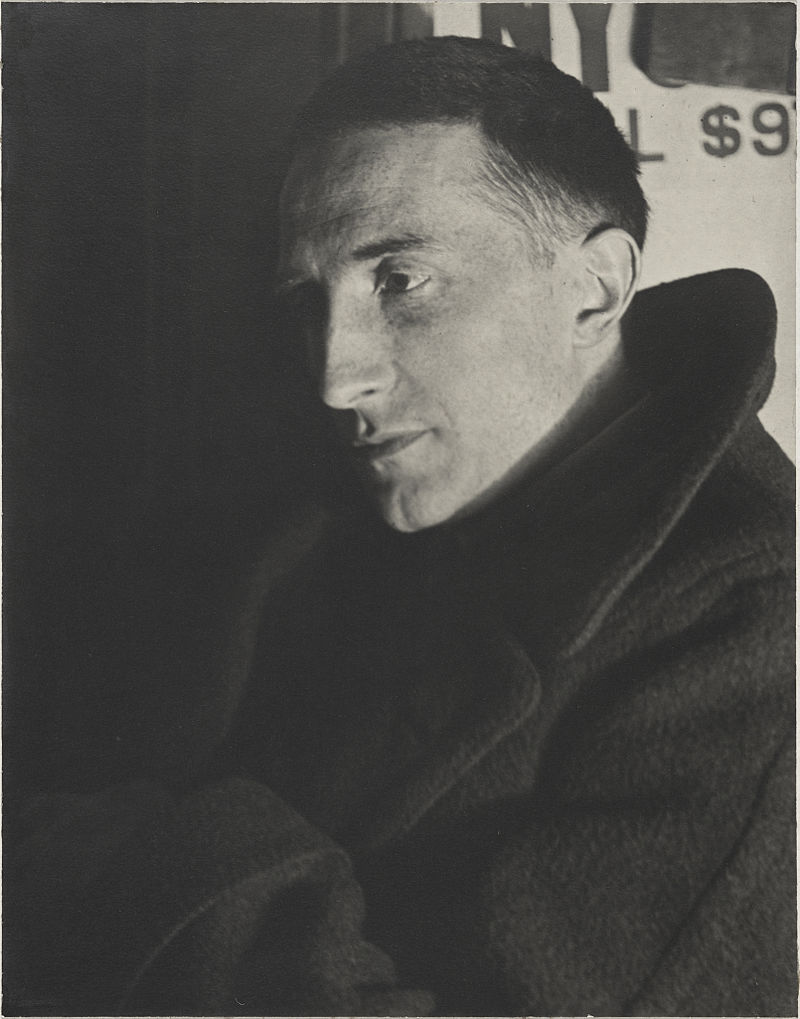

The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 to characterize works that challenge accepted definitions of art.

Above: French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968)

Cubism and the development of collage and abstract art would inform the movement’s detachment from the constraints of reality and convention.

Above: Girl with a Mandolin, Pablo Picasso (1910)

The work of French poets, Italian Futurists, and German Expressionists would influence Dada’s rejection of the correlation between words and meaning.

(Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century.

It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city.)

Above: Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, Gino Severini (1912)

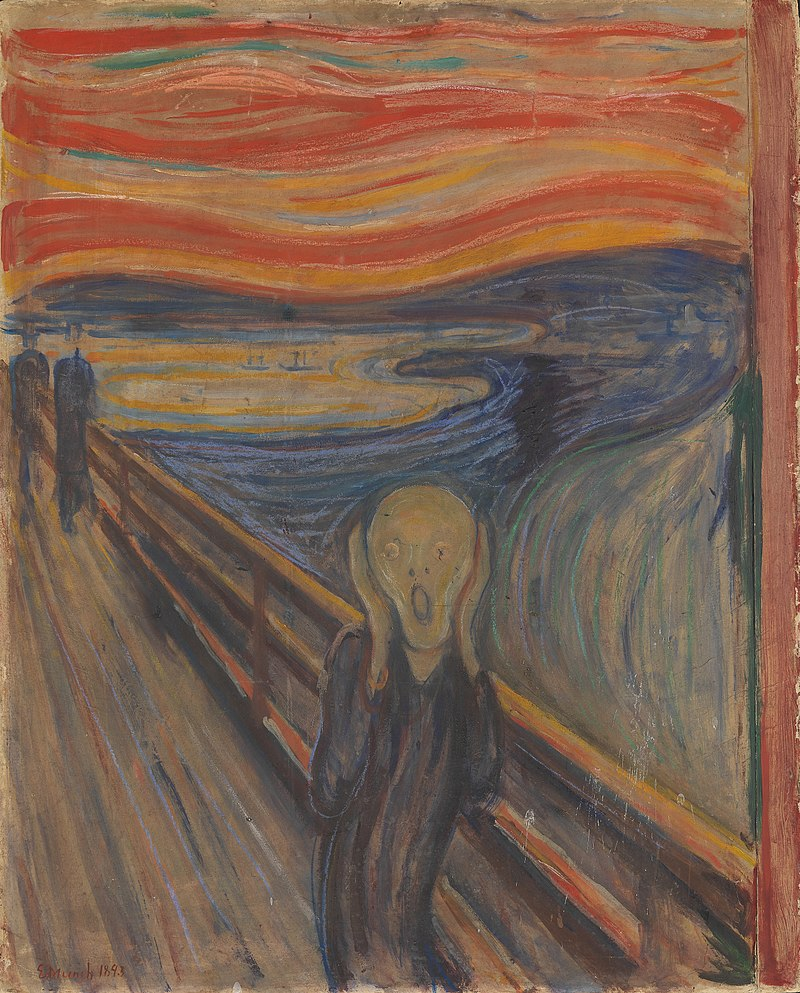

(Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century.

Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas.

Expressionist artists have sought to express the meaning of emotional experience rather than physical reality.)

Above: The Scream, Edvard Munch (1893)

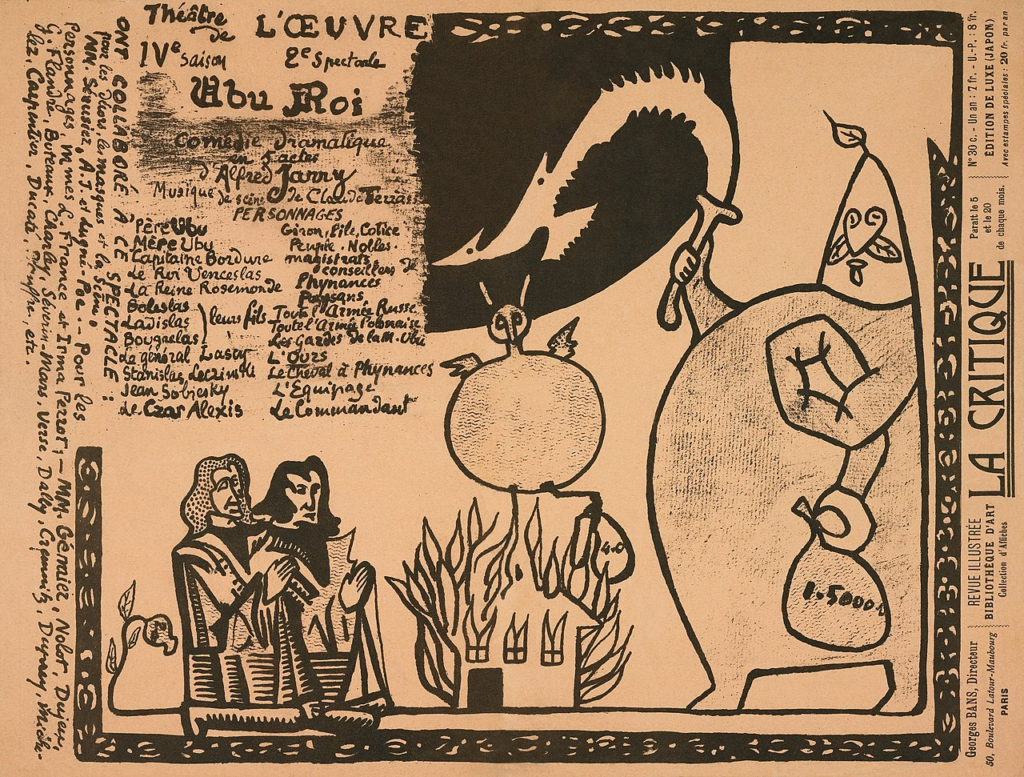

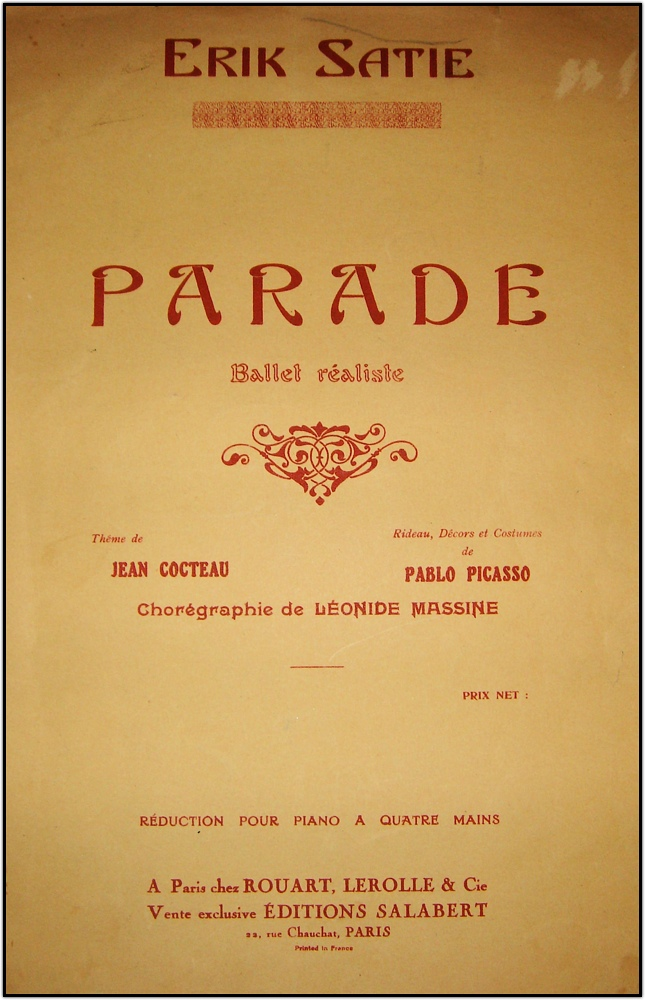

Works such as Ubu Roi (1896) by Alfred Jarry and the ballet Parade (1917) by Erik Satie would be characterized as proto-Dadaist works.

Above: Programme for the première of Ubu Roi (1896)

(Ubu Roi (French: “Ubu the King“) is a play by French writer Alfred Jarry, then 23 years old.

It was first performed in Paris in 1896, by Aurélien Lugné-Poe’s Théâtre de l’Œuvre at the Nouveau-Théâtre (today, the Théâtre de Paris).

The production’s single public performance baffled and offended audiences with its unruliness and obscenity.

Considered to be a wild, bizarre and comic play, significant for the way it overturns cultural rules, norms and conventions, it is seen by 20th- and 21st-century scholars to have opened the door for what became known as modernism in the 20th century.)

Above: Parade (1917)

(The poet Guillaume Apollinaire described Parade as “a kind of surrealism” (une sorte de surréalisme) when he wrote the program note in 1917, thus coining the word three years before Surrealism emerged as an art movement in Paris.

The ballet was remarkable for several reasons.

It was the first collaboration between Satie and Picasso, and also the first time either of them had worked on a ballet, thus making it the first time either collaborated with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.

The plot of Parade incorporated and was inspired by popular entertainments of the period, such as Parisian music halls and American silent films.

Much of the settings used in Parade‘s plot occurred outside of the formal Parisian theater, depicting the streets of Paris.

The plot reproduces various elements of everyday life such as the music hall and fairground.

Before Parade, the use of popular entertainment materials was considered unsuitable for the elite world of the ballet.

The plot of Parade composed by Cocteau includes the failed attempt of a troupe of performers to attract audience members to view their show.

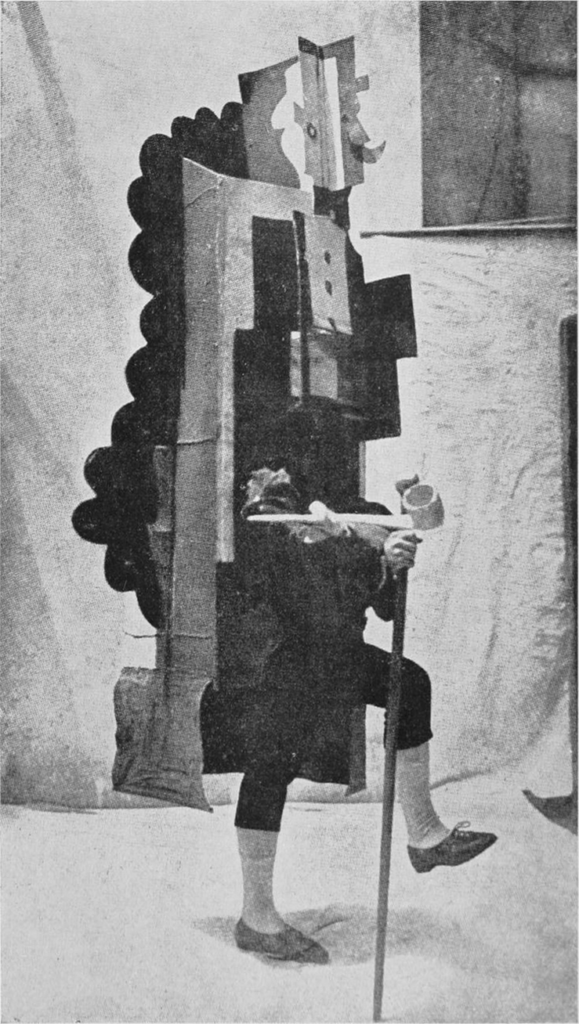

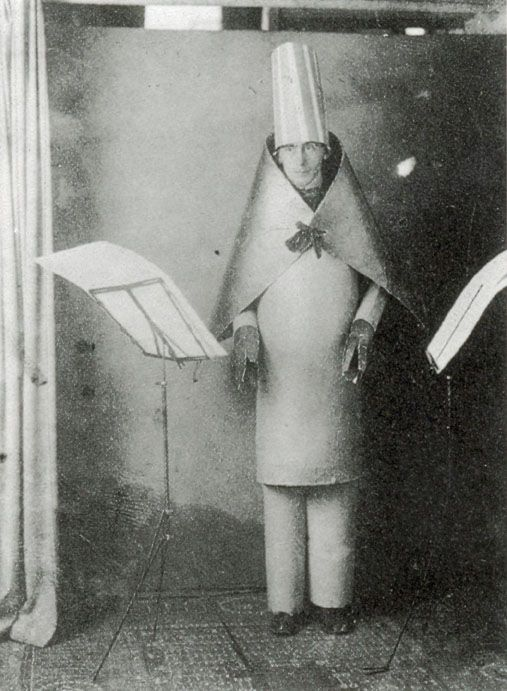

Some of Picasso’s Cubist costumes were in solid cardboard, allowing the dancers only a minimum of movement.

Above: Picasso costume design for Parade

The score contained several “noise-making” instruments (typewriter, foghorn, an assortment of milk bottles, pistol, and so on), which had been added by Cocteau (somewhat to the dismay of Satie).

It is supposed that such additions by Cocteau showed his eagerness to create a succès de scandale.

Although Parade was quite revolutionary, bringing common street entertainments to the elite, being scorned by audiences and being praised by critics, nonetheless many years later Stravinsky could still pride himself in never having been topped in the matter of succès de scandale.

The ragtime contained in Parade would later be adapted for piano solo and attained considerable success as a separate piano piece.

The finale is “a rapid ragtime dance in which the whole cast makes a last desperate attempt to lure the audience in to see their show“.

The premiere of the ballet resulted in a number of scandals.

One faction of the audience booed, hissed, and was very unruly, nearly causing a riot before they were drowned out by enthusiastic applause.

Many of their objections were focused on Picasso’s cubist design, which was met with cries of “sale boche“.

According to the painter Gabriel Fournier, one of the most memorable scandals was an altercation between Cocteau, Satie, and music critic Jean Poueigh, who gave Parade an unfavorable review.

Satie had written a postcard to the critic which read:

“Monsieur et cher ami – vous êtes un cul, un cul sans musique! Signé Erik Satie“.

(“Sir and dear friend – you are an arse, an arse without music! Signed, Erik Satie.“).

The critic sued Satie.

At the trial, Cocteau was arrested and beaten by police for repeatedly yelling “arse” in the courtroom.

Satie was given a sentence of eight days in jail.)

The Dada movement’s principles were first collected in Hugo Ball’s Dada Manifesto in 1918.

Ball is seen as the founder of the Dada movement.)

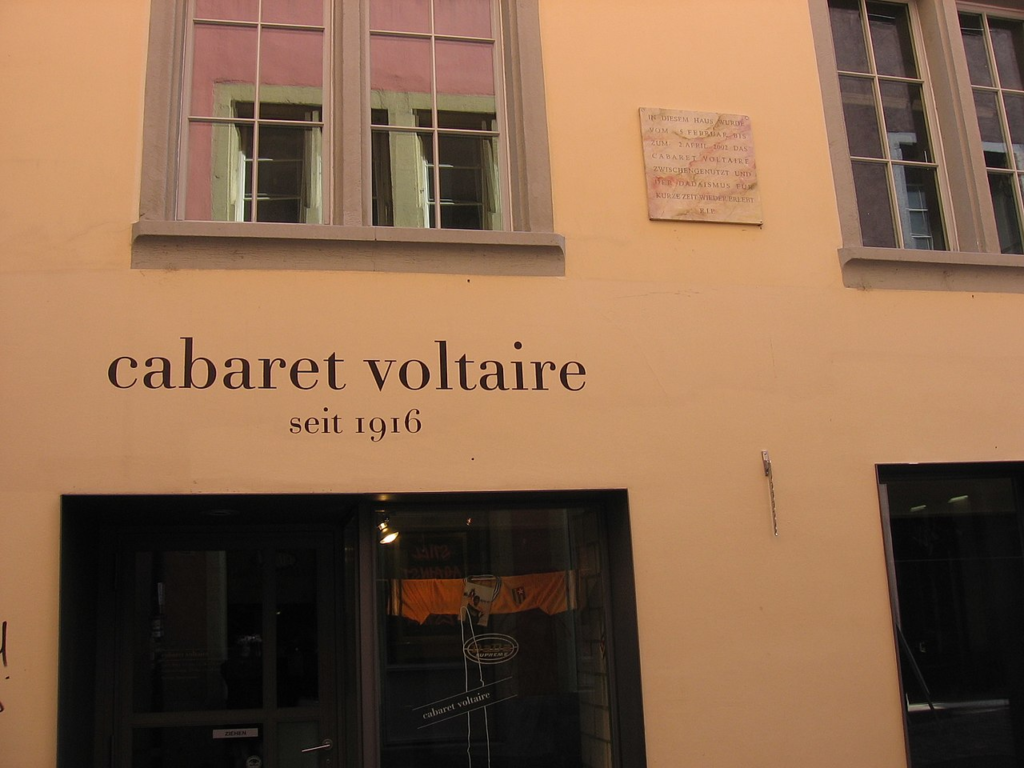

Above: German writer Hugo Ball (1886 – 1927), Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich, Switzerland, 1916

Above: Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich, Switerland

“We piled in like the ingredients of a bomb.

At that time, politics was that of letters.

Everything became passionate, explosive for us.”

Jean Cocteau

Above: French poet Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963)

The spectators reacted to the play in a stormy and contrasting manner, with both boos and applause.

“The journalists cry scandal.

The play ends in an indescribable hubbub.”

Apollinaire appeared on stage and shouts to the audience “Pigs!“.

The play attracted the wrath of the press, which raged as much against Apollinaire as against Albert-Birot.

“This joke might have seemed funny, told on a Tuesday by the unctuous and mocking Apollinaire, or performed by Max Jacob in a workshop on the Left Bank, but to call it a surrealist drama and present it seriously to the public is, frankly, improper.

The play was performed by people whose profession it was clearly not.

The sets, it is said, cost the organizers seven francs.

They were stolen.”

L’Heure, 26 June 1917

The young Louis Aragon, on the other hand, pressed by Albert-Birot, gave a glowing report in SIC.

Above: French writer Louis Aragon (1897 – 1982)

Above: Logo for SIC (Sons Idées Couleurs, Formes), a Parisian avant-garde magazine published from 1916 to 1919 under the direction of the poet Pierre Albert-Birot.

Initially written entirely without an author’s name by the latter and his wife Germaine, it was open to avant-garde circles and was also the second Parisian magazine, after Nord-Sud, to distribute, without affiliating itself with the movement, the texts of the

Zürich Dadaists, namely those of Tristan Tzara.

At the end of its publication, it had 54 issues divided into 41 deliveries.

Some articles saw the play as an anti-feminist satire.

“It is a satire against feminism or rather against the excesses of feminism.

Women may well take the oranges off their bodices, but they remain women nonetheless, and at the first opportune opportunity, they put them back on.”

Victor Basch, Le Pays

Above: Hungarian-French philosopher Victor Basch (1863 – 1944)

“This buffoonery is not devoid, as we can see, of philosophical and satirical meaning.

It is even very topical, given the ambitions of these ladies who will not be content with being municipal councilors.

And this makes us think of Aristophanes’ Assembly of Women.”

Guillot de Saix, La France (1862 – 1884)

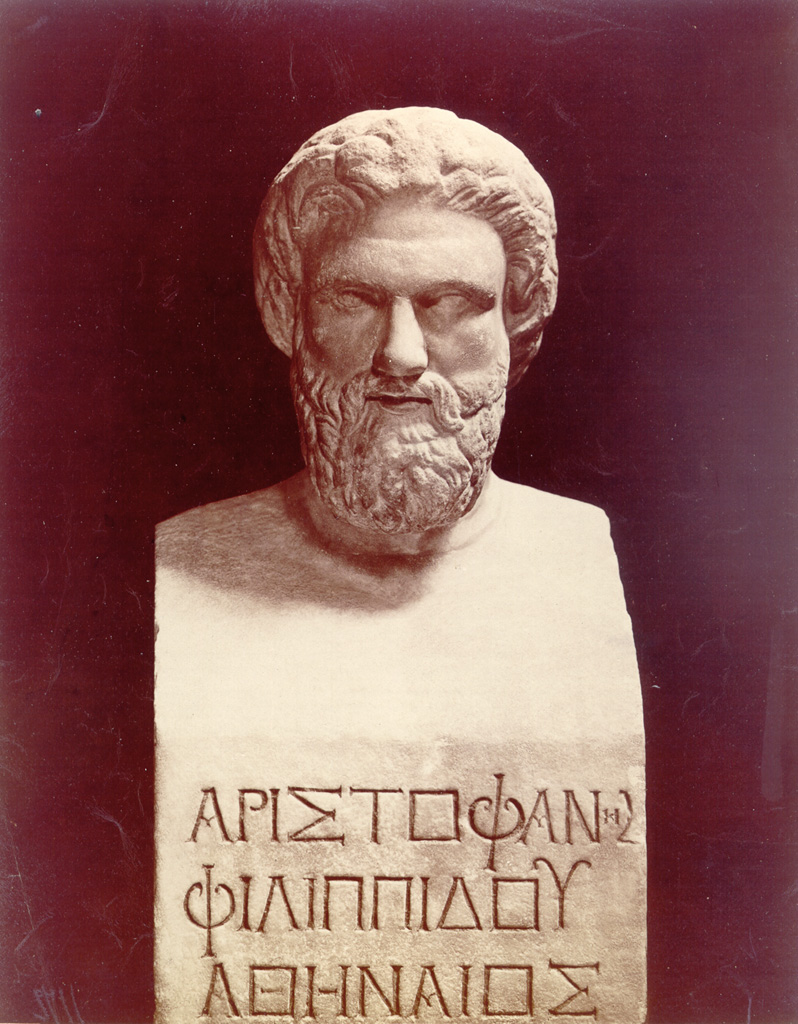

(The Assembly of Women is an ancient Greek comedy by

Aristophanes composed around 392 BC.

The Athenian women, at the instigation of one of their own, Praxagora, gather at dawn in the agora to take the necessary measures in place of the men to save the city.

When Athenians wake up the next day, they are astonished to discover the reforms that the women intend to adopt: pooling of property, the right for the ugliest and oldest women to choose a companion.

In the evening, a grand banquet celebrates the establishment of the new order of things, and the play ends in a truly Dionysian atmosphere.

By staging the debates of the Athenian women, which are laughable for their lack of political scope, but also for their lack of practical sense and the immoderate defense of particular interests that appears there, it is the constitutional projects that animate the Athens of his time that Aristophanes intends to ridicule.

We also observe in this play the disillusionment of the great comic poet, whose bitterness only increases after the capitulation of Athens which ended the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC, as well as in the face of the degradation of Athenian political institutions, which led to the reestablishment of tyranny in 411 and again in 404.)

Above: Bust of Greek playwright Aristophanes (445 – 375 BC)

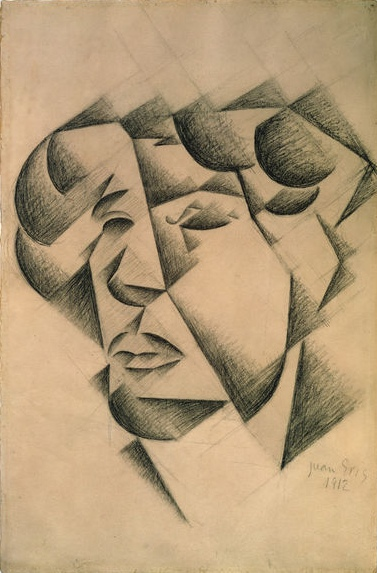

Les Mamelles de Tirésias also caused several Cubists to distance themselves from Apollinaire, “who saw in Férat’s decorations a fanciful and silly trivialization of their painting.”

Above: Self-portrait (1912) of Cubist artist Juan Gris (1887 – 1927)

Disguised as an English officer, revolver in hand, Vaché ordered the performance to be stopped, which he found too artistic for his taste, under threat of using his weapon against the audience.

Breton managed to calm him down.

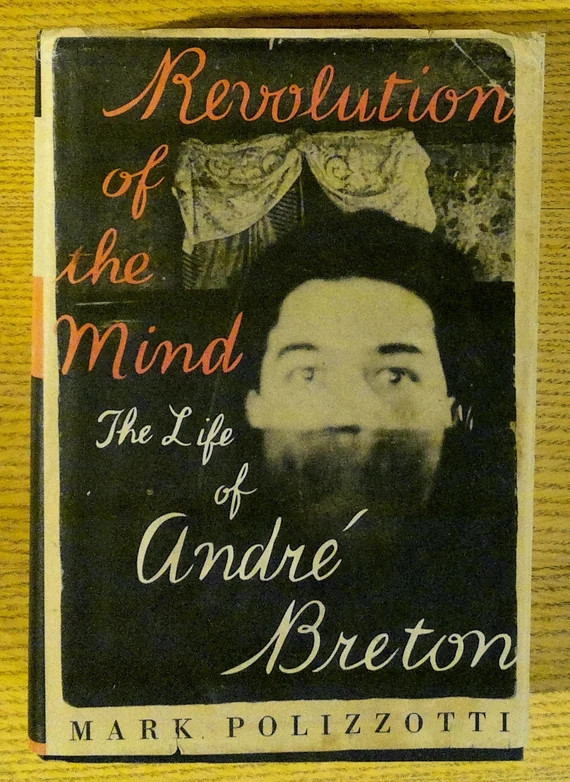

However, in his biography of Breton, Mark Polizzotti doubts the veracity of this fact.

He notes that out of about 20 reports of this show, none mention Vaché’s “spectacular” reaction.

Only Louis Aragon “testified” to this incident although he was not present.

On 18 August 1917, Vaché wrote to André Breton:

“Art is stupidity.

Almost nothing is stupidity.

Art must be a funny and somewhat boring thing – that’s all.

Besides…

Art does not exist, no doubt.

It is therefore useless to sing about it – however:

We make art – because that’s how it is and not otherwise.

Well – what do you want to do about it?”

Above: Jacques Vaché

In his last letter of 19 December 1918, to Breton, he wrote:

“I rely on you to prepare the ways of this disappointing God, a little sneering, and terrible in any case.

How funny it will be, you see, this true NEW SPIRIT is unleashed.”

Above: Jacques Vaché

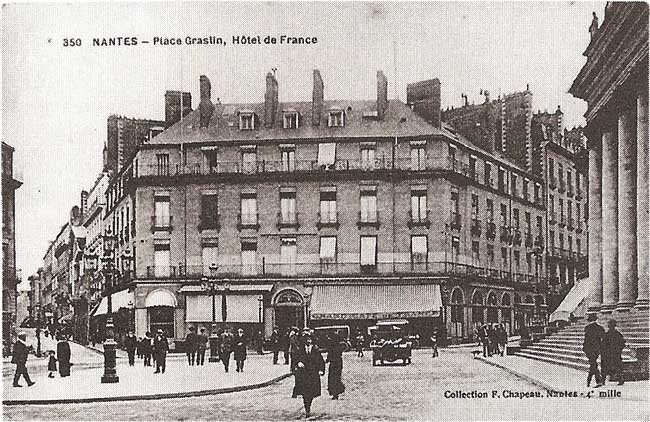

On 6 January 1919, Jacques Vaché and a friend, Paul Bonnet, were found dead in a room at the Hôtel de France, Place Graslin in Nantes.

An opium addict, he succumbed to an overdose.

Accidental death or suicide?

His surrealist friends were inclined to believe it was an intentional act.

Above: Opium pipe

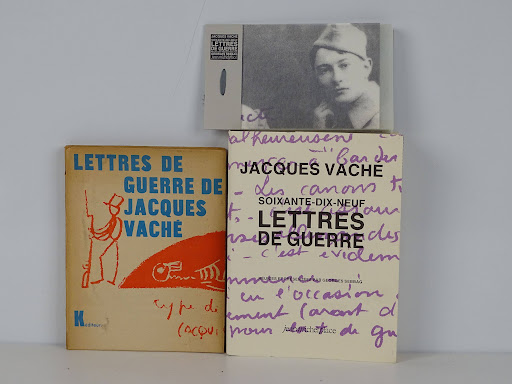

In 1920, André Breton published his Lettres de guerre , prefacing them with the words:

“Jacques Vaché, the man I loved the most and who undoubtedly had the greatest and most definitive influence on me.“

A member of the Nantes group, Jacques Vaché astonishes with his style:

He cultivates a form of dandyism, cross-dressing, changing his name, living in a common-law relationship even before he was 20.

Even more than his remarkable originality, Jacques Vaché embodies in André Breton’s eyes the free spirit dear to the surrealist.

The following day, the newspaper Le Télégramme des provinces de l’Ouest reported the events.

It announced the discovery of the naked bodies of the two young men, lying on a bed in a room at the hotel.

They had apparently succumbed to taking too much opium.

A third man, an American soldier named AK Woynow, had tried to find help but it was already too late.

The two victims were presented as “young fools” with no experience of drugs, as well as “brave soldiers who had done their duty in front of the enemy and had been wounded“.

To preserve the honor of the families, only their first names and the initial of their surname were mentioned.

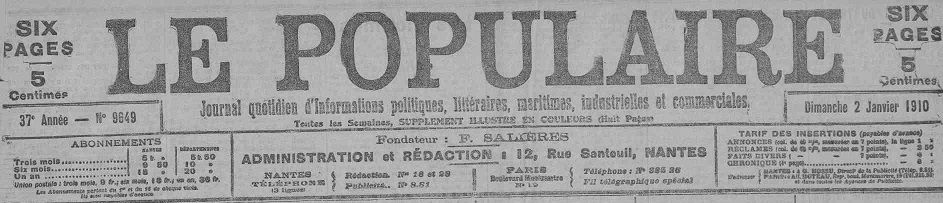

Another Nantes newspaper, Le Populaire, stated in its edition of January 9 that the opium had been supplied by Vaché, and cites the testimony of his father, who says he “saw a covered and tied earthenware pot” which he took for a jam jar.

What the newspapers do not report is the presence in the room of two other people:

- André Caron, a member of the Nantes group

- a man named Maillocheau, who they had met on the evening of the 5th to celebrate their upcoming demobilization.

Once in the hotel room, Vaché took out an earthenware pot containing opium, which they made into balls that they swallowed.

Maillocheau, who was not interested in drugs, left.

Later, Caron, who had become ill, returned home.

At dawn on the 6th, Vaché and Paul Bonnet undressed, carefully folded their clothes, settled down on the bed and had a few more balls of opium.

Woynow, who had also had a little more opium, fell asleep on the couch.

When he woke up in the evening, he found his two comrades still lying there motionless, barely breathing.

He ran to get the hotel doctor.

In August 1919, Breton published the 15 letters from Vaché sent to his surrealist friends during the war under the title of Lettres de guerre.

André Breton only learned of his friend’s death between 1300 and 1400 hours on 22 January.

The dismay and the lack of details regarding the circumstances of the death lead him to think that it could be an assassination.

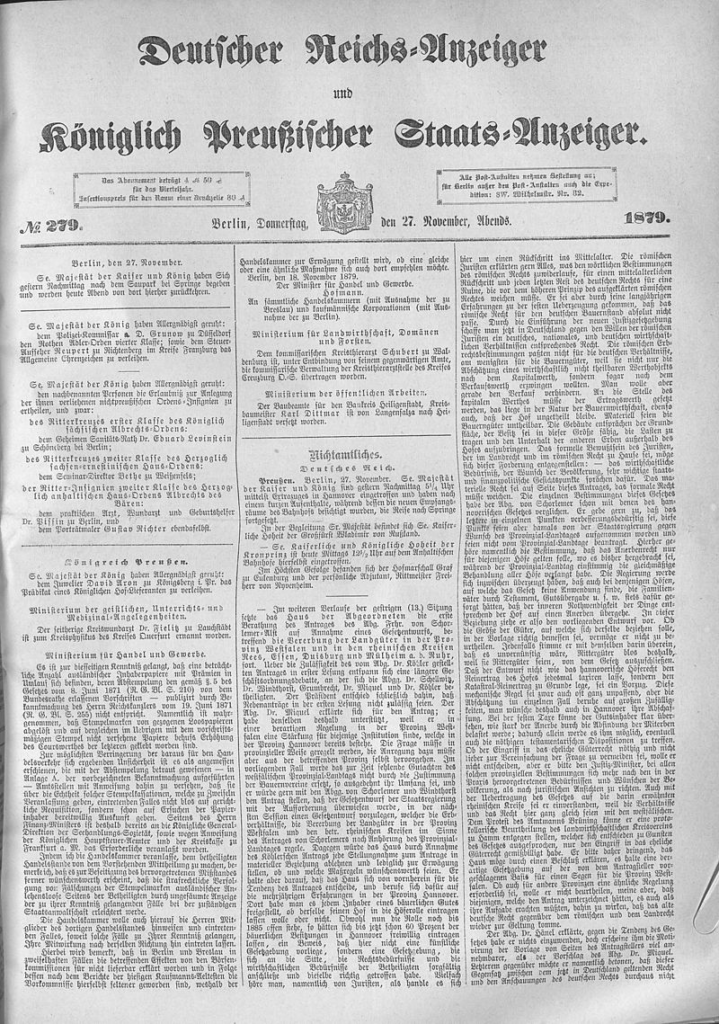

In a letter addressed to Fraenkel, on 30 January, he inserts a newspaper clipping which associates the murder of Jean Jaurès, on 31 July 1914, to that of Karl Liebknecht, on 16 January 1919.

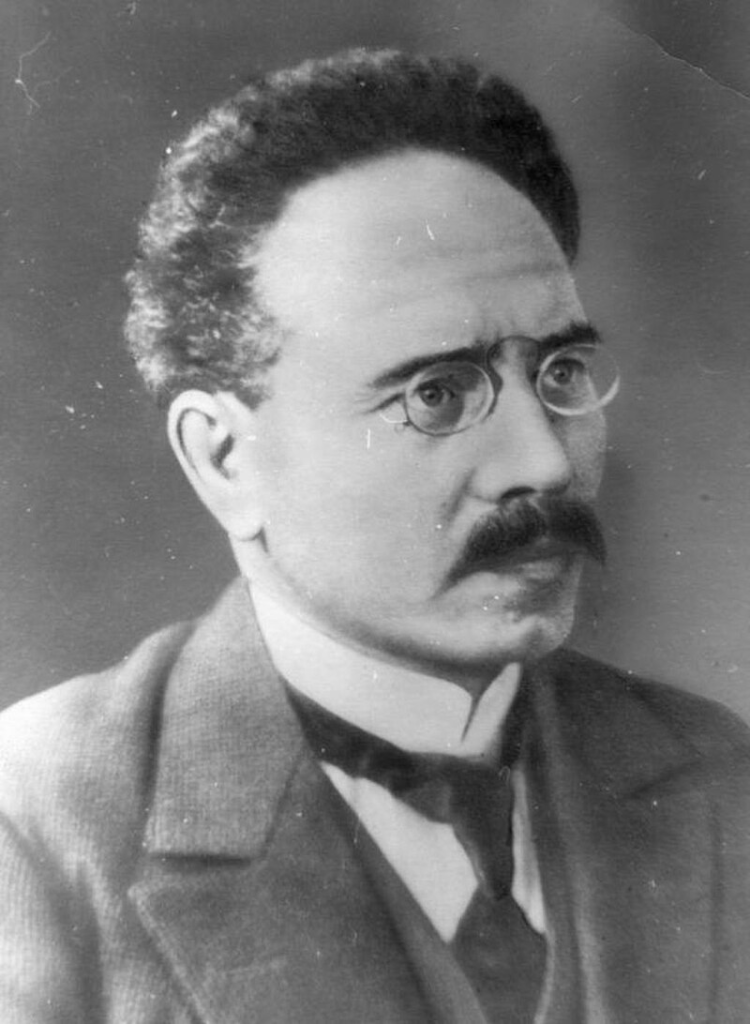

Above: French journalist/politician Jean Jaurès (1859 – 1914)

On 31 July 1914, Jaurès was assassinated.

At 9 pm, he went to dine at the Café du Croissant on Rue Montmartre, Paris.

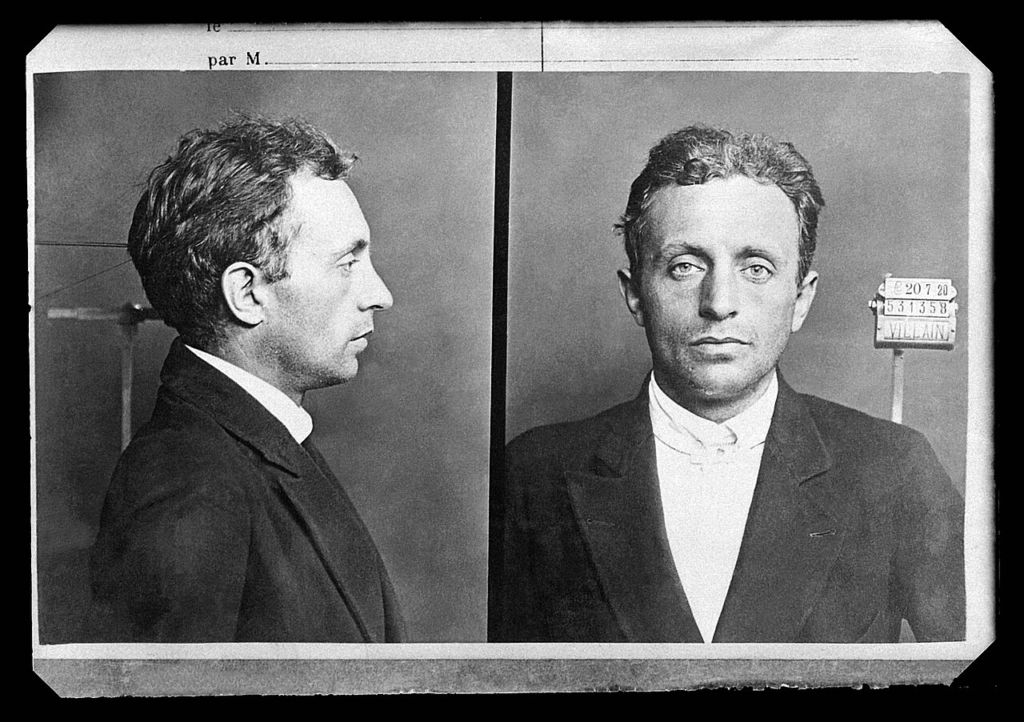

Forty minutes later, Raoul Villain, a 29-year-old French nationalist, walked up to the restaurant window and fired two shots into Jaurès’s back.

He died five minutes later at 9:45 pm.

Jaurès had been due to attend an international conference on 9 August, in an attempt to dissuade the belligerent parties from going ahead with the war.

Villain also intended to murder Henriette Caillaux with his two engraved pistols.

Above: French Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux’s wife Henriette Caillaux (1874 – 1943)

Irony: On 16 March 1914, she shot and killed Gaston Calmette, editor of the newspaper Le Figaro.

Tried after World War I and acquitted, Villain was later killed by the Republicans in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War.

Above: Mugshot of Raoul Villain (1885 – 1936)

Shock waves ran through the streets of Paris.

One of the government’s most charismatic and compelling orators had been assassinated.

His opponent, President Poincaré, sent his sympathies to Jaurès’s widow.

Above: French President Raymond Poincaré (1860 – 1934)

Paris was on the brink of revolution:

Jaurès had been advocating a general strike and had narrowly avoided sedition charges.

One important consequence was that the cabinet postponed the arrest of socialist revolutionaries.

French Prime Minister René Viviani reassured Britain of Belgian neutrality but also said that.

“The gloves were off.“

Above: French Prime Minister René Viviani (1863 – 1925)

Jaurès’s murder brought matters one step closer to world war.

It helped to destabilize the French government, whilst simultaneously breaking a link in the chain of international solidarity.

Speaking at Jaurès’s funeral a few days later, CGT (General Confederation of Labor) trade union leader Léon Jouhaux declared:

“All working men, we take the field with the determination to drive back the aggressor.”

As if in reverence to his memory, the Socialists in the Chamber agreed to suspend all sabotage activity in support of the Union Sacrée (a political truce in which the left-wing agreed during World War I not to oppose the government or call any strikes).