Saturday 22 March 2025

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

Above: St. Leonhard’s Chapel, Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland

As I try to revitalize my spirits in regards to my dual ambitions as teacher and writer, I slowly return to life through the writing of this blog.

I have tried to keep a chronicle of calendar dates since 1 February 2025 but life has been very distracting, so I have fallen far behind today’s actual calendar date.

Since my involuntary return to and exile in Switzerland I have lain relatively dormant in my communication, but a visit to nearby Konstanz, Germany, and the purchase of this weekend’s edition of the New York Times has inspired me to speak of the headlines that captured my attention and incorporate these events with those of 20 February where I left off in my calendar chronicles.

Above: Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Friday 21 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Time is a river, carrying the echoes of voices past into the present, where they mingle with our own.

Above: Bridge over Porsuk River in Eskişehir, Türkiye

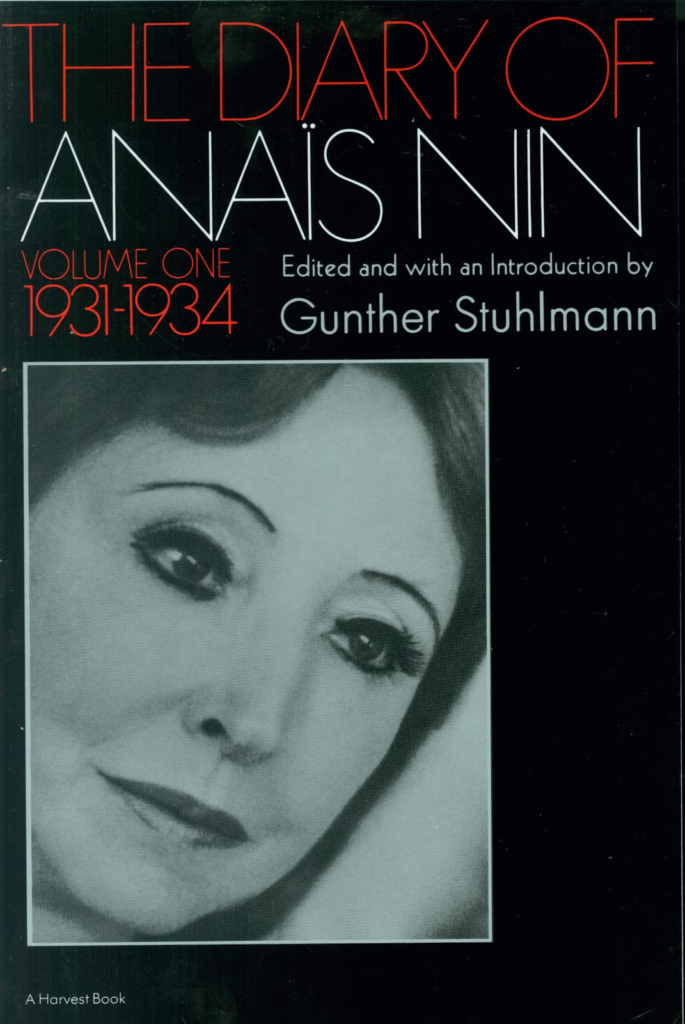

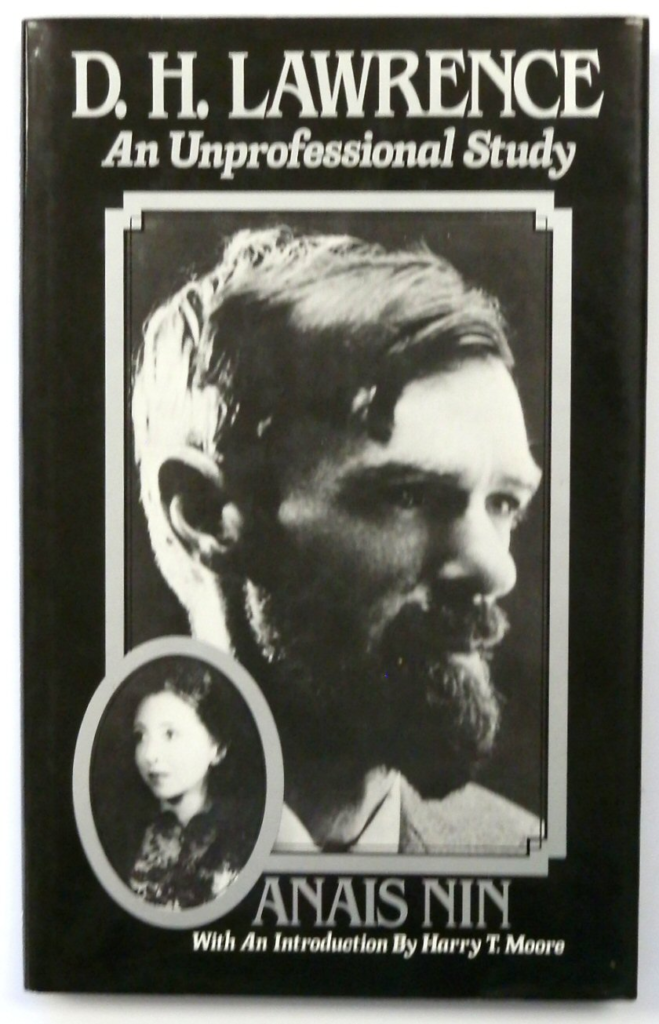

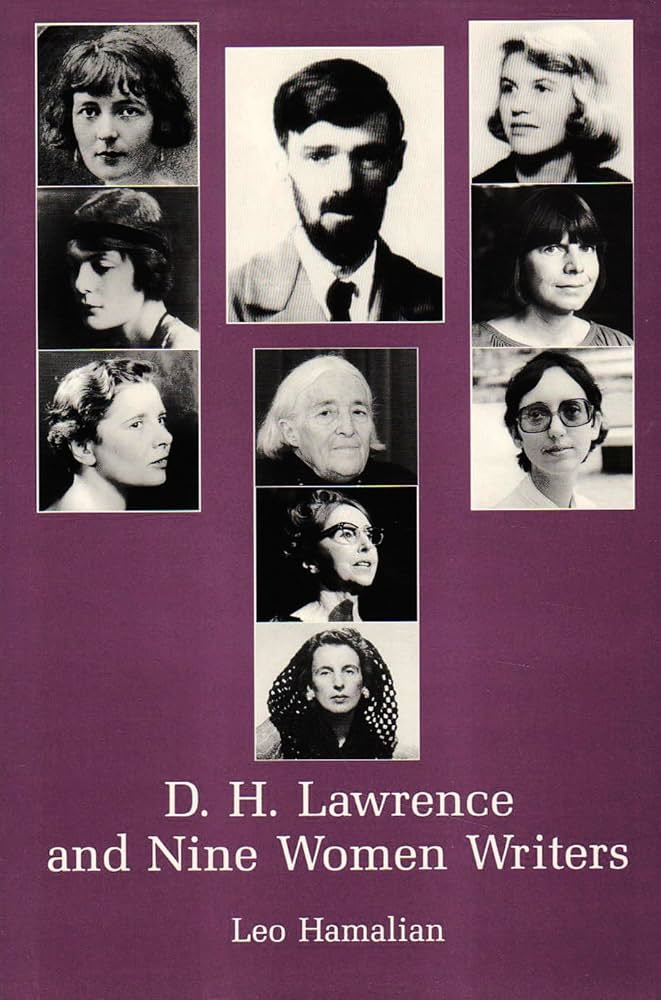

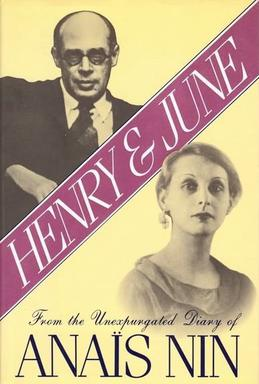

February 21 is a day marked by the births of three literary giants —José Zorrilla, W.H. Auden and Anaïs Nin — each of whom shaped our understanding of passion, tragedy, artistic creation, and the search for meaning.

Their words continue to resonate, transcending the limitations of time and culture, speaking to the universal struggles and desires that define human experience.

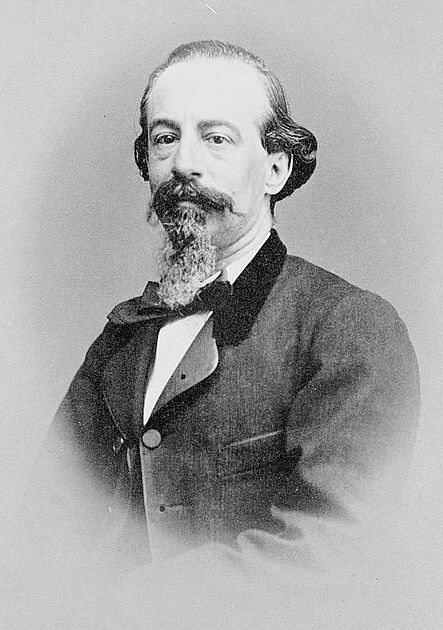

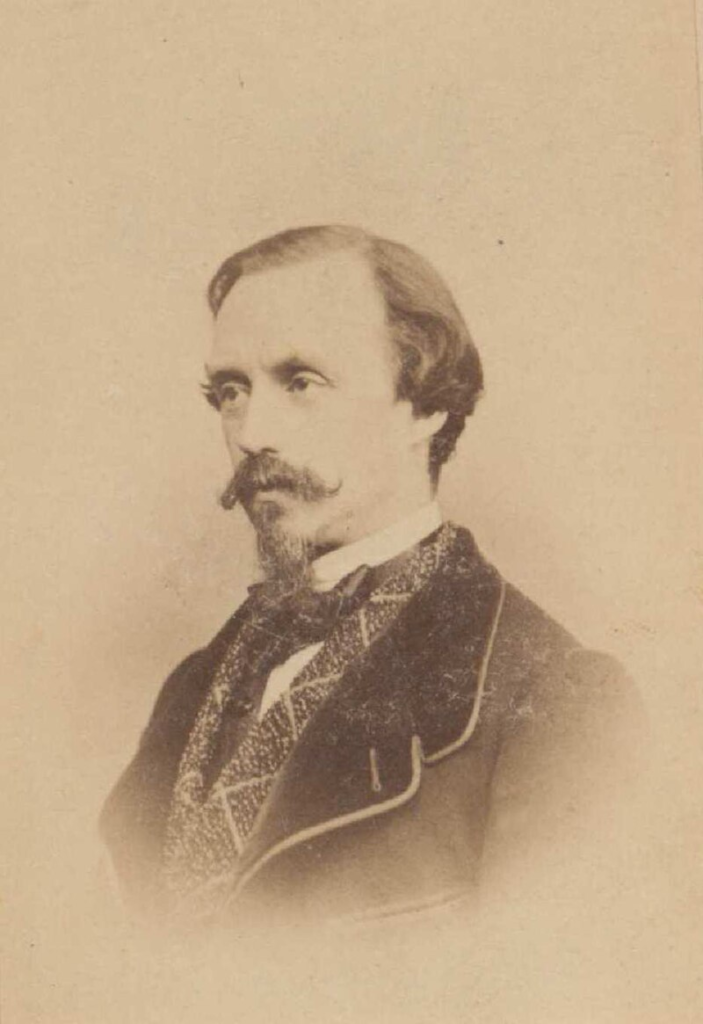

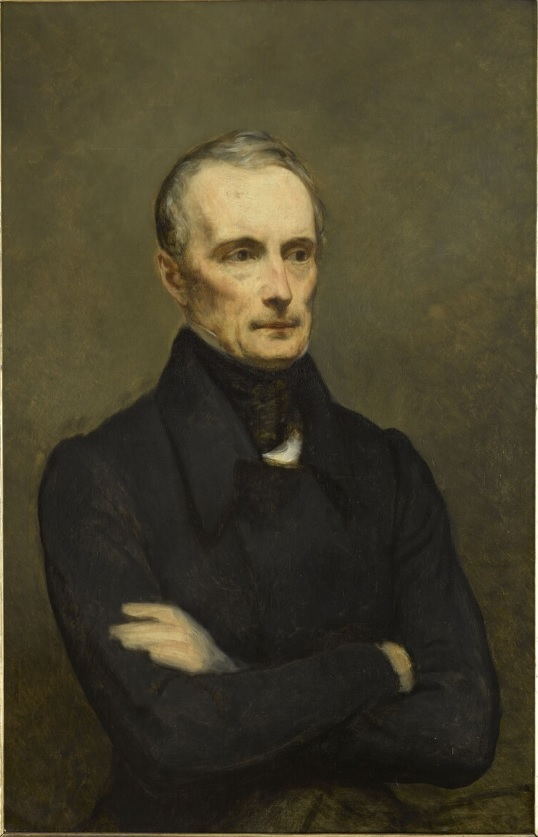

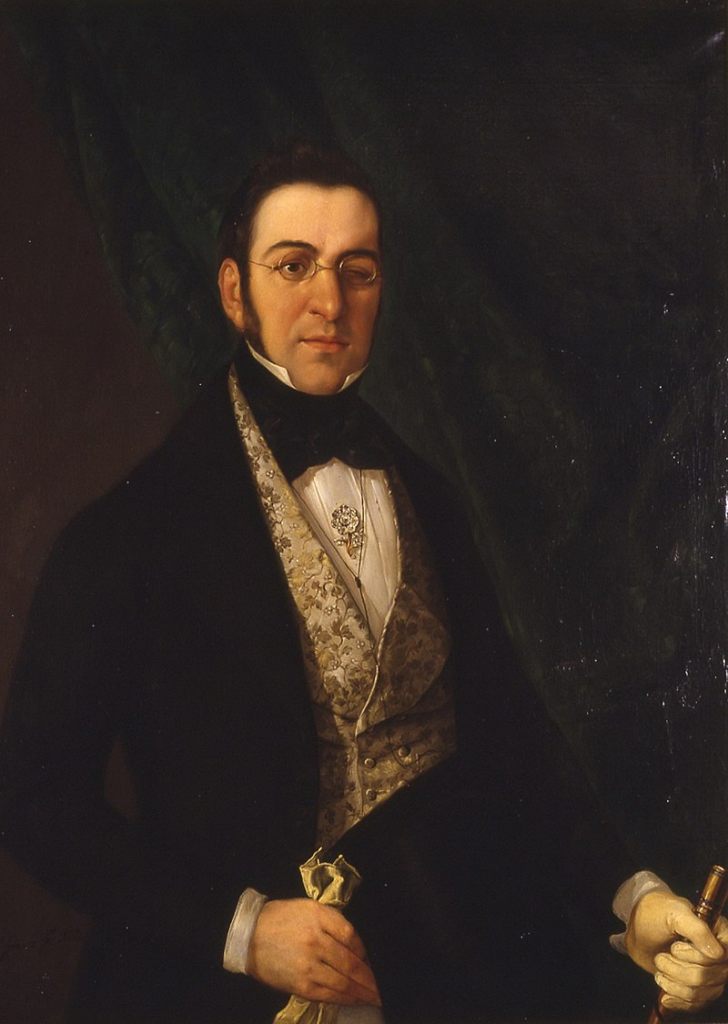

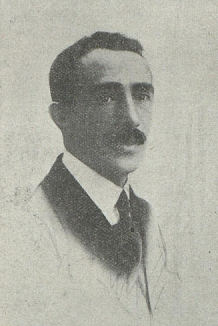

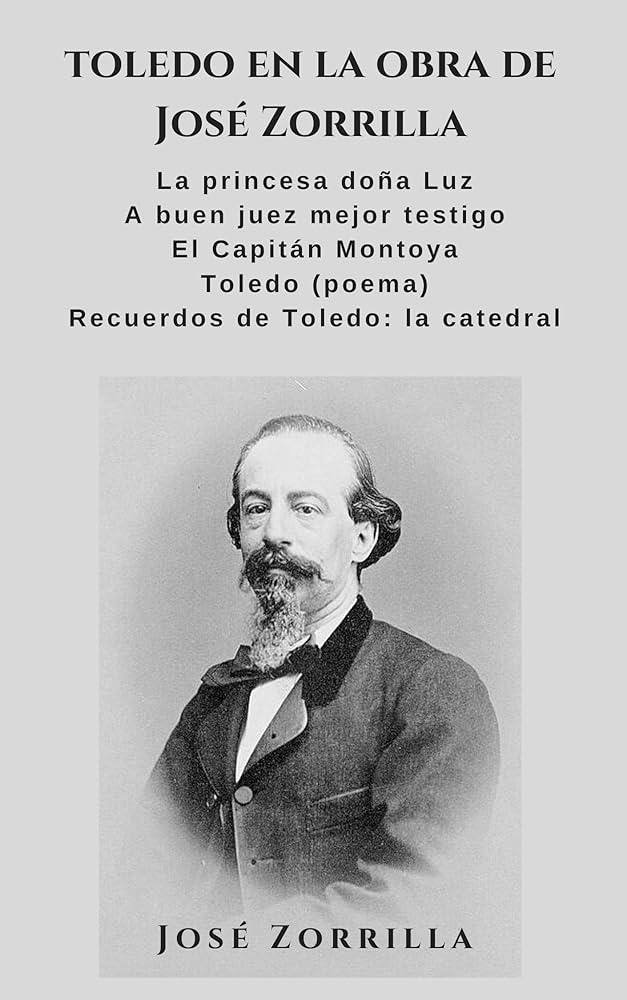

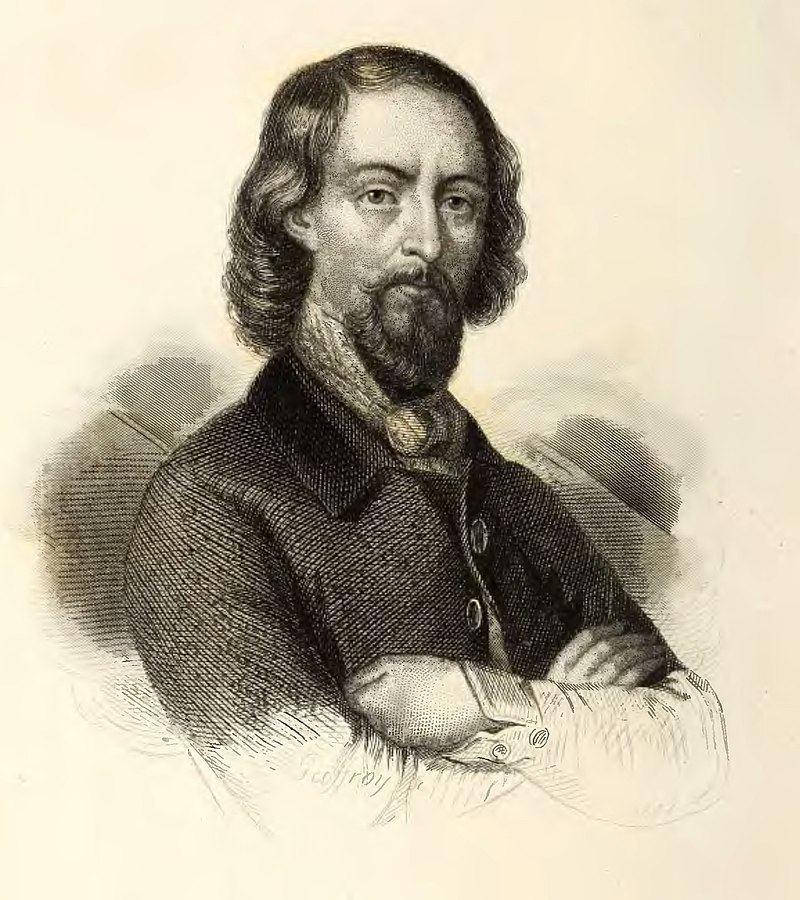

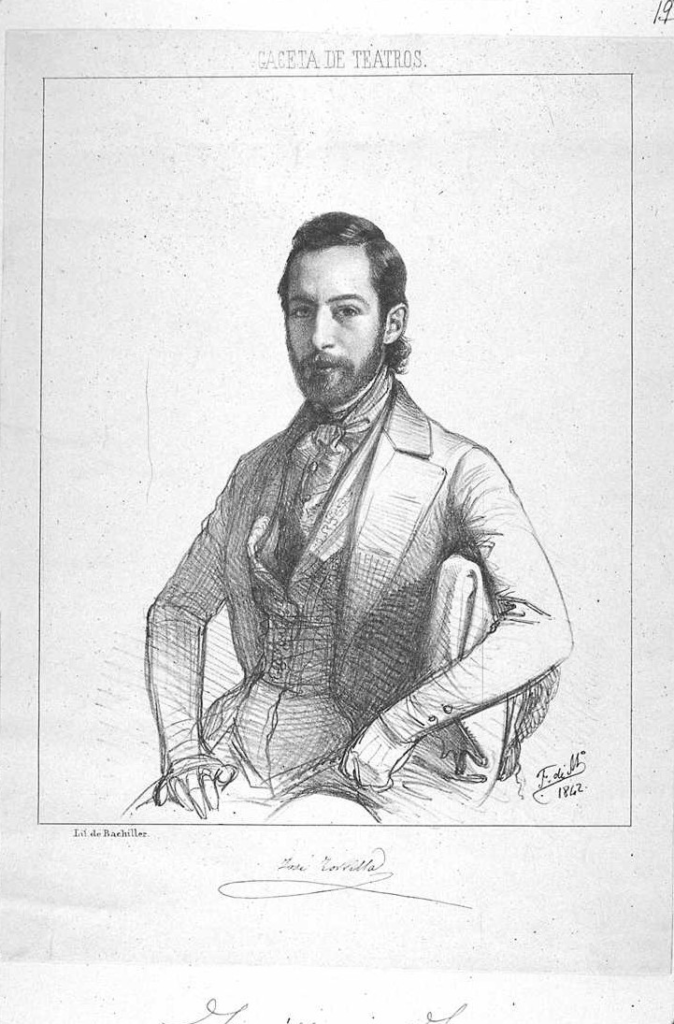

José Zorrilla was a Spanish poet and dramatist (21 February 1817 – 23 January 1893).

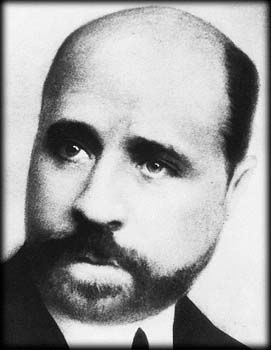

Above: Spanish author José Zorrilla

Zorrilla was born in Valladolid to a magistrate in whom Fernando VII placed special confidence.

Above: Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain

Above: Spanish King Fernando VII (1784 – 1833)

He was the son of José Zorrilla Caballero, an old-fashioned man with a traditionalist ideology, a follower of the pretender

Carlos María Isidro de Borbón and a reporter for the

Royal Chancellery.

Above: Spanish Infante Don Carlos (1788 – 1855)

His mother, Nicomedes Moral, was a very pious woman.

After several years in Valladolid, the family passed through

Burgos (where his father was appointed Governor) and

Seville, finally settling, when the boy was nine years old (1827),

in Madrid, where his father worked with great zeal as mayor of the house and court and superintendent of police under the orders of

Francisco Tadeo Calomarde.

Above: Burgos, Castile and León, Spain

Above: Plaza de España, Seville, Andalusia, Spain

Above: Madrid, Spain

Above: Spanish Justice Minister Francisco Tadeo Calomarde (1773 – 1842)

The son entered the Seminary of Nobles, run by the Jesuits.

Above: Nobles’ Seminary, Madrid, Spain

There he participated in school theatrical performances and learned Italian well:

“At that school I began to develop the bad habit of neglecting the main things in order to focus on the secondary things, and, negligent in my serious studies of philosophy and the exact sciences, I applied myself to drawing, fencing, and fine arts, secretly reading Walter Scott, Fenimore Cooper and Chateaubriand, and finally, at the age of 12, committing my first crime of writing verse.

Above: Scottish writer Walter Scott (1771 – 1832)

Above: American novelist James Fenimore Cooper (1789 – 1851)

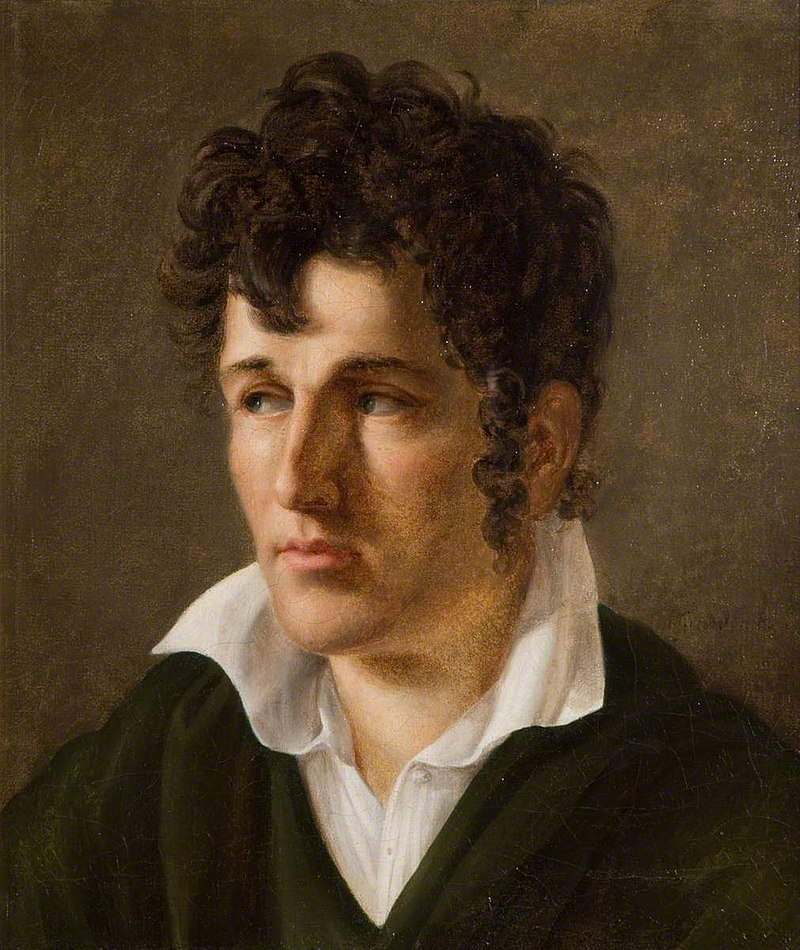

Above: French writer François-René de Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848)

The Jesuits celebrated them for me and encouraged my inclination.

I began to recite them, imitating the actors I saw at the theater when I sometimes went to the Prince’s Theater, which was then presided over by the mayors of the house and court, whose toga my father wore.

I became famous at the examinations and public events at the Seminary, and became a leading man at the theater where these were held and where some comedies from the ancient theater, revised by the Jesuits, were performed.

In which, according to morality, lovers became brothers.

Above: Teatro Español, Madrid, Spain

With this system a moral hodgepodge resulted that made the malicious Ferdinand VII smile and his brother, the Infante Don Carlos, frown when they sometimes attended our Christmas services.

Don Carlos sent his children to our classrooms and to do his duty at the church in our chapel.

To which His Holiness Gregory XVI had sent his blessing and the wax bodies of two holy young martyrs, beheaded in Rome, whose beheaded figures frightened me so much that I never passed by the chapel at night on whose side altars they lay.”

Above: Italian Pope Gregorio XVI (né Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari Pagani Gesa)(1765 – 1846)

Zorrilla took part in the school performances of plays by Lope de Vega and Calderón de la Barca.

Above: Spanish writer Lope de Vega (1562 – 1635)

Above: Spanish writer Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600 – 1681)

After the death of Ferdinand VII, the furious absolutist father was banished to Lerma.

Above: Lerma, Burgos, Spain

His son was sent to study law at the Royal University of Toledo under the supervision of a canon relative in whose house he stayed.

However, the son was distracted by other occupations.

The law books fell out of his hands.

The canon returned him to Valladolid to continue studying there (1833 – 1836).

Above: Main facade of the Palace of Cardinal Lorenzana, inaugurated on 22 April 1799, which was the headquarters of the former

Royal University of Toledo (1520 – 1845)

When the wayward son arrived, he was admonished by his father, who then went to the town of his birth, Torquemada, and by

Manuel Joaquín Tarancón y Morón, Rector of the University and future Bishop of Córdoba.

Above: Torquemada, Palencia, Spain

Above: Spanish Cardinal Manuel Joaquin Tarancón y Morón (1782 – 1862)

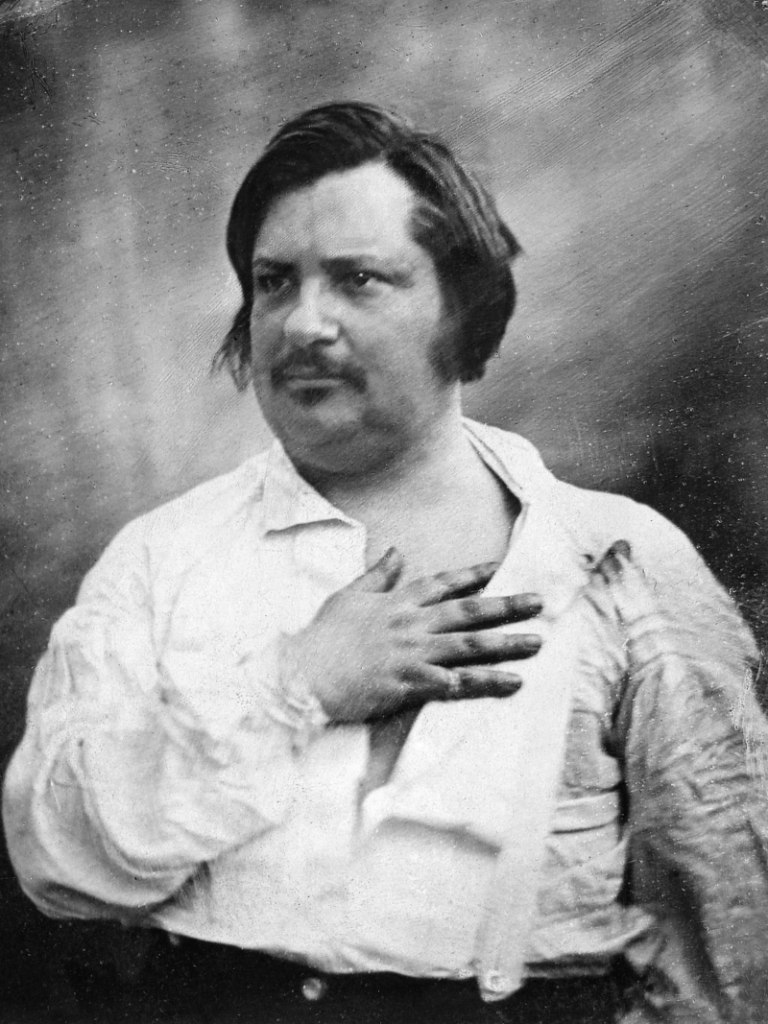

The imposed nature of his studies and his attraction to drawing, women (a cousin with whom he fell in love during a vacation) and the literature of authors such as Chateaubriand’s The Genius of Christianity, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, the Duke of Rivas, and Espronceda, whom he found and read at the house of Pedro de Madrazo y Kuntz, a friend who was studying law with him and felt the same attraction to art, ruined his future as a lawyer.

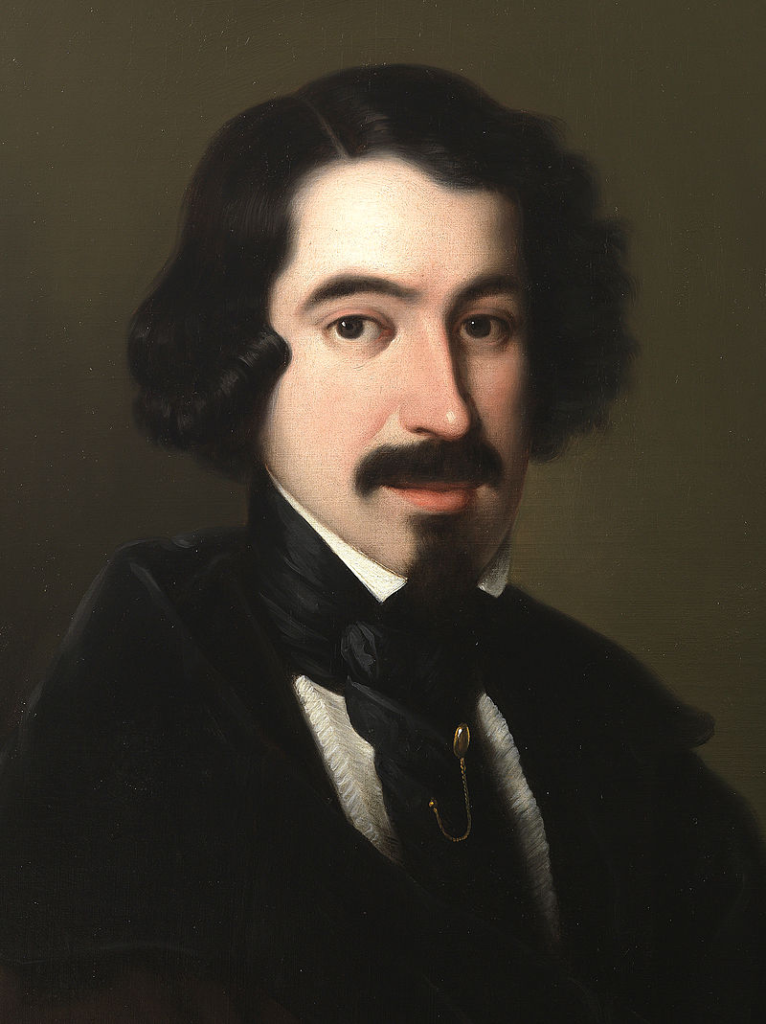

Above: French writer Alexandre Dumas (Père)(1802 – 1870)

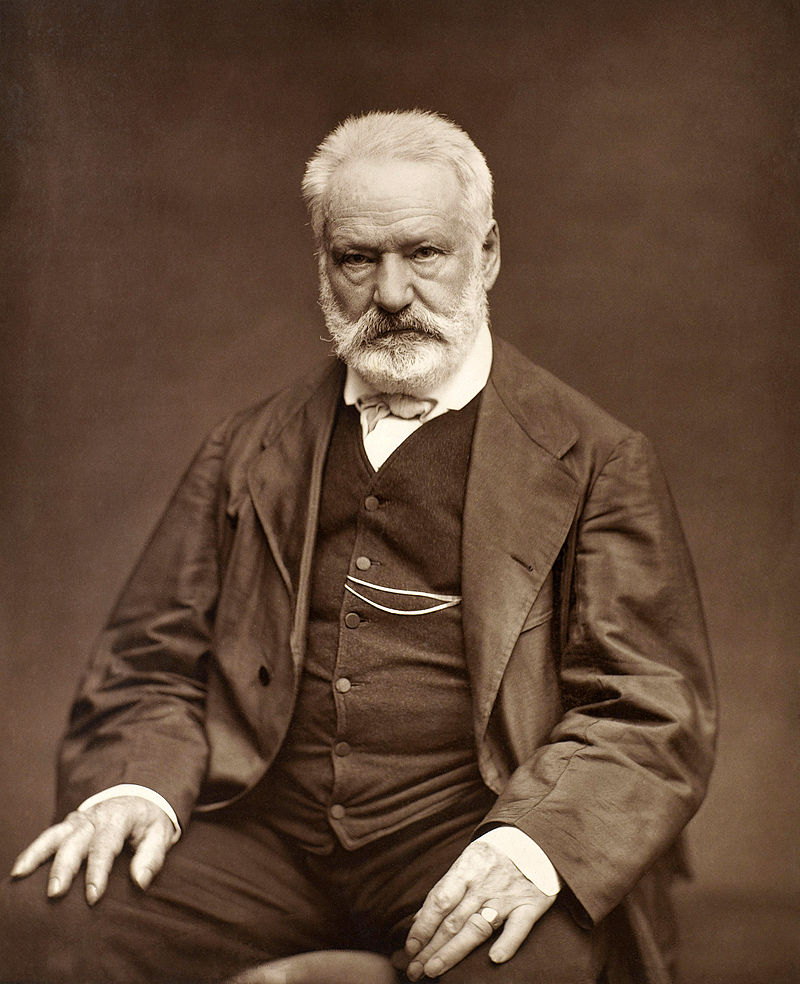

Above: French writer Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

Above: Spanish writer/statesman Àngel de Saavedra, Duke of Rivas (1791 – 1865)

Above: Spanish writer José de Espronceda (1808 – 1842)

Above: Spanish artist Pedro de Madrazo y Kuntz (1816 – 1898)

By then Zorrilla discovered that he was a sleepwalker:

Sometimes he would go to bed leaving a poem unfinished and wake up seeing it finished, or he would go to bed with a beard and wake up shaved, so he asked to be allowed to sleep under lock and key.

The father gave up trying to get anything out of his son and ordered him to be taken to Lerma to dig vineyards.

But when he was halfway there, the son stole a mare from a cousin, fled to Madrid (1836) and began his literary career, frequenting the artistic and bohemian circles of Madrid, together with his friend Miguel de los Santos Álvarez, and suffering hunger.

Above: Spanish writer Miguel de los Santos Álvarez (1818 – 1892)

He pretended to be an Italian artist to draw for the Museum of Families, published some poems in El Artista and gave revolutionary speeches at the Café Nuevo, so that he ended up being pursued by the police.

Above: Title of the Spanish cultural magazine

Museo de las Familias (Museum of Families)

He took refuge in the house of a gypsy.

At that time he became friends with the Italian baritone Joaquín Massard.

The death of the satirist Mariano José de Larra brought Zorrilla into notice.

His elegiac poem, read at Larra’s funeral in February 1837, introduced him to the leading men of letters.

Above: Spanish writer Mariano José de Larra (1809 – 1837)

Upon Larra’s death, at Massard’s insistence, José Zorrilla composed and recited in his memory a poem that would earn him the deep friendship of José de Espronceda, Antonio García Gutiérrez and Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch and would ultimately establish him as a renowned poet, to which these verses belong:

That the poet, in his mission

On the earth he inhabits

Is a cursed plant

With fruits of blessing

Above: Spanish writer Antonio García Gutiérrez (1813 – 1884)

Above: Spanish writer Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch (1806 – 1880)

Zorrilla then began writing for the newspapers El Español, where he replaced the deceased, and El Porvenir, where he earned a salary of six hundred reales.

He began to frequent the El Parnasillo gatherings and read poems at El Liceo.

El Parnasillo was a Romantic gathering held at the Café del Príncipe on the street of the same name.

This establishment, now defunct, was located in Madrid’s Barrio de las Letras, next to the Teatro Español, formerly the Corral del Príncipe.

From 1829 onwards, the Café and gathering became a meeting place for writers belonging to the Romantic movement.

Above: Some of the regular members of the Parnasillo gathering appear in this painting by Antonio María Esquivel, gathered in his studio in 1846.

This work is the most famous painting by the Sevillian painter Antonio María Esquivel (1806 – 1857), and one of the most outstanding of Spanish Romanticism.

The characters portrayed, apart from the painter himself, are the following:

- Antonio Ferrer del Río (1814 – 1872)

- Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch (1806 – 1880)

- Juan Nicasio Gallego (1777 – 1853)

- Antonio Gil y Zárate (1793 – 1861)

- Tomás Rodríguez Rubí (1817 – 1890)

- Isidoro Gil y Baus (1814 – 1866)

- Cayetano Rosell y López (1817 – 1883)

- Antonio Flores (1818 – 1866)

- Manuel Bretón de los Herreros (1796 – 1873)

- Francisco González Elipe (1813 – 1868)

- Patricio de la Escosura (1807 – 1878)

- José María Queipo de Llano, Count of Toreno (1786 – 1843)

- Antonio Ros de Olano (1808 – 1887)

- Joaquin Francisco Pacheco (1808 – 1865)

- Mariano Roca de Togores (1812 – 1889)

- Juan Gonzalez de la Pezuela (1809 – 1906)

- Angel de Saavedra, Duke of Rivas (1791 – 1865)

- Gabino Tejado (1819 – 1891)

- Javier de Burgos (1778 – 1848)

- José Amador de los Rios (1818 – 1878)

- Francisco Martinez de la Rosa (1787 – 1862)

- Carlos Garcia Doncel (1815 – 1850)

- Luis Valladares y Garriga (d. 1856)

- José Zorrilla (1817 – 1893)

- José Guell y Renté (1818 – 1884)

- José Fernandez de la Vega (1803 – 1851)

- Ventura de la Vega (1807 – 1865)

- Luis de Olona (1823 – 1863)

- Julian Romea (1818 – 1863)

- Manuel José Quintana (1772 – 1857)

- José de Espronceda (1808 – 1842)

- José Maria Diaz (1813 – 1888)

- Ramon de Campoamor (1817 – 1901)

- Manuel Cañete (1822 – 1891)

- Pedro de Madrazo y Kuntz (1816 – 1898)

- Aureliano Fernandez Guerra (1816 – 1891)

- Ramon de Mesonero Romanos (1803 – 1882)

- Candido Nocedal (1821 – 1885)

- Gregorio Romero de Larrañaga (1814 – 1872)

- Bernardino Fernandez de Velasco y Pimentel, Duke of Frias (1783 – 1851)

- Eusebio Asquerino (1822 – 1892)

- Manuel Juan Diana (1814 – 1881)

- Agustín Durán (1793 – 1862)

Zorrilla was also an editor for El Entreacto, a theatre criticism publication.

In 1837 he published a book of verses, his first book, Poesías (Poems), mostly imitations of Alphonse de Lamartine and Victor Hugo, with a prologue by Nicomedes Pastor Díaz, which was so favorably received that he printed six more volumes within three years.

Above: French writer Alphonse de Lamartine (1790 – 1869)

Above: Spanish writer Nicomedes Pastor Díaz (1811 – 1863)

His first play, written in collaboration with García Gutiérrez, was Juan Dándole, which premiered in July 1839 at the Teatro del Príncipe.

In 1840 he published his famous Cantos del trovador (Cantos of the troubadour) and premiered three other plays, Más vale llegar a tiempo (It’s worth arriving on time), Vivir loco y morir más (Living crazy and dying more), and Cada cual con su razón (Each with his own reason).

In 1842 his Summer Vigils appeared.

He released his plays The Shoemaker and the King (first and second parts), The Echo of the Torrent and The Two Viceroys.

From 1840 to 1845, Zorrilla was exclusively contracted by Juan Lombía, entrepreneur of the Teatro de la Cruz, where he premiered no less than 22 dramas during those five seasons.

Above: Approximate location of the former Corral de comedias de la Cruz in Madrid, on Pedro Teixeira’s map, around 1656

His Cantos del trovador (Songs of the troubador)(1841), a collection of national legends written in verse, made Zorilla second only to José de Espronceda in popular esteem.

He was so recognized that at the end of 1843 he received from the Government of Spain the supernumerary cross of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Carlos III together with playwrights Manuel Bretón de los Herreros and Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch.

Above: Spanish playwright Manuel Bretón de los Herreros (1796 – 1873)

National legends also supply the themes of his dramas, which Zorilla often constructed by adapting older plays that had fallen out of fashion.

For example, in El Zapatero y el Rey (The shoemaker and the King) he recasts El montanés Juan Pascual (The mountaineer Juan Pascual) by Juan de la Hoz y Mota.

Above: Spanish playwright Juan de la Hoz y Mota (1622 – 1714)

In La mejor Talon la espada (The best talon: the sword) he borrows from Agustín Moreto y Cavana’s Travesuras del estudiante Pa-atoja (Student Pa-atoja’s pranks).

Above: Spanish playwright Agustín Moreto (1618 – 1669)

His famous play Don Juan Tenorio is a combination of elements from Tirso de Molina’s Burlador de Sevilla (The trickster of Seville) and from Alexandre Dumas, Père’s Don Juan de Marana (which itself derives from Les Âmes du purgatoire (The souls of Purgatory) by Prosper Mérimée).

However, plays like Sancho García, El Rey loco (The mad King), and El Alcalde Ronquillo (Mayor Ronquillo) are much more original.

He considered his last play, Traidor, inconfeso y mártir (Unconfessed traitor and martyr)(1845), to be his best play.

In 1838 he had married Florentina Matilde O’Reilly, a ruined Irish widow 16 years his senior and with a son from her previous husband, José Bernal, but the marriage was unhappy.

One of their daughters died a year after she was born.

He had several lovers – something that Doña Florentina was not willing to tolerate and aired publicly, and which ended up alienating the poet from his family, making him abandon the theater and, finally, after the dazzling success of Don Juan Tenorio in 1844, conceived in a sleepless night and written in 21 days, he abandoned his wife in 1845 and emigrated to France and then to Mexico (1855), where his wife’s angry letters and anonymous accusatory letters still arrived.

He had to return to Madrid when his mother died in 1846.

Zorrilla again left Spain.

He resided for a while at Bordeaux, then settled in Paris, where his incomplete poem Granada was published in 1852.

Upon his return to Paris, he printed two volumes of Works of D. José Zorrilla (I: Poetic Works / II: Dramatic Works) at the Casa Baudry, along with a biography of Ildefonso Ovejas.

There he maintained a friendship with Alexandre Dumas, Alfred de Musset, Victor Hugo, Théophile Gautier and George Sand.

Above: French writer Alfred de Musset (1810 – 1857)

Above: French writer Théophile Gautier (1811 – 1872)

Above: French writer Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin (aka George Sand)(1804 -1876)

As he had sold off the rights to Tenorio at a loss, he was unable to collect royalties for its many revivals.

His efforts to recover them were in vain.

In 1849, he received several honors:

He was made a member of the board of the recently founded

Teatro Español.

The Liceo organized a session to publicly exalt him.

The Royal Spanish Academy admitted him to its ranks, although he only took possession of the literary chair on 31 May 1885, with the verse speech Poetic Autobiography and Self-Portrait.

Above: Real Academia Española, Madrid, Spain

But his father died that same year and that was a hard blow for him, because he refused to forgive him, leaving a great weight on the conscience of the son (and considerable debts), which affected his work. El puñal del godo and Traidor, inconfeso y mártir were great successes, some more in their revivals than in their premieres.

After leaving his wife again, he returned to Paris in 1850, where his sorrows were soothed by his lover Leila, to whom he devoted himself passionately and whom some sources identify with Emilia Serrano de Wilson, surely being the father of his daughter Margarita Aurora, who died at the age of 4.

Above: Spanish writer Emilia Serrano de Wilson (1834 – 1923)

There Zorrilla wrote the two volumes of his poem Granada.

In 1852 the Baudry house printed a third volume of Poetic and Dramatic Works.

He traveled to London in 1853, where he was accompanied by his inseparable financial difficulties, from which the famous watchmaker

Losada rescued him.

Above: Spanish watchmaker José Rodriguez Losada (1797 – 1870)

At that time he composed his famous Serenata morisca in honor of

Eugenia de Montijo, who in that same year had married the Emperor

Napoleon III.

Above: French Empress Eugènie de Montijo (1826 – 1920)

Above: French Emperor Napoleon III (1808 – 1873)

They were going to give him the Legion of Honor, but again some angry letters from his wife put an end to that.

In a fit of depression, Zorrilla emigrated to America three years later, hoping, he claimed, that yellow fever or smallpox would kill him.

During 11 years in Mexico he wrote very little.

Above: Flag of Mexico

Zorrilla arrived in Veracruz on 9 January 1855.

He was enthusiastically welcomed (despite the fact that false quintessential works had been spread in his name against the country), first by the liberal government (1854-1866), spending long periods in the Apan Valley, where he had a new love affair with a woman named Paz.

Above: Images of Veracruz, Mexico

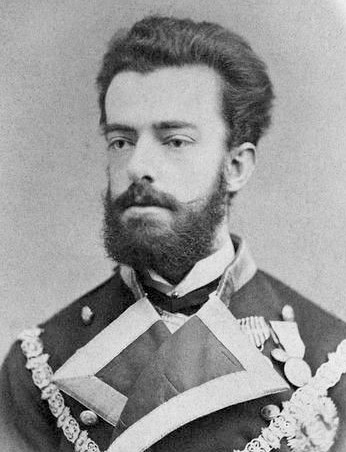

Then under the protection and patronage of Emperor Maximilian I, with an interruption in 1858, the year he spent in Cuba.

Above: Austrian-born Mexican Emperor Maximiliano I (1832 – 1867)

There Zorrilla began to suffer from epileptic attacks that would accompany him for the rest of his life.

One day, as I sat down at the table, the house spun around me, and the ground felt like nothing under my feet.

A loud noise, like distant music and bells, resounded thunderously in my head, and I lost consciousness.

Isidoro got up in a fright and immediately called his doctor.

They made me lie down.

I felt nauseous, dizzy and drowsy.

I remained like this for 48 hours.

On the 3rd day, the doctor found me working at seven in the morning.

They thought the vomiting had passed.

They congratulated themselves.

Alas!

It was the first hint of an epileptic condition that I combat today with doses of bromide that frighten the pharmacist to whom I am presenting for the first time the prescription for Dr. Cortezo, to whom, for it, I probably owe my life.”

In Cuba, Zorrilla tried his luck in the slave trade.

He established a partnership with the Spanish bookseller and journalist Cipriano de las Cagigas, son of a well-known slave trader, to import Indian prisoners of war against the Maya of Yucatán (Mexico) and sell them to the Cuban sugar plantations.

Zorrilla bought a group of Indians in Campeche, but Cagigas’ death from yellow fever liquidated the business.

Above: Flag of Cuba

Zorrilla returned to Mexico in March 1859.

He led a life of isolation and poverty in that country, avoiding involvement in the civil war between the Federalists and Unitarians.

However, when Maximilian I came to power as Emperor of Mexico (1864), Zorrilla became a court poet and was appointed director of the now defunct National Theater.

Above: Gran Teatro Nacional de México (1844 – 1904)

After the death of his wife Florentina O’Reilly, a victim of cholera in October 1865, Zorrilla was finally free to return to Spain.

He embarked in 1866 and passed through Havana, Saint-Nazaire, Paris, Lyon, Avignon, Nimes and Perpignan, and finally arrived in Barcelona on 19 July.

Above: Images of Havana, Cuba

Above: Pont Mindin, Saint Nazaire, Loire-Atlantique, France

Above: Paris, France

Above: Lyon, Rhône, France

Above: Avignon, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, France

Above: Nîmes, Gard, France

Above: Perpignan, Pyrénées-Orientales, France

Above: Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

Zorrilla returned to Spain to find himself half-forgotten and considered old-fashioned.

He went to Valladolid on 21 September to settle his affairs, received many people at his home, attended bullfights, gave two readings at the Calderón Theater, and his play Sancho García was performed at the Lope de Vega Theater.

The newspapers were full of news about the poet, who was considered a national glory.

The poetess Carolina Coronado bore witness to this:

Zorrilla, what happened?

What do you have to tell us?

What happened? What did you hear?

Where have you been?

How long did it take you to come?”

Above: Spanish poetess Carolina Coronado (1820 – 1911)

On 14 October, he went to Madrid, where he remained for a few months overseeing the publication of his Album of a Madman.

In March 1867 he traveled again in search of his “beloved places“.

He wrote the critic Narciso Alonso Cortés, Torquemada (where his parents were buried) and then to Quintanilla-Somuñó (the Burgos land of his mother and of “cousin Gumis“, his first love).

Above: Spanish poet Narciso Alonso Cortés (1875 – 1972)

Above: Town Hall, Torquemada, Palencia, Spain

Above: Quintanilla Somuñó, Burgos, Spain

There they brought him a letter that his friend the Emperor Maximilian I had sent him from Mexico, dissuading him from returning to his side:

“Abdication is going to become necessary.

Avoid a useless trip and wait for orders.”

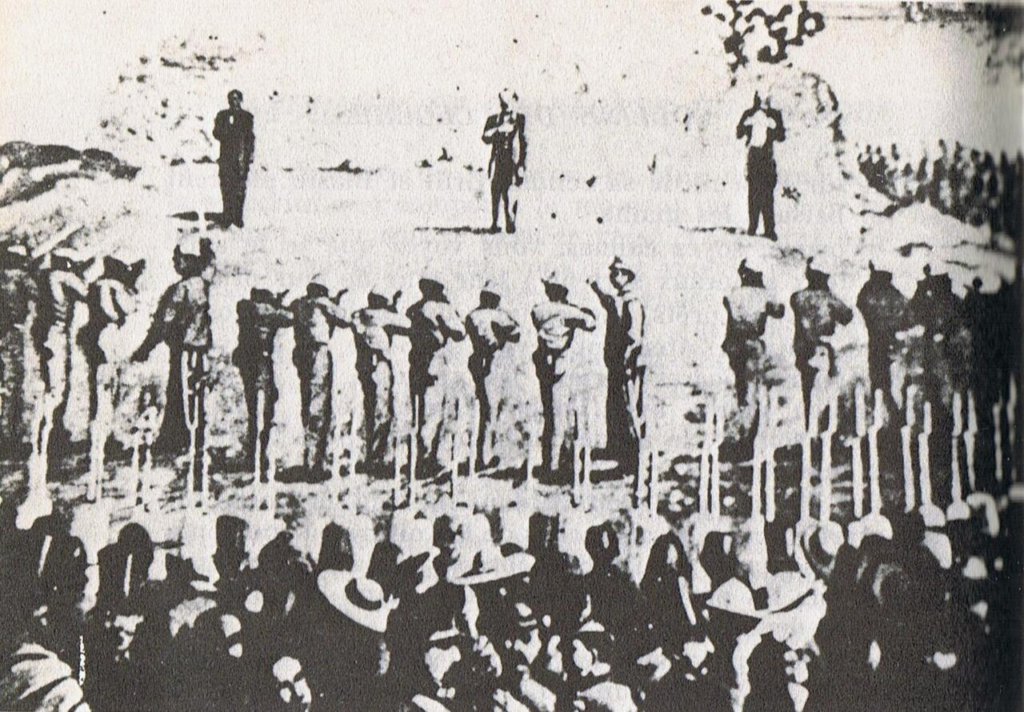

Just one month later, on 19 June of that year 1867, Maximilian would be shot in Querétaro.

Above: Photograph of the execution of Maximilian (right) and Generals Miramón (left) and Mejía (center) on 19 June 1867

Then Zorrilla poured out all his hatred against the Mexican liberals into a poem, as well as against those who had abandoned his friend:

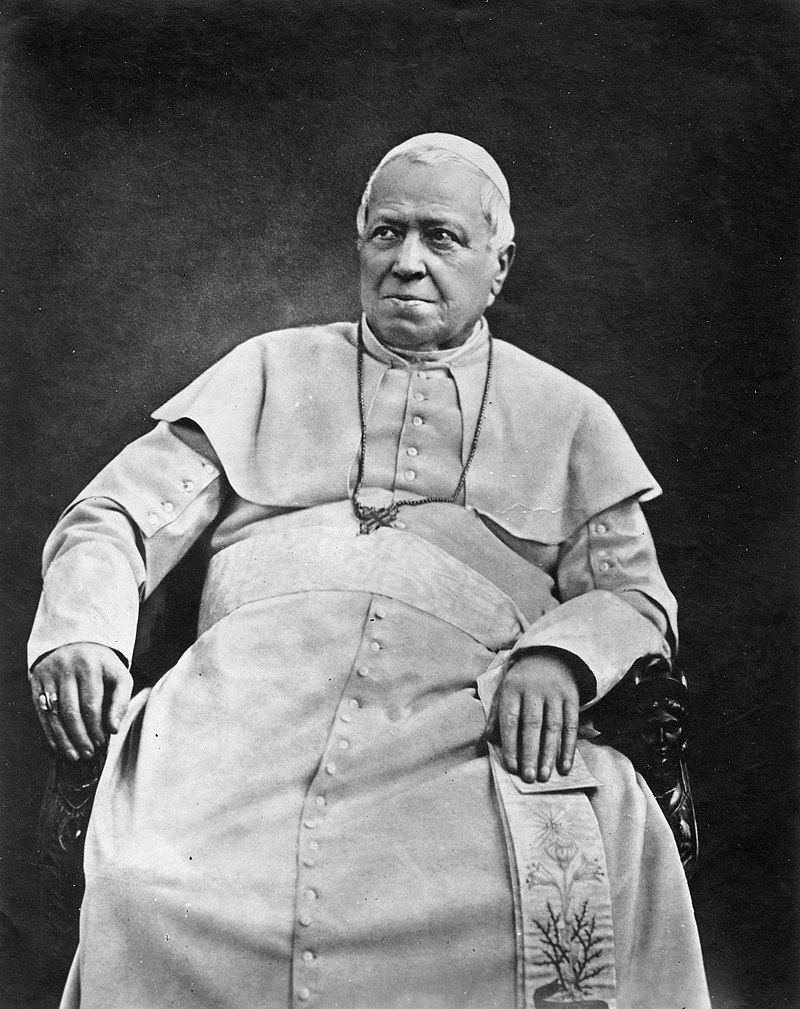

Napoleon III and Pope Pius IX.

Above: Italian Pope Pius IX (né Giovanni Maria Battista Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai Ferretti)(1792 – 1878)

This work is The Drama of the Soul.

From then on his religious faith suffered a hard blow.

He recovered by marrying again on 20 August 1869 in Barcelona:

Juana Pacheco Martín was 20 years old, he 52.

Zorrilla was a spendthrift and never knew how to manage himself:

Financial difficulties returned, from which neither public recitals of his work, nor a government commission in Rome, where he was with his wife between 1871 and 1873, nor a pension granted too late could get him out, although he received the protection of some figures in Spanish high society such as the Count of Guaqui.

Above: Images of Rome, Italy

Above: Spanish Count José Manuel de Goyemeche y Gamio (1831 – 1893)

Honors, however, rained down on him:

King Amadeo I granted him the Grand Cross of Charles III.

Above: Spanish King Amadeo I (1845 – 1890)

Zorrilla was appointed Chronicler of Valladolid (1884) and was crowned with laurels as a national poet in Granada in 1889.

Above: Alhambra, Granada, Andalusia, Spain

Tired of his research for the Spanish government in Rome, at the beginning of 1874 he decided to move to France, where, in the region of Las Landes, he set up a house and dedicated himself, together with his wife, to floriculture.

Above: Flag of the Département Landes, France

They spent two years there until December 1876 when Zorrilla and his wife were forced to return to Spain, where he returned to work giving public readings of his works.

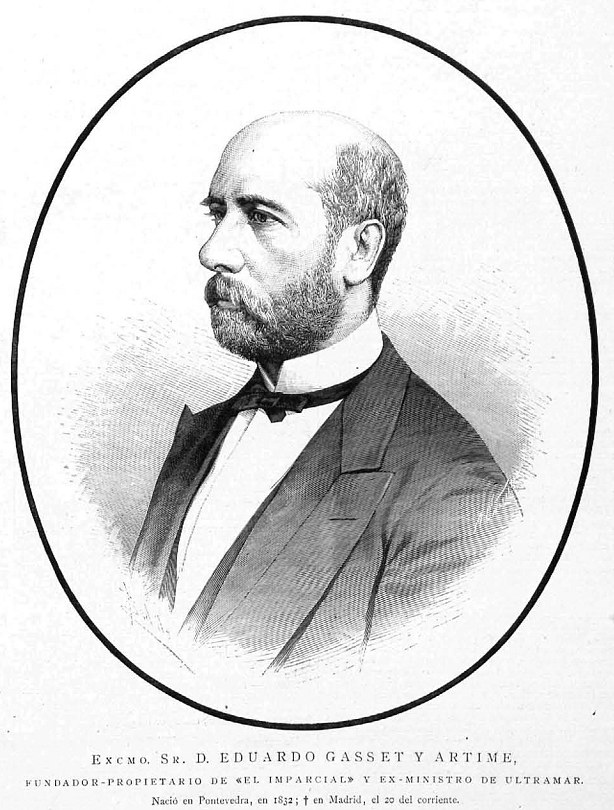

Eduardo Gasset, editor of El Imparcial, offered to print his memoirs, Recuerdos del tiempo viejo, in installments, in its Monday supplement, and began publication on 6 October 1879.

Above: Spanish journalist Eduardo Gasset (1832 – 1884)

Zorrilla spent the years 1880 to 1882 traveling and reading throughout Spain, awaiting a promised government pension that never arrived.

In 1883, he embarked on another exhausting tour:

He was 66 years old.

He wrote:

“I don’t have an hour to rest.

Hoarse, tired, and sleep-deprived, I wander around like an old crow.“

He opened the theater that bears his name in Valladolid in 1884.

He resettled there again until April 1889, but always touring.

In a letter to his great friend, the poet José Velarde, and speaking of himself in the 3rd person, Zorrilla described his sad situation:

Zorrilla produced two or three literary works, which under the titles of Zapatero y el rey, Sancho García and Don Juan Tenorio, entered into circulation capitalized at 10 to 12 thousand reales each.

Zorrilla produced these literary works before the promulgation of the theatrical property law, that is, before 1847, and sold them as such things were then sold, each of which legally yielded its purchasers 30, 40, and 50 thousand duros.

Now, since the law has no retroactive effect, since it does not accord the enormous injury to works of genius, Zorrilla supports all the comedians and impresarios of Spain and America during the first fortnight of November with Don Juan Tenorio, and is liable, if by God’s curse he reaches decrepitude, to die in the hospital or in the asylum, or to beg for alms in those days when his work supports so many.

And his friends say to the legislators:

“Since the law cannot protect Zorrilla by forcing those who legally bought his works to share his enormous profits with him, do not let the one who created these capitals with such works and maintains so many businesses die of hunger in old age.”

(J. Zorrilla, Letter to José Velarde, 19 December 1881)

Above: Spanish poet José Velarde (1848 – 1892)

Zorrilla was always poor, especially for the 12 years after 1871.

The publication of his autobiography, Recuerdos del tiempo viejo (Memories of the Old Days) in 1880, did nothing to alleviate his poverty.

Though his plays were still being performed, he received no money from them.

Finally, in his old age, critics began to reappraise his work, and brought him new fame.

He received a pension of 30,000 reales, a gold medal of honor from the Spanish Academy, and, in 1889, the title of National Laureate.

On 14 February 1890, he underwent surgery in Madrid to remove a brain tumor.

Queen Maria Cristina quickly granted him a pension two months later.

However, the tumor recurred.

He died in Madrid on 23 January 1893 following another operation.

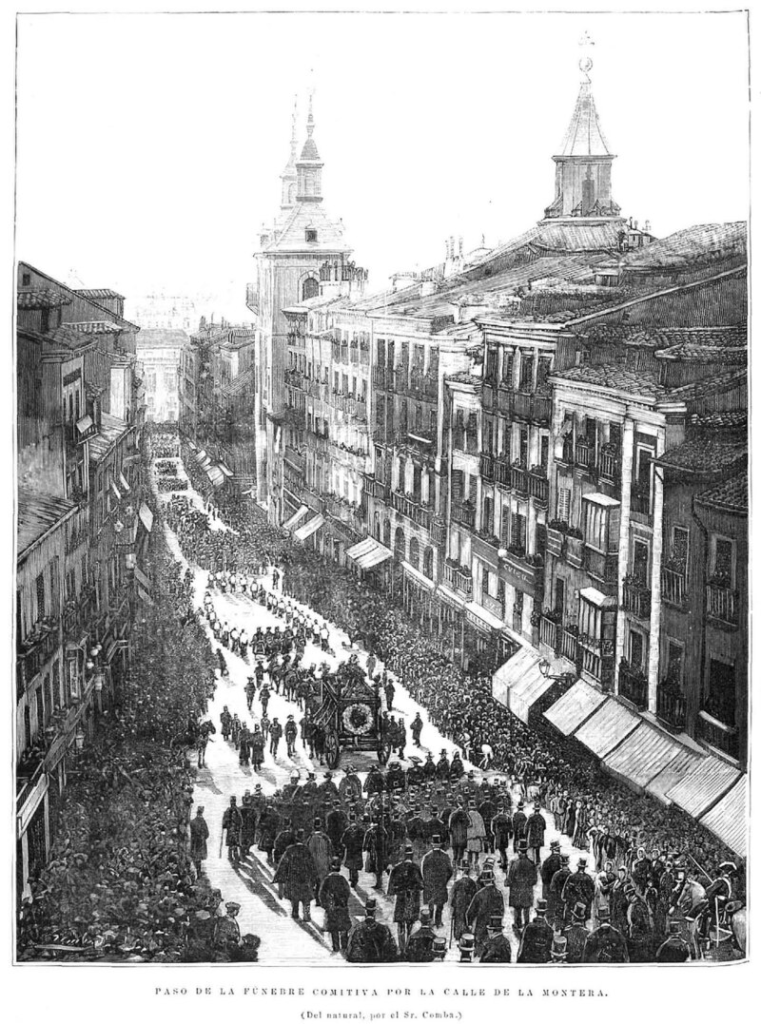

Above: Zorrilla’s funeral procession, 30 January 1893

His remains were buried in the San Justo Cemetery in Madrid, but in 1896, in compliance with the poet’s wishes, they were transferred to

Valladolid.

They are currently housed in the Pantheon of Illustrious Valladolid Citizens in the Carmen Cemetery.

Above: José Zorrilla Monument, Valladolid, Spain

Zorrilla cultivated all genres of verse:

Lyric poetry, epic or narrative, and drama.

There are three elements in Zorrilla’s life of great interest for understanding the direction of his work.

First, his relationship with his father.

A despotic and severe man, he systematically rejected his son’s affection, refusing to forgive his youthful mistakes.

The writer carried a kind of guilt complex.

To overcome it, he decided to defend in his work a traditionalist and reactionary ideal that was very much in keeping with his father’s sentiments, but in contradiction with his own intimate progressive ideas.

He says in Memories of Old Times:

“My father had not valued my verses at all, nor my conduct, the key to which only he held.“

Secondly, we must highlight his sensual temperament, which drew him toward women:

Two wives, an early love affair with a cousin, and various other affairs in Paris and Mexico provide a list that, although very different from that of Don Juan, moves in the same direction.

Love constitutes one of the fundamental axes of Zorrilla’s entire output.

It’s not idle to wonder, as a third conditioning factor, about Zorrilla’s health.

At a certain point in his life, in fact, he invented a double, a madman (Tales of a Madman)(1853), who appears almost obsessively later on.

In Memories of Old Times, his autobiography, he speaks of his fondness for the Tarot, his hallucinations, sleepwalking and epilepsy.

When did the brain tumor appear and how did it affect his behavior?

Perhaps the predominant role of fantasy in the writer and his enormous sense of mystery (the principle of the sublime in Romantic aesthetics) find an explanation in this regard.

His biographer, Narciso Alonso Cortés, has described his character as childlike, kind-hearted, a friend to all, ignorant of the value of money, and unaware of politics.

It is also worth highlighting Zorrilla’s independence, of which he was very proud.

In verses reminiscent of those of Antonio Machado, he confessed that he owed everything to his work and even rejected lucrative public positions because he felt unprepared.

In his Memories of Old Times, he stated:

“I fear that our revolution will be fruitless for Spain because all Spaniards believe we are good and capable of everything, and we all get involved in things we don’t know.”

Indeed, in his work, there are concerns that occasionally emerge despite the traditionalism he imposed on himself so as not to offend his father.

For example, in his poem Toledo, the poet does not hide the national decline after a glorious past.

Zorrilla’s style is characterized by great plasticity and musicality and a powerful sense of mystery and tradition.

He also uses old turns of phrase and oaths.

His metrics are very rich and in general each of his works is polymetric.

In the rest, traditional meters and stanzas predominate.

In Spanish Romanticism, he represents the moment of the nationalization of its imported elements.

His work is uneven, sometimes very inspired and other times verbose and lacking in concreteness:

In any case, it is always proudly spontaneous, free and easy:

Because in works of taste and whim

That bring only pleasure and no profit,

Everything can be done if it is well done

And can be said if it is well said.

Above: José Zorrilla

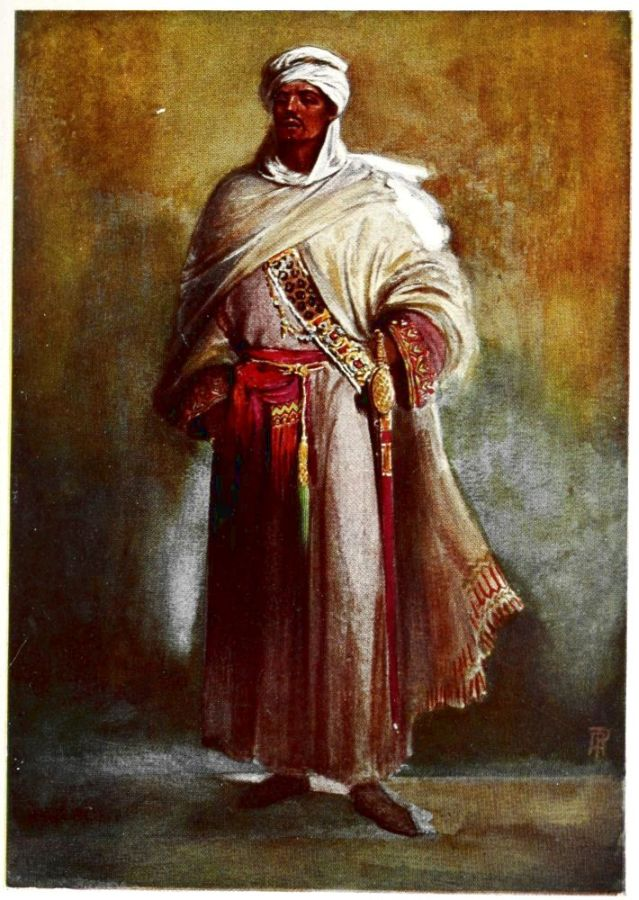

Among his early lyric poems, the well-known Orientales stand out, a genre already cultivated by Victor Hugo.

Much better are Leyendas, in which he proves to be a better narrative poet than a lyric poet, skillfully combining intrigue, surprise, and mystery.

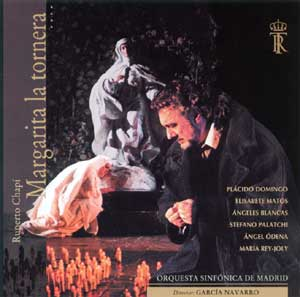

His most famous works were Margarita la tornera (Margarita the turner), A buen juez mejor testigo (A good judge makes a better witness) and El capitán Montoya.

At the age of 35, he published Granada (1852), a brilliant evocation of the Muslim world.

Based on their themes, we can establish five sections:

- Religious lyrics (Wrath of God, The Virgin at the foot of the Cross)

- Love lyrics (A memory and a sigh, To a woman)

- Sentimental lyrics (Meditation, The January Moon)

- Descriptive lyrics (Toledo, To a tower)

- Philosophical Lyrics (Tales of a Madman)

His extensive dramatic work includes three fundamental pieces:

The Shoemaker and the King, Don Juan Tenorio and Traitor, Unconfessed and Martyr.

In The Shoemaker and the King (1840-1841) Don Pedro the Cruel is portrayed from the perspective of popular tradition, as a sympathetic and just character whom fate leads to disaster.

In Don Juan Tenorio (1844), the character of the trickster, created by Tirso de Molina and featured in Antonio de Zamora’s Tan largo me lo fiáis, which had been performed as a morality play on All Souls’ Day for nearly a century and a half, is revived.

Zorrilla’s play was so successful that it replaced it in this tradition.

He introduced various innovations that greatly improved the dramatic structure:

He introduced the figures of Doña Inés, Don Luis Mejía and the salvation through love of the idealized Doña Inés, rather than the traditional condemnation of the impetuous Don Juan.

Although Tenorio abounds in carelessness, childish effects and bursts of lyricism that border on sentimentality, Zorrilla saves everything with the vigor of his theatricality, his fluid command of versification, his mastery in the conduction of the action, the firmness of his characters and his unsurpassed sense of mystery.

Zorrilla himself was not very happy with his work, which he criticized mercilessly in his memoirs, but critics have to admit that next to its dramatic virtues its defects seem trivial and are barely noticeable.

As for Traidor, inconfeso y mártir (1849), a maximum balance is achieved, although the author modifies historical reality by making “the pastry chef of Madrigal” who was hanged for having tried to impersonate King Sebastian of Portugal, who disappeared in the Battle of Alcazarquivir, be, in effect, the same monarch.

In his early years, Zorrilla was known as an extraordinarily fast writer.

He claimed he wrote El Caballo del Rey Don Sancho (The King’s horse, Don Sancho) in three weeks, and that he put together El Puñal del Godo (The dagger of the Goth) in two days.

This may account for some of the technical faults — redundancy and verbosity — in his works.

His plays often appeal to Spanish patriotic pride, and actors and audiences have enjoyed his effective dramaturgy.

Above: Flag of Spain

Don Juan Tenorio is his best-known work.

In the first part of the drama, the protagonist is still the demonic rake described by de Molina (he is called a demon and even Satan himself on more than one occasion).

The story begins with Don Juan meeting Don Luis in a crowded wine shop in Seville so that the two can find out which of them has won the bet that they made one year ago:

Each expected himself to be able to conquer more women and kill more men than the other.

Naturally, Don Juan wins on both counts.

People in the crowd ask him if he is not afraid that someday there will be consequences for his actions, but Don Juan replies that he only thinks about the present.

It is then revealed that both caballeros have gotten engaged since they last met, Don Luis to Doña Ana de Pantoja and Don Juan to Doña Inés de Ulloa.

Don Luis, his pride hurt, admits that Don Juan has slept with every woman on the social ladder from princess to pauper, but is lacking one conquest:

A novice about to take her holy vows.

Don Juan agrees to the new bet and doubles it by saying that he will seduce a novice and an engaged woman, boasting that he only needs six days to complete the task with Don Luis’s fiancée as one of the intended conquests.

At this point, Don Gonzalo, Don Juan’s future father-in-law, who has been sitting in a corner during this entire exchange, declares that Don Juan will never come near his daughter and the wedding is off.

Don Juan laughs and tells the man that he will either give Doña Inés to him, or he will take her.

He now has the second part of the bet concreted with Doña Inés set to take her vows.

In following scenes, Don Juan manages, through charisma, luck and bribery, to fulfill both terms of the bet in less than one night.

However, he does not seduce the saintly Doña Inés.

He just takes her from the convent where she had been cloistered and brings her to his mansion outside the city.

There is a very tender love scene in which each professes to love the other, and it seems that, for once, Don Juan does feel something more than lust for Doña Inés.

Unfortunately, Don Luis arrives to demand a duel with Don Juan for having seduced Doña Ana while pretending to be her fiancé.

Before they can fight, Don Gonzalo shows up with the town guardsmen and accuses Don Juan of kidnapping and seducing his daughter.

Don Juan kneels and begs Don Gonzalo to let him marry Doña Inés, saying he worships her and would do anything for her.

Don Luis and Don Gonzalo mock him for his perceived cowardice and continue to demand his life.

Don Juan declares that, since they have rejected him in his attempts to become a good person, he will go on being a devil.

He shoots Don Gonzalo, stabs Don Luis in a duel, and flees the country, abandoning the now fatherless Doña Inés.

The second part begins after five years have passed.

Don Juan returns to Seville.

Upon coming to the place where his father’s mansion used to be which was turned into a pantheon, he discovers that the building was torn down and a cemetery built in its place.

Lifelike statues of Don Gonzalo, Don Luis and Doña Inés stand over the tombs.

The sculptor, who has just finished his work when Don Juan arrives, tells him that Don Diego Tenorio, Don Juan’s father, had disowned his son and used his inheritance to build this memorial to his victims.

Don Juan also finds out that Doña Inés died of sorrow not long after being abandoned.

The protagonist is clearly at least a bit repentant of what he has done, expressing regret to the statues and praying to Doña Inés for forgiveness.

As he prays, the statue of Doña Inés comes to life and tells him that he only has one day to live, in which he must decide what his fate will be.

Inés is speaking from Purgatory, having made a deal with God to offer her own blameless soul on behalf of Don Juan’s.

God therefore agreed that their two souls would be bound together eternally, so Don Juan must choose either salvation or damnation for both himself and Doña Inés.

Then, two of Don Juan’s old friends, Centellas and Avellaneda, show up.

Don Juan convinces himself that he hadn’t truly seen a ghost at all.

In order to prove his bravado, he heretically invites Don Gonzalo’s statue to dinner that evening.

Don Juan goes on blaspheming against Heaven and the dead throughout the following scenes, until Don Gonzalo’s statue really does show up at supper.

Don Juan manages to remain largely nonchalant, although both of his other guests pass out, as Don Gonzalo tells him once more that his time is running out.

When Avellaneda and Centellas wake up, Don Juan accuses them of having contrived this show to make fun of him.

Offended, they accuse him of having drugged their drinks to mock them.

They end up in a swordfight.

Don Juan is back in the cemetery, led there by Don Gonzalo’s ghost.

Don Gonzalo’s tomb opens and reveals an hourglass that represents Don Juan’s life.

It has almost run out.

Don Gonzalo says that Centellas already killed don Juan in the duel.

He then takes Don Juan’s arm to lead him into Hell.

Don Juan protests that he isn’t dead and reaches out to Heaven for mercy.

Doña Inés appears and redeems him.

The two go to Heaven together.

It has become a tradition of both Spanish and Mexican theater to perform Don Juan Tenorio on All Saints Day or its Mexican equivalent the Day of the Dead, so the play has been performed at least once every year for over a century.

It is also one of the most lucrative plays in Spanish history.

Unfortunately, the author did not benefit from his play’s success:

Not long after he finished writing it, Zorrilla sold the rights to the play, since he did not expect it to be much more successful than any of his other works.

Aside from the price paid for the rights, Zorrilla never made any money from any of the productions.

Later, he wrote biting criticisms of the work in an apparent attempt to get it discontinued long enough for him to revise it and market the second version himself.

However, the ploy never succeeded.

This is Ruiz’s version of Don Juan, because he believed a story can never end sadly, and must always have a happy ending.

The House of Zorrilla in Valladolid is the building where the

romantic poet was born on 21 February 1817.

This was a house rented by José Zorrilla’s parents to the Marquis of Revilla.

It is located on Fray Luis de Granada Street.

Zorrilla lived there for the first seven years of his life and briefly upon his return to Valladolid in 1866 after his return from Mexico.

After his death, the Valladolid City Council decided to acquire the building to honor the poet’s memory, converting it into a house museum.

Above: Casa Museo José Zorrilla, Valladolid, Spain

The ground floor was converted into a library thanks to the work of Narciso Alonso Cortés, a prominent scholar of José Zorrilla’s work.

In 1895, a commemorative plaque was placed on the façade with a bust of the poet, the work of sculptor Pastor Valsero, bearing the inscription:

The eminent poet D. José Zorrilla was born herein 1817.

Above: Casa Museo José Zorrilla, Valladolid, Spain

The house is simple in appearance and structure, consisting of two floors, a basement, and a garden.

Above: Casa Museo José Zorrilla, Valladolid, Spain

It houses some of the poet’s original furniture, such as his desk, which was donated by his widow.

Above: Casa Museo José Zorrilla, Valladolid, Spain

The house’s furnishings are intended to capture the atmosphere of the poet’s life.

Among the paintings that decorate the walls of the main floor are:

- a large painting entitled Arrival at the Camp by Ruiz de Valdivia from Granada, depicting a scene from the Carlist War

- View of Seville, attributed to the painter Rafael Romero Barros

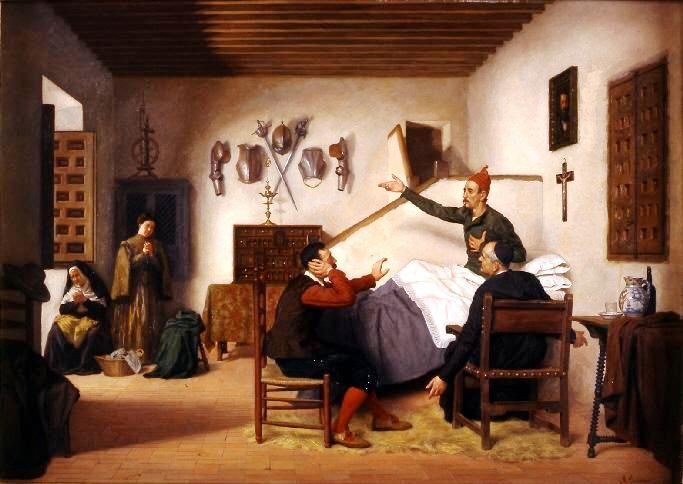

- Don Quixote Sick by Miguel Jadraque from Valladolid, painted in 1905

Above: Don Quijote enfermo, Miguel Jadraque (1905)

- a portrait of the poet painted by Ángel Díaz Sánchez

- another canvas showing the exterior appearance of the Church of La Antigua before restoration, painted in 1876 by Santos Tordesillas.

Among Zorrilla’s personal mementos is the funerary mask that sculptor Aurelio Rodríguez-Vicente Carretero obtained from his face and used to create the monument to the poet that stands in Valladolid’s Plaza de Zorrilla.

Above: Casa Museo José Zorrilla, Valladolid, Spain

José Zorrilla captured the intensity of emotion and the theatricality of the human soul.

His most famous work, Don Juan Tenorio, transformed the legendary seducer into a tragic and poetic figure, a man consumed by love, guilt, and fate.

Unlike earlier depictions of Don Juan as a callous libertine, Zorrilla infused him with a soul capable of redemption, blending passion and drama with moral introspection.

Zorrilla’s work endures because it taps into the timeless themes of love and consequence, the exhilaration of passion tempered by the weight of morality.

His poetry reminds us that life itself is a stage upon which we perform, often without fully understanding the script written for us by fate, society, or our own desires.

Above: José Zorrilla

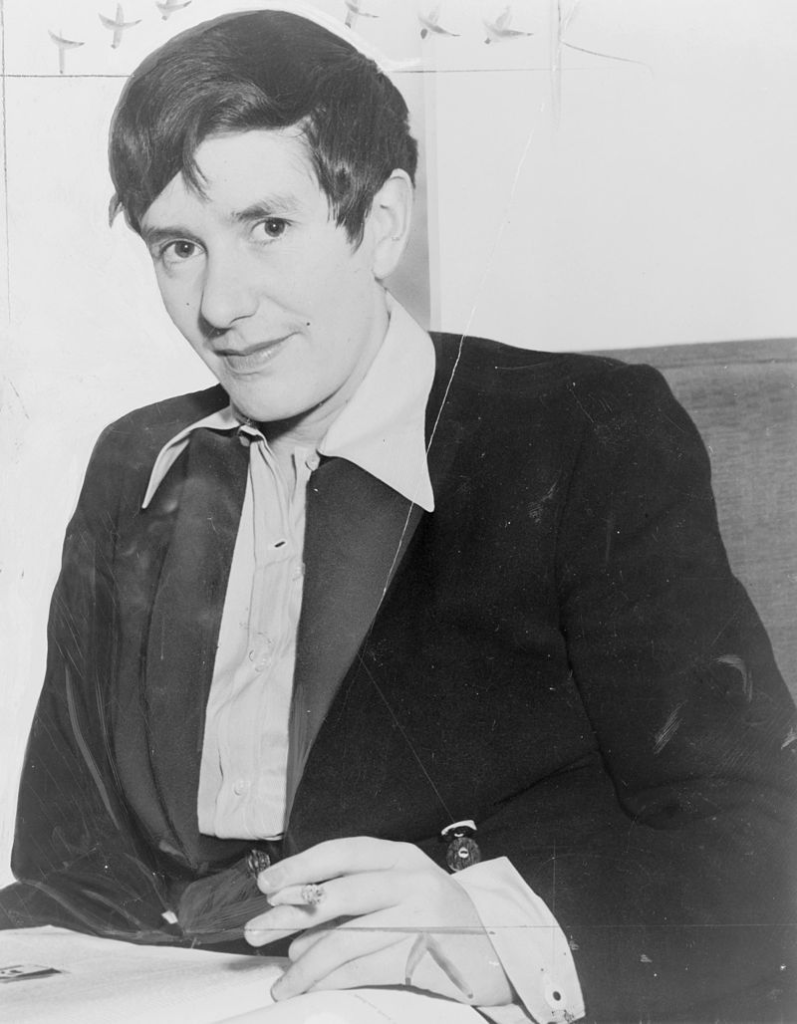

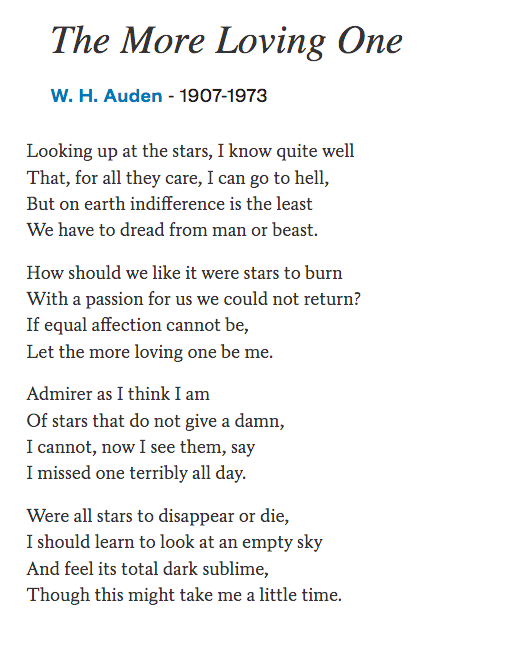

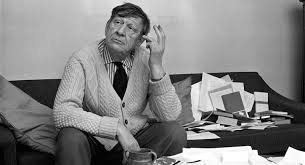

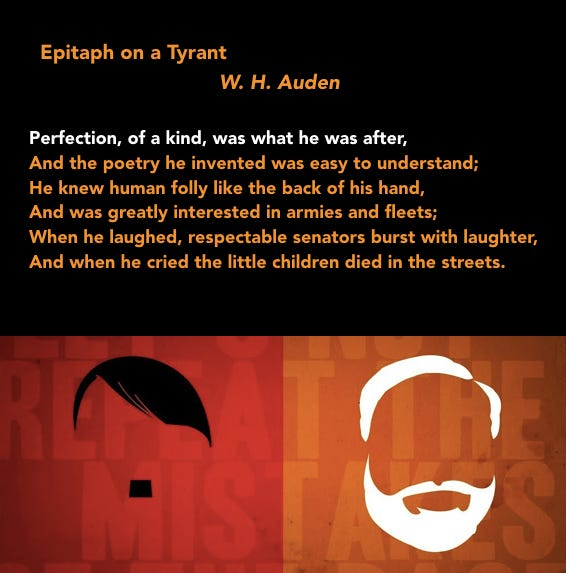

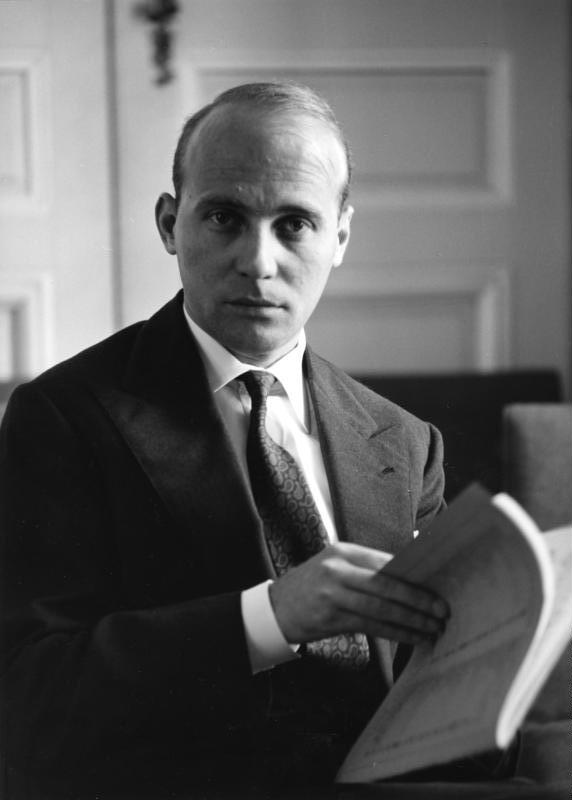

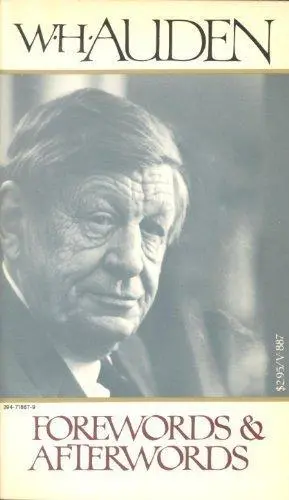

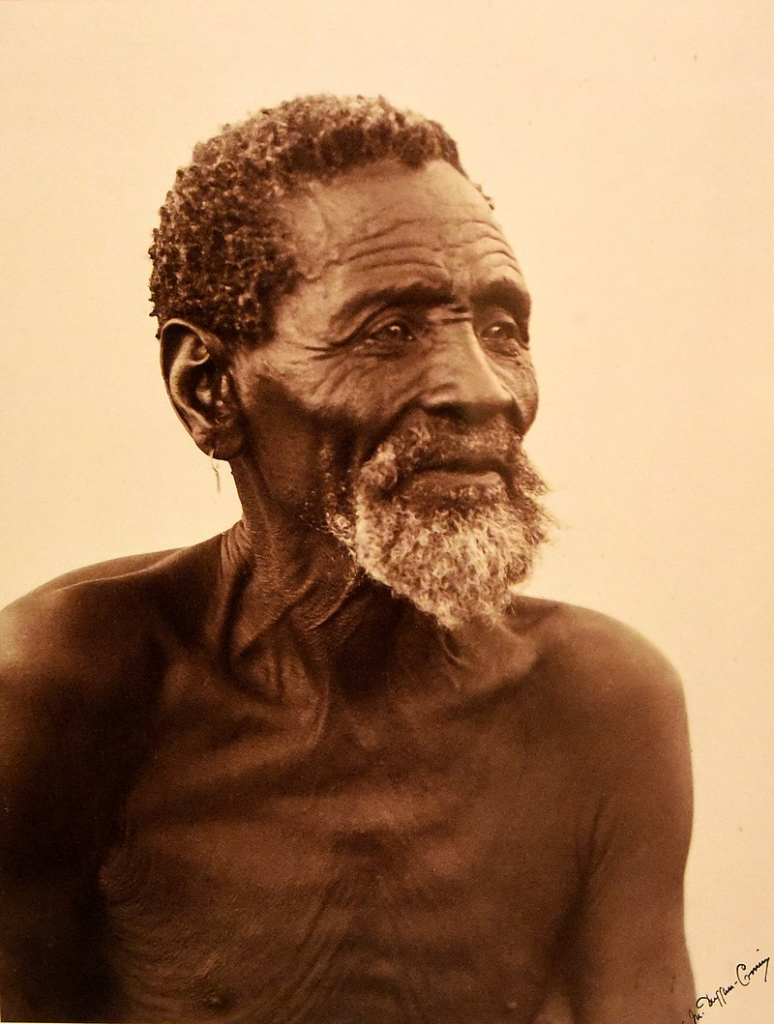

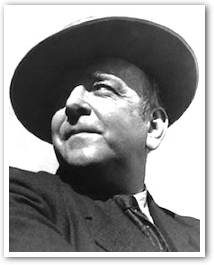

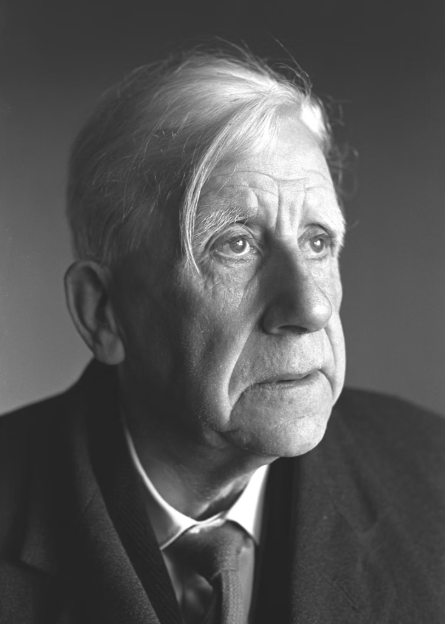

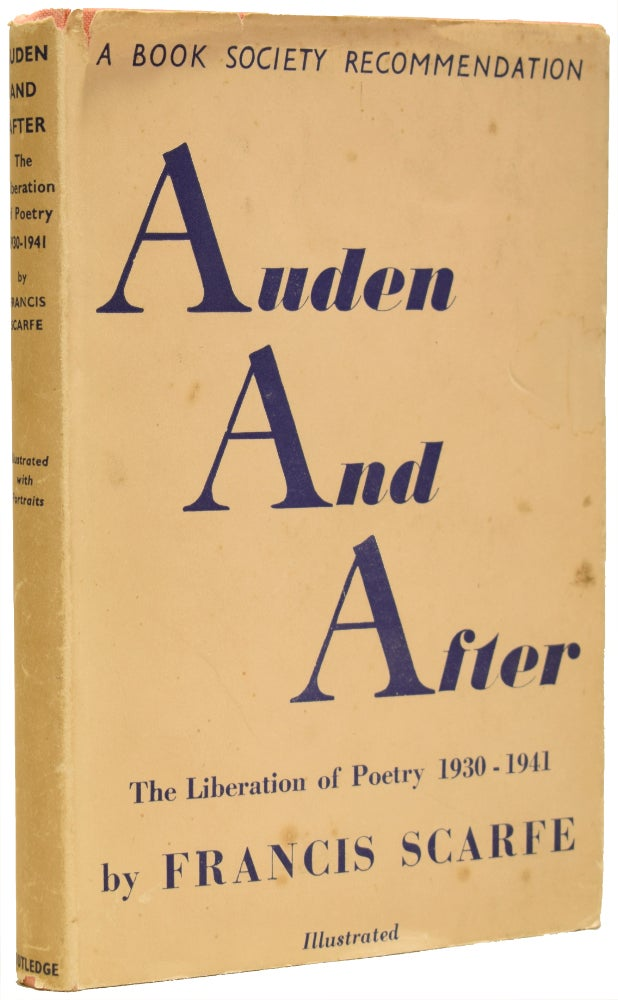

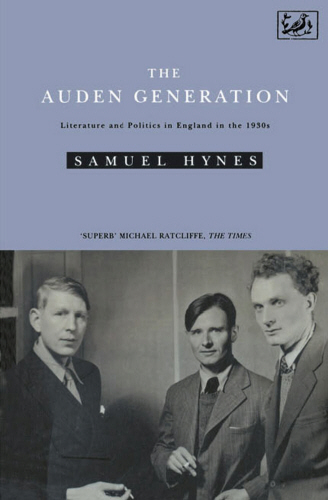

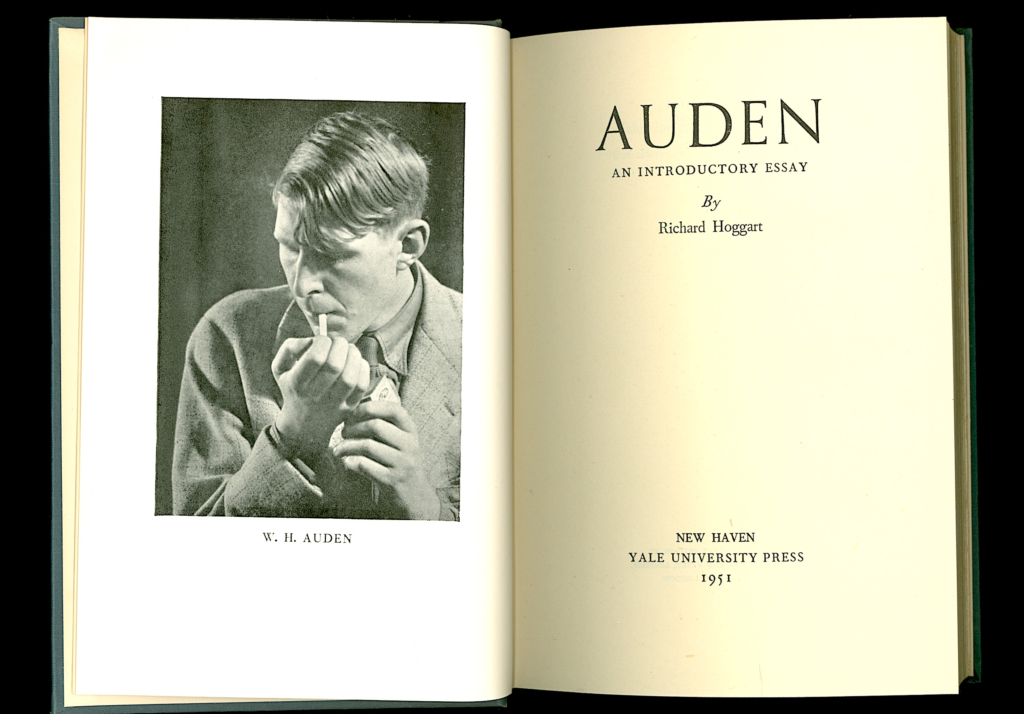

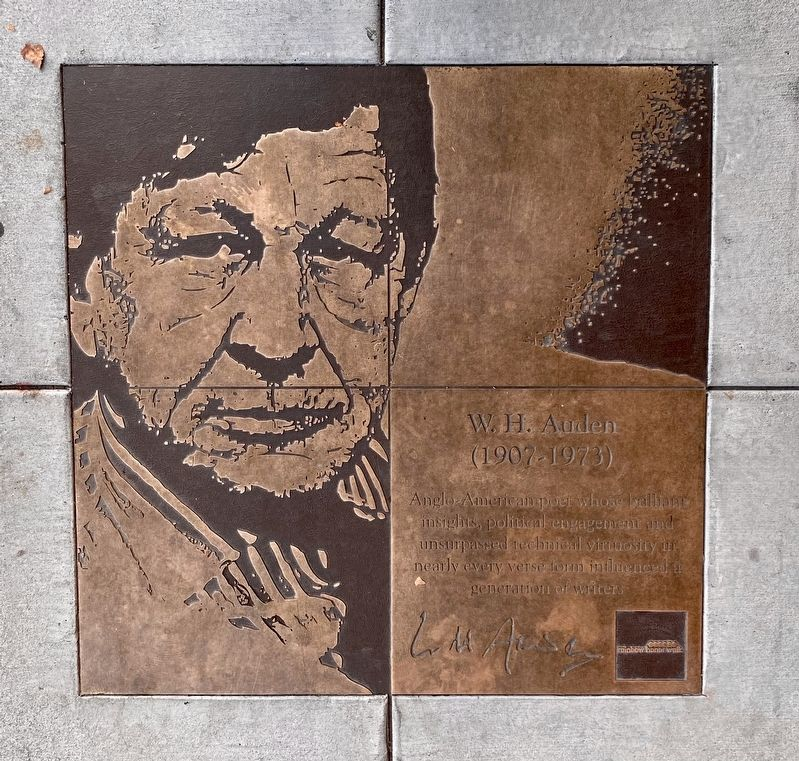

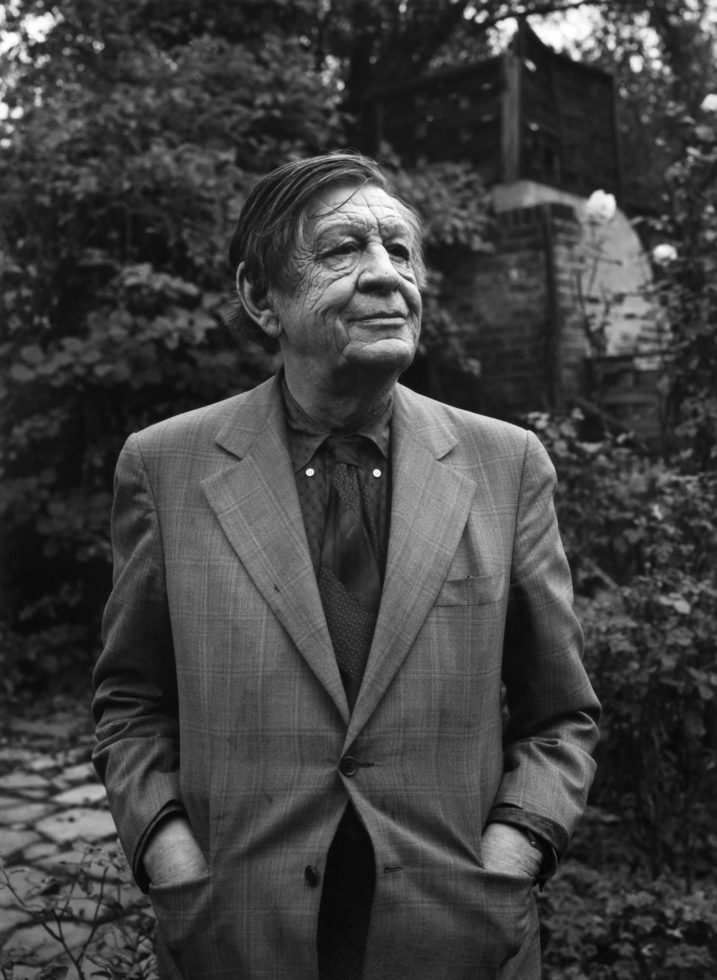

Wystan Hugh Auden (21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British – American poet.

Auden’s poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love and religion, and its variety in tone, form and content.

Some of his best known poems are about love, such as “Funeral Blues“, on political and social themes, such as “September 1, 1939” and “The Shield of Achilles“, on cultural and psychological themes, such as The Age of Anxiety, and on religious themes, such as “For the Time Being” and “Horae Canonicae“.

Above: W. H. Auden

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone.

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the woods;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Funeral Blues (1936)

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odor of death

Offends the September night.

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish.

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

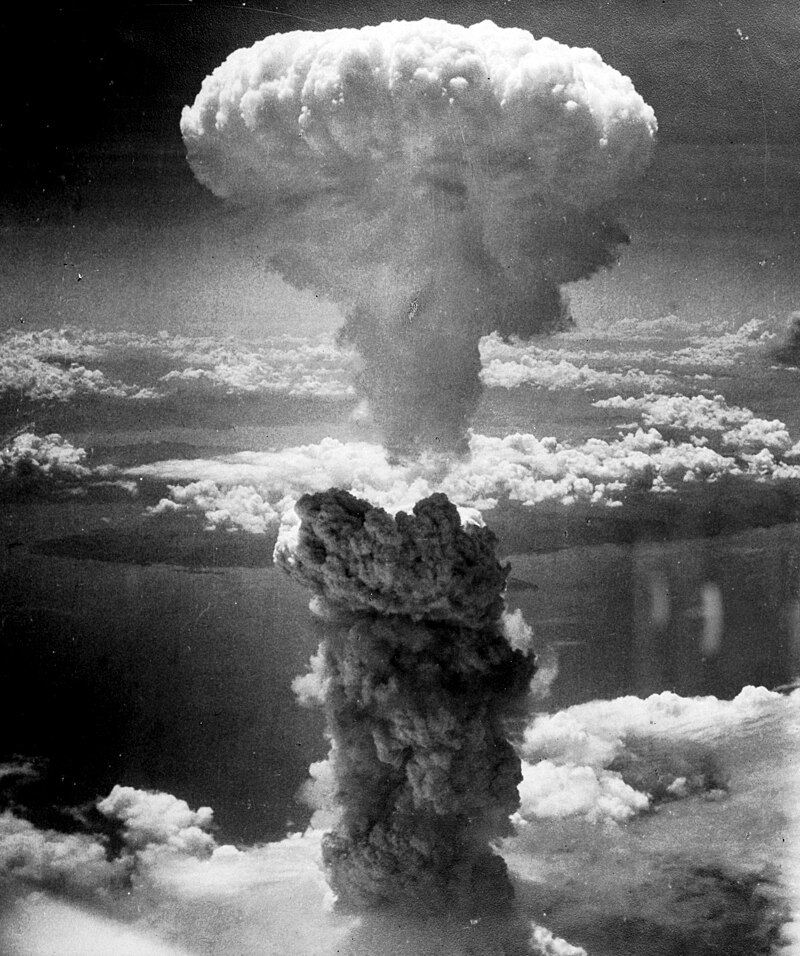

September 1, 1939 (1939)

Above: German dictator Adolf Hitler observes German soldiers marching into Poland, 1 September 1939

Let us then

Consider rather the incessant Now of

The traveler through time, his tired mind

Biased towards bigness since his body must

Exaggerate to exist, possessed by hope…

We would rather be ruined than changed

We would rather die in our dread

Than climb the cross of the moment

And let our illusions die.

The Age of Anxiety (1948)

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign.

Out of the air a voice without a face

Proved by statistics that some cause was just

In tones as dry and level as the place:

No one was cheered and nothing was discussed…

A crowd of ordinary decent folk

Watched from without and neither moved nor spoke

As three pale figures were led forth and bound

To three posts driven upright in the ground.

The mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes like to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy: a bird

Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third,

Were axioms to him, who’d never heard

Of any world where promises were kept

Or one could weep because another wept.

The thin-lipped armorer,

Hephaestos, hobbled away,

Thetis of the shining breasts

Cried out in dismay

At what the god had wrought

To please her son, the strong

Iron-hearted man-slaying Achilles

Who would not live long.

The Shield of Achilles (1952)

Auden was born in York.

Above: Images of York, North Yorkshire, England

Auden grew up in and near Birmingham in a professional, middle-class family.

Above: Birmingham, West Midlands, England

Auden attended various English independent (or public) schools and studied English at Christ Church, Oxford.

Above: Christ Church, University of Oxford, England

After a few months in Berlin in 1928 – 1929, Auden spent five years (1930 – 1935) teaching in British private preparatory schools.

Above: Berlin, Germany

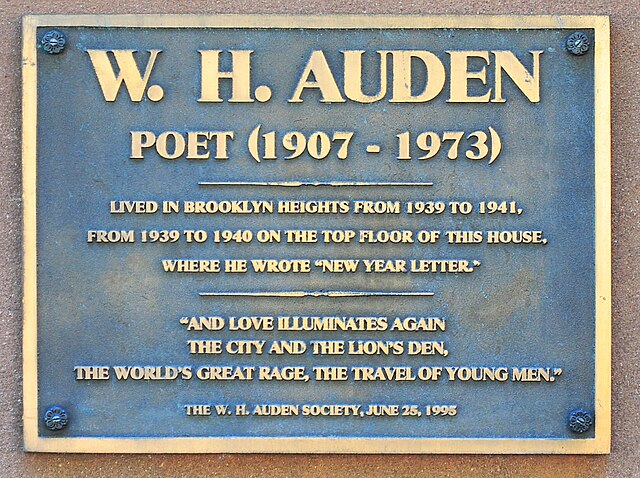

In 1939, Auden moved to the United States.

He became an American citizen in 1946, retaining his British citizenship.

Auden taught from 1941 to 1945 in American universities, followed by occasional visiting professorships in the 1950s.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

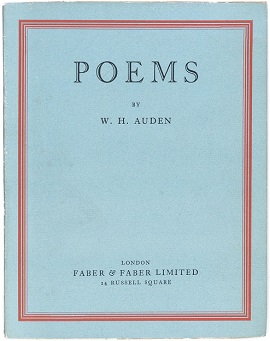

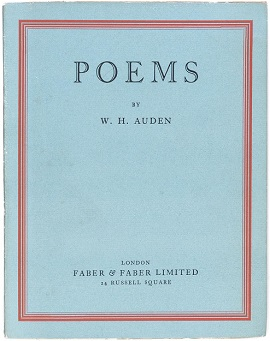

Auden came to wide public attention in 1930 with his first book, Poems.

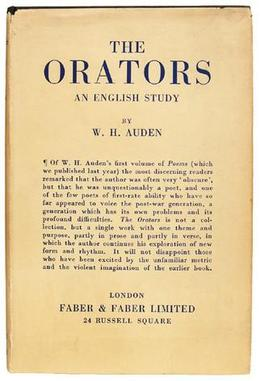

It was followed in 1932 by The Orators.

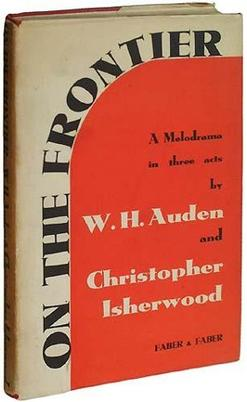

Three plays written in collaboration with Christopher Isherwood between 1935 and 1938 built his reputation as a left-wing political writer.

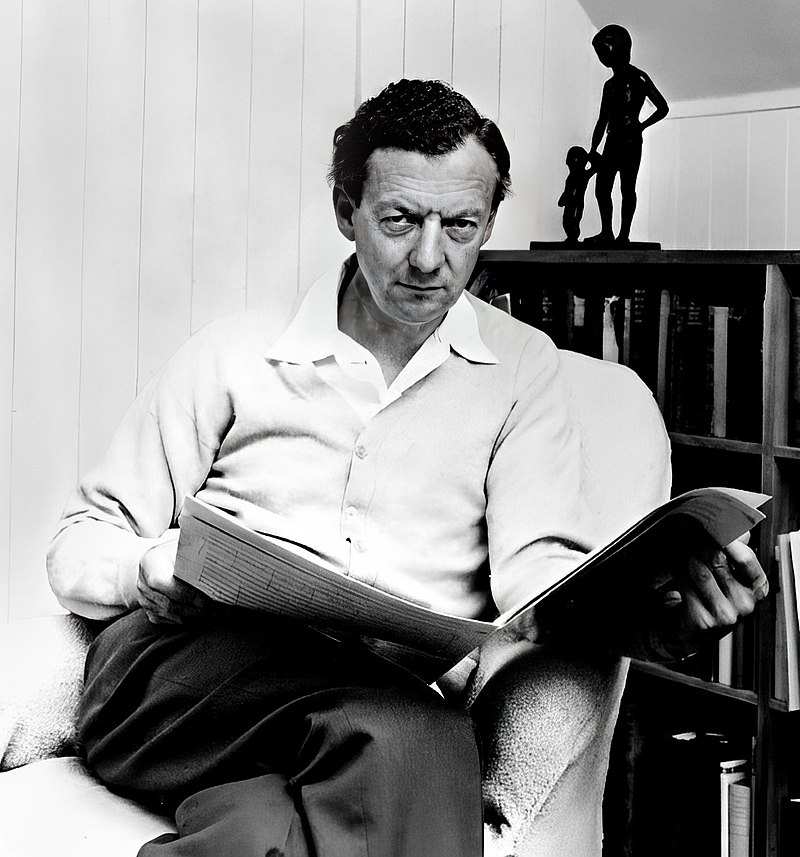

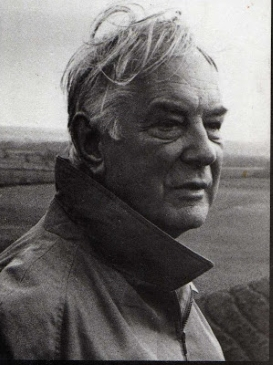

Above: English writer Christopher Isherwood (1904 – 1986)

Auden moved to the United States partly to escape this reputation, and his work in the 1940s, including the long poems “For the Time Being” and “The Sea and the Mirror“, focused on religious themes.

Auden won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his 1947 long poem The Age of Anxiety, the title of which became a popular phrase describing the modern era.

Above: Medallion of the Pulitzer Prize

From 1956 to 1961, Auden was Professor of Poetry at Oxford.

Above: Coat of arms of the University of Oxford

Auden’s lectures were popular with students and faculty and served as the basis for his 1962 prose collection The Dyer’s Hand.

Auden was a prolific writer of prose essays and reviews on literary, political, psychological and religious subjects.

He worked at various times on documentary films, poetic plays, and other forms of performance.

Throughout his career he was both controversial and influential.

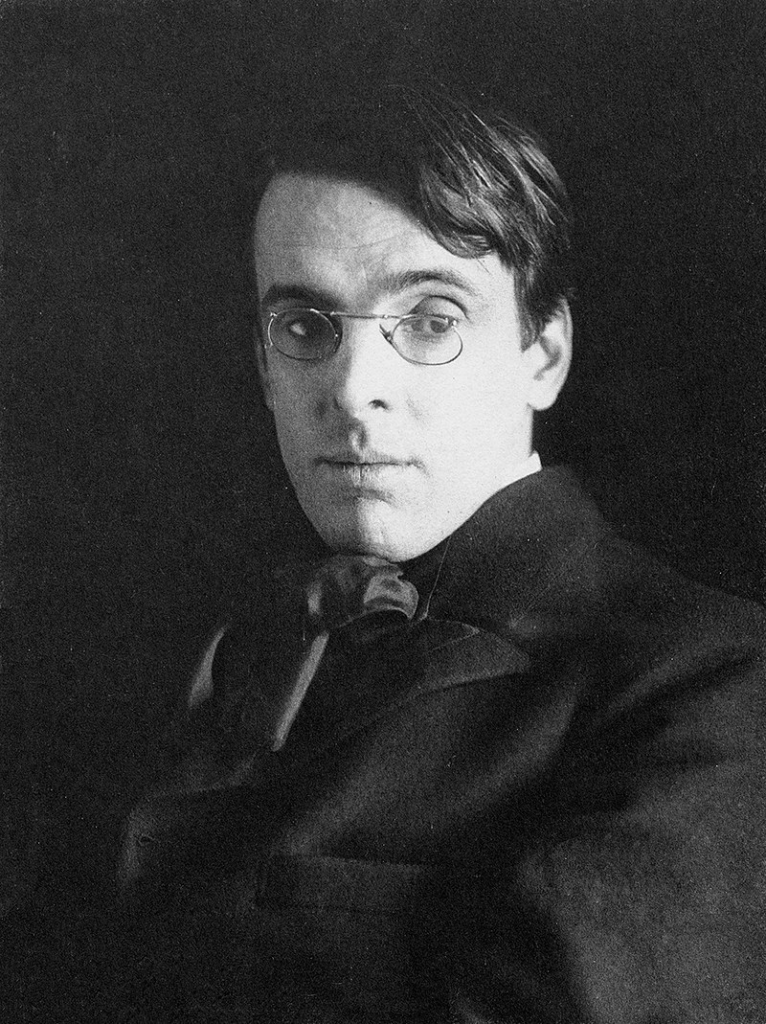

Critical views on his work ranged from sharply dismissive (treating him as a lesser figure than W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot) to strongly affirmative (as in Joseph Brodsky’s statement that he had “the greatest mind of the 20th century“).

After his death, his poems became known to a much wider public through films, broadcasts and popular media.

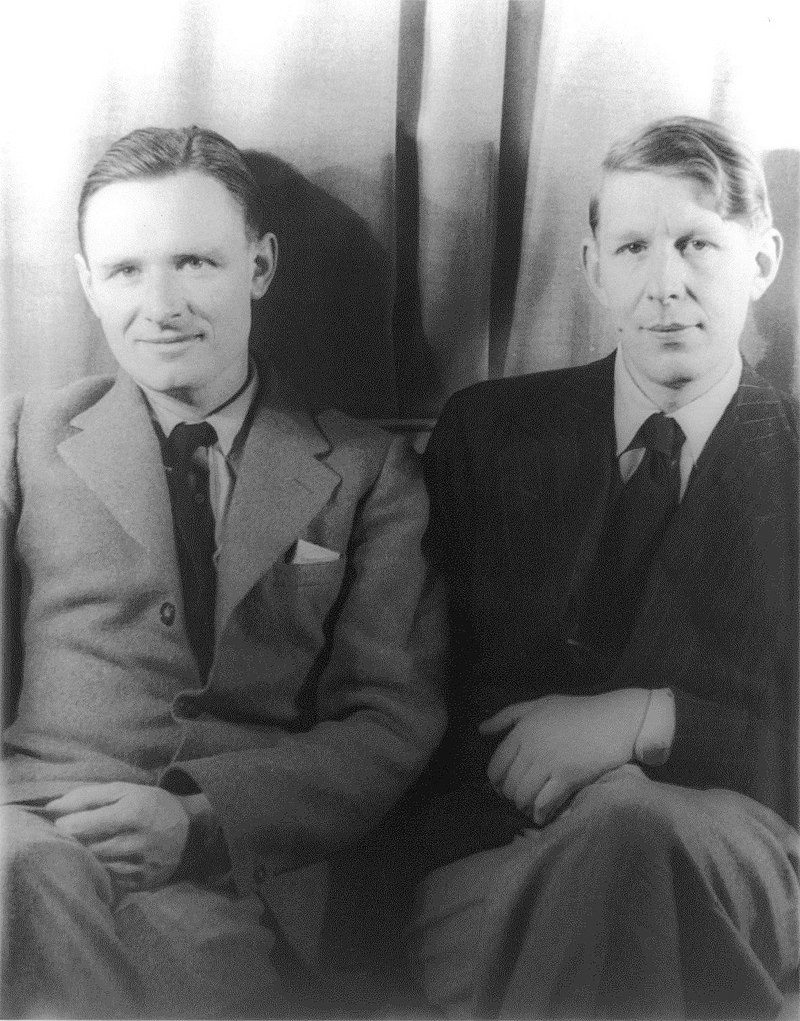

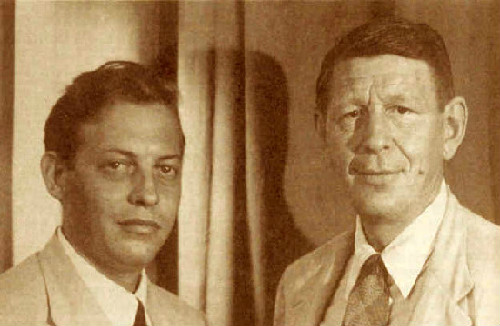

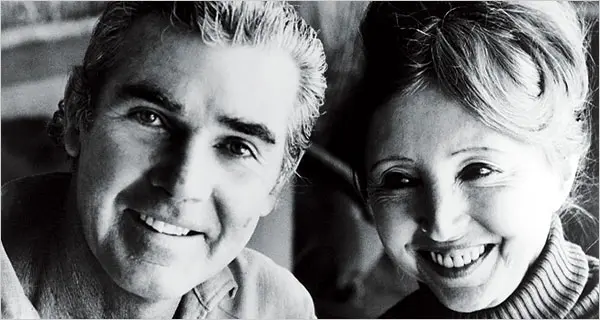

Above: Christopher Isherwood (left) and W. H. Auden (right), 6 February 1939

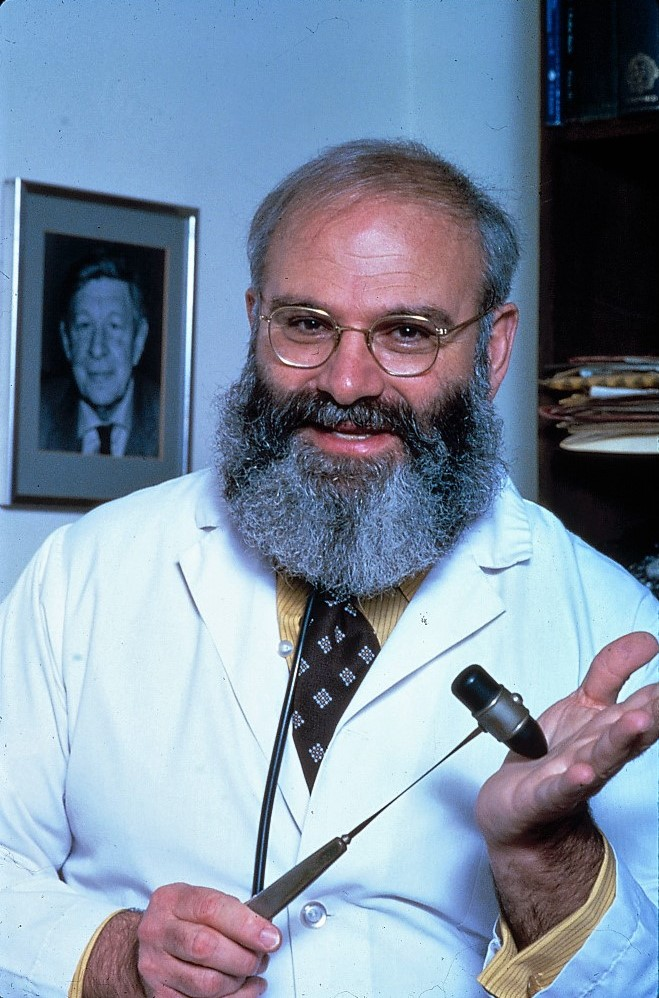

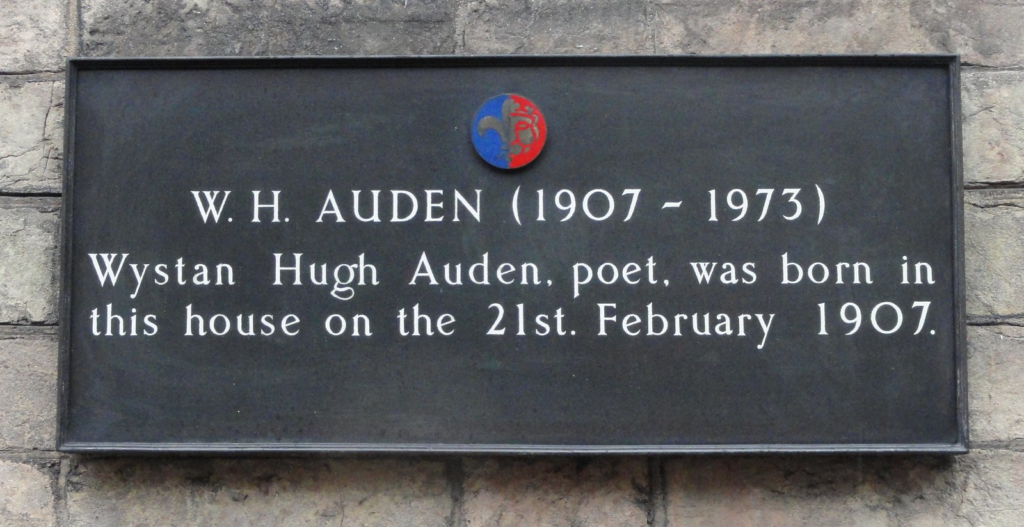

Auden was born at 54 Bootham, York, England, to George Augustus Auden (1872 – 1957), a physician, and Constance Rosalie Auden (née Bicknell; 1869 – 1941), who had trained (but never served) as a missionary nurse.

He was the 3rd of three sons.

The eldest, George Bernard Auden (1900 – 1978), became a farmer, while the second, John Bicknell Auden (1903 – 1991), became a geologist.

The Audens were minor gentry with a strong clerical tradition, originally of Rowley Regis, later of Horninglow, Staffordshire.

Auden, whose grandfathers were both Church of England clergymen, grew up in an Anglo-Catholic household that followed a “high” form of Anglicanism, with doctrine and ritual resembling those of Catholicism.

He traced his love of music and language partly to the church services of his childhood.

Above: Auden’s birthplace, York

He believed he was of Icelandic descent, and his lifelong fascination with Icelandic legends and Old Norse sagas is evident in his work.

Above: Flag of Iceland

His family moved to Homer Road in Solihull, near Birmingham, in 1908, where his father had been appointed the School Medical Officer and Lecturer (later Professor) of Public Health.

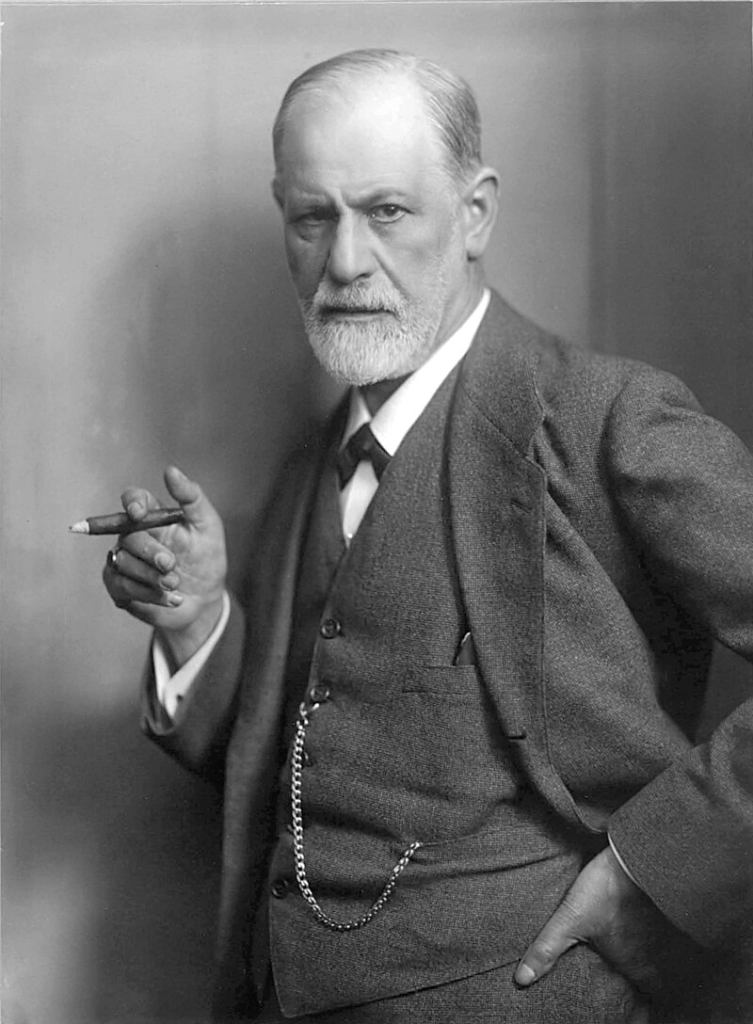

Auden’s lifelong psychoanalytic interests began in his father’s library.

Above: St. Alphege Church, Solihull, West Midlands, England

From the age of 8, Auden attended boarding schools, returning home for holidays.

His visits to the Pennine landscape and its declining lead-mining industry figure in many of his poems.

Above: Forest of Bowland, Pennines

The remote decaying mining village of Rookhope was for him a “sacred landscape“, evoked in a late poem, “Amor Loci“.

Above: Rookhope Village, Durham, England

Until he was 15, Auden expected to become a mining engineer, but his passion for words had already begun.

He wrote later:

“Words so excite me that a pornographic story, for example, excites me sexually more than a living person can do.“

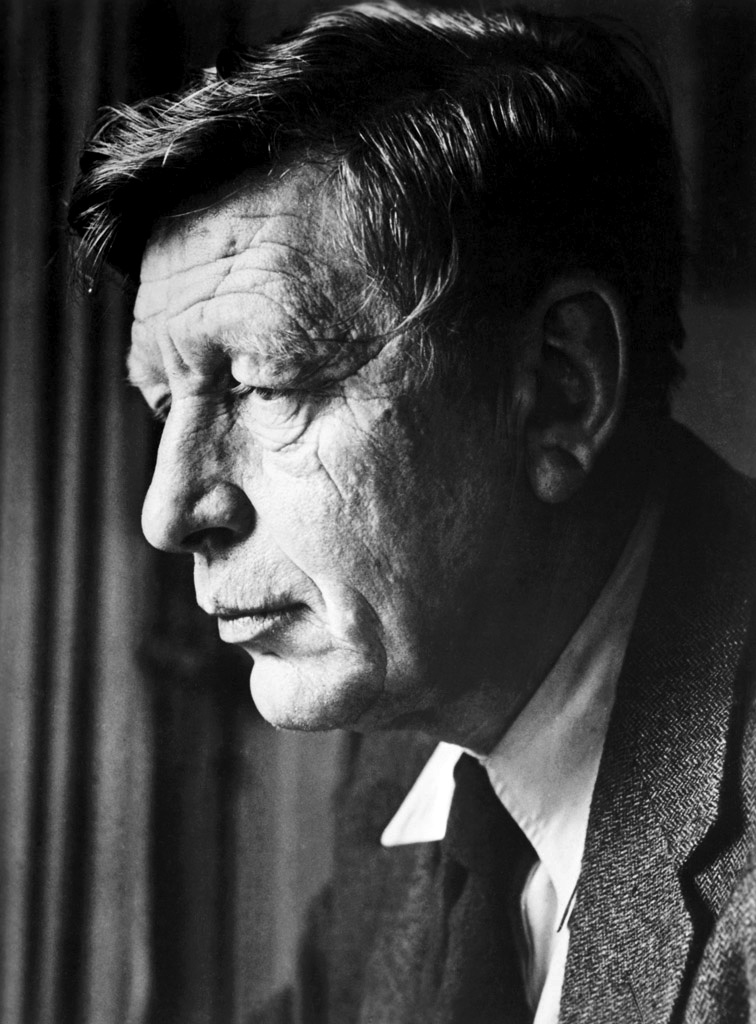

Above: W. H. Auden

Auden attended St Edmund’s School, Hindhead, Surrey, where he met Christopher Isherwood, later famous in his own right as a novelist.

Above: St. Edmund’s School, Hindhead, Surrey, England

At age 13, Auden went to Gresham’s School in Holt, Norfolk.

Above: Gresham’s School, Holt, Norfolk, England

There, in 1922, when his friend Robert Medley asked him if he wrote poetry, Auden first realized his vocation was to be a poet.

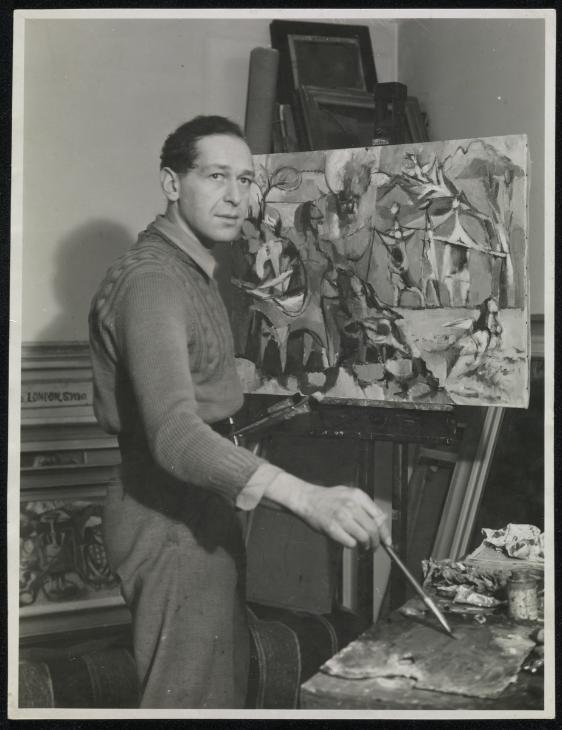

Above: English artist Robert Medley (1905 – 1994)

Soon after, Auden “discovered that he had lost his faith” (through a gradual realization that he had lost interest in religion, not through any decisive change of views).

In school productions of Shakespeare, he played Katherina in The Taming of the Shrew in 1922, and Caliban in The Tempest in 1925, his last year at Gresham’s.

A review of his performance as Katherina noted that despite a poor wig, he had been able “to infuse considerable dignity into his passionate outbursts“.

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Auden’s first published poems appeared in the school magazine in 1923.

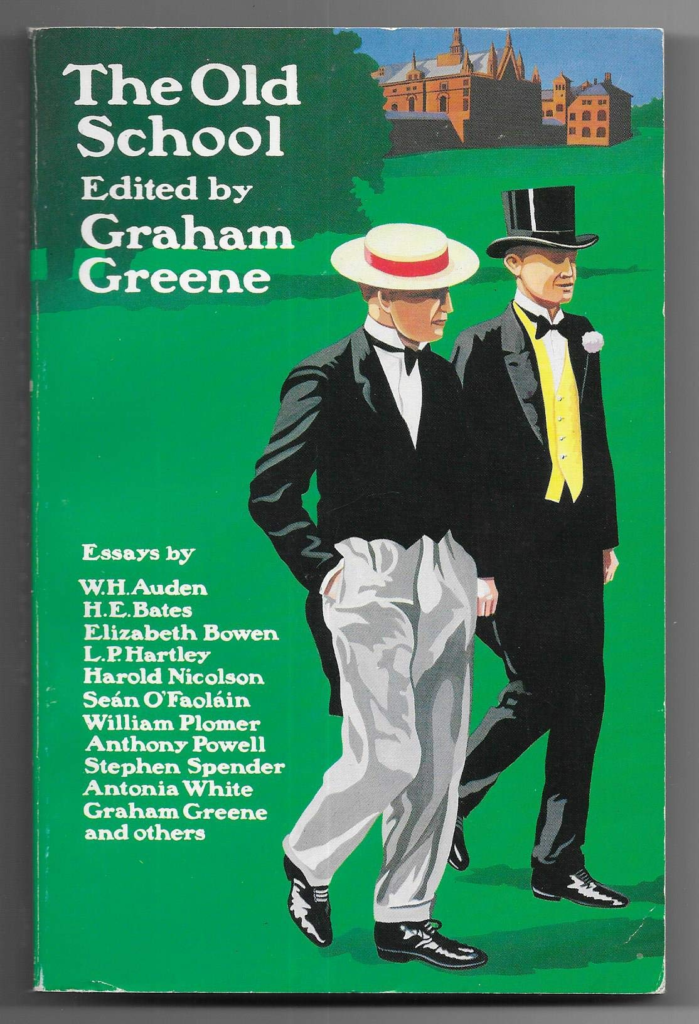

Auden later wrote a chapter on Gresham’s for Graham Greene’s The Old School: Essays by Divers Hands (1934).

In 1925 he went up to Christ Church, Oxford, with a scholarship in biology.

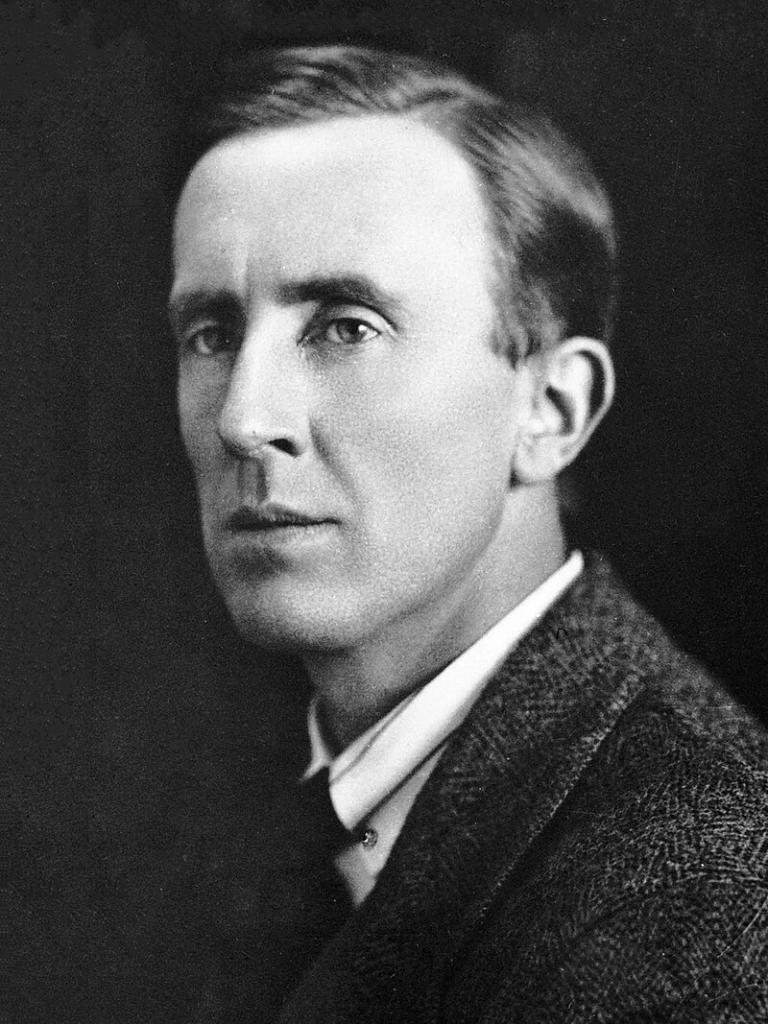

He changed to English by his second year and was introduced to Old English poetry through the lectures of J. R. R. Tolkien.

Above: South African-English writer John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892 – 1973)

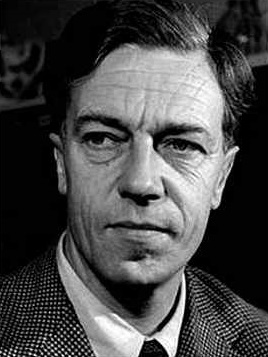

Friends he met at Oxford include Cecil Day-Lewis, Louis MacNeice, and Stephen Spender.

These three were commonly though misleadingly identified in the 1930s as the “Auden Group” for their shared (but not identical) left-wing views.

Above: British poet Cecil Day-Lewis (1904 – 1972)

Above: English writer Louis MacNeice (1907 – 1963)

Above: English writer Stephen Spender (1909 – 1995)

Auden left Oxford in 1928 with a third-class degree.

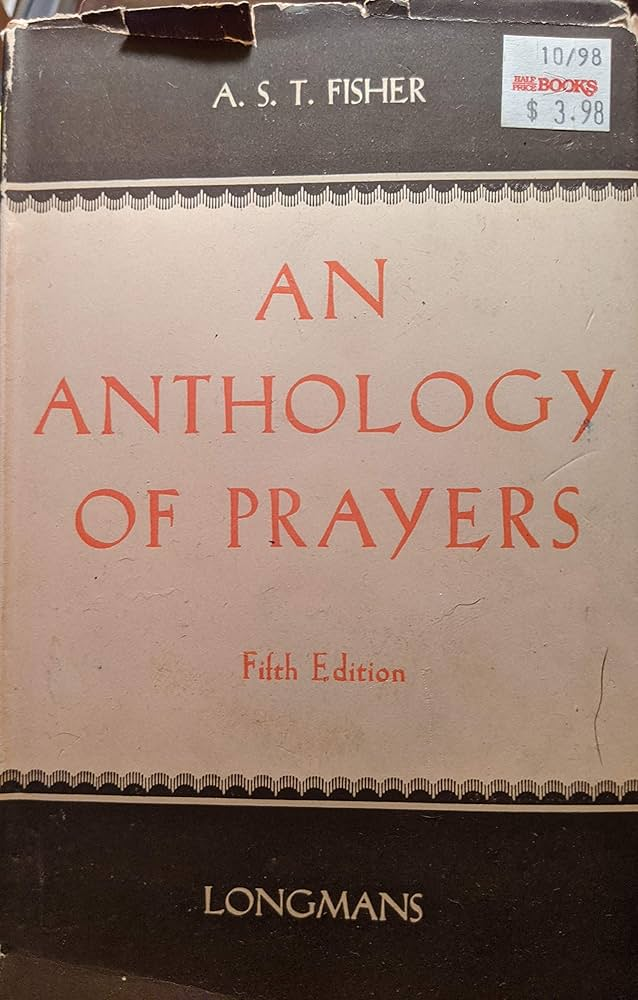

Auden was reintroduced to Christopher Isherwood in 1925 by his fellow student / future priest-writer A. S. T. Fisher (1906 – 1989).

For the next few years Auden sent poems to Isherwood for comments and criticism.

The two maintained an intimate friendship in intervals between their relations with others.

From 1935 to 1939 they collaborated on three plays and a travel book.

Above: Isherwood and Auden

From his Oxford years onward, Auden’s friends uniformly described him as funny, extravagant, sympathetic, generous, and, partly by his own choice, lonely.

In groups he was often dogmatic and overbearing in a comic way; in more private settings he was diffident and shy except when certain of his welcome.

He was punctual in his habits, and obsessive about meeting deadlines, while living amidst physical disorder.

Above: W. H. Auden

In late 1928, Auden left Britain for nine months, going to Berlin, perhaps partly as an escape from English repressiveness.

In Berlin, he first experienced the political and economic unrest that became one of his central subjects.

Above: Berlin, Germany (1928)

Around the same time, Stephen Spender privately printed a small pamphlet of Auden’s Poems in an edition of about 45 copies, distributed among Auden’s and Spender’s friends and family.

This edition is usually referred to as Poems [1928] to avoid confusion with Auden’s commercially published 1930 volume.

On returning to Britain in 1929 he worked briefly as a tutor.

In 1930 his first published book, Poems (1930), was accepted by T. S. Eliot for Faber and Faber, and the same firm remained the British publisher of all the books he published thereafter.

In 1930, he began five years as a schoolmaster in boys’ schools:

Two years at the Larchfield Academy (now Lomond School) in Helensburgh, Scotland, then three years at the Downs School in the Malvern Hills, where he was a much-loved teacher.

Above: Lomond School, Helensburgh, Argyll and Bute, Scotland

Above: The Downs School, Malvern, Herefordshire, England

At the Downs, in June 1933, Auden experienced what he later described as a “Vision of Agape“, while sitting with three fellow teachers at the school, when he suddenly found that he loved them for themselves, that their existence had infinite value for him.

This experience, he said, later influenced his decision to return to the Anglican Church in 1940.

During these years Auden’s erotic interests focused, as he later said, on an idealized “Alter Ego” rather than on individual people.

His relationships (and his unsuccessful courtships) tended to be unequal either in age or intelligence.

His sexual relations were transient, although some evolved into long friendships.

He contrasted these relationships with what he later regarded as the “marriage” (his word) of equals that he began with American poet Chester Kallman (1921 – 1975) in 1939, based on the unique individuality of both partners.

Above: Auden and Kallman

In 1935 Auden married Erika Mann (1905 – 1969), the bisexual novelist daughter of Thomas Mann, when it became apparent that the Nazis were intending to strip her of her German citizenship.

Mann had asked Christopher Isherwood if he would marry her so she could become a British citizen.

He declined but suggested she approach Auden, who readily agreed to a marriage of convenience.

Mann and Auden never lived together, but remained on good terms throughout their lives and were still married when Mann died in 1969.

She left him a small bequest in her will.

Above: German actress/novelist Erika Mann (1905 – 1969)

In 1936, Auden introduced actress Therese Giehse, Mann’s lover, to the writer John Hampson.

Above: English novelist John Hampson (1901 – 1955)

They too married so that Giehse could leave Germany.

Above: German actress Therese Giehse (1898 – 1975)

From 1935 until he left Britain early in 1939, Auden worked as freelance reviewer, essayist, and lecturer, first with the GPO Film Unit, a documentary film-making branch of the post office, headed by Scottish filmmaker John Grierson.

Above: Jorge Ruiz (left) and John Grierson (right)

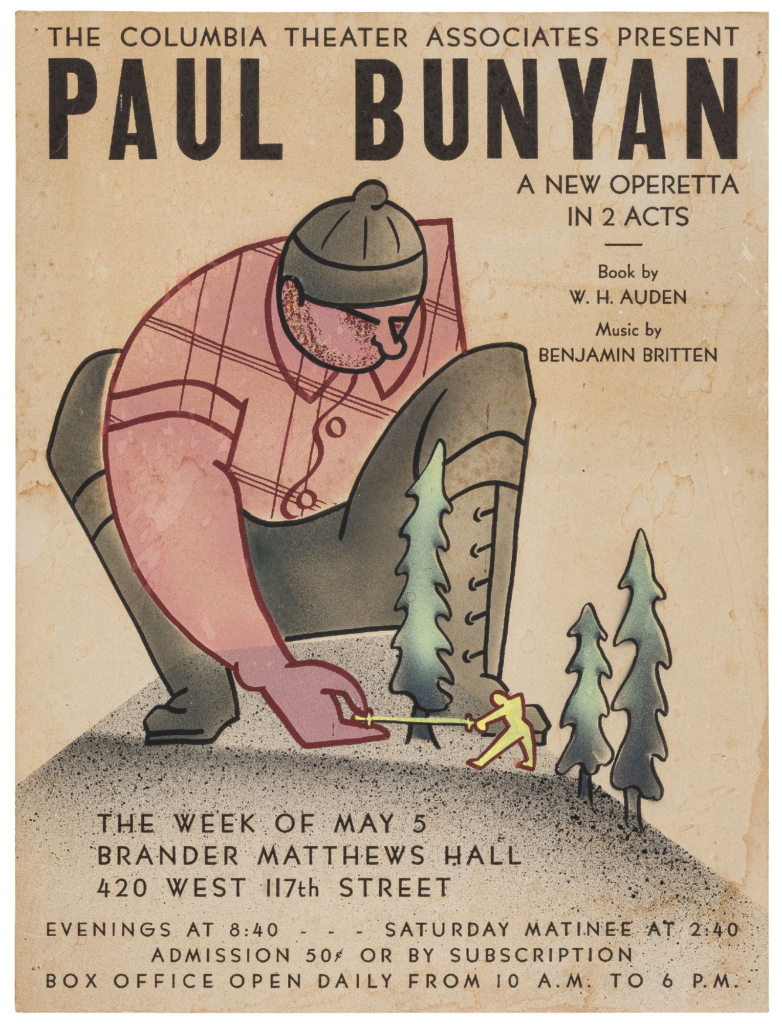

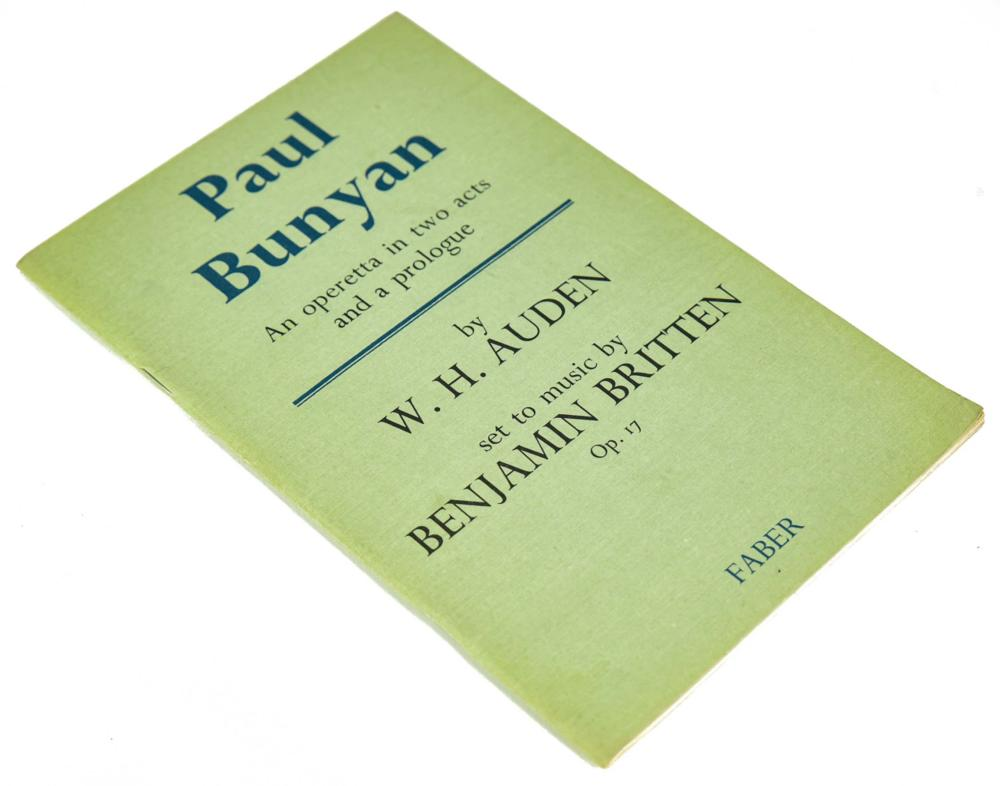

Through his work for the Film Unit in 1935 he met and collaborated with Benjamin Britten, with whom he also worked on plays, song cycles, and a libretto.

Above: English composer Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976)

Auden’s plays in the 1930s were performed by the Group Theatre, in productions that he supervised to varying degrees.

His work now reflected his belief that any good artist must be “more than a bit of a reporting journalist“.

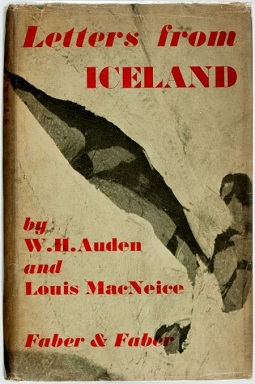

In 1936, Auden spent three months in Iceland where he gathered material for a travel book Letters from Iceland (1937), written in collaboration with Louis MacNeice.

In 1937, Auden went to Spain intending to drive an ambulance for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, but was put to work writing propaganda at the Republican press and propaganda office, where he felt useless and left after a week.

He returned to England after a brief visit to the front at Sarineña.

His seven-week visit to Spain affected him deeply.

His social views grew more complex as he found political realities to be more ambiguous and troubling than he had imagined.

Above: Images of the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939)

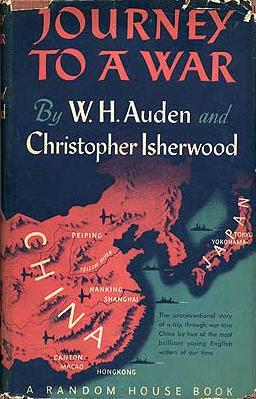

Again attempting to combine reportage and art, he and Isherwood spent six months in 1938 visiting China amid the Sino-Japanese War, working on their book Journey to a War (1939).

On their way back to England they stayed briefly in New York and decided to move to the United States.

Above: New York City (1938)

Auden spent late 1938 partly in England, partly in Brussels.

Above: Brussels, Belgium (1938)

Many of Auden’s poems during the 1930s and after were inspired by unconsummated love.

In the 1950s he summarized his emotional life in a famous couplet:

If equal affection cannot be

Let the more loving one be me

(“The More Loving One“).

Auden had a gift for friendship and, starting in the late 1930s, a strong wish for the stability of marriage.

In a letter to his friend Irish writer James Stern he called marriage “the only subject“.

Above: James Stern (1904 – 1993)

Throughout his life, Auden performed charitable acts, sometimes in public, as in his 1935 marriage of convenience to Erika Mann, but, especially in later years, more often in private.

Above: Erika Mann and W. H. Auden

Auden was embarrassed if they were publicly revealed, as when his gift to his friend Dorothy Day for the Catholic Worker movement was reported on the front page of The New York Times in 1956.

Above: American activist Dorothy Day (1897 – 1980)

Auden and Isherwood sailed to New York City in January 1939, entering on temporary visas.

Their departure from Britain was later seen by many as a betrayal, and Auden’s reputation suffered.

In April 1939, Isherwood moved to California.

He and Auden saw each other only intermittently in later years.

Above: Auden and Isherwood

Around this time, Auden met the poet Chester Kallman, who became his lover for the next two years.

(Auden described their relation as a “marriage” that began with a cross-country “honeymoon” journey.)

In 1941 Kallman ended their intimate relationship because he could not accept Auden’s insistence on mutual fidelity, but he and Auden remained companions for the rest of Auden’s life, sharing houses and apartments from 1953 until Auden’s death.

Auden dedicated both editions of his collected poetry (1945/50 and 1966) to Isherwood and Kallman.

Above: Kallman and Auden

In 1940 – 1941 Auden lived in a house at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights, that he shared with Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten, and others, which became a famous centre of artistic life, nicknamed “February House“.

Above: American writer Carson McCullers (1917 – 1967)

Above: February House, Brooklyn Heights, New York

In 1940, Auden joined the Episcopal Church, returning to the Anglican Communion he had abandoned at 15.

Above: Shield of the Episcopal Church (American Anglican)

His reconversion was influenced partly by what he called the “sainthood” of Charles Williams, whom he had met in 1937, and partly by reading Søren Kierkegaard and Reinhold Niebuhr.

Above: English writer Charlie Williams (1886 – 1945)

Above: Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

Above: American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971)

His existential, this-worldly Christianity became a central element in his life.

After Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Auden told the British embassy in Washington that he would return to the UK if needed.

He was told that, among those his age (32), only qualified personnel were needed.

Above: Flag of the United Kingdom

In 1941 – 1942 Auden taught English at the University of Michigan.

Auden was called for the draft in the United States Army in August 1942, but was rejected on medical grounds.

He had been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for 1942 – 1943 but did not use it, choosing instead to teach at Swarthmore College in 1942 – 1945.

In mid-1945, after the end of World War II in Europe, he was in Germany with the US Strategic Bombing Survey, studying the effects of Allied bombing on German morale, an experience that affected his postwar work as his visit to Spain had affected him earlier.

On his return, Auden settled in Manhattan, working as a freelance writer, a lecturer at The New School for Social Research, and a visiting professor at Bennington, Smith and other American colleges.

In 1946, he became a naturalized citizen of the US.

Above: Coat of arms of the United States of America

In 1948 Auden began spending his summers in Europe, together with Chester Kallman, first in Ischia, Italy, where he rented a house.

Above: Ischia, Italy

Starting in 1958, Auden began spending his summers in Kirchstetten, Austria, where he bought a farmhouse with the prize money of the Premio Feltrinelli awarded to him in 1957.

Auden said that he shed tears of joy at owning a home for the first time.

His later poetry, mostly written in Austria, includes his sequence “Thanksgiving for a Habitat” about his Kirchstetten home.

Auden’s letters and papers sent to his friend the translator Stella Musulin (1915 – 1996), available online, provide insights into his Austrian years.

Above: Auden House, Kirchstetten, Austria

From 1956 to 1961, Auden was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, where he was required to give three lectures each year.

This fairly light workload allowed him to continue to spend winter in New York, where he lived at 77 St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan’s East Village, and to spend summer in Europe, spending only three weeks each year lecturing in Oxford.

Above: St. Mark’s Place, East Village, New York City

Auden earned his income mostly from readings and lecture tours, and by writing for The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and other magazines.

In 1963, Kallman left the apartment he shared in New York with Auden, and lived during the winter in Athens while continuing to spend his summers with Auden in Austria.

Auden spent the winter of 1964 – 1965 in Berlin through an artist-in-residence program of the Ford Foundation.

Following some years of lobbying by his friend David Luke (1921 – 2005), Auden’s old college, Christ Church, in February 1972 offered him a cottage on its grounds to live in.

He moved his books and other possessions from New York to Oxford in September 1972, while continuing to spend summers in Austria with Kallman.

He spent only one winter in Oxford before his death in 1973.

Above: Oxford, Oxfordshire, England

Auden died at 66 of heart failure at the Altenburgerhof Hotel in Vienna overnight on 28 – 29 September 1973, a few hours after giving a reading of his poems for the Austrian Society for Literature at the Palais Pálffy.

He had intended to return to Oxford the following day.

Above: Palais Páiffy, Vienna, Austria

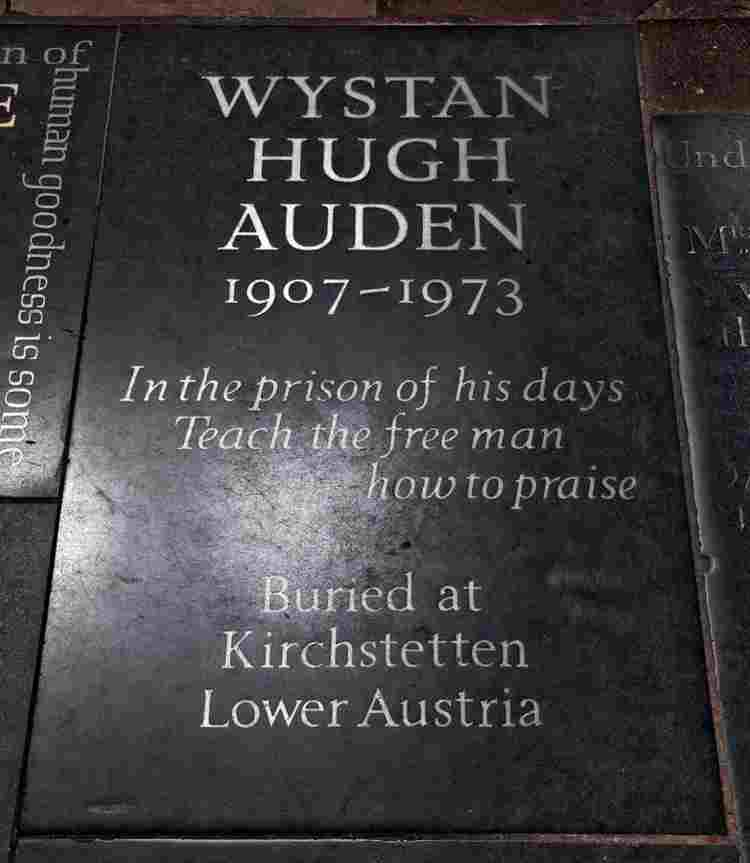

Auden was buried on 4 October in Kirchstetten.

Above: Auden’s grave at Kirchstetten

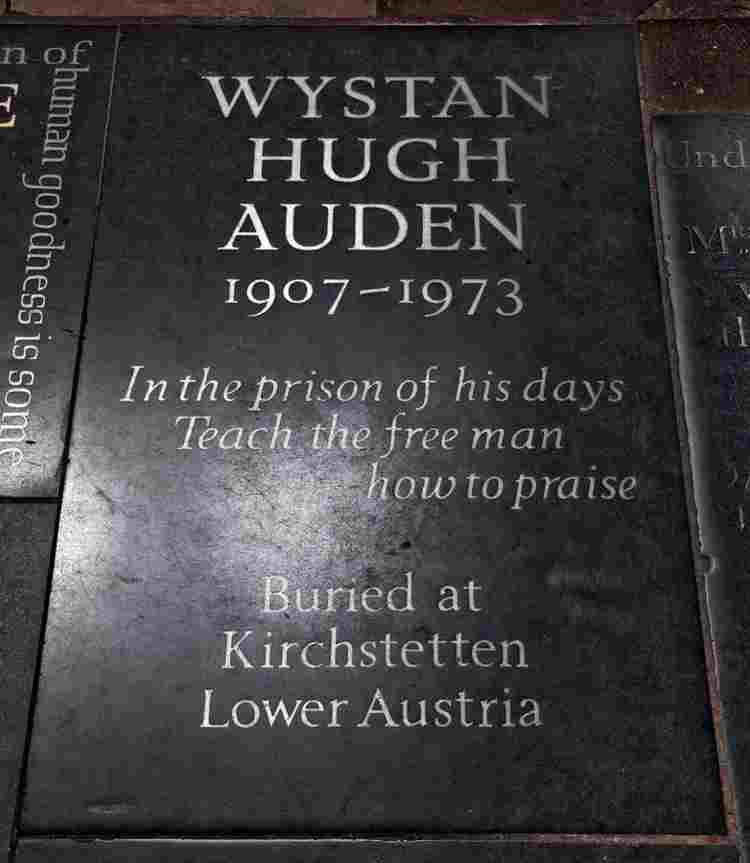

A memorial stone was placed in Westminster Abbey in London a year later.

Above: Auden Memorial, Westminster Cathedral, London, England

Auden published about 400 poems, including seven long poems (two of them book-length).

His poetry was encyclopaedic in scope and method, ranging in style from obscure 20th century modernism to the lucid traditional forms such as ballads and limericks, from doggerel through haiku and villanelles to a “Christmas Oratorio” and a baroque eclogue in Anglo-Saxon meters.

The tone and content of his poems ranged from pop-song clichés to complex philosophical meditations, from the corns on his toes to atoms and stars, from contemporary crises to the evolution of society.

He also wrote more than 400 essays and reviews about literature, history, politics, music, religion and many other subjects.

He collaborated on plays with Christopher Isherwood and on opera libretti with Chester Kallman.

Auden worked with a group of artists and filmmakers on documentary films in the 1930s and with the New York Pro Musica early music group in the 1950s and 1960s.

About collaboration he wrote in 1964:

“Collaboration has brought me greater erotic joy than any sexual relations I have had.“

Auden controversially rewrote or discarded some of his most famous poems when he prepared his later collected editions.

He wrote that he rejected poems that he found “boring” or “dishonest” in the sense that they expressed views he had never held but had used only because he felt they would be rhetorically effective.

His rejected poems include “Spain” and “September 1, 1939″.

His literary executor, Edward Mendelson, argues in his introduction to Selected Poems that Auden’s practice reflected his sense of the persuasive power of poetry and his reluctance to misuse it.

(Selected Poems includes some poems that Auden rejected and early texts of poems that he revised.)

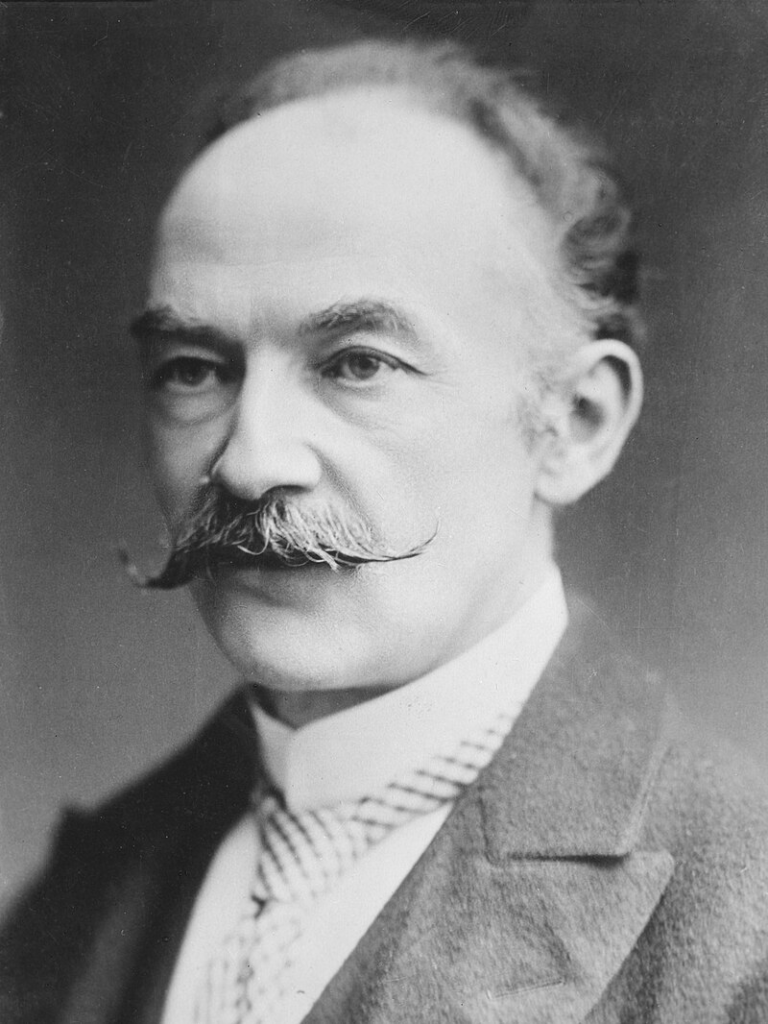

Auden began writing poems in 1922, at 15, mostly in the styles of 19th-century romantic poets, especially Wordsworth, and later poets with rural interests, especially Thomas Hardy.

Above: English poet William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850)

Above: English writer Thomas Hardy (1840 – 1928)

At 18, Auden discovered T. S. Eliot and adopted an extreme version of Eliot’s style.

Above: American poet Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888 – 1965)

Auden found his own voice at 20 when he wrote the first poem later included in his collected work, “From the very first coming down“.

This and other poems of the late 1920s tended to be in a clipped, elusive style that alluded to, but did not directly state, their themes of loneliness and loss.

From the very first coming down

Into a new valley with a frown

Because of the sun and a lost way.

You certainly remain: to-day

I, crouching behind a sheep-pen, heard

Travel across a sudden bird,

Cry out against the storm, and found

The year’s arc a completed round

And love’s worn circuit re-begun,

Endless with no dissenting turn.

Shall see, shall pass, as we have seen

The swallow on the tile, spring’s green

Preliminary shiver, passed

A solitary truck, the last

Of shunting in the Autumn. But now,

To interrupt the homely brow,

Thought warmed to evening through and through,

Your letter comes, speaking as you,

Speaking of much, but not to come.

Nor speech is close nor fingers numb,

If love not seldom has received

An unjust answer, was deceived.

I, decent with the seasons, move

Different or with a different love,

Nor question much the nod,

The stone smile of this country god

That never was more reticent,

Always afraid to say more than it meant.

Twenty of these poems appeared in his first book Poems (1928), a pamphlet hand-printed by Stephen Spender.

In 1928 he wrote his first dramatic work, Paid on Both Sides, subtitled “A Charade“, which combined style and content from the Icelandic sagas with jokes from English school life.

This mixture of tragedy and farce, with a dream play-within-a-play, introduced the mixed styles and content of much of his later work.

This drama and thirty short poems appeared in his first published book Poems (1930).

The poems in the book were mostly lyrical and gnomic meditations on hoped-for or unconsummated love and on themes of personal, social, and seasonal renewal; among these poems were:

- “It was Easter as I walked“

It was Easter as I walked in the public gardens,

Hearing the frogs exhaling from the pond,

Watching traffic of magnificent cloud

Moving without anxiety on open sky—

Season when lovers and writers find

An altering speech for altering things,

An emphasis on new names, on the arm

A fresh hand with fresh power.

But thinking so I came at once

Where solitary man sat weeping on a bench,

Hanging his head down, with his mouth distorted

Helpless and ugly as an embryo chicken.

So I remember all of those whose death

Is necessary condition of the season’s putting forth,

Who, sorry in this time, look only back

To Christmas intimacy, a winter dialogue

Fading in silence, leaving them in tears.

And recent particulars come to mind;

The death by cancer of a once hated master,

A friend’s analysis of his own failure,

Listened to at intervals throughout the winter

At different hours and in different rooms.

But always with success of others for comparison,

The happiness, for instance, of my friend Kurt Groote,

Absence of fear in Gerhart Meyer

From the sea, the truly strong man.

A ‘bus ran home then, on the public ground

Lay fallen bicycles like huddled corpses:

No chattering valves of laughter emphasised

Nor the swept gown ends of a gesture stirred

The sessile hush; until a sudden shower

Fell willing into grass and closed the day,

Making choice seem a necessary error.

- “Doom is dark“

Doom is dark and deeper than any sea-dingle.

Upon what man it fall

In spring, day-wishing flowers appearing,

Avalanche sliding, white snow from rock-face,

That he should leave his house,

No cloud-soft hand can hold him, restraint by women;

But ever that man goes

Through place-keepers, through forest trees,

A stranger to strangers over undried sea,

Houses for fishes, suffocating water,

Or lonely on fell as chat,

By pot-holed becks

A bird stone-haunting, an unquiet bird.

There head falls forward, fatigued at evening,

And dreams of home,

Waving from window, spread of welcome,

Kissing of wife under single sheet;

But waking sees

Bird-flocks nameless to him, through doorway

voices

Of new men making another love.

Save him from hostile capture,

From sudden tiger’s leap at corner;

Protect his house,

His anxious house where days are counted

From thunderbolt protect,

From gradual ruin spreading like a stain;

Converting number from vague to certain,

Bring joy, bring day of his returning,

Lucky with day approaching, with leaning dawn.

- “Sir, no man’s enemy“

Sir, no man’s enemy, forgiving all

But will his negative inversion, be prodigal:

Send to us power and light, a sovereign touch

Curing the intolerable neural itch,

The exhaustion of weaning, the liar’s quinsy,

And the distortions of ingrown virginity.

Prohibit sharply the rehearsed response

And gradually correct the coward’s stance;

Cover in time with beams those in retreat

That, spotted, they turn though the reverse were great;

Publish each healer that in city lives

Or country houses at the end of drives;

Harrow the house of the dead; look shining at

New styles of architecture, a change of heart.

- “This lunar beauty“

This lunar beauty

Has no history

Is complete and early,

If beauty later

Bear any feature

It had a lover

And is another.

This like a dream

Keeps other time

And daytime is

The loss of this,

For time is inches

And the heart’s changes

Where ghost has haunted

Lost and wanted.

But this was never

A ghost’s endeavor

Nor finished this,

Was ghost at ease,

And till it pass

Love shall not near

The sweetness here

Nor sorrow take

His endless look.

A recurrent theme in these early poems is the effect of “family ghosts“, Auden’s term for the powerful, unseen psychological effects of preceding generations on any individual life (and the title of a poem).

A parallel theme, present throughout his work, is the contrast between biological evolution (unchosen and involuntary) and the psychological evolution of cultures and individuals (voluntary and deliberate even in its subconscious aspects).

Above: W. H. Auden

Put the car away; when life fails

What’s the good of going to Wales?

Here am I, here are you:

But what does it mean? What are we going to do?

“It’s no use raising a shout“, Poems (1930)

Above: Flag of Wales

To ask the hard question is simple,

The simple act of the confused will.

“To Ask the Hard Question is Simple“, Poems (1930)

Auden’s next large-scale work was The Orators: An English Study (1932), in verse and prose, largely about hero-worship in personal and political life.

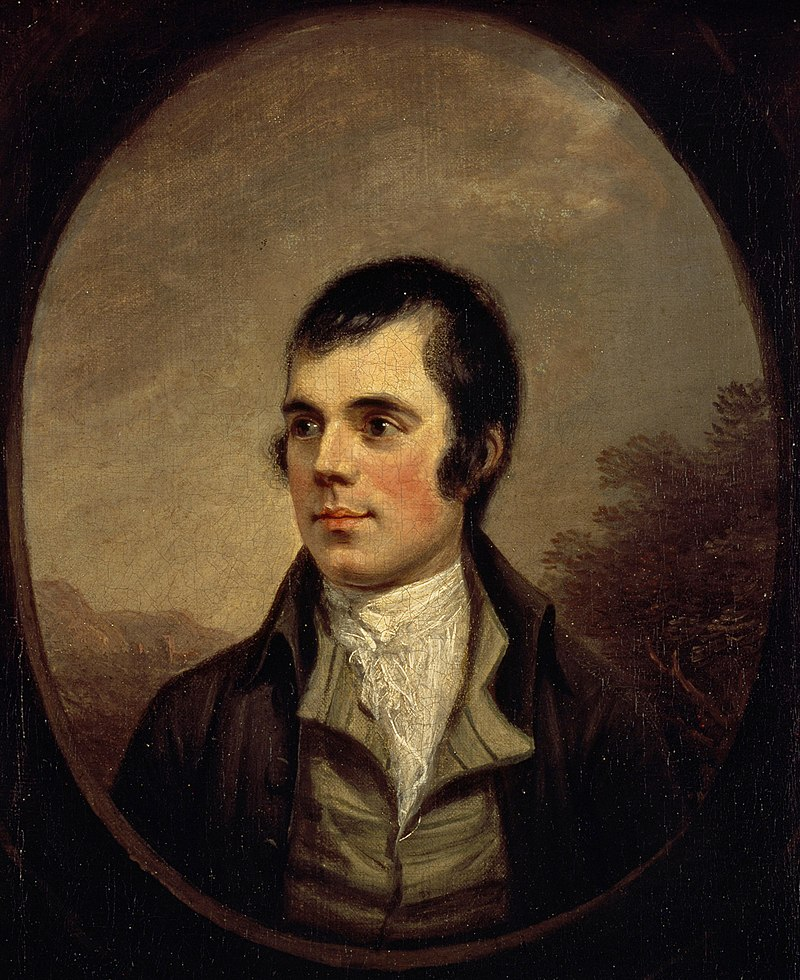

In his shorter poems, his style became more open and accessible, and the exuberant “Six Odes” in The Orators reflect his new interest in Robert Burns.

Above: Scottish poet Robert Burns (1759 – 1796)

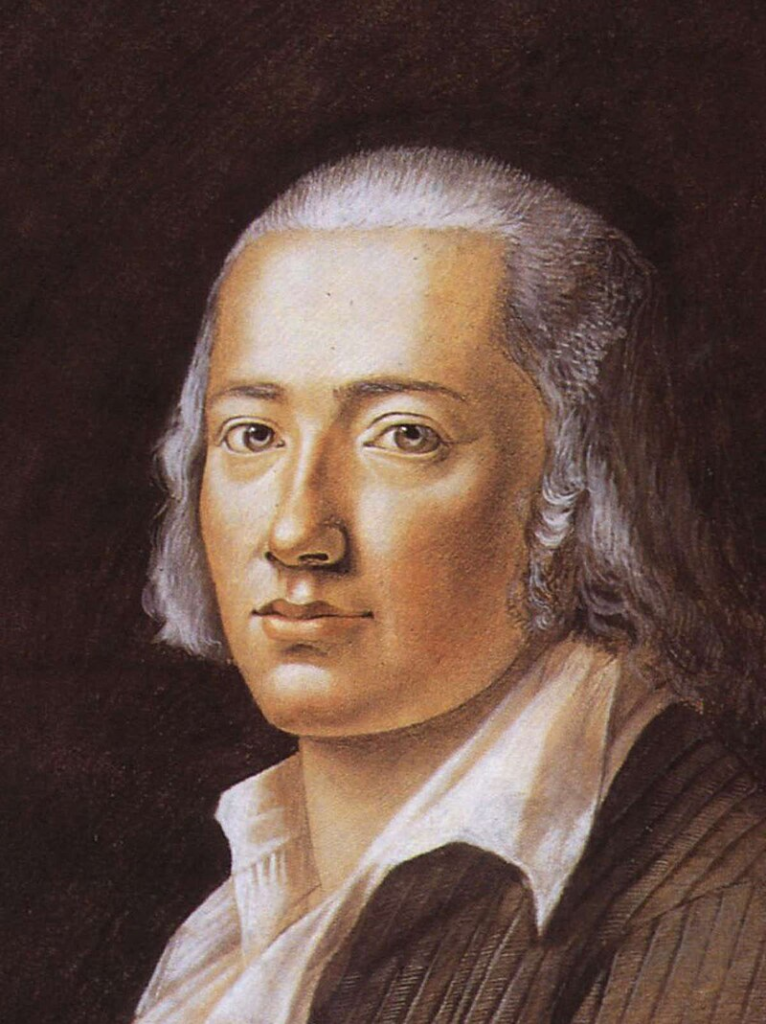

During the next few years, many of his poems took their form and style from traditional ballads and popular songs, and also from expansive classical forms like the Odes of Horace, which he seems to have discovered through the German poet Hölderlin.

Above: Bronze medallion with image of Quintus Horatius Flaccus (aka Horace) (65 – 8 BC)

Above: German poet/philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin (1770 – 1843)

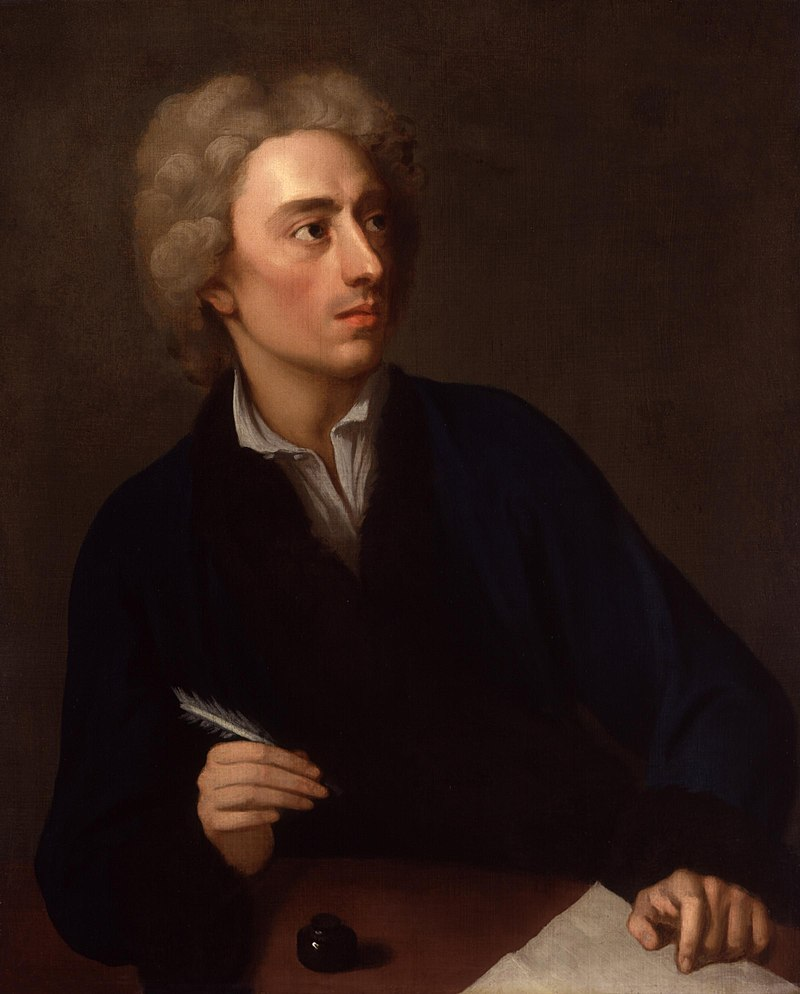

Around this time his main influences were Dante, William Langland (1330 – 1386), and Alexander Pope.

Above: Italian poet/philosopher Dante Aligheri (1265 – 1321)

Above: “Langland’s Dreamer“: from an illuminated initial in a Piers Plowman manuscript held at Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Above: English writer Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744)

During these years much of Auden’s work expressed left-wing views.

He became widely known as a political poet although he was privately more ambivalent about revolutionary politics than many reviewers recognized.

He expounded political views partly out of a sense of moral duty and partly because it enhanced his reputation.

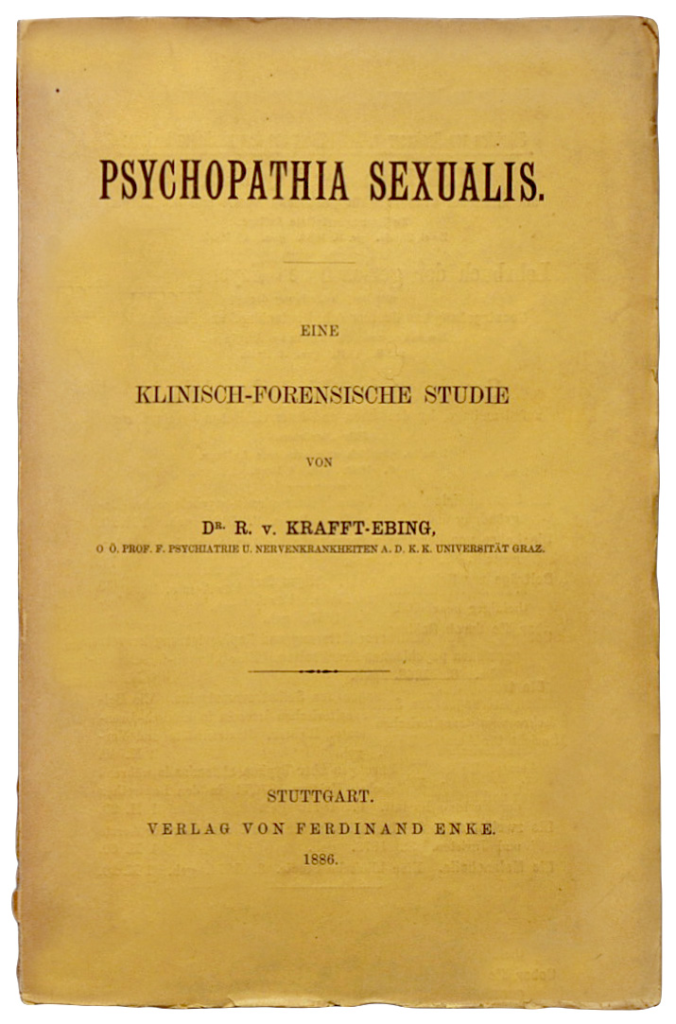

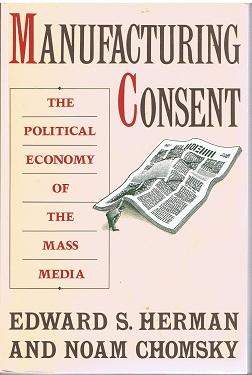

He later regretted having done so.