(Part 2 of “Peace of Mind” / Part 1 of “The road to Rorschach“)

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Sunday 23 March 2025

We can’t go on any more with this notion

Just saving up to buy a ball and chain

Seems it’s all arranged.

You can’t buy time and you can’t buy emotion

What have you and I been waiting for?

The winds of change are blowing hard in our direction

We can’t go back and we can’t stand still

The winds of change may try to blow away my affection

But they never will.

They say in your life there’s a tide for the taking

And if you wait

they say it goes away

It just flows away.

I know it may be a mistake we are making

But if we don’t try

we’ll never know.

The winds of change are blowing hard in our direction

We can’t go back and we can’t stand still

The winds of change may try to blow away my affection

But they never will.

The world turns, but my life last week remained relatively tranquil.

US President Donald Trump held a two-hour conversation with Russian President Vladimir Putin to discuss the war in Ukraine.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

Above: US President Donald Trump

Putin rejected Trump’s call for a ceasefire, but said he would refrain from attacking Ukraine’s energy infrastructure for 30 days.

Above: Flag of Russia

Above: Russian President Vladimir Putin

Soon after making that promise Russia launched a big attack on civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, in Ukraine.

Above: Flag of Ukraine

Trump also spoke to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, offering to help source Patriot missiles from Europe and suggesting that America could run Ukrainian nuclear plants to protect them from Russian aggression.

Above: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky

Trump called for the impeachment of a judge who had ordered the suspension of a program for deporting alleged Venezuelan gang members.

Above: Flag of Venezuela

The White House was accused of flouting the order by going ahead and deporting the Venezuelans to a prison in El Salvador.

Above: Flag of El Salvador

Trump ordered funding to be cut for the agency that supports radio stations, such as Voice of America and Radio Free Asia, which have upheld the promotion of democracy and reported extensively on human rights abuses.

Above: Logo of Voice of America

The White House said they were outlets for “radical propaganda“.

Above: The White House, Washington DC, USA

China was delighted.

Above: Flag of China

Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa said Trump should designate Ecuadorean criminal gangs as terrorists.

Above: Flag of Ecuador

Noboa also invited America, Brazil and Europe to send soldiers to join his crackdown on gangs.

Above: Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa

Most of the world’s cocaine passes through Ecuador.

The US Senate voted for a Republican spending measure that averted a government shutdown at the last minute.

Chuck Schumer, the Democrat leader in the Chamber, incurred the wrath of his Party by voting for the measure, having said he would oppose it.

Above: US Senator Chuck Schumer

Schumer’s explanation that a shutdown would only empower Trump did little to soothe the progressives in his Party who now consider themselves to be “the resistance“.

Colombia’s Finance Minister quit after just three months in the job amid a quarrel with the country’s left wing President Gustavo Petro over budget cuts.

Above: Flag of Colombia

Petro has recently replaced 12 of his 19 ministers.

Above: Columbian President Gustavo Petro

Israel launched a series of air strikes on Gaza, breaking the ceasefire it signed with Hamas in January.

Above: Flag of Israel

Israel said it was targeting Hamas’ surviving commanders, but over 400 people, including many civilians, were killed, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry.

Above: Flag of Palestine

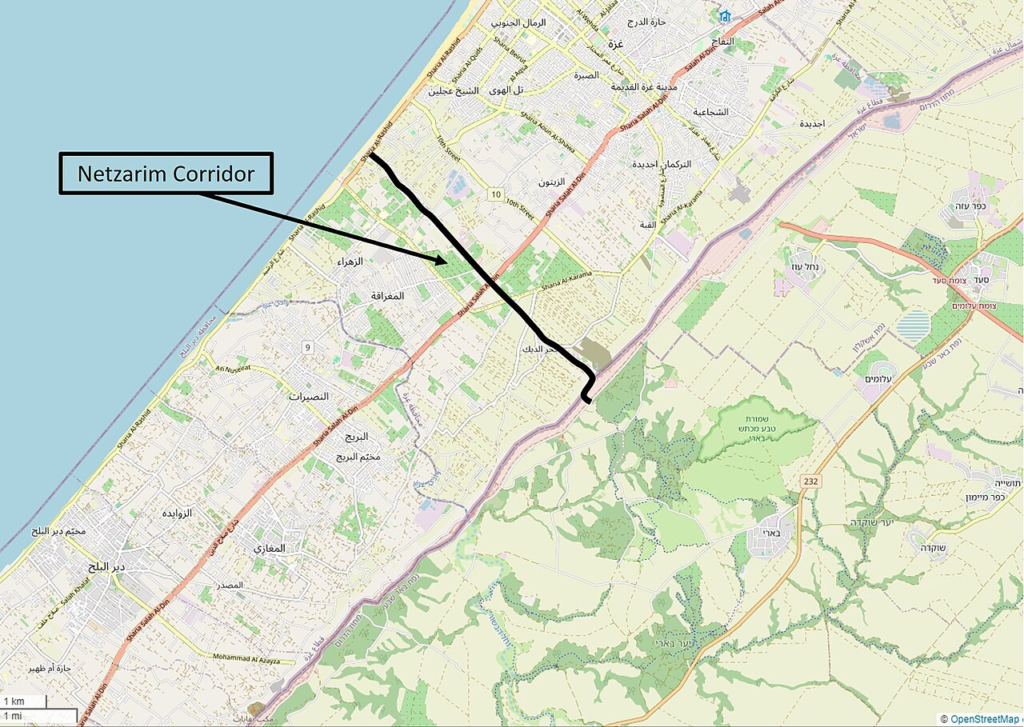

Israel also began a new ground offensive and sent troops back into the Netzarim Corridor, which splits Gaza down the middle.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said this was “just the beginning“.

Above: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

He accused Hamas of rejecting proposals to free more hostages.

Above: Emblem of Hamas

He vowed that all future ceasefire negotiations would be “conducted only under fire“.

Netanyahu tried to sack Ronen Bar, the head of the Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic security service.

Above: Shin Bet Director Ronen Bar

The Shin Bet has been carrying out investigations against some of the Prime Minister’s closest aides.

Above: Logo of the Israel Security Agency

The Attorney General, whom Netanyahu is also trying to sack, said the process must be put on hold because of conflicts of interest.

Above: Attorney General Gali Baharav – Miara

Opposition politicians want to take the issue to the Supreme Court.

Above: Emblem of Israel

American warplanes targeted the Houthis, a rebel group in Yemen that has attacked Israel and ships in the Red Sea.

Above: Flag of Yemen

The Houthis are supported by Iran.

Above: Flag of Iran

The Pentagon said its strikes would be “unrelenting” until the rebels stop their attacks.

Above: The Pentagon, Arlington, Virginia, USA

Nigerian President Bola Tinubu declared a state of emergency in Rivers, an oil-rich state in the Niger Delta.

Above: Flag of Nigeria

He also suspended the state’s Governor and all lawmakers, claiming the Governor, who belongs to an opposition party, had not responded adequately to a pipeline explosion.

Above: Nigerian President Bola Tinubu

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi and Rwandan President Paul Kagame called for an immediate ceasefire in the conflict in eastern Congo, following a meeting in Qatar.

Above: Flag of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Above: Flag of Rwanda

Above: Flag of Qatar

Turkish authorities stepped up their crackdown on the Opposition and arrested Ekrem Imamoğlu, the Mayor of Istanbul, over a range of allegations.

Above: Flag of Türkiye

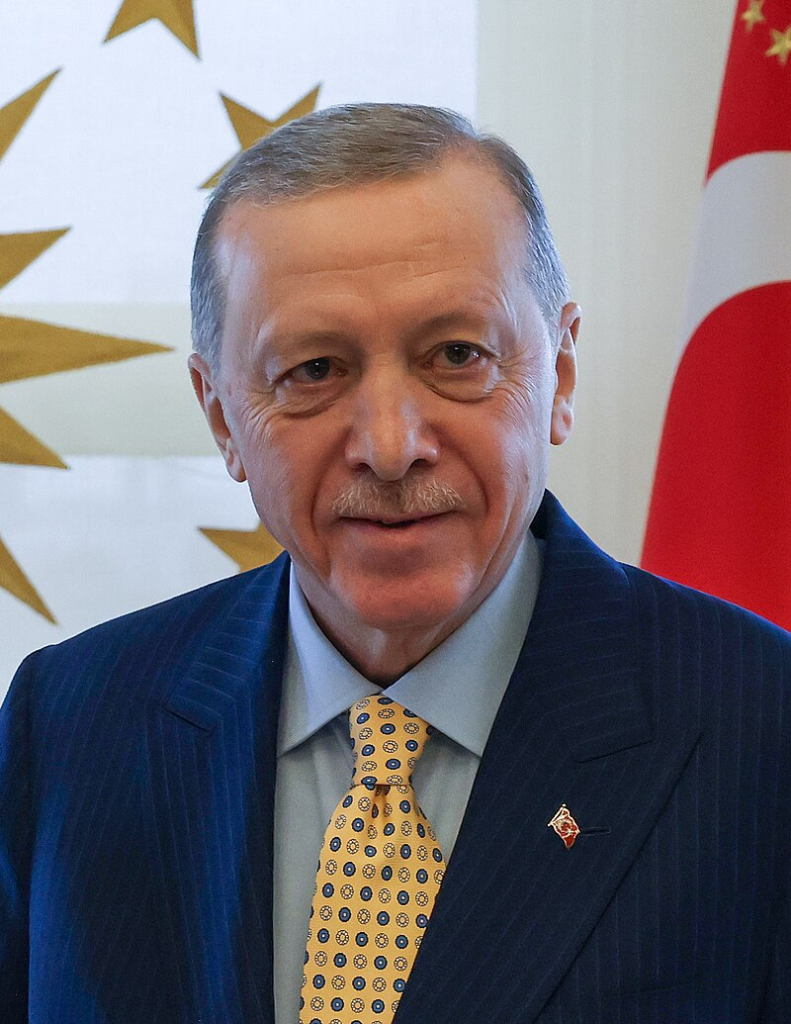

Imamoğlu is likely to be named as the main opposition candidate to challenge Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s strongman President, in an election due in 2028 but which may be called earlier.

Above: Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu

After Imamoğlu’s detention demonstrations were banned in Istanbul for four days.

Above: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

All serious issues.

None of them which I have affected or directly affect me.

At least, not at the moment.

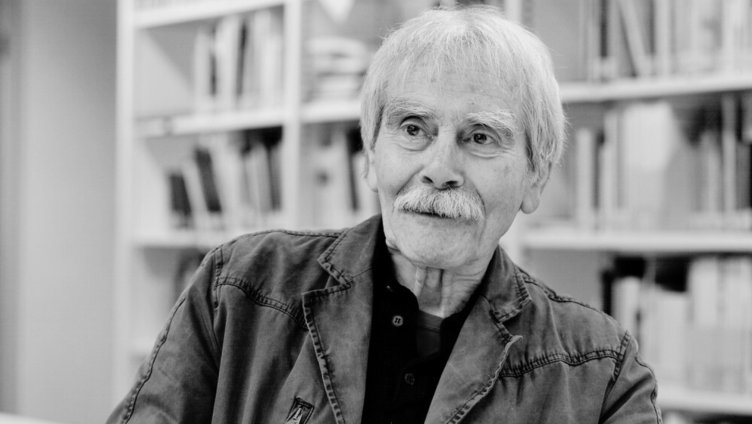

Above: Your humble blogger

Including, in Türkiye the arrest of Imamoğlu and 105 others, including some of the Mayor’s advisors, municipal officials from his Republican People’s Party (CHP) and a top journalist.

Above: CHP logo

Roads to the police station where Imamoğlu had been taken were blocked.

Above: Ekrem İmamoğlu

The authorities also restricted access to social media platforms and closed Metro stations.

Above: Logo of Istanbul Metro

In the name of safeguarding “public order“, Istanbul’s Governor announced a ban on public gatherings for four days.

Above: Istanbul Provincial Governor Davut Gül

Thousands of protesters defied the order the same evening (19 March) by turning up at a rally in front of the Mayor’s office.

Above: Turkish protestors

Turkish prosecution seem to be following an old Soviet formula with Imamoğlu:

“Show me the man and I will find you the crime.“

The quote “Show me the man, and I will find you the crime.“ is commonly attributed to Lavrentiy Beria, the head of Joseph Stalin’s secret police (NKVD) in the Soviet Union.

It reflects the brutal nature of Stalinist repression, where the state could fabricate or uncover crimes to target individuals for political persecution.

Beria was infamous for overseeing purges, mass arrests, and forced confessions, often using terror as a tool to maintain Stalin’s grip on power.

The phrase encapsulates the dangers of unchecked authority and politically motivated prosecutions.

Above: Lavrentiy Beria (1899–1953), head of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) of the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1946

Over the past three years Imamoğlu has faced a slew of investigations and indictments on charges ranging from corruption to insulting election officials who tried to strip him of victory in the 2019 mayoral contest.

The charges now levelled against him include leading a crime organization, abetting a terrorist group, bribery and rigging tenders for government work.

The timing of Imamoğlu’s arrest seems no coincidence.

At a party primary scheduled for 23 March (today), the CHP was expected to nominate Imamoğlu as its presidential candidate in the elections set for 2028 but widely expected to take place earlier.

Imamoğlu helped lead the Opposition to a shocking victory in last year’s local elections, handing Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Development (AK) party their first defeat in over two decades.

Imamoğlu has since enjoyed a comfortable lead over Türkiye’s leader in the polls.

The government seemingly wanted to leave nothing to chance.

A day before (18 March) Imamoğlu was detained, the authorities had revoked the Mayor’s university diploma, because candidates for the presidency in Türkiye are required by law to be university graduates.

Above: Ekrem İmamoğlu’s alma mater

“Even by Erdoğan’s standards, this is a huge step.“, says Ms. Gonul Tol of the Middle East Institute, an American think tank.

Erdoğan may think Trump’s presidency gives him impunity.

“Trump has created such chaos that foreign autocrats sense they can do whatever they want.“

The outlook for Türkiye’s already hobbled democracy appears grim.

Above: Middle East Institute, Washington DC

Mansur Yavaş, the opposition of Ankara, also seen as a possible contender for the presidency, suggested he could meet the same fate as Imamoğlu.

Türkiye is evolving towards a model where political competition is practically impossible.

Above: Ankara Mayor Mansur Yavaş

But does this affect me – a Canadian who simply wants to teach English in Eskişehir?

I am unsure.

Above: Flag of Canada

An online student of mine tells me he would love to protest against the government, but dares not as his company has contracts with the government.

Government supposedly represents people.

If the people cannot suggest improvements, then the government has ceased to represent the people.

Will I return and remain in a country that is becoming increasingly autocratic?

I am uncertain.

For now, I am compelled to remain here until June.

Above: Flag of Switzerland

While I am here I read and write and take the occasional daytrip.

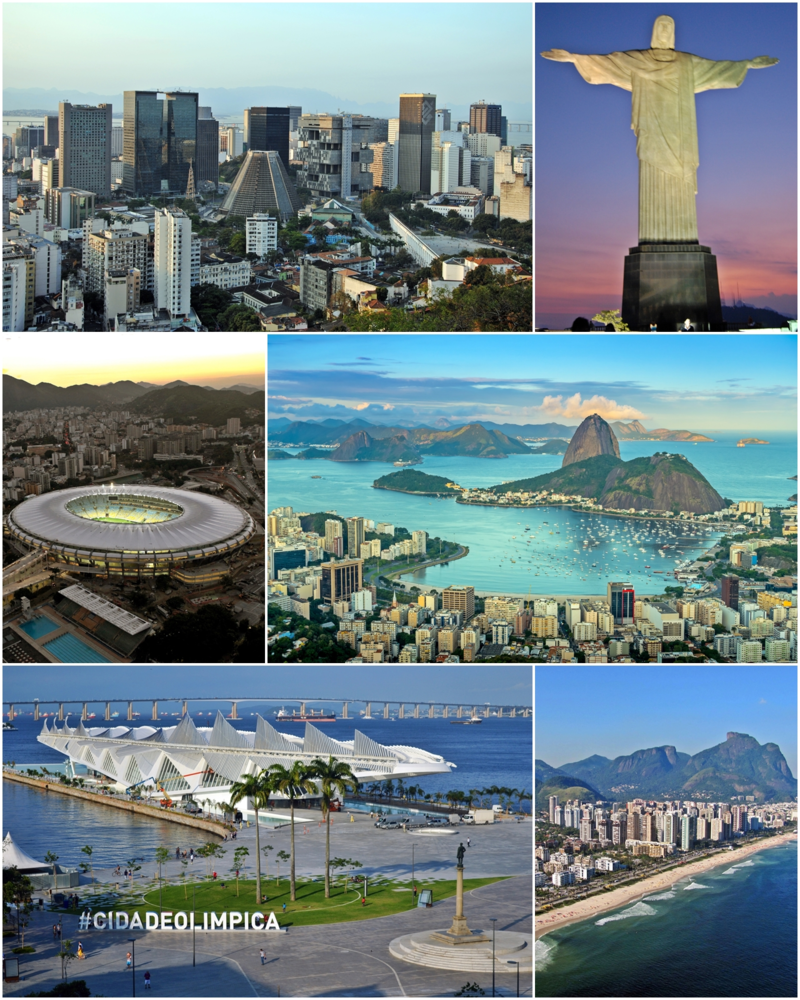

Last Tuesday (18 March), I visited St. Gallen with a stopover in Uttwil.

Above: St. Gallen, Switzerland

Above: Uttwil, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

On Wednesday (19 March) and Friday (21 March), I made shopping trips to Konstanz.

Above: Rheintorturm, Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Moments in my life wherein I had some control.

Above: Heiden, Appenzell Ausserhoden, Switzerland

In my last blogpost I spoke of travelling to Heiden and spoke of what and who was interesting from Landschlacht to Romanshorn.

Above: Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

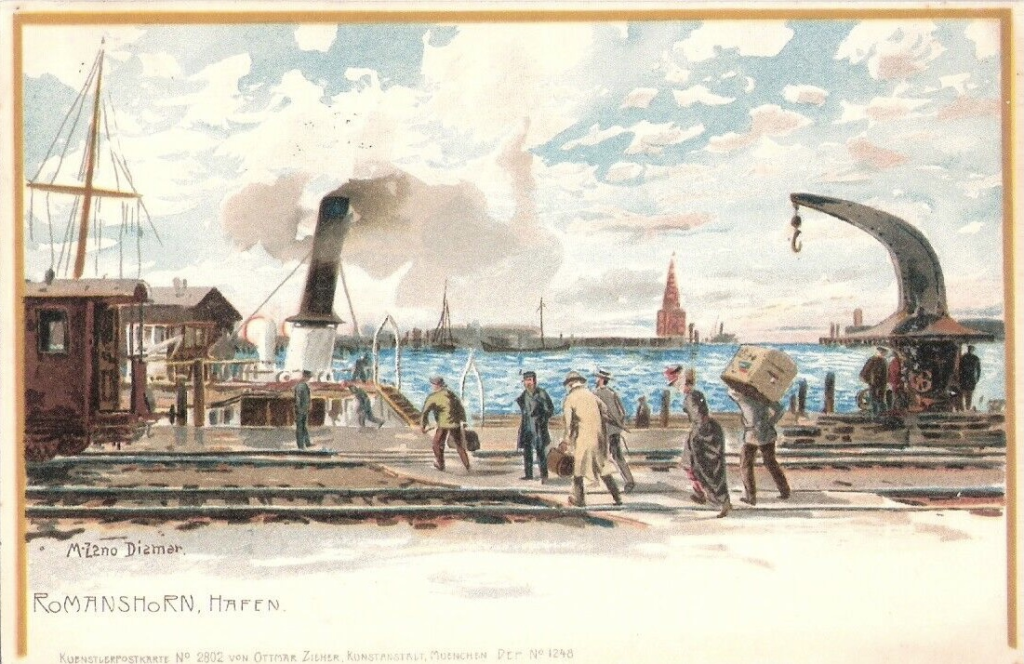

Today I will write about what is compelling on the road from Romanshorn to Rorschach…

Above: Romanshorn, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1214 – 1246)

Romanshorn, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 11,296)

Above: Coat of arms of Romanshorn

The Aach, unhurried and murmuring, completes its long journey here, surrendering itself to the vast embrace of Lake Constance.

As I stand where the river meets the lake, the air is thick with history, the scent of water and timber mingling with the faint metallic tang of rails long rusted by time.

It is a place where movement has always been the undercurrent of existence — ships gliding across the lake’s mirrored surface, trains vanishing into the horizon, and footsteps echoing on stone quays.

Above: The Aach River near Romanshorn

Romanshorn, the name itself carrying the weight of centuries, first etched onto parchment in the year 779.

I imagine monks, cloaked and bent over their work, recording the world as they knew it, oblivious to the centuries that would follow.

Above: The Old Church, Romanshorn

The town, cradled between the lake and the land, has always been a crossroads — where water meets earth, where the past brushes against the present.

The harbor, born in 1841, grew into something vast and vital, its wooden piers trembling beneath the weight of freight and ambition.

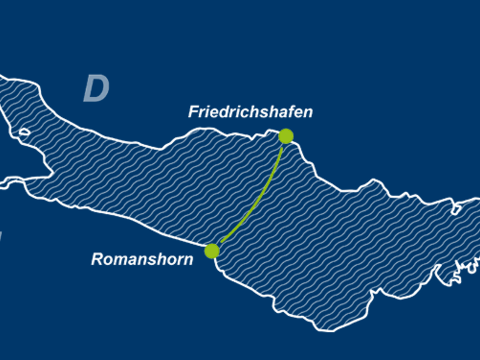

In 1911, over 80,000 freight cars rumbled through, their wheels clattering against iron, carrying whispers of distant cities —Friedrichshafen, Zürich, Winterthur.

Above: Friedrichshafen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

But the world is fickle, and the pulse of industry slowed, until one day in 1976, the great exchange ceased.

Above: Zürich, Switzerland

Above: Winterthur, Canton Zürich, Switzerland

Now, the ferries glide with more leisure than urgency, carrying only passengers and their vehicles, tracing a path across the Lake’s broadest expanse, the journey a mere 40 minutes yet expansive in the way that all water crossings invite contemplation.

And yet, Romanshorn has not withered in the absence of its industrial fervor.

Above: Romanshorn

The Lake, ever patient, has given it another life — one of leisure, of wandering feet on generous quays, where boats bob lazily in the gentle sway of the tide.

The parks, manicured and inviting, stretch green fingers toward the water, and time itself seems to slow in their shade.

The past lingers, woven into the fabric of the place.

Above: Romanshorn

Flames once devoured much of the old town, yet a handful of structures stood defiant.

The Palace, erected in 1829, now hums with the quiet murmurs of guests in its incarnation as a hotel.

The Old Church, its stones whispering of Saints Mary, Peter, and Gall, stands resolute, a Gothic hymn frozen in form, its Romanesque echoes hinting at even older prayers.

Above: Inside the Old Church, Romanshorn

The promenade invites one forward, past the northern boat harbor, where masts creak like old bones in the wind.

Above: Romanshorn

A boulder — the Inseli — juts out from the Lake like a forgotten relic, stoic against the shifting waters.

Above: Inseli, Romanshorn

Further on, a minigolf course and a pool glisten in the afternoon light, their modern frivolity a counterpoint to the weight of history.

Above: Minigolf course, Romanshorn

Beyond, the trails call.

Bicycles trace gentle arcs along the Lake’s edge, while the forest taverns beckon with their promise of respite — steins lifted, laughter spilling into the air, the scent of bread and woodsmoke drifting between the trees.

Here, in Romanshorn, the past is never far, yet the present unfurls in simple pleasures:

The lap of water, the hum of a distant ferry, the golden light lingering on the lake’s surface as day bows to dusk.

No experience has been too unimportant, and the smallest event unfolds like a fate, and fate itself is like a wonderful, wide fabric in which every thread is guided by an infinitely tender hand and laid alongside another thread and is held and supported by a hundred others.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Above: German poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 – 1926)

Jytte Borberg (née Jytte Erichsen) (1917 – 2007) was a Romanshorn-born Danish writer.

Above: Jytte Borberg

In 1921, her family emigrated to the Danish city of Aalborg.

She trained as a laboratory technician and married the psychiatrist Allan Borberg in 1939.

Located in North Jutland, Denmark, Aalborg is a vibrant city known for its rich history and cultural scene.

It was here that Borberg’s family settled after moving from Switzerland.

The urban environment and societal dynamics of Aalborg during her formative years likely provided her with diverse perspectives on Danish life.

Above: Aalborg, Denmark

Until 1968, she moved from place to place because of her husband’s work, until he finally became chief psychiatrist in Viborg, where she settled with their two sons and daughter.

Situated in central Jutland, Viborg is one of Denmark’s oldest cities, characterized by its medieval architecture and historical significance.

Borberg resided in Viborg after marrying psychiatrist Allan Borberg in 1939.

The city’s blend of tradition and modernity, coupled with her husband’s profession, may have deepened her insights into human psychology and societal norms.

Above: Viborg, Denmark

After her husband’s death in 1979, she moved to Fjaltring, a village on the North Sea.

A small coastal village in West Jutland, Fjaltring is known for its serene landscapes and close-knit community.

After her husband’s death in 1979, Borberg moved to Fjaltring.

The tranquility and isolation of this village likely offered her a reflective environment, influencing the themes of freedom and individuality in her later works.

Above: Fjatring, Denmark

Borberg made her debut as a writer with Vindebroen in 1968 at the age of almost 51.

Borberg made her literary debut with this collection of short stories.

The narratives explore themes of personal liberation, the courage to break societal norms, and the pursuit of self-realization.

The title, translating to “The Drawbridge,” metaphorically represents transitions and the crossing of personal boundaries.

Her second novel, Orange, published in 1972, was translated by Ursula Gunsilius and published in 1975 by the East German publisher Volk und Welt for their own book series Spektrum.

This novel tells the story of a woman who abandons her conventional life in search of personal freedom.

She leaves behind her banker husband and domestic routines to embark on a spontaneous and unstructured journey.

Throughout her quest, she encounters various societal constraints, highlighting the complexities of seeking autonomy within established social frameworks.

The narrative blends grotesque and realistic elements to critique societal norms and the concept of freedom.

She focused her work on women and their fates.

She published Eline Bessers læretid (Eline Besser’s Apprenticeship)(1976) and Det bedste og det værste, Eline Besser til det sidste (The best and the worst: Eline Besser to the last)(1977), two historical novels about maids living in Denmark at the turn of the century.

Her works primarily reflect Danish society and experiences.

Above: Flag of Denmark

There is no known evidence that she wrote about Romanshorn.

Located on the southern shore of Lake Constance in Switzerland, Romanshorn is a picturesque town known for its harbor and scenic beauty.

While Borberg was born here, she left at a young age.

There is no evidence to suggest that Romanshorn directly influenced her literary works.

Above: Romanshorn

During Jytte Borberg’s lifetime (1917–2007), both Denmark and Switzerland underwent significant social transformations, particularly regarding women’s rights, societal expectations, and personal freedom.

Above: Coat of arms of Denmark

However, the pace and nature of these changes varied between the two countries.

Above: Coat of arms of Switzerland

Denmark was generally ahead of Switzerland in terms of gender equality and personal freedoms for women.

Denmark granted women the right to vote and run for office in 1915, two years before Borberg was born.

By the 1960s and 1970s, Denmark was at the forefront of women’s liberation movements, with strong advocacy for gender equality, sexual freedom, and economic independence.

The welfare state model provided extensive support for women, including paid maternity leave, subsidized childcare and access to education and employment.

Danish society, particularly from the 1960s onwards, saw greater acceptance of individualism, allowing women more personal freedom in choosing careers, relationships, and lifestyles.

Divorce became more socially accepted, and by 1989, Denmark became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex partnerships, signaling a broad cultural openness.

Above: (in red) Denmark

Switzerland did not grant women the right to vote at the federal level until 1971, making it one of the last European countries to do so.

Some cantons resisted further, with Appenzell Innerrhoden only allowing women to vote in 1991.

The Catholic influence in many Swiss regions led to conservative attitudes toward gender roles, family structures, and personal freedoms for women.

Swiss women had limited legal rights in marriage until the 1980s— for example, a married woman needed her husband’s permission to work until 1988.

Traditional expectations persisted longer, particularly in rural areas, where women were still expected to prioritize family and household duties over professional ambitions.

Above: (in red) Switzerland

Abortion was illegal until 2002, while Denmark legalized it in 1973, reflecting a stark contrast in reproductive rights.

In Denmark, personal freedom was increasingly valued from the 1960s onward, with a focus on individual choice, sexual liberation, and breaking traditional norms.

Danish women were encouraged to pursue careers, education, and independence, facilitated by social welfare programs.

Above: Danish women

In Switzerland, personal freedom was more constrained by traditional values and legal structures, especially for women.

The balance between personal freedom and societal obligation leaned more toward duty, particularly within marriage and family roles, until reforms in the late 20th century.

Above: Swiss women

Borberg’s novels, particularly Orange and Vindebroen, explore themes of women breaking free from societal norms and struggling for self-identity.

Above: Jytte Borberg’s Nældefeber (Hives)(1970)

Given the contrast between Denmark’s progressive stance and Switzerland’s conservative traditions, her experiences in Denmark likely nurtured her feminist perspectives and influenced her depictions of women challenging traditional roles.

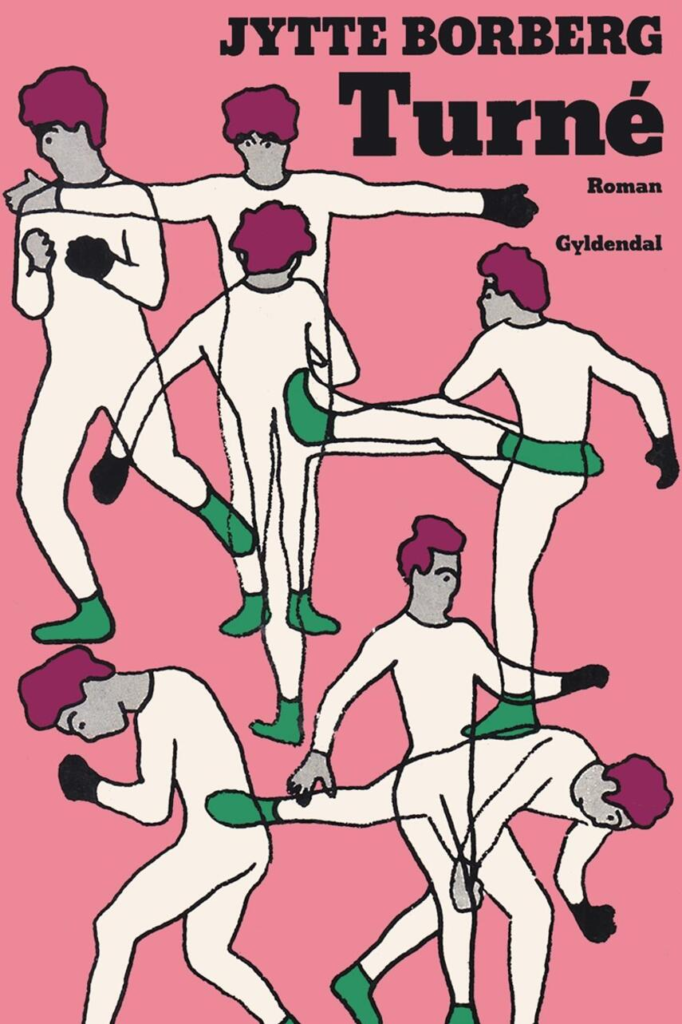

Above: Jytte Borberg’s Turné (Tour)(1974)

Had she remained in Switzerland, her works might have faced stronger resistance or taken longer to gain acceptance.

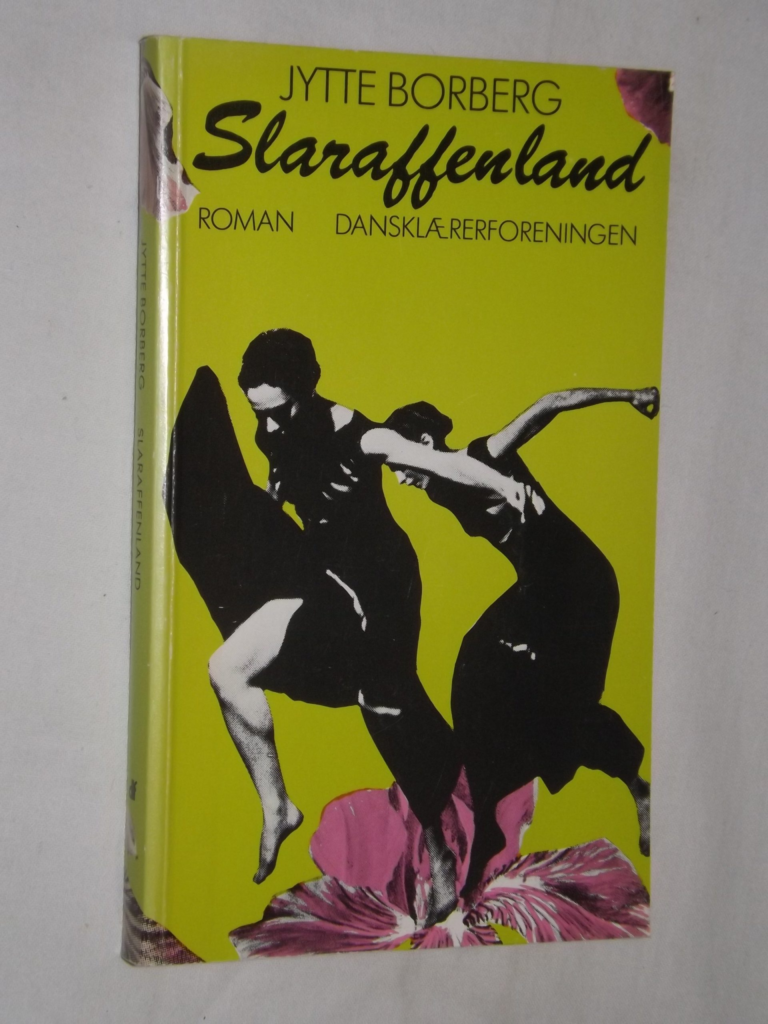

Above: Jytte Borberg’s Slaraffenland (1982)

Leaving Romanshorn may have been to her advantage.

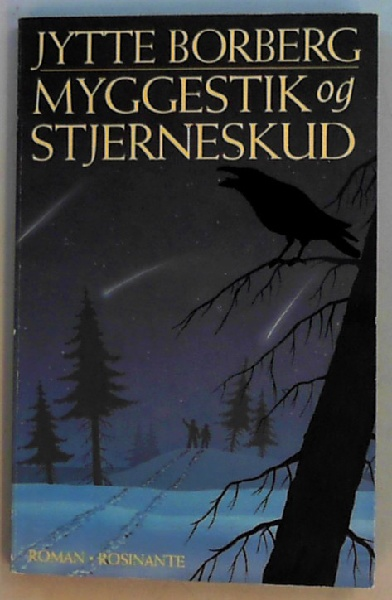

Above: Jytte Borberg’s Myggestik og Stjerneskud (Mosquito bites and shooting stars)(1990)

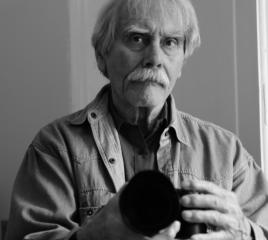

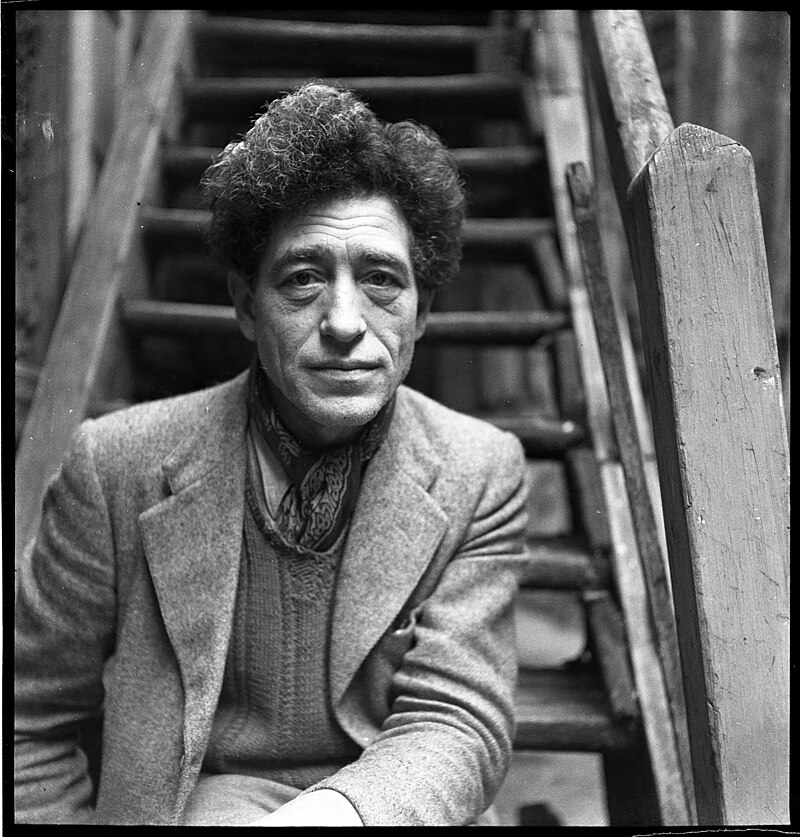

Jürg Schoop (1934 – 2024) was a Swiss artist.

He created his collages with brochures.

He coaxed his music from a sampler.

He found his paintings on railway carriages, near a dung heap, or in a well filled with floating leaves and blossoms.

What Jürg Schoop created became art, his life became his work.

His art remains immortal.

Above: Jürg Schoop

Born in 1934 in St. Gallen and raised in Romanshorn, Jürg Schoop’s ambition from a young age wasn’t to make as much money as possible, but to change the world.

Due to his “own horrific school experience“, he didn’t attend teacher training college like other artistically gifted people in the provinces.

He trained as a window dresser, bought works of world literature by the kilo from a scrap dealer, and read standard works of psychiatry “to learn more about humanity and his own madness“.

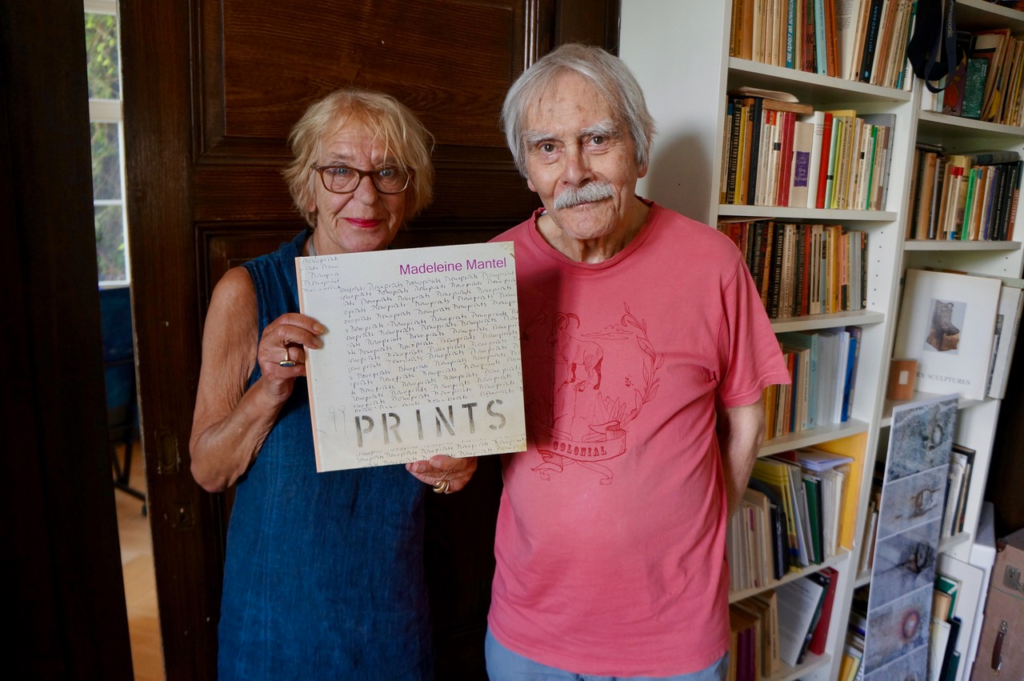

Above: One of his last works: Madeleine Mantel and Jürg Schoop present their collaborative work (2018)

Schoop attended the graphic design class at the St. Gallen Trade School and the Romanshorn Business School.

Above: Gewerbeschule (trade school) St. Gallen

Above: Cantonschule Romanshorn

He drew, wrote stories, a screenplay, and a radio play while still at school.

At 17, he began painting as a self-taught artist under the influence of Surrealism and Expressionism.

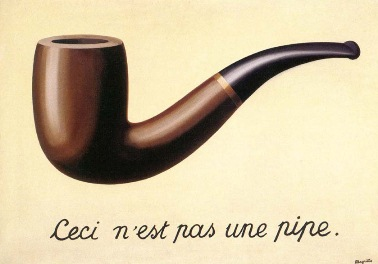

Above: Surrealist René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (1929)

He studied art, literature, psychology, psychoanalysis, philosophy, photography and film.

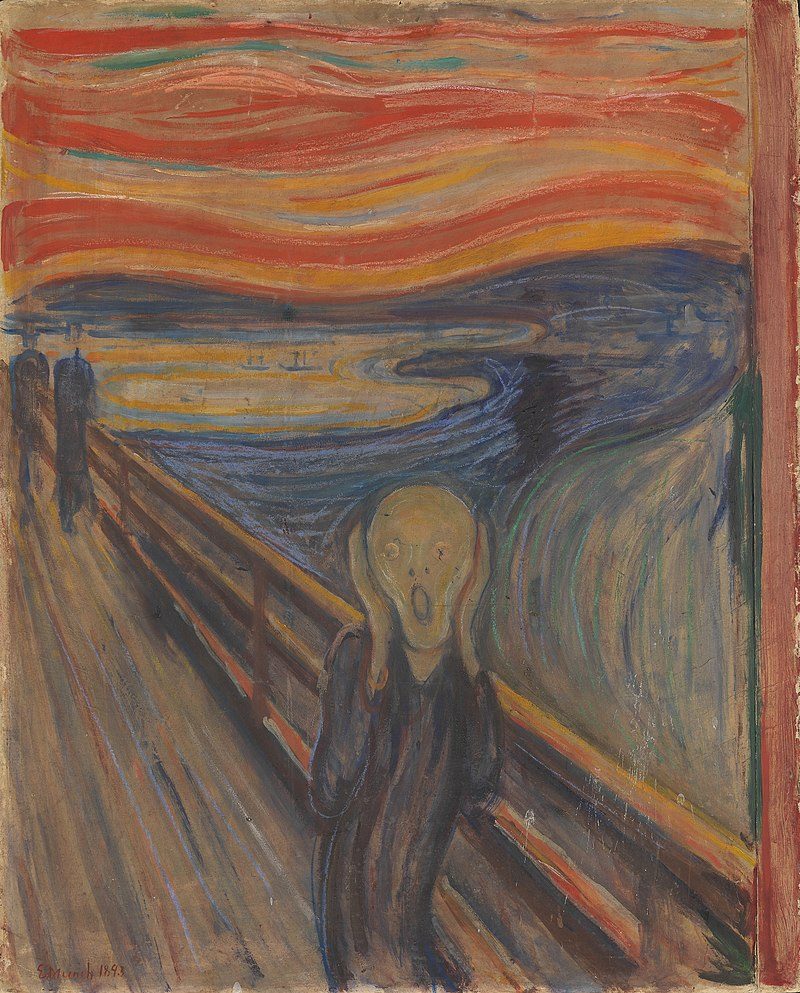

Above: Expressionist Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893)

From 1955 onward, Jürg Schoop worked as a freelance graphic designer and decorator in Romanshorn, serving the burgeoning consumer society, which he rejected.

However, he viewed this only as a “sideline activity“.

Above: Jürg Schoop

The existentialist’s commitment was to clou – a forerunner of the 1968 movement – which he founded with colleagues in 1956.

Above: Jürg Schoop

The “monthly magazine for young people” wrote about absurd theater, cool jazz and masturbation, printed poetry by the universal artist Jean Cocteau, provided a platform for anti-nuclear activists, and fought against rearmament during the most grim Cold War.

Above: French writer/filmmaker Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963)

There is no question that it was orchestrated by Moscow according to Swiss state security.

Above: Flag of the Soviet Union (1922 – 1991)

After separating from his wife, the artist Vera Schoop-Kahr, Jürg Schoop moved to Zürich in 1972.

He earned his living as a framer, forestry assistant, and warehouse clerk, while also attending ten semesters of clinical psychology, leading self-awareness groups, and running a bookstore.

Above: Zürich, Switzerland

He attended a specialist course at the University of Zürich (Clinical Psychology, Ethno-Psychology).

Above: Logo of the University of Zürich

Schoop received basic training in psychodrama at the Moreno Institute.

Above: Jacob L. Moreno ancestral home, Pleven, Bulgaria

Jacob Levy Moreno (né Iacob Levy) (1889 – 1974) was a Romanian-American psychiatrist, psychosociologist and educator, the founder of psychodrama, and the foremost pioneer of group psychotherapy.

During his lifetime, he was recognized as one of the leading social scientists.

Above: Romanian American psychotherapist Jacob Levy Moreno

Psychodrama is an action method, often used as a psychotherapy, in which clients use spontaneous dramatization, role playing, and dramatic self-presentation to investigate and gain insight into their lives.

Developed by Jacob L. Moreno and his wife Zerka Toeman Moreno, psychodrama includes elements of theater, often conducted on a stage, or a space that serves as a stage area, where props can be used.

Above: Dutch American psychotherapist Zerka T. Moreno (1917 – 2016)

A psychodrama therapy group, under the direction of a licensed psychodramatist, reenacts real-life, past situations (or inner mental processes), acting them out in present time.

Participants then have the opportunity to evaluate their behavior, reflect on how the past incident is getting played out in the present and more deeply understand particular situations in their lives.

Psychodrama offers a creative way for an individual or group to explore and solve personal problems.

It may be used in a variety of clinical and community-based settings in which other group members (audience) are invited to become therapeutic agents (stand-ins) to populate the scene of one client.

Besides benefits to the designated client, “side benefits” may accrue to other group members, as they make relevant connections and insights to their own lives from the psychodrama of another.

A psychodrama is best conducted and produced by a person trained in the method, called a psychodrama director.

In a session of psychodrama, one client of the group becomes the protagonist, and focuses on a particular, personal, emotionally problematic situation to enact on stage.

A variety of scenes may be enacted, depicting, for example, memories of specific happenings in the client’s past, unfinished situations, inner dramas, fantasies, dreams, preparations for future risk-taking situations, or unrehearsed expressions of mental states in the here and now.

These scenes either approximate real-life situations or are externalizations of inner mental processes.

Other members of the group may become auxiliaries and support the protagonist by playing other significant roles in the scene or they may step in as a “double” who plays the role of the protagonist.

A core tenet of psychodrama is Moreno’s theory of “spontaneity-creativity“.

Moreno believed that the best way for an individual to respond creatively to a situation is through spontaneity, that is, through a readiness to improvise and respond in the moment.

By encouraging an individual to address a problem in a creative way, reacting spontaneously and based on impulse, they may begin to discover new solutions to problems in their lives and learn new roles they can inhabit within it.

Moreno’s focus on spontaneous action within the psychodrama was developed in his Theatre of Spontaneity, which he directed in Vienna in the early 1920s.

Above: Stegreitheater (Theatre of Spontaneity), Vienna, Austria

Disenchanted with the stagnancy he observed in conventional, scripted theatre, he found himself interested in the spontaneity required in improvisational work.

He founded an improvisational troupe in the 1920s.

This work in the theatre impacted the development of his psychodramatic theory.

The performances were free to the public.

Their goal was to maximize audience participation.

“The dramatic material was suggested by the audience or developed from the actresses’ own ideas.”

The “living newspaper” technique meant that the performances were based on current events, addressing the conflicts they provoked, exploring the motivations of the participants, and projecting the final resolutions of the dramatized stories.

“Their main task was to revolutionize the theater” and “to abolish the playwright and the written play”.

JL Moreno wrote in his autobiography:

“The key to improvisational theatre was the involvement of the audience, so that actors and spectators became one.

And the actress/spectator were to be the sole creators.

Everything was to be improvised:

The play, the motif, the plot, the conflict, and its resolution.

Impromptu theatre was much more than a dramatic adventure.

I believe we were among the first to experiment with multimedia ‘happenings’.

We had an improvisational orchestra that played at all the performances.

We also had an artist who made sketches during the dramatization.

There was also a lot of experimentation with lighting effects.

The lighting technician was to work as spontaneously as the musicians and actors, to respond to and enhance the theatrical action.“

The improvisational theater quickly became a popular meeting place for artists and intellectuals.

“The theater was always crowded.

Up to 40 people could fit in the room.”

The experiments in the Theatre of Spontaneity inspired J.L. Moreno to closely observe the therapeutic effect of certain roles on the actresses’ private lives.

This gave rise to the Theatre of Catharsis, a precursor to psychodrama, which J.L. Moreno developed after his emigration to the USA in 1925.

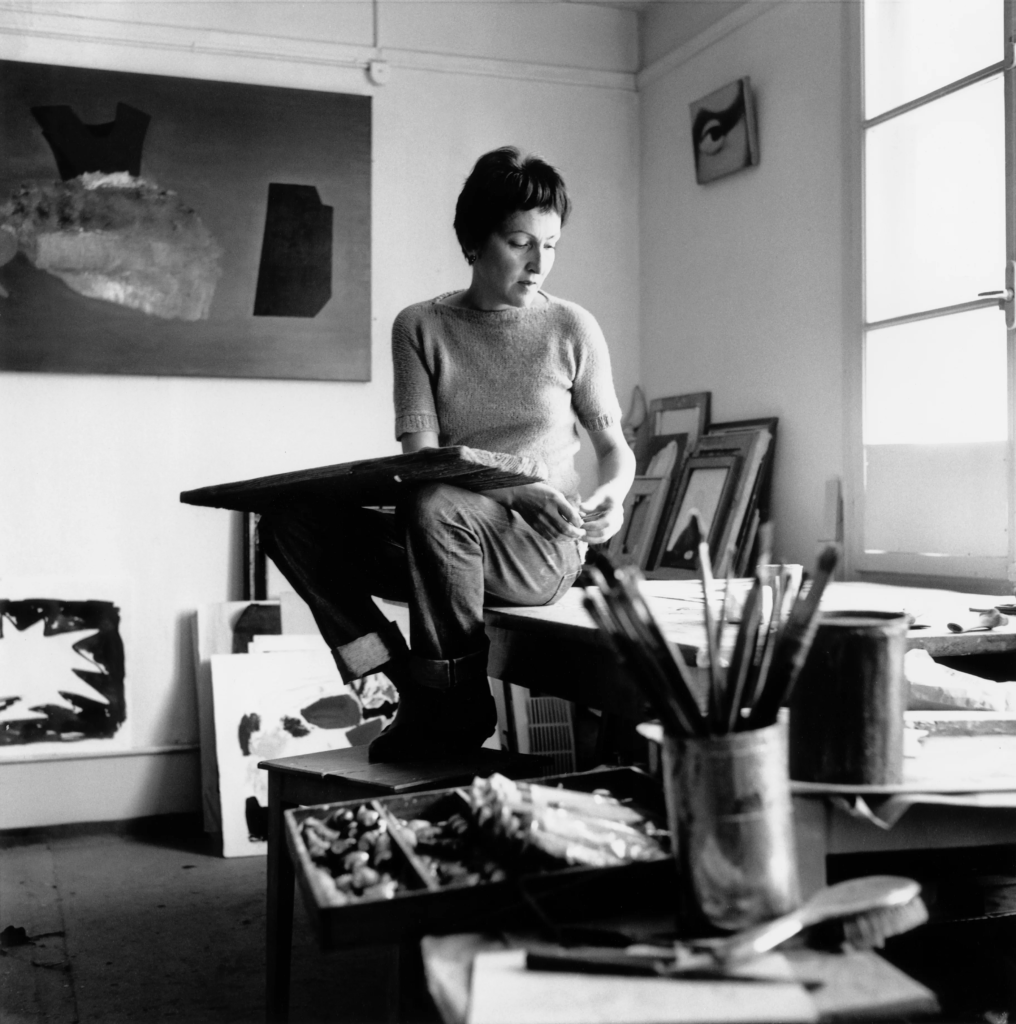

Schoop led creative and self-awareness groups and taught painting, photography, and video courses at various institutions, including those specifically for people with intellectual disabilities, until the 1980s.

Above: Jürg Schoop, 128 (1971)

Because of his critical attitude toward the art world, he was unable to assert himself nationally, so, “despite urgent warnings to others and himself“, he returned to Thurgau with his second partner in 1983.

Above: Flag of Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

He lived with his second partner, the educator Gerti Wülser, for 27 years in Fahrhof near Neunforn, a “picture-book idyll on the Thur“, and later in Kreuzlingen.

Above: Fahrhof, Neunform, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

As a “man who turned everything into art“, Schoop expressed himself in many different genres throughout his life, including philosophical texts, electronic sound experiments and painting.

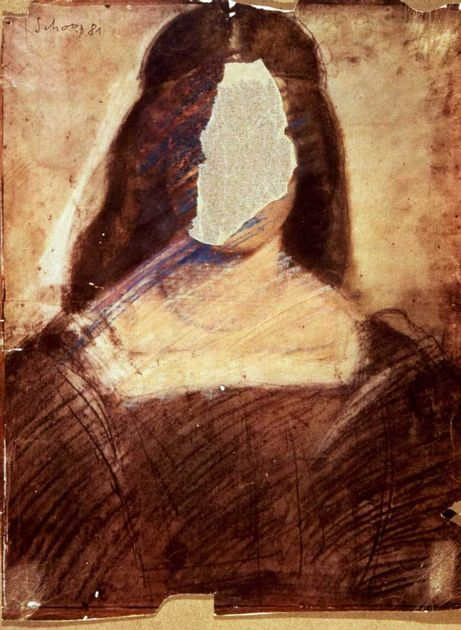

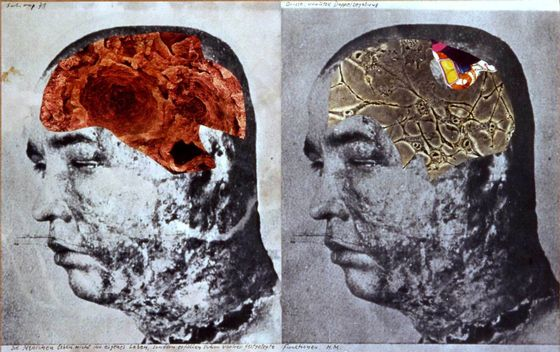

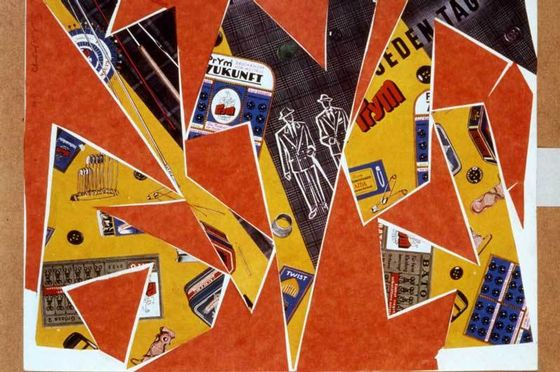

Above: Jürg Schoop, Untitled (1981)

Above all, however, he created collages from newspaper clippings, poster tear-outs, and packaging remnants and captured his images with his camera, for example, of leaves and blossoms floating in a fountain.

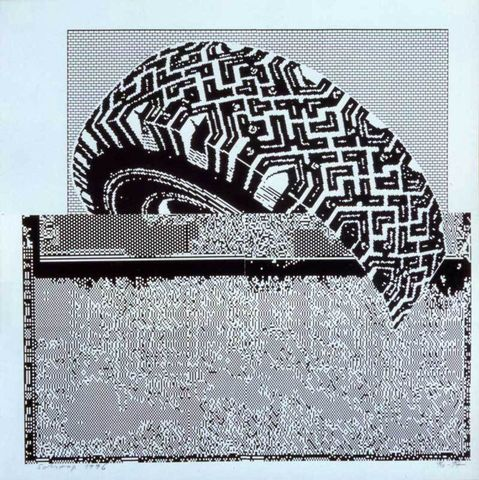

Above: Jürg Schoop, Collage on Paper

The Thurgau Cantonal Art Museum exhibited his paintings in 1985 and his collages in 1998.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Great, Useless Dual Talent (1971)

The Canton of Thurgau awarded him its Culture Prize in 1998.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Untitled (1956)

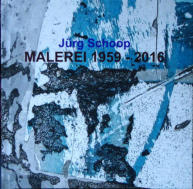

Jürg Schoop’s work is presented in a 2008 publication by the cantonal cultural foundation and documented on his personal website.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Photograph

Beyond the Canton, Jürg Schoop failed to receive the recognition he deserved because he rejected the art world, which measures significance by auction prices.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Photograph

His family is therefore wondering how long his diverse work will continue to live on after he was forced to give up his battle with numerous ailments on Easter Sunday 2024.

For all those close to him, the answer is clear:

Jürg Schoop continues to teach us how to see this world and another.

Above: From the Jürg Schoop Archives

The phrase “He turned everything into art.” suggests a person who perceives the world through a creative lens, transforming the ordinary into something meaningful, expressive, or beautiful.

This could be interpreted in several ways:

Artistic Perspective

He sees art in everything, whether in nature, daily life, or mundane objects, and finds ways to express it creatively.

Creative Living

His entire existence is an act of artistry, whether through the way he speaks, moves, or engages with others.

Transcending the Ordinary

He elevates even the most mundane aspects of life, imbuing them with meaning, emotion, or aesthetic value.

Philosophical Outlook

He believes that life itself is a canvas, and every experience, whether joyful or painful, can be shaped into something profound.

To turn everything into art, as Rainer Maria Rilke might suggest in Letters to a Young Poet, a man must cultivate a deep awareness of life — seeing, feeling, and experiencing the world with an intensity that transforms the mundane into something profound.

Rilke urges young poets to go inward and observe the world not just with their eyes, but with their entire being.

To turn everything into art, one must:

- Pay attention to the smallest details—the way light shifts through a window, the sound of distant laughter, the scent of rain on stone.

- See the beauty in the unremarkable, recognizing that every moment holds depth if truly observed.

- Practice solitude — not as isolation, but as a space for deep thought, where the world reveals its subtleties.

Rilke wrote that even sadness and suffering are gifts to be embraced.

A man who turns everything into art must:

- Transform pain into creation — letting grief and joy shape his work, whether through writing, music, painting, or even the way he moves through life.

- View struggles as material for self-growth and artistic expression, rather than obstacles to be avoided.

Art is not only found in grand gestures.

It resides in the ordinary.

One can:

- Approach simple tasks with artistry — the way he prepares a meal, writes a letter, or greets a stranger can be infused with grace and intention.

- Create rituals — whether it is the way he drinks coffee, takes a daily walk, or reflects on the day’s experiences — as a means of elevating life to an art form.

A man can turn everything into art not only through traditional artistic pursuits but through his actions and how he carries himself:

- The way he speaks, the rhythm of his voice, the elegance of his handwriting — each becomes an art form.

- His work, no matter how practical, can be done with craftsmanship and devotion, making even routine labor a creative act.

Rilke believed love was not possession but a witnessing of another’s growth.

A man who turns everything into art must:

- Love without clinging, allowing space for beauty to emerge naturally.

- Be fully present in every interaction, making relationships themselves works of art.

Rilke advised the young poet to write only if he must — if it is as necessary as breathing.

To turn everything into art:

- Write about the unnoticed, the overlooked — give voice to moments that would otherwise fade into obscurity.

- Let writing be a conversation with the self, not a pursuit of fame or validation.

Beyond Rilke, one might turn everything into art through:

- Zen practice, where mindfulness turns each moment into an artistic act.

- The philosophy of wabi-sabi, embracing imperfection and fleeting beauty

- Baudelaire’s flâneur, wandering the world as a poetic observer of life.

Zen is a fascinating practice and philosophy, one that weaves together simplicity, mindfulness, and deep insight into the nature of existence.

At its heart, Zen is about direct experience and living in the present moment, untethered by the distractions of the past or future.

It is more about practice than theory, more about being than intellectualizing.

Zen originated in China as Chan Buddhism around the 6th century and was later brought to Japan, where it evolved into the form most people recognize today.

Its philosophy is heavily influenced by Taoism, which emphasizes harmony with the natural world, and Buddhism, particularly its focus on emptiness (shunyata) and the non-self (anatta).

The word “Zen” itself comes from the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese word “Chan“, which means meditation.

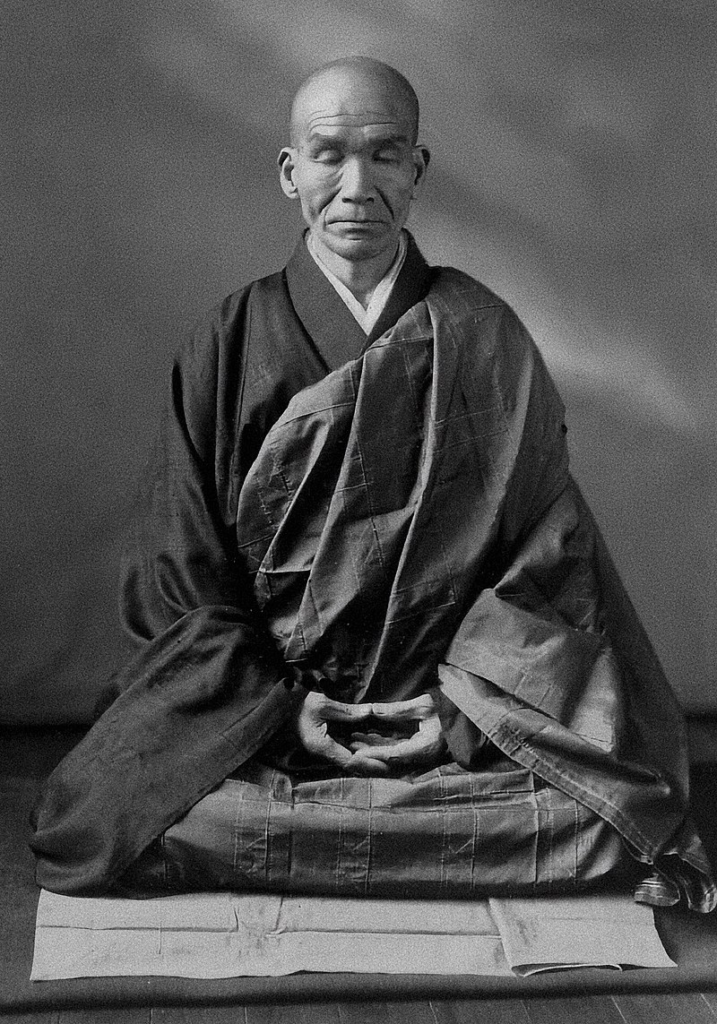

Zazen (Sitting Meditation):

The cornerstone of Zen practice is zazen, which means simply sitting meditation.

This is not a meditation for achieving a particular goal or state of mind, but rather an act of being fully present with whatever arises.

One sits in a formal posture, breathing deeply and calmly, observing the thoughts and sensations that arise without attachment or judgment.

Over time, through this practice, the practitioner learns to transcend the constant chatter of the mind and experience life with a sense of direct clarity.

Koans (Paradoxical Questions):

Zen is also known for the use of koans, which are paradoxical riddles or statements that defy logical thought and force the mind to confront its own limitations.

An example is the famous question:

“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

The point of a koan is not to answer it logically, but to break free from conventional thinking and awaken to a deeper, direct experience of reality.

The Mind of a Beginner:

A Zen approach to life encourages a beginner’s mind — a state where one is open, eager, and free of preconceived notions.

When we approach the world with a beginner’s mind, we see things as if for the first time, untouched by expectations or judgments.

This aligns with the Zen principle of “not-knowing,” where we let go of the need to label or categorize things, and simply experience them.

Simplicity and Emptiness:

Zen emphasizes simplicity and minimalism, both in daily life and in art.

The idea is to clear away excess and focus on what is essential.

In a Zen garden, for example, you will find carefully arranged rocks, sand, and plants — each element is significant, and the space is left open and uncluttered, allowing the mind to rest and reflect.

Similarly, Zen art and poetry (like haiku) are often simple, evoking profound meanings with few words or brush strokes.

Mindfulness in Daily Life:

Zen teaches that every moment is an opportunity for mindfulness.

Whether you are drinking tea, walking, or sweeping the floor, every action can be a practice of full engagement.

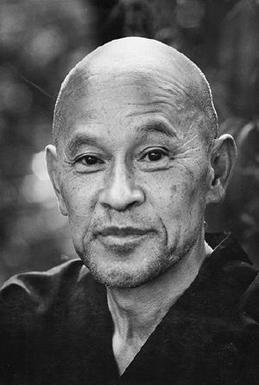

The Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki famously said:

“When you are doing something, just do it.”

This is about being fully present in whatever you are doing, without distraction or mind-wandering.

Above: Japanese monk Shunryu Suzuki (1904 – 1971)

At its core, Zen is about awakening — a realization of the true nature of reality.

Zen teaches that all things are interconnected, and the boundaries we often perceive between ourselves and the world around us are illusory.

When we drop our attachments, our judgments, and our fixed ideas, we come into direct contact with the world as it is, in its raw beauty and impermanence.

Zen also emphasizes that enlightenment (satori) is not something to be achieved at some distant point in the future, but something to be experienced in the present moment.

It is less about striving and more about letting go of the habitual patterns of thought and action that keep us trapped in cycles of dissatisfaction.

Zen is a paradoxical way of life:

It teaches that we must do nothing to achieve enlightenment, yet the practice requires a disciplined commitment to meditation and mindfulness.

The Zen saying, “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” reflects this paradox:

Enlightenment is not about escaping life but embracing it more fully.

Perhaps the simplest way to understand Zen is as a philosophy of life rather than a set of specific religious beliefs or rituals.

Zen does not ask us to look for meaning in the future or the past, but to embrace the present moment, where everything already is.

Zen is about living authentically, in direct contact with the world and the present, without the need for explanation or validation.

The beauty of Zen lies in its ability to help us reconnect with the world in the most direct and immediate way, allowing us to see the extraordinary in the ordinary.

If you were to practice Zen, it might look like this:

Noticing the world with the eyes of a beginner, experiencing each moment fully and without judgment — whether in the act of writing, walking, or simply sitting.

It would be about embracing the imperfections of life, finding beauty in its fleeting nature, and letting go of the compulsion to constantly seek or strive.

Through Zen, one might discover a profound peace in accepting what is rather than in what could be.

Wabi-sabi is a traditional Japanese aesthetic that celebrates the beauty in imperfection, transience, and the natural cycle of life.

Rooted in Zen Buddhist philosophy, it finds beauty in things that are weathered, worn, or unfinished, emphasizing humility, simplicity, and the passage of time.

Wabi-sabi reflects a worldview that accepts impermanence, encouraging a deep appreciation for life’s fleeting moments.

Key concepts:

Imperfection:

Wabi-sabi values flaws and asymmetry.

A chipped teacup or a crooked tree branch can be more beautiful than something perfectly symmetrical.

It speaks to the notion that imperfection is inherent in all things and should be celebrated rather than hidden.

Transience:

The philosophy celebrates the temporary nature of things.

Whether it’s the falling of leaves, the aging of a building, or the passing of a moment, wabi-sabi acknowledges that everything has a finite lifespan.

This transience can make an object or experience more precious, knowing it will eventually fade.

Simplicity and Subtlety:

Wabi-sabi encourages minimalism and a focus on the natural beauty of things without the need for embellishment.

It promotes an aesthetic that is unadorned, quiet, and unpretentious, allowing subtle details to stand out.

Nature:

Nature is central to wabi-sabi — its imperfections are viewed as beautiful because they reflect the natural process of life.

This could be a rustic wooden table, the wear of a stone pathway, or the elegant curve of a hand-crafted pottery bowl.

Wabi-sabi is not just an aesthetic but a philosophy for life.

It invites individuals to:

- Embrace the impermanent nature of their own experiences.

- Find beauty in life’s small, often overlooked moments.

- Appreciate the authenticity of things that aren’t perfect, embracing their unique stories and histories.

In creative work, wabi-sabi can be a guiding principle for producing art that celebrates imperfection, whether through writing, design, or craftsmanship.

It teaches that true beauty comes from embracing the flaws and transience that make things meaningful.

Wabi-sabi focuses on the appreciation of imperfection and the fleeting.

It is about finding beauty in the natural, the worn, and the incomplete.

In life, this philosophy teaches to embrace what is imperfect as inherently beautiful.

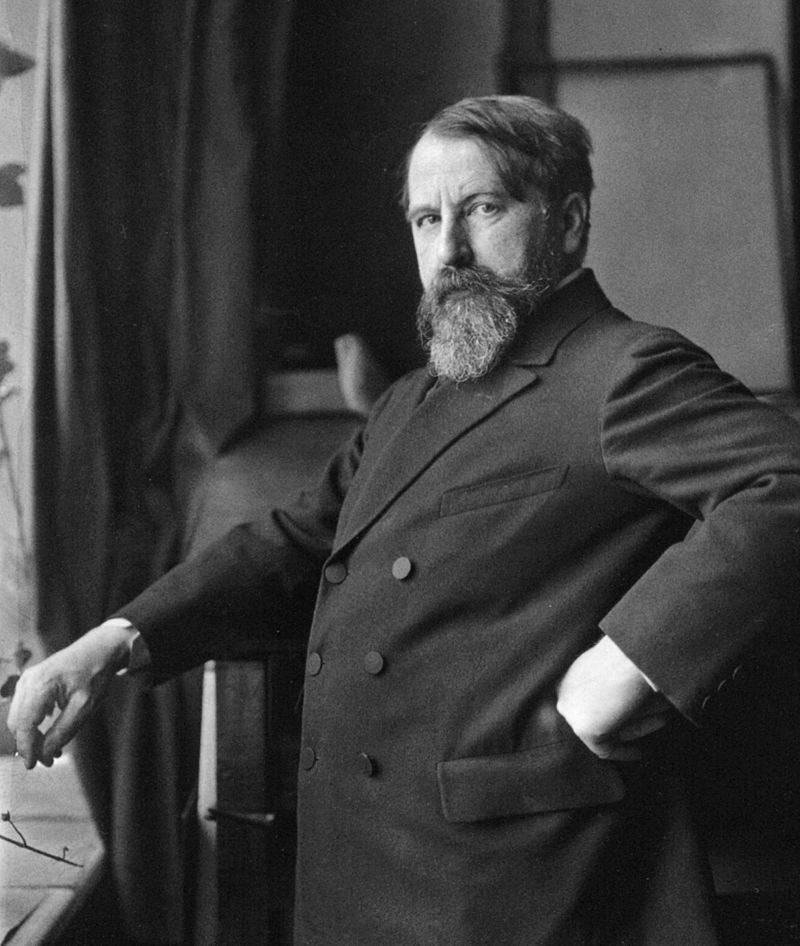

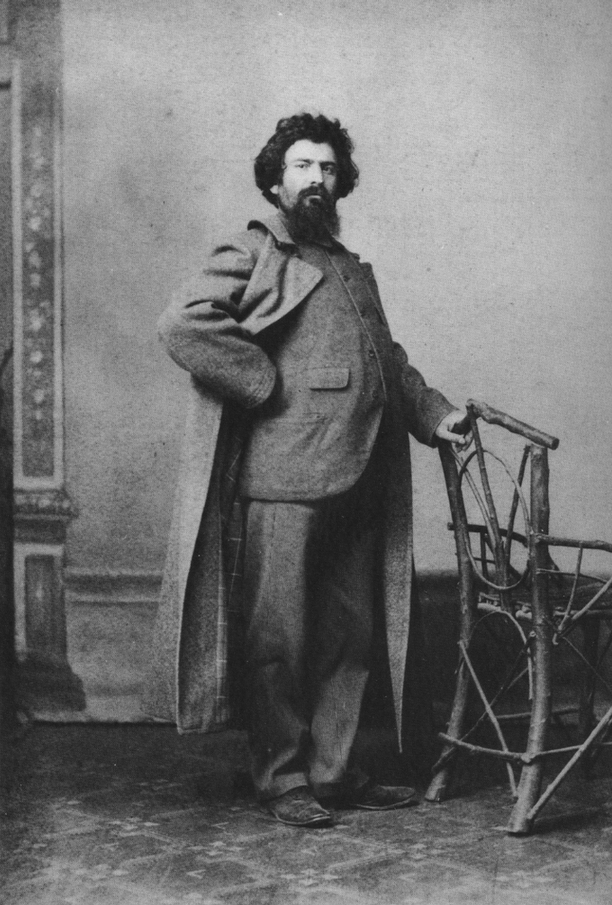

The concept of the flâneur comes from 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire and was further developed by later thinkers like Walter Benjamin.

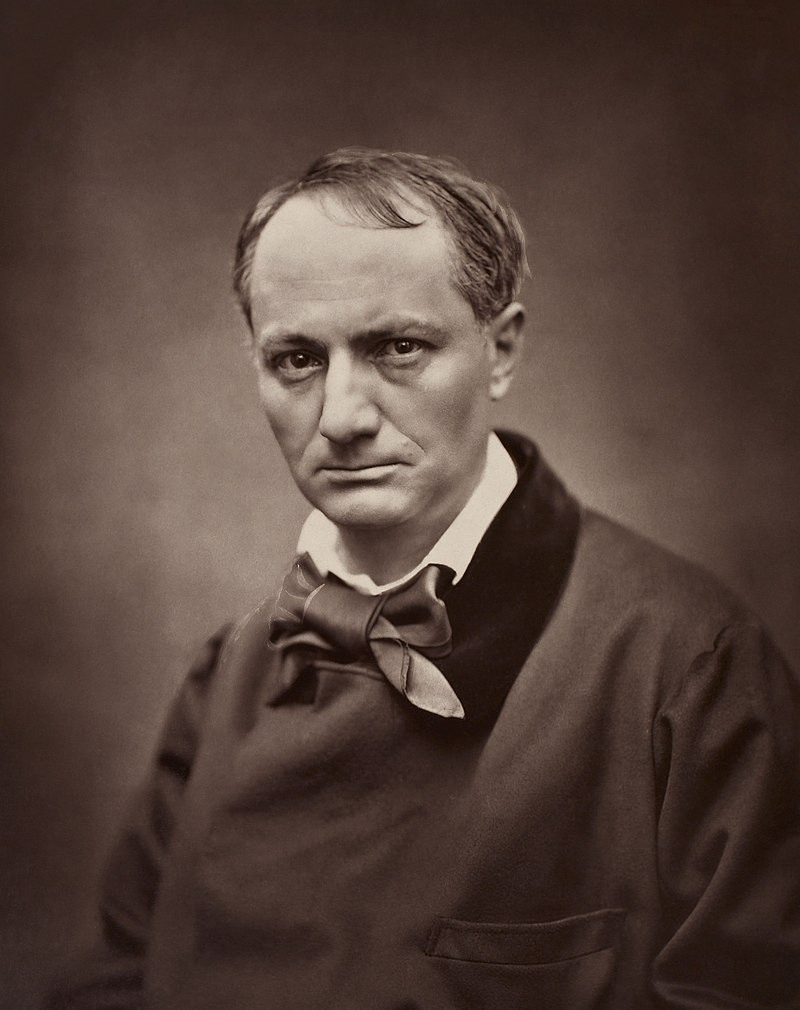

Above: French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867)

Above: German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892 – 1940)

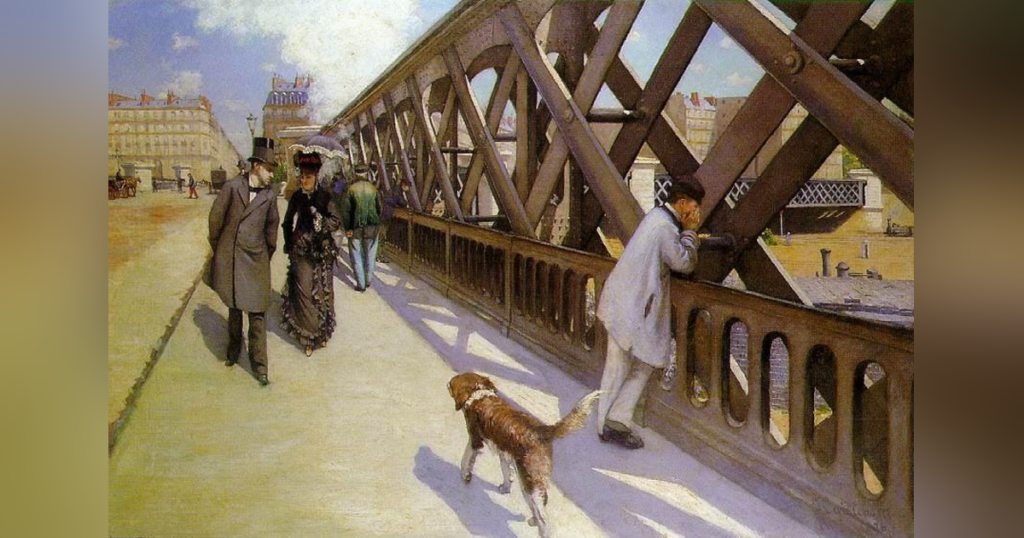

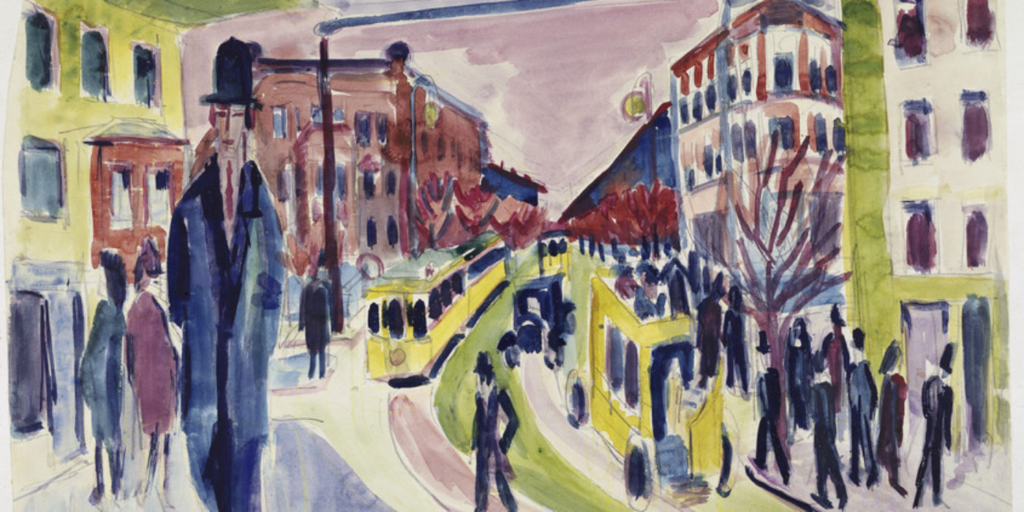

It describes a particular type of urban explorer — someone who strolls through the city, observing the life around them with an artistic and detached eye, yet deeply engaged with the environment.

Key concepts:

The Flâneur as Observer:

The flâneur is a passive yet intense observer, someone who walks through the urban landscape without a fixed destination.

They are not in a hurry, allowing themselves to take in the sights, sounds, and rhythms of the city.

This leisurely strolling becomes a way of experiencing life with a sense of detachment yet profound connection to the surroundings.

Urban Experience:

The flâneur is typically associated with the modern city, which Baudelaire viewed as a place of vibrant, chaotic life.

In the urban environment, the flâneur experiences the intersection of modernity, commerce and social life.

They notice things others might overlook, from the movement of people to the patterns of city architecture.

Detached Engagement:

The flâneur is not fully involved in the action.

Rather, they observe it from a distance, taking in the sensory details of urban life — shifting crowds, street vendors, the play of light on buildings.

The flâneur’s detachment allows them to notice things others miss, leading to a deeper understanding of the city’s rhythms and contradictions.

Artistic Perspective:

Baudelaire saw the flâneur as a kind of poet of the streets, one who can transform ordinary urban life into artistic observation.

They don’t engage with the world as participants, but as observers who extract beauty and meaning from everyday scenes.

For Baudelaire, the flâneur was an artistic archetype, and this concept continues to influence modern art and literature.

The flâneur’s way of moving through life — without a specific goal but with a keen eye for details — can offer insight into how to attune oneself to the world.

The idea encourages people to:

- Slow down and observe the world around them with a sense of wonder and curiosity.

- Extract poetry from the everyday, finding art in the details of life that others might ignore.

- Use detachment and observation to explore the deeper currents of modern existence, noticing the unseen and the unnoticed.

In writing, this philosophy could be applied by wandering through the streets of thought — capturing fleeting moments, impressions, and sensations — and creating meaning from what others might see as trivial or mundane.

The flâneur is more about active observation of the external world, particularly in an urban environment, and translating these observations into artistic expression.

The flâneur engages with the dynamic of the world around them but remains somewhat detached, reflecting on what they see and experience.

Together, these philosophies suggest that art can be found in both quiet reflection and keen observation, and both approaches encourage mindfulness — whether in the imperfections of objects or the vibrant flow of life.

Jürg Schoop’s work was deeply rooted in the idea of transforming the mundane into art, something that mirrors wabi-sabi’s appreciation of imperfection and transience.

His ability to turn seemingly ordinary or overlooked objects into art suggests a profound sensitivity to the beauty found in imperfection.

This aligns with the wabi-sabi philosophy, which values authenticity, simplicity, and the passage of time.

For example, Schoop was known for using everyday materials, often transforming the ordinary into something that spoke to deeper truths about human experience.

This is akin to wabi-sabi’s focus on the natural, the unfinished, and the flawed — which can be seen as a way of embracing life’s ephemeral nature and finding depth in what others might dismiss as insignificant or flawed.

In this sense, Schoop’s work speaks to the impermanence of all things and the beauty inherent in the imperfect.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Pieces of Paper

In November 2023, Jürg Schoop was able to show his final collage series, titled “Backside” at the Zecchinel Center in Tägerwilen.

Above: Zecchinsel Center, Tägerwil, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

He had forced himself to create this cycle despite his already advanced illness.

This exhibition became his final message, something he was well aware of.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Collage (1992)

He wrote:

“In general, I see the reason for this series in the confrontation with one’s own origins, the circumstances of life, which for everyone end in a new form of time – called eternity.“

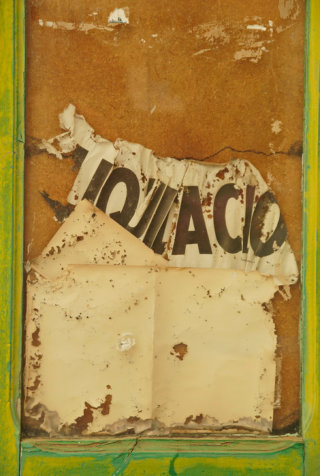

Above: Jürg Schoop, Window II

It’s no coincidence that he, born in 1934 and having begun his artistic work as a poet and painter at a young age, ultimately returned to collage.

Schoop’s collages were composed of found objects from our everyday culture:

Discarded items, newspaper clippings, torn-out posters, and packaging remnants.

Removed from their contexts, or rather, identified and selected with a keen eye, these leftover pieces came together to form new compositions and thus to acquire new associations and meanings.

The latter emerged as the result of the compositions.

In his last series, however, they followed a message.

What had previously been coincidence became intentional.

A piece of paper printed with dots, for example, was chosen to represent the theme of the “Tüpflischiesser” (a pun on the dots).

Clearly an insult to the audience.

A floating female figure, presumably from a perfume package, mutated into a “guardian angel” that God knows he could have used himself.

He inserted a photograph of his mother and grandmother into the work titled “My Own Past“.

He himself appears with his wife Gerti on a slide inserted into another collage.

Above: Dispersion auf Papier (1987)

Schoop wrote:

“My series is not intended to be understood as a list.

It is determined by coincidences in the basic material (always empty, worn-out boxes) and spontaneous suggestions of an aesthetic or intellectual nature.

These works are not intended to be seen as some kind of showcase or teaching piece.

If I admit to one intention, it is that everyone should feel inspired to explore their own backside — whether original, strange, interesting, or reprehensible.”

Above: Jürg Schoop, Dispersion auf Papier (1990)

Jürg Schoop’s artistic attitude is rooted in the 1950s, in existentialism, jazz, and tachism, in a distrust of any ideology, tyranny, and co-optation.

He was a jazz columnist, electronic pioneer, writer, and thinker.

He was always on the path of self-assertion in the face of cultural, religious, economic, and even social dominance, wherever and however it was observed.

He countered this overwhelming power with his art.

One might say that the further consumer-oriented society distanced itself from his stance, the more defiantly he became.

He didn’t conform to the currents of his time — including, and especially not, art — but he always engaged with them.

And precisely: the set pieces, packaging, and torn imagery, including those of advertising as reflections and backsides, were and became his true subject matter.

Above: Jürg Schoop

Kathrin Zellweger wrote:

“Jürg Schoop struggles with the label of being an artist.

He rejects any external definition.

Why should he call himself an artist, as if there were a life plan and his destiny behind it!

‘I am an existentialist.’

His mission is to be human.

Period.“

Schoop loved art as art and as a position.

As mentioned, he became increasingly critical and even hostile toward the art world.

Five artistic positions were presented, which, taken together, demonstrated how art had become self-perpetuating and thus its own fiction.

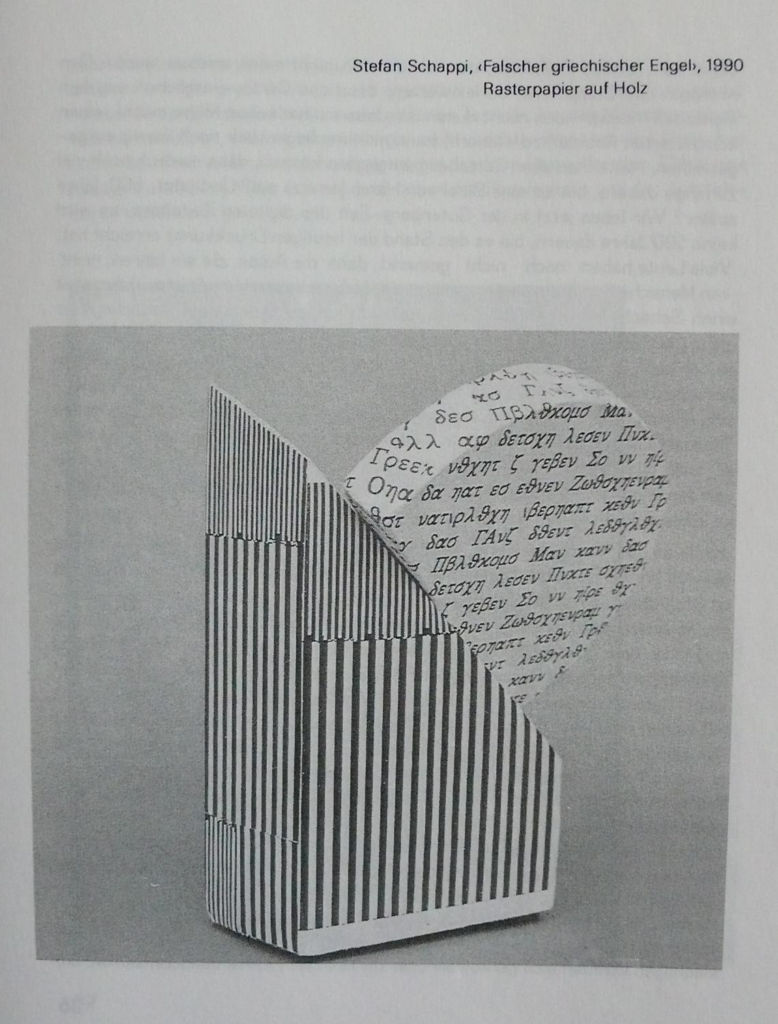

The works shown by Mara Donati, Stefan Schappi, Marco Hrubesch, and Rudi Tillug were all fakes.

The artists, their biographies, and their works — except for the artist himself — were invented.

Stefan Schappi’s object titled “False Greek Angel” was just as fictitious as his statement:

God is a computer.

During the opening, an accident occurred on Brückenstrasse in which a ballerina injured her knee and required emergency medical treatment.

He also staged this completely theatrically.

“You’ll see,” he said, “no one will notice, and if they do, no one will protest.”

He turned out to be right.

Above: Schoderbach, Bruckenstrasse, Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau

I am reminded of “The Turning Point” (1977) starring Shirley MacLaine and Anne Bancroft.

In the film, one of the characters, a promising young ballerina, gets into a car accident where a vehicle backs up and crushes her leg against another car, effectively ending her ballet career.

It’s a heartbreaking moment that highlights the fragility of a dancer’s future and the sacrifices they make.

Plot

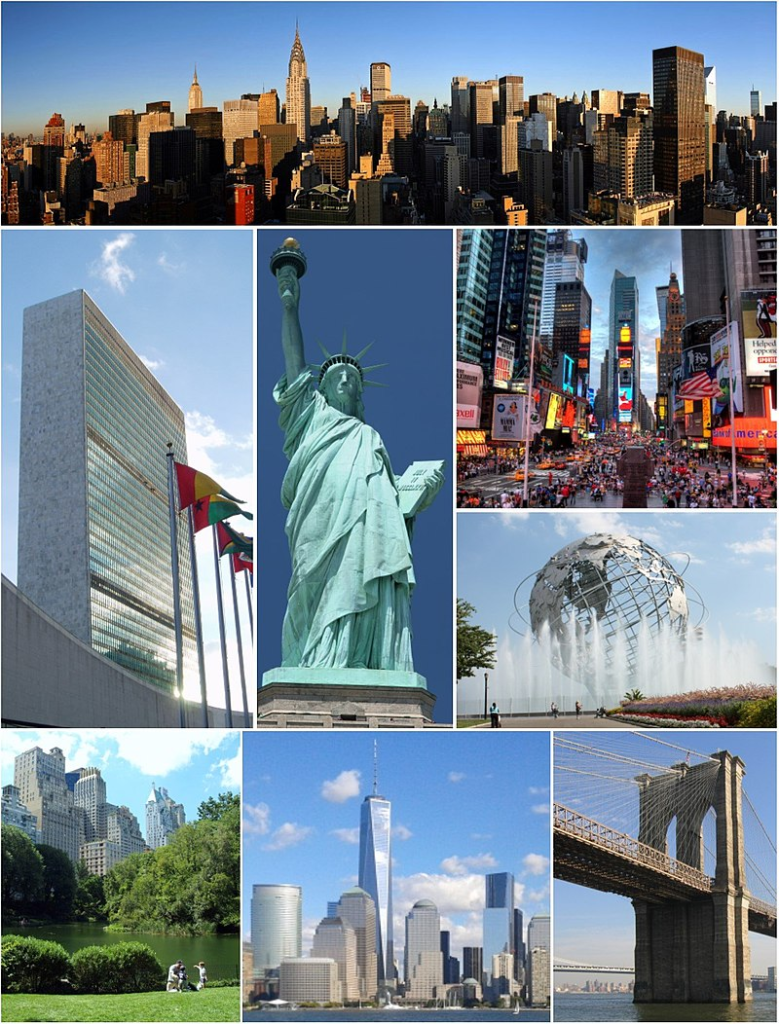

DeeDee Rodgers (Shirley MacLaine) leaves an eminent New York ballet company after becoming pregnant by Wayne (Tom Skerritt), another dancer in the company.

Above: American actress Shirley MacLaine

Above: American actor Tom Skerritt

They marry and later move to Oklahoma City to run a dance studio.

Above: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA

Emma Jacklin stays with the company and eventually becomes a prima ballerina and well-known figure in the ballet community.

Above: American actress Anne Bancroft (1931 – 2005)

While the company is on tour and performs a show in Oklahoma City, DeeDee and the family go to see the show and then have an after-party for the company at their home.

The reunion stirs up old memories and sets the plot into motion.

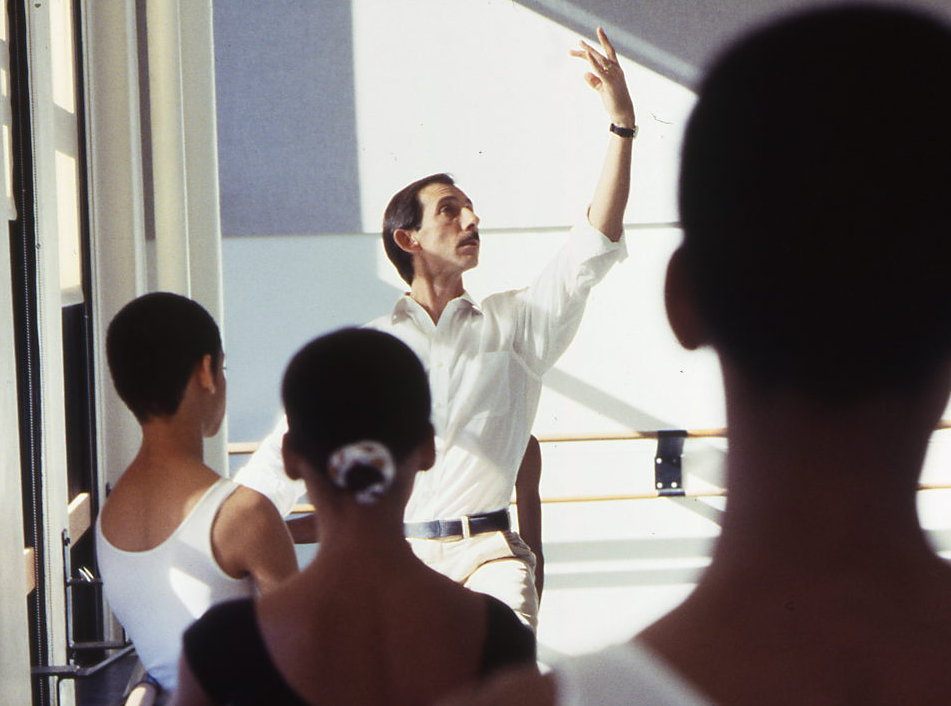

At the party, DeeDee’s daughter Emilia (Leslie Browne), an aspiring dancer who is also Emma’s goddaughter, is invited to take class with the company the following day.

Above: American ballerina Leslie Browne

Afterwards, Emilia is asked to join the company but she does not immediately accept the offer as she wants to think it over.

DeeDee and Wayne decide that DeeDee should go to New York with Emilia, who is rather shy and does not make friends as easily as her younger sister.

Above: Images of New York City, New York, USA

Meanwhile, their son, Ethan, gets a scholarship to the company’s summer program while Wayne and their other daughter stay in Oklahoma City.

Once in New York, they rent several rooms in Carnegie Hall with Madame Dakharova, a ballet coach.

Above: Carnegie Hall, New York City

Above: Russian ballerina Alexandra Danilova (1903 – 1997)

Emilia soon starts a relationship with a Russian dancer in the company, Yuri (Mikhail Baryshnikov).

Above: Latvian dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov

However, when she catches Yuri with another dancer, Caroline (Starr Danias), the broken-hearted Emilia gets drunk in a bar before a performance.

Above: Starr Danias, The Turning Point (1977)

Emma takes the situation at hand and cares for and helps Emilia complete the performance.

This angers DeeDee who, because of a brief affair with the former conductor of the company, has caused conflict between herself and Emilia.

Meanwhile, Emma argues with Arnold (Daniel Levans), the choreographer, about giving her a better role in his new ballet, which he refuses and leads Emma to suggest Emilia for the role instead.

Above: American dancer Daniel Levans (1954 – 2015)

DeeDee resents that Emma dotes on Emilia.

After all, DeeDee chose family life over her career while Emma chose not to have children and to excel as a ballerina.

DeeDee accuses Emma of telling her to get pregnant and have Wayne’s baby so Emma could play the lead in Anna Karenina.

Eventually, Emma and DeeDee get into a physical altercation on the rooftop of Carnegie Hall before finally settling their misunderstandings.

DeeDee admits her jealousy of Emma’s life.

Emma admits that she would have “done anything” to get the lead in Anna Karenina.

Because of her stunning performance in Arnold’s ballent, Emilia is given the lead in Sleeping Beauty alongside former love Yuri, and she and Yuri make up and agree to a professional partnership and nothing more.

DeeDee decides she is content with her life and the decision she made to leave professional ballet to have a family.

Emma accepts that her performing days are numbered, and she must embrace a different role within the company.

DeeDee and Emma step onto the stage and reminisce together.

A work by Schoop from 1990 is titled “My Heart Was So Green.”

It is an objet trouvé, a found object.

The object, made of papier-mâché with sprinkles, is indeed green and shaped like a heart.

Jürg Schoop didn’t make it, but rather found it.

Or invented it.

Above: Jürg Schoop, My heart was so green (1996)

One should not conclude from this that art is a nominalist position, according to which art is whatever someone defines as art.

Art is a work that arises from an artistic attitude and, if successful, is of fundamental importance.

It arises, as in Jürg Schoop’s work, from an inner necessity, be it the need to cope with one’s own limited and thrown-off existence.

You have to be truly naive to choose this as your life’s path and mission.

Jürg Schoop had this green heart and the strength to dedicate his life to art, no matter the cost.

Above: Jürg Schoop, Dispersion auf Papier (1965)

F. Ictitious (Interviewer):

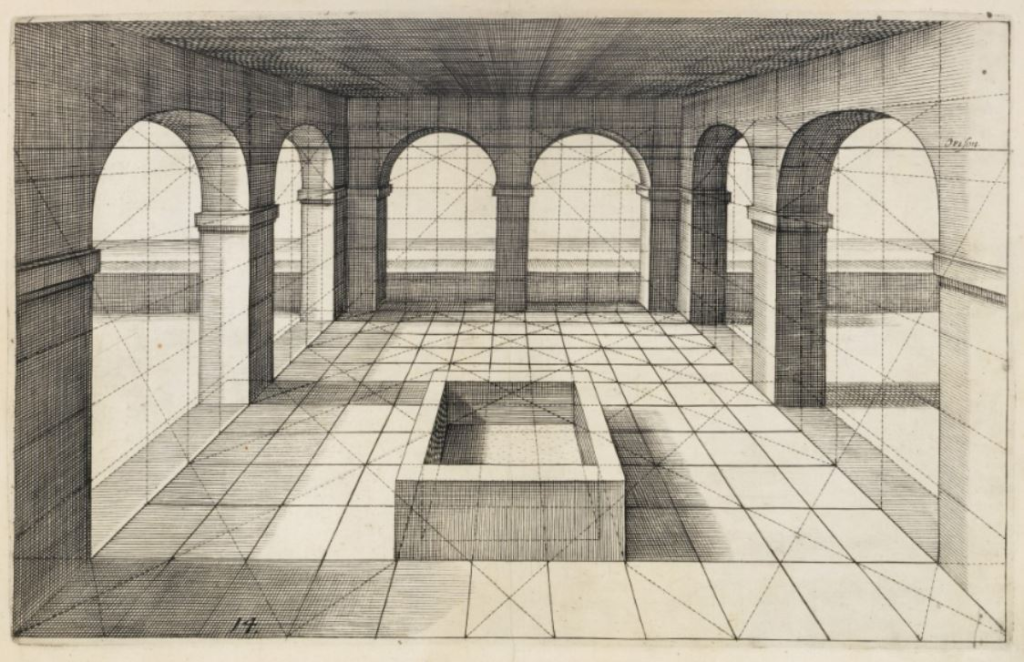

In 1970, during a lecture at the Rorschach Art Association, you stated that the artist’s task could no longer consist solely in producing paintings, sculptures, and the like, which are ultimately understood as tradable objects of aesthetic or ideological idiosyncrasy.

The contemporary dialogue between the artist and society, which previously took place in a specifically designated space, must encompass our entire survival and aim at all associated creativity.

A creative will is required that incorporates social realities, not reflexively, but in the sense of transformation.

In 50 years, you wrote, artists will build our cities, educate our children, organize our society.

A utopia?

Perhaps…

But a necessary one.

Well, this 50-year period you envisioned will soon be over.

Have realities changed in the way you thought they would?

Or at least developing in that direction?

J. Schoop:

The observations made at that time can probably be attributed to a youthful, anticipatory urge for change.

Behind that, one can also see an optimism that ignored social and political realities, something I have, of course, long since left behind.

Naturally, social change has also brought about new freedoms.

In 1970, for example, unmarried couples could only live together with disapproval — if at all.

If this is no longer an issue today, the reason is not that it reflects a new culture of coexistence.

People who are constantly busy earning as much money as possible are, logically, focusing their attention on that part of psychology that deals with consumer behavior.

Individuals who feel content and afford themselves so-called freedoms are better and more manageable consumers, whether in a couple’s room or a pampered family.

Individual freedom is actually an implanted illusion.

These same people have discovered, at least in the last 20 years, the sheer extent to which money can be amassed through art and culture.

Today, it is no longer just a small elite who is interested in art.

Speculators of all stripes are involved, dreaming of unimagined added value.

Thirty years ago, I imagined that there was probably nothing more beautiful and interesting for laundering money.

There would be no other option than to open art galleries with specifically developed artists.

The artists who bring in the big money are already made in one way or another.

What the Mafia needs isn’t the money, but a few people who know the most important interpreters, publishers, TV stations, and the most popular curators, as well as the best gallery locations.

(I think my crazy idea has already been caught up in reality.

Only the lowest ranks of the Mafia are stupid there.

The pizzeria business soon ran out of steam and is too easy to see through, except perhaps in Switzerland.

Art means bigger money.

If you compare the cultural offerings today with those of 50 years ago, you are immersed in a tsunami.

There’s no artist who doesn’t discover a new aspect to something, no singer who doesn’t possess a gifted, heart-winning voice, no dancer who reinterprets the stage, no writer who doesn’t write a sophisticated homage to life.

And they don’t appear individually.

They flood the country like waves.

Somewhat naively, one might think that culture has gained unexpected ground.

One involuntarily wonders who will be the leaders of the state if there are only creative people left.

Who pay little or no taxes.

No, I believe that most artists make no significant contribution to changing social conditions.

Astonishing ideas that give the impression of doing so serve primarily to organize recognition.

The will to create art, however capricious it may be, results in a socialized uniformity.

Artists should constantly reflect on how creativity might be defined in the present.

I see only the evisceration of modernity, called postmodernism, and the cultivation of one’s own narcissism, which is almost unavoidable today.

Above: Jürg Schoop

F. Ictitious (Interviewer):

Why aren’t those born in the first half of the last century happier with the current, ground-breaking development of culture and education?

Above: Jürg Schoop, Yaris II

J. Schoop:

Although we have nothing against popular culture and all its variations, a closer look tells us that society has not fundamentally transformed itself, as desired.

We are easily deceived by the sheer volume of what is on offer.

Of course, there are valuable cultural bearers and mediators among them, and reflection on the fringes of society is certainly noticeable, but that doesn’t indicate the direction.

Promoting amateurism alone would be inadvisable for those who possess the means to foster the cultural glut, if only for purely economic reasons.

Moreover, the nurturing mother of all economic things is image cultivation.

You know, the term “event culture” was missing from our vocabulary.

We couldn’t even imagine it:

Culture as a common leisure activity, a vaccine against boredom and permanent vulnerability.

Alongside the middle class who climb out of their homes and are easily seduced by what is on offer, it is primarily the younger generations who shape the largest mass events.

It is no longer a matter of recognizing that we are dealing with a slightly different culture, one whose taste is sometimes questionable.

When 8,000 people wave their illuminated cell phones to the beat of a second-rate, as loud as possible band, it’s certainly no longer about music.

We are attending a ritual event that developed from a new understanding of culture.

Can one have anything against rituals?

Alongside a merely hypertrophic event business that —economically speaking — has traditional roots, the changes, whether they are progressive or not, are also observable.

I advocate, however, that we consider all of this for the time being under the term of consumption — ritual of a new society or not.

A real upheaval, the beginnings of which we are now finding ourselves in, one that will also suggest entirely different concepts of culture, is present with digitalization, with the digital age, from which I have some completely unpessimistic hopes.

It will also elevate art to a new level.

Maybe I’m wrong again —

If capitalism succeeds in once again establishing, or rather expanding, its control over all human intelligence to increase money and power, then global darkness will reign.

As the saying goes:

Send brains from Heaven, not so much culture…

Above: Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest heaven – from Gustave Doré’s illustrations to the Divine Comedy

F. Ictitious (Interviewer):

Disillusioned, but you still consider the present a source of the future?

J. Schoop:

Nevermore unbroken than now, but of course I’ve noticed that even as an outsider, I’m still afflicted by the optimization and performance mentality and therefore a welcome target for neoliberalism.

But the next 30 to 50 years will be the most important in the history of humanity.

95% of the nonsense that humanity has cultivated for thousands of years will disappear, society will become more pragmatic and transparent, and promise to pave the way for justice.

F. Ictitious (Interviewer):

And new nonsense will emerge…

J. Schoop:

Possibly, but it will be of a completely different and therefore more conciliatory nature, I hope.

The bad thing is having to get used to the same nonsense over and over again.

I can’t dream about the future for much longer, but to have been born into this now developing time is stunning and, so to speak, incomprehensible.

As an 8-year-old boy, I thought:

What a monotonous, boring world!

In the morning, Father leaves the house, after a thunderstorm the sun shines, a sun that will never go out.

After a harsh winter, the snowdrops arrive.

You could simply rely on things, those growing up imagined.

When it came to war (right next door in 1943) and marital crisis, it was almost impossible to imagine anything tangible as a child.

It is simply astonishing how children are able to suppress anything that could impair the development and strengthening of their organs.

Above: Playing Children, Su Hanchen (1150)

Perhaps there is some small consolation today in no longer knowing everything:

That what is to come has rarely turned out to be the best thing in the world…

But I would have loved to experience the great, coming, revolutionary transformation, whatever the outcome.

Whether the digital age will become the root of a new humanism, or whether capital will continue to reduce the human person — as philosopher and media critic Byung-Chul Han puts it — to customer or market value.

Above: South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han

“We live in a transparent department store in which we, as transparent customers, are monitored and controlled.”

If Han calls for an escape, digitalization can both be helpful and lead to the absolutization of neo-capitalist structures.

It’s up to us.

F. Ictitious (Interviewer):

One is divided…

Self-consolation is also necessary.

Perhaps you’re not missing anything at all.

Humanity can….

J. Schoop:

Soon, they will also become completely stupid, which is what their Smartphone usage suggests.

Mothers now push their strollers one-handed…

Art changes people.

Most people would rather be dead than change.

Jürg Schoop, Gallery Zund (St. Gallen) exhibition brochure (1963)

Above: Kunstmuseum (art museum), St. Gallen, Switzerland

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1249)

Egnach, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 4,985)

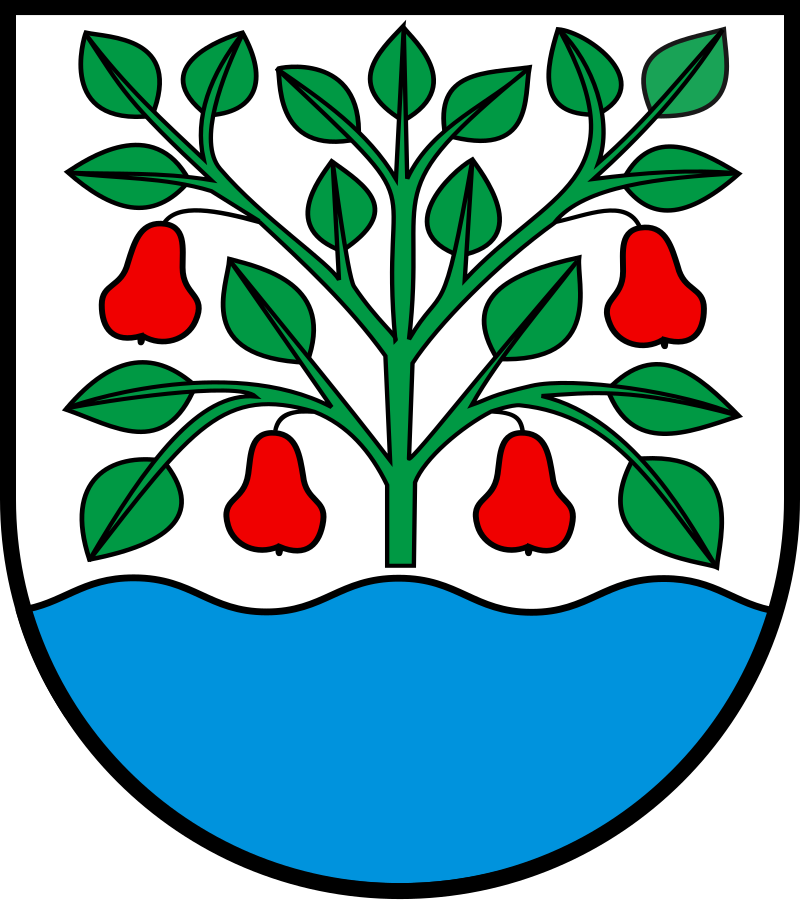

Above: Coat of arms of Egnach

The municipality of Egnach lies on the shores of Lake Constance between Arbon and Romanshorn.

It covers an area of 18.50 km², of which 16.4 km² is cultivated land, 0.75 km² is forest, and 2.8 km is lakefront.

The extensive scattered settlement includes the settlement centers of Egnach on Lake Constance, Neukirch and Steinebrunn on the Amriswil-Arbon road, as well as 68 hamlets and farms, including Buch, Hegi, Winden and Burkartshaus.

The municipal administration is located in Neukirch.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the Alemanni cleared the Egnach part of the Arbon Forest.

Above: The Gutenstein sword scabbard from an Alemannic warrior grave

Some place names suggest that the area had previously been inhabited by the Celts and Romans.

The Egnach Primeval Forest was crossed by the Roman military road that led from Arbor felix (Arbon) to Ad fines (Pfyn).

Above: Arbon Forest

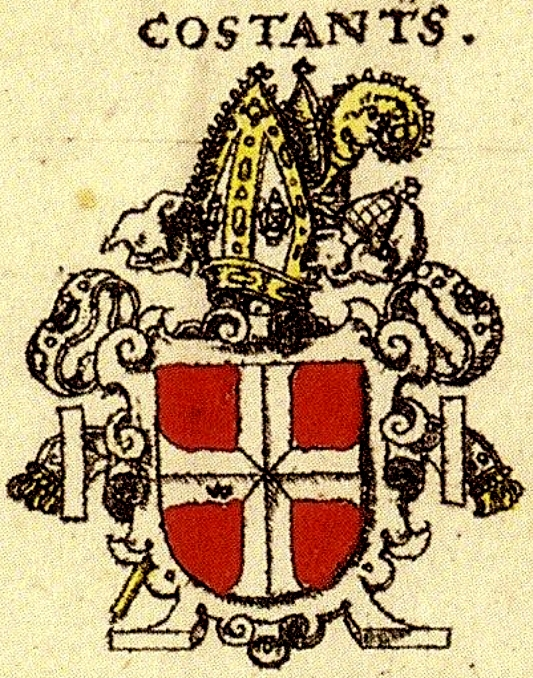

In the 9th century, Egnach likely belonged to the Bishopric of Constance and was administered by the Bishopric of Constance’s High Vogtei of Arbon.

Above: Coat of arms of the Bishropic of Konstanz

The Abbey of St. Gallen also acquired land in Egnach, which led to competing legal claims between the Abbot and the Bishop (Contract of 854).

Above: St. Gallen Abbey

Egnach was first mentioned as Egena in 1155.

In the late Middle Ages, Egnach was a focal point of the Bishopric of Konstanz’s holdings, as evidenced by the Kehlhöfe estates in Egnach, Erdhausen and Wiedehorn.

After the Swiss Confederation conquered Thurgau in 1460, the new rulers opposed the Bishop’s claims.

While the lower jurisdiction remained in the hands of the Bishop until 1798, he lost the higher jurisdiction to the Swiss Landvogt in Thurgau in 1509.

With the opening of the lower court in 1544, Egnach received its own lower court.

Above: Coat of arms of Canton Thurgau

Ecclesiastically, Egnach has always belonged to the Parish of Arbon.

In 1515, a mass benefice was established in the St. James Chapel in Erdhausen, and from 1588, Reformed services were held.

The Gallus Chapel in Steinebrunn remained – after a long period of closure – under the Catholics.

The residents, who had been predominantly Reformed since 1528, were able to build a church in Neukirch in 1727 and henceforth formed the Reformed Parish of Egnach.

Above: Egnach

The first schools were established in the 18th century.

There were no trained teachers, and those who felt a calling offered their rooms and called themselves schoolmasters.

Students paid their weekly school fees in cash and brought a log of wood for the stove in winter.

Dozens of children of all ages crammed into wide pews and learned to spell.

Schools thus sprang up across the sprawling community in Olmishausen, Ringenzeichen, Wilen, Hegi and Neukirch near the new church.

Everyone attended the school they liked, and so the students wandered back and forth throughout the community.

In Steinebrunn, the benefice taught the Catholic students.

Above: Egnach

Egnach was divided into 13 “Rotten” (companies), which, in addition to military training, also took on community tasks.

In 1803, the municipal and local community of Egnach (Egnach District) was formed, with its assembly place being Neukirch.

After the founding of the canton of Thurgau, a school law was passed for the first time in 1833.

Five primary school districts were created in Egnach:

- Wilen

- Olmishausen

- Hegi

- Ringenzeichen

- Neukirch

With the addition of the village of Egnach in 1880, this number increased to six.

Initial ideas for a secondary school led to the establishment of the secondary school in 1854.

A further education school was established in the 19th century.

In 1857, the Rotten Feile and Frasnacht (Inner Egnach), which had not participated in the formation of the new Parish of Egnach, separated from Egnach and formed the local community of Frasnacht, which belonged to the municipal community of Arbon.

In 1858, Lengwil and Balgen were separated from the local and municipal community of Roggwil and assigned to the community of Egnach.

In 1870, the spatially identical local and municipal communities of Egnach were merged to form the unified community of Egnach.

Field fruit growing began as early as the 18th century, which earned the area around Egnach the name “Mostindien“.

Around 1850, traditional arable farming gave way to livestock and dairy farming with numerous cheese dairies.

Above: Egnach

Various branches of textile production flourished in Egnach:

- The linen trade in the early 19th century

- hand embroidery around 1900

- mechanical and shuttle embroidery in the 20th century.

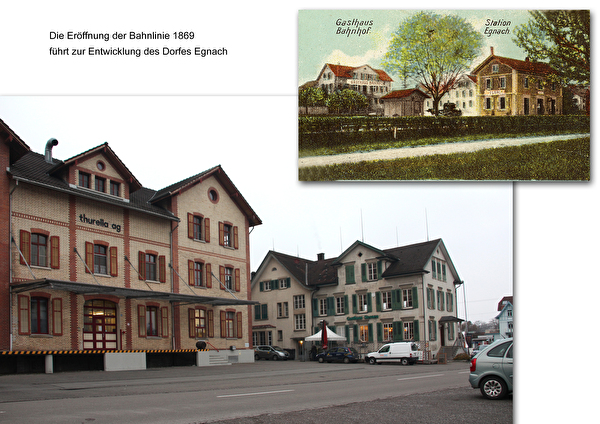

In 1869, the Romanshorn – Rorschach railway line was built, and Egnach received a train station.

Above: Egnach Bahnhof (train station), Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

In 1910, the Lake Constance-Toggenburg Railway was built, which is now operated by the Südostbahn (SOB), with stations in Neukirch, Steinebrunn and Winden.

The opening of the two railway lines brought new economic opportunities.

In 1900, a cider and fruit export cooperative was founded.

An important milestone was the establishment of the final year school in 1955, which later became the Realschule (secondary school).

In 2000, the first economic sector provided approximately 1/5 and the second one 1/3 of jobs in Egnach.

Despite some industrial buildings and residential areas, Egnach has retained its rural character to this day due to intensive fruit growing.

In 2000, all schools in Egnach were combined to form the primary school district with a single administration.

The new Neukirch secondary school was inaugurated in 2016.

In 2016, Egnach provided full time employment to 188 people.

Of these, 8.4% worked in agriculture and forestry, 54.8% in industry, commerce and construction, and 36.8% in the service sector.

Above: Egnach

Founded in 1965, Zünd AG was first renamed Frutella AG and subsequently Thurella Agroservice AG.

This company was acquired by Landi Oberthurgau AG of Roggwil in 2009.

There is a campsite directly on the shores of Lake Constance.

Farm holidays are also available.

The Egnach Transport and Beautification Association (VVE) aims to preserve and promote the transport, landscape, and culture of Egnach.

Above: Egnach

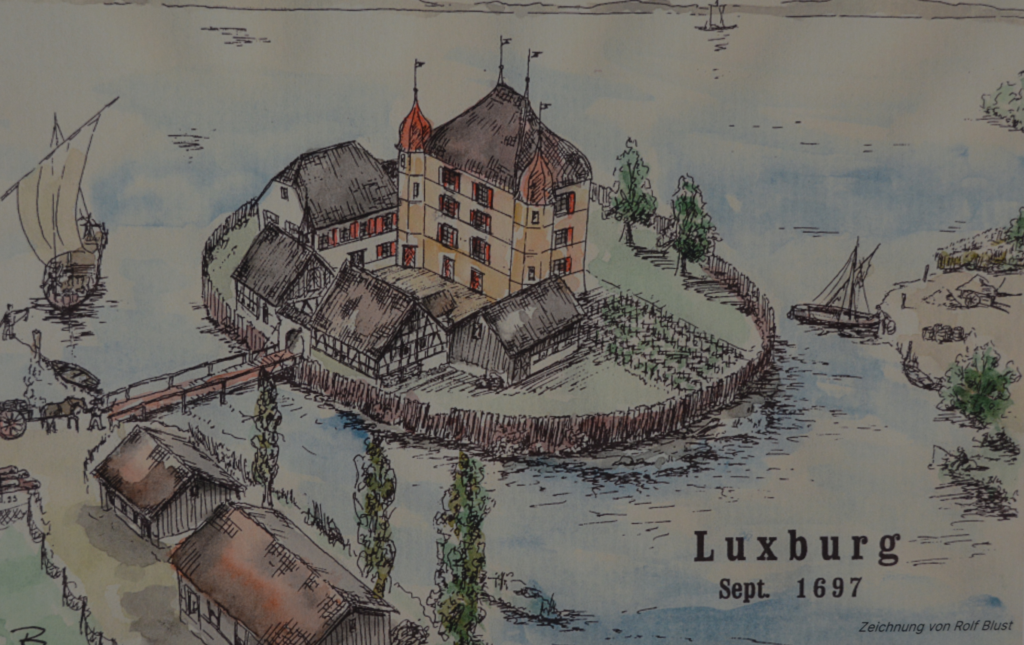

The entrance to Luxburg Castle in Egnach is not easily found, as though it resists the intrusions of the present, yearning instead for the veiled solemnity of forgotten places.

One does not simply stumble upon it but must seek it, deciphering its location like a scholar parsing an ancient manuscript.

The castle, hidden amidst the well-ordered banality of a 1960s housing development, seems at once tantalizingly near and impossibly distant, its presence more a whisper than a proclamation.

The road, with an almost mischievous reluctance, bifurcates into Luxburgstrasse and Schlossweg, two tributaries leading toward history, as if uncertain which shall be privileged with the honor of delivering the visitor to their long-sought destination.

Between the homes, neatly built and uniformly practical, a glimpse — no more than a shimmer, an impression in the periphery — reveals a small castle half-concealed by bushes, its stone walls breathing stories that these modern dwellings, efficient yet devoid of poetry, could never tell.

A princely gate of wrought iron stands as a promise, its ornate design whispering of the grandeur that lies beyond, of times when gates did not merely function but proclaimed.

Yet this promise is soon tempered by reality:

The gate, locked not with the grace of noble solitude but with a crude chain and padlock, speaks of pragmatism rather than mystery, a barrier not to be breached without negotiation.

Above: Luxburg, Egnach

Disappointed but undeterred, the journey must continue — for if not Luxburgstrasse, then Schlossweg.

And there, at last, another gate — less austere, more yielding, its purpose not to refuse but to beckon.

Upon it, wooden letters, weathered by time yet resolute, proclaim the name Luxburg.

The sight, oddly evocative, calls to mind not the imposing threshold of a grand estate but rather the welcoming, if slightly theatrical, entrance to a traveling circus or a rustic fairground, where the fantastic and the ordinary intermingle in delightful disarray.

And yet, behind this unassuming portal, the Castle stands — a diminutive marvel, at once humble and magnificent, cradled within an enchanted park where nature and human devotion engage in a quiet, unspoken dialogue.

Against the gray stone, yellow coneflowers bloom defiantly, their brightness an affirmation of life amid the fortress’s subdued dignity.

Near them, an old stone basin, its timeworn surface now home to wild strawberry cuttings, each tender shoot nestled in repurposed collector’s cups — gestures of care, improvisations of beauty, far removed from the sterile precision of professional garden design.