“O call back yesterday, bid time return.“

William Shakespeare, Richard II

Tuesday 11 March 2025

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

The fog drifts over the Bodensee (Lake Constance) like a whispered secret, delicate as breath on glass.

It moves with the hush of something ancient, curling in tendrils over the water’s surface, dissolving as it meets the silent shore.

The trees stand as shadows beyond its veil, softened, distant, as if the world beyond the lake has been swallowed into dream.

For a time, the water and sky are one — an endless silver hush, unbroken but for the occasional ripple of something unseen beneath.

The air carries the scent of damp earth and the faint chill of morning, wrapping itself around the solitude like a quiet prayer.

Nothing stirs, yet everything shifts.

The fog thickens, thins, drifts on, unmoored.

It caresses the lake like silk on skin, then releases it, vanishing into the rising light.

A moment of mystery, fleeting and eternal all at once.

“I am not a writer.

The mere sight of a blank sheet of paper gnaws at my soul.

The kind of physical contemplation that such work imposes on me is so odious to me that I avoid it as much as I can.“

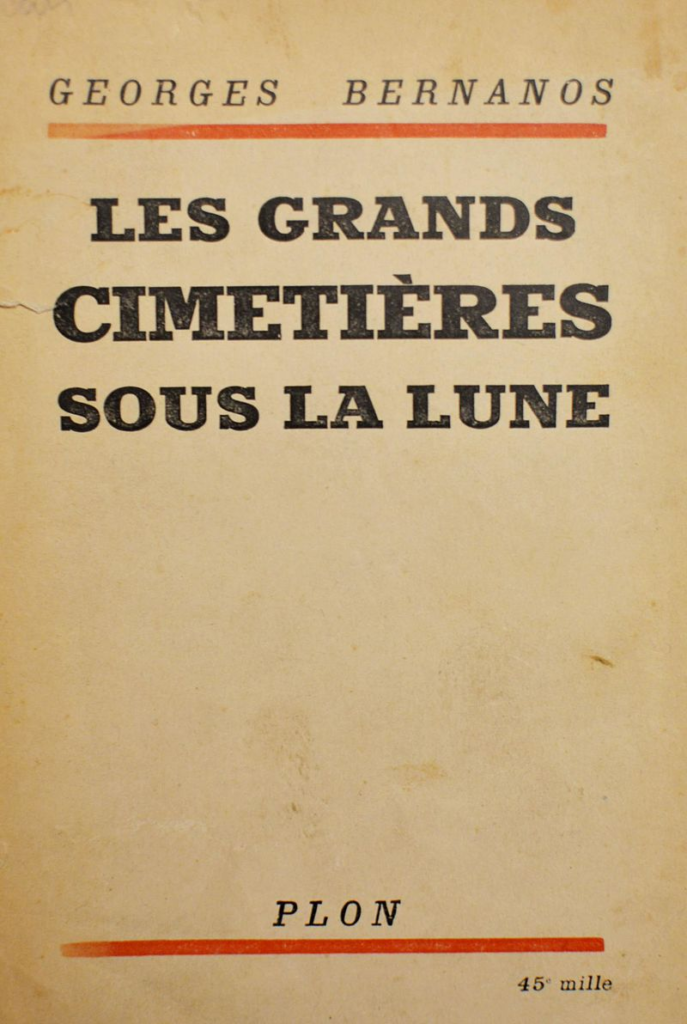

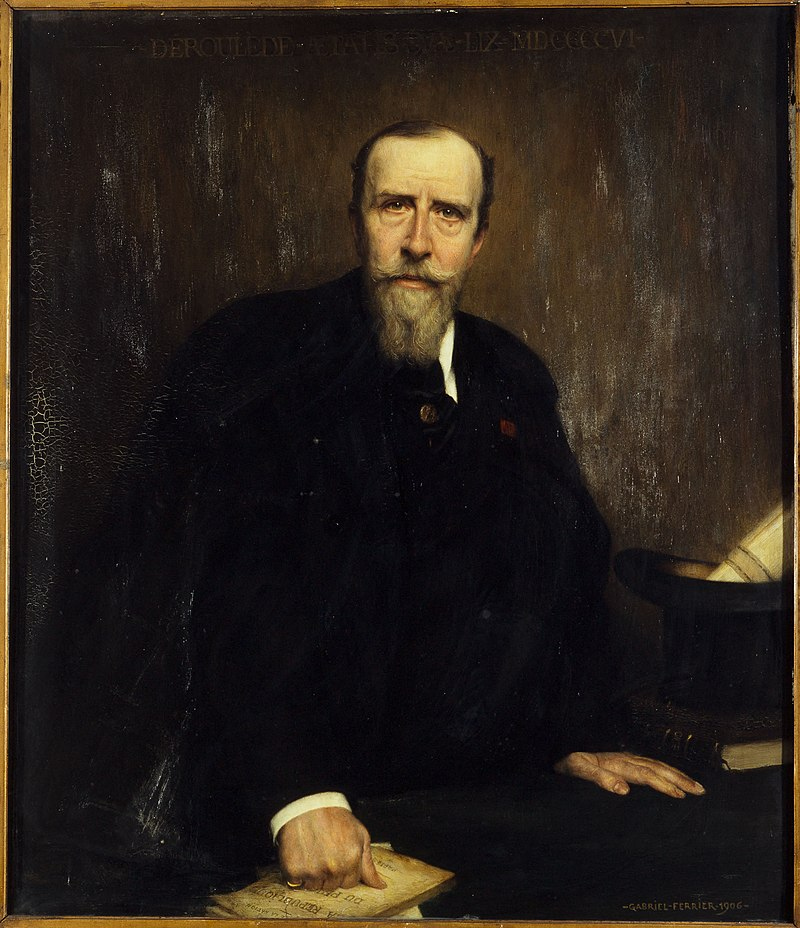

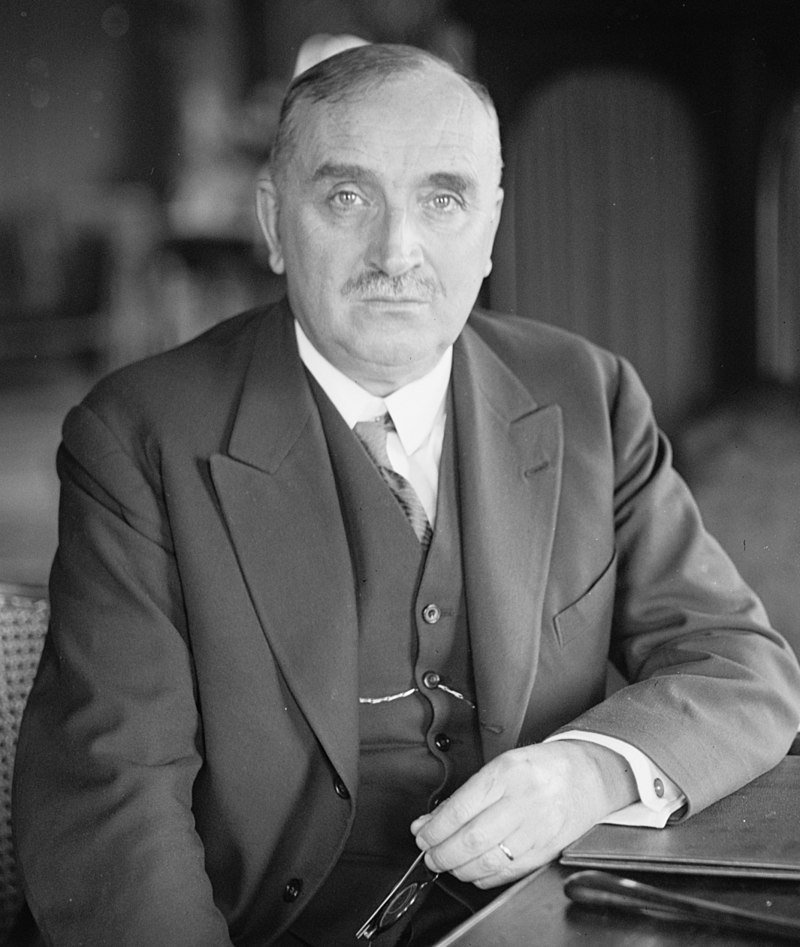

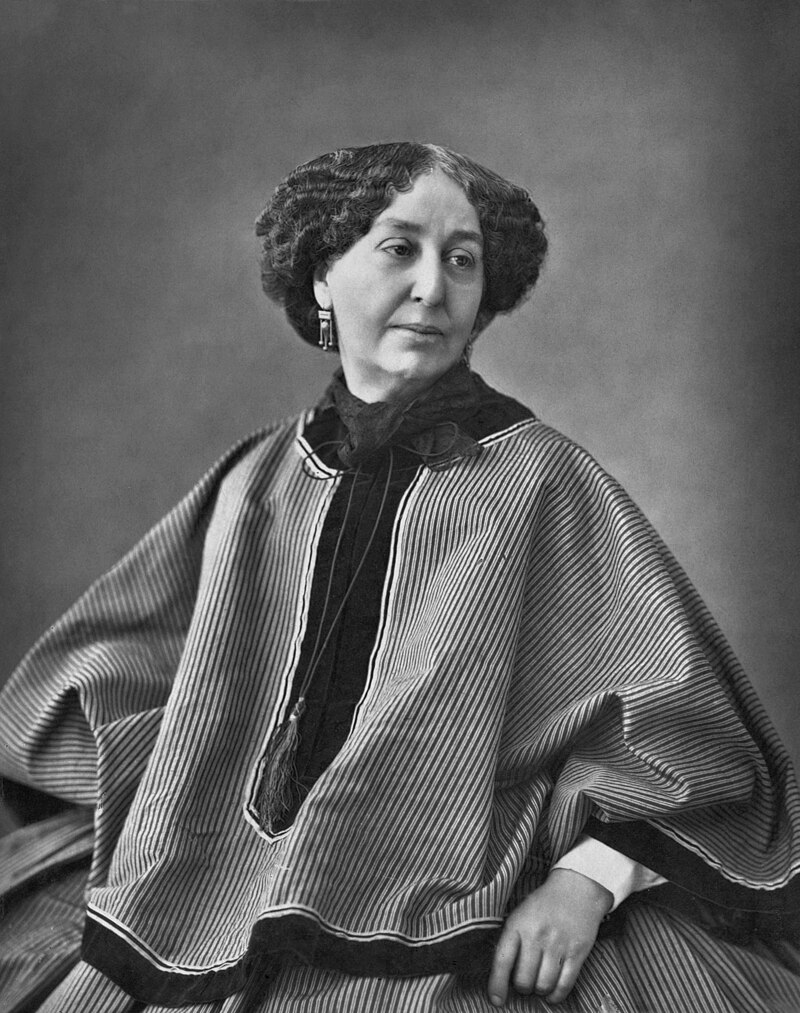

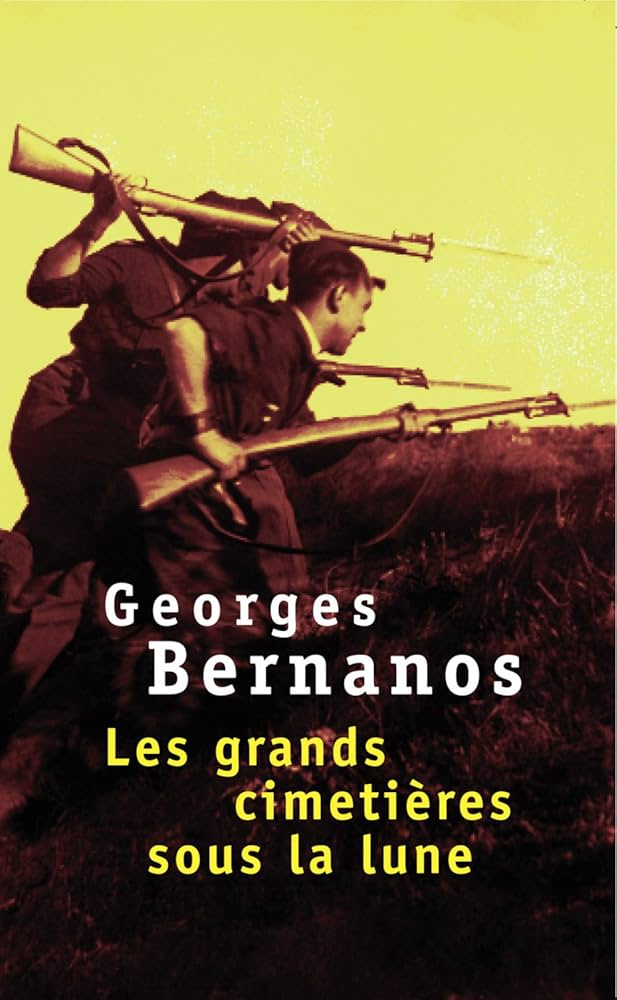

George Bernanos, The Great Cemeteries under the Moon (1938)

I am mostly been bound to my laptop, to my room, to our apartment here in the village of Landschlacht.

Above: Psychiatrische Klinik Münsterlingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Except for last Sunday – 9 March 2025.

Above: Card of Rorschach ink blot test

The pleasant lakeside resort of Rorschach (nothing to do with the inkblot test of the same name) occupies a bay below the grassy Rorschach Mountain, 9 km north of St. Gallen.

Above: Rorschach, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

Rorschach Hafen Bahnhof (harbor station) lies directly on the lakefront alongside the old Kornhaus, emblem of a once thriving grain trade between St. Gallen and Germany.

Above: Rorschach Harbor Station

Above: Rorschach Kornhaus (Granary) Museum Gallery

Once upon a time, in summer, just beyond here you could rent boats and pedalos and also swim from the 1920s bathhouse, Badhütte.

But the bath house burnt down last year.

Above: Rorschach Badhütte

From the harbor, Hauptstrasse (Main / High Street) heads east inland, flanked by fine 16th to 18th century houses with attractive oriel windows.

Above: Hauptstrasse, Rorschach

The Kolumbanskirche (St. Columba’s Church) just off the street is a broad, white, late Baroque church dedicated to the Irish monk Columba, with much gilded glitter inside.

Above: Kolumbanskirche, Rorschach

Above: Interior of Kolumbanskirche, Rorschach

Rorschach is first mentioned in 850 as Rorscachun.

In 947, Otto I granted the Abbot of St. Gall the right to operate markets, mint coins and levy tariffs at Rorschach.

Above: Seal of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I (912 – 973)

In 1490 the Rorschacher Klosterbruch or destruction of the Abbey at Rorschach touched off the St. Gallen War.

Above: Attack by St. Gallen and Appenzell troops on the Mariaberg Monastery, Rorschach, 1489 – St. Gallen War (1489 – 1490)

Following decades of conflict with the City of St. Gallen, in late 1480 Abbot Ulrich Rösch began planning to move the Abbey away from the City of St. Gallen to Rorschach.

Above: Abbey of St. Gallen, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

By moving he hoped to escape the independence and conflict in the city.

Additionally, by moving closer to the important lake trade routes, he could make Rorschach into a major harbor and collect a fortune in taxes.

Above: Abbot Ulrich Rösch (1426 – 1491)

In turn Mayor Varnbüler and the City feared that a new harbor on the lake would cause trade to bypass St. Gallen and Appenzell.

Above: St. Gallen, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

Above: Appenzell, Canton Appenzell Innerrhoden, Switzerland

They would then be forced to go through the Prince-Bishop’s harbor to sell their fabric.

Though the Cities of St. Gallen and Appenzell opposed the new monastery, after the approval of Pope Sixtus IV and protracted negotiations with Emperor Friedrich III the cornerstone of the new Mariaberg Abbey was laid on 21 March 1487.

Above: Pope Sixtus IV (né Francesco della Rovere) (1414 – 1484)

Above: Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich III (1415 – 1493)

Above: Mariaberg Abbey, Rorschach

At first the City simply protested the Abbot’s plan, but when that went nowhere, they began planning an attack on the Abbey.

They believed that the Swiss Confederation would not intervene due to tensions between them and the Swabian League.

Above: Flag of the Swiss Confederacy (1291 – 1798)

Above: Coat of arms of the Swabian League (1488 – 1534)

On 28 July 1489 a group of 1,200 Appenzellers and 350 St. Galleners assembled at Grub (now part of Eggersriet).

Above: Grub, Eggersriet, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

They marched on the Abbey.

They quickly tore down the walls and burned everything they could find.

After spending the night drinking and feasting on the abbot’s supplies, they returned to their homes.

The attack cost the Abbot the 13,000 gulden he had already spent on construction along with an additional 3,000 in furniture and supplies.

Above: Mariaberg Abbey, Rorschach

The Abbey’s vassals were supportive of the actions of the city and Appenzell.

On 21 October 1489, the Abbey signed the Waldkircher Bund with the rebels.

The Abbot spent the following months seeking support from his allies in the Old Swiss Confederation to punish St. Gallen and Appenzell.

Initially he had little success.

While the four allied Cantons of Zürich, Lucerne, Schwyz and Glarus generally supported the Abbot, the remainder of the Confederacy did not.

However, the creation of the Waldkircher Bund appeared threatening to the Confederation and moved it to support the Abbot.

On 24 January 1490, the Confederacy allowed the four cantons to attack the City and Appenzell.

Facing forces from the Confederation, the Waldkircher Bund dissolved as each group prepared to defend themselves.

The Swiss army besieged St. Gallen on 11 February.

On 15 February the City surrendered.

The peace treaty dissolved the Bund, restored the Abbot’s lands, allowed him to rebuild Mariaburg Abbey but required him to remain in St. Gallen.

Mariaberg Monastery was rebuilt starting in 1497 and completed 1518.

But it only served the Monastery of St. Gallen as an administrative center and later became a school.

Above: Mariaberg Schoolhouse, Rorschach

Train lines link the city to St. Gallen, St. Margrethen and Romanshorn.

Above: View from Höchst to Sankt Margrethen, the motorway No. 1, the main railway station, Sankt Margrethen, Canton St. Gallen

Above: Romanshorn, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

A rack railway, the Rorschach-Heiden Bahn, leads to Heiden (800 metres above sea level).

Above: Rorschach – Heiden Railway train, Appenzeller Bahnen, Rorschach Hafen Bahnhof

Above: Heiden Station, Canton Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Switzerland

In 1856, Rorschach Station became the terminus of the Zürich – St. Gallen Line.

Above: Rorschach Hauptbahnhof (Central Station)

Above: Zürich, Canton Zürich, Switzerland

Formerly, train carriages were transported over the Bodensee (Lake Constance).

Above: Satellite view of the Bodensee

Thus it was possible to reach Heiden from Frankfurt or Berlin without changing trains.

Above: Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany

Above: Berlin, Germany

The highway A1 runs close to the south of Rorschach, but the town does not have its own junction.

The highway leads towards Sankt Gallen to the west and Sankt Margrethen to the east.

Rorschach also has a harbor served by passenger ferries.

These travel to nearby towns on the Swiss and German sides of the Lake.

Above: Rorschach Hafen (harbor)

A number of hiking trails either start or end in Rorschach.

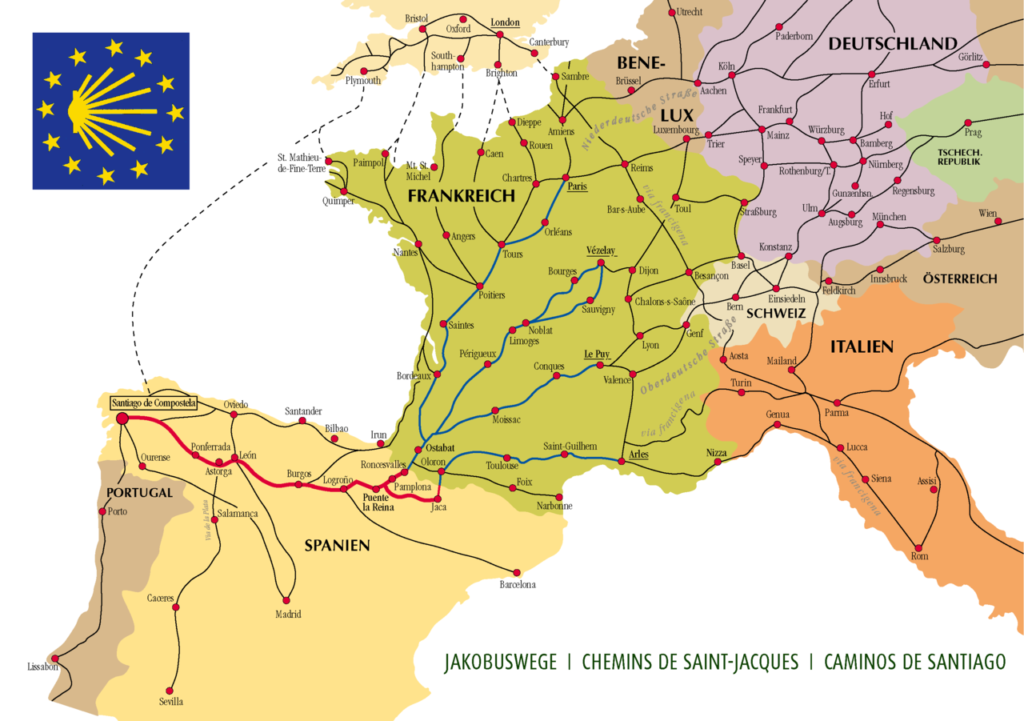

These include the Via Jacobi (one of the routes of the Way of St. James), the Alpenpanoramaweg to Geneva, and the Rheintaler Höhenweg to Sargans.

Above: Cathedral, Santiago de la Compostela, Galicia, Spain – end destination of the Way of St. James

Above: Geneva (Genf / Genève), Switzerland

Above: Schloss (castle) Sargans, Sargans, Canton St. Gallen

The urge to hike – if only I had hiking boots here – is strong.

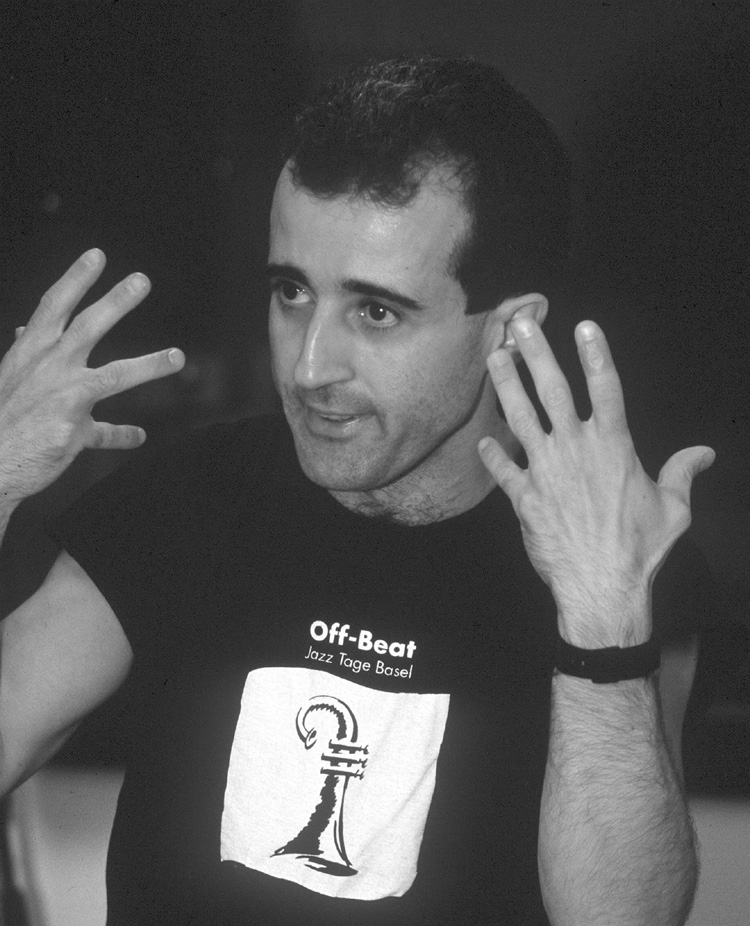

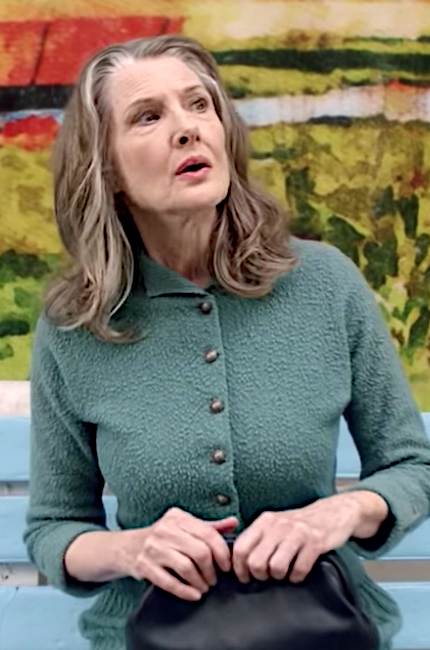

Above: Your humble blogger

The urge to visit Heiden is also strong.

Above: Heiden, Canton Appenzeller Ausserrhoden

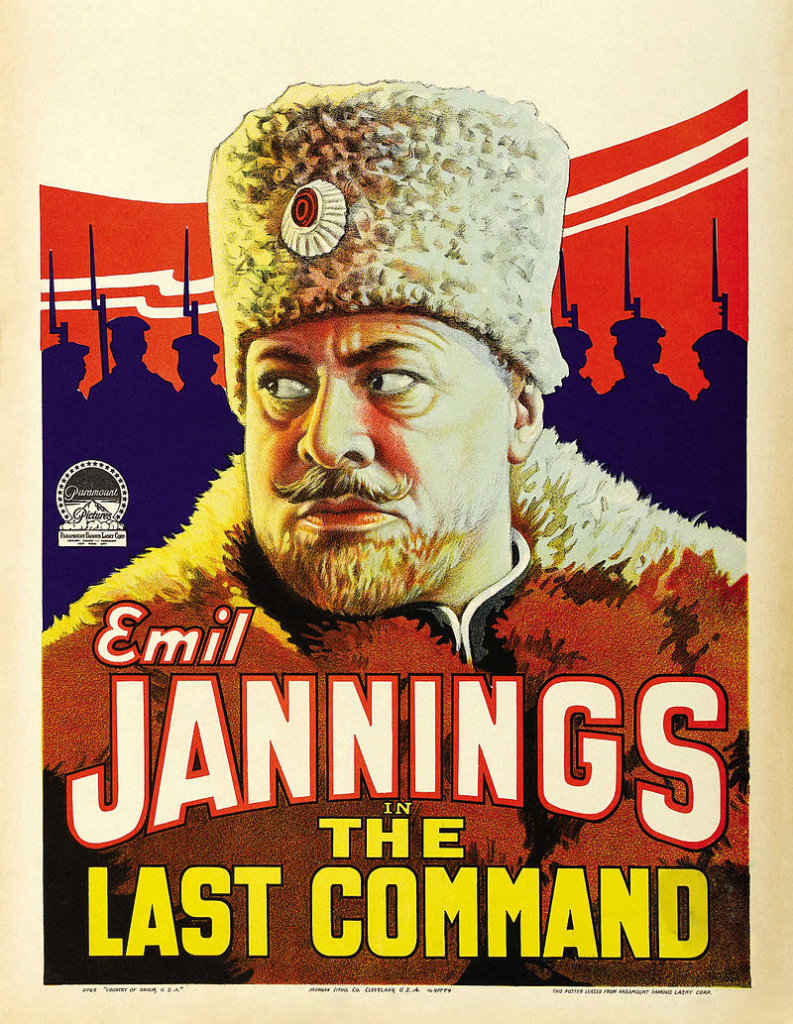

Rorschach was the birthplace of Hollywood actor Emil Jannings.

He was popular in Hollywood films in the 1920s.

Above: Swiss actor Emil Jannings (1884 – 1950)

He was the first recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor for starring roles in The Last Command (1928) and The Way of All Flesh (1927).

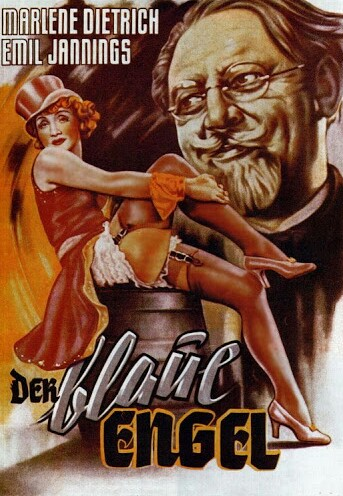

Jannings is best known for his collaborations with F. W. Murnau and Josef von Sternberg, including the 1930 film The Blue Angel (Der blaue Engel), with Marlene Dietrich.

The Blue Angel was meant as a vehicle for Jannings to score a place for himself in the new medium of sound film, but Dietrich stole the show.

Jannings later starred in a number of Nazi propaganda films, which made him unemployable as an actor after the defeat of Nazi Germany.

At the far end of the waterfront, near the main station at Churerstrasse (Chur Street) 10, you will see the gleaming cube of Forum Würth, which looks very much like the corporate headquarters it is, but it also contains two floors of gallery space, showing often excellent exhibitions of works drawn from the Würth Foundation.

Above: Forum Würth, Rorschach

The Würth Group is a worldwide wholesaler of fasteners, screws and screw accessories.

Würth expanded its range and today offers a full range of business equipment for craft businesses in a kind of supermarket of its own.

Würth offers dowels, chemicals, electronic and electromechanical components, furniture and construction fittings, tools, machines, installation material, automotive hardware, inventory management, storage and retrieval systems.

The group of over 400 companies across 80+ countries has been servicing the automotive, woodworking, metalworking, industrial and construction industries.

Würth was founded in 1945 by Adolf Würth in Künzelsau, Germany.

The company is family owned and has been run by his son Reinhold Würth since 1954.

The Würth Collection comprises over 18,000 works from the 15th century to modern and contemporary art, primarily paintings and sculptures.

It ranks among the greatest European private art collections.

The works of art are regularly displayed to the public in five museums in Germany and ten associated galleries of the Würth Group across Europe, including:

- Kunsthalle Würth and Johanniterkirche in Schwäbisch Hall in Germany

Above: Kunsthalle Würth/Johanniterkirche, Schwäbisch Hall, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- Museum Würth and Museum Würth 2 in Künzelsau in Germany

Above: Museum Würth, Künzelsau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Above: Museum Würth 2, Künzelsau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- the Art Forum Würth Capena in Italy

Above: Art Forum Würth, Capena, Rome, Italy

- the Musée Würth France Erstein in France

Above: Musée Wurth, Erstein, Alsace, France

- the Museo Würth La Rioja in Spain.

Above: Museo Würth, La Rioja, Spain

In Switzerland, Würth maintains:

- Forum Würth Arlesheim

Above: Forum Würth, Arlesheim, Canton Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland

- Forum Würth Chur

Above: Forum Würth, Chur, Canton Graubünden, Switzerland

- Würth Haus Rorschach

Above: Forum Würth, Rorschach, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

Admission is free.

Dotted around the building are several impressive sculptures, including Henry Moore’s Large Interior Form (1982).

Above: Henry Moore’s Large Interior Form

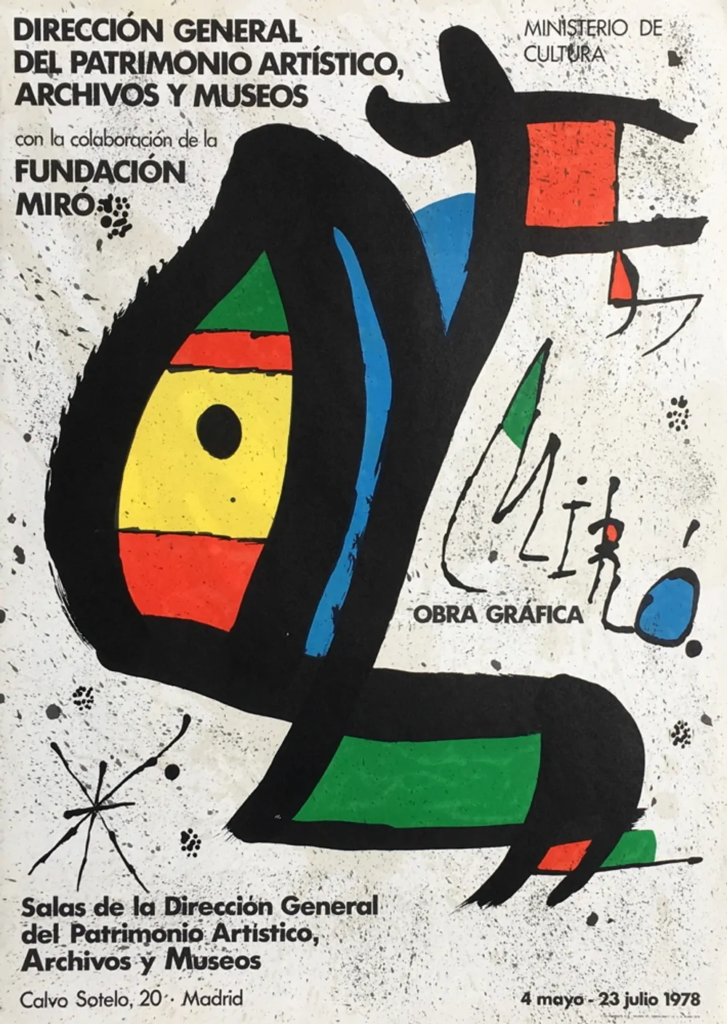

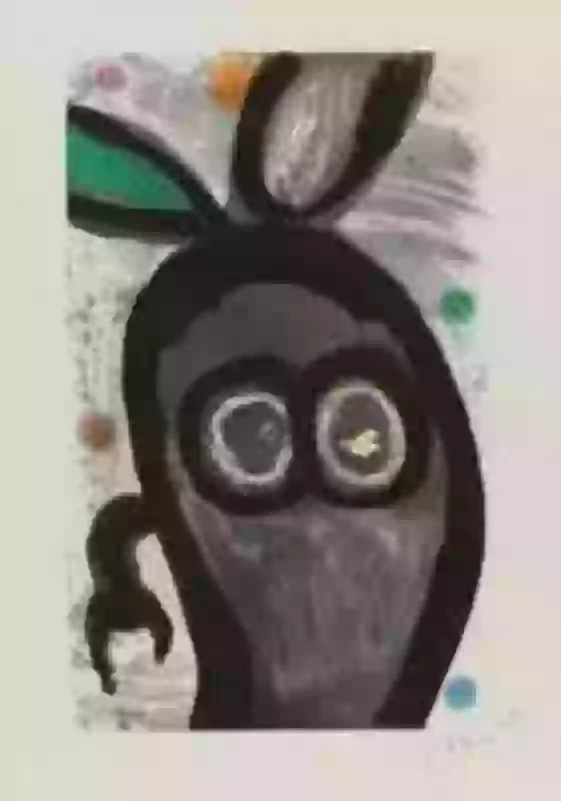

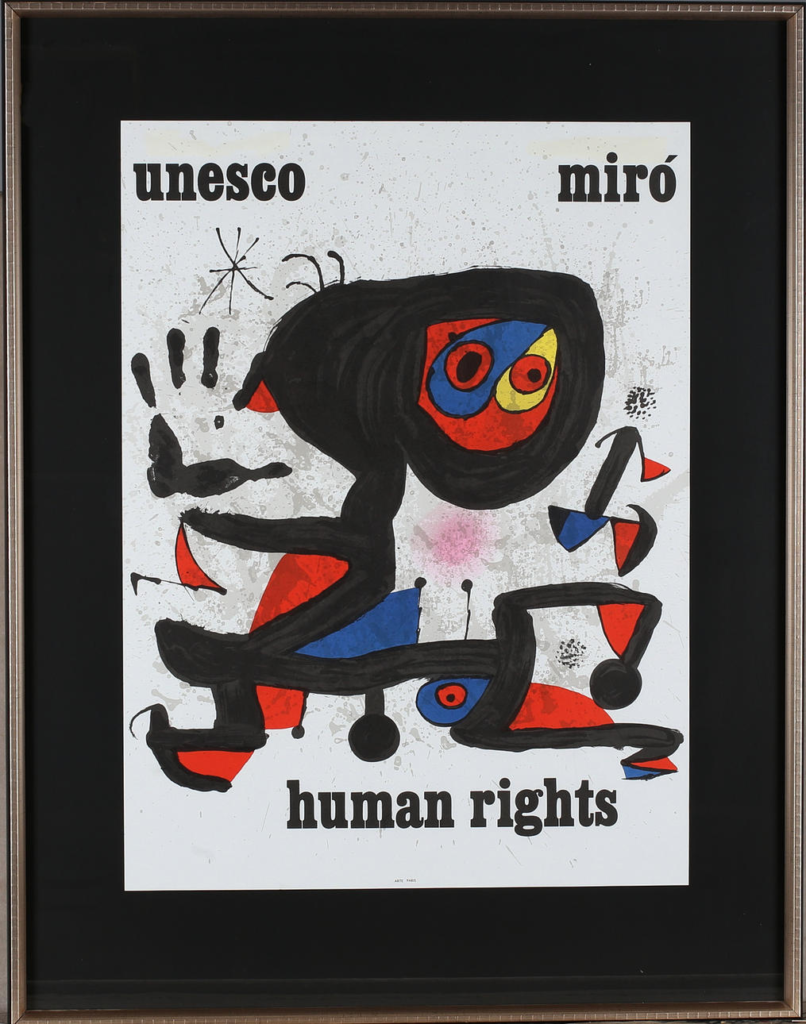

We attended a small exhibition of Joan Miró paintings at the Forum Würth.

Above: Joan Miró: Alles ist Poesie, Sammlung Würth (Everything is poetry, Würth Collection)

Earning international acclaim, Miró’s work has been interpreted as Surrealism (expression of the unconscious mind) but with a personal style, sometimes also veering into Fauvism (color over value) and Expressionism (emotional experience over reality).

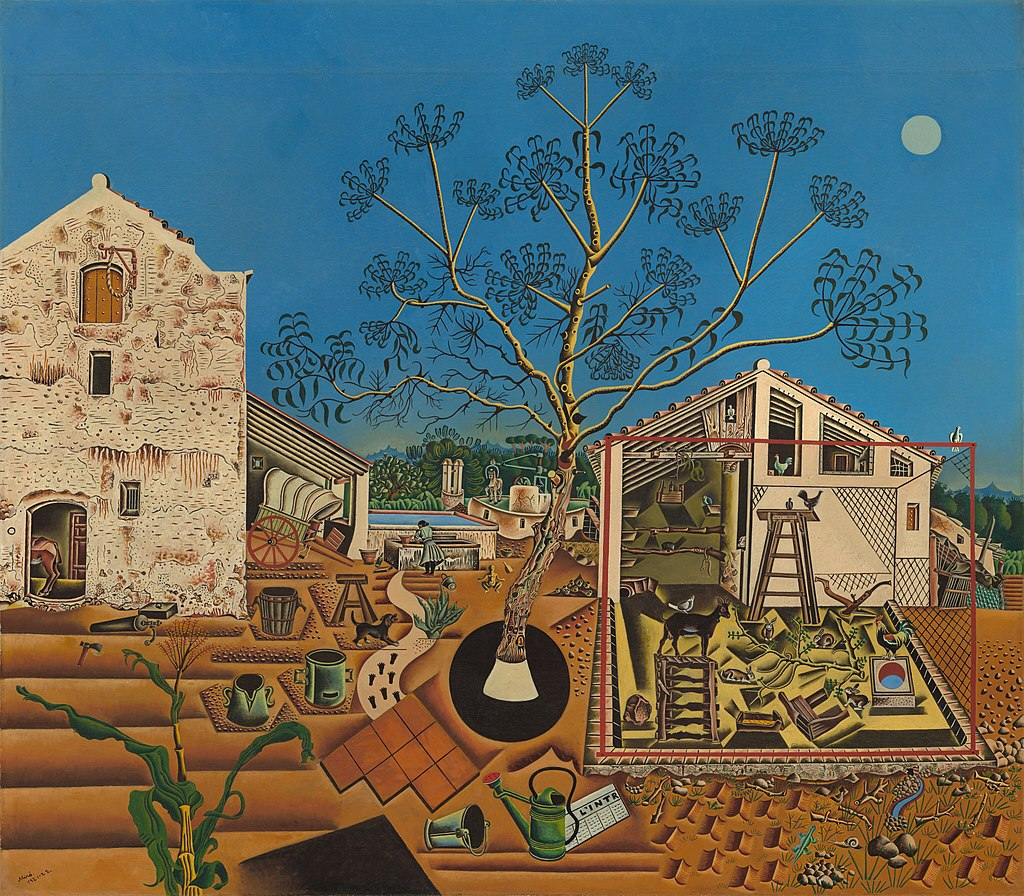

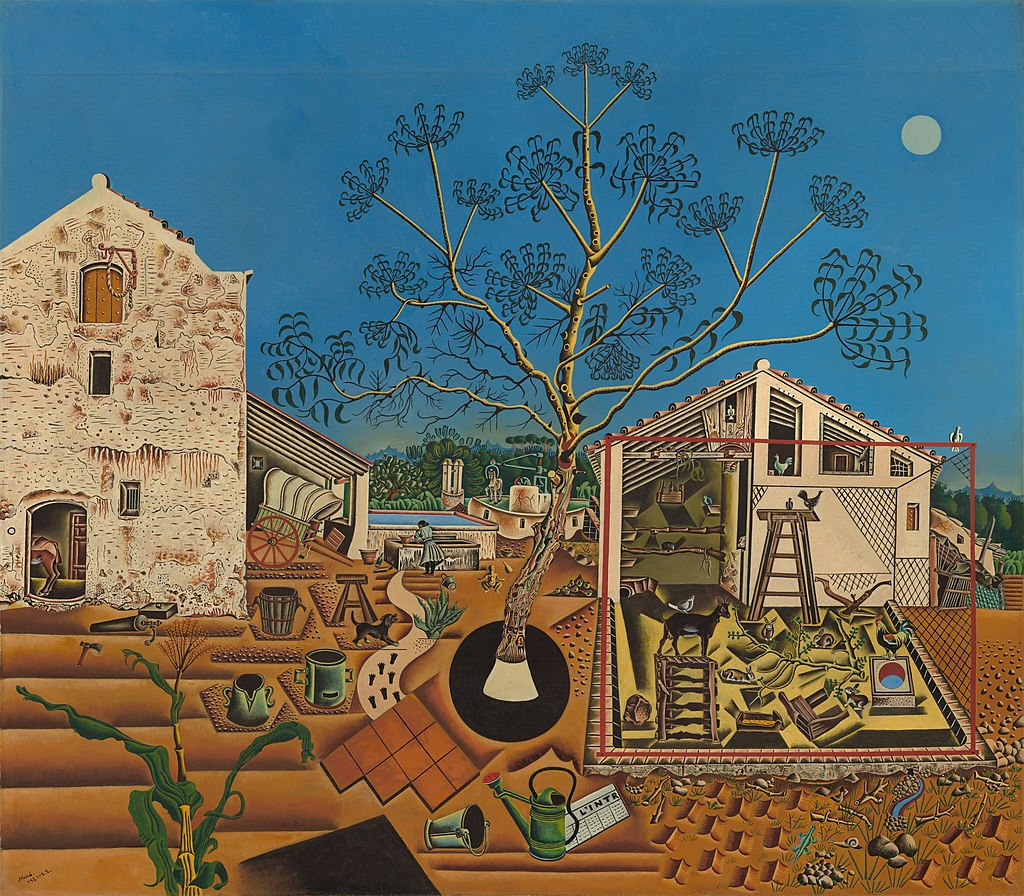

Above: Joan Miró, The Tilled Field

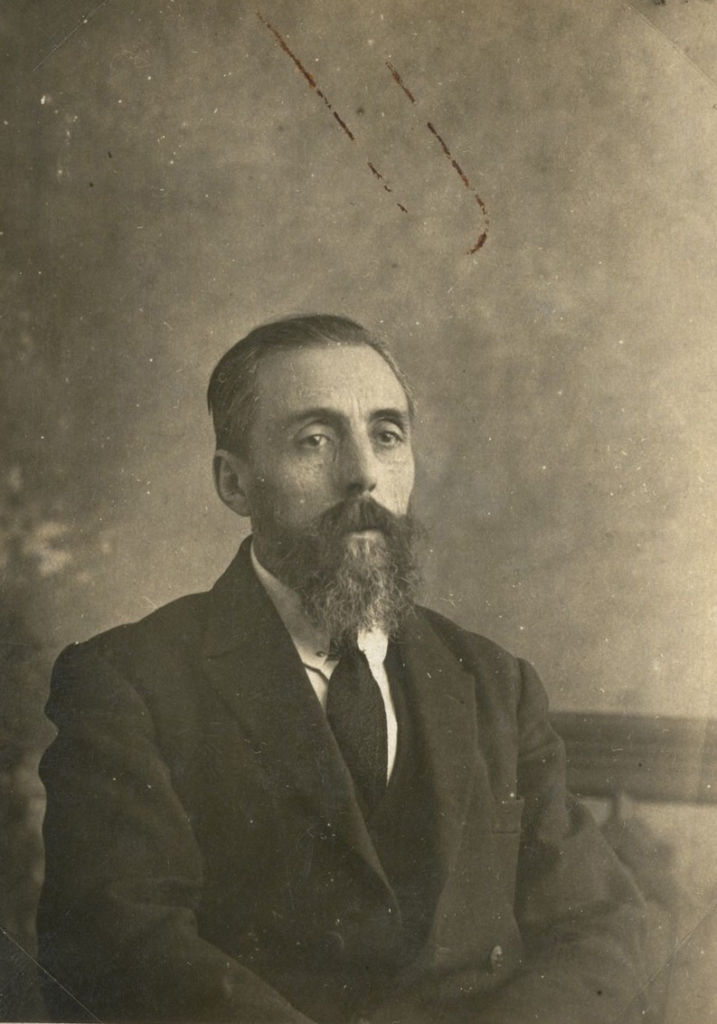

Above: Joan Miró, Portrait of Vincent Nubiola

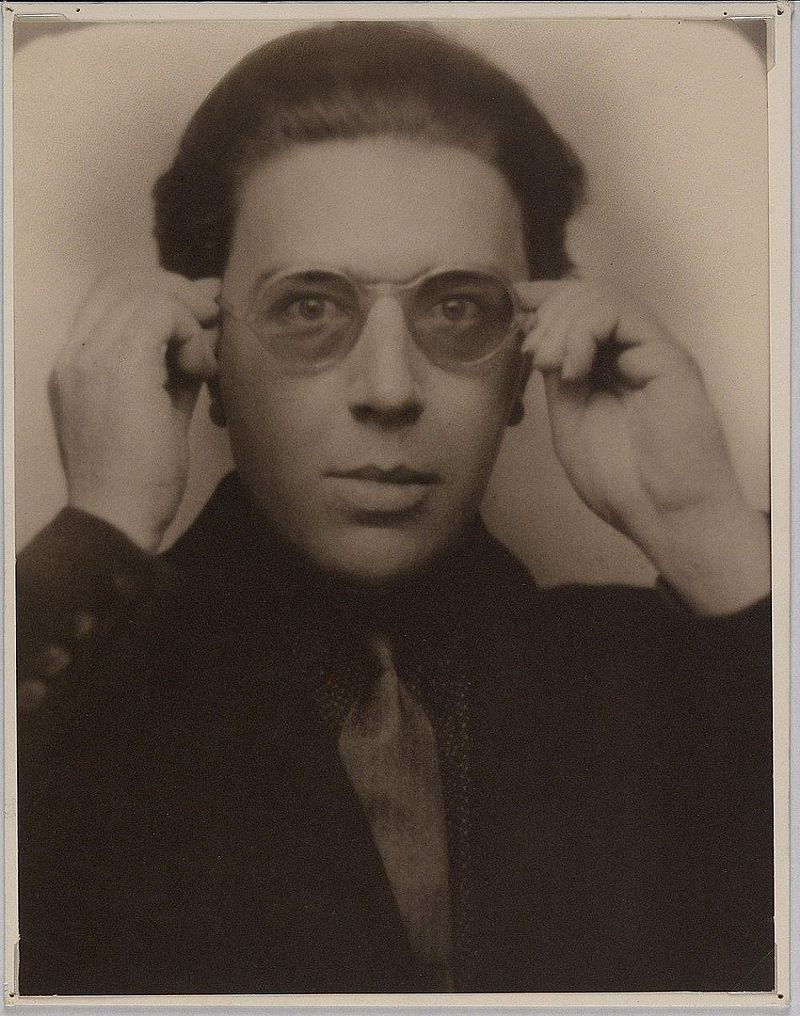

Above: Joan Miró

He was notable for his interest in the unconscious or the subconscious mind, reflected in his re-creation of the childlike.

His difficult-to-classify works also had a manifestation of Catalan pride.

In numerous interviews dating from the 1930s onwards, Miró expressed contempt for conventional painting methods as a way of supporting bourgeois society, and declared an “assassination of painting” in favour of upsetting the visual elements of established painting.

Today, Miró’s paintings sell for between US$250,000 and US$26 million – US$17 million at a US auction for the La Caresse des étoiles (1938) on 6 May 2008, at the time the highest amount paid for one of his works.

Above: Joan Miró, La Caresse des étoiles

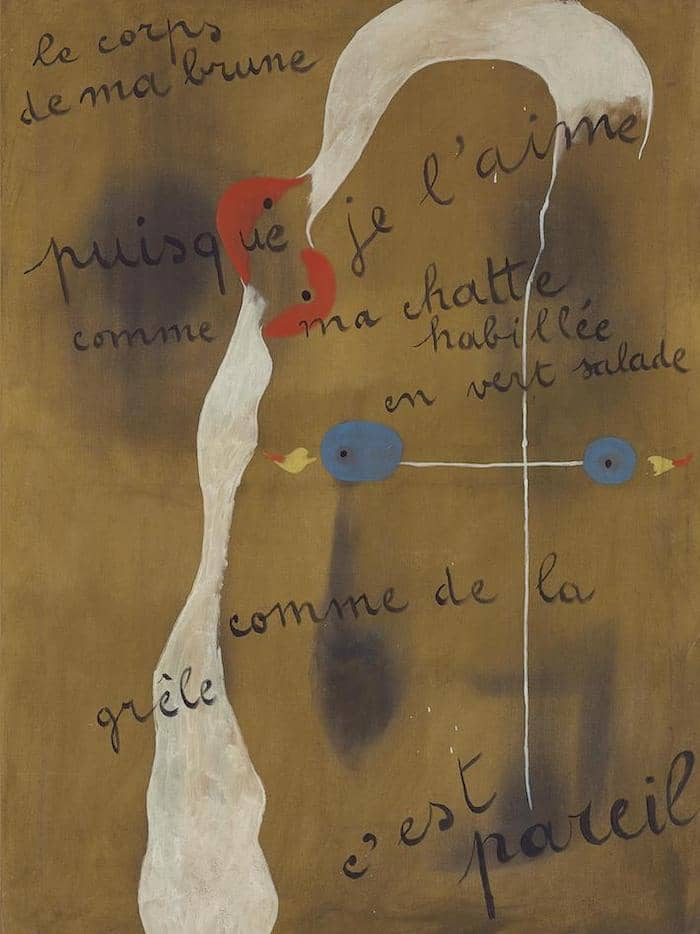

In 2012, Painting-Poem (“le corps de ma brune puisque je l’aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c’est pareil“) (1925) was sold at Christie’s London for $26.6 million.

Above: Joan Miró, Painting Poem

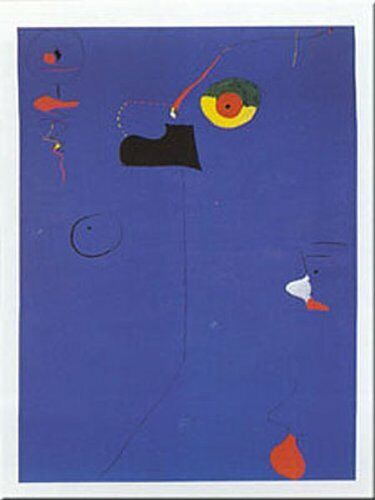

Later that year at Sotheby’s in London, Peinture (Etoile Bleue) (1927) brought nearly £23.6 million with fees, more than twice what it had sold for at a Paris auction in 2007 and a record price for the artist at auction.

Above: Joan Miró, Peinture étoile bleue

On 21 June 2017, the work Femme et Oiseaux (1940), one of his Constellations, sold at Sotheby’s London for £24,571,250.

Above: Joan Miró, Femme et oiseaux

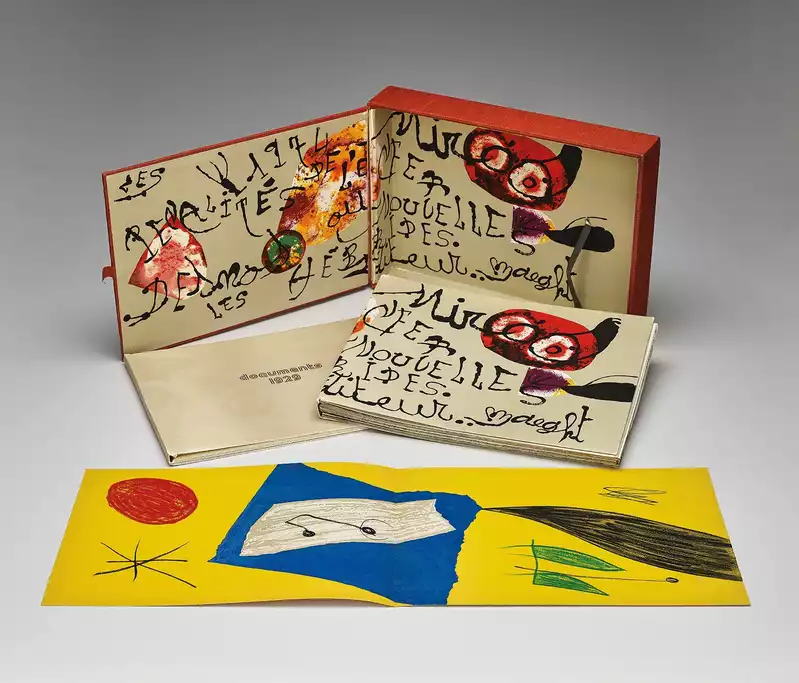

The Würth exhibition “Joan Miró: Everything is Poetry” presents mainly graphic art from the late oeuvre of the world-famous Catalan artist.

The works – from prints and drawings via various book illustrations to sculpture – highlight the artist’s creative and technical diversity.

Above: Joan Miró: Alles ist Poesie, Sammlung Würth

Miró saw himself as a “peinture-poète” (a painter poet).

Above: Spanish artist Joan Miró (1893 – 1983)

“Miró is regarded as one of the famous representatives of Surrealism alongside his contemporaries Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and André Masson.

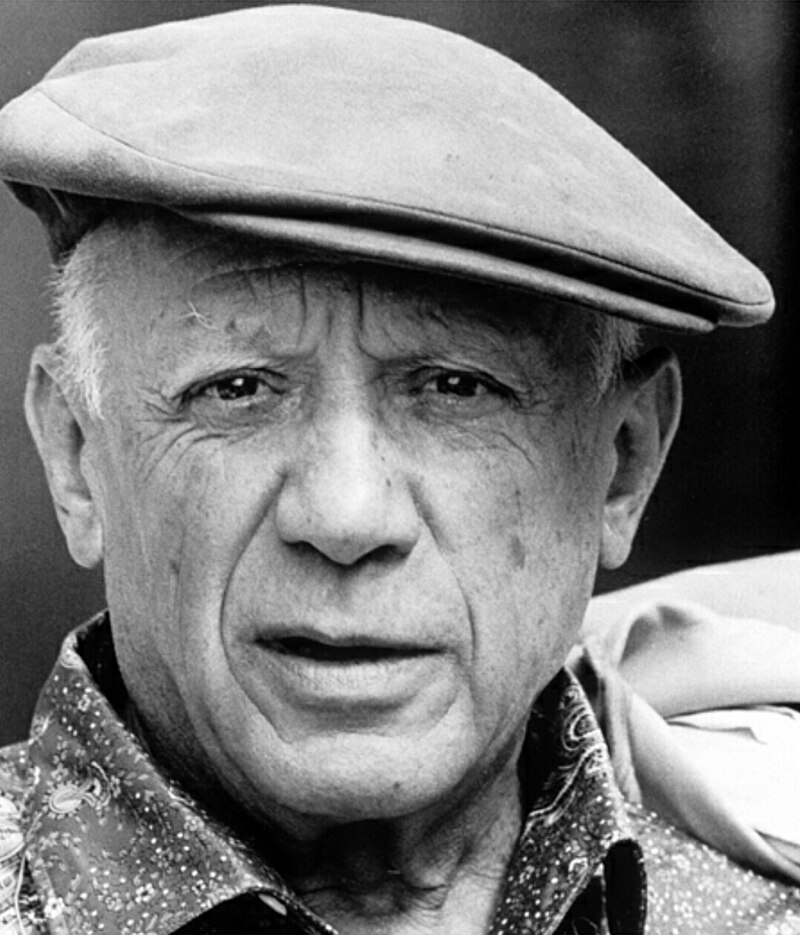

Above: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

Like his companions, Miró also developed a pictorial idiom of his own.

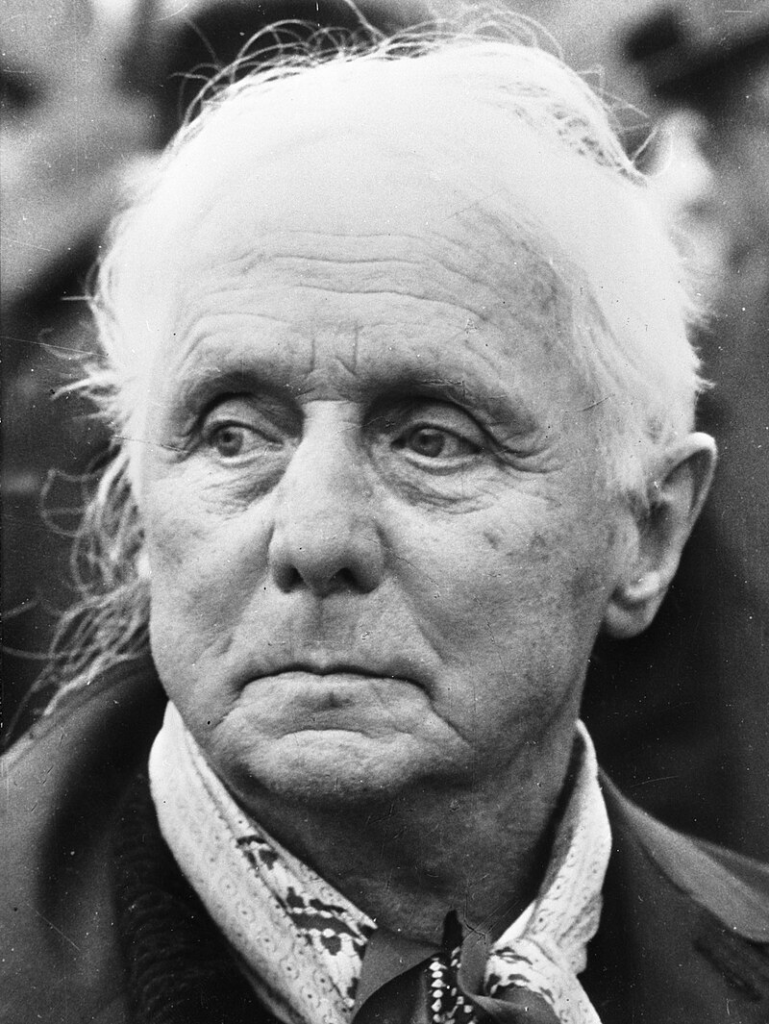

Above: German artist Max Ernst (1891 – 1976)

His aesthetic is determined by abstraction and characterized by symbolic forms and clear colors.

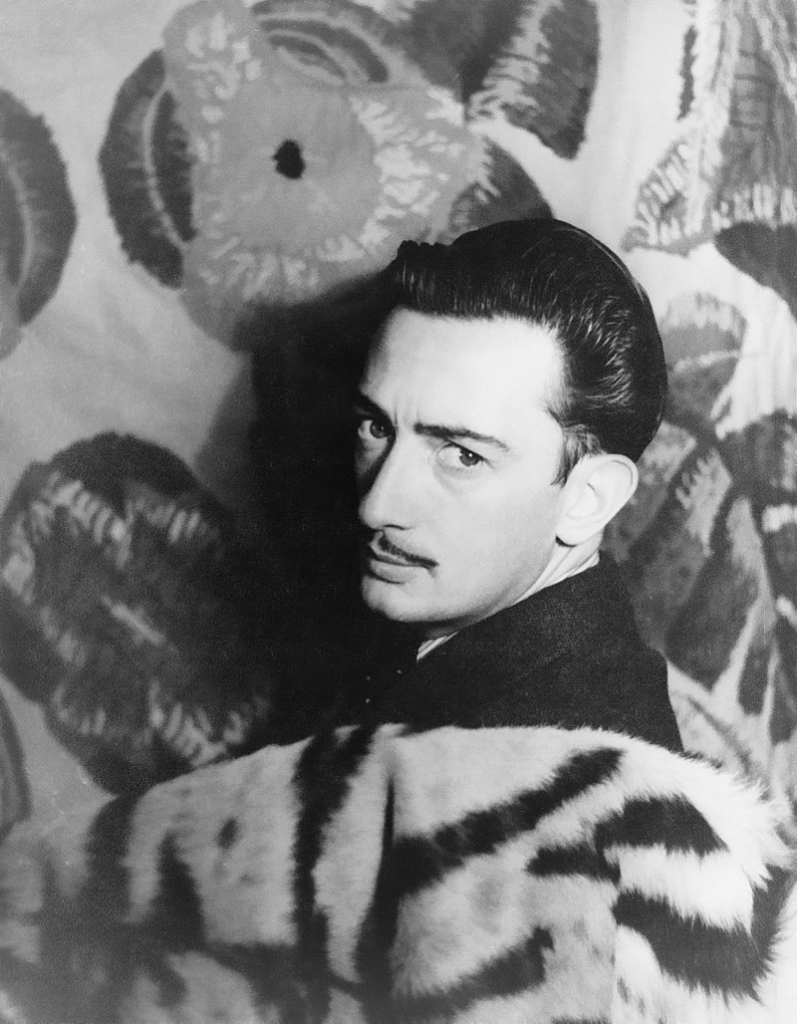

Above: Spanish artist Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989)

His great recognition value is due to a highly distinctive pictorial idiom.“

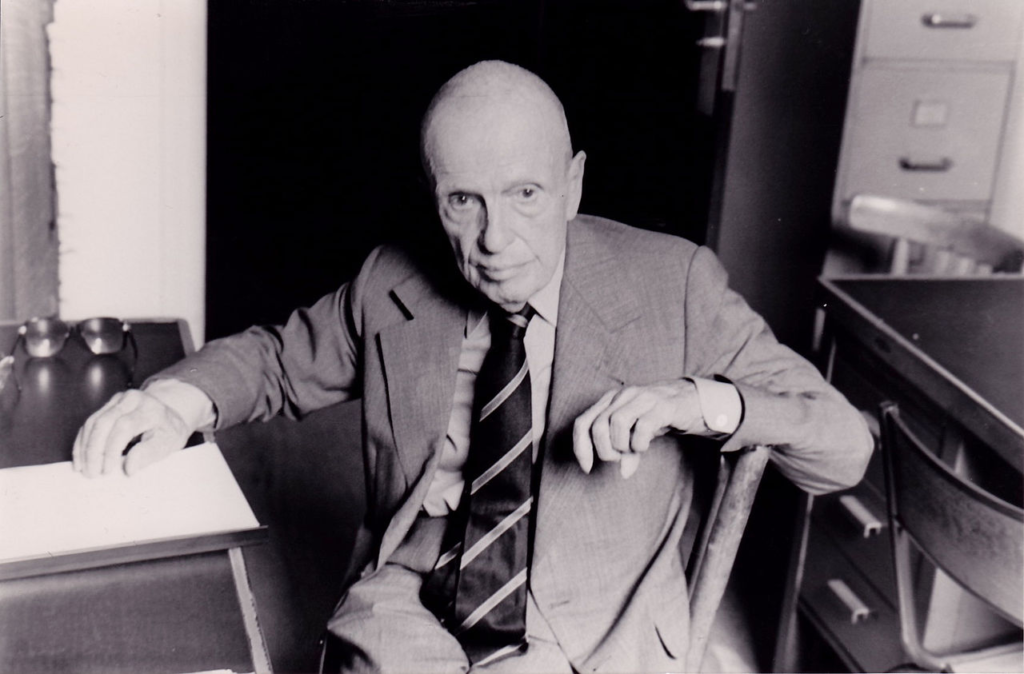

Above: French painter André Masson (1896 – 1987)

“Although the motifs are seemingly spontaneous and improvised, sometimes even childlike and playful, they are the result of calculated preparatory work and, in the face of a civil war in Spain marked by fascism and violence, sometimes conceal their serious subtext.

Above: Joan Miró, Lola

This combination of works by Miró provides insight into the artist’s life and work and at the same time points to the multifarious influences that shaped his oeuvre:

Paris intellectuals, theatre and poetry, as well as intuition and the natural forms of the Spanish landscape.“

Brochure, www.forum-wuerth.ch

Miró has been a significant influence on late 20th-century art, in particular the American abstract expressionist artists that include:

- Robert Motherwell

Above: American artist Robert Motherwell (1915 – 1991)

- Alexander Calder

Above: American sculptor Alexander Calder (1898 – 1976)

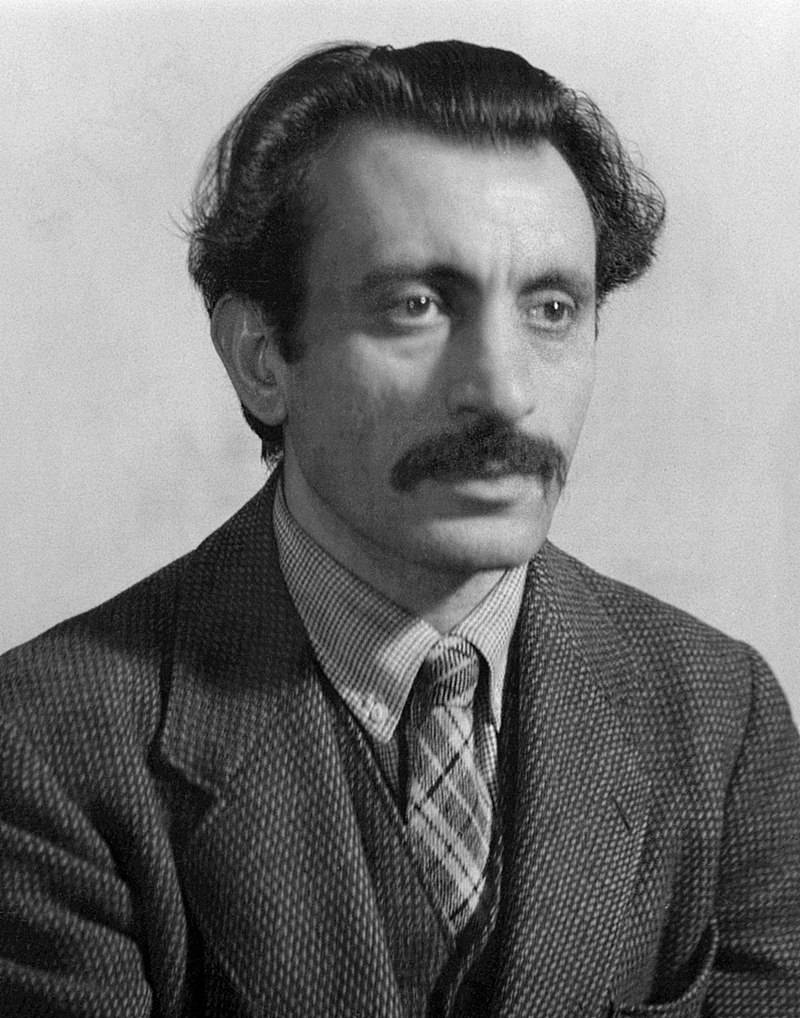

- Arshile Gorky

Above: Armenian painter Arshile Gorky (1904 – 1948)

- Jackson Pollock

Above: American painter Jackson Pollack (1912 – 1956)

- Roberto Matta

Above: Chilean painter Roberto Matta (1911 – 2002)

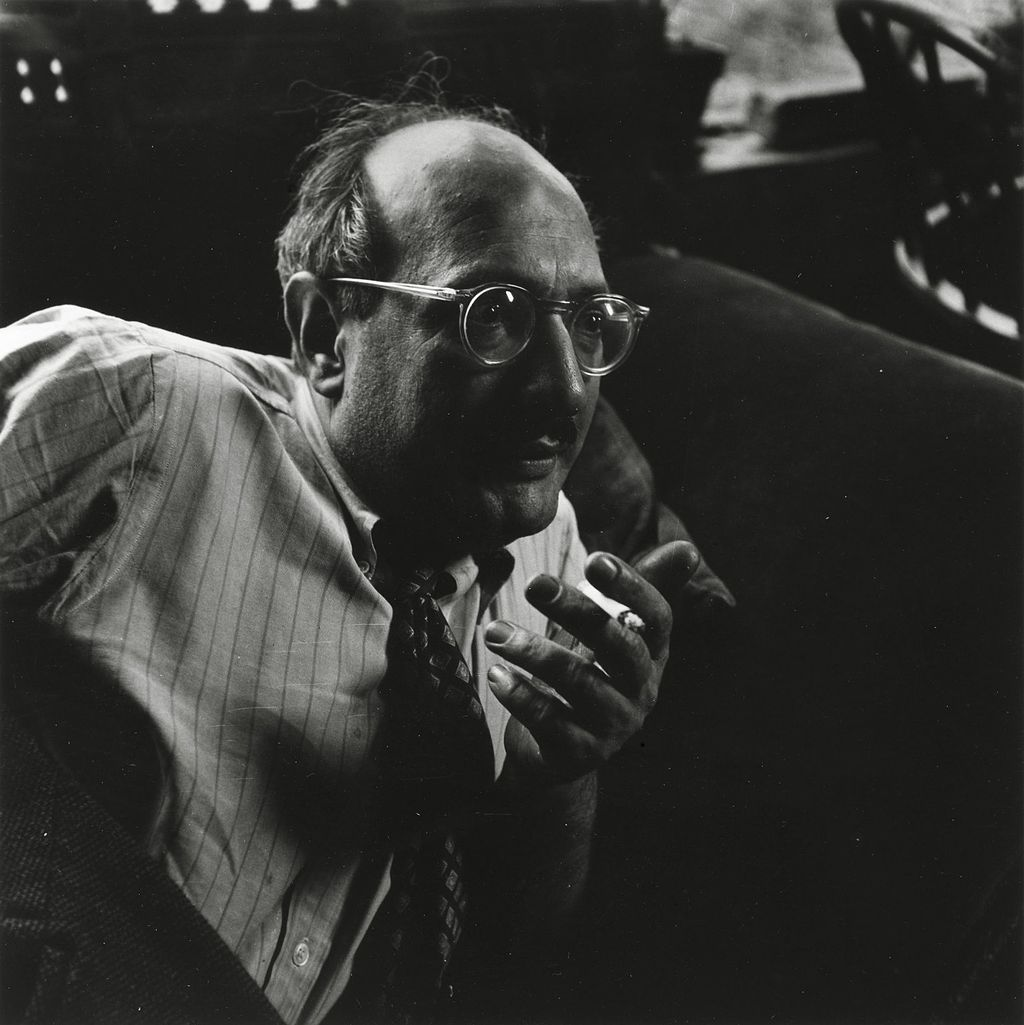

- Mark Rothko

Above: Latvian painter Mark Rathko (1903 – 1970)

Miró’s lyrical abstractions and color field paintings were precursors of that style by artists such as:

- Helen Frankenthaler

Above: American painter Helen Frankenthaler (1928 – 2011)

- Jules Olitski

Above: Ukrainian artist Jules Olitski (1922 – 2007)

- Morris Louis

Above: American painter Morris Louis (1912 – 1962)

- Paul Rand

Above: American graphic designer Paul Rand (1914 – 1996)

- Lucienne Day

Above: English textile designer Lucienne Day (1917 – 2010)

- Julian Hatton

Above: American artist Julian Hatton

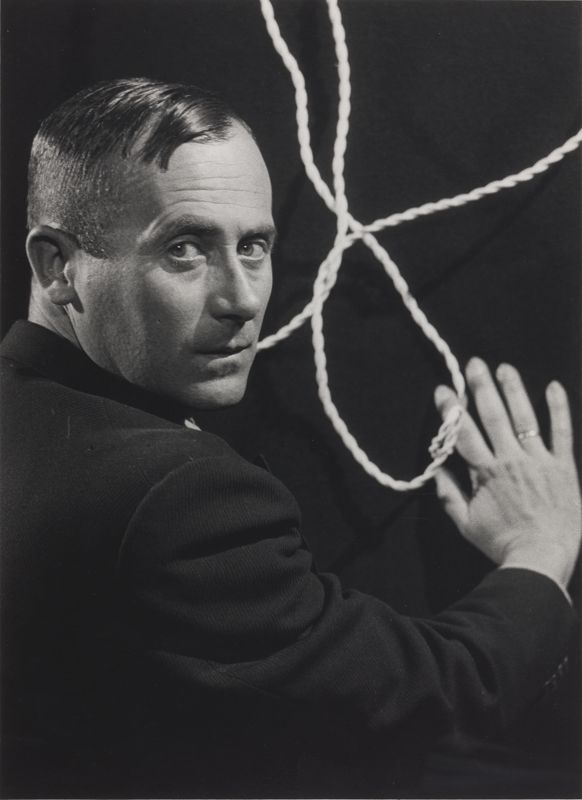

One of Man Ray’s 1930s photographs, Miró with Rope, depicts the painter with an arranged rope pinned to a wall, and was published in the single-issue surrealist work Minotaure.

Above: Man Ray, Miró with Rope

In 2002, American percussionist/composer Bobby Previte released the album The 23 Constellations of Joan Miró on Tzadik Records.

Inspired by Miró’s Constellations series, Previte composed a series of short pieces (none longer than about 3 minutes) to parallel the small size of Miró’s paintings.

Previte’s compositions for an ensemble of up to ten musicians was described by critics as “unconventionally light, ethereal, and dreamlike“.

Above: American composer Bobby Previte

I admit it.

I don’t get the fascination with Miró.

His work looks like it was designed by children for children.

Something that children do in art class and parents place upon the kitchen fridge.

I look at his art and I don’t have the foggiest idea of what I should think or feel about it.

Above: Joan Miró, Le roi des lapins

Born into a family of a goldsmith and watchmaker, Miquel Miró Adzerias, and mother Dolores Ferrà, Miró grew up in the Barri Gòtic neighborhood of Barcelona.

He began drawing classes at the age of seven at a private school at Carrer del Regomir 13, a medieval mansion.

Above: Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

To the dismay of his father, he enrolled at the fine art academy at La Llotja in 1907.

Above: La Llotja de la Seda, Valencia, Spain

He studied at the Cercle Artistic de Sant Lluc.

Above: Cercle Artistic de Sant Lluc, Barcelona

He had his first solo show in 1918 at the Galeries Dalmau (1906 – 1930), where his work was ridiculed and defaced.

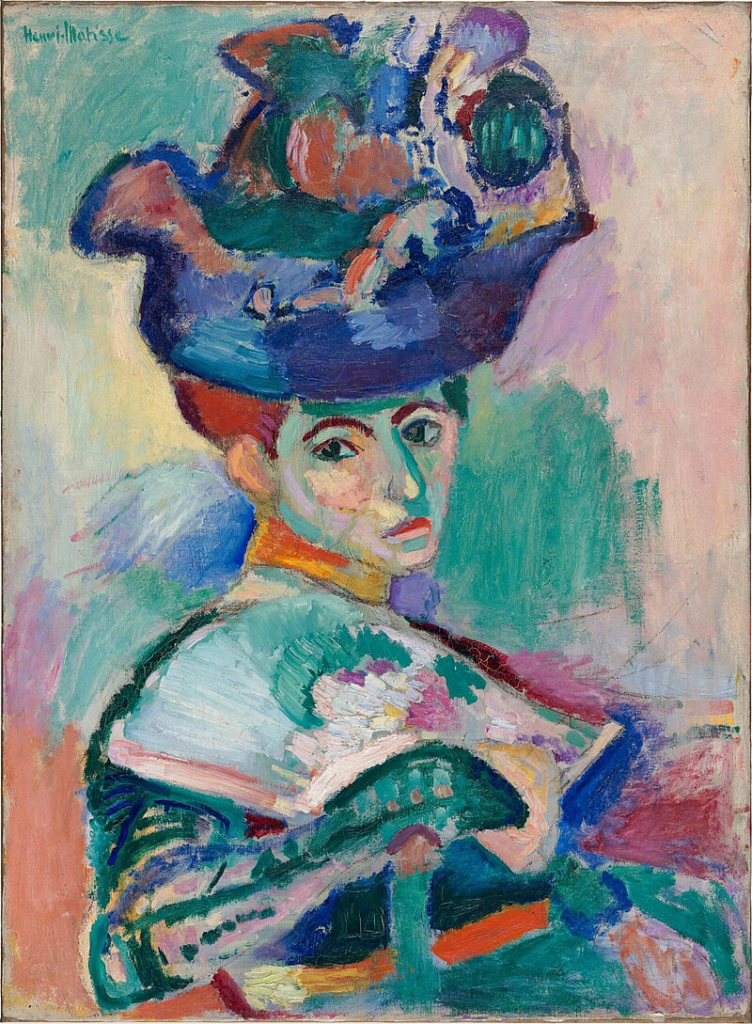

Inspired by Fauve and Cubist exhibitions in Barcelona and abroad, Miró was drawn towards the arts community that was gathering in Montparnasse and in 1920 moved to Paris, but continued to spend his summers in Catalonia.

Above: Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat

Above: Pablo Picasso, Girl with a Mandolin

(Fauvism is a style of painting and an art movement that emerged in France at the beginning of the 20th century.

It was the style of les Fauves (the wild beasts), a group of modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong colour over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism.

While Fauvism as a style began around 1904 and continued beyond 1910, the movement as such lasted only a few years, 1905 – 1908, and had three exhibitions.

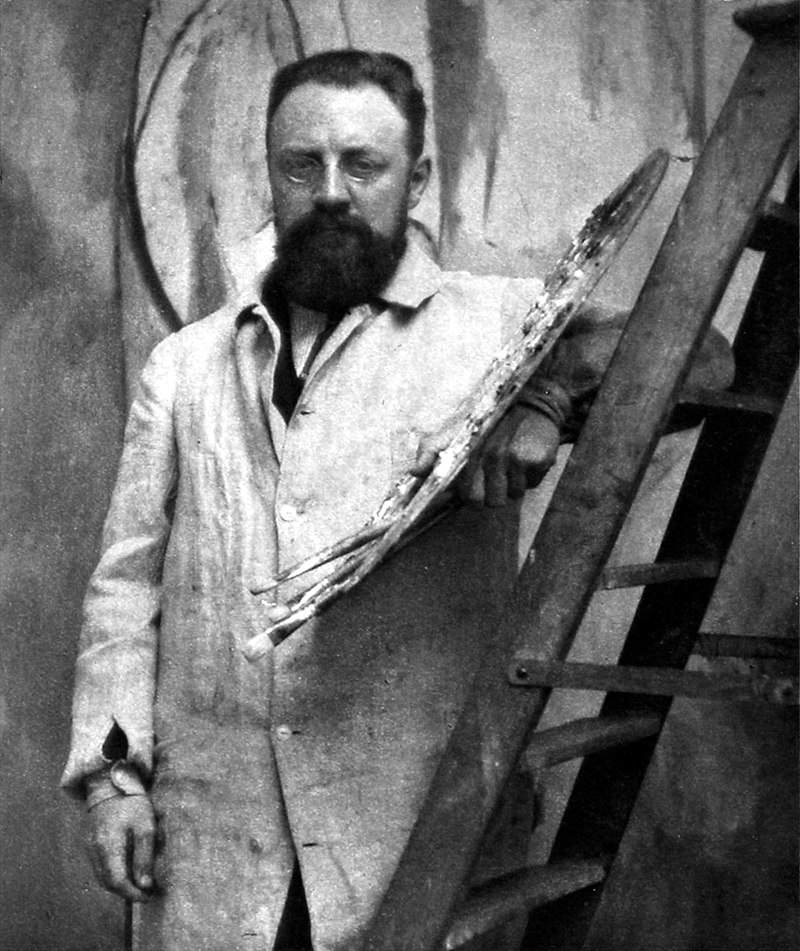

The leaders of the movement were André Derain and Henri Matisse.)

Above: French artist André Derain (1880 – 1954)

Above: French artist Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954)

(Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement begun in Paris that revolutionized painting and the visual arts, and influenced artistic innovations in music, ballet, literature, and architecture.

Cubist subjects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstract form — instead of depicting objects from a single perspective, the artist depicts the subject from multiple perspectives to represent the subject in a greater context.

Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century.

The term cubism is broadly associated with a variety of artworks produced in Paris (Montmartre and Montparnasse) or near Paris (Puteaux) during the 1910s and throughout the 1920s.

The movement was pioneered in partnership by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Above: French artist Georges Braque (1882 – 1963)

One primary influence that led to Cubism was the representation of three-dimensional form in the late works of Paul Cézanne.)

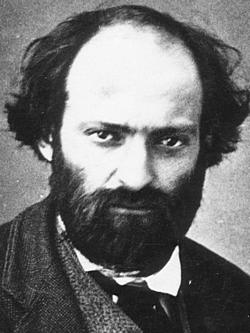

Above: French painter Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906)

Miró initially went to business school as well as art school.

He began his working career as a clerk when he was a teenager, although he abandoned the business world completely for art after suffering a nervous breakdown.

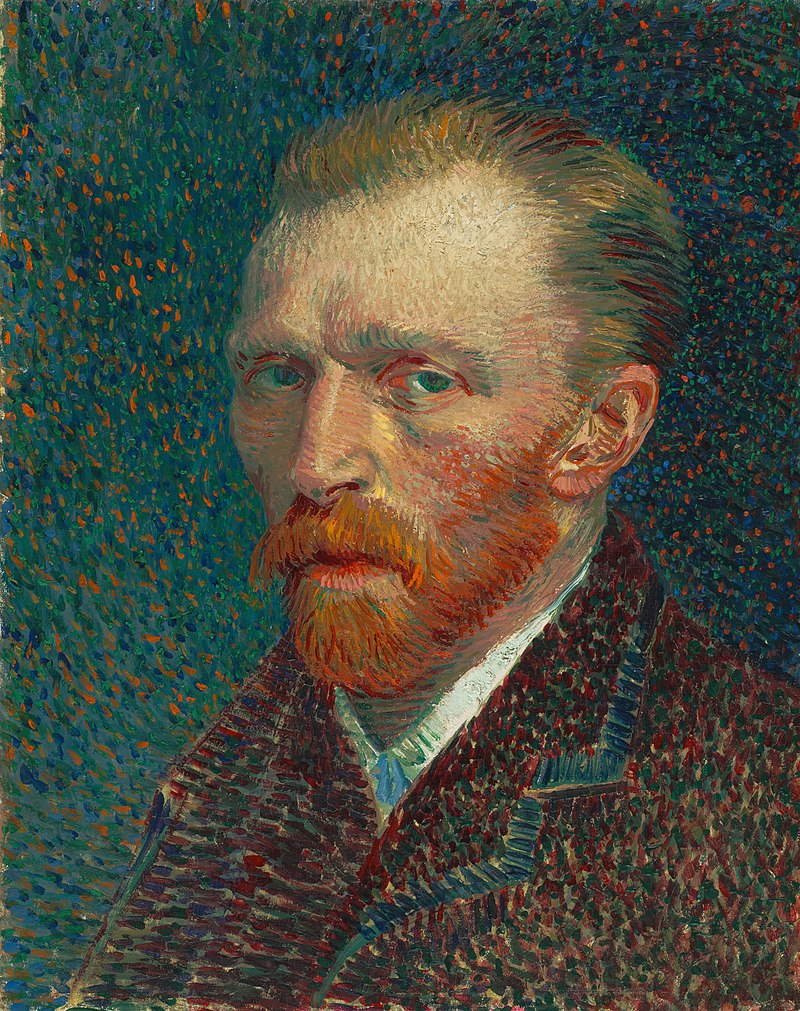

His early art, like that of the similarly influenced Fauves and Cubists, was inspired by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne.

Above: Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890)

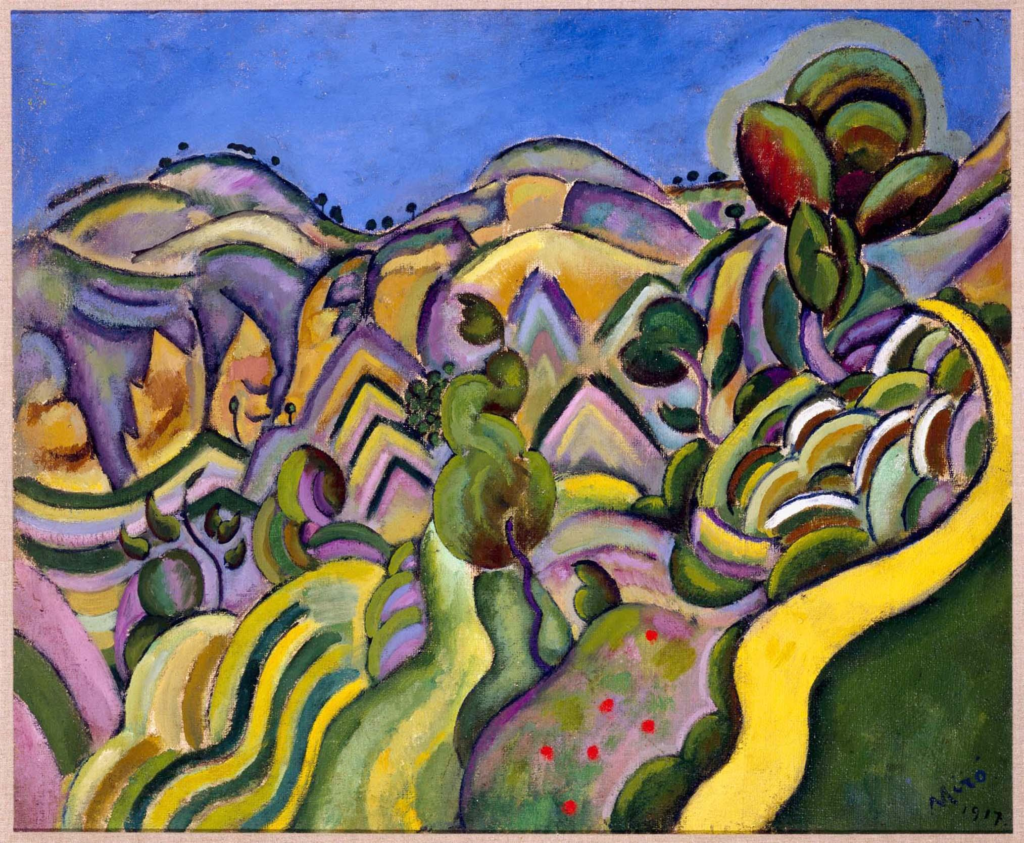

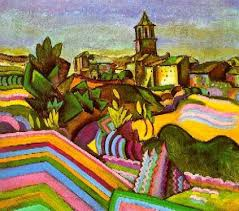

The resemblance of Miró’s work to that of the intermediate generation of the avant-garde has led scholars to dub this period his Catalan Fauvist period.

His early modernist works include:

- Portrait of Vincent Nubiola (1917)

- Siurana (the path)

Above: Joan Miró, Siurana (El camino)

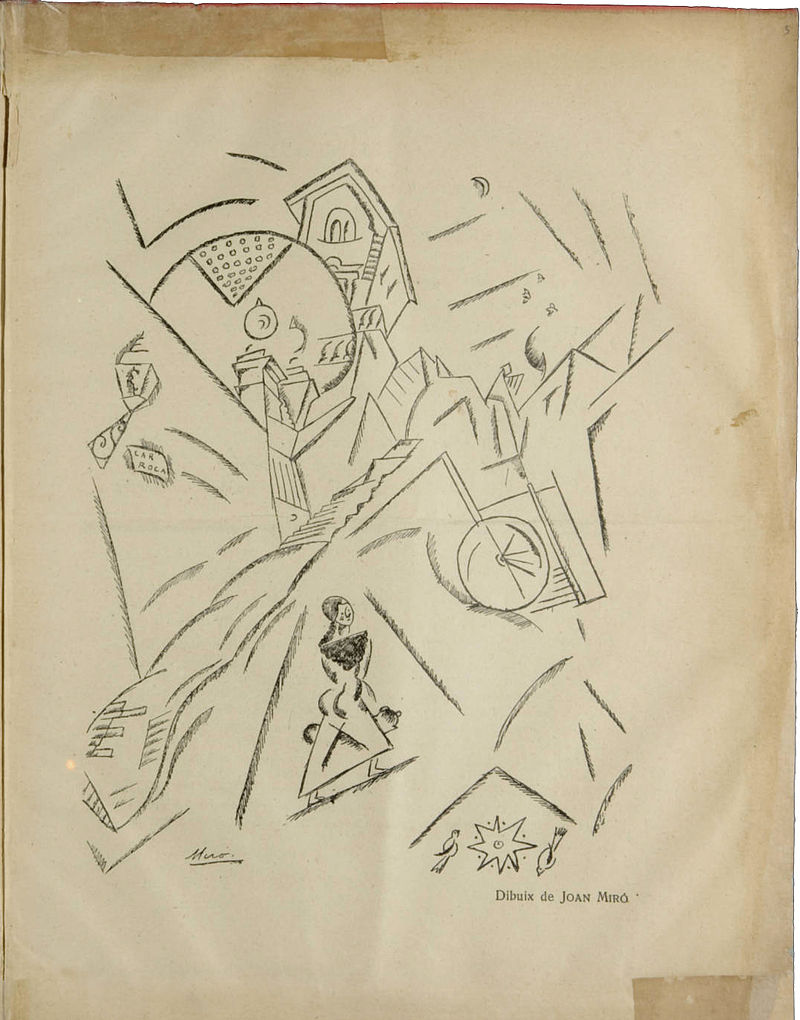

- Nord-Sud (1917)

Above: Joan Miró, Nord – Sud

- Painting of Toledo

Above: Joan Miró, Toledo

These works show the influence of Cézanne, and fill the canvas with a colorful surface and a more painterly treatment than the hard-edge style of most of his later works.

Above: Paul Cézanne, Les joueurs des cartes

In Nord – Sud, the literary newspaper of that name appears in the still life, a compositional device common in cubist compositions, but also a reference to the literary and avant-garde interests of the painter.

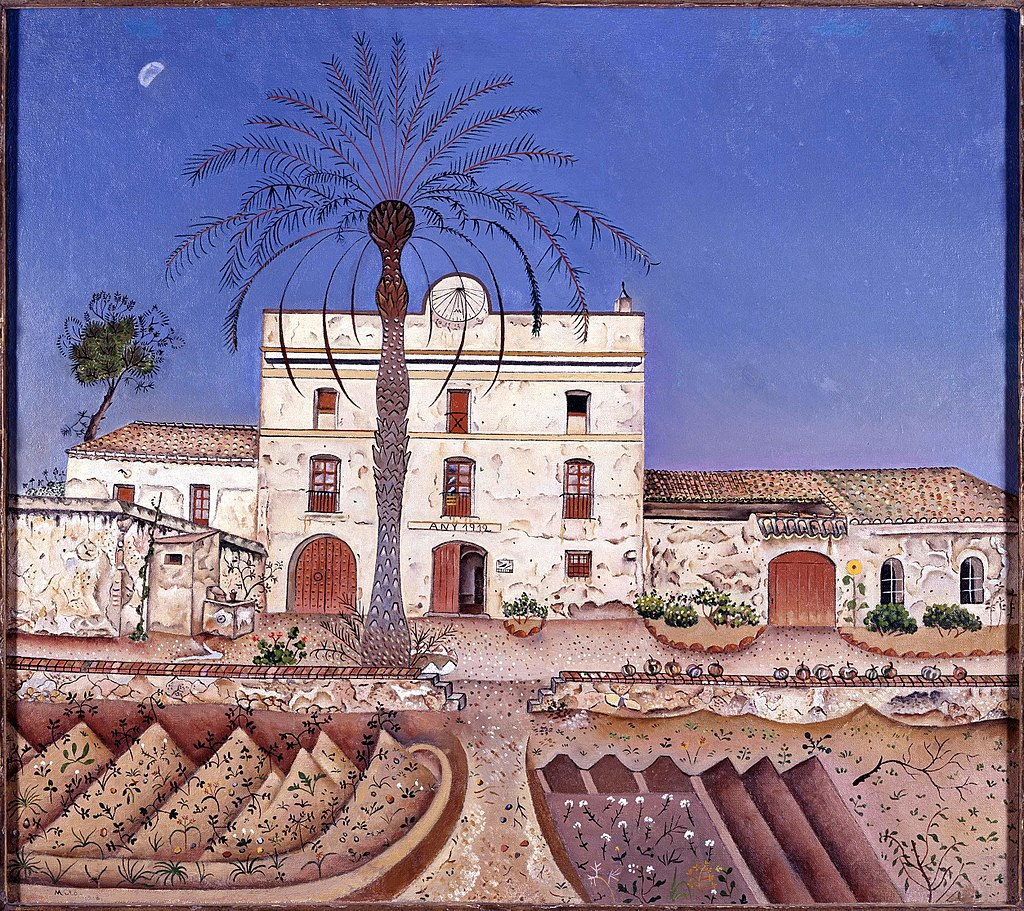

A few years after Miró’s 1918 Barcelona solo exhibition, he settled in Paris where he finished a number of paintings that he had begun on his parents’ summer home and farm in Mont-Roig del Camp.

Above: The church of Sant Miquel de Mont-Roig, Catalonia, Spain

One such painting, The Farm, showed a transition to a more individual style of painting and certain nationalistic qualities.

Above: Joan Miró, The Farm

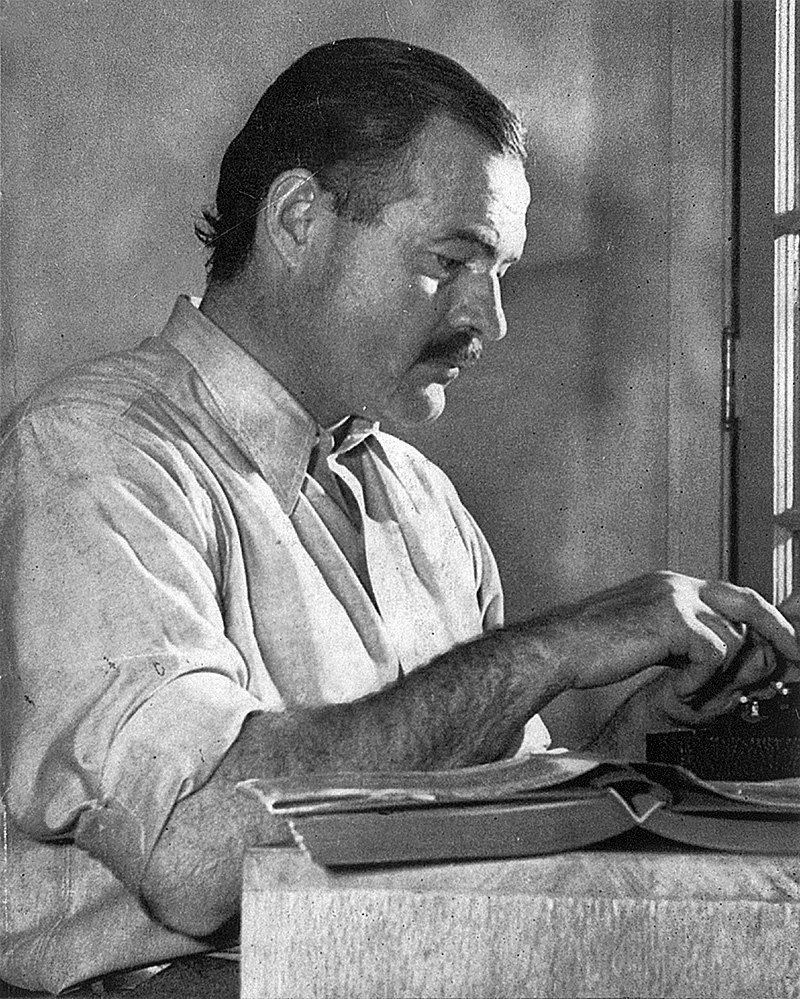

Ernest Hemingway, who later purchased the piece, described it by saying:

“It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there.

No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things.”

Above: American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961)

Miró annually returned to Mont-Roig and developed a symbolism and nationalism that would stick with him throughout his career.

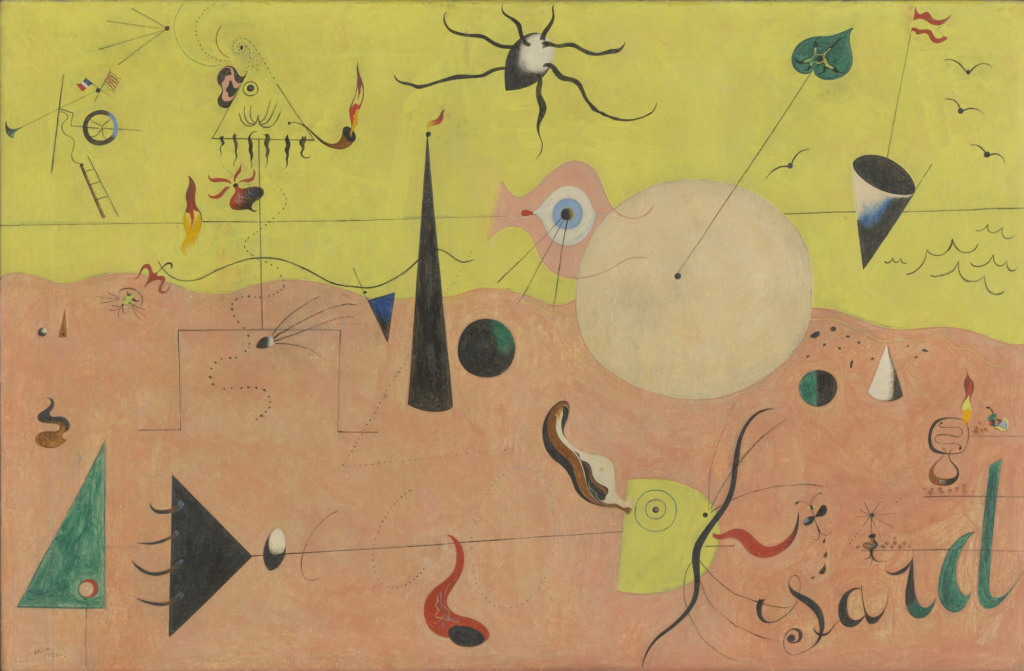

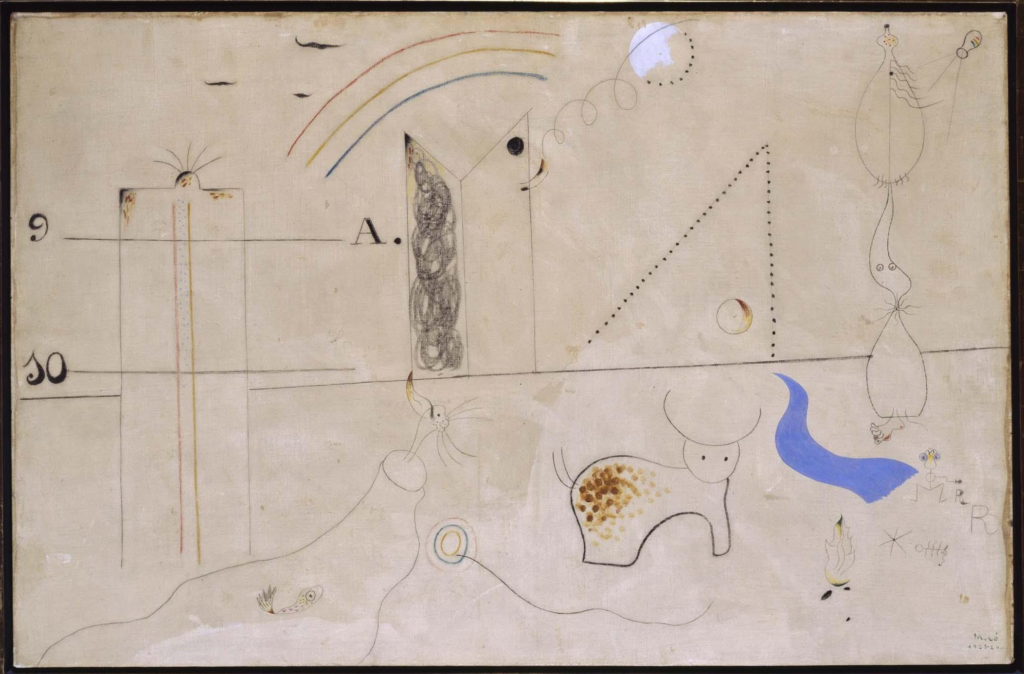

Two of Miró’s first works classified as Surrealist, Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) and The Tilled Field, employ the symbolic language that was to dominate the art of the next decade.

Above: Joan Miró, The Hunter

In Paris, under the influence of poets and writers, he developed his unique style:

Organic forms and flattened picture planes drawn with a sharp line.

Generally thought of as a Surrealist because of his interest in automatism and the use of sexual symbols (for example, ovoids with wavy lines emanating from them), Miró’s style was influenced in varying degrees by Surrealism and Dada, yet he rejected membership in any artistic movement in the interwar European years.

Above: Joan Miró, La casa de la palmera

André Breton described him as “the most Surrealist of us all“.

Above: French writer André Breton (1896 – 1966)

Miró confessed to creating one of his most famous works, Harlequin’s Carnival, under similar circumstances:

How did I think up my drawings and my ideas for painting?

Well I’d come home to my Paris studio in Rue Blomet at night, I’d go to bed, and sometimes I hadn’t any supper.

I saw things and I jotted them down in a notebook.

I saw shapes on the ceiling.“

Above: Joan Miró, Harlequin’s Carnival

Miró’s surrealist origins evolved out of “repression” much like all Spanish surrealist and magic realist work, especially because of his Catalan ethnicity, which was subject to special persecution by the Franco regime.

He drew on Catalan folk art such as siurells, which he claimed to “observe constantly“.

Above: Joan Miró, Horse, pipe and red flower

Also, Joan Miró was well aware of Haitian Voodoo art and Cuban Santería religion through his travels before going into exile.

This led to his signature style of art making.

Above: Joan Miró, Carrer de Pedralbes

Starting in 1920, Miró developed a very precise style, picking out every element in isolation and detail and arranging them in deliberate composition.

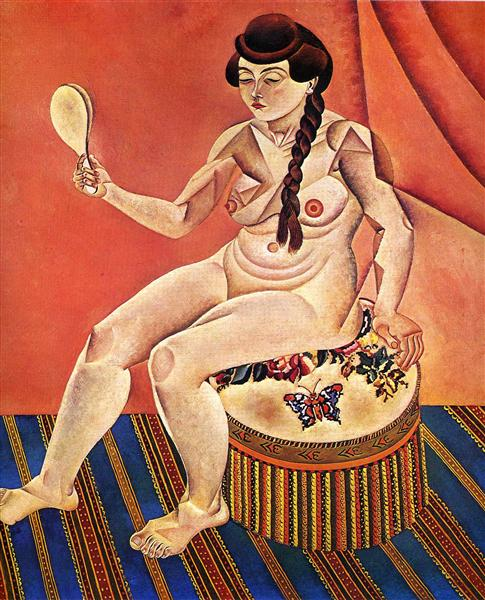

Above: Joan Miró, Nude with a mirror

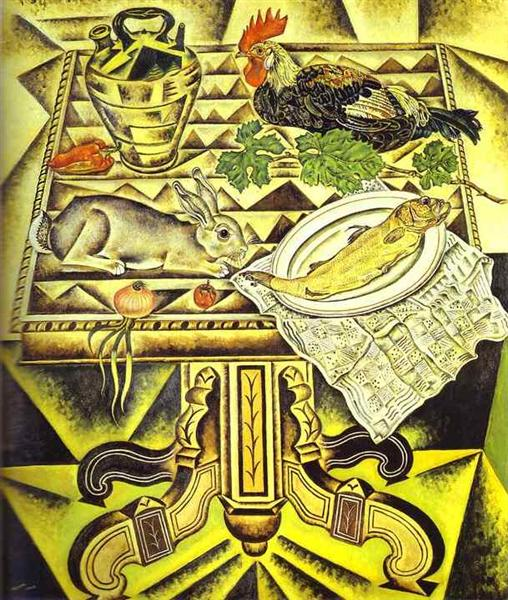

These works, including House with Palm Tree (1918), Nude with a Mirror (1919), Horse, Pipe and Red Flower (1920), and The Table – Still Life with Rabbit (1920), show the clear influence of Cubism, although in a restrained way, being applied to only a portion of the subject.

Above: Joan Miró, The table: Still life with rabbit

For example, The Farmer’s Wife (1923), is realistic, but some sections are stylized or deformed, such as the treatment of the woman’s feet, which are enlarged and flattened.

Above: Joan Miró, The farmer’s wife

The culmination of this style was The Farm (1922).

The rural Catalan scene it depicts is augmented by an avant-garde French newspaper in the center, showing Miró sees this work transformed by the Modernist theories he had been exposed to in Paris.

The concentration on each element as equally important was a key step towards generating a pictorial sign for each element.

The background is rendered in flat or patterned in simple areas, highlighting the separation of figure and ground, which would become important in his mature style.

Miró made many attempts to promote this work, but his surrealist colleagues found it too realistic and apparently conventional, and so he soon turned to a more explicitly surrealist approach.

Above: Joan Miró, The Farm

Josep Dalmau arranged Miró’s first Parisian solo exhibition, at Galerie la Licorne in 1921.

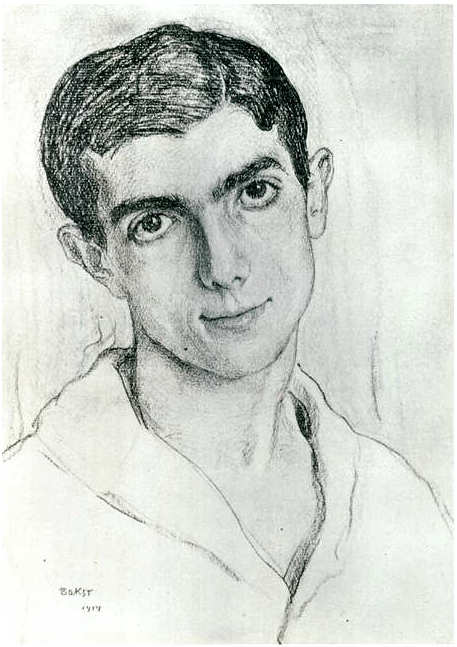

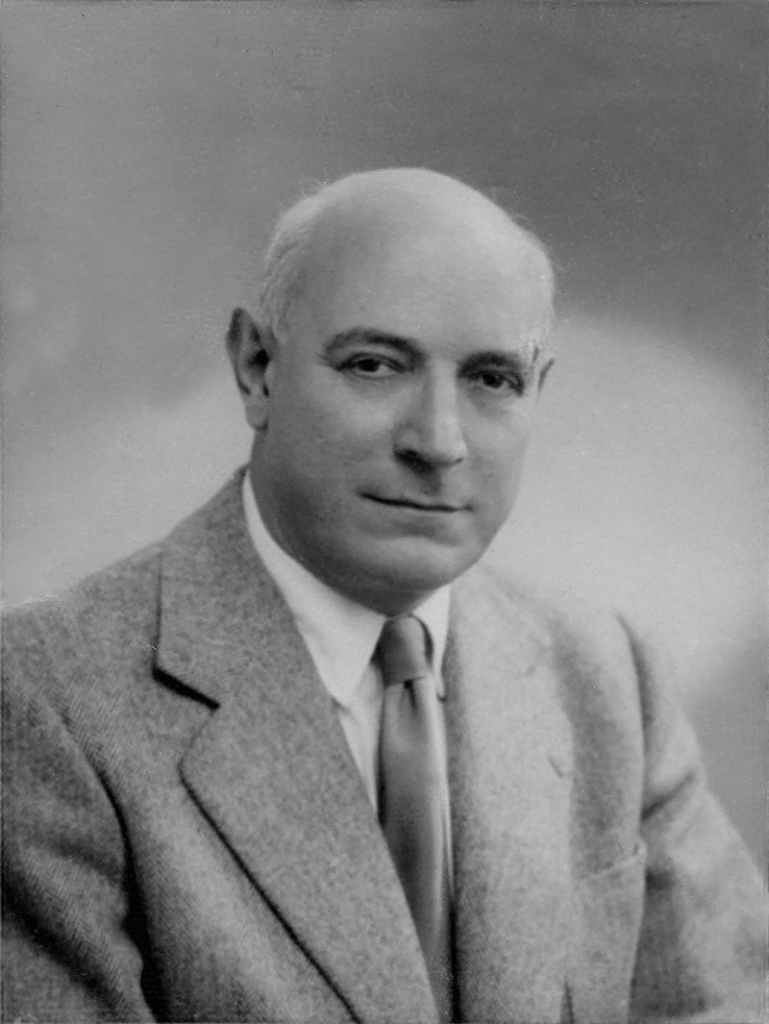

Above: Spanish painter Josep Dalmau i Rafel (1867 – 1936)

In 1922, Miró explored abstracted, strongly colored surrealism in at least one painting.

From the summer of 1923 in Mont Roig, Miró began a key set of paintings where abstracted pictorial signs, rather than the realistic representations used in The Farm, are predominant.

In The Tilled Field, Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) and Pastoral (1924), these flat shapes and lines (mostly black or strongly coloured) suggest the subjects, sometimes quite cryptically.

For Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), Miró represents the hunter with a combination of signs: a triangle for the head, curved lines for the moustache, angular lines for the body.

So encoded is this work that at a later time Miró provided a precise explanation of the signs used.

Above: Joan Miró, Pastoral

In 1924, Miró joined the Surrealist group.

The already symbolic and poetic nature of Miró’s work, as well as the dualities and contradictions inherent to it, fit well within the context of dream-like automatism espoused by the group.

Much of Miró’s work lost the cluttered chaotic lack of focus that had defined his work thus far.

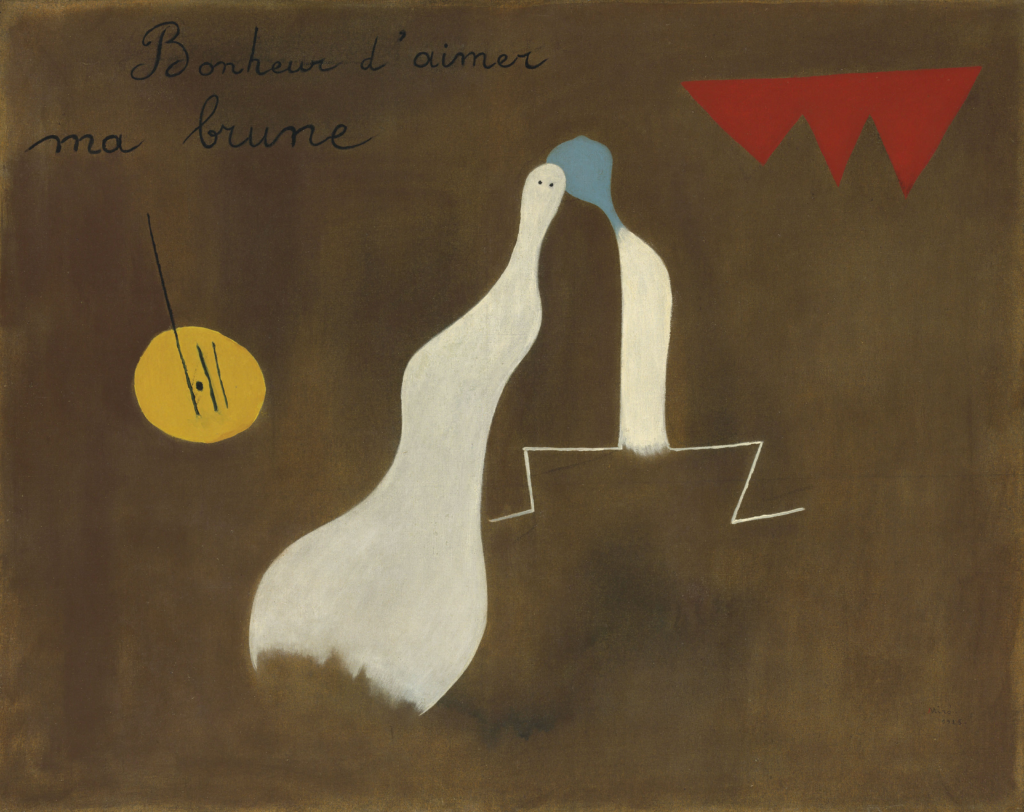

Above: Joan Miró, The Happiness of Loving My Brunette

He experimented with collage and the process of painting within his work so as to reject the framing that traditional painting provided.

This antagonistic attitude towards painting manifested itself when Miró referred to his work in 1924 ambiguously as “x” in a letter to poet friend Michel Leiris.

The paintings that came out of this period were eventually dubbed Miró’s dream paintings.

Above: French writer Michel Leiris (1901 – 1990)

Miró did not completely abandon subject matter, though.

Despite the Surrealist automatic techniques that he employed extensively in the 1920s, sketches show that his work was often the result of a methodical process.

Miró’s work rarely dipped into non-objectivity, maintaining a symbolic, schematic language.

This was perhaps most prominent in the repeated Head of a Catalan Peasant series of 1924 to 1925.

Above: Joan Miró, Head of a Catalan Peasant

In 1926, he collaborated with Max Ernst on designs for ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

Above: Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872 – 1929)

Through the mid-1920s Miró developed the pictorial sign language which would be central throughout the rest of his career.

In Harlequin’s Carnival (1924–25), there is a clear continuation of the line begun with The Tilled Field.

But in subsequent works, such as The Happiness of Loving My Brunette (1925) and Painting (Fratellini) (1927), there are far fewer foreground figures, and those that remain are simplified.

Above: Joan Miró, Painting (Fratellini)

Soon after, Miró also began his Spanish Dancer series of works.

These simple collages, were like a conceptual counterpoint to his paintings.

In Spanish Dancer (1928) he combines a cork, a feather and a hatpin onto a blank sheet of paper.

Above: Joan Miró, Spanish Dancer

Miró returned to a more representational form of painting with The Dutch Interiors of 1928.

Crafted after works by Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh and Jan Steen seen as postcard reproductions, the paintings reveal the influence of a trip to Holland taken by the artist.

These paintings share more in common with Tilled Field or Harlequin’s Carnival than with the minimalistic dream paintings produced a few years earlier.

Above: Joan Miró, Dutch Interior

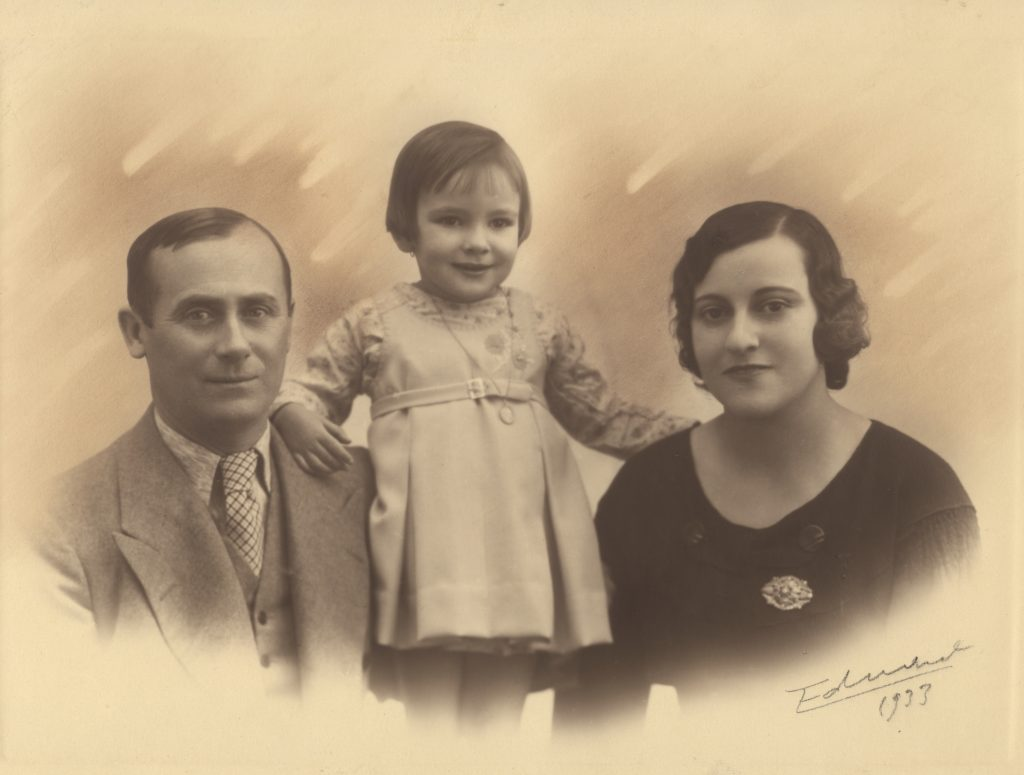

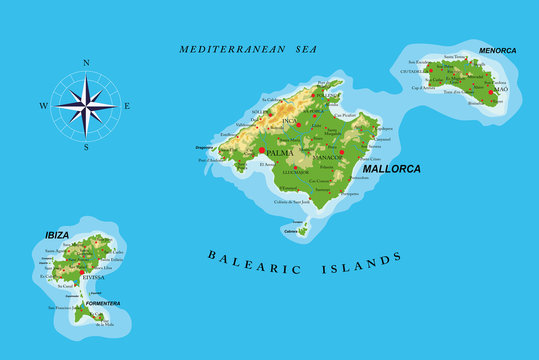

Miró married Pilar Juncosa in Palma (Majorca) on 12 October 1929.

Their daughter, María Dolores Miró, was born on 17 July 1930.

Above: Joan, Maria and Pilar Miró

In 1931, Pierre Matisse opened an art gallery in New York City.

The Pierre Matisse Gallery (which existed until Matisse’s death in 1989) became an influential part of the Modern art movement in America.

From the outset Matisse represented Joan Miró and introduced his work to the US market by frequently exhibiting Miró’s work in New York.

Above: Joan Miró and French art dealer Pierre Matisse (1900 – 1989)

In 1932 he created a scenic design for Massine’s ballet Jeux d’enfants at Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo.

Above: Russian dancer Leonide Massine (1895 – 1979)

Until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), Miró habitually returned to Spain in the summers.

Once the War began, he was unable to return home.

Above: Scene from the Spanish Civil War

Unlike many of his surrealist contemporaries, Miró had previously preferred to stay away from explicitly political commentary in his work.

Though a sense of Catalan nationalism pervaded his earliest surreal landscapes and Head of a Catalan Peasant, it was not until Spain’s Republican government commissioned him to paint the mural The Reaper, for the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exhibition, that Miró’s work took on a politically charged meaning.

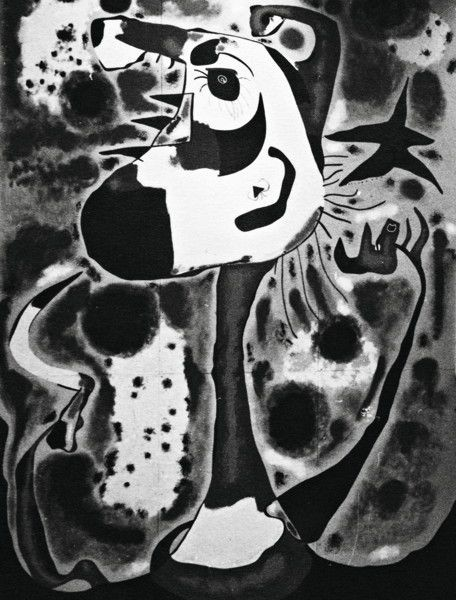

Above: Joan Miró, The Reaper

In 1939, with Germany’s invasion of France looming, Miró relocated to Varengeville in Normandy.

Above: Varengeville sur Mer, Normandy, France

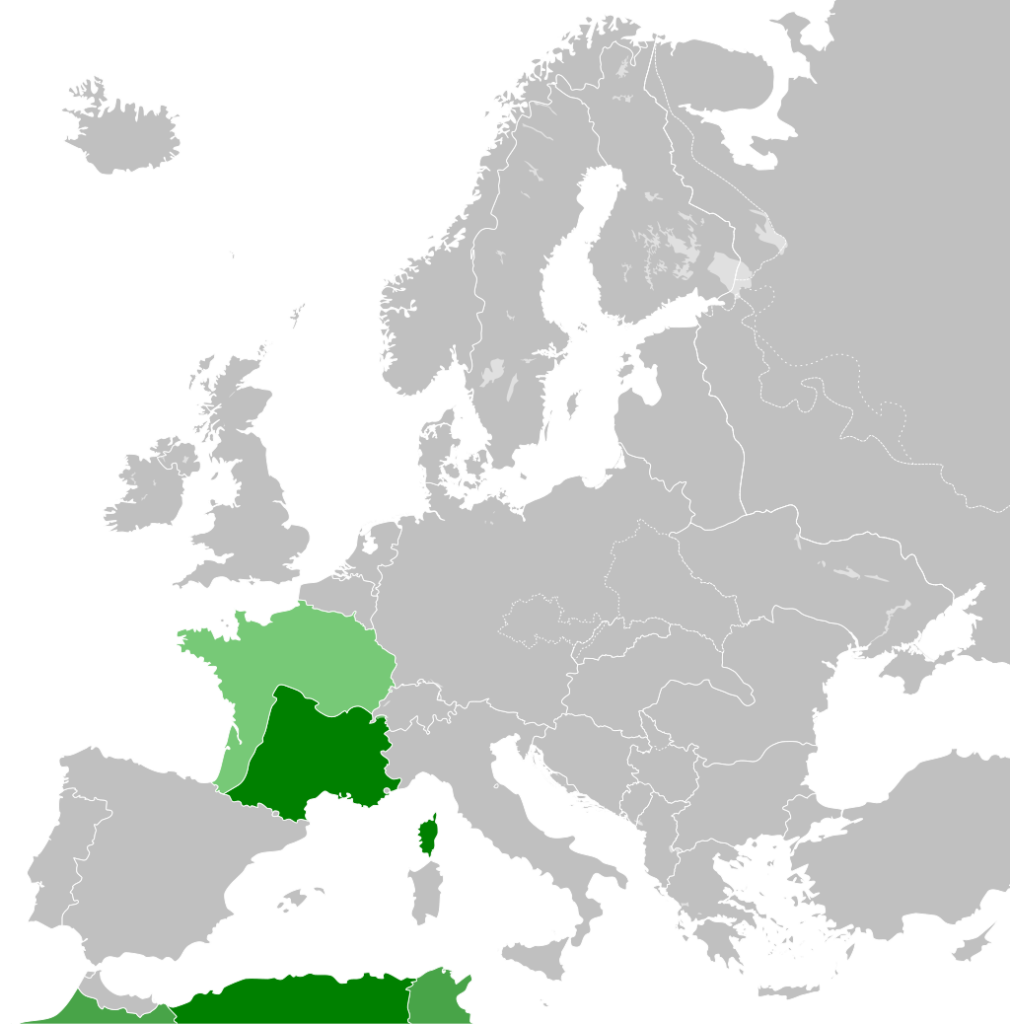

On 20 May of the following year, as Germans invaded Paris, he narrowly fled to Spain (now controlled by Francisco Franco) for the duration of the Vichy Regime’s rule.

Above: Germans invade Paris (1940)

Above: Spanish dictator Francisco Franco (1892 – 1975)

Above: Symbol of Vichy France (État français) (1940 – 1944)

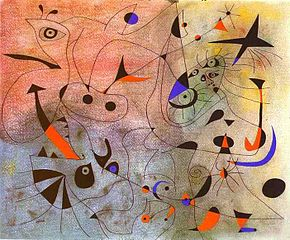

In Varengeville, Palma, and Mont Roig, between 1940 and 1941, Miró created the 23 gouache (opaque watercolor) series Constellations.

Revolving around celestial symbolism, Constellations earned the artist praise from André Breton, who 17 years later wrote a series of poems, named after and inspired by Miró’s series.

Features of this work revealed a shifting focus to the subjects of women, birds, and the moon, which would dominate his iconography for much of the rest of his career.

Above: Joan Miró, Morning Star

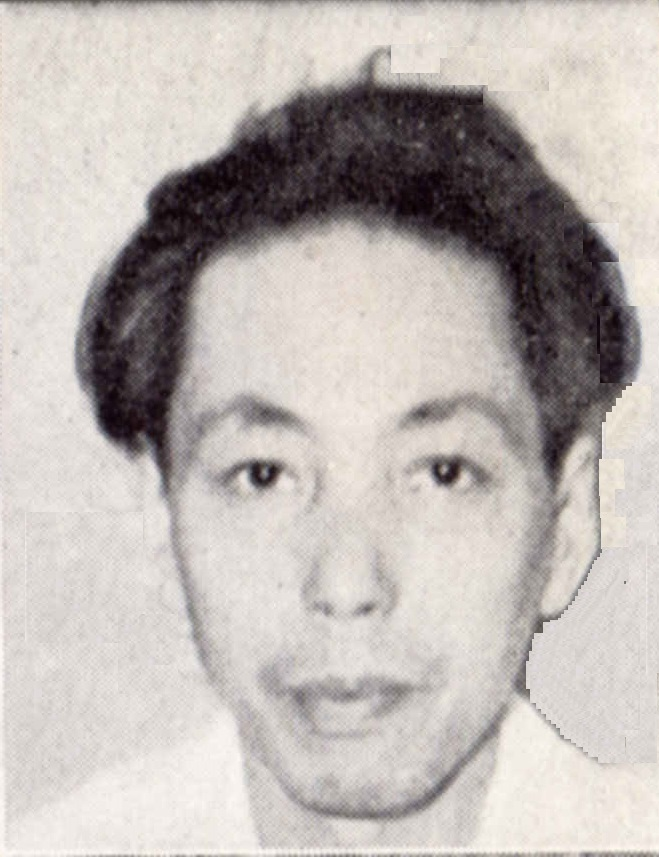

Shuzo Takiguchi published the first monograph on Miró in 1940.

Above: Japanese art critic Shūzō Takiguchi (1903 – 1979)

In 1948 – 1949 Miró lived in Barcelona and made frequent visits to Paris to work on printing techniques at the Mourlot Studios and the Atelier Lacourière.

He developed a close relationship with Fernand Mourlot and that resulted in the production of over one thousand different lithographic editions.

Above: French director Fernand Mourlot (1895 – 1988)

Miró created a series of sculptures and ceramics for the garden of the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, which was completed in 1964.

Above: Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul de Vence, France

In 1974, Miró created a tapestry for the World Trade Center in New York City together with the Catalan artist Josep Royo.

He had initially refused to do a tapestry, then he learned the craft from Royo and the two artists produced several works together.

His World Trade Center Tapestry was displayed at the building and was one of the most expensive works of art lost during the September 11 attacks.

Above: Joan Miró, World Trade Center Tapestry (1974 – 2001)

In 1977, Miró and Royo finished a tapestry to be exhibited in the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Above: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

In 1981, Miró’s The Sun, the Moon and One Star — later renamed Miró’s Chicago — was unveiled.

This large, mixed media sculpture is situated outdoors in the downtown Loop area of Chicago, across the street from another large public sculpture, the Chicago Picasso.

Above: Joan Miró, Chicago

Miró had created a bronze model of The Sun, the Moon and One Star in 1967.

The maquette now resides in the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Above: Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

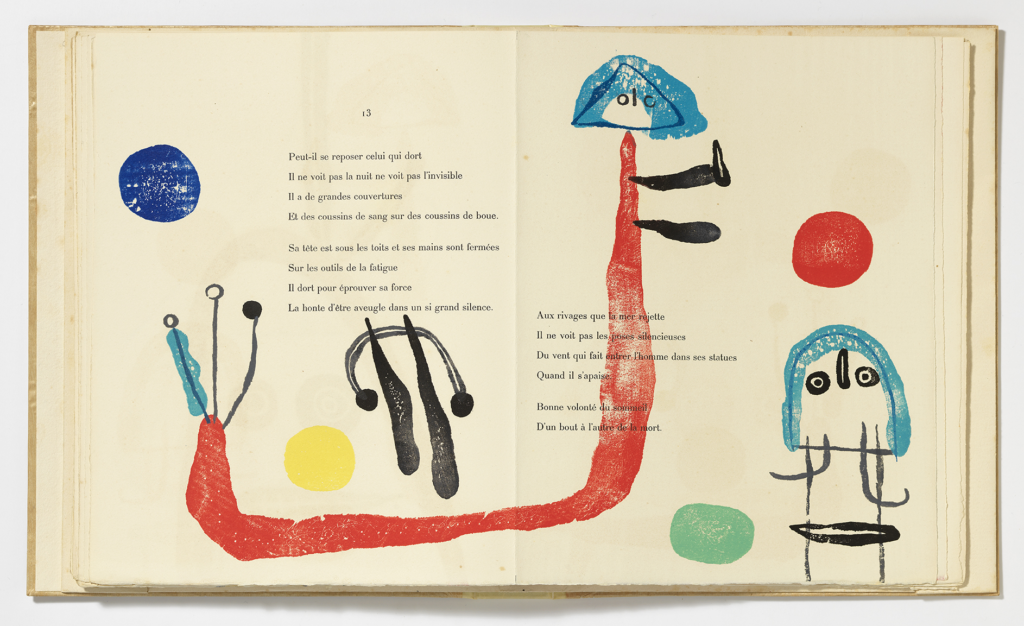

Miró created over 250 illustrated books.

These were known as Livres d’Artiste.

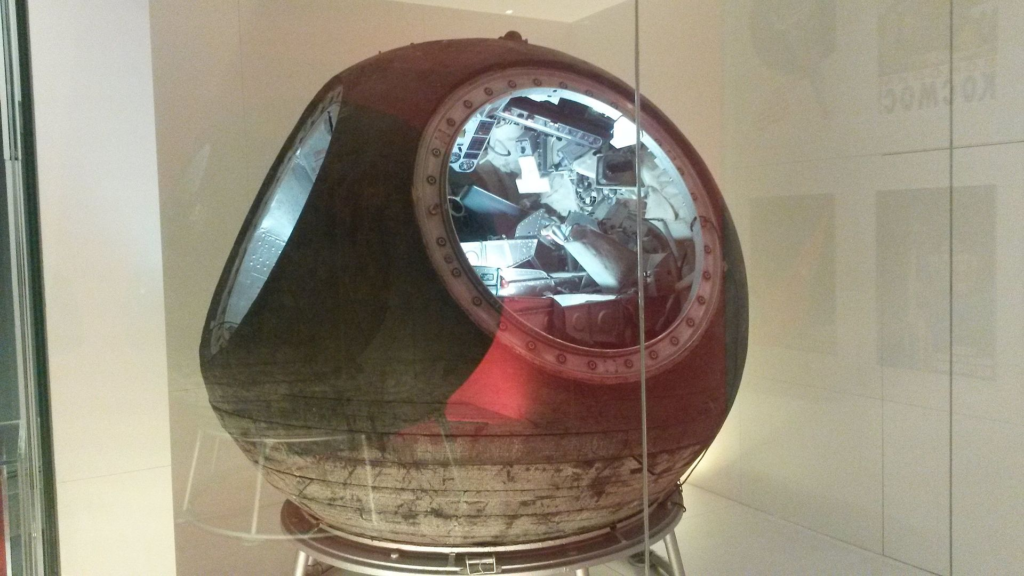

One such work was published in 1974, at the urging of the widow of the French poet Robert Desnos, titled Les pénalités de l’enfer ou les nouvelles Hébrides (“The Penalties of Hell or The New Hebrides“).

It was a set of 25 lithographs, five in black, and the others in colors.

Above: Joan Miró, Les pénalités de l’enfer ou les nouvelles Hébrides

In 2006, the book with these collected lithos was displayed in “Joan Miró, Illustrated Books” at the Vero Beach Museum of Art.

One critic described it as “an especially powerful set, not only for the rich imagery but also for the story behind the book’s creation.

The lithographs are long, narrow verticals, and while they feature Miró’s familiar shapes, there’s an unusual emphasis on texture.”

The critic continued:

“I was instantly attracted to these four prints, to an emotional lushness, that’s in contrast with the cool surfaces of so much of Miró’s work.

Their poignancy is even greater, I think, when you read how they came to be.”

Above: Vero Beach Museum of Art, Vero Beach, Florida, USA

The artist met and became friends with Desnos, perhaps the most beloved and influential surrealist writer, in 1925, and before long, they made plans to collaborate on a livre d’artiste.

Those plans were put on hold because of the Spanish Civil War and World War II.

Desnos’ bold criticism of the latter led to his imprisonment in the concentration camp of Auschwitz.

He died at age 45 shortly after his release in 1945.

Nearly three decades later, at the suggestion of Desnos’ widow, Miró set out to illustrate the poet’s manuscript.

It was his first work in prose, which was written in Morocco in 1922 but remained unpublished until this posthumous collaboration.

Above: French poet Robert Desnos (1900 – 1945)

Joan Miró was among the first artists to develop automatic drawing as a way to undo previous established techniques in painting, and thus, with André Masson, represented the beginning of Surrealism as an art movement.

However, Miró chose not to become an official member of the Surrealists to be free to experiment with other artistic styles without compromising his position within the group.

He pursued his own interests in the art world, ranging from automatic drawing and surrealism, to expressionism, Lyrical Abstraction, and Color Field painting.

Four-dimensional painting was a theoretical type of painting Miró proposed in which painting would transcend its two-dimensionality and even the three-dimensionality of sculpture.

Above: Joan Miró, Dona i Ocell

Miró’s oft-quoted interest in the assassination of painting is derived from a dislike of bourgeois art, which he believed was used as a way to promote propaganda and cultural identity among the wealthy.

Specifically, Miró responded to Cubism in this way, which by the time of his quote had become an established art form in France.

Above: Joan Miró, Moon Bird, Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, Spain

He is quoted as saying “I will break their guitar.”, referring to Picasso’s paintings, with the intent to attack the popularity and appropriation of Picasso’s art by politics.

The spectacle of the sky overwhelms me.

I’m overwhelmed when I see, in an immense sky, the crescent of the moon, or the sun.

There, in my pictures, tiny forms in huge empty spaces.

Empty spaces, empty horizons, empty plains – everything which is bare has always greatly impressed me.”

Joan Miró, 1958, quoted in Twentieth-Century Artists on Art

In an interview with biographer Walter Erben, Miró expressed his dislike for art critics, saying, they “are more concerned with being philosophers than anything else.

They form a preconceived opinion, then they look at the work of art.

Painting merely serves as a cloak in which to wrap their emaciated philosophical systems.“

In the final decades of his life Miró accelerated his work in different media, producing hundreds of ceramics, including the Wall of the Moon and Wall of the Sun at the UNESCO building in Paris.

He also made temporary window paintings (on glass) for an exhibit.

In the last years of his life Miró wrote his most radical and least known ideas, exploring the possibilities of gas sculpture and four-dimensional painting.

The artist, who suffered from heart failure, died in his home in Palma (Majorca) on 25 December 1983 at age 90.

Above: Pilar and Joan Miró Foundation, Palma, Mallorca, Spain

He was later interred in the Montjuïc Cemetery in Barcelona.

Above: Montijuic Cemetery, Barcelona, Spain

Miró had many episodes of depression throughout his life.

He experienced his first depression when he was 18 in 1911.

Miró said:

“I was demoralized and suffered from a serious depression.

I fell really ill and stayed three months in bed.“

Above: “Les Fusains“: 22, rue Tourlaque, 18th arrondissement of Paris where Miró settled in 1927

He used painting as a way of dealing with depression.

It supposedly made him calmer and his thoughts less dark.

Miró said that without painting he became “very depressed, gloomy and I get ‘black ideas’.

I do not know what to do with myself.”

Above: Joan Miró, Grande Maternité, San Francisco, California, USA

His mental state is visible in his painting Carnival of the Harlequin.

He tried to paint the chaos he experienced in his mind, the desperation of wanting to leave that chaos behind and the pain created because of that.

Miró painted the symbol of the ladder here which is also visible in multiple other paintings after this painting.

It is supposed to symbolize escaping.

The relation between creativity and mental illness is very well studied.

It has been argued that creative people have a higher chance of suffering from a manic depressive illness or schizophrenia, as well as higher chance of transmitting this genetically.

Even though we know Miró suffered from episodic depression, it is uncertain whether he also experienced manic episodes, which is often referred to as bipolar disorder.

Above: Joan Miró, Harlequin’s Carnival

Thursday 20 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

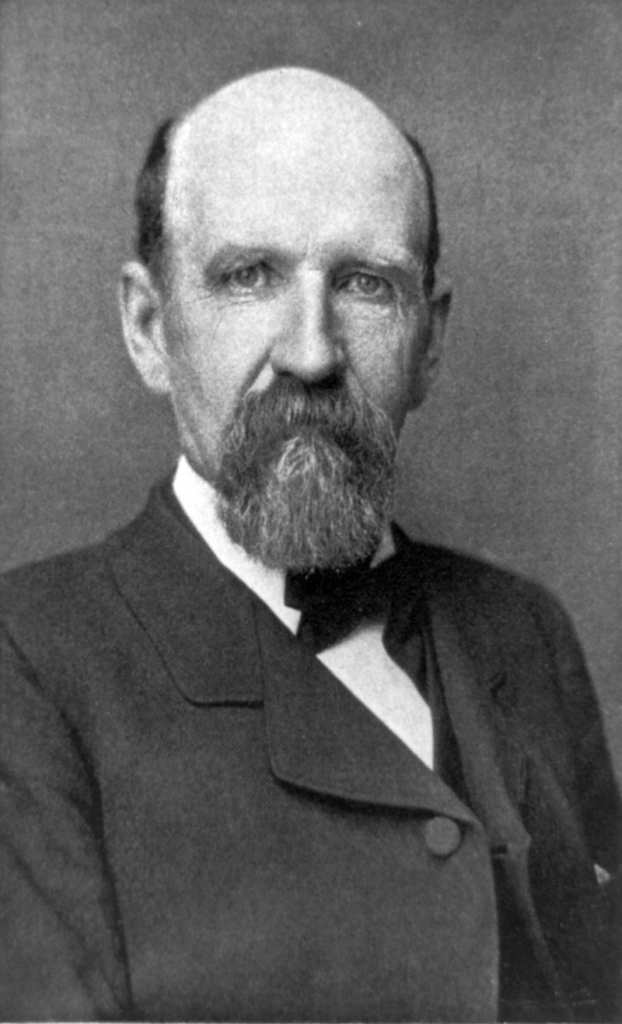

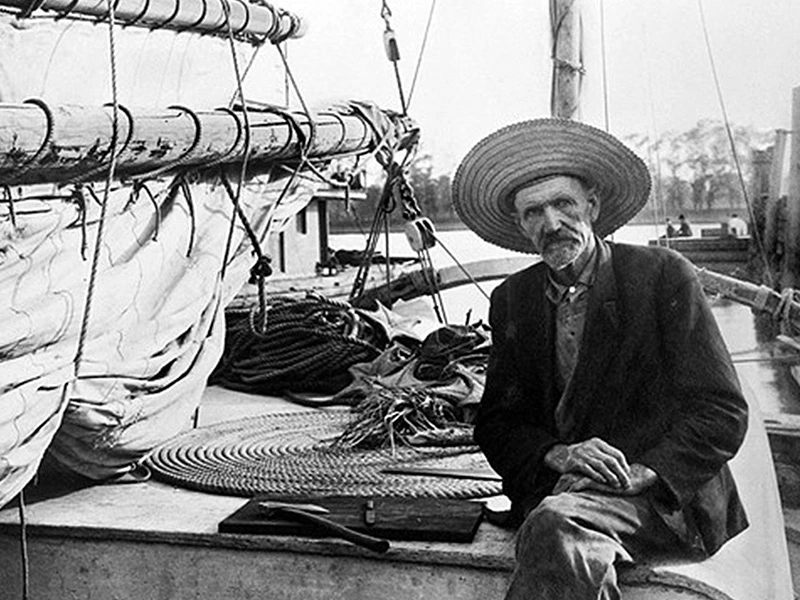

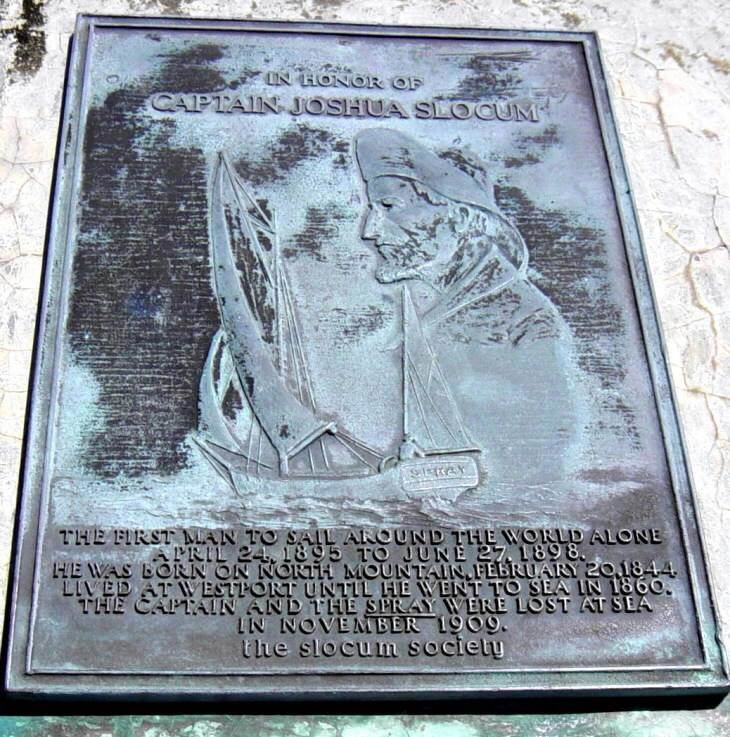

Joshua Slocum (February 20, 1844 – on or shortly after November 14, 1909) was the first person to sail single-handedly around the world.

He was a Nova Scotian-born, naturalized American seaman and adventurer, and a noted writer.

Above: Joshua Slocum

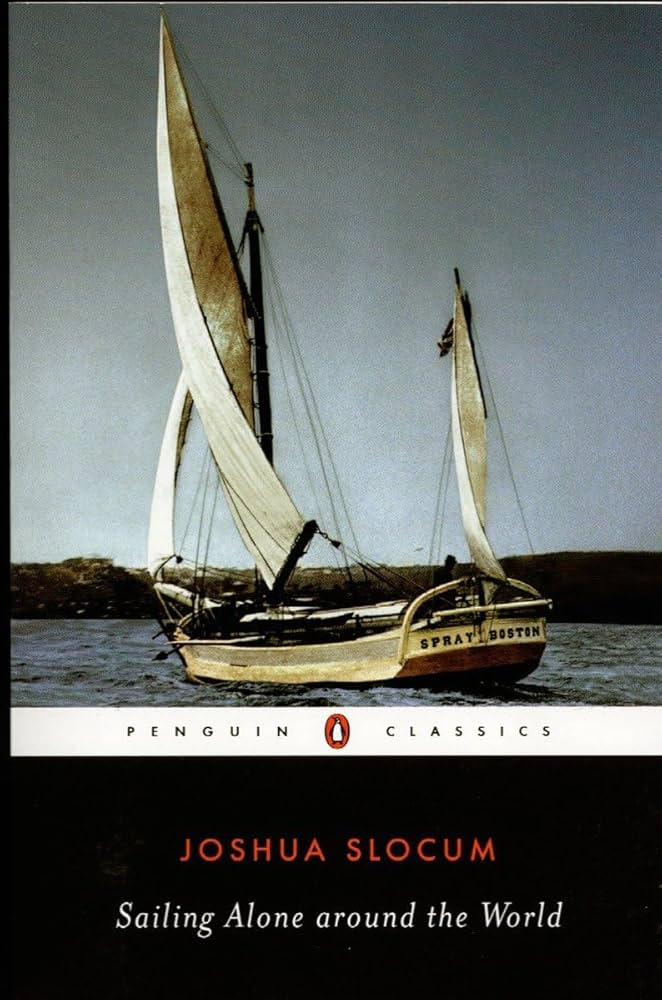

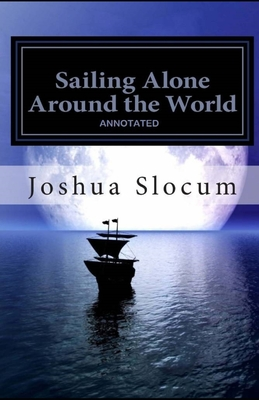

In 1900 he wrote a book about his journey, Sailing Alone Around the World, which became an international best-seller.

He disappeared in November 1909 while aboard his boat, the Spray.

Above: The Spray

Joshua Slocum was born in Mount Hanley, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia (officially recorded as Wilmot Station), a community on the North Mountain within sight of the Bay of Fundy.

Above: Mount Hanley, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada

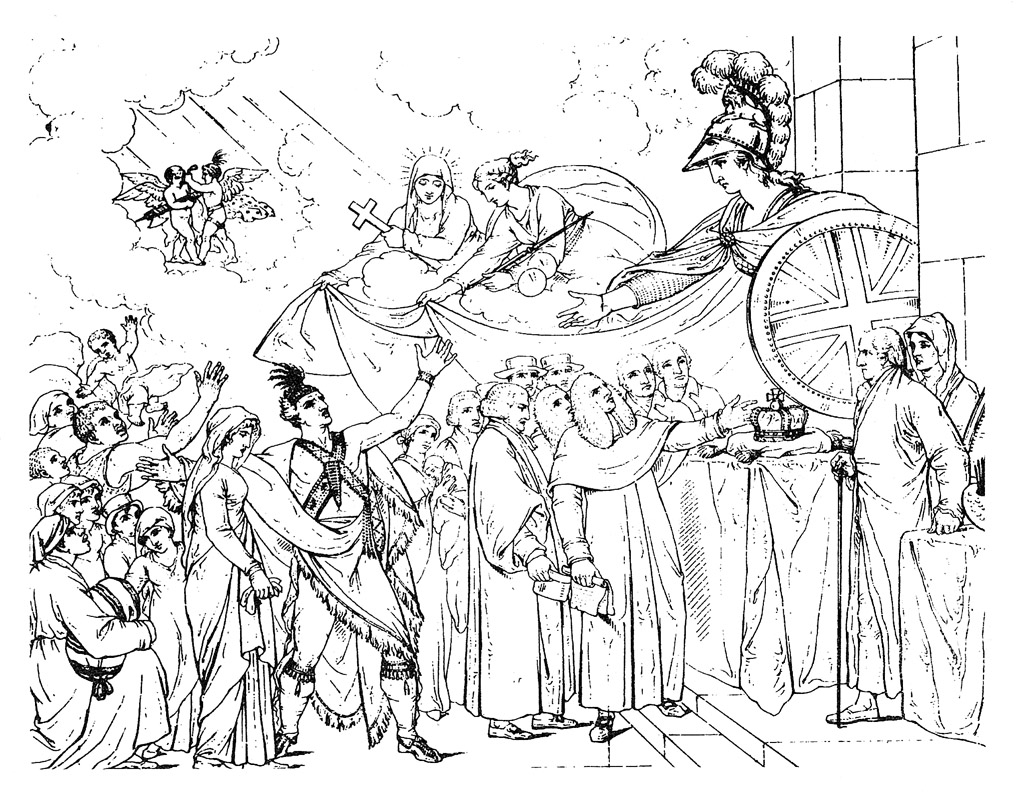

The 5th of 11 children of John Slocomb and Sarah Jane Slocombe née Southern, Joshua descended, on his father’s side, from a Quaker known as “John the Exile“, who left the US shortly after 1780 because of his opposition to the American War for Independence.

As part of the Loyalist migration to Nova Scotia, the Slocombes were granted 500 acres (2.0 km2) of farmland in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis County.

Above: Reception of the American Loyalists by Great Britain (1783)

Joshua Slocum was born in the family’s farmhouse in Mount Hanley and learned to read and write at the nearby Mount Hanley School.

Above: Slocum’s childhood school, now the Mount Hanley Schoolhouse Museum

His earliest ventures on the water were made on coastal schooners operating out of the small ports such as Port George and Cottage Cove near Mount Hanley along the Bay of Fundy.

When Joshua was eight years old, the Slocomb family (Joshua changed the spelling of his last name later in his life) moved from Mount Hanley to Brier Island in Digby County, at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy.

Slocum’s maternal grandfather was the keeper of the lighthouse at Southwest Point there.

Above: Lighthouse, Southwest Point, Brier Island, Nova Scotia

His father, a stern man and strict disciplinarian, took up making leather boots for the local fishermen, and Joshua helped in the shop.

However, the boy found the scent of salt air much more alluring than the smell of shoe leather.

He yearned for a life of adventure at sea, away from his demanding father and his increasingly chaotic life at home among so many brothers and sisters.

He made several attempts to run away from home, finally succeeding, at age 14, by hiring on as a cabin boy and cook on a fishing schooner, but he soon returned home.

In 1860, after the birth of the 11th Slocombe child and the subsequent death of his kindly mother, Joshua, then 16, left home for good.

He and a friend signed on at Halifax as ordinary seamen on a merchant ship bound for Dublin, Ireland.

Above: Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Above: Dublin, Ireland

From Dublin, he crossed to Liverpool to become an ordinary seaman on the British merchant ship Tangier (also recorded as Tanjore), bound for China.

Above: Liverpool, Merseyside, England

During two years as a seaman he rounded Cape Horn twice, landed at Jakarta in the Dutch East Indies, and visited the Maluku Islands, Manila, Hong Kong, Ho Chi Minh City, Singapore, and San Francisco.

Above: Cape Horn, South Africa

Above: Jakarta, Indonesia

Above: Manila, Philippines

Above: Hong Kong, China

Above: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Above: Flag of Singapore

Above: San Francisco, California, USA

While at sea, he studied for the Board of Trade examination.

At the age of 18, he received his certificate as a fully qualified Second Mate.

Slocum quickly rose through the ranks to become a Chief Mate on British ships transporting coal and grain between the British Isles and San Francisco.

In 1865, he settled in San Francisco, became an American citizen, and, after a period spent salmon fishing and fur trading in the Oregon Territory of the northwest, he returned to the sea to pilot a schooner in the coastal trade between San Francisco and Seattle.

Above: State flag of Oregon, USA

Above: Seattle, Washington, USA

His first blue-water command, in 1869, was the barque Washington, which he took across the Pacific, from San Francisco to Australia, and home via Alaska.

Above: Flag of Australia

Above: State flag of Alaska, USA

He sailed for 13 years out of the port of San Francisco, transporting mixed cargo to China, Australia, the Maluku Islands, and Japan.

Above: Flag of China

Above: Flag of Japan

Between 1869 and 1889 he was the master of eight vessels, the first four of which (the Washington, the Constitution, the Benjamin Aymar and the Amethyst) he commanded in the employ of others.

Later, there would be four others that he himself owned, in whole or in part.

On 9 January 1871, Slocum and the Constitution put in at Sydney.

Above: Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

There he met, courted, and married Virginia Albertina Walker.

They were married on 31 January 1871.

The couple left Sydney on the Constitution the following day.

Miss Walker, quite coincidentally, was an American whose New York family had migrated west to California at the time of the 1849 gold rush and eventually continued on, by ship, to settle in Australia.

She sailed with Slocum, and, over the next 13 years, the couple had seven children, all born at sea or foreign ports.

Four children, sons Victor, Benjamin Aymar, and James Garfield, and daughter Jessie, survived to adulthood.

Above: Virginia Albertina Walker

In Alaska, the Washington was wrecked when she dragged her anchor during a gale, ran ashore, and broke up.

Slocum, however, at considerable risk to himself, managed to save his wife, the crew, and much of the cargo, bringing all back to port safely in the ship’s open boats.

The owners of the shipping company that had employed Slocum were so impressed by this feat of ingenuity and leadership, they gave him the command of the Constitution which he sailed to Hawaii and the west coast of Mexico.

Above: State flag of Alaska, USA

Above: Flag of Mexico

His next command was the Benjamin Aymar, a merchant vessel in the South Seas trade.

However, the owner, strapped for cash, sold the vessel out from under Slocum.

He and Virginia found themselves stranded in the Philippines without a ship.

Above: Flag of the Philippines

While in the Philippines, in 1874, under a commission from a British architect, Slocum organized native workers to build a 150-ton steamer in the shipyard at Subic Bay.

Above: A transport steamer

Above: Subic Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines

In partial payment for the work, he was given the ninety-ton schooner, Pato (Spanish: “duck“), the first ship he could call his own.

Ownership of the Pato afforded Slocum the kind of freedom and autonomy he had never previously experienced.

Hiring a crew, he contracted to deliver a cargo to Vancouver in British Columbia.

Above: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Thereafter, he used the Pato as a general freight carrier along the west coast of North America and in voyages back and forth between San Francisco and Hawaii.

During this period, Slocum also fulfilled a long-held ambition to become a writer.

He became a temporary correspondent for the San Francisco Bee.

The Slocums sold the Pato in Honolulu in the spring of 1878.

Above: Honolulu, Oahu Island, Hawaii, USA

Returning to San Francisco, they purchased the Amethyst.

He worked this ship until 23 June 1881.

The Slocums next bought a third share in the Northern Light 2.

This large clipper was 233 feet in length, 44 feet beam, 28 feet in the hold.

It was capable of carrying 2,000 tons on three decks.

Although Joshua Slocum called this ship “my best command“, it was a command plagued with mutinies and mechanical problems.

Under troubling legal circumstances (caused by his alleged treatment of the chief mutineer) he sold his share in the Northern Light 2 in 1883.

The Slocum family continued on their next ship, the 326-ton Aquidneck.

In 1884, Slocum’s wife Virginia became ill aboard the Aquidneck in Buenos Aires and died.

Above: Buenos Aires, Argentina

After sailing to Massachusetts, Slocum left his three youngest children, Benjamin Aymar, Jessie, and Garfield in the care of his sisters.

Above: State flag of Massachusetts, USA

His oldest son Victor continued as his first mate.

In 1886, at age 42, Slocum married his 24-year-old cousin, Henrietta “Hettie” Elliott.

The Slocum family, with the exception of Jessie and Benjamin Aymar, again took to the sea aboard the Aquidneck, bound for Montevideo, Uruguay.

Above: Montevideo, Uruguay

Slocum’s second wife would find life at sea much less appealing than his first.

A few days into Henrietta’s first voyage, the Aquidneck sailed through a hurricane.

By the end of this first year, the crew had contracted cholera, and they were quarantined for six months.

Later, Slocum was forced to defend his ship from pirates, one of whom he shot and killed; following which he was tried and acquitted of murder.

Next, the Aquidneck was infected with smallpox, leading to the death of three of the crew.

Disinfecting of the ship was performed at considerable cost.

Shortly afterward, near the end of 1887, the Aquidneck was wrecked in southern Brazil.

Above: Flag of Brazil

After being stranded in Brazil with his wife and sons Garfield and Victor, he started building a boat that could sail them home.

He used local materials, salvaged materials from the Aquidneck, and worked with local workers.

The boat was launched on 13 May 1888, the very day slavery was abolished in Brazil, and therefore the ship was given the name Liberdade, the Portuguese word for freedom.

It was an unusual 35-foot (11 m) junk-rigged design which he described as “half Cape Ann dory and half Japanese sampan“.

He and his family began their voyage back to the US, his son Victor (15) being the mate.

After 55 days at sea and 5,510 miles, the Slocums reached Cape Roman, South Carolina.

Above: State flag of South Carolina, USA

They continued inland to Washington DC for the winter and finally reaching Boston via New York in 1889.

Above: National Mall/Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC, USA

Above: Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Above: New York City, New York, USA

This was the last time Henrietta sailed with the family.

In 1890, Slocum published his accounts of these adventures in Voyage of the Liberdade.

In the northern winter of 1893 – 1894, Slocum undertook what he described as, at that time, being “the hardest voyage that I have ever made, without any exception at all“.

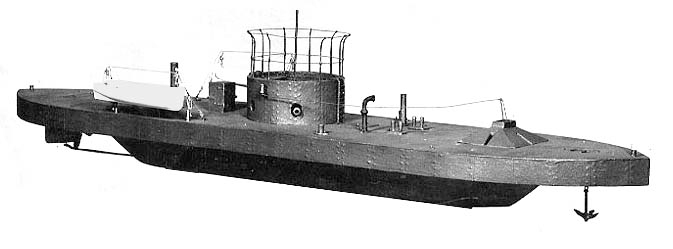

It involved delivering the steam-powered torpedo boat Destroyer from the east coast of the United States to Brazil.

Destroyer was a ship 130 feet (40 m) in length, conceived by the Swedish-American inventor and mechanical engineer John Ericsson, and intended for the defence of harbours and coastal waters.

Above: John Ericsson (1803 – 1889)

Equipped in the early 1880s, with sloping armor plate and a bow-mounted submarine gun, it was an evolution of the Monitor warship type of the American Civil War.

Above: USS Monitor, the first Monitor (1861)

Destroyer was intended to fire an early form of torpedo at an opposing ship from a range of 300 feet (91 m), and was a “vessel of war partially armored to attack bows-on at short range“.

Despite the loss of the Aquidneck, and the privations of his family’s voyage in the self-built Liberdade, Slocum retained a fondness for Brazil.

During 1893, Brazil was faced with a political crisis in Rio Grande do Sul, and an attempt at civil war that was intensified by the revolt of the country’s navy in September.

Above: (in red) Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

In this struggle the revolutionaries occupied Santa Catarina and Paraná, capturing Curitiba, but were eventually overthrown through their inability to obtain munitions of war.

An incident in this struggle was the death of Admiral Saldanha da Gama, one of the most brilliant officers of the Brazilian navy and one of the chiefs of the naval revolt of 1893 – 1894, who was killed in a skirmish on the Uruguayan border towards the end of the conflict.

Above: Brazilian Admiral Saldanha da Gama (1846 – 1895)

Above: A cannon and Brazilian troops in Rio de Janeiro in 1894. Photo taken during the blockade of the city by rebel warships.

The Brazilian Naval Revolts, or the Revoltas da Armada (in Portuguese), were armed mutinies promoted mainly by Admirals Custódio José de Melo (1840 – 1902) and Saldanha da Gama and their fleet of rebel Brazilian navy ships against the claimed unconstitutional staying in power of President Floriano Peixoto.

The US supported the incumbent government against the insurgents.

Slocum agreed to a request by the Brazilian government to deliver the Destroyer to Pernambuco, Brazil, with financial and vindictive motives.

As Slocum describes, his contract with the commander of government forces at Pernambuco was, “to go against the rebel fleet, and sink them all, if we could find them – big and little – for a handsome sum of gold“.

Above: (in red) Pernambuco, Brazil

Slocum also saw the possibility of getting even with the “arch rebel” Admiral Melo (of whom he writes as “Mello“):

“Confidentially:

I was burning to get a rake at Mello and his Aquideban.

He it was, who in that ship expelled my bark, the Aquidneck, from Ilha Grande some years ago, under the cowardly pretext that we might have sickness on board.

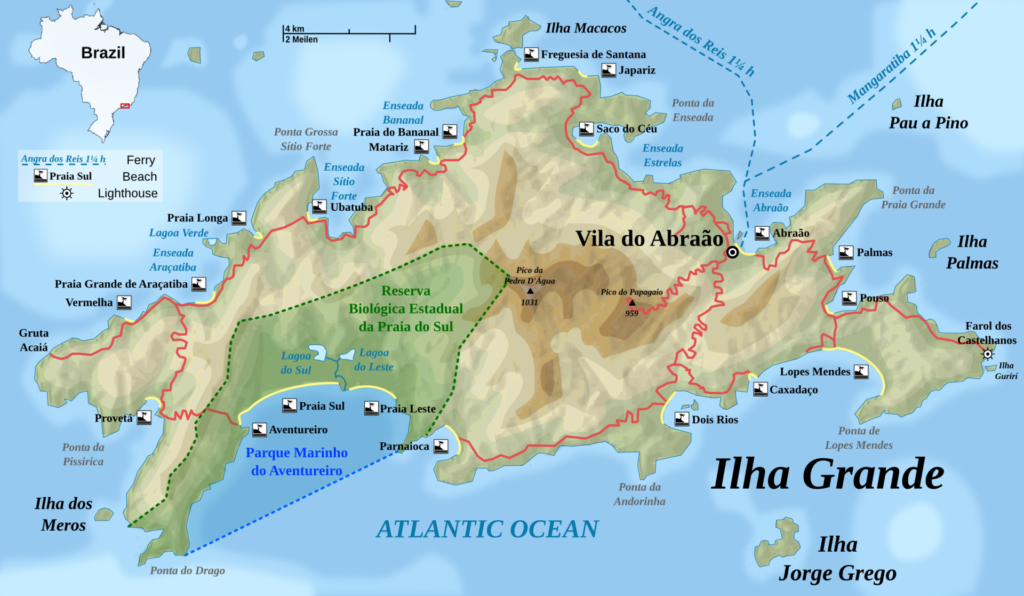

Above: Ilha Grande, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Ilha Grande (“big island“), is a 193 km2 (75 sq mi) forested island located around 12 km (7.5 mi) off of the Atlantic coast of Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, about 243 km (151 mi) from São Paulo. The highest point on Ilha Grande is the 1,031 m (3,383 ft) tall Pico da Pedra D’Água.

But that story has been told.

I was burning to let him know and palpably feel that this time I had in dynamite instead of hay“.

Towed by the Santuit, Slocum and a small crew aboard the Destroyer left Sandy Hook, New Jersey, on 7 December 1893.

The following day the ship was already taking on water:

“A calamity has overtaken us.

The ship’s top seams are opening and one of the new sponsons, the starboard one, is already waterlogged.”

Despite all hands pumping and bailing, by midnight the seas were extinguishing the fires in the boilers which were kept alight only by throwing on rounds of pork fat and tables and chairs from the vessel.

With a storm continuing to blow on the 9th, the crew was able to lower the level of water in the hold and plug some of the holes and leaks.

The bailing out of water, using a large improvised canvas bag, continued from the 9th to the 13th and succeeded in maintaining the level of water in the hold below 3 feet (1 m).

On the 13th they were again hit by a storm and cross seas and had to bail all night.

On the 14th, heavy seas disabled the rudder.

By the afternoon of 15 December, the Destroyer was to the southwest of Puerto Rico, heading for Martinique, and still weathering storms.

Above: (in red) US Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

By that time, with the fires in the boilers extinguished, all hands were bailing for their lives:

“The main hull of the Destroyer is already a foot (30cm) under water, and going on down.”

The crew had no other option than to keep bailing and try to keep the ship afloat, as the vessel “could not be insured for the voyage; nor would any company insure a life on board“.

By the morning of the 16th the storm had abated, allowing the Destroyer to anchor to the south of Puerto Rico.

Although the ship’s best steam pump had been put out of action on 19 December, more favourable seas allowed the crew to reach Martinique, where repairs were made before again setting sail on 5 January 1894.

Above: (in red) French Island Territory of Martinique

On 18 January, the Destroyer arrived at Fernando de Noronha, an island some 175 miles (280 km) from the coast of Brazil, before finally reaching Recife, Pernambuco, on the 20th.

Above: (in red) Fernando de Noronha, Pernambuco, Brazil

Slocum wrote:

“My voyage home from Brazil in the canoe Liberdade, with my family for crew and companions, some years ago, although a much longer voyage was not of the same irksome nature.“

At Pernambuco, the Destroyer joined up with the Brazilian navy and the crew was again engaged in repairs as the long tow in heavy seaways had severed rivets at the bow, resulting in leaks.

Wet powder led to a failed test-firing of the submarine gun and the ship was grounded to remove the projectile.

But the strain of the swell led to a further leak.

Above: Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil

Following further repairs, the Destroyer made for Bahia with replenishments of powder for the Brazilian fleet, arriving on 13 February.

Once there, however, Admiral Gonçalves of the Brazilian navy seized the ship.

At the Arsenal at Bahia, an apparently incompetent alternative crew grounded the Destroyer on a rock in the basin.

The vessel was holed and subsequently abandoned.

Above: (in red) Bahia, Brazil

Slocum rebuilt the 36 ft 9 in (11.2 m) gaff rigged sloop oyster boat named Spray in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, during 1891 and 1892.

Above: Fairhaven, Massachusetts, USA

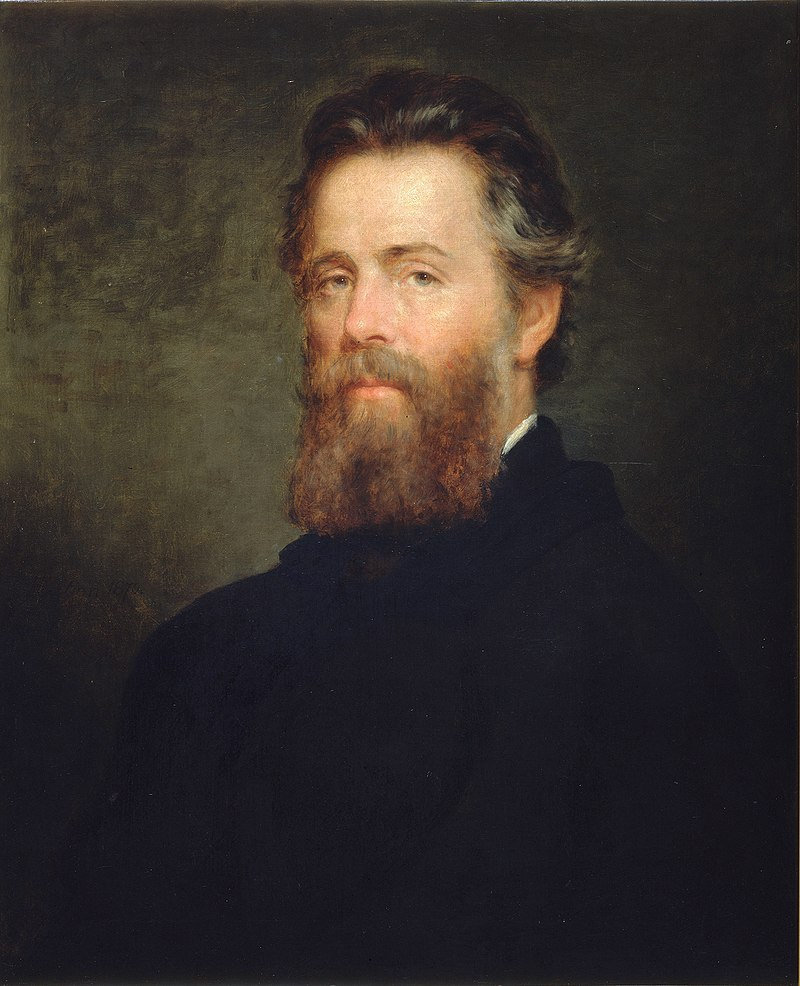

Herman Melville (1819 – 1891), author of the classic novel Moby Dick, 21-year old Melville stayed briefly in a rooming house in Fairhaven and on 3 January 1841, set sail from here in the whaleship Acushnet.

Above: American author Herman Melville

“John” Manjiro Nakahama (1827 – 1898), the first Japanese person to live in America, was a Japanese samurai and translator who was one of the first Japanese people to visit the United States and an important translator during the opening of Japan (1853 – 1867).

He was a fisherman before his journey to the United States, where he studied English and navigation and became a sailor and gold miner.

After returning to Japan, he was elevated to the status of a samurai (knight) and was made a hatamoto (high-ranking samurai).

He served his country as an interpreter and translator and was instrumental in negotiating the Convention of Kanagawa (31 March 1854).

He also taught as a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University.

During his early life, he lived as a simple fisherman in the village of Naka-no-hama, Tosa Province (now Tosashimizu, Kōchi Prefecture).

In 1841, 14-year-old Nakahama Manjirō and four friends (four brothers named Goemon, Denzo, Toraemon, and Jusuke) were fishing when their boat was wrecked on the island of Torishima.

The American whaleship John Howland, with Captain William H. Whitfield in command, rescued them.

At the end of the voyage, four of them were left in Honolulu.

However, Manjirō (nicknamed “John Mung“) wanted to stay on the ship.

Captain Whitfield took him back to the US and briefly entrusted him to his neighbor Ebenezer Akin, who enrolled Manjirō in the Oxford School in the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts.

The boy studied English and navigation for a year, apprenticed to a cooper (wooden barrel maker), and then, with Whitfield’s help, signed on to the whaleship Franklin (Captain Ira Davis).

Above: US Captain William Whitfield (1804 – 1886)

After whaling in the South Seas, the Franklin put into Honolulu in October 1847, where Manjirō again met his four friends.

None were able to return to Japan, for this was during Japan’s period of isolation (1636 – 1853), when leaving the country was an offense punishable by death.

When Captain Davis became mentally ill and was left in Manila, the crew elected a new captain.

Manjirō was made boatsteerer (harpooner).

The Franklin returned to New Bedford, Massachusetts in September 1849 and paid off its crew.

Manjirō was self-sufficient, with $350 ($13,229 in 2024) in his pocket.

Manjirō promptly set out by sea for the California Gold Rush (1848 – 1855).

Arriving in San Francisco in May 1850, he took a steamboat up the Sacramento River, then went into the mountains.

In a few months, he found enough gold to exchange for about 600 pieces of silver and decided to find a way back to Japan nearly a decade after being rescued from the island of Torishima.

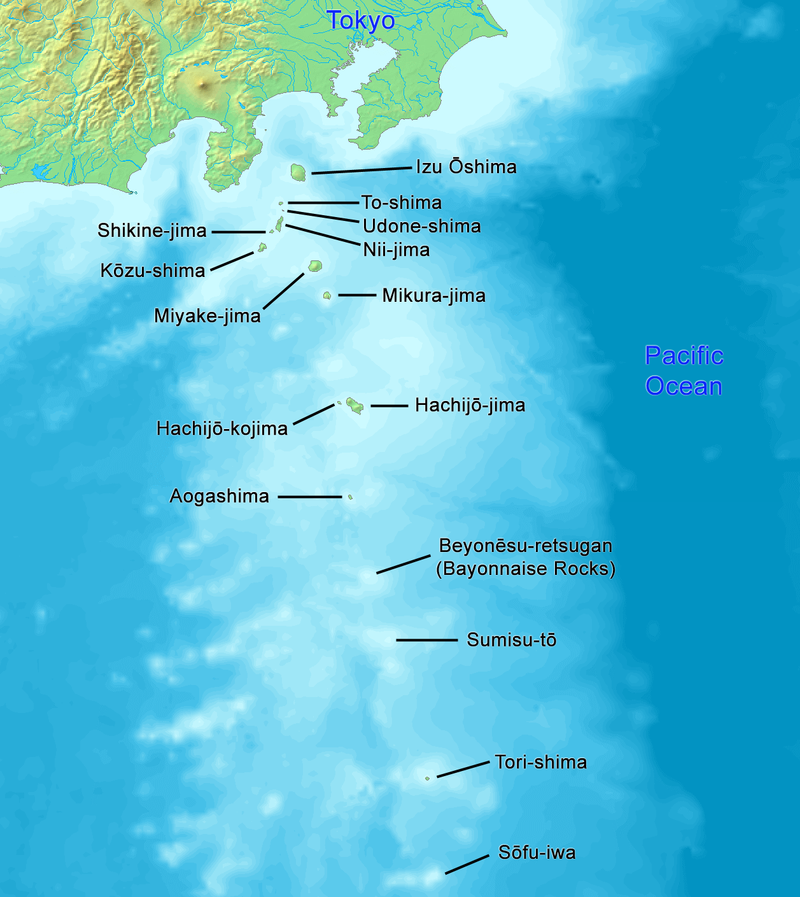

Above: Map of the Izu Islands, Japan

Manjirō arrived in Honolulu and found two of his companions were willing to go with him.

Toraemon, who thought it would be too risky, did not voyage back to Japan.

Jusuke had died of a heart ailment.

Manjirō purchased a whaleboat, the Adventure, which was loaded aboard the bark Sarah Boyd (Captain Whitmore) along with gifts from the people of Honolulu.

They sailed on 17 December 1850.

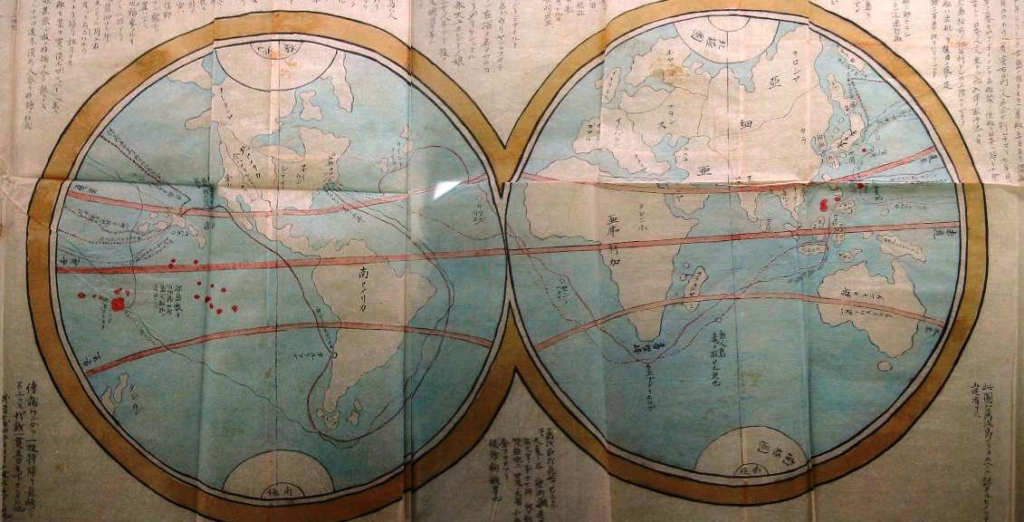

Above: Nakahama Manjirō’s report of his travels, Tokyo National Museum

They reached Okinawa on 2 February 1851.

The three were promptly taken into custody, although treated with courtesy.

After months of questioning, they were released in Nagasaki and eventually returned home to Tosa where Lord Yamauchi Toyoshige awarded them pensions.

Manjirō was appointed a minor official and became a valuable source of information.

In September 1853, Manjirō was summoned to Edo (now known as Tokyo), questioned by the shogunate government, and made a hatamoto (a samurai in direct service to the shōgun).

He would now give interviews only in service to the government. In token of his new status, he would wear two swords, and needed a surname.

He chose Nakahama, after his home village.

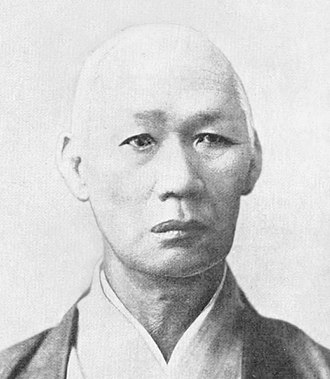

Above: Japanese samuraı/translator Nakahama Manjirō

Christopher Reeve (1952 – 2004), of Superman fame, the summer resident kept a sailboat, the 40-foot (12 m) sloop-rigged Chandelle, at a Fairhaven shipyard and sometimes flew into New Bedford Regional Airport to pick it up or to stay in town during a stopover en route to Martha’s Vineyard.

Above: American actor Christopher Reeve

Frances Ford Seymour (1908 – 1950), wife of actor Henry Fonda (1905 – 1982) and mother of actress Jane Fonda and actor Peter Fonda (1940 – 2019), lived in Fairhaven for several years with family members and attended Fairhaven High School

Above: Canadian – American socialite Frances Ford Seymour

Above: US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) was a summer resident in Fairhaven

On 21 June 1892, Slocum launched the painstakingly rebuilt vessel.

Above: The Spray

The Spray originally belonged to Captain Eben Pierce of Fairhaven, a whaling captain, who gave the derelict boat, slowly deteriorating in a ship cradle in a meadow on Fairhaven’s Poverty Point, to his friend, Captain Slocum.

Slocum spent 13 months in Fairhaven while working on the Spray, making her fit for open-ocean sailing.

Fairhaven oak formed much of the boat’s refitted structure.

The Spray and her one-man crew returned after nearly three and a half years to the very cedar spile that was used for her launch.

On 24 April 1895, he set sail from Boston, Massachusetts.

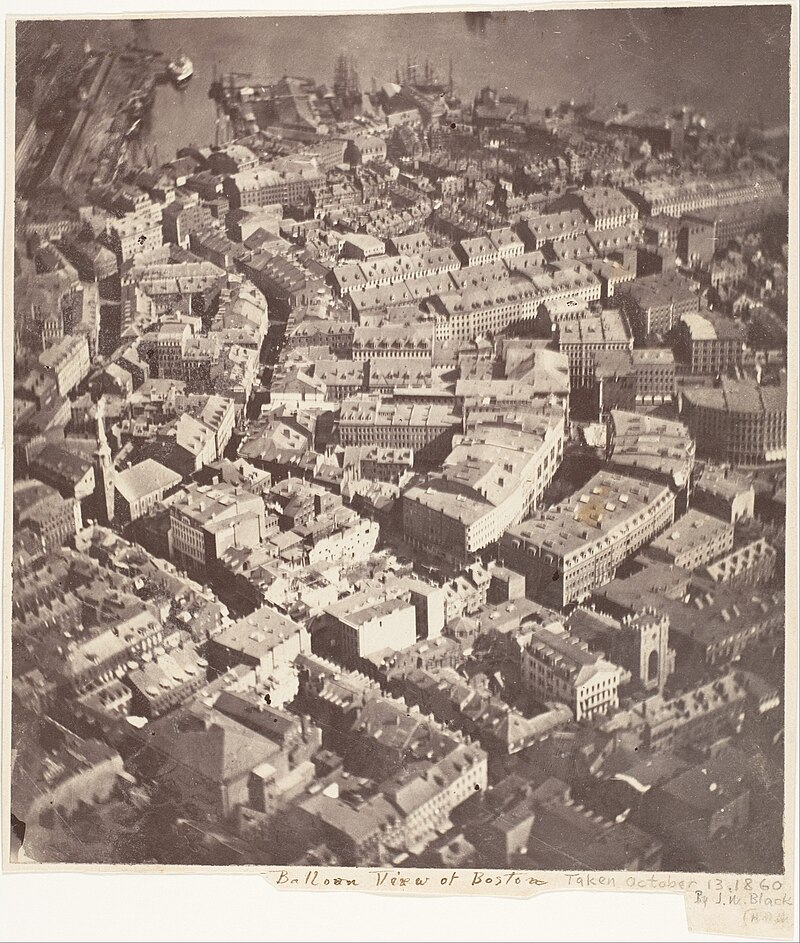

Above: Boston (1860)

In his famous book, Sailing Alone Around the World, now considered a classic of travel literature, he described his departure in the following manner:

I had resolved on a voyage around the world, and as the wind on the morning of 24 April 1895 was fair, at noon I weighed anchor, set sail, and filled away from Boston, where the Spray had been moored snugly all winter.

The twelve o’clock whistles were blowing just as the sloop shot ahead under full sail.

A short board was made up the harbor on the port tack, then coming about she stood to seaward, with her boom well off to port, and swung past the ferries with lively heels.

A photographer on the outer pier of East Boston got a picture of her as she swept by, her flag at the peak throwing her folds clear.

A thrilling pulse beat high in me.

My step was light on deck in the crisp air.

I felt there could be no turning back, and that I was engaging in an adventure the meaning of which I thoroughly understood.

After an extended visit to his boyhood home at Brier Island and visiting old haunts on the coast of Nova Scotia, Slocum departed North America at Sambro Island Lighthouse near Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 3 July 1895.

Above: Brier Island, Nova Scotia, Canada

Above: Lighthouse, Sambro Island, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

The Sambro Island Lighthouse is the oldest surviving lighthouse in North America.

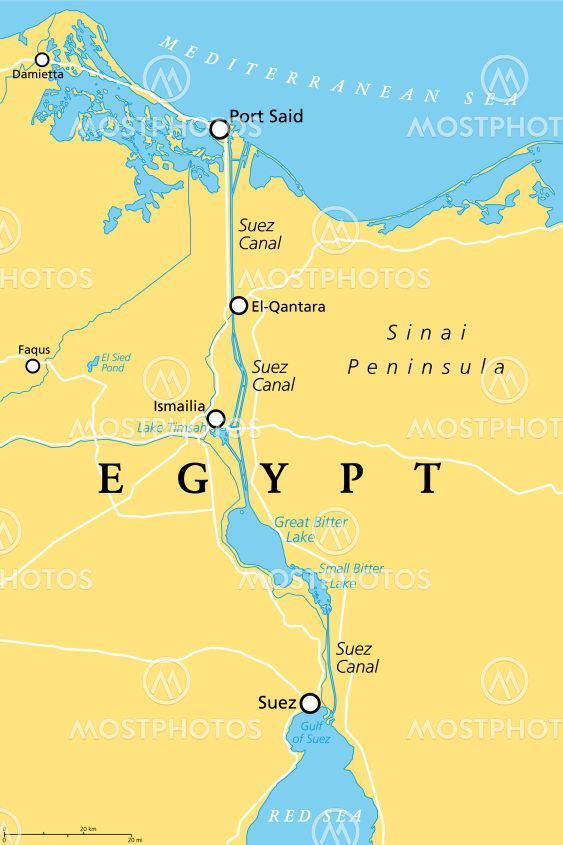

Slocum intended sailing eastward around the world, using the Suez Canal, but when he got near Gibraltar he realized that sailing through the southern Mediterranean would be too dangerous for a lone sailor because piracy was still prevalent there at the time.

Above: The Suez Canal, Egypt

Above: (in green) Gibraltar

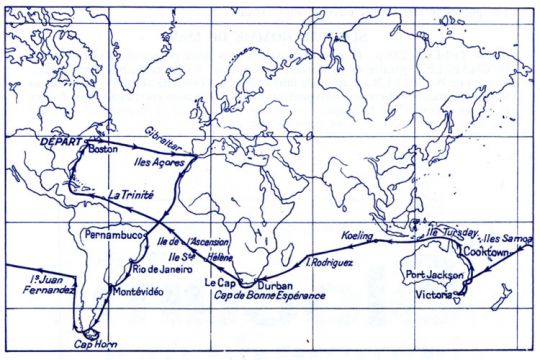

So he decided to sail westward, in the southern hemisphere.

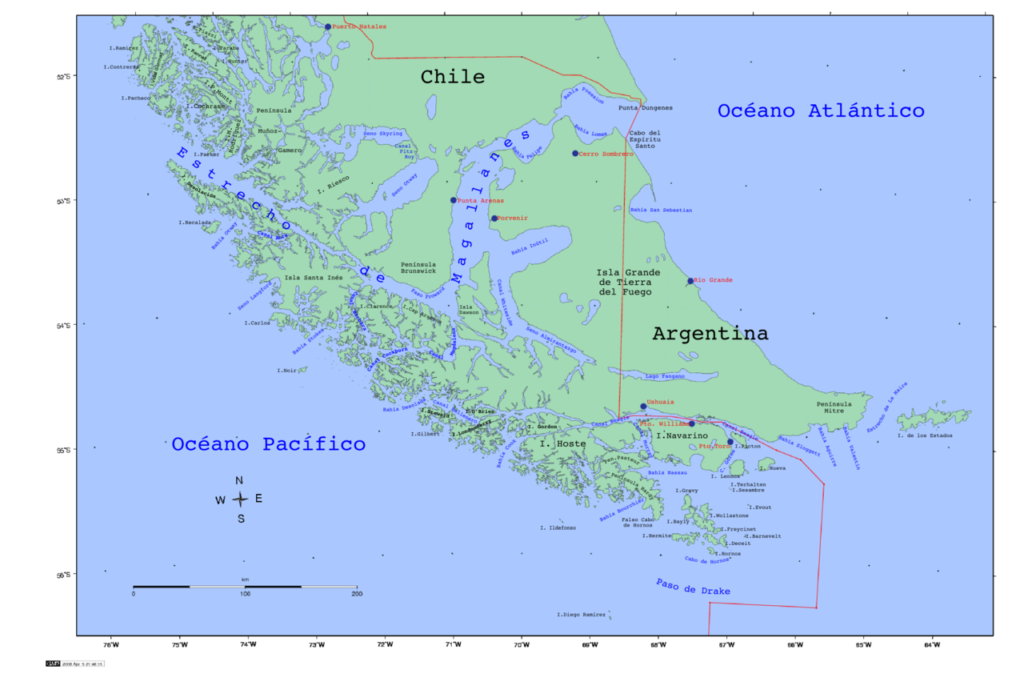

He headed to Brazil and then to the Straits of Magellan.

Above: Magellan Strait

At that point he was unable to start across the Pacific for forty days because of a storm.

Eventually, he made his way to Australia, sailed north along its east coast, crossed the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and then headed back to North America.

Slocum navigated without a chronometer, instead relying on the traditional method of dead reckoning to establish longitude, which required only a cheap tin clock for approximate time, and used noon-sun sights for latitude.

On one long passage in the Pacific, he also famously shot a lunar distance observation, decades after those observations had ceased to be commonly employed, which allowed him to check his longitude independently.

However, Slocum’s primary method for finding longitude was still dead reckoning, and he recorded only one lunar observation during the entire circumnavigation.

Slocum normally sailed the Spray without touching the helm.

Due to the length of the sail plan relative to the hull, and the long keel, the Spray was capable of self-steering (unlike faster modern craft).

He balanced it stably on any course relative to the wind by adjusting or reefing the sails and by lashing the helm fast.

He devised a system of lashing the wheel into what a later era might call a kind of mechanical autopilot.

He sailed 2,000 miles (3,200 km) west across the Indian Ocean without once touching the helm.

Slocum attracted considerable international interest by his journey, particularly once he had entered the Pacific.

He was awaited at most of his ports of call, and gave lectures and lantern-slide shows to well-filled halls.

Highlights of the journey included perils of sailing blue water, such as fog, gales, danger of collision, loneliness, doldrums (lack of wind), navigation, fatigue, gear failure.

Other perils of coastal navigation included pirates, attack by ‘savages‘, embayment (unexpected beaches beneath the keel), shoals and coral reefs, stranding (when a ship accidentally runs into something underwater, making it hard to move around), and shipwreck.

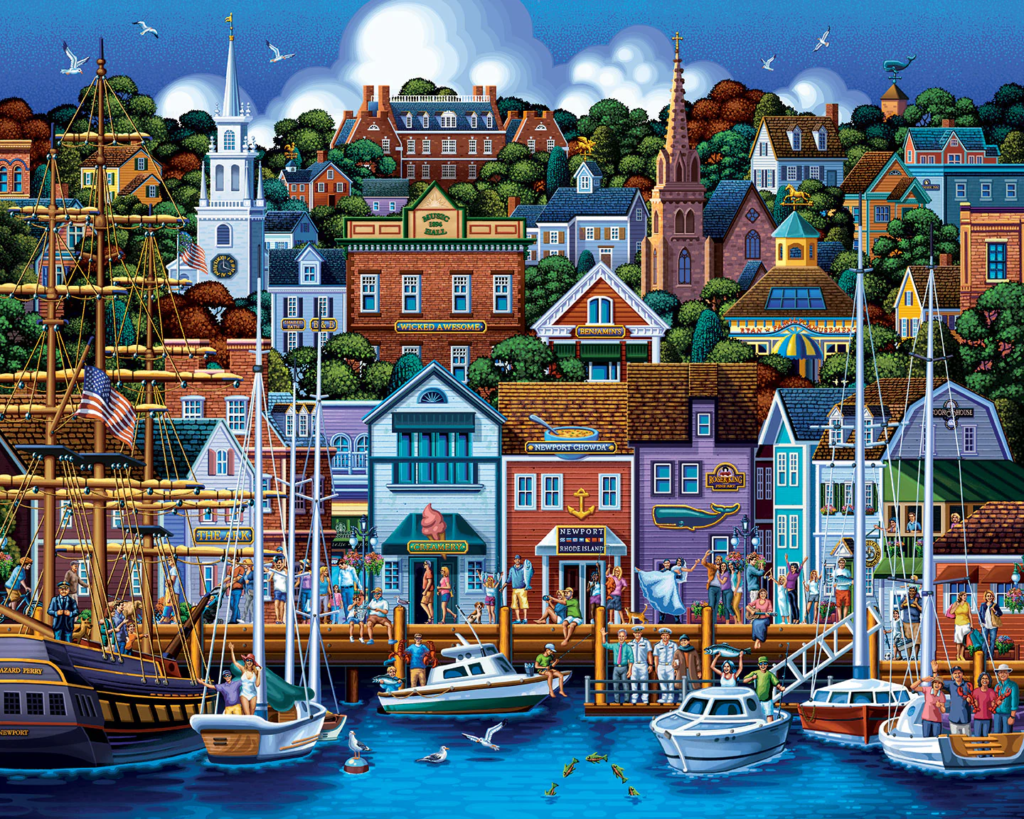

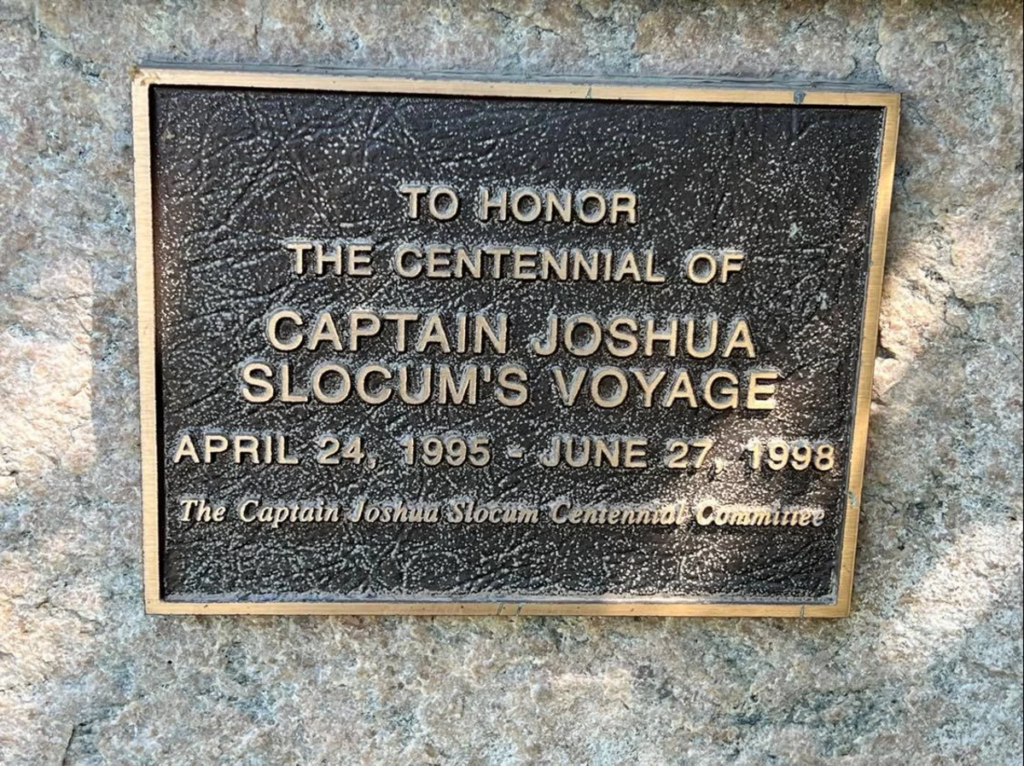

More than three years later, on 27 June 1898, he returned to Newport, Rhode Island, having circumnavigated the world and sailing a distance of more than 46,000 miles (74,000 km).

The trip itinerary was as follows:

- Fairhaven

Above: Fairhaven, Massachusetts, USA

- Boston

Above: Boston, Massachusetts, USA

- Gloucester

Above: Gloucester Harbor, William Morris Hunt (1877)

Above: Fisherman’s Memorial, Gloucester, Massachusetts, USA

- Nova Scotia

Above: Provincial flag of Nova Scotia, Canada

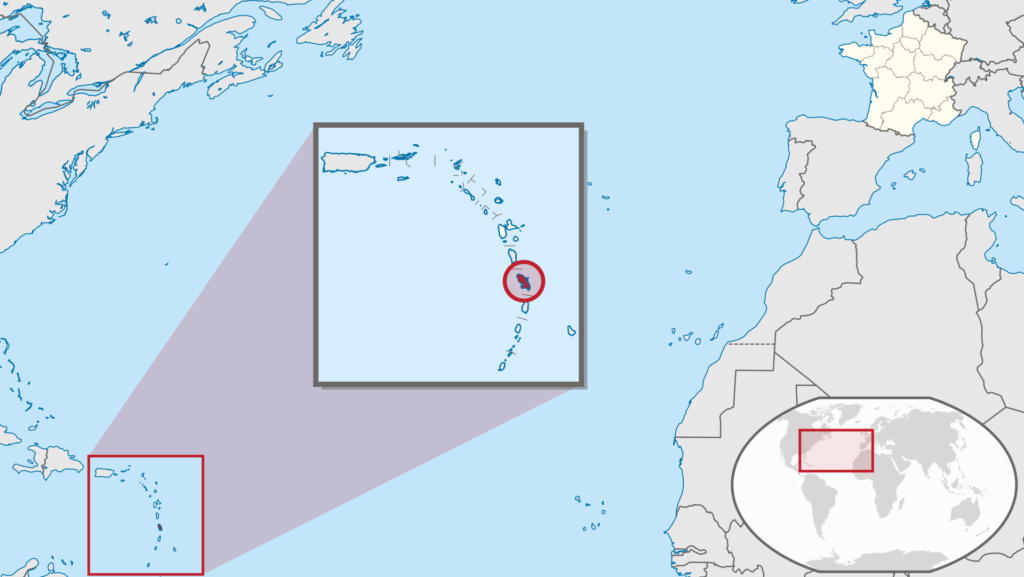

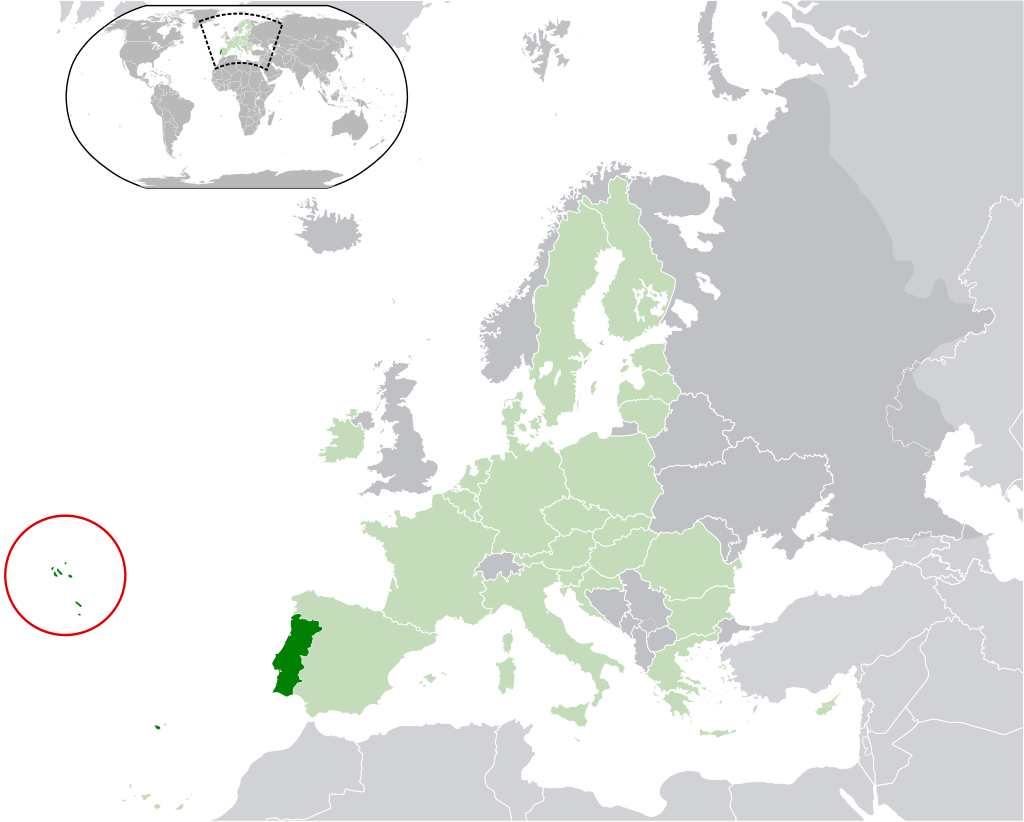

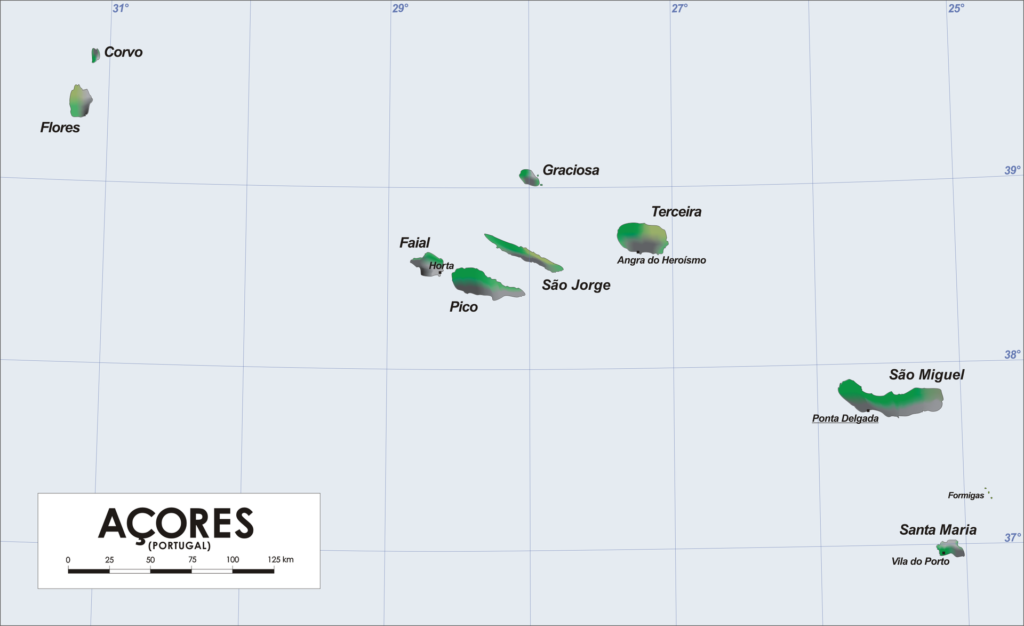

- Azores

Above: (in red circle) Portuguese Azores Islands

Above: Map of the Azores

Above: Flag of the Azores, Portugal

- Gibraltar

Above: Flag of British Territory Gibraltar

- Morocco

Above: (in green) Morocco / disputed territory with Spain (light green)

Above: Flag of Morocco

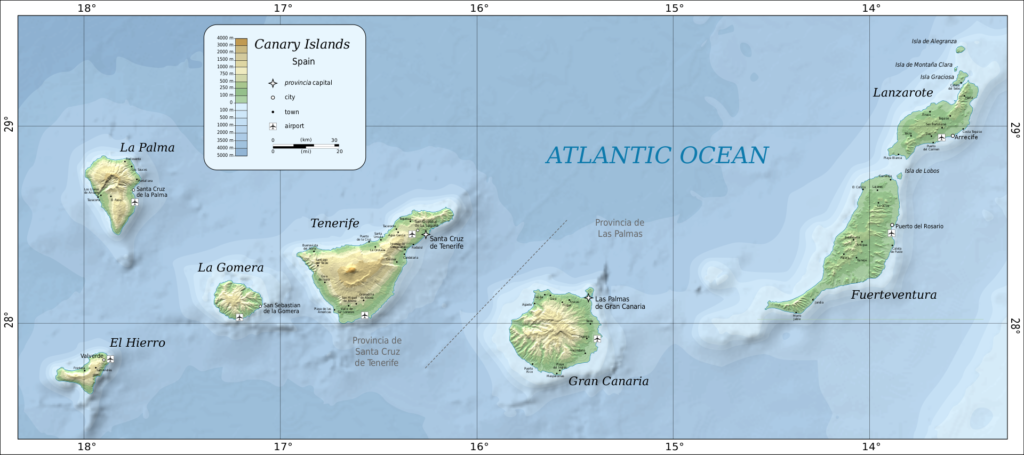

- Canary Islands

Above: (in red) Canary Islands

Above: Flag of the Spanish Canary Islands

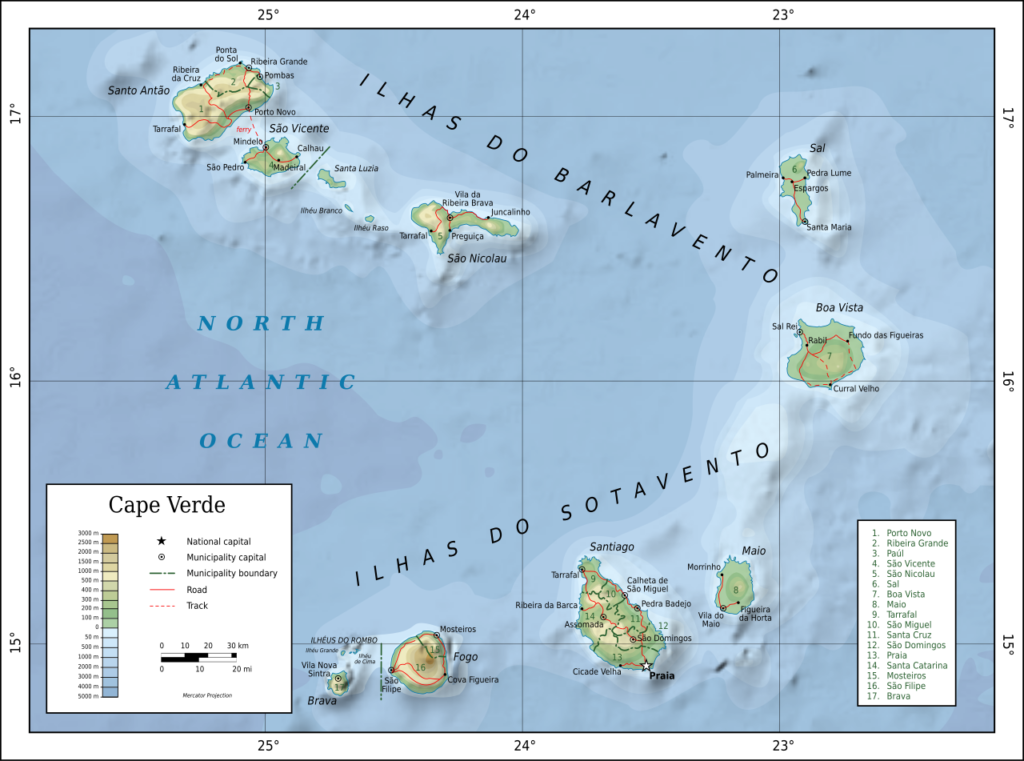

- Cape Verde Islands

Above: (in green) Cape Verde Islands / Cabo Verde

Above: Flag of Cabo Verde

- Pernambuco

Above: Flag of Pernambuco, Brazil

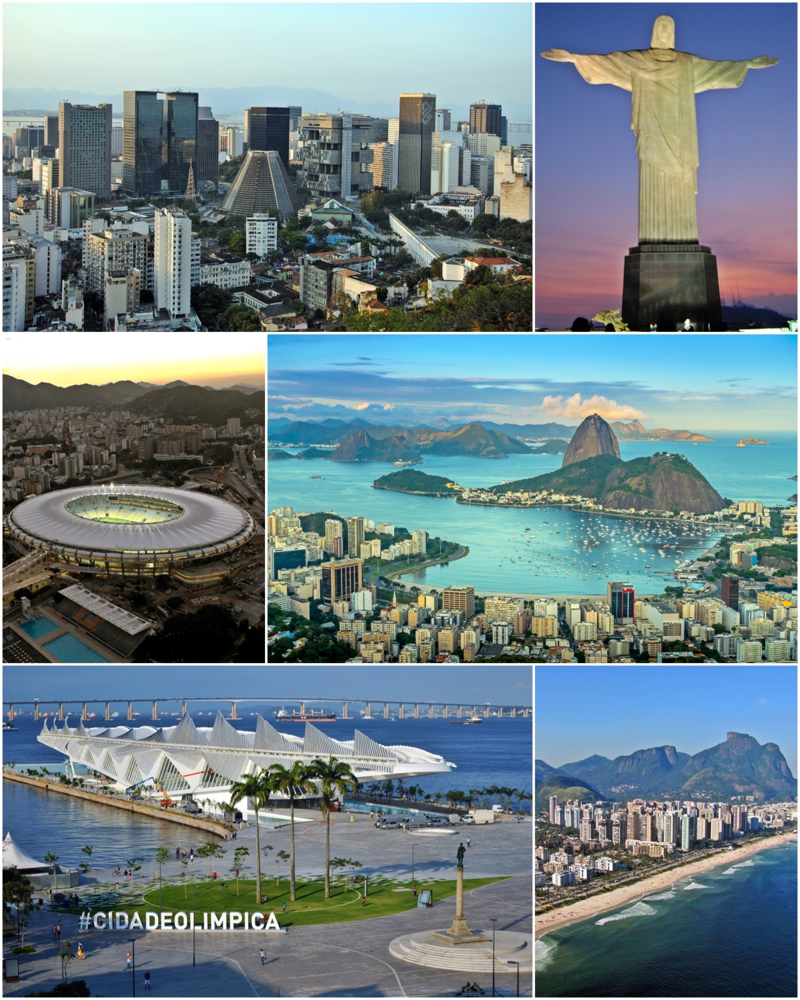

- Rio de Janeiro

Above: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Maldonado

Above: Maldonado, Uruguay

- Montevideo

Above: Montevideo, Uruguay

- Buenos Aires

Above: Buenos Aires, Argentina

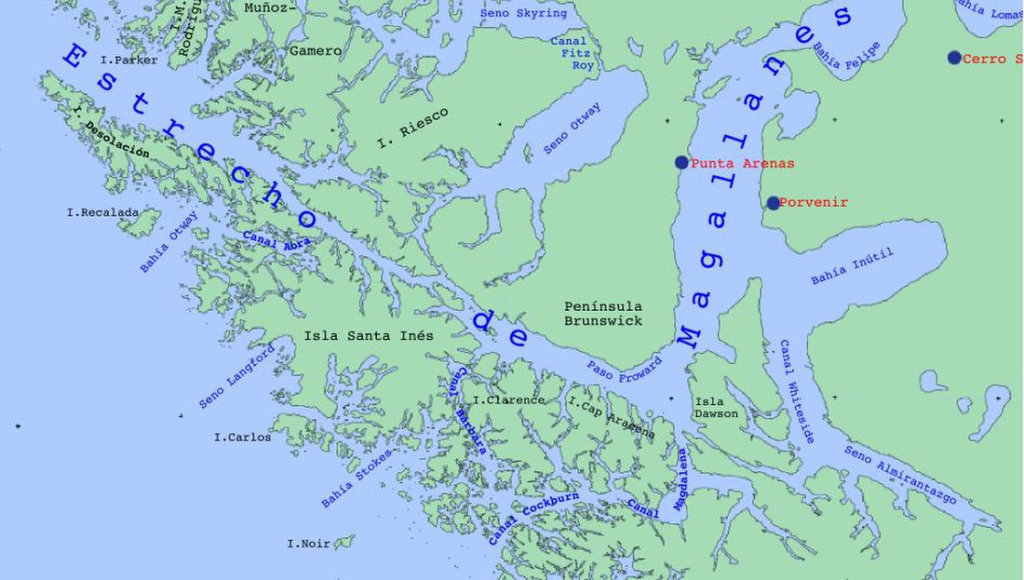

- the Strait of Magellan

Above: The Strait of Magellan

- Punta Arenas

Above: Punta Arenas, Chile

- Cockburn Channel

Above: Cockburn Channel

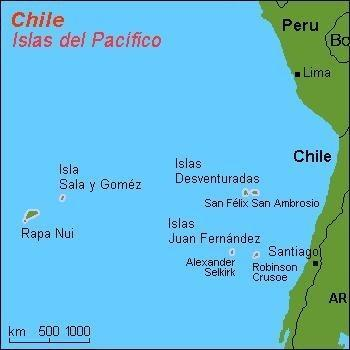

- Juan Fernandez Islands

Above: Flag of Islas Juan Fernández, Chile

- the Marquesas Islands

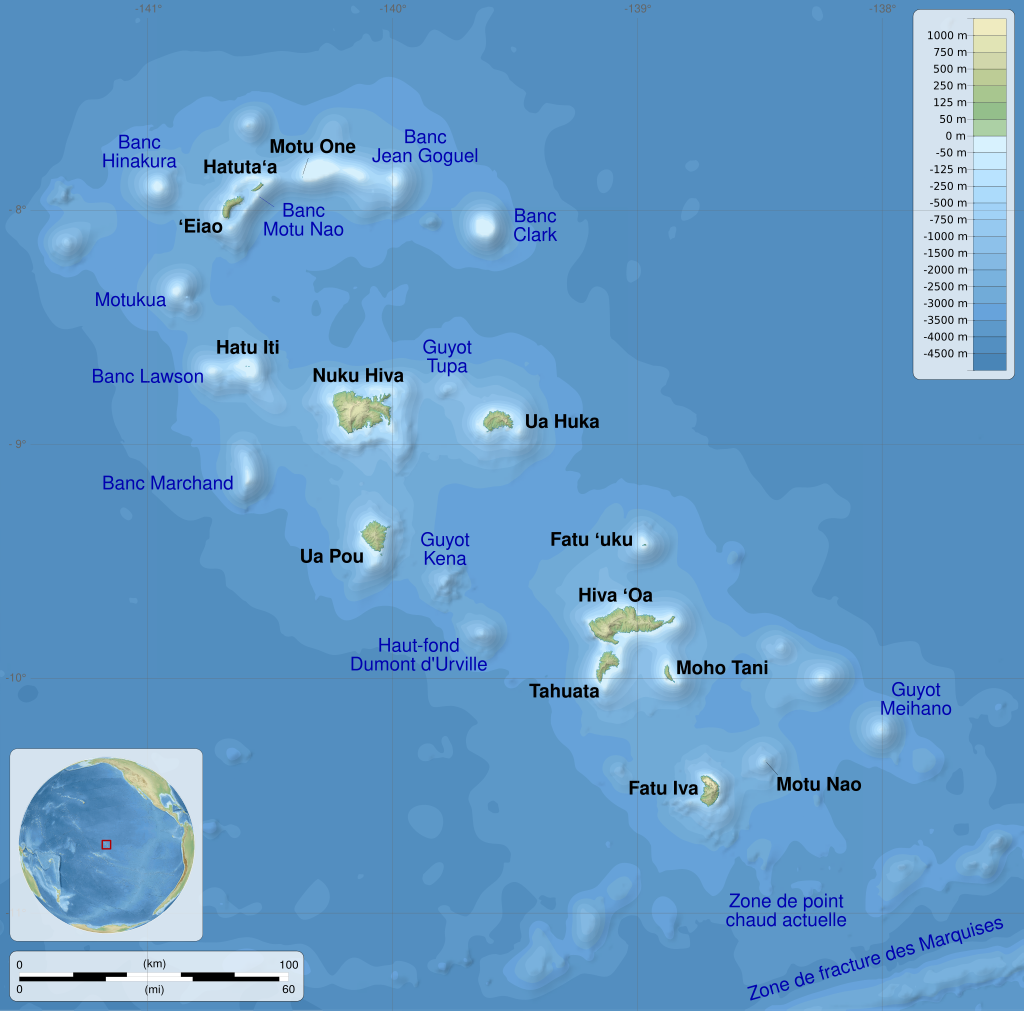

Above: Map of the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia

Above: Flag of the Marquesas Islands

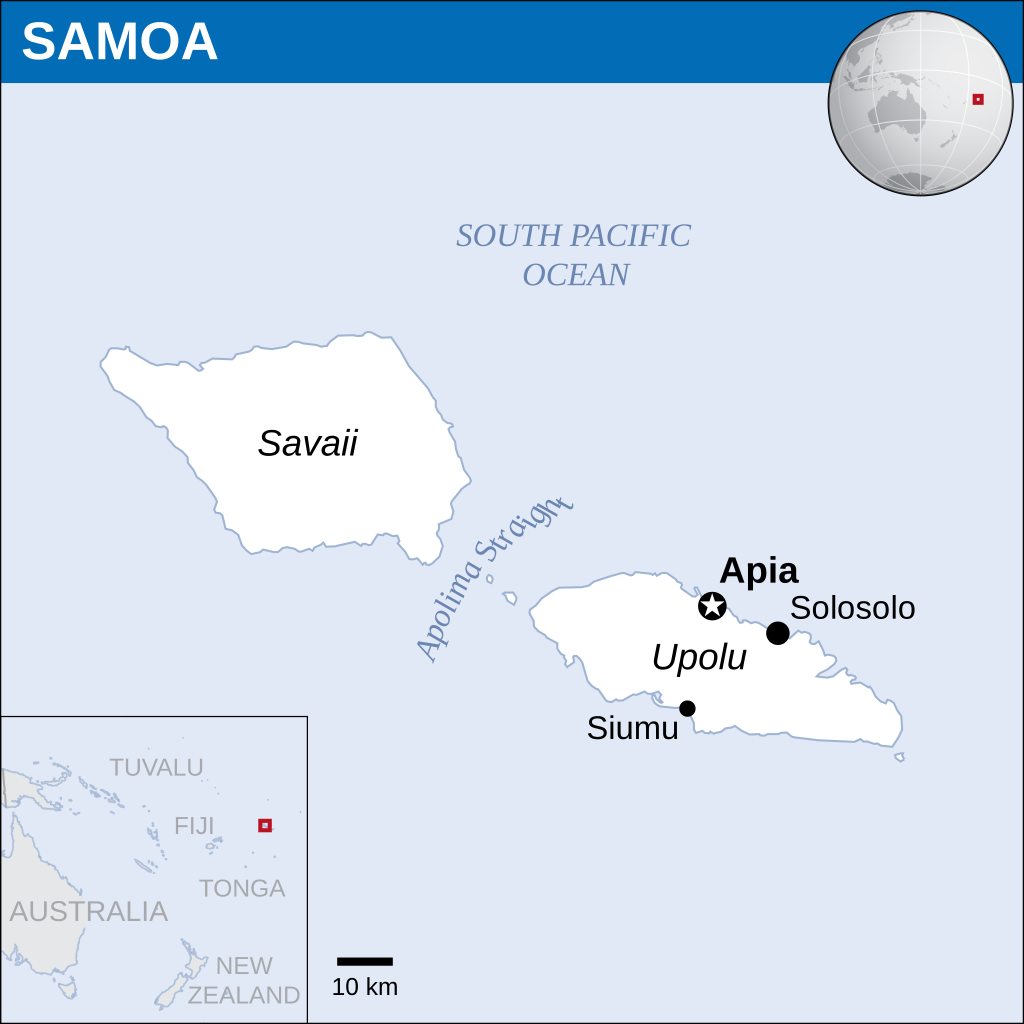

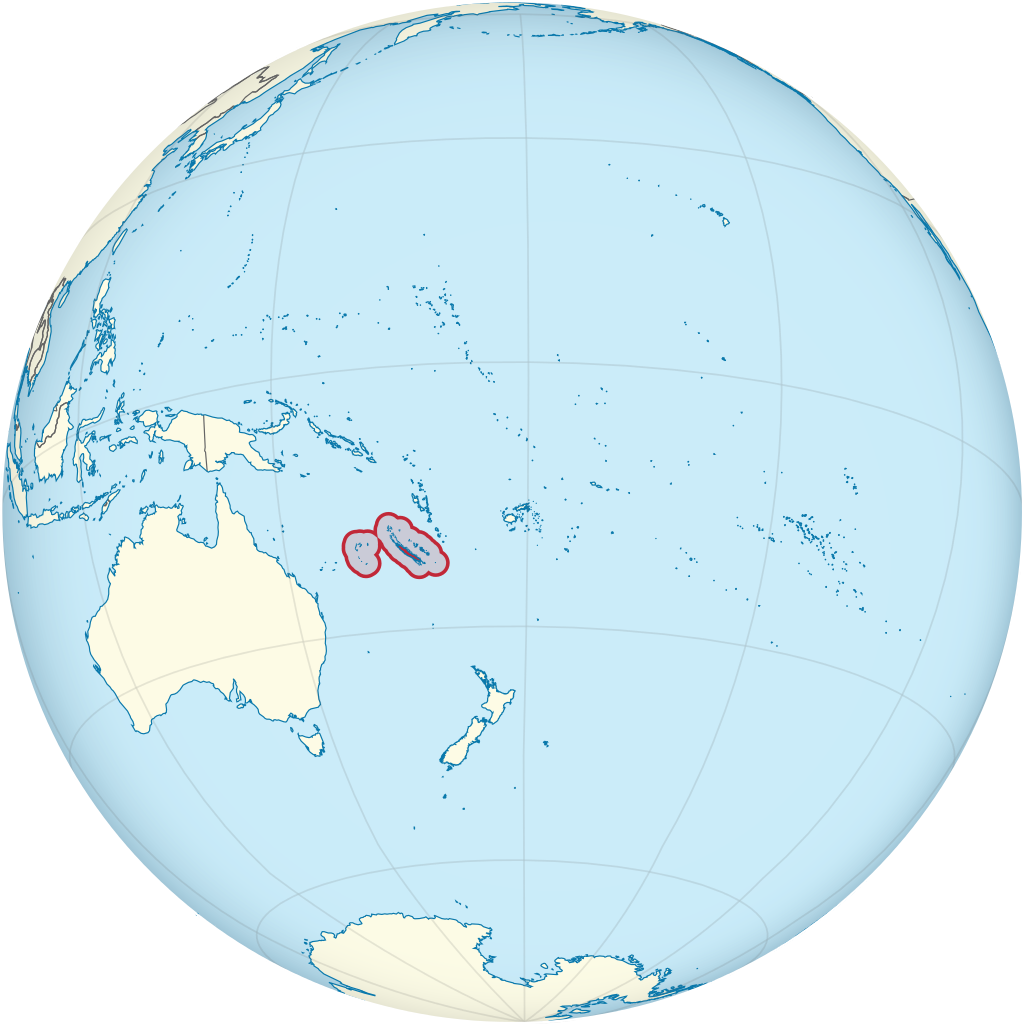

- Samoa

Above: (in red) Samoa

Above: Flag of Samoa

- Fiji

Above: (in red) Fiji

Above: Map of Fiji

Above: Flag of Fiji

- Sydney

Above: Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- Melbourne

Above: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- Tasmania

Above: (in red) Tasmania, Australia

Above: State flag of Tasmania, Australia

- Cooktown

Above: Cooktown, Queensland, Australia

- Christmas Island

Above: (in red circle) Christmas Island

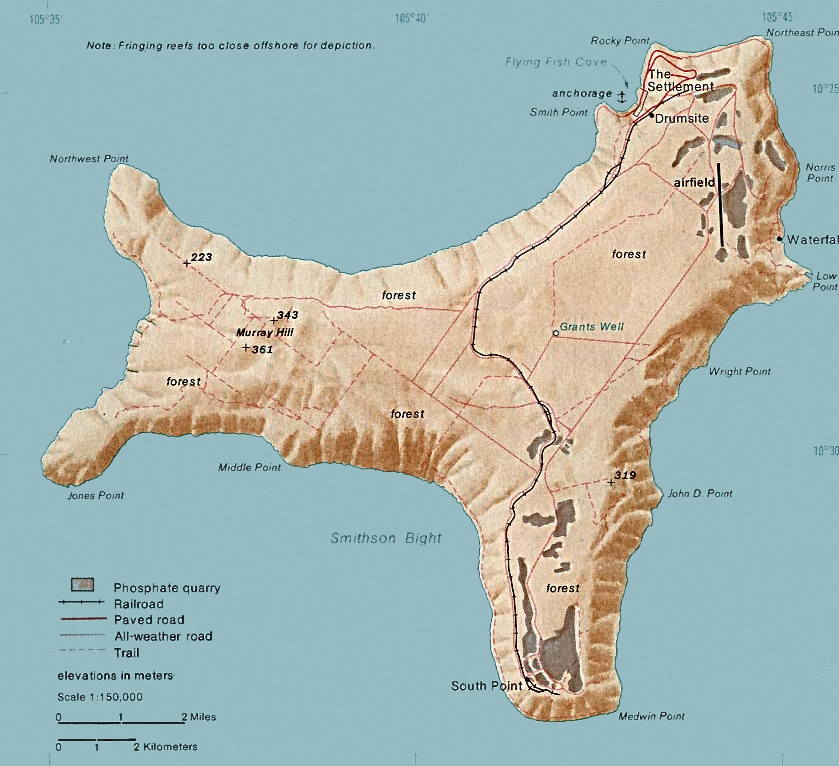

Above: Map of Christmas Island

Above: Territorial flag of Christmas Island, Australia

- Cocos Islands

Above: (in red circle) Cocos Islands

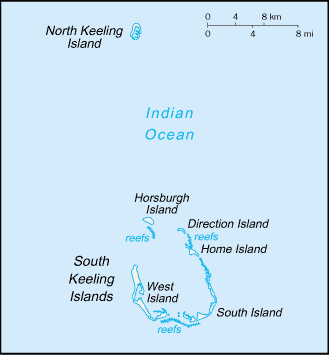

Above: Map of the Cocos Islands

Above: Territorial flag of the Cocos Islands, Australia

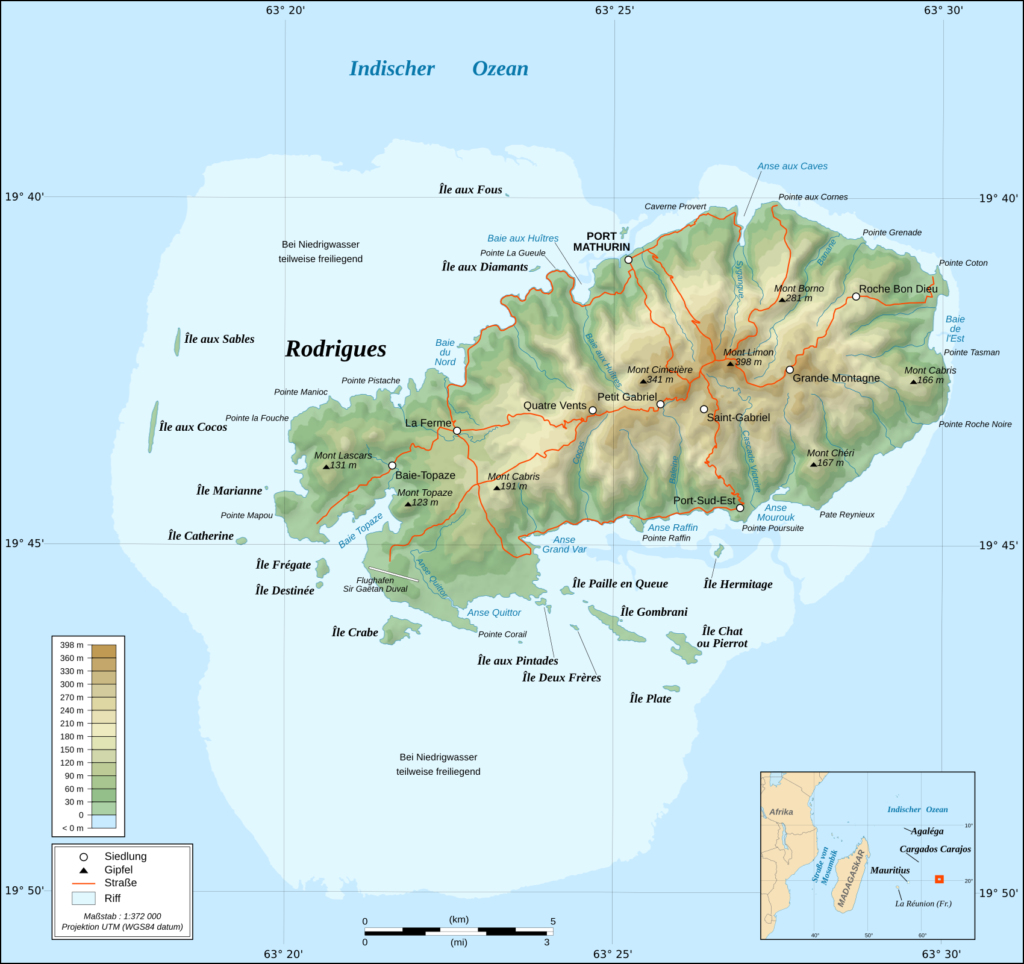

- Rodrigues

Above: (in red circle) Rodrigues Island

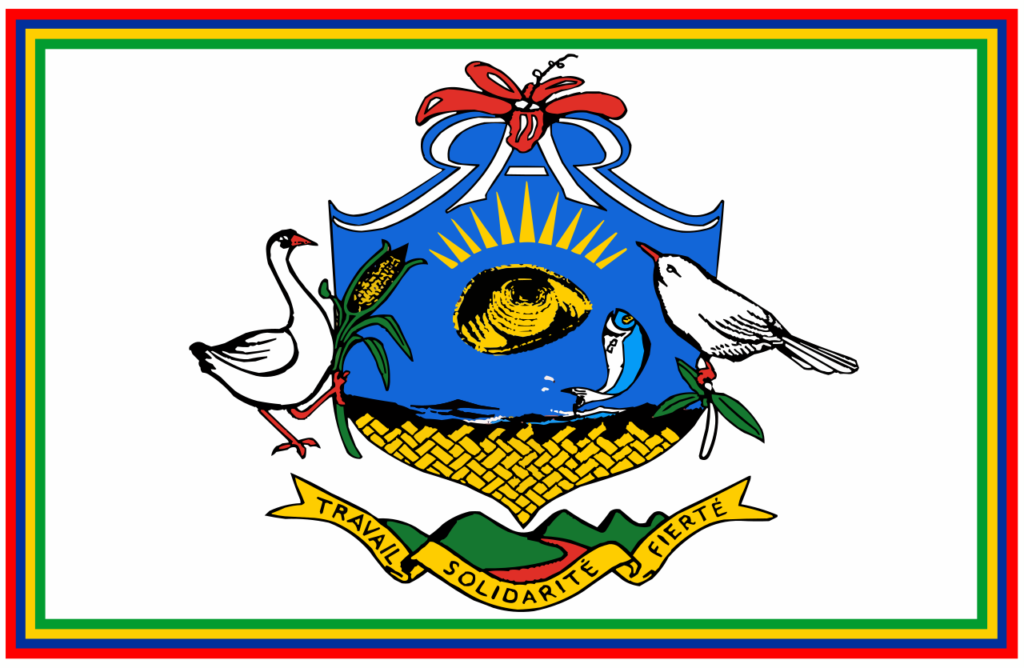

Above: Flag of Rodrigues, Mauritius

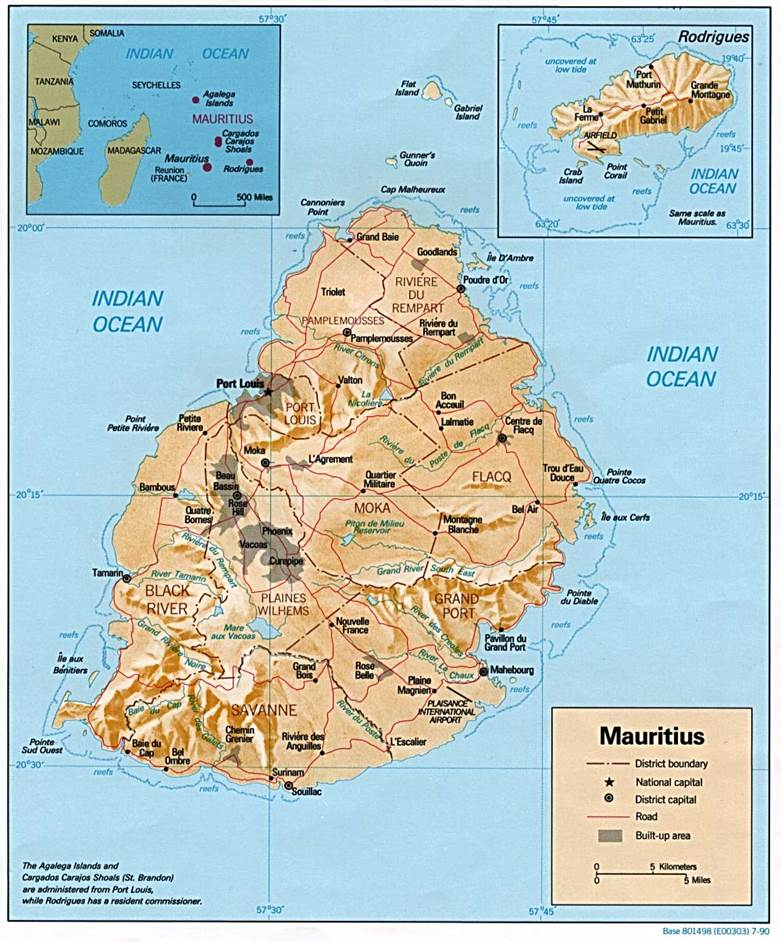

- Mauritius

Above: Flag of Mauritius

- Durban

Above: Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Cape Town

Above: Cape Town, South Africa

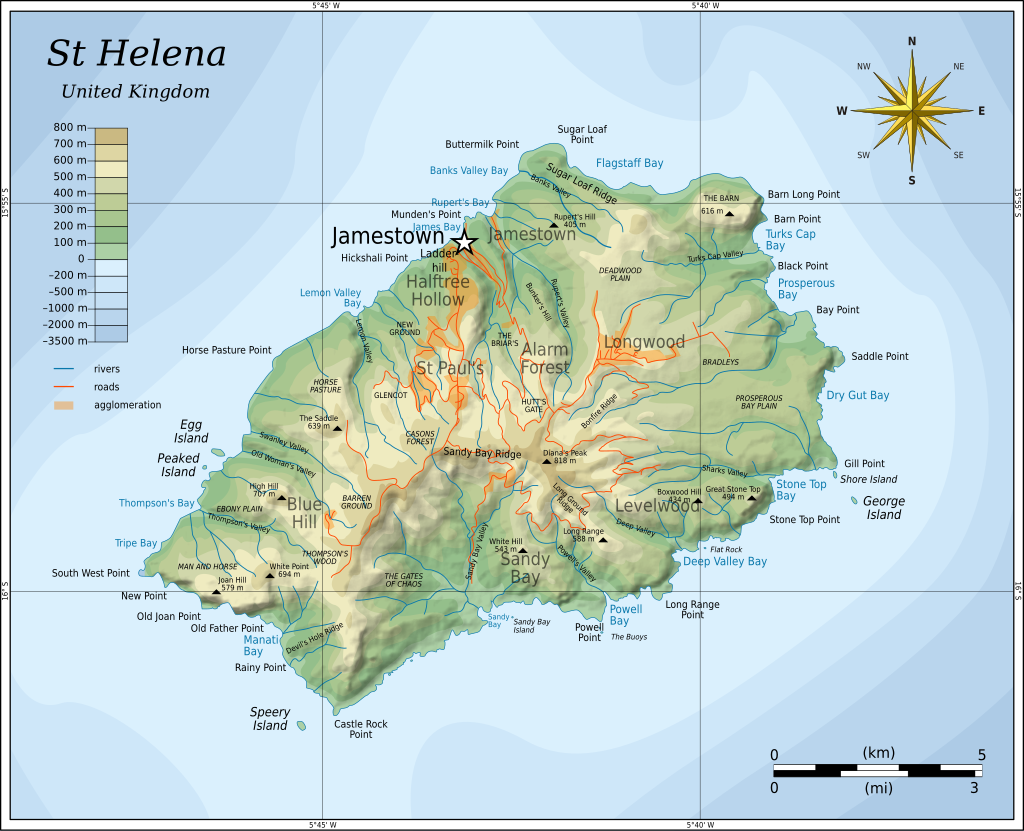

- St. Helena

Above: (in red circle) St. Helena

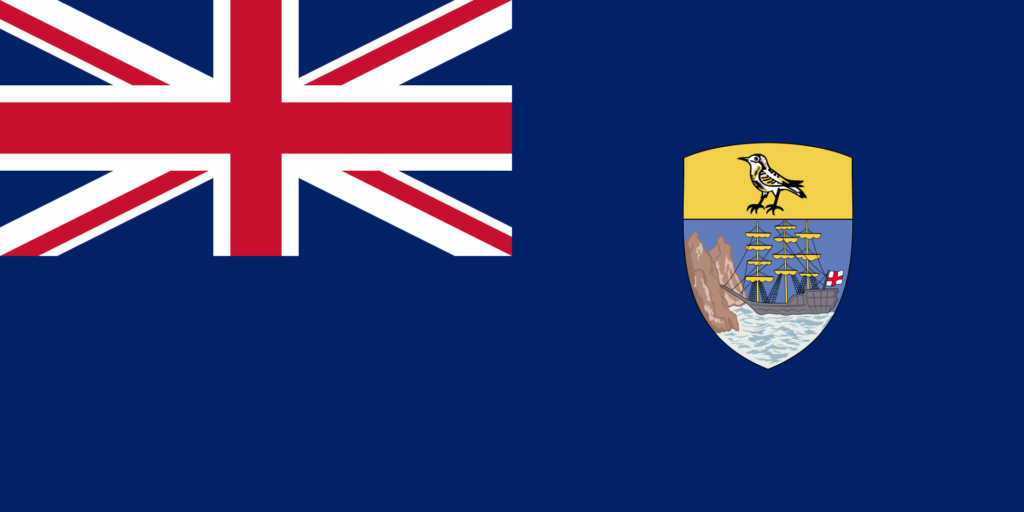

Above: Territorial flag of St. Helena, United Kingdom

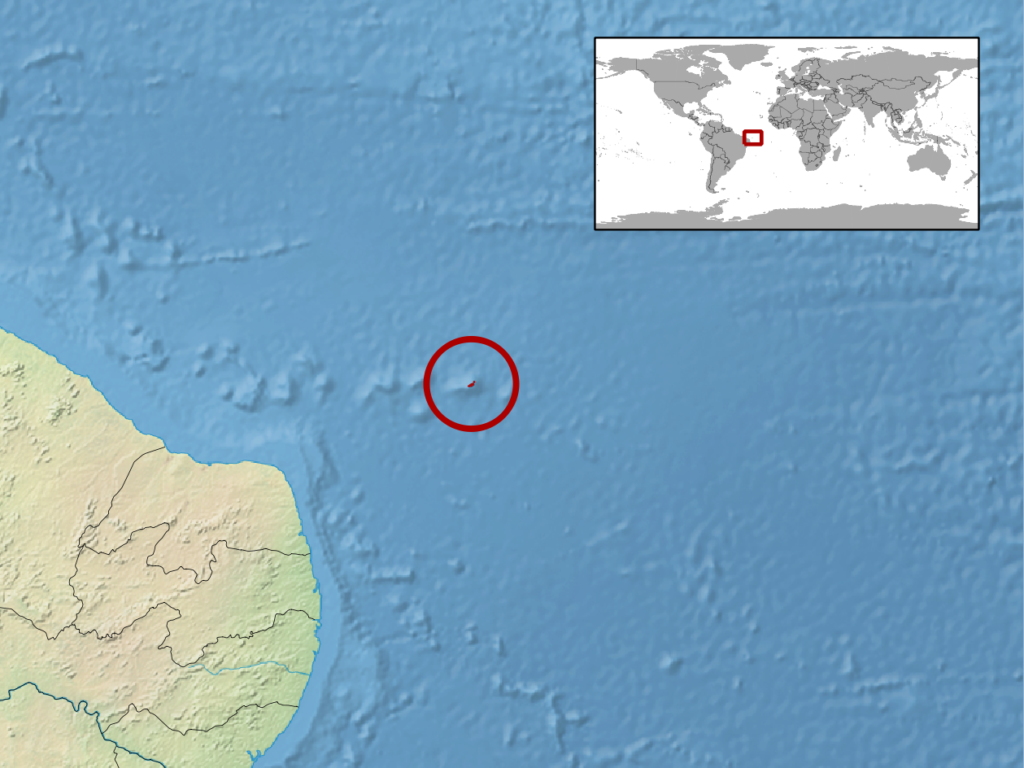

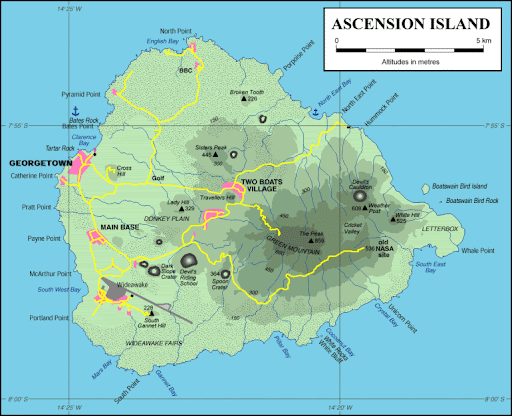

- Ascension Island

Above: (in red circle) Ascension Island

Above: Territorial flag of Ascension Island, United Kingdom

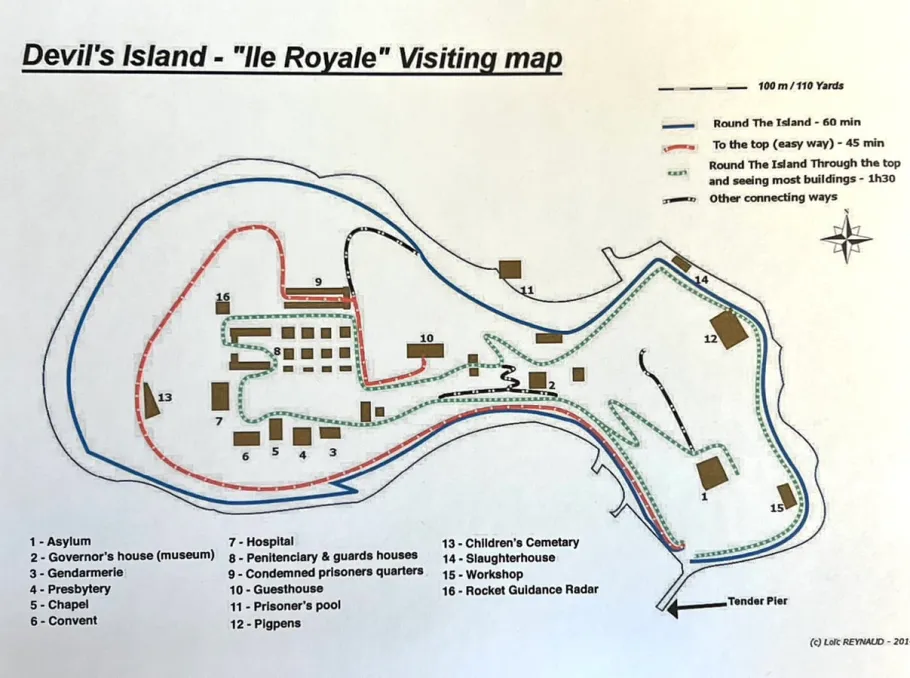

- Devil’s Island (Île du Diable)

Above: Dreyfus Tower, Île du Diable, Guyane (French Guiana)

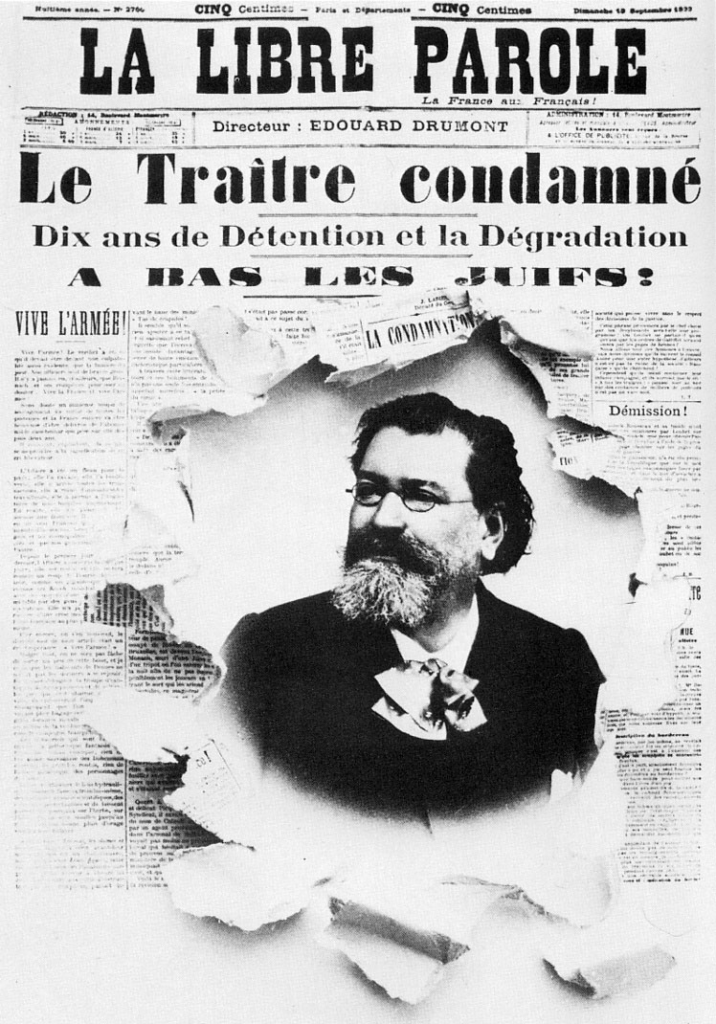

The penal colony of Cayenne (Bagne de Cayenne), commonly known as Devil’s Island (Île du Diable), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953, in the Salvation Islands of French Guiana.

Opened in 1852, the Devil’s Island system received convicts from the Prison of St-Laurent-du-Maroni, who had been deported from all parts of the Second French Empire.

Above: French prison hulk in Toulon harbor, 1850

It was notorious both for the staff’s harsh treatment of detainees and the tropical climate and diseases that contributed to high mortality, with a death rate of 75% at its worst.

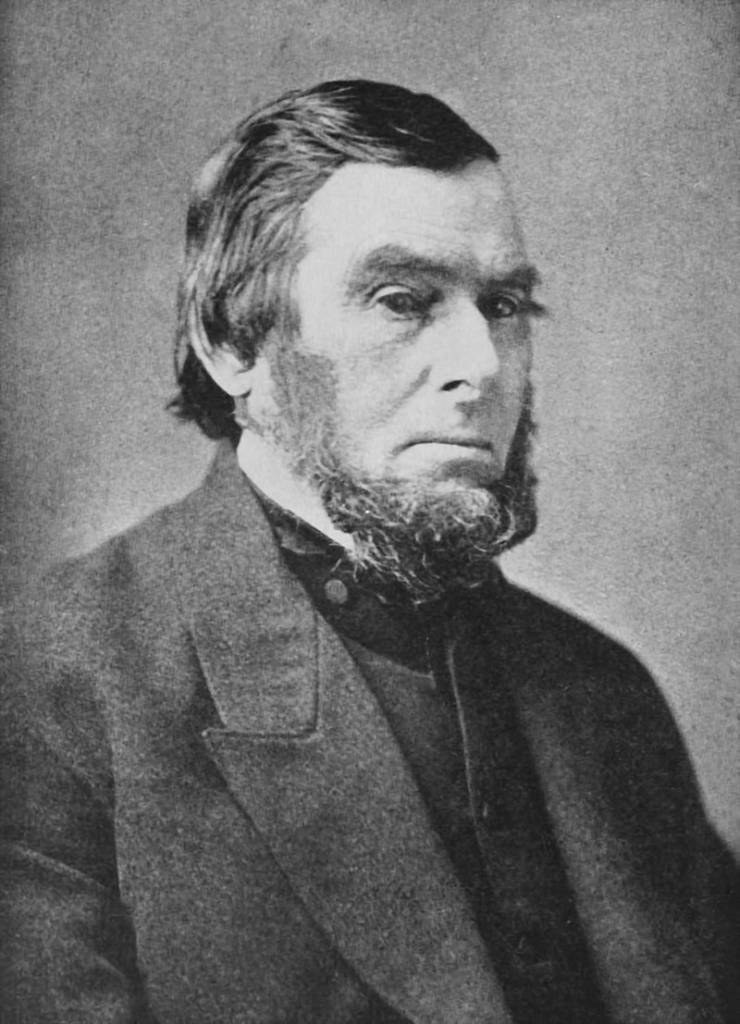

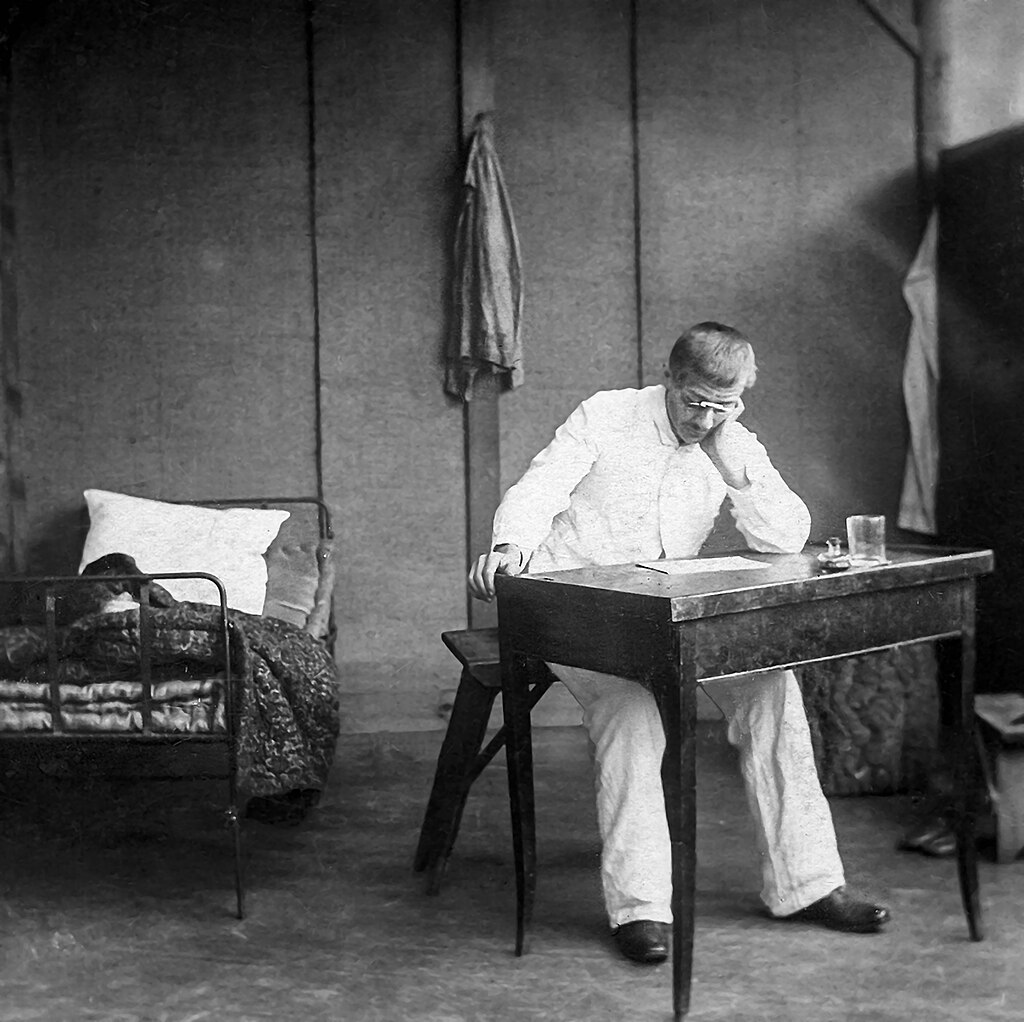

Devil’s Island was also notorious for being used for the exile of French political prisoners, with the most famous being Captain Alfred Dreyfus, who had been accused of spying for Germany.

Above: Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935)

The Dreyfus affair was a scandal extending for several years in late 19th and early 20th century France.

Above: Alfred Dreyfus in his room on Devil’s Island 1898

Above: The hut in which Dreyfus lived

- Trinidad

Above: Flag of Trinidad and Tobago

- Grenada

Above: Map of Grenada

Above: Flag of Grenada

- Newport

Above: Newport, Rhode Island, USA

- Fairhaven

Slocum’s return went almost unnoticed.

Above: Joshua Slocum route map: a journey of 46,000 miles

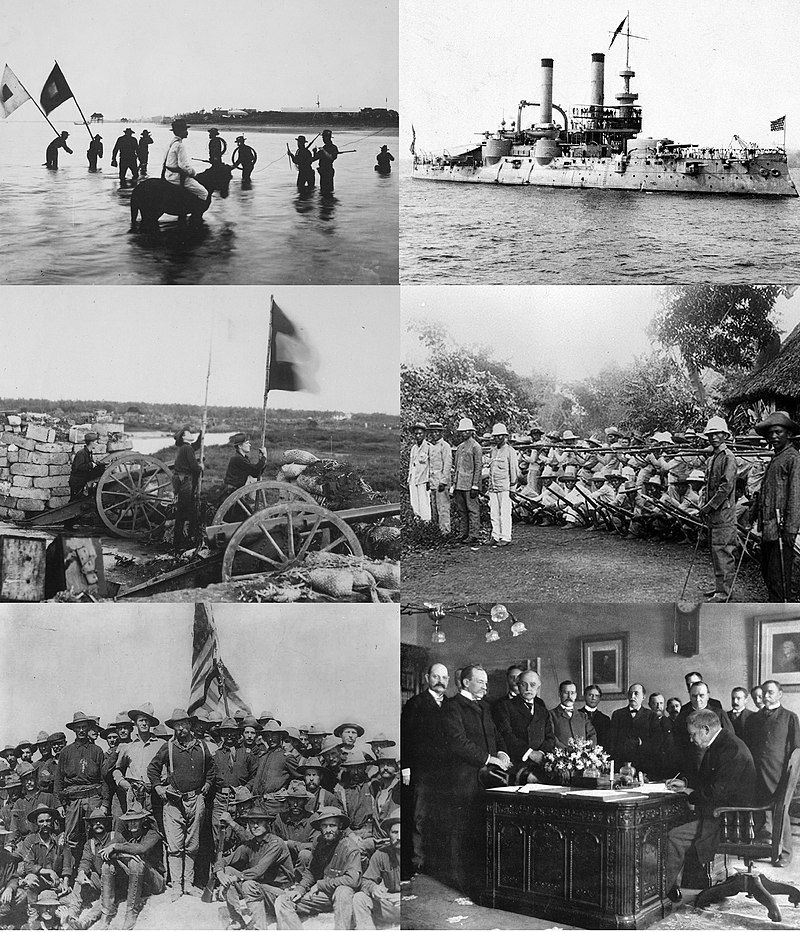

The Spanish–American War, which had begun two months earlier, dominated the headlines but, after the end of major hostilities, many American newspapers published articles describing Slocum’s adventure.

Above: Images of the Spanish-American War (1898)

In 1899, he published his account of the voyage in Sailing Alone Around the World, first serialized in The Century Magazine and then in several book-length editions.

Reviewers received the slightly anachronistic age-of-sail adventure story enthusiastically.

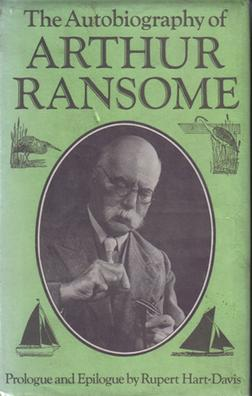

Arthur Ransome went so far as to declare:

“Boys who do not like this book ought to be drowned at once.”

Above: English writer Arthur Ransome (1884 – 1967)

In his review, Sir Edwin Arnold wrote:

“I do not hesitate to call it the most extraordinary book ever published.“

Above: English poet Edwin Arnold (1832 – 1904)

Slocum’s book deal was an integral part of his journey.

His publisher had provided Slocum with an extensive on-board library.

Slocum wrote several letters to his editor from distant points around the globe.

His Sailing Alone won him widespread fame in the English-speaking world.

Slocum hauled the Spray up the Erie Canal to Buffalo, New York, for the Pan-American Exposition in the summer of 1901.

Above: Buffalo, New York, USA

He was well compensated for participating in the fair.

In 1901, Slocum’s book revenues and income from public lectures provided him enough financial security to purchase a small farm in West Tisbury, on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, in Massachusetts.

Above: Slocum Farm, West Tisbury, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

After a year and a half, he found he could not adapt to a settled life.

He sailed the Spray from port to port in the northeastern US during the summer and in the West Indies during the winter, lecturing and selling books wherever he could.

Slocum spent little time with his wife on Martha’s Vineyard.

He preferred life aboard the Spray, usually wintering in the Caribbean.

Slocum and the Spray visited Sagamore Hill, the estate of US President Theodore Roosevelt on the north shore of Long Island, New York.

Above: Sagamore Hill, Long Island, New York, USA

Roosevelt and his family were interested in the tales of Slocum’s solo circumnavigation.

Above: US President Theodore Roosevelt (1858 – 1919)

The President’s young son, Archie, along with a guardian, spent the next few days sailing with Slocum up to Newport aboard the Spray, which, by then, was a decrepit, weather-worn vessel.

Above: US Army Lieutenant Colonel Archie Roosevelt (1894 – 1979)

Slocum again met with President Roosevelt in May 1907, this time at the White House in Washington.

Supposedly, Roosevelt said to him:

“Captain, our adventures have been a little different.”

Slocum answered:

“That is true, Mr. President, but I see you got here first.“

Above: The White House, Washington DC

By 1909, Slocum’s funds were running low.

Book revenues had tailed off.

He prepared to sell his farm on Martha’s Vineyard and began to make plans for a new adventure in South America.

He had hopes of another book deal.

On 14 November 1909, Slocum set sail in the Spray from Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, for the West Indies on one of his usual winter voyages.

He had also expressed interest in starting his next adventure, exploring the Orinoco, Rio Negro and Amazon Rivers.

Slocum was never heard from again.

In July 1910, his wife informed the newspapers that she believed he was lost at sea.

Despite being an experienced mariner, Slocum never learned to swim and considered learning to swim to be useless.

Many mariners shared this thought, as swimming would only be useful if land was extremely close by.

In 1924, Joshua Slocum was declared legally dead.

Above: Joshua Slocum

Slocum’s achievements have been well publicized and honored.

The name Spray has become a choice for cruising yachts ever since the publication of Slocum’s account of his circumnavigation.

Over the years, many versions of Spray have been built from the plans in Slocum’s book, more or less reconstructing the sloop with various degrees of success.

Similarly, the French long-distance sailor Bernard Moitessier christened his 39-foot (12 m) ketch-rigged boat Joshua in honor of Slocum.

It was this boat that Moitessier sailed from Tahiti to France.

He also sailed Joshua in the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race around the world, making good time, only to abandon the race near the end and sail on to the Polynesian Islands.

Above: French sailor Bernard Moitessier (1925 – 1994)

Ferries named in Slocum’s honor (Joshua Slocum and Spray) served the two Digby Neck runs in Nova Scotia between 1973 and 2004.

The Joshua Slocum was featured in the film version of Dolores Claiborne.

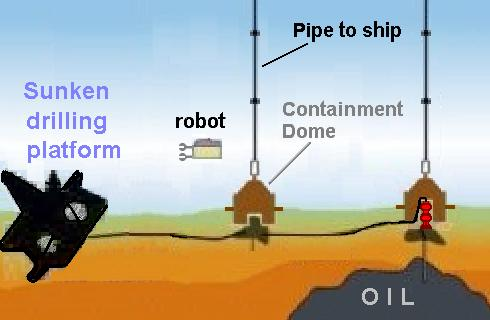

An underwater glider – an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), designed by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, was named after Slocum’s ship Spray.

It became the first AUV to cross the Gulf Stream, while operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Another AUV has been named after Slocum himself: the Slocum Electric Glider, designed by Douglas Webb of Webb Research (since 2008, Teledyne Webb Research).

In 2009, a Slocum glider, modified by Rutgers University, crossed the Atlantic in 221 days.

The RU27 traveled from Tuckerton, New Jersey, to Baiona, Pontevedra, Spain – the port where Christopher Columbus landed on his return from his first voyage to the New World.

Above: Maritime Museum, Tuckerton, New Jersey

Above: Baiona, Pontevedra, Spain

Above: Italian navigator Cristoforo Colombo (aka Christopher Columbus) (1451 – 1506)

Like Slocum himself, the Slocum glider is capable of traveling over thousands of kilometers.