Peace of Mind, Part One of Four:

Sunday 16 March 2025

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Landschlacht Bahnhof, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

“You must change your life.

You must change your life not for a particular reason or to achieve a particular goal, but because life is change.

To change one’s life means to be in harmony with life’s greatest truth.“

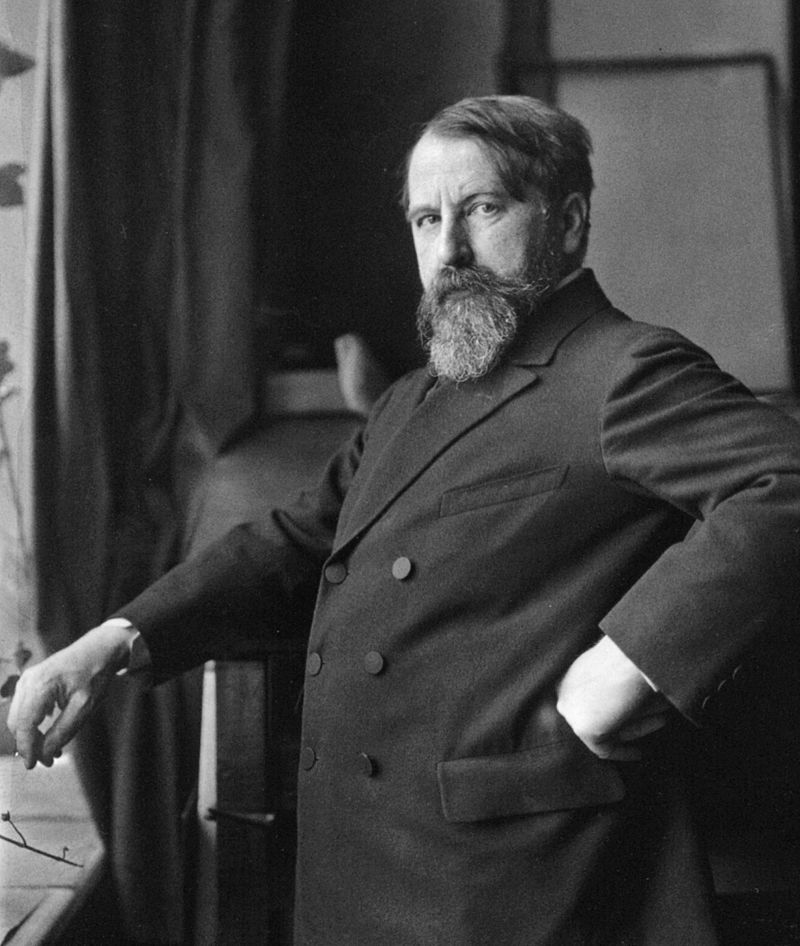

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

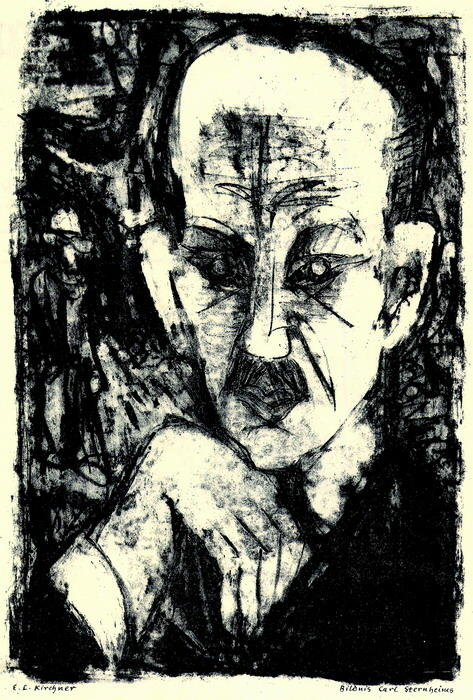

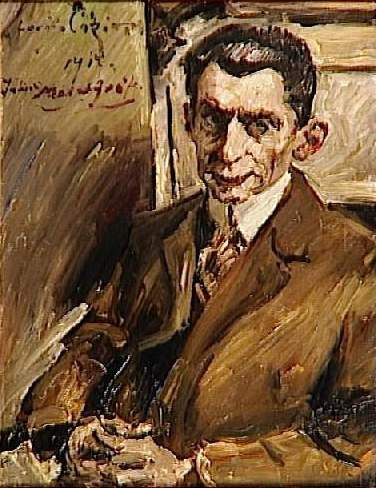

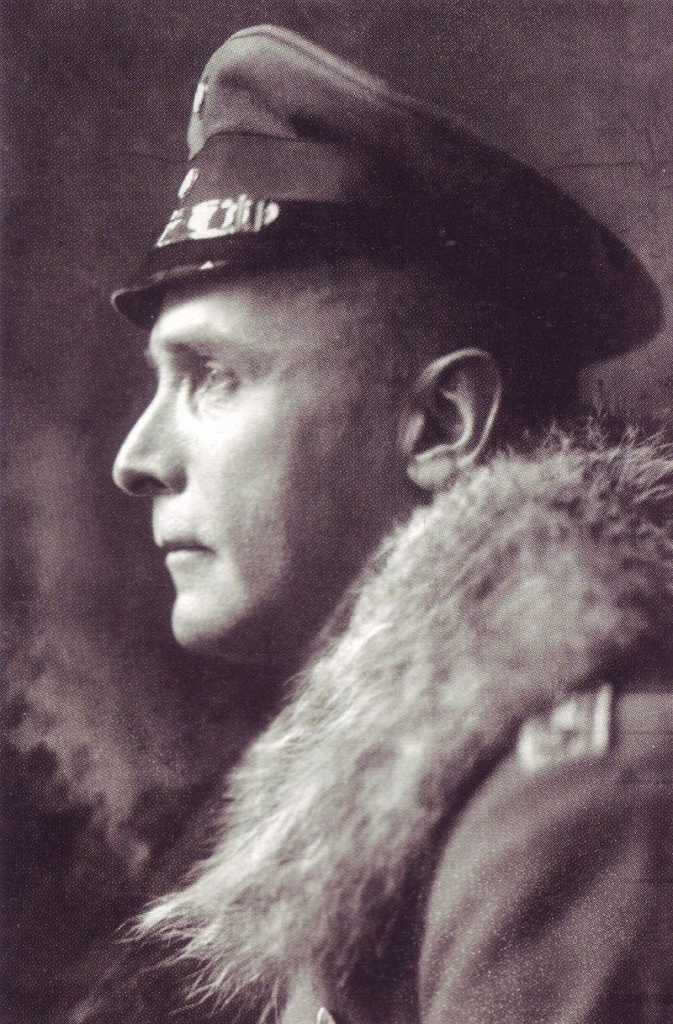

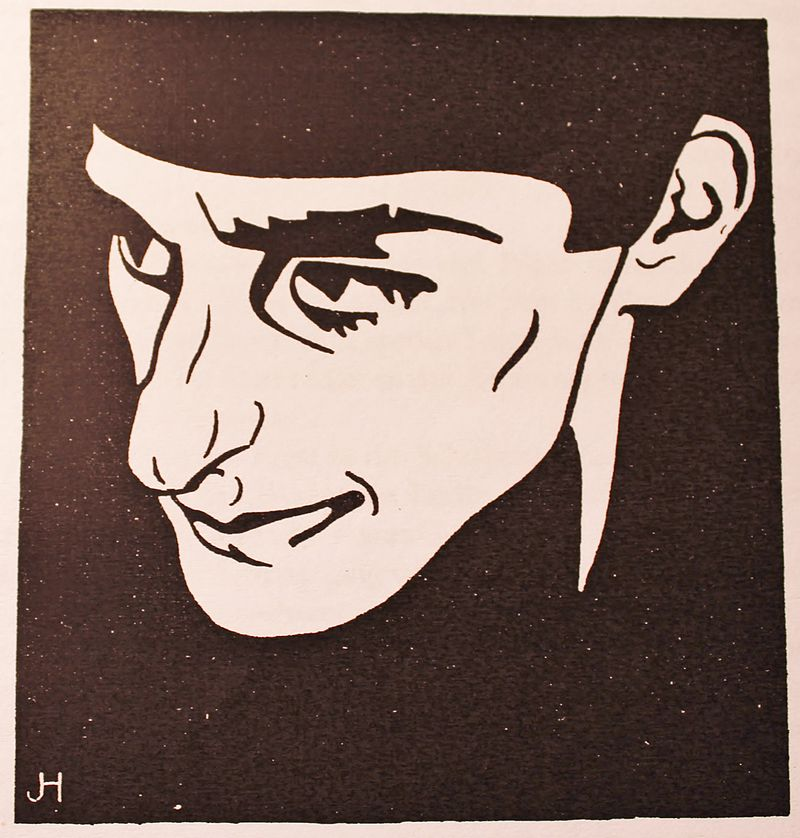

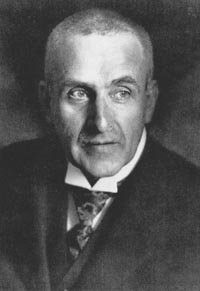

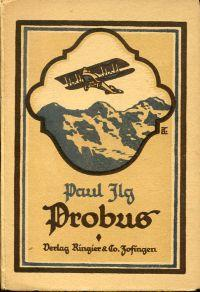

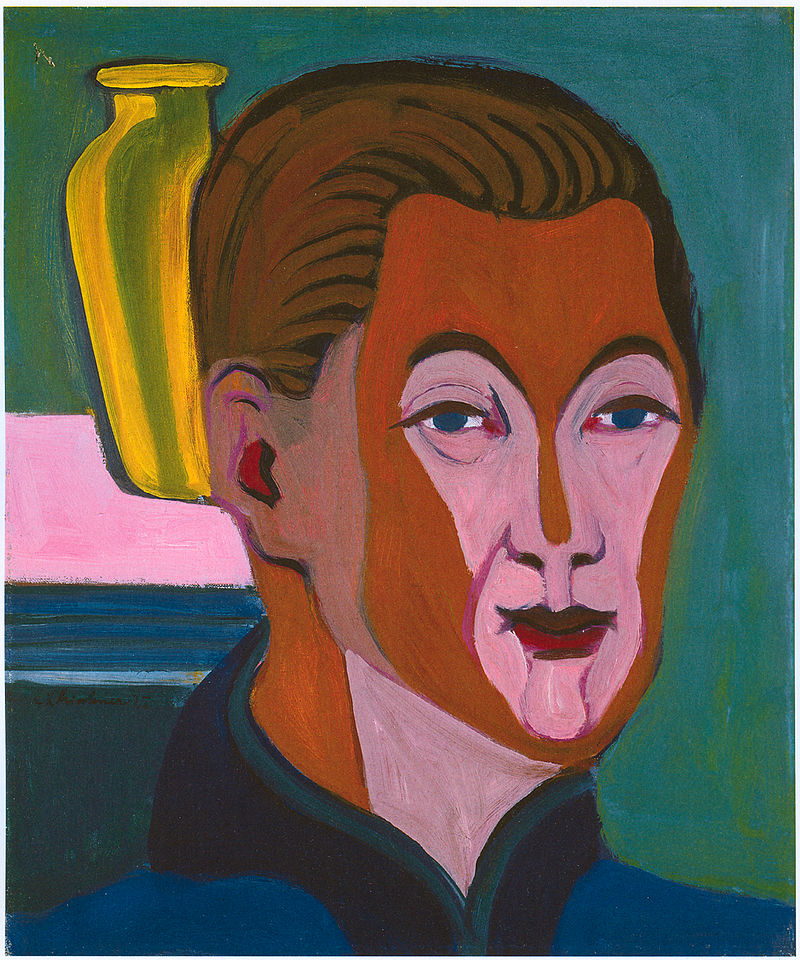

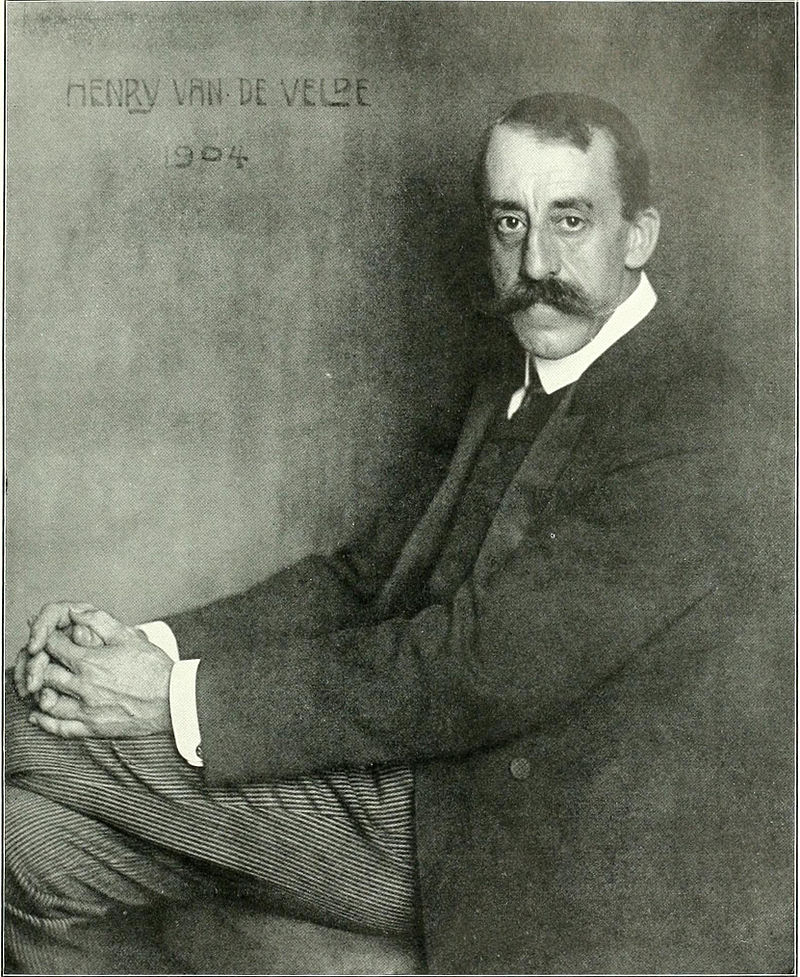

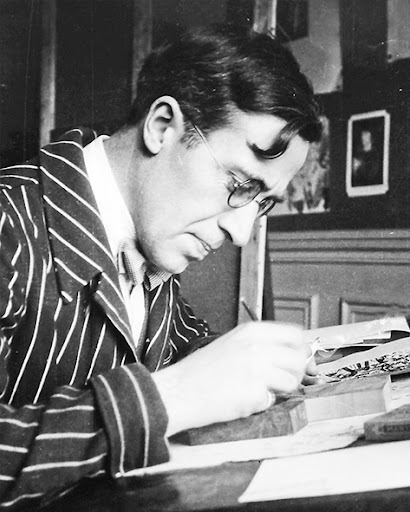

Above: Czech poet/novelist Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 – 1926)

Week Two of my involuntary exile from Türkiye begins today and I have spent much of this past fortnight, in “my” room in “our” apartment on Oberer Weg in the wee hamlet of Landschlacht, writing and reading like a man without a care in the world, as if already embracing an early retirement or a spontaneous sabbatical.

Above: Oberer Weg apartments, Landschlacht

I “work” a little bit – one online lesson on Monday and another on Tuesday, four on Wednesday and another on Frıday – seven hours per seven days.

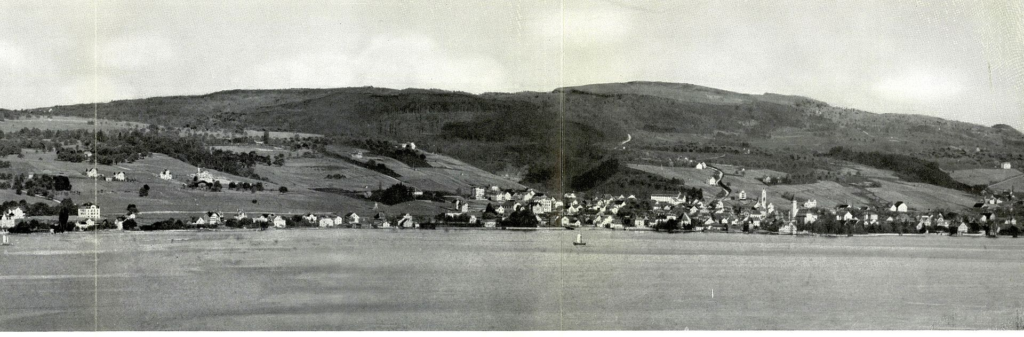

Above: Landschlacht

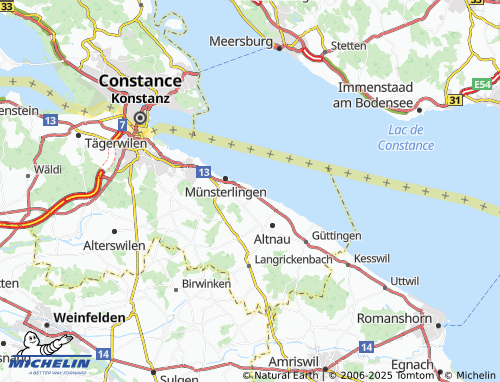

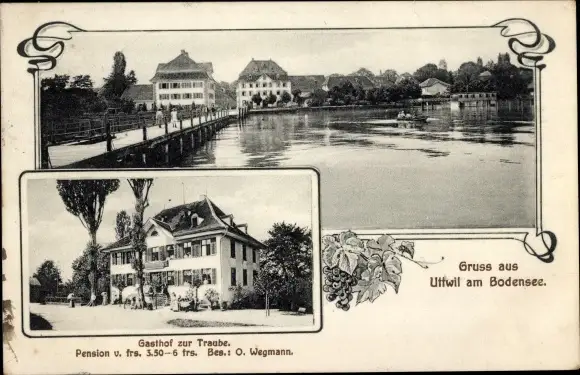

Though “our” apartment overlooks the magnificent Bodensee (Lake Constance) in the very beautiful (albeit expensive) country of Switzerland, I do not venture often out of “my” room.

Above: Bodensee (Lake of Constance), Landschlacht

To do so normally means to spend money and I am repeatedly reminded that the money I spend is not “our” money but rather “her” money for which She, as a doctor, works very hard to earn.

Last week I left the apartment to make only two excursions.

On Tuesday (11 March), I travelled to Heiden with the desire to visit the Henri Dunant Museum.

Above: Heiden, Canton Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Switzerland

On Thursday (13 March), I travelled to Konstanz, over the border in Germany, to do some shopping.

(I am planning to write a blogpost “The Road to Konstanz” in the near future.)

Above: Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Today in the process of chronicling the calendar – I have done the first 20 days of the second month of the year so far – I find myself motivated by the Museum visit in Heiden, the purchase of books in Konstanz, and, through my research, the works of Spanish poet José Zorrilla, French-American essayist/diarist Anaïs Nin and English-American poet W. H. Auden.

Above: Spanish poet/playwright José Zorrilla (1817 – 1893)

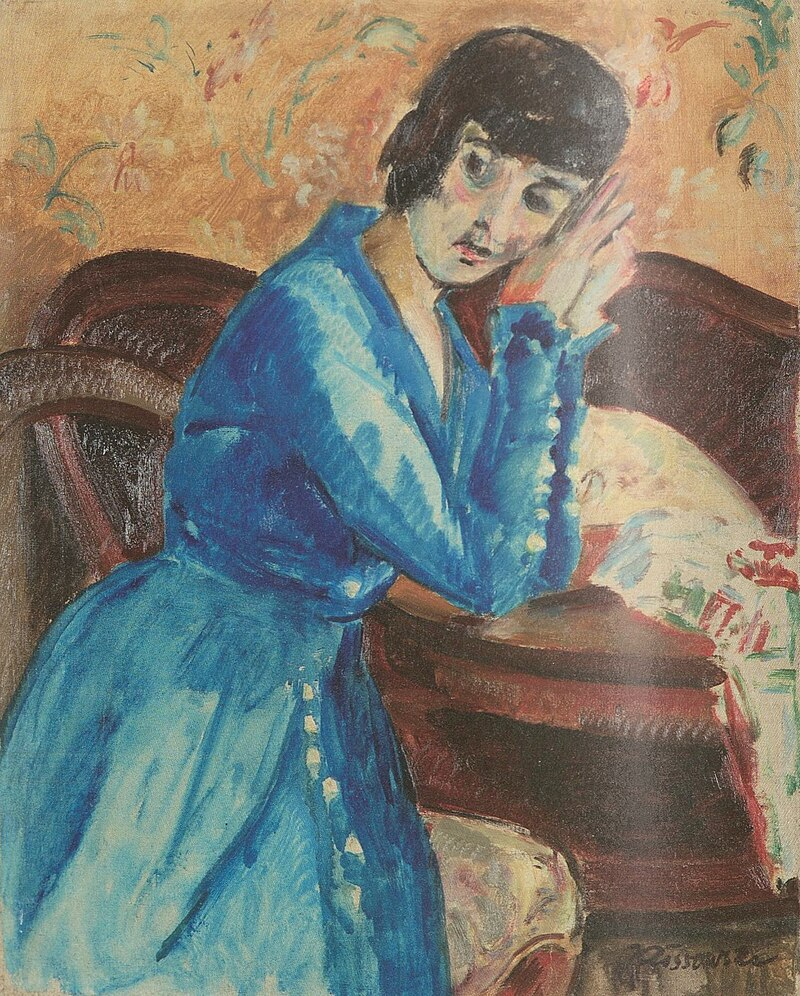

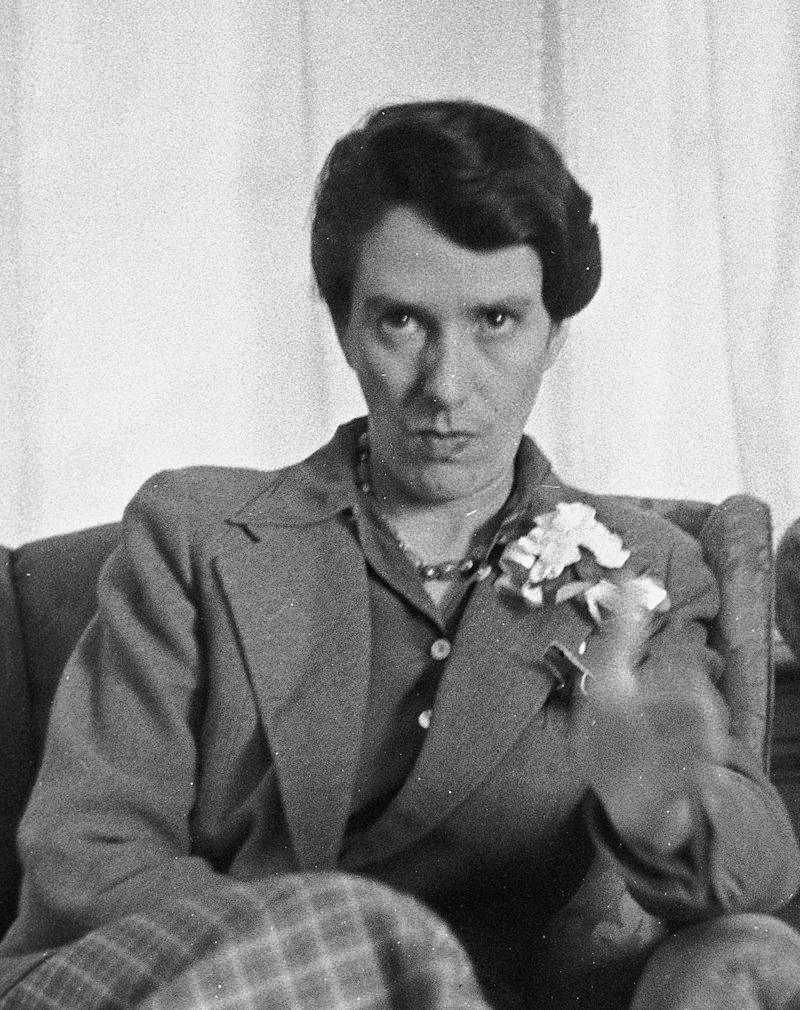

Above: French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist, and writer of short stories and erotica Anaïs Nin (1903 – 1977)

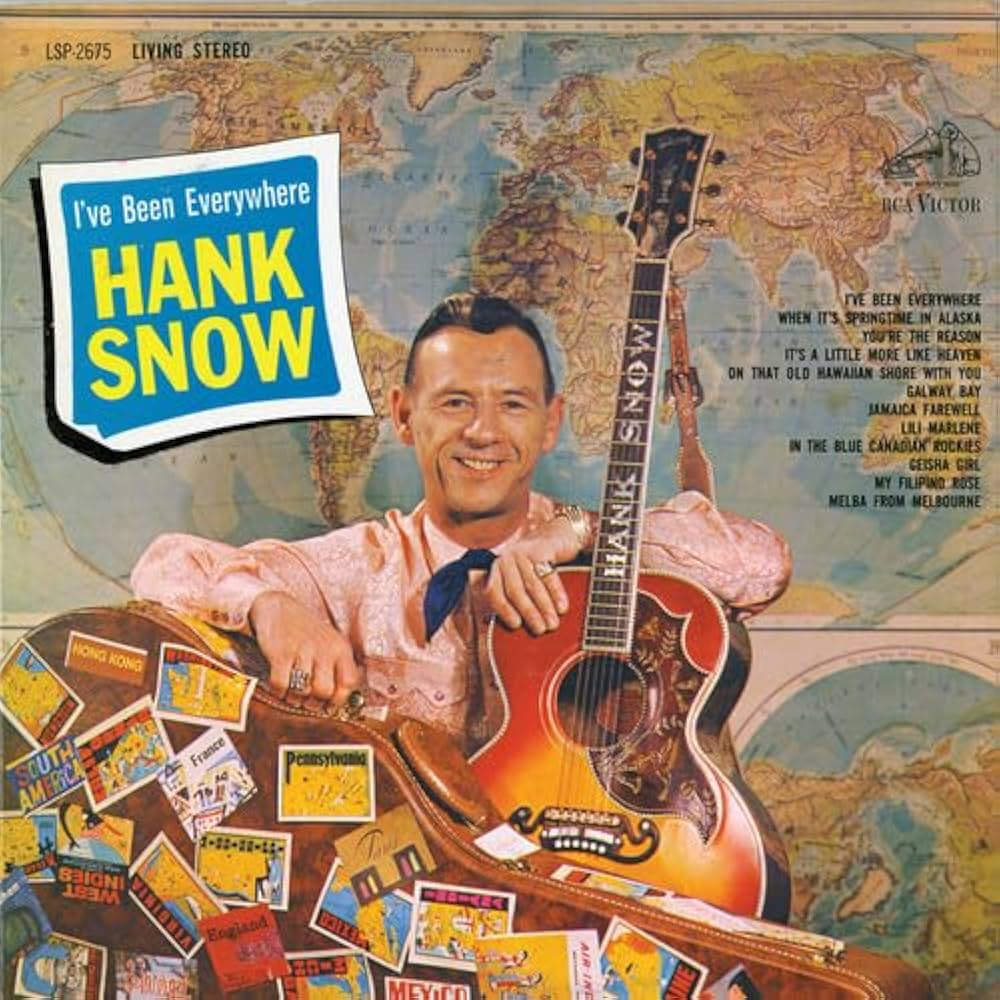

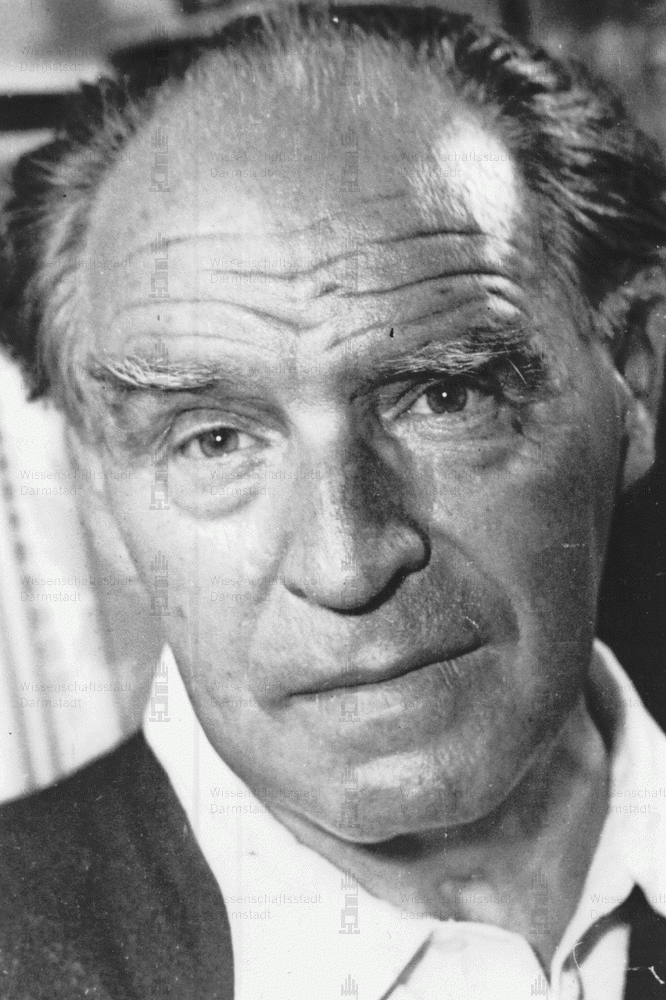

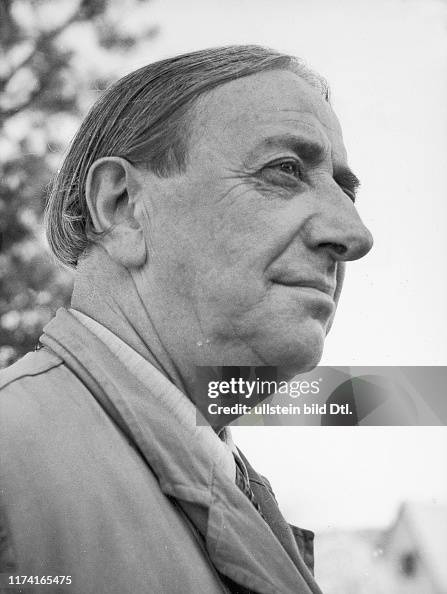

Above: British-American poet Wystan Hugh Auden (1907 – 1973)

What follows are observations about an area of the world wherein I have lived.

I will do this by tracing the routes I follow to reach destinations of the day, in the hopes of capturing the spirit of each place.

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1156 hours)

Landschlacht, Münsterlingen Municipality, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 1,494)

Above: Coat of arms of Landschlacht

There is not much I can really say about Landschlacht.

It is a peaceful holiday spot with the pretty half-timbered inn Rotes Haus and the house Zur Sonne.

Above: Restaurant Rotes Haus, Landschlacht

Above: Hotel Garni Sonne, Landschlacht

Yes, I lived there from 2011 to 2021, and, officially, I am still a dual resident of both Landschlacht and Eskişehir, Türkiye, from 2021 until March 2025.

(Hopefully I can resume living in Eskişehir when I return to Türkiye in June.)

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Türkiye

My wife is a doctor at the Thurgau Cantonal Hospital in the nearby village of Münsterlingen.

Above: Thurgau Cantonal Hospital, Münsterlingen

I lived with her in Landschlacht until the ongoing lack of teaching work compelled me to accept work in Eskişehir.

Landschlacht is on Highway 13 which begins in Schaffhausen and ends in Bellinzona.

Above: Schaffhausen, Switzerland

Above: Bellinzona, Canton Ticino, Switzerland

Landschlacht is on the SBB/Thurbo railway line between Schaffhausen and Wil.

Above: Logo of Swiss Federal Railways

Above: Logo of Thurgau-Bodensee Railways

Above: Wil, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

Post Buses run through Landschlacht and the village is the end stop of Konstanz (Roter Arnold) Busline 908 that runs through Münsterlingen, Scherzingen, Bottighofen, and Kreuzlingen and ends at Zähringerplatz in Konstanz, Germany.

Its sole claim to fame seems to be the St. Leonhard Chapel, built before 1000 and decorated with Gothic murals.

Above: St. Leonhard Chapel, Landschlacht

Above: Interior of St. Leonhard Chapel, Landschlacht

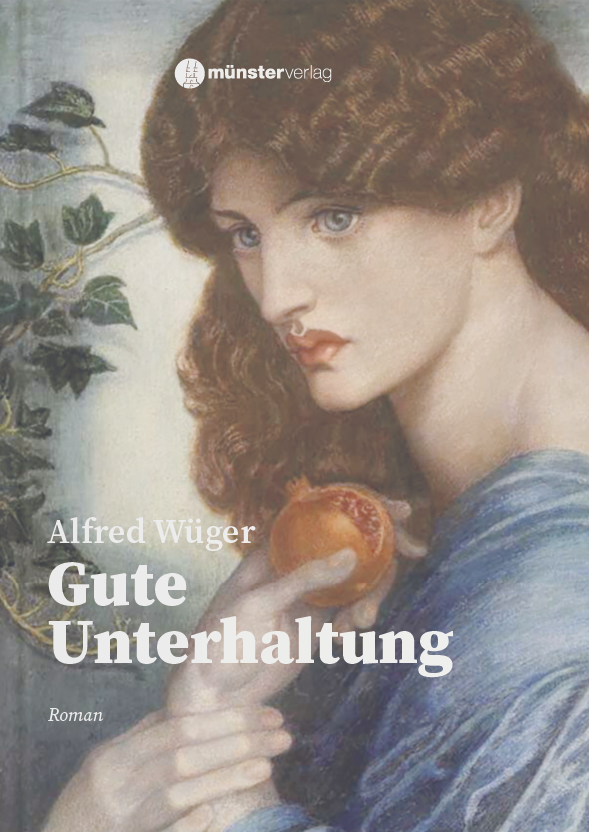

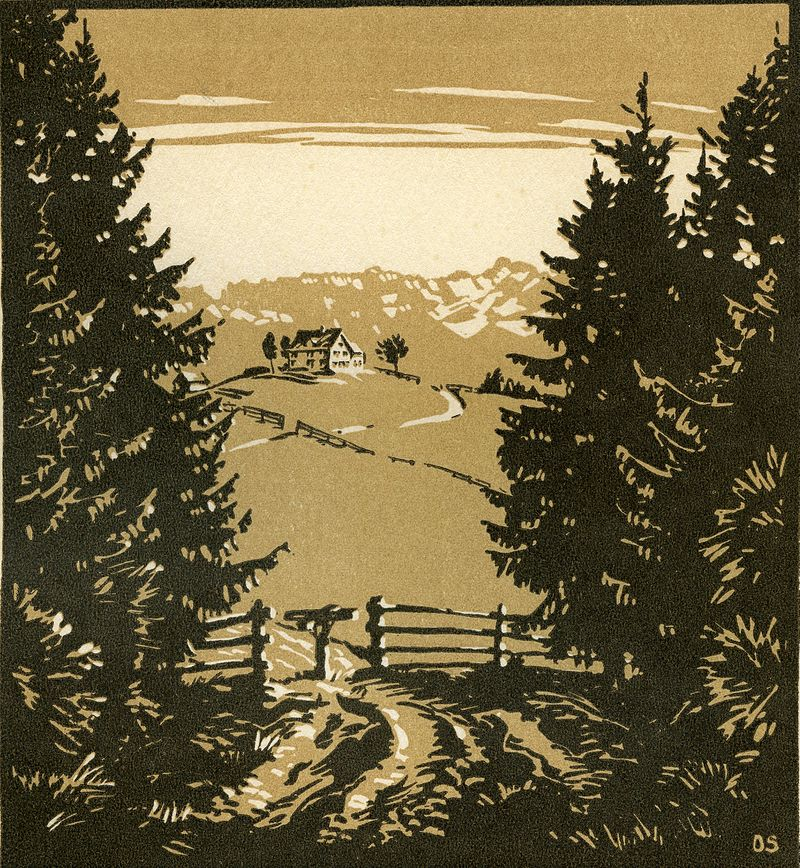

Landschlacht is the setting of Alfred Wüger’s novel

Gute Unterhaltung (Good Entertainment).

The novel Gute Unterhaltung depicts the emotional transformation that René Sernatinger undergoes after being overcome one morning by memories of a past love.

The day before, he had been on the Üetliberg near Zurich, where, in the fog, he had struck up a conversation with Max and Agatha Naujoks, siblings of Lithuanian descent.

The two are retired mathematics teachers and run a guesthouse in Landschlacht on Lake Constance.

The next day, Sernatinger spontaneously rents a room in Landschlacht, and dialogues ensue with his hosts:

- Vera, the waitress

- Joe, the landlord of the Transit

- Ugly Helene, who lives in the Münsterlingen Psychiatric Clinic,

- Adam Turtschi, a peasant figure who bears a striking resemblance to chess player Max Naujoks.

Existential issues are repeatedly discussed.

At the end, Sernatinger is able to say:

“I am now what I will become.“

Alfred Wüger doesn’t dedicate his book, but instead places a guiding motto before his novel:

“Avoid no one you meet.” (Goethe)

Above: German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1782 – 1832)

With that, everything is essentially said, including that Wüger delivers good entertainment, but not easy fare.

One might read his novel in one go, but shutting off your mind is not recommended.

Perhaps one could try to transition the mind into a different state, one in which the walk between fiction and reality feels particularly good.

Above: Swiss writer Alfred Wüğer

The story of René Sernatinger begins with a false promise — with dense fog in a place where there supposedly shouldn’t be fog — on the top of Zurich’s Üetliberg mountain.

Above: Uetliberg, Canton Zürich, Switzerland

But the main character of Alfred Wüger’s first novel Gute Unterhaltung does not escape the fog:

“I thought I was on a needle of rock in the middle of the raging ocean.”

Above: Uetliberg in the fog

The driven man is later swept, thanks to a random acquaintance, to a guesthouse on the Bodensee (Lake Constance), in a small town named Landschlacht.

This is the beginning of his adventure, tracing a lost love and the stormy longing for uncompromising passion — and the unheard-of hope that the lake might freeze for him again in the spring, creating a path to the distant, otherworldly shore.

During the Seegfrörnen (freezing of Lake Constance) the lake is covered with a layer of ice that can even support people.

The name for this condition is Seegfrörne in German.

The last part to freeze over, the Obersee, can then be crossed on foot from one shore to the opposite.

For Seegfrörne to occur on Lake Constance, an extremely cool summer, long lasting easterly winds and very cold weather in autumn and winter are necessary.

Then Lake Constance can freeze over completely in January or February.

The verifiable Seegfrörnen are an important climate archive for cold anomalies in Central Europe on this particularly large lake and can also be used to calibrate climate models.

The last time Lake Constance froze over completely was in the winter of 1962 – 1963.

Above: Lindau harbor in 1963 with a landed plane on the ice of the harbor basin and a car in the harbor entrance, Bavaria, Germany

Since 1573, every time the lake freezes over, as far as political circumstances and the ice’s capacity for a large crowd allow, the bust of Saint John (Apostle) has been carried in a ceremonial ice procession from the Swiss monastery of Münsterlingen to the German town of Hagnau on Lake Constance, and then back again the next time the lake freezes over.

John is considered a wine saint in Catholic communities and his feast day is December 27.

The wooden bust was dated to the beginning of the 16th century by Albert Knoepfli of Frauenfeld.

Above: Münsterlingen Monastery

Above: St. John the Baptist Church, Hagnau am Bodensee, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

The history of the ice procession from 1573 to 1830 is documented on the pedestal of the bust of John the Evangelist.

The frozen lake and ice procession of 1830 were described by Heinrich Hansjakob in his book Schneeballen vom Bodensee.

The ice procession is depicted as a detail in the “Schneeballensäule” (snowball column) monument in the center of Hagnau.

Above: Schneeballensäule, Hagnau am Bodensee

Pictures of the ice procession of 1963, in which the bust was carried from Hagnau to Münsterlingen, are included in the book Seegfrörne by Werner Dobras and in the book Über eisige Grenzen by Diethard Hubatsch.

The Hagnauer Museum in Hagnau on Lake Constance documents the origins of the ice procession and the crossings of the lake between Münsterlingen and Hagnau.

M

Above: Hagnauer Museum, Hagnau am Bodensee

Meichle pointed out in 1963 that he had not found any documents relating to the frozen lakes before 1830 in either the Hagnau municipal archives or the General State Archives of Karlsruhe.

“The origin and background of this long-standing custom, however, remain obscure.

No explanation has yet been found in the surviving documents from the 16th to 18th centuries as to why — in mutual agreement on both sides of the shore — the decision was made to carry a bust of Saint John across the ice, back and forth.

It also remains unclear when the first of these processions actually took place.”

– Diethard Hubatsch: Across Icy Borders (2012)

Above: Bust of John the Baptist

Above: Interior of St. Remigius Church in Münsterlingen with a bust of St. John

Wüger referred to his work as a love story before the book launch.

However, the passages Alfred Wüger read aloud that evening with pointed theatricality were full of infectious cheerfulness.

Above: Alfred Wüger

There is eating and drinking, lamenting and philosophizing about life and the afterlife, as if one were in a play by Dürrenmatt.

Above: Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921 – 1990)

In the village and pub, true life plays out, the lake becomes the Styx, and Persephone herself leads the seeker across.

Styx was the oath of the gods.

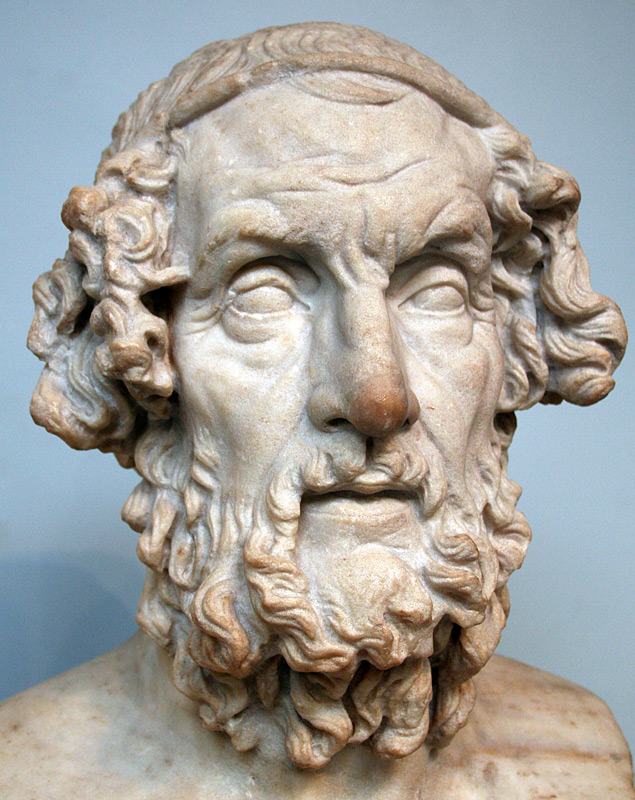

Homer calls Styx the “dread river of oath“.

In both the Iliad and the Odyssey, it is said that swearing by the water of Styx, is “the greatest and most dread oath for the blessed gods“.

Homer has Hera (in the Iliad) say this when she swears by Styx to Zeus, that she is not to blame for Poseidon’s intervention on the side of the Greeks in the Trojan War.

He has Calypso (in the Odyssey) use the same words when she swears by Styx to Odysseus that she will cease to plot against him.

In the Odyssey, Circe says that the Underworld river Cocytus is a branch of the Styx.

Hypnos (in the Iliad) makes Hera swear to him “by the inviolable water of Styx“.

In the Iliad the river Styx forms a boundary of Hades, the abode of the dead, in the Underworld.

Athena mentions the “sheer-falling waters of Styx” needing to be crossed when Heracles returned from Hades after capturing Cerberus.

Patroclus’s shade begs Achilles to bury his corpse quickly so that he might “pass within the gates of Hades” and join the other dead “beyond the River“.

Above: Bust of Greek poet Homer (8th century BC)

So too in Virgil’s Aeneid, where the Styx winds nine times around the borders of Hades.

Above: Bust of Roman poet Virgil (70 – 19 BC)

The boatman Charon is in charge of ferrying the dead across it.

More usually, however, Acheron is the river (or lake) which separates the world of the living from the world of the dead.

Above: Charon carries souls across the river Styx, Alexander Dmitrievich Litovchenko (1861)

In Dante’s Inferno, Phlegyas ferries Virgil and Dante across the foul waters of the river Styx which is portrayed as a marsh comprising the Hell’s Fifth Circle, where the angry and sullen are punished.

One of the impossible trials which Venus imposed on Psyche was to fetch water from the Styx.

Apuleius has the water guarded by fierce dragons, and from the water itself came fearsome cries of deadly warning.

The sheer impossibility of her task caused Psyche to become senseless, as if turned into stone.

Jupiter’s eagle admonishes Psyche saying:

Do you really expect to be able to steal, or even touch, a single drop from that holiest — and cruelest — of springs?

Even the gods and Jupiter himself are frightened of these Stygian waters.

You must know that, at least by hearsay, and that, as you swear by the powers of the gods, so the gods always swear by the majesty of the Styx.”

Above: Italian writer Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321)

The great strength of the novel lies in those moments where new things emerge from the ruins of dream and reality.

In conversation Wüger, the long-time journalist, reveals a completely unjournalistic credo:

“The feeling is the same in both dream and reality.”

Wüger sees the coincidence of his upcoming retirement and the release of his first book — as he has always written, but this is his first published work — as fate.

He wrote this story 20 years ago, in a storm of emotions and fervor that still defines him today.

Therefore, in parts, it’s a very personal story.

However, he doesn’t like to interpret anything into it:

“The source of emotions is uncontrollable.”

As an observer, he wanted to maintain distance.

Above: Landschlacht

Thus, the unusual title Gute Unterhaltung came about:

“I gave myself the greatest creative freedom with it,” says Wüger.

The clear, rich sound of the language is striking, with which the author skillfully captivates the audience right away.

Even loyal readers of his reports are surprised:

“I’ve never experienced him this emotional, I’m overwhelmed,” says Malou Leclerc, founder of the former dance group Cinevox Junior Company.

The improvised musical accompaniment to the excerpts by Bernie Ruch on drums and Michael Streif on cello gives the reading an additional, almost hypnotic component.

Their collaboration is a first for them, as the two musicians explain.

They plan to continue accompanying Alfred Wüger on his readings.

However, it might sound very different next time:

“We are seekers too,” says Ruch, laughing.

“Helene, tell me, do you actually invent these stories?”, asks the main character, René Sernatinger, of his conversation partner, after she has just told him about one of her walks along the mythical border river Styx, where she spoke with a suicide.

She laughs and answers, no, she reads a lot.

But only secretly.

When Sernatinger wants to know why, she says:

“So no one comes and asks if I understand everything.”

Perhaps Alfred Wüger’s first novel Gute Unterhaltung is also a book best read secretly.

Because one will hardly understand everything after reading it.

The story takes place at Lake Constance, in a small village called Landschlacht, and revolves around a man on a search.

What is he searching for?

For faith?

For his lover Isabelle, to whom he constantly writes letters?

For meaning?

For death?

The protagonist, Sernatinger, doesn’t seem to know exactly either.

The largely letter- and conversation-driven plot does not have a structure that can be divided into reality and fiction, but rather features several intertwined strands of reality that sometimes even contradict each other.

There are villagers, but also Greek gods and mythical figures.

Sometimes, Lake Constance is simply a lake with ducks swimming, and other times, it is the boundary to the underworld, which Sernatinger must cross with the goddess Persephone to usher in spring.

And finally, a large portion of Christian theology is mixed into the whole.

No question:

Wüger has literary talent.

However, as a reader, one might have wished for a slightly stricter editorial review at times.

The novel, which the journalist claims to have written 20 years ago, has two weaknesses:

One is linguistic.

There is this earthy Swiss undertone with Helvetisms like “Holzrugel” (wooden rattle) or “Gümpli” (meaning a small jump).

Above: Flag of the Helvetic Confederation of Switzerland

This wouldn’t be disturbing in itself if this style were consistent throughout or at least assigned to specific characters.

But in the same breath, Wüger uses overly elaborate language that no one would ever actually speak.

For instance, Sernatinger says to a father whose son is just trampling a swan’s nest:

“So, finally put an end to this with your son!”

As a reader, you get no sense of how the characters speak, as the linguistic subtleties are missing.

The second weakness is content-related.

Although Gute Unterhaltung is a highly convoluted and open-to-interpretation novel, the author sometimes explains too much.

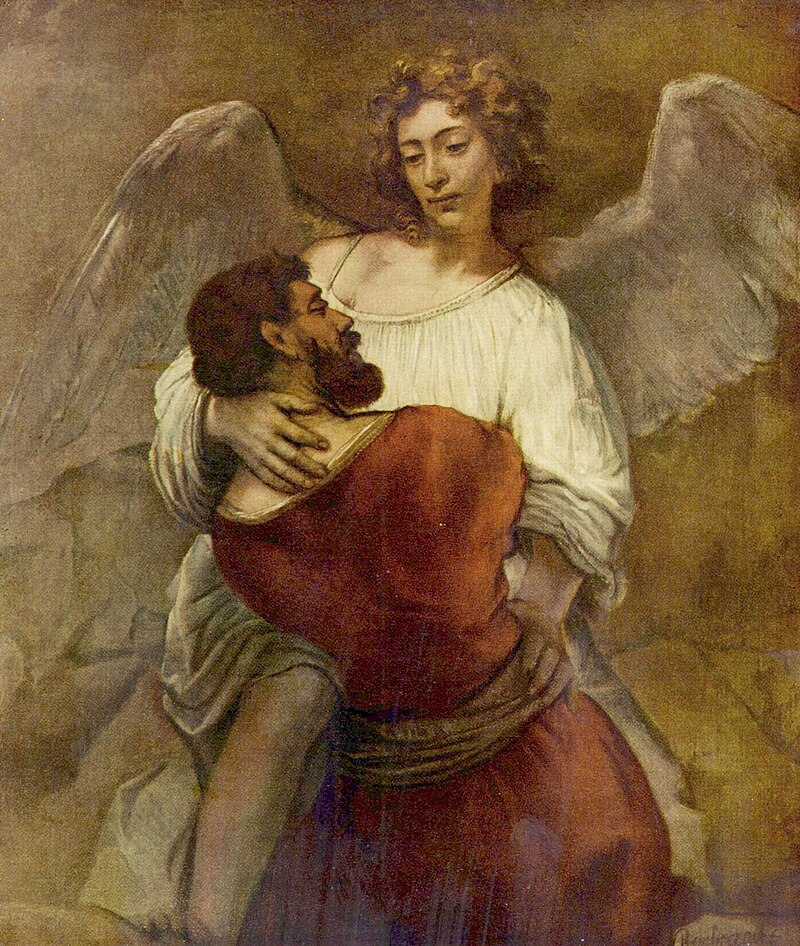

When, for example, the protagonist struggles with a stranger all night until dawn breaks, a half-versed Bible reader immediately recognizes the reference to Jacob’s struggle with God.

The following direct quote, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” is unnecessary here.

It comes across as exaggerated and almost gives the impression that the reference is only there to prove the author’s erudition (which Wüger, as a trained theologian, doesn’t need to do).

Above: Jacob wrestles with the angel, Rembrandt (1659)

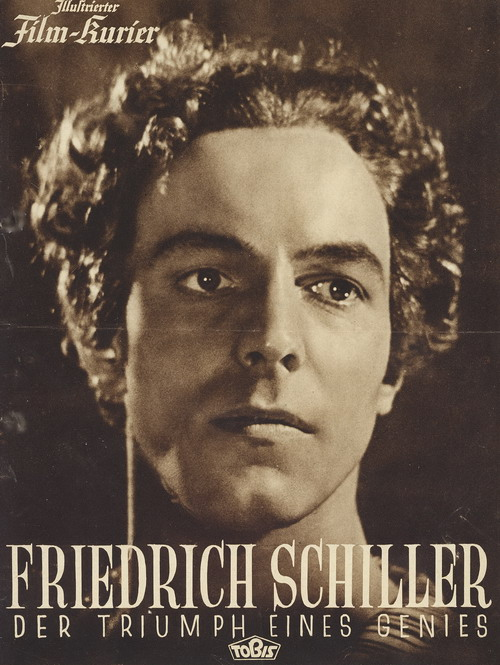

When references are merely there to embellish, when the Lake only smiles because it smiles in Schiller’s works too, then they are superfluous.

Above: German writer Friedrich Schiller (1759 – 1805)

But apart from these weaknesses, Gute Unterhaltung delivers what the title promises.

Especially because the novel mixes so much.

It is a work for those who like to pause while reading and remain puzzled when they close the book.

Leonard Hofstadter (Johnny Galecki): “I thought you were reading.“

Amy Farrah Fowler (Mayim Bialik): “I was. Now I’m thinking about what I read.“

Scene from The Big Bang Theory (2007 – 2019)

My time in Landschlacht is the result of a flaw in my character:

The ease with which I have relied on the opinions and advice of others – in particular, my wife’s.

Relying on the opinions of others is detrimental in any effort to become who we should be.

The opinions of others may provide direction, but they also distract us from our own true purpose.

This purpose can only be determined by deep and unflinching inner reflection.

The questions are basic.

What should I do?

What can I do?

What can be my place in the world?

Can I avoid pain or disappointment?

Where can I find joy?

How should I love?

How should I treat the opposite sex?

Why is love difficult?

What career should I pursue?

Most importantly, it is important to resist the urge to quickly resolve the questions that haunt us.

We need to examine solitude and pain diligently, rather than avoid those experiences, as we are all naturally inclined to do, due to their obvious unpleasantness.

Both I and my wife have lived apart for the past four years, with the exception of video calls and mutual vacations.

We have come to embrace our individual experiences of living in solitude.

She shares her pain with me, knowing that she will probably not share my opinions nor heed my advice.

I do not share my pain with her, for she will bombard me with opinions and advice, which I prefer to formulate on my own despite the inherent wisdom of her words.

There has always been an inequality between us both in love and in income.

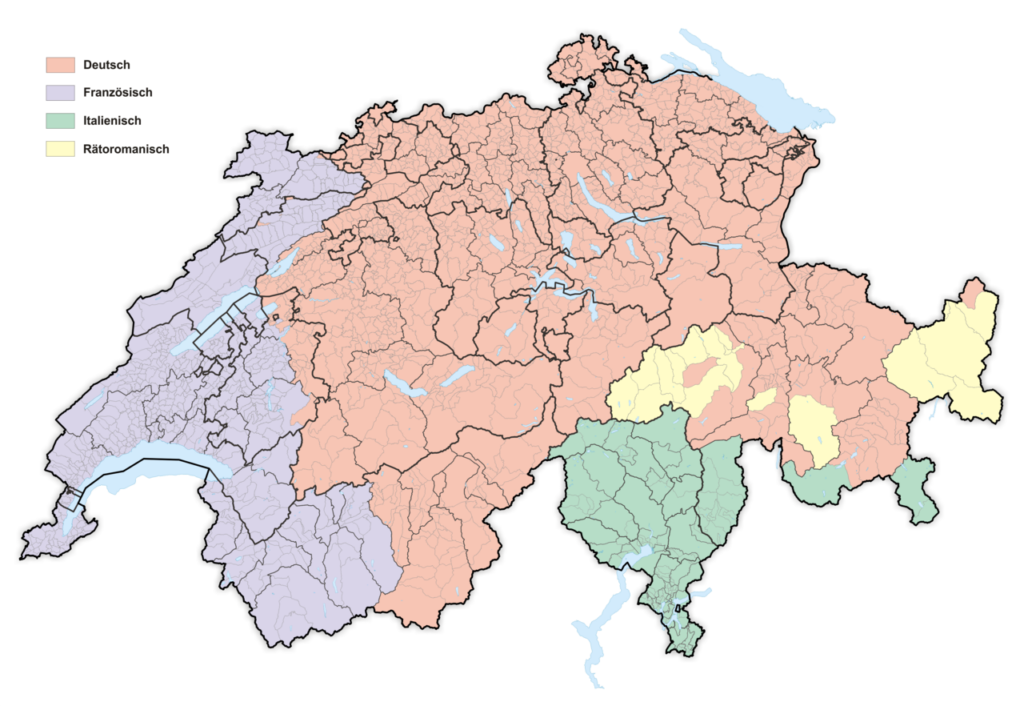

Switzerland for me, and before that Germany, is a land of societal convention that equate love and sexuality with either the satisfaction of physical urges or the repression of these for fear of embarrassment and awkwardness.

It has been easier to deny the physical in favor of the fear.

Where we also diverge from one another is the enormous pressure and grave difference between choosing a career and following a vocation.

To become the doctor my wife became demanded discipline and dedication.

I fell into teaching and have drifted towards writing.

She followed her dreams with determination.

I have hesitantly hoped.

I have longed for companions that exhort me to take my hopes and aspirations seriously, that urge me with unflagging urgency to keep writing, that my life really truly matters.

Not as a cog in the machinery of others, but as my own self-driven engine.

I need to find the drive from within because the world outside myself will not provide it.

Above: Charlie Chaplin, Modern Times (1936)

I need to follow the inexplicable inner passion without trying to passionately defend to the uncomprehending that which they neither can nor wish to comprehend.

In the places I have experienced I discover the lives of others and see that they, like myself, try to do the remarkable to win acclaim, compensation or self-acceptance through the construction of designs that they themselves never made.

I have found that everyone, everything, is either a blessing or a lesson.

Sometimes both.

I find myself thinking of those who seek to find their proper place in the world by relying on religion, ideology or political belief – three columns of custom that invariably collapse and crush the individual’s spirit within.

We live in a difficult age, an age where the Internet seeks to seduce, corrupt and engulf us in the great mass movements of the moment.

Movements that promise stability, cohesion and a shared identity but invariably fail due to vast economic, social and political reality.

Movements of the moment generally last only for a moment.

“Our” apartment faces the Bodensee.

True North.

And, in a way, True North, a very Canadian concept woven even into our national anthem (Oh. Canada), may be the moral compass I seek.

Above: Flag of Canada

The Lake suggests introspection that could create a foundation on which to determine my social and moral relationship to a world and a time of increasing social pressure to conform.

My thoughts cannot prevent the great political and human catastrophes that inevitably arise, but perhaps this quarterly sabbatical may guide me in my efforts to think concretely about my own life, especially when a deeply contemplative life seems ever harder to achieve with the increasingly louder emphasis on commercial success and social recognition of one’s existence in our present reality.

Above: US President Donald Trump – He Who Will Not Be Ignored

By examining a place for what it was and for what it is, through the people who were and are in that place, I seek to understand the world from all possible angles.

I do not possess an aura of wisdom inaccessible to all nor am I a cliché of a misunderstood rebel without a cause or a clue.

I “simply” seek to answer the most personal intimate questions that no one can answer for me but myself.

I strive to align all aspects of my life with the purpose I myself wish to give it, to live my life as authentically as I can.

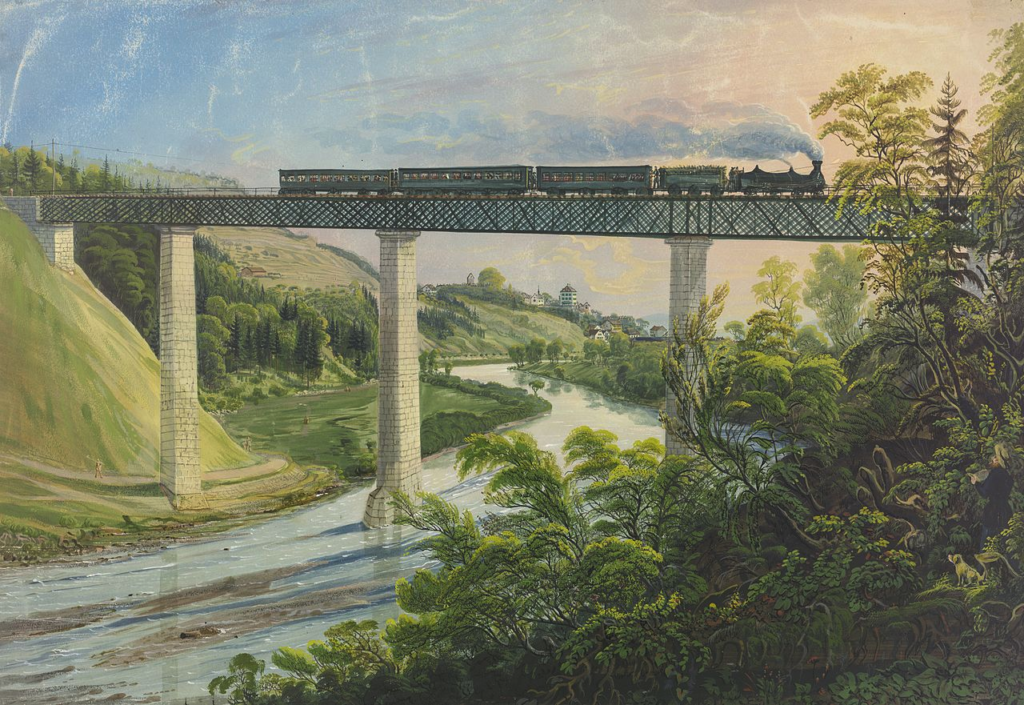

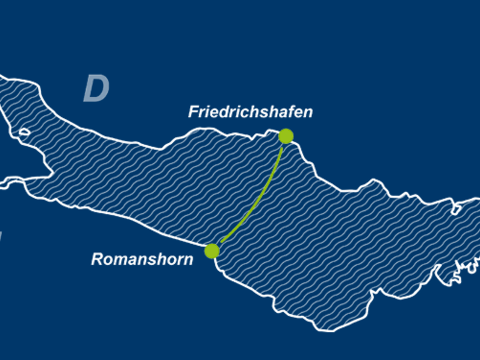

Three trains (and four blogposts) to get to and explore Heiden are needed:

- Landschlacht to Romanshorn

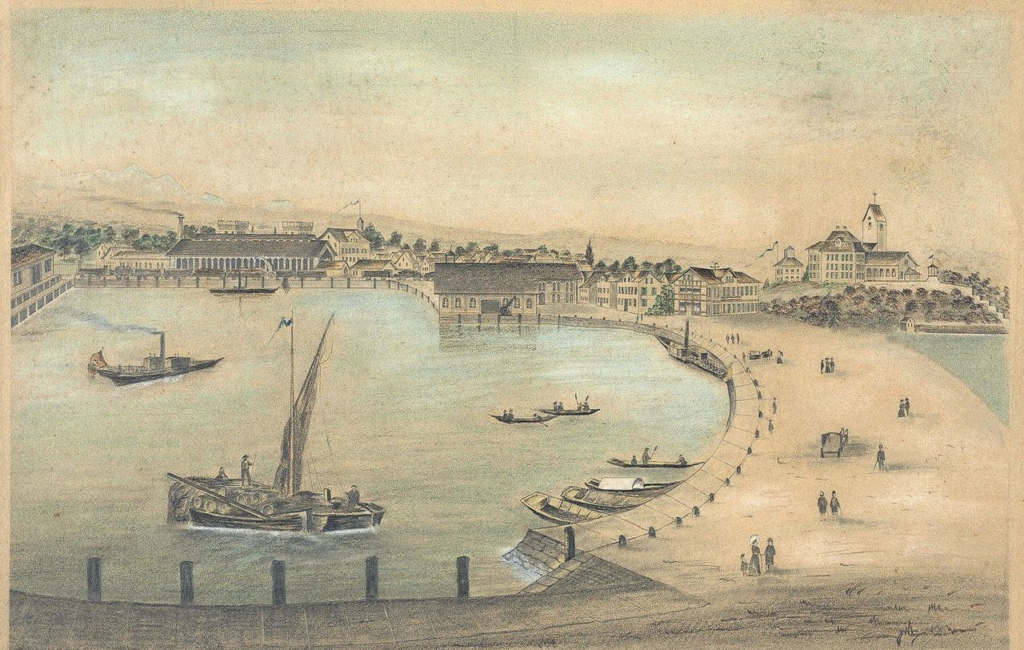

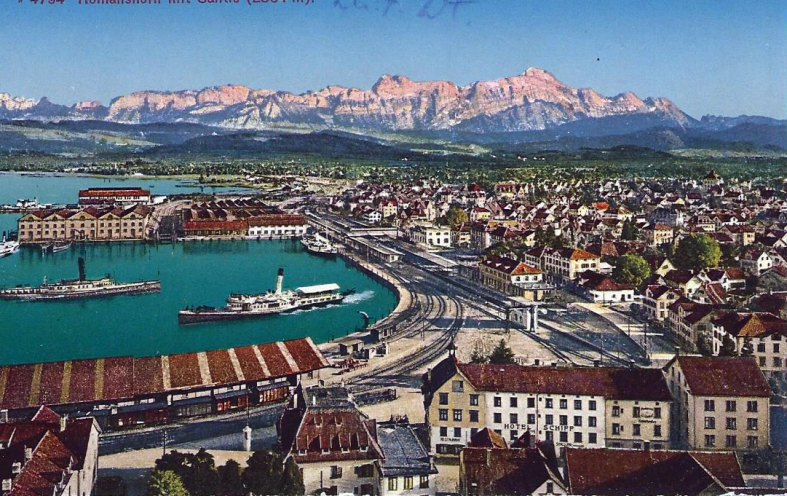

Above: Romanshorn, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

- Romanshorn to Rorschach

Above: Rorschach Bahnhof

- Rorschach to Heiden

Above: Heiden Bahnhof

In this blogpost a few words about the places seen en route from Landschlacht to Romanshorn:

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1156)

Altnau, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 2, 348)

Above: Coat of arms of Altnau

The church village, consisting of the upper and lower villages and other settlements, lies on the old Romanshorn – Kreuzlingen road near the southern shore of Lake Constance on the moraine of the former Rhine glacier.

The actual town center of Altnau lies about two kilometers from the shore of Lake Constance, at 471 m above sea level.

It borders the communities of Güttingen, Langrickenbach and

Münsterlingen.

Above: Altnau

Altnau has a train station on the Kreuzlingen – Romanshorn railway line.

Above: Altnau Bahnhof

Near the hamlet of Ruderbaum, the remains of a Horgen culture settlement have been discovered.

Below the Horgen site, there also may be a Pfyn culture site, but that is less certain.

The modern village of Altnau may be first mentioned in 787 as Althinouva.

In the 8th century the Abbey of St. Gall owned most of the land in Altnau.

Above: Abbey of St. Gallen

In 1155, Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa confirmed that the Cathedral of Constance owned the church and church yard in the village.

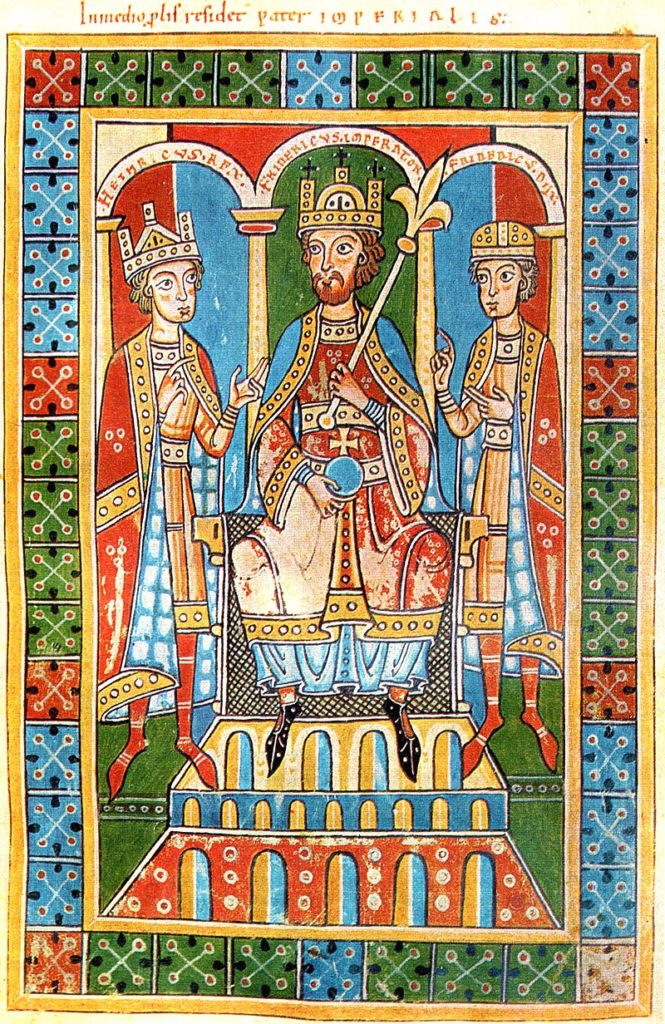

Above: Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122 – 1190) enthroned with a crown, imperial orb and scepter between his sons Henry VI (1165 – 1197), who already wears the royal crown (left), and Frederick of Swabia (1167 – 1191) with a ducal hat.

Above: Konstanz Münster (Constance Cathedral), Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

The vogt (legal) right over the church’s farms belonged to the Freiherr of Altenklingen after 1300.

Above: Altenklingen Castle, Wigoltingen, Canton Thurgau

During the Late Middle Ages, this right was given to several noble families from Konstanz and from 1471 until 1798 the city of Konstanz directly controlled the farms.

Above: Altnau landscape

In 1454 the villagers were represented in the Appenzell Landrecht (Pact), but following complaints from Konstanz they were forced to give up their membership.

Above: Coat of arms of Canton Appenzell

The rights of the village are first listed in the Gerichtsoffnung of 1468.

The right to administer the parish of Altnau went from the cathedral’s provost to the cathedral’s dean in 1347.

After the Protestant Reformation in 1528, the few remaining Catholics were looked after by Konstanz and the village church became a shared church.

This situation remained until 1810 when two churches were completed.

Above: Altnau

Until the 19th century, most of the local economy revolved around three-field agriculture.

About 1880 a dairy company was founded in the village.

Livestock and cheese production became common.

Viticulture was common from the Middle Ages until 1912.

In 1840 the Seestrasse (Lake Road) was built.

In 1870, the Seetalbahn (railroad line) was added.

However, neither road nor railroad led to a boost in the local economy, as the station was too far away.

- The Apfelweg (Apple Way) is Switzerland’s first fruit trail.

The nine-kilometer-long circular trail leads through the local orchards and explains the apple’s journey from blossom to fruit on 16 panels.

- The boat landing stage, which has existed since 2010, is 270 meters long due to the wide shallow water zone – making it the longest jetty on Lake Constance.

Above: Boat landing stage, Altnau

The people of Altnau also call this jetty the “Eiffel Tower of Lake Constance” because its length is as long as the Eiffel Tower is high.

Above: Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

I have painstakingly followed the Apfelweg before and have read all its signage that tries to inspire the walker to get excited by the process of apple production.

But the Tree of Knowledge they offer does not offer golden apples nor the distinction between good and evil but instead seeks to fascinate followers through facts.

The Apfelweg is an excuse to exercise the body not the mind.

“The Eiffel Tower of Lake Constance” tag seems like a desperate marketing attempt to tempt tourists to the town when all that is needed is a walk upon the landing and along the shore to seduce the visitor to embrace the town’s tranquility.

Above: Altnau

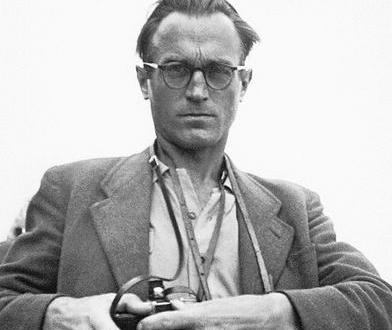

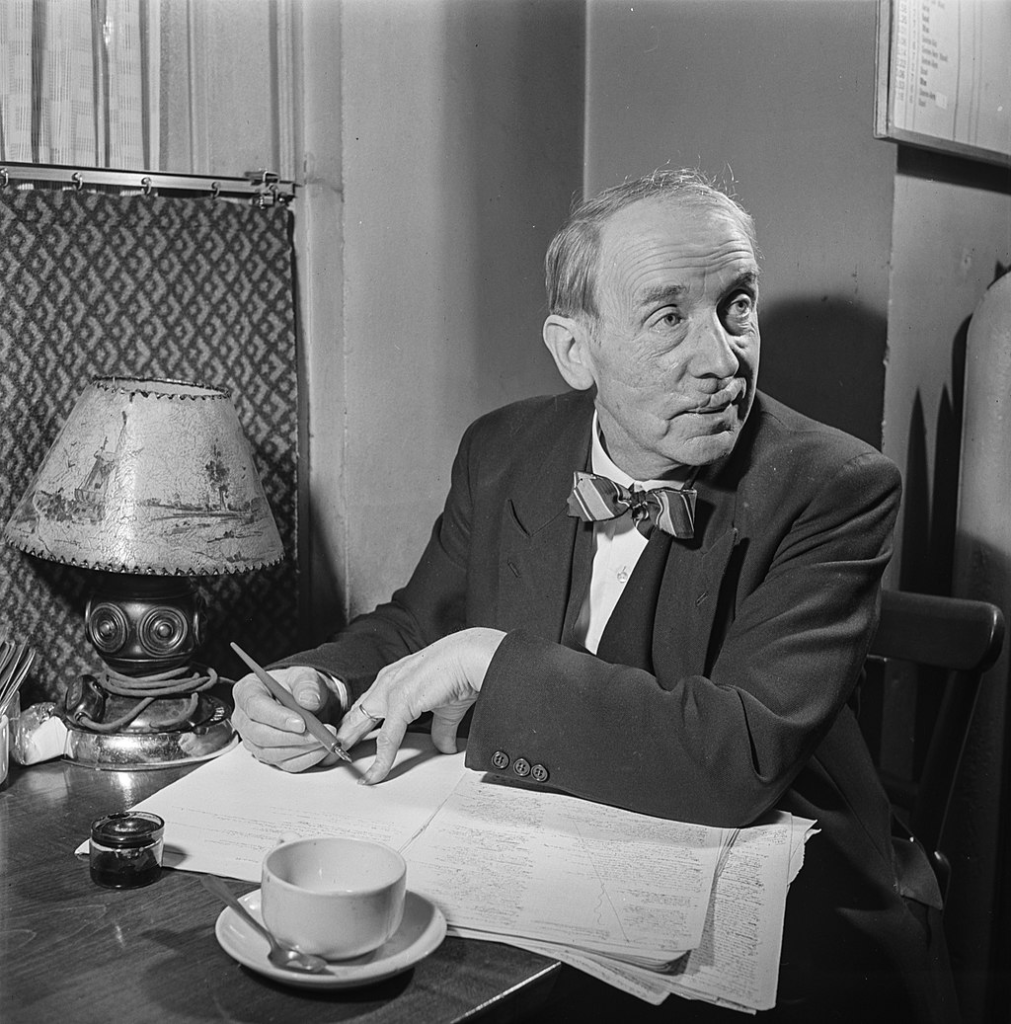

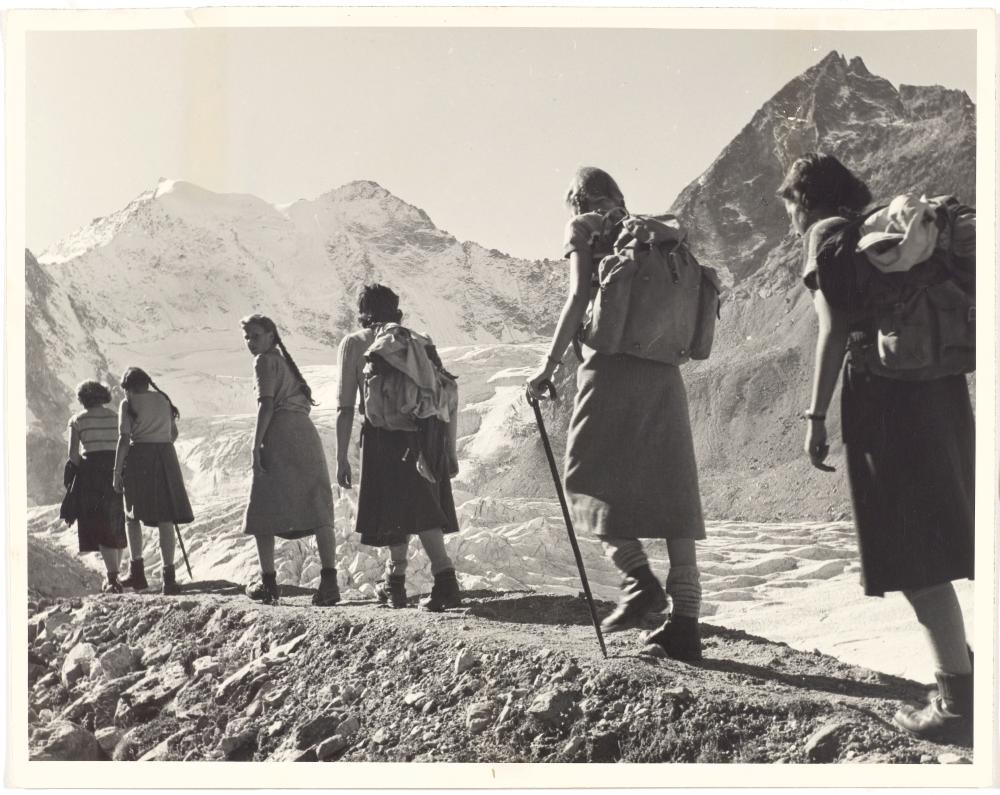

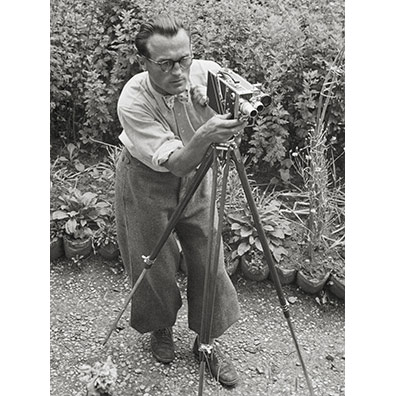

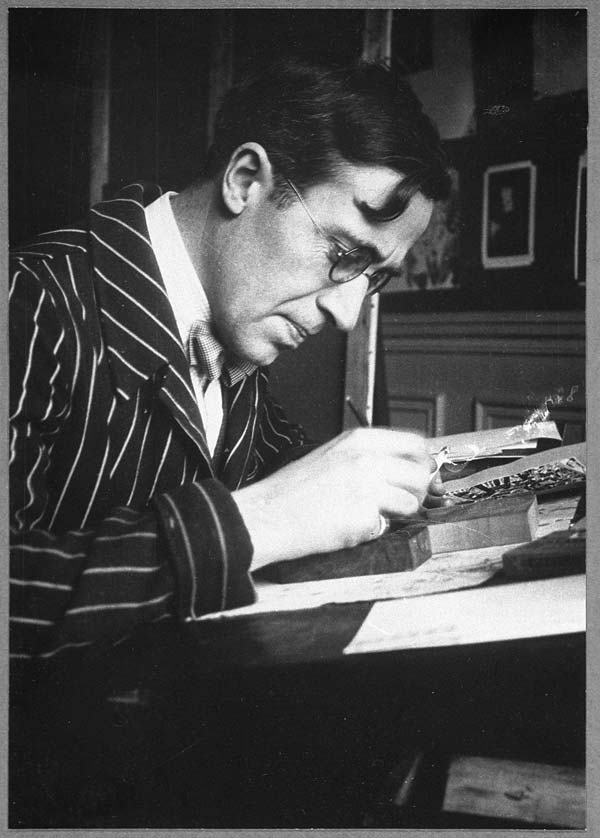

- Hans Baumgartner (1911 – 1996) was a Swiss photographer and teacher.

Above: Hans Baumgartner

Hans Baumgartner was born in Altnau.

He trained as a teacher at the Kreuzlingen Teacher Training College and at the University of Zürich.

Above: Pedagogical Matura School, Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau

From 1937 until his retirement, he worked as a teacher in Steckborn until 1962 and later in Frauenfeld.

Above: Steckborn, Canton Thurgau

Above: Frauenfeld, Canton Thurgau

Baumgartner’s first photographs were taken in 1929.

Above: Hans Baumgartner

In the early 1930s, he was discovered by the journalist Arnold Kübler.

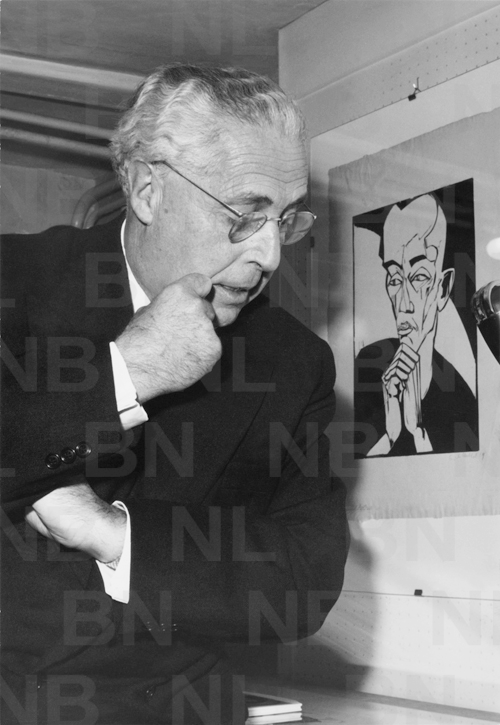

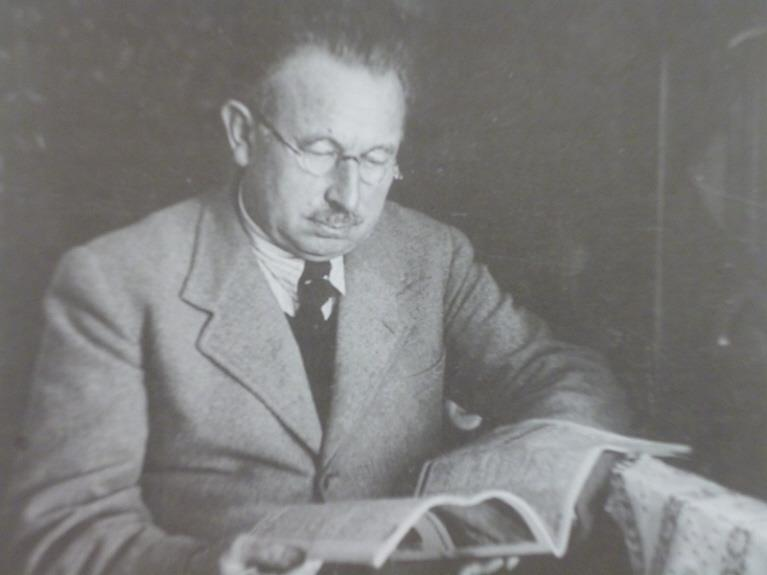

Above: Swiss writer Arnold Kübler (1890 – 1983)

His first photo report appeared in 1935.

Baumgartner subsequently published in magazines such as Camera, du, Der Schweizer Spiegel, Die Schweiz and Föhn.

The Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Thurgauer Zeitung also published his pictures.

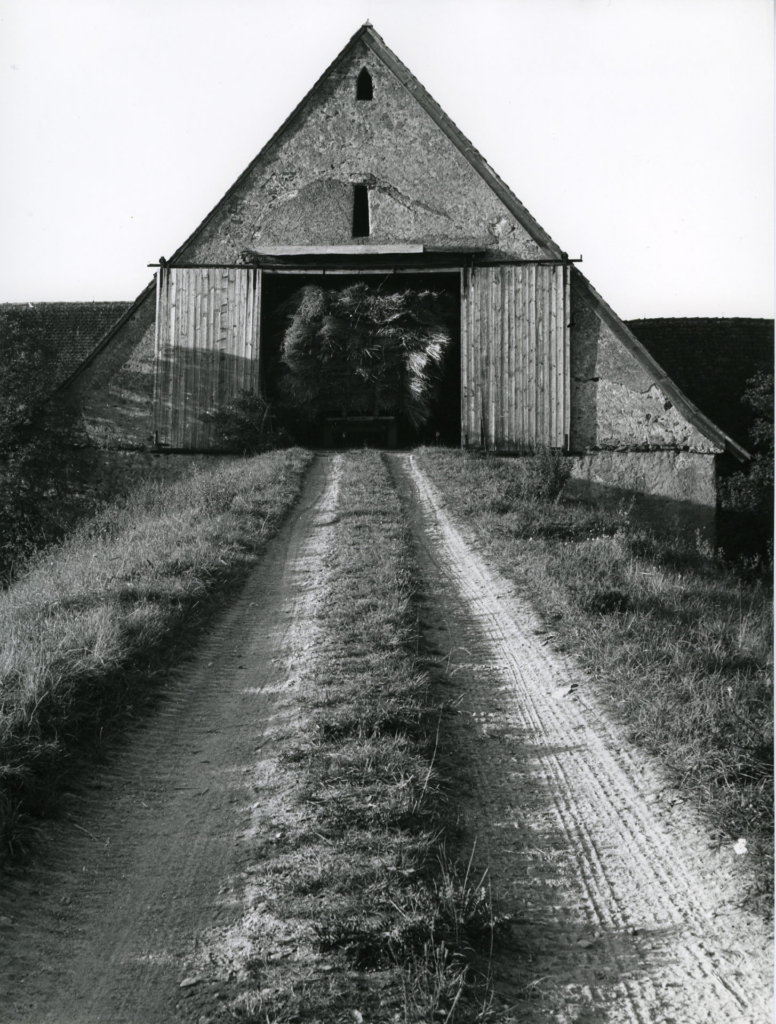

His photo books (from 1941) deal primarily with subjects from his home canton of Thurgau.

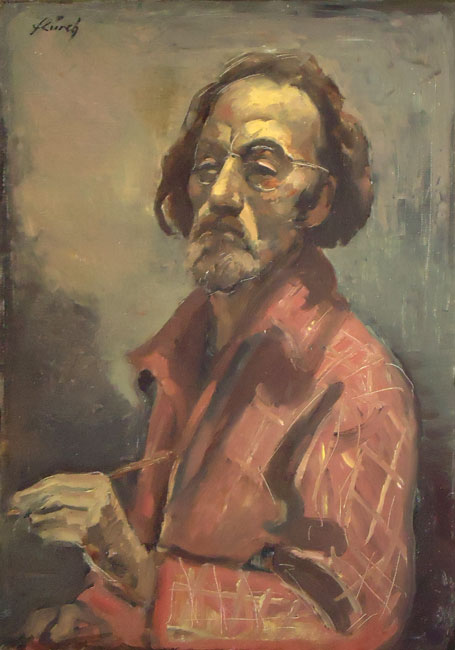

In 1937, he met the painter Adolf Dietrich, whom he subsequently portrayed several times.

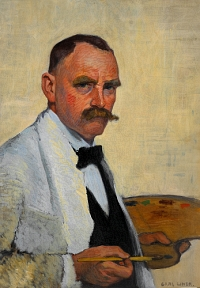

Above: Swiss painter Adolf Dietrich (1877 – 1957)

(I have spoken of Adolf Dietrich before and I may speak of him again in a future post.)

Above: Berlingen Pier in Winter, Adolf Dietrich

Baumgartner also took photographs on his trips to:

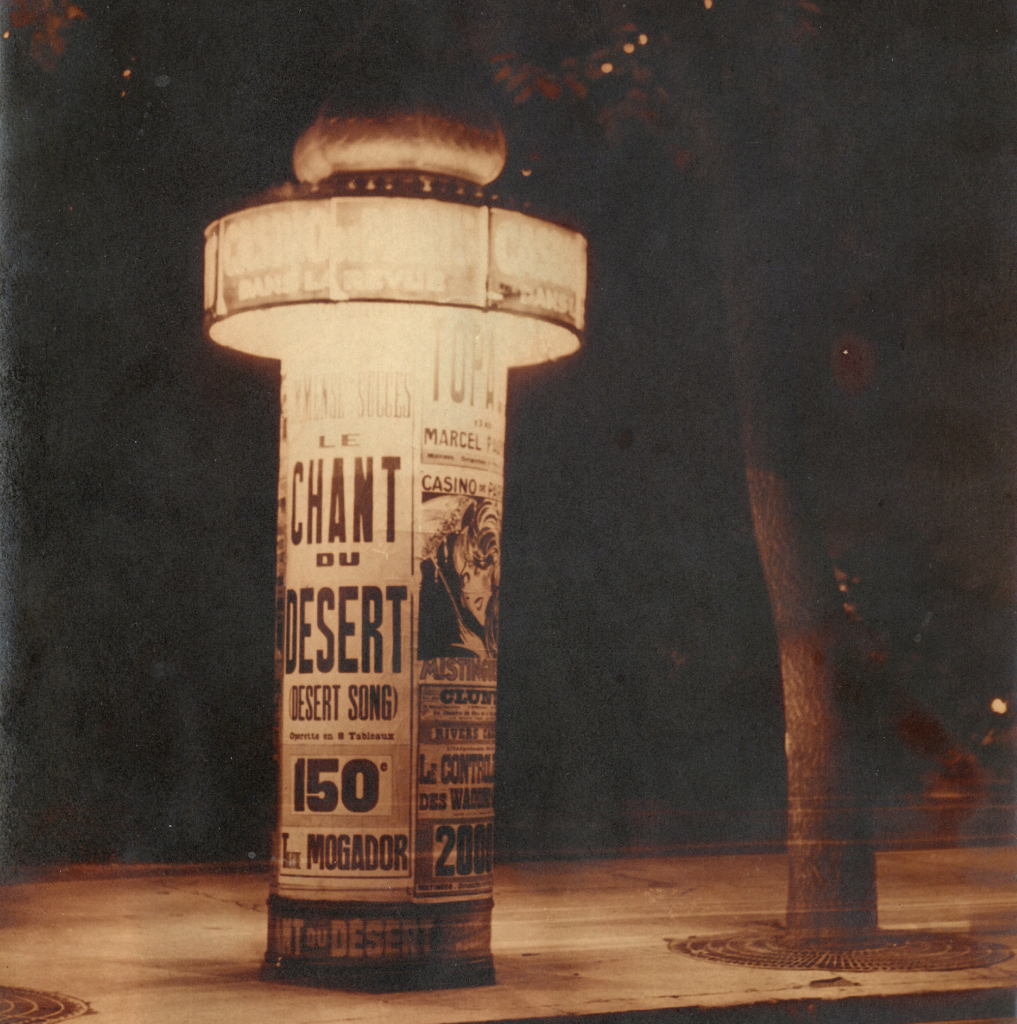

- Paris (1930, 1931 and 1991)

- Italy (1935)

- the Balkans (1935)

Above: Map of the Balkan Peninsula

- the South of France (1949 and 1953)

Above: Hans Baumgarten

- North Africa and the Sahara (1949)

Above: (in green) North Africa

- Croatia and Dalmatia (1957)

Above: Flag of Croatia

- Burgundy (1966)

Above: (in red) Burgundy

- Spain and Portugal, Sweden and Finland (1969)

Above: Flag of Spain

Above: Flag of Portugal

Above: Flag of Sweden

Above: Flag of Finland

- the US (1970)

Above: Flag of the United States of America

- Hungary (1981 and 1991)

Above: Flag of Hungary

- Belgium and Germany (1987 and 1991)

Above: Flag of Belgium

Above: Flag of Germany

On his world tour by ship in 1963 he traveled to:

- Bombay (Mumbai)

Above: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

- Colombo

Above: Colombo, Sri Lanka

- Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City)

Above: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Hong Kong

Above: Hong Kong, China

- Yokohama

Above: Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

- Mexico

Above: Flag of Mexico

Health spa stays took him to Davos in 1946 and 1954.

Above: Davos, Canton Graubünden, Switzerland

Hans Baumgartner died in Frauenfeld in 1996.

His estate of approximately 120,000 photographs is administered by the Swiss Foundation for Photography.

It sounds like Baumgartner’s profession was teaching, but his true vocation was photography.

We remember his photos, but who remembers his teaching?

Perhaps we remember his photos because they were a true expression of himself?

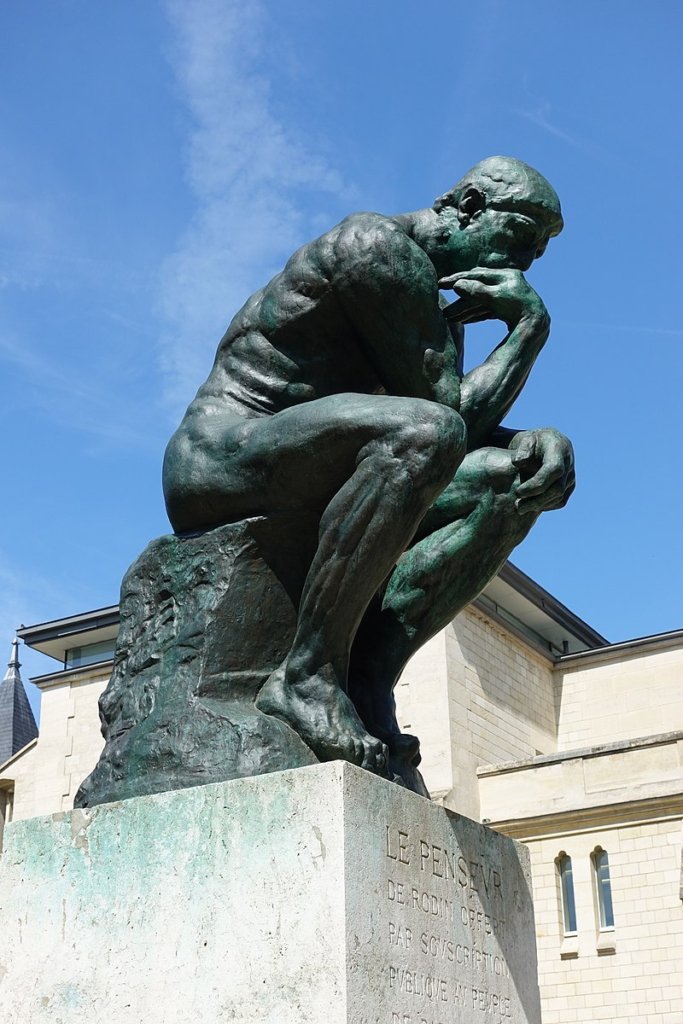

Above: The Thinker, Auguste Rodin (1904)

Altnau, a picturesque town on the shores of Lake Constance in Switzerland’s Thurgau Canton, has been a muse and retreat for several notable figures, particularly in the realms of literature and the arts.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, this serene locale attracted personalities such as Olga Diener, Hans Reinhart, Emanuel von Bodman and Golo Mann, each of whom found inspiration and solace in its tranquil environment.

Above: Altnau

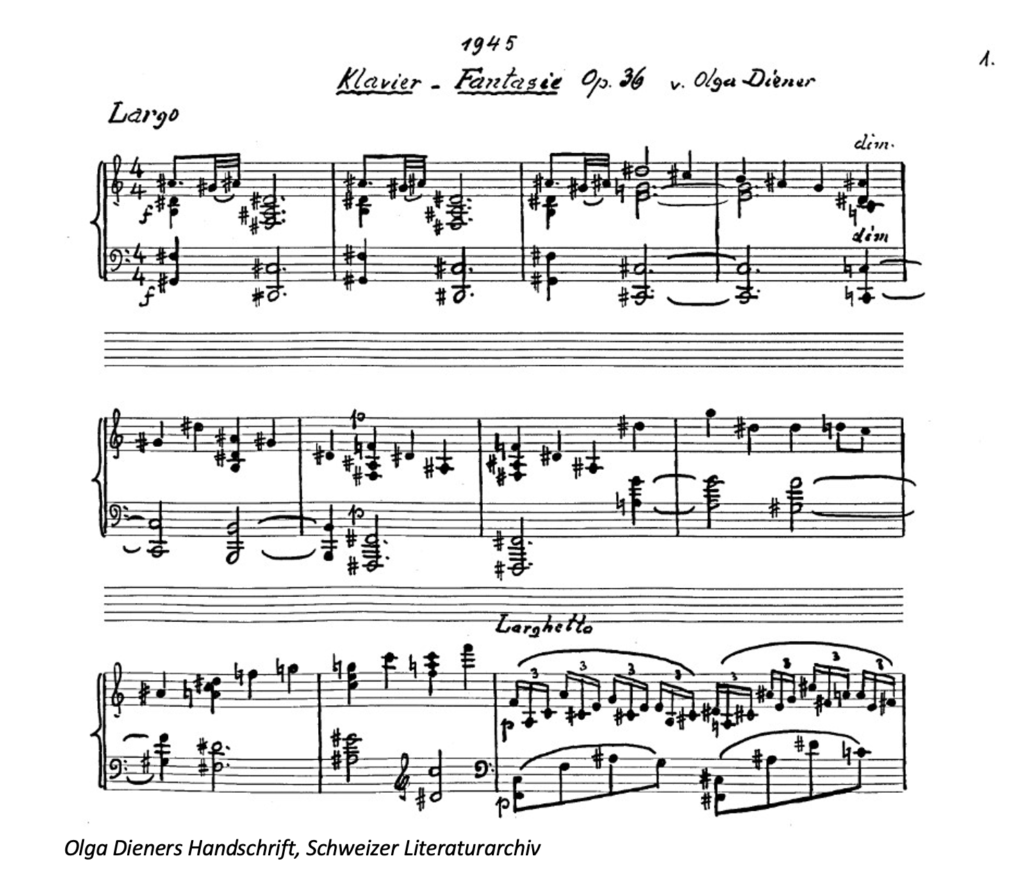

- Olga Diener (1890 – 1963):

A composer and poetess, Olga Diener made Altnau her home from 1933 to 1943.

Her residence, Belrepeire, became a gathering place for artists and intellectuals.

Above: Olga Diener

Notably, she hosted Hermann Hesse, who praised her poetic visions, and fellow poet Hans Reinhart.

Above: German writer Hermann Hesse (1877 – 1962)

Above: Hans Reinhart (1880 – 1963)

Her gatherings were marked by candlelight anniversary celebrations, attended by contemporaries like Emanuel von Bodman.

Above: German writer Emanuel von Bodman (1876 – 1946)

Olga Diener was a writer and composer.

She lived in St. Gallen and Altnau.

As a composer, she was never truly recognized, and as a poet of standing, she was almost forgotten.

Above: Olga Diener

Simone Keller writes about her:

“When Olga Diener passed away in St. Gallen in 1963, she left behind a compositional body of work with 76 opus numbers, primarily chamber music, numerous piano pieces, songs, sonatas for violin and cello or violin and piano, two string trios and string quartets, but also larger piano concertos and fairy-tale and mystery plays.“

I find myself asking the question:

Did the lack of recognition signify that her life was irrelevant?

Does recognition signify relevance?

I look out from the north balcony of “our” Landschlacht apartment and see a flock of seagulls and a pair of swans.

I look out from the south balcony and see a pair of sparrows.

I have no names for the individual birds nor can I converse with them in birdsong.

Does this mean that their lives have no relevance?

She lived in Altnau from 1933 to 1943.

She was an Eastern Swiss composer, born in St. Gallen in 1890, who had studied violin and composition in her hometown, later also in London, Basel and Paris.

Olga Diener did not only compose but also wrote poetry.

The Winterthur poet and patron Hans Reinhart called her a “Swiss dream poet”.

Even Hermann Hesse noticed the “beautiful sound” in her verses, but criticized that she was “locked in a glass house which always separated her and her poems from the world” and that she could not bring her “secret language of the common language” close enough.

According to an entry in the guest book of the rectory in Kesswil on Lake Constance, Olga Diener met with various well-known Swiss writers in 1925, who were regularly invited there by Kesswil Pastor Jakobus Weidenmann.

The value of being in a community of writers.

In 1924, she was admitted to the Swiss Musicians’ Association and had thus established herself to a certain extent as both a poet and a writer.

In 1929, her String Trio Opus 12 premiered in the Recital Hall of the Tonhalle St. Gallen.

This was one of only two public performances of her compositions that Olga Diener had ever attended.

Above: Tonhalle St. Gallen

The St. Galler Tagblatt reported in 1929 that Olga Diener’s piece was more of an “unfinished sketch“, while the Stadtanzeiger praised the “most charming string trio” as an “uninhibited play with tones“, but also seemed to be not taken entirely seriously.

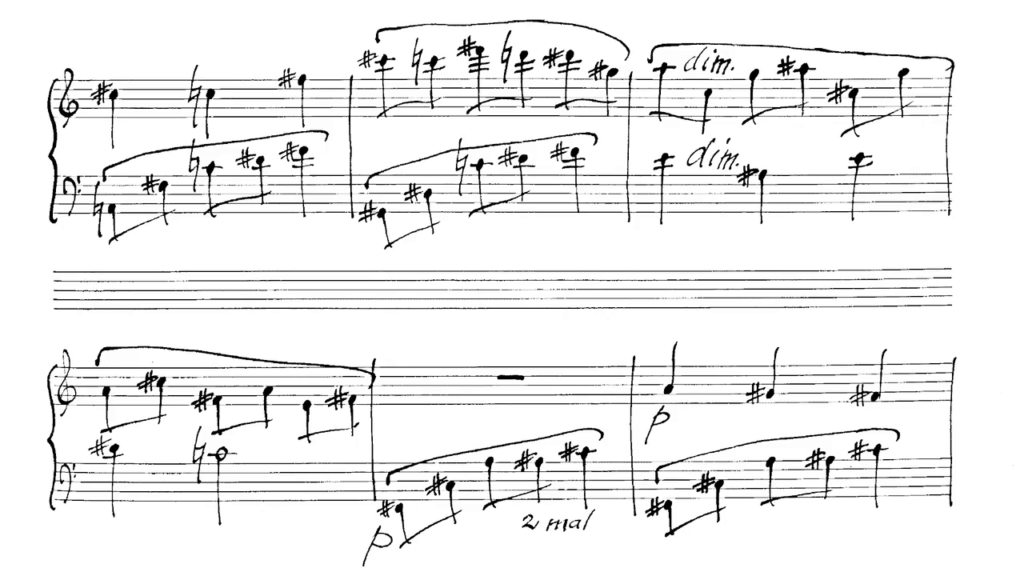

In 1943, the St. Gallen String Quartet performed Olga Diener’s String Quartet Op. 31 at a chamber music evening of the International Society for New Music at the Hotel Hecht in St. Gallen.

Above: Hotel Hecht, St. Gallen

The St. Gallen Tagblatt newspaper reported that the work “undoubtedly represents a significant advance in the composer’s oeuvre“.

Its transparent compositional technique and free use of time were praised.

But no further concerts featuring Olga Diener’s music followed.

She occasionally organized house concerts at her Altnau country house, Belrapeire, for example, premiering the String Quartet Opus No. 8.

The vast majority of her pieces, however, were never performed during her lifetime and remain so to this day.

Above: Olga Diener

Her work has been forgotten and lies more or less untouched in the Swiss Literary Archives.

Hardly anyone knows the poet Olga Diener today.

It almost seems as though her existence was as unreal as the tone of her poems.

Yet, she was once a very concrete figure by the Bodensee, where she had her permanent residence in Altnau during the 1930s.

She had a correspondence with Hermann Hesse.

Among the guests at her annual birthday celebrations, held by candlelight on 4 January, were the poets Hans Reinhart and Emmanuel von Bodman.

Otherwise, she avoided people, having had too many disappointments and losses to process.

Above: Olga Diener

Her house Belrapeire, which she had planned herself, stood somewhat apart from the village.

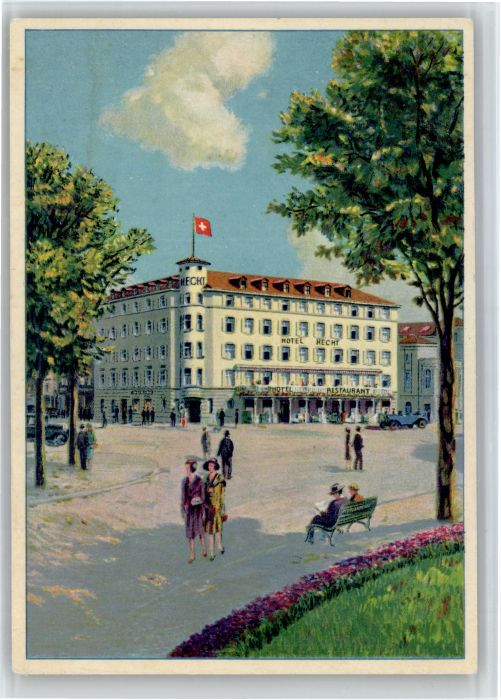

Belrapeire is the name of a town in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s epic poem Parzival.

The poetess was entirely captivated by the Grail myth.

In her seclusion, Olga Diener found the silence in which she listened to her poems, which bore such fairy-tale titles as “The Golden Castle” or “The White Stag.”

In this mystery play, a character named Blanscheflur sings the verses:

All gardens have awakened.

Dew fell from the stars, and

Venus Maria walked through them

with her radiant feet.

Now flowers breathe the

sky, and the earth fulfills

the dream, received from the spring night.

Like a blackbird singing?

Desire carries the wings

of swans, rustling over

the lake. Red rises the sun-ball

from the water. Light is

everything.

The images that Olga Diener saw during long walks along the shores of the Lake, as she would have said, condensed within her into dreamlike forms, whose verbal shape was often difficult to follow.

Even Hans Reinhart, who in the Bodenseebuch of 1935 made the only attempt for decades to critically appreciate Olga Diener, did not always understand her “private secret language“.

Olga Diener was essentially a musician.

For her, there was no creative distinction between writing and composing, between the lyrics of a poem and the music of a piece.

How musical her language was becomes immediately apparent when reading her quoted verses aloud.

Her poetry is filled with sound relationships far beyond the usual extent, something that Hesse had already observed:

“In your newer verses, there is often such a beautiful sound.“

However, Olga Diener wrote music notes as others wrote words.

In the guestbook of Julie and Jakobus Weidenmann, she immortalized herself with a line of musical notation instead of verses.

She was often a guest at the Weidenmanns’ home.

Julie Weidenmann shared Olga Diener’s nature-mystical worldview, though hers was tinged with Christianity, while Olga Diener leaned towards esotericism.

Julie Weidenmann’s first poetry collection was titled Tree Songs (Baumlieder).

In Altnau, Olga Diener wrote a cycle called Rose Songs (Rosenlieder).

The 7th poem in this cycle contains Olga’s lyrical confession:

“Let me tend my roses faithfully

in the innermost garden:

To fertilize, prune, and bind,

My hands torn by thorns.

The blooming light, the watchful moonlight

Enter the flower’s chalices.

The winds drift gently above,

And rain murmurs through many a night.

Like them, I am bound to the earth,

And one day, I too will disappear.“

- Hans Reinhart (1880 – 1963):

Originating from a Winterthur trading family, Hans Reinhart led an independent life as a poet.

He was deeply influenced by the works of Hans Christian Andersen, transforming the fairy tales into stage plays.

Above: Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen (1805 – 1875)

Reinhart’s visits to Olga Diener’s Altnau home were significant, contributing to the rich cultural tapestry of the area.

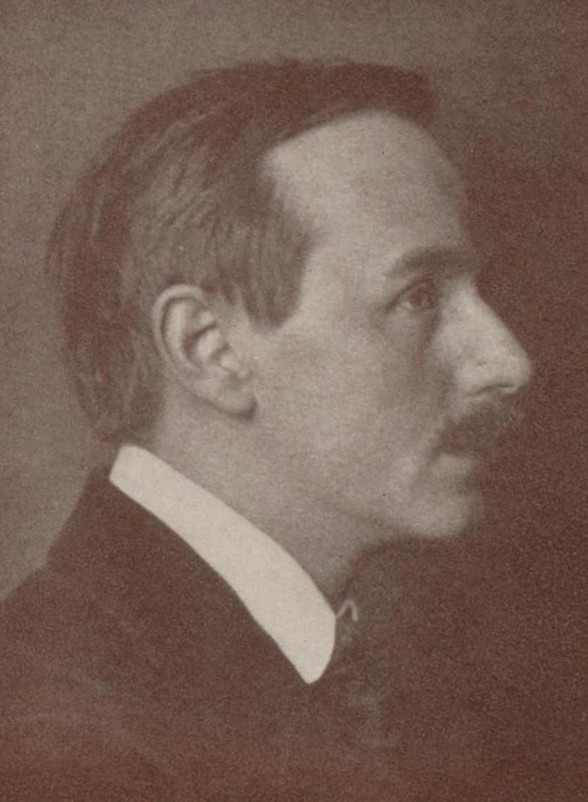

Above: Hans Reinhart

Hans Reinhart (1880 – 1963) was a Swiss poet, translator and

patron of the arts.

In 1957, he founded a foundation that has awarded the

Hans Reinhart Ring annually since then.

(The Hans Reinhart Ring is considered the highest award in Swiss theatre life and was awarded by the Swiss Society for Theatre Culture (SGTK) from 1957 to 2013 .

The ring is named after the Winterthur patron Hans Reinhart, who donated it in 1957.

After his endowment was exhausted, it was donated to the SGTK.

A specially appointed jury of five members appointed by the SGTK board awarded this distinction.

No ring was awarded in 1992.

In an agreement with the Federal Office of Culture, the SGTK transformed the Hans Reinhart Ring into the newly created Swiss Grand Prix Theater / Hans Reinhart Ring in 2014, endowed with CHF 100,000.

It continues to participate in the awards ceremony by presenting the winner with a specially crafted ring and documenting their work in its Mimos Swiss Theater Yearbook series.

Since then, the awards have been made on the recommendation of the Federal Jury for Theater, which also participates in the Swiss Theater Prize.)

Above: Swiss actress Lilo Baur

Hans Reinhart came from the Reinhart family of Winterthur merchants.

His background as the son of the Winterthur merchant and patron Theodor Reinhart gave him the opportunity to lead a financially independent life as a poet.

Above: Winterthur, Canton Zürich, Switzerland

During a spa stay in Karlovy Vary in the late summer of 1889, he read for the first time the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen, which impressed him deeply and which he later adapted into stage plays.

Above: Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic

In 1899, he graduated from secondary school in Winterthur.

As a student, he belonged to the fraternity Vitodurania, where he was nicknamed “Müggli“.

Above: Coat of arms of Vitodurania

He then studied philosophy, psychology, German studies, art, theatre and music history in Heidelberg, Berlin, Zürich, Paris, Leipzig and Munich.

Above: Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Above: Berlin, Germany

Above: Zürich, Switzerland

Above: Paris, France

Above: Leipzig, Saxony, Germany

Above: Munich, Bavaria, Germany

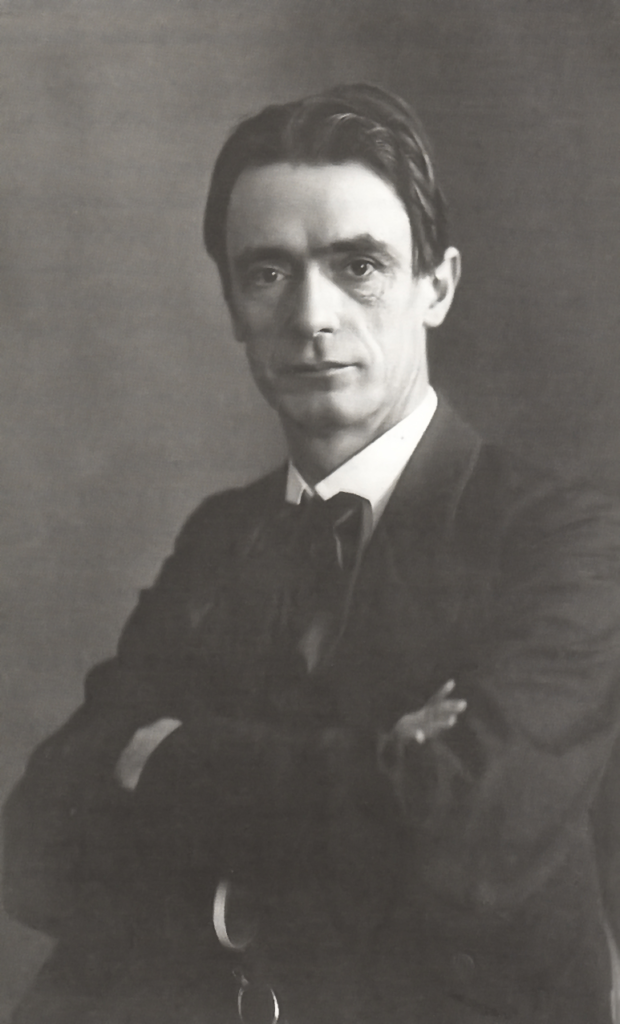

After his studies, he first met Rudolf Steiner in 1905, whom he recognized as a spiritual teacher.

Above: Austrian writer Rudolf Steiner (1861 – 1925)

He later helped build the first Goetheanum and became friends with other anthroposophists.

In 1917, Reinhart founded the Winterthur Literary Association.

Above: Goetheanum, Dornach, Canton Solothurn, Switzerland

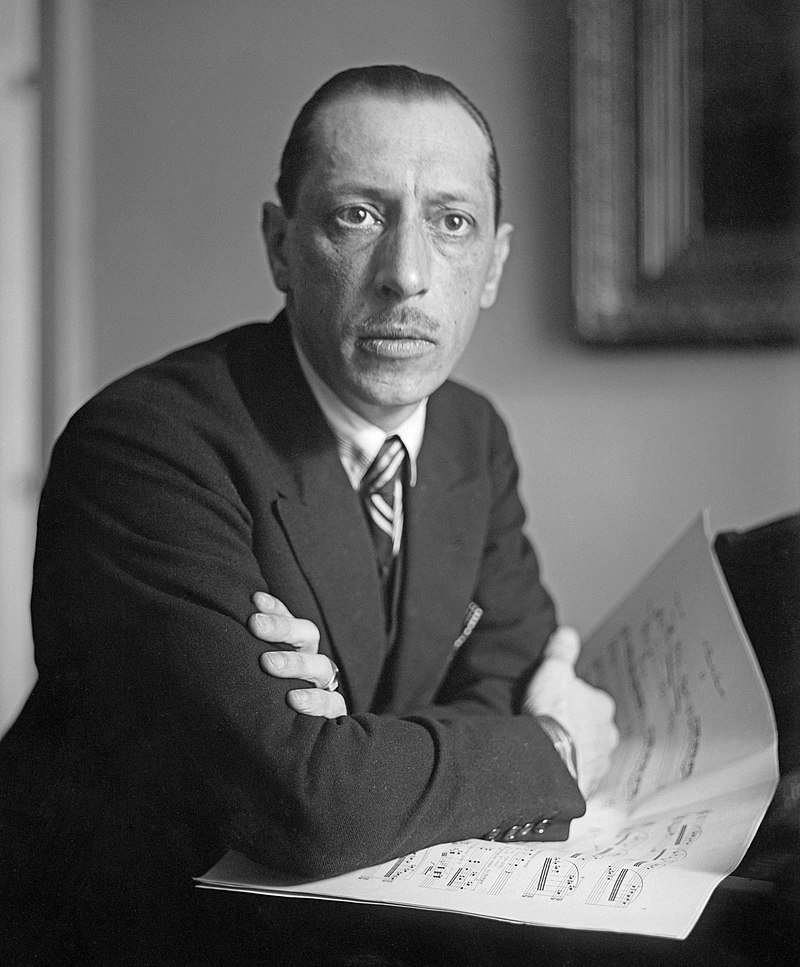

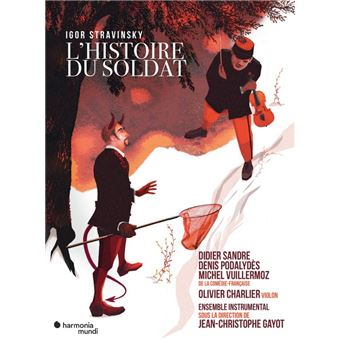

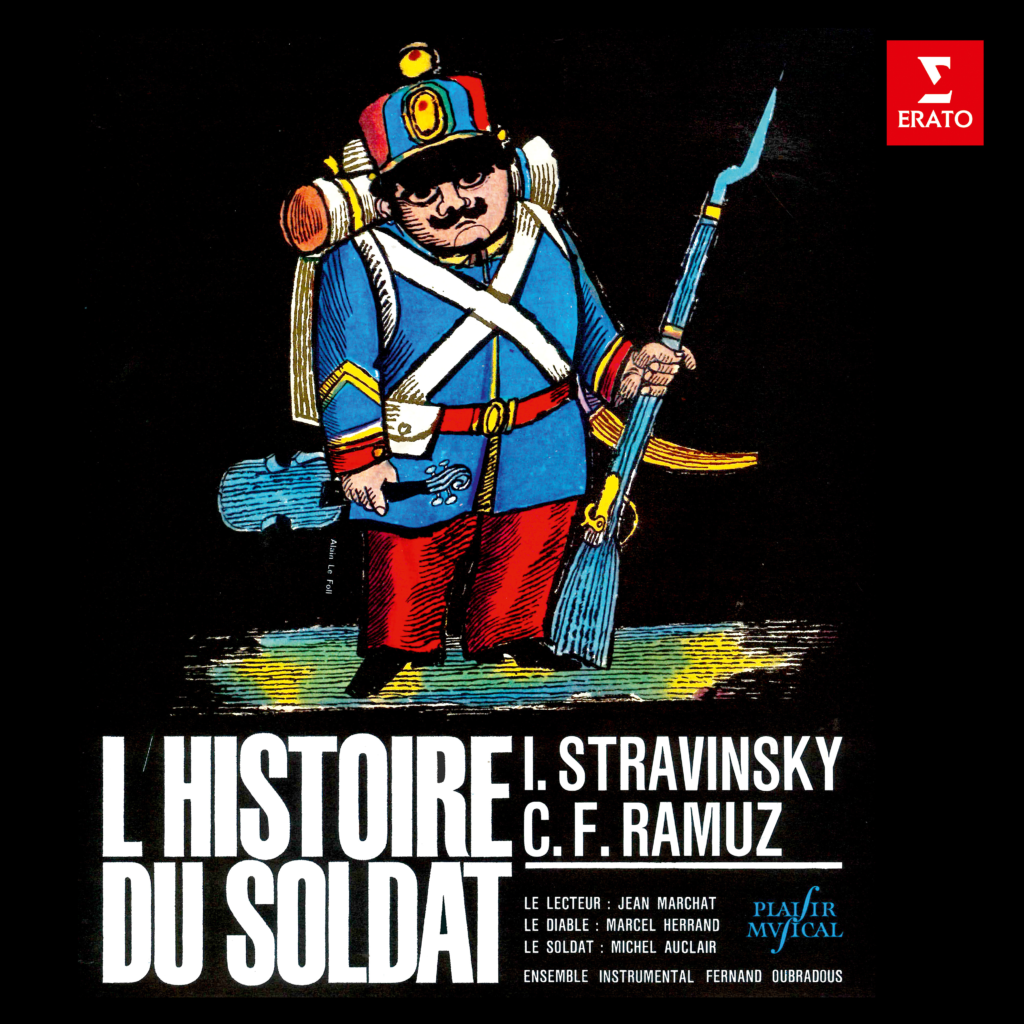

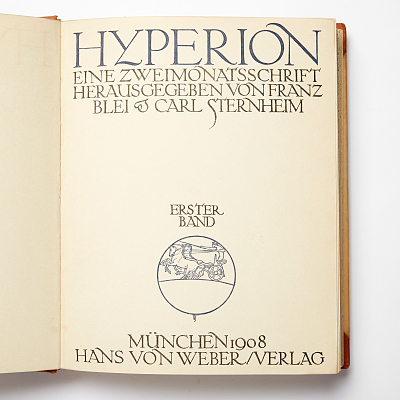

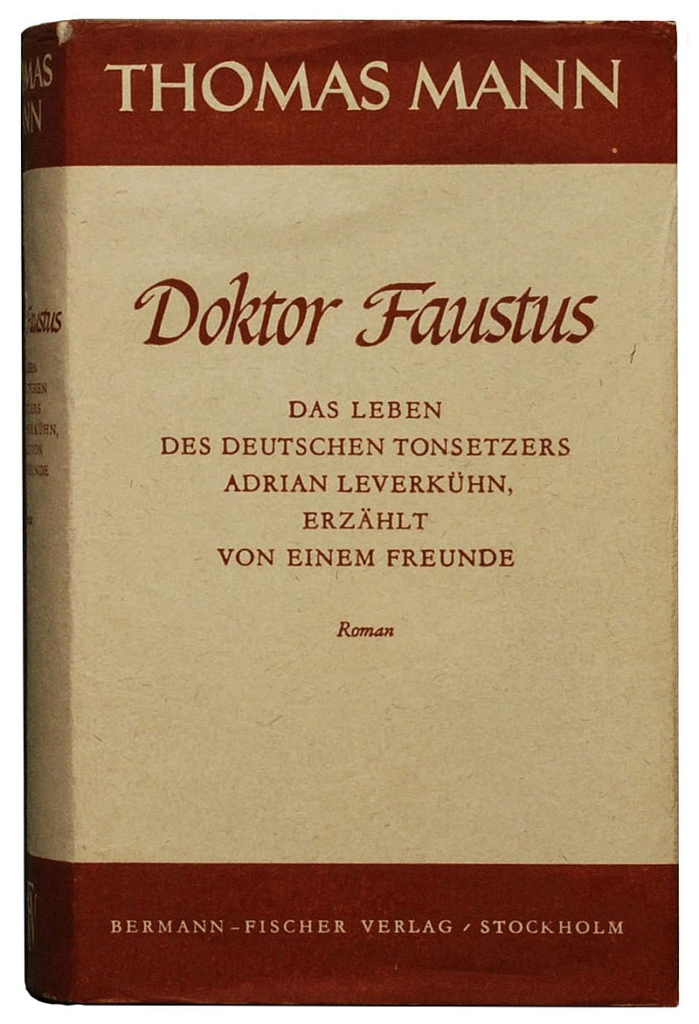

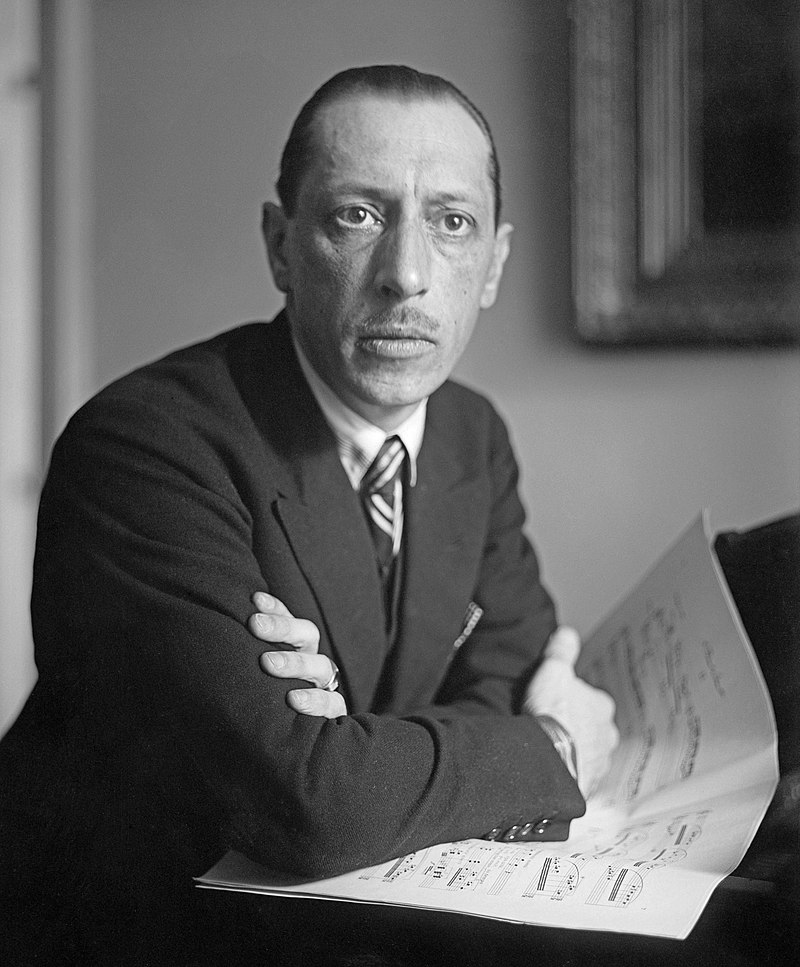

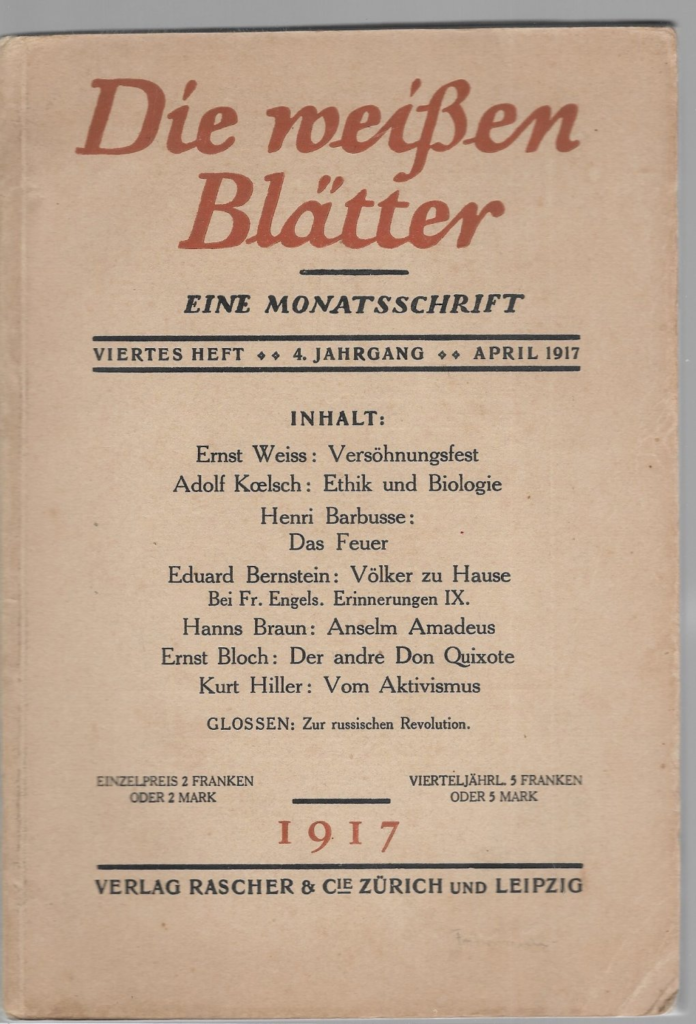

Histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Story) is a musical theatre work (original title: “Lue, jouée, dansée et en deux parties“) (‘Read, played, danced and in two parts‘) for a small ensemble, which the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky created in collaboration with the

Swiss Canton Vaud poet Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz.

Above: Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (1878 – 1947)

The work was written for a traveling theater group consisting of a reader, two actors, a dancer, and seven musicians.

Above: Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

For the text, Ramuz used two stories from a collection of Russian fairy tales by Alexander Afanasyev.

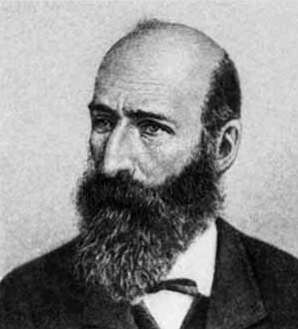

Above: Alexander Afanasyev (1826 – 1871)

The text is partly recited in poem form by the reader, rhythmically accompanied by music, and partly spoken as a drama by the reader and the actors (soldier, devil) (with the reader mostly still speaking in rhyme, and the devil only in dialogue with the soldier).

The first German adaptation was written by Hans Reinhart, the brother of the Winterthur music patron Werner Reinhart, who made the premiere of the work possible (on 28 September, or according to Stravinsky’s Recollections on 29 September 1918 at the Opéra de Lausanne under the direction of Ernest Ansermet) and to whom this work is dedicated.

Above: Opéra de Lausanne, Canton Vaud, Switzerland

In 1919, Stravinsky arranged five movements of Histoire du soldat for violin, clarinet and piano, which were published under the title Suite from “The Soldier’s Tale” .

A soldier trades his violin with the devil for a book that promises great riches.

He must teach the devil to play the violin within three days.

In reality, however, three years pass, and the soldier is considered a deserter.

Back home, he is recognized by neither his mother nor the villagers, and his bride is married.

With the help of the book, which predicts the rise and fall of the stock market, he becomes a rich merchant, but the money does not make him happy.

Instead, he wishes to cure the sick princess with his violin playing.

After losing a card game with the drunken devil, he gets his violin back, but in return he is no longer allowed to set foot in his homeland.

Once he has his violin back, he cures the princess with his playing, and they become a couple.

When he returns home, the devil is already waiting for him.

Whether the soldier ultimately follows the devil into his kingdom remains open.

The moral of this simple fairy tale is:

“One should desire what one has, not what was before.

One cannot be both who one is and who one was.

One cannot have everything.

What was will not return.”

Reinhart considered his own poetic work complete after 1920.

Arthur Honegger’s oratorio King David premiered in Winterthur in 1923 in the presence of the composer — with the German text by Hans Reinhart, which, despite the constraints of rhythm and rhyme, remained very close to the French original.

Above: Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892 – 1955)

From 1926 to 1929, Reinhart published the quarterly journal Individualität (Individuality).

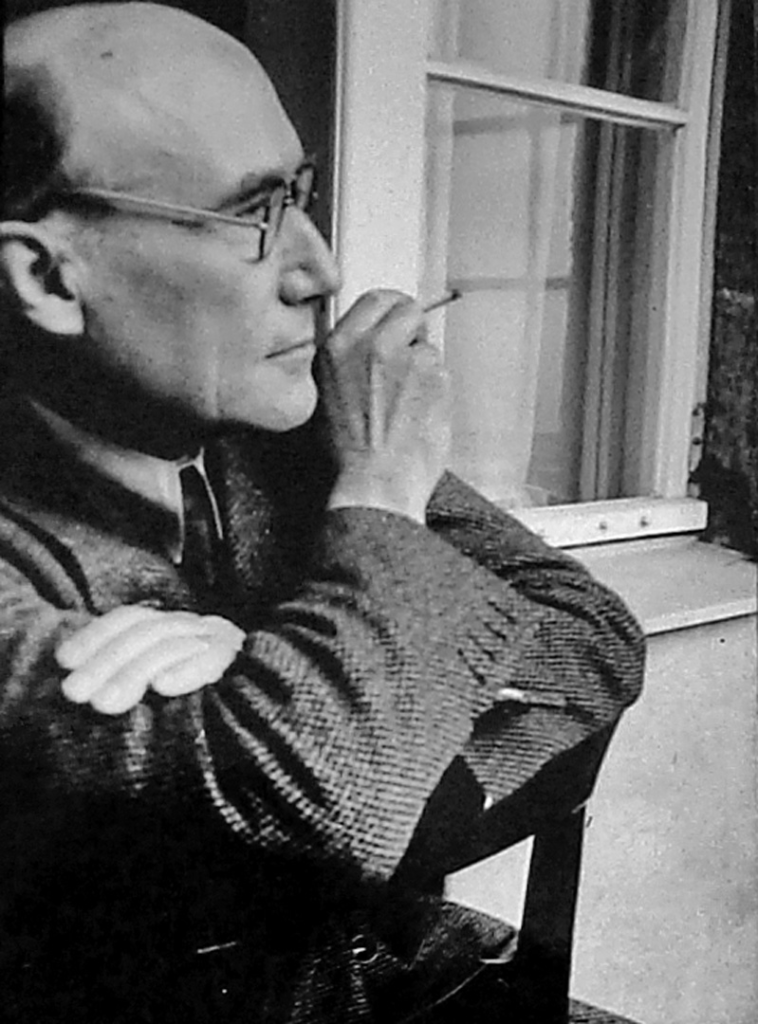

In 1941, he brought his friend, the poet Alfred Mombert and his sister Ella Gutmann from the concentration camp Gurs in the French Pyrenees.

Above: German poet Alfred Mombert (1872 – 1942)

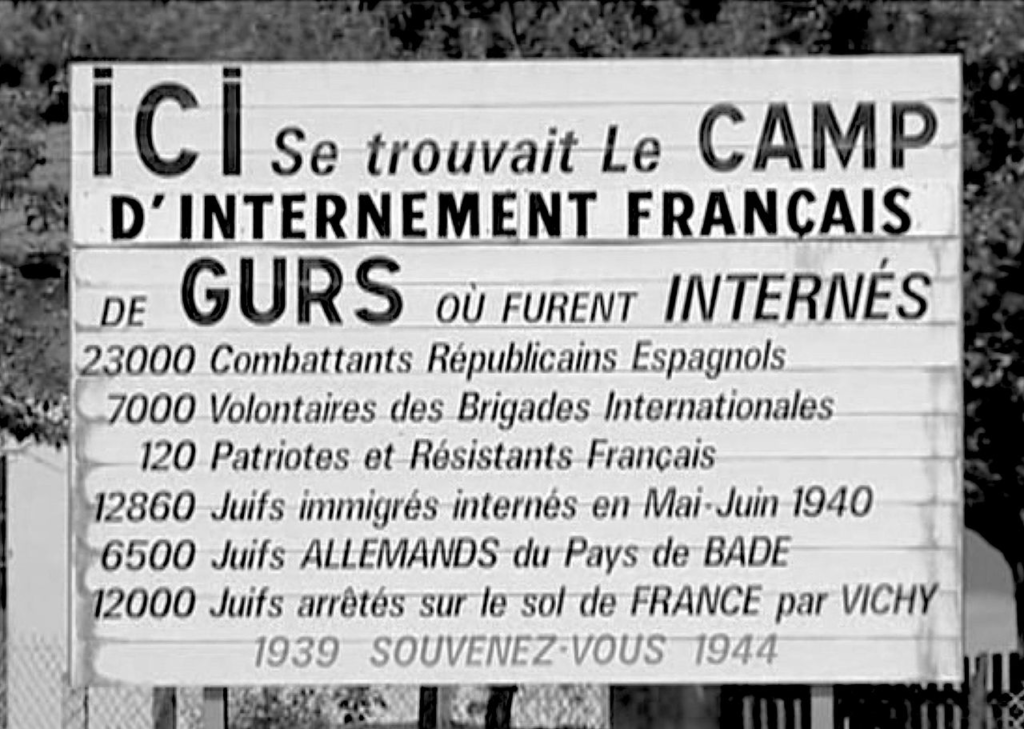

Gurs was run on behalf of the German Nazi regime by the Vichy regime, outside the territories occupied after the Armistice of Compiègne, to which, in 1940, approximately 6,500 Germans of Jewish descent, from Baden and the Saarpfalz, had been deported as part of the Wagner-Bürckel Action.

Above: Gurs Concentration Camp, Gurs, Pyrénées-Atlantique, France

In Winterthur, the poet died on 8 April 1942 and was buried in the park of the Villa Kareol, after he had managed to complete the second part of his poem Sfaira the Old and had received it in a private print arranged by Reinhart as a gift for his 70th birthday.

Above: Villa Reinhart, Heiligberg, Winterthur

.

- Emanuel von Bodman (1874 – 1946):

Emanuel von Bodman, who had strong ties to Switzerland, chose Gottlieben as his adopted home.

His residence was frequented by many artists, including Olga Diener.

He visited Olga in Altnau from time to time.

Above: Bodmanhaus, Gottlieben, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Bodman was esteemed as a poet, storyteller and playwright, contributing to the cultural milieu of the region.

Johann Franz Immanuel August Heinrich Freiherr von und zu Bodman, called Emanuel von Bodman (1874 – 1946) was a German writer and poet.

Emanuel von Bodman lived as a child in Kreuzlingen and attended high school in Konstanz.

After studying in Zürich, Munich and Berlin, he chose Gottlieben, Switzerland, as his adopted home.

He initially lived opposite Gottlieben Castle in the municipality of Tägerwilen.

After marrying Clara Herzog, he lived from 1920 until his death in a former trading house on the Gottlieben village square.

His house was a meeting place for many artists.

Emanuel von Bodman wrote several plays, short stories, and hundreds of poems.

His complete works were published after his death in a ten-volume complete edition.

He was seen as a poet, storyteller and playwright in the tradition of Neo-Romanticism and Neo-Classicism.

In 1940, he was awarded the Literature Prize of the City of Zürich.

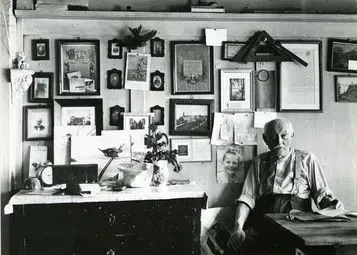

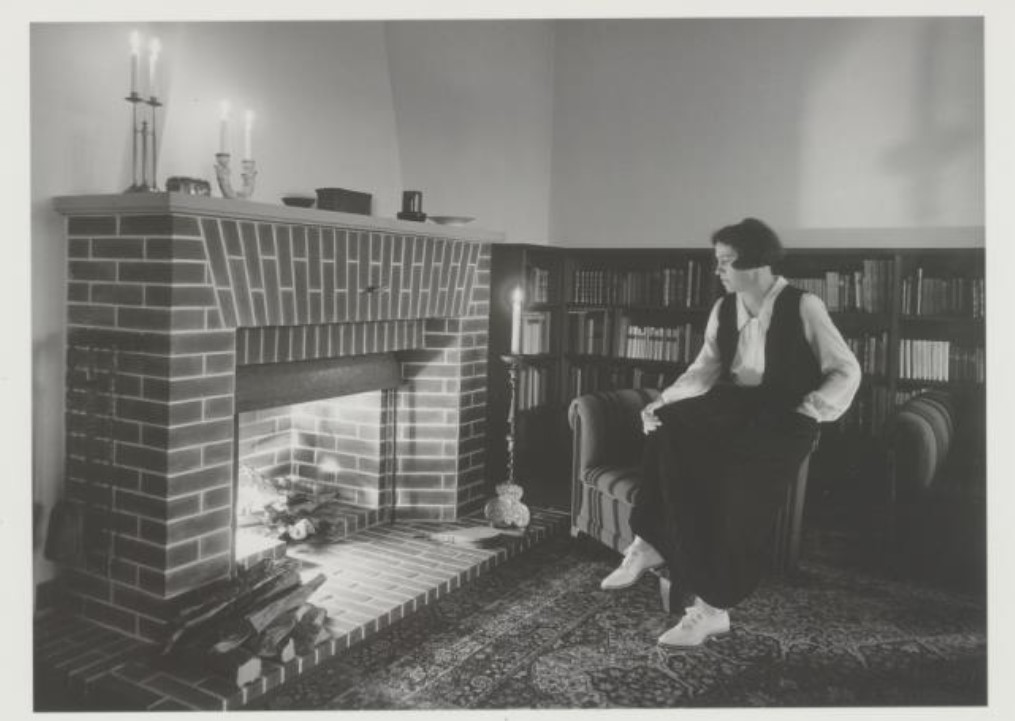

Above: The poet’s room, Bodmanhaus, Gottlieben

The Gottlieben house is the headquarters of the Thurgau Bodman Foundation.

In 1999, it became the first literary house on the Lake as a museum.

Above: Bodman’s writing desk, Bodmanhaus, Gottlieben

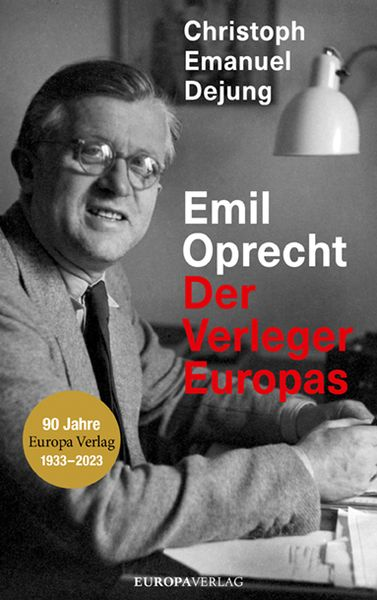

- Emmi and Emil Oprecht:

While specific details about Emmi and Emil Oprecht’s contributions to Altnau’s cultural scene are limited, their names are often associated with the town’s artistic community.

Their involvement, though not extensively documented, adds to the rich tapestry of personalities who have found inspiration in Altnau’s serene environment.

Emmi and Emil Oprecht were part of the circle of friends of Julie and Jakobus Weidenmann in Kesswil.

Their house in Zürich was a meeting place for all opponents of the Hitler regime during the war.

Their Europa Verlag was committed to the same democratic and social ideals as the guests of the Weidenmanns in the 1920s.

Although Emil Oprecht was a book lover, he wrote little himself.

As a man of action, he found ways to make seemingly hopeless paths viable even in the most difficult situations.

His equally active wife, Emmie, always supported him.

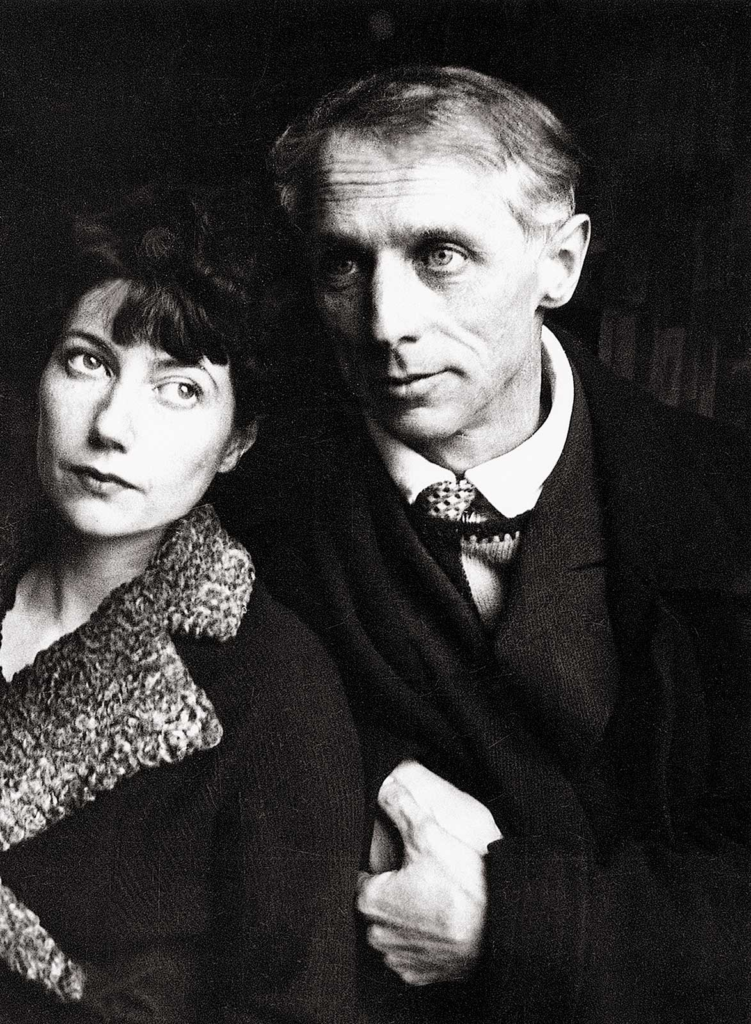

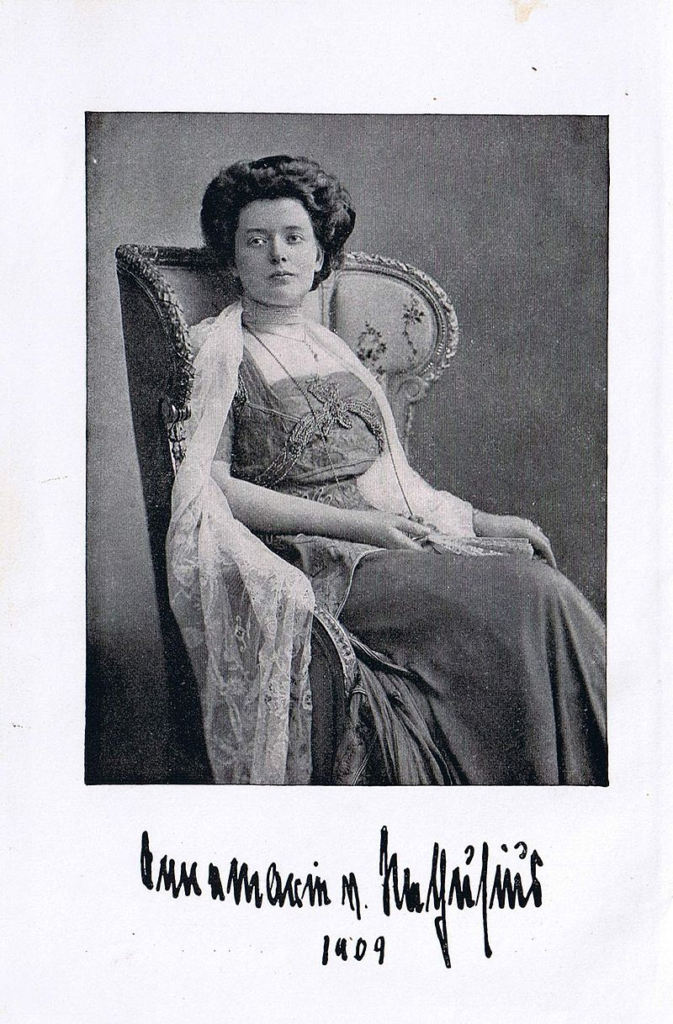

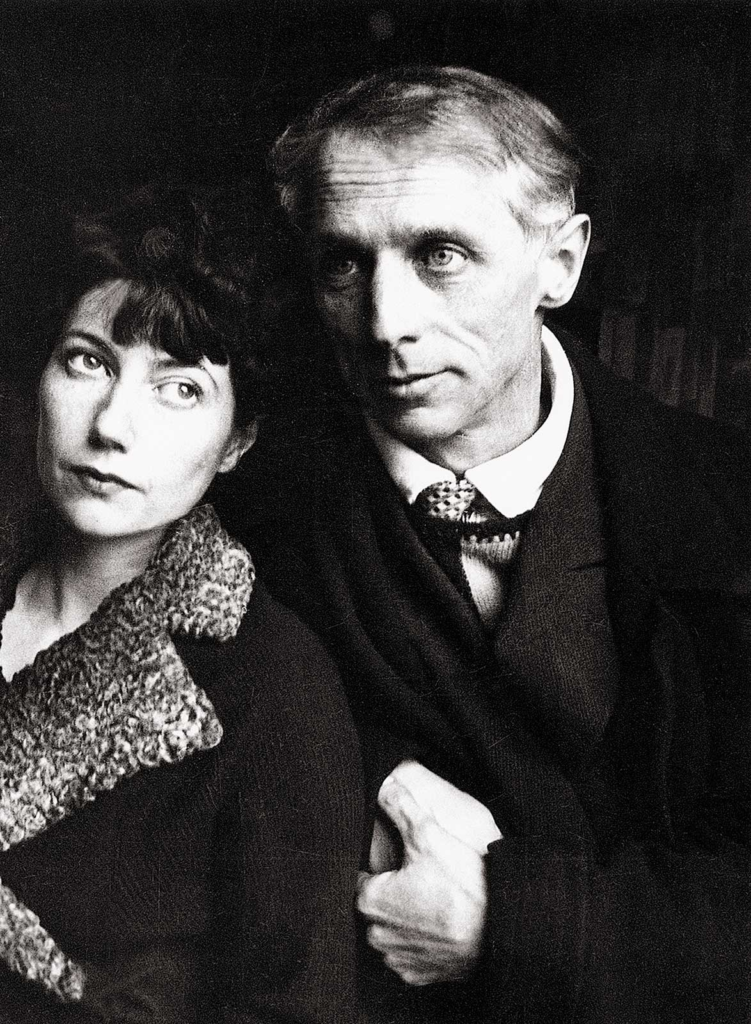

Above: Emmi (1899 – 1990) and Emil Oprecht (1895 – 1952)

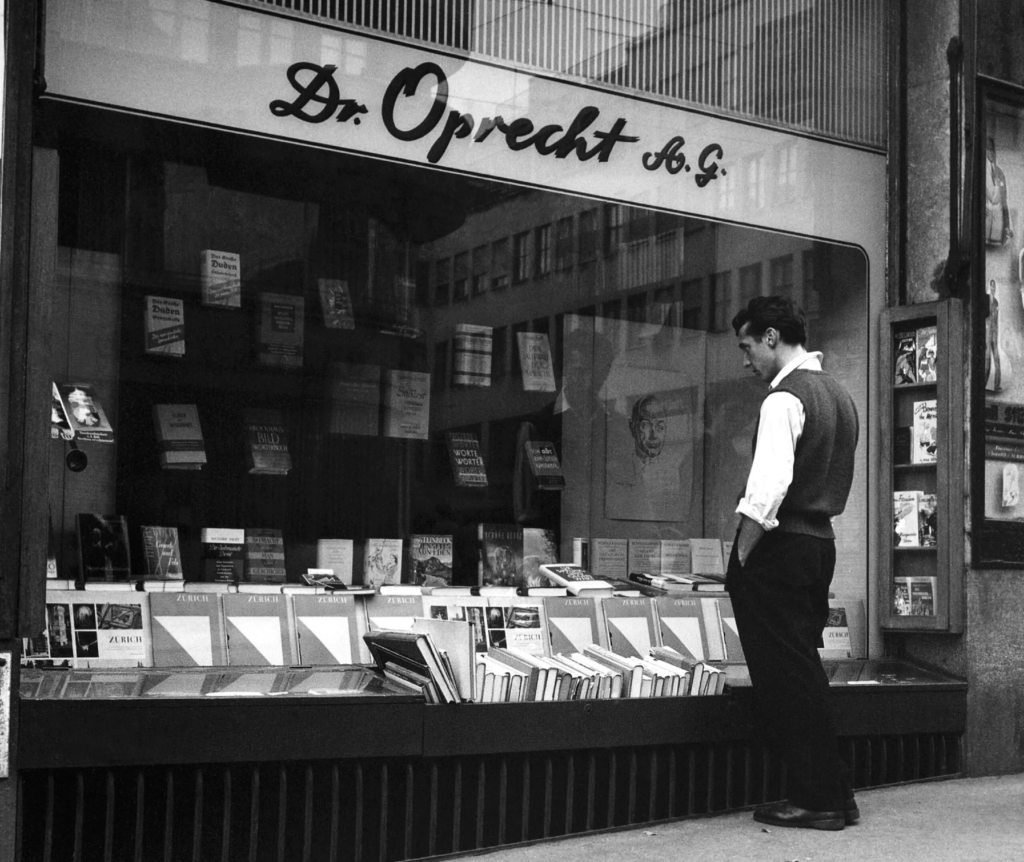

The legendary Zurich bookstore Dr. Oprecht at Rämistrasse 5 closed its doors forever on 31 January 2003.

Zürich not only lost a store, but also an era.

A sense of national mourning reigned in Zurich’s intellectual milieu, the NZZ reported.

In 2019, the Hauser & Wirth gallery and its art publishing house moved into the renovated historic premises.

Fewer and fewer people remember the former bookstore and its eventful history.

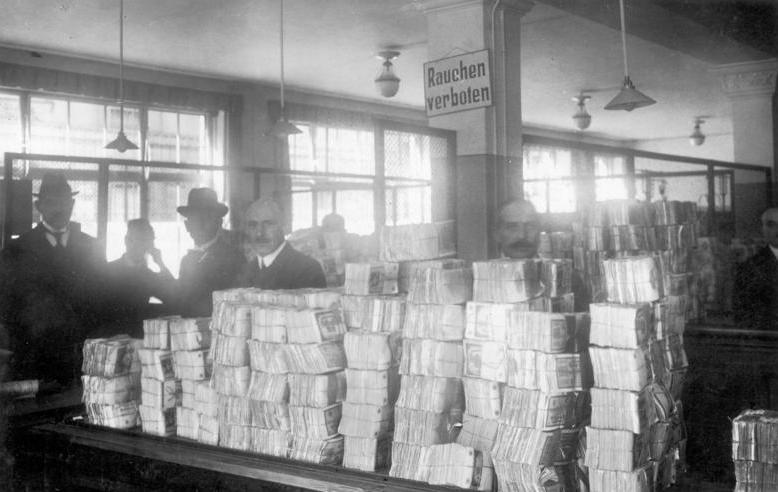

Between 1933 and 1945, works by approximately one hundred exiled authors, including Ignazio Silone, Else Lasker-Schüler, Max Horkheimer, Heinrich Mann, and Golo Mann, were published, mostly without financial success, often in the face of domestic censorship and the resistance of anti-Semitic rioters.

Europa Verlag published factual accounts of concentration camps early on, such as Wolfgang Langhoff’s Moorsoldaten (Moor Soldiers) about the Börgermoor concentration camp in Emsland in 1935 and Walter Hornung’s Dachau in 1936.

The Nazi regime expelled Oprecht’s publishing house from the German Booksellers’ Association, but his books reached Germany through covert channels.

After the Berlin Book Burning, the bookstore displayed a pyre containing the books that had been burned in Berlin in its window.

Above: Nazi book burnings, May 1933

The Nazi book burnings were a campaign conducted by the German Student Union (Deutsche Studentenschaft, DSt) to ceremonially burn books in Nazi Germany and Austria in the 1930s.

The books targeted for burning were those viewed as being subversive or as representing ideologies opposed to Nazism.

These included books written by Jewish, half-Jewish, communist, socialist, anarchist, liberal, pacifist, and sexologist authors among others.

A total of over 25,000 volumes of “un-German” books were burned, thereby ushering in an era of uncompromising state censorship.

In many other university towns, nationalist students marched in torch lit parades against the “un-German” spirit.

The scripted rituals of this night called for high Nazi officials, professors, rectors, and student leaders to address the participants and spectators.

At the meeting places, students threw the pillaged, banned books into the bonfires with a great joyous ceremony that included live music, singing, “fire oaths” and incantations.

In Berlin, some 40,000 people heard Joseph Goebbels deliver an address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!”

Goebbels enjoined the crowd.

“Yes to decency and morality in family and state!“

“The era of extreme Jewish intellectualism is now at an end.

The breakthrough of the German revolution has again cleared the way on the German path.

The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character.

It is to this end that we want to educate you.

As a young person, to already have the courage to face the pitiless glare, to overcome the fear of death, and to regain respect for death – this is the task of this young generation.

And thus you do well in this midnight hour to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past.

This is a strong, great and symbolic deed – a deed which should document the following for the world to know.

Here the intellectual foundation of the November Republic is sinking to the ground, but from this wreckage the phoenix of a new spirit will triumphantly rise.“

Joseph Goebbels, Speech to the students in Berlin

Above: German politician Joseph Goebbels (1897 – 1945)

“Where they burn books, they will burn people too in the end.”

Heinrich Heine

Above: German poet Heinrich Heine (1797 – 1856)

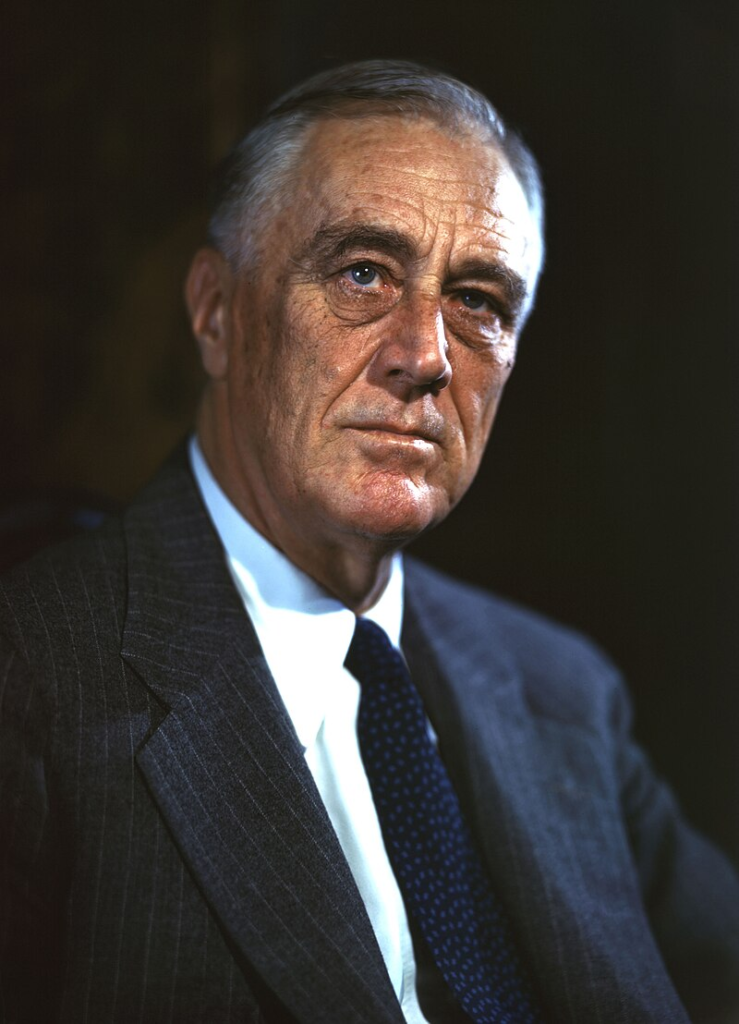

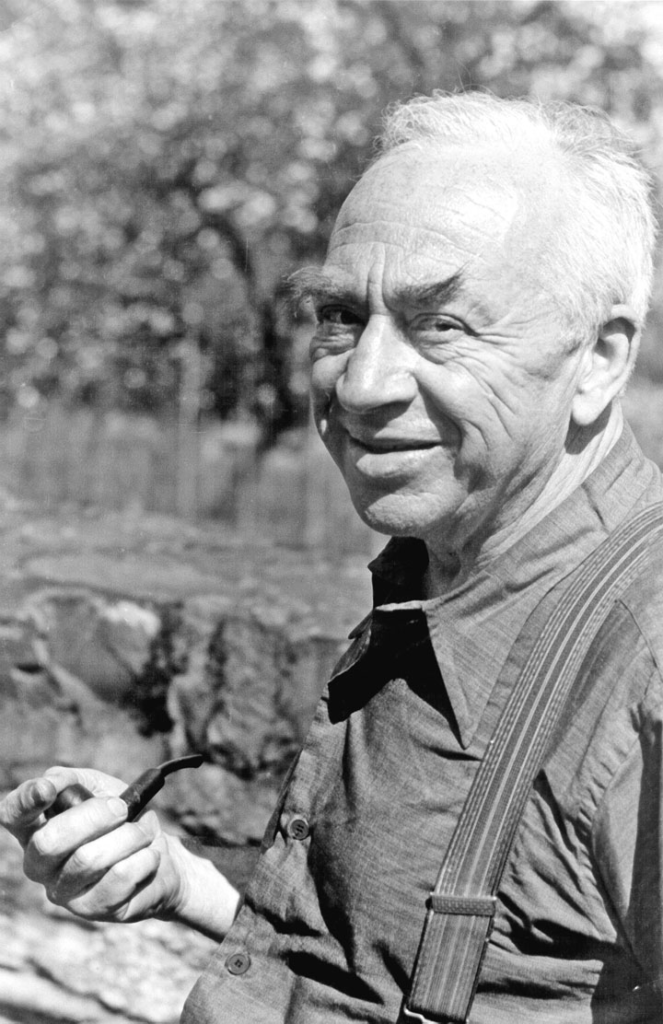

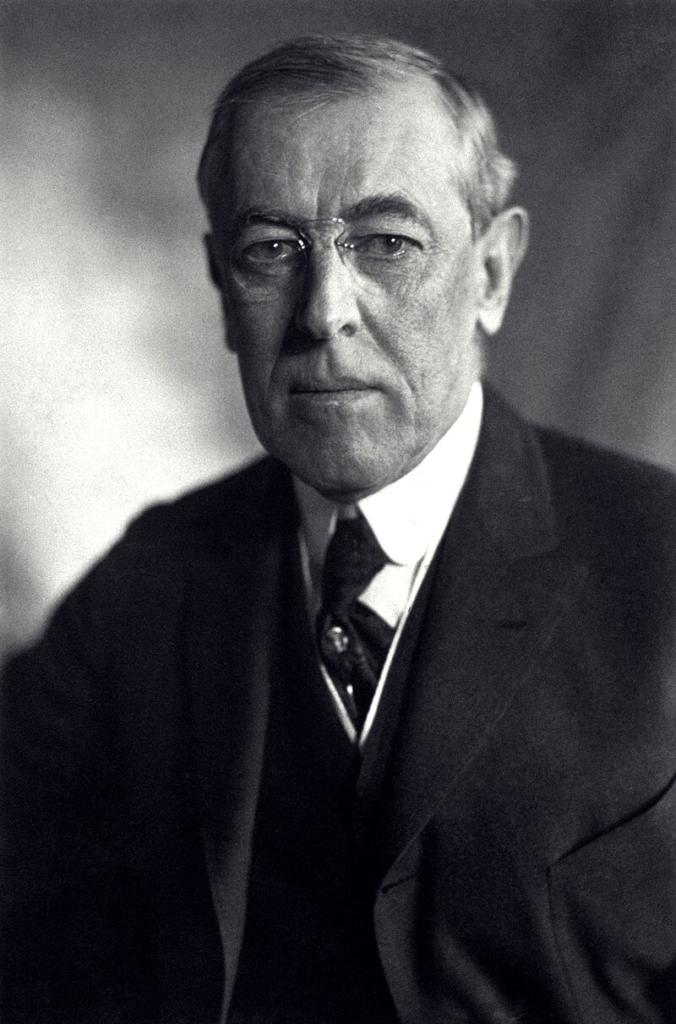

Oprecht’s commitment was recognized by Churchill and Roosevelt.

Above: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965)

Above: US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945)

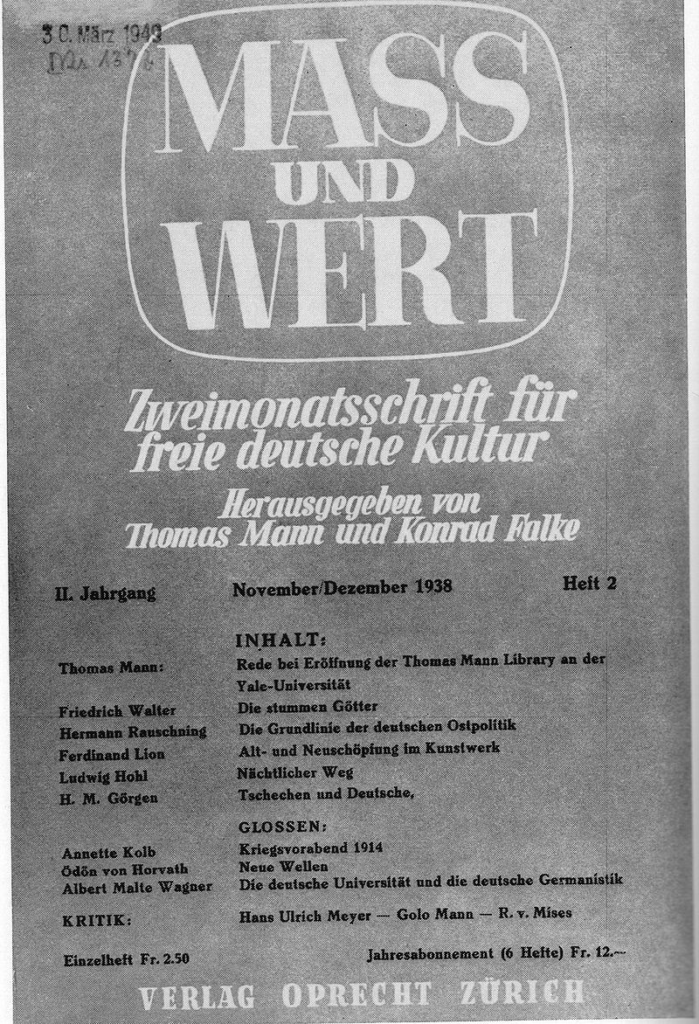

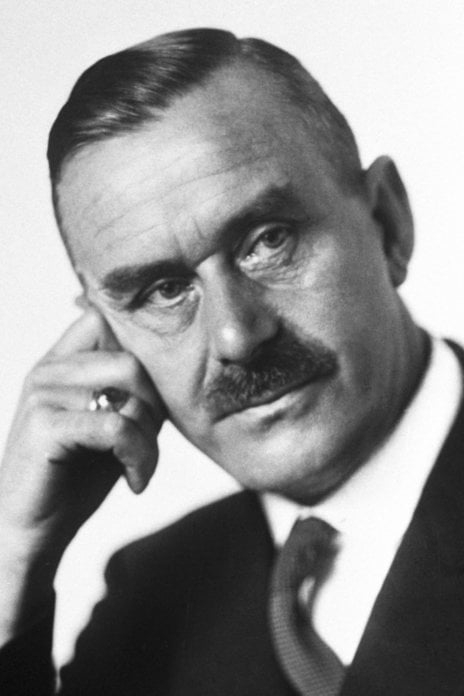

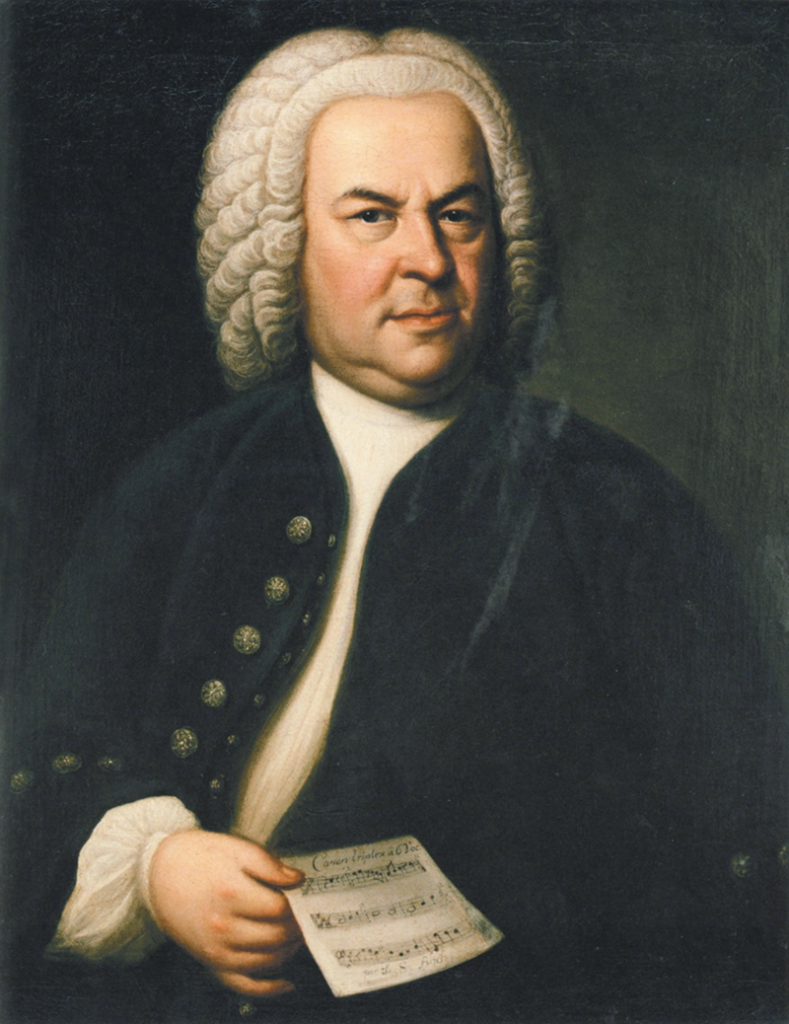

The journal Mass und Wert (Measure and Value)(1937 – 1940) was published with the collaboration of Thomas Mann, as he and his family were among the friends who had fled.

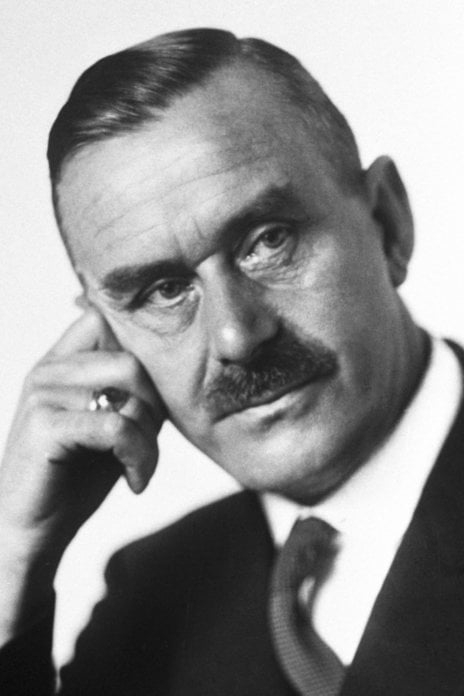

Above: German writer Thomas Mann (1875 – 1955)

At a time when everyone felt threatened, Emil and Emmie Oprecht radiated an unshakable confidence that power could not be ceded to the dictators.

They were filled with the will to help and encouraged others to do so, even under external threat.

For example, the German Reich had put a bounty on Emil Oprecht’s head.

Moreover, the German Embassy was within sight of Oprecht’s apartment.

“A carefree man,” says Christoph Dejung.

When the Jewish theater director and owner Ferdinand Rieser (1886-1947) emigrated to America in 1938, he appointed Emil Oprecht as managing director of the Zurich Schauspielhaus.

Above: Schauspielhaus, Zürich, Switzerland

A literary expert and organizational talent, Oprecht brought the theater to its peak.

He was able to hire many of the refugee actors and directors under the direction of Oskar Wälterlin and Kurt Hirschfeld.

Important plays by Bert Brecht celebrated their world premieres.

The Theater am Pfauen was at its peak, despite threats from massively protesting opponents who would have preferred to see the theater under pro-Nazi management.

Oprecht was always present in times of internal disputes or problems with the authorities, even in his military uniform.

With his calm manner, he always found a balance between his opponents.

Ferdinand Rieser died shortly after his return from exile.

After serious difficulties with his widow and the city, Oprecht and his team were able to continue running the theater with numerous premieres by Max Frisch and Friedrich Dürrenmatt.

Above: Max Frisch (1911 – 1991) and Oskar Wälterlin (1895 – 1961)

However, Emil Oprecht didn’t experience many exciting performances anymore.

Cancer was the cause of his increasing weakness.

Nevertheless, he continued to throw himself into his work, never missing a session, until his death on 9 October 1952.

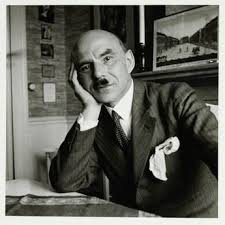

Above: Emil Oprecht

- Golo Mann: (1909 – 1994):

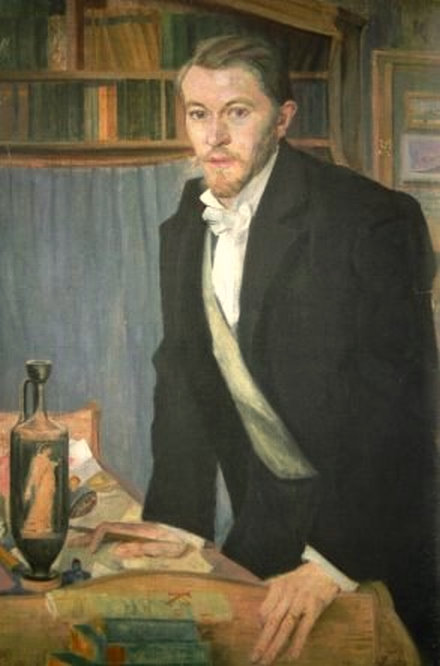

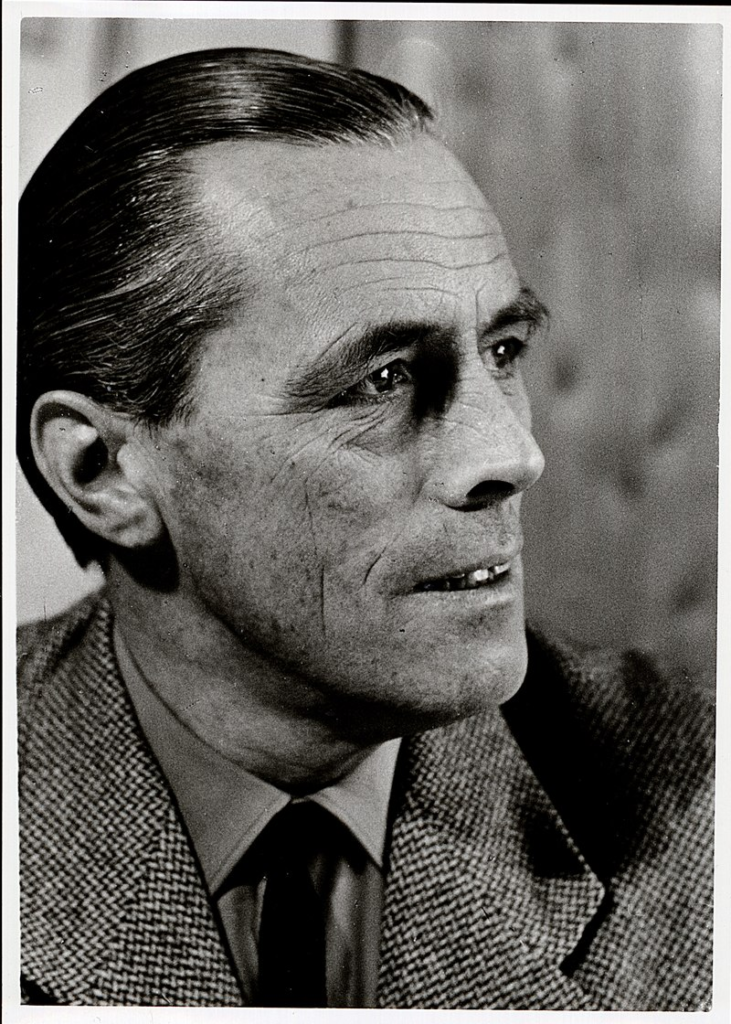

Above: Golo Mann

Golo Mann’s father, Thomas, was good friends with Emil Oprecht and, together with Konrad Falke, published the journal Mass und Wert (Measure and Value) through Oprecht’s publishing house.

These various relationships ultimately made it possible for Golo Mann to write his German History of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Altnau from 1956 to 1957.

The success of this book enabled Golo Mann, who, like his father, had gone into American exile, to return permanently to Europe.

It seemed as though nothing could stand in the way of his academic career.

However, when his appointment to the University of Frankfurt fell through, Golo Mann withdrew from teaching and lived as a freelance writer in his parents’ home in Kilchberg on Lake Zurich and in Berzona in Ticino.

Above: Mannhaus, Kilchberg, Canton Zürich

Above: Mannhaus, Berzona, Canton Ticino

In Kilchberg, Berzona, and again in Altnau, he wrote his magnum opus, Wallenstein – His Life Told by Golo Mann.

Telling history in this way was completely frowned upon in academic historical circles in 1971, the year this monumental biography was published, but Golo Mann didn’t care, and neither did the thousands of his readers.

Despite all the hostility from academic circles, Golo Mann was awarded honorary doctorates twice, notably in France and England, but not in the German-speaking world.

Moreover, he was honored with a series of literary prizes for his books:

He received the Schiller Prize, the Lessing Ring, the Georg Büchner Prize, the Goethe Prize, and the Bodensee Literature Prize.

The latter must have particularly pleased him, as the Lake had smiled upon the beginning of his literary fame.

Above: Gasthof Zur Krone, Altnau

Anything but a mystic, Golo Mann was the son of Thomas Mann and belonged to one of the most famous literary families in the world.

Not only his father but also his uncle Heinrich and his siblings Erika, Klaus, Monika, Elisabeth, and Michael were writers.

Writing was in Golo Mann’s blood.

This does not mean that it always came easily to him — on the contrary.

Like all of Thomas Mann’s children, Golo lived in the shadow of his overpowering father and did not feel particularly privileged to be the son of a Nobel Prize-winning author.

Golo Mann saw himself primarily as a historian, distinguishing himself from his father, the novelist.

Nevertheless, he maintained a decidedly literary approach to history.

Two of his books bear titles that reflect this perspective: Geschichte und Geschichten (“History and Stories“) and Geschichtsschreibung als Literatur (“Historiography as Literature“).

His narrative style earned him condescending criticism and mocking scorn from fellow historians, but this did not prevent the general public from enthusiastically embracing his books.

Golo Mann’s first bestseller was largely written in Thurgau.

Time and again, he retreated for several weeks to the Gasthaus Zur Krone at Hafenstraße 368 in Altnau, first in the summer of 1949.

His memories of Lake Constance were published in 1984 in the anthology Mein Bodensee: Liebeserklärung an eine Landschaft (“My Lake Constance: A Love Letter to a Landscape“) under the title Mit wehmütigem Vergnügen (“With Wistful Pleasure“).

Regarding the Krone, he wrote:

“On the ground floor, there was a tavern.

On the first floor, the owner’s family had set up their apartment.

On the second floor, there were a few small rooms connected by a vestibule, always available to close friends of the Pfisters, such as the bookseller Emil Oprecht and his wife, Emmi.

Thanks to my friend Emmi, they became my refuge, my place of work and rest.“

In 1956 and 1957 he spent many weeks at the Zur Krone inn in Altnau on Lake Constance, writing his German History of the 19th and 20th Centuries.

It was published in July 1958 as a two-volume work and became an immediate bestseller.

Above: Gasthof Zur Krone, Altnau

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1201)

Güttingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 1,703)

Above: Coat of arms of Güttingen

The hamlet of Güttingen, whose center is approximately one kilometer from the shores of Lake Constance, lies on the Kreuzlingen-Romanshorn road.

Güttingen borders the communities of Langrickenbach, Altnau, Kesswil and Sommeri.

The Güttinger Forest belongs to the municipality.

Above: Güttingen, Canton Thurgau

The Stone Age riverside settlements of Rotfarb/Moosburg, dating back to the 4th millennium BC, are documented by finds.

Early medieval settlement is documented by an Alemannic burial ground.

The village was first mentioned in documents in 799 as Cutaningin and in 1155 as Guthingen.

The Güttingen Treasure, discovered in a field in Güttingen in 2023,

dates back to the Bronze Age (around 1500 BC).

(A Bronze Age treasure hoard has been uncovered in Güttingen, Switzerland.

The discovery was made by a metal detectorist, who upon realizing the significance of the find notified local authorities.

Archaeologists conducted a block recovery at the find site by removing 50x50x50 cm of earth.

The block was transported to a laboratory in Frauenfeld, where bronze discs, spiral rings, and over 100 amber beads that date from the Middle Bronze Age around 1500 BC were recovered.

The block contained 14 bronze discs, each decorated with three circular ribs and a round “spike” in the middle.

On the inside is a narrow grommet from which a thread or leather strap could be pulled through.

Based on similar examples from this period, the discs are likely part of a high status jewelry piece which had spirals hung between the discs as spacers.

Eleven such spacer spirals were found in the block, as well as eight larger spirals made from fine gold wire.

More than 100 amber beads the size of pinheads were removed from the block with tweezers, in addition to two finger rings, a bronze arrowhead, a beaver tooth, a perforated bear tooth, a rock crystal, a fossilized shark tooth, a small ammonite, and several lumps of polish ore.

A study of the area where the block recovery took place has yielded no evidence of a burial, suggesting that the treasure hoard was deposited intentionally either for security or during a time of conflict.

There are very few Bronze Age settlements known in the Güttingen area, except for a large Bronze Age pile-dwelling village, however, this site dates from 1000 BC.

The objects, some of which are very sensitive, are currently being restored so that they can be exhibited in the Museum of Archaeology in Frauenfeld.)

Above: Thurgau Museum of Archaeology, Frauenfeld

In 883, Emperor Charles the Fat transferred Güttingen to the Abbey of St. Gallen.

Above: Coinage of Holy Roman Emperor Charles III (839 – 888)

In addition to the Abbey of St. Gallen, the Bishop of Konstanz also had property in Güttingen.

From 1159 to 1357, the Barons of Güttingen acted as landlords and owners of the Freibagtei of Güttingen.

Above: Coat of arms of the von Güttingen family (12th – 14th centuries)

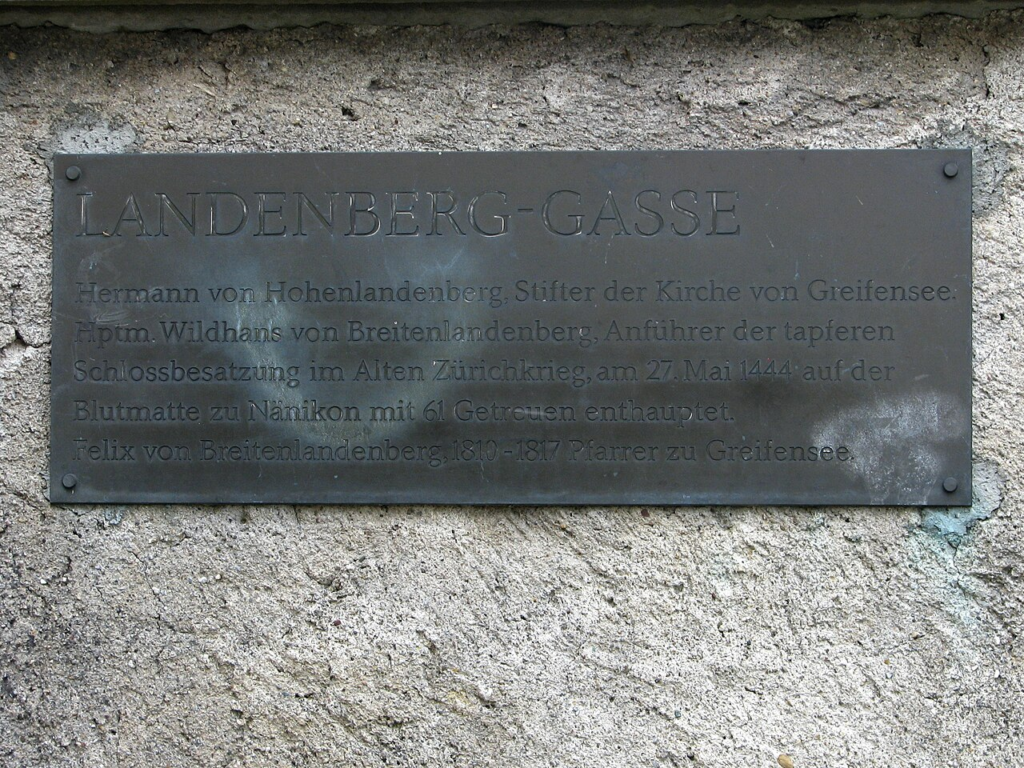

In 1359, the Bailliage came into the possession of the Lords of Breitenlandenberg.

Above: Landenburg Alley, Griefensee, Canton Zürich

In 1452, Heinrich Ehinger, the Mayor of Konstanz, sold Moosburg and Kachel Castle to the Bishop of Konstanz for 700 guilders.

Above: Moosburg Castle, Güttingen

Above: Kachel Castle, Bacharach, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Until 1798, the episcopal high bailiff administered the lower court of Güttingen from the castle as the episcopal-Konstanz high bailiff of Güttingen.

Above: Güttingen Castle, Güttingen

In the Treaty of Meersburg of February 1804, Güttingen came into the possession of the Canton of Thurgau.

Above: Meersburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

In 1870, the administrations of the spatially identical local and

municipal communities of Güttingen were merged to form the unified municipality of Güttingen.

Above: Parity church and rectories, Güttingen

- Paula Roth (née Pauline Roth)(1918 – 1988) grew up in Güttingen.

Above: Paula Roth

After running various other businesses, she was the owner and landlady of the Bellaluna Inn in the Albula Valley in the canton of Graubünden from 1965 until her murder in the spring of 1988 .

She made a name for herself as a storyteller, healer, and artist, who painted, wrote, and crafted objects.

In 1988, three men took advantage of the isolated location of the Bellaluna and broke into the inn.

When the landlady confronted one of the thieves, she was fatally stabbed several times.

The murderer and his accomplices were caught and sentenced to long prison terms.

In 1998, works by Paula Roth were shown in the exhibition Four Women – Four Worlds at the Open Art Museum in St. Gallen.

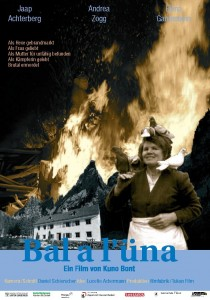

Her life was made into a film by Kuno Bont in 2009 entitled The Shimmering Landlady – Bal a l’üna (Death at One), Life and Death of the Outsider Paula Roth.

Above: Bellaluna, Filisur, Canton Graubünden, Switzerland

When Paula Roth was brutally murdered with 12 stab wounds on the evening of 18 April 1988, the case attracted attention beyond the country’s borders.

A good two years after the crime, the three perpetrators, one Swiss and two Yugoslavs, were convicted by the Cantonal Court of Graubünden for the murder of the original innkeeper.

The single elderly woman, who didn’t trust any bank and preferred to keep her money in tins at home, had to give up her life for a few thousand francs.

So many stories surround Paula Roth that it is difficult to separate truth from legend.

One thing is certain:

Paula Roth was born in 1918 in Güttingen and moved with her father almost every year.

By the time she was 50, she had moved around 40 times.

Sometimes by handcart, sometimes by horse-drawn carriage, later by motor trailer, and finally by tractor.

Finally, she married.

It was a horse-trading deal, she said.

Paula Roth had two children with her husband, Paul Bühler, who spent most of their marriage on active duty.

Paula Roth became ill and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital due to delusions.

Upon her return, Paula Roth filed for divorce.

The divorce was contested and both children were ultimately awarded to the father.

The mother sought help from a naturopathic doctor.

Paula Roth not only eagerly absorbed knowledge of medicinal plants, but above all, mysticism, everything supernatural, fascinated her.

After various jobs in Canton Graubünden, she made one last attempt to put down roots:

In the remote Bellaluna.

This is the epicenter of ore mining history in the Albula Valley.

Only a miner’s and management house remains, which she planned to convert into a restaurant.

According to legend, this was one of the most notorious witches’ haunts in Graubünden.

Witches were said to meet here at one o’clock on a full moon.

Paula Roth’s interests and hobbies, however, were not limited to naturopathy or entertaining her guests with the harmonium.

During the long winter months, hardly any guests ventured into the remote inn.

Paula Roth had time to paint, write poetry, or do crafts.

In the 20-odd years that Paula Roth had been the hostess of the Bellaluna, many national celebrities had passed through the door, as documented by 20 guest books.

Doing justice to such a dazzling personality in a film was no easy task.

Werdenberg-based director Kuno Bont explained that his goal was to find a new, non-judgmental language.

Lucette Achermann, who published a biography about Paula Roth’s life in the Albula Valley, was convinced that in Kuno Bont she had found the right person for a film project:

“He treats her with the necessary respect.”

In his film, Bont blends documentary with fictional material.

With the death of Paula Roth, the Bellaluna fell into a 13-year slumber, from which it was revived by the Brazerol brothers in 2001.

Today, the Bellaluna – in the spirit of the former landlady – is a cultural and gastronomic meeting place for locals, travelers and other free spirits.

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1204)

Kesswil, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 995)

Above: Coat of arms of Kesswil

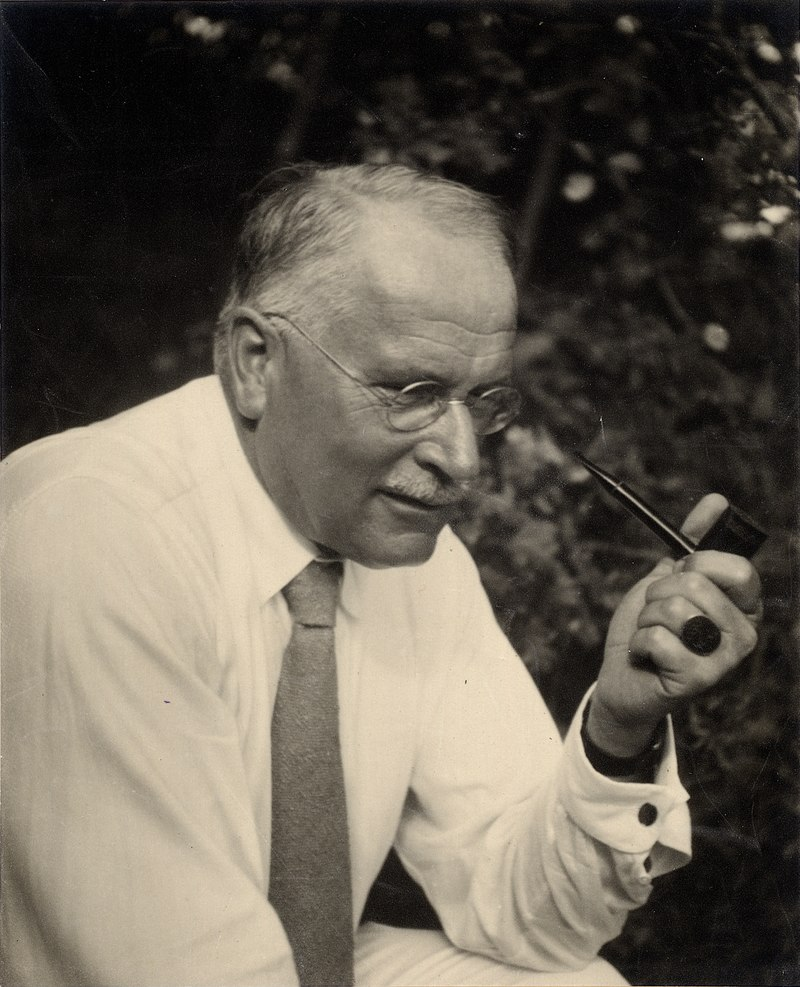

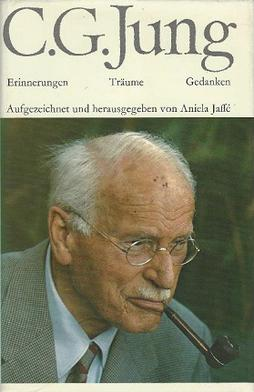

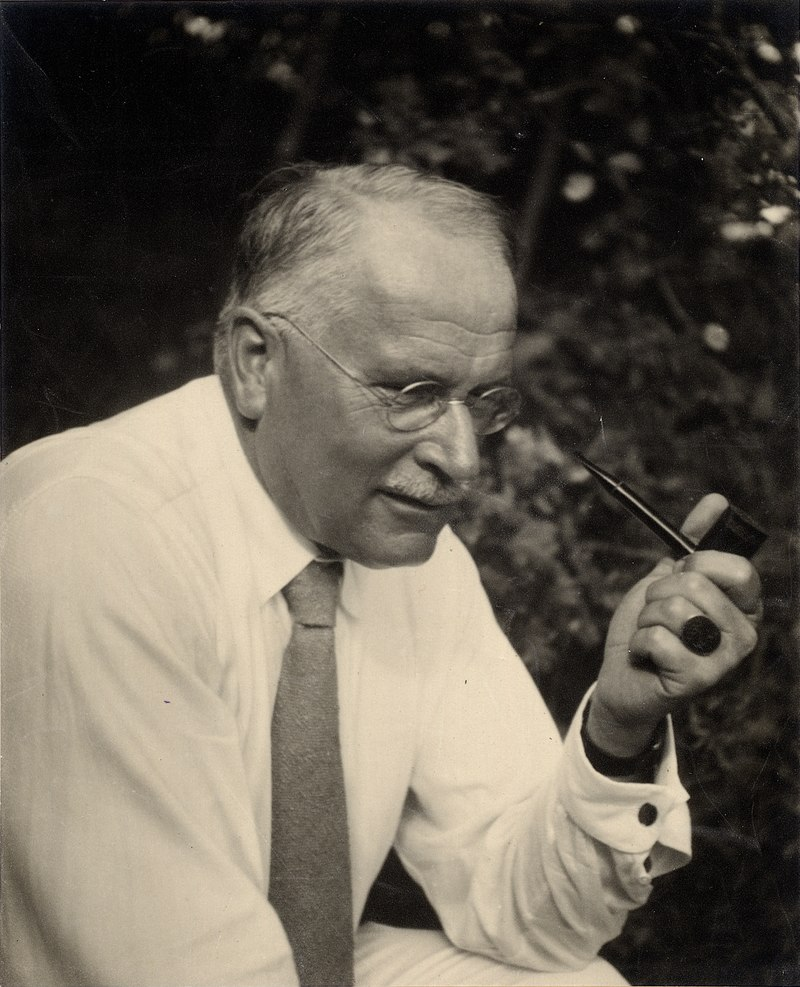

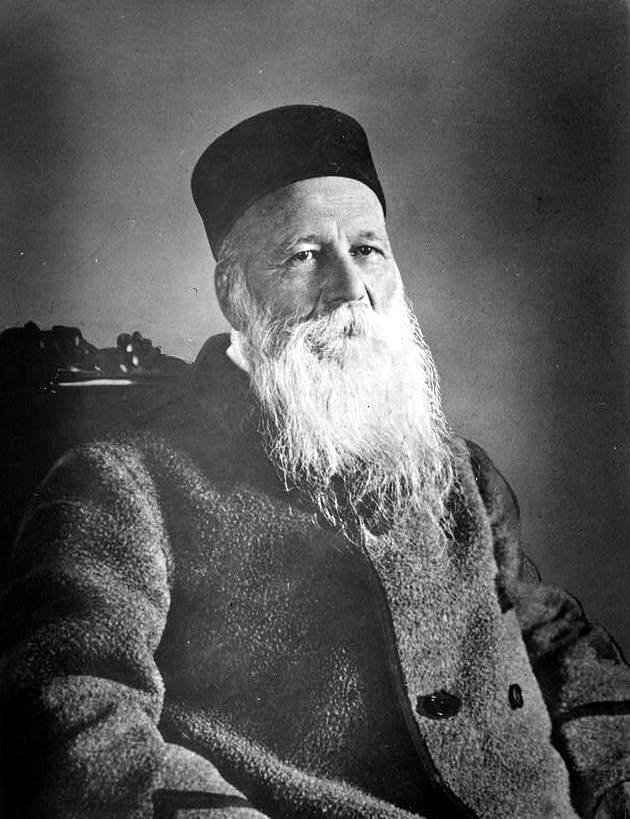

The village was the birthplace of the influential psychiatrist Carl Jung.

Professor Jung, one of the founders of analytical psychology, was born in Kesswil on 26 July 1875.

Above: Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875 – 1961)

Kesswil was first mentioned in 817 as Chezzinwillare.

In the 9th century, the Abbey of St. Gall owned land in Kesswil.

In the 13th century, the Münsterlingen Abbey also acquired land and sovereign rights in the town.

From the late Middle Ages until 1798, Kesswil was an Abbot’s Court of St. Gall, administered from the Romanshorn office.

In 1429, the Münsterlingen Monastery permitted the construction of a chapel.

A mass benefice is documented in 1451.

Above: Münsterlingen Abbey

In 1529, the parish, which also included Dozwil, converted to the Reformation.

From 1588, the pastor also served Uttwil, which had the status of a branch church since 1618.

From 1816 onwards, Kesswil formed a municipal parish that covered the territory of the local parish, which is why the two parishes were united in 1870 to form the Einheitsgemeinde.

In the 19th century, Kesswil was home to arable farming, viticulture, and fishing, as well as a weaving mill, trade, and small businesses.

With the transition to livestock and dairy farming — a cheese-making company was founded in 1859 — field fruit growing intensified.

Above: Kesswil

The Seelinie (lake line), opened in 1871, initially did not bring economic growth to the village.

Around 1900, there were a few embroidery shops in Kesswil.

Above: Kesswil Community Center

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Nussbaum Matzingen offered 85 jobs in 2005.

Above: Nussbaum Matzingen, Kesswil

Further employment opportunities can be found in agriculture, including fruit and berry growing, and in the Roth Pflanzen tree nursery.

With the single-family homes and residential buildings built after 1980, Kesswil developed into a rural residential community.

Above: Old Mill, Kesswil

On 26 July 1875, Carl Gustav Jung, the founder of Analytical Psychology, was born in the parsonage of Kesswil as the son of the Protestant-Reformed pastor Johann Paul Achilles Jung and his wife Emilie.

Above: Pfarrhaus (parsonage), Kesswil

Three months after his birth, the Jung family moved to Laufen am Rheinfall.

Above: Rhine Falls and Laufen Castle, Canton Schaffhausen

Today, a commemorative plaque honors C. G. Jung.

Three years later, in the neighboring house, the philosopher, psychologist, and educator Paul Häberlin was born.

Above: Swiss philosopher Paul Häberlin (1878 – 1960)

Häberlin was a Swiss philosopher, psychologist and educator who at different times in his career took the standpoint that either religion or theoretical knowledge was the answer to human problems.

He always gave philosophy an important role, but religion was to him the only way man could understand his real position in existence.

Häberlin made contributions to characterology and psychotherapy, and was especially successful in treating psychopathic youth and teens.

He was made a full professor of philosophy, psychology and pedagogics at the University of Basel.

Paul Häberlin found his way to philosophy through Lake Constance.

As a young man, he experienced a kind of vision on the Lake’s shore:

“The Lake became a revealing symbol — a symbol of unity in diversity, of stillness in motion.“

Above: Bathhouses, Kesswil

Jung and Häberlin were well acquainted.

They shared common interests and mutual friends, such as Ludwig Binswanger, the director of the Kreuzlingen Bellevue Sanatorium.

Above: Swiss psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger (1881 – 1966)

Above: Bellevue Sanatorium, Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau

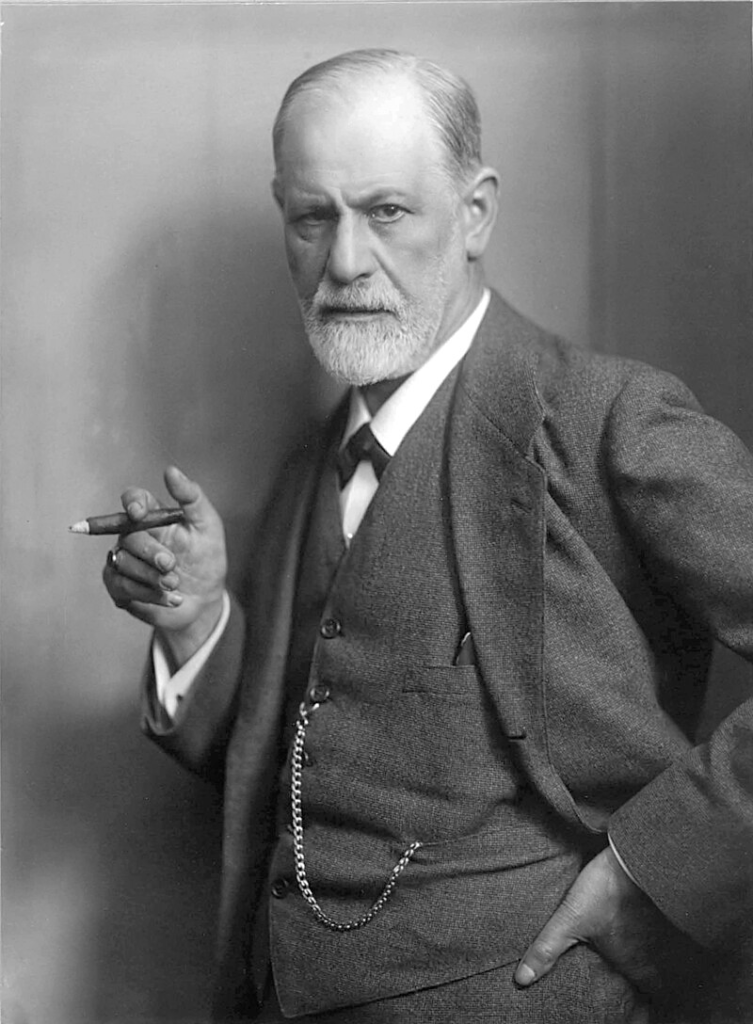

Both Binswanger and Jung were in contact with Sigmund Freud.

In a letter to Freud, Jung wrote about Häberlin:

“He is a far-sighted mind.

His character is brave and combative.

He was born in the same village — he as the son of the schoolmaster, I as the son of the pastor.

He studied both theology and philosophy, as well as the natural sciences.

Nor does he lack a mystical inclination, which I especially appreciate in him.

For it guarantees a depth of thought that goes beyond the ordinary and an understanding of broader connections.“

Above: Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

- Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961):

Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology.

He was a prolific author, illustrator, and correspondent, and a complex and controversial character, in certain ways best known through his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

Jung’s work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, psychology and religious studies.

He worked as a research scientist at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital in Zürich.

Above: Burghölzli Klinik, Zürich, Switzerland

Jung established himself as an influential mind, developing a friendship with Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, conducting a lengthy correspondence paramount to their joint vision of human psychology.

Jung is widely regarded as one of the most influential psychologists in history.

Freud saw the younger Jung not only as the heir he had been seeking to take forward his “new science” of psychoanalysis but as a means to legitimize his own work:

Freud and other contemporary psychoanalysts were Jews facing rising antisemitism in Europe.

Jung was Christian.

Freud secured Jung’s appointment as President of Freud’s newly founded International Psychoanalytical Association.

Above: Grand Hotel, Nuremburg, Bavaria, Germany – The IPA was established here in 1910.

Jung’s research and personal vision, however, made it difficult to follow his older colleague’s doctrine, and they parted ways.

This division was painful for Jung and resulted in the establishment of Jung’s analytical psychology, as a comprehensive system separate from psychoanalysis.

Above: Carl Jung

Among the central concepts of analytical psychology is individuation — the lifelong psychological process of differentiation of the self out of each individual’s conscious and unconscious elements.

Jung considered it to be the main task of human development.

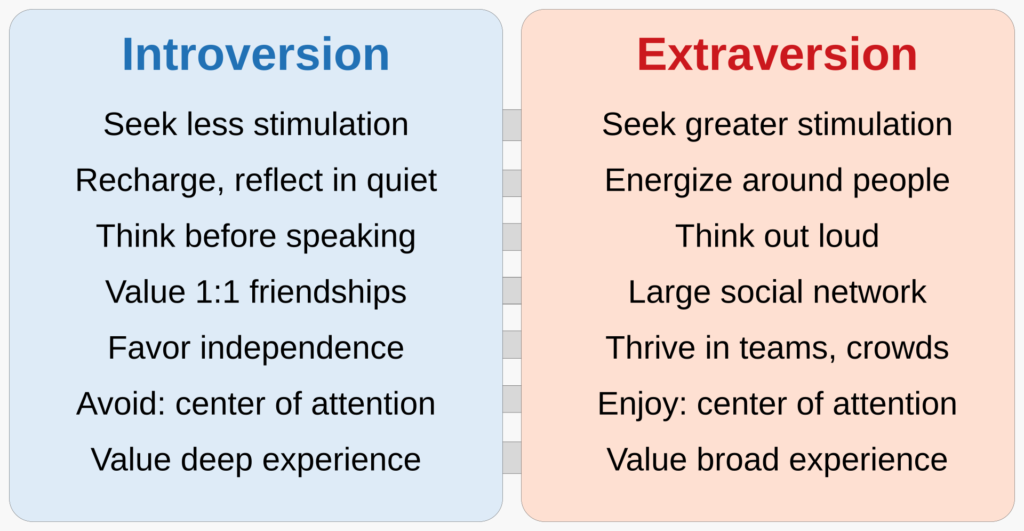

He created some of the best-known psychological concepts, including synchronicity (events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection), archetypal phenomena (a universal, inherited idea, pattern of thought, or image that is present in the collective unconscious of all human beings), the collective unconscious (the belief that the unconscious mind understands instinctively innate symbols from birth), the psychological complex (a structure in the unconscious that is objectified as an underlying theme — like a power or a status — by grouping clusters of emotions, memories, perceptions and wishes in response to a threat to the stability of the self), extraversion and introversion.

His treatment of American businessman and politician Rowland Hazard in 1926 with his conviction that alcoholics may recover if they have a “vital spiritual or religious experience” played a crucial role in the chain of events that led to the formation of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Above: Rowland Hazard III (1881 – 1945)

Above: Logo of Alcoholics Anonymous

Jung was an artist, craftsman, builder and prolific writer.

Many of his works were not published until after his death.

Some still remain unpublished.

Above: Carl Jung

Above: Jakobus (1866 – 1964) and Julie Weidenmann (1882 – 1942)

The Protestant parsonage has always been a stronghold of the word.

As interpreters of biblical stories, pastors were professional readers.

As preachers, they were also naturally inclined to write secular texts and be authors.

The duties of pastors’ wives, however, were of a different nature.

They were expected to support their husbands, be capable housewives, good mothers, and serve as role models for the women in the congregation.

Most importantly, their home was to be open to all.

But the word belonged to the men.

As the Apostle Paul stated, women were to remain silent in church.

All the more surprising, then, must it have been for visitors to the Kesswil parsonage in the 1920s to find not a poet-pastor, but a poet-pastor’s wife.

Above: Kesswil Church

In 1918, Pastor Jakobus Weidenmann became the pastor in Kesswil.

He sympathized with a religiously colored socialism and published many politically charged newspaper articles in which his desire for social change clashed with the prevailing conservative stance.

He also published several books, such as Pestalozzi’s Social Message (1927), Fear Not! Man and Death (1944), and Confessionalism as a Mortal Sin Against the Holy Spirit (1958).

Above: Jakobus Weidenmann, Pestalozzi’s Social Message

Above: Swiss social reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827)

Like his wife, the teacher and poet Julie Boesch, he was also socially engaged.

They lived in Kesswil for a total of ten years.

The parsonage was “a refuge, workplace, and gathering place for all kinds of poets, musicians, and painters from spring until late autumn“, as Jakobus Weidenmann put it.

Julie, who humorously allowed herself to be called ‘Weidenfrau‘, felt sheltered in the landscape by the Lake.

Her poetry reflected a sinking, an almost mystical oneness with nature.

One fellow writer described her as “spiritually akin to Droste and the Dominican mystic Suso of Konstanz“.

They were friends with Hedwig and Fritz Mauthner.

Jakobus Weidenmann gave a speech at Fritz Mauthner’s funeral.

In 1928, Jakobus Weidenmann was transferred to the Linsebühl Church in St. Gallen.

The farewell was difficult for both of them.

During the short time her husband served as pastor there, Julie Weidenmann-Boesch turned their home in Kesswil into a center of literary life on Lake Constance.

The genius loci, the spirit of the place, was favorable to Julie Weidenmann.

Above: Bathhouse, Kesswil

Julie Weidenmann-Boesch had a similar experience as Paul Häberlin.

It was the Lake that made her a poet.

Paul Häberlin and Julie Weidenmann maintained a mystical connection to the lake.

To them, it was both revelation and inspiration.